Abstract

Street trees are vital components of urban ecosystems, contributing to air purification, microclimate regulation, and visual landscape enhancement. Thus, accurate segmentation of individual trees from point clouds is an essential task for effective urban green space management. However, existing methods often struggle with noise, crown overlap, and the complexity of street environments. To address these challenges, this paper introduces a multi-constraint and shortest path optimization method for individual urban street tree segmentation from point clouds. In this paper, object primitives are first generated using multi-constraints based on graph segmentation. Subsequently, trunk points are identified and associated with their corresponding crowns through structural cues. To further improve the robustness of the proposed method under dense and cluttered conditions, the shortest-path optimization and stem-axis distance analysis techniques are proposed to further refine the individual tree extraction results. To evaluate the performance of the proposed method, the WHU-STree benchmark dataset is utilized for testing. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method achieves an average F1-score of 0.768 and coverage of 0.803, outperforming superpoint graph structure single-tree classification (SSSC) and nyström spectral clustering (NSC) methods by 17.4% and 43.0%, respectively. The comparison of visual individual tree segmentation results also indicates that the proposed framework offers a reliable solution for street tree detection in complex urban scenes and holds practical value for advancing smart city ecological management.

1. Introduction

With the rapid development of Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) technology, vehicle-mounted systems have enabled efficient acquisition of 3D point-cloud information for street trees [1,2,3]. As a vital element of the urban landscape, street trees significantly contribute to air purification, noise reduction, and the enhancement of ecological quality [4,5,6]. In the context of urban forest resource surveys and greening management, acquiring precise structural parameters of individual trees holds immense importance for comprehending urban forest dynamics and facilitating refined management and decision making processes [7,8,9,10,11]. Individual tree segmentation constitutes a crucial aspect of forest resource surveys [12,13,14]. Nevertheless, owing to acquisition configurations and the occlusion among trees, bottom–up LiDAR scanning frequently fails to capture the upper canopy, whereas top–down acquisition encounters difficulties in obtaining lower structural details, thereby rendering high-precision individual segmentation challenging to achieve [15,16,17]. Consequently, devising an individual tree segmentation method capable of adapting to complex street environments and diverse acquisition strategies bears significant theoretical and practical value.

Currently, existing segmentation methods for vehicle-mounted LiDAR primarily concentrate on trunk-based or crown-based approaches. Trunk-based methods typically identify trunk geometry as seed points and conduct clustering through projection or region growing strategies [18,19,20,21]. For example, Mongus et al. [20] pinpointed vertically oriented points within the middle and lower layers of the tree trunk and employed local fitting surfaces to detect concave regions in the vicinity of the trunk. Cabo et al. [21] introduced an automatic trunk identification method, which leverages the independence and vertical continuity of the trunk to identify and extract trunk points, subsequently facilitating the segmentation of individual trees. Zhang et al. [22] utilized hierarchical gridding for data analysis, integrating the features of point cloud elevation distribution and point cloud density, and applied the region growing algorithm to accomplish the segmentation of individual trees. Li et al. [23] proposed a hierarchical clustering method based on trunk-branch constraints to extract individual trees directly from LiDAR point clouds.

Crown-based approaches regard the treetop or crown structure as the pivotal feature for tree identification [24,25,26,27]. For example, Zhen et al. [28] initially employed the dynamic window local maximum method to pinpoint the locations of individual trees and subsequently utilized the label-controlled region growth method to demarcate the tree crown boundaries of the detected individual trees. However, this method demonstrates subpar performance in segmenting targets within complex scenes and when dealing with missing street tree crowns. Koch et al. [27] applied filters to locate the tree tops and segment the canopies of both coniferous and broad-leaved trees. They also used the lower limit of the tree height and canopy width regression curve to determine the size of the local maximum search window. Nevertheless, inherent errors and uncertainties are present during the generation of the canopy height model. Hui et al. [28] introduced a multi-level adaptive individual tree segmentation hybrid model that amalgamates the advantages of CHM (canopy height model)-based and 3D points-based methods. This approach first acquires initial tree detection results through the CHM based method and then employs the 3D points to optimize tree clustering. This paper also automatically estimates the canopy width and scale, integrating multi-scale segmentation results to fully leverage the benefits of different scales, thereby completing individual tree segmentation. Hua et al. [29] utilized adjacent roadside trees with overlapping canopies to first isolate the tree canopy region using a binary classifier. Subsequently, they calculated the optimal projection from the 3D point clouds to the two-dimensional image, corresponding to the scenario where the pixel overlap of a individual tree image is minimized.

To sum up, although substantial progress has been achieved in segmenting individual street trees from vehicle-mounted LiDAR point clouds, a notable research gap persists in achieving accurate and generalizable individual tree segmentation across complex urban environments. This gap endures due to the following three unresolved issues:

- Data-quality issues stemming from real-world acquisition conditions, such as noise, missing points, and occlusions caused by buildings or vehicles, frequently result in incomplete trunk or crown structures. This incomplete information significantly diminishes segmentation accuracy.

- Algorithmic limitations persist in crown-based methods. Approaches that rely on CHMs, dynamic windows, or region growing are highly sensitive to crown overlap or crown loss, often leading to over-segmentation or under-segmentation.

- Many existing methods perform well only in specific road scenarios or for particular tree species, but their robustness markedly decreases when applied across different cities, vegetation compositions, or LiDAR sampling densities. This lack of universality restricts their applicability in diverse urban environments.

To tackle these challenges, this study aims to develop an urban individual tree segmentation method based on multi-constraint joint shortest path analysis. The primary contributions are as follows:

- Enhancing robustness to noise and incomplete structures. A graph-based object-primitive segmentation approach is first introduced to establish a stable structural foundation. This step mitigates the influence of noise, missing points, and occlusions, ensuring that the subsequent segmentation process can operate reliably even when the point cloud is partially incomplete.

- Improving trunk identification under crown overlap or loss. A multi-constraint trunk extraction strategy is then devised by integrating tree-vertex information, aspect-ratio constraints, and linear-feature characteristics. This design facilitates accurate trunk detection even when crown data are missing or heavily overlapped, thereby reducing both over-segmentation and under-segmentation that commonly plague crown-based methods.

- Strengthening generalization across diverse environments and datasets. Shortest-path analysis is combined with point-to-stem-axis distance to associate crown points with their correct trunks. This mechanism enhances segmentation reliability across different road conditions, tree species, and LiDAR acquisition densities, thereby improving the overall generalization capability of the method.

2. Methodology

In general, ground point clouds can compromise the extraction accuracy of roadside trees. To address this, this paper initially employs Cloth Simulation Filter (CSF) [30] to effectively separate ground points from non-ground points, and constructs a digital terrain model (DTM) based on ground points to normalize the point cloud. Subsequently, to enhance computational efficiency, the point clouds below 2.5 m from the ground level are extracted and voxelized, and the influence of low shrub point clouds is eliminated by combining point density and height difference thresholds. Finally, cluster analysis is performed on the remaining point clouds to separate tree trunk point cloud clusters and remove small-scale noise clusters, thereby reducing the complexity of subsequent point cloud segmentation and improving overall the implementation efficiency.

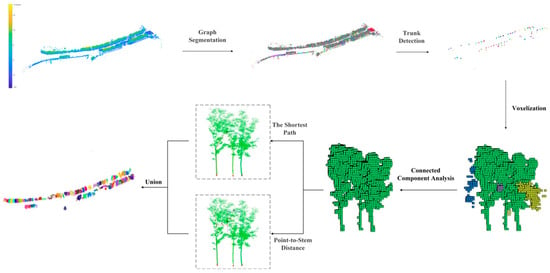

Following the aforementioned point cloud preprocessing, this paper proposes a graph segmentation method to construct a network structure towards the non-ground points as shown in Figure 1. This network structure is then integrated with multiple proposed constraints to segment the point cloud and obtain object primitives. Next, tree trunk point clouds and root nodes are extracted based on the spatial features of the object primitives. By calculating the spatial features (including linear features and aspect ratio features) of each object primitive and combining them with tree vertex constraints, point cloud clusters that conform to the trunk features are selected, and root nodes are further located and extracted. Subsequently, connectivity analysis is performed on the preliminary tree trunk point cloud to obtain a complete tree point cloud. Then, combining shortest path analysis and point-to-stem axis distance constraints, the tree point cloud is optimized and segmented, ultimately yielding a structurally complete and independent street tree point cloud. This approach preserves the integrity of the overall tree structure while effectively suppressing noise interference. Overall, the methodology presented in this paper mainly includes the following three steps: (1) Object primitive acquisition based on graph segmentation. (2) Tree trunk point cloud extraction and root node identification based on the spatial features of object primitives. (3) Individual tree point cloud segmentation based on shortest path and point-to-stem axis distance.

Figure 1.

The flowchart of the proposed method. The final results of individual tree segmentation are rendered in different colors.

2.1. Object Primitive Acquisition Based on Graph Segmentation

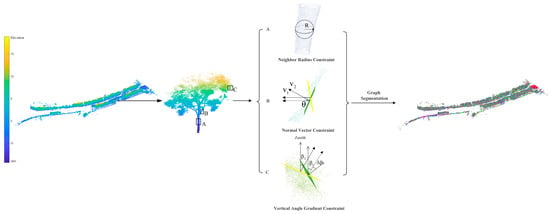

To effectively extract tree trunk point clouds, this study initially employs a graph segmentation approach. The algorithm is based on the geometric primitive segmentation principle [31]. Specifically, a neighborhood graph is constructed as expressed in Equation (1), where each point is treated as a node, and edges are established according to spatial proximity within an adaptive neighborhood radius . Three geometric constraints as shown in Figure 2, namely the neighborhood radius, the deviation of the normal vector angle, and the rate of change in the vertical angle, control the connection weights between nodes. An edge is retained only when all constraint thresholds are satisfied, ensuring that points with similar local geometric properties belong to the same primitive. Subsequently, connected component analysis is performed on the graph to derive object primitives representing homogeneous geometric elements such as trunks, branches, or crown surfaces. Through this process, non-ground points are segmented into object primitives with similar spatial characteristics.

where represents the network structure, is the set of vertices () that constitute the network, is a collection of edges (). is composed of all the points (, ) in the point cloud, is the edge formed by any two points (, ).

Figure 2.

Constraints for graph segmentation. In this figure, ‘A’ represents the neighborhood radius constraint. is the neighborhood radius. ‘B’ represents the normal vector angle constraint, where θ is the angle between the normal vectors and of two neighboring points. And ‘C’ is the vertical angle change rate constraint, where is the change in the vertical angles and between two neighboring points. The right segmentation results are rendered in different colors.

To further clarify the definition of edge weights in the graph segmentation, this study adopts a constraint-based elimination mechanism. During the construction of the neighborhood graph, each potential edge between two nodes is first evaluated under three geometric constraints: the neighborhood radius, the normal vector angular deviation, and the vertical angle change rate. An edge is retained only when all constraints simultaneously satisfy their respective thresholds; otherwise, the edge is directly removed from the graph. This strategy simplifies the weighting process and prevents the introduction of biased cost terms arising from heterogeneous geometric measures. As a result, the retained edges represent stable spatial relationships between points with consistent geometric features, ensuring that subsequent connected component analysis can effectively form object primitives corresponding to homogeneous structures.

Regarding the neighborhood radius constraint, to prevent interference from long edges on the network graph segmentation, this paper uses the neighborhood radius to restrict the connection relationship between point pairs. The neighborhood radius is obtained by randomly selecting n points in the point cloud and calculating the average maximum distance of their respective k nearest neighbors, where the number of neighboring points k is typically set to 10 [32]. The calculation of the neighborhood radius is illustrated in Equation (2).

where represents the neighborhood radius. represents the maximum distance between the i-th random point and its neighbors. The neighborhood radius can be adaptively adjusted to suit the density and spatial distribution of different point cloud data, thereby improving the automation level of the algorithm.

With regard to the constraint concerning the normal vector angle, to ensure that the points within an object primitive exhibit similar spatial geometric features, this paper calculates the normal vector angle between each point and its adjacent point, and establishes an angle threshold. The calculation of the normal vector angle is presented in Equation (3):

where θ represents the angle of the normal vector. , are the normal vectors of two adjacent nodes, respectively. Typically, the angle between the normal vectors of features such as tree trunks and buildings is relatively small, while the angle between the normal vectors of tree canopies and low vegetation is larger due to their scattered distribution. Therefore, the consistency of normal vectors can be used to segment these features into different object primitives.

Regarding the constraint on the vertical angle change rate, given that tree trunks typically exhibit a columnar shape, relying solely on the normal vector angle threshold may result in under-segmentation. To further enhance the accuracy of tree trunk point cloud extraction, this paper introduces the vertical angle change rate, which characterizes the rate of change in the angle between the normal vector of a point and those of its neighboring points relative to the z-axis. The calculation formula is presented in Equation (4):

where is the difference in vertical angle between the point and those of its neighboring points, and is the number of neighboring points connected to the point. Neighboring points with a small rate of change in vertical angle, such as tree trunks and building points, can be segmented into the same object primitive, while points with a larger rate of change, such as tree crowns, can be segmented into multiple smaller object primitives.

Under the combined influence of the aforementioned three constraints, the point cloud is segmented into several object primitives, with the tree trunk primitives among them offering a dependable basis for subsequent tree trunk point cloud extraction. To present a clearer overview of the segmentation workflow, the detailed procedure for constructing the neighborhood graph and extracting object primitives is summarized in the algorithm, and the corresponding pseudocode for acquiring object primitives is provided in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: The pseudocode of object primitive acquisition based on graph segmentation | |||

| Input: Point Cloud , Neighbor count , Thresholds | |||

| 1 Initialize Graph ; 2 Calculate Adaptive Neighborhood Radius ; | |||

| 3 Select random points from ; | |||

| 4 for point do | |||

| 5 | Find nearest neighbors of | ||

| 6 | Calculate Vertical Angle Change Rate | ||

| 7 | for point do | ||

| 8 | Calculate Euclidean distance | ||

| 9 | Calculate Normal Vector Angle : | ||

| 10 | if and and | ||

| 11 | Add edge to | ||

| 12 | end | ||

| 13 | end | ||

| 14 end 16 Graph Segmentation: | |||

| 17 Connected Components | |||

| 18 Output: Set of Object Primitives | |||

2.2. Tree Trunk Point Cloud Extraction and Root Node Identification Based on Object Primitive Spatial Features

After conducting threshold segmentation on the point cloud and acquiring the object primitive, this paper proceeds to identify object primitives based on the geometric features of the tree trunk to further extract the tree trunk point cloud. The tree trunk manifests as an independent cylinder, with its spatial features primarily marked by pronounced linearity and a substantial aspect ratio. Consequently, this paper analyzes the tree trunk from two perspectives, namely linearity and aspect ratio.

2.2.1. Linear Feature Extraction

The linear characteristics of the object primitive are obtained by calculating the eigenvalues of its covariance matrix, as illustrated in Equation (5):

where is the eigenvalue of the object primitive covariance matrix, . The magnitude of the eigenvalue reflects the degree of dispersion of the point cloud in the corresponding direction. Taking a single plant as an example, compared to the canopy point cloud, the eigenvalue of the trunk and branches is notably larger than . Consequently, the trunk and branches usually have higher linear values, whereas the canopy displays lower linear values.

2.2.2. Aspect Ratio Feature Extraction

To further differentiate tree trunks from other non-ground objects, this paper incorporates the aspect ratio feature of object primitives. Tree trunks are generally tall and slender cylinders, with their height markedly exceeding their base width. Consequently, their aspect ratio is generally greater than that of other objects, such as building facades, low vegetation and vehicles. The aspect ratio is defined as the ratio of the height of the smallest bounding box of an object primitive to its base width, calculated using the following Equation:

where is the height of the object primitive, calculated from the elevation difference between the highest and lowest points of the object primitive. , , , represent the value range of the object primitive on the X and Y axes, respectively. The height of the tree trunk object primitive is usually greater than its base width, while the aspect ratio of other objects such as buildings, low vegetation and vehicles is usually flat or slender cuboid, much smaller than that of the tree trunk. Therefore, by setting an appropriate aspect ratio threshold, the tree trunk point cloud can be accurately extracted.

To precisely identify tree trunks, threshold-based criteria are applied to the extracted linearity and aspect ratio features. An object primitive is designated as a tree trunk candidate if its linearity surpasses a predetermined threshold and its aspect ratio exceeds a specified value. In this study, the linearity threshold is set at 0.65 to denote strong linear structures, while the aspect ratio threshold is established at 0.85 to represent tall and slender vertical objects. Object primitives that fail to meet either criterion are classified as non-trunk features and excluded from subsequent processing. These thresholds are empirically determined based on the geometric characteristics of tree trunks and validated through extensive experimentation. They effectively minimize interference from canopy points, buildings, low-lying vegetation, and other objects.

2.2.3. Tree Vertex Constraints

After extracting tree trunk point clouds based on linear and aspect ratio features, this paper further incorporates tree vertex constraints to facilitate effective association between tree trunks and canopies.

First, points that exceed a preset height threshold are selected to form a candidate set of tree vertices. These vertices are subsequently subjected to voxelization. Following voxelization, connectivity analysis is conducted to retain only major connected regions with more points than the threshold, thereby eliminating isolated point cloud clusters and mitigating interference from false treetops. Subsequently, within the candidate set, a K-D tree neighborhood search is employed to extract local height maxima. A non-maximum suppression strategy is then employed to ensure that each canopy region retains only one unique treetop candidate point. The core formulas are presented in Equations (7) and (8).

where is the candidate set of tree vertices that satisfy the height threshold and local maximum conditions, is the i-th point in the point cloud, is the z coordinate corresponding to , represent the selection of local peaks, is the set of K nearest neighbors centered at . is the final set of unique tree vertices, is the set of tree vertices after filtering, is the Euclidean distance calculation, is the non-maximum suppression radius, which controls that only one vertex is retained in a tree canopy region, and is the currently selected final tree vertex.

Finally, the treetop candidate points are matched with candidate tree trunks. Based on geometric constraints such as horizontal distance, tree height structure, and spatial relative position, the system calculates a matching score. In cases where multiple root points are present, the root point with the highest matching score is retained. This ensures the correct correspondence between treetops and trunks, thereby enhancing the accuracy and robustness of individual tree identification.

As shown in Figure 3, the tree trunk extraction and tree vertex constraint based on spatial features can effectively associate the tree trunk and the tree crown, providing reliable and quantifiable initial conditions for subsequent fine segmentation of tree point clouds based on the shortest path and the distance from the point to the stem axis.

Figure 3.

Illustration of the treetop constraint process. The point cloud shows the spatial distribution of points after applying height thresholding, voxelization, and connectivity filtering. Local height maxima extracted through K-D tree neighborhood search are retained as treetop candidates after non-maximum suppression. The red points represent the detected trunk nodes used to associate each treetop candidate with its corresponding tree trunk.

2.3. Individual Tree Point Cloud Segmentation Based on Shortest Path and Point-to-Stem Axis Distance

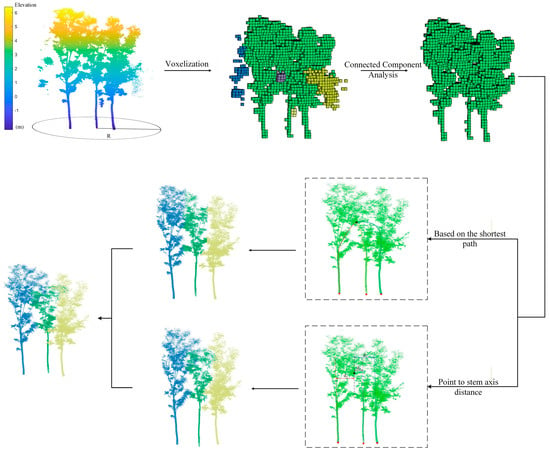

After completing the extraction of the trunk point cloud and obtaining the complete point cloud of an individual tree, this paper further introduces a connectivity analysis method. Specifically, the non-ground point cloud is initially voxelized. Subsequently, it is determined whether each voxel contains point cloud data, with voxels containing points assigned a value of 1 and empty voxels assigned a value of 0. Next, using the voxel containing the tree trunk point as the seed, connected voxel blocks are identified, and the point clouds within them are extracted as the initial tree point cloud.

After obtaining the initial results, this paper employs two optimization strategies to segment the tree point cloud: one is tree point cloud segmentation optimization based on the shortest path, and the other is tree point cloud segmentation optimization based on the distance from the point to the stem axis. Finally, the intersection of the segmentation results obtained by the two optimization methods is taken as the final tree point cloud segmentation result of this study.

By integrating voxel connectivity with multiple optimization strategies, this method effectively avoids over-segmentation and under-segmentation issues caused by interference from nearby vegetation or noise points, while enhancing the accuracy and robustness of the segmentation results and ensuring the integrity of the overall tree structure. The overall processing flow is depicted in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Flowchart of the individual tree point clouds segmentation.

2.3.1. Tree Point Cloud Segmentation Based on Shortest Path

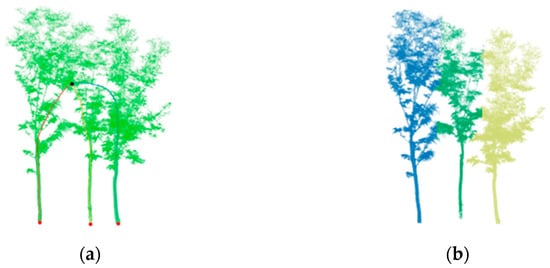

In real-world scenarios, tree canopies frequently intersect and overlap (as illustrated in Figure 5). This can result in under-segmentation of the tree point cloud obtained through connectivity analysis, thereby compromising the accuracy of subsequent vegetation parameter extraction and modeling. To address this issue, this paper introduces a point cloud segmentation method based on shortest path analysis to refine the initial tree point cloud.

Figure 5.

Optimized segmentation of tree point clouds based on the shortest path. (a) The individual tree point clouds before optimized segmentation. (b) The result after optimized segmentation. Red dots represent identified root nodes, and curves of different colors represent the shortest distances from that point to the root nodes of adjacent trees.

Specifically, this method initially checks whether a tree point cloud set contains two or more lowest points of the trunk primitives. If it does, a connected graph is constructed using the k-nearest neighbor method to depict the spatial topological relationships between the point clouds. Subsequently, the shortest path length from each node to each lowest point of the trunk is calculated. Theoretically, the shortest path from a point in the canopy to the lowest point of its own trunk should be less than the shortest path from that point to the lowest points of other trunks. Consequently, nodes are allocated to the trunk category corresponding to their shortest paths, thereby achieving optimized segmentation of the tree point cloud.

As depicted in Figure 5b, this method can effectively distinguish between roadside trees with intersecting and overlapping canopies, enabling precise segmentation of multiple trees. Compared to methods that rely solely on connectivity, the shortest path-based optimized segmentation not only improves the accuracy and robustness of segmentation but also significantly enhances the separation of intersecting and overlapping trees, providing a reliable data foundation for subsequent extraction of tree morphological features.

2.3.2. Tree Point Cloud Segmentation Based on Point-to-Stem Axis Distance

In Section 2.2, this paper extracts the tree trunk point cloud based on the spatial features of object primitives. Building upon this, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is employed to identify the principal orientations of the tree trunk point cloud, enabling the calculation of the stem axis. After identifying and isolating the base of the tree trunk, the axis of each trunk can be established through the orientation of the first principal component derived from PCA, thereby serving as the spatial representation of the stem axis (as illustrated in Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Identification of tree trunk axis. The black straight lines depict the stem axes extracted via PCA, serving as the orientation reference for individual trees.

Subsequently, the Euclidean distance from each point to each trunk axis is calculated. Theoretically, the distance from a point within a tree canopy to the trunk axis of its corresponding tree should be shorter than the distance from that point to the trunk axes of other trees. Based on this principle, this paper assigns labels to points across the entire point cloud according to the distance of each point to these axes, thereby assigning each point to a corresponding tree and achieving optimized segmentation of the point cloud of the entire tree. The segmentation results are shown in Figure 7. This method can effectively distinguish street trees with three intersecting and overlapping canopies, enabling precise separation of multiple trees. Specifically, street trees with three intersecting and overlapping canopies were successfully segmented. Compared to methods that rely solely on connectivity, the segmentation strategy based on the distance from a point to the stem axis better reflects the geometric structural characteristics of the trees. It also provides higher stability and segmentation accuracy in scenarios involving intersecting and overlapping canopies.

Figure 7.

Optimized segmentation of tree point clouds based on point-to-stem axis distance. (a) The individual tree point clouds before optimized segmentation. (b) The result after optimized segmentation. is the distance between the two trees.

Finally, to further enhance the reliability of the segmentation results, this paper integrates the optimization results based on the shortest path and those based on stem-axis distance, taking their intersection as the final segmentation result (Figure 8). The intersection strategy can effectively prevents the retention of redundant point clouds caused by misclassification by a single method, and only retain the regions jointly identified by the two methods, thereby improving the robustness and reliability of the segmentation results while ensuring the integrity of the overall tree structure.

Figure 8.

Optimized segmentation results. Each individual segmented trees are in different colors, illustrating the effectiveness of the proposed method in separating densely distributed trees across the study area.

2.4. Accuracy Assessment

To quantitatively evaluate the performance of the proposed method, this paper selects precision (), Recall (), F1-score (), coverage () and Weighted Coverage (), which are commonly used in point cloud segmentation instance, as evaluation indicators with IoU > 0.75 as the threshold. The specific formulas are presented in Equations (9)–(13).

where represents the number of trees successfully segmented under the threshold of IoU > 0.75. represents the number of individual trees that have been incorrectly segmented or missed. represents the number of individual trees that were wrongly segmented. represents the i-th segmented tree. represents the number of point clouds in . represents the number of point clouds contained in the ground truth instance of an individual tree. represents the number of intersections between an individual tree and its true value, i.e., the number of correctly segmented point clouds. represents the weight of the i-th individual tree, which is the weight of the instance based on the number of ground truth points in the tree instance’s point cloud.

It is important to note that the experimental unit in this study is the “individual tree”, which constitutes the primary focus of our individual trees segmentation. Specifically, when referring to true positive (TP), it is indicating the count of individual trees that have been accurately segmented. Object primitives, on the other hand, serve as intermediate geometric constructs employed during the segmentation process to streamline the extraction of individual trees from point cloud datasets. These primitives are not the ultimate experimental unit; rather, they function as instrumental means to attain precise tree segmentation. Additionally, pixels are not applicable in this study since this paper is working with 3D point cloud data rather than 2D images.

3. Experimental Results and Analysis

3.1. Experimental Dataset

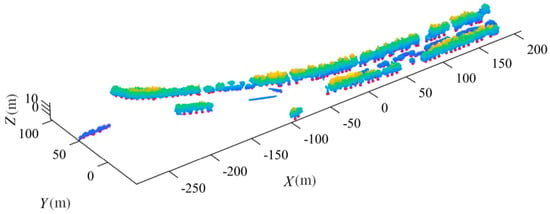

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed method, this paper use the WHU-Stree dataset [33] for testing. This publicly available dataset integrates vehicle-mounted LiDAR point cloud data acquired from two cities in China, Shenyang and Nanjing, which are located in different climate zones and exhibit distinct urban structures and vegetation compositions. The dataset covers approximately 66 km of urban roads and contains a total of 21,007 individual tree instances, encompassing more than 50 tree species and including two morphological parameters: tree height and diameter at breast height (DBH). The dataset can be accessed at https://github.com/WHU-USI3DV/WHU-STree (accessed on 1 July 2025).

In this study, three representative road sections were selected as experimental areas for method validation and comparative testing. These areas were deliberately chosen to encompass varying levels of tree density, canopy overlap, and environmental heterogeneity, thereby ensuring that the evaluation results accurately reflect diverse street conditions. The selected sections also exhibit differences in point density and occlusion intensity caused by surrounding urban infrastructure, offering a more thorough assessment of the method’s robustness. The three experimental areas employed in this paper are illustrated in Figure 9, which displays small yet representative segments of the overall dataset.

Figure 9.

Three experimental sites. (a) Site 1. (b) Site 2. (c) Site 3. Specifically, Site 1 contains 178 individual trees with a total of 22,064,482 points; Site 2 contains 64 trees with 12,291,874 points; and Site 3 contains 137 trees with 20,914,084 points.

3.2. Experimental Results

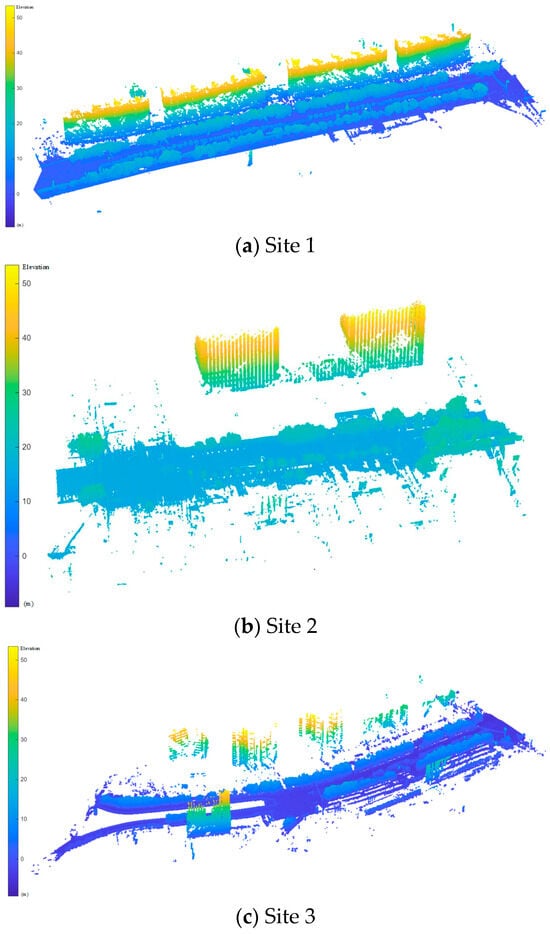

Figure 10 presents the street tree extraction results across the three experimental areas. As can be seen from the figure, the proposed method achieves favorable results in street tree segmentation for all three experimental sites (Site 1, Site 2, and Site 3), with different colors representing different individual trees. The visualization clearly illustrates that most tree point clouds are fully and distinctly separated, featuring well-defined boundaries between trees and effectively preventing the adhesion between point cloud clusters.

Figure 10.

Results of street tree segmentation in three experimental areas using our method. Randomly assign colors to represent different segmented individual trees.

In Site 1, the proposed method effectively segments continuous roadside trees on both sides of the road. In Site 2, despite localized dense tree distribution, the method still accurately distinguishes individual trees, demonstrating its strong ability to segment individual trees. In Site 3, even with curved roads and irregularly distributed roadside trees, the proposed method maintains good segmentation results, highlighting its adaptability and robustness in complex scenarios. The segmentation visualization results confirm that the proposed method can effectively segment roadside trees in different road scenarios, exhibiting high accuracy and robustness.

3.3. Comparative Analysis

To objectively evaluate the performance of the proposed method, this paper selects two other classic tree segmentation methods for comparative testing. Wang et al. [34] proposed an unsupervised method based on the superpoint graph structure single tree classification (SSSC). This method first clusters the point cloud through geometric partitioning, dividing the point cloud into several super-points. Each super-point is regarded as a primitive in the graph structure and carries a fixed-size feature of its partition. Then, an undirected graph is constructed based on these super-points, and node segmentation is performed using the features of the super-points and shortest path analysis. Finally, by segmenting the nodes in the super-point graph, each super-point cluster corresponds to a single tree.

Peng et al. [35] proposed a single-tree segmentation method based on Nyström spectral clustering (NSC). First, the point cloud is scaled along the Z-axis to avoid the influence of height differences. Then, the point cloud is voxelized and divided into blocks using MeanShift clustering to obtain preliminary spatial cluster centers. Next, it is further divided using Nyström spectral clustering to determine the correspondence between each cluster center and the single-tree point cloud. Finally, each point is reassigned with the corresponding tree label, and parameters such as crown width and tree height are calculated to achieve refined segmentation and attribute extraction of single trees.

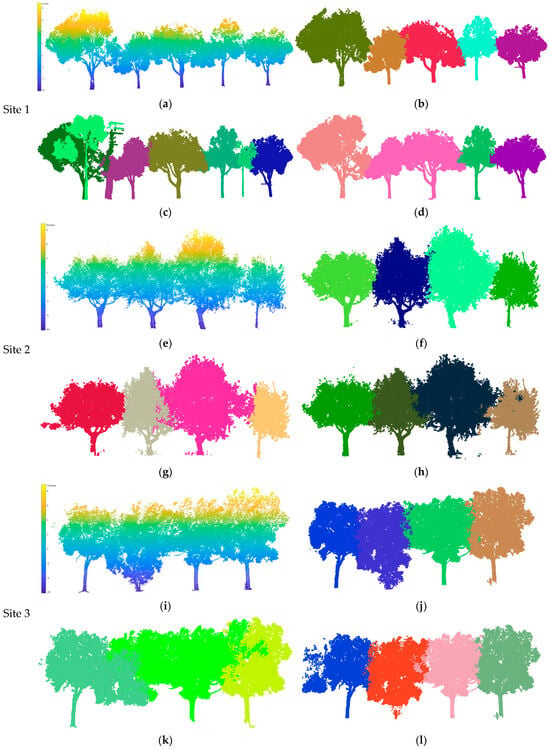

Figure 11 provides a detailed comparison of the segmentation results from the three methods. The comparison reveals that the proposed method outperforms both the NSC and SSSC methods in terms of the completeness and accuracy of boundary handling. Specifically, both methods exhibit significant limitations in addressing the canopy adjacency problem. The NSC method (Figure 11d,h,l) cannot solve the problem of canopy point cloud adhesion. In densely wooded areas, multiple individuals are often misclassified as the same tree, resulting in widespread under-segmentation errors. The SSSC method (Figure 11c,g,k) is limited by its difficulty in handling dense canopies and background noise, leading to severe under-segmentation in Site 2 and Site 3, and erroneously segmenting streetlight poles into individual trees in Site 1.

Figure 11.

Segmentation details comparison. (a,e,i) are the details of the three experimental areas, (b,f,j) are the segmentation results of this paper, (c,g,k) are the NSC segmentation results, and (d,h,l) are the SSSC segmentation results.

In contrast, the proposed method (Figure 11b,f,j) effectively overcomes these challenges in individual tree segmentation. Even in complex situations with severely intersecting canopies, it can accurately delineate the boundaries of adjacent trees, thereby avoiding under-segmentation and ensuring the accuracy of the segmentation results. Furthermore, considering the details of the trunk and canopy, the proposed method not only maintains the continuity of the trunk point cloud well but also achieves relatively accurate segmentation in areas with intersecting canopies. This demonstrates that the proposed method can balance segmentation accuracy and integrity when dealing with complex urban road scenes, exhibiting higher applicability and stability.

Table 1 presents a comparative analysis of the accuracy metrics point clouds contained in the ground truth instance of a single tree. the two methods mentioned above and the method proposed in this paper, focusing on street tree extraction across three experimental regions. As can be seen from Table 1, the method proposed in this paper performs better overall in most cases across the five segmentation metrics of street trees in the three experimental regions. Specifically, the F1-score is optimal in all three experimental regions when the IoU is greater than the threshold of 0.75, with scores of 0.772, 0.767, and 0.765, respectively.

Table 1.

Comparison of accuracy indicators of three methods.

In the Site 1 scenario, the proposed method significantly outperforms SSSC and NSC in terms of precision, Recall, and F1-score. Compared to the second-best performing SSSC method, it achieves an improvement of approximately 24% in F1-score. Furthermore, it also demonstrates the best performance in coverage and Weighted Coverage, achieving the highest Overall Accuracy (OA) of 0.6194, which is a substantial gain of 36.0% over SSSC (0.4519) and 89.3% over NSC (0.3277). This marked superiority in OA fully underscores the overall high precision and completeness of our segmentation results in this scenario.

For the Site 2 scenario, our proposed method outperforms the other two methods in F1-score, improving upon NSC and SSSC by 0.237 and 0.171, respectively. Simultaneously, our method also outperforms the other two methods in Recall, coverage, and Weighted Coverage and achieves the highest Overall Accuracy of 0.6221, surpassing SSSC by 29.9% and NSC by 73.7%. These results indicate that, in this sample site, the proposed method delivers superior segmentation accuracy while maintaining high Recall, thereby demonstrating excellent comprehensiveness and balance.

In the Site 3 scenario, although SSSC performed exceptionally well in Recall, its relatively low precision led to a high false positive rate. In contrast, the proposed method outperformed both SSSC and NSC in terms of precision and F1-score, and attained the highest OA of 0.6194, exceeding SSSC (0.5914) and NSC (0.3689) by 4.7% and 67.9%, respectively. However, the Weighted Coverage at Site 3 was lower, primarily due to the increased structural complexity of individual trees and the greater heterogeneity of the surrounding environment. In contrast to Sites 1 and 2, this site contains a substantially higher proportion of trees with heavily overlapping crowns, irregular and asymmetric branching patterns, and pronounced occlusion caused by adjacent street infrastructure. Because the Weighted Coverage metric assigns larger weights to trees represented by denser point clouds, any omission or misclassification affecting these large-crown trees produces a disproportionate influence on the final score. Consequently, despite the model’s stable performance on smaller or less occluded trees, the compounded effects of crown overlap, structural irregularity, and environmental occlusion introduce more segmentation errors in high weight trees, ultimately leading to the reduction in Weighted Coverage. Nevertheless, the superior OA achieved by our method demonstrates that it effectively balances accuracy and completeness of identification, avoids excessive false positives, and maintains a more robust overall segmentation performance even under challenging urban conditions.

The elevated Recall of SSSC in several sites primarily derives from its tendency to over-aggregate superpoints. SSSC first partitions the point cloud into geometric superpoints and then merges them using graph-connectivity cues and shortest-path similarity. In environments characterized by dense canopy overlap or weak trunk-crown separation, this merging scheme frequently fuses neighboring crowns or elongated linear structures into a single entity. Consequently, SSSC captures a large portion of true tree points, yielding high Recall, but at the expense of incorporating substantial non-tree points or collapsing multiple trees into the same cluster, which in turn degrades precision and the overall F1-score. This issue is particularly evident in Site 3, where severe crown occlusion drives SSSC’s Recall to 0.875 while substantially lowering its precision to 0.646. NSC, in contrast, exhibits an opposite pattern of failure. As it relies on spatial clustering of voxelized blocks followed by Nyström-based spectral refinement, NSC is more susceptible to height discontinuities and block boundary artifacts. It therefore tends to under-segment trees with irregular crown morphology or leaning stems, leading to reduced Recall but comparatively stable precision. Our method achieves a more balanced segmentation performance. By integrating multi-constraint graph partitioning with dual-stage optimization, it suppresses both over- and under-segmentation. Although minor omissions persist under extreme occlusion, the proposed approach attains consistently higher F1-score and coverage by preserving inter-tree boundaries while maintaining structural completeness. Across all three evaluation areas, it surpasses competing methods in average accuracy, F1-score, and coverage. In particular, the method demonstrates strong stability and adaptability across diverse roadway conditions, validating its effectiveness and robustness.

Our method achieves a more balanced segmentation performance. By integrating multi-constraint graph partitioning with dual-stage optimization, it suppresses both over- and under-segmentation. Although minor omissions persist under extreme occlusion, the proposed approach attains consistently higher F1-score and Coverage by preserving inter-tree boundaries while maintaining structural completeness. Across all three evaluation areas, it surpasses competing methods in average accuracy, F1-score, and Coverage. In particular, the method demonstrates greater stability and adaptability across diverse roadway conditions, validating its effectiveness and robustness.

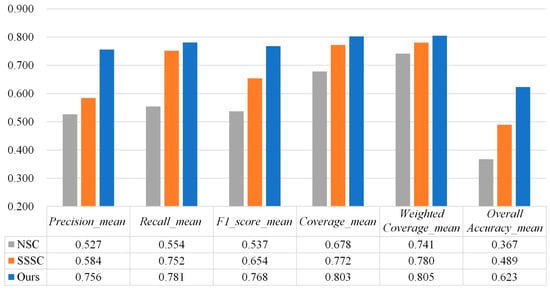

Figure 12 compares the mean values of various precision metrics for the three methods. The results show that our proposed method achieves the best performance across all five evaluation metrics. Specifically, Precision_mean, Recall_mean, and F1-score_mean reach 0.756, 0.781, and 0.768, respectively, significantly outperforming NSC (0.527, 0.554, 0.537) and SSSC (0.584, 0.752, 0.654). This indicates that our proposed method maintains high precision while also considering Recall, resulting in a more balanced and robust segmentation outcome. Our proposed method also performs excellently in Coverage_mean and Weighted Coverage_mean, reaching 0.803 and 0.805, respectively, representing improvements of approximately 18.5% and 8.6% over NSC, and approximately 4.0% and 3.2% over SSSC. In addition, our method attains the highest Overall Accuracy_mean, achieving 0.623 compared with 0.367 for NSC and 0.489 for SSSC. This substantial improvement further confirms the superior and more reliable segmentation performance of our approach across different evaluation criteria.

Figure 12.

Comparison of the mean values of each accuracy indicators of the three methods.

Overall, in the three experimental regions with an IoU greater than 0.75, our method outperforms both comparative methods in key metrics such as accuracy, F1-score, and coverage. The experimental results prove that our method not only demonstrates strong competitiveness in overall segmentation accuracy, but also shows greater stability and adaptability when dealing with road scenarios featuring diverse data characteristics. This validates its effectiveness and robustness in complex urban environments.

3.4. Visual Analysis of Segmentation Errors

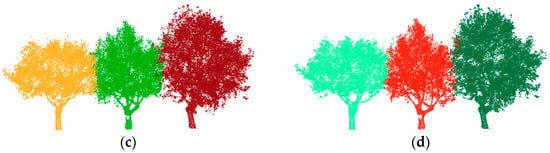

Although the shortest-path and PCA-based trunk axis estimation techniques employed in this paper can accurately segment individual trees in numerous instances, both methods still encounter separation errors in complex street environments. To better elucidate this issue, Figure 13 showcases four representative cases, encompassing the ground truth distribution, two types of incorrect segmentations, and the correct result achieved by the proposed method. This comparison aids in clarifying the origins of segmentation errors and highlights the advantages of the proposed approach.

Figure 13.

Comparison of individual tree segmentation results by three different methods. (a) Ground-truth segmentation result. (b) Shortest-path segmentation result. (c) PCA-based trunk-axis–estimation segmentation result. (d) The proposed method segmentation result.

Figure 13a displays the actual tree distribution, featuring clearly and well-separated tree crowns. It functions as the visual reference standard for evaluating the accuracy of subsequent segmentation results.

Figure 13b underscores the typical failure mode of the shortest-path method. The algorithm wrongly connects points that belong to two adjacent trees, causing the stem skeleton to deviate from the true trunk path. The results in partial merging of crown regions or their assignment to the wrong tree, creating a noticeable discrepancy compared to the ground truth are shown in Figure 13a. Such errors mainly arise when two trunks are in close proximity, branches intersect, or the point density is uneven. Given that the shortest-path method solely depends on geodesic distance, it is highly susceptible to local occlusion and irregular sampling, which makes it likely to choose an incorrect path.

Figure 13c illustrates the typical error generated by PCA-based trunk axis estimation. The PCA axis incorrectly inclines towards high-density branches or off-axis structures, particularly when the point cloud around the trunk is uneven or the trunk has curvature. The resulting splitting plane deviates from the true stem orientation, leading to boundary shifts and mis-segmentation. When compared to the ground truth in Figure 13a, it is clear that adjacent crowns are not properly separated, and several segments extend into neighboring trees. In real street tree datasets, leaning stems, asymmetric cross-sections, and uneven point sampling can easily distort the principal components, resulting in unstable segmentation outcomes.

Figure 13d demonstrates that the proposed method generates segmentation results that closely resemble the ground truth. Each tree is clearly demarcated, and the crown boundaries align well with the actual tree structures. By incorporating neighborhood constraints, angular filtering, and structural cues, the method maintains the continuity of the trunk and the natural transition between the trunk and the crown. The subsequent refinement using shortest-path optimization and stem-axis distance analysis further eliminates most of the remaining misalignments. As a consequence, cross-assignments between neighboring trees are significantly reduced, even in areas with dense foliage and overlapping crowns.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Limitations of the Proposed Method

The proposed multi-constraint and shortest-path segmentation method exhibits commendable robustness and accuracy across a variety of urban environments. In contrast to classical geometry-based methods, this study enhances structural integrity by integrating multiple spatial constraints and path-based optimization strategies. These combined efforts contribute to a more precise delineation of overlapping crowns and ensure the continuity of trunks.

Despite the fact that the proposed multi-constraint and shortest-path segmentation method attains robust performance in diverse urban settings, several limitations need to be recognized and critically analyzed.

- i.

- Sensitivity to Point Density

The performance of the proposed method is influenced by the density of the point cloud data. Low point density can lead to incomplete delineation of tree structures, particularly for large or irregular canopies. When the point density is low or when data contain severe occlusions and noise, the adaptive neighborhood radius may fail to capture enough local geometric information to preserve crown continuity. This can result in incomplete delineation of large or irregular canopies, especially in cases where trees are partially obscured by urban structures or vehicles. Pre-filtering and data normalization can mitigate this issue but cannot fully compensate for structural gaps in the source data.

- ii.

- Influence of Scanning Trajectory

The scanning trajectory of the LiDAR system can significantly impact the completeness and accuracy of the point cloud data, especially concerning tree crowns. Given that the performance of the proposed method is contingent upon the quality of the LiDAR data, as previously discussed, it follows that the scanning trajectory will also influence the final outcomes of individual tree segmentation. To optimize the extraction of individual trees, the scanning trajectory should be carefully planned to minimize occlusions as much as possible. Additionally, maintaining a slow and uniform scanning speed is crucial. By adhering to these guidelines, the acquired point clouds will be of high quality, with occlusions minimized to the greatest extent possible.

- iii.

- Dependence on the Quality of Stem Detection

In this study, the quality of stem detection directly affects the accuracy of individual tree segmentation. When stem points are correctly identified and localized, the subsequent steps in the segmentation pipeline, such as connectivity analysis, shortest path optimization, and point-to-stem axis distance calculation can proceed more effectively. This leads to more precise delineation of tree boundaries and reduces the likelihood of over-segmentation or under-segmentation. Conversely, if stem detection is inaccurate due to factors such as noise, missing points, occlusions, or complex tree architectures, the segmentation results can be severely compromised. For instance, missing stem points can lead to incomplete tree structures, while falsely detected stem points can introduce erroneous associations between crowns and trunks, resulting in mis-segmentation.

4.2. Discussion on Parameter Selection and Sensitivity

All parameters used in this paper are summarized in Table 2. As shown in Table 2, the quality of geometric primitive acquisition is jointly controlled by the normal vector threshold, verticality threshold, and neighborhood radius. An adaptive strategy is adopted for the neighborhood radius, which is dynamically determined based on the local point density estimated from each query point and its ten nearest neighbors. In the structural extraction stage, the height threshold is used to distinguish the basal trunk section from the ground. In addition, morphological constraints, including aspect ratio, linearity, and matching radius, collectively influence the accuracy of trunk extraction. The crown radius plays a key role in determining the accuracy of the final individual tree segmentation and canopy delineation.

Table 2.

Parameter settings used in this paper.

To systematically evaluate the dependency of the proposed method on its key parameters, specifically the threshold and crown radius , a sensitivity analysis was conducted. As quantified in Table 3, the algorithm exhibits a high degree of robustness, characterized by marginal fluctuations in F1-score, Weighted Coverage, and Overall Accuracy across the tested parameter space . This observed insensitivity to parameter variations suggests that the method possesses strong generalization capabilities and is not prone to instability caused by minor parameter perturbations. However, to ascertain the optimal configuration for maximizing segmentation accuracy, a comparative analysis of the local maxima was performed. The empirical results demonstrate that the combination of m and m yields the superior balance between feature coverage and precision. Under this configuration, the model achieves peak performance across all indicators, recording an F1-score of 0.772, a Weighted Coverage of 0.86, and an Overall Accuracy of 0.6285. Consequently, the parameters selected here is identified as the empirically optimal setting and is adopted as the default configuration for the subsequent experiments.

Table 3.

Parameter sensitivity analysis.

4.3. Evaluation of Processing Efficiency and Algorithmic Complexity

To conduct a more in-depth assessment of the computational performance of the proposed framework, we compared its runtime with that of two classical methods, namely SSSC and NSC, across the three experimental sites within the WHU-STree dataset. Site 1 comprises 178 individual trees, with a total of 22,064,482 points; Site 2 encompasses 64 trees, containing 12,291,874 points; and Site 3 consists of 137 trees, with 20,914,084 points.

All experiments were carried out on a workstation configured with a 13th-Gen Intel (R) Core (TM) i7-13700K CPU operating at 3.40 GHz, 64 GB of RAM, and an NVIDIA RTX 3060 GPU, running under the Windows 11 operating system. All the codes were implemented using MATLAB R2023b.

As shown in Table 4, the proposed method requires a longer processing time (approximately 7.5 h per scene on average) compared with the SSSC and NSC methods. This increased computational cost is mainly attributed to the multi-constraint graph construction and shortest-path optimization procedures, which ensure accurate tree delineation even under dense canopy overlap and occlusion. From a theoretical perspective, the method’s dominant computational cost arises from two stages: (1) the KD-tree-based k-nearest neighbor search used for graph construction, and (2) the Dijkstra shortest-path computation for tree point assignment.

Table 4.

Comparison of average runtime among different methods (unit: hours).

Despite the relatively long processing time, the proposed method consistently achieves higher segmentation accuracy, with mean F1-score and coverage values surpassing those of the baseline methods. Specifically, the mean F1-score of our method (0.768) is significantly higher than that of NSC (0.537) and SSSC (0.654). These results indicate that the trade-off between computational cost and accuracy is acceptable, particularly for applications requiring high-precision mapping of urban street trees.

5. Conclusions

Individual tree segmentation in urban environments is a pivotal step for resource inventorying and vegetation parameter estimation. Nevertheless, current methods for extracting urban street trees continue to encounter challenges stemming from point cloud quality issues, occlusions, and environmental noise.

To tackle these problems, this paper introduces an individual tree segmentation method specifically designed for urban street trees, which is based on the integration of multi-constraint and shortest-path optimization techniques. Initially, the method employs radius constraints, vertical angle constraints, and normal vector constraints for primitive object segmentation. Subsequently, it extracts root nodes by combining the aspect ratio of objects with linear feature detection, and further refines trunk point cloud segmentation through tree vertex optimization. Finally, precise segmentation of tree point clouds is accomplished by integrating the shortest path with the point-to-stem axis distance, thereby effectively enhancing both the completeness and accuracy of individual tree delineation.

An evaluation conducted on three representative regions of the WHU-STree dataset reveals that the proposed method consistently demonstrates improved performance compared to existing approaches. The method achieves F1-score of 0.772, 0.767, and 0.765, respectively, outperforming the NSC and SSSC methods. In comparison with SSSC, the proposed method shows increases in both precision and F1-score while maintaining competitive coverage and Weighted Coverage metrics. These results suggest that the method offers a well-balanced segmentation outcome, improving delineation accuracy without increasing the likelihood of false detections, and showcases reliable adaptability across a variety of urban road conditions.

Future research will concentrate on expanding the framework to encompass a wider range of urban forest compositions, investigating its performance under different point cloud densities and acquisition conditions, and incorporating deep learning-based or hybrid strategies to enhance the delineation of complex tree structures. These advancements are anticipated to facilitate more accurate, scalable, and automated assessments of urban vegetation resources.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing–original draft preparation, S.Y.; Investigation, Formal Analysis, Supervision, D.L.; Funding acquisition, Writing–review & editing, Supervision, Z.H.; Formal Analysis, X.X.; Formal Analysis, H.L.; Writing—review & editing, X.C.; Writing—review & editing, F.H.; Resources, Supervision, L.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Outstanding Young Talents Funding of Jiangxi Province (20232ACB213017), Double Thousand Plan of Jiangxi Province (DHSQT42023002), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangxi Province (20242BAB25176, 20192BAB217010), Funding of National Key Laboratory of Uranium Resources Exploration-Mining and Nuclear Remote Sensing (2025QZ-YZZ-08-1, 2024QZ-TD-26) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSF) (42161060, 41801325) for their financial support.

Data Availability Statement

The WHU-STree dataset used in this paper is accessible for download from the following link: https://github.com/WHU-USI3DV/WHU-STree. (accessed on 1 July 2025). The corresponding codes can be acquired after a request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Xie, F.; Yang, F.; Wei, H. Urban Tree Extraction Method Based on LiDAR Data and Orthophoto. Laser Optoelectron. Prog. 2022, 59, 435–442. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Z.; Li, L.; Deng, L. Extraction of Individual Tree DBH and Tree Height by Fusing Terrestrial and UAV Laser Data. J. Northeast. For. Univ. 2025, 53, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Morais, S.M.F.; Pereira, A.A.; Oliveira, U.F.D. Inventário Florestal Urbano do município de Botelhos, MG. Ciência Florest 2024, 34, e71628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Zhong, X.; Zhong, R. A method for automatic extraction and individual segmentation of urban street trees from laser point clouds. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 180, 111431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pataki, D.E.; Alberti, M.; Cadenasso, M.L. The benefits and limits of urban tree planting for environmental and human health. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 9, 603757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Han, Z.; Chen, Y. Tree Species Classification of LiDAR Data based on 3D Deep Learning. Measurement 2021, 177, 109301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassnacht, F.E.; Latifi, H.; Stereńczak, K. Review of studies on tree species classification from remotely sensed data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 186, 64–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liang, W. Application of vehicle-mounted laser point clouds in extraction of geometric attributes of urban street tree survey. Beijing Surv. Mapp. 2024, 38, 1599–1603. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.; He, L.; Ma, S. Multimodal LiDAR Enhancement Algorithm Based on Multiscale Features. Laser Optoelectron. Prog. 2024, 61, 238–246. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, G.; Xie, R.; Lei, Z. LiDAR Ground-Segmentation Algorithm Based on Slope Threshold and Convolution Filtering Processing. Laser Optoelectron. Prog. 2023, 60, 308–317. [Google Scholar]

- Hui, Z.; Li, N.; Cheng, P. Single Tree Segmentation Method for Terrestrial LiDAR Point Cloud Based on Connectivity Marker Optimization. Chin. J. Lasers 2023, 50, 0610002. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, D.; Wang, H.; Xu, W.; Luan, Z.; Xu, X. LiDAR Applications to Estimate Forest Biomass at Individual Tree Scale: Opportunities, Challenges and Future Perspectives. Forests 2021, 12, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, R. Establishing a citywide street tree inventory with street view images and computer vision techniques. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2023, 100, 101924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Khoshelham, K.; Chen, C. Individual tree extraction from urban mobile laser scanning point clouds using deep pointwise direction embedding. ISPRS J. Photogramm. 2021, 175, 326–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revelli, R.; Porporato, A. Ecohydrological model for the quantification of ecosystem services provided by urban street trees. Urban Ecosyst. 2018, 21, 489–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, T.; Jiang, K.; Li, G. Individual tree crown segmentation from airborne LiDAR data using a novel Gaussian filter and energy function minimization-based approach. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 256, 112307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubrovin, I.; Fortin, C.; Kedrov, A. An open dataset for individual tree detection in UAV LiDAR point clouds and RGB orthophotos in dense mixed forests. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 21938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, N.; Liao, Z. Street tree extraction method based on vehicle-borne laser point cloud data. Beijing Surv. Mapp. 2023, 37, 1617–1622. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y.; Li, Q.; Li, W. A single tree segmentation method for street trees facing side-looking MLS point clouds. J. Nanjing For. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2024, 48, 166–174. [Google Scholar]

- Mongus, D.; Žalik, B. An efficient approach to 3D single tree-crown delineation in LiDAR data. ISPRS J. Photogramm. 2015, 108, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabo, C.; Ordóñez, C.; López-Sánchez, C.A. Automatic dendrometry: Tree detection, tree height and diameter estimation using terrestrial laser scanning. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. 2018, 69, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhang, Y. Street tree extraction method based on vehicle laser scanning technology. Geomat. Technol. Equip. 2022, 024, 81–85. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Cheng, X.; Xiao, Z. A branch-trunk-constrained hierarchical clustering method for street trees individual extraction from mobile laser scanning point clouds. Measurement 2022, 189, 110440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, R.; Shi, W. An Individual Tree Segmentation Method That Combines LiDAR Data and Spectral Imagery. Forests 2023, 14, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, P.A.; Conti, L.A.; Neto, F.C.N. Mangrove individual tree detection based on the uncrewed aerial vehicle multispectral imagery. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2024, 33, 101100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, Z.; Li, X.; Xiu, S. Individual Tree Crown Delineation Using Maker-controlled Region Growing Method. J. Northeast. For. Univ. 2016, 44, 22–29. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, S.; Adler, P.; Dees, M. Comparing image-based point clouds and airborne laser scanning data for estimating forest heights. iForest 2017, 10, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, Z.; Cheng, P.; Yang, B. Multi-level self-adaptive individual tree detection for coniferous forest using airborne LiDAR. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. 2022, 114, 103028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Z.; Xu, S.; Liu, Y. Individual Tree Segmentation from Side-View LiDAR Point Clouds of Street Trees Using Shadow-Cut. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Qi, J.; Wan, P.; Wang, H.; Xie, D.; Wang, X.; Yan, G. An Easy-to-Use Airborne LiDAR Data Filtering Method Based on Cloth Simulation. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, S.; Wu, F.; Guo, Q. Segmenting tree crowns from terrestrial and mobile LiDAR data by exploring ecological theories. ISPRS J. Photogramm. 2015, 110, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, C.; Rosinskaya, E.; Häni, N. Classification of aerial photogrammetric 3D point clouds. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 2018, 84, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, R.; Chen, Z.; Fan, W. WHU-STree: A Multi-modal Benchmark Dataset for Street Tree Inventory. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.13172. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D. Unsupervised semantic and instance segmentation of forest point clouds. ISPRS J. Photogramm. 2020, 165, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Wang, W.; Du, L. Nyström-based spectral clustering using airborne LiDAR point cloud data for individual tree segmentation. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2021, 14, 1452–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.