Abstract

Valued above all others, the white truffle species (Tuber magnatum Picco) is highly dependent on the forest ecosystem and its underground biology. Despite its economic importance, knowledge of its biology and mycorrhizal symbioses remains limited; moreover, natural yields have sharply declined, and cultivation efforts have produced inconsistent results. This study evaluated various forest and mycorrhizal inoculation techniques to promote T. magnatum mycelium development in three Tuscan sites converted to truffle cultivation, using qPCR analysis. Alongside conventional practices like irrigation, mulching, and tillage, an experimental method with a sterile, spore-inoculated soil barrier was tested to improve host root establishment, enhance mycorrhization, and maintain long-term symbiosis for healthy truffle ecosystems. Soil analyses nine months after planting Quercus robur L. seedlings showed significant differences in Tuber magnatum mycelium abundance across sites and treatments. The MA treatment—mycorrhized seedlings combined with a sterile, inoculated substrate and separation diaphragm—produced the highest mycelial levels, underscoring the importance of initial mycorrhization and soil manipulation. These findings provide valuable insights for optimizing forest management and improving truffle cultivation by enhancing mycelial development, a key step toward increasing truffle production.

1. Introduction

The ectomycorrhizal fungus Tuber magnatum Picco, generally referred to as the Italian white truffle, is regarded as the most economically valuable truffle species, attributable to its exceptional sensory characteristics. This species thrives over an extensive geographical area, stretching from roughly ~37° N in Sicily to ~47° N in Russia, found at altitudes ranging from sea level in northern regions to 1000 m above sea level in the south. Natural T. magnatum habitats are typified by average winter temperatures surpassing 0.4 °C and mean summer rainfall near 50 mm. The ground substrate exhibits pH values between 6.4 and 8.7, substantial macropore volume, and an estimated cation exchange capacity of roughly 17 meq/100 g. A minimum of 26 putative host species, spanning 12 genera, have been documented in native truffle beds, with Populus alba and Quercus cerris comprising 23.5% of the total species [1].

To date, the harvest of T. magnatum in Italy has been mostly limited to natural forests, making its cultivation challenging compared to other truffle species like the Périgord black truffle (Tuber melanosporum Vittad). T. melanosporum is now primarily harvested from specialized orchards established with mycorrhized plants, which help ensure more consistent production [2].

Attempts to cultivate T. magnatum have often been unsuccessful, as many aspects of the ecology and biology of these fungal species remain poorly understood [1]. The studies of Marjanović et al. [3] and Bragato et al. [4] have clarified several fundamental ecological requirements of this species. Moreover, only with the advent of modern molecular tools, the morphology of the ectomycorrhiza of T. magnatum has been conclusively defined [5,6]. In the past, inaccurate morphological identification led to the commercialization of falsely mycorrhized plants allegedly associated with T. magnatum, compromising the outcomes of numerous research studies [7].

Thanks to research conducted by INRAE/Robin in France, certified and guaranteed mycorrhized seedlings of T. magnatum are now available. Bach et al. [2] have shown that it is possible to obtain fruiting bodies of this species after just 4/5 years from the planting of mycorrhized seedlings and that the mycelium of the fungus remains traceable in the truffle ground up to seven years post-planting. Quantifying soil mycelium has become a valuable tool for studying the development of numerous ectomycorrhizal species [8,9], enabling the monitoring of extra-radical mycelial biomass distribution [10] and its seasonal dynamics [11]. Using this technique, Iotti et al. [12] identified a positive correlation between soil mycelial abundance and the production of T. magnatum fruiting bodies. Furthermore, Oliach et al. and Sen et al. [13,14] demonstrated that specific soil management techniques in natural truffle grounds can increase the mycelial biomass of this highly prized species.

The extra-radical mycelium represents, therefore, the most reliable target for studying T. magnatum dynamics in the field, as it can form an extended mycelial network within productive areas [12,15,16].

The interest in the cultivation of T. magnatum is considerable particularly in areas of arable land where soil and environmental conditions are favorable for the production of prized white truffles. In Tuscany, some valley-floor arable lands struggle to find a crop destination compatible with the characteristics of the companies that manage the land or that can be easily integrated into the company’s cultivation systems. Truffle cultivation could offer a valuable opportunity for crop diversification, contributing to increased biodiversity, carbon sequestration through tree-based farming systems, and enhanced ecological sustainability by integrating forest species into agricultural landscapes.

From these considerations the need to evaluate the effectiveness of new cultivation techniques on Tuber magnatum production in arable land. The objective of this study was to evaluate the early establishment and abundance of T. magnatum extra-radical mycelium in newly planted truffle orchards, comparing the effects of nursery mycorrhization, in situ spore inoculation, and the use of separation diaphragms across three experimental sites in Tuscany.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Areas

The Tuscan environments, characterized by their specific soil types and microclimates [4], provide the ideal conditions for the growth of the prized white truffle. The habitats of this fungal delicacy have been well known for a long time and have recently been mapped in extreme detail by the Tuscany Region Administration. For the selection of experimental areas, potentially suitable sites for the development of white truffle cultivation were identified using various data layers provided by the Tuscany Region, including pedological data [17], land-use and geological data [18,19], as well as climate datasets supplied by the LaMMA Consortium [20].” Subsequently, three experimental sites located in flat areas with similar pedo-geographic characteristics were selected based on logistical and organizational criteria and following consultations with the farmers managing the agricultural lands (Figure 1). The selected study sites are Palaia (PAL), Montespertoli (MON), and Mugello (MUG), whose characteristics are reported below.

Figure 1.

Map of the study area with location of the 3 study sites: Palaia (PAL), Montespertoli (MON) and Mugello (MUG).

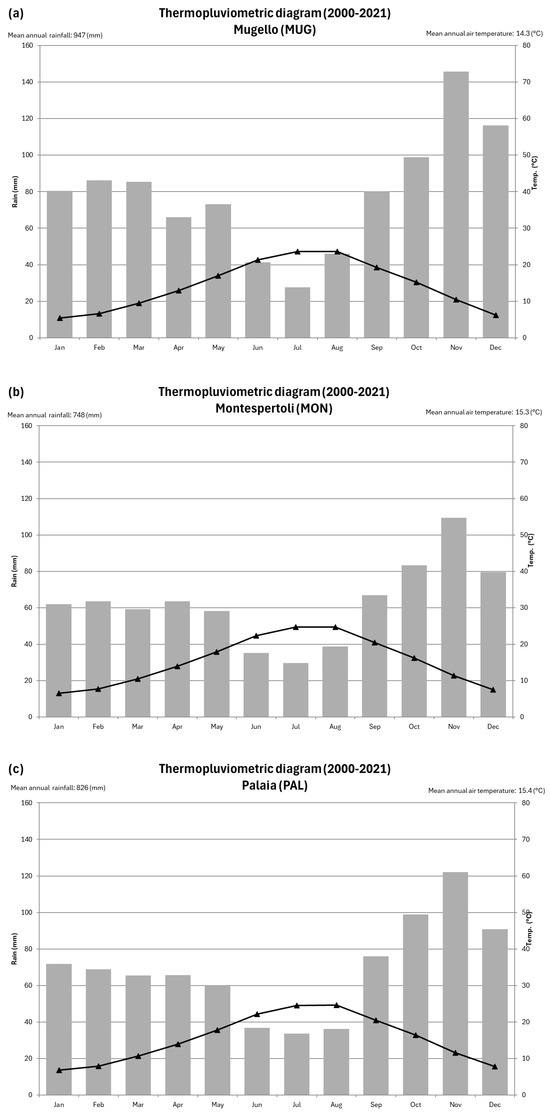

Mugello study site (MUG) is situated in the locality of La Gracchia at an elevation of 188 m a.s.l., within a flat alluvial valley (lat. 43°56′46″ N; long. 11°25′27″ E). The area consists of recent fluvial deposits left by the Ensa River, characterized by sandy texture and calcareous composition. The soils are deep, sandy loam in texture, non-skeletal, moderately alkaline, highly calcareous, and well-drained. According to the soil database of the Tuscany Region Administration [17] and the WRB classification system (IUSS Working Group WRB, 2015), these soils belong to the Calcaric Fluvisols group. From a climatic perspective, based on the Thornthwaite classification [21], the area is characterized by a C2 climate type (humid to sub-humid), with moderate summer water deficiency, an average annual rainfall of approximately 947 mm, and a mean annual temperature of around 14.3 °C (Figure 2a). The truffle ground was created on a plot of land left fallow and previously cultivated with potatoes.

Figure 2.

(a–c) Thermopluviometric diagrams of Mugello (a), Montespertoli (b) and Palaia (c).

Montespertoli study site (MON) is in the locality of Lungagnana (Montespertoli) (lat. 43°37′12″ N; long. 11°01′05″ E) at an elevation of 85 m a.s.l., on a gently sloping surface that connects a hillside to an alluvial valley floor. The substrate consists of alternating layers of sands and sandy clays of calcareous nature, of marine origin, dating back to the Pliocene age. The soils are deep, with a texture ranging from loam, silty loam, to silty clay loam, non-skeletal, slightly alkaline, highly calcareous, and moderately well-drained. According to the Tuscany Region soil database [17] and the WRB classification system [22], these soils are classified as Calcaric Cambisols. The mean annual precipitation is 749 mm, while the mean annual temperature is 15.3 °C (Figure 2b). The area falls within the C1 climate type (humid to semi-arid) and is characterized by hot and dry summers, according to Thornthwaite’s classification [21]. The truffle ground was created on a plot of land previously cultivated with alfalfa.

Palaia study site (PAL) is situated in locality La Casetta (Palaia) (lat. 43°38′06″ N; long. 10°47′27″ E) at an elevation of 55 m a.s.l., within an alluvial valley floor composed of recent fluvial deposits with sandy-silty texture and calcareous composition. The soils are deep, sandy loam in texture, well-supplied with organic matter, moderately alkaline, and slightly calcareous at the surface but highly calcareous at depth. They are also well-drained. According to the WRB classification system [22], these soils belong to the Calcaric Cambisols group. The mean annual precipitation is 947 mm, while the mean annual temperature is 14.3 °C (Figure 2c). The area falls within the C2 climate type (humid to sub-humid), with moderate summer water deficiency [21]. The truffle ground was created on a plot of uncultivated land for approximately 20 years.

Pedological analysis involved horizon differentiation, color determination, assessment of soil consistency, identification of redoximorphic features, detection of concretions, and measurement of the water table depth. Surface soil samples (0–30 cm) were collected and analyzed at the CNR laboratory in Florence following official protocols [23]. The analyses focused on particle size distribution, total carbonate content, pH in H2O, organic carbon content, and cation exchange capacity.

Before planting the seedlings, the three study fields underwent specific cultivation practices: in PAL continuous mulching was performed followed by superficial ripping to a depth of 35 cm; in MON the grass cover was disrupted through clod-breaking followed by a double cross-uprooting; in MUG superficial plowing was conducted to a depth of 40 cm.

In May 2023, a total of 180 one-year-old Quercus robur seedlings were planted across the three fields, with 60 seedlings per site, distributed among the different treatments as follows:

Treatment F: 15 non-mycorrhized seedlings purchased from the commercial nursery Mico Vivai Piante da Tartufo (Via Giovanni Paolo I 31, 64020 Castellalto, TE, Italy) were planted without modifications.

Treatment A: 15 non-mycorrhized seedlings from the same nursery were planted within a cylindrical plastic separation diaphragm (20 cm in diameter, 30 cm in length). Inside the barrier, a substrate consisting of 1.5 kg of sterile soil from the study site, inoculated with 5 g of T. magnatum spores, was added.

Treatment M: 15 certified mycorrhized seedlings with official techniques certified according to Italian law (legge 16/12/1985, n. 752) from the commercial nursery Vivai Azzato (Contrada Prito 6, 85050 Satriano di Lucania, PZ, Italy) were planted without modifications.

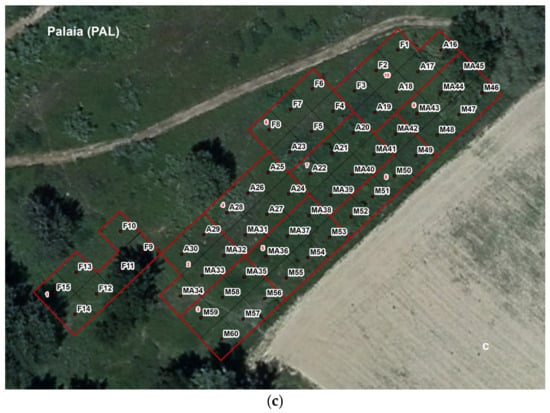

Treatment MA: 15 certified mycorrhized seedlings from Vivai Azzato were planted within a cylindrical plastic separation diaphragm (20 cm in diameter, 30 cm in length), with an added substrate composed of 1.5 kg of sterile soil from the study site, inoculated with 5 g of T. magnatum spores (Figure 3a–c).

Figure 3.

(a–c) Experimental design carried out in the three study sites. (F: Q. robur only; A: Q. robur + sterile and inoculated substrate + separation diaphragm; M: Q. robur mycorrhized in the nursery and planted; MA: Q. robur mycorrhized in the nursery + sterile and inoculated substrate + separation diaphragm).

In addition to providing both mycorrhized and non-mycorrhized plants, the “Mico Vivai Piante da Tartufo” nursery played an active role in the design and establishment of the three experimental sites.

Seedlings were planted in a 5 m × 5 m grid and, to protect the young plants from deer and hare bites in the study sites PAL and MON, a protective shelter was installed. This shelter, measuring between 1 and 1.20 m in height, was hand-crafted using galvanized/plastic-coated netting and secured to two iron rods arranged in a V shape. In contrast, the study site MUG was enclosed with an electric fence. The seedlings were subsequently irrigated, and a jute mulch sheet was placed around each one to help retain soil moisture in the months following planting. In all three study sites, at various times, a light manual hoeing was carried out before sampling to break the soil’s surface crust, improve aeration, and reduce competition from herbaceous plants.

2.2. Soil Sampling and Detection and Quantification of Tuber Extra-Radical Soil Mycelium

Before planting, soil analyses were conducted to assess the soil composition and the presence of T. magnatum mycelium and the most common Tuber species (T. aestivum, T. borchii, T. brumale, T. dryophilum, T. maculatum, T. melanosporum). In the study sites 30 soil cores per field (totaling 120) were collected in autumn 2021. Sampling was conducted using disposable polyvinyl tubes (1.6 cm diameter) to a depth of 30 cm. Soil samples were stored at 4 °C and extracted by breaking the tubes within 24 h of collection. Root fragments, stones, and organic debris were carefully removed. Subsequently, the soil was frozen at −80 °C until lyophilization (72 h using a VaCo 5 freeze dryer, Zirbus Technology). After freeze-drying, samples were ground and homogenized in a mortar, sieved through a 1 mm mesh, and stored at room temperature until DNA extraction.

Nine months after planting the seedlings (February 2024), superficial soil cores (up 10 cm deep) were taken to detect and quantify the presence of T. magnatum mycelium. Four independent soil cores were taken in the cardinal directions (North, South, East, West) at 10 cm from the seedling stem at the periphery of the separation barrier. In total, 720 soil cores were taken (4 cores × 15 plants × 3 treatments × 3 study sites, and 4 cores × 15 plants × 3 study areas for no treatment).

The four cores from each plant were then combined to obtain a single composite sample of approximately 30 g of soil (180 samples in total), which was subsequently processed following the standardized methodology described above until DNA extraction.

DNA extraction was performed using the Soil kit, Mini kit for DNA from soil (Macherey-Nagel™ NucleoSpin™, Düren, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Soil extracts were stored at −80 °C pending molecular analyses. Soil DNA was first amplified with the universal fungal ITS primers ITS1f/ITS4 [24,25]. Amplifications were performed in a 25 μL reaction volume consisting of: 2.5 μL of whole genomic DNA from each sample, 1.25 μL of both forward and reverse primers (10 μM), 12.5 μL of GoTaq® Long PCR Master Mix (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) 0.75 Bovine Serum Albumin (20 mg) and 6.75 μL of ddH2O. The amplification conditions: 95 °C for 6 min; 30 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 2:30 min and a final extension step of 72 °C for 10 min. Amplified DNA was stained by adding RedSafe™ nucleic acid staining solution (Applied Biological Materials Inc., Richmond, BC, Canada, Cat. No. G680) at a final concentration of 1X directly into the loading dye prior to electrophoresis. Electrophoresis was performed on a 1% agarose gel in 1X TAE buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at 110 V for 35 min. DNA bands were visualized under UV transillumination and documented using a gel documentation system.

From the soil samples collected before the seedling planting, a nested PCR approach was carried out. Nested PCR reactions were performed using species-specific primer pairs of the most common Italian truffles (Supplementary Table S1) [26,27,28,29,30] and amplifications were carried out with the same mix composition described above and using as DNA template 1 μL of the first PCR round amplified solution.

From the soil samples collected 9 months after seedling planting a quantitative PCR (qPCR) was carried out using the TaqMan probe TmgITS1prob 5′-TGTACCATGCCATGTTGCTT-3′ (MWG BIOTECH, Ebersberg, Germany) and TmgITS1for (5′-GCGTCTCCGAATCCTGAATA-3′) TmgITS1rev (5′-ACAGTAGTTTTTGGGACTGTGC-3′) as primer pair [12]. qPCR assays were carried out on a 96-well plate format (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) with a total reaction volume of 25 µL. Each reaction mixture contained Maxima Probe qPCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) at 1X concentration, 30 nM of ROX, 0.5 µM of both TmgITS1 forward and reverse primers (Metabion, Munich, Germany), and 0.2 µM of the TaqMan probe TmgITS1prob (MWG) [12]. 200 ng of template DNA was added per reaction. The TaqMan probe was labeled with a FAM (6-carboxyfluorescein) fluorophore at the 5’ end and a TAMRA (6-carboxytetramethylrhodamine) quencher at the 3’ end. The thermal cycling conditions were: 10 min at 95 °C followed by 45 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s. The fluorescence threshold level was determined with a predefined algorithm of the QuantStudio Design & Analysis Software 1.5.2 algorithm (Thermo Fisher) and the resulting Ct values were automatically converted to quantitative data using the standard curve method. This was generated with a decimal dilution series of genomic DNA from T. magnatum as a standard. The calibration curve was made to convert the real-time DNA concentration values to absolute amounts of mycelium in the soil. For each sampling, 7 dilutions of immature gleba tissue (from 1 mg to 10 mg) per g of free soil were performed in triplicate. For this purpose, an immature truffle (without spores) was selected since T. magnatum mycelium in culture is not available. The absence of mycelium in these samples was confirmed by species-specific PCR on soil DNA previously isolated with the Nucleospin kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany). Uninoculated soil samples were used as negative controls. To ensure that the genetic material quantified during the mycelium analysis did not originate from the spore inoculum applied in treatments A and MA, a parallel experiment was conducted. In this experiment, the same sterilized soil used in the main study (collected from the three experimental fields) was inoculated with an equal amount (5 g) of spores of the model species Tuber borchii [31]. The aim was to determine whether spore DNA could be extracted from the soil using the technique employed in this study. To this end, the number of mating types present in the soil after inoculation was assessed. Because the sterile hyphae of the gleba, which constitute the majority of the Tuber ascocarp tissue, are composed of haploid maternal material, whereas the ascospores contain both maternal and paternal genetic information [32], detecting only one mating type would indicate that the spores were not amplified using the adopted extraction method [33].

Statistical Analysis

The values of T. magnatum mycelial abundance were analyzed with a two-way ANOVA considering treatments (MA, A, M, F) and location of sites (PAL, MON and MUG) as independent variables. Tukey’s test post hoc test was used to separate means (p > 0.05). Statistical analyses were performed using XLSTAT software version 7.5.2 (Addinsoft, Paris, France).

3. Results

In Table 1, the results of soil analyses are reported. The soils of PAL exhibit higher organic carbon content compared to other areas. This can be attributed to the fact that the land was uncultivated for approximately 20 years prior to plantation establishment. As a result, the soils display greater friability, reflected in lower bulk density values, and the initial stages of decarbonation processes can be observed.

Table 1.

Soil parameters of the three study sites. (MON: Montespertoli; MUG: Mugello; PAL: Palaia).

Regarding particle size distribution, the soils of MON show higher clay and silt contents than those of the other two areas, along with a greater internal variability of these parameters.

As recommended by De Miguel et al. [34], prior to the planting seedling, the presence of T. magnatum mycelium and other common Tuber species (T. aestivum, T. borchii, T. brumale, T. dryophilum, T. maculatum, T. melanosporum) was assessed in the three study fields. The analyses revealed that in PAL, both T. dryophilum and T. magnatum mycelia were present; in MON, only T. dryophilum mycelium was detected; and in MUG, none of the analyzed Tuber species mycelium was found (Supplementary Table S2).

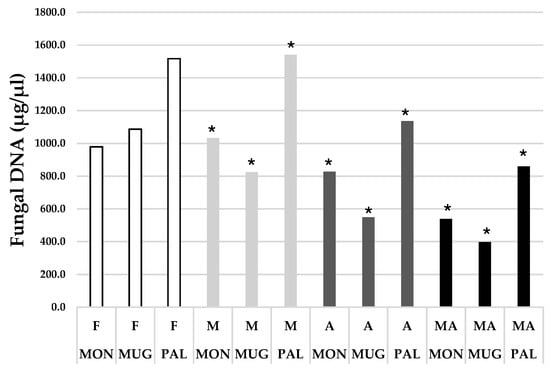

Fungal DNA was detected in all the soil samples taken from the seedlings after nine months from the plantation (Supplementary Table S3). The highest amount of fungal DNA was recorded in Q. robur seedlings mycorrhized in the nursery and planted without modifications (M) in PAL, while the lowest amount was found in Q. robur seedlings mycorrhized in the nursery and planted with sterile and inoculated substrate, with a separation diaphragm (MA) in MUG. Overall, the amount of fungal DNA was higher in seedlings without a diaphragm (F and M). In all seedlings subjected to the different treatments (A, M and MA), T. magnatum DNA was identified (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Total amount of fungal DNA found in the three study sites divided by treatment type. (F: only Q. robur; M: Q. robur mycorrhized in the nursery and planted; A: Q. robur + sterile and inoculated substrate + separation diaphragm; MA: Q. robur mycorrhized in the nursery + sterile and inoculated substrate + separation diaphragm; MON: Montespertoli; MUG: Mugello; PAL: Palaia; (*) Presence of Tuber magnatum DNA.

The analyses conducted on soil samples after 9 months of planting the oak seedlings reveal statistically significant differences in the amounts of T. magnatum extra-radical mycelium, both between the study sites (p < 0.05) and among the different treatments (p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Two-way ANOVA results for mycelial biomass production according to treatments and study sites.

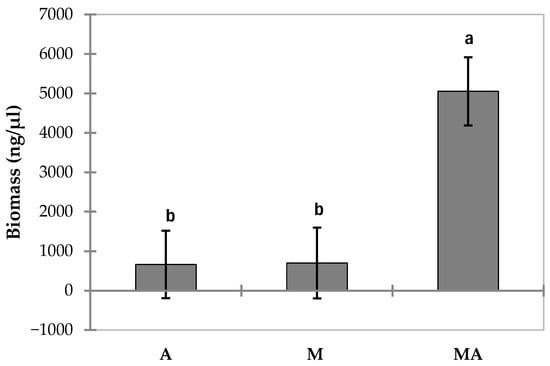

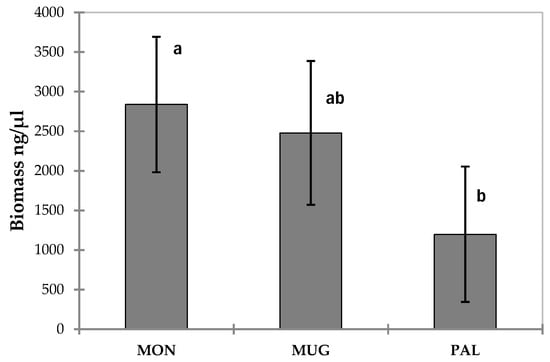

The MA (mycorrhized in the nursery and planted with sterile substrate + inoculum + separation diaphragm) developed a quantity of T. magnatum extra-radical mycelium significantly different from the other seedlings (Figure 5), even from those that had the same treatment (sterile substrate + inoculum + separation diaphragm), but were not mycorrhized in the nursery (A). Statistically significant differences were also found between the different study sites (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Total T. magnatum mycelial biomass (ng/μL) divided by individual treatments. (A: Q. robur + sterile and inoculated substrate + separation diaphragm; M: Q. robur mycorrhizal in nursery and planting). MA: Q. robur mycorrhizal in nursery + sterile and inoculated substrate + separation diaphragm; Error bars represent standard error (n = 127). Different letters indicate significant differences between treatments.

Figure 6.

Total T. magnatum mycelial biomass (ng/μL) divided by study fields (MON—Montespertoli; MUG—Mugello; PAL—Palaia). Error bars represent standard error (n = 127). Different letters indicate significant differences between study sites.

The results of the parallel test with the model species Tuber borchii showed that the extracted mycelium belonged to a single mating type, indicating that the applied technique was able to extract only hyphal DNA and not spore.

4. Discussion

Tracking the early development of Tuber magnatum extra-radical mycelium in open field plantations represents a novel and valuable contribution to truffle cultivation research. Until now, no previous study has systematically monitored mycelial abundance within the first year following planting under natural field conditions. This represents a significant advancement in understanding the early ecological dynamics and establishment potential of T. magnatum in managed environments.

In contrast, Bach et al. [2], who reported the establishment of the first productive T. magnatum plantation in France, conducted their initial mycelium quantification sampling only between three and seven years after planting, reflecting the traditionally long timelines associated with truffle cultivation studies. Similarly, Oliach et al. [13] investigated T. melanosporum mycelium development in relation to its spatial distribution from the host tree in a cultivated orchard, performing their first sampling five years after orchard establishment. In another study, Şen et al. [14] assessed the effects of mulching on T. melanosporum mycelial biomass, conducting sampling eight years after the truffle ground was established. These studies collectively highlight the typically protracted periods required before significant mycelial colonization and quantifiable development that can be detected in truffle cultivation systems.

To verify the treatment effects, the mycelium sampling in the three study fields was carried out 10 cm from the seedling and at a depth of 10 cm. The decision to conduct sampling for the quantification of the extra-radical mycelium of Tuber magnatum at a distance of 10 cm from the seedling is based both on the fact that the protective barrier used in treatments A and MA has a diameter of 20 cm and on the findings of [35]. In their study on the effects of different weed control strategies on the early development of Quercus ilex seedlings and their symbiosis with T. melanosporum, the authors observed that, two years after the establishment of the truffle ground, the highest concentration of mycelium was found at relatively short distances from the seedling (15–30 cm), rather than at greater distances (45–50 cm).

The decision to sample at a depth of 10 cm is consistent with the findings of [16], who, in their study on the vertical distribution of T. magnatum mycelium in natural truffle beds, reported that the highest concentration was found in the upper soil layer (0–10 cm). At greater depths, the amount of mycelium progressively decreased. These combined insights justified the methodological choices adopted in the present study and provide a solid framework for the interpretation of early mycelial colonization dynamics under experimental cultivation conditions.

The technique employed in this study was further validated by the parallel experiment with T. borchii, which demonstrated that spores were not extracted from the soil, thereby excluding their potential interference with mycelium quantification.

Quercus robur seedlings subjected to the MA treatment (Q. robur mycorrhized in the nursery + sterile and inoculated substrate + separation diaphragm) developed a significantly different amount of T. magnatum mycelium compared to all other treatments, including those that received the same planting method, but without prior mycorrhization (treatment A). This finding suggests that the planting technique involving sterile substrate, inoculum and separation barrier may be more effective if applied to plants in which the biological cycle of T. magnatum is already at a more advanced stage. This aligns with observations by [36], who emphasized the importance of early-stage mycorrhizal stability in enhancing truffle establishment and persistence in managed orchards. Although no studies have directly compared the effectiveness of planting seedlings already mycorrhized with Tuber species to that of inoculating non-mycorrhized seedlings with Tuber spores on site, it is well established that nursery-produced mycorrhizal seedlings promote a stable symbiotic relationship between the host plant and the fungus, while also limiting competition from other soil fungi. Modern truffle cultivation is based on the planting of well-colonized seedlings, produced under control greenhouse conditions in soils and climates suitable for truffle development [2]. Although the specific details of the inoculation process are secret, it is known that most commercially produced truffle-inoculated plants are generated by applying ascospore suspensions obtained from truffle mixtures [1]. Since ascospores are the result of sexual reproduction and each seedling receives approximately 106 spores, each plant is potentially colonized by a unique combination of fungal genotypes. This genetic diversity may offer a certain degree of adaptability to local conditions. This concept has recently been reinforced by [37], who reported that higher genotypic diversity within truffle-inoculated seedlings may enhance resilience against soil-borne fungal competitors and fluctuating environmental conditions.

The different study sites showed statistically significant differences in the amount of Tuber magnatum mycelium after nine months of the experiment, with the MON site exhibiting the highest abundance. Although multiple environmental factors may have contributed to this result, the higher clay and silt content in the soil at MON may have favored T. magnatum mycelium development. In fact, it is well known that T. magnatum prefers loamy or silty-clay soils that offer a good balance between water retention and drainage [4,16].

At present, no truffle-cultivation protocol for T. magnatum officially incorporates the use of separation diaphragms as a standard practice. Nonetheless, several experimental studies have investigated the use of physical soil barriers to better understand mycelial growth dynamics and microbial competition [37,38,39]. These approaches, however, have not yet been tested under field conditions nor adopted on a large scale in commercial truffle production. Current cultivation practices primarily rely on the use of nursery-produced mycorrhizal seedlings, soil preparation, and environmental management to promote truffle fruiting.

The cultivation of T. magnatum remains one of the most challenging endeavors in truffle farming due to a combination of biological, ecological, and technical constraints. Unlike T. melanosporum, whose life cycle is better understood and has been successfully cultivated in managed orchards, T. magnatum exhibits a highly specific set of ecological requirements and an elusive reproductive biology with a weak and often inconsistent relationship between mycorrhizas, extra-radical mycelium and fruiting body production [1,15]. Its symbiotic association with host plants is often unstable and difficult to maintain after transplanting into natural soils, where competition from native ectomycorrhizal fungi can outcompete or displace T. magnatum [38]. Moreover, the species requires narrowly defined edaphic conditions—calcareous, well-drained soils with specific pH and microclimatic parameters—which are not easily reproduced or maintained [36]. Importantly, the integration of host-tree symbioses, forest-soil characteristics and extracellular mycelial networks at the ecosystem level represents a particularly promising frontier for research.

5. Conclusions

The data presented here open promising new perspectives for the cultivation of Tuber magnatum. These results offer new insights into the optimization of forest management for cultivation of Tuber magnatum and indicate promising strategies to enhance mycelial development, a crucial step toward potentially increasing fruiting body production in managed forest environments. However, continued monitoring of mycelial development, seedling health and mycorrhizal status, as well as the various biotic and abiotic factors, will be essential to further clarify the complex developmental dynamics of this prized truffle species.

These early findings demonstrate that Tuber magnatum is capable of establishing extra-radical mycelium within the first year after planting, with responses influenced by planting technique and local site conditions. The MA treatment—mycorrhized seedlings combined with a sterile, inoculated substrate and a separation diaphragm—yielded the best results, showing the highest mycelial levels. This suggests the importance of using mycorrhized plants, implementing soil manipulation, and applying spore inoculation after planting. Future monitoring of these experimental sites will be essential to verify whether these early mycelial patterns translate into stable mycorrhization, sustained mycelial persistence, and ultimately the production of mature fruiting bodies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/f17010018/s1, Table S1: Specific Tuber primers used in this study. Table S2: Samples where T. magnatum mycelium (Tmag) was detected and presence of the other analyzed Tuber species: Tmac = T. maculatum; Tdry = T. dryophilum; Tbru = T. brumale; Tmel = T. melanosporum; Tbor = T. borchii; Taes = T. aestivum. For each site, the number of samples where a Tuber species was detected. Table S3: Summary of the results obtained: Study field—Montesertoli (MON); Mugello (MUG); Palaia (PAL). Treatment—A: Q. robur + sterile and inoculated substrate + separation diaphragm; MA: Q. robur mycorrhized in the nursery + sterile and inoculated substrate + separation diaphragm; M: Q. robur mycorrhized in the nursery and planted; F: only Q. robur. Tmag—Presence (1) or absence (0) of Tuber magnatum mycelium.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.S., L.G. (Lorenzo Gardin), L.G. (Laura Giannetti) and A.T.; methodology, E.S. and P.L.; software, E.S. and P.L.; formal analysis, P.L., A.A. and B.R.; investigation, E.S., P.L., L.C. and I.M.; data curation, E.S., P.L., A.Z. and C.P.; writing—original draft, E.S.; writing—review and editing, A.Z., A.A. and C.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the REGIONE TOSCANA as part of the project “Analysis of fungal mycelium in three experimental truffle cultivation plants in Tuscany”—2264-2023-SE-CONRICEPUB_003.

Data Availability Statement

The data is contained within the article and Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the farmers who collaborated in establishing the experimental fields and managing the cultivation practices.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The founders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of the data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Čejka, T.; Trnka, M.; Büntgen, U. Sustainable cultivation of the white truffle (Tuber magnatum) requires ecological understanding. Mycorrhiza 2023, 33, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, C.; Beacco, P.; Cammaletti, P.; Babel-Chen, Z.; Levesque, E.; Todesco, F.; Cotton, C.; Robin, B.; Murat, C. First production of Italian white truffle (Tuber magnatum Pico) ascocarps in an orchard outside its natural range distribution in France. Mycorrhiza 2021, 31, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marjanović, Ž.; Glišić, A.; Mutavdžić, D.; Saljnikov, E.; Bragato, G. Ecosystems supporting Tuber magnatum Pico production in Serbia experience specific soil environment seasonality that may facilitate truffle lifecycle completion. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 2015, 95, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragato, G.; Marjanović, Ž.S. Soil characteristics for Tuber magnatum. In True Truffle (Tuber spp.) in the World; Zambonelli, A., Iotti, M., Murat, C., Eds.; Soil Biology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 47, pp. 191–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello, A.; Fontana, A.; Meotto, F.; Comandini, O.; Bonfante, P. Molecular and morphological characterization of Tuber magnatum mycorrhizas in a long-term survey. Microbiol. Res. 2001, 155, 79–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubini, A.; Paolocci, F.; Granetti, B.; Arcioni, S. Morphological characterization of molecular-typed Tuber magnatum ectomycorrhizae. Mycorrhiza 2001, 11, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccioni, C.; Rubini, A.; Belfiori, B.; Gregori, G.; Paolocci, F. Tuber magnatum: The special one. What makes it so different from the other Tuber. In True Truffle (Tuber spp.); Zambonelli, A., Iotti, M., Murat, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 87–103. [Google Scholar]

- Landeweert, R.; Veenman, C.; Kuyper, T.W.; Fritze, H.; Wernars, K.; Smit, E. Quantification of ectomycorrhizal mycelium in soil by real-time PCR compared to conventional quantification techniques. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2003, 45, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallander, H.; Eklab, A.; Godbold, D.L.; Johnson, D.; Bahr, A.; Baldrian, P.; Björk, R.G.; Kieliszewska-Rokicka, B.; Kjøller, R.; Kraigher, H.; et al. Evaluation of methods to estimate production, biomass and turnover of ectomycorrhizal mycelium in forest soils—A review. Soil. Biol. Chem. 2013, 57, 1034–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uroz, S.; Ioannidis, P.; Lengelle, J.; Cébron, A.; Morin, E.; Buée, M.; Martin, F. Functional assays and metagenomic analyses reveal differences between the microbial communities inhabiting the soil horizons of a Norway spruce plantation. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e55929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parladé, J.; De la Varga, H.; Pera, J. Tools to trace truffles in soil. In True Truffle (Tuber spp.) in the World; Zambonelli, A., Iotti, M., Murat, C., Eds.; Soil Biology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 47, pp. 249–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iotti, M.; Leonardi, M.; Oddis, M.; Salerni, E.; Baraldi, E.; Zambonelli, A. Development and validation of a real-time PCR assay for detection and quantification of Tuber magnatum in soil. BMC Microbiol. 2012, 12, 12–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliach, D.; Colinas, C.; Castano, C.; Fischer, C.R.; Bolano, F.; Bonet, J.A.; Oliva, J. The influence of forest surroundings on the soil fungal community of black truffle (Tuber melanosporum) plantations. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 470–471, 118212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şen, İ.; Piñuela, Y.; Alday, J.G.; Oliach, D.; Bolaño, F.; Martínez de Aragón, J.; Colinas, C.; Bonet, J.A. Mulch removal time did not have significant effects on Tuber melanosporum mycelium biomass. For. Syst. 2021, 30, eSC02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampieri, E.; Murat, C.; Cagnasso, M.; Bonfante, P.; Mello, A. Soil analysis reveals the presence of an extended mycelial network in a Tuber magnatum truffle-ground. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2010, 71, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iotti, M.; Leonardi, P.; Vitali, G.; Zambonelli, A. Effect of summer soil moisture and temperature on the vertical distribution of Tuber magnatum mycelium in soil. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2018, 54, 707–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regione Toscana. SIPT: Database Pedologico. Available online: https://www502.regione.toscana.it/geoscopio/pedologia.html (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Regione Toscana. SIPT: Database Geologico. Available online: https://www502.regione.toscana.it/geoscopio/geologia.html (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Regione Toscana. SIPT: Database Uso e Copertura del Suolo. Available online: https://www502.regione.toscana.it/geoscopio/usocoperturasuolo.html (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Laboratorio di Monitoraggio e Modellistica Ambientale (LaMMA). Available online: https://www.lamma.toscana.it/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Thornthwaite, C.W. An Approach toward a Rational Classification of Climate. Geogr. Rev. 1948, 38, 55–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUSS Working Group WRB. World Reference Base for Soil Resources 2014, Update 2015; International Soil Classification System for Naming Soils and Creating Legends for Soil Maps; World Soil Resources Reports FAO: Rome, Italy, 2015; Volume 106. [Google Scholar]

- Colombo, C.; Miano, T. Metodi di Analisi Chimica del Suolo, 3rd ed.; Società Italiana di Scienza del Suolo: Firenze, Italy, 2015; pp. 1–470. [Google Scholar]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, J.L. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications; Innis, M.A., Gelfand, D.H., Sninsky, J.J., White, T.J., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1990; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardes, M.; Bruns, T.D. ITS primers with enhanced specificity for basidiomycetes—Application to the identification of mycorrhizae and rusts. Mol. Ecol. 1993, 2, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello, A.; Cantisani, A.; Vizzini, A.; Bonfante, P. Genetic variability of Tuber uncinatum and its relatedness to other black truffles. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 4, 584–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amicucci, A.; Zambonelli, A.; Giomaro, G.; Potenza, L.; Stocchi, V. Identification of ectomycorrhizal fungi of the genus Tuber by species-specific ITS primers. Mol. Ecol. 1998, 7, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolocci, F.; Rubini, A.; Granetti, B.; Arcioni, S. Rapid molecular approach for a reliable identification of Tuber spp. ectomycorrhizae. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 1999, 28, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amicucci, A.; Guidi, C.; Zambonelli, A.; Potenza, L.; Stocchi, V. Multiplex PCR for the identification of white Tuber species. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2000, 189, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benucci, G.M.N.; Raggi, L.; Di Massimo, G.; Baciarelli-Falini, L.; Bencivenga, M.; Falcinelli, M.; Albertini, E. Species-specific primers for the identification of the ectomycorrhizal fungus Tuber macrosporum Vittad. Mol. Ecol. Res. 2011, 11, 378–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belfiori, B.; Riccioni, C.; Paolocci, F.; Rubini, A. Characterization of the reproductive mode and life cycle of the whitish truffle T. Borchii. Mycorrhiza 2016, 26, 515–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolocci, F.; Rubini, A.; Riccioni, C.; Arcioni, S. Reevaluation of the Life Cycle of Tuber magnatum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 2390–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, P.; Murat, C.; Puliga, F.; Iotti, M.; Zambonelli, A. Ascoma genotyping and mating type analyses of mycorrhizas and soil mycelia of Tuber borchii in a truffle orchard established by mycelial inoculated plants. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 22, 964–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Miguel, A.M.; Agueda, B.; Sanchez, S.; Parlade, J. Ectomycorrhizal fungus diversity and community structure with natural and cultivated truffle hosts: Applying lessons learned to future truffle culture. Mycorrhiza 2014, 24, S5–S18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivera, A.; Bonet, J.A.; Palacio, L.; Liu, B.; Colinas, C. Weed control modifies Tuber melanosporum mycelial expansion in young oak plantations. Ann. For. Sci. 2014, 71, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonito, G.; Smith, M.E.; Nowak, M.; Healy, R.A.; Guevara, G.; Cázares, E.; Vilgalys, R. Historical biogeography and diversification of truffles in the Tuberaceae and their newly identified southern hemisphere sister lineage. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e5278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Kuzyakov, Y. Mechanisms and implications of bacterial-fungal competition for soil resources. ISME J. 2024, 18, wrae073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teste, F.P.; Karst, J.; Jones, M.D.; Simard, S.W.; Durall, D.M. Methods to control ectomycorrhizal colonization: Effectiveness of chemical and physical barriers. Mycorrhiza 2006, 17, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandolini, E.; Probst, M.; Peintner, U. Methods for Studying Bacterial–Fungal Interactions in the Microenvironments of Soil. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.