Abstract

Air pollution is a major but often under-integrated driver of forest dynamics at the global scale. This review combines a bibliometric analysis of 258 peer-reviewed studies with a synthesis of ecological, physiological, and biogeochemical evidence to clarify how multiple air pollutants influence forest structure, function, and regeneration. Research output is dominated by Europe, East Asia, and North America, with ozone, nitrogen deposition, particulate matter, and acidic precipitation receiving the greatest attention. Across forest biomes, air pollution affects growth, wood anatomy, nutrient cycling, photosynthesis, species composition, litter decomposition, and soil chemistry through interacting pathways. Regional patterns reveal strong context dependency, with heightened sensitivity in mountain and boreal forests, pronounced ozone exposure in Mediterranean and peri-urban systems, episodic oxidative stress in tropical forests, and long-term heavy-metal accumulation in industrial regions. Beyond being impacted, forests actively modify atmospheric chemistry through pollutant filtration, aerosol interactions, and deposition processes. The novelty of this review lies in explicitly framing air pollution as a dynamic driver of forest change, with direct implications for afforestation and restoration on degraded lands. Key knowledge gaps remain regarding combined pollution–climate effects, understudied forest biomes, and the scaling of physiological responses to ecosystem and regional levels, which must be addressed to support effective forest management under global change.

1. Introduction

Forests are among the most important terrestrial ecosystems, providing essential ecosystem services such as carbon sequestration, climate regulation, biodiversity conservation, soil protection, water regulation, and socio-economic benefits. However, forest ecosystems worldwide are increasingly threatened by multiple anthropogenic stressors, among which atmospheric air pollution plays a critical role. Over the last two decades, forest research has evolved from documenting visible forest decline caused by air pollution toward a broader and more integrative understanding of forest health, encompassing productivity, resilience, and the capacity of forests to sustain ecosystem services under multiple environmental pressures [1].

This shift in perspective has highlighted the need to consider forests as complex systems influenced by interacting drivers rather than isolated stress factors. In particular, the combined effects of air pollution and climate change—including elevated ozone concentrations, altered nitrogen deposition, and changes in carbon and water availability—have emerged as critical research themes. Current evidence suggests that air pollution may pose increasing risks to forests under changing climatic conditions, especially when interacting with abiotic and biotic stressors such as drought, competition, pests, and fire. These interactions generate antagonistic and synergistic responses that affect ecosystem services related to productivity, biodiversity, soil protection, water balance, and socio-economic value, underscoring the need for integrated research, monitoring, and modeling approaches [1].

European forests are expected to undergo substantial transformations driven by climate change, which, when coupled with changes in air quality, may significantly influence forest productivity, species composition, and carbon storage in vegetation and soils. Despite extensive research efforts, key knowledge gaps remain. These include: (i) understanding how changes in air quality (e.g., trace gas concentrations) interact with climate and site-specific factors to shape ecosystem responses, (ii) clarifying the role of biotic processes in ecosystem functioning, (iii) developing tools that enable mechanistic understanding and scaling from local observations to regional and continental patterns, and (iv) integrating empirical data with modeling frameworks to achieve a unified and predictive understanding of forest dynamics [2].

In parallel, recent studies have emphasized the reciprocal relationship between forests and air pollution, highlighting the capacity of forest ecosystems to mitigate air pollution and its associated health impacts. Using satellite imagery, individual-level mortality records, and air quality data across China, Liu et al. [3] demonstrated that increased forest greenness improves air quality and reduces mortality. A 10-percentage-point increase in seasonal average normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) was associated with a 2.6-point improvement in the air quality index (AQI), corresponding to reductions of 1.09% in cardiorespiratory deaths and 0.87% in non-cardiorespiratory deaths. Moreover, forest greenness was shown to mitigate pollution-related mortality risks, with particularly strong benefits observed among elderly males. These findings suggest that the health benefits derived from increased forest cover can substantially outweigh the costs of forest conservation [3].

Despite these benefits, forest ecosystems are projected to face increasing exposure to harmful air pollutants at the global scale. By 2100, approximately 49% of forests worldwide (around 17 million km2) are expected to be exposed to damaging levels of tropospheric ozone. Although sulfur dioxide (SO2) emissions have declined by 48% in North America and 25% in Europe, sulfur deposition is still projected to threaten up to 5.9 million km2 of forest area by 2050. Meanwhile, nitrogen oxide emissions have remained stable or slightly increased, leading to significant changes in the SO42−/NO3− ratio in precipitation over the past two decades, alongside shifts in temperature and precipitation regimes. Although long-term monitoring programs have generated extensive datasets, these data often lack the conceptual and statistical rigor required to detect subtle trends in forest health or to establish causal relationships, highlighting the need for improved and restructured monitoring strategies [4].

The effects of air pollution on forest ecosystems can be broadly categorized into three exposure classes. At low exposure levels (Class I), forests function primarily as sinks for atmospheric pollutants, often with negligible or even positive effects on ecosystem functioning. At intermediate exposure levels (Class II), air pollution may subtly impair physiological processes at the species level, affecting nutrient balance, photosynthesis, reproduction, and resistance to pests and diseases. These changes can lead to reduced productivity, biomass loss, or gradual shifts in species composition. At high exposure levels (Class III), acute damage may result in tree morbidity or mortality, triggering pronounced alterations in ecosystem structure, hydrology, nutrient cycling, erosion processes, microclimate, and overall ecosystem stability [5].

The synergistic interactions between air pollution and climate change—particularly elevated ozone concentrations and altered nitrogen, carbon, and water availability—represent a critical frontier for forest research. Climate-induced changes in water dynamics have been widely documented [6,7,8], and forests play a central role in regulating the hydrological cycle through evapotranspiration, infiltration, and runoff. However, climate change can disrupt these processes, intensifying soil erosion and surface runoff [9,10,11], increasing forest vulnerability, mortality rates, and shifts in species composition, while reducing the capacity of forests to deliver key ecosystem services [12,13,14,15].

Although numerous reviews have addressed air pollution impacts [16,17,18,19] and broader forest ecosystem responses [20,21,22,23], a notable gap remains in the literature regarding the role of air pollution in the afforestation of degraded lands. This gap is particularly critical given the increasing reliance on afforestation as a strategy for ecosystem restoration, climate mitigation, and land degradation reversal. Accordingly, this review is guided by three main objectives: (1) to identify the dominant pollutants and spatial patterns shaping forest dynamics across biomes; (2) to synthesize the physiological, ecological, and biogeochemical mechanisms through which air pollution influences forest structure, function, and regeneration; and (3) to assess how these processes affect afforestation outcomes on degraded lands under interacting pressures from climate change and land use. By addressing these questions, the review aims to highlight critical knowledge gaps that currently constrain restoration planning and sustainable forest management.

2. Materials and Methods

The methodological workflow consisted of two complementary components. The first involved a bibliometric assessment designed to identify global research patterns concerning the influence of air pollution on forest dynamics. The second component comprised a traditional literature review aimed at synthesizing thematic insights from the selected body of work. While bibliometric analyses provide a structured, quantitative overview of publication trends and intellectual linkages, they are inherently constrained by database coverage, keyword selection, and document indexing practices. These limitations were explicitly considered when interpreting the results and integrating them into the qualitative synthesis.

2.1. Bibliometric Analysis

2.1.1. Data Sources and Search Strategy

The bibliometric phase drew upon two major international bibliographic databases: Scopus and the Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI-Expanded) within the Web of Science (WoS) platform. Searches were conducted using the core phrase “influence of air pollution on forest dynamics” together with an extended list of subject-specific terms. Additional keywords (e.g., forest health, atmospheric pollution, forest decline, ecosystem responses, environmental stress) were combined through Boolean operators AND and OR to construct a comprehensive search strategy capturing broad and specific aspects of air pollution impacts on forest ecosystems.

Although the phrase “forest dynamics” was used as a central conceptual anchor, we acknowledge that relevant studies may employ alternative terminology (e.g., tree growth, stand development, ecosystem change) without explicitly using this term. To mitigate this potential bias, the search strategy incorporated multiple related expressions describing forest condition, productivity, decline, and ecosystem responses. Nevertheless, some relevant studies may remain outside the retrieved dataset due to differences in terminology or indexing practices.

All retrieved records were screened and refined according to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) framework to ensure transparency and reproducibility [24].

2.1.2. Search Strings

To facilitate methodological reproducibility, the exact search strings used in each database are presented below. Standard operators, quotation marks, and field tags were adapted as required by individual database rules. To retrieve the most relevant literature, we adapted the search strings to the specific syntax and Boolean logic used by each database. Scopus and Web of Science (WoS) apply Boolean operators with different precedence rules and allow different forms of truncation and field-specific search structures. Therefore, the keywords were aligned conceptually but adjusted technically for each platform. In Scopus, the search was conducted in the TITLE-ABS-KEY field, which requires explicit grouping of synonyms, whereas in WoS the Topic (TS) field automatically searches title, abstract, keywords, and Keywords Plus. Consequently, minor variations in structure and term grouping were necessary to ensure that both databases captured the same thematic scope—air pollution effects on forest dynamics, decline, health, productivity, and associated ecosystem responses—while remaining fully compliant with each platform’s search rules.

Scopus (advanced search; field: TITLE-ABS-KEY): TITLE-ABS-KEY(“air pollution” AND “forest dynamics” OR “forest decline” OR “forest health” OR “atmospheric pollutants” OR “ecosystem response*”)

Web of Science—SCI-Expanded (topic search; TS): TS = (“air pollution” AND “forest dynamics” OR “forest decline” OR “forest productivity” OR “tree growth” OR “atmospheric deposition”)

Wildcard characters (*) were included where appropriate to expand the search to plural forms and morphological variations. Slight adjustments were applied between databases to maintain logical consistency while accommodating platform-specific syntax.

2.1.3. Search Parameters

Time range: no temporal restrictions; all years available in Scopus and WoS at the time of data extraction were considered.

Document types: peer-reviewed research articles and review papers were included as the core literature. Conference papers and book chapters were also retained where they provided substantive empirical results or methodological innovations relevant to air pollution–forest interactions. We recognize that the inclusion of non-journal literature introduces a degree of heterogeneity; however, these sources were retained to capture emerging research topics and region-specific evidence that may not yet be fully represented in journal publications.

Excluded records: editorial materials, letters, notes, and theses were removed during the screening process.

2.1.4. De-Duplication and Data Validation

Duplicate entries were eliminated using a two-level procedure:

1. Automated removal through DOI and title matching in Microsoft Excel.

2. Manual verification of residual cases by comparing titles, authors, publication years, and journal names to resolve incomplete metadata or inconsistent DOI information.

This procedure resulted in the removal of 87 duplicate records. Additional quality control steps included verification of bibliographic metadata, correction of typographical or OCR-related errors, and harmonization of author and institutional names. All modifications were logged in an internal audit file.

2.1.5. Eligibility Criteria

A two-stage screening approach was employed:

-Title and abstract screening, undertaken independently by two reviewers.

-Full-text evaluation, applied to all potentially relevant papers.

Inclusion criteria required that articles:

-were peer-reviewed;

-directly addressed air pollution impacts on forest ecosystems, forest dynamics, or tree physiological responses;

-provided adequate methodological and descriptive information;

-contained complete bibliographic metadata.

Exclusion criteria applied to:

-documents lacking peer review (e.g., editorials, correspondence, theses);

-studies not focused on forest ecosystems or lacking relevant pollutant/forest interaction data;

-papers in which air pollution was only tangentially mentioned;

-records without accessible full texts or missing abstracts.

Full-text exclusions were categorized using the following codes:

(A) outside the thematic scope, (B) non-peer-reviewed, (C) insufficient pollution-forest data, (D) inaccessible full text, (E) inadequate methodological description.

2.1.6. Screening Process

The screening procedure was performed independently by two reviewers (A and B). Any publication considered relevant by at least one reviewer during the first stage progressed to full-text review. Conflicts or discrepancies in the second stage were resolved through consultation with a senior reviewer (C).

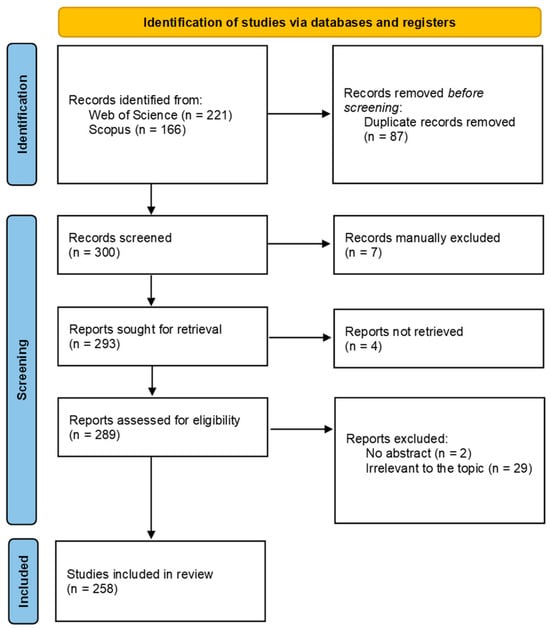

The search initially identified 387 publications (166 in Scopus; 221 in WoS). After duplicate removal, 300 unique records remained. Application of inclusion/exclusion criteria resulted in the removal of 8 items due to manual filtering, 5 inaccessible papers, 5 records without abstracts, and 86 irrelevant publications. Ultimately, 258 articles were retained for bibliometric mapping and qualitative interpretation (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Selection process of the eligible reports based on the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram.

Bibliometric analyses were performed using Web of Science Core Collection (v.5.35) [25], Scopus [26], Microsoft Excel 2024 [27], and Geochart [28]. In addition, VOSviewer (v.1.6.20) [29] was used to construct visual networks for co-authorship, co-citation, and keyword co-occurrence analyses. These analyses were not intended to be purely descriptive; rather, they were used to identify dominant research clusters, influential publications, and underrepresented themes that subsequently guided the structure and emphasis of the narrative synthesis.

2.2. Traditional Literature Review

The second phase consisted of a narrative synthesis based on the refined dataset. A subset of 258 publications underwent detailed qualitative assessment to identify dominant research themes and conceptual linkages. A total of 258 publications met our inclusion criteria and were fully analyzed. Of these, 150 were selected for citation in the manuscript because they provided the most directly relevant insights, empirical evidence, or conceptual contributions to our synthesis.

Importantly, the outcomes of the bibliometric analysis informed the narrative review by highlighting major thematic clusters, frequently co-occurring keywords, and gaps in geographic or topical coverage. These quantitative signals were used to prioritize themes, balance regional representation, and explicitly address underexplored research questions within the narrative discussion.

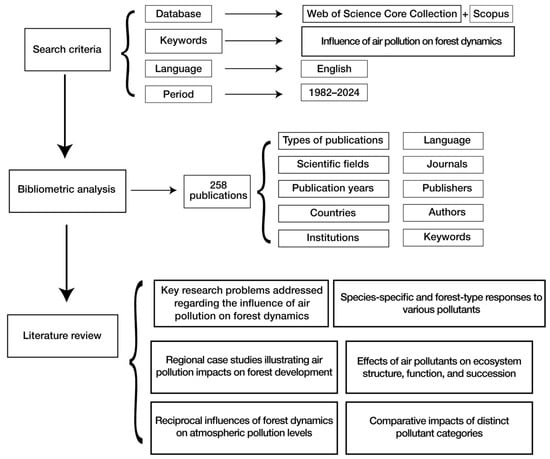

The selected literature was organized into six overarching thematic domains: (1) Key research problems addressed regarding the influence of air pollution on forest dynamics; (2) Species-specific and forest-type responses to various pollutants; (3) Regional case studies illustrating air pollution impacts on forest development; (4) Effects of air pollutants on ecosystem structure, function, and succession; (5) Reciprocal influences of forest dynamics on atmospheric pollution levels; (6) Comparative impacts of distinct pollutant categories (e.g., ozone, nitrogen compounds, particulate matter).

To address potential thematic overlap among the six research domains, each publication was evaluated for its primary and, where applicable, secondary thematic alignment. Publications that legitimately spanned more than one domain were coded accordingly to ensure an accurate representation of cross-cutting research areas. Based on this coding process, we generated a statistical table summarizing the number of studies associated with each thematic domain, including cases of multiple classification. This table (Table 1) provides a transparent overview of literature distribution across domains and highlights areas of research convergence and divergence within the dataset. The classification results support the narrative synthesis by clarifying the relative weight of each thematic cluster in the selected body of evidence.

Table 1.

Distribution of the 258 reviewed publications across the six thematic research domains. (Values represent the number of studies assigned to each thematic domain; studies could be coded into more than one domain where appropriate).

A schematic overview of the complete methodological framework is provided in Figure 2, which summarizes the workflow from initial data acquisition through quantitative bibliometric assessment and final qualitative synthesis.

Figure 2.

Schematic presentation of the workflow used in this research.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. A Bibliometric Review

A total of 258 publications related to influence of air pollution on forest dynamics were compiled. The dataset was predominantly composed of research articles (217 articles, representing 84% from the total publications), followed by conference proceedings (28; 11%), review papers (11; 4%), book chapters (2; 1%).

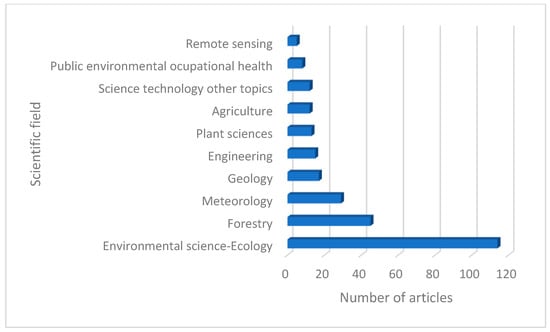

According to the Web of Science classification, the published articles are assigned to various research areas. Among these, Environmental Sciences & Ecology stands out (with 114 articles), followed by Forestry (with 45 articles) and Meteorology (with 29 articles) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The main 10 scientific areas with publication related to influence of air pollution on forest dynamics.

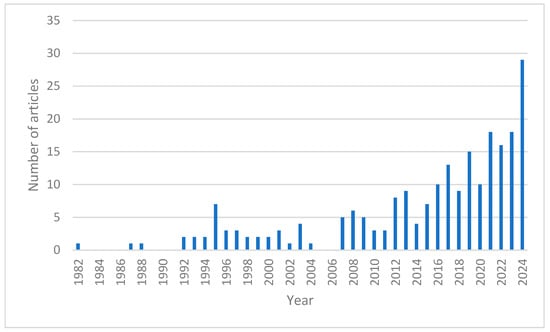

Published articles were rare during the early period (1982–1992), but their number increased steadily after 2012 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Annual distribution of articles on influence of air pollution on forest dynamics.

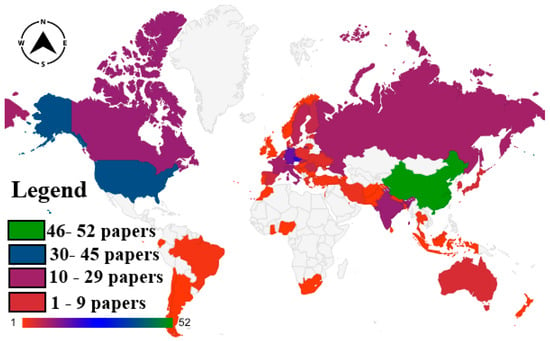

Our inventory identified a total of 63 countries to which the authors who have published indexed articles on this topic so far belong (Figure 5). The most prominently represented countries in terms of publication output were China (52 articles), the United States of America (40 articles), Czech Republic (22 articles), and Germany (16 articles).

Figure 5.

Countries with contributing authors of articles on influence of air pollution on forest dynamics.

The countries where the authors of these articles come from can be grouped into several clusters; of these, three are more representative (each containing at least six countries). Cluster 1 includes only European countries: Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, England, Estonia, Finland, Italy, Lithuania, Slovenia, and Sweden. Cluster 2 includes countries from Asia, America, and Australia: Australia, Canada, India, Japan, China, Singapore, South Korea, and the USA. Cluster 3 again includes European countries: Germany, Greece, the Netherlands, Spain, Switzerland, and Ukraine. These clusters highlight how research activity is structured geographically and may reflect regional scientific collaborations, funding priorities, and shared environmental concerns. In Cluster 1, the grouping of Northern and Central European countries likely arises from long-standing research networks focused on transboundary air pollution and forest health monitoring programs, such as ICP Forests. The studies from these countries often share methodological approaches, including long-term forest inventory data and standardized monitoring protocols. In Cluster 2, which spans Asia, North America, and Australia, the studies tend to focus on rapidly changing emission patterns, urbanization pressures, and large-scale atmospheric transport. The presence of major emitter countries (e.g., China, India, USA) alongside nations with advanced monitoring technologies (e.g., Japan, South Korea, Australia) suggests a network driven more by global research themes than by regional proximity. Cluster 3 consists predominantly of Western and Southern European countries characterized by mixed Mediterranean and temperate forest systems. Here, studies frequently address ozone impacts, drought-pollution interactions, and region-specific forest responses. This cluster likely reflects thematic similarity in ecological challenges rather than geographic closeness alone. Overall, the clustering indicates that research on air pollution and forest dynamics forms distinct regional and thematic communities. These groupings highlight shared scientific interests, common environmental pressures, and collaborative networks among the contributing countries.

The articles were published across 133 different journals. The most prominently represented journals were Science of the Total Environment, Forest Ecology and Management, Environmental Pollution and Forests (Table 2).

Table 2.

Leading journals publishing articles on influence of air pollution on forest dynamics.

The leading institutions affiliated with the authors of these articles, ranked by publication volume, include the Chinese Academy of Sciences (16 articles), Czech University of Life Sciences Prague (14 articles) and Swiss Federal Institutes of Technology Domain (8 articles) and the major publishers: Elsevier (60 articles), Springer Nature (29 articles), MDPI (18 articles), and Wiley (11 articles).

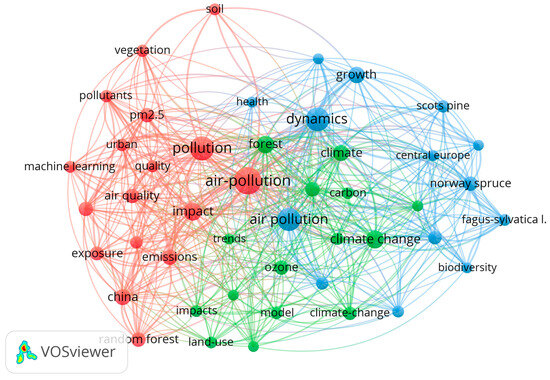

Among the keywords analyzed in these articles, the most frequently occurring were air pollution, pollution, dynamics, impact and climate change.

Based on their interconnections, the keywords can be grouped into several thematic clusters that reflect the major research themes in the field. Three clusters are particularly representative (each containing more than 10 keywords). The first cluster includes terms primarily associated with air pollution and its quantitative assessment (e.g., pollution, air pollution, particulate matter, PM2.5, pollutants). This cluster also contains several analytical and modeling approaches frequently used to evaluate pollution effects—such as random forest, modeling, machine learning. Their presence indicates that methodological tools are closely linked to pollution-focused studies. The second cluster comprises keywords related to climate and atmospheric chemistry (e.g., climate, climate change, nitrogen, carbon, tropospheric ozone, ozone), highlighting the tight connection between pollution and broader environmental change. The third cluster includes terms associated with forest ecosystems and pollution-sensitive species (e.g., Fagus sylvatica, Norway spruce, Scots pine, forests, growth, radial growth), emphasizing the biological and ecological impacts of pollution on forest dynamics (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Authors’ keywords related to influence of air pollution on forest dynamics.

As in the case of other review-type articles [30,31,32], journal articles account for the largest share of the publications. In this case, however, the notably high proportion (11%) of proceedings papers stands out, reflecting the large number of symposia dedicated to this topic (both pollution and forest dynamics are, individually, subjects that are extensively debated within the scientific community).

The exponential increase in the number of published articles—particularly over the past decade—is a trend observed in other cases as well [33,34,35], and can be attributed to the growing number of authors and scientific journals recorded during this period, as well as to the increasing importance of the topic under investigation.

It is already well established that China and the USA are the countries with the highest numbers of authors studying various scientific aspects [36,37,38], but in this case, the presence of the Czech Republic is a pleasant surprise.

The keywords used are, naturally, primarily those related to the search conducted, but as in other situations [39,40,41], the presence of keywords reflecting the latest trends in international research is noteworthy.

Taken together, the bibliometric results identify clear geographic concentrations, dominant pollutant categories, and recurrent research themes, while also revealing gaps in biome coverage and thematic integration. These quantitative patterns provide the structural backbone for the following synthesis, which moves beyond publication trends to examine how the identified pollutants operate through ecological and physiological mechanisms and how these mechanisms scale to forest dynamics.

3.2. Literature Review

3.2.1. Main Problems Addressed in Studies on Influence of Air Pollution on Forest Dynamics

Building on the bibliometric patterns identified above, the literature review synthesizes how air pollution influences forest dynamics through recurring ecological, physiological, and biogeochemical processes. Rather than isolated case studies, the reviewed evidence reveals consistent patterns that link observed publication trends to underlying mechanisms operating across spatial and temporal scales (Table 3).

Table 3.

Some of the analyzed issues in articles about influence of air pollution on forest dynamics (extract from the literature).

At the broadest level, many studies adopt global or regional perspectives to evaluate long-term pollution pressures on forest ecosystems. Broad-scale assessments [42,45,58] consistently identify air pollution as a persistent and global determinant of forest health, productivity, and demographic trajectories. In this regard, the identification and deployment of resilient species and provenances developed through genetic improvement programs has been proposed as a feasible strategy for forest restoration under polluted environments [59,60,61,62,63].

A second dominant research theme concerns atmospheric chemistry and deposition processes. Numerous studies demonstrate that pollutants such as acidic compounds, nitrogen, and ozone are transferred from the atmosphere to forest ecosystems through wet and dry deposition, with profound ecological consequences. Research on acid deposition [46] and long-term ozone or nitrogen monitoring [53,55,56] shows that these inputs modify soil chemistry, disrupt nutrient availability, and alter physiological processes such as foliar nutrient retranslocation. These chemical changes propagate through the system, influencing microbial activity, root functioning, and plant metabolism, and ultimately reshaping forest structure and functioning.

Closely linked to deposition processes are vegetation-level and physiological responses to pollution stress. Empirical evidence from European and Asian forests indicates that polluted environments are associated with changes in species composition, growth rates, and wood anatomy [47,49,52]. These responses reflect both acute stress interactions, such as pollution combined with frost events, and chronic shifts in atmospheric chemistry. The convergence of findings across different forest types and climatic regions underscores the widespread sensitivity of temperate forests to pollutant exposure and suggests that pollution acts as a selective force influencing forest assemblages over time.

Another recurring pattern involves the role of industrial, urban, and combustion-related pollution sources. Studies conducted near industrial facilities reveal that heavy metal contamination leads to soil degradation and reductions in plant diversity [40]. Similarly, investigations of forest fires and peat-forest burning [48,54] show that episodic but intense pollution pulses can cause substantial short- to medium-term ecological impacts. These sources often interact with climatic variability and land-use change, amplifying their effects and complicating attribution to single stressors.

Several contributions emphasize that forest responses to air pollution cannot be fully understood without considering broader socio-ecological contexts. Modeling and observational studies linking pollution with land-use change, urbanization, and climate variability [46,51] demonstrate that forest exposure and vulnerability are shaped by human activities and regional climate trends.

Mechanistic insights into forest–atmosphere interactions are provided by studies focusing on pollutant exchange processes at the canopy–atmosphere interface. Investigations of gas-phase exchanges of semivolatile compounds [43] and geographically explicit analyses of vegetation responses [57] illustrate that forests are not only passive recipients of pollution but also active components of atmospheric chemistry. Understanding these bidirectional fluxes is essential for improving predictive models of forest dynamics under changing air quality conditions.

Taken together, the reviewed literature reveals that air pollution influences forest dynamics through intertwined chemical, physiological, ecological, and socio-environmental mechanisms. While geographic coverage spans multiple continents, research efforts remain unevenly distributed, with a strong concentration in Europe, East Asia, and North America. This imbalance points to a significant knowledge gap in other forest biomes and highlights the need for expanded monitoring, experimental, and modeling studies to achieve a more comprehensive global understanding of pollution-driven forest change.

While these studies define the principal research questions and conceptual frameworks in the field, their implications become clearer when examined through the responses of specific forest types and tree species. The following section therefore shifts from thematic problems to organism- and stand-level responses, highlighting how pollution effects are expressed across functional forest types.

3.2.2. Forest Types and Species Responses to Air Pollution

A wide diversity of forest types and tree species has been investigated in relation to air-pollution impacts across different regions. Table 4 provides a synthesis of representative studies documenting how individual species, mixed stands, and entire forest ecosystems respond to various pollutants.

Table 4.

Some tree species and forest types cited in articles concerning the influence of air pollution on forest dynamics (extract from the literature).

Rather than reiterating individual study outcomes, the following synthesis groups forest responses by functional type and dominant pollutant pathways. Across taxa and regions, species-specific responses converge into a limited number of recurring patterns related to atmospheric deposition, ozone exposure, and industrial emissions. This approach highlights shared mechanisms and ecosystem-level implications while avoiding repetition of study-by-study descriptions.

This section synthesizes observed response patterns across coniferous, broadleaf, and mixed forests, emphasizing shared sensitivities and contrasting adaptive strategies under different pollution regimes.

Coniferous Forests: Sensitivity to Deposition and Industrial Emissions

Studies of coniferous forests consistently indicate high sensitivity to chronic sulfur and nitrogen deposition and to industrial point-source emissions, particularly in montane and managed systems. Abies alba has been examined from a general perspective [64] as well as in mixed stands with Picea abies [84], while Picea abies itself has been frequently assessed under acidic deposition pressures in the Czech Republic [73]. These studies consistently indicate that long-term sulfur and nitrogen deposition can alter growth patterns, nutrient balance, and stand productivity, particularly in montane and managed forest systems.

Additional conifer-focused studies include Picea sitchensis exposed to elevated N and S deposition in Germany [74] and Picea rubens in the USA, where forest condition changes linked to acidic deposition were evaluated [75].

Research on Larix species encompasses effects of predicted nitrogen deposition in Japan [55] and, in combination with Pinus species, assessments of water-use efficiency dynamics in China [77]. Mediterranean and eastern European research further includes work on Pinus halepensis and P. nigra under atmospheric deposition in Croatia [76], and studies of pulp-and-paper emissions affecting Pinus sylvestris in Poland and Russia [78,79]. Collectively, these studies show that conifers respond not only to acidic inputs but also to industrial point sources, with physiological adjustments (e.g., water-use efficiency) often preceding visible decline.

Broadleaf Forests: Ozone, Nutrient Imbalance, and Physiological Responses

Broadleaf forests show pronounced sensitivity to ozone exposure and nutrient imbalance, with physiological and litter-mediated responses often preceding visible structural change. Responses of birch (Betula spp.) and poplar (Populus spp.) to air pollutants were reviewed for Central Europe [66], while nutrient status in Fagus sylvatica forests was evaluated in southern Europe [67].

Investigations in East Asia include Ginkgo biloba leaf-litter responses to elevated O3 in China [68] and Quercus variabilis in studies addressing vegetation productivity and its influence on negative air ions [72]. Additional research has addressed Quercus ilex in peri-urban Spanish forests [70] and aerosol fluxes in Quercus–Carpinus forests in Italy [69]. These studies highlight how broadleaf species often serve as sensitive indicators of ozone stress, altered litter decomposition dynamics, and canopy-level pollutant processing.

North American studies contribute further insights, with Quercus macrocarpa and Populus tremuloides used to assess the effects of emissions from a coal-fired power station in Canada [71], and combined CO2 and O3 impacts on Populus tremuloides and Betula papyrifera tested in the USA [80]. Experimental approaches in these systems emphasize interactive pollution effects, showing that ozone responses may be modified by rising CO2 concentrations.

Mixed Forests and Multispecies Comparisons as Indicators of Ecosystem-Level Effects

Mixed-species forests provide integrative insight into ecosystem-level pollution effects by revealing contrasting species sensitivities under identical exposure conditions. Investigations include Fagus sylvatica–Abies alba–Picea abies mixtures [68] and mixed-species comparisons of Abies alba versus Picea abies [84]. These studies demonstrate that interspecific differences in growth and basal-area increment can clarify pollution signals that may be obscured in single-species analyses.

Additional studies have examined deciduous–conifer mixtures exposed to roadside dust in the Czech Republic [83] and the accumulation of mercury in foliage of Populus alba, Tilia cordata and Prunus avium in Romania [82].

Regional Patterns and Dominant Pollution Drivers

Regional patterns in forest responses largely reflect dominant emission sources and regulatory histories rather than fundamentally different ecological mechanisms. Central and Eastern Europe show a strong emphasis on acidic, nitrogen, and sulfur deposition as well as industrial emissions, particularly in the Czech Republic, Poland, and Germany [73,74,78,83]. Mediterranean studies predominantly address atmospheric deposition and peri-urban pollution pressures [66,70], while East Asia—especially China—focuses on ozone pollution, nitrogen interactions, and physiological or litter-based responses [68,72,77,81]. North American research often centers on industrial point sources and controlled CO2–O3 experiments [71,80]. These patterns underline how local emission profiles shape both research priorities and observed forest responses.

Integrated Physiological and Ecosystem Responses

Across forest types, air pollution induces a spectrum of physiological and biogeochemical responses that frequently occur without immediate visible damage [67,68,69,74,75,77,82].

Synthesis and Implications

Taken together, the integrated evidence shows that air pollution exerts measurable and multifaceted influences across global forest types. Both coniferous and broadleaf forests are vulnerable to a spectrum of pollutants, and mixed stands provide particularly valuable insights into ecosystem-level effects. Despite differences in regional focus and methodology, a consistent pattern emerges: air pollution acts as a pervasive driver of physiological stress, nutrient imbalance, and altered ecosystem processes, reinforcing its role as a key factor shaping contemporary forest dynamics.

3.2.3. Regional Examples of Air Pollution Impact on Forest Dynamics

Regional case studies provide an essential bridge between species-level mechanisms and large-scale forest dynamics, illustrating how similar physiological processes lead to divergent outcomes depending on climate, emission sources, and landscape context.

Arctic, Subarctic, and Northern Boreal Regions

Air pollution affects even remote Arctic and subarctic forests, where ecosystem sensitivity amplifies pollutant impacts. Evidence from the Kola and Taimyr Peninsulas demonstrates that sulfate and trace metal deposition alters vegetation composition, productivity, regeneration, soil chemistry, and biological activity [86]. Across these regions, morphological and physiological injury symptoms resemble those observed in temperate forests, indicating shared stress pathways. However, northern ecosystems exhibit distinctive damage patterns driven by open canopies, thin photosynthetic layers, and prolonged snow cover, resulting in differential injury above and below the snowline, simultaneous stand-level damage, and enhanced krummholz formation.

Pollution effects are strongly modulated by background stress. Species already constrained by cold, nutrient limitation, or shallow soils display lower tolerance thresholds, and the loss of pollution-sensitive taxa such as lichens can trigger rapid ecosystem degradation. At the same time, not all industrial pollution results in detectable growth suppression. Near the Arkhangelsk pulp and paper mill, dendrochronological analyses showed no significant relationship between pine radial growth and emissions from 2001–2018; growth trends followed expected age-related patterns with no synchronous or lagged pollution signal [79].

Mountain Forests of Central Europe

Mountain forests experience compounded stress from climate constraints and pollutant exposure. In the Orlické hory Mountains, forest structure and dynamics varied systematically with elevation and hilltop exposure [87,88]. Tree spatial patterns shifted from random at lower elevations to aggregated under strong hilltop effects, with regeneration showing similar clustering. These structural changes reflect the combined influence of wind exposure, temperature limitation, and pollutant loading.

Species-specific growth responses further illustrate pollution–climate interactions. Spruce exhibited long-term growth suppression after 1978, followed by recovery after 1998, while beech maintained stable growth over the twentieth century. Spruce radial growth was negatively correlated with SO2 and NOx concentrations, particularly during spring, and pollution effects intensified at summit locations. Temperature exerted a stronger influence than precipitation, indicating that pollution sensitivity is amplified under climatic limitation.

Tropical Forests: Amazon and Subtropical Asia

In tropical systems, air pollution effects are closely coupled with atmospheric dynamics. In the central Amazon, baseline ozone concentrations are low, but episodic peaks exceeding 75 ppbv occur due to biomass burning and long-range transport [89]. Convective storms play a critical role by transporting ozone-rich mid-tropospheric air to the forest canopy, producing short-term increases of up to 25 ppbv and sustaining elevated levels for several hours. These events intensify oxidation of biogenic volatile organic compounds, increase hydroxyl radical concentrations, and alter forest–atmosphere chemical exchange. The results challenge the perception of tropical forests as largely insulated from pollution and highlight the importance of extreme meteorological processes in shaping exposure.

In subtropical Asia, long-term observations from the Yunzhong Mountain forest reveal how air quality interacts with microclimate to influence negative air ions (NAIs), a component linked to ecosystem services and human well-being [90]. NAIs showed strong seasonal and diurnal patterns, peaking in summer and early morning. Concentrations were negatively associated with NO2 and particulate matter, while humidity exerted a positive influence. Structural equation modelling demonstrated that air pollutants have strong direct negative effects on NAIs, whereas meteorological variables act as positive drivers, with radiation influencing NAIs indirectly. These findings illustrate how pollution effects in subtropical forests often manifest through indirect atmospheric and physiological pathways rather than overt vegetation damage.

Urban and Peri-Urban Forests

Urban and peri-urban forests exemplify the dual role of forests as both pollution sinks and pollution-stressed ecosystems. In an oak–hornbeam forest of the Po Plain, aerosol flux measurements showed pronounced seasonal and size-dependent variability [69]. Leaf presence enhanced deposition of accumulation-mode particles but increased emissions of ultrafine and coarse particles, while leafless periods were characterized by net submicron emissions. Deposition velocities tracked leaf area index and stomatal conductance, emphasizing the importance of canopy phenology and physiological activity. Turbulence enhanced aerosol exchange, whereas near-condensing conditions reduced fluxes.

Across Mediterranean Quercus ilex forests in Spain, ozone emerged as the only pollutant consistently reaching phytotoxic levels [70]. Nitrogen compounds remained below direct toxicity thresholds but likely contributed to eutrophication through deposition. Peri-urban stands reduced below-canopy concentrations of gaseous pollutants, particularly NH3, demonstrating a clear air purification function alongside chronic exposure to urban emissions. Similarly, studies in urban green spaces of Xianyang revealed strong species-specific differences in particulate matter deposition [32,80]. Broadleaf communities showed high per-area deposition, while certain conifers accumulated large particle loads per leaf area. Community composition outweighed structural attributes in determining particulate dynamics, reinforcing the importance of species selection for urban forest management.

Central, Southern, and Western Europe

Long-term monitoring across Central Europe has largely refuted the concept of widespread pollution-driven forest dieback encapsulated in the term Waldsterben [91]. While localized foliar injuries associated with SO2, frost, or biotic agents occur, regional trends show stable or increasing tree growth, with climate exerting a stronger influence than air pollution. These findings emphasize the risk of overgeneralization and the need for site-specific assessments.

In southern Europe, evidence for large-scale pollution-induced decline is similarly limited [92]. Documented impacts include deterioration of coastal forests due to polluted sea spray, failures of poorly matched reforestation efforts, and oak declines linked to climatic stress and biotic interactions. Ozone causes visible foliar injury in several native species, but many effects remain non-visible and are often missed by broad surveys, indicating a need for more spatially explicit and sensitive monitoring approaches.

North America: United States and Canada

In North America, ozone and nitrogen deposition exert broad ecological effects, while sulfur pollution remains important at local scales [93]. Modelling studies from regions such as the San Bernardino Mountains and Hubbard Brook demonstrate that future forest function depends on interactions among climate change, pollutant deposition, and additional stressors such as drought and pests. These interactions influence hydrology, nutrient cycling, and productivity, with implications for carbon sequestration and water regulation.

In eastern Canada, tolerant hardwood forests on shallow, poorly buffered soils show decline symptoms linked to soil acidification [94]. Decreases in soil pH and base saturation, coupled with increased exchangeable aluminum, are associated with reduced forest health. Acid fog contributes to foliar injury and soil degradation in coastal areas, and chronic ozone exposure may further disrupt nutrient cycling. Without continued pollution reduction and adaptive management, long-term productivity in sensitive regions may be at risk.

Asia: Integrated Pressures of Pollution and Climate Change

Across Asia, forests are increasingly exposed to combined pressures from greenhouse gases, ozone, trace pollutants, and rapid climate change [95]. While individual stressors have been studied, their synergistic effects on forest dynamics remain poorly understood. Given the pace and scale of environmental change, this represents a critical research gap. Integrated monitoring, modelling, and experimental approaches are required to disentangle multiple stressors and to inform effective forest management and policy.

Regional Synthesis

Despite strong geographical contrasts in pollution sources and forest types, regional differences primarily reflect variations in exposure intensity and climatic modulation rather than distinct underlying mechanisms. Pollution effects are consistently amplified under climatic stress—particularly drought, cold limitation, or high radiation—indicating that air pollution most often acts as a stress multiplier rather than an isolated driver of forest change.

3.2.4. Effects of Air Pollution on Forest Dynamics

The mechanistic and regional patterns described above converge at the level of forest dynamics, where air pollution influences growth, structure, and long-term stability. This section integrates evidence across organizational levels, from physiological responses to stand-scale and ecosystem-scale change.

Growth Reduction, Stand Degradation, and Spatial Pollution Gradients

Across industrial and high-deposition regions, long-term exposure to air pollutants consistently reduced radial growth and forest vitality, with spatial patterns reflecting prevailing wind directions and proximity to emission sources [96,97]. Although emission reductions initiated partial recovery, growth trajectories rarely returned to reference levels, and affected stands frequently exhibited increased sensitivity to drought and climatic extremes, indicating persistent physiological legacy effects.

Together, these studies indicate that pollution does not act in isolation but interacts strongly with climatic extremes and biotic agents, accelerating stand-level decline and reducing long-term resilience.

Pollutant Effects on Wood Anatomy and Structural Traits

Air pollution also generated measurable shifts in wood anatomical characteristics. In the Ore Mountains, extreme winter pollution (1995/96) caused substantial reductions in lumen width, tracheid number, and cell wall thickness in Picea abies from heavily damaged stands [40]. Differences between earlywood and latewood responses indicated distinct reaction dynamics, and stand recovery required approximately three years depending on the anatomical parameter considered.

Physiological and Biochemical Responses of Needles

Studies in industrial regions demonstrated species-specific alterations in needle pigment composition. In the Ufa industrial center, pollution altered the chlorophyll and carotenoid profiles of Pinus, Picea, and Larix species, with no uniform adaptive trend among taxa [98]. Although chlorophylls a and b remained relatively stable structurally, their relative proportion increased under pollution, accompanied by a decline in carotenoids. Larix, despite its high photosynthetic potential, showed the greatest pigmental sensitivity to technogenic load.

Interactions Between Ozone Exposure and Litter Decomposition

Elevated ozone concentrations in urban forests influenced litter chemistry and decomposition processes. In open-top chamber experiments with Ginkgo biloba, exposure to 120 ppb O3 significantly increased leaf K content while reducing phenols and soluble sugars, without altering C, N, P, lignin, or tannins [51]. Although overall mass loss during the 150-day decomposition period did not differ significantly between ambient and elevated ozone, early-stage decomposition slowed under high O3 while later stages were slightly accelerated. Nutrient release patterns were strongly influenced by seasonal conditions regardless of treatment.

These findings suggest that ozone can subtly modify litter quality and decomposition timing rather than total decomposition rates. Such shifts may alter short-term nutrient availability and microbial activity, linking atmospheric pollution to ecosystem-level nutrient cycling processes.

Crown Condition, Soil Chemistry, and Ozone-Related Symptoms

Assessments of Fagus sylvatica at long-term monitoring sites indicated interactions among foliar nutrition, soil acidity, and atmospheric pollution [99,100]. Defoliation peaked in 1996 following drought, and biotic stressors (notably Rhynchaenus fagi) further contributed to canopy decline. Visible ozone injury on Fagus and Vaccinium myrtillus suggested contributions from O3 and anthropogenic hydrocarbons, supported by measured high ozone concentrations. Soils were nutrient-poor and desaturated in base cations, with frequent acidic precipitation episodes, particularly in winter.

This combination of foliar injury, soil degradation, and biotic stress underscores the cumulative nature of pollution impacts. Canopy decline cannot be attributed to a single driver but instead emerges from interacting chemical, climatic, and biological pressures.

Global Patterns of Atmospheric Deposition and Ozone Exposure

Globally, forest canopies enhance pollutant deposition due to their rough surface structure and aerodynamic properties [101]. In both Scottish and German sites, forests received substantially higher S and N deposition than adjacent moorlands. Model simulations showed increasing global exposure to phytotoxic ozone levels (>60 ppb): from 0% of forest area in 1860, to 6% in 1950, 24% in 1990, and potentially nearly 50% by 2100. Acid deposition is projected to expand particularly in tropical and subtropical regions, with 17% of global forests expected to receive >1 kg H+ ha−1 yr−1 as sulfur by 2050.

These trends indicate that pollution pressures historically concentrated in temperate industrial regions are becoming globally pervasive. As a result, stress responses documented in European forests may increasingly characterize tropical and subtropical systems, where background resilience and soil buffering capacity may differ substantially.

Modeling the Combined Influence of Pollution and Population Pressure

Mathematical modeling further highlighted the interacting effects of atmospheric pollution and human land-use pressure on forest dynamics [102]. Pollutants reduced intrinsic forest growth rates, while population-driven land use decreased carrying capacity [103]. The model exhibited parameter-dependent bifurcations and, counterintuitively, demonstrated stabilizing effects when incorporating time-delayed pollutant impacts.

These modeling results reinforce the view that pollution impacts are systemic and temporally complex. Delayed responses imply that present-day forest conditions may reflect past pollution regimes, complicating attribution and management decisions.

Integrated Synthesis

Collectively, these studies show that air pollution affects forest ecosystems through multiple, interacting pathways—reducing tree growth, altering wood structure and physiology, modifying nutrient cycling, and amplifying climatic and biotic stressors. While emission reductions often lead to partial recovery, many impacts persist for decades, indicating long-lasting legacy effects. The combined empirical and modeling evidence suggests that air pollution can fundamentally alter forest functioning and resilience, emphasizing the need for integrative, long-term approaches when assessing forest responses to anthropogenic stress.

3.2.5. Impacts of Forest Dynamics on Air Pollution

Urban Forests, Air Pollutant Removal, and Green Infrastructure Performance

Urban forests play a central role in regulating airborne particulate matter, yet their efficiency is strongly shaped by ongoing urbanization, vegetation structure, and landscape configuration. In Changchun City, long-term simulations revealed that despite an increase in overall forest cover from 18.09% (2000) to 24.59% (2020), rapid urbanization led to greater forest fragmentation and simplified patch geometry. Although 12% of forested areas were converted to impervious surfaces, gains from the conversion of cropland and wetland to forest maintained a net increase. These landscape changes substantially weakened PM2.5 removal capacity: total removal declined from 793 t yr−1 to 528 t yr−1, affecting nearly half of the urban area. Urban forest landscape patterns explained 72% of PM2.5 removal effectiveness, but the increasing dominance of impervious surfaces gradually surpassed this regulatory effect, ultimately reducing removal efficiency [104].

This result highlights a critical pattern emerging across urban systems: forest spatial configuration can be as important as total forest area in determining air-pollution mitigation capacity. Fragmentation reduces edge efficiency, alters airflow pathways, and limits cumulative deposition potential, suggesting that urban greening strategies focused solely on increasing canopy cover may fail to deliver expected air-quality benefits if spatial integrity is not preserved.

At the microscale, vegetation influences pollutant concentrations through both deposition and modification of airflow. Coupled PALM–VIDA simulations showed that vegetation substantially reduces PM concentrations within street canyons, while reductions in NO2 are more modest and depend heavily on vegetation structure and ventilation dynamics. Sparse canopies or species with open crowns improved airflow and were often more effective at lowering NO2 than denser vegetation, which can trap pollutants despite higher deposition rates. These findings underscore that both deposition and aerodynamic effects must be considered when designing vegetation for air-quality improvement, as unsuitable species placement may increase local pollutant levels [105].

Together with the Changchun results, these simulations demonstrate a scale-dependent trade-off: dense vegetation maximizes surface area for particle deposition, while open canopies enhance ventilation and gas-phase pollutant dispersion. This reinforces the need for context-specific vegetation design, particularly in narrow street canyons where aerodynamic effects may dominate over deposition.

Machine-learning approaches provide additional tools for evaluating vegetation-based mitigation of traffic-related air pollution (TRAP). Using CFD-generated datasets, RF, NN, and XGBoost models achieved high predictive accuracy (NRMSE 6–7%; R2 > 0.91) for downwind particle concentrations across a wide range of vegetation barrier configurations. Vegetation width, height, leaf area index, leaf area density, wind speed, and particle size emerged as the dominant predictors. These models offer a rapid and practical method for optimizing roadside vegetation design [106].

The use of machine learning addresses a key limitation identified in earlier studies: the difficulty of generalizing results across diverse urban forms and meteorological conditions. By integrating structural and atmospheric variables, these approaches facilitate adaptive, evidence-based planning, bridging the gap between site-specific CFD studies and large-scale urban policy.

Urban canopy characteristics also influence PM2.5 dynamics across functional zones. In a subtropical city, PM2.5 concentrations were highest in park zones, intermediate in traffic zones, and lowest in residential areas. Seasonal patterns showed winter peaks (84.00 ± 45.97 μg m−3) and summer minima (36.85 ± 17.63 μg m−3). Canopy metrics such as diameter, area, and volume correlated positively with PM2.5, but their influence remained minor compared with meteorological factors. Notably, a 1 m2 increase in canopy area increased PM2.5 by 0.864 μg m−3, whereas a 1 mm increase in rainfall raised PM2.5 by 13.665 μg m−3, indicating the dominant role of climate variability over canopy structure [107].

Canopy structure alone cannot compensate for unfavorable atmospheric conditions, underscoring the importance of integrating climate variability into assessments of green infrastructure performance.

Negative air ions (NAIs), often associated with air-quality benefits, also varied across green-infrastructure types. Suburban forests exhibited the highest NAI levels, while roadside greenery displayed the lowest. Relative humidity and temperature increased NAIs, while air pressure and PM10 concentrations reduced them. These patterns highlight vegetation type and microclimatic factors as key regulators of NAI generation [108], further supporting the conclusion that biophysical context, rather than canopy size alone, governs air-quality-related ecosystem services.

Vegetation as Pollutant Sinks, Bioindicators, and Hyperaccumulators

Analytical foliar diagnoses provide information on the nutritional state of trees (macro- and microelements), synergism, antagonism, and accumulation of essential nutrients and pollutants (from air, soil, and water). This method has been used in forest health monitoring, studies of complex forest decline, and assessments of urban (polluted) areas [109,110,111]. Accumulation of air pollutants in tree leaves represents a direct pathway of air decontamination, with species-specific capacities. Populus × canadensis proved most efficient in chlorine sequestration (31,320 ppm), Betula pendula and P. × canadensis in sulfur (8230–8724 ppm), and Acer pseudoplatanus in fluorine (770–1530 ppm) [112].

At the same time, plants function as effective bioindicators of air pollution, with species-specific sensitivities: Hypericum perforatum for fluorine, Urtica urens for ozone, Medicago sativa for carbon dioxide, Gmelina arborea for Air Pollution Tolerance Index (APTI) assessments, and Evernia prunastri for nitrogen oxides [109,113]. These biological indicators complement instrumental monitoring, particularly in regions lacking dense air-quality networks.

Forest mushrooms (e.g., Leccinum, Boletus) can accumulate radionuclides (U, Cs, Th, Pb, Po, Sr, Cd), serving as bioindicators of environmental contamination [114]. However, they are not considered hyperaccumulators compared with species such as Boehmeria nivea (uranium), Acer rubrum, Liquidambar styraciflua, and Liriodendron tulipifera (Cs-137, Sr-90, Pu-238), or Pteris vittata (arsenic) [115,116,117].

Some tree species and their symbiotic mushrooms are listed among hyperaccumulators of heavy metals: Pycnandra acuminata for nickel; Salix spp. for Ag, Cr, Hg, Se, Cd, Pb, U, and Zn; Pinus spp. for selenium and zinc; Chengiopanax sciadophylloides for manganese; Amanita strobiliformis for silver; and Amanita muscaria for selenium. Due to their exceptional uptake capacity, hyperaccumulators—particularly Salix spp.—are widely applied in phytoremediation and phytomining [118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125].

Collectively, these studies reveal that forests act not only as passive sinks for airborne pollutants but also as active biological filters and diagnostic tools, linking air pollution, ecosystem health, and remediation potential.

Forest Canopy Effects on Atmospheric Deposition

In Mediterranean pine ecosystems, substantial differences in ion deposition were observed between bulk open precipitation and throughfall. Throughfall consistently exhibited higher ion concentrations, with the strongest enrichment for K+. Total inorganic nitrogen deposition in Aleppo pine forests exceeded the critical load for Mediterranean pine systems, suggesting risks of eutrophication and soil acidification. Seasonal precipitation patterns and prolonged dry periods enhanced ion leaching from canopies, reinforcing the need for long-term monitoring under changing environmental conditions [76,114].

Forests also influence the atmospheric cycling of persistent organic pollutants. On the Tibetan Plateau, passive air sampling along Sygera Mountain showed significantly higher DDT concentrations during monsoon seasons (20.5–57.4 pg m−3) than in non-monsoon periods (9.2–27.4 pg m−3), confirming monsoon-driven long-range transport from South Asia. Comparisons between forested and open sites indicated that forest canopies reduced airborne DDTs by a factor of two, demonstrating strong interception and absorption capacities [125].

These findings highlight forests as biogeochemical reactors, amplifying atmospheric deposition while simultaneously protecting downwind environments by intercepting long-range transported pollutants.

Forest Fires and Pollutant Emission Dynamics

Forest fires represent major episodic sources of air pollutants across diverse regions. In Fujian Province (2000–2010), fire frequency initially increased and later declined, with total combusted biomass reaching 6.57 Mt. Emissions included 1.64 Mt CO2, 98.19 kt CO, 1.43 kt NOx, 9.43 kt CH4, 10.12 kt PM2.5, and other pollutants. Spatial patterns showed the highest emissions in southwestern Nanping, northwestern Sanming, and transitional areas between Nanping, Sanming, Ningde, and Fuzhou. Increasing ratios of PM2.5 from forest fires relative to industrial dust highlighted a growing influence of fires on regional air quality [126].

High-resolution modeling of the 2021 Manavgat fires in Turkey revealed strong meteorological control on plume behavior. WRF-Chem simulations, validated by ground-level and satellite observations, accurately predicted AOD (r = 0.93), aerosol index (r = 0.81), and PM10 (r = 0.82). A low-pressure system promoted plume lofting to 6 km above sea level, enabling regional smoke transport across Antalya. Persistent aerosol layers after fire suppression were linked to both local and remotely transported fire emissions [127].

In the Kathmandu Valley (2021), PM2.5 concentrations rose dramatically during two fire episodes, peaking at 371 μg m−3 and 280 μg m−3 compared with 199 μg m−3 during the pre-fire period. Despite more fire counts in the second episode, lower PM2.5 concentrations suggested a strong role of fire proximity and atmospheric dispersion. A two-day lag between ignition and PM2.5 increase was observed, with pollutant-specific responses: HCHO reacted rapidly, while AOD and CO exhibited delayed increases. Low wind speed, temperature, and humidity exacerbated pollution accumulation [128].

Similarly, in Kalimantan (2015), extensive peat-forest fires during El Niño conditions generated severe PM10 pollution. HYSPLIT trajectory modeling showed that dispersion patterns were governed by wind fields and topography, producing large spatial contrasts between Banjarbaru and Palangka Raya [129].

These studies collectively demonstrate that fire impacts on air quality are controlled as much by atmospheric dynamics as by fire intensity, and that climate-driven increases in fire frequency may increasingly offset the air-quality benefits provided by forests during non-disturbance periods.

Finally, CFD simulations in Portugal demonstrated that urban trees modify pollutant dispersion by altering wind flow. In Lisbon, vegetation increased domain-average CO concentrations by 12% under non-aligned wind conditions, whereas in Aveiro, aligned winds and canopy structures enhanced ventilation and reduced concentrations by 16%. Inclusion of vegetation improved model performance and compliance with EU air-quality modeling standards [113].

Integrated Synthesis

Across scales and disturbance regimes, forests influence air pollution through four primary pathways:

(1) Direct pollutant removal via deposition and bioaccumulation [87,88,95];

(2) Enhancement of chemical transformation and atmospheric deposition [59,108];

(3) Modification of airflow and pollutant dispersion [88,130];

(4) Pollutant generation during forest and peat fires [126,127,128,129].

These pathways operate simultaneously but with strong context dependence, shaped by vegetation structure, spatial configuration, meteorology, and disturbance regimes. Consequently, forest dynamics can either mitigate or exacerbate air pollution. Effective air-quality management therefore requires integrated strategies that combine vegetation planning, landscape design, fire-risk reduction, and atmospheric modeling to fully harness the regulatory potential of forests while minimizing unintended impacts.

3.2.6. Influence of Different Types of Air Pollution on Forest Dynamics

Particulate Matter and Aerosols

Airborne particulate pollution, including coarse and fine particles, strongly modulates forest microclimates, vegetation functioning, and carbon balance. Numerical simulations have demonstrated that vegetation structure plays a central role in modifying dust dispersion from transportation corridors. Using a Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) modelling framework with PM10 and PM75 as passive scalars, Benes [83] quantified the performance of 49 coniferous and deciduous forest configurations. Differences in forest type, density, height, and width influenced turbulence, deposition efficiency, and pollutant retention. Coniferous and deciduous stands exhibited contrasting capacities for pollutant interception, emphasizing the importance of forest design for pollution mitigation.

Structural traits—such as canopy density and leaf morphology—emerge as critical determinants of mitigation efficiency, suggesting that targeted forest design along transport corridors can substantially enhance air-quality benefits. This highlights a key pattern across studies: forest structure mediates pollutant exposure as strongly as pollutant load itself.

Atmospheric aerosols also exert substantial radiative forcing effects on forest carbon exchange. In semideciduous tropical forests of Mato Grosso, reduced incoming solar irradiance (relative irradiance: f = 1.10–0.67) was associated with decreased net ecosystem exchange (NEE), whereas higher aerosol optical depth (AOD > 1.25, f < 0.5) increased NEE by 25–110% due to enhancement of diffuse photosynthetically active radiation. Aerosols originating mainly from biomass burning also cooled canopy temperatures by 3–4 °C and reduced vapor pressure deficit by 2–3 hPa, ultimately altering CO2 flux behaviour [131].

This apparent contradiction underscores the nonlinear and context-dependent nature of aerosol impacts. Moderate aerosol loading constrains photosynthesis via light limitation, while heavy aerosol loads can enhance diffuse radiation and partially offset thermal and vapor-pressure stress. Together, these results indicate that aerosols can either suppress or stimulate forest carbon uptake depending on background climate, aerosol composition, and canopy structure.

Acidic Deposition and Sulfur/Nitrogen Pollution

Moderate sulfate and reactive nitrogen deposition significantly affected physiological processes in Norway spruce forests of the Bohemian Forest despite a lack of visible growth decline. A multi-decadal dendrochronological analysis revealed a 1.88‰ decrease in carbon isotope discrimination (Δ13C), driven primarily by changes in stomatal conductance rather than photosynthetic capacity. Concurrent increases in intrinsic water-use efficiency (iWUE) occurred without corresponding increases in biomass increment. The decoupling between Δ13C and growth during pollution peaks suggests stomatal-mediated physiological stress as the dominant mechanism [73].

Trees appear to maintain structural growth while operating under constrained gas exchange, masking pollution impacts when assessments rely solely on growth metrics. Isotopic indicators thus provide critical insights into sub-lethal stress mechanisms induced by chronic deposition.

Carbon Dioxide (CO2) and Carbon Cycling

Rising atmospheric CO2 concentrations exert complex, site-dependent influences on tree growth and water-use efficiency. In the Miyun Reservoir Basin near Beijing, tree-ring analyses indicated that CO2 was the primary driver of basal area increment (BAI), accounting for up to 92% of variation in Pinus tabuliformis and 74% in Larix gmelinii at remote sites. However, this influence was lower near urban centers, where nitrogen deposition increasingly limited growth. iWUE rose steadily across sites and species, though quadratic relationships revealed diminishing carbon sequestration benefits once water stress intensified and stomatal conductance decreased [77].

These findings emphasize that CO2 fertilization effects are strongly constrained by co-occurring stressors, particularly water limitation and nutrient imbalance. Increased iWUE does not necessarily translate into proportional biomass gains, reinforcing the idea that physiological efficiency gains may coincide with ecological limitations.

At broader scales, CO2 emissions in China were found to be asymmetrically influenced by cereal crop production, energy use, forestry production, and economic growth. Positive shocks to crop production increased emissions in the long term, whereas forestry production had no significant influence. These findings underscore the importance of renewable energy transition for achieving carbon neutrality [132].

Together, these site-level and national-scale results indicate that while forests respond to rising CO2, their capacity to offset emissions is embedded within broader socioeconomic systems, limiting the effectiveness of forest-based mitigation alone.

Carbon Monoxide (CO)

CO pollution patterns strongly align with urbanization and seasonal dynamics. In the Abuja Municipal Area Council (Nigeria), satellite-derived CO concentrations peaked during dry seasons and in densely populated districts. Vegetation indices revealed significant stress in urban vegetation, though the observed positive correlation between CO and the Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI) (r = 0.695) was attributed to seasonal vegetation cycles rather than CO-related benefits. Machine learning approaches, including Random Forest modelling, improved prediction accuracy and highlighted nonlinear CO–vegetation relationships [133].

This case illustrates the risk of misinterpreting remote-sensing correlations in urban environments. Vegetation indices may reflect phenology rather than pollutant responses, underscoring the need for integrative modelling approaches to disentangle pollution effects from seasonal dynamics.

Negative Air Ions (NAIs)

Forest ecosystems act as natural sources of negative air ions, which mitigate air pollution and provide health benefits. Long-term monitoring shows strong seasonal and diurnal patterns in NAI production. In subtropical broad-leaved forests, NAI concentrations reached WHO-defined clean-air thresholds, peaking in summer and during midday hours. Air temperature and PM2.5 were identified as key environmental regulators, and a predictive model incorporating temperature, humidity, wind speed, and particulate matter explained NAI variability [134].

Extending these insights, machine-learning analysis of long-term forest observations demonstrated that vegetation photosynthetic capacity—quantified using solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence (SIF)—significantly explains spatiotemporal NAI patterns. Vegetation exerted greater influence in spring and summer, while environmental drivers dominated in autumn and winter. Temperature and radiation were the most influential variables depending on season [135].

Further, net ecosystem productivity (NEP) was shown to be a robust indicator of NAI variation in Quercus variabilis forests. Under high PAR conditions, NEP tracked NAI dynamics more closely than PAR itself (R2 = 0.458 vs. 0.367), supporting NEP as a reliable proxy for NAI production at the ecosystem scale [72].

Collectively, these studies reveal a consistent pattern: NAI dynamics are tightly coupled to ecosystem metabolism, linking atmospheric chemistry directly to forest carbon fluxes. This positions NAIs as an integrative indicator of forest functional state rather than a purely atmospheric phenomenon.

Tropospheric Ozone (O3)

Tropospheric ozone continues to rise globally, posing major stress to forest vegetation. Continuous field measurements in subtropical evergreen forests demonstrated that canopy solar-induced fluorescence (SIF) decreases sharply when O3 exceeds 60 ppb, with differing seasonal thresholds (dry season: 75 ppb; wet season: 45 ppb). High ozone levels disrupted the typical linear SIF–GPP relationship, with physiological processes being more vulnerable than radiative or structural components. These findings highlight SIF as an effective indicator of O3 stress [136].

Long-standing methodological challenges remain in extrapolating seedling-based ozone experiments to mature trees. Larger trees typically exhibit lower stomatal conductance—and thus lower ozone uptake—than seedlings, although exceptions occur (e.g., Quercus rubra). Differences in avoidance, compensation, defense, and repair capacities complicate scaling ozone sensitivity across life stages. Consistent methodologies and long-term datasets are needed to improve predictions of forest-level impacts [137].

A broader review emphasizes that risk assessment frameworks still rely heavily on the AOT40 exposure concept rather than flux-based metrics that account for actual physiological uptake. The complexity of ozone behaviour, its interaction with climate and biotic stressors, and limited species-specific flux models hinder the development of robust risk indices [138].

Organ-Specific Responses and Nitrogen Interactions

Experimental exposure of poplar species to elevated ozone revealed substantial reductions in fine-root biomass, surpassing losses in leaf biomass. Leaf litter chemistry shifted toward more recalcitrant components (increased lignin, tannins, and C:N ratios), suggesting delayed decomposition and altered nutrient cycling. Fine-root chemistry was comparatively stable under ozone stress. Nitrogen additions did not meaningfully mitigate ozone effects on either organ, indicating limited potential of N fertilization to counteract O3-induced functional changes [81].

These results highlight a recurring theme: belowground processes may be more sensitive to pollution than aboveground indicators, with cascading effects on nutrient cycling and soil carbon dynamics.

Combined O3 and CO2 Effects

Atmospheric enrichment of both CO2 and O3 produces complex interactions in forest chemistry. At the Aspen FACE facility, elevated CO2 increased condensed tannins and fibre in aspen leaves, whereas O3 reduced nitrogen content and increased structural carbon compounds. In co-occurring treatments, CO2 mitigated many O3-induced chemical changes. Birch exhibited weaker responses to both gases compared to aspen. These shifts in foliar traits have potential consequences for herbivory, nutrient cycling, and successional trajectories [80].

A study in California (USA) using i-Tree Eco model to analyze the air quality benefits of different tree species found that the Turkey oak (Quercus laevis) was the most effective for improving overall air quality, particularly in removing ozone (O3). The effects of existing public trees were found to be comparatively minor when compared to the potential of targeted new plantings. This highlights the importance of species selection in urban forest management for improved environmental and public health outcomes [139].

Together, these studies indicate that species-specific traits strongly mediate both pollutant damage and mitigation capacity, reinforcing the need for functional trait–based forest management.

Biogenic Volatile Organic Compounds (BVOCs) and Secondary Organic Aerosols (SOAs)