Abstract

Investigating and assigning gene functions of herpesviruses is a process, which profits from consistent technical innovation. Cloning of bacterial artificial chromosomes encoding herpesvirus genomes permits nearly unlimited possibilities in the construction of genetically modified viruses. Targeted or randomized screening approaches allow rapid identification of essential viral proteins. Nevertheless, mapping of essential genes reveals only limited insight into function. The usage of dominant-negative (DN) proteins has been the tool of choice to dissect functions of proteins during the viral life cycle. DN proteins also facilitate the analysis of host-virus interactions. Finally, DNs serve as starting-point for design of new antiviral strategies.

1. Scope

In this article, we will highlight the possibilities of dominant-negative (DN) proteins as tools to elucidate gene functions, pathways and processes. Potential benefits of DN proteins as antiviral agents in intracellular immunization are mentioned.

3. Dominant-Negative Proteins

In need of novel strategies to dissect functions of protein complexes and their roles in diverse pathways, the use of DN mutants arise to be an important and forward-looking strategy in virology. Before going into detail how DN mutants can be and have been used in the field of herpesvirus biology, the term ‘dominant-negative’ requires an explanation.

In 1987 Ira Herskowitz reported in Nature, how cloned genes altered to encode mutant products are capable to inhibit the wt gene product in a cell, thus causing the cell to be deficient in the function of the gene product [10]. In diploid eukaryotic organisms, genes are present in two alleles, one from each parent. As a consequence, two different versions of the gene product can be present in the cell. Mutants of one allele, which also inhibits the other wt allele product to fulfill its function, are called ‘dominant-negative’, as they rule over the intact protein. Therefore, in herpesviral genomes that encode for only one allele, DN genes have to be complemented either in cis, by an additional viral expression cassette or in trans, by the host cell.

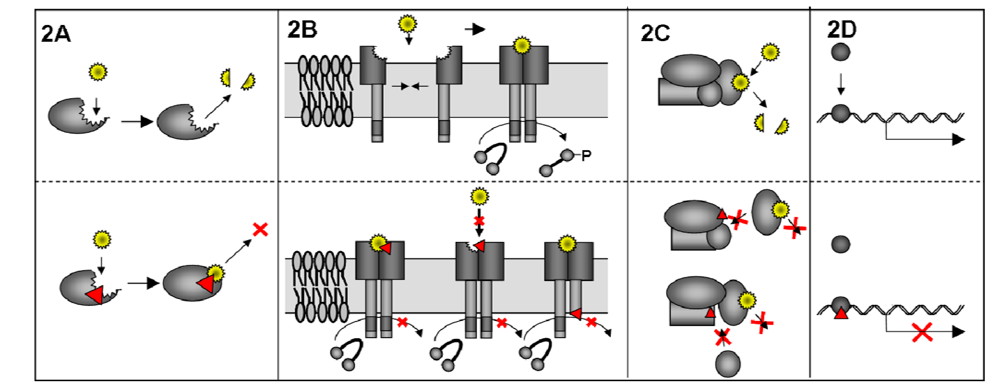

3.1. Mechanism of DN proteins

There are different methods how a DN mutant may work, which are reviewed in detail from Veitia [35,36]. Mutations in the catalytic site of an enzyme are one way how a DN mutant can arise; in that case the substrate is bound but not converted and so the balance of the reaction is disturbed. Examples in cell biology are mutations in ATPases or GTPases [37,38,39], especially Rho GTPases have been widely used [40] (Figure 2A). Very often DN proteins work in complexes, where the inhibitory potential ranges from the block of a simple dimer, as for example membrane receptors or transcription activators, which can transmit a signal only after dimerization [41,42] (Figure 2B), up to multi-subunit complexes (Figure 2C), demonstrated nicely by Barren and Artemyev for G-protein alpha subunit complexes [43]. DN mutations in transcription factors can poison a whole pathway if they block the binding sites for active mutants, therefore, inhibiting all downstream gene expression. As for example in the case of DN mutants of the proto-oncogene p53, resulting in the loss of growth inhibition and cancer manifestation [44] (Figure 2D).

The example of a DN mutant that acts in the wt form as a homo-dimer explains why a DN mutation can cause a stronger phenotype than a deletion (in case of a diploid eukaryotic organism). By equal expression of wt and DN, homo-dimerization of the two proteins will lead to the formation of wt-wt, DN-wt, wt-DN and DN-DN complexes. Therefore only 25% of the dimeric complexes will be functional, while in a deletion it would be 50%. Overexpression of the DN protein shifts the ratio more to non-functional complexes. As (random) insertion into the eukaryotic genome is still easier to achieve than targeted deletion of both alleles, it is obvious why the DN approach is superior to deletion mutants. The problem of targeted deletion was partially overcome by the RNAi approach [45], where complementary siRNA molecules initiate the degradation of the mRNA of both alleles. A drawback of this method is still that down regulation is rarely complete and the knock down is dependent on the half life of the gene product.

Furthermore, DN proteins have one big advantage that cannot be substituted by any deletion, namely that they can arrest the complexes or pathways at different steps. Often proteins are dynamic and have several functions as they bind to many other proteins or have different localizations depending on activation status. Mutating one domain to make it a DN protein, can lead to the disturbance of only one function while leaving other domains intact. Therefore, not the most prominent phenotype due to the loss of the protein, which may in fact reflect the sum of several functions, but several arresting steps can be monitored.

Figure 2.

Mode of action of DN proteins. DN proteins can inhibit the function of the wt protein in different ways. A) Mutation (red arrowhead) in the catalytic domain of an enzyme may lead to binding of the substrate (yellow star) but no conversion. B) Schematic view of a phosphorylation reaction that is dependant on substrate binding and homo-dimerization of the DN membrane protein. Mutation of the substrate binding site may lead to a bound substrate, that is not released anymore or the binding of the substrate itself is inhibited. Mutation in the active site of one of the homo-dimers will not allow reaction on the target molecule. In all cases phosphorylation of the target molecule is impaired. C) The function of a multi subunit complex can be influenced by mutation of different subunits of the complex. In all cases binding of the DN subunit competes with binding of the wt subunit. Here the DN protein does not allow binding of another necessary subunit that is needed for the whole multi-complex function. D) DN mutation in a transcription factor blocks the binding site for the wt transcription factor and thereby inhibiting the downstream gene expression.

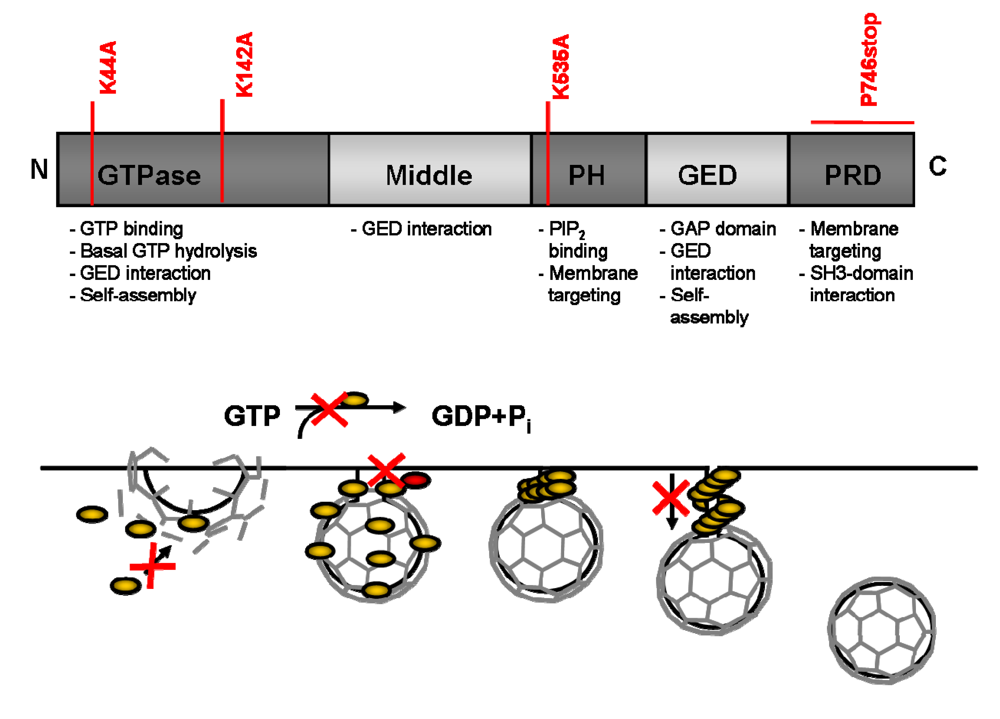

An example for this postulate is the cellular protein Dynamin (Figure 3) that is involved in clathrin-coated vesicle endocytosis. It consists of five domains, a N-terminal GTP hydrolysis domain, a middle domain, a pleckstrin homology (PH) domain a GTPase effector domain (GED) and a C-terminal proline-rich domain (PRD) [46]. A well studied DN mutant is the DynaminK44A, a mutant that cannot bind GTP resulting in a block of receptor-mediated endocytosis [47,48]. Mutation of residue K535 in the PH domain, also giving rise to a DN phenotype, acts by co-oligomerizing with endogenous wt Dynamin and indirectly impairs phosphoinositide binding [49,50]. Deletion of the PRD domain by a stop codon in place of the Proline 746 of Dynamin interferes with the recruitment of Dynamin to clathrin–coated pits and inhibits in a DN fashion receptor-mediated endocytosis [51]. Together with the finding that another mutation in the GTPase domain K142A is defective in its ability to change conformation although still hydrolyzing GTP, the hypothesis was postulated that the function of Dynamin in endocytosis requires both GTP hydrolysis and a resulting conformational change before or concomitant with, vesicle scission [52]. Thus, the use of different DN mutants of the same protein can reveal more information than a deletion could have given, as they represent states that can be perceived as snap shots of highly dynamic processes.

Figure 3.

Dynamin – a proteins function explained by DN mutants. A) The Dynamin protein consists of five different functional domains. Mutations of Dynamin (marked in red), at different positions of the protein, generated DN mutants that inhibit different wt functions of Dynamin. The different functions of the domains are summarized below the scheme. PH: pleckstrin homology domain; GED: GTPase effector domain; PRD: proline-rich domain. B) Schematical overview of the function of Dynamin in endocytosis. Dynamin is recruited to clathrin-coated pits and via GTP hydrolysis results in conformational change before, or concomitant with, vesicle scission. Marked in red are the different steps where DN mutants of Dynamin could block and were used to investigate Dynamin wt functions.

4. Elucidating Herpesvirus Biology with the Help of DN Proteins

Mutants of cellular proteins such as Dynamin can resolve their functions. Of course DN mutants can also be used as tools, by inhibiting known steps in cellular pathways and, thereby, analyzing the effects on viral infection. In case of Dynamin, DN mutants of the protein serve to study whether viruses use receptor-mediated clathrin dependent endocytosis as entry pathway. Thereby, the necessity of Dynamin for entry of HIV-1 could be shown [53], but also the fact that HPV-16 does not need this entry pathway [54].

4.1. Identification of pathways with cellular DN proteins

For herpesviruses entry via receptor-mediated endocytosis or via receptor-mediated fusion has been postulated [55]. Evidences for both cases exist and might depend on the cell line used for the study. Interestingly, use of DN versions of the focal adhesion kinase (FAK), Src-Kinases and RhoGTPase, resulted in decreased uptake of Kaposi’s sarcoma associated herpesvirus. This led to the hypothesis, that upon binding of the virus to surface receptors, signaling of integrins to FAK activates Src. This Src activation may then recruit Clathrin and Dynamin to the cell surface, allowing the bound virus to enter the cell via newly formed vesicles [56,57,58,59]. Although viral entry mechanisms are still a matter of debate, usage of defined DN mutants can help to elucidate the complex process of subsequent steps that happen at the cell membrane.

After entry, capsids are transported to nuclear pores and the viral DNA is released into the nucleus, where viral DNA replication takes place. Study of the cell cycle arrest induced by herpesvirus and the resulting apoptosis has been profiting from the huge set of available DN cyclins. Abusing their original function in cells, herpesviruses bind to cellular cyclins to control late gene expression. Advani and colleagues could demonstrate that a subset of γ2-proteins are not produced in cell lines expressing DN cdc2 [60]. Usage of cyclin D3DN helped to understand the localization and function of ICP0 of HSV [61]. These examples are just illustrations of what can be or has been done with the help of cellular DN proteins.

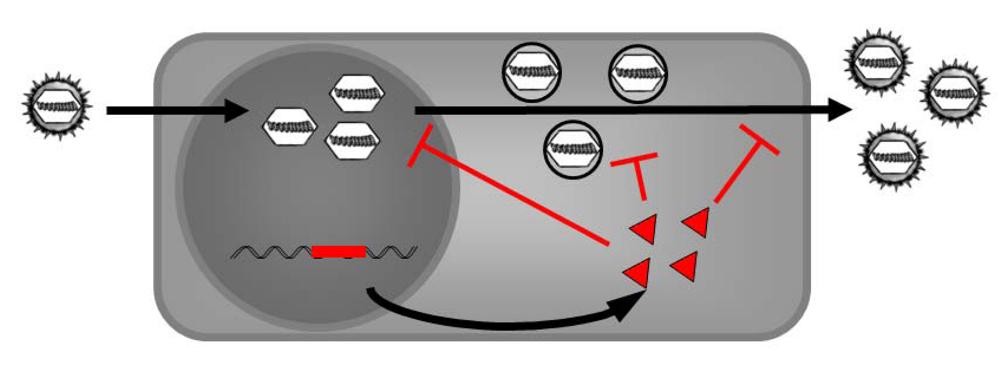

Recently, we could prove the anti-apoptotic feature of M36 of murine cytomegalovirus (MCMV) by replacing the viral gene with a DN FAS-associated via death domain (FADDDN). While the deletion virus ΔM36-MCMV was severely impaired, inhibition of the apoptosis pathway by FADDDN rescued virus replication in vitro and in vivo. This novel approach of inserting cellular DN proteins into the virus genome has enabled us to define the biological function of M36 and might represent a strategy to evaluate other anti-apoptotic viral genes [62].

5. Design of DN Proteins

In summary, utilization of viral or cellular DNs depicts a promising strategy to investigate and dissect the roles of proteins in the viral life cycle. But how can DNs be isolated? Most viral DN mutations were generated at random or found by chance. Many cellular DN mutants have been discovered by resolving the genotypes to certain inherited diseases, as for example mutations in the genes for Collagen causing Osteogenesis Imperfecta [75] or mutations in ras or p53 found in various cancer cells [44]. Often truncations of oligomeric proteins have been found to cause a DN effect [76,77], although this is not necessarily the case. The attempt to tag the small capsid protein of β-herpesviruses with the green fluorescent protein, originally with the purpose to study virus entry with a labeled capsid, generated strong DNs (GFP-SCP) [78]. In another study a library of random fragmented DNA sequences was used to identify truncated proteins that could inhibit bacteriophage lysogenicity; from 80.000 mutants only four DN proteins could be identified and the approach seems to be only feasible for this special application [79]. Random multiple point mutations, as generated by random mutagenesis PCR [80] do not provide direct evidence, which of the changes in the sequence is responsible for the resulting phenotype. Rational protein design could be optimal. An absolute prerequisite in that case is comprehensive knowledge and information about structural or functional domains. This information is limited to only rare cases. A systematic genome-wide screen for DN function has been applied to poliovirus. Mutations have been designed either corresponding to previously characterized lethal mutations or mutations that have been predicted by a computer algorithm to destabilize the protein structures. DN mutations were identified by co-transfecting wt and mutated genomes [81]. While this strategy might be suitable for RNA viruses with small genome size and where substantial information is already known, it is obvious that such an approach is unfeasible at present for the large genomes of herpesviruses. Therefore, to investigate a protein of choice of yet unknown function(s), random mutagenesis is a suitable starting point of investigation.

For this purpose, two methods are generally applicable, alanine-scanning mutagenesis [82,83,84] and linker-scanning transposon mutagenesis [85]. While in the alanine-scanning mutagenesis only amino acid substitutions to alanine are possible, the linker-scanning mutagenesis can not only create additional amino acid insertions but also C-terminal deletions. The production of mutant libraries with both methods is simplified by the availability of commercial products. The limiting and time consuming step is the evaluation of the received mutants.

Generation of DN herpesviral genes by transposon-based mutagenesis can be divided into three steps. In the first round, the cloned gene is mutated by a linker-scanning transposon mutagenesis approach, generating a library of mutants of the gene of interest. In the second step, mutants are reinserted into the herpesviral genome lacking the gene of interest in order to test for their ability to complement the deletion phenotype. This will provide information about essential and important regions of the gene. Then mutants that could not rescue the deletion phenotype are screened for their DN potential by inserting them into a wt herpesvirus genome in the third step.

In the following two sections, we will describe two examples in which our group successfully used linker-scanning transposon mutagenesis to identify DN mutants of M50 and M53 of MCMV.

7. Conclusions and Perspectives

Besides ongoing research in the herpesviral field and intense studies on genes with unknown functions, the role of the corresponding proteins are still elusive. One major problem of some proteins is that they participate in multiple processes, making studies of their function difficult. Deletion of a gene will result in a complex phenotype which is hard to explore. Here, DN mutants might be invaluable tools to dissect the function of multifunctional proteins. As described above, DNs can poison a whole complex and arrest it at a certain stage, but might allow all other functions of the protein. This could help to resolve highly dynamic processes.

Availability, of an appropriate DN is of course fundamental for this kind of studies. In this manuscript, we mentioned several possibilities to create DNs. Furthermore, we showed that a linker-scanning transposon mutagenesis is an attractive method to generate sets of DN proteins which in the case of the proteins M50 and M53 of MCMV helped us to elucidate part of their function. Due to the progresses in herpesvirus genetics, manipulation of the herpesvirus genome encoded in BACs and so providing DNs in cis is a simple procedure.

Trans-complementation of herpesviral DNs, termed intracellular immunization, is a versatile and promising experimental strategy which deserves further study. This concept proposes that expression of a DN protein could inhibit viral replication to generate viral resistance within a cell or a host. Within this manuscript we reviewed the first and important steps of intracellular immunization within the herpesviral field. The DNs in these proof-of-principle experiments are still associated with negative effects on the host. Therefore, further refinements are needed in order to make the procedure be generally applicable for creating herpesviral resistant lifestock. A virus inducible expression system, which provides the DN only in infected cells and at the time point of infection, may represent the solution.

Acknowledgments

The work of the group referred to is supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft through SFB455 and SPP 1175.

References and Notes

- Roizman, B.; Baines, J. The Diversity and Unity of Herpes-Viridae. Comp. Immunol. Microb. 1991, 2, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, M.; Deng, R.; Wang, J.; Wang, X. Whole-Genome Phylogenetic Analysis of Herpesviruses. Acta Virol. 2008, 1, 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Davison, A.J. Evolution of the herpesviruses. Vet. Microbiol. 2002, 1-2, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGeoch, D.J.; Rixon, F. J.; Davison, A.J. Topics in herpesvirus genomics and evolution. Virus Res. 2006, 1, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcami, A.; Koszinowski, U.H. Viral mechanisms of immune evasion. Immunol. Today 2000, 9, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, I.; Nishiyama, Y. Herpes simplex virus and varicella-zoster virus: why do these human alphaherpesviruses behave so differently from one another? Rev. Med. Virol. 2005, 6, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andoniou, C.E.; Degli-Esposti, M.A. Insights into the mechanisms of CMV-mediated interference with cellular apoptosis. Immunol. Cell. Biol. 2006, 1, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matis, J.; Kudelova, M. Early shutoff of host protein synthesis in cells infected with herpes simplex viruses. Acta. Virol. 2001, 5-6, 269–277. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, W.; Chou, C.; Li, H.; Hai, R.; Patterson, D.; Stolc, V.; Zhu, H.; Liu, F.Y. Functional profiling of a human cytomegalovirus genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 2003, 24, 14223–14228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herskowitz, I. Functional Inactivation of Genes by Dominant Negative Mutations. Nature 1987, 6136, 219–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Baldi, P.F.; Gaut, B.S. Phylogenetic analysis, genome evolution and the rate of gene gain in the Herpesviridae. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2007, 3, 1066–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montague, M.G.; Hutchison, C.A. Gene content phylogeny of herpesviruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 2000, 10, 5334–5339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellett, P.E.; Roizman, B. The Family Herpesviridae: A Brief Introduction. 2007, 66, 2479–2499. [Google Scholar]

- Salsman, J.; Zimmerman, N.; Chen, T.; Domagala, M.; Frappier, L. Genome-wide screen of three herpesviruses for protein subcellular localization and alteration of PML nuclear bodies. Plos Pathogens 2008, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Sweet, C.; Ball, K.; Morley, P.J.; Guilfoyle, K.; Kirby, M. Mutations in the temperature-sensitive murine cytomegalovirus (MCMV) mutants tsm5 and tsm30: A study of genes involved in immune evasion, DNA packaging and processing, and DNA replication. J. Med. Virol. 2007, 3, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benyesh-Melnick, M.; Schaffer, P.A.; Courtney, R.J.; Esparza, J.; Kimura, S. Viral gene functions expressed and detected by temperature-sensitive mutants of herpes simplex virus. Cold Spring Harb.Symp. Quant. Biol. 1975, 731–746. [Google Scholar]

- Akel, H.M.O.; Sweet, C. Isolation and Preliminary Characterization of 25 Temperature-Sensitive Mutants of Mouse Cytomegalovirus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1993, 3, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, G.; Revello, M.G.; Patrone, M.; Percivalle, E.; Campanini, G.; Sarasini, A.; Wagner, M.; Gallina, A.; Milanesi, G.; Koszinowski, U.; Baldanti, F.; Gerna, G. Human cytomegalovirus UL131-128 genes are indispensable for virus growth in endothelial cells and virus transfer to leukocytes. J. Virol. 2004, 18, 10023–10033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocarski, E.S.; Post, L.E.; Roizman, B. Molecular Engineering of the Herpes-Simplex Virus Genome - Insertion of A Second L-S Junction Into the Genome Causes Additional Genome Inversions. Cell 1980, 1, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messerle, M.; Crnkovic, I.; Hammerschmidt, W.; Ziegler, H.; Koszinowski, U.H. Cloning and mutagenesis of a herpesvirus genome as an infectious bacterial artificial chromosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 1997, 26, 14759–14763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brune, W.; Messerle, M.; Koszinowski, U.H. Forward with BACs - new tools for herpesvirus genomics. Trends Genet. 2000, 6, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, H.; Messerle, M.; Koszinowski, U.H. Cloning of herpesviral genomes as bacterial artificial chromosomes. Rev. Med. Virol. 2003, 2, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brune, W.; Menard, C.; Hobom, U.; Odenbreit, S.; Messerle, M.; Koszinowski, U.H. Rapid identification of essential and nonessential herpesvirus genes by direct transposon mutagenesis. Nature Biotech. 1999, 4, 360–364. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, D.; Silva, M.C.; Shenk, T. Functional map of human cytomegalovirus AD169 defined by global mutational analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 2003, 21, 12396–12401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobom, U.; Brune, W.; Messerle, M.; Hahn, G.; Koszinowski, U.H. Fast screening procedures for random transposon libraries of cloned herpesvirus genomes: Mutational analysis of human cytomegalovirus envelope glycoprotein genes. J. Virol. 2000, 17, 7720–7729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.A.; Enquist, L.W. Construction and transposon mutagenesis in Escherichica coli of a full-length infectious clone of pseudorabies virus, an alphaherpesvirus. J. Virol. 1999, 8, 6405–6414. [Google Scholar]

- Menard, C.; Wagner, M.; Ruzsics, Z.; Holak, K.; Brune, W.; Campbell, A.E.; Koszinowski, U.H. Role of murine cytomegalovirus US22 gene family members in replication in macrophages. J. Virol. 2003, 10, 5557–5570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brune, W.; Menard, C.; Heesemann, J.; Koszinowski, U.H. A ribonucleotide reductase homolog of cytomegalovirus and endothelial cell tropism. Science 2001, 5502, 303–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzsics, Z.; Wagner, M.; Osterlehner, A.; Cook, J.; Koszinowski, U.; Burgert, H.G. Transposon-assisted cloning and traceless mutagenesis of adenoviruses: Development of a novel vector based on species D. J. Virol. 2006, 16, 8100–8113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tischer, B.K.; von Einem, J.; Kaufer, B.; Osterrieder, N. Two-step Red-mediated recombination for versatile high-efficiency markerless DNA manipulation in Escherichia coli. Biotechniques 2006, 2, 191–197. [Google Scholar]

- Bubic, I.; Wagner, M.; Krmpotic, A.; Saulig, T.; Kim, S.; Yokoyama, W.M.; Jonjic, S.; Koszinowski, U.H. Gain of virulence caused by loss of a gene in murine cytomegalovirus. J. Virol. 2004, 14, 7536–7544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champier, G.; Hantz, S.; Couvreux, A.; Stuppfler, S.; Mazeron, M.C.; Bouaziz, S.; Denis, F.; Alain, S. New functional domains of human cytomegalovirus pUL89 predicted by sequence analysis and three-dimensional modelling of the catalytic site DEXDc. Antiviral Ther. 2007, 2, 217–232. [Google Scholar]

- Holzerlandt, R.; Orengo, C.; Kellam, P.; Alba, M.M. Identification of new herpesvirus gene homologs in the human genome. Genome Res. 2002, 11, 1739–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottcher, S.; Klupp, B.G.; Granzow, H.; Fuchs, W.; Michael, K.; Mettenleiter, T.C. Identification of a 709-amino-acid internal nonessential region within the essential conserved tegument protein (p)UL36 of pseudorabies virus. J. Virol. 2006, 19, 9910–9915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veitia, R.A. Exploring the molecular etiology of dominant-negative mutations. Plant Cell 2007, 12, 3843–3851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veitia, R.A. Dominant negative factors in health and disease. J. Pathol. 2009, 218, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujita, H.; Yamanaka, M.; Imamura, K.; Tanaka, Y.; Nara, A.; Yoshimori, T.; Yokota, S.; Himeno, M. A dominant negative form of the AAA ATPase SKD1/VPS4 impairs membrane trafficking out of endosomal/lysosomal compartments: class E vps phenotype in mammalian cells. J. Cell. Sci. 2003, 2, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendershot, L.M.; Wei, J.Y.; Gaut, J.R.; Melnick, J.; Aviel, S.; Argon, Y. Inhibition of Immunoglobulin Folding and Secretion by Dominant-Negative Bip Atpase Mutants. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1995, 375–375. [Google Scholar]

- Tabancay, A.P.; Gau, C.L.; Machado, I.M.P.; Uhlmann, E.J.; Gutmann, D.H.; Guo, L.; Tamanoi, F. Identification of dominant negative mutants of Rheb GTPase and their use to implicate the involvement of human Rheb in the activation of p70S6K. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 41, 39921–39930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, A.L.; Hall, A. Rho GTPases and their effector proteins. Biochem. J. 2000, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Frade, J.M.; Vila-Coro, A.J.; de Ana, A.M.; Albar, J.P.; Martinez, A.; Mellado, M. The chemokine monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 induces functional responses through dimerization of its receptor CCR2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 1999, 7, 3628–3633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldenhoven, E.; vanDijk, T.B.; Solari, R.; Armstrong, J.; Raaijmakers, J.A.M.; Lammers, J.W.J.; Koenderman, L.; deGroot, R.P. STAT3 beta, a splice variant of transcription factor STAT3, is a dominant negative regulator of transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 22, 13221–13227. [Google Scholar]

- Barren, B.; Artemyev, N.O. Mechanisms of dominant negative G-protein alpha subunits. J. Neurosci. Res. 2007, 16, 3505–3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, A.; Jung, E.J.; Wakefield, T.; Chen, X.B. Mutant p53 exerts a dominant negative effect by preventing wild-type p53 from binding to the promoter of its target genes. Oncogene 2004, 13, 2330–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fire, A.; Xu, S.Q.; Montgomery, M.K.; Kostas, S.A.; Driver, S.E.; Mello, C.C. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 1998, 6669, 806–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinshaw, J.E. Dynamin and its role in membrane fission. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2000, 16, 483–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damke, H.; Baba, T.; Warnock, D.E.; Schmid, S.L. Induction of Mutant Dynamin Specifically Blocks Endocytic Coated Vesicle Formation. J. Cell. Biol. 1994, 4, 915–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damke, H.; Binns, D.D.; Ueda, H.; Schmid, S.L.; Baba, T. Dynamin GTPase domain mutants block endocytic vesicle formation at morphologically distinct stages. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2001, 9, 2578–2589. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, A.; Frank, D.W.; Marks, M.S.; Lemmon, M.A. Dominant-negative inhibition of receptor-mediated endocytosis by a dynamin-1 mutant with a defective pleckstrin homology domain. Curr. Biol. 1999, 5, 261–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achiriloaie, M.; Barylko, B.; Albanesi, J.P. Essential role of the dynamin pleckstrin homology domain in receptor-mediated endocytosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999, 2, 1410–1415. [Google Scholar]

- Szaszak, M.; Gaborik, Z.; Turu, G.; McPherson, P.S.; Clark, A.J.L.; Catt, K.J.; Hunyady, L. Role of the proline-rich domain of dynamin-2 and its interactions with Src homology 3 domains during endocytosis of the AT(1) angiotensin receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 24, 21650–21656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, B.; Stowell, M.H.B.; Vallis, Y.; Mills, I.G.; Gibson, A.; Hopkins, C.R.; McMahon, H.T. GTPase activity of dynamin and resulting conformation change are essential for endocytosis. Nature 2001, 6825, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daecke, J.; Fackler, O.T.; Dittmar, M.T.; Krausslich, H.G. Involvement of clathrin-mediated endocytosis in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 entry. J. Virol. 2005, 3, 1581–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoden, G.; Freitag, K.; Husmann, M.; Boller, K.; Sapp, M.; Lambert, C.; Florin, L. Clathrin- and caveolin-independent entry of human papillomavirus type 16--involvement of tetraspanin-enriched microdomains (TEMs). PLoS One 2008, 10, e3313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heldwein, E.E.; Krummenacher, C. Entry of herpesviruses into mammalian cells. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2008, 11, 1653–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheshenko, N.; Liu, W.; Satlin, L.M.; Herold, B.C. Focal adhesion kinase plays a pivotal role in herpes simplex virus entry. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 35, 31116–31125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veettil, M.V.; Sharma-Walia, N.; Sadagopan, S.; Raghu, H.; Sivakumar, R.; Naranatt, P.P.; Chandran, B. RhoA-GTPase facilitates entry of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus into adherent target cells in a Src-dependent manner. J. Virol. 2006, 23, 11432–11446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma-Walia, N.; Naranatt, P.P.; Krishnan, H.H.; Zeng, L.; Chandran, B. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus/human herpesvirus 8 envelope glycoprotein gB induces the integrin-dependent focal adhesion kinase-Src-phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-Rho GTPase signal pathways and cytoskeletal rearrangements. J. Virol. 2004, 8, 4207–4223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, H.H.; Sharma-Walia, N.; Streblow, D.N.; Naranatt, P.P.; Chandran, B. Focal adhesion kinase is critical for entry of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus into target cells. J. Virol. 2006, 3, 1167–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Advani, S.J.; Weichselbaum, R.R.; Roizman, B. The role of cdc2 in the expression of herpes simplex virus genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 2000, 20, 10996–11001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.D.; Roizman, B. The degradation of promyelocytic leukemia and Sp100 proteins by herpes simplex virus 1 is mediated by the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme UbcH5a. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 2003, 15, 8963–8968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicin-Sain, L.; Ruzsics, Z.; Podlech, J.; Bubic, I.; Menard, C.; Jonjic, S.; Reddehase, M.J.; Koszinowski, U.H. Dominant-negative FADD rescues the in vivo fitness of a cytomegalovirus lacking an antiapoptotic viral gene. J. Virol. 2008, 5, 2056–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, M.S.; Hall, K.T.; Whitehouse, A. The herpesvirus saimiri open reading frame (ORF) 50 (Rta) protein contains an AT hook required for binding to the ORF 50 response element in delayed-early promoters. J. Virol. 2004, 9, 4936–4942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossetto, C.; Yamboliev, I.; Pari, G.S. Kaposi's Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus/Human Herpesvirus 8 K-bZIP modulates LANA mediated suppression of lytic origin-dependent DNA synthesis. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 8492–8501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNamee, E.E.; Taylor, T.J.; Knipe, D.M. A dominant-negative herpesvirus protein inhibits intranuclear targeting of viral proteins: Effects on DNA replication and late gene expression. J. Virol. 2000, 21, 10122–10131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, S.; Ono, E.; Shimizu, Y.; Kida, H. Mapping of transregulatory domains of pseudorabies virus early protein 0 and identification of its dominant-negative mutant. Arch. Virol. 1996, 6, 1001–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.K.; Ahn, B.C.; Albrecht, R.A.; O'Callaghan, D.J. The unique IR2 protein of equine herpesvirus 1 negatively regulates viral gene expression. J. Virol. 2006, 10, 5041–5049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchmaier, A.L.; Sugden, B. Dominant-negative inhibitors of EBNA-1 of Epstein-Barr virus. J. Virol. 1997, 3, 1766–1775. [Google Scholar]

- Marintcheva, B.; Weller, S.K. Existence of transdominant and potentiating mutants of UL9, the herpes simplex virus type 1 origin-binding protein, suggests that levels of UL9 protein may be regulated during infection. J. Virol. 2003, 17, 9639–9651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivo, P.D.; Nelson, N.J.; Challberg, M.D. Herpes-Simplex Virus-Dna Replication - the Ul9 Gene Encodes An Origin-Binding Protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 1988, 15, 5414–5418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, F.; Eriksson, E. A novel anti-herpes simplex virus type 1-specific herpes simplex virus type 1 recombinant. Hum. Gene Ther. 1999, 11, 1811–1818. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, F.; Eriksson, E. Inhibition of herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) viral replication by the dominant negative mutant polypeptide of HSV-1 origin binding protein. Antiviral Res. 2002, 2, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustinova, H.; Hoeller, D.; Yao, F. The dominant-negative herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) recombinant CJ83193 can serve as an effective vaccine against wild-type HSV-1 infection in mice. J. Virol. 2004, 11, 5756–5765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brans, R.; Eriksson, E.; Yao, F. Immunization with a Dominant-Negative Recombinant HSV Type 1 Protects against HSV-1 Skin Disease in Guinea Pigs. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2008, 12, 2825–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prockop, D.J.; Kivirikko, K.I. Collagens - Molecular-Biology, Diseases, and Potentials for Therapy. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1995, 403–434. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, A.D.; Triezenberg, S.J.; Mcknight, S.L. Expression of A Truncated Viral Trans-Activator Selectively Impedes Lytic Infection by Its Cognate Virus. Nature 1988, 6189, 452–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, P.C.; Wigdahl, B. Identification of Dominant-Negative Mutants of the Herpes-Simplex Virus Type-1 Immediate-Early Protein-Icp0. J. Virol. 1992, 4, 2261–2267. [Google Scholar]

- Borst, E.M.; Mathys, S.; Wagner, M.; Muranyi, W.; Messerle, M. Genetic evidence of an essential role for cytomegalovirus small capsid protein in viral growth. J. Virol. 2001, 3, 1450–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzmayer, T.A.; Pestov, D.G.; Roninson, I.B. Isolation of Dominant Negative Mutants and Inhibitory Antisense Rna Sequences by Expression Selection of Random Dna Fragments. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992, 4, 711–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, G.J.; Harley, C.; Boyd, A.; Morgan, A. A screen for dominant negative mutants of SEC18 reveals a role for the AAA protein consensus sequence in ATP hydrolysis. Mol. Biol. Cell 2000, 4, 1345–1356. [Google Scholar]

- Crowder, S.; Kirkegaard, K. Trans-dominant inhibition of RNA viral replication can slow growth of drug-resistant viruses. Nature Genet. 2005, 7, 701–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, B.C.; Wells, J.A. High-Resolution Epitope Mapping of Hgh-Receptor Interactions by Alanine-Scanning Mutagenesis. Science 1989, 4908, 1081–1085. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, D.K.; Garbers, D.L. Dominant-Negative Mutations of the Guanylyl Cyclase-A Receptor - Extracellular Domain Deletion and Catalytic Domain Point Mutations. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 1, 425–430. [Google Scholar]

- Steel, G.J.; Harley, C.; Boyd, A.; Morgan, A. A screen for dominant negative mutants of SEC18 reveals a role for the AAA protein consensus sequence in ATP hydrolysis. Mol. Bio. Cell 2000, 4, 1345–1356. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, F. Transposon-based strategies for microbial functional genomics and proteomics. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2003, 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzsics, Z.; Koszinowski, U.H. Mutagenesis of the cytomegalovirus genome. In Human Cytomegalovirus. Shenk, T., Stinki, M.F., Eds.; 2008; Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Bubeck, A.; Wagner, M.; Ruzsics, Z.; Lotzerich, M.; Iglesias, M.; Singh, I.R.; Koszinowski, U.H. Comprehensive mutational analysis of a herpesvirus gene in the viral genome context reveals a region essential for virus replication. J. Virol. 2004, 15, 8026–8035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotzerich, M.; Ruzsics, Z.; Koszinowski, U.H. Functional domains of murine cytomegalovirus nuclear egress protein M53/p38. J. Virol. 2006, 1, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, B.; Ruzsics, Z.; Sacher, T.; Koszinowski, U.H. Conditional cytomegalovirus replication in vitro and in vivo. J. Virol. 2005, 1, 486–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, B.; Ruzsics, Z.; Buser, C.; Adler, B.; Walther, P.; Koszinowski, U.H. Random screening for dominant-negative mutants of the cytomegalovirus nuclear egress protein M50. J. Virol. 2007, 11, 5508–5517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granato, M.; Feederle, R.; Farina, A.; Gonnella, R.; Santarelli, R.; Hub, B.; Faggioni, A.; Delecluse, H.J. Deletion of Epstein-Barr virus BFLF2 leads to impaired viral DNA packaging and primary egress as well as to the production of defective viral particles. J. Virol. 2008, 8, 4042–4051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapik, Y.R.; Fernandes, C.J.; Lau, L.F.; Pestov, D.G. Physical and functional interaction between pes1 and bop1 in mammalian ribosome biogenesis. Mol. Cell 2004, 1, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osawa, M.; Erickson, H.P. Probing the domain structure of FtsZ by random insertional mutagenesis. Mol. Bio. Cell 2004, 292A–293A. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, E.; Koebnik, R. Domain structure of HrpE, the Hrp pilus subunit of Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria. J. Bacteriol. 2005, 17, 6175–6186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.G.; Zhou, J.; Jones, C. Identification of functional domains within the bICP0 protein encoded by bovine herpesvirus 1. J. Gen. Virol. 2005, 879–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockrell, S.K.; Sanchez, M.E.; Erazo, A.; Homa, F.L. Role of the UL25 Protein in Herpes Simplex Virus DNA Encapsidation. J. Virol. 2009, 1, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, E.; Spear, P.G. Random linker-insertion mutagenesis to identify functional domains of herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoprotein B. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 2007, 32, 13140–13145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, D.J. Endogenous retroviruses in the human genome sequence. Genome Biol. 2001, 2, reviews1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Best, S.; Le Tissier, P.; Towers, G.; Stoye, J.P. Positional cloning of the mouse retrovirus restriction gene Fv1. Nature 1996, 6594, 826–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnaud, F.; Varela, M.; Spencer, T.E.; Palmarini, M. Coevolution of endogenous betaretroviruses of sheep and their host. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2008, 21, 3422–3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmarini, M.; Mura, M.; Spencer, T.E. Endogenous betaretroviruses of sheep: teaching new lessons in retroviral interference and adaptation. J. Gen. Virol. 2004, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltimore, D. Gene-Therapy - Intracellular Immunization. Nature 1988, 6189, 395–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trono, D.; Feinberg, M.B.; Baltimore, D. Hiv-1 Gag Mutants Can Dominantly Interfere with the Replication of the Wild-Type Virus. Cell 1989, 1, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahner, I.; Sumiyoshi, T.; Kagoda, M.; Swartout, R.; Peterson, D.; Pepper, K.; Dorey, F.; Reiser, J.; Kohn, D.B. Lentiviral vector transduction of a dominant-negative rev gene into human CD34(+) hematopoietic progenitor cells potently inhibits human immunodeficiency virus-1 replication. Mol. Ther. 2007, 1, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunner, W.H.; Pallatroni, C.; Curtis, P.J. Selection of genetic inhibitors of rabies virus. Arch. Virol. 2004, 8, 1653–1662. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, C.; Chowdhury, S. A review of the biology of bovine herpesvirus type 1 (BHV-1), its role as a cofactor in the bovine respiratory disease complex and development of improved vaccines. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2007, 2, 187–205. [Google Scholar]

- Gimeno, I.M. Marek's disease vaccines: A solution for today but a worry for tomorrow? Vaccine 2008, C31–C41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, A.J.; Eberle, R.; Ehlers, B.; Hayward, G.S.; McGeoch, D.J.; Minson, A.C.; Pellett, P.E.; Roizman, B.; Studdert, M.J.; Thiry, E. The order Herpesvirales. Arch. Virol. 2009, 1, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.A.; Deluca, N.A. Transdominant Inhibition of Herpes-Simplex Virus Growth in Transgenic Mice. Virology 1992, 2, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, E.; Sakoda, Y.; Taharaguchi, S.; Watanabe, S.; Tonomura, N.; Kida, H.; Shimizu, Y. Inhibition of Pseudorabies Virus-Replication by A Chimeric Trans-Gene Product Repressing Transcription of the Immediate-Early Gene. Virology 1995, 1, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, E.; Tasaki, T.; Kobayashi, T.; Taharaguchi, S.; Nikami, H.; Miyoshi, I.; Kasai, N.; Arikawa, J.; Kida, H.; Shimizu, Y. Resistance to pseudorabies virus infection in transgenic mice expressing the chimeric transgene that represses the immediate-early gene transcription. Virology 1999, 1, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasaki, T.; Taharaguchi, S.; Kobayashi, T.; Yoshino, S.; Ono, E. Inhibition of pseudorabies virus replication by a dominant-negative mutant of early protein 0 expressed in a tetracycline-regulated system. Vet. Microbiol. 2001, 3, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2009 by the authors; licensee Molecular Diversity Preservation International, Basel, Switzerland This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.