Abstract

Understanding how climatic variability affects growth and water relations of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) is essential for assessing stand sustainability in hemi-boreal regions. Linear mixed-effects models were used to quantify the effects of climatic variability and tree characteristics on stem volume increment (ZV), sap flow (SF), and water-use efficiency (WUE) of Scots pine growing on highly oligotrophic soils in Curonian Spit National Park. Annual ZV was strongly controlled by tree size and seasonal temperature conditions. Higher temperatures in late winter and mid-summer enhanced growth, whereas elevated temperatures in April–May reduced increment. June moisture availability, expressed by the hydrothermal coefficient, had a positive effect, highlighting the sensitivity of growth to early-summer drought and heat waves. Sap-flow density during May–October was primarily driven by climatic factors, with temperature stimulating and relative humidity reducing SF, while tree size played a minor role. Random-effects analysis showed that unexplained variability in ZV was mainly associated with persistent differences among trees and sites, whereas SF variability occurred largely at the within-tree level. In contrast, WUE was dominated by climatic drivers, with no detectable site- or tree-level random effects. Higher June precipitation increased WUE, while warmer growing-season conditions reduced it. Overall, Scots pine growth and WUE are mainly regulated by intra-annual climatic conditions, particularly summer water availability. Despite rapid climatic change, no critical physiological thresholds or growth collapse were detected during the study period, indicating substantial adaptive capacity of Scots pine even under the observed exceptional conditions.

1. Introduction

Forests are increasingly exposed to intensified climatic pressures, particularly prolonged and severe droughts driven by global warming [1]. These conditions have been linked to reduced forest productivity and increased tree mortality [2,3,4,5]. Forest ecosystems show varying degrees of resistance, tolerance, and adaptation to these stresses, which can result from structural, physiological, or combined adjustments. However, the increasing frequency and intensity of extreme events—such as droughts, heatwaves, and unseasonal temperature fluctuations—may push forest ecosystems beyond their resilience thresholds. In temperate regions, repeated drought events have been shown to reduce gross primary productivity and compromise tree vitality [6,7].

In response to aridification, forest productivity and tree growth may also become more dependent on soil moisture [8] and water evaporative demand [9]. Additionally, severe drought can reduce growth resilience and increase tree mortality risk [10,11]. In this context, water use efficiency (WUE)—the ratio of carbon gained through photosynthesis to water lost via transpiration—has become a key parameter for evaluating forest responses to climate change. The WUE of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.), in particular, is influenced by climatic variables such as temperature, precipitation, and vapor pressure deficit (VPD), all of which interact to shape tree physiological processes [12].

The relationship between winter temperatures and Scots pine growth has also attracted increasing scientific interest. Harvey et al. [13] demonstrated that rising winter temperatures can stimulate growth in northern temperate forests by enabling the earlier resumption of physiological activity. However, these potential benefits are often offset by increased susceptibility to summer droughts. Therefore, the interplay between winter warming and drought vulnerability is critical to understanding the health and productivity of Scots pine forests, in which rising winter temperatures may heighten the susceptibility of Scots pine to summer drought conditions [14]. Such conditions are exemplified by Lithuania’s Curonian Spit pine forest.

The Curonian Spit National Park is situated between the Baltic Sea to the west and the Curonian Lagoon to the east. Scots pine forests growing on the wind-formed sandy dunes are characterized by nutrient-poor soils, an extended vegetation period, and unusually warm winters due to the moderating influence of the surrounding waters. The sandy, nutrient-poor substrates limit water retention and nutrient availability, making trees on these sites particularly sensitive to heat and drought events [15,16]. Understanding how climatic drivers and soil constraints interact to influence tree growth and water-use strategies is therefore critical for predicting forest responses under future climate scenarios. These conditions provide a unique opportunity to investigate the adaptive strategies of Scots pine trees under shifting climatic regimes. In this study, we aimed to assess transpiration dynamics, stem growth patterns, and water-use efficiency (WUE) in Scots pine trees in this region from 2018 to 2024, with particular focus on their lagged response to warmer winters and their direct response to summer droughts.

Given current knowledge gaps, we aimed to identify the key meteorological factors most significantly affecting the primary ecophysiological responses of Scots pine trees under extremely poor growing conditions, in order to evaluate their adaptive capacity to recent climatic changes. To meet the aim of the studies following objectives were drawn:

- -

- Identify the key meteorological factors influencing sap flow density in Scots pine trees under arid conditions.

- -

- Examine the effects of extreme meteorological events on seasonal pine stem growth.

- -

- Assess the physiological responses of Scots pine trees to heat and drought following mild winters.

- -

- Evaluate the adaptive capacity of Scots pine trees to climate-induced extremes in nutrient-poor soils in the hemi-boreal zone.

The insights gained from this research enhance our understanding of Scots pine trees ecophysiological responses to extreme weather and their resistance thresholds, thereby informing forest management and supporting climate change adaptation strategies in hemi-boreal ecosystems.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Location, Forest Type and Study Characteristics

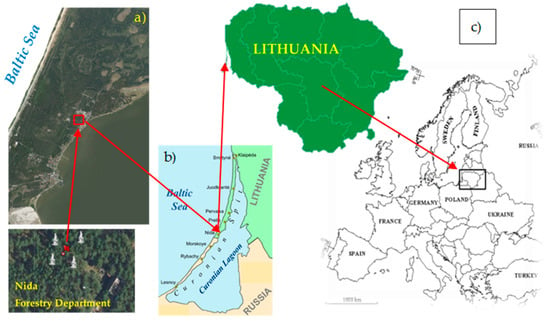

This study was conducted on Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) trees growing in the coastal forests of the Lithuanian Curonian Spit National Park, within the Nida Forest Enterprise area [17]. This site is characterized by extremely nutrient-poor, wind-formed sandy soils, among the poorest in the region for tree growth (Figure 1). The ecophysiological responses of the trees were investigated over the period from 2018 to 2024.

Figure 1.

Location of the monitored Scots pine trees in Lithuania: WGS 55.320056, 21.019015; (a) detailed satellite view; (b) local seaside view; and (c) regional East European view. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Curonian_Spit#/media/File:Curonian_Spit_and_Lagoon.png accessed on 5 January 2026.

Forest type: Oligotrophic forest on mineral soil’. The soil is classified as haplic arenosol, with the groundwater table located deeper than 2 m. Scots pine dominates the upper canopy layer. The herbaceous layer includes Vaccinium vitis-idaea and Pleurozium schreberi.

Four subplots of the same pure, middle-aged Scots pine stand, each containing at least 2–3 approximately 60-year-old pine trees, were selected for monitoring to meet the objectives of the study. The breast-height diameter of the monitored trees varied between 19 and 29 cm, tree height between 15 and 16 m, and volume between 0.2 and 0.4 m3.

2.2. Meteorological Parameters

Meteorological data were obtained from the Nida Meteorological Station, operated by the Lithuanian Hydrometeorological Service [18]. The following parameters were recorded at one-hour intervals: wind speed (m/s) and direction (azimuth °), atmospheric pressure (hPa), precipitation (mm), relative humidity (%), air temperature (mean, maximum, minimum—°C), and solar radiation (W/m2).

To estimate the drying power of the air, the vapor pressure deficit was calculated based on relative humidity (RH) and temperature (Tm), using the following equation [19]:

where RH (%) is relative humidity, and SVP (hPa) is the saturated vapor pressure.

SVP (es) was calculated using the Magnus formula as follows [19]:

2.3. Xylem Sap Flow and Heat-Pulse Method

The sap flow index was selected as a primary tool to assess tree water exchange dynamics and eco-physiological sensitivity to moisture deficits and heatwaves. It captures the immediate physiological response of trees to atmospheric and soil moisture stress, integrates multiple tree traits and can serve as an indicator of plant health and water use under hotter and drier conditions [19,20].

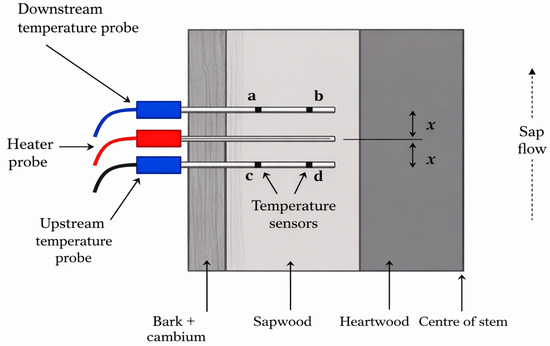

Xylem sap flow was measured using the heat ratio method (HRM) described by Burgess et al. [21], employing a sap flow meter from ICT International [22]. Sensors were installed at approximately 120 cm above ground level and were covered with aluminum foil to minimize external temperature effects. Bark thickness was measured on each sample tree using a bark depth gauge, and sensor needles were inserted into the sapwood at two different depths, with the bark either removed or adjusted using a spacer for a standard depth of 10 mm. The HRM technique involves inserting probes into the tree’s xylem: one generates a heat pulse, while adjacent probes measure the temperature response (Figure 2). The time required for heat to travel between probes is used to calculate sap flow velocity. This method can measure both high and low sap flow rates, making it highly adaptable for various research applications [23]. This method is relatively non-invasive, allowing for repeated measurements without causing significant damage to the tree. It provides real-time data on sap flow, enabling researchers to monitor changes in water transport in response to environmental conditions.

Figure 2.

Heat ratio-pulse method (HRM) [22].

The SFM1 sap flow sensors stored data as raw temperature values. These were converted into the sap density rate, and total plant water use was determined using the International Sap Flow Tool software Version 1.4 (2016) of the Information and Communication Technology (for HFD and HRM data) [22], calibrated for Scots pine sapwood properties.

Sap flow was continuously monitored from 2018 to 2024 at 15 min intervals using a heating power of 20 joules. Crown transpiration was calculated by multiplying the mean daily sap flow density by the basal area of each sample tree [19,24,25].

2.4. Pine Stem Increment and WUE

Stem volume increment was selected as a key indicator because it integrates the long-term physiological response of trees to environmental conditions and serves as a robust metric of productivity and vitality. As a direct measure of growth, it enables assessment of actual biomass accumulation and long-term tree stability under varying ecological and climatic stresses, particularly heatwaves and drought [26,27].

Stem growth was measured using both manual and high-resolution electronic dendrometers (DRL26, EMS Brno, Brno, Czech Republic), with accuracies of ±0.1 mm and ±0.001 mm, respectively. Stem volume increment was calculated from stem circumference growth, incorporating tree height and the stem form index, with the diameter at 1.3 m height enlarged.

Water-use efficiency (WUE) was selected as a key indicator to assess the adaptive capacity of trees under environmental extremes [12,28,29]. It reflects survival strategies by indicating how effectively trees optimize water use for carbon assimilation (growth) processes and represents a rapid physiological response to changing climatic conditions.

WUE was calculated as the ratio of stem volume increment to sap flow density, representing the amount of structural biomass produced per unit of water transpired, and vice versa. Higher WUE values indicate more efficient carbon gain per liter of water used, or less water required per unit of carbon gained.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Trends in pine stem volume increment, sap flow density, and water-use efficiency were analyzed using data from 10 trees across four subplots over seven years (n = 70). Initial relationships with meteorological variables were assessed via Pearson’s correlation (p < 0.05). Linear mixed-effects models (lmer, lme4; lmerTest) were fitted with maximum likelihood, including tree diameter, temperature, and precipitation as fixed effects. Random effects accounted for hierarchical structure, with individual trees nested within sites (Tree_N within Site_N), and “Year” included where relevant to assess interannual variability. Model fit was evaluated using AIC, BIC, and log-likelihood, while residual diagnostics confirmed normality and homoscedasticity. Variance components of random effects, residuals, and marginal (R2m) versus conditional R2 (R2c) were calculated to quantify hierarchical contributions [30]. Predicted values were generated with the predict function in R Core Team software version 4.4.2 (2024), enabling robust assessment of both environmental drivers and tree- and site-level variability [31].

3. Results

This study provides an integrated assessment of Scots pine responses to interannual climatic variability under extremely oligotrophic soil conditions in hemi-boreal forests. By jointly analyzing annual stem volume increment (ZV), sap flow density (SF), and water-use efficiency (WUE), both structural and physiological dimensions of pine performance are captured across years with contrasting meteorological conditions.

3.1. Meteorological Conditions and Their Characteristics

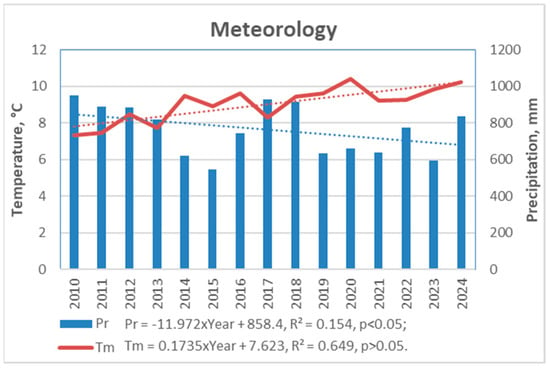

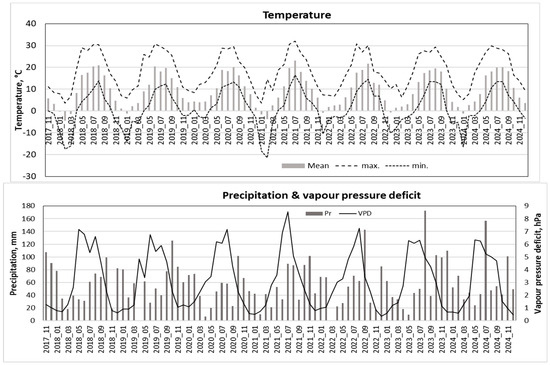

The analysis of meteorological data from the past 15 years enabled the identification of the most contrasting and extreme weather events, with particular attention focused on the study period from 2018 to 2024 (Figure 3). This approach allowed for the evaluation of short-term trends in the study period in relation to longer-term patterns.

Figure 3.

Annual data of the main meteorological parameters in Curonian Spit National Park over 2010–2024 period based on data from the Nida Meteorological Station [18].

No significant regular changes in precipitation (Pr) were observed during the 15-year period, when the amount of Pr showed a tendency to decrease by −12 mm per year. During the period of investigation, there was a tendency for it to decrease by −16 mm per year (p > 0.05).

A substantial increase in air temperature (Tm) was detected over both the 7-year study and the longer 15-year period, indicating a pronounced significant warming trend. The increase in mean air temperature exceeded 1.7 °C per 10 years for this region.

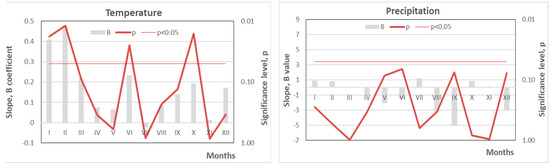

Between 2010 and 2024, average monthly Tm in June and October increased at a rate of over 2.0 °C per 10 years, while January and February saw an even steeper rise—exceeding 4.0 °C per 10 years (Figure 4). If this trend continues, forest ecosystems in the region may face catastrophic consequences. Notably, the mean Tm in January and February rose from approximately −5 °C in 2010 to +1 °C in 2023–2024—an increase of 6 °C in just 15 years, far exceeding existing climate projections.

Figure 4.

The intensity of the changes in mean monthly temperature and precipitation (B coefficient and its significance, p) over the last 15-year period (2010–2024) at the Curonian Spit National Park, based on data from the Nida Meteorological Station [18].

In parallel, this rapid Tm increase was accompanied by declining Pr, particularly in May, June, September, and December. Reductions of 3–5 mm per year were observed, with near-significant trends (p ≈ 0.05). These decreases in rainfall may amplify the negative effects of heatwaves during the growing season, intensifying water stress and further challenging forest stability (Figure 3).

The highest annual Pr was recorded in 2017, one year before the start of this study (Table 1). During the investigation period (2018–2024), annual Pr ranged from 600 to 700 mm, which was close to the long-term average. In terms of mean annual Tm, 2020 and 2024 were the warmest years, both with values exceeding 10 °C. The most intense heatwave occurred in 2021, which paradoxically also ranked among the coldest years in this study, with a annual Tm below 9 °C and a recorded minimum of −21.4 °C (Figure 5).

Table 1.

Annual values of the main meteorological parameters during the 2018–2024 period.

Figure 5.

Seasonal variation in monthly average temperature, vapor pressure deficit (VPD), and total monthly precipitation over the 2018–2024 period.

The mean monthly meteorological values indicated that June to August were the warmest months at the study site, with average temperatures ranging from 18 °C to 19 °C and the highest mean temperatures occurring in July. Based on these data, the vegetation season in this region extends from April to October (Figure 5).

Precipitation data showed that the driest period occurred from March to June, with particularly low rainfall in March and April, including some periods with no precipitation. In contrast, the period from July to October was the most humid, with peak precipitation in July and August. During these months, monthly totals often exceeded 150 mm.

The observed meteorological patterns revealed that June to August were characterized by the highest VPD when its values reached up to 6 hPa, with maximum values approaching 8 hPa—particularly in June (Figure 5).

The meteorological data highlighted extreme years relevant to Scots pine ecophysiological responses. The warmer winter of 2020 coincided with one of the coldest vegetation periods, the lowest precipitation amounts, low relative humidity, and the highest VPD.

Conversely, the coldest winter occurred in 2021, accompanied by the hottest vegetation period.

3.2. Mean Stem Increment of Monitored Scots Pine Trees

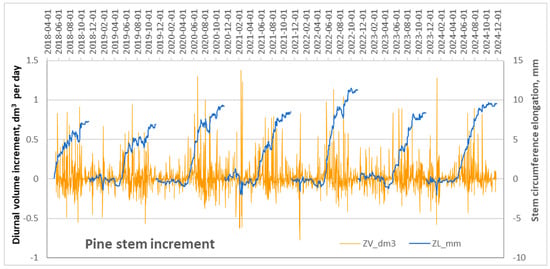

High-resolution measurements of seasonal changes in pine stem circumference were obtained using electronic DRL dendrometers, generating mean datasets at a diurnal scale. These measurements captured not only cumulative stem increment but also short-term fluctuations in stem size caused by diurnal shrinkage and swelling driven by changes in stem water status [32] (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Changes in mean values of monitored pine stem circumferences on a diurnal scale over the 2018–2024 period.

The highest mean values of stem-volume increment were observed in 2024, while the lowest occurred in 2018 and 2019 (Figure 6). Analysis of the mean diurnal stem-volume increment revealed that both maximum and minimum (negative) values were most frequently recorded during the dormant period, reflecting stem swelling and shrinking processes. During the vegetation period, the daily increment typically fluctuated around 500 mm3 per day, with exceptional cases approaching 1 dm3 per day.

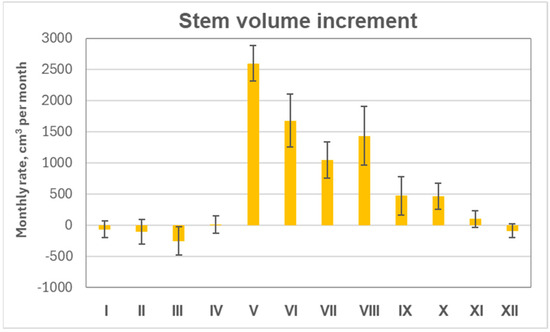

Monthly mean data indicated that the growth season extended from mid-May to the end of September (Figure 7). The largest stem-volume increase occurred in May, resulting from a combination of swelling due to elevated humidity and active growth at the onset of the vegetation period. A slightly lower increment was recorded in June, despite the occurrence of drought and heatwaves typical for this month. The observed monthly increment in October can be attributed to stem swelling associated with precipitation events. From November to April, only stem swelling and shrinking were observed, reflecting fluctuations in tree water balance during the dormant season.

Figure 7.

Mean monthly changes in stem volume of monitored pines based on mean values from the four subplots with their standard errors over the 2018–2024 period (N = 28).

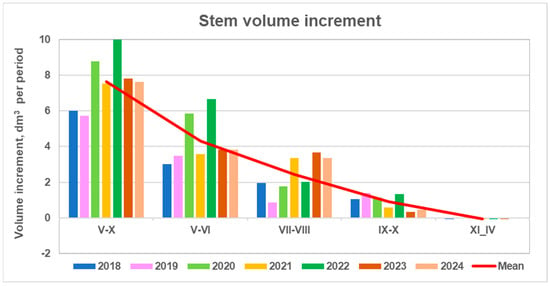

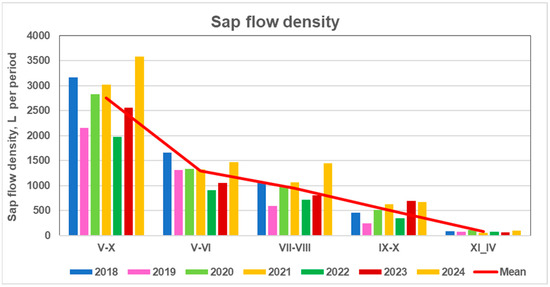

The monthly pattern of stems ZV reveals three distinct growth periods: May–June (V–VI), with the maximum increment; July–August (VII–VIII), representing mid-season growth; and September–October (IX–X), marking the end of the growing season (Figure 8). The dormant period lasts from November to April (XI–IV). These periods contributed 55%, 30%, 15%, and 0% to the annual stem volume increment, respectively.

Figure 8.

Variation in mean stem volume increment of the monitored pines across different seasonal periods over the 2018–2024 period and their overall mean value.

Growth patterns differed among periods; increases in total annual increment did not necessarily occur in the rest two periods. Annual increment was most strongly correlated with May–June growth (r = 0.90, p < 0.05), moderately correlated with July–August (r = 0.23, p > 0.05), and minimally correlated with September–October (r = 0.01, p > 0.05). Consequently, high May–June increments drove the maximum annual growth in 2020 and 2022, even though mid-season growth was among the lowest (green columns in Figure 8).

Further analysis indicated that June growth alone was the most representative of overall stems increase across multiple time frames, including the annual total. The strongest correlation was observed for the combined May–June period (r = 0.877), with slightly lower but still strong correlations for the January–December and May–October periods (r ≈ 0.800) (Table 2). This demonstrates that variation in June increment alone explained over 65% of the variation in annual pine stems growth, despite the maximum absolute increase occurring in May. Therefore, identifying the key factors controlling June stem growth was the exceptional focus of this study.

Table 2.

Relationships between monthly stem volume increment and stem volume increment across different periods in monitored pine trees, based on mean values from the four subplots.

3.3. Mean Transpiration Density of Monitored Pine Trees

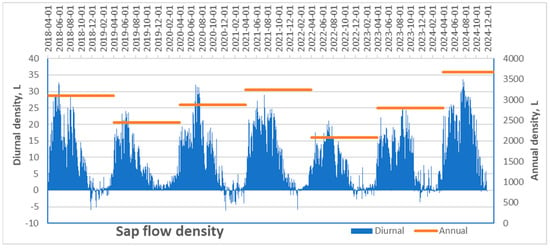

The highest transpiration rate of pine trees growing under extremely dry and nutrient-poor soil conditions was recorded in 2024, significantly exceeding values from previous years (Figure 9). In that year, the maximum daily transpiration rate approached 35,000 mm3 per day, with a total annual volume of approximately 3840 L. In contrast, the years 2019 and—especially—2022 were marked by exceptionally low transpiration levels, with daily rates reaching only 25,000 mm3 and 20,000 mm3 and annual totals of 2290 and 2100 L, respectively.

Figure 9.

Mean diurnal sap flow density rates of monitored Scots pine trees and their mean annual values over the 2018–2024 period.

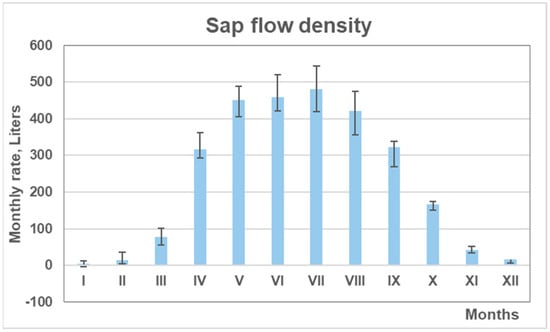

Seasonal variation in pine transpiration showed that the highest rates occurred between April (IV) and September (IX), with peak monthly values recorded from May (V) to August (VIII) (Figure 10). During this period, transpiration rates averaged around 450 L per month. The data indicate that ecophysiological activity at the study site typically begins in early March (III) and continues until mid-November (XI).

Figure 10.

Mean monthly sap flow density of monitored pines based on mean values from the four subplots, with standard errors, over the 2018–2024 period.

The maximum transpiration rate in 2024 occurred throughout the entire year, with particularly high values between May to October. No negative mean monthly transpiration rates were observed in any of the studied pine trees. Sap flow intensity during the mid-season period contributed most strongly to annual sap flow density (r = 0.94, p < 0.002) (Table 3). Unlike the pattern of stem increment, sap flow during the early and late growing season was also significant (IV: r = 0.65 and XI: r = 0.75 when p < 0.05). These results indicate that differently from stem volume increment the highest sap flow intensity across all three parts of the season determined the maximum annual sap flow density (yellow columns in Figure 11). Sap flow density during these periods accounted for 46%, 33%, 18%, and 3% of the annual total, density, respectively.

Table 3.

Relationships Between Monthly Transpiration Rates and Tree Transpiration Across Different Periods.

Figure 11.

Mean transpiration rates of monitored pine trees during different periods from 2018 to 2024, and their overall mean values over the entire study period.

3.4. Mean Water-Use Efficiency of Monitored Pine Trees

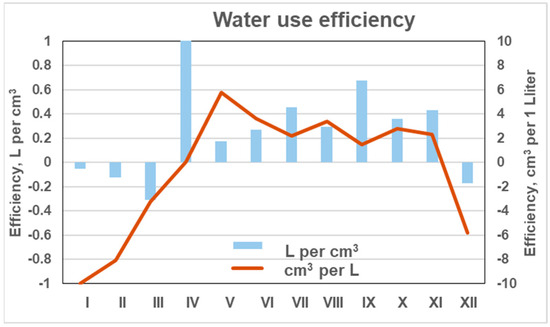

WUE represents a crucial link between the carbon and water cycles and serves as a key indicator of how effectively plants convert water into biomass under specific environmental conditions [33,34,35]. Because trees absorb CO2 through stomata while simultaneously losing water via transpiration, WUE is an essential metric for assessing growth potential under climate stress [36]. Consequently, WUE has become a widely used measure of the adaptive capacity of trees to withstand recent environmental changes. In this study, WUE was quantified in two complementary ways: (i) as the ratio of sap flow (mm or g) to annual stem volume increment (cm3), and (ii) inversely, as the ratio of annual stem volume increment (cm3) to sap flow density (mm or g) in pine stems.

Variations in WUE across different periods revealed distinct seasonal dynamics. The highest values, expressed as cm3 per liter, were observed at the beginning of the vegetation period (May–June), averaging about 5 cm3 L−1 (Figure 12). Slightly lower WUE values were recorded during the middle of the vegetation period (July–August), averaging 2.8 cm3 L−1. Toward the end of the growing season, WUE again increased, exceeding 4 cm3 L−1. However, this late-season increase was largely associated with stem swelling caused by higher precipitation rather than true biomass growth, particularly in November. This phase was followed by a period of stem shrinkage that persisted until the onset of the next growing season in May, during which WUE values even reached negative levels.

Figure 12.

Mean monthly water-use efficiency of monitored pine trees, expressed as cm3 per L and L per cm3, over the 2018–2024 period.

Variations in WUE expressed as liters per cm3 of stem volume revealed similar patterns. During the vegetation period, trees used approximately 300 mL of water to produce 1 cm3 of timber. Elevated values of this index were observed at the beginning of the vegetation period in April, when growth had not yet commenced, indicating an excess water supply relative to increment.

In general, the results indicate that stem volume increment in Scots pine occurred primarily from May to September and partly into October (Figure 12). These patterns clearly demonstrate the duration and timing of the growing season for pine trees in the coastal region of Lithuania.

3.5. Effect of Meteorology on Variation in Considered Response Parameters

Our earlier studies revealed that meteorological variables—including mean, maximum, and minimum air temperatures, solar radiation, relative humidity (particularly minimum values), precipitation, and integrated VPD—most accurately reflect changes in transpiration rate and stem increment in Scots pine trees [19,24,25,32]. To assess the influence of these meteorological parameters on pine growth, transpiration, and WUE, three key periods were analyzed:

- The full vegetation period (May to September).

- The peak ecophysiological activity period (May–June).

- The dormant period (November to March).

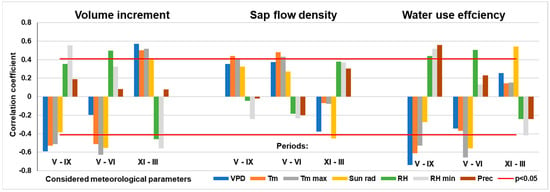

The data showed that air temperature (mean and max. values) and solar radiation significantly reduced stem volume increment (p < 0.05), while relative humidity and precipitation tended to increase it, though their effects were not statistically significant (p > 0.05) (Figure 13). Only rises in minimum relative humidity values had a significant positive effect on annual stem volume growth.

Figure 13.

Relationships between considered meteorological parameters over the different periods and annual values of the main variables of pine tree response: volume increment, sap flow density, and water use efficiency. There: VPD—vapor pressure deficit; Tm—mean temperature; Tm max—mean daily maximal temperature; Sun rad—solar radiation; RH—relative humidity; RH min—mean daily minimal relative humidity; Prec—precipitation amount. Note: correlation is significant p < 0.05 when r > 0.4 (N = 28).

These relationships remained largely unchanged during the intensive growth period (May–June), except for maximum air temperature, which had the strongest inhibitory effect on annual increment during this period.

Interestingly, during the dormant season, the relationships reversed. Meteorological factors which over the vegetation period inhibited pine volume annual increment, during dormant period stimulated it and vice versa, which stimulated—inhibited. The only exception was precipitation during the dormant season, which had no significant effect. All other meteorological variables during dormancy were significantly related to growth, explaining up to 25% of the variation in annual stem increment.

The influence of the selected meteorological parameters on sap flow density variation was slightly less significant than their effect on stem volume increment (Figure 13). Among the variables considered, only air temperature (mean, maximum, and minimum) and solar radiation were found to stimulate water losses due to transpiration intensity, with only minimum and maximum temperatures reaching statistical significance. During the peak growing period, this pattern remained consistent with that observed for stem increment. However, during the dormant season, these relationships reversed: solar radiation had a lagged inhibitory effect on transpiration, while relative humidity had a significant lagged stimulatory effect, explaining up to 20% of the variation in annual sap flow density.

The effect of meteorological parameters on pine WUE (L per cm3) was the strongest among all the relationships analyzed, closely mirroring their influence on stem increment and explaining up to 30% of the variation in WUE (Figure 13).

VPD was identified as one of the main environmental drivers of tree transpiration. It exhibited a non-linear relationship with sap flow density, the nature of which depended on interactions with other meteorological variables that varied substantially throughout the season [19]. This may explain why VPD had the highest explanatory power for both the annual stem volume increment during the vegetation period and WUE, accounting for up to 50% of the variation in the latter.

3.6. A Linear Mixed-Effects Models for Annual Stem Volume Increment, Sap Flow and WUE

The linear mixed-effects models at tree level for annual pine stem increment were fitted using restricted maximum likelihood (REML) to assess the effects of key predictors, including tree diameter, mean temperature during different period and hydrotermic coefficient (HTC) in June. Random variation among subplots (Site_N) and among individual trees within subplots (Tree_N) was accounted for. To evaluate the significance of potential interannual effects, Year was included as a third random factor. The model formula for annual pine stem volume increment over the growing season (ZVv–X) was:

ZV(V–X) ~ D+ Tm(I–III) − Tm(IV–V)+ Tm(VII–VIII) + HTK(VI) + (1|Tree_N) + (1|Site_N) + (1|Year),

Obtained statistics indicated that the model for annual pine stem volume increment (ZVV–X) was well-defined, non-singular, and provided stable variance estimates. Tree diameter and seasonal temperature variables, together with HTC of June, explained a substantial proportion of the variability in annual volume increment (Table 4). Tree diameter had a significant positive effect on growth (p = 0.001), indicating that thicker trees accumulate more stem volume annually. Winter–early spring temperatures (TmI–III) and late summer temperatures (TmVII–VIII) positively influenced growth, whereas warmer late-spring temperatures (TmIV–V) reduced volume increment (all p < 0.01). The hydrothermal coefficient, defined as the ratio between June precipitation and mean temperature, was also a strong positive predictor (p < 0.001). Increases in precipitation and decreases in temperature, resulting in higher HTC values, stimulated tree growth and enhanced annual stem volume increment. This parameter very well indicates the significance of heat wave and drought, which are typical of this month (Figure 4).

Table 4.

Summary of linear mixed-effects models for Scots pine physiological responses.

A linear mixed-effects model was fitted to describe sap flow density during the May–October period (SFv–x, mL) as a function of tree diameter (D), late-winter temperature (TmI–III), early-summer temperature (TmV–VII), and the corresponding mean relative humidity (Table 3). Random intercepts for tree (Tree_N), site (Site_N), and year (Year) were included to account for the hierarchical data structure and repeated measurements.

SF(V–X) ~ D + Tm(I–III) + Tm(V–VII) − RH(I–III) − RH(V–VII) + (1|Tree_N) + (1|Site_N) + (1|Year),

Analysis of the fixed effects showed that temperature in late winter (TmI–III) and early summer (TmV–VII) had strong positive effects on sap flow stimulated it density, while relative humidity in both considered periods (RHI–III and RHV–VII) had significant negative effects (all p < 0.01), inhibited it. Temperature during May–July (TmV–VII) had the largest standardized effect. These results demonstrate that sap flow is strongly controlled by temperature-driven evaporative demand, amplified under low humidity conditions. Larger tree diameter resulted in increased sap flow density.

The linear mixed-effects model evaluated water-use efficiency (WUE V–X) as a function of the selected climatic and structural predictors, with site number (Site_N), tree identity (Tree_N), and “Year” included as random intercepts.

There:

- Tm(I–III)—mean temperature during January–March, represents the mean temperature during January–March, influencing overwinter recovery, cold dehardening, and the onset of spring physiological activity.

- Tm(VI–IX)—mean temperature during June-September, reflects the pronounced decline in WUE under elevated summer temperatures, typically associated with heat and drought conditions.

- Pr(VI)—precipitation amount in June, determining early-summer water availability in sandy soils and drought effect.

The WUE model showed a good overall fit. Fixed effects indicated that WUE was strongly and negatively associated with late-summer temperature (TmVI–IX) (Table 4). Precipitation in June (PrVI) had a positive effect (p = 0.006), suggesting increased water-use efficiency under higher water availability and significance of drought in this month. The effect of late winter temperature (Tm_I–III) was close to significance (p = 0.13), indicating that warm winters do not substantially affect annual WUE. However, warmer winters could increase soil moisture by reducing surface water runoff, which in turn enhances tree physiological activity, resulting in higher stem-volume increment and sap-flow density at the beginning of vegetation. The interaction of these two processes may partially offset each other in WUE, so that WUE alone does not fully reflect tree condition. Tree diameter (D) was also close to significant, retaining a positive effect and indicating that thicker trees not only achieve higher volume increment and sap-flow density but also higher WUE.

3.7. Random Effect of Considered Variables in a Linear Mixed-Effects Models for Annual Stem Volume Increment, Sap Flow Density and WUE and Their Differences

Random effects in the linear mixed-effects model for ZV indicated substantial variability among individual trees (σ = 544.3) and among sites (σ = 540.6), highlighting meaningful differences in growth potential across trees and locations (Table 4). In contrast, the year random effect was estimated at zero, resulting in a singular fit and indicating that interannual variability in volume increment was negligible once tree- and site-level differences and climatic predictors were accounted for. Residual variance remained moderate (σ = 444.1), consistent with expected within-tree growth heterogeneity.

Model diagnostics (AIC = 1101.2; BIC = 1123.7; logLik = –540.6) indicate a stable and well-fitted model. These results demonstrate that interannual variability is negligible relative to hierarchical variation among trees and sites. Inclusion of the year random effect does not improve model fit, increases AIC, and is therefore omitted to maintain a simpler, more parsimonious model.

The model demonstrated excellent fit: fixed effects alone explained 76% of the variation in annual volume increment, and including random effects for trees and sites numbers increased the explained variance to 94% (Table 5). This indicates that the model effectively captures both hierarchical and repeated-measurement structure in the data, making it well-suited for assessing adaptive capacity of Scots pine trees to meteorological extremes in highly oligotrophic soil Forest.

Table 5.

Main statistics of linear mixed-effects models and their random effects.

Random effects in the linear mixed-effects model for SF indicated substantial variation among individual trees (σ = 147.7) and among sites (σ = 143.2) (Table 5). In contrast, the year random effect, as in the ZV model, had a variance estimate of zero, indicating no detectable interannual variation after accounting for climate and tree diameter, which was confirmed by a singular fit warning. Residual variance remained the largest component (σ = 298.8), reflecting biologically expected within-tree variability.

Model diagnostics (AIC = 1030.2; BIC = 1052.7; logLik = −505.1) indicate a well-defined and parsimonious model (Table 4). Fixed effects explained 69% of the variance (R2m = 0.695), while the full model including random effects explained 79% (R2c = 0.793), demonstrating strong contributions from both the climatic predictors and the grouping structure. Consequently, the year random effect was excluded from the final model, as it did not contribute additional interannual variability beyond the seasonal temperature predictors.

Noticeable that variance partitioning differed markedly between the model for ZV and the model for SF, highlighting distinct sources of variability for structural growth versus physiological water use. In the ZV model, the variances associated with tree identity and site exceeded the residual variance, indicating that most unexplained variation in volume increment originates from persistent differences among individual trees and site-level conditions rather than from short-term noise.

In contrast, the SF model exhibited the opposite pattern: residual variance exceeded the random-effect variances of trees and sites. This indicates that sap flow is more strongly influenced by short-term, within-tree fluctuations and measurement-level variability than by stable tree- or site-level characteristics. Physiological water transport responds rapidly to short-term meteorological changes (humidity, temperature, vapor pressure deficit), introducing high day-to-day variability not fully captured by the random factors. Consequently, much of the remaining variance is reflected in the residual term, while tree- and site-level differences contribute less to total variation.

Taken together, these contrasting variance patterns indicate that structural growth (ZV) is governed predominantly by stable, long-term differences among trees and sites, whereas SF is driven mainly by rapid physiological responses to short-term environmental fluctuations, resulting in proportionally higher residual variance.

Random effects in the WUE model indicated that variation among individual trees (Tree_N) and among sites (Site_N) was effectively zero (σ = 0.0). In contrast, the year random effect exhibited a small but non-zero variance (σ = 0.182), reflecting modest interannual variability in WUE not explained by the fixed predictors.

Residual variance remained the largest component (σ = 0.416), representing within-tree variability and short-term fluctuations in water-use efficiency. These results indicate that, unlike structural growth (ZV), which exhibits substantial tree- and site-level variability, WUE is primarily determined by the modeled climatic drivers, with minimal contribution from hierarchical tree- or site-level effects. The singular fit for tree and site confirms that their random effects do not provide additional explanatory power beyond the fixed predictors. Tree- and site-level differences that strongly influence ZV or SF largely cancel out when expressed as efficiency, indicating highly uniform WUE responses across individuals—likely due to nutrient limitations homogenizing physiological strategies [37,38]. In dry years, low June precipitation constrained both sap flow and WUE, demonstrating that mid-season moisture is a key determinant of the carbon–water balance.

The model showed good overall fit (AIC = 101.2; BIC = 121.5; logLik = −41.6). The marginal R2 was 0.85, indicating that fixed effects explained most of the variation in WUE (Table 4). The conditional R2 was 0.88, showing that random effects contributed only marginally. The model exhibited a singular fit, with zero variance for both Tree_N and Site_N, indicating that tree-level and site-level differences did not contribute to WUE variation in this dataset. The random effect of Year retained a small variance component (σ = 0.182), suggesting modest interannual variability. Overall, WUE appears to be a strongly climate-driven, integrative metric linking physiology, growth, and environmental stress, particularly in nutrient-poor soils where trees cannot easily compensate for water or heat stress through growth. It provides an early warning of limitations in carbon–water balance and allows assessment of adaptive capacity under variable meteorological conditions, even before visible declines in stem growth or canopy condition occur.

4. Discussion

The Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) in this study was located near the center of its natural distribution range in Lithuania [17]. Its exceptionally wide geographic scope and ability to modify morphometric traits reflect its strong adaptive capacity and tolerance to diverse environmental stressors. However, some authors predict that, like Norway spruce, Scots pine may be particularly sensitive to climate change and thus among the most vulnerable tree species in the region [39,40,41]. Due to their deep root systems and high sensitivity to both favorable and unfavorable environmental factors, pine trees have demonstrated high tolerance to recent meteorological conditions—exhibited by restricted transpiration rate, consistently high annual stem volume increment and WUE [19]. These adaptations allow Scots pine to balance water conservation with carbon assimilation, supporting their survival in an increasingly unpredictable climate [42].

Recent research highlights that WUE is a crucial adaptive mechanism for Scots pine growing in dry, nutrient-poor habitats. Trees respond to drought stress through a combination of structural and physiological adjustments aimed at conserving water while maintaining carbon assimilation. These adaptations commonly include a reduction in leaf area, which decreases the transpiration surface, and regulation of stomatal conductance to control water loss without severely limiting photosynthesis [43,44]. In the present study, we did not observe significant changes in tree crown defoliation following warm winter conditions combined with drought and a heatwave in June. This suggests that photosynthetic activity was not substantially constrained and did not negatively affect annual stem increment. Consequently, crown defoliation was not included as a predict variable in the multiple regression analysis. Instead, tree diameter was included in all models, reflecting its direct relationships with the response variables considered: ZV and SF. It should be noted that with increasing tree size, water-use efficiency (WUE) also increases, which helps explain why larger trees are generally more productive and better adapted to survive environmental stress.

Under dry soil conditions, understanding the dynamics of WUE in Scots pine is more critical than ever. Drought and heatwaves, which significantly reduce soil moisture, negatively affect transpiration rates, growth, and WUE [4,45,46]. The cumulative effects of drought stress can impair trees’ recovery capacity, especially in nutrient-poor soils where resources for repair and growth are limited. Moreover, ongoing climate change poses additional threats to Scots pine populations by altering habitat conditions, exacerbating water scarcity, and increasing the frequency and severity of drought events [47]. However, studies by Liu et al. (2021) found that co-occurring pine species in the Great Basin exhibited improved WUE following periods of drought relief, indicating a degree of physiological adaptability [48]. This suggests that some pine species can adjust their WUE strategies to cope with climate variability—a key trait for resilience under increasingly arid conditions. Our data supports this finding. During the study period, significant reduction in stem volume increment—the main response variable related to WUE variability, was not detected. This indicates that Scots pine may maintain growth performance and adjust WUE even under challenging climatic conditions.

Misi and Náfrádi [49] similarly noted that although rising winter temperatures can enhance early-season growth, this effect is often diminished by reduced summer moisture—an increasingly common consequence of climate change. Our results support this pattern: warm winters had a significant positive effect on stem increment at the beginning of the growing season, but this effect declined in mid-season and was especially weak toward the end of vegetation. Moisture deficits combined with heat waves—particularly in June—reduced stem increment and increased sap flow density, which in turn raised the water content per unit volume of wood.

Kellomäki et al. [50] reported that while moderate climate warming may enhance growth and survival in northern populations of Scots pine, it can reduce growth in southern regions where drought occurs more frequently. In such areas, moisture availability becomes a critical determinant of growth, with increased soil moisture enhancing tree performance and reducing competition among individuals [51]. Therefore, in the presented study the key factor for tree growth and transpiration density apparent middle vegetation meteorology mainly of June, which characterized in Curonian Spit by increase in air temperature (p < 0.05) and decrease in precipitation amount (p < 0.10) in May-June during the last 15-year long period (Figure 4).

The obtained data revealed that, across all indicators, summer temperature (TmVI–IX) was the dominant negative predictor, highlighting the vulnerability of Scots pine to warm-season heat stress under severely nutrient-poor conditions. Precipitation effects, were consistently positive. Summer precipitation (Pr_VI–IX) enhanced annual ZV and SF, while June precipitation (Pr_VI) exerted the strongest positive effect on WUE, indicating a temporally narrow but physiologically critical moisture window for regulating intrinsic water-use efficiency. This relationship also reflects the exceptionally negative impact of drought on all considered response variables of Scots pine. These findings point to emerging threats to Scots pine sustainability, as the recurrence of mid-summer heat waves and droughts in May–June demonstrates tendency towards increasing.

The effects of warmer winters on pine resilience—particularly their capacity to withstand mid-summer drought and heatwaves—directly address the central aims of this study. Based on the obtained results, stem-volume increments in May and especially in June are the strongest predictors of annual increment (Table 3). Together, they explain more than 70% of the variation in annual growth and are critical for pine productivity in the northeastern hemi-boreal forest region [52,53], as well as for Scots pine crown defoliation dynamics [54]. Therefore, we selected them to evaluate the combined effects of warm winters and mid-summer heat and drought on pine increment during these key months.

Late-winter temperatures positively influenced ZV SF, demonstrating that pre-season thermal conditions are crucial for setting growth potential and hydraulic capacity for the season. Warmer late winters facilitate earlier hydraulic recovery, reducing xylem embolism and improving water transport [55,56]; earlier cambial reactivation, extending the period available for stem-volume accumulation [57,58]; improved carbohydrate mobilization, supporting early-season growth initiation [59]; and earlier soil thawing, enhancing root water uptake [60]. The benefits of warm late winters propagate throughout the growing season, but they are strongly modulated by mid-season precipitation. Even following a warm winter, low rainfall in June limits growth and reduces sap flow, highlighting the importance of both thermal and hydric conditions for overall Scots pine performance.

Radial growth, measured as annual stem ZV, is a widely used indicator of tree performance, integrating the cumulative effects of seasonal environmental conditions [61]. Earlywood formation at the start of the growing season is particularly sensitive to water availability and temperature during cell enlargement and division, providing a physiological window into hydraulic function [62,63]. Additionally, VPD provides a direct link between water availability, stomatal regulation, and biomass production [40,64,65]. Integrating these structural and physiological indicators allowed a comprehensive assessment of how Scots pine balances carbon and water under climatic and edaphic constraints.

After eliminating the effects of tree thickness and random predictors, multiple regression analysis based on the averaged pine datasets (N = 7) revealed that precipitation amount was the primary predictor of stem-volume increment in June. No additional predictor increased the explanatory power of the model, which exceeded 88%. In contrast, mean temperature during May–June was the only significant predictor, explaining up to 68% of the variation in stem-volume increment over this two-month period. When VPD variables were included in the multiple regression model for ZVV–VI, winter conditions together with mid-season climate emerged as the strongest predictors, jointly explaining more than 87% of the variation in pine increment during May–June.

ZVV–VI = 7722.6 + 2597.4 × VPDI–III − 1000.5 × VPDVI,

There: Adjusted R2= 0.874; F(2,4) = 21.8; p < 0.007; Std.Err. of est.: 488.3.

The obtained data revealed that elevated VPD during warm winters stimulates stem-volume increment at the beginning of the vegetation period. In contrast, increased VPD resulting from heat waves and reduced humidity or precipitation negatively affected all physiological processes in Scots pine. This supports previous findings that high summer temperatures reduce radial growth by increasing VPD, lowering stomatal conductance, and accelerating soil moisture depletion [61,66]. These results are also consistent with studies showing that Scots pine growth at dry or nutrient-poor sites is strongly constrained by mid-season moisture deficits [15,67], which in our case is reflected by precipitation in May and, especially, June.

Current knowledge indicates that under drought stress, Scots pine reduces stomatal conductance and increases osmotic adjustment, helping to maintain internal water pressure and reduce water loss while still permitting CO2 uptake for photosynthesis [68]. This aligns with our findings, as June exhibited the highest WUE (4 cm3 per liter of water) and the highest stem-volume increment (17 dm3 per month), particularly when stem swelling effects were excluded—most notably following warm winter periods. However, these results do not fully account for potential lagged effects, as factors such as carbohydrate depletion, xylem embolism risk, or the cumulative impacts of multi-year drought sequences were not investigated. Potential negative interactions between these two growth-limiting factors could not be assessed, as the meteorological conditions at the monitored site did not allow their detection. During the study period, the warmest winter was followed by one of the coldest vegetation seasons, with no pronounced drought events. Nevertheless, the positive effects of winter meteorological conditions, expressed via VPD during this period, on stem-volume increment should not be overlooked when analyzing the impact of warm winters on Scots pine growth and WUE.

Also the present study does not address the demographic consequences of high WUE under stress, such as reproductive output or seed production. During the year of investigation no exclusively seed years were identified. Additionally, it is important to recognize that increased WUE can sometimes mask underlying physiological stress. The possible effects of competition or genetic diversity in Scots pine populations, both of which can significantly affect the physiology of gas exchange in response to varying water availability, have also not been investigated, whereas genetic predisposition and site-specific environmental factors shape a tree’s drought tolerance [69]. These aspects are important directions for our future research.

Finally, the results obtained suggest that forecasting future changes in Scots pine resilience will depend on the trajectories of several key climatic variables. Over the past 15 years, significant increases in air temperature during January, February, June, and October (p < 0.05), along with decreases in precipitation in May, June, September, and December (p < 0.1), have been observed as important trends. Despite these climatic shifts, which may pose new threats to Scots pine forest sustainability in the future, the absence of a clearly defined threshold beyond which Scots pine cannot survive indicates that the species remains highly suitable for silvicultural use in hemi-boreal forests.

Notwithstanding this, existing studies highlight the complex relationship between warmer winter temperatures and WUE, which could significantly affect the growth of Scots pine [70]. Variations in growth responses, physiological adaptations, and competitive dynamics underscore the need for more comprehensive research in this area. This study provides valuable insights into WUE of Scots pine in nutrient-poor and dry habitats, yet several promising avenues remain for future investigation.

A key direction is the long-term monitoring of WUE under varying drought intensities and frequencies. Such research would help identify critical thresholds beyond which Scots pine lose their capacity to sustain growth and physiological function, thereby improving predictions of forest resilience and vulnerability under increasing aridity. Another important area involves examining the interaction between nutrient availability and WUE, particularly in nutrient-poor sandy soils where limited resources may exacerbate drought stress. Understanding how nutrient deficiencies influence WUE and growth could reveal key trade-offs in resource allocation and support the development of effective forest management strategies aimed at enhancing tree health and resilience under challenging environmental conditions.

Effective forest management should account for these factors to mitigate the adverse effects of climate change and promote ecosystem sustainability. On nutrient-poor sandy soils, Scots pine populations may approach thresholds beyond which growth collapse or regeneration failure occurs [71]. Management strategies may include promoting mixed stands to reduce competition for water. Thinning practices—where suppressed, smaller trees are removed to alleviate competitive stress—support more resilient growth of larger trees under future climatic conditions [72,73]. Accordingly, adaptive, close-to-natural silvicultural treatments that maintain continuous forest cover with Scots pine as the dominant canopy species can enhance the long-term sustainability of coniferous forests, increase their resilience to emerging climate-related threats, and provide guidance for future forest research and management planning.

5. Conclusions

Climate change has driven a pronounced warming trend in northeastern Europe, particularly along the Lithuanian coast in Curonian Spit National Park. Over the past 15 years, mean air temperature has increased by more than 1.5 °C.

The linear mixed-effects model showed that the annual ZV was strongly influenced by both tree size and seasonal temperature variability. Higher temperatures in late winter and mid-summer significantly increased the volume increment. In contrast, the April–May temperature (Tm_IV–V) had a negative effect, while the hydrothermal coefficient in June (HTK_VI) had a positive effect on growth intensity. These relationships highlight the sensitivity of Scots pine stands in hemi-boreal forests, which can substantially limit tree growth and thus affect long-term stand sustainability.

SF density was primarily controlled by climatic factors, with tree size playing only a minor role. The mean temperature in late winter and mid-summer stimulated sap-flow density, whereas relative humidity during these same periods had significant negative effects, reducing sap-flow activity.

The random effects for Tree_No and Site_No in the ZV model indicated that most of the unexplained variability was associated with stable differences among trees and sites. The random effect for “Year” was zero, indicating no detectable interannual variability in either response variable once climatic predictors were included.

Climatic factors were the dominant drivers of variation in WUE. Higher temperatures during the dormant season and moderate precipitation reduced transpiration, thereby decreasing the amount of water required to produce 1 cm3 of timber and increasing WUE. Conversely, higher temperatures during the growing season enhanced transpiration and water loss, increasing water demand per unit of timber and reducing WUE—by up to 3 cm3 per L. Tree diameter indicated that larger trees require less water per unit of growth, reflecting higher productivity, although this effect was only close to statistical significance.

The strong positive effect of June precipitation highlights the sensitivity of WUE to short-term moisture supply during a critical period of cell enlargement, xylem differentiation, and early canopy demand. This meteorological dependence points to emerging threats for Scots pine in hemi-boreal forests, as drought and heat waves in June are becoming increasingly frequent.

Random variances for both Site and Tree No were estimated as zero (singular fit), indicating that persistent individual- or site-level differences did not measurably contribute to variation in WUE. In contrast, the random effect of Year remained significant, reflecting the influence of interannual climatic variability on the balance between carbon gain and water loss, rather than local environmental heterogeneity.

Despite exceptionally rapid climatic changes, Scots pine forests have maintained substantial stem-volume increments, high water-use efficiency, and a remarkable adaptive capacity to tolerate shifting environmental conditions. No critical threshold was detected beyond which Scots pine experiences irreversible ecophysiological damage. However, it should be noted that no extreme meteorological events—such as severe drought during the vegetation period following an exceptionally warm winter—occurred during the study period. Therefore, the future sustainability of Scots pine forests will depend on the character, intensity, and balance of key meteorological parameters that collectively shape forest condition and growth. These findings highlight important directions for future research and provide a basis for developing adaptive management strategies for pine forests.

Author Contributions

A.A. and D.S. contributed equally to this manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research paper has received funding from European Union Horizon Europe research and innovation programme (HORIZON), call Teaming for Excellence (HORIZON-WIDERA-2022-ACCESS-01-two-stage)—Creation of the centre of excellence in smart forestry “Forest 4.0”, No. 101059985, and co-funded by the European Union under the project “FOREST 4.0—Centre of Excellence for the development of a sustainable forest bioeconomy”, No. 10-042-P-0002.

Data Availability Statement

The part of the data presented in this study are openly available in [25] Baumgarten et al., 2019; https://doi.org/10.2480/agrmet.D-18-00008 and [19] Augustaitis and Pivoras, 2024; https://doi.org/10.3390/f15071158. The datasets presented in this article are not readily available due to an ongoing study of the European Union under the project “FOREST 4.0”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- IPCC. Summary for policymakers. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S.L., P’ean, C., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M.I., Matthews, J.B.R., Berger, S., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021; pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, C.D.; Breshears, D.D.; McDowell, N.G. On underestimation of global vulnerability to tree mortality and forest die-off from hotter drought in the Anthropocene. Ecosphere 2015, 6, art129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.D.; Macalady, A.K.; Chenchouni, H.; Bachelet, D.; McDowell, N.; Vennetier, M.; Kitzberger, T.; Rigling, A.; Breshears, D.D.; Hogg, E.H.; et al. A global overview of drought and heat-induced tree mortality reveals emerging climate change risks for forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2010, 259, 660–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazol, A.; Camarero, J.J. Compound climate events increase tree drought mortality across European forests. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 816, 151604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, W.M.; Williams, A.P.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Adams, H.D.; Klein, T.; López, R.; Allen, C.D. Global field observations of tree die-off reveal hotter-drought fingerprint for Earth’s forests. Nat. Comm. 2022, 13, 1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bréda, N.; Huc, R.; Granier, A.; Dreyer, E. Temperate forest trees and stands under severe drought: A review of ecophysiological responses, adaptation processes and long-term consequences. Ann. For. Sci. 2006, 63, 625–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Qiao, L.; Xia, H. The impact of drought time scales and characteristics on gross primary productivity in China from 2001 to 2020. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2024, 27, 651–669. [Google Scholar]

- Babst, F.; Bouriaud, O.; Poulter, B.; Trouet, V.; Girardin, M.P.; Frank, D.C. Twentieth-century redistribution in climatic drivers of global tree growth. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaat4313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossiord, C.; Buckley, T.N.; Cernusak, L.A.; Novick, K.A.; Poulter, B.; Siegwolf, R.T.W.; Sperry, J.S.; Mcdowell, N.G. Plant responses to rising vapor pressure deficit. New Phytol. 2020, 226, 1550–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSoto, L.; Cailleret, M.; Sterck, F.; Jansen, S.; Kramer, K.; Robert, E.M.R.; Aakala, T.; Amoroso, M.M.; Bigler, C.; Camarero, J.J.; et al. Low growth resilience to drought is related to future mortality risk in trees. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, A.P.; Allen, C.D.; Macalady, A.K.; Griffin, D.; Woodhouse, C.A.; Meko, D.M.; Swetnam, T.W.; Rauscher, S.A.; Seager, R.; Grissino-Mayer, H.D.; et al. Temperature as a potent driver of regional forest drought stress and tree mortality. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2013, 3, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Markkanen, T.; Aurela, M.; Mammarella, I.; Thum, T.; Tsuruta, A.; Yang, H.; Aalto, T. Response of water use efficiency to summer drought in a boreal Scots pine forest in Finland. Biogeosciences 2017, 14, 4409–4422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, J.E.; Smiljanić, M.; Scharnweber, T.; Buras, A.; Cedro, A.; Cruz-García, R.; Drobyshev, I.; Janecka, K.; Jansons, Ā.; Kaczka, R.; et al. Tree growth influenced by warming winter climate and summer moisture availability in northern temperate forests. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 2505–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Liu, C.; He, H.S.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Xie, Z. Assessing the impact of climate warming on tree species composition and distribution in the forest region of Northeast China. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1430025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eilmann, B.; Rigling, A. Tree-growth analyses to estimate tree species’ drought tolerance. Tree Physiol. 2012, 32, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bose, A.K.; Gessler, A.; Bolte, A.; Bottero, A.; Buras, A.; Cailleret, M.; Camarero, J.J.; Haeni, M.; Hereş, A.; Hevia, A.; et al. Growth and resilience responses of Scots pine to extreme droughts across Europe depend on predrought growth conditions. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 4521–4537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozolinčius, R.; Lekevičius, E.; Stakėnas, V.; Galvonaitė, A.; Samas, A.; Valiukas, D. Lithuanian forests and climate change: Possible effects on tree species composition. Eur. J. For. Res. 2014, 133, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LHMT (Lithuanian Hydrometeoservice), 2024. Available online: https://www.meteo.lt/ (accessed on 5 January 2026).

- Augustaitis, A.; Pivoras, A. Sap flow density of the prevailing tree species in a hemiboreal forest under contrasting meteorological and growing conditions. Forests 2024, 15, 1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Wei, X.; Xu, Z.; Spencer, S.A.; Qiu, M.; Lyu, S.; Liu, W. Impact of heatwave and thinning on tree growth and soil water content in young lodgepole pine forests. For. Ecosyst. 2026, 15, 100398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, S.S.O.; Adams, M.A.; Turner, N.C.; Beverly, C.R.; Ong, C.K.; Khan, A.A.H.; Bleby, T.M. An improved heat pulse method to measure low and reverse rates of sap flow in woody plants. Tree Physiol. 2001, 21, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICT International. Sap Flow Tool, Version 1.4; Analysis and Visualization of Sap Flow Data. User Manual 2016; ICT International: Armidale, Australia, 2016; Available online: https://www.youtube.com/c/ICTinternational (accessed on 5 January 2026).

- Deng, Z.; Vice, H.K.; Gilbert, M.E.; Adams, M.A.; Buckley, T.N. A double—Ratio method to measure fast, slow and reverse sap flows. Tree Physiol. 2021, 41, 2438–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgarten, M.; Weis, W.; Kühn, A.; May, M.; Matyssek, R. Forest transpiration targeted through xylem sap flux assessment versus hydrological modeling. Eur. J. For. Res. 2014, 133, 677–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgarten, M.; Hesse, B.D.; Augustaitienė, I.; Marozas, V.; Mozgeris, G.; Byčenkienė, S.; Mordas, G.; Pivoras, A.; Pivoras, G.; Juonytė, D.; et al. Responses of species-specific sap flux, transpiration and water use efficiency of pine, spruce and birch trees to temporarily moderate dry periods in mixed forests at a dry and wet forest site in the hemi-boreal zone. J. Agric. Meteorol. 2019, 75, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benisiewicz, B.; Pawełczyk, S.; Niccoli, F.; Kabala, J.P.; Battipaglia, G. Drought Impact on Eco-Physiological Responses and Growth Performance of Healthy and Declining Pinus sylvestris L. Trees Growing in a Dry Area of Southern Poland. Forests 2024, 15, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brichta, J.; Šimůnek, V.; Bílek, L.; Vacek, Z.; Gallo, J.; Drozdowski, S.; Bravo-Fernández, J.A.; Mason, B.; Gomez, S.R.; Hájek, V.; et al. Effects of Climate Change on Scots Pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) Growth across Europe: Decrease of Tree-Ring Fluctuation and Amplification of Climate Stress. Forests 2024, 15, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hietz, P.; Dorman, M.; Muller, C.; Wanek, W.; Richter, A. Water relations and photosynthetic water use efficiency as indicators of slow climate change effects on trees in a tropical mountain forest in South Ecuador. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 83, 550–558. [Google Scholar]

- Keenan, T.F.; Hollinger, D.Y.; Bohrer, G.; Dragoni, D.; Munger, J.W.; Schmid, H.P.; Richardson, A.D. Increase in forest water-use efficiency as atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations rise. Nature 2013, 499, 324–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakagawa, S.; Schielzeth, H. A general and simple method for obtaining R2 from generalized linear mixed-effects models. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2013, 4, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 5 January 2026).

- Augustaitis, A. Intra-annual variation of stem circumference of tree species prevailing in hemi-boreal forest on hourly scale in relation to meteorology, solar radiation and surface ozone fluxes. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Cao, J.; Yao, C.; Wang, Z.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Tuo, W.; Dong, W.; Tong, X.; Wu, F. Water use efficiency of trees planted on abandoned farmland and influencing factors in a Loess Hilly Area. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 24, 2972–2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cernusak, L.A. Gas exchange and water-use efficiency in plant canopies. Plant Biol. 2020, 22, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Piao, S.; Sun, Y.; Ciais, P.; Cheng, L.; Mao, J.; Poulter, B.; Shi, X.; Zeng, Z.; Wang, Y. Change in terrestrial ecosystem water-use efficiency over the last three decades. Glob. Change Biol. 2015, 21, 2366–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderegg, W.R.L.; Schwalm, C.; Biondi, F.; Camarero, J.J.; Koch, G.; Litvak, M.; Ogle, K.; Shaw, J.D.; Shevliakova, E.; Williams, A.P.; et al. Pervasive drought legacies in forest ecosystems and their implications for carbon cycle models. Science 2015, 349, 528–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brienen, R.J.W.; Gloor, E.; Clerici, S.; Newton, R.; Arppe, L.; Boom, A.; Bottrell, S.; Callaghan, M.; Heaton, T.; Helama, S.; et al. Tree height strongly affects estimates of water-use efficiency responses to climate and CO2 using isotopes. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathias, J.M.; Thomas, R.Q. Global tree intrinsic water use efficiency is enhanced by increased atmospheric CO2 and modulated by climate and plant functional types. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2014286118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oogathoo, S.; Houle, D.; Duchesne, L.; Kneeshaw, D. Vapor pressure deficit and solar radiation are the major drivers of transpiration of balsam fir and black spruce tree species in humid boreal regions, even during a short-term drought. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2020, 291, 108063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanewinkel, M.; Cullmann, D.A.; Schelhaas, M.J.; Nabuurs, G.J.; Zimmermann, N.E. Climate change may cause severe loss in the economic value of European forest land. Nat. Clim. Change 2013, 3, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briceño-Elizondo, E.; Garcia-Gonzalo, J.; Peltola, H.; Matala, J.; Kellomäki, S. Sensitivity of growth of Scots pine, Norway spruce and silver birch to climate change and forest management in boreal conditions. For. Ecol. Manag. 2006, 232, 152–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarin, M.W.K.; Fan, L.L.; Shen, L.; Lai, J.L.; Tayyab, M.; Sarfraz, R.; Chen, L.Y.; Ye, J.; He, T.Y.; Rong, J.D.; et al. Effects of different biochars ammendments on physiochemical properties of soil and root morphological attributes of Fokenia hodginsii. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2019, 17, 11107–11120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamm, O.; Vainio, E.; Nieminen, T. Physiological and structural adaptations of Scots pine to drought stress in nutrient-poor environments. Tree Physiol. 2024, 44, 56–68. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Wang, Y. Leaf morphological changes and stomatal regulation in Scots pine under drought conditions. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2025, 210, 105309. [Google Scholar]

- Galiano, L.; Martínez-Vilalta, J.; Lloret, F. Long-term drought effects on Scots pine growth and mortality in nutrient-poor soils. Glob. Change Biol. 2023, 29, 1234–1247. [Google Scholar]

- Morales, D.; Sánchez, A.; Ruiz, M. Drought stress and recovery in Scots pine: Physiological and growth responses in poor soils. J. Plant Physiol. 2024, 295, 153563. [Google Scholar]

- Gücel, S.; Demirci, S.; Korkmaz, M. Impact of climate change on Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) health in dry and nutrient-poor habitats of Central Anatolia. For. Ecol. Manag. 2025, 502, 119823. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Liu, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Yin, H.; Xie, Y.; Wei, Y. Two terpene synthases in resistant Pinus massoniana contribute to defence against Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Plant Cell Environ. 2021, 44, 257–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misi, D.; Náfrádi, K. Growth response of Scots pine to changing climatic conditions over the last 100 years: A case study from Western Hungary. Trees 2017, 31, 919–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellomäki, S.; Strandman, H.; Heinonen, T.; Asikainen, A.; Venäläinen, A.; Peltola, H. Temporal and Spatial Change in Diameter Growth of Boreal Scots Pine, Norway Spruce, and Birch under Recent-Generation (CMIP5) Global Climate Model Projections for the 21st Century. Forests 2018, 9, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayat, M.; Knoke, T.; Heidari, S.; Hamidi, S.K.; Burkhart, H.; Jaafari, A. Modeling tree growth responses to climate change: A case study in natural deciduous mountain forests. Forests 2022, 13, 1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlin, M.; Hylen, G.; Vergarechea, M.; Bright, R.M.; Eisner, S.; Solberg, S. Climate-growth relationships for Norway spruce and Scots pine remained relatively stable in Norway over the past 60 years despite significant warming trends. For. Ecol. Manag. 2024, 569, 122180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogana, F.N.; Holmstrom, E.; Aldea, J.; Liziniewicz, M. Growth response of Pinus sylvestris L. and Picea abies [L.] H. Karst to climate conditions across a latitudinal gradient in Sweden. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2024, 353, 110062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustaitis, A.; Augustaitienė, I.; Kliučius, A.; Pivoras, G.; Šopauskienė, D.; Girgždienė, R. The seasonal variability of air pollution effects on pine conditions under changing climates. Eur. J. For. Res. 2010, 129, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayr, S.; Schmid, P.; Rosner, S. Winter Embolism and Recovery in the Conifer Shrub Pinus mugo L. Forests 2019, 10, 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charrier, G.; Martin-StPaul, N.; Damesin, C.; Delpierre, N.N.; Hänninen, H.; Ruiz, J.M.T.; Davi, H. Interaction of drought and frost in tree ecophysiology: Rethinking the timing of risks. Ann. For. Sci. 2021, 78, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziaco, E.; Biondi, F.; Rossi, S.; Deslauriers, A. Climatic influences on wood anatomy and tree-ring features of Great Basin conifers at a new mountain observatory. Appl. Plant Sci. 2014, 10, 1400054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, S.; Nakaba, S.; Yamagishi, Y.; Oribe, Y.; Funada, R. Regulation of cambial activity in relation to environmental conditions: Understanding the role of temperature in wood formation of trees. Physiol. Plant. 2013, 147, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, N.; Wang, L.; Li, G.; Dong, C.; Liu, O.; Zhou, G. Seasonal patterns between wood formation and non-structural carbohydrate in two conifers with distinct life-history traits. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2025, 233, 106141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreyling, J. Winter climate change: A critical factor for temperate vegetation performance. Ecology 2010, 91, 1939–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwman, M.; Akhmetzyanov, L.; Mohren, F.; den Ouden, J.; Sass-Klaassen, U.; Copini, P. Tree growth responses to severe droughts for assessment of forest growth potential under future climate. For. Ecol. Manag. 2025, 578, 122423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckes-Shephard, A.H.; Ljungqvist, F.C.; Drew, D.M.; Rathgeber, C.B.K.; Friend, A.D. Wood Formation Modeling—A Research Review and Future Perspectives. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 837648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Luis, M.; Novak, K.; Raventós, J.; Gričar, J.; Prislan, P.; Čufar, K. Cambial activity, wood formation and sapling survival of Pinus halepensis exposed to different irrigation regimes. For. Ecol. Manag. 2011, 262, 1630–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, D.C.; Poulter, B.; Saurer, M.; Esper, J.; Huntingford, C.; Helle, G.; Treydte, K.; Zimmermann, N.E.; Schleser, G.H.; Ahlström, A.; et al. Water-use eciency and transpiration across European forests during the Anthropocene. Nat. Clim. Change 2015, 5, 579–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novick, K.A.; Ficklin, D.L.; Grossiord, C.; Konings, A.G.; Martínez-Vilalta, J.; Sadok, W.; Trugman, A.T.; Williams, A.P.; Wright, A.J.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; et al. The impacts of rising vapour pressure deficit in natural and managed ecosystems. Plant Cell Environ. 2024, 47, 3561–3589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teskey, R.; Wertin, T.; Bauweraerts, I.; Ameye, M.; McGuire, M.A.; Steppe, K. Responses of tree species to heat waves and extremeheat events. Plant Cell Environ. 2015, 38, 1699–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, A.; Strobl, S.; Veit, B.; Oberhuber, W. Impact of drought on the temporal dynamics of wood formation in Pinus sylvestris. Tree Physiol. 2010, 30, 490–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peguero, C.; López-Fernández, J.; Solla, A. Physiological Responses and Adaptation Mechanisms of Scots Pine to Drought Stress. Tree Physiol. 2023, 43, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feichtinger, L.M.; Siegwolf, R.T.W.; Gessler, A.; Buchmann, N.; Lévesque, M.; Rigling, A. Plasticity in gas-exchange physiology of mature Scots pine and European larch drive short- and long-term adjustments to changes in water availability. Plant Cell Environ. 2017, 40, 1972–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boczoń, A.; Wróbel, M. The influence of drought on the water uptake by Scots pines (Pinus sylvestris L.) at different positions in the tree stand. Leś. Pr. Badaw./For. Res. Pap. 2015, 76, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, P.B.; Sendall, K.M.; Stefanski, A.; Rich, R.L.; Hobbie, S.E.; Montgomery, R.A. Effects of climate warming on photosynthesis in boreal tree species depend on soil moisture. Nature 2018, 562, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]