Abstract

Acacia melanoxylon R.Br. demonstrates strong biological nitrogen–fixation capacity and favourable economic returns, making it a promising candidate for the development of subtropical forestry in South Asia. It is a fast–growing leguminous tree species widely promoted for cultivation in China, and it is also one of the ideal tree species for improving soil fertility in forest lands. What are the synergistic mechanisms between A. melanoxylon-Eucalyptus stands and pure Eucalyptus spp.? Current theories regarding A. melanoxylon–Eucalyptus systems remain relatively fragmented due to the lack of effective silvicultural measures, resistance studies, and comprehensive ecological–economic benefit evaluations. The absence of an integrated analytical framework for holistic research on A. melanoxylon–Eucalyptus systems makes it difficult to summarise and comprehensively analyse their growth and development, thereby limiting the optimisation and widespread application of their models. This study employed CiteSpace bibliometric analysis and qualitative methods to explore ideal tree species combination patterns, elucidate their intrinsic eco–economic synergistic mechanisms, and reasonably reveal their collaborative potential. This study systematically reviewed silvicultural management, stress physiology, ecological security, and economic policy using the Chinese and English literature published from 2010 to 2025. The narrative synthesis results indicated that strip intercropping (7:3) is widely documented as an effective model for creating vertical niche complementarity, whereby canopy light and thermal utilisation by A. melanoxylon species improve subsoil nutrient cycling by enhancing stand structure. A conceptual full–cycle economic assessment framework was proposed to measure carbon sequestration and timber premiums. Correspondingly, this conversion of implicit ecological services into explicit market values acted as a critical tool for decision–making in assessing benefit. A three–dimensional “cultivation strategy–physiological ecology–value assessment” assessment framework was established. This framework demonstrated how to move from wanting to maximise the output of an individual component to maximising the value of the whole system. It theorised and provided guidance on resolving the complementary conflict between “ecology–economy” in the management of sustainable multifunctional plantations.

1. Introduction

Originating in tropical and subtropical regions, Acacia melanoxylon R.Br. has attracted significant attention for its exceptional biological characteristics [1,2]. A. melanoxylon is a light–demanding, fast–growing species with biological nitrogen–fixation capabilities and the ability to produce high–quality heartwood; it achieves high economic yields while maintaining ecological integrity [3]. Moreover, when conflicts arise between the pressure to maximise timber production and sustainability requirements, introducing such multifunctional tree species becomes not only essential but also an effective means to promote the transition of plantation management from single–purpose production to a genuinely sustainable model [4,5]. Although intensive management of pure Eucalyptus spp. plantations can yield rapid economic benefits, they inevitably significantly impair the land’s long–term productivity. Issues such as soil acidification, nutrient depletion, and declining microbial community diversity caused by successive gradient rotation cycles have led to the continuous degradation of plantation ecosystems, drawing strong attention from the forestry industry [6]. To overcome the persistent ecological degradation of forest lands, current forestry production and management are increasingly shifting towards intercropping systems [7]. This demonstrates that selecting A. melanoxylon as an adaptive timber model for forestry development will vigorously promote the transition to an ecologically and economically coordinated multi–objective management approach for the industry [8].

The practical application of the A. melanoxylon-Eucalyptus mixed system in production has been hindered by the fragmented understanding of the interaction mechanisms, despite its promising theoretical prospects. The key remaining questions are the following: What is the essence of interspecific competition? How can ecological benefits be monetised? And how to transition from single–tree optimisation to intensive mixed systems? The main issue lies in the lack of a unified theoretical foundation. The existing literature is disjointed, often focusing on isolated factors such as stress–resistant physiology or soil improvement in a fragmented manner, failing to provide a comprehensive understanding of this system. Belowground ecological processes—particularly nutrient transfer and Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi (AMF) networks—remain a “black box” in current research [9]. In economics, carbon sinks and timber premiums are neither different stages of the same value realisation nor two opposed value dimensions, but rather complementary elements within the complete life–cycle value chain [10]. However, their current connection remains notably weak. Additionally, research on forest management optimisation methods lacks systematic comprehensiveness, failing to situate stand management within the objective of maintaining long–term intrinsic stability.

This study employed bibliometric mapping and qualitative analysis to address the missing framework for predicting eco–economic coordination effects across environmental gradients, achieving the following three conceptual integrations: firstly, elucidating the intrinsic mechanism of vertical niche complementarity, with a focus on analysing the resistance–enhancing mechanisms under the 7:3 strip intercropping model; secondly, constructing a comprehensive economic model that internalizes implicit ecosystem services by converting them into integral components of the financial model and externalizing ecological benefits into explicit market prices to aid decision–making; and thirdly, integrating the above elements to establish a three–dimensional theoretical framework encompassing “cultivation strategies–physiological ecology–value assessment” to guide the transition from traditional single–function forest production to a sustainable multifunctional paradigm.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Methods

This review was conducted following the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta–Analyses) guidelines to ensure transparency and reproducibility [11]. Data were retrieved from the following two major databases: the Web of Science (WoS) Core Collection (Clarivate, Philadelphia, PA, USA) (representing the international literature) and CNKI (China National Knowledge Infrastructure, Tsinghua Tongfang Knowledge Network Technology, Beijing, China) (China National Knowledge Infrastructure, representing the Chinese literature). The search time frame covered the period from 1 January 2010, to 31 December 2025.

To ensure comprehensive coverage, we employed the following specific Boolean logic search strings based on the keywords mentioned in the introduction:

WoS Core Collection: The search query was constructed as follows: TS = (“Acacia melanoxylon” OR “Blackwood”) AND TS = (“Eucalyptus”) AND TS = (“Ecology” OR “Economy” OR “Benefit” OR “Intercropping”). Document types were limited to “Article” and “Review”.

CNKI Database: An advanced search was performed using the following: Subject = “Blackwood Acacia” (Acacia melanoxylon) AND Subject = “Eucalyptus” AND Subject = (“Ecological benefits” OR “Economic benefits” OR “Mixed plantation”). Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria: A rigorous screening process was applied. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) peer–reviewed journal articles; (2) studies focusing on the interaction, mixed planting, or comparative analysis of A. melanoxylon and Eucalyptus; (3) publications providing empirical data on silviculture, physiology, ecology, or economic evaluation. The exclusion criteria included the following: (1) conference abstracts, editorials, and letters; (2) studies purely on chemical extraction without ecological context; (3) duplicates and non–English/Chinese articles. Ultimately, 220 valid Chinese journal articles were selected from 13,484 initial records, and 261 valid English papers were included from 20,239 initial records after deduplication and subject filtering.

Bibliometric analysis was performed using CiteSpace software version 6.4.R1 (Chaomei Chen, Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA, USA) with the following specific parameter settings: time slicing was set to 1 year (2010–2025), node selection utilised the g–index (k = 25), and network pruning was applied using the Pathfinder algorithm. CiteSpace was employed to map the knowledge structure, utilizing indicators such as Modularity Q and Weighted Mean Silhouette S to evaluate clustering validity, and Betweenness Centrality to assess node influence (previously referred to as the partnership index). Burst Detection was used to identify emerging frontiers. To distinguish between software–derived patterns and mechanistic interpretations, a qualitative narrative synthesis was conducted on the high–impact papers identified within the clusters. This step specifically extracted physiological mechanisms and management strategies (e.g., the 7:3 intercropping ratio) that bibliometric indicators alone could not explain [12].

2.2. Research Trends and Thematic Evolution

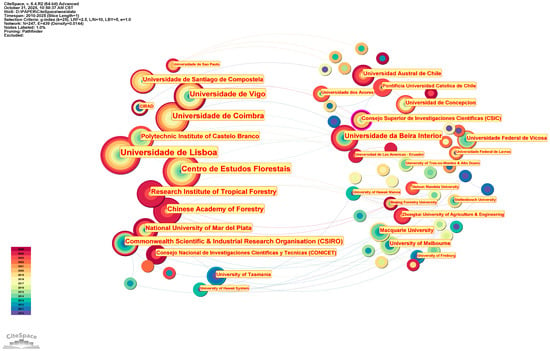

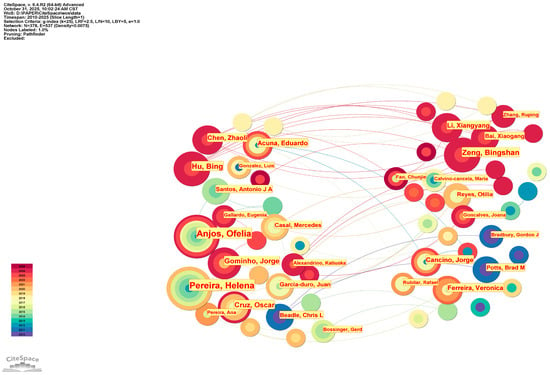

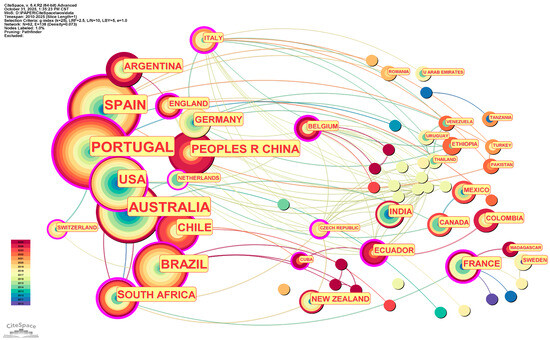

The research on the eco–economic synergistic effect between A. melanoxylon and Eucalyptus spanned two phases from 2010 to 2025. The first development phase was from 2010 to 2019, where both Chinese and English annual publications did not exceed 20. Chinese publications surged after 2020, peaking at 32 in 2024. While English publications remained volatile, with minor fluctuations, annual publications were generally stable, reaching an overall peak of 23 in 2018. This trend in development shows that the world is taking serious note of the synergistic effect of mixed–species plantations, especially with the increased activity in practice–oriented research publications in China after 2020. The indexed rates currently indicate a slight drop in 2025, reflecting partial–year data accumulation rather than a decrease in research output, and the field maintains an upward trend, as per the assessment. The co–authorship network of the Chinese literature comprises 480 nodes and 1165 edges, with a network density of 0.0101. The core authors are Zeng Bingshan (11 papers) and Qiu Zhenfei (9 papers). In comparison, the most productive institutions include the Guangxi State–owned Liuwan Forest Farm (11 papers) and the Forestry College of Guangxi University (7 papers). This forms a clustering structure with a distinct regional concentration, with relatively few cross–provincial collaborations. The density of the English literature collaboration network is 0.0075 (the number of edges between nodes is significantly fewer than the maximum possible edges that could be formed in the network). Anjos (11 publications in total), Ofelia (11 publications in total), and Pereira (11 publications in total) occupy the core positions. The institutional collaboration pattern exhibits strong “geographical centralisation”, with the Universidade de Lisboa, for instance, dominating research in the relevant field among Portuguese–speaking countries (24 publications in total). Portugal and Australia, which have the highest research output, both have a substantial number of internationally co–authored papers, as shown in the national collaboration network. While China has published numerous academic achievements, most are characterised as “domestically focused” rather than actively engaging in collaborative production through exchange. International collaborations related to Chinese research remain notably weak (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Global author collaboration network for Acacia melanoxylon and Eucalyptus: the ecological–economic synergistic effect research.

Figure 2.

Global institutional collaboration network for Acacia melanoxylon and Eucalyptus: the ecological–economic synergistic effect research.

Figure 3.

Country collaboration network for Acacia melanoxylon and Eucalyptus: the ecological–economic synergistic effect research.

2.3. Research Hotspots and Thematic Evolution

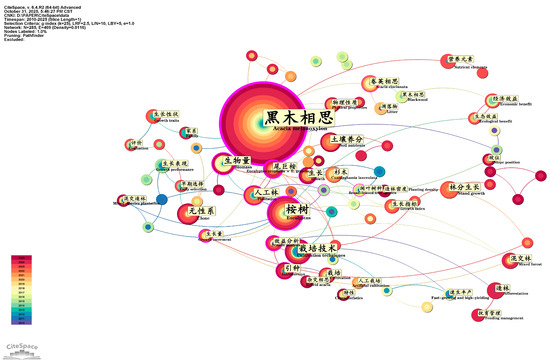

Keyword co–occurrence network analysis revealed major differences in themes between the Chinese and English literature. The Chinese studies focus more on tree breeding and cultivation management, while the English language studies focus more on invasion ecology and responses to global change. The most frequently occurring keywords in the Chinese literature were “Acacia melanoxylon”, “Eucalyptus”, and “cultivation techniques”. This shows that the major areas of research involve tree breeding, growth characteristics, and plantation techniques (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Keyword co–occurrence map for the Chinese literature on Acacia melanoxylon and Eucalyptus: the ecological–economic synergistic effect research.

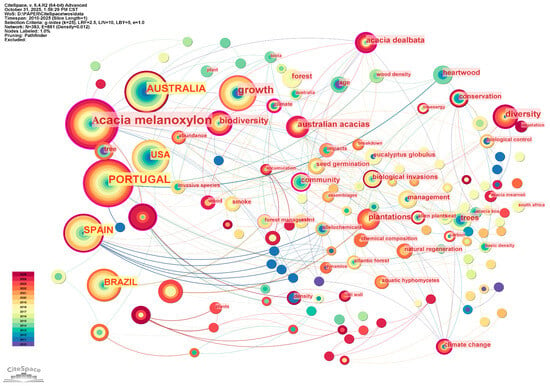

The English literature, in contrast, focuses on keywords such as Acacia dealbata, invasive species, and biodiversity, reflecting concerns with invasion ecology, climate change, and wood properties. The continued use of keywords such as climate change and biodiversity indicates ongoing research into the ecological response to global change (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Keyword co–occurrence map for the English literature on Acacia melanoxylon and Eucalyptus: the ecological–economic synergistic effect research.

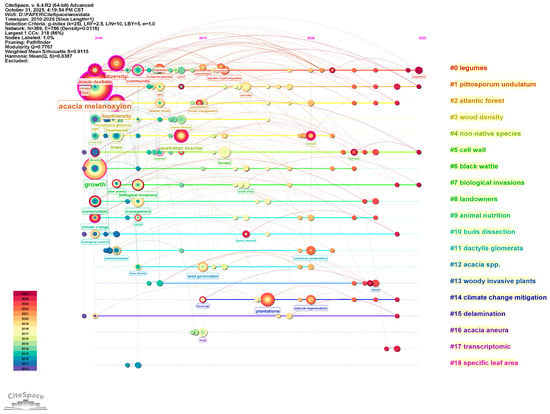

Cluster analysis of keywords related to A. melanoxylon and Eucalyptus reveals the temporal evolution of the relevant research paradigm, from basic trait description before 2015 to integrated research based on the eco–economic synergistic effect, after 2020. The cluster analysis (Modularity Q = 0.7767, Weighted Mean Silhouette S = 0.9115) identified the following four principal groups: Forest Ecology and Environmental Effects (#0,#6), Invasion Ecology (#4,#7), Wood Science (#3,#15), and Physiological and Molecular Mechanisms (#5,#17). The graphic of the timeline reveals that the earlier research, namely, before 2015, focused mainly on descriptions of fundamental traits, and evidence of an evolutionary development towards an integrated eco–economic paradigm becomes obvious after 2020 (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Timeline view of keyword cluster analysis for Acacia melanoxylon and Eucalyptus: the ecological–economic synergistic effect research.

The clusters, taken together, recognise that A. melanoxylon and Eucalyptus are important trees with research and eco–economic value. Both species are showing a united front by affirming the concept of a synergistic mechanism, given their growth characteristics and ecological impacts. The hotspot analysis and thematic evolution discussed above provide a solid basis for the detailed studies in the following sections on cultivation management and stress resistance mechanisms. To provide a robust summary of the identified trends and to support the subsequent discussion, the major thematic clusters and their characteristics are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of major thematic clusters and their evolutionary characteristics in Acacia melanoxylon and Eucalyptus research (2010–2025).

3. Synergistic Cultivation Strategies and Resource Complementarity Mechanisms

3.1. Inter–Species Fertilisation Synergistic Effect and Nutrient Optimisation

Existing experimental data indicate significant differences in the nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) requirements between A. melanoxylon and Eucalyptus, as well as variations in optimal fertilisation timing [13]. However, current research has focused only on individual tree species, neglecting interspecific interactions. This leads to a lack of comprehensive, systematic fertilisation protocols, resulting in underutilising the advantages of mixed forest systems and substantial room for improvement in nutrient–use efficiency.

Specifically, A. melanoxylon is highly sensitive to phosphorus. Studies show that the application of organic–inorganic compound fertilisers effectively improves their rooting and photosynthetic rates, whereas ordinary compound fertilisers are ineffective because of their low phosphorus activation efficiency [14]. In contrast, Eucalyptus requires nitrogen for rapid growth, but excessive N input can lead to soil acidification, jeopardising long–term land productivity [6]. Consequently, the management of Eucalyptus requires the precise regulation of nitrogen inputs, while the cultivation of A. melanoxylon requires phosphorus activation and the improvement of organic matter. Notably, the biological nitrogen–fixing capacity of A. melanoxylon may act as a nutrient subsidy for Eucalyptus, thereby reducing dependence on chemical fertilisers and pollution [15].

Regarding application timing, A. melanoxylon seedlings responded well to basal fertiliser, as their nodulation system established rapidly. Wang et al. observed that in mixed plantation studies, Eucalyptus is more nutrient efficient at the top–dressing stage [16]. This efficiency is owing to interspecific facilitation by A. melanoxylon, whose nitrogen fixation and mycorrhizal networks increase the bioavailability of soil nutrients [9]. We therefore suggest a differentiated approach that prioritises the continuous supply of basal fertiliser for A. melanoxylon, while employing resource complementarity to reinforce top–dressing management for Eucalyptus during its peak growth stages [17]. Targeted, phased fertilisation strategies tailored to particular species characteristics can serve both high nutrient–use efficiency and ecological sustainability goals.

3.2. Optimising Ecological Niche Complementary Planting Patterns

Related research on A. melanoxylon has attracted increasing attention as scholars have gained a deeper understanding of the limitations of pure Eucalyptus plantations and the rising costs of monoculture seedlings in pure Eucalyptus plantations or in mixed plantations of Myrica rubra and Eucalyptus [18]. Regarding the principles for constructing mixed–species systems, it is commonly believed that they follow the ecological niche complementarity theory among tree species, resulting in a “layering effect [7]”. In intercropping plots, a significant resource–use gradient is observed between Eucalyptus and A. melanoxylon, outlined as follows: Eucalyptus is a competitive, fast–growing species that achieves rapid height growth and quickly forms the upper layer of the “layering effect”, which shades the lower layers [19]. In contrast, A. melanoxylon is an adaptive species with a well–developed root system that can extend deeper into the soil to fixate and utilise nutrients, resulting in a typical “layering effect” that reduces intraspecific or interspecific competition [20]. Additionally, Wu et al. found that the crown development of A. melanoxylon exhibits the characteristic of avoiding Eucalyptus trees [21].

The stability of mixed forests fundamentally depends on the configuration of tree species. According to Chen’s systematic research on Castanopsis hystrix, a 7:3 ratio yields the maximum structural toughness [22]. Validated by field trials at the Guangxi Sanmenjiang State–Owned Forest Farm, this ratio has also proven effective for A. melanoxylon and Eucalyptus mixtures, serving as a site–specific reference for optimising vertical structure. Meanwhile, under strip intercropping conditions, Eucalyptus trees in rows adjacent to A. melanoxylon show better growth than those within the same strip, indicating positive facilitation [23]. However, this synergistic effect is conditional as follows: positive interactions occur only when the Eucalyptus proportion is below 70%. When the Eucalyptus ratio reaches or exceeds 70%, inhibitory effects emerge among Eucalyptus trees, manifesting as a state of detrimental competition. During this period, it is necessary to properly manage the proportion and rational allocation of Eucalyptus trees in this strip intercropping operation model, ensuring a state of “moderate competition–dynamic balance”. The dominant tree species must not be allowed to encroach upon the living space of the disadvantaged tree species [24].

Current expert consensus emphasises optimising the configuration of A. melanoxylon-Eucalyptus systems as a process involving a multi–level synergistic effect. The spatial arrangement in strip intercropping establishes regulated gradients of light, heat, and nutrients [25]. This configuration often proves more effective than block mixing in achieving niche complementarity and efficient resource utilisation [26]. Within this framework, the proportion of A. melanoxylon should be dynamically adjusted according to site–specific conditions—for instance, an increased proportion on barren sites to leverage its soil–ameliorating capacity [27]. Consequently, the optimal system configuration is highly context dependent.

The key below–ground ecological processes responsible for this reorganisation are interspecific resource exchange and mutualism associated with common mycorrhizal networks (CMNs), with the latter being identified as a key catalysing driver of such systemic efficiencies. An understanding of spatial configuration, the ratio design of different plant functional types, and below–ground interactions can provide useful insights for developing theories to explain carbon–water coupling mechanisms [28]. However, a systematic explanation of the evolutionary laws governing stability under long–term continuous rotation, along with the specific regulation of below–ground processes, is lacking. Further cross–scale ecological observations and process–based model simulations are required to ascertain this understanding.

3.3. Resource Conservation and Value Sharing

A. melanoxylon and Eucalyptus have gained increasing prominence in international timber, biofuel, and ecosystem service markets as representative fast–growing, high–yield plantation tree species [5]. Scholars have conducted research across various dimensions, comprehensively discussing the chemical components of these two materials, including cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, and extractives [29]. These studies provide data to support the development of pulp and paper products, the production of biofuels, and the design of high–value chemicals [30,31].

A core economic rationale for this mixed system lies in the marked value differentiation between the two species. Eucalyptus is cultivated as a high–volume, low–cost feedstock for the pulp and panel industries [32]. A. melanoxylon, however, is valued as a premium hardwood for niche applications in furniture and interior finishes [33]. Intercropping capitalises on this complementarity, generating a diversified product output that single–species or natural forests cannot easily replicate [34]. By doing so, it synergistically combines the rapid biomass production of one with the high–value timber of the other, thereby optimising the integrated economic and functional benefits of the land use [35].

Studies have demonstrated that A. melanoxylon pulp can meet the standards of coniferous pulp, and A. melanoxylon can serve as a supplement to Eucalyptus [31]. Currently, Eucalyptus residues are receiving increasing attention as raw materials for bio–oil production [36]. However, beyond its original single–output characteristic, another feature of this system lies in forming a virtuous cycle within the ecosystem through interactions with the surrounding environment. By leveraging A. melanoxylon’s nitrogen–fixing capacity to enhance Eucalyptus nutrition, it alters Eucalyptus wood properties. To fully utilise this advantage, the “whole–tree utilisation” strategy (employing everything from bark to seed pods) has been adopted, significantly improving resource utilisation per tree [37]. This approach meets both the demand for product quantity and the need to reduce environmental impact.

This mixed system’s performance is underpinned by complementary material properties and by the distinct capacities of each species to withstand stress and acquire nutrients. Crucially, system dynamics are governed by biological processes—notably, A. melanoxylon’s nitrogen fixation and facilitative rhizosphere interactions—rather than by mere additive effects. These processes are key determinants of overall yield and timber grade. Thus, future efforts to quantify the system’s synergistic effects must further clarify how its resource allocation efficiency interrelates with, and potentially enhances, the stress resistance strategies of its component species.

4. Synergistic Stress Resistance Mechanisms and Nutrient Coupling

4.1. Stress Physiology and System Synergy

Breeding programs targeting stress resistance in A. melanoxylon have selected superior families and clones adapted to specific adversities [38]. This has provided a satisfactory germplasm base for monoculture plantations [39]. Nonetheless, the present research paradigm of “individual optimisation” does not align with the needed “systemic synergistic effect”.

Modern genetic breeding studies are based on quantitative genetics, where the primary aim is to select superior individuals for specific site conditions [40]. The combination of molecular markers with field trials has identified specific genotypes that exhibit vigorous growth under nutrient–deficient or moisture–deficient conditions [38]. For instance, in the poor–quality soils of the Guangxi’s Sanmenjiang Forest Farm, A. melanoxylon stands have demonstrated superior performance (average DBH > 16 cm), ameliorating the microenvironment by adding humus. This shows the potential of stress–resistant genotypes with high eco–economic value and environmental plasticity.

Family tests and clonal tests have provided encouraging results. SR17 is one of the fast–growing, adaptable clones selected from multi–site, multi–year trials. Family tests also reveal significant genetic potential [41]. Theoretically, however, current breeding objectives primarily focus on growth traits. The “Eco–Economic Synergy Framework” suggests a shift towards traits for ecological functioning. This implies selecting germplasm with canopy or root architecture complementary to Eucalyptus. Although studies on leaf traits and wood properties exist, they mainly focus on material identification or utilisation rather than systematically assessing ecological function within a mixed system [42]. Genomic research provides avenues to understand nitrogen–fixation pathways but has yet to bridge the theoretical gap between molecular bases and mixed–forest productivity.

Field trials are largely conducted using Randomised Block Designs (RBDs) with monoculture performance as the objective, which is unsuitable for evaluating interspecific interactions [43]. While genetic mapping and molecular technologies increase precision in breeding, they remain focused on individual traits. Several empirical studies provide indirect evidence for synergistic enhancement—for example, improved drought resistance via rhizobia inoculation and the selection of provenances exhibiting differential cold tolerance [44]. Despite these findings, there is no integration into a common framework, and the actual contribution to system productivity needs to be tested quantitatively.

4.2. Nutrient Utilisation and Stress Interactions

The main aim of research on A. melanoxylon’s stress resilience is to explain how the plant body, at the molecular and physiological levels, responds to N and P limitations. These mechanisms directly control how a system acquires nutrients from the external environment and, in theory, justify precision nutrient management for mixed systems.

A series of studies by Qiu et al. revealed that, under phosphorus deficiency, A. melanoxylon’s capacity to withstand physiological stress is supported by the establishment of an equilibrium between free radicals and protective antioxidants, as evidenced by favourable growth [45]. Most importantly, it can retrieve (remobilise) scarce phosphorus from various organs to maintain unblemished physiological functioning. Bai et al. identified the best phosphorus concentrations for clonal propagation [46]. Also, He et al. and Chen et al. specified the threshold ranges and stress effects for nitrogen and boron, respectively [15,47,48]. Based on all these findings, scientists will be able to develop guidelines for differential fertilisation in mixed plantations.

The efficient utilisation strategies that emerge under stress, such as phosphorus remobilisation and biological nitrogen fixation, provide the physiological foundation for A. melanoxylon, acting as a “nutrient contributor”. This mechanism indirectly stimulates Eucalyptus growth, thereby synergistically improving the entire system [49]. Consequently, a profound dissection of the nutrient stress response in A. melanoxylon is vital for decoding below–ground synergistic interactions. It is also helpful in optimising nutrient management to realise the targeted eco–economic synergistic effect.

4.3. Drought Adaptation and Water Regulation

Many drought resistance mechanisms have already been explored, but the findings regarding A. melanoxylon are quite surprising and remain relatively fragmented, with only isolated phenomena and scattered pieces of knowledge. There remains a significant gap, outlined as follows: we have not yet pieced together these fragmented findings into a comprehensive theory of “synergistic drought resistance”, a crucial component that is missing. In other words, we need to transition from studying individual forests to mixed forests.

Plants employ various strategies to cope with water shortages. Research by Chen et al. and Zhang et al. demonstrates that tree species have evolved distinct strategies to regulate water use and partition biomass to mitigate drought stress [21]. Certain species have been shown to allocate disproportionately more resources to the roots to enhance water–uptake efficiency [50]. In contrast, mechanisms aimed at modulating leaf water potential and organ hydraulic properties have been more frequently highlighted to maintain turgor [51]. Wujeska–Klause et al. used simulated heatwaves to show that Acacia species with different ecological strategies (A. aneura vs. A. melanoxylon) differ in their antioxidant responses, highlighting the importance of the redox system in responding to combined climate extremes [52].

Physiological mechanisms are merely explanations, not prerequisites for prediction. The true key lies in changes across different scales as follows: phenotypic traits that can enhance individual competitiveness to some extent, such as the secretion of allelochemicals or high water–use efficiency, are merely outcomes of the trade–offs, which may lead to alternative effects at broader community levels [53]. To avoid adverse consequences, it is essential to develop new assessment methods capable of effectively predicting ecological risks, while also providing a critical foundation for ensuring environmental security.

5. Ecological Security Risks and Synergistic Regulation

5.1. Allelopathy and Ecological Risks

The competition between two or more species resulting from toxic substances is called allelopathy. It is often proposed as a competitive mechanism in Acacia–Eucalyptus interactions. Various laboratory tests have identified a wide range of poisonous substances produced by these species. However, current knowledge is largely derived from bioassays performed under simplified conditions. As a result, uncertainty exists regarding their real impact and mode of action in actual field situations.

Extracts from these species can inhibit seed germination and seedling growth, as shown in in vitro experiments. For example, Hussain et al. [54] used high–performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) to extract phenolic and flavonoid compounds from the flowers and leaves of A. melanoxylon, demonstrating their inhibitory effects on the growth and photosynthesis of Lactuca sativa (lettuce). Likewise, Riveiro et al. found significant inhibition by Eucalyptus spp. in a comparative analysis of seven invasive species [55].

A critical assessment of these findings is nevertheless essential. The evidence base is dominated by reductive in vitro experiments, which raises significant questions about its relevance to complex field environments. Key abiotic and biotic factors—such as microbial activity, soil chemistry, and rainfall—likely modulate allelochemical efficacy in nature. Additionally, standard Phyto assays employing sensitive model species may not accurately predict the behaviour of co–evolved native plant communities. Consequently, while new studies suggest allelopathic potential in A. melanoxylon, definitive evidence for its ecological role in mediating competition or facilitating invasion in mixed systems remains lacking. It must be sought through targeted field studies [56].

5.2. Invasive Ecological Processes and Multi–Scale Effects

Research in invasion ecology has shown that Acacia and Eucalyptus overcome environmental barriers through “species–microbe” symbiotic complexes [57]. This discovery impacts biodiversity and important ecosystem processes. These results highlight that their ecological effects exhibit multi–scale, multi–process, and context–dependent features. The current challenge is to integrate these multidimensional impacts into a universal risk assessment framework.

Acacia species that have invaded New Zealand and South Africa were commonly “co–introduced” with rhizobia from their native ranges, according to Warrington et al., thereby ensuring effective establishment [58]. This “holobiont” view (treating the host and its microbes as a single unit) has greatly advanced our understanding of invasion. Birnbaum and colleagues, on the other hand, found no significant differences between an invasive and a native plant species, even though both were closely related within the same family [59].

The recorded changes in native plant diversity loss are unstable or variable, fluctuating significantly across severity levels depending on invasion intensity and landscape patterns [60]. One scenario is hindered regeneration of native seedlings due to intensified invasion, as in high–density A. melanoxylon forests [61]. Another scenario shows that animal responses also vary case by case, with outcomes not being a binary negative effect. The understory vegetation structure determines their ultimate fate, as simply removing monocultures or seedling stands may deplete arthropod populations but could provide refuge for certain avian functional groups [62,63]. The same holds for trees, whether in terms of their impact on species community dynamics or their structural influence on ecosystems—such as depleting groundwater levels through excessive transpiration–induced evaporation or reconstructing nutrient cycles by reshaping the food web structure of aquatic microorganisms via litter deposition [36,64].

Understanding the environmental impacts of A. melanoxylon and the awareness of its invasion risks, along with those of Eucalyptus, provides boundary constraints and a value–judgment basis for eco–economic assessments. Ecological insights aimed at minimising environmental hazards and maximising ecosystem services—based on a multi–scale understanding of A. melanoxylon’s ecological effects and an appreciation of its and Eucalyptus’ invasion risks—should be incorporated into broader management systems and policy frameworks. Furthermore, a comprehensive trade–off analysis is required to shift from purely profit–driven approaches to a development pathway that balances ecological and economic considerations, ensuring both environmental security and financial viability.

6. Model–Policy Synergy and Innovation–Driven Development

6.1. Development of Management Models and Value Reinvention

Plantation management models have begun to transition away from pure timber Faustmann structures towards modified models that incorporate the value of non–market attributes (of trees), such as carbon sinks [65]. Notably, existing models’ approaches remain, by and large, “additive” economic assessments. They fail to endogenize ecological processes in the financial analysis, thereby shifting the focus to Sustainable Forest Management (SFM) and the Bioeconomy [66].

The Faustmann model has governed the classical paradigm, in which LEV (Land Expectation Value) at the optimum rotation age is maximised. But this approach is very reductive, ignoring important non–market values such as water conservation and biodiversity [67]. The work of Xue et al. is a significant extension, as it adds carbon sequestration values using the modified Faustmann–Hartman model [10]. However, this type of extension is additive and does not endogenize ecological processes through economics.

Strong evidence of a synergistic effect between A. melanoxylon and Eucalyptus has been shown by studies. Xie conducted a dynamic economic analysis that situated A. melanoxylon’s financial and economic benefits within the regional financial evaluation [35]. The projections for A. melanoxylon exceeded those for Eucalyptus, despite Eucalyptus’s faster growth rate. Moreover, it confirmed that composite Eucalyptus management models yield higher net revenue than monocultures [8].

The impact of site characteristics and the density of a single species on growth has been examined in various studies on growth management [68]. This forms the biological basis of production. Although Forrester et al. discussed interspecific interactions in their research on thinning in mixed forests, they primarily focused on timber yield [28].

Some studies have shown that monoculture Eucalyptus stands may be environmentally detrimental compared to mixed stands [69]. Wang et al.’s remote sensing analysis showed a lower Ecosystem Service Value (ESV) in Eucalyptus plantations. Furthermore, Wang et al. indicated that continuous in situ rotation poses an ecological risk that can be quantified using Life-Cycle Assessment (LCA) [16]. These assessments of ecology, however, remain largely uncoordinated with economic assessments. A significant gap, therefore, exists.

6.2. Policy–Driven Mechanisms and Pathway Optimisation

The Eucalyptus management policy has long been caught in the dilemma of “economic priority” versus “ecological protection”. The A. melanoxylon–Eucalyptus synergistic effect model is widely regarded as a potential solution to this predicament. The A. melanoxylon–Eucalyptus synergistic effect model represents one perspective whereby rapid growth and high yield can help ensure timber supply and thereby drive development [5]. In contrast, the opposing view emphasises environmental impacts, such as soil and water loss, and advocates for ecological priorities [69]. A systematic review by Malkamaki et al. on large–scale afforestation found that it may have negative impacts on local communities [70]. Although the mixed management of A. melanoxylon and Eucalyptus can balance these trade–offs to some extent, its “synergistic effects” have not been clearly explained or quantitatively evaluated. Therefore, it is not a truly meaningful concept for constructing theoretical consensus in the context of policy practice.

Establishing an “Ecological–Economic Synergy Framework” is necessary to shift the focus from deciding whether to plant or not to how to build a more robust management system, thereby achieving coordinated, optimised development between the two. This approach aims to maximise the economic benefits derived from ecosystem services and the ecological value created by economic activities. Starting with its synergistic mechanisms (nitrogen fixation–mediated burden reduction, drought prevention, and moisture retention), it provides a theoretical explanation for the “1 + 1 > 2” effect, meaning that integrating different levels or elements through this method can yield greater, more comprehensive benefits. In essence, this approach links ecological mechanisms with economic performance, serving as a key solution to the current “Eucalyptus dilemma” and a vital tool for innovating breakthrough models and improving policies.

7. Conclusions and Prospects

This study systematically examined the Chinese and English literature from 2010 to 2025 through a combined bibliometric and qualitative approach and elucidated the eco–economic synergistic effect between Acacia melanoxylon and Eucalyptus. The main findings are as follows:

- (1)

- Elucidation of multi–level synergistic mechanisms: Interspecific coordination is driven by vertical niche complementarity. Eucalyptus occupies the canopy to intercept light resources, while Acacia melanoxylon maximises underground nutrient dynamics through a deep root structure and biological nitrogen fixation. Strip intercropping at a 7:3 ratio was confirmed as an effective mode for optimising stand structure and enhancing systemic resilience. The mixed system exhibits superior timber quality and soil functionality compared to monocultures, demonstrating the lowest environmental maintenance costs.

- (2)

- Full–cycle eco–economic assessment: We conducted a full–cycle evaluation by converting the value of nitrogen fixation into fertiliser cost savings to evaluate eco–economic benefits.

- (3)

- Integration of a three–dimensional analytical framework: We constructed a “Cultivation Strategy–Physio–ecology–Value Assessment” analytical framework. Through closed–loop resource design, this framework can effectively reduce production costs while actively enriching soil and biodiversity, serving as a theoretical tool in the transition towards multi–functional plantation management. Although these synergistic effects have been systematically dissected, the following limitations remain: the key mechanisms of below–ground ecological processes are not well understood, long–term monitoring data are scarce, and eco–economic evaluation standards diverge. Thus, future research should focus on the following directions: macro–scale and long–term monitoring, establishing large–scale ecological monitoring networks spanning more than 10 years, in conjunction with remote sensing technology. It is crucial to assess the responses of mixed systems to climate change (e.g., droughts and heatwaves) and carbon–water coupling processes. Moving from observational correlation to mechanistic prediction requires opening the “black box” of rhizosphere processes. This can be achieved by leveraging techniques like gene editing and isotope tracing to map microbial interaction networks and metabolite fluxes. Establishing a robust empirical basis for models also requires the high–precision measurement of key parameters, particularly the in situ efficiency of biological nitrogen fixation. At the application level, integrating the eco–economic synergistic effect framework with forest growth models (e.g., the Faustmann model) into a Decision Support System (DSS) is essential. Such integration will enable the dynamic optimisation and region–specific adaptive configuration of mixed–species planting patterns.

The “Eco–Economic Synergy” framework developed in this study presents a coherent strategy with significant theoretical and practical implications. It transcends conventional trade–off analyses by not only quantifying the liabilities of continuous monocropping but also demonstrating how scientifically designed species mixtures can reconcile productivity and ecological goals. Thus, the study underscores a pivotal shift in plantation forestry, offering the necessary evidence and conceptual tools to transition from an era of “Eco–Economic Trade–offs” to one of “Synergistic Enhancement”.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: H.G. and L.W.; Methodology: H.G.; Software: H.G.; Validation: H.G.; Formal analysis: H.G.; Investigation: H.G.; Resources: X.S., H.G.; Data curation: H.G.; Writing—original draft: H.G.; Writing—review and editing: L.W., H.W. and H.G.; Visualization: H.G.; Supervision: L.W.; Project administration: L.W., H.W. and X.S.; Funding acquisition: L.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the University–Enterprise Joint Research Project of Central South University of Forestry and Technology, grant number LDKY202301.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available within the article. Further data requests can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Authors Xiaojie Sun and Hong Wei are employed by the company Guangxi Luding Forestry Group Co., Ltd. The paper reflects the views of the scientists and not the company. The funder and the company had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of the data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Richardson, D.M.; Binggeli, P.; Botella, C. Australian Acacia Species in Africa. In Wattles: Australian Acacia Species Around the World; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2023; pp. 181–200. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, A.; Midgley, S.; Bush, D.; Cunningham, P.; Rinaudo, A. Global uses of Australian acacias–recent trends and prospects. Divers. Distrib. 2011, 17, 837–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, R.; Xie, Y.; Luo, J.; Wang, H.; Midgley, S. A tale of two genera: Exotic Eucalyptus and Acacia species in China. 2. Plantation resource development. Int. For. Rev. 2020, 22, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huong, V.D.; Nambiar, E.S.; Quang, L.T.; Mendham, D.S.; Dung, P.T. Improving productivity and sustainability of successive rotations of Acacia auriculiformis plantations in South Vietnam. South. For. J. For. Sci. 2015, 77, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubbage, F.; Koesbandana, S.; Mac Donagh, P.; Rubilar, R.; Balmelli, G.; Olmos, V.M.; De La Torre, R.; Murara, M.; Hoeflich, V.A.; Kotze, H.; et al. Global timber investments, wood costs, regulation, and risk. Biomass Bioenergy 2010, 34, 1667–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Wen, Y.; Zhang, H. Principal component analysis of soil physical and chemical properties in successive Eucalyptus plantation. Bull. Soil Water Conserv. 2010, 30, 101–105. [Google Scholar]

- Paula, R.R.; de Oliveira, I.R.; Gonçalves, J.L.M.; de Vicente Ferraz, A. Why mixed forest plantation? In Mixed Plantations of Eucalyptus and Leguminous Trees: Soil, Microbiology and Ecosystem Services; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.W.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, X. Construction of evaluation system on comprehensive benefit of management model of Eucalyptus plantation in Guangxi. J. West China For. Sci. 2013, 42, 96–99. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Hu, F.; Ma, L. Phosphate-solubilizing bacteria from safflower rhizosphere and their effect on seedling growth. Open Life Sci. 2019, 14, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, B.; Tian, G. Analysis of comprehensive benefits and influencing factors based on the combined economic value of carbon sequestration and timber benefits. J. Nanjing For. Univ. 2021, 45, 205–212. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.T.; Lee, B.Z.; Zhu, Q.H.; Han, X.; Chen, K. Document keyword extraction based on semantic hierarchical graph model. Scientometrics 2023, 128, 2623–2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pottier, P.; Lagisz, M.; Burke, S.; Drobniak, S.M.; Downing, P.A.; Macartney, E.L.; Martinig, A.R.; Mizuno, A.; Morrison, K.; Pollo, P.; et al. Title, abstract and keywords: A practical guide to maximize the visibility and impact of academic papers. Proc. R. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 2024, 291, 20241222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halomoan, S.S.T. Effect of fertilization on the growth and biomass of Acacia mangium and Eucalyptus hybrid (E. grandis x E. pellita). J. Trop. Soils 2015, 20, 157–166. [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva, R.M.L.; Hakamada, R.E.; Bazani, J.H.; Otto, M.S.G.; Stape, J.L. Fertilization response, light use, and growth efficiency in Eucalyptus plantations across soil and climate gradients in Brazil. Forests 2016, 7, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Bai, X.; He, Q.; Hu, B.; Zeng, B.; Lu, Z. Comprehensive evaluation in different genotypes of Acacia melanoxylon under nitrogen deficiency stress. J. Cent. South Univ. For. Technol. 2023, 43, 47–59. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Du, A.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, W.; Zhang, J. Factors limiting the growth of eucalyptus and the characteristics of growth and water use under water and fertilizer management in the dry season of Leizhou Peninsula, China. Agronomy 2019, 9, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Jacobs, D.F.; Sloan, J.L.; Xue, L.; Li, Y.; Chu, S. Split fertilizer application affects growth, biomass allocation, and fertilizer uptake efficiency of hybrid Eucalyptus. New For. 2013, 44, 703–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.-P.; Xu, J.-M.; Lu, H.-F.; Li, G.-Y.; Fan, C.-J.; Liang, B.-Z.; Zhang, L. Transformation of Eucalyptus urophylla × Eucalyptus grandis clone plantation into mixed-species forest using precious tree species. For. Res. 2022, 35, 10–19. [Google Scholar]

- Viera, M.; Schumacher, M.V.; Liberalesso, E. Growth and yield in monospecific and mixed stands of Eucalyptus urograndis and Acacia mearnsii. Pesqui. Agropecu. Trop. 2011, 41, 415–421. [Google Scholar]

- Laclau, J.-P.; Nouvellon, Y.; Reine, C.; Gonçalves, J.L.d.M.; Krushe, A.V.; Jourdan, C.; le Maire, G.; Bouillet, J.-P. Mixing Eucalyptus and Acacia trees leads to fine root over-yielding and vertical segregation between species. Oecologia 2013, 172, 903–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, F.; Bao, W.; Li, F.; Wu, N. Effects of drought stress and N supply on the growth, biomass partitioning and water-use efficiency of Sophora davidii seedlings. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2008, 63, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, F. Impact of Tree Species Mixture on Microbial Diversity and Community Structure in Soil Aggregates of Castanopsis hystrix Plantations. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Liu, N.; Ren, H.; Wang, J. Facilitation by two exotic Acacia: Acacia auriculiformis and Acacia mangium as nurse plants in South China. For. Ecol. Manag. 2009, 257, 1786–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, J.; Cheng, S.; Tigabu, M.; Ma, X.; Wu, P.; Li, M. Growth rate and leaf functional traits of four broad-leaved species underplanted in Chinese fir plantations with different tree density levels. Forests 2022, 13, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amazonas, N.T.; Forrester, D.I.; Silva, C.C.; Almeida, D.R.A.; Rodrigues, R.R.; Brancalion, P.H.S. High diversity mixed plantations of Eucalyptus and native trees: An interface between production and restoration for the tropics. For. Ecol. Manag. 2018, 417, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sein, C.C.; Mitlöhner, R. Acacia mangium Willd: Ecology and Silviculture in Vietnam; CIFOR: Bogor, Indonesia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cabreira, G.V.; Silva, E.V.; Pereira, M.G.; Paula, T.R.; Cabreira, W.V. Root development and growth of mixed stands of Eucalyptus urograndis and Acacia mangium under different types of soil tillage. Floresta 2021, 51, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester, D.I.; Baker, T.G. Growth responses to thinning and pruning in Eucalyptus globulus, Eucalyptus nitens, and Eucalyptus grandis plantations in southeastern Australia. Can. J. For. Res. 2012, 42, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemetova, C.; Ribeiro, H.; Fabião, A.; Gominho, J. Towards sustainable valorisation of Acacia melanoxylon biomass: Characterization of mature and juvenile plant tissues. Environ. Res. 2020, 191, 110090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozkan, S.; Sousa, H.; Gonçalves, D.; Puna, J.; Carvalho, A.; Bordado, J.; dos Santos, R.G.; Gomes, J. Unlocking Nature’s Potential: Modelling Acacia melanoxylon as a Renewable Resource for Bio-Oil Production through Thermochemical Liquefaction. Energies 2024, 17, 4899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neiva, D.M.; Godinho, M.C.; Simoes, R.M.S.; Gominho, J. Encouraging Invasive Acacia Control Strategies by Repurposing Their Wood Biomass Waste for Pulp and Paper Production. Forests 2024, 15, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, L.S.; Chen, L.W.; Antov, P.; Kristak, L.; Tahir, P.M. Engineering Wood Products from Eucalyptus spp. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 2022, 8000780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridglall, P.A.; Laing, M.; Morris, A.; Burgdorf, R. A review of the factors affecting bark quality of black wattle (Acacia mearnsii De Wild.) in South Africa. South. For. J. For. Sci. 2025, 87, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A.; Tu, D.; Zhu, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Wei, W.; Hu, C.; Liu, X. Study on machining properties and surface coating properties of heat-treated densified poplar wood. Wood Res. 2022, 67, 1032–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuong, T.; Chinh, T.T.Q.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, Y. Economic performance of forest plantations in Vietnam: Eucalyptus, Acacia mangium, and Manglietia conifera. Forests 2020, 11, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juan-Ovejero, R.; Reis, F.; da Silva, P.M.; Marchante, E.; Garcia, F.; Dias, M.C.; Covelo, F.; da Silva, A.A.; Freitas, H.; Sousa, J.P.; et al. Acacia invasion triggers cascading effects above- and belowground in fragmented forests. Neobiota 2025, 100, 345–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, L.M.; Reis, M.; Mourao, I.; Coutinho, J. Use of Acacia Waste Compost as an Alternative Component for Horticultural Substrates. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2015, 46, 1814–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, S.-N.; Chen, L.-B.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, W.-H.; Ding, G.-C.; Cao, G.-Q.; Ye, L.-T.; He, S.-B.; Shen, D.-Y.; Yan, Q. Genotype by environment interaction for growth traits of families of Acacia melanoxylon based on BLUP and GGE biplot. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1656136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury, G.J.; Beadle, C.L.; Potts, B.M. Genetic control in the survival, growth and form of Acacia melanoxylon. New For. 2010, 39, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes Goncalves, J.L.D.; Alvares, C.A.; Higa, A.R.; Silva, L.D.; Alfenas, A.C.; Stahl, J.; Ferraz, S.F.d.B.; Lima, W.d.P.; Brancalion, P.H.S.; Hubner, A.; et al. Integrating genetic and silvicultural strategies to minimize abiotic and biotic constraints in Brazilian eucalypt plantations. For. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 301, 6–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, F.M.B.; Novais, T.d.N.O.; Jacovine, L.A.G.; Bezerra, E.B.; Lopes, R.B.d.C.; de Holanda, J.S.; Reyna, E.F.; Fearnside, P.M. Wood Basic Density in Large Trees: Impacts on Biomass Estimates in the Southwestern Brazilian Amazon. Forests 2024, 15, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.A.; Curran, T.J.; Sullivan, J.J. Variation in understorey floristic composition, regeneration, and fire hazard under Acacia invaded forest canopy in New Zealand. For. Ecol. Manag. 2024, 554, 121671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaw, T.Y.; Amran, A.; Teoh, A. Factors influencing ESG performance: A bibliometric analysis, systematic literature review, and future research directions. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 448, 141430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fikri-Benbrahim, K.; Chraibi, M.; Lebrazi, S.; Moumni, M.; Ismaili, M. Phenotypic and Genotypic Diversity and Symbiotic Effectiveness of Rhizobia Isolated from Acacia sp Grown in Morocco. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2017, 19, 201–216. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, Z.; Fan, C.; Zeng, B. The Physiological and Biochemical Responses of Acaciamelanoxylon Under Phosphorus Deficiency. J. Southwest For. Univ. 2020, 40, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Bai, X.; Li, X.; Zeng, B.; Hu, B. Effects of Boron on the Growth and Development of Acacia melanoxylon R. Br. seedlings. J. For. Sci. 2023, 36, 181–191. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Zeng, B.; Ding, W.; Shen, L.; Chen, M.; Hu, B.; Li, X. Multi-omics analysis reveals changes in lignin metabolism and hormonal regulation in Acacia melanoxylon stems under low boron stress. Plant Stress 2025, 18, 101058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouillet, J.-P.; Laclau, J.-P.; Gonçalves, J.L.d.M.; Voigtlaender, M.; Gava, J.L.; Leite, F.P.; Hakamada, R.; Mareschal, L.; Mabiala, A.; Tardy, F.; et al. Eucalyptus and Acacia tree growth over entire rotation in single-and mixed-species plantations across five sites in Brazil and Congo. For. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 301, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Chen, L.; Jiang, L.; Zhu, J.; Chen, J.; Huang, Q.; Liu, J.; Xu, D.; He, Z. C: N: P stoichiometry of plant, litter and soil along an elevational gradient in subtropical forests of China. Forests 2022, 13, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarnaschelli, A.; Garau, A.; Lemcoff, J. Water stress and afforestation: A contribution to ameliorate forest seedling performance during the establishment. Water Stress 2012, 2, 74–110. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez, E.; Vega, J.A.; Pérez-Gorostiaga, P.; Fonturbel, T.; Fernández, C. Evaluation of sap flow density of Acacia melanoxylon R. Br. (blackwood) trees in overstocked stands in north-western Iberian Peninsula. Eur. J. For. Res. 2010, 129, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wujeska-Klause, A.; Bossinger, G.; Tausz, M. Seedlings of two Acacia species from contrasting habitats show different photoprotective and antioxidative responses to drought and heatwaves. Ann. For. Sci. 2015, 72, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, C.J.; Manea, A.; Moles, A.T.; Murray, B.R.; Leishman, M.R. Differences in life-cycle stage components between native and introduced ranges of five woody Fabaceae species. Austral Ecol. 2017, 42, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.I.; El-Sheikh, M.A.; Reigosa, M.J. Allelopathic potential of aqueous extract from Acacia melanoxylon R. Br. on Lactuca sativa. Plants 2020, 9, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riveiro, S.F.; Cruz, O.; Reyes, O. Are the invasive Acacia melanoxylon and Eucalyptus globulus drivers of other species invasion? Testing their allelochemical effects on germination. New For. 2024, 55, 751–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arán, D.; García-Duro, J.; Cruz, O.; Casal, M.; Reyes, O. Understanding biological characteristics of Acacia melanoxylon in relation to fire to implement control measurements. Ann. For. Sci. 2017, 74, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crous, P.; Shivas, R.; Quaedvlieg, W.; van der Bank, M.; Zhang, Y.; Summerell, B.; Guarro, J.; Wingfield, M.; Wood, A.; Alfenas, A.; et al. Fungal Planet description sheets: 214–280. Persoonia 2014, 32, 184–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warrington, S.; Ellis, A.; Novoa, A.; Wandrag, E.M.; Hulme, P.E.; Duncan, R.P.; Valentine, A.; Le Roux, J.J. Cointroductions of Australian acacias and their rhizobial mutualists in the Southern Hemisphere. J. Biogeogr. 2019, 46, 1519–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birnbaum, C.; Bissett, A.; Thrall, P.H.; Leishman, M.R. Invasive legumes encounter similar soil fungal communities in their non-native and native ranges in Australia. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 76, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wraage, C.P.; Sottile, G.D.; Honaine, M.F.; Meretta, P.E.; Pérez, C.V. Contribution to the study of vegetation and its relationship with geodiversity in rangeland environments located at Los Padres and La Brava hills of the southeastern Tandilia System (Buenos Aires, Argentina). Bol. Soc. Argent. Bot. 2025, 60, 49–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraaij, T.; Baard, J.A.; Grobler, B.A.; Miles, B. Effects of Acacia melanoxylon, an alien tree species to South Africa, on Afrotemperate forest tree sapling composition. South. For.-A J. For. Sci. 2023, 85, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadenas-Madrigal, C.; Mata-Zayas, E.E.; Olivera-Gómez, L.D.; van der Wal, J.C.; Arriaga-Weiss, S.L. Avifauna in commercial agroforestry monocultures in Huimanguillo, Tabasco, Mexico. Rev. Mex. Biodivers. 2023, 94, e944913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, J.; Cordero-Rivera, A.; González, L. Characterizing arthropod communities and trophic diversity in areas invaded by Australian acacias. Arthropod-Plant Interact. 2020, 14, 531–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.; Figueiredo, A.; Ferreira, V. Invasive Acacia Tree Species Affect Instream Litter Decomposition Through Changes in Water Nitrogen Concentration and Litter Characteristics. Microb. Ecol. 2021, 82, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miettinen, J.; Ollikainen, M. Economics of forest bioeconomy: New results. Can. J. For. Res. 2022, 52, 426–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deegen, P.; Wang, S.; Kant, S.; Hostettler, M. New frontiers of forest economics, IV: Entrepreneurship in forestry: Innovation, uncertainty and profit. For. Policy Econ. 2025, 170, 103380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molin, P.G. Dynamic Modeling of Native Vegetation in the Piracicaba River Basin and Its Effects on Ecosystem Services. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, H.; Xu, J.; Li, G.; Liu, W. Site classification of Eucalyptus urophylla × Eucalyptus grandis plantations in China. Forests 2020, 11, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayle, G. Ecological and social impacts of eucalyptus tree plantation on the environment. J. Biodivers. Conserv. Bioresour. Manag. 2019, 5, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkamäki, A.; D’aMato, D.; Hogarth, N.J.; Kanninen, M.; Pirard, R.; Toppinen, A.; Zhou, W. A systematic review of the socio-economic impacts of large-scale tree plantations, worldwide. Glob. Environ. Change-Hum. Policy Dimens. 2018, 53, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.