Can Culture Imaging Implement Radial Growth Parameters to Disentangle Intraspecific Variability in Fomes fomentarius?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

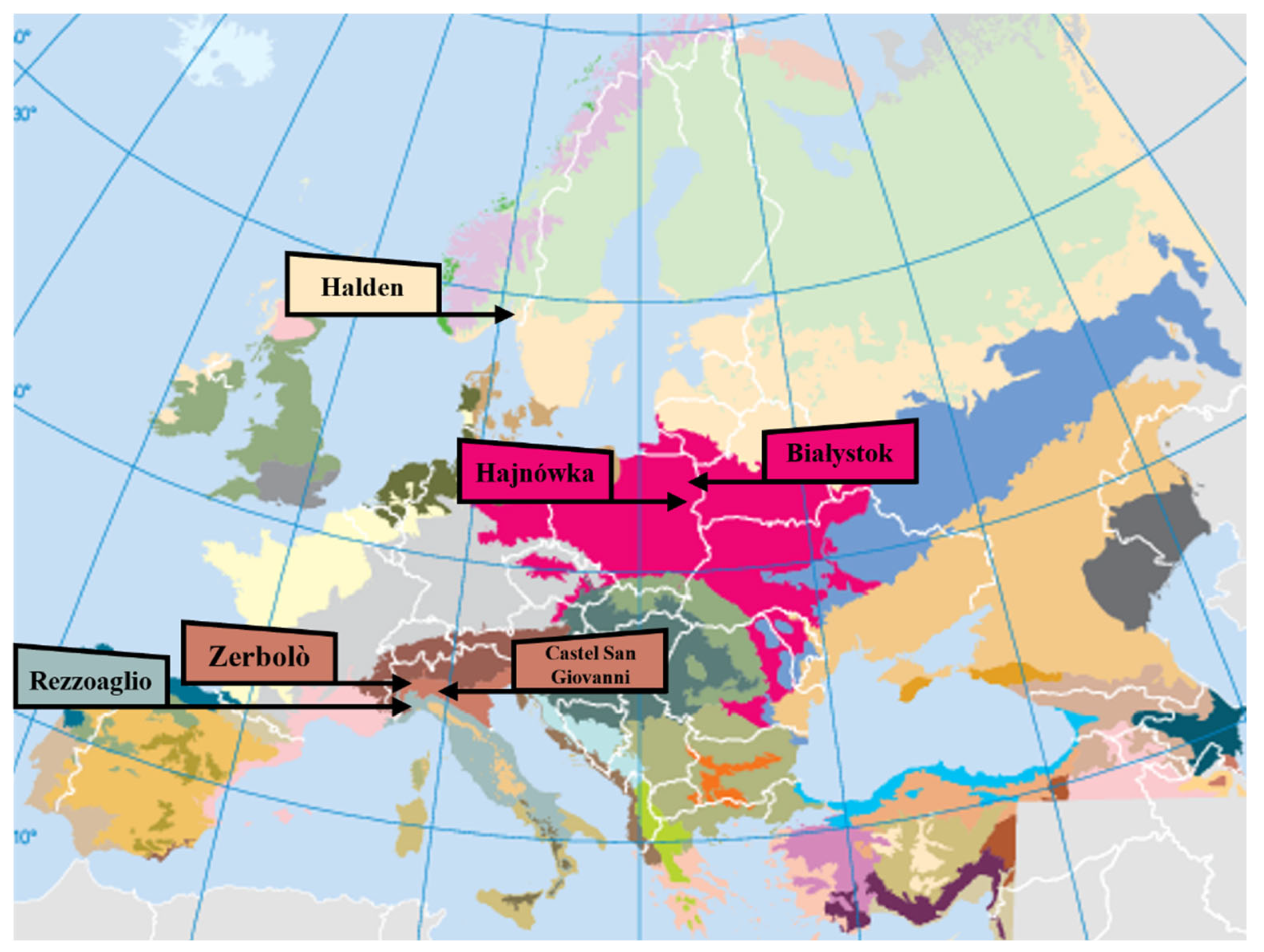

2.1. Strains in the Study

2.2. Growth Tests of Mycelia in Pure Culture

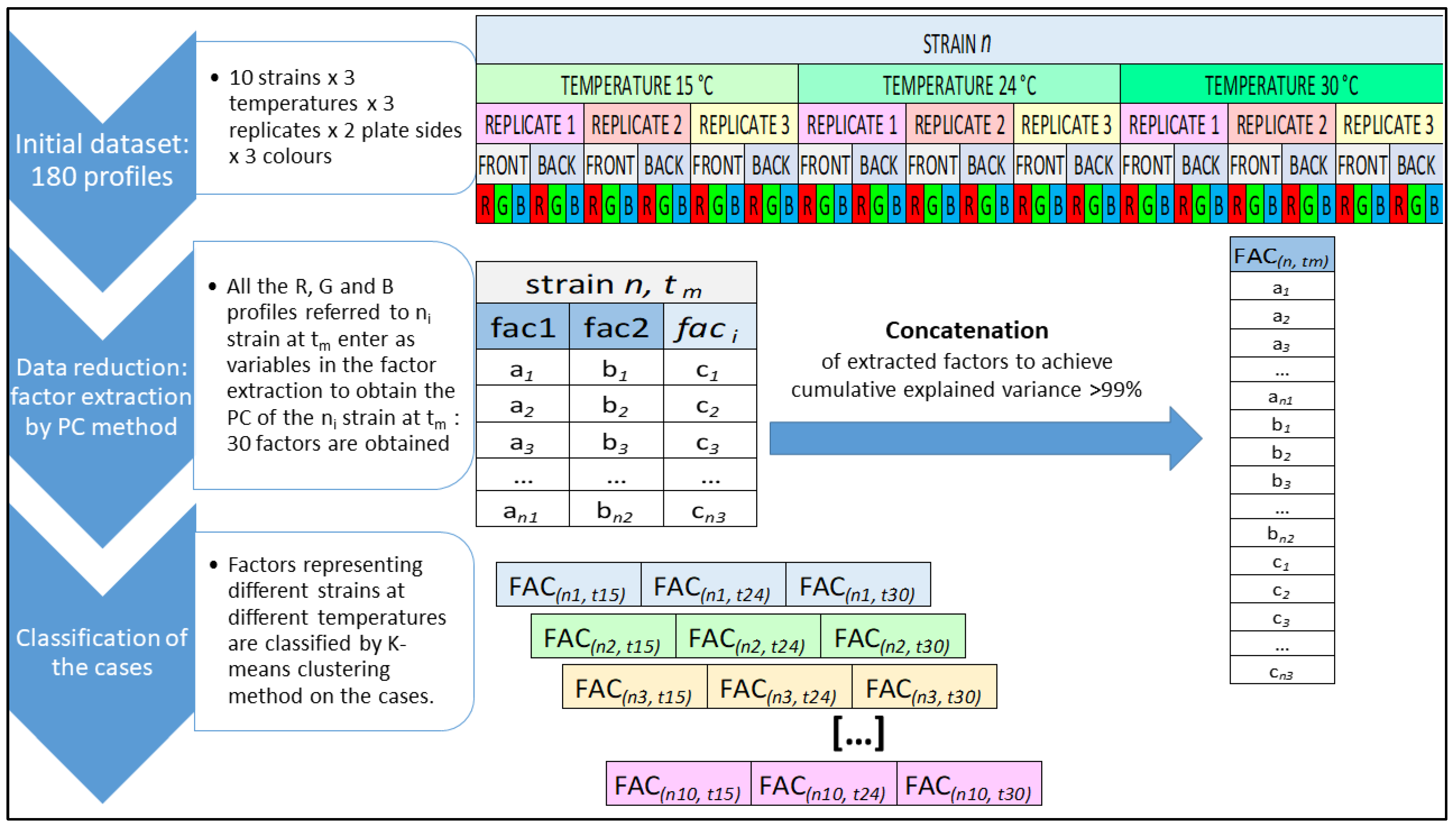

2.3. RGB Imaging and Analysis of RGB Profiles

3. Results

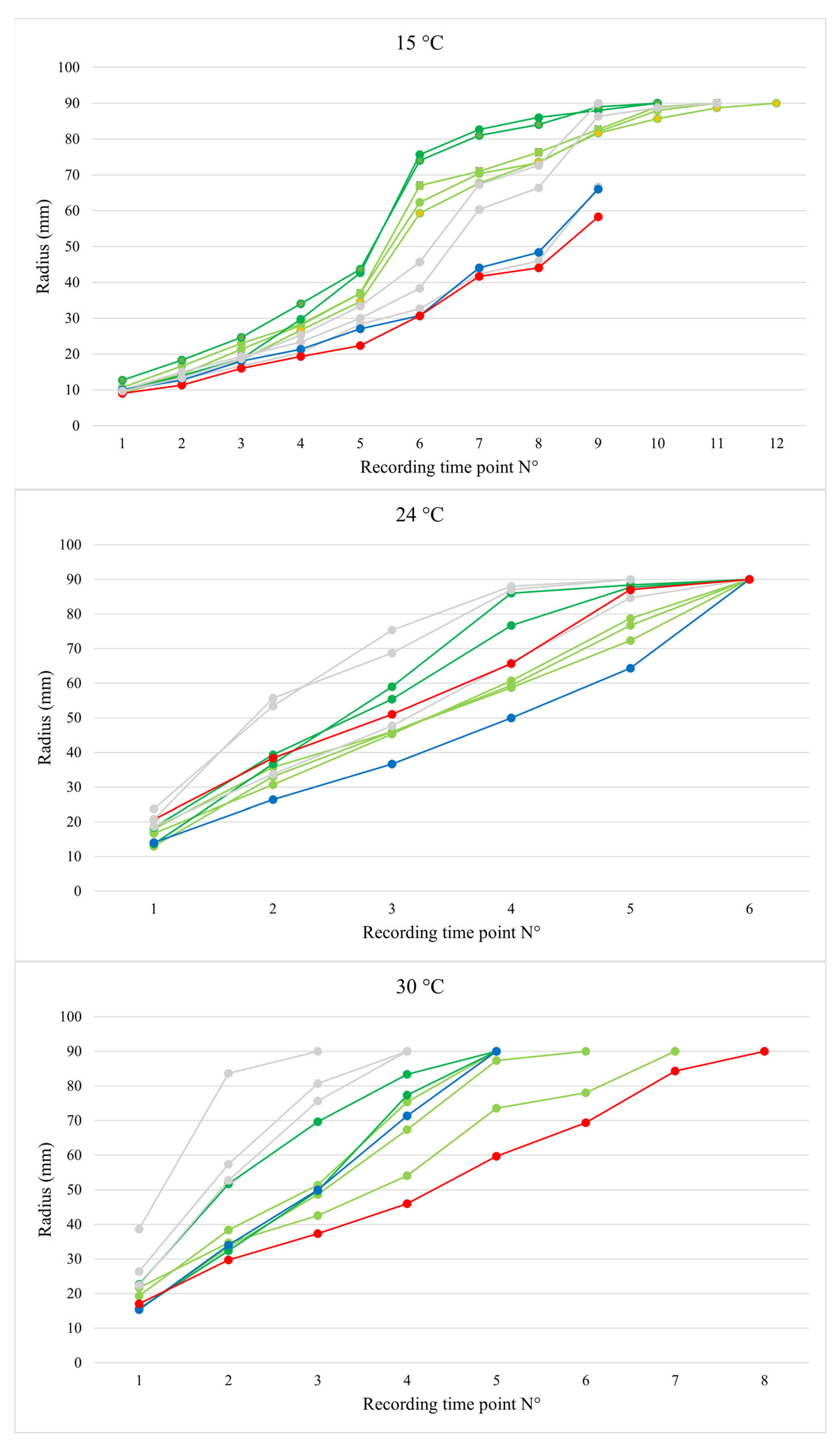

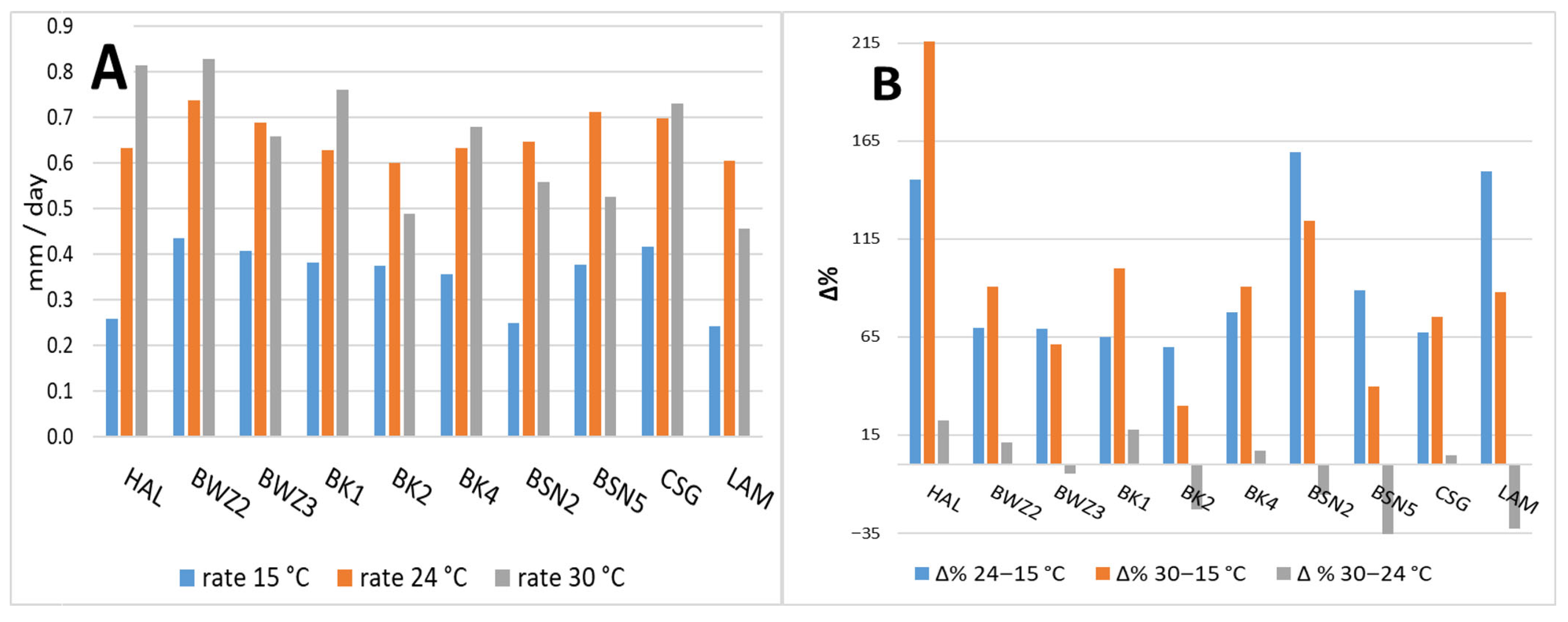

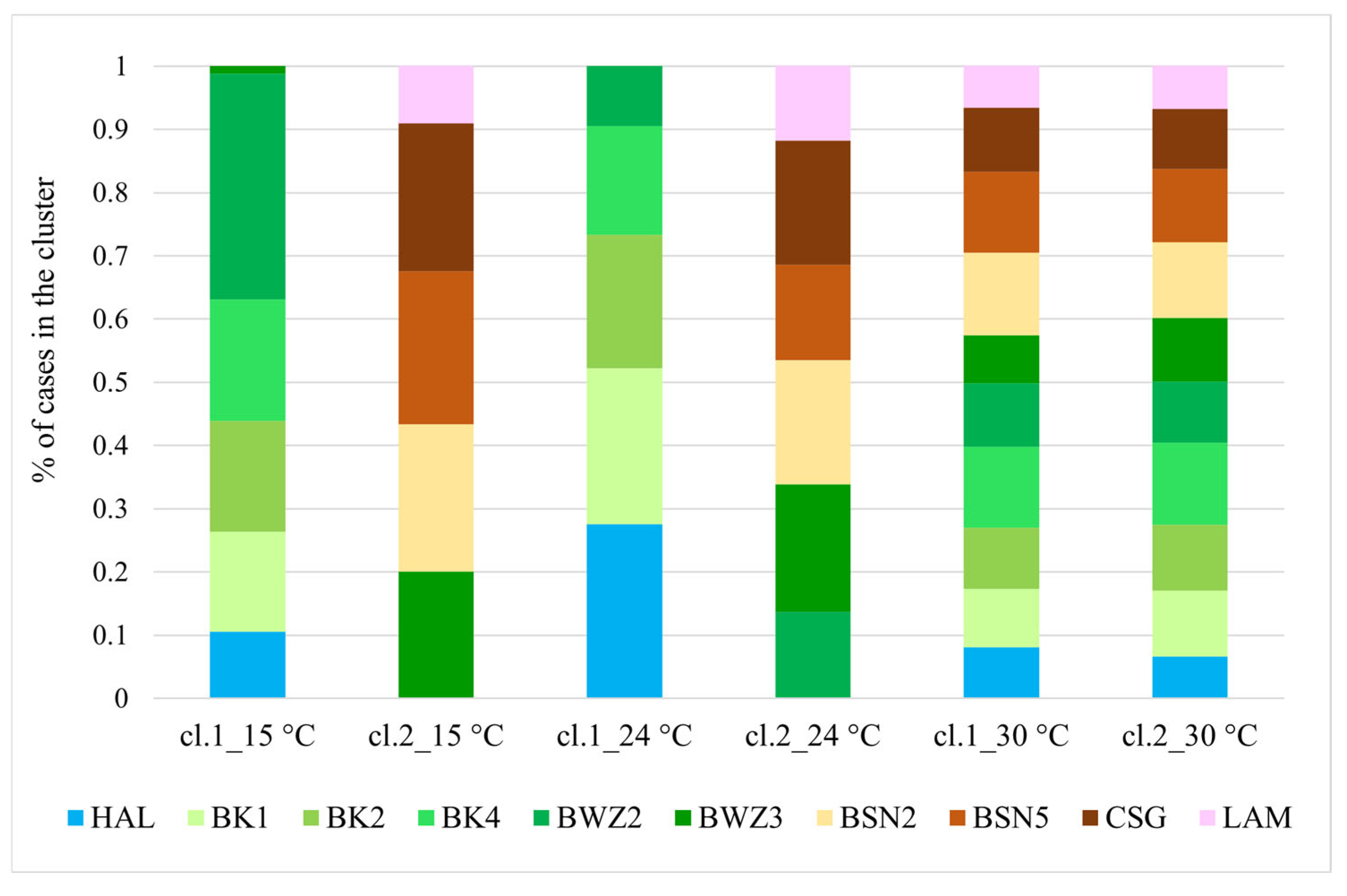

3.1. Growth Tests

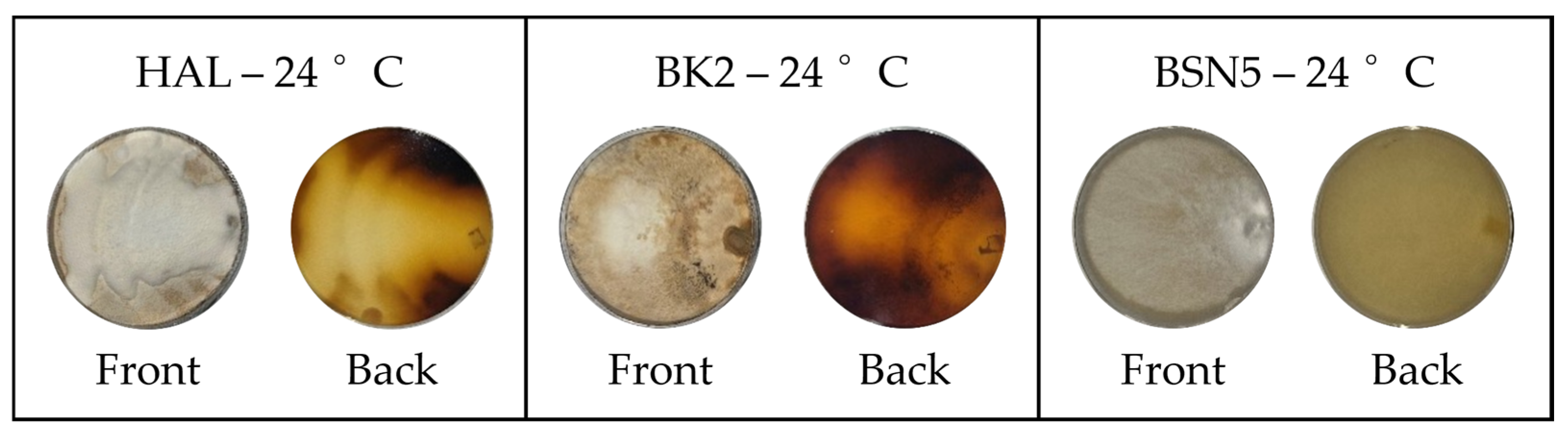

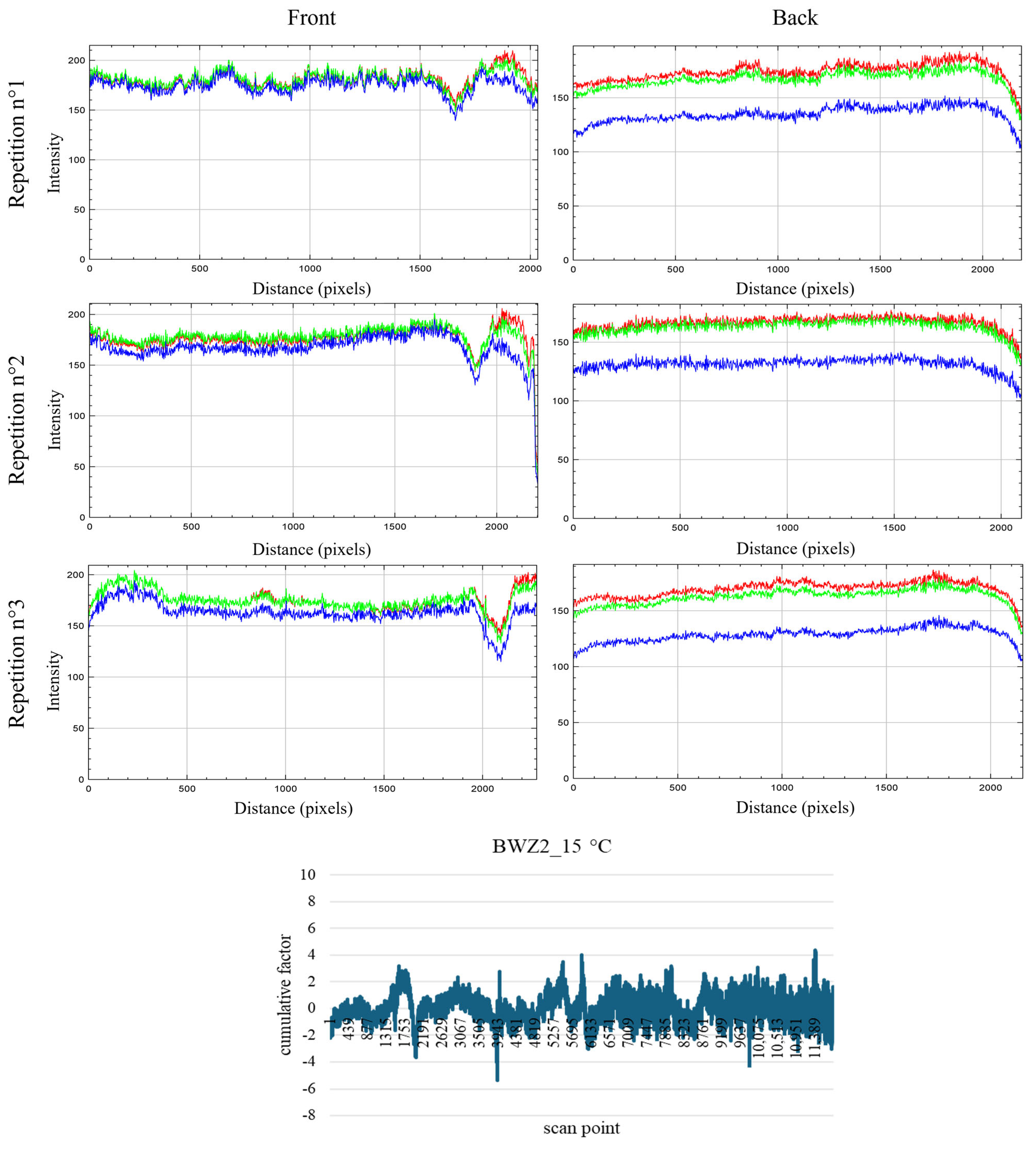

3.2. RGB Imaging and RGB Profiles

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McCormick, M.A.; Cubeta, M.A.; Grand, L.F. Geography and hosts of the wood decay fungi Fomes fasciatus and Fomes fomentarius in the United States. N. Am. Fungi 2013, 8, 1–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryvarden, L.; Melo, I. Poroid Fungi of Europe, 2nd ed.; Fungiflora: Oslo, Norway, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bernicchia, A.; Gorjón, S.P. Polypores of the Mediterranean Region; Romar: Segrate, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gáperová, S.; Gáper, J.; Gallay, I.; Pristaš, P.; Slobodník, B. Spatial distribution and host preferences of Fomes fomentarius and F. inzengae in Europe: A review. Folia Oecol. 2025, 52, 202–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBIF. Available online: https://www.gbif.org/ (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Schwarze, F.W. Wood decay under the microscope. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2007, 21, 133–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judova, J.; Dubikova, K.; Gaperova, S.; Gaper, J.; Pristas, P. The occurrence and rapid discrimination of Fomes fomentarius genotypes by ITS-RFLP analysis. Fungal Biol. 2012, 116, 155e160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peintner, U.; Kuhnert-Finkernagel, R.; Wille, V.; Biasioli, F.; Shiryaev, A.; Perini, C. How to resolve cryptic species of polypores: An example in Fomes. IMA Fungus 2019, 10, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badalyan, S.; Zhuykova, E.; Mukhin, V. The phylogenetic analysis of Armenian collections of medicinal tinder polypore Fomes fomentarius (Agaricomycetes, Polyporaceae). Ital. J. Mycol. 2022, 51, 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Tomšovský, M.; Kaeochulsri, S.; Kudláček, T.; Dálya, L.B. Ecological, morphological and phylogenetic survey of Fomes fomentarius and F. inzengae (Agaricomycetes, Polyporaceae) co-occurring in the same geographic area in Central Europe. Mycol. Prog. 2023, 22, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logar, R.; Gostinčar, C.; Turk, M.; Grebenc, T. Combination of hosts and geographic origin affect the differentiation in Fomes fomentarius species complex. In Proceedings of the XIX Congress of European Mycologists, Perugia, Italy, 4–8 September, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Stalpers, J.A. Identification of wood-inhabiting Aphyllophorales in pure culture. Stud. Mycol. 1978, 16, 248. [Google Scholar]

- BLAST NCBI. Available online: https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Girometta, C.E.; Buratti, S.; Bernicchia, A.; Desiderio, A.; Goppa, L.; Perini, C.; Salerni, E.; Savino, E. The research culture collection of Italian wood decay fungi: A tool for different studies and applications. Ital. J. Mycol. 2024, 53, 85–98. [Google Scholar]

- Girometta, C.E.; Bernicchia, A.; Baiguera, R.M.; Bracco, F.; Buratti, S.; Cartabia, M.; Picco, A.M.; Savino, E. An Italian research culture collection of wood decay fungi. Diversity 2020, 12, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San-Miguel-Ayanz, J.; de Rigo, D.; Caudullo, G.; Houston Durrant, T.; Mauri, A. European Atlas of Forest Tree Species; Publication Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Geoportale Nazionale—Ministero dell’Ambiente. Available online: https://gn.mase.gov.it/portale/home (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Blasi, C.; Capotorti, G.; Copiz, R.; Guida, D.; Mollo, B.; Smiraglia, D.; Zavattero, L. Classification and mapping of the ecoregions of Italy. Plant Biosyst. 2014, 148, 1255–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO—Food and Agriculture Organization. Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/ad652e/ad652e21.htm (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- DMEER: Digital Map of European Ecological Regions—European Environment Agency. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/maps-and-charts/dmeer-digital-map-of-european-ecological-regions (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- ClimateData. Available online: https://en.climate-data.org/ (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Buratti, S.; Girometta, C.E.; Savino, E.; Gorjón, S.P. An Example of the Conservation of Wood Decay Fungi: The New Research Culture Collection of Corticioid and Polyporoid Strains of the University of Salamanca (Spain). Forests 2023, 14, 2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliani, L.; Giavelli, G.; Manfredini, M. Statistica Applicata alla Ricerca Biologica e Ambientale; UNI.NOVA: Parma, Italy, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- ImageJ. Available online: https://imagej.net/ij/ (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Afifi, A.; May, S.; Donatello, R.; Clark, V.A. Practical Multivariate Analysis, 6th ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, L.; Rousseeuw, P.J. Finding Groups in Data: An Introduction to Cluster Analysis; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Girometta, C.E.; Dondi, D.; Baiguera, R.M.; Bracco, F.; Branciforti, D.S.; Buratti, S.; Lazzaroni, S.; Savino, E. Characterization of mycelia from wood-decay species by TGA and IR spectroscopy. Cellulose 2020, 27, 6133–6148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Xia, Y. Melanin in fungi: Advances in structure, biosynthesis, regulation, and metabolic engineering. Microb. Cell Fact. 2024, 23, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudor, D.; Robinson, S.C.; Cooper, P.A. The influence of moisture content variation on fungal pigment formation in spalted wood. Amb. Express 2012, 2, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Xue, J.; Shi, J.; Li, T.; Yuan, H. Comparative transcriptome analysis explores the mechanism of angiosperm and gymnosperm deadwood degradation by Fomes fomentarius. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, T.; Freidank-Pohl, C.; Birke, A.S.; Regner, C.; Jung, S.; Meyer, V. Uncovering the transcriptional landscape of Fomes fomentarius during fungal-based material production through gene co-expression network analysis. Fungal Biol. Biotechnol. 2025, 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedotov, O.V.; Veligodska, A.K. Search producers of polyphenols and some pigments among Basidiomycetes. Biotechnologia Acta 2014, 7, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climate ADAPT, Sito Ufficiale dell’Unione Europea per L’ambiente. Available online: https://climate-adapt.eea.europa.eu/it/knowledge/european-climate-data-explorer/agriculture?set_language=it (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Bernicchia, A. Polyporaceae sl; Candusso: Alassio, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Botti, D. A phytoclimatic map of Europe. CYBERGEO 2018, 29495, 134885648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FloraVeg EU. Available online: https://floraveg.eu/ (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Orsenigo, S.; Mondoni, A.; Rossi, G.; Abeli, T. Some like it hot and some like it cold, but not too much: Plant responses to climate extremes. Plant Ecol. 2014, 215, 677–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J.J.; Demmig-Adams, B.; Cohu, C.M.; Wenzl, C.A.; Muller, O.; Adams, W.W., III. Growth temperature impact on leaf form and function in Arabidopsis thaliana ecotypes from northern and southern Europe. Plant Cell Environ. 2016, 39, 1549–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaszek, M.; Żuchowski, J.; Dajczak, E.; Cimek, K.; Gra̢z, M.; Grzywnowicz, K. Ligninolytic enzymes can participate in a multiple response system to oxidative stress in white-rot basidiomycetes: Fomes fomentarius and Tyromyces pubescens. Int. Biodeter. Biodegrad. 2006, 58, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strain | Micunipv Code | Substrate | Municipality | Country | Ecological Zone | Coordinates | Genbank Accession |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAL | MicUNIPV F.f.19 | Betula sp. | Halden | Norway | Temperate oceanic | 11.52766 E, 59.13508 N | PX663061 |

| BWZ2 | MicUNIPV F.f.24 | Fraxinus excelsior L. | Hajnówka * | Poland | Temperate continental | 23.59680 E, 52.72841 N | PX663056 |

| BWZ3 | MicUNIPV F.f.25 | Fraxinus excelsior | Hajnówka * | Poland | Temperate continental | 23.59515 E, 52.72786 N | PX663057 |

| BK1 | MicUNIPV F.f.20 | Betula pendula Roth | Białystok | Poland | Temperate continental | 23.15216 E, 53.11513 N | PX663058 |

| BK2 | MicUNIPV F.f.21 | Betula pendula | Białystok | Poland | Temperate continental | 23.15170 E, 53.11333 N | PX663059 |

| BK4 | MicUNIPV F.f.22 | Betula pendula | Białystok | Poland | Temperate continental | 23.15160 E, 53.11409 N | PX663060 |

| BSN2 | MicUNIPV F.f.4 | Quercus robur L. | Zerbolò ** | Italy | Temperate oceanic | 9.05667 E, 45.21126 N | PX663063 |

| BSN5 | MicUNIPV F.f.18 | Corylus avellana L. | Zerbolò ** | Italy | Temperate oceanic | 9.05823 E, 45.21180 N | PX663064 |

| CSG | MicUNIPV F.f.7 | Tilia sp. | Castel San Giovanni ** | Italy | Temperate oceanic | 9.43493 E, 45.06064 N | PX663062 |

| LAM | MicUNIPV F.f.10 | Sorbus aucuparia L. | Rezzoaglio *** | Italy | Temperate mountain | 9.39129 E, 44.48951 N | PX663065 |

| Strain | Mean Temperature °C (Min-Max) | Precipitation (mm) | Humidity (%) | Rainy Days (d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAL | 7.2 (4.3–10) | 74.2 | 0.8 | 8.5 |

| BWZ2 | 8.3 (4.6–11.6) | 59.3 | 0.8 | 8.3 |

| BWZ3 | 8.3 (4.6–11.6) | 59.3 | 0.8 | 8.3 |

| BK1 | 8.2 (4.5–11.6) | 59.6 | 0.8 | 8.5 |

| BK2 | 8.2 (4.5–11.6) | 59.6 | 0.8 | 8.5 |

| BK4 | 8.2 (4.5–11.6) | 59.6 | 0.8 | 8.5 |

| BSN2 | 13.8 (9.3–18.5) | 90.5 | 0.7 | 6.8 |

| BSN5 | 13.8 (9.3–18.5) | 90.5 | 0.7 | 6.8 |

| CSG | 13.9 (9.5–18.5) | 80.3 | 0.7 | 7.0 |

| LAM | 9.8 (6.7–13) | 122.4 | 0.8 | 9.3 |

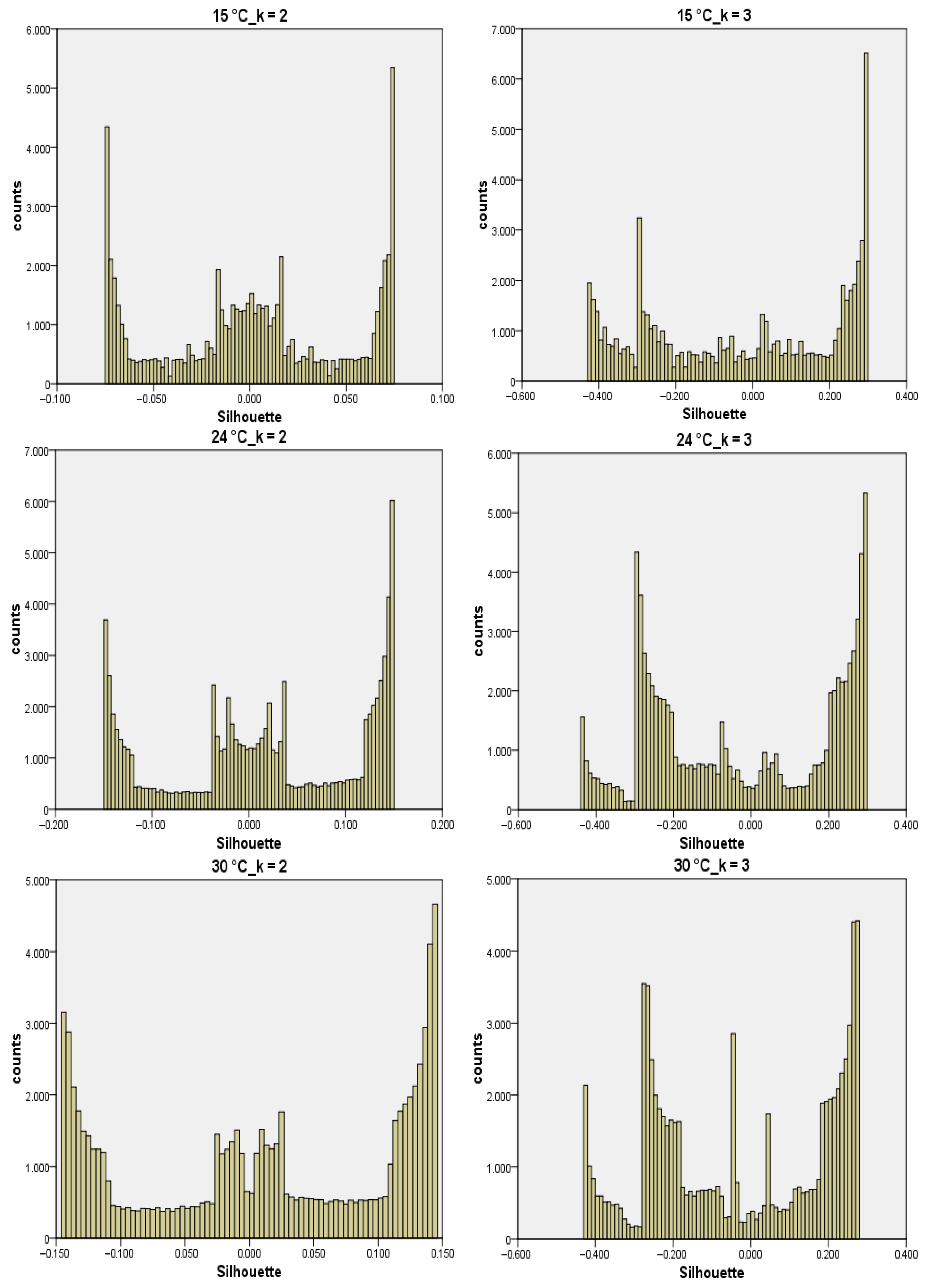

| 15 °C | 24 °C | 30 °C | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k = 2 | k = 3 | k = 2 | k = 3 | k = 2 | k = 3 | |

| cluster 1 | −0.037 | +0.215 | −0.069 | −0.235 | −0.083 | +0.206 |

| cluster 2 | +0.039 | −0.195 | +0.079 | +0.218 | +0.089 | −0.248 |

| cluster 3 | - | −0.263 | - | −0.213 | - | −0.194 |

| mean | +0.002 | −0.025 | +0.017 | −0.022 | +0.014 | −0.028 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Girometta, C.E.; Buratti, S.; Akridiss, H.; Zapora, E.; Wołkowycki, M.; Yurchenko, E.; Skowron, D.; Nicola, L. Can Culture Imaging Implement Radial Growth Parameters to Disentangle Intraspecific Variability in Fomes fomentarius? Forests 2026, 17, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010019

Girometta CE, Buratti S, Akridiss H, Zapora E, Wołkowycki M, Yurchenko E, Skowron D, Nicola L. Can Culture Imaging Implement Radial Growth Parameters to Disentangle Intraspecific Variability in Fomes fomentarius? Forests. 2026; 17(1):19. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010019

Chicago/Turabian StyleGirometta, Carolina Elena, Simone Buratti, Hajar Akridiss, Ewa Zapora, Marek Wołkowycki, Eugene Yurchenko, Daniel Skowron, and Lidia Nicola. 2026. "Can Culture Imaging Implement Radial Growth Parameters to Disentangle Intraspecific Variability in Fomes fomentarius?" Forests 17, no. 1: 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010019

APA StyleGirometta, C. E., Buratti, S., Akridiss, H., Zapora, E., Wołkowycki, M., Yurchenko, E., Skowron, D., & Nicola, L. (2026). Can Culture Imaging Implement Radial Growth Parameters to Disentangle Intraspecific Variability in Fomes fomentarius? Forests, 17(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010019