Abstract

Forest cover dynamics strongly influence ecological integrity and resource sustainability, particularly in ecotonal landscapes, where vegetation is highly sensitive to climate variability, long-term climate change, and anthropogenic disturbances. This study examined Forest Land (FL), representing all areas of dense, canopy-forming woody vegetation with forest-like structure, aggregated from SANLC classes, in relation to eight other land cover classes across three periods: 1990–2014, 2014–2022, and 1990–2022. The study used South African National Land Cover datasets and the TerrSet–LiberaGIS Land Change Modeller to quantify changes in magnitude, direction, and source–sink relationships. Analyses included post-classification comparison to determine spatial changes, transition matrices to identify land-cover conversions, and asymmetric gain–loss metrics to reveal sources and sinks of forest change. The result shows that between 1990 and 2014, forests remained marginal and fragmented in the eastern central part of the study area, while shrubland increased from 40.4% to 60.2% at the expense of grasslands, cultivated land, bare land, wetlands, and forest land. From 2014 to 2022, FL regeneration was pronouncedly increased from 2% to 6%, especially along riparian corridors and reservoir margins, coinciding with shrubland decline (99.3%) and grassland recovery (261.2%). Over the entire 1990–2022 period, FL increased from 2.4% to 6% expanding into bare land, cultivated land, grassland, shrubland, and wetlands. Asymmetric analysis indicated that forests acted as a sink during the first period but as a source of ecological resilience in the second and final. These findings demonstrate strong vegetation feedback to hydrological and anthropogenic drivers. Overall, the findings underscore the potential for forest recovery to enhance biodiversity, ecosystem services, carbon storage, and hydrological regulation, while identifying priority areas for riparian conservation and integrated catchment management.

1. Introduction

Forests are among the most vital terrestrial ecosystems, providing a wide array of ecological, hydrological, and socioeconomic services, including carbon sequestration, climate regulation, soil and water conservation, and biodiversity support [1,2]. Globally, they cover nearly one-third of the Earth’s land surface and function as critical carbon sinks, biodiversity reservoirs, and livelihood sources [3,4]. Despite their importance, forest landscapes are undergoing rapid transformation driven by deforestation, fragmentation, and land degradation, primarily linked to agricultural expansion, infrastructure development, and climate variability [5,6]. These pressures are particularly acute in ecotonal and watershed regions, where ecological thresholds are highly sensitive to climatic fluctuations and anthropogenic disturbance [7].

Globally, forests have historically declined due to deforestation driven by population pressure, agricultural expansion, and infrastructure development [8]. However, recent decades reveal encouraging signs of forest recovery supported by sustainable management and afforestation initiatives. Forest areas in Asia have increased continuously since 1990, though expansion has slowed in the past decade, while Europe has shown consistent gains, and more moderate increases have occurred in North and Central America [9]. Between 2010 and 2020, forest growth reached about 1.03 million ha yr−1 in Asia and 470,000 ha yr−1 in Europe [10]. Similarly, land use land cover change (LULCC) assessments indicate strong temporal recovery, following a 21.9% loss between 1993 and 2003, forest cover rebounded by 24.5% (2003–2013) and 6.3% (2013–2023) under large-scale afforestation programs, expanding forest extent by roughly 994 km2 (+30.8%) and enhancing carbon storage despite earlier emissions of ~117,600 tons C yr−1 [11]. However, since 1990, Africa and South America have seen significant declines in forest areas, though the pace of loss has slowed in both regions leading up to 2025 [9]. Currently, about 2 billion ha (≈54%) of global forests are under long-term management plans, though unevenly distributed across regions [12].

Africa is characterized by extensive woodlands, savannas, and tropical rainforests, yet the dynamics of these ecosystems remain poorly understood, particularly in sparsely treed savanna and woodland areas [13]. Continental analyses using remote-sensing-based fractional tree cover from 2000–2020 indicate that Africa’s forest area increased by approximately 3.59 million ha yr−1, with the fastest gains in woodlands (2.28 million ha yr−1), followed by rainforests and savannas [13]. Despite these continental trends, forest recovery is relatively limited: only seven countries recorded net forest gains over the past two decades, with significant growth (>200 km2) in Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia, and Eswatini [14]. Since 2012, forest cover change in Africa has become more localized, with Algeria gaining forest and countries like the DRC, Tanzania, and Angola facing major losses. These shifts are driven by population growth, agriculture, urbanization, and economic development, with most losses concentrated in a few countries and limited, region-specific gains [14]. The integration of sustainable forest management with remote sensing and GIS-based monitoring is increasingly vital for tracking spatiotemporal recovery, improving carbon accounting, and supporting adaptive forest conservation and restoration strategies worldwide.

In sub-Saharan Africa, forests are both indispensable and highly vulnerable to unsustainable land-use practices, including shifting cultivation, rangeland encroachment, and fuelwood extraction [5]. In Southern Africa, forest patches are largely fragmented within savanna–grassland mosaics and concentrated along riparian corridors, where they play a disproportionate role in hydrological regulation, erosion control, and biodiversity conservation [2]. However, these forest landscapes are increasingly shaped by competing socioeconomic and environmental pressures, resulting in asymmetric and often non-linear patterns of loss, regeneration, and transition [1,15,16]. Understanding these dynamics remains challenging, particularly in semi-arid catchments where forest persistence and regeneration pathways are tightly coupled with rainfall variability and land-use intensity [17,18,19].

Remote sensing technologies have become indispensable in monitoring forest dynamics worldwide because of their ability to provide synoptic, consistent, and repeatable observations across large areas and long time spans [11,20,21,22,23,24]. Thus, remote sensing approaches and land-cover change models have been widely applied to quantify forest dynamics, identify transitions between land-cover types, and assess impacts on ecosystem services [20]. In South Africa, remote sensing datasets are widely used for vegetation monitoring, hydrological modeling and conservation planning [25,26,27].

Despite continental and regional trends in forest dynamics, peer-reviewed studies on forest cover change in Africa’s semi-arid ecotonal zones remain scarce, with this gap particularly pronounced in the C5 Secondary Drainage Region of South Africa. Most local research has focused on hydrology and water balance at the quaternary catchment scale (e.g., afforestation impacts on runoff in C52A), rather than comprehensive land-use/land-cover change analyses on secondary catchments that encompass ecotonal areas [28]. Besides, existing studies often rely on coarse land-cover categories, which obscure the fine-scale dynamics of riparian forests [28,29]. In addition, broader catchment-level studies emphasized watershed response parameters rather than detailed multi-decadal forest transitions and their interactions with other land use and land cover classes [30,31,32]. Consequently, systematic, remote sensing-driven time-series capturing forest and vegetation changes are lacking for the C5 region. This knowledge gap limits understanding of the drivers, sinks, sources, and ecosystem-service implications of forest dynamics. Furthermore, little is known about long-term forest trajectories at the secondary catchment scale, particularly regarding asymmetric processes of forest loss, regeneration, and recovery, which are critical for guiding sustainable management and restoration in these ecotonal landscapes. Notably, the asymmetric land-change analysis has been recognized as a robust method for detecting the differential roles of land-cover classes as sources or sinks in landscape transformations [33].

The availability of multi-epoch South African National Land Cover (SANLC) datasets (1990, 2000, 2013/14, 2018, 2020, 2022), derived from Landsat and Sentinel-2 imagery, offers an opportunity to overcome these limitations [34,35,36]. These datasets provide harmonized, nationally consistent land-cover classifications across 73 detailed categories, enabling robust analysis of forest dynamics when aggregated into broader classes suitable for modeling [36,37]. When integrated with spatially explicit tools such as the TerrSet–LiberaGIS Land Change Modeler (LCM), these data allow for a systematic assessment of gains, losses, persistence, and asymmetric trajectories in forest landscapes [38,39]. LCM offers multiple analytical functions, including post-classification comparison to calculate area changes between time periods, transition matrices to identify source–sink dynamics, and asymmetric gain–loss metrics to measure forest loss relative to earlier baselines and forest gain relative to later baselines. The latter approach is particularly important for forests because gains in later years rarely mirror prior losses in terms of spatial extent, ecological quality, or ecosystem functionality. For instance, forest regeneration along riparian corridors may not compensate for the ecological services lost when upland forests are cleared. By distinguishing these directional and non-reciprocal pathways, LCM enables a more nuanced understanding of resilience and degradation trajectories. Asymmetric metrics capture the non-reciprocal nature of forest change, where regeneration seldom fully compensates for prior losses in ecological quality, spatial extent, or ecosystem function. Yet, few studies have systematically applied asymmetric land change analysis to riparian and woody forests in semi-arid catchments. Addressing this gap is critical for understanding resilience and degradation pathways and for informing ecosystem service valuation and catchment management.

The C5 Secondary Drainage Region, covering the Modder and Riet River catchments, represents a semi-arid ecotone with complex vegetation and variable hydrology. Its sensitivity to climatic variability and anthropogenic disturbance makes it an ideal setting for examining forest resilience and transitions under multiple interacting drivers. Asymmetric analysis will assess forests’ roles as ecological sinks or sources under hydrological and human pressures. The objectives of this study were to (i) quantify spatiotemporal Forest cover change across three periods (1990–2014, 2014–2022, 1990–2022) using multi-temporal remote sensing data, (ii) map spatial patterns of forest gain, loss, and stability to identify hotspots of deforestation and regeneration, and (iii) apply Asymmetric Land Change Analysis (ALCA) to assess the magnitude and direction of forest cover changes. Based on these objectives, the following hypotheses were formulated: Forest cover in the C5 watershed has experienced spatiotemporal change between 1990 and 2022, showing spatially heterogeneous patterns of loss and gain. Therefore, this study investigates the transformation of forest landscapes in the C5 secondary drainage region (SDR) of South Africa between 1990 and 2022. By integrating multi-temporal SANLC datasets with the Land Change Modeler and applying asymmetric gain–loss metrics, it provides the first high-resolution, secondary catchment-level assessment of forest dynamics in the study watershed. The findings establish an empirical baseline for hydrological modeling, ecosystem service valuation, and the design of targeted forest conservation and restoration strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Study Area

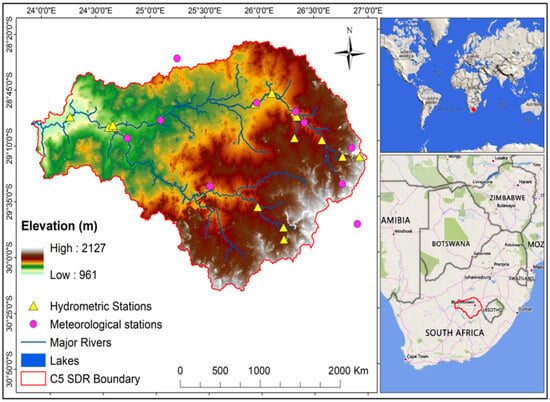

The study area, the C5 SDR, is part of the primary drainage region C and covers approximately 35,570 km2. Geographically, the region extends between approximately 28°–30° S and 24°–26° E (Figure 1). The C5 was delineated using a Digital Elevation Model (DEM) dataset at 30 m spatial resolution. The dataset was downloaded from USGS EarthExplorer [40]. The C5 SDR includes the Riet (C51) and Modder (C52) River systems in central South Africa. These basins are further separated into 23 quaternary catchments, all of which are emptied into the Orange-Vaal River system [41]. Furthermore, the C5 SDR lies in an ecotone that separates the grassland and eastern Nama Karoo biomes [42,43,44].

Figure 1.

Location Map of Study Area.

With shallow stony soils and natural vegetation dominated by drought-tolerant grasses (Themeda triandra, Eragrostis spp.) and dwarf shrubs (Pentzia incana, Eriocephalus spp.), the western and central portions are located in the semi-arid Eastern Nama Karoo (300–500 mm/year) [45]. Woody species are limited to drainage lines, and the eastern portion is in the Grassland biome (>500 mm/year), which supports continuous grass cover dominated by T. triandra, Tristachya leucothrix, and E. curvula [42]. This transitional environment is extremely vulnerable to changes in land use and climate, which can alter the balance of vegetation and have an impact on ecosystem services [46].

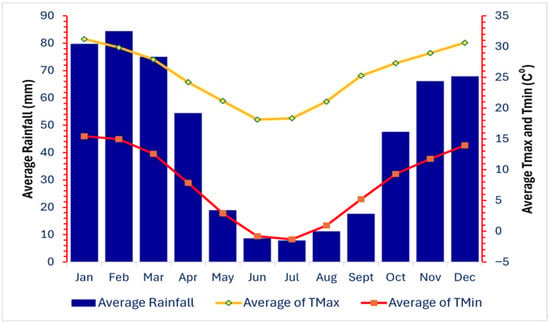

The C5 catchment is characterized by a predominantly semi-arid climate with strong spatial and seasonal variability. The basin-wide average of mean annual precipitation (MAP) is close to 424 mm, with the range varying from about 275 mm in the western low-lying areas to over 686 mm in the eastern uplands [47,48]. In the C5 SDR, the rainfall is very seasonal. It occurs mostly throughout the austral summer months (September–April) with peak intensities in January and February, while the winter months (May–August) are typically dry [47]. Regarding temperature, the basin’s maximum average monthly temperature ranges from 18.1 °C in winter to 31.2 °C in summer. The minimum average monthly temperature ranges between −1.3 °C in winter to 15.4 °C in summer (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Average monthly rainfall (RF), maximum temperature (Tmax), and minimum temperature (Tmin) for the C5 catchment from 1950 to 2020, based on observations from the Glen College Station.

In terms of topography, the region is gently undulating, with slopes varying between 1.7% and 10.3% and elevations ranging from 961 m west to 2127 m east above mean sea level (Figure 1). For climatic study, a network of 223 South African Weather Service (SAWS) daily rainfall stations, 185 of which are located inside and 38 of which are outside the C5 region, offers sufficient spatial coverage [47]. Only a small portion of the operational stations, acquired from SAWS upon request, are displayed in Figure 1.

Hydrologically, South Africa is separated into 148 secondary drainage regions and 22 primary drainage regions [41]. Furthermore, the Riet and Modder rivers form key tributaries of the Vaal River system, with major impoundments including the Krugersdrift and Rustfontein dams that support irrigation and domestic water supply [49].

Socioeconomically, the study area is largely rural, with low population densities and livelihoods primarily reliant on agriculture, while major urban centers include Bloemfontein and Kimberley [50,51].

2.2. Data Sources

The primary data source for this study is the South African National Land Cover (SANLC) datasets, which provide satellite-derived land cover information for the entire country, including the C5 SDR. The datasets were accessed on 5 July 2025 upon request from Environmental Geographic Information Systems (EGISs) and are available at their website https://www.dffe.gov.za/egis (accessed on 5 July 2025).

The 1990 dataset used 30 m Landsat 4 and 5 images acquired between April 1989 and October 1991 [52]. The 2014 dataset employed 30 m Landsat 8 imagery from April 2013 to March 2014 [53]. The 2022 dataset utilized 20 m Sentinel-2 imagery acquired between 1 January 2022 and 31 December 2022 [54]. All datasets integrated multiple acquisition dates and seasons to capture vegetation dynamics and land-cover variability. While only cloud-free scenes (0% cloud cover) were used to ensure temporal consistency, partial cloud-affected regions were corrected by merging with nearby cloud-free acquisitions to minimize spectral inconsistencies. All Landsat 8, 5 and 4 imageries were sourced from the USGS online archive (http://glovis.usgs.gov/).

These datasets are available for the years 1990, 2014, and 2022, and are developed in alignment with the national land cover classification standard (SANS 19144-2). Initially comprising 72 detailed land cover classes for the years 1990 and 2014, and 73 for the year 2022. The datasets were aggregated into nine broader hierarchical land use/cover (LULC) categories, as recommended [37], based on the clear descriptions of the detailed classes to facilitate interpretation, modeling, and analysis [54,55]. The categories include waterbodies (WBs), forested lands (FLs), grassland (GL), wetlands (WLs), cultivated land (C), shrubland (SH), built-up areas (B), bare land (BL), and mines/quarries (MQs) (Table 1). This thematic simplification adheres to the SANLC grouping framework to maintain classification consistency and spatial relevance for environmental analysis [35,36,37].

Table 1.

Grouping of detailed SANLC classes into broader LULCC categories applied in this study.

2.3. Land Use Classification Workflow and Accuracy Validation

The SANLC datasets for 1990, 2014, and 2022 were produced using automated mapping models rather than traditional manual classification methods to systematically process multi-seasonal satellite imagery [42,43]. All land-cover and land-use classes were generated through automated modelling workflows designed to ensure full operational repeatability and enable consistent change detection. The land-cover mapping was implemented using the Computer Automated Land-Cover (CALC) system developed by the Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment (DFFE) [37,56]. All classifications adhere to the nationally gazetted South African land cover standard (SANS 19144-2), consisting of 72 detailed classes for 1990 and 2014, and 73 for 2022, which were harmonized to ensure temporal consistency across the datasets [34,35,36,37].

The classification process involved several key steps. Initial preprocessing included atmospheric correction and mosaicking of Sentinel and Landsat scenes. The core classification was performed using automated mapping approaches, combining rule-based spectral modeling and machine learning algorithms to accurately capture land-cover variability [35].

Validation and accuracy assessment were performed according to rigorous protocols managed via the Department of Forestry, Fisheries, and the Environment’s (DFFE) Environmental Geographic Information Systems (EGIS) platform [34,35,36,37]. Accuracy assessment used a stratified random sampling design, with about 150 samples per class across the LULC classes. Points were placed at class centres and over 50 m from boundaries to reduce edge effects and ensure representative accuracy estimates [53]. Reference datasets were compiled through high-resolution imagery interpretation, authoritative shapefiles, and ground truth data. Confusion matrices were constructed to calculate key accuracy metrics, including Overall Accuracy (OA), User’s Accuracy (UA), Producer’s Accuracy (PA), and the Kappa Coefficient (κ). These combined methodological practices ensure that the SANLC-derived land cover maps utilized in this study are both methodologically sound and thoroughly validated, providing a reliable foundation for subsequent spatiotemporal land cover change analysis [34,36,37].

As a result, the SANLC 2014 dataset achieved an overall accuracy of 82% (90% CI: 81.10%–82.36%), a mean class accuracy of 91.3%, and a Kappa index of 0.803, based on 6415 reference points, with ≥100 samples per class. As the same mapping procedures and image formats were used for both the 1990 and 2014 datasets, the map accuracies determined for 2014 can be used as a reliable indication of the likely mapping accuracies for the 1990 dataset, which was not evaluated due to the paucity of relevant reference data in the same format as that used for the 2014 verifications [43]. The 2022 dataset was validated with 7498 independently interpreted reference points with a minimum of 100 points per class using Sentinel-2, Google Earth, and Street View imagery. The SANLC 2022 classification achieved an overall accuracy of 84.22% (90% CI: 83.67%–84.77%), a mean class accuracy of 83.55%, and a Kappa index of 0.8381, based on 7498 reference samples [42]. All the metadata, including the complete accuracy assessment (per-class accuracy matrix), version, legends, and land cover map reports, including detailed descriptions of LULC classes that are indicated in Table 1, are accessible at https://www.dffe.gov.za/egis, accessed for this study on 5 June 2025.

The land-cover datasets were derived from different satellite imagery, such as Landsat imagery at 30 m for 1990 and 2014, and Sentinel-2 imagery at 20 m for 2022. As a result, the 2022 Sentinel-2 data were resampled using the nearest-neighbor method from 20 m to 30 m to achieve spatial compatibility with the earlier Landsat datasets before conducting change detection. Additionally, to ensure consistency and comparability across the datasets, the classification legend was harmonized and standardized (Table 1).

2.4. Land Use and Land Cover Change Detection Methods

After harmonizing the LULC maps and their legends, a postclassification approach was employed to analyze LULCC. The LULCC detection was conducted using a post-classification comparison approach within the TerrSet LiberaGIS v.20.00 environment, which overlays independently classified land cover maps from different years to detect and quantify pixel-level transitions among land cover classes. The analysis was carried out for three time intervals: 1990–2014, 2014–2022, and 1990–2022. Using the Land Change Modeler (LCM) in TerrSet liberaGIS v.20.00, a comprehensive suite of change metrics was generated, including gross gain, representing the total area a land cover class acquired from other classes; gross loss, indicating the area a class lost to others; and net change, reflecting the overall difference between gains and losses. The rate of change was calculated to assess the temporal pace of these changes, while the percentage net change provided insight into the proportion of total area altered within each class.

where is the percent net change is the area of a class in the base year LULC map and is an area of a class in the later-year LULC map.

where is the annual rate of change in km2, t is the time interval between base and final study years.

where is the percentage area of a class, is the total area and is an area of a class.

An asymmetric change analysis was applied to quantify the directional dynamics of land cover transitions. Unlike simple net change, this method separately considers gains and losses, providing a more nuanced understanding of landscape change. For each land cover class, the percentage of loss was calculated relative to its area in the base year, while the percentage of gain was calculated relative to its area in the final year. This approach allows identification of “source” areas, where a class is expanding, and “sink” areas, where it is declining, revealing spatial and ecological patterns of land cover transformation that a net change metric alone cannot capture (Equations (4) and (5)). It effectively captures the non-reciprocal nature of class transitions, supporting more nuanced interpretations of landscape change for planning and policymaking.

where represents the percentage of area lost for a given land cover class, is the total area lost from that class, and denotes the total area of the land cover class in the base year. Similarly, is the percentage of area gained for the class, is the total area gained by the class, and is the total area of the study region in the later year.

To support a deeper understanding of the underlying processes, class-level contributor analysis was conducted to identify the specific land cover categories contributing to the gain or loss of a target class. For example, when a specific land cover class exhibited a significant increase, the analysis identified the contributing classes from which this gain originated; conversely, for a class undergoing decline, the analysis determined the recipient classes to which its area was converted. This helped to explain not just how much change occurred, but also the sources and sinks of these changes. In addition, transition matrices, spatial trend maps, and change persistence analysis were used to visualize and interpret spatial patterns of stability and transformation across the landscape. Collectively, this integrated change detection framework within TerrSet LiberaGIS enabled a scientifically rigorous assessment of the magnitude, direction, rate, and contributors of LULC change in the study area.

2.5. Spatial Trend of Change (STC) Analysis

The Spatial Trend of Change (STC) analysis was computed using Spatial Trend of Change Tool in TerrSet liberaGIS v.20.00. The STC is a geospatial technique used to visualize the broad directional tendencies of land-use/land-cover dynamics by identifying consistent increases (hotspots) and no change (cold spots) across multiple time periods. Because human-dominated landscapes often exhibit complex and fragmented change patterns, STC applies a best-fit polynomial trend surface to generalize underlying spatial structures that may be obscured in raw transitions. The method operates by coding areas of change as 1 and areas of no change as 0, treating them as quantitative surfaces to derive regional-scale patterns. Although trends up to the 9th order can be computed, higher orders substantially increase processing time and risk overfitting; therefore, following recommended practice, a 3rd-order polynomial surface was used in this study to balance computational efficiency and interpretability [57]. This enables clear visualization of persistent spatial tendencies in both forest expansion and contraction.

3. Results

3.1. Land Cover Transition Dynamics and Conversion Pathways

Land-use/land-cover (LULC) transition matrices for the study period between 1990 and 2014, 2014 and 2022, and the cumulative period between 1990 and 2022 reveal the dynamics of FL across the C5 SDR (For the cumulative period, a Cramer’s V of 0.5184 indicates a strong association between initial and final LULC classes, suggesting that landscape changes were driven by deterministic ecological processes and anthropogenic influences rather than by chance.

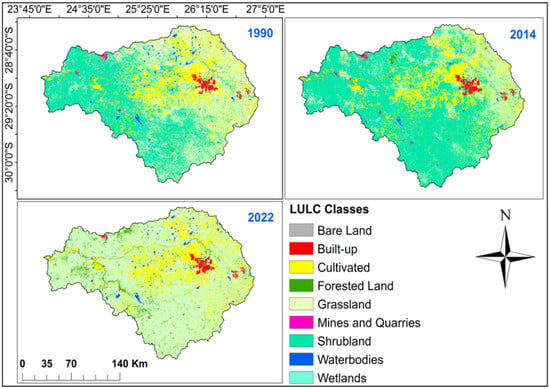

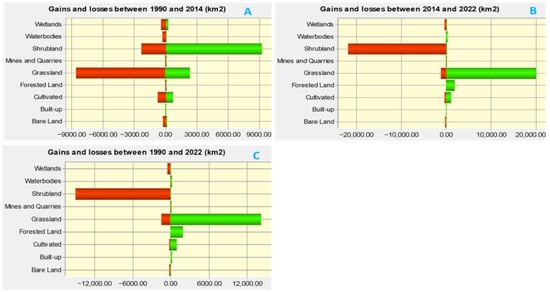

The C5 SDR showed significant land cover dynamics between 1990 and 2022 (Figure 3; Table 2 and Table 3). These dynamics were a result of both natural and human-driven factors. Despite not being a dominating class at first, forested land (FL) underwent significant spatial transitions with respect to other major cover types. This is based on land use and land cover (LULC) classifications derived for 1990, 2014, and 2022.

Figure 3.

LULC Spatial Dynamics in the C5 SDR over the three study periods.

Table 2.

LULC transition matrices for 1990–2014, 2014–2022, and 1990–2022, showing forest gains, losses, and persistence (highlighted in bold and shaded) in km2.

Table 3.

Annual Rate of Change (ARC) and NC of LULC Dynamics in the three study periods of the C5 Catchment of the Riet and Modder Rivers.

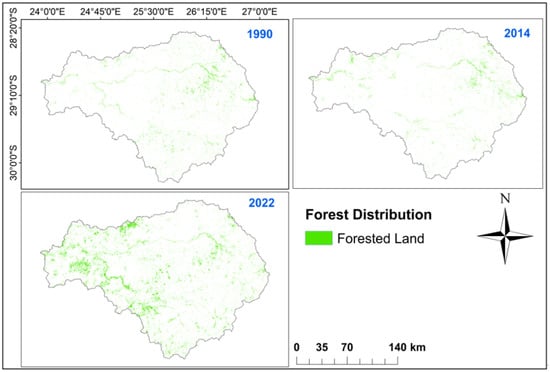

In 1990, GL (38%) and SH (40.4%) made up much of the terrain, while cultivated land made up 14.2% (Table 2). Instead of existing as continuous stands, forested land was spatially limited and appeared as isolated, fragmented patches (Figure 3 and Figure 4). Built-up areas and wetlands were also minor classes, emphasizing the landscape’s natural and largely untouched state at the time.

Figure 4.

Spatial dynamics of forested land in the C5 Catchment for the period 1990–2022, illustrating temporal shifts in forest distribution derived from multi-year land cover analyses.

By 2014, SH expanded to 60%, while GL and C decreased slightly to 20% and 14%, respectively (Table 2). Forested land remained marginal, persisting mainly as scattered patches in the eastern, rugged areas (Figure 3 and Figure 4). The persistence of low forest cover during this period suggests that harvesting and grazing pressures were present.

In 2022, FL exhibited an exceptional and unprecedented expansion, emerging as the most dominant land cover gain across the C5 catchment. The extent of FL markedly 2036.97 km2, which is 5.727% of the total area in 2022 (Table 2).

As illustrated in Figure 4, the spatial extent of forest cover in 1990 and 2014 was predominantly confined to the eastern and east-central sectors of the catchment, reflecting a localized and fragmented distribution pattern. By 2022, however, forest cover exhibited a marked spatial expansion into the western, southwestern, southern, and northwestern zones, with a pronounced concentration along riparian corridors (Figure 4). The spatial distribution of this expansion was strongly associated with riverbanks, streams, and drainage corridors, underscoring the importance of riparian forest regeneration (Figure 3 and Figure 4). This spatiotemporal shift suggests the influence of targeted afforestation and reforestation programs, as well as plantation establishment along riverbanks. The preferential increase in forest cover in riparian areas may further indicate ecosystem restoration initiatives aimed at enhancing riparian buffer zones, improving soil stabilization, and reducing hydrological vulnerability. Such dynamics highlight the growing role of anthropogenically driven land-cover interventions in shaping forest spatial patterns within the catchment.

3.1.1. Temporal Transformation in Forest Dynamics

Between 1990 and 2014, FL experienced a net decline due to higher losses to urban expansion and agriculture than gains from GL and SH, reflecting intensifying land-use pressures. FL decreased from 849 km2 to 712.2 km2, representing a net loss of 137 km2 (16.2%) over 24 years and. a mean annual decline of 5.7 km2 yr−1 (Table 2 and Table 3). As shown in Figure 5A, FL experienced a gain of 452.4 km2, while losses amounted to 589.6 km2. Persistence analysis indicated that 260 km2 of the 1990 FL remained stable, while 589.6 km2 was converted to other land-cover types. Major losses occurred through transitions to GL (278.4 km2), SH (221 km2), C (56 km2) and B (14.2 km2) (Table 2). Conversely, gains of 452.4 km2 arose primarily from regrowth on GL, SH, WL, abandoned croplands, and small-scale urban forestry initiatives. Overall, this period was characterized by net forest reduction driven by anthropogenic pressures.

Figure 5.

Temporal dynamics of forest land showing gains (green) and losses (red) in km2 across three study periods: (A) between 1990 and 2014, (B) between 2014 and 2022 and (C) between 1990 and 2022.

In stark contrast, during the 2014 to 2022 study period, FL exhibited remarkable expansion. Forest area surged from 712 km2 in 2014 to 2037 km2 in 2022 (Table 2). This represents a net gain of 1325 km2 (186%) and an unprecedented mean annual increase of 165.6 km2 yr−1 (Table 2 and Table 3). Persistence analysis revealed that 285 km2 of the original FL remained stable (Table 2). Although only 427.3 km2 of forest land was lost, the total gain of 1753 km2 arose primarily from conversions of GL and SH, highlighting extensive afforestation, natural regeneration, and plantation establishment (Figure 5B; Table 2).

The cumulative analysis for the 1990–2022 period underscores the predominant role of forest expansion across the catchment. Total forest area increased from 849 km2 to 2037 km2, with a net gain of 1188 km2 (140%) at an average annual rate of 37 km2 yr−1 (Table 2 and Table 3). Despite the rapid growth, only 318 km2 of 1990 FL persisted (Table 2). Whereas 1719 km2 emerged from other land-cover types, 531 km2 was lost to other LULC classes (Figure 5C; Table 2). Key sources of this expansion included GL (840 km2), SH (709 km2), C (31 km2), BL (22.45 km2), and WL (97 km2) (Table 2). The strongest spatial gains occurred along riparian corridors in the western, northwestern, southern, and southwestern sectors, likely facilitated by favorable microclimates, regulated hydrology, and reduced anthropogenic pressures.

Taken together, these temporal trends reveal a clear transformation in FL dynamics. The period between 1990 and 2014 was dominated by forest loss due to land-use intensification, whereas the 2014–2022 period experienced extensive forest recovery driven by afforestation, natural regeneration, and structural ecological transitions. These findings highlight the significant role of both ecological processes and human interventions in reshaping the C5 catchment landscape.

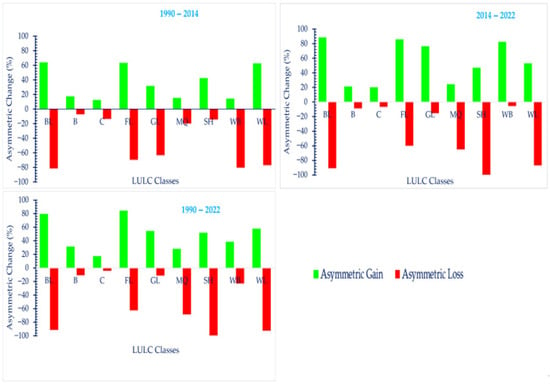

3.1.2. Asymmetric Trajectories of Forest Gain and Loss

The asymmetric analysis of FL dynamics revealed distinct temporal patterns across the three study periods. Between 1990 and 2014, 69.4% of the 1990 FL was lost, while 63.5% of the 2014 FL originated from non-forest classes (Figure 6). This indicates considerable internal turnover, where forest recovery partly compensated for losses but did not fully counterbalance the impacts of anthropogenic disturbance and degradation (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Asymmetric Percent Gains and Losses of Land Use/Cover Classes in the C5 Catchment across the three time periods. The asymmetric percent gains (Up green) are relative to end years, and losses (Down Red) are relative to base years.

During the period between 2014 and 2022, the asymmetry shifted towards strong forest expansion, with 60% of the 2014 FL being lost, yet 86% of the 2022 FL gained from other land uses (Figure 6). This suggests that although losses persisted, they were proportionally outweighed by significant new forest establishment.

Over the long-term span between 1990 and 2022, the asymmetric dynamics are more striking. About 63% of the 1990 FL was lost, while 84.4% of the 2022 FL represents newly established forests (Figure 6). These findings confirm that present-day forests are predominantly recent formations rather than persistent remnants of older stands. Collectively, the asymmetric dynamics underscore that forest systems in the study area are highly dynamic, shaped by cycles of disturbance and regrowth, and highlight the importance of conservation measures aimed at safeguarding both older stands and emerging secondary forests.

3.1.3. Key Contributors to Net Changes in Forest Land

This section examines the primary land-cover transitions driving net changes in FL across the study periods. Understanding these contributors is essential for identifying the sources of forest gains and losses, including the roles of GL, SH, C, BL, WL, and B. Quantifying these transitions provides insights into the ecological processes, anthropogenic activities, and restoration efforts shaping forest dynamics within the C5 catchment.

Between 1990 and 2014, the primary negative contributors to the net change in FL were SH (−98.5 km2), GL (−70.2 km2), C (−26.7 km2), B (−4 km2), and (Figure 7A). This reflects the impacts of agricultural expansion, urban encroachment, and land-use intensification on forest decline. In contrast, WL (40.5 km2), WB (14.6 km2) and BL (10 km2) were positive contributors, indicating limited natural regeneration within wetland areas despite the overall forest loss (Figure 7A).

Figure 7.

Contributions of different LULC classes to net forest change in km2 across the study periods: (A) between 1990 and 2014, (B) between 2014 and 2022 and (C) between 1990 and 2022 highlighting the relative influence of each class on forest expansion and contraction.

In contrast, during the 2014–2022 period, FL experienced substantial positive net changes, with GL (300.7 km2), SH (1065 km2), and C (2 km2), emerging as the major positive contributors (Figure 7B). Notably, there were no significant negative contributors during this period. This indicates that forest recovery was widespread and largely driven by afforestation, natural regeneration, and land-use conversion from previously non-forested areas.

For the cumulative period from 1990 to 2022, the major positive contributors to FL net gain included GL (441 km2), SH (704.7 km2), WL (85.7 km2), and BL (13.7 km2). The negative contributors were WB (−22 km2), C (−26.6 km2), and B (−14.4 km2) (Figure 7C). These results highlight that while early forest losses were primarily associated with anthropogenic pressures, long-term forest expansion has been driven by large-scale ecological recovery and land-use transitions from multiple non-forested classes.

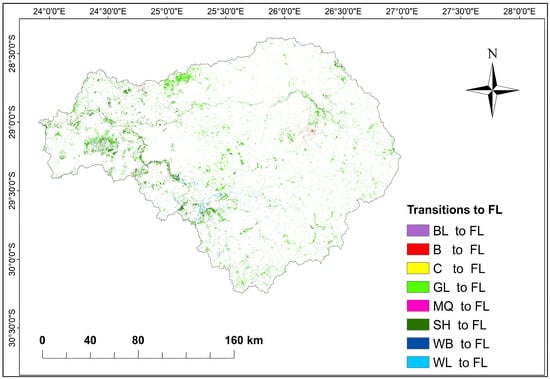

3.1.4. Spatial Distribution of Transitions from Other LULC Classes to Forest

The spatial distribution of transitions from other LULC classes to forest within the C5 SDR between 1990 and 2022 exhibited pronounced spatial heterogeneity (Figure 8). SH was predominantly converted to forest in the western, southwestern, southern, east-central, eastern, and northeastern zones, indicating widespread regeneration across diverse ecological settings. GL transitions to forest were more spatially extensive, occurring in the western, central, southern, south-central, southeastern, eastern, and northwestern sectors. WL contributed to forest expansion in the southwestern, northeastern-central, western, and central areas, reflecting localized hydrological and ecological interactions. BL conversions to forest were observed in the northwestern, western, west-central, and central regions, suggesting reclamation of degraded landscapes. MQ sites demonstrated forest recovery mainly in the northwestern sector. B was converted to forest primarily in the east-central and northwestern zones, with additional pockets in the eastern areas. C transitioned to forest in the central, east-central, and eastern parts of the catchment. These spatially variable transitions underscore the multifaceted pathways of forest regeneration, strongly shaped by biophysical conditions, land-use intensity, and restoration potential within the catchment.

Figure 8.

Spatial distribution of transitions from other LULC classes to forest in the C5 SDR (1990–2022), highlighting areas of forest expansion driven by conversions from other land cover types.

3.1.5. Spatial Pattern of Forest Gain, Persistence, and Loss

Supplementary Figure S1 illustrates the spatial patterns of forest gain, persistence, and loss between 1990 and 2022, complementing the transition dynamics described above. Much of the forest gain was concentrated in the western, west-central, southwestern, southern, northwestern, and eastern zones, broadly overlapping with areas where SH, GL, WL, BL, and C were converted to forest (Figure 8). These gains may be attributed to a combination of natural regeneration processes, ecological restoration of degraded landscapes, and reduced land-use pressure in peripheral zones of the catchment. In contrast, forest losses were largely concentrated in the east-central sector, where conversion to urban and agricultural land dominated. This highlights the significant role of anthropogenic expansion in driving forest decline. Persistent forest areas were mainly found in zones less affected by intensive land conversion, underscoring the importance of favourable biophysical conditions and lower disturbance pressures in maintaining long-term forest stability.

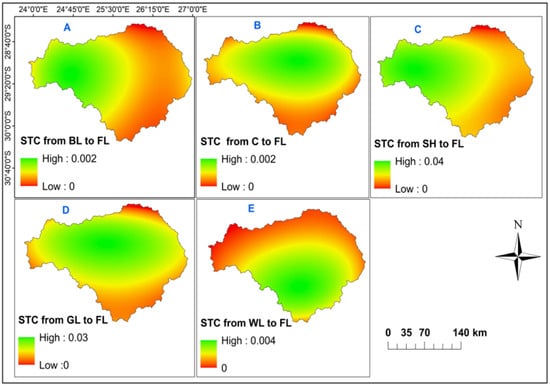

3.1.6. Spatial Trend of Change Toward Forest Land (FL)

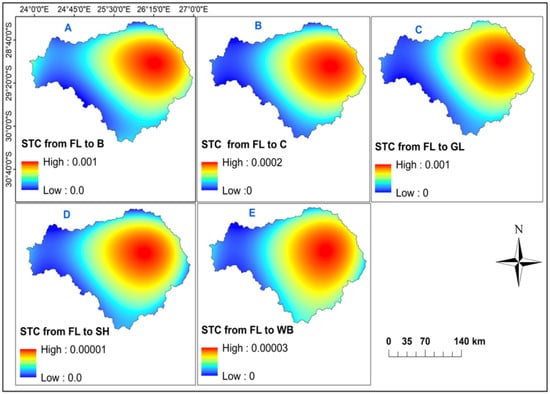

In the Land Change Modeler (LCM) of TerrSet LiberaGIS, a binary change surface is created by assigning a value of 1 to areas where other LULC classes have been converted to forest, indicating positive land cover change, and a value of 0 to areas where no change occurred. These binary values are treated as quantitative data, allowing them to be used in spatial analyses, modelling of change patterns, and statistical assessment of drivers influencing forest gain. The major spatial trend of change (STC) toward FL provides a quantitative measure of the directional bias of forest expansion from other land cover types. This analysis highlights that forest recovery within the catchment is spatially asymmetric and strongly influenced by both socioeconomic and environmental factors, as illustrated in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Spatial trend of LULC transitions to forest in the C5 SDR (1990–2022) derived from LCM, with values ranging from 0 (no gain) to +1 (high gain), highlighting hotspots of forest expansion alongside areas with minimal or no gain: (A) from BL to FL, (B) from C to FL, (C) from SH to FL, (D) from GL to FL and (E) from WL to FL.

BL to FL conversion exhibited a positive directional bias in the western sector (STC = 0.002), suggesting localized forest regeneration facilitated by reduced cultivation pressure and potential restoration efforts. In the east, the transition was negligible (STC = 0). This reflects stronger land-use competition from cropland and settlements. The C to FL transitions were concentrated in the north-central, east-central, and central regions (STC = 0.0016). Conversion was insignificant in the south, north, and western areas (STC = 0), indicating limited forest recovery at the expense of C in these zones. The SH to FL conversion was most pronounced in the west (STC = 0.04), while the magnitude decreases and becomes no change in the east, north, northeast, and southeast (STC = 0), which shows constraints from grazing, agricultural and settlement expansion, or less favorable biophysical conditions. The GL to FL transitions were significant in central, west-central, northwestern, and east-central sectors (STC = 0.03) while conversion was negligible along the southern and northern borders (STC = 0). The WL to FL conversion showed the highest directional transformation in the southern catchment (STC = 0.004). Conversion decreases or is negligible in the western, northwestern, northern, northeastern, and eastern regions (STC = 0).

As shown in Figure 10, forest land (FL) also underwent conversion to other LULC classes, particularly in the central, eastern, and east-central regions, where human activities such as urban and agricultural expansion are concentrated. These interventions have led to localized deforestation and the formation of conversion hotspots, even though the magnitude of forest contraction is smaller than the expansion discussed above. For instance, FL was converted to B in the central and eastern regions with an STC value of 0.001, while no change occurred in the western region (STC = 0.0) (Figure 10A). Overall, conversions from FL to B, FL to C, and FL to GL were minimal, whereas transitions to SH and WB were negligible across the same areas (Figure 10A–E).

Figure 10.

Spatial Trend of Change (STC) illustrating long-term conversion of FL to other LULC classes. Hotspot areas (positive STC values) denote consistent contraction driven mainly by urban and agricultural expansion, while cold-spot areas (zero and near-zero STC values) indicate stable forest cover: (A) from FL to B, (B) from FL to C, (C) from FL to GL, (D) from FL to SH and (E) from FL to WB.

Overall, the STC analysis underscores that forest expansion is directionally asymmetric and environmentally constrained. Western and central sectors show the strongest FL recovery, driven by land abandonment, reduced grazing pressure, favorable soils, topography, and targeted restoration efforts. Peripheral and intensively used areas exhibit minimal or negative directional trends, reflecting the overriding influence of human land-use and environmental limitations. Integrating these STC patterns into predictive modelling frameworks such as TerrSet LiberaGIS enhances understanding of directional pressures on forest regeneration and informs spatially targeted conservation and land management strategies.

4. Discussion

4.1. Forest Dynamics and Ecological Implications (1990–2022)

The spatial distribution of forested land in the C5 SDR exhibits distinct temporal dynamics influenced by both anthropogenic and environmental drivers. Figure 4 illustrates the concentration of forest expansion along riverbanks, particularly in the western, west-central, and southwestern regions.

4.1.1. Forest Decline Under Anthropogenic Pressure

Between 1990 and 2014, FL experienced a net decline, primarily due to its conversion to SH (221 km2), GL (278.4 km2), B (14.2 km2), and C (55.8 km2) (Table 2; Figure 5B). As shown in Figure 10, forest conversion hotspots are concentrated in the eastern-central, central, and eastern parts of the study area, which are densely populated and dominated by expanding agricultural land. This pattern reflects the combined pressures of agricultural expansion, urbanization, and land degradation on forest ecosystems, as widely documented in previous studies. For instance, land use and land cover change assessments in Côte d’Ivoire indicated that agricultural expansion and associated land degradation are major drivers of deforestation [58]. Similarly, research in Cameroon highlighted the role of urban growth in reducing forest and agricultural lands, emphasizing the importance of sustainable urban planning to mitigate environmental impacts [59]. In the Albertine Rift region of Africa, population pressure and global market demands were identified as key factors contributing to forest loss, with population growth and intensified agricultural production significantly affecting forest cover [60]. These findings are consistent with broader analyses reporting forest declines under socioeconomic and environmental pressures [1,4].

During this period, 259.9 km2 of FL persisted from 1990 to 2014, while 849.5 km2 was lost and 712.2 km2 was gained (Table 2; Figure 5A). This asymmetric pattern underscores that post-disturbance recovery and conservation interventions were insufficient to counterbalance widespread anthropogenic losses. Nevertheless, gains in FL were observed in areas of former grassland, shrubland, abandoned croplands, and urban sites, primarily through ecological restoration and urban forestry initiatives, such as the Tree for Home (TFH) program [61,62,63]. Persistent forest patches continued to provide essential ecosystem services, including provisioning services, regulating services, supporting, and biodiversity support [64].

The observed decline in FL has important ecological and environmental implications. Loss of forest cover exacerbates greenhouse gas emissions, soil erosion, and surface runoff, particularly in semi-arid catchments where forests are often restricted to riparian corridors or upland refugia [65]. These patterns align with regional and global observations of forest pressure arising from urban expansion, unsustainable land use, and agricultural intensification [66,67]. Collectively, the results underscore the complex interplay between human activities and environmental factors in shaping forest dynamics over the past two decades, highlighting the need for targeted restoration, sustainable land management, and conservation planning to enhance forest persistence and recovery.

4.1.2. Forest Recovery and Expansion (2014–2022)

In contrast, the period between 2014 and 2022 was characterized by pronounced forest recovery. Persistence analysis revealed that 284.9 km2 of original FL remained stable, while gains from other land-cover classes contributed 2037 km2, with only 712.2 km2 lost (Table 2). Spatially, these gains were concentrated along riparian corridors and drainage networks, highlighting the role of hydrologically favorable sites in supporting natural regeneration and afforestation efforts (Figure S1). The SH (1068 km2), GL (609.3 km2), C (45.5 km2), and BL (7.4 km2) were the main sources of net FL gains (Figure 7B). Figure 9 further indicates that FL expansion hotspots are spatially concentrated in the western and west-central regions (Figure 9A,C), central regions (Figure 9B,D), and southern areas (Figure 9E), highlighting the heterogeneous nature of FL dynamics across the study area. Forest recovery was asymmetric, with a relative loss of 60% followed by a gain of 86%, resulting in a net positive trajectory (Figure 6). These dynamics are consistent with processes of restoration initiatives, exclosure programs, and reduced anthropogenic disturbance in South Africa and other parts of the world [68,69,70]. Scenario analyses indicate that both climate change and human activity significantly contributed to forest expansion, with combined effects accounting for 50.20% of the observed increase [71].

Even though forest decline continues to be reported in many parts of the world, particularly in tropical regions such as the Amazon Basin and Southeast Asia, where deforestation rates remain high [11,64,72], our findings reveal an opposite and encouraging trend. In the study area, FL followed an asymmetric but positive trajectory, with a relative loss of 60% subsequently exceeded by a gain of 86%, resulting in a net increase (Figure 6). This recovery was primarily fueled by conversions from SH, GL, C, and BL, demonstrating how land-use transitions and reduced anthropogenic disturbances can facilitate regeneration. Such increasing trends resonate with the forest transition theory, which highlights a shift from decline to recovery under favorable socioecological and policy conditions [73,74]. Moreover, similar recovery dynamics have been reported in the Atlantic Forest of Brazil, where restoration programs have promoted natural regeneration [75], and in parts of Europe and North America, where reforestation has reversed long-standing declines [76]. Thus, while global forest loss persists, the increasing trend observed in our study exemplifies localized processes of recovery that contribute to the broader, though uneven, trajectory of forest transition worldwide.

Forest gains during this period have critical ecological implications. Expanded tree cover enhances carbon sequestration, mitigates climate change, improves soil stability, reduces erosion, and supports hydrological regulation [72,77]. Riparian forest recovery also strengthens biodiversity, improves habitat connectivity, and moderates local microclimates, providing resilience against climatic variability [77].

4.1.3. Cumulative Dynamics: 1990–2022

Across the full 32-year period, FL exhibited 1188 km2 of net increase at 37.1 km2 annual rate of change, highlighting landscape-scale ecological recovery. Gains were derived from transitions of BL (13.7 km2), WL (85.7 km2), GL (441 km2), and SH (704.7 km2) (Figure 7C). The STC shows that FL gains were primarily sourced from SH, GL, C, BL, and WL, with expansion concentrated along riparian corridors, abandoned farmlands, and degraded landscapes (Figure S1).

The binary change surface generated in TerrSet’s Land Change Modeler STC, where areas converted to forest are assigned a value of 1 and unchanged areas a value of 0, provides a quantitative representation of forest gain. This approach facilitates the identification of spatial patterns of change and the evaluation of factors driving forest recovery, highlighting areas most responsive to natural regeneration or restoration interventions [39,78]. Thus, the transitions from SH and GL likely indicate natural woody encroachment facilitated by reduced grazing and disturbance, while gains from C reflect land abandonment combined with active afforestation and reforestation. The rehabilitation of BL through afforestation and colonization underscores the capacity of degraded soils to support forest recovery under reduced disturbance, while FL gain from WL emphasizes riparian regeneration supported by hydrological advantages. These changes likely reflect shifts in land management, effective planning of forest restoration, reduced grazing pressure, climate variability, protecting the area and active afforestation/reforestation initiatives [63,68,79,80], demonstrating how ecological processes and anthropogenic interventions interact to drive forest recovery in semi-arid landscapes. Losses were minimal and primarily to grassland and bare land, indicating that restorative processes outweighed deforestation pressures. The asymmetric analysis shows that 63% of the 1990 FL was lost, while 84.4% of the 2022 FL represents newly established stands (Figure 6). Comparable dynamics have been reported across the African continent, where remote sensing assessments highlight substantial forest turnover and the establishment of new forest landscapes driven by land-use transitions and restoration initiatives [13]. Overall, FL transformed from a marginal land-cover class in 1990 into a dominant component of the landscape by 2022, reflecting a net restorative trend in semi-arid regions and inferred improvements in ecosystem functions. These findings align with global observations of forest recovery [81,82], and woody vegetation expansion in savanna and semi-arid biomes [80,82,83], while contrasting with deforestation trends reported in other parts of sub-Saharan Africa and globally [84]. Continued monitoring is critical to assess structural quality, species composition, and long-term resilience under ongoing anthropogenic and climatic pressures.

Complementing the STC and asymmetric analyses, remote sensing indicates that forested land in the C5 region expanded by approximately 140% between 1990 and 2022, with a particularly sharp 186% increase between 2014 and 2022. These gains, derived entirely from satellite observations, are remarkable given the semi-arid conditions of the region, characterized by low rainfall, high evapotranspiration, and limited soil moisture [51]. The classified imagery shows that much of this expansion occurred in areas previously and mainly mapped as grassland or shrubland, especially along riparian corridors, moisture-retentive valleys, and abandoned farmlands, consistent with spatial patterns of significant tree cover increase detected in other semi-arid regions of southern Africa [83]. Consistent with the observed forested land increase, forests and woodlands predominate on alluvial soils and across the numerous small floodplains associated with minor streams in the arid and semi-arid areas of South Africa [42]. These patterns are further supported by global observations, where forested land has expanded across many savanna regions, and in some humid savannas, forests are progressively encroaching into previously open landscapes [85]. Regional evidence from South Africa also supports these trends in the Maputaland Coastal Plain, showing that forestry increased by more than 100% between 1986 and 2019 [86]. Furthermore, long-term aerial photographic records indicate significant increases in significant tree cover across semi-arid conservation, commercial, and communal areas, with gains ranging from 3%–50% to 14%–58% over several decades, irrespective of substantial variations in land use and management [83]. These results suggest that global drivers, such as elevated atmospheric CO2 and nitrogen deposition, have likely enhanced woody plant competitiveness in grassy biomes, contributing to canopy expansion detectable by remote sensing [85]. Therefore, within the C5 landscape, the combination of riparian corridors and spatially heterogeneous soil moisture conditions likely facilitated the observed forest expansion. This interpretation supports the view that contemporary forests in the central C5 region are predominantly recent formations shaped by land-use transitions detectable through remote sensing. However, it is important to note that part of the apparent forest gain may reflect spectral confusion between shrubland and open woodland, as these classes often exhibit overlapping spectral responses in semi-arid environments. Such potential misclassification could have led to a slight overestimation of forested land, particularly in transitional areas where woody cover is sparse or seasonally variable.

Forests provide essential ecosystem services across four key categories: provisioning services such as timber, fuelwood, food, and genetic resources; regulating services including carbon sequestration, water-cycle regulation, and soil erosion control; supporting services such as nutrient cycling, soil formation, and habitat provision; and cultural services, including recreation, spiritual value, and education [81]. Therefore, the cumulative forest recovery documented in this study likely enhanced multiple ecosystem services, including soil stabilization, carbon sequestration, erosion control, improved hydrological regulation, and biodiversity conservation, highlighting the ecological significance of forest expansion in this semi-arid region [1,82]. Riparian forests provide disproportionate ecological benefits by enhancing infiltration, groundwater recharge, and local microclimates, thereby reinforcing landscape resilience in semi-arid environments [1]. These benefits reflect the broader ecological significance of forest expansion in semi-arid landscapes, supporting both landscape resilience and local ecosystem functioning.

4.1.4. Policy and Ecological Implications

The observed spatial dynamics of forest gains and shrubland losses provide valuable insights for land management and restoration planning in semi-arid ecosystems, where water availability, soil properties, and fire regimes strongly influence vegetation structure [84]. This study provides a robust reference framework for monitoring land-cover changes and offers valuable insights for conservation planning and sustainable land-use management. Importantly, the analysis underscores the need for further ground verification and integration with local land management records before drawing policy conclusions. Future research combining field validation, high-resolution imagery, and detailed plantation or land-use maps would enable a more accurate distinction between natural forest regeneration and commercial forestry, thereby enhancing both the ecological relevance and the policy applicability of land-cover assessments.

4.2. Limitation

This study provides a comprehensive assessment of FL cover change in the C5 semi-arid region, but limitations should be acknowledged. In this study, the forested land category encompasses contiguous (indigenous) forest, dense forest, dense plantation forest, open and sparse plantation forest, plantation woodlots, contiguous low forest and thicket, as well as open and dense woodland. Accordingly, the results should be interpreted with caution when inferring patterns for specific forest subtypes. The analysis relied on remote sensing data (Landsat and Sentinel-2) with different sensors and resolutions; although all datasets were resampled to a common 30 m resolution and legends harmonized, subtle temporal and spectral inconsistencies may persist. Despite these limitations, the study provides valuable insights into the spatial and temporal dynamics of forest land cover in the C5 semi-arid region and establishes a robust foundation for future research aimed at refining classification accuracy and improving change detection methodologies.

5. Conclusions

This study evaluated forestland (FL) change in the C5 semi-arid region from 1990 to 2022 in relation to eight other land-cover classes using remote sensing data. The SANLC datasets and the TerrSet–LiberaGIS Land Change Modeller were used to analyze changes in magnitude, direction, and source–sink relationships. Post-classification comparisons, transition matrices, and asymmetric gain–loss metrics quantified forest dynamics over time. The results confirmed the initial hypothesis of increasing forest cover, revealing a substantial net gain of 1188 km2 over the 32-year period, with the largest gains occurring in riparian corridors, abandoned farmlands, and moisture-retentive areas. These patterns indicate that semi-arid ecosystems, despite historical vulnerability to degradation, can exhibit remarkable resilience when ecological processes align with community-based restoration and policy support.

It should be noted that some apparent forest gain may result from spectral confusion between shrubland and open woodland, potentially causing slight overestimation of forested areas, particularly in transitional zones with sparse or seasonal woody cover. Despite these limitations, the findings provide important ecological and policy insights, supporting sustainable land-use planning and forest management in semi-arid landscapes. While the aggregated FL category yields robust results for decision-making, caution is advised when interpreting outcomes for specific forest subtypes or specialized applications, as structural differences may be masked. Moreover, continued monitoring is critical to assess structural quality, species composition, and long-term resilience under ongoing anthropogenic and climatic pressures.

Future work should disentangle the roles of policy, climate, and community actions in forest recovery, supported by long-term remote sensing and field monitoring to assess persistence, species composition, and ecosystem function. Quantitative analyses using regression or machine learning, coupled with spatially explicit assessments of regeneration dynamics, will help clarify the main drivers of forest change. Integrating hydrological and socioeconomic analyses will link forest dynamics to water security, livelihoods, and resilience, while scaling lessons from the C5 Catchment to other semi-arid systems in Southern Africa will support adaptive forest governance and sustainable restoration outcomes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/f17010064/s1, Figure S1: Spatial patterns of land-cover gains, losses, and persistence, showing LULC transition magnitude, configuration, and source–sink dynamics, highlighting ecotonal landscape sensitivity.

Author Contributions

K.H. and Y.E.W.; Spatial data collection; K.H. conceived and designed the methodology; K.H. analyzed the data; K.H. and Y.E.W. contributed to materials and analysis tools; and K.H. drafted the manuscript, and Y.E.W. edited the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

No external funding was received for this study.

Data Availability Statement

The original datasets presented in this study are openly available from the Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment (DFFE) at https://www.dffe.gov.za/egis (accessed on 5 July 2025). Meteorological datasets from the South African Weather Services used in this study are available on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment (DFFE) for providing the datasets used in this study. We also extend our sincere appreciation to the Central University of Technology (CUT) for supporting this research through material assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CUT | Central University of Technology |

| DFFE | Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment |

| SDR | Secondary Drainage Region m |

| SANLC | South Africa National Land Cover |

| LCM | Land Change Modeler |

| EGIS | Environmental Geographic Information Systems |

| STC | Spatial Trend of Change |

References

- FAO; UNEP. The State of the World’s Forests 2020. Forests, Biodiversity and People; FAO: Rome, Italy; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- King, J.A.; Weber, J.; Lawrence, P.; Roe, S.; Swann, A.L.S.; Val Martin, M. Global and Regional Hydrological Impacts of Global Forest Expansion. Biogeosciences 2024, 21, 3883–3902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, G.; Zeng, L. Logistic Regression in Rare Events Data. Polit. Anal. 2001, 9, 137–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020. Main Report; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ale, S.; Adjonou, K.; Segla, K.N.; Komi, K.; Zoungrana, J.B.B.; Aholou, C.; Kokou, K. Urban Forestry in Sub-Saharan Africa: Challenges, Contributions, and Future Directions for Combating Climate Change and Restoring Forest Landscapes. Sustainability 2025, 17, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, D.; Lininger, K.; Saxon, E. The Drivers of Tropical Deforestation: A Comprehensive Review; American Geophysical Union: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, A.C.; Dargie, G.C.; Cuni-Sanchez, A.; Mukendi, J.T.; Hubau, W.; Mukinzi, J.M.; Phillips, O.L.; Malhi, Y.; Sullivan, M.J.P.; Cooper, D.L.M.; et al. Resistance of African Tropical Forests to an Extreme Climate Anomaly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2003169118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO. The State of the World’s Forests 2022. Forest Pathways for Green Recovery and Building Inclusive, Resilient and Sustainable Economies; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Global Assessment Resources Forest 2025; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2025; ISBN 9788578110796. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. The Second Report on the State of the World’s Forest Genetic Resources; FAO Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture Assessments; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2025; ISBN 9789251396995. [Google Scholar]

- Raza, A.; Syed, N.R.; Fahmeed, R.; Acharki, S.; Hussain, S.; Zubair, M.; Vishwakarma, D.K.; Gaur, A.; Singh, B.P.; Okasha, A.M.; et al. A Remote Sensing and GIS-Based Analysis of Forest Cover Changes and Carbon Sequestration Trends over Three Decades. Environ. Dev. 2025, 55, 101232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahendra, J. Progress, Challenges and Opportunities on Global Forest Goal 3. In Proceedings of the Eighteenth Session of the United Nations Forum on Forests, New York, NY, USA, 6–10 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, X.; Liu, Y.; Qi, L.; Chen, J.; Wang, G.; Zhang, L.; Liu, R. Monitoring Forest Dynamics in Africa during 2000–2020 Using a Remotely Sensed Fractional Tree Cover Dataset. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2023, 16, 2212–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Liu, J.; He, G.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Long, T.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, W.; Yin, R.; Guo, Y.; et al. Data-Driven Forest Cover Change and Its Driving Factors Analysis in Africa. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 9, 780069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Asymmetric impacts of tropical forest gain and loss on temperature due to forest growth revealed by satellite observation. In Proceedings of the EGU General Assembly 2025, Vienna, Austria, 27 April–2 May 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budiharta, S.; Meijaard, E.; Erskine, P.D.; Rondinini, C.; Pacifici, M.; Wilson, K.A. Restoring Degraded Tropical Forests for Carbon and Biodiversity. Environ. Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 114020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukete, B.; Lori, T.; Mukete, T.; Mukete, N. Analysis of the Ipacts of Climate Variations Across Semi-Arid and Arid Regions of Southeast Africa. Asian Sci. Bull. 2024, 2, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Points, K.E.Y. Planning for Climate Change in the Semi-Arid Regions of Southern Africa. 2015. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10625/57367 (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Siyum, Z.G. Tropical Dry Forest Dynamics in the Context of Climate Change: Syntheses of Drivers, Gaps, and Management Perspectives. Ecol. Process. 2020, 9, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, S.; Laso Bayas, J.C.; See, L.; Schepaschenko, D.; Hofhansl, F.; Jung, M.; Dürauer, M.; Georgieva, I.; Danylo, O.; Lesiv, M.; et al. A Continental Assessment of the Drivers of Tropical Deforestation with a Focus on Protected Areas. Front. Conserv. Sci. 2022, 3, e830248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galiatsatos, N.; Donoghue, D.N.M.; Watt, P.; Bholanath, P.; Pickering, J.; Hansen, M.C.; Mahmood, A.R.J. An Assessment of Global Forest Change Datasets for National Forest Monitoring and Reporting. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Skutsch, M.; Paneque-Gálvez, J.; Ghilardi, A. Remote Sensing of Forest Degradation: A Review. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 103001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ait El Haj, F.; Ouadif, L.; Akhssas, A. Simulating and Predicting Future Land-Use/Land Cover Trends Using CA-Markov and LCM Models. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2023, 7, 100342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechner, A.M.; Foody, G.M.; Boyd, D.S. Applications in Remote Sensing to Forest Ecology and Management. One Earth 2020, 2, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, Z.S.; Scott, S.L.; Desmet, P.G.; Hoffman, M.T. Application of Landsat-Derived Vegetation Trends over South Africa: Potential for Monitoring Land Degradation and Restoration. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 113, 106206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutherford, M.C.; Mucina, L.; Powrie, L.W.; Rutherford, M. The South African National Vegetation Database: History, Development, Applications, Problems and Future. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2012, 108, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabuda, M.O.; Shoko, C.; Dube, T.; Mazvimavi, D. An Analysis of the Effects of Changes in Land Use and Land Cover on Runoff in the Luvuvhu Catchment, South Africa. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2024, 33, 101144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woyessa, Y.E.; Welderufael, W.A. Impact of Land-Use Change on Catchment Water Balance: A Case Study in the Central Region of South Africa. Geosci. Lett. 2021, 8, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwate, O.; Woyessa, Y.E.; David, W. Dynamics of Land Cover and Impact on Stream Flow in the Modder River Basin of South Africa: Case Study of a Quaternary Catchment. Int. J. Environ. Prot. Policy 2015, 3, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allnutt, C.E.; Gericke, O.J.; Pietersen, J.P.J. Estimation of Time Parameter Proportionality Ratios in Large Catchments: Case Study of the Modder-Riet River Catchment, South Africa. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2020, 13, e12628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gericke, O.J.; Smithers, J.C. Direct Estimation of Catchment Response Time Parameters in Medium to Large Catchments Using Observed Streamflow Data. Hydrol. Process. 2017, 31, 1125–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gericke, O.J.; Smithers, J.C. An Improved and Consistent Approach to Estimate Catchment Response Time Parameters: Case Study in the C5 Drainage Region, South Africa. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2018, 11, S284–S301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldwaik, S.Z.; Pontius, R.G. Intensity Analysis to Unify Measurements of Size and Stationarity of Land Changes by Interval, Category, and Transition. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2012, 106, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DFFE. Environmental Geographic Information Systems (EGIS). Available online: https://www.dffe.gov.za/egis (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- DFFE. The 2022 South African National Land Cover Data and Its Operational Use. In Proceedings of the National NCA Forum, Pretoria, South Africa, 7–8 August 2024. [Google Scholar]

- SANLC. South African National Land Cover (SANLC)-Awesome-Gee-Community-Catalog. Available online: https://gee-community-catalog.org/projects/sa_nlc/ (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Luncedo, N.; Kgaugelo, N. Sentinel-2 Land Cover Product Comparison: South African National Land Cover 2020 vs ESRI Global Land Cover 2020. Abstr. ICA 2023, 6, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastman, J.R.; Crema, S.C.; Rush, H.R.; Zhang, K. A Weighted Normalized Likelihood Procedure for Empirical Land Change Modeling. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2019, 5, 985–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark Labs Land Change Modeler-Geospatial Analytics. Available online: https://www.clarku.edu/centers/geospatial-analytics/terrset-liberagis-features/land-change-modeler/ (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- USGS. EarthExplorer. U.S. Geological Survey. Available online: https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Midgley, D.C.; Pitman, W.V.; Middleton, B.J. Surface Water Resources of South Africa: Drainage Region C-the Vaal Basin. Available online: https://www.gettextbooks.com/isbn/9781868451562/ (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Mucina, L.; Rutherford, M.C. The Vegetation of South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland; Strelitzia 19; South African National Biodiversity Institute: Pretoria, South Africa, 2011; ISBN 978-1919976-21-1. [Google Scholar]

- Fairbanks, D.H.K.; Thompson, M.W.; Vink, D.E.; Newbyb, T.S.; Van den Berg, H.M.; Edvard, D.A. The South African Land-Cover Characteristics Database: A Synopsis of the Landscape. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2000, 96, 69–82. [Google Scholar]

- Timm Hoffman, M. Changing Patterns of Rural Land Use and Land Cover in South Africa and Their Implications for Land Reform. J. S. Afr. Stud. 2014, 40, 707–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SANBI. Vegetation of South Africa: Nama-Karoo Biome. Available online: https://pza.sanbi.org/vegetation/nama-karoo-biome (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Rutherford, M.C.; Powrie, L.W.; Husted, L.B. Plant Diversity Consequences of a Herbivore-Driven Biome Switch from Grassland to Nama-Karoo Shrub Steppe in South Africa. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2012, 15, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gericke, O.J.; Pietersen, J.P.J. Disaggregation of Fixed Time Interval Rainfall to Continuous Measured Rainfall for the Purpose of Design Rainfall Estimation. Water SA 2018, 44, 557–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gericke, O.J.; Smithers, J.C. Derivation and Verification of Empirical Catchment Response Time Equations for Medium to Large Catchments in South Africa. Hydrol. Process. 2016, 30, 4384–4404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacqueline, J. A The Setting of Resource Water Quality Objectives for the Modder-Riet River Catchment. Master’s Thesis, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- DSSA. Census Statistics of South Africa 2022. Available online: https://www.open.africa/dataset/south-africa-census-2022 (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Hoffman, T.; Ashwell, A. Nature Divided: Land Degradation in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2003, 69, 116. [Google Scholar]

- DEFF. The 1990 South African National Land South African National Land-Cover Dataset: Implementation of Land-Use Maps for South Africa; DEFF: Pretoria, South Africa, 2015.

- DEFF. South African National Land Land-Cover Data User Report and MetaData; DEFF: Pretoria, South Africa, 2015; Volume 5, pp. 1–53.

- Thompson, M. South African National Land-Cover 2022 Accuracy Assessment Report (Public Release Report); DEFF: Pretoria, South Africa, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Environment Forestry and Fisheries (DEFF). South African National Land-Cover 2018/2020 Change Assessment Report (Public Release Report); DEFF: Pretoria, South Africa, 2022.

- DEFF. South African National Landcover 2022–Dataset–SAEOSS. Available online: https://saeoss.sansa.org.za/dataset/south_african_national_landcover_2022?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Clark Labs Idrisi Terrset to Terrset LiberaGIS-General-GISarea-Geographic Information Science Forum. Available online: https://www.gisarea.com/forums/topic/13640-idrisi-terrset-to-terrset-liberagis/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Kouassi, J.L.; Gyau, A.; Diby, L.; Bene, Y.; Kouamé, C. Assessing Land Use and Land Cover Change and Farmers’ Perceptions of Deforestation and Land Degradation in South-West Côte d’Ivoire, West Africa. Land 2021, 10, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deba Enomah, L.; Downs, J.; Acheampong, M.; Yu, Q.; Tanyi, S. Urban Expansion and the Loss of Agricultural Lands and Forest Cover in Limbe, Cameroon. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, S.J.; Palace, M.W.; Hartter, J.; Diem, J.E.; Chapman, C.A.; Southworth, J. Population Pressure and Global Markets Drive a Decade of Forest Cover Change in Africa’s Albertine Rift. Appl. Geogr. 2017, 81, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trees–South Africa Forestry (SAF). Scaling Urban Nature-Based Solutions with. Available online: https://saforestryonline.co.za/articles/scaling-urban-nature-based-solutions-with-trees/ (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- SAFM. Forestry in South Africa: Sustainable Management and Economic Potential. Available online: https://farmersmag.co.za/2023/05/forestry-in-south-africa-sustainable-management-and-economic-potential/ (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- TFH. Trees for Homes (TFH)—Food & Trees for Africa. Available online: https://trees.org.za/csi-esd/corporate-social-investment/trees-for-homes/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- FAO. The State of the World’s Forests 2024—Forest-Sector Innovations Towards a More Sustainable Future; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, T.R.H.; Brown, S.; Murray, L.; Sidman, G. Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Tropical Forest Degradation: An Underestimated Source. Carbon Balance Manag. 2017, 12, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Qiu, R.; Yao, J.; Hu, X.; Lin, J. The Effects of Urbanization on China’s Forest Loss from 2000 to 2012: Evidence from a Panel Analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 214, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambin, E.F.; Meyfroidt, P. Global Land Use Change, Economic Globalization, and the Looming Land Scarcity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 3465–3472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DFFE. Forestry Management Programme. Ten Million Trees: Department of Forestry, Fisheries, and the (DFFE). Available online: https://www.dffe.gov.za/index.php/fom_projectsprogrammes_tenmilliontrees?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Emiru, B.; Tefera, M.; Yigremachew, S.; Niguse, H.; Putzel, L.; Mekonen, M.R.; Habtemariam, K. Exclosures as Forest and Landscape Restoration Tools: Lessons from Tigray Region, Ethiopia Exclos Comme Instruments de Restauration de La Forêt et Du Paysage: Leçons Provenant de La Région Tigray, En Ethiopie Los Recintos Como Herramientas Para La Restaur. Int. For. Rev. 2017, 19, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Toto, R.; Alix-García, J.; Sims, K.R.E.; Coutinho, B.; Muñoz Brenes, C.; Pugliese, L.; Mendes, A.F. Evidence on Scaling Forest Restoration from the Atlantic Forest Restoration Pact in Brazil. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]