Abstract

The genus Pinus (~115 species) represents a cornerstone of boreal and temperate forests and plays a central role in global forestry, industrial applications, and carbon sequestration. Their distinctive biology—including exceptionally large genomes, guaiacyl-rich lignin, tracheid-based xylem, and pronounced seasonal growth regulation—makes pines both scientifically compelling and technically challenging to study. Recent advances in genomics and transcriptomics, supported by emerging multi-omics and computational frameworks, have significantly advanced our understanding of the molecular architecture of wood formation, including key processes such as NAC–MYB regulatory cascades, lignin biosynthesis pathways, and adaptive processes such as compression wood development. Yet functional studies remain limited by low transformation efficiency, regeneration difficulties, and a scarcity of conifer-optimized genetic tools. This review highlights recent breakthroughs in single-cell and spatial transcriptomics, CRISPR-based genome editing, synthetic promoter design, and machine learning-driven regulatory network prediction and comprehensively examines translational applications in biomass improvement, lignin engineering, stress resilience, and industrial biotechnology. By expanding the research frontiers of Pinus, we aim to connect molecular discovery with applied forestry and climate mitigation strategies.

1. Introduction

The genus Pinus belongs to the gymnosperms, one of the four major lineages of seed plants that bear naked seeds: conifers, cycads, ginkgo, and gnetophytes. Gymnosperms comprise about 1000 living species, with conifers as the dominant group (~615 species) [1]. Within conifers, the family Pinaceae is the largest, containing 11 genera and ~230 species, and Pinus is its most diverse genus, with ~115 species distributed across the Northern Hemisphere [2]. Pines are distinguished by needle-like leaves in fascicles, woody seed cones, and resin canals that function in defense against herbivores and pathogens [3].

The genus Pinus contributes about 40% of the world’s forest plantations [4]. Gymnosperms contribute more than half of the global woody biomass. Pinus, as a major component of plantations in temperate and boreal regions, accounts for a substantial fraction of this [5,6]. Pinus-dominated forests play essential ecological roles by sequestering atmospheric CO2, supporting biodiversity, stabilizing soils, and regulating hydrological cycles [7]. Economically, Pinus species are pillars of industrial forestry. Their wood is widely used for construction, pulp, paper, and engineered products, while resins, terpenoids, and phenolics support chemical, adhesive, and pharmaceutical industries [8]. Lignocellulosic biomass from pine is increasingly utilized for bioenergy, nanocellulose, and lignin-derived biomaterials [9]. Compression wood (CW), a specialized tissue formed under gravitational stress, with its high lignin content, provides a unique model for lignin-oriented applications [10]. The formation of CW represents a pronounced example of phenotypic plasticity in gymnosperms, enabling biomechanical adjustment to gravitational and environmental cues and distinguishing conifers from angiosperm tension-wood systems. Pine wood durability is strongly influenced by extractives, particularly terpenes and resins, which accumulate during heartwood formation and contribute to natural resistance against decay organisms and insects, while also representing valuable industrial resources for chemical and bio-based applications [9,11]. Beyond industry, some species, such as Pinus densiflora (Korean red pine), hold cultural and ecological importance in East Asia, where they function as keystone forest species and vital timber and resin sources [12]. Pines’ adaptability to drought, poor soils, and cold climates makes them central to global reforestation and afforestation efforts for climate mitigation [13]. The dual importance of Pinus species as ecological stabilizers and industrial resources underscores the urgency of advancing functional genomics for sustainable utilization under global change.

Pine genomes are among the largest in plants (20–40 Gb), primarily due to long terminal repeat retrotransposons (LTR-RTs) and expanded intronic regions [14,15]. Despite this, conifers maintain a stable diploid karyotype (2n = 24) [16]. The recent haplotype-resolved genome of P. densiflora revealed large-scale translocations, retrotransposon proliferation, transcription factor expansions, and allelic imbalances linked to stress adaptation and reproduction [17]. Earlier, draft genomes of Pinus taeda (Loblolly pine) and Pinus lambertiana (Sugar pine) provided foundational conifer genomic resources [18,19].

Developmentally, conifers differ markedly from angiosperms. Pines produce tracheids as the sole water-conducting cells, with torus–margo pit membranes conferring high hydraulic safety but lower efficiency, an adaptation to drought- and freeze-prone habitats [20]. Gymnosperm lignin is dominated by guaiacyl (G-type) monomers, in contrast to guaiacyl–syringyl (GS) lignin in angiosperms, making pine wood more recalcitrant industrially but mechanically stronger [10]. Molecular networks of wood formation also show lineage-specific features. In P. densiflora, the NAC transcription factor PdeNAC2 regulates tracheid differentiation with distinct downstream targets compared to angiosperm vascular-related NAC-domain (VND) genes [12]. Similarly, laccase gene family analyses identified PdeLAC28 as a lignin-polymerizing enzyme enriched in compression wood, underscoring conifer-specific lignification mechanisms [21]. Pines also exhibit strong seasonal regulation of growth. Cambial activity and xylem differentiation peak in spring and summer but are drastically reduced during winter dormancy. Transcriptomics reveal seasonal shifts: cell wall biosynthesis genes dominate during growth, while stress response genes prevail in dormancy [6,10]. Epigenetic mechanisms, including microRNAs and DNA methylation, further fine-tune these rhythms [6,22].

Despite advances in genomics, functional validation in Pinus remains challenging. Stable transformation is inefficient, and long generation times limit genetic studies [23]. Recent breakthroughs in protoplast-based transient expression systems in P. densiflora now allow promoter and effector–reporter assays [24]. Genome editing tools such as CRISPR/Cas9 and prime editing are being developed but currently show low efficiency compared to angiosperms. This review therefore aims to: (1) synthesize genomic and transcriptomic resources available for Pinus; (2) summarize molecular mechanisms of wood formation, including transcriptional regulators and lignin biosynthesis; and (3) highlight emerging functional genomics tools such as single-cell transcriptomics, multi-omics integration, and computational gene network prediction.

Ultimately, advancing Pinus functional genomics will not only deepen fundamental understanding but also enable translational applications in sustainable forestry. Such progress can enhance biomass productivity, optimize lignin composition, and improve stress resilience, positioning Pinus as both a model for conifer genomics and a strategic resource for the global bioeconomy and climate resilience.

2. Integrative Genomics in Pinus: From Structural Assembly to Functional Characterization

The study of Pinus genetics has entered a transformative era driven by rapid advancements in sequencing technologies and molecular tools. For decades, the genomic characterization of pines was hindered by their massive, highly repetitive genomes and biological recalcitrance to manipulation. However, the transition from early draft assemblies to high-quality, haplotype-resolved genomes has fundamentally shifted the landscape, revealing the complex evolutionary forces shaping conifer architecture. Concurrently, the development of functional genomics platforms—ranging from protoplast transient assays to emerging genome editing technologies—is beginning to bridge the gap between structural data and biological function. This section reviews the current state of Pinus genomic resources, comparative evolutionary insights, and the methodological frontiers enabling the functional dissection of wood formation and stress adaptation (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Landscape of functional genomics in Pinus species. A conceptual overview illustrating how genomic resources underpin functional genomics approaches and their translational applications in Pinus. High-quality whole-genome assemblies, transcriptomic datasets, and emerging epigenomic profiles provide the basis for resolving gene regulatory networks that control wood formation. Core regulatory modules—most notably the NAC–MYB transcriptional cascade and its downstream targets—act in concert with phytohormone signaling to orchestrate secondary cell wall biosynthesis. Functional genomics platforms, including CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing and synthetic promoter engineering, enable targeted manipulation of these pathways. Together, these advances drive applications in forestry biotechnology, such as biomass enhancement, improved stress resilience, industrial biomaterial production, and increased carbon sequestration potential.

2.1. Advances in Genome Sequencing and Assembly

Sequencing Pinus genomes represents a monumental challenge in plant genomics due to their extraordinary size and high repetitive content. Pine genomes range from 20 to over 40 Gb—approximately 100-fold larger than the genome of Populus and about 200-fold larger than that of Arabidopsis (Table 1). Early genomic efforts relied on expressed sequence tags (ESTs) and gene-enrichment strategies, which provided initial insights into conifer gene families and metabolism [25].

Table 1.

Genomic and transcriptomic resources available in Pinus species.

The first landmark conifer genome was that of Picea abies (Norway spruce) [62], followed by the draft assembly of Pinus taeda (22 Gb), constructed using haploid megagametophyte DNA and Illumina sequencing [14,18]. The P. taeda genome revealed over 50,000 protein-coding genes and an unprecedented repeat content (>80%) [14]. Subsequent iterations utilized long-read sequencing and optical mapping to improve contiguity [63]. Additional resources include the P. lambertiana (31 Gb) draft genome [19] and a chromosome-level assembly of P. tabuliformis (Chinese red pine), which highlighted large-scale rearrangements and retrotransposon proliferation [64].

Most recently, the haplotype-resolved genome of P. densiflora (Korean red pine) was assembled using PacBio HiFi and Hi-C technologies, yielding a 21.7 Gb assembly with a contig N50 of 24.7 Mb and >95% BUSCO completeness [17]. Crucially, this assembly separated the highly heterozygous parental chromosomes, allowing researchers to directly analyze allele-specific expression (ASE) and presence-absence variations (PAVs)—features previously obscured in consensus assemblies. This allele-aware resource facilitates detailed investigations into structural rearrangements and gene family expansions associated with flowering, stress adaptation, and wood formation [17].

The immense size of these genomes—more than seven times larger than the human genome—is driven not by whole-genome duplications, but by the massive, ongoing proliferation of long terminal repeat retrotransposons (LTR-RTs). The massive accumulation of retrotransposons in pine genomes not only inflates genome size but also shapes epigenetic landscapes through DNA methylation and chromatin organization, potentially influencing the regulation of genes involved in xylogenesis. Specific subgroups of gypsy and copia families have expanded through both ancient (16–22 million years ago) and recent (2–6 million years ago) bursts. These elements are functionally dynamic: copia elements are often enriched in gene-rich regions, whereas gypsy elements dominate gene-poor regions, suggesting they play a role in the diversification of key gene families, including transcription factors.

Table 1 summarizes the major genomic and transcriptomic resources currently available for Pinus species. These range from early draft to chromosome-level and haplotype-resolved assemblies, covering genomes of ~20–31 Gb, all with a stable diploid karyotype (2n = 24). The varying contiguity, from draft references (P. lambertiana) to high-quality haplotype-resolved assemblies (P. tabuliformis, P. densiflora), reflects rapid progress enabled by long-read and Hi-C technologies. Complementary datasets—including RNA-seq, miRNA, DNA methylation, and metabolomic analyses—further enhance functional annotation and gene discovery. Despite improved assemblies, incomplete functional annotation—particularly for cell-wall-related enzyme families such as laccases and peroxidases—remains a critical limitation for mechanistic studies in conifers.

Collectively, these resources establish a foundation for comparative genomics, functional analyses, and molecular tool development in Pinus, a genus long constrained by its large, repetitive genomes and technical limitations.

2.2. Comparative Genomics and Evolutionary Insight

Comparative analyses among pines, other conifers, and angiosperms elucidate both conserved and lineage-specific evolutionary trajectories. Conifers evolved approximately 390 million years ago, significantly predating angiosperms (140–125 million years ago). This long separation has resulted in distinctive genome organizations, gene regulation networks, and wood formation pathways [65]. Synteny analysis among P. taeda, P. lambertiana, P. tabuliformis, and P. densiflora reveals conservation across most chromosomes, punctuated by species-specific translocations and inversions that contribute to divergence in stress response mechanisms [17].

Comparisons with angiosperms such as Populus trichocarpa or Arabidopsis reveal distinct metabolic strategies. For instance, while lignin biosynthetic pathways are conserved, conifers lack syringyl-specific enzymes like ferulate 5-hydroxylase (F5H), resulting in Guaiacyl (G)-rich lignin [25]. This composition confers higher recalcitrance to the wood matrix. Similarly, while NAC and MYB transcription factors regulate secondary cell wall (SCW) formation in all vascular plants, gymnosperm regulators are specialized for tracheid-based xylem development [12].

Comparative transcriptomics further highlights unique seasonal regulatory patterns. Unlike angiosperms, where cambial activity is primarily driven by photoperiod and hormones, conifers integrate environmental cues with long-term epigenetic regulation to modulate growth and dormancy—an essential adaptation for survival in boreal climates [66]. Convergent evolution is also evident in secondary metabolism; for example, terpene synthase families are expanded in both lineages, yet conifers rely more heavily on oleoresins for defense [67]. Overall, comparative genomics underscores the deep evolutionary conservation of core vascular plant processes while revealing unique adaptations in Pinus that underpin their ecological dominance and industrial significance.

2.3. Transcriptomic, Small RNA, and Epigenomic Landscapes

Transcriptomic studies have generated comprehensive expression atlases for Pinus tissues, advancing our understanding of wood formation and stress responses [68,69,70]. The P. taeda transcriptome provided early identification of stress-responsive genes [11], while studies in P. densiflora revealed seasonal reprogramming: cambial reactivation in spring is linked to auxin and cytokinin pathways, whereas winter dormancy involves the upregulation of stress and defense genes [6,10].

Beyond mRNA, small RNAs are critical regulators. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) such as miR166, miR397, and miR408 are conserved regulators of vascular differentiation and laccase gene expression across seed plants [71,72]. In conifers, miRNA-mediated regulation of NAC and MYB transcription factors adds a layer of fine-tuned control over tracheid differentiation [73].

Although epigenomic data remain limited due to genome size, evidence suggests that DNA methylation and histone modifications regulate seasonal cambial activity. Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing in spruce revealed extensive methylation in repetitive regions with dynamic shifts during stress adaptation [74]. Similar mechanisms likely operate in Pinus, where epigenetic reprogramming may encode the “memory” of environmental cues. The integration of single-cell and spatial transcriptomics with allele-aware assemblies now offers the potential to dissect these networks at unprecedented resolution [75] (Figure 1).

2.4. Overcoming Barriers in Functional Genomics

Despite genomic advances, functional validation in Pinus remains constrained by biological barriers. Stable transformation is historically difficult due to long generation times, high levels of secondary metabolites, and recalcitrance to tissue culture [76]. While Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of embryogenic tissues has been reported in P. pinaster, P. radiata, and P. taeda, efficiencies remain low (<1–2%) and regeneration is time-consuming [77,78]. Alternative methods like biolistics yield transient expression but often result in unstable, rearranged insertions [79,80].

Given these limitations, protoplast-based transient expression has emerged as a vital alternative. Protoplasts allow for the rapid assessment of gene function, promoter activity, and protein–protein interactions [81]. Early isolation difficulties in Picea abies and P. taeda [82] have been overcome by recent protocol optimizations in P. densiflora, achieving high yields and transfection efficiencies (>90%) [23,83]. These systems enable promoter-reporter assays and the validation of transcription factor interactions (e.g., NACs, MYBs) in a native conifer context [84]. While protoplasts cannot replace heritable transformation, they currently represent the most practical high-throughput method for characterizing pine genes and screening CRISPR guide RNAs [85].

2.5. Genome Editing and Synthetic Biology Horizons

The advent of genome editing offers new possibilities for gymnosperm functional genomics, though applications remain in their infancy. CRISPR/Cas9 and Cas12a (Cpf1) systems have been successfully tested in conifer protoplasts and embryogenic calli, demonstrating the feasibility of targeted mutagenesis in P. radiata and Picea glauca [86,87,88]. However, the regeneration of edited whole plants remains a significant bottleneck [87]. Protoplasts currently serve as the primary platform for validating nuclease activity [89], while emerging tools like base and prime editing hold promise for precise modifications without double-strand breaks [90,91].

To complement editing tools, synthetic biology approaches are being developed to fine-tune gene expression. While native promoters (e.g., ubiquitin, actin) are commonly used, their activity varies across tissues [92,93]. Synthetic promoters, engineered by combining specific cis-regulatory motifs, offer precise control. Although promoter engineering in conifers lags behind angiosperms, stress-responsive and constitutive promoters have been tested with varying success [92]. Future strategies involve designing modular synthetic promoters with hormone-responsive elements (e.g., auxin, gibberellin) to target wood formation specifically [93].

Ultimately, the combination of allele-aware genomic resources, improved protoplast systems, and precise synthetic regulatory tools is paving the way for “gene stacking”—the simultaneous introduction of multiple traits such as modified lignin and stress tolerance [94,95]. While challenges in regeneration persist, these integrative approaches define the future of functional genomics in Pinus.

3. Molecular Mechanisms of Wood Formation

Wood formation in Pinus is a complex developmental process governed by a hierarchical regulatory network that orchestrates cell division, expansion, secondary cell wall (SCW) deposition, and programmed cell death (PCD). Unlike angiosperms, which possess specialized vessel elements and fibers, conifers rely exclusively on tracheids for both water transport and mechanical support. This structural distinction is underpinned by unique molecular strategies, ranging from specific transcriptional cascades to specialized lignin biosynthesis pathways. Furthermore, environmental and gravitational cues induce adaptive responses, such as compression wood (CW) formation, through integrated hormonal signaling [6,10]. This section explores the molecular mechanisms driving wood formation in Pinus, highlighting the conservation and divergence of regulatory networks compared to angiosperm models (Figure 2).

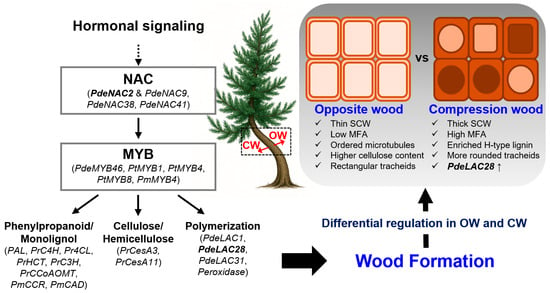

Figure 2.

Regulatory network governing wood formation and compression wood development in Pinus. A schematic model summarizing hormonal and transcriptional controls underlying wood formation in Pinus. Hormonal signaling activates NAC transcription factors, which subsequently regulate MYB factors. This NAC–MYB cascade coordinates major metabolic pathways for secondary cell wall (SCW) assembly, including phenylpropanoid/monolignol biosynthesis, cellulose and hemicellulose deposition, and lignin polymerization. Differential regulation of these pathways generates the distinct tracheid properties of opposite wood (OW) and compression wood (CW). OW shows thin SCWs, low microfibril angle (MFA), ordered microtubules, higher cellulose content, and rectangular tracheids; CW displays thick SCWs, high MFA, enriched H-type/G-type lignin, more rounded tracheids, and elevated PdeLAC28 expression. The dashed red boxes indicate OW and CW positions on the lower and upper sides of the inclined stem. These coordinated molecular and anatomical changes underpin the formation of gravitationally induced CW.

3.1. Regulatory Networks: NAC–MYB and Downstream Cascades

Wood formation in Pinus is governed by a multilayered regulatory network in which transcription factors coordinate SCW biosynthesis, lignification, and programmed cell death (PCD). Central to this network are NAC domain and MYB transcription factors, which function in a hierarchical cascade. In angiosperms, members of the VASCULAR-RELATED NAC-DOMAIN (VND) and NAC SECONDARY WALL THICKENING PROMOTING FACTOR (NST/SND) families act as master regulators, directly activating secondary switches such as MYB46 and MYB83, which in turn orchestrate the expression of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin biosynthetic genes [96,97,98].

In conifers, regulatory modules homologous to those in angiosperms exist but have been adapted to tracheid-based xylem rather than vessel element systems (Figure 2) (Table 2). Transcriptomic studies in P. taeda and P. densiflora identified multiple NAC-domain genes with strong expression in developing xylem [15,70,99]. Functional analyses revealed that PdeNAC2, a close homolog of Arabidopsis VND6, is a central regulator of tracheid differentiation. Overexpression of PdeNAC2 in Arabidopsis and poplar activated SCW biosynthesis and PCD pathways and even induced ectopic vessel-like cell formation—demonstrating conservation of core regulatory functions across lineages. However, comparative genome-wide analyses showed clear divergence in downstream networks [11]. PdeNAC2 and AtVND6 share only a limited set of direct targets, including MYB46, MYB83, and several PCD-associated genes. Unlike AtVND6, PdeNAC2 did not regulate vessel-specific traits such as pit formation genes (e.g., ROP signaling components, MIDD1) required for perforation plate development, underscoring that while the core program of SCW construction is conserved, lineage-specific modules have evolved to generate distinct anatomical features. These findings suggest that since the relatively recent divergence of angiosperms from gymnosperms, NAC transcription factors in angiosperms have evolved to regulate vessel-forming gene networks. This divergence highlights both the evolutionary conservation of SCW regulation and the specialization of gymnosperms for hydraulic safety and mechanical resilience through tracheid-only xylem.

Table 2.

Representative genes and pathways involved in Pinus wood formation.

Downstream of NAC regulators, MYB transcription factors provide specificity and fine-tuning. Orthologs of MYB46/83 in conifers regulate SCW-related genes such as CesA, laccases, and peroxidases, while lineage-specific MYBs are implicated in modulating lignin biosynthesis and compression wood formation [73,100,103]. Importantly, conifer MYB repressors negatively modulate phenylpropanoid metabolism, balancing carbon allocation between structural lignin and other pathways [103].

Collectively, the NAC–MYB cascade in Pinus represents a conserved regulatory module with conifer-specific adaptations. The ability of PdeNAC2 to partially substitute for angiosperm VND6 while maintaining unique target gene specificity illustrates the evolutionary divergence of transcriptional control between tracheid-based and vessel-based xylem systems. This divergence likely underpins both the hydraulic safety strategies of gymnosperms and their distinct wood chemical composition, positioning the NAC–MYB network as a central axis of wood biology in Pinus (Figure 2) (Table 2).

3.2. Lignin Biosynthesis

Lignin biosynthesis is a defining feature of conifer secondary growth. Gymnosperm lignin is almost exclusively guaiacyl (G-type), synthesized from coniferyl alcohol, unlike angiosperm lignin, which also incorporates syringyl (S-type) monomers derived from sinapyl alcohol. The absence of ferulate 5-hydroxylase (F5H) activity in conifers explains this distinction [21,66].

The biosynthesis of monolignols in Pinus begins with the deamination of phenylalanine by phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL), the first committed step of the phenylpropanoid pathway. Key enzymes include phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL), cinnamate-4-hydroxylase (C4H), 4-coumarate-CoA ligase (4CL), caffeoyl-CoA O-methyltransferase (CCoAOMT), cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase (CAD), and cinnamoyl-CoA reductase (CCR), each of which is strongly expressed in differentiating xylem [15,41,47,68,101,104]. Transcriptomic profiling in P. taeda and P. densiflora confirms the seasonal regulation of these genes, with elevated expression during active wood formation in spring and summer, linking monolignol biosynthesis directly to cambial dynamics.

The polymerization of monolignols into lignin is catalyzed by oxidative enzymes, primarily laccases and class III peroxidases. In conifers, laccases—multi-copper oxidases with conserved copper-binding motifs—play a dominant role in G-lignin deposition. Early studies in Picea abies and P. taeda revealed multiple laccase isoforms with xylem-preferential expression [105,106]. A recent genome-wide analysis in P. densiflora identified 54 laccase genes (PdeLACs) grouped into five phylogenetic clades, with extensive diversity in substrate-binding loops suggesting functional specialization. Among these, 23 PdeLACs were highly expressed in developing xylem, and three (PdeLAC28, PdeLAC1, and PdeLAC31) showed exclusive upregulation in compression wood. Functional validation demonstrated that overexpression of PdeLAC28 in poplar increased xylem area, secondary wall thickness, and Klason lignin content, establishing its critical role in lignification and compression wood development [21] (Figure 2).

Although peroxidases also contribute to radical-mediated monolignol coupling, conifer studies suggest their role is complementary rather than primary, with laccases providing the major catalytic capacity [107]. Notably, compression wood (CW) lignin in gymnosperms exhibits altered composition and higher deposition rates, closely associated with enhanced activity of specific laccase isoforms [21].

Together, these enzymatic and molecular studies highlight the specialization of conifer lignification toward G-type lignin, underpinned by a large and diverse laccase gene family. This specialization not only defines the structural and hydraulic properties of pine wood but also impacts its industrial processing, influencing pulping efficiency, bioenergy conversion, and potential lignin valorization strategies.

3.3. Hormonal Regulation of Secondary Growth

Hormonal signals orchestrate the timing, extent, and patterning of cambial activity and SCW deposition in conifers. Auxin is a key regulator, establishing a gradient across the cambial zone that directs cell division and xylem differentiation. High auxin levels promote cambial activity and differentiation of tracheids, consistent with observations in Picea abies and Pinus sylvestris [108].

Cytokinins act synergistically with auxin to promote cambial cell division in conifers, and the balance between these hormones is a key determinant of growth rate and annual ring width, while gibberellins (GAs) stimulate xylem fiber elongation and secondary wall thickening [109]. Recent studies in angiosperms reveal local de novo GA biosynthesis within stem cambial zones, directly contributing to secondary growth [110]. In conifers, GAs also influence CW formation, underscoring their role in hormonal control of mechanical adaptation.

Ethylene modulates wood formation and reaction wood development. In both hardwoods and conifers, ethylene cooperates with auxin during CW formation [111]. Ethylene application in conifer stems enhances lignin deposition and alters tracheid morphology, facilitating mechanical stress responses. Loss of ethylene signaling reduces asymmetric growth adaptation in inclined stems, affirming its role in reaction wood modulation [112].

Abscisic acid (ABA), while primarily associated with stress responses, plays a role in seasonal cambial regulation, promoting winter dormancy and directing latewood formation in pines [113].

Brassinosteroids (BRs) have recently been recognized as central regulators of vascular development. Exogenous BR application in P. massoniana promotes secondary xylem formation in a dose-dependent manner, elevating lignin content even amid downregulated phenylpropanoid transcripts, suggesting alternative pathways in pine lignification [114]. In other tree species, BRs enhance xylem growth and interact with key regulatory genes [115].

Thus, hormonal regulation in Pinus integrates multiple signaling pathways that coordinate growth, environmental responses, and seasonal transitions. The interplay among auxin, GA, ethylene, and ABA creates a dynamic regulatory network controlling both developmental and adaptive aspects of wood formation (Figure 2).

3.4. Compression Wood Formation and Adaptive Responses

Compression wood (CW) is a specialized reaction wood formed on the lower side of leaning conifer stems and branches, functioning to restore vertical growth. Anatomically, CW tracheids are shorter and rounded and exhibit thicker secondary walls with higher lignin and lower cellulose content [116]. These anatomical features contrast with those of angiosperm tension wood.

Molecular studies reveal that CW formation involves extensive reprogramming of transcriptional and metabolic pathways. Transcriptome analyses in Picea abies and P. densiflora identified differential upregulation of lignin biosynthetic genes, NAC and MYB transcription factors, and laccase/peroxidase isoforms specifically in CW [10,111]. Hormonal signals, particularly elevated auxin and ethylene, are strongly associated with CW induction [117]. Lignin in CW is enriched in p-hydroxyphenyl (H) units and guaiacyl (G) lignin, yielding increased density and rigidity. Alterations in microfibril angle and wall layering further modify wood mechanics, allowing the tree to correct its orientation under gravitational stress [118] (Figure 2).

From an ecological perspective, CW represents a critical adaptation enabling conifers to maintain upright growth in dynamic environments. Industrially, however, it is undesirable due to higher lignin content, increased recalcitrance, and altered pulping properties [119]. Understanding the molecular regulation of CW offers opportunities to balance adaptive and industrial traits in pine breeding and biotechnology.

4. Emerging Tools and Integrative Approaches

As the structural phase of Pinus genomics reaches maturity with high-quality genome assemblies, the field is pivoting toward high-resolution functional dissection. The complexity of wood formation—a process involving dynamic temporal shifts and spatial heterogeneity within the cambial zone—demands technologies that go beyond bulk tissue analysis. This section explores the frontier of conifer systems biology, highlighting how single-cell resolution, multi-omics integration, and machine-learning-driven network modeling are overcoming the challenges of massive genomes and perennial life cycles to reveal the systems-level architecture of pine biology (Figure 3).

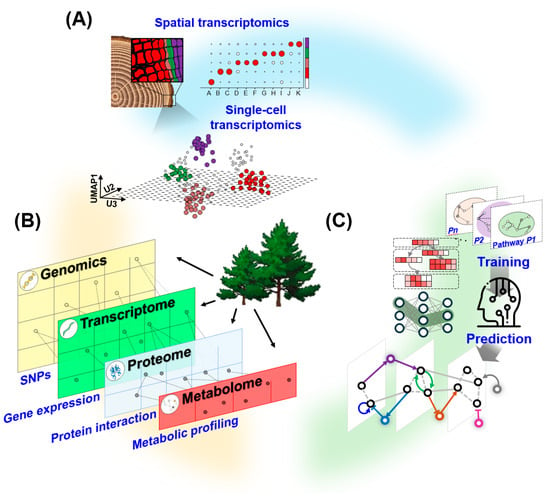

Figure 3.

Emerging tools and integrative approaches for Pinus research. A suite of next-generation technologies is transforming the study of conifer biology by providing finer resolution, deeper molecular context, and predictive power for trait discovery, collectively forming a comprehensive platform for dissecting conifer development and accelerating trait improvement in forestry biotechnology. (A) Spatial and single-cell transcriptomics resolve gene expression dynamics and cellular heterogeneity in Pinus wood tissues, with spatial mapping and UMAP clustering illustrating anatomical and cell-type specificity. (B) Multi-omics integration—encompassing genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—enables systems-level characterization of regulatory networks underlying key traits such as growth, wood formation, and stress responses. (C) Machine learning frameworks leverage multi-omics features to train predictive models for gene function, regulatory modules, and phenotypic traits.

4.1. Single-Cell Genomics and Spatial Transcriptomics

Single-cell and spatial transcriptomic technologies are transforming plant biology by enabling gene expression profiling at cellular and tissue-level resolution. For Pinus and other conifers, these approaches are particularly valuable given the complexity of secondary growth, where multiple developmental trajectories—from cambial division to xylem differentiation and programmed cell death—coexist within millimeters of tissue (Figure 3).

Bulk transcriptomics has provided foundational insights into seasonal wood formation. Resources such as the NorWood atlas in Picea abies [120] and cell-type-resolved transcriptomes in Picea glauca [121] established the baseline for conifer evo-devo studies. More recently, high-resolution datasets in P. bungeana (Lacebark pine) identified gene modules associated with the multilayered deposition of the SCW, demonstrating the necessity of spatially resolved data to understand the kinetics of wall thickening [29].

However, bulk approaches inherently mask cellular heterogeneity. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) can profile thousands of individual cells, distinguishing between ray initials, fusiform initials, and their derivatives. Alternatively, single-nucleus RNA-seq (snRNA-seq) avoids the technical challenges of protoplast isolation from lignified tissues, enabling the analysis of frozen samples [122]. These methods offer the potential to map the precise developmental trajectories of Pinus cambial cells and link environmental cues to cell-specific transcriptional responses. Complementing this, spatial transcriptomics preserves positional context, allowing researchers to visualize transcriptional gradients across the phloem–cambium–xylem continuum [120]. In pine stems, the thick secondary walls of tracheids pose challenges for spatial transcriptomics, highlighting the potential of combining laser microdissection with single-cell or single-nucleus RNA sequencing to resolve cambial heterogeneity.

Adding another dimension to this regulatory landscape, small RNA profiling in P. contorta (Lodgepole pine) has revealed unique, lineage-specific silencing signatures [38]. The integration of small RNA profiling with single-cell and spatial maps will provide a holistic view of post-transcriptional regulation. Collectively, these high-resolution approaches represent the next frontier for conifer functional genomics, offering unprecedented insight into the cellular basis of wood development and phenotypic plasticity (Figure 3).

4.2. Multi-Omics Integration

While genomics and transcriptomics provide a parts list and expression map, they do not fully capture the functional state of the tree. Transcript levels often do not correlate perfectly with protein abundance or metabolic flux due to post-transcriptional and post-translational regulation. Therefore, integrative multi-omics frameworks are essential for constructing systems-level models of Pinus biology (Figure 3).

Transcriptomics remains the most widely applied tool, generating expression atlases across diverse tissues [7,15,68]. However, proteomic and metabolomic layers often reflect the physiological reality of wood formation more accurately. In Picea abies and P. sylvestris, seasonal shifts in lignin-related enzymes and stress-responsive proteins have been shown to drive the transition between active growth and dormancy, even when transcript levels remain stable [7,35]. Furthermore, phosphoproteomic profiling in Picea abies revealed that reversible protein phosphorylation is a key switch for cambial reactivation, a mechanism invisible to RNA sequencing alone [123]. Proteomic analyses in conifers are constrained by secondary metabolite interference, difficulties in protein extraction from lignified tissues, and the wide dynamic range of protein abundance, which together limit detection of low-abundance regulatory proteins despite recent methodological advances [6,7,123].

Metabolomics provides a direct readout of pathway activity. Seasonal profiling has mapped dynamic fluctuations in phenolics, flavonoids, and monolignols [124]. In P. taeda, combined transcriptome–metabolome analyses uncovered the coordinated regulation of terpenoid and flavonoid biosynthesis, linking metabolic flux directly to transcriptional control [102]. In P. radiata, an integrated physiological, proteomic, and metabolomic approach demonstrated the complex cross-talk between photosynthesis and phenylpropanoid metabolism under UV stress [125].

Epigenomics adds the final layer of long-term regulation. DNA methylation and chromatin accessibility patterns are tightly associated with the seasonal growth–dormancy cycle in Picea [126], suggesting that epigenetic “memory” is crucial for perennial adaptation. Integrating these multi-omics layers—as successfully demonstrated in Populus [120]—will allow researchers to identify central regulatory hubs in Pinus, connecting molecular data to complex traits like wood density and climate resilience.

4.3. Computational Biology and Network Prediction

The scale of conifer genomes—often exceeding 20 Gb and saturated with repetitive sequences—presents a computational challenge that standard bioinformatics pipelines struggle to address. Consequently, machine learning (ML), deep learning, and gene regulatory network (GRN) modeling are becoming indispensable tools in Pinus genomics (Figure 3).

A persistent challenge is limited functional annotation compared to angiosperm models [18]. Nonetheless, network inference from transcriptomic data has identified candidate regulators of SCW biosynthesis and seasonal dormancy in conifers [66,120]. Recent single-cell and spatial transcriptomic studies, together with allele-aware genome assemblies, have begun to reveal promoter architecture and regulatory element landscapes across conifer genomes [64,75]. Although deep learning-based promoter and transcription start site prediction models were originally developed in other plant systems [127], these approaches provide a conceptual framework that can be adapted for promoter discovery and gene regulatory network reconstruction in large conifer genomes.

ML algorithms such as random forest and support vector machines have been applied in plant systems to classify cis-elements regulating wood formation and stress responses [128]. Deep learning models, including convolutional and recurrent neural networks, are increasingly used to predict gene expression from promoter sequences and chromatin features [129]. For large-genome conifers, these methods are especially valuable for identifying regulatory elements in the absence of complete annotations.

In Arabidopsis, GRN modeling successfully reconstructed the NAC–MYB cascade controlling SCW formation [96]. In Picea abies, seasonal GRNs revealed regulators of cambial dormancy and reactivation [66]. With expanding Pinus transcriptomic and proteomic resources, ML-driven GRN prediction will be essential for identifying master regulators of wood biology and stress resilience.

The next step lies in coupling computational predictions with high-throughput experimental validation, including protoplast assays and CRISPR screening. This integration will convert large-scale genomic datasets into actionable biological insights, advancing both fundamental understanding and translational applications in forestry.

5. Applications and Translational Perspectives

Advances in angiosperm tree systems, particularly Populus, provide valuable reference frameworks for understanding the potential of functional genomics and biotechnology in long-lived woody species. In poplar, integrative genomics has enabled the transition from high-quality genome assemblies to functional validation of wood formation regulators, including NAC–MYB transcriptional cascades, hormone biosynthesis genes, and lignin-modifying enzymes. Efficient transformation systems and CRISPR/Cas-based genome editing have further facilitated multigene engineering for biomass enhancement, lignin modification, and stress resilience. While these achievements cannot be directly extrapolated to Pinus due to fundamental biological and technical differences, they demonstrate that complex woody traits are amenable to molecular dissection and manipulation. These angiosperm examples thus serve as conceptual benchmarks, underscoring the feasibility and long-term potential of developing conifer-optimized functional genomics platforms.

5.1. Genetic Engineering for Biomass and Lignin Modification

Genetic engineering of Pinus offers transformative opportunities to enhance biomass yield and tailor lignin composition for industrial applications. Conifers are already among the most productive biomass accumulators in temperate and boreal ecosystems, yet conventional breeding is hindered by long generation times and large, complex genomes. Modern biotechnological approaches provide targeted strategies to accelerate improvement in growth and wood traits [89] (Figure 3).

Enhancing biomass yield focuses on regulatory networks controlling cambial activity and tracheid development. NAC and MYB transcription factors, central regulators of SCW formation, represent promising engineering targets [96,103]. Overexpression of gibberellin biosynthetic genes such as GA20-oxidase increases stem elongation and fiber length in Populus [109], and similar pathways are conserved in conifers [130]. Conversely, repression of DELLA proteins may further promote cambial growth by releasing hormonal constraints [131].

Lignin modification remains a key translational focus because lignin, while essential for structural integrity and disease resistance, complicates pulping and saccharification, and its genetic alteration may therefore involve trade-offs between improved processability and pathogen tolerance [8,62]. In P. taeda, suppression of cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase (CAD) altered lignin composition without catastrophic growth penalties [132]. Unlike angiosperms, which synthesize both guaiacyl (G) and syringyl (S) lignin, conifers produce predominantly G units. Engineering S-lignin biosynthesis has long been proposed as a strategy to reduce recalcitrance; proof-of-concept was achieved in pine tracheary elements through heterologous expression of F5H and COMT [133]. Beyond monomer biosynthesis, laccases provide opportunities to fine-tune lignin polymerization or redirect phenylpropanoid fluxes [105].

These advances, combined with protoplast-based transient assays and CRISPR/Cas genome editing [87], make it increasingly feasible to generate pine varieties optimized for both forestry productivity and industrial processing.

5.2. Stress Resilience, Adaptation, and Carbon Sequestration

Climate change demands pines that combine high productivity with resilience to environmental stresses. As dominant species of boreal and temperate forests, Pinus faces growing threats from drought, pests, pathogens, and thermal extremes. Functional genomics provides new avenues for engineering trees that maintain growth and carbon sequestration under shifting climates.

Drought tolerance: Pines employ divergent stomatal strategies to balance hydraulic safety and carbon uptake in arid environments [134]. Earlier work demonstrated that drought-induced hydraulic failure is a primary determinant of survival in conifers, with species-specific vulnerability thresholds defining mortality risk during severe water deficit [135]. Genetic manipulation of ABA signaling components, aquaporins, and stress-responsive transcription factors such as DREB, NAC, and bZIP has been shown to enhance drought tolerance and water-use efficiency across plant systems [136]. In P. massoniana, drought-responsive regulatory networks encompassing ABA signaling pathways, aquaporins, and multiple stress-associated transcription factors have been delineated [111].

Cold adaptation: Boreal species such as P. sylvestris rely on C-repeat binding factors (CBFs) and dehydrins for cold acclimation [137]. Modifying these pathways could improve frost tolerance and extend pine planting ranges northward, reinforcing carbon capture in high-latitude regions [138].

Pest and pathogen resistance: Pine wilt disease (Bursaphelenchus xylophilus) and bark beetle outbreaks highlight the need for enhanced resistance. Terpene synthase families control oleoresin production, a key defense trait in conifers [67]. Engineering resin biosynthesis or broad-spectrum recognition receptors could strengthen resilience under climate-driven pest pressures.

Carbon sequestration: Pines are among the most effective long-term carbon sinks, combining rapid growth with durable biomass. Boreal conifers maintain carbon uptake even under warming, underscoring their climate-buffering capacity [139]. Management strategies such as replanting productive conifers on shallow peat soils also enhance carbon storage, though site-specific trade-offs must be considered [140]. Genomic approaches to increase wood density, biomass accumulation, or lignin stability may further extend carbon residence times in forests and harvested products [89].

In summary, integrating stress tolerance with carbon sequestration goals will ensure that pine forestry supports both ecosystem resilience and climate change mitigation.

5.3. Genome-Wide Association Studies and Genomic Selection in Molecular Breeding of Pinus

With the rapid expansion of genomic resources, Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) and Genomic Selection (GS) have emerged as among the most successful translational applications of Pinus genomics [26,141,142]. GWAS analyses in several pine species have identified genomic regions associated with growth rate, wood density, fiber traits, and resistance to biotic and abiotic stresses, although statistical power is often constrained by long generation times, large genome size, and complex population structure [111]. In parallel, GS has been effectively implemented in breeding programs for commercially important species such as Pinus taeda, P. radiata, and P. pinaster, significantly improving selection accuracy and reducing breeding cycle duration compared to conventional phenotypic selection [26,142].

The availability of high-density SNP arrays, genotyping-by-sequencing platforms, and increasingly complete reference genomes has further strengthened GS frameworks by enabling more accurate marker anchoring, haplotype resolution, and genome-wide prediction. Importantly, GWAS and GS provide non-transgenic, regulatory-friendly routes for genetic improvement that are immediately deployable at scale. Looking forward, the integration of GWAS and GS with functional genomics, transcriptomics, and climate-response data is expected to bridge molecular mechanisms with predictive breeding, accelerating the development of high-yielding, resilient Pinus varieties for sustainable forestry and carbon sequestration.

5.4. Industrial and Bioenergy Applications

Beyond their traditional roles in timber, pulp, and paper, pines are emerging as multipurpose feedstocks for bioenergy and high-value biomaterials. Molecular engineering allows tailoring of wood chemistry to meet industrial and sustainability goals.

Pulp and paper: The G-rich lignin of pine complicates pulping, requiring high energy and chemical use. Genetic strategies to reduce lignin content or alter monomer composition can improve processability. Suppression of CAD in loblolly pine enhanced kraft pulp brightness and reduced processing costs [132]. Incorporating S-lignin through F5H expression, demonstrated in pine tracheary elements, could further improve delignification, echoing successes in hardwoods [133].

Bioenergy and biorefineries: Pine biomass is a leading candidate for lignocellulosic biofuels, though lignin recalcitrance and hemicellulose complexity limit enzymatic hydrolysis. Engineering lignin traits, together with modifications of galactoglucomannan hemicelluloses, can enhance conversion efficiency [143]. Integrated transcriptome–metabolome studies in P. taeda have identified networks regulating terpenoid and flavonoid biosynthesis [125], pathways that could be redirected for biofuel precursors. Emerging work also highlights trees as scalable producers of high-value compounds such as squalene, traditionally sourced from sharks [144]. In addition, pine trees represent promising renewable sources of diverse bioactive compounds, including phenolics and terpenoids, expanding the scope of pine biorefineries beyond energy production to high-value biochemical and nutraceutical applications [3].

Advanced biomaterials: Pine lignin is a sustainable resource for carbon fibers, adhesives, and polymers. Tailoring monomer composition and polymerization pathways may optimize yields of industrial precursors, expanding forestry’s role into high-value bio-based markets [9].

Sustainability: By integrating genetic innovations with downstream biorefinery pipelines, engineered pines can reduce chemical and energy inputs, replace petrochemical feedstocks, and serve multiple industries simultaneously. Recent reviews emphasize the feasibility of combining biomass enhancement, lignin tailoring, and metabolite engineering into single elite genotypes [145].

6. Challenges and Future Directions

Despite advances in molecular biotechnology, Pinus remains one of the most challenging genera for functional studies due to its massive genomes, low transformation efficiency, and long generation times. Thick secondary walls, resin content, and limited conifer-specific promoters further constrain reliable gene delivery and expression [146]. Overcoming these barriers will require optimized transformation systems, novel delivery platforms, and the use of developmental regulators (e.g., BBM, WUS, WOX) to enhance regeneration efficiency.

A strategic roadmap is essential to translate molecular advances into forestry practice. Future priorities should integrate tool development, systems biology, and ecological deployment.

Near-Term Priorities (Next ~5 Years):

- (1)

- Expand genomic foundations: Improve reference-quality genome assemblies across diverse Pinus species. Haplotype-resolved genomes and pan-genomes will capture allelic diversity and structural variation critical for breeding climate-resilient varieties and will enable more comprehensive functional annotation [13,14].

- (2)

- Develop functional toolkits: Establish efficient protoplast systems, stable transformation pipelines, and conifer-optimized promoters. Optimize CRISPR/Cas systems and explore novel Cas variants, viral delivery platforms, and DNA-free ribonucleoprotein delivery into meristematic tissues to enable rapid genome editing assays while bypassing stable transformation constraints.

- (3)

- Apply single-cell and multi-omics: Use single-cell transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics to map wood formation at high resolution. Integrate RNA-seq data with high-resolution wood anatomy images using deep-learning approaches, together with machine learning and GRN modeling, to directly link cell-expansion gene expression to tracheid lumen size and predict key regulators of growth and stress responses.

Mid- to Long-Term Priorities (≥10 Years):

- (1)

- Advance synthetic biology: Prioritize development of modular circuits, inducible promoters, and multigene stacking strategies. Integrate synthetic regulation with genome editing for precise control of lignin content, cellulose composition, and tracheid architecture.

- (2)

- Validate in the field: Conduct long-term trials to test growth, resilience, and genetic stability under varied environments. Combine molecular outcomes with ecological impact assessments to ensure sustainability and safety.

- (3)

- Toward predictive forestry: Integrate genomic prediction, climate modeling, and carbon accounting into forestry management. This will allow selection and deployment of Pinus genotypes optimized for both productivity and climate resilience.

This roadmap emphasizes a bench-to-forest continuum, where molecular tools, systems biology, and ecological foresight converge. By uniting discovery with application, frontier research in Pinus can generate fundamental insights while driving innovations in forestry, industry, and climate change mitigation.

7. Conclusions

Advances in genomic resources and molecular toolkits are rapidly transforming our understanding of wood formation in Pinus species (Figure 1 and Figure 3). Although conifer genomes are exceptionally large and complex, recent high-quality assemblies, transcriptome datasets, and emerging epigenomic profiles now provide a solid foundation for dissecting secondary growth. These resources have enabled the identification of conifer-specific regulators and the reconstruction of gene networks controlling phenylpropanoid metabolism, cellulose and hemicellulose biosynthesis, and lignin polymerization.

A central insight from recent studies is the conservation yet diversification of the NAC–MYB regulatory cascade, which governs SCW deposition. In Pinus, lineage-specific expansions of NACs, R2R3-MYBs, and oxidative enzymes such as laccases contribute to tracheid-based xylem development and to the formation of compression wood under mechanical stress. Hormonal pathways—including auxin, gibberellin, and ethylene—integrate environmental signals with these transcriptional modules to modulate tracheid morphology and lignin composition.

Despite these advances, functional studies remain constrained by low transformation efficiency, long generation times, and limited conifer-specific promoters. Emerging tools—including protoplast-based assays, transient expression, CRISPR/Cas editing, and synthetic promoter engineering—provide promising avenues to overcome these bottlenecks. Integrating such tools with multi-omics approaches, including single-cell and spatial transcriptomics, will be essential for establishing conifer-specific regulatory models and for linking gene function with traits relevant to biomass production, stress resilience, and carbon sequestration.

Author Contributions

H.-A.J., S.-W.P. and J.-H.K. conceptualized the study; H.-A.J., S.-W.P., Y.-I.C., H.L. and J.-H.K. performed the literature search and analysis; H.-A.J., S.-W.P., E.-K.B. and J.-H.K. wrote the manuscript; E.-K.B. and J.-H.K. supervised the study. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) (RS-2023-NR076519), funded by the Korea government (MSIT), and the R&D Program for Forest Science Technology (2023489B10-2325-AA01) provided by the Korea Forest Service (Korea Forestry Promotion Institute).

Data Availability Statement

All data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the funding agencies, including the National Research Foundation of Korea (RS-2023-NR076519), National Institute of Forest Science (FG0603-2021-01-2025) and the Korea Forest Service (2023489B10-2325-AA01).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Christenhusz, M.J.M.; Reveal, J.L.; Farjon, A.; Gardner, M.F.; Mill, R.R.; Chase, M.W. A New Classification and Linear Sequence of Extant Gymnosperms. Phytotaxa 2011, 70, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gernandt, D.S.; Geada López, G.; Ortiz García, S.; Liston, A. Phylogeny and Classification of Pinus. Taxon 2005, 54, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziedziński, M.; Kobus-Cisowska, J.; Stachowiak, B. Pinus Species as Prospective Reserves of Bioactive Compounds with Potential Use in Functional Food-Current State of Knowledge. Plants 2021, 10, 1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.; Ball, J. World View of Plantation Grown Wood. In FAO Forestry Working Paper; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 1999; 12p. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y.; Birdsey, R.A.; Phillips, O.L.; Jackson, R.B. The Structure, Distribution, and Biomass of the World’s Forests. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2013, 44, 593–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.T.; Bae, E.K.; Tran, T.N.A.; Lee, H.; Ko, J.H. Exploring the Seasonal Dynamics and Molecular Mechanism of Wood Formation in Gymnosperm Trees. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borthakur, D.; Busov, V.; Cao, X.H.; Du, Q.; Gailing, O.; Isik, F.; Ko, J.H.; Li, C.; Li, Q.; Niu, S.; et al. Current Status and Trends in Forest Genomics. For. Res. 2022, 2, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farjon, A. The Kew Review Conifers of the World. Kew Bull. 2018, 73, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragauskas, A.J.; Beckham, G.T.; Biddy, M.J.; Chandra, R.; Chen, F.; Davis, M.F.; Davison, B.H.; Dixon, R.A.; Gilna, P.; Keller, M.; et al. Lignin Valorization: Improving Lignin Processing in the Biorefinery. Science 2014, 344, 1246843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.T.T.; Kim, M.H.; Park, E.J.; Lee, H.; Ko, J.H. Seasonal Developing Xylem Transcriptome Analysis of Pinus densiflora Unveils Novel Insights for Compression Wood Formation. Genes 2023, 14, 1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovach, A.; Wegrzyn, J.L.; Parra, G.; Holt, C.; Bruening, G.E.; Loopstra, C.A.; Hartigan, J.; Yandell, M.; Langley, C.H.; Korf, I.; et al. The Pinus taeda Genome Is Characterized by Diverse and Highly Diverged Repetitive Sequences. BMC Genom. 2010, 11, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.H.; Cho, J.S.; Tran, T.N.A.; Nguyen, T.T.T.; Park, E.J.; Im, J.H.; Han, K.H.; Lee, H.; Ko, J.H. Comparative functional analysis of PdeNAC2 and AtVND6 in the tracheary element formation. Tree Physiol. 2023, 43, 1201–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, D.M. (Ed.) Ecology and Biogeography of Pinus; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998; pp. 1–527. [Google Scholar]

- Zimin, A.; Stevens, K.A.; Crepeau, M.W.; Holtz-Morris, A.; Koriabine, M.; Marçais, G.; Puiu, D.; Roberts, M.; Wegrzyn, J.L.; de Jong, P.J.; et al. Sequencing and Assembly of the 22-Gb Loblolly Pine Genome. Genetics 2014, 196, 875–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wegrzyn, J.L.; Liechty, J.D.; Stevens, K.A.; Wu, L.S.; Loopstra, C.A.; Vasquez-Gross, H.A.; Dougherty, W.M.; Lin, B.Y.; Zieve, J.J.; Martínez-García, P.J.; et al. Unique Features of the Loblolly Pine (Pinus taeda L.) Megagenome Revealed through Sequence Annotation. Genetics 2014, 196, 891–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohri, D. Karyotype evolution in conifers. Feddes Repert. 2021, 132, 232–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, M.J.; Cho, H.J.; Park, Y.S.; Lee, H.Y.; Bae, E.K.; Jung, S.; Jin, H.; Woo, J.; Park, E.; Kim, S.J.; et al. Haplotype-resolved genome assembly and resequencing analysis provide insights into genome evolution and allelic imbalance in Pinus densiflora. Nat. Genet. 2024, 56, 2551–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neale, D.B.; Wegrzyn, J.L.; Stevens, K.A.; Zimin, A.V.; Puiu, D.; Crepeau, M.W.; Cardeno, C.; Koriabine, M.; Holtz-Morris, A.E.; Liechty, J.D.; et al. Decoding the Massive Genome of Loblolly Pine Using Haploid DNA and Novel Assembly Strategies. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, R59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, K.A.; Wegrzyn, J.L.; Zimin, A.; Puiu, D.; Crepeau, M.; Cardeno, C.; Paul, R.; Gonzalez-Ibeas, D.; Koriabine, M.; Holtz-Morris, A.E.; et al. Sequence of the Sugar Pine Megagenome. Genetics 2016, 204, 1613–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperry, J.S. Evolution of water transport and xylem structure. Int. J. Plant Sci. 2003, 164, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.T.; Kim, M.H.; Pyo, S.W.; Jang, H.A.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, D.G.; Ko, J.H. A Comprehensive Analysis of the Laccase Gene Family of Pinus densiflora Reveals a Functional Role of PdeLAC28 in Lignin Biosynthesis for Compression Wood Formation. Forests 2024, 15, 2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Xu, H.; Guo, Y.; Grünhofer, P.; Schreiber, L.; Lin, J.; Li, R. Transcriptomic and epigenomic remodeling occurs during vascular cambium periodicity in Populus tomentosa. Hortic. Res. 2021, 8, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagle, M.; Déjardin, A.; Pilate, G.; Strauss, S.H. Opportunities for Innovation in Genetic Transformation of Forest Trees. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.T.T.; Choi, N.Y.; Pyo, S.W.; Choi, Y.I.; Ko, J.H. Optimized and Reliable Protoplast Isolation for Transient Gene Expression Studies in the Gymnosperm Tree Species Pinus densiflora. Forests 2025, 16, 1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralph, S.G.; Chun, H.J.E.; Kolosova, N.; Cooper, D.; Oddy, C.; Ritland, C.E.; Kirkpatrick, R.; Moore, R.; Barber, S.; Holt, R.A.; et al. A Conifer Genomics Resource of 200,000 Spruce (Picea spp.) ESTs and 6,464 High-Quality, Sequence-Finished Full-Length cDNAs for Sitka Spruce (Picea sitchensis). BMC Genom. 2008, 9, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, M.; Lauer, E.; Bennett, J.; Zaman, S.; McEvoy, S.; Acosta, J.; Jackson, C.; Townsend, L.; Eckert, A.; Whetten, R.W.; et al. Toward genomic selection in Pinus taeda: Integrating resources to support array design in a complex conifer genome. Appl. Plant Sci. 2021, 9, e11439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, E.V.; DeSilva, R.; Canning, C.; Wright, J.W. Testing source elevation versus genotype as predictors of sugar pine performance in a post-fire restoration planting. Ecosphere 2024, 15, e70010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carey, C.J.; Glassman, S.I.; Bruns, T.D.; Aronson, E.L.; Hart, S.C. Soil microbial communities associated with giant sequoia: How does the world’s largest tree affect some of the world’s smallest organisms? Ecol. Evol. 2020, 10, 6593–6609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Jiao, L.; Wang, J.; Ma, L.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, J.; Yin, Y. Analyses of high spatial resolution datasets identify genes associated with multi-layered secondary cell wall thickening in Pinus bungeana. Ann. Bot. 2024, 133, 953–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.; Wang, P.; Chen, X.; Zhao, H.; Zhu, Q.; Song, Y.; Nie, Y.; Li, Y.; Guo, M.; Niu, S. An ethylene-induced NAC transcription factor acts as a multiple abiotic stress responsor in conifer. Hortic. Res. 2023, 10, uhad130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, B.; Li, S.; Qi, J.; Yang, L.; Yin, D.; Sun, S. Integrated transcriptomic and metabolic analyses reveal the early response mechanism of Pinus tabulaeformis to pine wood nematodes. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Sun, T.; Liu, J.; Zhang, R.; Yu, Y.; Zhou, G.; Liu, J.; Gao, B. The Key Role of Plant Hormone Signaling Transduction and Flavonoid Biosynthesis Pathways in the Response of Chinese Pine (Pinus tabuliformis) to Feeding Stimulation by Pine Caterpillar (Dendrolimus tabulaeformis). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sturrock, S.; Frickey, T.; Freeman, J.; Butler, J.; Fritsche, S.; Gea, P.; Graham, N.; Macdonald, L.; Mercier, C.; Paget, M.; et al. Pinus radiata genome reveals a downward demographic trajectory and opportunities for genomics-assisted breeding. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2025, 15, jkaf125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addison, S.L.; Mendoza, L.L.; Rúa, M.A.; Clinton, P.W.; Wakelin, S.A. A genotype-by-sequencing dataset and identity-by-state matrix of genetic variation in 821 Pinus radiata trees from 16 counties. Data Brief 2025, 63, 112123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokipii-Lukkari, S.; Delhomme, N.; Schiffthaler, B.; Mannapperuma, C.; Prestele, J.; Nilsson, O.; Street, R.; Tuominen, H. Transcriptional Roadmap to Seasonal Variation in Wood Formation of Norway Spruce. Plant Physiol. 2018, 176, 2851–2870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.; Zhao, W.; Wennström, U.; Andersson Gull, B.; Wang, X.R. Parentage and relatedness reconstruction in Pinus sylvestris using genotyping-by-sequencing. Heredity 2020, 124, 633–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishcherikova, V.; Lynikienė, J.; Marčiulynas, A.; Gedminas, A.; Prylutskyi, O.; Marčiulynienė, D.; Menkis, A. Biogeography of Fungal Communities Associated with Pinus sylvestris L. and Picea abies (L.) H. Karst. along the Latitudinal Gradient in Europe. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolgosheina, E.V.; Mardis, E.R.; Unrau, P.J. Conifers have a unique small RNA silencing signature. RNA 2008, 14, 1490–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hori, C.; Gaskell, J.; Cullen, D.; Sabat, G.; Stewart, P.E.; Lail, K.; Peng, Y.; Barry, K.; Grigoriev, I.V.; Kohler, A.; et al. Multi-omic Analyses of Extensively Decayed Pinus contorta Reveal Expression of a Diverse Array of Lignocellulose-Degrading Enzymes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, e01133-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parchman, T.L.; Geist, K.S.; Grahnen, J.A.; Benkman, C.W.; Buerkle, C.A. Transcriptome sequencing in an ecologically important tree species: Assembly, annotation, and marker discovery. BMC Genom. 2010, 11, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plomion, C.; Pionneau, C.; Brach, J.; Costa, P.; Baillères, H. Compression Wood-Responsive Proteins in Developing Xylem of Maritime Pine (Pinus pinaster Ait.). Plant Physiol. 2000, 123, 959–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez-Escribano, L.; Morales Clemente, M.T.; Fariña-Flores, D.; Raposo, R. A delayed response in phytohormone signaling and production contributes to pine susceptibility to Fusarium circinatum. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero-Pau, J.; Pérez-Oliver, M.A.; Rodríguez-Cuesta, Á.; Arrillaga, I.; Sales, E. Temperature-induced variation in the transcriptome of maritime pine (Pinus pinaster Ait.) embryogenic masses modulates the phenotype of the derived plants. BMC Genom. 2025, 26, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.J.; Sniezko, R.A.; Sturrock, R.N.; Chen, H. Western white pine SNP discovery and high-throughput genotyping for breeding and conservation applications. BMC Plant Biol. 2014, 14, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.J.; Sturrock, R.N.; Sniezko, R.A.; Williams, H.; Benton, R.; Zamany, A. Transcriptome analysis of the white pine blister rust pathogen Cronartium ribicola: De novo assembly, expression profiling, and identification of candidate effectors. BMC Genom. 2015, 16, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.J.; Fernandes, H.; Zamany, A.; Sikorski, M.; Jaskolski, M.; Sniezko, R.A. In-vitro anti-fungal assay and association analysis reveal a role for the Pinus monticola PR10 gene (PmPR10-3.1) in quantitative disease resistance to white pine blister rust. Genome 2021, 64, 693–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Chen, P.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, D.; Liu, J.; Hao, Q.; Ji, K. PmMYB4, a Transcriptional Activator from Pinus massoniana, Regulates Secondary Cell Wall Formation and Lignin Biosynthesis. Forests 2021, 12, 1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, Z.; Ju, S.; Liu, X.; Li, G.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Li, M. Transcriptomic and metabolomic insights into pine wood nematode resistance mechanisms in Pinus massoniana. Tree Physiol. 2025, 45, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Tu, J.; Wang, H.; Xu, Y.; Wu, F. Transcriptomic and targeted metabolomic unravelling the molecular mechanism of sugar metabolism regulating heteroblastic changes in Pinus massoniana seedlings. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 203, 108029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Li, Z.; Fan, F.; Qin, H.; Ding, G. Effects of exogenous GA3 on stem secondary growth of Pinus massoniana seedlings. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 206, 108254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Qin, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Feng, Y.; Tan, J.; Chen, X.; Hu, L.; Xie, J.; Xie, J.; et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly of Pinus massoniana provides insights into conifer adaptive evolution. GigaScience 2025, 14, giaf056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullington, L.S.; Lekberg, Y.; Sniezko, R.; Larkin, B. The influence of genetics, defensive chemistry and the fungal microbiome on disease outcome in whitebark pine trees. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2018, 19, 1847–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.J.; Sniezko, R.; Murray, M.; Wang, N.; Chen, H.; Zamany, A.; Sturrock, R.N.; Savin, D.; Kegley, A. Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Whitebark Pine (Pinus albicaulis Engelm.) in Western North America. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0167986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, P.; Li, P.; Zhang, X.; Li, H.; Ma, S.; Zong, D.; He, C. Comparative Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Analyses of Differences in Trunk Spiral Grain in Pinus yunnanensis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Xu, J.; Cai, N.; Xu, Y. Analysis of the molecular mechanism endogenous hormone regulating axillary bud development in Pinus yunnanensis. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Pan, Z.; Chen, L.; Chen, S.; Tang, J.; Cai, N.; Wang, X.; Xu, Y. Integrating analysis of nutrient elements, endogenous phytohormones, and transcriptomics reveals factors influencing variation of growth in height in Pinus yunnanensis Franch. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 223, 109866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, M.; Cai, K.; Liu, L.; Han, R.; Pei, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, X. Phytohormone biosynthesis and transcriptional analyses provide insight into the main growth stage of male and female cones Pinus koraiensis. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1273409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, M.; Xiong, C. Spatial specificity of metabolism regulation of abscisic acid-imposed seed germination inhibition in Korean pine (Pinus koraiensis sieb et zucc). Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1417632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Zhang, J.; Ye, L.; Liu, N.; Wang, F. Methyl jasmonate induced tolerance effect of Pinus koraiensis to Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Pest Manag. Sci. 2025, 81, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinosio, S.; González-Martínez, S.C.; Bagnoli, F.; Cattonaro, F.; Grivet, D.; Marroni, F.; Lorenzo, Z.; Pausas, J.G.; Verdú, M.; Vendramin, G.G. First insights into the transcriptome and development of new genomic tools of a widespread circum-Mediterranean tree species, Pinus halepensis Mill. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2014, 14, 846–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, H.; Doron-Faigenboim, A.; Kelly, G.; Bourstein, R.; Attia, Z.; Zhou, J.; Moshe, Y.; Moshelion, M.; David-Schwartz, R. Transcriptome analysis of Pinus halepensis under drought stress and during recovery. Tree Physiol. 2018, 38, 423–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nystedt, B.; Street, N.R.; Wetterbom, A.; Zuccolo, A.; Lin, Y.C.; Scofield, D.G.; Vezzi, F.; Delhomme, N.; Giacomello, S.; Alexeyenko, A.; et al. The Norway Spruce Genome Sequence and Conifer Genome Evolution. Nature 2013, 497, 579–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimin, A.V.; Stevens, K.A.; Crepeau, M.W.; Puiu, D.; Wegrzyn, J.L.; Yorke, J.A.; Langley, C.H.; Neale, D.B.; Salzberg, S.L. An Improved Assembly of the Loblolly Pine Mega-Genome Using Long-Read Single-Molecule Sequencing. Gigascience 2017, 6, giw016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S.; Li, J.; Bo, W.; Yang, W.; Zuccolo, A.; Giacomello, S.; Chen, X.; Han, F.; Yang, J.; Song, Y.; et al. The Chinese Pine Genome and Methylome Unveil Key Features of Conifer Evolution. Cell 2022, 185, 204–217.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.Q.; Ran, J.H. Evolution and Biogeography of Gymnosperms. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2014, 75, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, S.; Tan, T.; Wu, D.; Li, C.; Jing, H.; Wu, J. Seasonal Variations in Carbon, Nitrogen, and Phosphorus of Pinus Yunnanenis at Different Stand Ages. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1107961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeling, C.I.; Bohlmann, J. Genes, Enzymes and Chemicals of Terpenoid Diversity in the Constitutive and Induced Defence of Conifers against Insects and Pathogens. New Phytol. 2006, 170, 657–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokipii-Lukkari, S.; Sundell, D.; Nilsson, O.; Hvidsten, T.R.; Street, N.R.; Tuominen, H. NorWood: A gene expression resource for evo-devo studies of conifer wood development. New Phytol. 2017, 216, 482–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenz, W.W.; Ayyampalayam, S.; Bordeaux, J.M.; Howe, G.T.; Jermstad, K.D.; Neale, D.B.; Rogers, D.L.; Dean, J.F.D. Conifer DBMagic: A database housing multiple de novo transcriptome assemblies for 12 diverse conifer species. Tree Genet. Genomes 2012, 8, 1477–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.H.; Tran, T.N.A.; Cho, J.S.; Park, E.J.; Lee, H.; Kim, D.G.; Hwang, S.; Ko, J.H. Wood Transcriptome Analysis of Pinus densiflora Identifies Genes Critical for Secondary Cell Wall Formation and NAC Transcription Factors Involved in Tracheid Formation. Tree Physiol. 2021, 41, 1289–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Sun, Y.H.; Amerson, H.; Chiang, V.L. MicroRNAs in Loblolly Pine (Pinus taeda L.) and Their Association with Fusiform Rust Gall Development. Plant J. 2007, 51, 1077–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, D.; Pan, X.; Wilson, I.W.; Li, F.; Liu, M.; Teng, W.; Zhang, B. High Throughput Sequencing Technology Reveals That the Taxoid Elicitor Methyl Jasmonate Regulates MicroRNA Expression in Chinese Yew (Taxus chinensis). Gene 2009, 436, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedon, F.; Grima-Pettenati, J.; Mackay, J. Conifer R2R3-MYB transcription factors: Sequence analyses and gene expression in wood-forming tissues of white spruce (Picea glauca). BMC Plant Biol. 2007, 7, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ausin, I.; Feng, S.; Yu, C.; Liu, W.; Kuo, H.Y.; Jacobsen, E.L.; Zhai, J.; Gallego-Bartolome, J.; Wang, L.; Egertsdotter, U.; et al. DNA methylome of the 20-gigabase Norwayspruce genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E8106–E8113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, P.; Hsieh, J.-W.A.; Kao, C.-T.; Hu, C.-W.; Wang, R.; Kuo, S.-C.; Yen, M.-R.; Liou, P.-C.; Ho, Y.-C.; Chu, C.-C.; et al. Single-cell and spatial omics reveal progressive loss of xylem developmental complexity across seed plants. Plant Cell 2025, 37, koaf253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trontin, J.-F.; Klimaszewska, K.; Morel, A.; Hargreaves, C.; Lelu-Walter, M.-A. Molecular aspects of conifer zygotic and somatic embryo development: A review of genome-wide approaches and recent insights. Tree Genet. Genomes 2016, 12, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, C.; Grace, L.J. Somatic embryogenesis and genetic transformation in Pinus radiata. In Protocol for Somatic Embryogenesis in Woody Plants; Forestry Sciences; Jain, S.M., Gupta, P.K., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2005; Volume 77, pp. 363–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charity, J.A.; Holland, L.; Grace, L.J.; Walter, C.; McInnis, S.; Klimaszewska, K.; Caron, S.; Rutledge, R.G. Regeneration of Pinus radiata plants from embryogenic tissue: Improvement of protocols. Plant Cell Rep. 2005, 24, 606–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loopstra, C.A.; Stomp, A.M.; Sederoff, R.R. Agrobacterium-mediated DNA transfer in sugar pine. Plant Mol. Biol. 1990, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, W.; Sederoff, R.; Whetten, R. Regeneration of transgenic loblolly pine (Pinus taeda L.) from zygotic embryos transformed with Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Planta 2001, 213, 981–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, S.D.; Cho, Y.H.; Sheen, J. Arabidopsis mesophyll protoplasts: A versatile cell system for transient gene expression analysis. Nat. Protoc. 2007, 2, 1565–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Puryear, J.; Cairney, J. A simple and efficient method for isolating RNA from pine trees. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 1993, 11, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germain, H.; Lachance, D.; Pelletier, G.; Fossdal, C.G.; Solheim, H.; Séguin, A. The expression pattern of the Picea glauca Defensin 1 promoter is maintained in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 2012, 63, 785–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddenberg, D.; Akhter, S.; Ramachandran, P.; Sundström, J.F.; Carlsbecker, A. Sequenced genomes and rapidly emerging technologies pave the way for conifer evolutionary developmental biology. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Chen, J.; Pi, X.; Huang, L.-J.; Li, N. Isolation, Purification, and Application of Protoplasts and Transient Expression Systems in Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasamoto, H.; Ogita, S. Endogenous Plant Hormones in Protoplasts of Embryogenic Cells of Conifers. Prog. Biotechnol. 2001, 18, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poovaiah, C.; Phillips, L.; Geddes, B.; Reeves, C.; Sorieul, M.; Rhorlby, G. Genome editing with CRISPR/Cas9 in Pinus radiata (D. Don). BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]