Abstract

HIV drug resistance is a major global challenge to successful and sustainable antiretroviral therapy. Next-generation sequencing (NGS)-based HIV drug resistance (HIVDR) assays enable more sensitive and quantitative detection of drug-resistance-associated mutations (DRMs) and outperform Sanger sequencing approaches in detecting lower abundance resistance mutations. While NGS is likely to become the new standard for routine HIVDR testing, many technical and knowledge gaps remain to be resolved before its generalized adoption in regular clinical care, public health, and research. Recognizing this, we conceived and launched an international symposium series on NGS HIVDR, to bring together leading experts in the field to address these issues through in-depth discussions and brainstorming. Following the first symposium in 2018 (Winnipeg, MB Canada, 21–22 February, 2018), a second “Winnipeg Consensus” symposium was held in September 2019 in Winnipeg, Canada, and was focused on external quality assurance strategies for NGS HIVDR assays. In this paper, we summarize this second symposium’s goals and highlights.

1. HIV Drug Resistance Is a Global Challenge

With over 40 currently available antiretroviral therapy (ART) drugs, HIV/AIDS has now been successfully converted from a fatal disease into a manageable chronic infection [1,2]. Effective ART not only improves the quality of life of individuals living with HIV, but also minimizes horizontal and vertical HIV transmission contributing to its effective containment on a global scale [3]. However, drug resistance (DR) is a major challenge to treatment success. HIV drug resistance (HIVDR) is facilitated by the virus’ high replication rate, error-prone replication process, and duration of drug selection pressure [4,5,6]. With an average of one error introduced per viral replication cycle, all HIV variants within an infected individual could theoretically be genetically unique forming a highly diversified pool of viruses, or quasispecies. This extraordinary level of diversity creates a large gene pool in which variations, or mutations, may exist at any nucleotide codon in the HIV genome, or any amino acid it encodes [5,7]. ART drugs that are part of a given regimen may effectively eliminate the majority of circulating HIV variants that are sensitive to them. However, under certain circumstances and changing drug selective pressures, HIV variant(s) harboring DR-associated mutations (DRMs) may outgrow and become dominant, due to their selective advantage in the presence of ART drug(s), resulting in resumed replication and ART failure. HIVDR currently constitutes a major obstacle in the maximization of ART benefits at both individual and population levels [8,9].

2. Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Is an Emerging New Standard for HIVDR Testing

While the cost-effectiveness of HIVDR testing prior to ART initiation or ART regimen switch remains debatable in different contexts [10,11], timely HIVDR detection and ART regimen adjustments play a vital role in the effective clinical management of persons with HIV [12,13]. Conventional genotypic DR assays rely on sequencing of relevant HIV gene fragments using population-based Sanger sequencing (SS) technology to detect known HIV DRMs qualitatively [14]. The resistance profile is then inferred using well-established HIVDR interpretation systems [15]. While SS-based HIVDR testing has been widely applied for decades, some intrinsic constraints limit its ability to quantitatively identify DRMs at frequencies below ~20% of the viral quasispecies [16,17,18]. While integrase inhibitors are being more broadly administered, genotypic resistance analysis on the integrase (IN) gene is often needed. This usually requires a second SS test since it is distant from the protease (PR) and beginning of the reverse transcriptase (RT) genes targeted by routine HIVDR genotyping. Additionally, SS has low data throughput and scalability, which is challenging for laboratories processing large numbers of specimens [19,20].

Propelled largely by the need for affordable genome sequencing, many NGS technologies have been developed and made commercially available since 2005, when the 454 pyrosequencing technology was first launched [21]. Currently, exemplified by the Illumina sequencing-by-synthesis approach, several NGS technologies are available and are being broadly adopted by research and clinical laboratories (Table 1). While sequencing mechanisms vary, all NGS technologies empower massive, parallel, clonal sequencing of input DNA templates without a need for molecular cloning. NGS has become an essential tool in nearly all molecular biology fields [22].

Table 1.

Currently available next-generation sequencing (NGS) sequencing platforms.

The application of NGS to HIV genotyping began in 2006 when it was primarily used to resolve HIV quasispecies [23]. In 2007, Hoffmann et al. and Wang et al. applied the NGS 454 pyrosequencing platform to HIVDR testing [24,25]. Since then, multiple NGS platforms have been adopted for HIVDR testing by independent laboratories in different contexts worldwide [20,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. It has been well-demonstrated that NGS outperforms SS for genotypic HIVDR testing in regards to scalability, data throughput, and especially sensitivity for detection of minority resistance variants (MRVs), which may lead to ART failure [16,36]. Additionally, in high-throughput environments where sample batching is feasible, NGS offers improved time efficiency and cost-effectiveness [37]. Meanwhile, although separate SS assays are required to cover the PR + RT and IN gene when needed, sequencing all three genes simultaneously or even beyond can be easily achieved by using longer PCR amplicons or combining different amplicons prior to the fragmentation and tagmentation steps during NGS library preparation [38,39]. While the large number of clonal NGS reads from a single specimen can enable high-resolution analyses of literally all HIVDR variants, the consensus sequences derived from NGS can also be used to mimic SS output in any downstream applications, such as phylogenetic analysis for molecular epidemiology that often requires “one sample, one sequence”. Therefore, NGS HIVDR assays are flexible as they can produce conventional SS-like readouts, while also allowing in-depth quantitation of MRVs.

Although still in its infancy, NGS HIVDR testing holds great promise in enhancing patient management and is likely to become the new genotypic standard [40]. While primarily applied in research settings, recent attempts have been made to incorporate NGS into HIVDR public health surveillance and clinical settings. The Vela Sentosa® SQ HIV-1 Genotyping platform from Vela Diagnostics has been recently approved as the first commercial NGS HIVDR assay for clinical HIVDR testing by regulatory agencies in several settings, including the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (US FDA) [41,42,43]. This Ion Torrent technology-based Sentosa® platform accommodates sequencing of HIVDR relevant genes with sensitivity for MRV detection at 10% when the viral load (VL) is ≥5,000 copies/mL or 20% as VL is lower. However, the high per sample cost (~$400) limits its accessibility for generalized applications for patient care or HIVDR surveillance uses.

3. Standardization of NGS HIVDR Testing Is Urgently Required

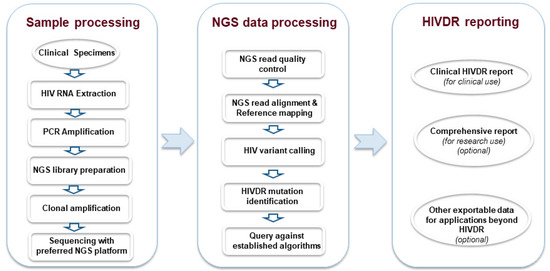

NGS HIVDR assays are multiprocedural processes consisting of many quality control (QC) checkpoints to ensure high data quality. They need both well-developed protocols for sample processing in the laboratory, and sophisticated bioinformatics pipelines for automated data processing, unbiased, correct identification of HIV DRMs, and actionable HIVDR reporting (Figure 1). Laboratory procedures involve the extraction of HIV viral RNA, reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) amplification to convert viral RNA into complementary DNA and enrich the target HIV templates, NGS library preparation, and DNA sequencing with the NGS platform of choice. Thus far, many NGS laboratory protocols have been developed and/or published by different groups in varied contexts. Expectedly, significant variations exist among such protocols, especially in regard to in-house developed assays. Likewise, NGS HIVDR data analysis is a complex process involving large volumes of raw data that need to be analyzed for read QC, reference mapping, variant calling, DRM identification, HIVDR interpretation and reporting, and generation of other exportable data (i.e., consensus sequence) for relevant downstream applications. Many such bioinformatics pipelines have also been developed, some publicly available while others proprietary from commercial sources [45]. Despite these advances, most laboratory protocols and pipelines were developed by independent groups with minimal intercommunication among them, and validated using strategies selected by the developers, as no consensus or guidelines for validation are available. These knowledge and technical gaps can inevitably create difficulties for performance assessment of NGS HIVDR protocols, making comparisons among different platforms and methods difficult. Standardization of both molecular and bioinformatics strategies for NGS HIVDR testing is urgently required for the operationalization and general implementation of such assays in routine practice.

Figure 1.

NGS-based HIV drug resistance testing workflow.

4. Initiation of an International Symposium Series on NGS HIVDR Testing

Recognizing that many technical and knowledge gaps still exist, in late 2017, we conceived an international symposium series on NGS HIVDR testing. The main aim was to convene leading research scientists, clinicians, bioinformaticians and laboratory experts in the field to communicate and brainstorm relevant strategies and ensure the reliability of NGS HIVDR output for research, public health, and especially patient care needs. The ultimate objective of these symposia is to establish consensus on specific technical aspects associated with NGS for HIVDR testing and to propose best practice recommendations and professional guidelines.

The inaugural NGS HIVDR symposium was held in 2018 in Winnipeg, Canada, and focused on bioinformatics strategies. The developers of four commonly applied, freely available pipelines convened to share their experience in pipeline development, exchange ideas for further improvements and brainstorm the best possible strategies to ensure both the quality and utility of the output data derived from such pipelines. The four pipeline teams included HyDRA from the National Microbiology Laboratory in Canada, PASeq from IrsiCaixa Institute for AIDS Research in Spain, MiCall, from the British Columbia Center for Excellence in HIV/AIDS in Canada, and hivmmer from Brown University in the United States [20,46,47]. The first technical recommendation document for NGS HIVDR data processing was generated in that symposium, now referred to as the first “Winnipeg Consensus” [45]. This document may serve as a prototypic guideline for refinements of existing NGS HIVDR pipelines and for the development of new bioinformatics tools for processing of NGS data from viral pathogens like HIV that harbor significant intra-host genetic diversity. One recent study compared the performance of five different pipelines designed for NGS HIVDR analysis, including HyDRA, MiCall, PASeq, hivmmer and DEEPGEN [48]. Although these pipelines are highly comparable while analyzing mutations at higher abundance, significant discrepancies were observed when variants under the 2% NGS threshold were concerned, largely due to differences in their data management strategies. These findings certainly support the notion that unified NGS HIV data processing strategies are urgently required.

5. Are We Ready for NGS HIV Drug Resistance Testing? The Second “Winnipeg Consensus” Symposium

While the bioinformatics strategies for NGS HIVDR are complex, their key functional modules are rather straightforward, and their requirements for ensuring output data quality are relatively definable. In contrast, variations among different NGS assays predominantly result from laboratory procedures through which samples are processed and sequenced, often by different NGS platforms (Figure 1). Such differences could arise from any experimental procedures or, in most cases, a combined consequence from the aggregate workflow. These variations can be further complicated by intra-host (mostly within the same HIV-1 subtype) and inter-host (within the same subtype or among different subtypes) HIV diversity when clinical specimens are examined. Conceivably, all strategies that deal with NGS HIVDR laboratory protocol development, assay validation, or internal and external quality control would never be straightforward but require joint efforts from experts in the field.

The second international symposium on NGS HIVDR testing was held in Winnipeg, Canada, in September 2019. It gathered invited experts in the field from 18 leading institutes in eight different countries. To address gaps described above, the focus of the discussions was on to-be-developed external quality assessment (EQA) strategies for laboratories performing NGS HIVDR assays. In-depth discussions were carried out during the symposium on many different aspects that affect the operationalization of NGS HIVDR tests, especially in clinical laboratory practice. These included: (1) clinical and laboratory advances in NGS HIVDR testing; (2) feasibility and challenges in transitioning from SS towards NGS for HIVDR testing; (3) NGS HIVDR assay validation and internal quality controls strategies, including incorporation of unique molecular identifiers (UMIs); (4) EQA strategies and logistics; (5) development of proficiency testing (PT) panels for NGS HIVDR assays; and (6) laboratory, clinical and implementation considerations that facilitate the general adoption of NGS HIVDR testing; (7) other challenges, such as the implementation status of the first “Winnipeg Consensus” and new bioinformatics challenges identified, especially for accountable variant calling and NGS consensus sequence generation. While reaching a consensus is always the ultimate goal of such a symposium, all delegates acknowledged that more research is still required to better formulate suitable recommendations for NGS HIVDR internal and external quality assurance strategies when laboratory procedures are taken into consideration. Despite this consensus on “no consensus”, important knowledge and technical gaps that hinder the general adoption of such assays in frontline laboratories were better defined.

6. Remaining Challenges for Generalized Implementation of NGS HIVDR Testing

The challenges identified in the symposium that may inform further research to refine existing NGS HIVDR testing methods or support the development of new assays are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Challenges for the generalized application of NGS-based HIV drug resistance (HIVDR) testing.

7. Conclusions

With NGS technology becoming less technically challenging and as the clinical relevance of MRVs is better understood, NGS is trending towards becoming the new standard for HIVDR genotyping. An ideal NGS HIVDR assay would: (1) accommodate the significant intra-host and inter-host HIV diversity; (2) be consistently suitable for all specimen formats (e.g., plasma/serum; dried blood spots or peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs)) and HIV-1 subtypes at varied VL levels; (3) resolve viral quasispecies with DRMs at high resolution and accuracy; (4) perform well on native HIV templates directly with no requirement for PCR-based library preparation, avoiding related bias and artificial errors; (5) produce long reads covering the entire target gene fragment and enabling HIVDR analysis at the variant rather than mutation level; (6) be low-cost with fast turnaround time, making it suitable for resource-limited settings and/or effective patient care needs; and (7) operate with minimal instrumentation and technical requirements enabling potential point-of-care HIVDR monitoring. Needless to say, meeting these requirements with a single assay is challenging and will require further research and development. The second “Winnipeg Consensus” symposium, highlights of which were presented here, started to address some of the remaining challenges for generalized use of NGS HIVDR testing, hopefully bringing us closer to meet these requirements in the coming years.

Author Contributions

All co-authors are the members of the organizing committee for the symposium series and the leaders of themed discussion sessions during the meeting. H.J. drafted the manuscript, and all co-authors contributed significantly to the revisions of this manuscript and gave consent to this submission. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This symposium was funded primarily by the Public Health Agency of Canada and the Federal Initiative to Address HIV/AIDS in Canada (HJ and PS). This work was supported by grants from the Mexican Government (Comisión de Equidad y Género de las Legislaturas LX-LXI y Comisión de Igualdad de Género de la Legislatura LXII de la H. Cámara de Diputados de la República Mexicana), and Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACyT SALUD-2017-01-289725), received by SAR. RK was supported in part by R01AI147333, R01AI136058, R01AI120792, K24AI134359 and P30AI042853. The APC was funded by the Public Health Agency of Canada.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the generous in-kind support from all participating parties and institutes for the symposium series and the related research and development efforts.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests for this research-only publication. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- AIDSinfo. FDA-Approved HIV Medicines. 2020. Available online: https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/understanding-hiv-aids/fact-sheets/21/58/fda-approved-hiv-medicines (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Drugs That Fight HIV-1: A Reference Guide for Prescription HIV-1 Medications; The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2018.

- Yombi, J.C.; Mertes, H. Treatment as prevention for HIV infection: Current data, challenges, and global perspectives. AIDS Rev. 2018, 20, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menendez-Arias, L. Targeting HIV: Antiretroviral therapy and development of drug resistance. Trends Pharm. Sci. 2002, 23, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffin, J.M. HIV population dynamics in vivo: Implications for genetic variation, pathogenesis, and therapy. Science 1995, 267, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, D.D. Perspectives series: Host/pathogen interactions. Dynamics of HIV-1 replication in vivo. J. Clin. Investig. 1997, 99, 2565–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, E.; Sheldon, J.; Perales, C. Viral quasispecies evolution. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2012, 76, 159–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clutter, D.S.; Jordan, M.R.; Bertagnolio, S.; Shafer, R.W. HIV-1 drug resistance and resistance testing. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2016, 46, 292–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Global Action Plan on HIV Drug Resistance 2017–2021; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hyle, E.P.; Scott, J.A.; Sax, P.E.; Millham, L.R.I.; Dugdale, C.M.; Weinstein, M.C.; Freedberg, K.A.; Walensky, R.P. Clinical impact and cost-effectiveness of genotype testing at human immunodeficiency virus diagnosis in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 70, 1353–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, A.N.; Cambiano, V.; Nakagawa, F.; Magubu, T.; Miners, A.; Ford, D.; Pillay, D.; De Luca, A.; Lundgren, J.; Revill, P. Cost-Effectiveness of HIV Drug Resistance Testing to Inform Switching to Second Line Antiretroviral Therapy in Low Income Settings. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e109148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Adults and Adolescents Living with HIV 2017. Available online: https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/AdultandAdolescentGL003510.pdf (accessed on 26 May 2020).

- Günthard, H.F.; Calvez, V.; Paredes, R.; Pillay, D.; Shafer, R.W.; Wensing, A.M.; Jacobsen, D.M.; Richman, U.D. Human Immunodeficiency Virus Drug Resistance: 2018 Recommendations of the International Antiviral Society–USA Panel. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 68, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanger, F.; Nicklen, S.; Coulson, A.R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1977, 74, 5463–5467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandamme, A.-M.; Camacho, R.; Ceccherini-Silberstein, F.; De Luca, A.; Palmisano, L.; Paraskevis, D.; Paredes, R.; Poljak, M.; Schmit, J.-C.; Soriano, V.; et al. European recommendations for the clinical use of HIV drug resistance testing: 2011 update. Aids Rev. 2011, 13, 77–108. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Simen, B.B.; Simons, J.F.; Hullsiek, K.H.; Novak, R.M.; MacArthur, R.D.; Baxter, J.D.; Huang, C.; Lubeski, C.; Turenchalk, G.S.; Braverman, M.S.; et al. Low-Abundance Drug-Resistant Viral Variants in Chronically HIV-Infected, Antiretroviral Treatment–Naive Patients Significantly Impact Treatment Outcomes. J. Infect. Dis. 2009, 199, 693–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korn, K.; Reil, H.; Walter, H.; Schmidt, B. Quality Control Trial for Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Drug Resistance Testing Using Clinical Samples Reveals Problems with Detecting Minority Species and Interpretation of Test Results. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003, 41, 3559–3565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, J.A.; Li, J.-F.; Wei, X.; Lipscomb, J.; Irlbeck, D.; Craig, C.; Smith, A.; E Bennett, D.; Monsour, M.; Sandstrom, P.; et al. Minority HIV-1 Drug Resistance Mutations Are Present in Antiretroviral Treatment–Naïve Populations and Associate with Reduced Treatment Efficacy. PLoS Med. 2008, 5, e158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Li, Y.; Graham, M.R.; Liang, B.; Pilon, R.; Tyson, S.; Peters, G.; Tyler, S.; Merks, H.; Bertagnolio, S.; et al. Next-generation sequencing of dried blood spot specimens: A novel approach to HIV drug-resistance surveillance. Antivir. Ther. 2011, 16, 871–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, T.; Lee, E.R.; Nykoluk, M.; Enns, E.; Liang, B.; Capina, R.; Gauthier, M.-K.; Domselaar, G.V.; Sandstrom, P.; Brooks, J.; et al. A MiSeq-HyDRA platform for enhanced HIV drug resistance genotyping and surveillance. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margulies, M.; Egholm, M.; Altman, W.E.; Attiya, S.; Bader, J.S.; Bemben, L.A.; Berka, J.; Braverman, M.S.; Chen, Y.-J.; Chen, Z.; et al. Genome sequencing in microfabricated high-density picolitre reactors. Nature 2005, 437, 376–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, P. Next Generation Sequencing: Chemistry, Technology and Applications. Chem. Diagn. 2012, 336, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bushman, F.D.; Hoffmann, C.; Ronen, K.; Malani, N.; Minkah, N.; Rose, H.M.; Tebas, P.; Wang, G.P. Massively parallel pyrosequencing in HIV research. AIDS 2008, 22, 1411–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Mitsuya, Y.; Gharizadeh, B.; Ronaghi, M.; Shafer, R.W. Characterization of mutation spectra with ultra-deep pyrosequencing: Application to HIV-1 drug resistance. Genome Res. 2007, 17, 1195–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, C.; Minkah, N.; Leipzig, J.; Wang, G.; Arens, M.Q.; Tebas, P.; Bushman, F.D. DNA bar coding and pyrosequencing to identify rare HIV drug resistance mutations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, e91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derache, A.; Iwuji, C.C.; Danaviah, S.; Giandhari, J.; Marcelin, A.-G.; Calvez, V.; De Oliveira, T.; Dabis, F.; Pillay, D.; Gupta, R.K. Predicted antiviral activity of tenofovir versus abacavir in combination with a cytosine analogue and the integrase inhibitor dolutegravir in HIV-1-infected South African patients initiating or failing first-line ART. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 74, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekici, H.; Rao, S.D.; Sönnerborg, A.; Ramprasad, V.L.; Gupta, R.; Neogi, U. Cost-efficient HIV-1 drug resistance surveillance using multiplexed high-throughput amplicon sequencing: Implications for use in low- and middle-income countries. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2014, 69, 3349–3355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, R.M.; Meyer, A.M.; Winner, D.; Archer, J.; Feyertag, F.; Ruiz-Mateos, E.; Leal, M.; Robertson, D.L.; Schmotzer, C.L.; Quiñones-Mateu, M.E. Sensitive Deep-Sequencing-Based HIV-1 Genotyping Assay To Simultaneously Determine Susceptibility to Protease, Reverse Transcriptase, Integrase, and Maturation Inhibitors, as Well as HIV-1 Coreceptor Tropism. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 2167–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, H.; Massé, N.; Tyler, S.; Liang, B.; Li, Y.; Merks, H.; Graham, M.; Sandstrom, P.; Brooks, J. HIV Drug Resistance Surveillance Using Pooled Pyrosequencing. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ji, H.; Li, Y.; Liang, B.; Pilon, R.; MacPherson, P.; Bergeron, M.; Kim, J.; Graham, M.; Van Domselaar, G.; Sandstrom, P.; et al. Pyrosequencing Dried Blood Spots Reveals Differences in HIV Drug Resistance between Treatment Naïve and Experienced Patients. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e56170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Keys, J.R.; Zhou, S.; Anderson, J.A.; Eron, J.J.; Rackoff, L.A.; Jabara, C.; Swanstrom, R. Primer ID Informs Next-Generation Sequencing Platforms and Reveals Preexisting Drug Resistance Mutations in the HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase Coding Domain. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 2015, 31, 658–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapointe, H.R.; Dong, W.; Lee, G.Q.; Bangsberg, D.R.; Martin, J.N.; Mocello, A.R.; Boum, Y.; Karakas, A.; Kirkby, D.; Poon, A.F.Y.; et al. HIV Drug Resistance Testing by High-Multiplex “Wide” Sequencing on the MiSeq Instrument. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 6824–6833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscona, R.; Ram, D.; Wax, M.; Bucris, E.; Levy, I.; Mendelson, E.; Mor, O. Comparison between next-generation and Sanger-based sequencing for the detection of transmitted drug-resistance mutations among recently infected HIV-1 patients in Israel, 2000–2014. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2017, 20, 21846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, S.; Nicot, F.; Carcenac, R.; Lefebvre, C.; Jeanne, N.; Sauné, K.; Delobel, P.; Izopet, J. HIV-1 genotypic resistance testing using the Vela automated next-generation sequencing platform. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 1152–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzou, P.L.; Ariyaratne, P.; Varghese, V.; Lee, C.; Rakhmanaliev, E.; Villy, C.; Yee, M.; Tan, K.; Michel, G.; Pinsky, B.A.; et al. Comparison of an In Vitro Diagnostic Next-Generation Sequencing Assay with Sanger Sequencing for HIV-1 Genotypic Resistance Testing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2018, 56, e00105–e00118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.Z.; Paredes, R.; Ribaudo, H.J.; Svarovskaia, E.S.; Metzner, K.J.; Kozal, M.; Hullsiek, K.H.; Balduin, M.; Jakobsen, M.R.; Geretti, A.M.; et al. Low-Frequency HIV-1 Drug Resistance Mutations and Risk of NNRTI-Based Antiretroviral Treatment Failure. JAMA 2011, 305, 1327–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inzaule, S.C.; Ondoa, P.; Peter, T.; Mugyenyi, P.N.; Stevens, W.S.; De Wit, T.F.R.; Hamers, R.L. Affordable HIV drug-resistance testing for monitoring of antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, e267–e275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telele, N.F.; Kalu, A.; Gebre-Selassie, S.; Fekade, D.; Abdurahman, S.; Marrone, G.; Neogi, U.; Tegbaru, B.; Sönnerborg, A. Pretreatment drug resistance in a large countrywide Ethiopian HIV-1C cohort: A comparison of Sanger and high-throughput sequencing. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, B.M.; Siqueira, J.; Prellwitz, I.M.; Botelho, O.M.; Da Hora, V.P.; Sanabani, S.; Recordon-Pinson, P.; Fleury, H.; Soares, E.A.; Soares, M.A. Estimating HIV-1 Genetic Diversity in Brazil Through Next-Generation Sequencing. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casadellà, M.; Paredes, R. Deep sequencing for HIV-1 clinical management. Virus Res. 2017, 239, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA. FDA Authorizes Marketing of First Next-Generation Sequencing Test for Detecting HIV-1 Drug Resistance Mutations; FDA: White Oak, MD, USA, 2019.

- Raymond, S.; Nicot, F.; Abravanel, F.; Minier, L.; Carcenac, R.; Lefebvre, C.; Harter, A.; Martin-Blondel, G.; Delobel, P.; Izopet, J. Performance evaluation of the Vela Dx Sentosa next-generation sequencing system for HIV-1 DNA genotypic resistance. J. Clin. Virol. 2020, 122, 104229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, J.; Volkova, I.; Sahoo, M.K.; Tzou, P.L.; Shafer, R.W.; Pinsky, B.A. Prospective Evaluation of the Vela Diagnostics Next-Generation Sequencing Platform for HIV-1 Genotypic Resistance Testing. J. Mol. Diagn. 2019, 21, 961–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. The Use of Next-Generation Sequencing Technologies for the Detection of Mutations Associated with Drug Resistance in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Complex: Technical Guide; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, H.; Enns, E.; Brumme, C.; Parkin, N.; Howison, M.; Lee, E.R.; Capina, R.; Marinier, E.; Avila-Rios, S.; Sandstrom, P.; et al. Bioinformatic data processing pipelines in support of next-generation sequencing-based HIV drug resistance testing: The Winnipeg Consensus. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2018, 21, e25193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguera-Julian, M.; Edgil, D.; Harrigan, P.R.; Sandstrom, P.; Godfrey, C.; Paredes, R. Next-Generation Human Immunodeficiency Virus Sequencing for Patient Management and Drug Resistance Surveillance. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 216, S829–S833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howison, M.; Coetzer, M.; Kantor, R. Measurement error and variant-calling in deep Illumina sequencing of HIV. Bioinformatics 2018, 35, 2029–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.R.; Parkin, N.; Jennings, C.; Brumme, C.J.; Enns, E.; Casadellà, M.; Howison, M.; Coetzer, M.; Avila-Rios, S.; Capina, R.; et al. Performance comparison of next generation sequencing analysis pipelines for HIV-1 drug resistance testing. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonsall, D.; Golubchik, T.; De Cesare, M.; Limbada, M.; Kosloff, B.; MacIntyre-Cockett, G.; Hall, M.; Wymant, C.; Ansari, M.A.; Abeler-Dorner, L.; et al. A comprehensive genomics solution for HIV surveillance and clinical monitoring in a global health setting. BioRxiv 2018, 397083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabara, C.B.; Jones, C.D.; Roach, J.; Anderson, J.A.; Swanstrom, R. Accurate sampling and deep sequencing of the HIV-1 protease gene using a primer ID. Proc. Natl. Acad Sci. USA 2011, 108, 20166–20171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Jones, C.; Mieczkowski, P.; Swanstrom, R. Primer ID Validates Template Sampling Depth and Greatly Reduces the Error Rate of Next-Generation Sequencing of HIV-1 Genomic RNA Populations. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 8540–8555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkin, N.; Zaccaro, D.; Avila-Rios, S.; Brumme, C.; Hunt, G.; Ji, H.; Kantor, R.; Mbisa, J.L.; Predes, R.; Rivera-Amill, V.; et al. Multi-Laboratory comparison of next-generation to Sanger-based sequencing for HIV-1 drug resistance genotyping. In Proceedings of the XXVII International HIV Drug Resistance and Treatment Strategies Workshop, Johannesburg, South Africa, 22–23 October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.R.; Parkin, N.; Enns, E.; Brumme, C.J.; Casadella, M.; Howison, M.; Avila Rios, S.; Jennings, R.; Capina, R.; Marinier, E.; et al. Characterization and data assessment of next generation sequencing-based genotyping using existing HIV-1 drug resistance proficiency panels. In Proceedings of the XXVII International HIV Drug Resistance and Treatment Strategies Workshop, Johannesburg, South Africa, 22–23 October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, H.; Parkin, N.; Gao, F.; Denny, T.; Jennings, C.; Sandstrom, P.; Kantor, R. External Quality Assessment Program for Next-Generation Sequencing-Based HIV Drug Resistance Testing: Logistical Considerations. Viruses 2020, 12, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.R.; Gao, F.; Sandstrom, P.; Ji, H. External Quality Assessment for Next-Generation Sequencing-Based HIV Drug Resistance Testing: Unique Requirements and Challenges. Viruses 2020, 12, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliseev, A.; Gibson, K.M.; Avdeyev, P.; Novik, D.; Bendall, M.L.; Perez-Losada, M.; Alexeev, N.; Crandall, K.A. Evaluation of haplotype callers for next-generation sequencing of viruses. Infect Genet. Evol. 2020, 82, 104277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasibhatla, S.M.; Waman, V.P.; Kale, M.; Kulkarni-Kale, U. Analysis of Next-Generation Sequencing Data in Virology-Opportunities and Challenges. In Next Generation Sequencing—Advances, Applications and Challenges; eBook (PDF); Jerzy, K., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-953-51-5419-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinier, E.; Enns, E.; Tran, C.; Fogel, M.; Peters, C.; Kidwai, A.; Ji, H.; Van Domselaar, G. quasitools: A Collection of Tools for Viral Quasispecies Analysis. BioRxiv 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozal, M.; Chiarella, J.; John, E.P.S.; Moreno, E.A.; Simen, B.B.; E Arnold, T.; Lataillade, M. Prevalence of low-level HIV-1 variants with reverse transcriptase mutation K65R and the effect of antiretroviral drug exposure on variant levels. Antivir. Ther. 2011, 16, 925–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, D.D.; Zhou, Y.; Margot, N.; McColl, D.J.; Zhong, L.; Borroto-Esoda, K.; Miller, M.D.; Svarovskaia, E. Low level of the K103N HIV-1 above a threshold is associated with virological failure in treatment-naive individuals undergoing efavirenz-containing therapy. AIDS 2011, 25, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Mbunkah, H.; Bertagnolio, S.; Hamers, R.L.; Hunt, G.M.; Inzaule, S.; De Wit, T.F.R.; Paredes, R.; Parkin, N.T.; Jordan, M.R.; Metzner, K.J.; et al. Low-Abundance Drug-Resistant HIV-1 Variants in Antiretroviral Drug-Naive Individuals: A Systematic Review of Detection Methods, Prevalence, and Clinical Impact. J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 221, 1584–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).