Abstract

This study explores the potential for afforestation in Portugal that could balance wood and non-wood forest production under future climate change scenarios. The Climate Envelope Models (CEM) approach was employed with three main objectives: (1) to model the current distribution of key Portuguese forest species—eucalypts, maritime pine, umbrella pine, chestnut, and cork oak—based on their suitability for wood and non-wood production; (2) to project their potential distribution for the years 2070 and 2090 under two Shared Socioeconomic Pathway (SSP) scenarios: SSP2–4.5 (moderate) and SSP5–8.5 (high emissions); and (3) to generate integrated species distribution maps identifying both current and future high-suitability zones to support afforestation planning, reflecting climatic compatibility under fixed thresholds. Species’ current CMEs were produced using an additive Boolean model with a set of environmental variables (e.g., temperature-related and precipitation-related, elevation, and soil) specific to each species. Species’ current CEMs were validated using forest inventory data and the official Land Use and Land Cover (LULC) map of Portugal, and a good agreement was obtained (>99%). By the end of the 21st century, marked reductions in species suitability are projected, especially for chestnut (36%–44%) and maritime pine (25%–35%). Incorporating future suitability projections and preventive silvicultural practices into afforestation planning is therefore essential to ensure climate-resilient and ecologically friendly forest management.

1. Introduction

Afforestation has been recognized as a valuable, cost-effective, and readily available option for mitigating climate change by carbon sequestration and providing various environmental benefits [1,2,3,4,5]. Effective afforestation planning requires comprehensive knowledge of the current and projected distributions of species, biological communities, and habitats under future climate change scenarios. Ecological niche modeling provides a fundamental framework for achieving this understanding.

A range of modeling approaches has been employed to estimate species distributions, including Climate Envelope Models (CEMs) and Species Distribution Models (SDMs). CEMs rely on the concept of habitat envelopes, which characterize the relationship between species’ observed distributions and environmental variables, typically without the need for detailed presence data [6]. So, CEMs are instrumental in predicting species ranges based on climate conditions by (i) assisting in understanding the fundamental ecological requirements of species; (ii) extrapolating these requirements into other geographical regions; and (iii) offering valuable insights into species distribution and its responses to environmental changes [7,8]. Indeed, climate change has caused shifts in the climate envelopes of many forest species [9,10], with scenarios showing shifts in species distributions, including latitudinal and altitudinal movements, or even the disappearance of critical climate types [11,12,13,14]. Moreover, CEMs represent potential climatic envelopes under equilibrium assumptions, excluding biotic interactions, dispersal constraints, and management effects. The SDMs employ several statistical modeling techniques to predict past, current, and future species distributions, utilizing species presence/absence data and relating these occurrences to environmental variables. As a result, the SDMs’ predictions are closely tied to the species distribution, climate, soil, and land cover datasets; model explanatory variable selection; and the choice of the Global Climate Model (GCM) and climate scenario used in the modeling process [15].

A previous study comparing Climate Envelope Models and Species Distribution Models for maritime pine in Portugal under current conditions and future projections for 2070 using two climate change scenarios (RCP 4.5 and RCP 8.5) showed that the CEM approach produced species distribution predictions closer to the species’ empirical potential distribution. This is because CEMs rely exclusively on threshold values of environmental variables that define the species’ ecological envelope [16]. In contrast, the SDM developed using a machine learning approach based on the maximum entropy algorithm (MaxEnt) yielded predictions that more closely matched the species’ current known distribution, as species occurrence data were derived from the official Land Use and Land Cover (LULC) map. Concordance between the two modeling approaches ranged from 44% under current conditions to over 30% in future projections (2070) [16]. Overall, the CEM approach likely provides advantages in validating physiological limits, reducing uncertainty, and enhancing the ecological robustness and transferability of projections, particularly in the context of climate change [17].

Currently, in mainland Portugal, the forest area (36%; 3.2 million ha) is mainly composed of eucalypts (Eucalyptus L’Hér.; 845 × 103 ha; 26%), cork oak (Quercus suber L.; 720 × 103 ha; 22%), maritime pine (Pinus pinaster Aiton; 713 × 103 ha; 22%), and holm oak (Quercus rotundifolia Lam.; 349 × 103 ha; 11%). The remaining forest area is occupied by other oaks (e.g., Quercus pyrenaica Willd., Quercus faginea Lam., and Quercus robur L.; 82 × 103 ha; 3%), umbrella pine (Pinus pinea L.; 194 × 103 ha; 6%), chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.; 48 × 103 ha; 2%), other broadleaved trees, and other coniferous trees [18] (see Supplementary Table S1 for studied species description).

The main wood-production species in Portugal, eucalypts (mainly Eucalyptus globulus Labill. ssp. globulus) and maritime pine (Pinus pinaster) (IFN6, [18]), are expected to be significantly affected by climate change by the end of the 21st century. Climate Envelope Models (CEMs) developed for these species under current conditions and future projections (2025 and 2070) using two climate change scenarios (RCP 4.5 and RCP 8.5) are already available and provide valuable support for afforestation planning [16,19,20]. In contrast, umbrella pine, chestnut, and cork oak are classified as non-wood production species in Portugal, according to IFN6 [18], due to the main products obtained (non-timber ones). Assessing the impacts of climate change on the suitability of these species is therefore essential for formulating effective recommendations to ensure their successful integration into future afforestation programs.

Indeed, over recent decades, the area occupied by Eucalyptus spp. has increased by approximately 127,000 ha, while Pinus pinea has expanded by about 73,000 ha. The smallest increase was observed in Castanea sativa, with a gain of just over 15,000 ha. Although modest in absolute terms, this increase partly reflects the recovery or expansion of chestnut cultivation driven by the growing economic importance of chestnut production [21]. In contrast, Pinus pinaster has experienced a substantial decline, losing nearly 265,000 ha over the past two decades. This sharp reduction reflects shifts in land use and the replacement of maritime pine by faster-growing species. Quercus suber also showed a slight decrease in area (approximately 27,000 ha); however, it continues to occupy extensive regions. Overall, these trends highlight significant changes in forest management practices, species economic value, and land-use dynamics, including rural abandonment, wildfire impacts, and an increasing preference for fast-growing species.

The updated integration adopted in this study was motivated by several key considerations. First, it enables the assessment of species responses to climate change using the most recent climate models. Second, forest composition in Portugal has changed substantially, with a marked reduction in maritime pine area and an increase in other forest species. Third, increasing wildfire and drought risk underscores the need for ecologically friendly solutions, such as the establishment of landscape mosaics or mixed forests. These mosaic-based plantations with adapted species can enhance biodiversity while helping to buffer wildfire severity and risk, as well as increasing resilience to drought.

The forest species inventory data (IFN6) [18] were employed, together with the official Land Use and Land Cover (LULC) map (COS 2018) [22], to validate species’ current CEMSs and to inform afforestation planning and management strategies under projected climate change scenarios. Since CEMs, which are based on literature-validated approaches, overcome SMDs in the context of climate change, we employed this approach for modeling. The main objectives were (1) to model the current distributions of key Portuguese wood and non-wood production species—eucalypts, maritime pine, umbrella pine, chestnut, and cork oak; (2) to project their potential distributions for 2070 and 2090 under the SSP2–4.5 and SSP5–8.5 climate scenarios; and (3) to produce distribution maps identifying high-suitability zones for current and future mosaic afforestation planning in Portugal to increase buffer zones for wildfires occurrence and drought resistance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

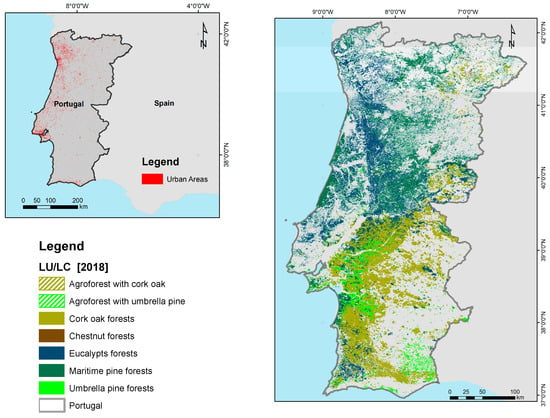

This study focused on mainland Portugal (36.9636° N, 9.4944° W to 42.1543° N, 6.1892° W) and examined key Portuguese wood and non-wood production species: eucalypts (Eucalyptus L’Hér.), maritime pine (Pinus pinaster Aiton), umbrella pine (Pinus pinea L.), chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.), and cork oak (Quercus suber L.) (Figure 1). Climate Envelope Models (CEMs) were developed for both current conditions and future periods (2070 and 2090) under two climate change scenarios, SSP2–4.5 and SSP5–8.5, to support comprehensive key recommendations for afforestation planning in Portugal for all those species.

Figure 1.

The study area with the current distribution of the focal species: mainland Portugal. “+” is the latitude and longitude crossing.

2.2. Environmental Data

The WorldClim version 2.1 (spatial resolution of 1 km) [23] allowed us to download the bioclimatic variables for the current (generated with data collected during the period between 1970 and 2000). The projected climate variables were downloaded from the EC-Earth3 -Veg model for 2070 and 2090 [24]. The EC-Earth Model is an Earth System Model (ESM) that comprises models of coupled components for atmosphere, ocean, sea ice, and land [24]. Earth System Models (ESMs) are the primary tools for understanding the Earth’s climate responses, attributing observed changes to specific drivers, projecting future climate conditions, and supporting the development of mitigation policies. Two “Shared Socio-Economic Pathways” (SSPs) [25] were chosen, namely (i) SSP2–4.5 Middle of the Road; and (ii) SSP5–8.5 Fossil-fueled Development—Taking the Highway. These two climate change scenarios (SSP2–4.5 and SSP5–8.5) represent a moderate climate change scenario (meeting the Kyoto goal) and a severe climate change scenario (not meeting the Kyoto goal), respectively.

In this study, climate variables followed the original WorldClim symbology, where variables from BIO1 to BIO11 are temperature-related, and variables from BIO12 to BIO19 are precipitation-related. The EC-Earth3-Veg model was selected as GCM because it explicitly integrates dynamic vegetation and biogeochemical cycles, enabling a more realistic assessment of forest species’ climate adaptation under different climate change scenarios and ensuring consistency among climate forcing, water availability, and ecophysiological responses [24]. The elevation data were obtained from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission 1 Arc-Second Global (SRTM) [26]. The soil data were derived from the ESDBv2 Raster Library in grid cell ≈ 1 km2 [27,28,29]. The soil-related variable used the soil codes (WRBFU) according to the international classification system.

2.3. Species Climate Envelope Models (CEMs)

The Climate Envelope Model was used as a reliable and understandable starting point for analysing species distribution, as it clearly connects the observed presence of species to climate conditions and their possible environmental limits [30]. This study considers the amplitude and limits of a set of environmental variables, topography, and soil type (see Table 1) that determined the distribution of each species (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3 contain the set of selected variables and the limits for species current data occurrences). These species CEM variables thresholds are published in the Portuguese Regional Forest Management Plans of 2005 and were constructed using bibliographic data (defining the ecological limits of each species), therefore containing most of each species’ forest inventory plots (IFN4) (75% for eucalyptus and maritime pine; 95% for the remaining species). Each species CME is defined by a unique combination of environmental variables and corresponding thresholds. Later, Heikkinen et al. (2006) [17] produced the CMEs for eucalyptus and maritime pine with updated sources of ecological data and validated them with the species distribution data, obtaining variable thresholds consistent with those published in the Portuguese Regional Forest Management Plans of 2005. Afterwards, ICNF (2019) [18] also validated maritime pine CME environmental variables selection and corresponding thresholds by Machine Learning, Classification and Regression Trees (CART), and classification with the tree algorithm J48, performed by means of WEKA software (V3.8.4), using 88,455 presence points. This model had a 65% fitting efficiency and used basically the same environmental variables, and its thresholds were quite close to the ones published in the Portuguese Regional Forest Management Plans of 2005. Therefore, the species variables thresholds published in the Portuguese Regional Forest Management Plans of 2005 (Table 1) were considered valid and used to produce the species CEM in this study, except for the maritime pine, for which the thresholds were retrieved from ICNF (2019) [18]. These environmental variables were structured in a GIS (Geographic Information Systems) database, utilizing ArcGIS Pro V3.3 software to generate each variable map. For each species, the environmental variables thresholds were applied to get species variables maps reclassified by the Boolean method (0—Inadequate, 1—Adequate). Then, the species CEMs for the current were obtained by map algebra, an algebraic addition of the binary maps of the environmental variables, resulting in a final map after being reclassified into the following four suitability classes: (0) Unsuitable, (1) Low, (2) Regular, and (3) High; “Unsuitable” means no variable thresholds are verified, “Low” means one variable threshold is observed, “Regular” means two to three variable thresholds are observed, and “High” means all variable thresholds are observed. The additive Boolean method was employed because it allows multiple environmental criteria to be integrated transparently and robustly, reducing the influence of data uncertainty and facilitating the identification of areas that satisfy a greater number of relevant ecological conditions [30].

Table 1.

CEMs—species environmental variables thresholds [16,19,20,31].

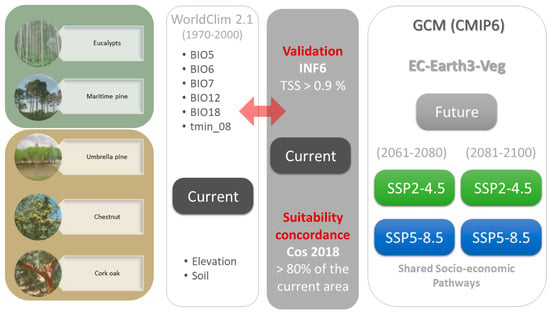

Afterwards, the environmental variables were projected for the future (2070 and 2090) under the two climate change scenarios (SSP2–4.5 and SSP5–8.5) to produce the species CEMs and also for the current conditions. The methodological workflow is synthesized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Methodological workflow—current species and future CEMs for current conditions (2070 and 2090) under two climate change scenarios (SSP2–4.5 and SSP5–8.5).

The current species CEMs were validated using the species national forest inventory data (IFN6) (pure dominant stands) [18]. The LULC official map (COS 2018) [22] was used to compare the current distribution of species (eucalypts, maritime pine, umbrella pine, chestnut, and cork oak) and the impact of climate change scenarios for the future (2070 and 2090).

The validation metrics (accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and TSS) of the CEMs are based on spatial agreement with observed distributions using national forest inventory data from dominant pure stands of INF6 [18] and were performed for the species under study (Table 2).

Table 2.

Validation metrics (accuracy, sensitivity, specificity and TSS).

Finally, a combined CEM (Supplementary Figure S6, which includes data for the combined options content in this study) was obtained for these species to highlight hotspots of excellent suitability for each species, thereby supporting a comprehensive key recommendation for afforestation planning in Portugal, particularly for wood and non-wood production species.

3. Results

3.1. Afforestation Suitability CEM-Based

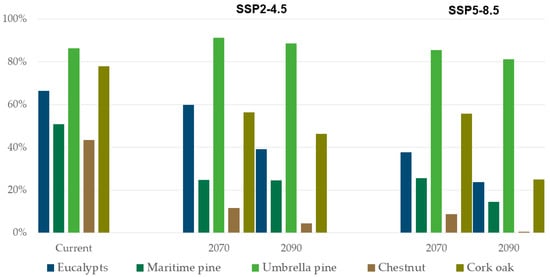

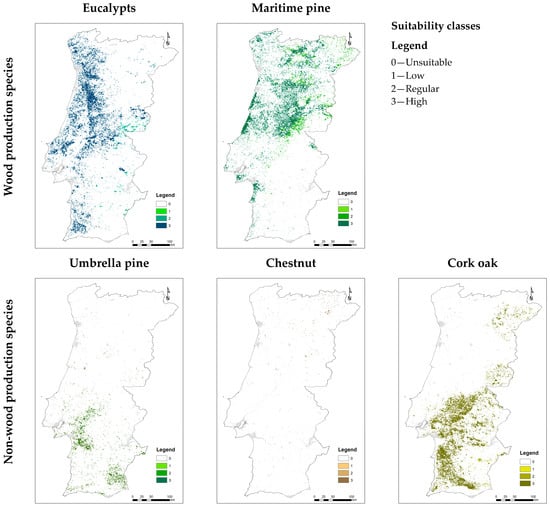

Climate Envelope Models (Figure 3) indicate high current afforestation potential for wood-production species within the highest suitability class (Class 3), with eucalypts occupying approximately 80% of suitable areas and maritime pine about 50%. However, strong contractions are projected under future climate scenarios (Supplementary Figures S1 and S2). By 2090, eucalypt suitability declines to <38% under SSP2–4.5 and ~23% under SSP5–8.5, while maritime pine decreases to <26% and ~15%, respectively. For both species, remaining high-suitability areas become largely confined to a narrow Atlantic coastal strip. Similarly, current CEMs for non-wood production species (Supplementary Figures S3–S5) show high suitability for umbrella pine (~90%), chestnut (~45%), and cork oak (~80%), followed by widespread declines by 2090 under both scenarios. Umbrella pine exhibits a slight increase by 2070 and remains relatively stable under SSP5–8.5, whereas chestnut experiences the most severe reductions, declining to <9% (SSP2–4.5) and ~1% (SSP5–8.5) (Figure 3). Cork oak shows a continuous loss of suitable area throughout the study period.

Figure 3.

High-suitability class areas distribution (%), under current and SSP2–4.5 and SSP5–8.5 conditions, for eucalypts, maritime pine, umbrella pine, chestnut, and cork oak.

3.2. Afforestation Planning

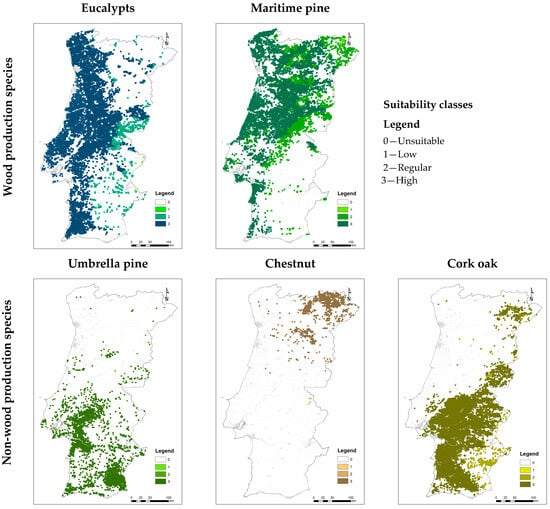

The analysis of the expression of the CEMs current suitability classes regarding the species forest inventory data/occurrences (Figure 4) indicated that 80.6% to 99.6% fall into the highest suitability class (Table 3).

Figure 4.

Current species forest inventory occurrences (IFN6) [18] by CEMs suitability classes for wood production species (eucalypts and maritime pine) and non-wood production species (umbrella pine, chestnut, and cork oak), in gray appears the urban areas, rivers and dams.

Table 3.

Species CEMs current suitability classes expression (%), considering species national forest inventory data/occurrences (IFN6) [18] for wood production species (eucalypts and maritime pine) and non-wood production species (umbrella pine, chestnut, and cork oak).

The analysis of current suitability classes as expression of the CEMs regarding the LULC map COS 2018 (Figure 5) indicated that 72% to 99.8% fall into the highest suitability class (Table 4).

Figure 5.

Species’ current distribution (COS 2018) by CEMs suitability classes for wood production species and non-wood production species, in gray the urban areas, rivers and dams.

Table 4.

Species CEMs current suitability classes expression (%) regarding species’ current distribution (COS 2018) for wood production species (eucalypts and maritime pine) and non-wood production species (umbrella pine, chestnut, and cork oak).

Current species CEMs were validated based on spatial agreement with observed distributions, using National Forest Inventory data (INF6) and the official Portuguese Land Use and Land Cover map (COS 2018). COS 2018 areas for the five species showed agreement values above 80%, while INF6 point data indicated overall agreement exceeding 99%, reflecting concordance with current distributions.

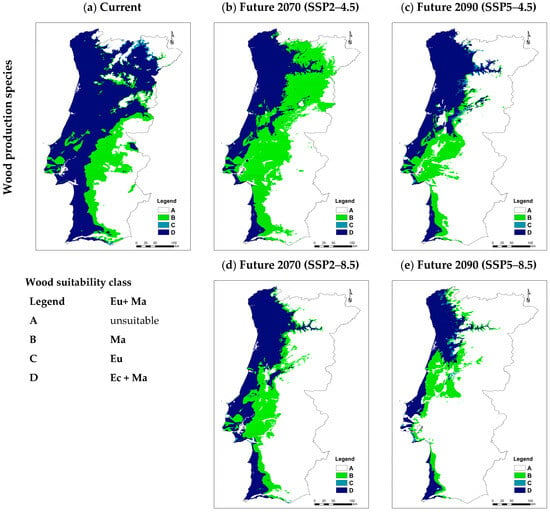

Concerning combinations of wood species, both species are unsuitable in Class A (0, 0). Maritime pine is suitable in Class B (0, 1), and Eucalyptus is suitable in Class C (1, 0). Both species are suitable in Class D (1, 1) (Supplementary Figure S6).

The combined CEMs analysis (Figure 6) of the highest suitability class for the two wood production species (Eu—eucalypts; and Ma—maritime pine) confirmed that the country’s coastal area is very suitable for both species’ afforestation. Thus, future conflicts about afforestation areas with these two species will occur.

Figure 6.

Combined CEMs of the highest suitability class (3—High) for wood production species (Eu—eucalypts; and Ma—maritime pine): (a) current; (b) future 2070 and scenario SSP2–4.5; (c) future 2090 and scenario SSP2–4.5; (d) future 2070 and scenario SSP2–8.5; (e) future 2090 and scenario SSP2–8.5.

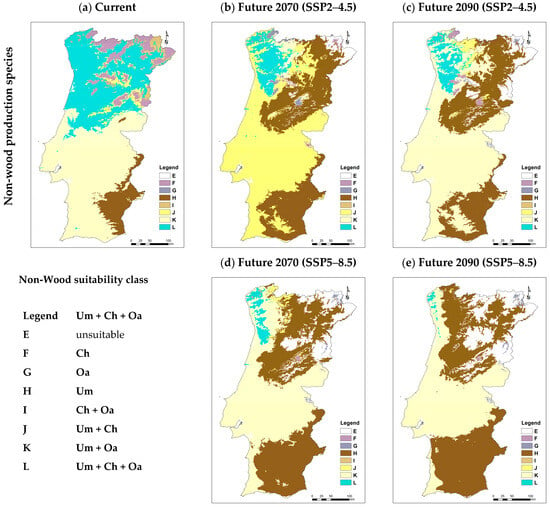

Concerning combinations among the non-wood species, namely umbrella pine (Um), chestnut (Ch), and cork oak (Oa), Class E (0,0,0) proves unsuitable for non-wood species; F (0,0,1) is suitable for chestnut; G (0,1,0) is suitable for cork oak; H (1,0,0) is suitable for umbrella pine; I (0,1,1) has combined chestnut and cork oak suitability; J (1,1,0) is suitable for a combination of umbrella pine and chestnut; K (1,0,1) is suitable for the combination of umbrella pine and cork oak; and L (1,1,1) is suitable for all non-wood species (Supplementary Figure S6).

CEMs analysis (Figure 7) for the highest suitability class of the three non-wood production species, namely umbrella pine (Um), chestnut (Ch), and cork oak (Oa), reveals that umbrella pine will likely remain the only species capable of maintaining suitable conditions in inland Portugal under future climates. In contrast, coastal regions are projected to retain high suitability, particularly for umbrella pine–chestnut mixtures in the north and umbrella pine–cork oak mixtures in south-central areas. These findings support the promotion of mixed afforestation strategies, such as combining umbrella pine with chestnut or cork oak, to increase forest resilience to climate change.

Figure 7.

Combined CEMs of the highest suitability class (3—High) for non-wood production species (Um—umbrella pine, Ch—chestnut, and Oa—cork oak): (a) current; (b) future 2070 and scenario SSP2–4.5; (c) future 2090 and scenario SSP2–4.5; (d) future 2070 and scenario SSP5–8.5; (e) future 2090 and scenario SSP5–8.5.

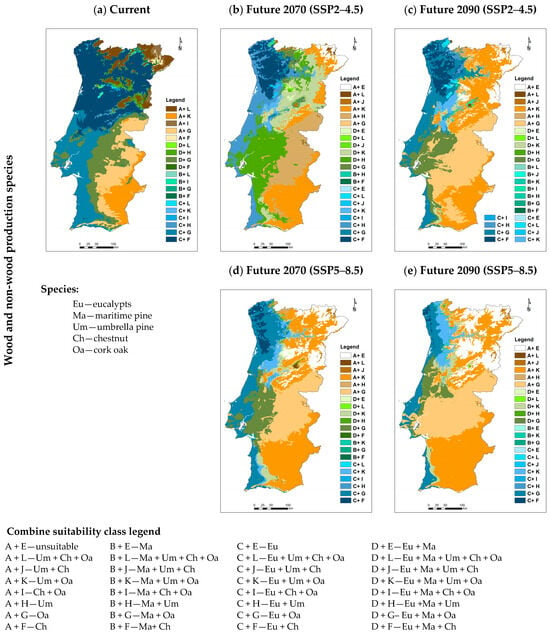

The combined scheme for all species integrates the two previous explained phases: each combined code (Ex. A + L, B + L, C + L or D + L) represents the co-occurrence of one or more of the five species, with classes reflecting the unsuitability of the study species (A+ E), single-species presence (A + H; A + G; A + F; B + E and C + E), or multiple-species co-occurrence (e.g., A + L—umbrella pine, chestnut, and cork oak; B + L—maritime pine, umbrella pine, chestnut, and cork oak; C + L—eucalyptus, umbrella pine, chestnut, and cork oak; and D + L—all species in the study (Supplementary Figure S6).

Finally, the analysis of the combined CEMs (Figure 8) for the highest suitability class of the wood production species and the non-wood production species reveals that coastal areas of the country are likely to experience afforestation conflicts between highly intensive forestry and multifunctional or combined-objective forestry. Notably, due to putative sources of uncertainty arising from threshold rigidity, scenario uncertainty (SSP2–4.5 vs. SSP5–8.5), and the use of a single GCM (EC-Earth3-Veg), the results should be interpreted as scenario-consistent tendencies rather than precise forecasts.

Figure 8.

Combined CEMs of the highest suitability class (3—High) for both wood and non-wood production (Eu—eucalypts; Ma—maritime pine; Um—umbrella pine; Ch—chestnut; Oa—cork oak): (a) current; (b) future 2070 and scenario SSP2–4.5; (c) future 2090 and scenario SSP2–4.5; (d) future 2070 and scenario SSP5–8.5; and (e) future 2090 and scenario SSP5–8.5.

4. Discussion

In this study, Climate Envelope Models (CEMs) were developed for five Portuguese forest species, two wood-production species (eucalypts and maritime pine, Figure 6) and three non-wood production species (umbrella pine, chestnut, and cork oak, Figure 7), for current conditions and future periods (2070 and 2090) under two climate change scenarios (SSP2–4.5 and SSP5–8.5). Under current climate conditions, Portugal shows high afforestation suitability for all species, particularly chestnut, maritime pine, eucalypts, cork oak, and umbrella pine (Figure 3).

Observed species distributions, based on National Forest Inventory data (IFN6, Figure 3) and the official Land Use and Land Cover map (COS 2018, Figure 4), largely coincide with high suitability classes, ranging from 80.6% to 99.6%. Similar patterns were observed when compared with the EPIC WebGIS Portugal maps [32] (Supplementary Figure S7).

Climate change is expected to intensify droughts, heatwaves, and wildfires, with strong impacts on plant communities. Recent evidence shows a clear increase in wildfire severity in Portugal, leading to slower post-fire recovery and reduced ecosystem resistance and resilience, thereby increasing the risk of long-term ecological degradation [33]. Because temperature and precipitation are primary controls of plant growth, survival, and distribution, these changes are likely to generate substantial ecological and economic consequences [34,35]. Mediterranean regions are projected to experience particularly strong pressures, with warming and drought frequency exceeding global averages [36,37].

Seasonal climatic constraints further limit productivity, as low temperatures restrict growth during winter and early spring, while reduced precipitation during warmer periods intensifies water stress. Species responses to these stressors depend on genetic adaptation and phenotypic plasticity, which vary widely and govern the capacity to persist under altered climatic regimes [34,35]. Vulnerability is greatest during juvenile and reproductive stages, when root systems are poorly developed, or reproductive success depends on favorable conditions, whereas adult trees generally exhibit greater tolerance due to deeper roots and stored reserves. Climate change will also alter biotic pressures by affecting pest and pathogen dynamics and may increase plant susceptibility to invasion. Finally, abiotic disturbances such as fire are closely linked to climate, particularly precipitation seasonality, which modulates fuel availability and fire extent [35].

A new plantation paradigm is required to address the challenges posed by future climate warming, integrating projections of species’ future suitability with afforestation alternatives that reduce associated risks. Strategies based on ecologically friendly species mosaics and mixed stands can enhance biodiversity, increase resilience, better mimic natural forest dynamics, and support the success of the species plantation. As an example, both wood-production species (eucalypt and maritime pine) suitability areas will shrink in the future to a coastal strip; thus, their long-term production might be compromised, which could prevent forest owners from investing and make forest management unattractive, which will further trigger wildfire recurrence and severity since those species are known to be fire-prone. Broadening plantations with intermixed adequate species could overcome the referred problems (Figure 6). Moreover, establishing umbrella pine plantations followed by thinning and the introduction of cork oak in the understory can mimic natural succession, enhancing plantation success in very dry areas in the south of the country through the high drought tolerance of umbrella pine and its facilitation of cork oak establishment; additionally, a source of multiple incomes can be obtained with those non-wood species (Figure 7). These findings highlight the importance of adaptive silvicultural practices, including density management, to support forest investment and regeneration under future climate scenarios.

Indeed, forest sustainability is closely linked to regeneration success, which is particularly critical in systems reliant on natural regeneration, such as maritime pine and cork oak stands [18,38]. In maritime pine, regeneration is influenced by climate and disturbance across all phases (seeding, germination, and seedling establishment), with failure becoming more likely under drier conditions [34]. Although fire recurrence may not directly affect seed viability or germination, repeated or severe fires can impair root development through increased water stress and can damage the soil seed bank [39]. Forest management, therefore, plays a key role in sustaining regeneration processes [34]. In Portugal, the lack of natural regeneration in approximately 59% of cork oak stands raises serious sustainability concerns, which may be further exacerbated by climate change. Cork oak regeneration has been shown to benefit from higher stand density, as increased canopy cover can mitigate extreme climatic conditions and enhance seedling survival during drought periods, despite potential competition for water [38].

The combined Climate Envelope Models (CEMs) for the highest suitability class of both wood-production species (eucalypts and maritime pine) and non-wood production species (umbrella pine, chestnut, and cork oak) were used to identify key drivers and derive recommendations for afforestation planning under future climate change scenarios (Figure 6 and Figure 7). Species-specific traits and management regimes are central to these recommendations. Eucalypts are exotic, fast-growing, light-demanding species, typically intensively managed under short coppice rotations (10–12 years) for high wood yield, but they are associated with adverse environmental impacts, including soil compaction, nutrient depletion, allelopathy, erosion, and increased agrochemical inputs [40,41,42,43]. In contrast, maritime pine and umbrella pine are native, light-demanding species managed under medium–long (40–45 years) and long (80–100 years) rotations, respectively, with umbrella pine primarily valued for non-wood products and protective functions [44]. Cork oak and chestnut are native, shade-tolerant, slow-growing species managed under very long rotations (100–110 years) for non-wood production [45]. Moreover, for equivalent management intensities, maritime pine production systems generally exert lower environmental impacts than eucalypt plantations across multiple impact categories, including resource depletion, climate forcing, acidification, and eutrophication [46].

This approach allows the identification of the main climatic factors that constrain the potential distribution of the species studied. For chestnuts, the most relevant limiting factor is the minimum temperature in August (tmin_08). In the case of cork oak and maritime pine, limitations to the potential ecological envelope are mainly related to the maximum temperature of the warmest month (BIO5). For eucalyptus, the potential envelope is constrained by the combined effect of the annual temperature range (BIO7) and annual precipitation (BIO12). Finally, for stone pine, the expansion of the potential ecological envelope is primarily associated with the minimum temperature of the coldest month (BIO6) (Figure 8). Thus, in the 2090 scenarios, the prevailing species will be the umbrella pine and the cork oak; they may dominate in mixed or pure stands. In the least severe SSP2–2.45, the dominant combinations will keep stone pine and cork oak but contain a transition area with combined stands of (1) eucalyptus, maritime pine, and umbrella pine; (2) eucalyptus, maritime pine, umbrella pine, and cork oak; and (3) umbrella pine and cork oak (Figure 8). Accordingly, afforestation in areas highly suitable for eucalypts and/or maritime pine should be planned at the landscape scale, favoring spatially structured mosaics that combine intensively managed wood-production stands with pure or mixed non-wood production patches (e.g., Ma + Oa; Ma + Ch; Um + Oa). Such configurations can promote cork oak and chestnut natural regeneration, enhance biodiversity, and increase landscape resilience, thereby reducing vulnerability to biotic and abiotic risks under future climate change.

Although forest landscapes are inherently multifunctional, the degree of multifunctionality can vary, as not all spatial units possess the same capacity to provide all desired functions. From a spatial perspective, three types of multifunctionality can be distinguished: (i) a mosaic of distinct spatial units, each performing a single function; (ii) the coexistence of multiple functions within the same spatial unit but separated in time; and (iii) the full integration of multiple functions within the same spatial unit and time [47,48]. So, forest landscape planning must entail the strategic organization of different ecological patches within a landscape to maximize the functions of forest ecosystems and enhance ecosystem services [49,50]. By protecting key areas, enhancing connectivity between forest patches, and supplementing woodland areas, forest management can optimize the provision of ecosystem services [50,51]. Integrating ecosystem services into forest management practices not only allows for the sustainable use of forest resources but also supports the optimal allocation of these resources for long-term sustainability [52,53]. Both wood and non-wood species are fundamental to maintaining the functional integrity of forest ecosystems; at the same time, timber remains among the key products derived from these systems [54] and, additionally, provides ecosystem services from carbon storage to biodiversity conservation, climate change mitigation, and water and soil protection [55].

Furthermore, Portuguese forest stands are unevenly prone to fire, with mature forests of broadleaved deciduous and mixed forests having a lower fire hazard compared to pure pine forests, eucalyptus plantations, or mixed pine and eucalyptus stands [56,57,58,59]. Therefore, priority should be given to the expansion of deciduous broadleaved and mixed forests instead of pine or exotic species plantations, especially within fire-prone areas. Also, afforestation strategies should promote the development of spatially dispersed forest patches smaller than 30 ha to increase landscape resilience and minimize wildfire propagation [58,59]. In fact, the fragmentation of a fire-prone landscape with patches in different succession stages, the introduction of narrow corridors between wooded patches, and the promotion of convoluted perimeters are effective measures to reduce the potential fire size and fire severity [59]. Indeed, in Portugal, factors such as small property size, the predominance of private forest ownership, land abandonment, and the lack of active forest management, combined with the spread of unmanaged forests (particularly pine) and shrubland regeneration (mainly Cistus spp. and Cytisus spp.), create conditions that exacerbate the occurrence of severe wildfires, further intensified by the effects of climate change [60].

Finally, afforestation may also contribute to the rehabilitation of degraded lands and mitigate the effects of desertification. As is known, afforestation success relies firstly on the right selection of species (CEMs’ best-suitability areas) combined with appropriate procedures for species establishment and management. Ultimately, it will depend on the correct choices regarding rootstock and size (age) of seedlings, the time and method of planting, and the protection of seedlings from competition and predators (e.g., by using either individual tree protection or individual tree protection and fences combined) [61].

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, afforestation policies must be explicitly aligned with climate change projections and prioritize species and management systems that are expected to remain suitable under future environmental conditions. Policy frameworks should promote the adoption of preventive silvicultural measures, including fuel management, species diversification, and ecosystem-based planning, as core instruments to enhance forest resilience and reduce climate-related risks. The suitability of the species will change because annual precipitation is the main limiting factor for the species under study. As a result, suitability will fluctuate depending on the amount of rainfall projected in each scenario. In both 2090 scenarios, umbrella pine and cork oak emerge as the most suitable species, and they may dominate in either mixed or pure stands. In the less severe SSP2–2.4 scenario, these two species remain dominant; however, a transitional zone appears, containing mixed stands composed of (1) eucalyptus, maritime pine, and umbrella pine and (2) eucalyptus, maritime pine, umbrella pine, and cork oak. Afforestation planning should move toward multifunctional landscape designs, favoring mosaics of intensively managed wood-production species interspersed with non-wood production species, thereby reducing vulnerability to wildfires, drought, and biotic disturbances. Herein, the results clearly support the potential for mixed and mosaic plantations in the future, scattered across the country. Such an approach enables the simultaneous delivery of ecological, economic, and social objectives; supports long-term forest sustainability; and ensures diversified and temporally distributed income streams for landowners. Integrating these principles into national afforestation and forest management policies will be essential to safeguard Portugal’s forest landscapes under ongoing climate change. Future studies should be focused on methodology comparison, such as the CEM limitations (such as niche truncation and non-equilibrium distributions, among others), the lack of soil moisture dynamics, and demographic processes. Additionally, we advise the start of site-specific studies about mixed stands and mosaic species combinations with a robust experimental design.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/f17010139/s1. References [18,21,32,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86] are cited in Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.A. and N.R.; data curation, C.A. and N.R.; methodology, C.A., N.R., A.M.A., P.F. and M.M.R.; formal analysis and writing—original draft preparation, C.A. and N.R.; writing—review and editing, C.A. and M.M.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT), through the projects Research Centre for Natural Resources, Environment and Society-CERNAS, UID/681/2025 (DOI https://doi.org/10.54499/UID/00681/2025), the Forest Research Centre, UID/00239/2025 (DOI: 10.54499/UID/00239/2025) and UID/PRR/00239/2025 (DOI: 10.54499/UID/PRR/00239/2025), and the Associate Laboratory TERRA, LA/P/0092/2020 (DOI: 10.54499/LA/P/0092/2020). MED—Mediterranean Institute for Agriculture, Environment and Development (https://doi.org/10.54499/UID/05183/2025). Associate Laboratory CHANGE—Global Change and Sustainability Institute (https://doi.org/10.54499/LA/P/0121/2020).

Data Availability Statement

The data files used in the study can be requested by email from the corresponding author but are also openly available at the following link: https://sig.icnf.pt/portal/home/item.html?id=dc60bcef20b844b88c8a0638d0fe943b (accessed on 15 January 2026).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Doelman, J.C.; Stehfest, E.; Vuuren, D.P.v.; Tabeau, A.; Hof, A.F.; Braakhekke, M.C.; Gernaat, D.; Berg, M.v.d.; Zeist, W.J.v.; Daioglou, V.; et al. Afforestation for Climate Change Mitigation: Potentials, Risks and Trade-offs. Glob. Change Biol. 2019, 26, 1576–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco-Velázquez, F.J.; Pino-Mejías, R.; Anaya-Romero, M. Evaluating the Provision of Ecosystem Services to Support Phytoremediation Measures for Countering Soil Contamination. A Case-study of the Guadiamar Green Corridor (SW Spain). Land Degrad. Dev. 2020, 31, 2914–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnus, G.K.; Celanowicz, E.; Voicu, M.; Hafer, M.; Metsaranta, J.M.; Dyk, A.; Kurz, W.A. Growing Our Future: Assessing the Outcome of Afforestation Programs in Ontario, Canada. For. Chron. 2021, 97, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooney, P.; Lee, H.; Sobolowski, S. Impact of Quasi-Idealized Future Land Cover Scenarios at High Latitudes in Complex Terrain. Earth’s Future 2021, 9, e2020EF001838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breil, M.; Krawczk, F.; Pinto, J.G. The Response of the Regional Longwave Radiation Balance and Climate System in Europe to an Idealized Afforestation Experiment. Earth Syst. Dyn. 2022, 14, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarnetske, P.L.; Edwards, T.C.; Moisen, G.G. Habitat Classification Modeling with Incomplete Data: Pushing the Habitat Envelope. Ecol. Appl. 2007, 17, 1714–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeschke, J.M.; Strayer, D.L. Usefulness of Bioclimatic Models for Studying Climate Change and Invasive Species. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1134, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedia, J.; Herrera, S.; Gutiérrez, J.M. Dangers of Using Global Bioclimatic Datasets for Ecological Niche Modeling. Limitations for Future Climate Projections. Glob. Planet. Change 2013, 107, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamann, A.; Wang, T. Potential Effects of Climate Change on Ecosystem and Tree Species Distribution in British Columbia. Ecology 2006, 87, 2773–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihai, G.; Alexandru, A.-M.; Niţă, I.-A.; Bîrsan, M.-V. Climate Change in the Provenance Regions of Romania Over the Last 70 Years: Implications for Forest Management. Forests 2022, 13, 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakkenes, M.; Alkemade, R.; Ihle, F.; Leemans, R.; Latour, J.B. Assessing Effects of Forecasted Climate Change on the Diversity and Distribution of European Higher Plants for 2050. Glob. Change Biol. 2002, 8, 390–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, R.G.; Dawson, T.P. Predicting the Impacts of Climate Change on the Distribution of Species: Are Bioclimate Envelope Models Useful? Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2003, 12, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoo, L.P.; Williams, S.E.; Hero, J. Potential Decoupling of Trends in Distribution Area and Population Size of Species with Climate Change. Glob. Change Biol. 2005, 11, 1469–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarancón, A.A.; Fulé, P.Z.; Shive, K.L.; Sieg, C.H.; Meador, A.J.S.; Strom, B.A. Simulating Post-wildfire Forest Trajectories under Alternative Climate and Management Scenarios. Ecol. Appl. 2014, 24, 1626–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pecchi, M.; Marchi, M.; Burton, V.; Giannetti, F.; Moriondo, M.; Bernetti, I.; Bindi, M.; Chirici, G. Species Distribution Modelling to Support Forest Management. A Literature Review. Ecol. Modell. 2019, 411, 108817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegria, C.; Almeida, A.M.; Roque, N.; Fernandez, P.; Ribeiro, M.M. Species Distribution Modelling under Climate Change Scenarios for Maritime Pine (Pinus pinaster Aiton) in Portugal. Forests 2023, 14, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikkinen, R.K.; Luoto, M.; Araújo, M.B.; Virkkala, R.; Thuiller, W.; Sykes, M.T. Methods and Uncertainties in Bioclimatic Envelope Modelling under Climate Change. Prog. Phys. Geogr. Earth Environ. 2006, 30, 751–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICNF. 6o Inventário Florestal Nacional—IFN6. 2015. Relatório Final; Instituto da Conservação da Natureza e das Florestas: Lisboa, Portugal, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Alegria, C.; Roque, N.; Albuquerque, T.; Gerassis, S.; Fernandez, P.; Ribeiro, M.M. Species Ecological Envelopes under Climate Change Scenarios: A Case Study for the Main Two Wood-production Forest Species in Portugal. Forests 2020, 11, 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegria, C.; Roque, N.; Albuquerque, T.; Fernandez, P.; Ribeiro, M.M. Modelling Maritime Pine (Pinus pinaster Aiton) Spatial Distribution and Productivity in Portugal: Tools for Forest Management. Forests 2021, 12, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.; Gonçalves, A.B.; Costa, R.L.; Gomes, A.A. GIS-Based Assessment of the Chestnut Expansion Potential: A Case-Study on the Marvão Productive Area, Portugal. Agriculture 2021, 11, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DGT. Carta de Uso e Ocupação do Solo. Registo Nacional de Dados Geográficos. SNIG. Direção-Geral do Território. Lisboa. Portugal. Available online: https://snig.dgterritorio.gov.pt/rndg/srv/por/catalog.search#/search?resultType=details&sortBy=referenceDateOrd&anysnig=COS&fast=index&from=1&to=20 (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- Fick, S.E.; Hijmans, R.J. Worldclim 2: New 1-km Spatial Resolution Climate Surfaces for Global Land Areas. Int. J. Climatol. 2017, 36, 4302–4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döscher, R.; Acosta, M.; Alessandri, A.; Anthoni, P.; Arsouze, T.; Bergman, T.; Bernardello, R.; Boussetta, S.; Caron, L.P.; Carver, G.; et al. The EC-Earth3 Earth System Model for the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project 6. Geosci. Model Dev. 2022, 15, 2973–3020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riahi, K.; van Vuuren, D.P.; Kriegler, E.; Edmonds, J.; O’Neill, B.C.; Fujimori, S.; Bauer, N.; Calvin, K.; Dellink, R.; Fricko, O.; et al. The Shared Socioeconomic Pathways and Their Energy, Land Use, and Greenhouse Gas Emissions Implications: An Overview. Glob. Environ. Change 2017, 42, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- STRM Shuttle Radar Topography Mission 1 Arc-Second Global: SRTM1N22W016V3, U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). Available online: https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/ (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- Panagos, P. The European Soil Database. GEO Connex. 2006, 5, 32–33. [Google Scholar]

- IUSS Working Group WRB. World Reference Base for Soil Resources 2014, International Soil Classification System for Naming Soils and Creating Legends for Soil Maps. Update 2015; World Soil; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Van Liedekerke, M.; Jones, A.; Panagos, P. ESDBv2 Raster Library—A Set of Rasters Derived from the European Soil Data-Base Distribution v2.0 (CD-ROM, EUR 19945 EN). European Commission and the European Soil Bureau Network. Available online: https://esdac.jrc.ec.europa.eu/content/european-soil-database-v2-raster-library-1kmx1km (accessed on 29 July 2018).

- Araújo, M.B.; Peterson, A.T. Uses and Misuses of Bioclimatic Envelope Modeling. Ecology 2012, 93, 1527–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Direção Geral dos Recursos Florestais. DGRF Plano Regional de Ordenamento Florestal do Pinhal Interior Sul; Documento Estratégico; Direção Geral dos Recursos Florestais: Lisboa, Portugal, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mesquita, S.; Capelo, J. Epic WebGis Portugal Ecological Planning, Investigation and Cartography. Available online: http://epic-webgis-portugal.isa.utl.pt/ (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Gonçalves, J.; Marcos, B.; Honrado, J. Remotely Sensed Time Series Reveal Varying Levels of Association Between Burned Area and Severity Across Regions in Mainland Portugal. In Advances in Forest Fire Research; Viegas, D.X., Ribeiro, L.M., Eds.; Coimbra University Press: Coimbra, Portugal, 2022; pp. 343–352. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, S.; Cerveira, A.; Soares, P.; Fonseca, T. Natural Regeneration of Maritime Pine: A Review of the Influencing Factors and Proposals for Management. Forests 2022, 13, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, J.S.; Correia, A.V.; Correia, C.V.; Ferreira, M.T.; Onofre, N.; Freitas, H.; Godinho, F. Florestas e Biodiversidade. In Alterações Climáticas em Portugal. Cenários, Impactos e Medidas de Adaptação (Projecto SIAM II); Santos, F., Miranda, P.M., Eds.; Gradiva: Lisboa, Portugal, 2006; pp. 301–344. [Google Scholar]

- Lionello, P.; Scarascia, L. The Relation Between Climate Change in the Mediterranean Region and Global Warming. Reg. Environ. Change 2018, 18, 1481–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barredo, J.I.; Caudullo, G.; Dosio, A. Mediterranean Habitat Loss under Future Climate Conditions: Assessing Impacts on the Natura 2000 Protected Area Network. Appl. Geogr. 2016, 75, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, S.; Cerveira, A.; Soares, P.; Ribeiro, N.A.; Camilo-Alves, C.; Fonseca, T.F. Natural Regeneration of Cork Oak Forests under Climate Change: A Case Study in Portugal. Front. For. Glob. Change 2024, 7, 1332708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, S.; Gaspar, M.J.; Lima-Brito, J.; Fonseca, T.; Soares, P.; Cerveira, A.; Fernandes, P.M.; Louzada, J.; Carvalho, A. Impact of Fire Recurrence and Induced Water Stress on Seed Germination and Root Mitotic Cell Cycle of Pinus pinaster Aiton. Forests 2023, 14, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, P.; Tome, M.; Pereira, J.S. A Produtividade do Eucaliptal. In O Eucaliptal em Portugal: Impactes Ambientais e Investigacao Cientifica; Alves, A.M., Pereira, J.S., Silva, J.M.N., Eds.; ISA Press: Lisboa, Portugal, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Águas, A.; Ferreira, A.; Maia, P.; Fernandes, P.M.; Roxo, L.; Keizer, J.; Silva, J.S.; Rego, F.C.; Moreira, F. Natural Establishment of Eucalyptus globulus Labill. in Burnt Stands in Portugal. For. Ecol. Manag. 2014, 323, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, J. Ecological Aspects of Eucalyptus Plantations; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1993; Volume I, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Alegria, C.; Pedro, N.; do Carmo Horta, M.; Roque, N.; Fernandez, P. Ecological Envelope Maps and Stand Production of Eucalyptus Plantations and Naturally Regenerated Maritime Pine Stands in the Central Inland of Portugal. For. Ecol. Manag. 2019, 432, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A. Boas Práticas Florestais para o Pinheiro-bravo. Manual; Pinus, C., Ed.; Centro PINUS: Porto, Portugal, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Louro, G.; Marques, H.; Salinas, F. Elementos de Apoio à Elaboração de Projetos Florestais, 2nd ed.; Direção-Geral das Florestas (DGF): Lisboa, Portugal, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, A.C.; Arroja, L. Environmental Impacts of Eucalypt and Maritime Pine Wood Production in Portugal. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 37, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blust, G.; van Olmen, M. Monitoring Multifunctional Terrestrial Landscapes: Some Comments. In Multifunctional Landscapes: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Landscape Research and Management; Brandt, J., Tress, B., Tress, G., Eds.; Centre for Landscape Research: Roskilde, Denmark, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt, J.; Vejre, H. (Eds.) Multifunctional Landscapes—Motives, Concepts and Perspectives. In Multifunctional Landscapes (Vol. 1); WIT Press: Ashurst Lodge, Southampton, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Li, J. The Study of the Ecological Problems of Eucalyptus Plantation and Sustainable Development in Maoming Xiaoliang. J. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 3, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liang, S.; Yang, L. A Review of Regional and Global Gridded Forest Biomass Datasets. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Fei, X.; Liu, F.; Chen, J.; You, X.; Huang, S.; Wang, M.; Dong, J. Advances in Forest Management Research in the Context of Carbon Neutrality: A Bibliometric Analysis. Forests 2022, 13, 1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Dai, L. Estimating and Mapping Forest Biomass in Northeast China using Joint Forest Resources Inventory and Remote Sensing Data. J. For. Res. 2018, 29, 797–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Wang, L.; Yang, L.; Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, L. Predicting the Supply–Demand of Ecosystem Services in the Yangtze River Middle Reaches Urban Agglomeration. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 2022, 46, 530–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appiagyei, B.D.; Belhoucine-Guezouguli, L.; Bessah, E.; Morsli, B. The Changing Land Use and Land Cover in the Mediterranean Basin: Implications on Forest Ecosystem Services. Folia Oecol. 2023, 50, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganglo, I.T. Structural Characteristics of Niaouli Forests, Biodiversity, and Ethnobotanical Importance of the Valuable Species. J. Ecol. Nat. Resour. 2023, 7, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, P.M. Examining Fuel Treatment Longevity through Experimental and Simulated Surface Fire Behaviour: A Maritime Pine Case Study. Can. J. For. Res. Can. Rech. For. 2009, 39, 2529–2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.; Moreira, F.; Vaz, P.; Catry, F.; Ferreira, P. Assessing the Relative Fire Proneness of Different Forest Types in Portugal. Plant Biosyst. 2009, 143, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, P.M.; Luz, A.; Loureiro, C. Changes in Wildfire Severity from Maritime Pine Woodland to Contiguous Forest Types in the Mountains of Northwestern Portugal. For. Ecol. Manag. 2010, 260, 883–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, F.; Viedma, O.; Arianoutsou, M.; Curt, T.; Koutsias, N.; Rigolot, E.; Barbati, A.; Corona, P.; Vaz, P.; Xanthopoulos, G.; et al. Landscape—Wildfire Interactions in Southern Europe: Implications for Landscape Management. J. Environ. Manag. 2011, 92, 2389–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acácio, V.; Dias, F.S.; Catry, F.X.; Rocha, M.; Moreira, F. Landscape Dynamics in Mediterranean Oak Forests under Global Change: Understanding the Role of Anthropogenic and Environmental Drivers Across Forest Types. Glob. Change Biol. 2016, 23, 1199–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaz, C.; Alegria, C.; Monteiro, J.M.; Teixeira, M.C. Land Cover Change and Afforestation of Marginal and Abandoned Agricultural Land: A 10-year Analysis in a Mediterranean Region. For. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 308, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naves, P.; Bragança, H.; Nóbrega, F.; Valente, C. Ambrosiodmus rubricollis (Eichhoff) (Coleoptera; Curculionidae; Scolytinae) Associated with Young Tasmanian Blue Gum Trees. J. Appl. Entomol. 2019, 143, 1200–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johny, A. Sustainability Assessment of Highly Fluorescent Carbon Dots Derived from Eucalyptus Leaves. Environments 2024, 11, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, M. de C.S.; Paula, T. d. A.; Moreira, B.C.; Carolino, M.; Cruz, C.; Bazzolli, D.M.S.; Silva, C.C.; Kasuya, M.C.M. Nitrogen-Fixing Bacteria in Eucalyptus Globulus Plantations. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e111313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, V.; Elosegi, A.; Gulis, V.; Pozo, J.; Graça, M.A.S. Eucalyptus Plantations Affect Fungal Communities Associated With Leaf-Litter Decomposition in Iberian Streams. Arch. Für Hydrobiol. 2006, 166, 467–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuer, C.A.; Rodrigues, R.d.A.R.; Balieiro, F.d.C.; Jesus, J.B.D.; Silva, E.P.; Alves, B.J.R.; Rachid, C.T.C.C. Short-Term Effect of Eucalyptus Plantations on Soil Microbial Communities and Soil-Atmosphere Methane and Nitrous Oxide Exchange. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 15133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pestana, L.F.d.A.; Martello, F.; Fonseca, R.C.B. Richness and Composition of Terrestrial Mammals Vary in Eucalyptus Plantations Due to Stand Age. Austral Ecol. 2023, 48, 743–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Gonzalo, J.; Pukkala, T.; Borges, J.G. Integrating Fire Risk in Stand Management Scheduling. An Application to Maritime Pine Stands in Portugal. Ann. Oper. Res. 2011, 219, 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasques, A.; Maia, P.; Pedro, M.; Santos, C.; Vallejo, V.R.; Keizer, J.J. Germination in Five Shrub Species of Maritime Pine Understory—Does Seed Provenance Matter? Ann. For. Sci. 2012, 69, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devy-Vareta, N.L. A Floresta No Espaço e No Tempo Em Portugal. A Arborização Da Serra Da Cabreira (1919–1975). Ph.D. Thesis, Faculdade de Letras, Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, M.M.; Plomion, C.; Petit, R.; Vendramin, G.G.; Szmidt, A.E. Variation in Chloroplast Single-sequence Repeats in Portuguese Maritime Pine (Pinus pinaster Ait.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 2001, 102, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enes, T.; Lousada, J.; Aranha, J.; Cerveira, A.; Alegria, C.; Fonseca, T. Size-density Trajectory in Regenerated Maritime Pine Stands after Fire. Forests 2019, 10, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, M.; Lobo, P.; Sousa, H.; Carrasquinho, I.; Correia, I.; Aguiar, A. Estudos de Base para a Delimitação de Regiões de Proveniência de Pinheiro-bravo. Silva Lusit. 2001, 9, 35–46. [Google Scholar]

- Proença, D.N.; Francisco, R.; Kublik, S.; Schöler, A.; Vestergaard, G.; Schloter, M.; Morais, P. V The Microbiome of Endophytic, Wood Colonizing Bacteria from Pine Trees as Affected by Pine Wilt Disease. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, J.M.; Rodrigues, G.C.; Tomé, M. Climate Change Impacts on Pinus Pinea L. Silvicultural System for Cone Production and Ways to Contour Those Impacts: A Review Complemented with Data from Permanent Plots. Forests 2019, 10, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, J.; Nunes, L.; Rego, F.; Lopes, D. Growth, Soil Properties and Foliage Chemical Analysis Comparison. For. Syst. 2011, 20, 496–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seijo, F.; Millington, J.D.A.; Gray, R.; Sanz, V.; Lozano, J.; García-Serrano, F.; Sangüesa-Barreda, G.; Camarero, J.J. Forgetting Fire: Traditional Fire Knowledge in Two Chestnut Forest Ecosystems of the Iberian Peninsula and its Implications for European Fire Management Policy. Land Use Policy 2015, 47, 130–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seijo, F.; Millington, J.D.; Gray, R.W.; Hernández, L.; Sangüesa-Barreda, G.; Camarero, J.J. Divergent Fire Regimes in Two Contrasting Mediterranean Chestnut Forest Landscapes. Hum. Ecol. 2016, 45, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, A.; Marques, G.; Borges, O.; Portela, E.; Lousada, J.; Raimundo, F.; Madeira, M. Management of Chestnut Plantations for a Multifunctional Land Use Under Mediterranean Conditions: Effects on Productivity and Sustainability. Agrofor. Syst. 2010, 81, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menéndez-Miguélez, M.; Álvarez-Álvarez, P.; Pardos, M.; Madrigal, G.; Ruíz-Peinado, R.; Senespleda, E.L.; Rı́o, M.d.; Calama, R. Development of Tools to Estimate the Contribution of Young Sweet Chestnut Plantations to Climate-Change Mitigation. For. Ecol. Manag. 2023, 530, 120761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feudis, M.D.; Falsone, G.; Vianello, G.; Antisari, L. V The Conversion of Abandoned Chestnut Forests to Managed Ones Does Not Affect the Soil Chemical Properties and Improves the Soil Microbial Biomass Activity. Forests 2020, 11, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.; Pereira, H.; Madeira, M. Landscape Dynamics in Endangered Cork Oak Woodlands in Southwestern Portugal (1958–2005). Agrofor. Syst. 2009, 77, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, C.S.; Alves, A.A.M. Ecological Fire Influences on Quercus Suber Forest Ecosystems. Ecol. Mediterr. 1987, 13, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, T.; Gonçalves, E.; Patrício, M. d. S.; Cota, T.; Almeida, M.H. Seed Origin Drives Differences in Survival and Growth Traits of Cork Oak (Quercus suber L.) Populations. For. Ecol. Manag. 2019, 448, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.; Madeira, M.; Lima, J.S. Is Cork Oak (Quercus suber L.) Woodland Loss Driven by Eucalyptus Plantation? A Case-Study in Southwestern Portugal. Iforest—Biogeosciences For. 2014, 7, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes-Fernandes, M.; Martínez-Fernández, E.; Alves, R.; Boa-Nova, D.; Branquinho, C.; Bugalho, M.N.; Campos-Mardones, F.; Coca-Pérez, A.; Frazão-Moreira, A.; Marques, M.; et al. Cork oak woodlands and decline: A social-ecological review and future transdisciplinary approaches. Agrofor. Syst. 2024, 98, 1927–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.