Abstract

Green perception underlies pro-greenspace behavior, but external stimuli and behavior are not always aligned. Understanding how residents’ perceived external green stimuli influence pro-greenspace behavior, and how the “good citizen” image (face) shapes this relationship, is essential. The study aims to deepen the understanding of the complex mechanisms driving urban residents’ pro-greenspace behavior by constructing an extended Stimulus-Organism-Response theoretical framework (C-SOR) that includes contextual factors. Using data from a 2024 field survey of 959 residents from Shanghai, China, this study employs Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression to examine the main effect of green perception on pro-greenspace behavior. A mediation model is employed to analyze the mediating role of nature connectedness, while a moderation model tests the moderating effect of “good citizen” image (face) on the stimulus–behavior relationship. The results show that green perception significantly promotes pro-greenspace behavior, positively influencing it through nature connectedness. However, the “good citizen” image (face) exerts a motivational crowding-out effect on green perception. Further analysis reveals individual heterogeneity in the expression of these effects across different types of pro-greenspace behavior. The findings highlight the importance of green space experience and the activation of environmental wisdom in traditional culture, offering new perspectives for developing strategies to guide pro-greenspace behavior.

1. Introduction

Environmental sustainability is the most important global challenge of the twenty-first century. To address this issue, while governments are actively launching initiatives to protect the environment at the policy level, there is still a need to adjust the relationship between human beings and nature, and efforts to protect the environment at the individual level are also critical [1]. And public participation is an important symbol of modern environmental governance and an important way to build an ecological civilization and a beautiful China [2].

Rapid urbanization driven by China’s economic development has led to a dramatic surge in urban populations, especially in its megacities, where high density has exacerbated environmental problems such as air pollution and ecological degradation [3]. As a key component of urban green infrastructure, public parks play multiple roles in improving the urban environment and enhancing residents’ quality of life [4]. However, in Chinese megacities like Shanghai, Tianjin, Shenzhen, and Chengdu, per-capita park green space in 2023 stood at only 9.4, 9.9, 14.69, and 10.35 m2, respectively, all below the national average of 15.65 m2, with Shanghai and Tianjin falling under 10 m2. Under the compact-development strategy of megacities, optimizing the stock of existing green spaces may be more feasible than expanding them. At the same time, urban residents in China rely primarily on the existing greenspace network for their daily activities, and their pro-environmental behavior directly influences the efficiency of greenspace use and the effectiveness of its conservation. Therefore, it is imperative to investigate the driving factors behind pro-environmental behavior in megacities.

1.1. Influencing Factors of Pro-Environmental Behavior

Pro-environmental behavior is a conscious ecological environmental protection behavior based on personal moral values and social responsibility, commonly used interchangeably with terms such as environmentally friendly behavior, environmental concern behavior, environmental responsibility behavior, and environmental protection behavior [5,6]. Currently, scholars have conducted extensive research on the influencing factors of pro-environmental behavior. These factors mainly include individual psychological factors, such as environmental attitude, environmental concern, environmental values, environmental knowledge, behavioral intentions, place attachment, environmental commitment, personal norms, connection to nature, moral emotions, and ecological fear [7,8,9,10,11]. External environmental factors, such as social moral obligations and environmental policies, are also significant [12,13]. In addition, social demographic factors such as gender [14], income, education, and age [15] are important.

The aforementioned research provided an important foundation for this study. However, it predominantly explored pro-environmental behavior from a singular perspective, focusing either on internal or external factors. Based on our review of the existing literature, we found that few studies integrated external factors such as green perception and internal factors like nature connectedness into a unified analytical framework to examine the directional pathways of behavioral stimuli. Moreover, much of the research was concentrated in the field of tourism [6,7], neglecting the more generalized pro-environmental behavior in public green space. To highlight the specific focus of this study, pro-environmental behavior in green space is referred to as “pro-greenspace behavior”.

Similarly, a review of the above research on drivers of pro-environmental behavior shows that most research studies adopt classic Western frameworks—such as the SOR and VBN models [14,15,16]—implicitly assuming cultural neutrality. Nevertheless, empirical findings by Littleford et al. [17] suggest that behavioral spillover effects across different cultural and contextual environments are minimal. Additionally, Staats [18] have called for context-specific investigations of behavior, underscoring the critical role of external circumstances in shaping behavior. Pro-greenspace behavior is rooted in particular cultural milieus, so studying it without considering culture entails inherent shortcomings.

1.2. Consideration of Face Culture

Impression management theories [19,20] demonstrate that individual behavior is influenced by external environments. Further, East Asian collectivist societies tend to construe the self relationally and contextually [21], rendering face—the socially conferred dimension of self-identity—particularly salient in China’s high-context culture [22]. Face not only motivates self-presentation but also embodies social expectations of the “good citizen”. Therefore, under the same norm or stimuli, individuals with strong face orientation are likely to behave differently from those with weak face orientation—making it essential to take face into account when designing and effectively implementing environmental policies.

Although face as a cultural concern has been employed to explain consumer differences between Asia and the West [23,24], few studies have examined how face consciousness promotes individuals’ public environmental behavior [25], and even fewer have treated face as a sociocultural symbol to explore its interactions with other driving factors. Consequently, rather than focusing solely on the single pathway from green perception to nature connectedness to pro-greenspace behavior, we further introduce face as an external contextual factor to investigate how it strengthens or weakens the green perception pathway, thereby providing a more comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms underlying megacity residents’ pro-greenspace behavior.

1.3. Issues to Be Addressed

This study aims to deepen the understanding of the complex mechanisms driving urban residents’ pro-greenspace behavior and to provide practical insights for designing culturally informed environmental policies and promoting sustainable urban green space management. Specifically, we seek to address the following key questions: (1) Can an extended Stimulus-Organism-Response model (SOR), namely the Context-SOR (C-SOR), be developed to integrate both external contextual factors and internal affective factors into the analysis of pro-greenspace behavior? (2) How does residents’ green perception influence their pro-greenspace behavior? Does nature connectedness serve as a mediator in this relationship? (3) Within the specific context of Chinese culture, what is the moderating role of the concept of face? Which has a greater influence—face or green perception? (4) Are there behavioral differences among groups distinguished by age, gender, and economic income? Addressing these questions will enhance our understanding of the underlying drivers of pro-greenspace behavior and provide scientific evidence for policymakers and environmental organizations to foster active individual participation in environmental protection, thereby improving the long-term cultivation mechanisms for pro-greenspace behavior.

2. Theoretical Framework and Research Hypotheses

2.1. C-SOR: An Extended Theoretical Model of SOR

The Stimulus-Organism-Response (SOR) model, first proposed by Mehrabian and Russell [26], describes how external stimuli in the physical environment influence an individual’s internal states. Specifically, these stimuli affect internal affective and cognitive processes (the organism), which subsequently determine the individual’s behavioral responses.

In the context of this research, the “stimulus” (S) in the Stimulus Organism Response Modeling framework is the perceived senses of urban dwellers to the green space, which is the antecedent cause of nature connectedness, and enhances human-nature connection through visual-tactile multisensory stimuli, such as air, temperature, humidity, and so on [27]. “Organism” (O) refers to an individual’s internal affective state, where affect is a response to a specific stimulus and a more stable physiological appraisal and experience [28], and in this research, that is nature connectedness. “Response” (R) refers to pro-greenspace behavior, which has a strong altruistic attribute.

People have social attributes, and the traditional values of Chinese culture emphasize that “social people” should abide by the public order and good customs that have been formed through social operation, and abide by the system and observe the rituals. Therefore, when examining individual behavioral decision-making, it is essential to consider various tangible and intangible external contextual factors present in specific spatial and temporal settings—such as tangible environmental policies [13] or intangible social norms [16]—and explore their direct or indirect influence on individual behavior. This is consistent with theoretical perspectives in environmental behavior research that emphasize the role of contextual factors. For example, the ABC model systematically explains the critical influence of context in shaping behavior [29]. Based on this understanding, the present study expands the classical SOR framework by incorporating contextual factors (context), resulting in the development of the Context-SOR (C-SOR) theoretical model. This framework posits that the relationship between perception and behavior is stronger when contextual influence is neutral, while extremely favorable or unfavorable contextual conditions may significantly promote or inhibit behavioral responses.

Therefore, in the context of this study, it is necessary to clarify that residents’ pro-greenspace behavior is learned behavior embedded in local cultural scenes, to cultivate residents’ pro-greenspace behavior from the perspective of “participant in life”, and to value and activate the environmental wisdom of traditional culture. Confucianism has long dominated traditional Chinese culture, and Confucian values based on group orientation and interpersonal relationships have a profound impact on the behavior of the Chinese people, who are more concerned about the opinions of others under the tendency of collectivism, and who value face more. The Chinese scholar Lin Yutang pointed out that face is “the most subtle point of Chinese social psychology, but it is the most delicate criterion for Chinese social interaction” [30]. From a social psychological perspective, face represents a form of social self-awareness in interpersonal interactions. It serves both as an internal mechanism for self-regulation and as an external form of social pressure that enforces behavioral norms [22]. Similarly, other societies influenced by Confucianism—such as Vietnam, North Korea, and South Korea—also exhibit strong collectivist orientations and place a high value on face in guiding social behavior [31].

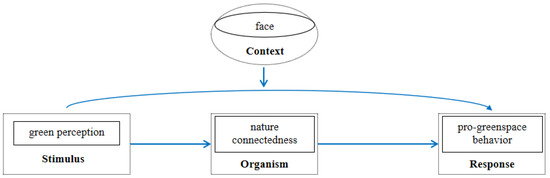

Combining the above analyses, this research constructed a theoretical framework as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

C-SOR: an extended theoretical framework of SOR.

2.2. The Impact of Green Perception on Pro-Environmental Behavior

The natural environment, as a physical presence, cannot directly drive individuals to engage in protective behaviors. However, the green perception generated through contact with nature acts as an external stimulus exerted on an individual’s senses. Green perception can be associated with pro-environmental behavior [32,33]. For example, contact with nature is likely to generate emotional affinity [34], promote attention restoration and recovery [35,36], reduce stress and trigger positive emotions [37,38], lead to the perception of environmental degradation [39,40,41], and foster the emergence of “green altruism” [42]. All of these factors contribute to the formation of pro-environmental behavior. Thus, hypothesis 1 was formulated.

Hypothesis 1.

Residents’ green perception positively influences pro-greenspace behavior.

2.3. Mediating Effect of Nature Connectedness

Nature connectedness—the sense of unity between individuals and the natural world—is often regarded as an innate human tendency. According to the biophilia hypothesis, humans are inherently drawn to life and natural environments, possessing an intrinsic capacity and motivation to affiliate with the natural world [43]. From an evolutionary perspective, species with stronger connections to nature were more likely to survive under natural selection. Therefore, the human inclination toward nature connectedness is considered a genetically rooted psychological trait developed through long-term evolutionary processes [44]. Nature connectedness may be dormant in human bodies due to the emergence of modern civilization, but urban green spaces, as indispensable public spaces for residents’ daily lives, provide them with places for rest, exercise, and cultural recreation. And the presence of a sufficient number of trees, colorful flowers, and water features represent healing and relaxation, and have an emotional bond [45]. When urban dwellers spend time in green spaces, long-lost nature connectedness can be released and strengthened, while spending less time in green spaces may hinder connection to nature [46].

Nature connectedness as an internal affective state, on the other hand, is a special association between urban dwellers and natural places, which involves an emotionally positive attachment between humans and nature [47], and attachment facilitates empathy [48]. According to the Empathy Altruism Hypothesis [49], when an individual witnesses another person’s misfortune, he or she will have an emotional response of compassion under the effect of empathy, which prompts the individual to develop a strong desire to help the other person. The concept of empathy is further extended to the relationship between humans and nature along with the global ecological crisis, that is, empathy with nature, which is the ability to perceive the situation that nature is in and to understand it emotionally [50]. Empirical studies have shown that empathy with nature significantly predicts individuals’ pro-environmental behavior [51,52]. Therefore, there is a correlation between empathy with nature and pro-greenspace behavior.

Meanwhile, Psychodynamic Theory also better supports the relationship between nature connectedness and pro-greenspace behavior. Marx’s Psychodynamic Theory emphasizes that needs are the driving force of human activities and development, that is, all human behaviors are derived from human needs. When the need reaches a certain intensity, the individual will unleash the driving force to motivate him or her to take action. In the context of intensifying global ecological problems, the higher the need for the natural environment, the stronger the connection to nature, and the more individuals empathize with the harms and consequences of the natural world, the stronger the psychological motivation to practice pro-greenspace behavior will be [51]. Thus, hypothesis 2 was formulated.

Hypothesis 2.

Nature connectedness mediates the effect of green perception on pro-greenspace behavior.

2.4. The Moderating Role of Face and Individual Heterogeneity

Face, as a social and cultural concept, is a key term that reveals the characteristics of Chinese cultural context [24]. The social operation of face is fundamental to understanding the psychology and behavior of Chinese people, while also connecting to the understanding of Chinese social structure [30,53]. In the context of Chinese culture, the face culture can be divided into two dimensions: “desire for face” and “fear of losing face”. This dual-dimensional structure has been confirmed in a relevant study [54]. Individuals who “desire face” tend to engage in more proactive behaviors to gain face. On the other hand, “fear of losing face” is an emotional response when face is threatened, resulting in negative emotions such as embarrassment, anxiety, anger, and shame, which in turn trigger face-saving behaviors [55]. This reflects an individual’s need for recognition and approval from others [56].

As environmental issues have become a growing concern in society, people have started to support and advocate for environmentally friendly lifestyles. Green space, as public open space, possesses symbolic and social characteristics. Engaging in green space protection behavior can reflect the public’s environmental literacy and economic status to a certain extent. Therefore, pro-greenspace behavior not only brings social benefits but is also considered socially acceptable. It can be used to “project a positive image to others”, thereby maintaining one’s “good citizen” image and enhancing one’s status within the surrounding group.

For both individuals who “desire face” and those who “fear losing face”, adopting pro-greenspace behavior carries positive externalities, making it an important way to gain respect and recognition from society and others. In a high-context culture that emphasizes face, individuals are more easily driven by face culture. Individuals with a stronger awareness of face are more likely to adjust their behaviors according to social expectations and the evaluations of others in order to maintain their position and image within the group. In the domain of pro-environmental behavior, this is manifested through adopting various pro-greenspace behaviors such as maintenance, contribution, and promotion. The emergence of such behaviors is not due to the multi-sensory stimuli provided by the natural environment, and to some extent, it may replace or even “crowd out” the positive driving effect of green perception on pro-green space behavior.

However, the effects of face on individuals with different traits are not uniform [57]. The youth group, for instance, has a collective vision of “light socialization” [53] and tends to resist being constrained by face and the gaze of others. High-income individuals, on the other hand, place more importance on a high quality of life and a wealthy face [58], rather than focusing on environmental attributes. Men are often socially expected to be strong, enduring, and resilient, holding traditional gender views, and are more concerned with “face” [59]. Thus, hypotheses 3 and 4 were formulated.

Hypothesis 3.

Face negatively moderates the role of green perception on pro-greenspace behavior, with a “crowding out” effect between the two.

Hypothesis 4.

There are differences in the influence of green perception on pro-greenspace behavior based on age, income, and gender.

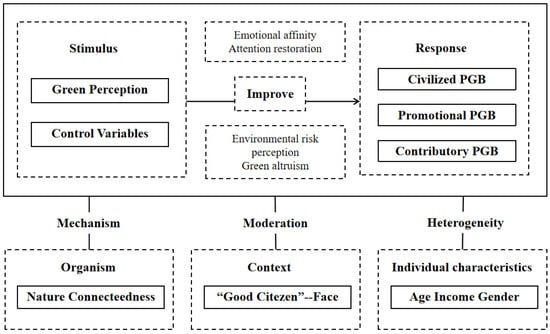

Figure 2 summarizes the theoretical analysis framework of the impact of GP on PGB, suggesting that GP exacerbates the level of PGB through the nature connectedness, “good citizen” image, that is, face exacerbates the positive correlation between GP and PGB, and the impact of GP on PGB has individual heterogeneity.

Figure 2.

Theoretical analysis framework of the impact of GP on PGB.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection

In order to investigate the mechanism of residents’ green perception on pro-greenspace behavior and the moderating role of the concept of face in the context of traditional Chinese culture, this research took Shanghai as a survey sample and conducted a field study using a questionnaire in July 2024. According to statistical tables and graphs on economic and social development, basic information on the population of megacities and very large cities in the Seventh National Population Census [60] shows that the urban resident population of Shanghai has reached 19.87 million, which is within the classification of megacities and very large cities. However, compared with other megacities in China, such as Beijing, Tianjin, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, and Chengdu, Shanghai ranked second only to Beijing in terms of per capita GDP in 2023, but the per capita area of green space in Shanghai’s parks was only 9.4 square meters, which placed it last. Residents respond more strongly to the supply and demand of urban green space, and as it is more significant from a policy perspective to explore residents’ pro-greenspace behavior in a megacity, Shanghai was thus chosen as a representative megacity for this survey.

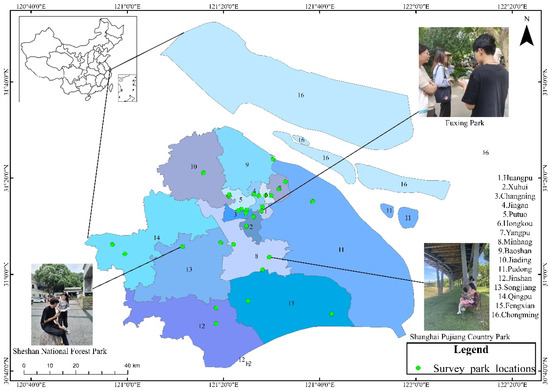

The survey covered 15 administrative districts in Shanghai, except for Chongming District, and 2–3 comprehensive parks, city parks, and country parks were sampled in each administrative district. The questionnaires were completed face-to-face through on-site distribution, interviews, filling, and on-site recovery, with 30–40 questionnaires distributed in each park. Stratified random sampling techniques were also used to ensure that all population levels were represented, with quotas for each age, educational level, gender, household registration and income level. This ensured that the sample was broadly sourced, evenly distributed, and better matched the actual situation of the urban public (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The location, administrative divisions, and survey park locations of Shanghai City, 2024.

A total of 1057 questionnaires were distributed in the survey, and 959 valid samples were recovered after excluding invalid questionnaires, for a validity rate of 90.73%. The detailed breakdown is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics.

3.2. Measures

Well-established scales in this field were used in this research, and were adapted to apply to the green space context of this research. Reliability and validity tests were conducted in conjunction with the sample of this research.

For the pro-greenspace behavior scale, based on the research of N. J. Smith-Sebasto et al. [61], the scale was divided into a total of six question items: “I will consciously abide by the rules and regulations of the green space”, “I will dispose the garbage I create in the green space”, “will take the initiative to persuade other visitors to damage the green space”, “I will buy or give up certain products to protect the green space”, “I will persuade my family and friends to adopt behaviors that are beneficial to the green space”, and “I am willing to pay/donate a certain amount of money for the protection of the green space”.

For the green perception scale, this research drew on Grahn & Stigsdotter’s [62] study and applied the five categories of perceived attributes, namely, sense of nature, culture, socialization, diversity, and openness, to set up the following five question items: “There is a free-growing lawn here; it is not crowded and people feel safe”, “There is a humanistic atmosphere here, such as fountains, statues, flowers, etc.”, “There are venues for dining and recreational activities, so you can meet many people”, “There are many plants and animals here (e.g., birds, insects, flowers and trees)”, “It is not disturbed by too many roads, spacious and free, surrounded by trees”.

For the nature connectedness scale, three question items based on Mayer & Frantz’s [47] study were set as follows: “I have a deep understanding of how my behavior affects nature”, “I feel that I am part of the natural web of life”, “I believe that both humans and living things share the same life force”.

For the Chinese concept of face scale, this research drew on Shi et al.’s [63] scale and selected a total of four items: “I want to have good character and behavior”, “I desire to be a role model for others in the use and maintenance of public greenspace”, “I fear that my negligence could damage my reputation”, “I worry that if my behavior does not conform to social norms, I will lose face”.

All items were scored on a five-point Likert scale with individual subjective assignments, ranging from “disagree”, “relatively disagree”, “generally”, and “relatively agree” to “agree”, with scores of 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, respectively. We averaged the scores of each item to obtain a continuous variable, and the higher the score was, the stronger the attributes of green perception, nature connectedness, pro-greenspace behavior, and face.

Control variables included individual characteristics (gender, household registration, age, education, income), household characteristics (type of house, number of elders, number of children), and historical activity characteristics (monthly browsing frequency, average activity time).

SPSS26 software was used to calculate Cronbach’s Alpha. Cronbach’s Alpha for each variable was greater than 0.75, which indicated that the scale used in this study had high reliability. We used Amos24 software to test the validity of the scale, and the results showed that the combined reliability (CR) of each variable was greater than the reference value of 0.7, and the average extracted variance (AVE) was above 0.5, indicating that the scale used in the research had good convergent validity.

3.3. Model Specification

- The OLS regression model and mediation effect model

Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression was employed in this study using StataSE-64 software. All variables exhibited VIF values below 1.52, indicating no multicollinearity. The Breusch–Pagan/Cook–Weisberg test for heteroskedasticity yielded a chi2 value of 2.08 (p = 0.1495), indicating homoscedasticity. The Shapiro–Wilk test for normality of residuals showed W = 0.998 with a p-value of 0.375, indicating that the residuals followed a normal distribution. These results confirmed that all OLS assumptions were met, and the regression model was reliable. Using the Baron and Kenny (1986) [64] approach for evaluating mediating variables, this paper developed three econometric models to investigate the dynamic mechanisms influencing individuals’ pro-greenspace behavior in response to green perception.

Let PGB denote pro-greenspace behavior, GP represent green perception, M indicate nature connectedness, that is, mediator variable, and Control denote control variables. Equation (1) examines the link between residents’ green perception and pro-greenspace behavior; Equation (2) tests the relationship between green perceptions and nature connectedness; and Equation (3) examines the effects of residents’ green perception and nature connectedness on pro-greenspace behavior. , , and are constant terms, and , and , and , and are regression coefficients, and , , are random perturbation terms. Provided that is significant, if both and are significant, this indicates that the nature connectedness plays a partially mediating role; if is not significant, but is significant, the nature connectedness plays a fully mediating role; if is not significant, there is no mediating role.

- The moderating effect model

In order to verify the moderating effect of the concept of face, the following moderating effect model was constructed by introducing the interaction term of green perception and face:

In the formula, face is the Chinese concept of face, , , and are the regression coefficients. If the regression coefficient > 0, it means that the concept of face has a positive moderating effect on the relationship, and vice versa has a negative moderating effect.

4. Results

4.1. Model Analysis of Residents’ Green Perception Influencing Pro-Greenspace Behavior

Model (1) (See Table 2) suggested the effect of residents’ green perception on pro-greenspace behavior. It can be seen that green perception significantly predicted actions to protect the green space, and the coefficient of the core explanatory variable green perception (GP) was significantly positive ( 0.350, p < 0.01, 95% CI [0.295, 0.406]). It suggests that for every one-unit increase in residents’ green perception score, their pro-greenspace behavior score increases by 0.35 units, which is significant at 1%. The result indicates that the evidence supports hypotheses 1.

Table 2.

Test of green perception influencing pro-green space behavior, the mediating effect of nature connectedness, and the moderating effect of face.

4.2. Test of the Mediating Effect of Nature Connectedness

In order to test the mediating effect of nature connectedness, regression analyses were conducted according to Equations (2) and (3), and the results are shown in Table 2. Model (2) demonstrated that residents’ green perception positively affected their degree of nature connectedness ( 0.523, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.463, 0.584]). Based on model (1), model (3) incorporated the mediator variable M. It can be seen that the coefficients of both the mediator variable and the core explanatory variable were significantly positive ( 0.263, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.152, 0.274]; 0.213, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.206, 0.319]), and the coefficient of GP decreased compared with that of model (1), which suggested that there was only a partial mediating effect. That is, residents’ green perception (GP) partially influences their pro-greenspace behavior (PGB) through nature connectedness (M). This result is consistent with the analysis of the SOR theoretical model and supports hypotheses 2.

4.3. Test of the Moderating Effect of the Chinese Concept of Face

In order to test the moderating effect of face, regression was conducted according to Equation (4), and the empirical regression result is shown in Table 2. According to model (4), the coefficients of both green perception (GP) and the Chinese concept of face (face) were significantly positive ( 0.307, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.245, 0.369]; 0.147, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.101, 0.193]), and the coefficient of the interaction term of green perception and face (GP × face) was −0.0733, which was still significant at 1%. These indicate that both green perception and face alone can promote pro-greenspace behavior, but face has a negative moderating effect in the influence of residents’ green perception on pro-greenspace behavior, suggesting a substitution relationship between green perception and face.

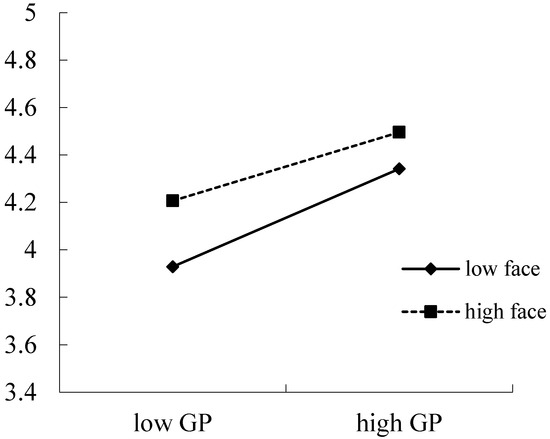

In order to reveal more clearly the moderating role of face in residents’ green perception and pro-greenspace behavior, a simple slope test was conducted. As shown in Figure 4, the simple slope under low face was 0.361 (t = 8.491, p < 0.001), which was higher than that under high face (0.253, t = 5.969, p < 0.001), indicating that green perception is more likely to drive pro-greenspace behavior in individuals with low face. Overall, face negatively moderates pro-greenspace behavior at different levels of green perception, by weakening the positive relationship between green perception and pro-greenspace behavior. This finding is consistent with the analysis of the C-SOR theoretical model and supports hypothesis 3.

Figure 4.

Moderating effect of the Chinese concept of face in the relationship between residents’ green perception (GP) and pro-greenspace behavior (PGB).

4.4. Heterogeneity Analysis

Due to differences in socio-demographic characteristics, groups with different incomes, genders, and ages differ in their perception of the external green environment and face culture, and these differences can affect their decisions to engage in pro-greenspace behaviors differently. At the same time, according to the motivation of the purpose of the behavior, different types of pro-greenspace behaviors are also affected differently by these factors, such as civilized behaviors (e.g., obeying rules and regulations, and not littering in green spaces), promotional behaviors (e.g., persuading family members and friends, and exhorting others to avoid green space-destroying behaviors), and contributory behaviors (donating money or stopping participation in green space-destroying consumption behaviors).

4.4.1. Economic Income Differences

As different income groups have different responses to face and green perception, we constructed different income sub-sample models. Based on the mean value of income, the group that was larger than the mean value of the total sample income was categorized as the high-income group, and vice versa was categorized as the low-income group. Overall, green perception is driven more than face regardless of income level. However, comparing model (5) and model (9), for the general pro-greenspace behavior, the face drive of the high-income group was stronger ( = 0.256, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.185, 0.327]), and the face and green perception produced a certain motivational crowding effect ( = −0.077, p < 0.1, 90% CI [−0.153, −0.0008]), while the green perception of the low-income group had a more stimulating effect on its pro-greenspace behavior ( = 0.387, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.293, 0.481]). Comparing models (6–8) and (10–12), in terms of the performance of different types of pro-greenspace behavior, the face drive of the high-income group is the strongest factor contributing to pro-greenspace behavior, while the low-income group is still more driven by green perception (Table 3).

Table 3.

Performance of different economic income groups in terms of different types of pro-greenspace behavior.

4.4.2. Gender Differences

Table 4 presents the models for the different gender subsamples. Overall, for both genders, green perception drives pro-greenspace behavior more than face. However, comparing models (13) and (17), for general pro-greenspace behavior, men were more positively influenced by face ( = 0.195, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.127, 0.264]), and women’s behavior relied more on green perception ( = 0.292, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.212, 0.372]), with face having a larger substitution effect ( = −0.151, p < 0.01, 95% CI [−0.249, −0.053]). Comparing models (14–16) and (18–20), in terms of the performance of different types of pro-greenspace behavior, face exerts a stronger influence on men’s promotional and contributory pro-greenspace behavior. Also, it is worth noting that in civilized pro-greenspace behavior, face further enhances the drive of green perception on males’ behaviors. For women, green perception remains the primary driver, while face exhibits a negative moderating effect.

Table 4.

Performance of different gender groups in terms of different types of pro-greenspace behavior.

4.4.3. Age Differences

In the age sub-sample models, the division was based on the mean value of age, and those greater in age than the total sample age mean were classified as the older group, while those lower in age than the total sample age mean were classified as the younger group. Overall, for both young and old, green perception drives pro-greenspace behavior more than face. However, comparing models (21) and (25), for general pro-greenspace behavior, older individuals were more strongly driven by face ( = 0.179, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.090, 0.268]), and there was a crowding out effect of face on green perception ( = −0.148, p < 0. 1, 90% CI [−0.290, −0.005]). Contrarily, the pro-greenspace behavior of younger individuals was more dependent on green perception ( = 0.293, p < 0. 1, 95% CI [0.227, 0.358]). Comparing models (22–24) and (26–28), older individuals exhibit stronger face-driven effects in contributory pro-greenspace behavior. Across all three types of pro-greenspace behavior, younger individuals remain more strongly driven by green perception (Table 5).

Table 5.

Performance of different age groups in terms of different types of pro-greenspace behavior.

5. Discussion

Our research aimed to make three contributions to the pro-environmental behavior literature. First, we examined the influence of residents’ green perception on pro-greenspace behavior in the presence of external stimuli from the natural environment, and in particular, whether natural connectedness can be a mechanism to explain the relationship between green perception and pro-greenspace behavior. Second, we examined how face, an important component of socio-cultural factors, influenced individual behavioral decisions in the context of traditional Chinese culture, which in turn answered the question of whether to choose a nature-based or a society-based solution. Finally, we examined the differences in the drivers of different types of pro-greenspace behavior across economic income, gender, and age groups from the perspective of individual heterogeneity.

5.1. Green Perception, Nature Connectedness, and Pro-Greenspace Behavior

The results of this research suggest that higher levels of green perception drive the emergence of pro-greenspace behavior through nature connectedness. Although consistent with studies that have observed that individuals with higher levels of nature exposure are more likely to develop pro-environmental behavior [65,66,67], which make it known that contact with natural environments can have an impact on an individual’s behavior, our findings extend previous research. First, we place the context in a public urban green space, rather than a domestic space or a residential neighborhood, to explore both specific and general pro-greenspace behavior of residents in public urban green space. Second, the research not only explores the influence of natural exposure, but also broadens to the role of the green space environment as an external stimulus for the perceived naturalness, culture, openness, socialization, and perceived diversity of the residents.

Apart from the adequate research addressing the key role of nature connectedness in the enhancement of pro-environmental behavior [68,69,70], the potential mediating effect of nature connectedness on the relationship between green perception and pro-greenspace behavior has not been tested. To fill this gap, the present research adopted a mediation analysis to examine whether nature connectedness mediated the association between green perception and pro-greenspace behavior. Results suggested a mediating role of nature connectedness, that the psychological connection brought about by green perception was more important than nature contact alone, and that the individual’s emotional connection to nature changed the way the individual responded when faced with nature contact, which generated pro-greenspace behavior. At the same time, our findings went beyond contextualization such as tourist destinations or childhood [48,71], while using natural connectedness as mediator, calling for a “green perception of nature” and “psychological connection” as a “cure” for PGB in a broader context. Therefore, interventions that increased residents’ green experience and connection to nature were needed to realize improvements in urban ecological health. This is also a growing concern in the field of nature connectedness [48,72].

5.2. The Role of Face

In our study, residents’ face promoted pro-greenspace behavior, which was in line with [25], while more studies had also explored the influence of face on pro-environmental behavior to guide others’ green behavior, such as the protection of tourist sites and preferential consumption of eco-products [73,74,75]. Our study further extended its application. We explored whether we could choose to guide residents’ pro-greenspace behavior by increasing green supply or imposing face constraints in the process of megacity green space governance.

If we considered the interaction between motives, the face culture would conflict with individuals’ green perception, which meant that the face motive “squeezed out” the positive effect of green perception on pro-greenspace behavior. According to traditional and neoclassical economics, people are rational and seek to maximize their personal utility; however, experimental evidence suggested that individuals did not always act rationally and often deviated from the assumptions of rational choice theory [76]. In this context, scholars had extended the rational choice model, and a typical example was that the utility function was extended to include a variety of motives. When multiple motives coexisted, there was interaction between different incentive modes to some extent, leading to mutual enhancement, weakening, or even offsetting of incentive effects, that is, the “crowding-in effect” or “crowding-out effect” emphasized by the theory of motivational crowding [77]. Furthermore, from the perspective of social norms theory, in cultures oriented toward collectivism, individuals’ behaviors are more susceptible to external evaluations and social expectations [78]. Behavior originally driven by other motivations may be adjusted due to socially oriented motives such as face. This further confirms that among individuals with a strong concern for face, pro-greenspace behaviors are more likely to be driven by face-related motives, thereby weakening the influence of green perception.

Considering the crowding-out effect of face on green perception, we could have two understandings. On one hand, the role of face culture in urban green space governance could not be ignored. For the “good face” groups, even if they did not perceive a satisfactory green space environment, out of the need for social identity, they would engage in the protection of green space. As a socio-cultural force, the flexible governance role of face could be utilized. On the other hand, this also had a drawback: a superficiality of behavior was produced. That is, individuals adopted short-term protection behavior only in the context of social concerns and expectations, rather than out of long-term concerns and deep knowledge of the green space environment. This was not conducive to the long-term protection of green space, and thus, in addition to relying on the short-term incentives of face culture, improving the quality of green space provision and enriching the green space experience of the residents were needed, which would lead to long-term sustainable protection behavior. Furthermore, future research might need to examine the short-term effects of face culture and the long-term effects of green perception to more directly demonstrate the differences in their effects in the time dimension.

From a comparative cultural perspective, similar face-related dynamics can also be observed in other East Asian collectivist cultures, such as South Korea and Vietnam [21], although the cultural expressions and social expectations may differ. In contrast, in more individualistic societies like the United States, concerns about public image are often manifested through concepts such as impression management or self-presentation [19,20], rather than the traditional notion of “face”. These cultural differences highlight the importance of contextualizing social motivations in behavioral research.

5.3. Impact of Individual Heterogeneity on Research

Pro-greenspace behavior can be viewed as an individual effort to contribute to collective environmental quality, representing the private provision of public goods, with income playing a crucial role in this framework [79]. Our study found that face had a greater impact on pro-greenspace behavior among high-income groups compared to low-income groups, as high-income individuals valued face more and usually gained face through symbolic actions. This finding is consistent with Zhang et al. [80] and Fu & Gu [81].

Additionally, when analyzing the differences in the drivers of pro-greenspace behavior across various age groups, we found that older individuals cared more about face, and their face-driven motivation was stronger than that of younger groups. This was because older adults’ sense of social identity often depended on strong interpersonal relationships, making face a significant factor in their behavioral decisions under collectivist cultural contexts, as supported by IMAMOĞLU et al. [82] and Li et al. [83]. However, our study went further and revealed that high-income and older groups exhibited stronger face-driven behavior in contributory pro-greenspace behavior. This could be explained by research on face-saving and conspicuous consumption [84], where contributory behavior is high-cost behavior, and the more money one spends, the more face one gains. Nevertheless, it was important to be mindful of the “crowding-out effect” of face on green perception. In contrast, low-income and younger groups were less influenced by face and cared more about the stimulation of nature, culture, and diversity offered by green spaces.

The analysis of gender differences showed that, compared to females, males had a stronger face-driven motivation for pro-greenspace behavior, particularly in promotional and contributory behavior. It was noteworthy that in civilized behavior, males’ face further positively moderated the effect of green perception on pro-greenspace behavior, producing a “crowding-in” effect on green perception, which was more conducive to pro-greenspace behaviors. This further reflected that males placed more emphasis on maintaining their face in external behaviors. On the other hand, females’ face “crowded out” the positive effect of green perception, which may be explained by Chen’s research [85], suggesting that women have a stronger internal desire for face, which “crowds out” the motivating effect of green perception on pro-greenspace behavior.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

Our results need to be referenced within the following limitation. The sample size of this research was one typical megacity in China, but we also need to take into account the differences in the histories of different cities, which led to specific cultural contexts. For example, traditional cities with low population mobility have more “power of interpersonal relationship” and are characterized by “acquaintance society” [86], which emphasizes the role of face, while it is not clear whether cities with higher mobility have more emphasis on the role of green perception in pro-greenspace behavior. It may be a direction we need to further study in the future.

Our study was also cross-sectional, which meant that our results represented the relationship between green perception and pro-greenspace behavior at a specific point in time rather than over time. Future research into green perception and pro-greenspace behavior should follow participants longitudinally to understand the long-term pro-greenspace behavior driven by green perception and whether this relationship changes with season and leaf-out.

6. Conclusions

By constructing an extended SOR model (C-SOR model), we concluded that green perception had promoted pro-greenspace behavior through nature connectedness, while face created a motivational crowding effect that weakened the influence of green perception, manifesting as a “crowding out” effect. In other words, the need to save face led to superficial behaviors, with individuals adopting short-term conservation actions in specific situations without long-term concern for green space. However, face culture could sometimes play a positive role; individuals motivated by a desire to maintain face may engage in green space protection to fulfill this social need. Overall, green perception had a greater influence on pro-greenspace behavior than face. Across different groups, although green perception was consistently a stronger driver than face, face had a more significant influence on high-income individuals, older adults, and men, particularly in contributory pro-greenspace behaviors. Therefore, whether the focus is on enriching the public’s green space experience by increasing green space supply or leveraging the flexible governance potential of face culture, future policy designs should carefully consider the balance.

Based on the findings of this study, we propose the following policy recommendations:

On one hand, it is essential to enrich residents’ green space experiences from multiple dimensions to meet their diverse needs. Green space should provide high-quality air, comfortable temperatures, natural sounds, and aesthetically pleasing environments. Where appropriate, basic facilities such as fitness trails and exercise areas should be installed to promote physical and mental well-being. Additionally, designing community gardens and outdoor gathering spaces can enhance residents’ sense of belonging and social cohesion. Finally, ecological signage and nature experience activities should be implemented to enrich residents’ environmental knowledge and deepen their emotional connection with nature.

On the other hand, the flexible governance role of face culture should be fully leveraged. At the community level, culturally tailored promotional activities can be designed, such as “Green Family” awards or the establishment of “Green Pioneer” titles, with honor rolls displayed publicly to encourage enthusiasm for green space protection. This approach satisfies residents’ social motivation to “gain face” while also invoking social supervision that triggers a “fear of losing face”, thus reinforcing behavioral constraints. Furthermore, integrating elements of face culture into urban planning and design—for example, installing signs like “Maintained by Volunteer A” or organizing “Adopt a Tree” programs with regular public disclosures—makes residents’ green behavior visible, thereby effectively fostering sustained pro-greenspace behavior.

In summary, this study enriches the understanding of the complex driving mechanisms behind pro-greenspace behavior by constructing an extended Stimulus-Organism-Response model (C-SOR) that incorporates cultural contextual factors, filling a gap in the interdisciplinary research of culture and environmental behavior. The findings not only deepen the theoretical framework but also provide scientific evidence for policy formulation, contributing to the sustainable management of urban green space and enhancing public participation in environmental protection.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.J.; methodology, Y.J.; software, Y.J.; formal analysis, Y.J.; investigation, Y.J. and G.H.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.J.; writing—review and editing, F.M. and T.C.; visualization, Y.J.; funding acquisition, F.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, Grant No. 2021SJZ01.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PGB | Pro-greenspace Behavior |

| GP | Green Perception |

| M | Nature Connectedness |

| face | Chinese concept of face |

| GP × face | Interaction term of green perception and face |

| domi | Household registration |

| edu | Education |

| old | Number of elders |

| child | Number of children |

| toh | Type of house |

| fre | Monthly browsing frequency |

| stay | Average activity time |

| Civil-PGB | Civilized pro-greenspace behavior |

| Promo-PGB | Promotional pro-greenspace behavior |

| Contri-PGB | Contributory pro-greenspace behavior |

References

- Zhang, D.; Yu, Y.; Guo, W. When do individuals take action to protect the environment?—Exploring the mediating effects of negative impacts of environmental risk. J. Environ. Psychol. 2024, 100, 102472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.N.; Qin, C.B.; Xue, Q.; Lu, L.; Zhang, J.W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.J.; Xioang, S.G.; Qiang, Y.; Xiao, Y. Research on the construction of a Beautiful China Initiative from the perspective of ecological civilization: Review and Prospect. China Environ. Sci. 2024, 45, 1136–1147. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, A.G.O.; Chen, Z. From cities to super mega city regions in China in a new wave of urbanisation and economic transition: Issues and challenges. Urban Stud. 2020, 57, 636–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, J.; Maryam, S. Aesthetic Preference and Mental Restoration Prediction in Urban Parks: An Application of Environmental Modeling Approach. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 54, 126775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, J.M.; Hungerford, H.R.; Tomera, A.N. Analysis and synthesis of research on responsible environmental behavior: A meta-analysis. J. Environ. Educ. 1987, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiatkawsin, K.; Han, H. Young travelers’ intention to behave pro-environmentally: Merging the value-belief-norm theory and the expectancy theory. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.K.; Weiler, B. Visitors’ attitudes towards responsible fossil collecting behaviour: An environmental attitude-based segmentation approach. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 602–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.; Guagnano, G.A.; Kalof, L. A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case of environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999, 6, 81–97. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/24707060 (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- Fahlquist, J.N. Moral responsibility for environmental problems—Individual or institutional? J. Agric. Environ. Ethic. 2009, 22, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Soopramanien, D. Types of place attachment and pro-environmental behaviors of urban residents in Beijing. Cities 2019, 84, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig-Lewis, N.; Palmer, A.; Dermody, J.; Urbye, A. Consumers’ evaluations of ecological packaging–Rational and emotional approaches. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 37, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berenguer, J.; Corraliza, J.A.; Martin, R. Rural-urban differences in environmental concern, attitudes, and actions. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2005, 21, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantari, K.; Fami, H.S.; Asadi, A.; Mohammadi, H.M. Investigating factors affecting environmental behavior of urban residents: A case study in Tehran City-Iran. Am. J. Environ. Sci. 2007, 3, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, L. Understanding residents’ green purchasing behavior from a perspective of the ecological personality traits: The moderating role of gender. Soc. Sci. J. 2024, 61, 668–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, S.; Leisch, F. Selective marketing for environmentally sustainable tourism. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 672–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornara, F.; Molinario, E.; Scopelliti, M.; Bonnes, M.; Bonaiuto, F.; Cicero, L.; Admiraal, J.; Beringer, A.; Dedeurwaerdere, T.; de Groot, W.; et al. The extended Value-Belief-Norm theory predicts committed action for nature and biodiversity in Europe. Environ. Impact. Assess. 2020, 81, 106338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littleford, C.; Ryley, T.J.; Firth, S.K. Context, control and the spillover of energy use behaviours between office and home settings. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staats, H. Understanding proenvironmental attitudes and behavior: An analysis and review of research based on the theory of planned behavior. In Psychological Theories for Environmental Issues; Ashgate: Aldershot, UK, 2003; pp. 171–201. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, E. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life; (Original work published by Doubleday); Penguin Books: Harmondsworth, UK, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Leary, M.R.; Kowalski, R.M. Impression management: A literature review and two-component model. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 107, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triandis, H.C. Individualism-collectivism and personality. J. Pers. 2001, 69, 907–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, A.; Francesco, A.M.; Kessler, E. The relationship between individualism-collectivism, face, and feedback and learning processes in Hong Kong, Singapore, and the United States. J. Cross. Cult. Psychol. 2003, 34, 72–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, N.Y.; Ahuvia, A.C. Personal taste and family face: Luxury consumption in Confucian and Western societies. Psychol. Market. 1998, 15, 423–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juan Li, J.; Su, C. How face influences consumption-a comparative study of American and Chinese consumers. Int. J. Market. Res. 2007, 49, 237–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.H.; Dou, L.L. The Influencing Factors of Face Awareness on the Public’s Environmental Behavior in the Public Domain. Jiangsu Soc. Sci. 2021, 90–100+243. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Frumkin, H.; Bratman, G.N.; Breslow, S.J.; Cochran, B.; Kahn, P.H., Jr.; Lawler, J.J.; Levin, P.S.; Tandon, P.S.; Varanasi, U.; Wolf, K.L.; et al. Nature Contact and Human Health: A Research Agenda. Environ. Health Persp. 2017, 125, 075001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, J.; Malhotra, N.K. An integrated model of attitude and affect: Theoretical foundation and an empirical investigation. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guagnano, G.A.; Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T. Influences on attitude-behavior relationships: A natural experiment with curbside recycling. Environ. Behav. 1995, 27, 699–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.G.; Hu, X.J. Favor and Face: Power Games of Chinese; Renmin University Press: Beijing, China, 2010. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hall, G.C.; Hong, J.J.; Zane, N.W.; Meyer, O.L. Culturally competent treatments for Asian Americans: The relevance of mindfulness and acceptance-based psychotherapies. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2011, 18, 215–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hipólito, J. The Sensorial Effect: Dynamics of Emotion in Pro-Environmental Behavior. Appl. Environ. Educ. Commun. 2011, 10, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Shao, Y.; Hao, Y.; Lu, X. Perceived Soundscape Experiences and Human Emotions in Urban Green Spaces: Application of Russell’s Circumplex Model of Affect. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dopko, R.L.; Capaldi, C.A.; Zelenski, J.M. The psychological and social benefits of a nature experience for children: A preliminary investigation. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 63, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; Korpela, K.; Evans, G.W.; Gärling, T. A measure of restorativequality in environments. Scand. Hous. Plan. Res. 1997, 14, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, T.R.; Black, A.M.; Fountaine, K.A.; Knotts, D.J. Reflection andattentional recovery as distinctive benefits of restorative environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1997, 17, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Simons, R.F.; Losito, B.D.; Fiorito, E.; Miles, M.A.; Zelson, M. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beil, K.; Hanes, D. The influence of urban natural and built environments on physiological and psychological measures of stress—A pilot study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 1250–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homburg, A.; Stolberg, A. Explaining pro-environmental behavior with a cognitive theory of stress. J. Environ. Psychol. 2006, 26, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meloni, A.; Fornara, F.; Carrus, G. Predicting pro-environmental behaviors in the urban context: The direct or moderated effect of urban stress, city identity, and worldviews. Cities 2019, 88, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathers-Jones, J.; Todd, J. Ecological anxiety and pro-environmental behaviour: The role of attention. J. Anxiety Disord. 2023, 98, 102745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guéguen, N.; Stefan, J. “Green altruism” short immersion in natural green environments and helping behavior. Environ. Behav. 2016, 48, 324–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.O. Biophilia; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Kellert, S.R.; Wilson, E.O. The Biophilia Hypothesis; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini, F.; Sajadzadeh, H.; Aram, F.; Mosavi, A. The impact of local green spaces of historically and culturally valuable residential areas on place attachment. Land 2021, 10, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, R.; Basu, M.; Hashimoto, S.; Estoque, R.C.; Kumar, P.; Johnson, B.A.; Mitra, B.K.; Mitra, P. Residents’ place attachment to urban green spaces in Greater Tokyo region: An empirical assessment of dimensionality and influencing socio-demographic factors. Urban For. Urban Green 2022, 67, 127438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, F.S.; Frantz, C.M. The connectedness to nature scale: A measure of individuals’ feeling in community with nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.C.H.; Monroe, M.C. Connection to nature: Children’s affective attitude toward nature. Environ. Behav. 2012, 44, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batson, C.D.; Duncan, B.D.; Ackerman, P.; Buckley, T.; Birch, K. Is empathic emotion a source of altruistic motivation? J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1981, 40, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, K.P. Dispositional empathy with nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 35, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berenguer, J. The effect of empathy in pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors. Environ. Behav. 2007, 39, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Sheng, G.; She, S.; Xu, J. Impact of empathy with nature on pro-environmental behaviour. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2023, 47, 652–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.J. Rectifying share money: The concept of human relations and social practice of young people in the digital age. China Youth. Study 2025, 78–85. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.A.; Cao, Q.; Grigoriou, N. Consciousness of social face: The development and validation of a scale measuring desire to gain face versus fear of losing face. J. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 151, 129–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.R.; Ji, Q.Z.; Ye, Y.Q. Reverse intergenerational influence: Research on the factors on online consumption of middle-aged and elderly groups in urban areas. Media Observer. 2024, 99–110. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Zhou, K.Z.; Su, C. Face consciousness and risk aversion: Do they affect consumer decision-making? Psychol. Market. 2003, 20, 733–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.P.; Zhang, N.; Huang, L.Y. Attitude is important: A Study on the influencing factors of environmental protection intention in the public sphere—Discussing the moderating role of face awareness. Chin. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2024, 135–155+284. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, W.F.; Zhai, Y.Q.; Zhang, S.C. Study on policy guidance, product supply and green consumption behavior of urban and rural residents——A moderated mediation effect model. Resour. Dev. Mark. 2025, 41, 64–71. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.H.; Zhang, J.X. Impacts of sex, gender role and gender belief on undergraduates’ personality traits. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2007, 50–55. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics. Statistical tables and graphs on economic and social development: Basic information on the population of megacities and mega-cities in the Seventh National Population Census. Seek. Truth 2021, 79. [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Sebasto, N.J.; D’Costa, A. Designing a Likert-type scale to predict ERB in undergraduate students: A multistep process. J. Environ. Educ. 1995, 27, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grahn, P.; Stigsdotter, U.K. The relation between perceived sensory dimensions of urban green space and stress restoration. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 94, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.M.; Zheng, W.Y.; Kuang, Z. The difference of face measurement between reflective model and formative model and the face influence on green product preference. Chin. J. Manag. 2017, 14, 1208–1218. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.; White, M.P.; Hunt, A.; Richardson, M.; Pahl, S.; Burt, J. Nature contact, nature connectedness and associations with health, wellbeing and pro-environmental behaviours. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 68, 101389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVille, N.V.; Tomasso, L.P.; Stoddard, O.P.; Wilt, G.E.; Horton, T.H.; Wolf, K.L.; Brymer, E.; Kahn, P.H., Jr.; James, P. Time spent in nature is associated with increased pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Chen, J. Green spaces in Chinese schools enhance children’s environmental attitudes and pro-environmental behavior. Child. Youth Environ. 2021, 31, 55–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, A. The interaction between emotional connectedness to nature and leisure activities in predicting ecological worldview. Umweltpsychologie 2009, 13, 10–22. [Google Scholar]

- Klaniecki, K.; Leventon, J.; Abson, D.J. Human–nature connectedness as a ‘treatment’ for pro-environmental behavior: Making the case for spatial considerations. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 1375–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitburn, J.; Linklater, W.L.; Milfont, T.L. Exposure to urban nature and tree planting are related to pro-environmental behavior via connection to nature, the use of nature for psychological restoration, and environmental attitudes. Environ. Behav. 2019, 51, 787–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Cai, L.; Bai, B.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, J. National forest park visitors’ connectedness to nature and pro-environmental behavior: The effects of cultural ecosystem service, place and event attachment. J. Outdoor. Rec. Tour. 2023, 42, 100621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berto, R.; Barbiero, G. How the psychological benefits associated with exposure to nature can affect pro-environmental behavior. Ann. Cogn. Sci. 2017, 1, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.M.; Zheng, W.Y. An eye-tracking study on consumer preference for ecological products in the context of face culture [面子文化中消费者生态产品偏好的眼动研究]. J. Manag. World 2017, 129–140+169. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wu, J.; Wu, M.Y.; Pearce, P.L. Shaping tourists’ green behavior: The hosts’ efforts at rural Chinese B&Bs. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y. From inner needs to external actions: The impact of face consciousness on tourists’ pro-environmental behavior. Asia. Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2025, 30, 92–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.F.; Kotchen, M.J.; Moore, M.R. Internal and external influences on pro-environmental behavior: Participation in a green electricity program. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gneezy, U.; Meier, S.; Rey-Biel, P. When and why incentives (don’t) work to modify behavior. J. Econ. Perspect. 2011, 25, 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Goldstein, N.J. Social influence: Compliance and conformity. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2004, 55, 591–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, A. Is unemployment good for the environment? Resour. Energy Econ. 2016, 45, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.A.; Tian, P.; Grigoriou, N. Gain face, but lose happiness? It depends on how much money you have. Asian. J. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 14, 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.C.; Gu, J.X. The Governance of High Betrothal Price. J. Guizhou Norm. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2024, 129–139. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imamoğlu, E.O.; Kiliç, N. A social psychological comparison of the Turkish elderly residing at high or low quality institutions. J. Environ. Psychol. 1999, 19, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Fang, M.; Fu, L.; Jin, X.Y. Relative Income and Subjective Economic Status: The Collectivist Perspective. Econ. Res. J. 2019, 54, 118–133. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.A.; Wang, W. Face consciousness and conspicuous luxury consumption in China. J. Contemp. Mark. Sci. 2019, 2, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.Z. The Theoretical Analysis and Empirical Study on Face. In The Psychology of Chinese People; Yang, G., Ed.; Laurel Books Company: New Taipei City, Taiwan, China, 1998; pp. 155–238. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, B.W.; Yin, H.J. Renqing, face, and rule of law: New ideas for governance in traditional urban communities—A case study of the “moral court” in Y community of Harbin [人情、面子与法治: 传统型城市社区治理新思路——以哈尔滨市Y社区”道德法庭”为例]. Theory Mon. 2018, 161–166. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).