Abstract

The present study evaluates the quality of charcoal produced from Quercus scytophylla Liebm. in Guerrero, Mexico, using a portable metal oven, namely, the Guadiana Valley Experimental Field (CEVAG) type. A factorial design was employed to analyse the influence of wood heterogeneity (sapwood vs. heartwood) and position within the oven (low, medium, high) on the yield and physicochemical properties of the charcoal. The mean yield of the process was found to be 20.0–26.7%. The characteristics of six properties were determined: moisture content, volatile matter, ash content, fixed carbon, basic density, and calorific value. The charcoal exhibited a low moisture content (1.49–3.56%) and ash content (2.18–2.52%), meeting international standards. Volatile matter was higher in heartwood (22%). Fixed carbon (73.73–74.05%) was close to the optimal parameters of international standards. The calorific value exhibited marked variations in accordance with the position during the process of carbonisation, with elevated values observed in the lower section (6751–7508 cal g−1). The basic density of the wood was higher in the sapwood, with a maximum value of 0.57 g cm−3 observed in the upper section. A positive linear relationship was identified between the basic density and calorific value, although the coefficient of determination was small () and therefore inconclusive. The analysis showed the type of relationship that can be established between these two variables. The upper part of the kiln exhibited the optimal physicochemical properties, with the levels deemed acceptable. The utilisation of this oak for charcoal production fosters sustainable forest management and engenders direct economic benefits for rural communities. In conclusion, the research provides a viable technical model for sustainable wood energy production in forestry regions and underscores the need to evaluate other timber species with this potential.

1. Introduction

Despite the fact that Mexico’s energy supply is predominantly reliant on fossil fuels, including oil, charcoal, and natural gas, a decline in global demand is anticipated in the medium term [1]. It is therefore imperative to diversify non-fossil and renewable energy sources. In this regard, forest biomass fuel is a viable solution that complies with these principles and mitigates the adverse environmental effects caused by the use of traditional fossil fuels [2,3].

Charcoal is a forest by-product obtained by pyrolysis or carbonisation [4]. It is utilised for various purposes, including heating, cooking, and recreational activities, due to its high calorific value [5]. Charcoal is characterised by a high percentage of fixed carbon [6], a low ash content [7,8], a high density, and low moisture content [9,10,11]. Additionally, it is used in industrial applications, such as iron sintering, when it exhibits high quality [12].

Globally, 1966.2 million m3 of wood are utilised as an energy source, with the production of 54.9 million tons of charcoal being particularly significant. The countries of Africa (5.1%), the Americas (22.1%), and Asia (17.5%) are the predominant producers and consumers of this product, with Brazil, Nigeria, Ethiopia, India, and the Democratic Republic of Congo being the primary producers of charcoal [13].

The wood carbonisation process is typically conducted in earthen, brick, or metal kilns, with the specific type chosen based on the prevailing socioeconomic conditions of the site. In 2018, charcoal constituted 5.9% of Mexico’s total timber production. That same year, 64.0% of the authorised timber volume in the Mexican states of Guanajuato, Sonora, Tamaulipas, and Yucatán was allocated for charcoal production [14].

Between 2017 and 2018, Mexico recorded a 15.9% increase in the volume of wood used for charcoal production. In 2018, the volume of timber authorised for charcoal production in Mexico was 620,195 , of which 271,647 was Q. sp. During this period, 3971 was authorised for this purpose in Guerrero [14]. In 2022, charcoal production in Mexico was 38.4 million , equivalent to 2.0% of global production, but national timber production between 2020 (538,719 ) and 2021 (418,330 ) fell by 22.3%, and by 2022, Guerrero had allocated 2728.7 for charcoal production [15].

Charcoal production is linked to the social economy of small producers [16]. More than 60.0% of production is carried out on a family scale [17], using traditional methods with different species and in rudimentary earthen kilns with low-yield techniques [18,19,20]. Furthermore, there are no standardised processes to homogenise characteristics and evaluate product quality.

The quality of charcoal depends on the species, section of the tree, physical and chemical properties of the wood, types of kiln, and carbonisation process [21,22,23]. The calorific value indicates the amount of thermal energy produced by a fuel when burned and is the most important property of charcoal, in addition to the friability, moisture content, volatiles, ash, and fixed carbon, as expressed in percentage terms [10,19,24]; these properties that can be altered by transport, the storage time, and the charcoal size [25]. In this study, the calorific values of wood and charcoal were evaluated using the international standard ASTM E711-87’s criteria [26].

Some authors have shown [27,28] that wood characteristics, including basic density, have a greater influence on charcoal yield and properties than the pyrolysis process. In this regard, heartwood is expected to produce charcoal with a higher basic density and calorific value than sapwood in the species Q. scytophylla.

The objective of this study was to evaluate the quality of charcoal produced from sapwood and heartwood of Q. scytophylla in portable metal kilns installed at logging sites in the Cordón Grande forest community in the municipality of Técpan de Galeana, state of Guerrero, Mexico.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

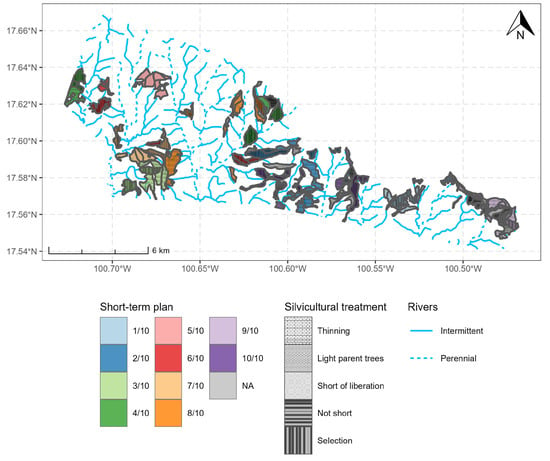

The study was conducted in stands 118 and 119 (Figure 1) of cutting area 8 for the year 2022, located at the geographic coordinates 17° 37′ 27′′ LN, 100° 37′ 12′′ LW; altitude 2046 m above sea level; physiographic province XII Sierra Madre del Sur; subprovince 66 Cordillera Costa del Sur; and topographic system 100 Sierra, according to the physiographic map scale 1:1,000,000 [29]. The soil consists of extrusive igneous rock and lithological unit intermediate andesite-tuff (geological map 1:250,000). Climate C (W2) temperate subhumid with rainfall in summer and higher humidity (climate map 1:1,000,000). Vegetation: pine forest and pine–oak forest. Hydrological region: 19 A Tecpan River Sub-basin [29].

Figure 1.

Logging plan for the Cordón Grande communal land, Técpan de Galeana, Guerrero.

2.2. Characteristics of the Kiln, Oak, and Carbonisation Process

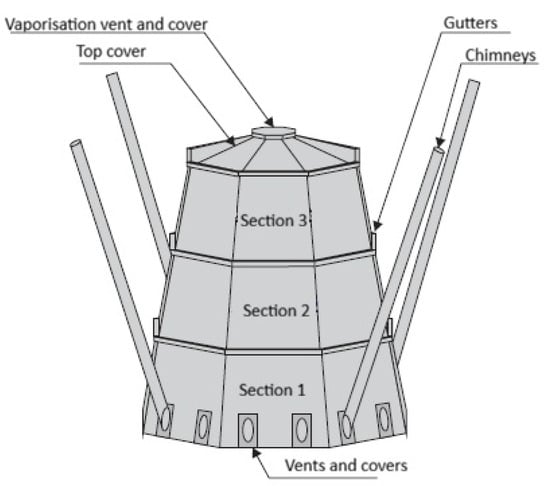

The charcoal was produced in a portable octagonal metal furnace of the Guadiana Valley Experimental Field (CEVAG) type, consisting of three octagonal sections that can be assembled one on top of the other (upper, middle, and low sections). It has sixteen vents with covers, two on each side of the octagon in section 1, as well as a top cover with ventilation for moisture vaporisation. It also has four tubes or chimneys (Figure 2). The oven has a capacity of 3000 to 3200 kg per load, which yields 500 to 600 kg of charcoal. The use of this oven represents an accessible technological improvement, greater efficiency in the pyrolysis process, better product quality, and portability for areas with limited access in the mountains of Guerrero, allowing carbonisation to be carried out on site near the biomass source, thereby reducing transportation costs. The process was in accordance with [30]. During the pyrolysis process, gases are released, and the air intake is controlled by manually operated dampers in the chimneys located at the bottom of the furnace. Total airtightness is achieved by closing the air intakes at the bottom, and the process is carried out by managing the oxygen intake to achieve controlled combustion [31]. It should be noted that, during the carbonisation process, it was not possible to record temperature readings that would allow for a thermal profile to be generated.

Figure 2.

CEVAG-type metal oven. Figure used with permission from INIFAP. Brochure for Producers No. 69. December 2020 [30].

The white oak species (Q. scytophylla) is native to western and central Mexico, from Sonora and Chihuahua to Chiapas [32], with a widespread distribution in the study area. The trees grow up to 20 m tall and 50 cm in diameter. The species is deciduous, with thick, leathery, long (20 cm) leaves that have sharp, pointed teeth along the edges.

The raw material for carbonisation came from cutting area 8, based on the 2022 Forest Management Program of the Cordón Grande ejido, with 4353.60 m3 v.t.a., authorised on 299.74 ha. The weight of the charcoal was obtained using a Rhino brand portable digital scale with a capacity of 500 kg and an accuracy of 100 g. The moisture content of the green wood was determined based on Mexican standard NOM-EE-117-1981 [33]. The average moisture contents in the sapwood and heartwood were measured in the laboratory as 43% and 26%, respectively.

2.3. Selection of Charcoal and Wood Samples

The raw material for charcoal production consisted of sections of the trunk and branches, both split and whole, and took approximately one week to produce.

The samples for analysis came from a single harvest; due to the distance, the land in the cutting area was not easily accessible.

Although [27] argued that the carbonisation process does not influence the product quality, Refs. [23,34] have shown that the position (low, medium, high) of the charcoal in the oven can influence its quality parameters. Based on this, charcoal samples were taken from the lower (0.00–0.70 m), middle (0.70–1.40 m), and upper (1.40–2.00 m) parts of the kiln for sapwood and heartwood charcoal. These were labeled and placed in brown paper and plastic bags to prevent moisture absorption during transport to the laboratory. Sapwood and heartwood samples were also collected and labeled to determine their basic density and calorific value.

2.4. Charcoal Performance in the Furnace

2.5. Moisture Content and Basic Density of Wood and Charcoal

Sapwood and heartwood samples were collected, from which cm cubes were made to obtain the moisture content and basic density using Equations (2) and (3) [36]:

The charcoal samples were obtained from the bottom, middle, and top of the kiln for sapwood and heartwood. The samples (wood and charcoal) were then placed in a Memmert VN100 drying oven at a temperature of 103 ± 2 °C until a constant weight was obtained to determine the anhydrous weights of the wood and charcoal, as specified in Mexican standard NOM-EE-117-1981 [33].

2.6. Charcoal Quality Assessment

The granulometry was determined using screens with mesh openings of 20 × 20, 50 × 50, and 100 × 100 mm, stacked from largest to smallest, using the methodology of [19]. Each screen, including the residues, was separated and weighed individually. The calculations were based on the ratio between the initial weight and the mass retained in each sieve and residue, as specified in [19]. With this data, the friability was determined using Equation (4):

The calorific value of wood and charcoal was determined using a Parr® 6200 calorimeter equipped with a Parr® 6510 manual water heating system and a Star® printer, using wood and charcoal test specimens of g, in accordance with the international standard ASTM E711-87’s criteria [37].

The percentages of moisture content, volatiles, ash, and fixed carbon in the charcoal were obtained by incinerating the samples in a Felisa muffle furnace using the criteria of ASTM D 1762-84 [37]. All tests were performed in the Wood Anatomy and Technology Laboratory of the Forest Sciences Division at the Autonomous University of Chapingo and calculated using Equations (5)–(7):

where

- : Volatile material;

- : Ash content;

- : Fixed carbon;

- : Sample mass after drying at 105 °C (g);

- : Residual mass of the sample after incineration at 950 °C (g);

- : Percentage of moisture content.

The samples (chips and charcoal) were ground in a Cole–Parmer model 4301-00 mill at 20,000 rpm for ten seconds to avoid the generation of very small particles (<0.25 mm) that can cause errors in obtaining volatiles; the ground material (wood or charcoal) was sieved to use the material retained in the 40- and 60-mesh screens. The samples were dried in a Memmert VN100 digital oven for 24 h. To obtain the moisture, volatile, and ash contents, samples of 1 ± 0.1 g of ground material were weighed on an OHAUS Scout Pro electronic scale with an accuracy of 0.01 g.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

The charcoal samples were evaluated under a factorial arrangement where the first factor was the type of wood (sapwood and heartwood) and the second factor was the position of the charcoal samples in the kiln: low, medium, and high. The study variables are shown in Table 1. For the analysis of variance, it was verified that the assumptions of normality (Shapiro–Wilk test [38]) and homogeneity of variances between treatments (Bartlett’s test [39]) were met. The Box–Cox transformation [40] was used when the variable did not meet the assumption of normality and/or homogeneity of variances. When the Box–Cox transformation did not work in the cases of the calorific value of wood and the basic density of charcoal, the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test was used (Table 1).

Table 1.

Study variables for wood and charcoal from Q. scytophylla.

According to [34], there was variability in the charcoal quality.

The Box–Cox transformation was performed using the powerTransform function in the car package [41]. The normality test was performed using the shapiro.test function from the stats package [42]. The homogeneity of the variances test was performed using the bartlett.test function from the stats package. Statistical analyses were performed using R statistical software [43].

3. Results

3.1. Oven Performance

The initial weight of the green wood averaged 3600 kg, and the final weight of the charcoal was 720 kg, corresponding to a yield of 20%. However, based on the ratio between the dry weights, the yield was calculated at 26.7%. Even so, with both calculations, the yield was comparable with that specified by the manufacturer, who states that the firewood capacity per load of 3000 to 3200 kg yields a charcoal production per batch of 500 to 600 kg [30].

3.2. Heat Capacity

There are no statistically significant differences in the calorific values of sapwood and heartwood (Table 2). In charcoal, there are significant differences in calorific value (F = 6.30, p-value < 0.001). The calorific value in the lower layer is higher than in the rest, while the middle and upper layers have a lower calorific value (Table 2).

Table 2.

Calorific value: Comparison of averages for wood and charcoal Q. scytophylla.

3.3. Basic Density

There are significant differences in the wood basic density (F = 103.72, p-value < 0.001), where it is higher in heartwood (Table 3). Sapwood charcoal in the upper layer had a higher basic density; in fact, sapwood charcoal in any of the layers has a higher density than heartwood charcoal (Table 3).

Table 3.

Basic density: comparison of averages in wood and charcoal Q. scytophylla.

3.4. Granulometry and Friability

In the granulometry, there are significant differences in the means (F = 21.08, p-value < 0.001); the granulometry is greater in the lower layer screen, while in the upper and intermediate screens, there are no significant differences (Table 4).

Table 4.

Granulometry: Comparison of means by screening.

In the granulometry, there are significant differences in the means (F = 3.63, p-value < 0.05); the granulometry in the upper and lower layers are statistically equal (Table 4). In the granulometry, there are significant differences in the means (F = 12.75, p-value < 0.001); the granulometry is greater in the middle layer of the sieve (Table 4).

Regarding friability, this is greater in the lower layer (F = 4.49, p-value < 0.05), followed by the middle and then upper layers (Table 5).

Table 5.

Friability: Comparison of means by layer.

There are significant differences in the averages of the moisture content (F = 134.97, p-value < 0.001), where the moisture content is higher in sapwood charcoal (Table 6). There are significant differences in the average volatile content (F = 5.47, p-value < 0.05), where the percentage of volatiles is higher in heartwood charcoal (Table 6). There are significant differences in the percentage of ash (F = 51.23, p-value < 0.001), where the percentage of ash is higher in heartwood charcoal (Table 6).

Table 6.

Percentages of moisture, volatiles, ash, and fixed carbon: Comparison of averages for sapwood and heartwood.

There are no significant differences in the averages of the fixed carbon percentage (F = 0.11, p-valor = 0.74) (Table 6).

3.5. Statistical Model

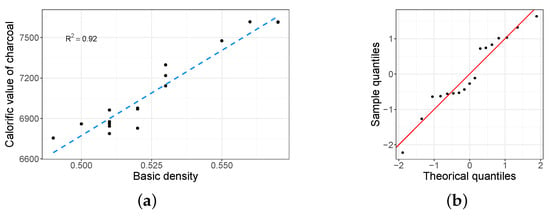

An analysis was conducted regarding the relationship between the calorific value of charcoal and the basic density of charcoal, moisture content, volatiles, ash, and fixed carbon. The results show a linear relationship between the calorific value of charcoal and its basic density (Table 7 and Figure 3a. From the adjusted simple linear regression model, we obtain an ; although the model is not conclusive, explaining only 67% of the total sample variance of the calorific value of charcoal, it does give us indications of the existence of a linear relationship between the calorific value and the basic density of charcoal.

Table 7.

Estimated simple linear model.

Figure 3.

Estimated model for the calorific value of charcoal with basic density as an explanatory variable. (a) Fitted model. (b) Q-Q plot of residuals.

The Shapiro–Wilk test shows that the residuals meet the normality assumption (W = 0.93, p-value = 0.18), which is also observed in Figure 3b.

4. Discussion

The production of charcoal in Mexico using CEVAG-type metal kilns is considered a technological innovation for charcoal production that complies with regulatory standards. These kilns were developed by INIFAP and offer significant advantages over traditional methods, including a capacity of 3000-3200 kg of firewood per load, production of 500–600 kg of charcoal, and a process lasting 28 to 36 h. Portable steel kilns, such as the RMV steel kiln [44] and Mark V [45], can be a benchmark for CEVAG, reducing the percentage of pollution from various greenhouse gases compared with traditional systems, and thus, mitigating the environmental impact.

In this study on Q. scytophylla, it was observed that depending on the position within the kiln, there are statistically significant differences in the basic density of the charcoal, with the maximum being 0.57 g cm−3 for sapwood in the upper part. This demonstrates that temperature gradients and air flow affect the quality of the charcoal produced in this kiln type [46]. On the other hand, the best quality charcoal from Quercus sideroxila Humb. & Bonpl. was obtained from the middle section of the Brazilian beehive-type kiln, with an average calorific value of 8096.88 cal g−1, a moisture content of 3.3%, 19.0% volatile material, 5.2% ash, and 72.2% fixed carbon. This quality is acceptable according to international standards (from France and Belgium) [5].

The calorific values obtained for Q. scytophylla charcoal (6751.14–7508.26 cal g−1) in this study have already been reported for this and other species in Mexico, for example, Quercus laurina (7332.57 cal g−1) and other species of oak trees (6926.534 and 8359.61 cal g−1). The variations between the different positions within the oven (lower, middle, and upper) were similar to previous research, demonstrating that temperature and air flow within the oven influence the energy properties of the resulting charcoal [47].

This study did not generate the thermal profile [48,49], which would allow the carbonisation process to be controlled and optimised, as well as provide correlations with the quality parameters (moisture content, ash, volatile material, and fixed carbon). In the context of the CEVAG system, this would constitute a complementary tool for advanced standardisation, but it is not a requirement for evaluating the performance of this technology.

The quality of the charcoal (fixed carbon) of 73.73-74.05% is close to the optimal parameters (≥75%) of international standards DIN 51749 and EN 1860-2:2023 [50,51]; therefore, we can consider the values obtained in this study to be acceptable. On the other hand, considering the moisture content (1.49–3.56%) and ash content (2.18–2.52%) results observed in this study, it is considered that national and international standards are met. However, the moisture content is below the recommended maximum limit of 8.0%, which is an indicator of the efficiency of the carbonisation process, but is comparable with that of species such as Eucalyptus (5.0–6.1%) [52].

The moisture content of the wood utilised during the carbonisation process exerts negligible influence on the majority of the variables that ensure the quality of the charcoal, with the exception of the friability value. In this particular instance, a positive correlation is observed between the moisture content of the wood and friability. Consequently, it can be concluded that the moisture content of the wood employed for carbonisation must be less than 20% [53].

The charcoal yield obtained in the portable metal furnace in this study is low (26.7% anhydrous basis), although its basic density is high (0.80 g cm−3 heartwood and 0.70 g cm−3 sapwood). This is attributed to the high moisture content (25.8%) of the Q. scytophylla wood before the carbonisation process. This situation was also found with woods of Q. laurina and Q. crassifolia [23], which, despite their high basic densities, had low yields. However, the yields observed in our research on Q. scytophylla wood are within the parameters for the carbonisation of Mexican forest species; for example, species such as Q. spp. yield 16 to 30% of the raw material weight. The results are similar when using brick kilns at 4.4 m3 ton−1 [23].

The preferred wood for wood energy in Oaxaca, Mexico, is oak (Q. spp.), which has a calorific value of 7332.57 cal g−1, a moisture content of 3.14%, 21.93% volatile matter, 3.16% ash content, and 74.91% fixed carbon. Regarding charcoal quality, the best indicators were found at the top of the kiln: lower moisture content, lower percentages of volatile matter and ash, and a higher percentage of fixed carbon. Overall, the charcoal produced in Ixtlán de Juárez, Oaxaca, complies with international standards for moisture and ash content, and the charcoal from the upper part of the kiln also meets the requirements for fixed carbon [23]. On the other hand, the dendroenergetic properties of wood from four Brazilian juvenile tropical tree species (Eucalyptus grandis Hill, Acacia mearnsii De Willd, Mimosa scarabella Benth., and Atelia glazioviana Baill) determined by [54] fluctuated between 4467 and 4545 cal g−1 of calorific value, 75.33% and 82.90% of volatile material, 1.14% and 1.75% of ash content, and 15.96% and 23.21% of fixed carbon content. In our work, higher calorific values were found in the inner layer for sapwood (7508.26 cal g−1) and heartwood (7296.28 cal g−1).

The basic densities of wood from five common tropical forest species (Alnus acuminata subsp. arguta (Schltdl.) Furlow, Arbutus xalapensis Kunth, Myrsine juergensenii (Mez) Ricketson & Pipoly, Persea longipes (Schltdl.) Meisn., and Prunus serotina Ehrh.) used for charcoal production in Oaxaca, Mexico, range from 0.37 to 0.50 g cm−3, containing 75.41% to 83.66% volatile material and 0.56% to 1.50% ash, and reach 4657.50 to 5968.76 cal g−1 of calorific value; meanwhile, the charcoal produced from these woods contains between 28.4% and 34.3% volatile material and 1.13% and 4.83% ash, with a calorific value of 7017.30 to 7669.34 cal g−1. These tests were carried out under laboratory conditions and the carbon yields ranged from 26.2% to 34.1% [35]. These researchers demonstrated that wood converted to charcoal becomes a more efficient fuel. Charcoal produced from woods with a very high basic density, such as Ebenopsis ebano (Berland.) Barneby & J.W. Grimes and Prosopis laevigata (Humb. & Bonpl. ex Willd.) M.C. Johnst. but produced in a pit-type oven [5] presented the following charcoal quality values: moisture contents of 3.6% and 3.5%; volatile matter contents of 22.8% and 24.9%; ash percentages of 2.8% and 3.2%; fixed carbon contents of 70.8% and 68.6%; and calorific values of 7222.94 and 7099.70 cal g−1, respectively. These are ranges within which the values obtained for Q. scytophylla in this research fall.

On the other hand, the estimated linear regression model suggests that the calorific value of charcoal can be explained by its basic density (R2 = 0.67); although the model is not conclusive, it allows us to identify a type of correlation between the two variables, which is essential for predicting the energy quality. This coincides with other research demonstrating the importance of basic density as an energy predictor. For example, the basic density of Q. scytophylla charcoal (0.50–0.57 g cm−3) is comparable with other species in Mexico [47,55].

The study provides a robust experimental design (factorial ) that allows for the simultaneous evaluation of multiple factors affecting charcoal quality. This methodological approach is valuable for future studies on the energy characterisation of Mexican forest species. This research validates the effectiveness of CEVAG metal kilns in producing high-quality charcoal from Mexican species. This is particularly relevant considering that Mexico allocated 620,195 m3 of wood for charcoal production in 2018, with Q. spp. accounting for 271,647 m3 [47].

The present study also demonstrates that regarding calorific value, basic density, and quality variables in wood and charcoal, sapwood yields superior results in comparison with heartwood.

5. Conclusions

Regarding the sustainable utilisation of forest resources in Mexico, charcoal emerges as a renewable alternative, underscoring the economic and environmental significance of the ecosystem services provided by this wood resource.

The present study offers results that identify opportunities for improvement in fixed carbon content to achieve optimal international standards. In particular, it is suggested that Q. scytophylla is a viable species for the production of charcoal of acceptable quality. This is relevant for sustainable forest management, especially in forest ejidos such as Cordón Grande, where charcoal production can be integrated as part of comprehensive forest utilisation strategies. The carbon yield (20.0%) in this study corresponds to the index estimated by the manufacturer of the CEVAG furnace.

This research study serves to reinforce the scientific underpinnings that support the advancement of wood energy in Mexico. In addition, it contributes to the global corpus of knowledge pertaining to the carbonisation of tropical and subtropical species. Consequently, it establishes itself as a significant point of reference for future studies in the forestry and energy sectors.

Future research arising from the analysis of the data presented includes the following: optimisation of carbonisation parameters (temperature and time); full life cycle analysis of charcoal production; and characterisation of other Mexican species with potential, such as the genus Q. spp.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, J.N.-M., L.I.B.-M. and H.Á.-P.; methodology, J.N.-M. and M.A.M.B.d.l.R.; laboratory analysis of wood, J.N.-M.; software, M.G.-M. and I.G.-B.; validation, J.L.R.-A. and M.A.M.B.d.l.R.; formal analysis, M.G.-M. and I.G.-B., investigation, J.N.-M., H.Á.-P. and J.L.R.-A., resources, J.N.-M., L.I.B.-M., H.Á.-P. and M.G.-M.; data curation, M.G.-M. and I.G.-B.; writing—original draft preparation, J.N.-M. and M.A.M.B.d.l.R.; writing—review and editing, J.N.-M., J.L.R.-A., H.Á.-P. and M.G.-M.; visualisation, M.G.-M.; supervision, M.A.M.B.d.l.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analysed in this study. These data can be found at https://github.com/arimagm/Coal-data (accessed on 16 October 2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the authorities of the Cordón Grande ejido in the municipality of Tecpan de Galeana, Gro., for the facilities provided, and to Joaquín Nuñez Medrano, who provided technical services for the same ejido.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mercure, J.; Pollitt, H.; Viñuales, J.; Edwards, N.; Holden, P.; Chewpreecha, U.; Salas, P.; Sognnaes, I.; Lam, A.; Knobloch, F. Macroeconomic impact of stranded fossil fuel assets. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 588–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baños, R.; Manzano, A.F.; Montoya, F.G.; Gil, C.; Alcayde, A.; Gómez, J. Optimization methods applied to renewable and sustainable energy: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 1753–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakata, T.; Silva, D.; Rodionov, M. Application of energy system models for designing a low-carbon society. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2011, 37, 462–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Hernández, M.; Palma-López, D.J.; Salgado-García, S.; Cancino, D.J.P.; Rincón-Ramírez, J.A.; Hidalgo-Moreno, C.I.; Cuanalo-de la Cerda, H. Carbón vegetal como mejorador de un Acrisol cultivado con caña de azúcar (Saccharum spp.). Agro. Product. 2020, 13, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Parra, A.; Foroughbakhch-Pournavab, R.; Bustamante-García, V. Calidad del carbón de Prosopis laevigata (Humb. & Bonpl. ex Willd.) MC Johnst. y Ebenopsis ebano (Berland.) Barneby & JW Grimes elaborado en horno tipo fosa. Rev. Mex. Cienc. For. 2013, 4, 62–71. [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo, A. Tecnología Para la Producción de Carbón Vegetal con Horno Metálico Tipo “Inifap-Cevag”; Technical Report Programa Nacional Forestal 2017; Comisión Nacional Forestal: Zapopan, Mexico, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- de la Vega, C. Principales Productos Forestales no Maderables de México; UACH, Departamento de Enseñanza, Investigación y Servicios de Bosques: Chihuahua, Mexico, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- García, M. Carbón de encino: Fuente de calor y energía. CONABIO. Biodiversitas 2008, 77, 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Márquez-Montesino, F.; Alcántara, T.C.; Rodríguez-Mirasol, J.; Rodríguez-Jiménez, J.; Martínez-Trinidad, T.; de la Rosa, A.; Ávalos-Rodríguez, M. Estudio del potencial energético de biomasa Pinus caribaea Morelet var. Caribaea (Pc) y Pinus tropicalis Morelet (Pt); Eucaliptus saligna Smith (Es), Eucalyptus citriodora Hook (Ec) y Eucalytus pellita F. Muell (Ep); de la provincia de Pinar del Río. Rev. Chapingo Ser. Cienc. For. Ambiente 2001, 7, 83–89. [Google Scholar]

- Kretschmann, D.; Winandy, J.; Clausen, C.; Wiemann, M.; Bergman, R.; Rowell, R.; Zerbe, J.; Beecher, J.; White, R.; Mckeever, D.; et al. Wood. In Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Oliva, N.V.; Eguigurems, J.H.; Pineda, K.J.C. Potencial dendroenergético de la especie Vernonia patens “huesillo” para la producción de biomasa con fines energéticos. TATASCÁN 2023, 31, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Yang, J.; Zhou, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Q. Characteristics of charcoal combustion and its effects on iron-ore sintering performance. Appl. Energy 2016, 161, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAOSTAT. Producción Forestal y Comercio; Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Alimentación y la Agricultura: Rome, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Secretaria de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (SEMARNAT). Anuario Estadístico de la Producción Forestal 2018; Secretaria de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (SEMARNAT): Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2021; p. 297.

- Conafor. Estado que Guarda el Sector Forestal en México 2022. Bosques para el Bienestar Social y Ambiental; Comisión Nacional Forestal: Zapopan, Mexico, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Britos, A.H.; Barchuk, A.H. Cambios en la cobertura y en el uso de la tierra en dos sitios del Chaco Árido del noroeste de Córdoba, Argentina. Agriscientia 2008, 25, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bedia, G.R.; Navall, J.M.; Sánchez Ugalde, R.; Ledesma, D.; Salim, N.; Díaz, F.; Cisneros, E.F.; Luna, M. Análisis de la demanda doméstica de leña y carbón en localidades de Santiago del Estero, Catamarca, Tucumán y Córdoba. Quebracho Rev. Cienc. For. 2018, 26, 90–99. [Google Scholar]

- Heya, M.N.; Pournavab, F.R.; Carrillo-Parra, A.; Colin-Urieta, S. Bioenergy potential of shrub from native species of northeastern Mexico. Int. J. Agric. Policy Res. 2014, 2, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Cruz, C.; Herrera, J.; Ortiz, I.A.; Ríos, J.C.; Rosales, R.; Carrillo-Parra, A. Caracterización energética del carbón vegetal producido en el Norte-Centro de México. Madera Bosques 2020, 26, e2621971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. La Transición al Carbón Vegetal: La Ecologización de la Cadena de Valor del Carbón Vegetal para Mitigar el Cambio Climático y Mejorar los Medios de Vida Locales; Technical Report; Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Alimentación y la Agricultura: Roma, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sepp, S. Multiple-Household Fuel Use-a Balanced Choice Between Firewood, Charcoal and LPG (Liquefied Petroleum Gas); GIZ: Bonn, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kattel, R. Improved charcoal production for environment and economics of blacksmiths: Evidence from Nepal. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. B 2015, 5, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, U.B.; Aquino, F.R.; García, W.S.; Juárez, W.S. Evaluación de la calidad del carbón vegetal elaborado a partir de madera de encino en horno de ladrillo. Rev. Mex. Agroecosist. 2017, 4, 127–137. [Google Scholar]

- Quezada, J.D.D.G.; Carrasco, G.A.P.; Wehenkel, C.A.; Ángel, M.; Bretado, E.; Aquino, F.R.; Parra, A.C. Caracterización energética del carbón vegetal de diez especies tropicales. Rev. Mex. Agroecosist. 2019, 6, 37–47. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Barta-Rajnai, E.; Hu, K.; Higashi, C.; Skreiberg, Ø.; Grønli, M.; Czégény, Z.; Jakab, E.; Myrvågnes, V.; Várhegyi, G.; et al. Biomass charcoal properties change during storage. Energy Procedia 2017, 105, 830–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM. Standard Test Method for Chemical Analysis of Wood Charcoal; Method published by ASTM International; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dufourny, A.; Van De Steene, L.; Humbert, G.; Guibal, D.; Martin, L.; Blin, J. Influence of pyrolysis conditions and the nature of the wood on the quality of charcoal as a reducing agent. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2019, 137, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Paula Protásio, T.; Roque Lima, M.D.; Scatolino, M.V.; Silva, A.B.; Rodrigues de Figueiredo, I.C.; Gherardi Hein, P.R.; Trugilho, P.F. Charcoal productivity and quality parameters for reliable classification of Eucalyptus clones from Brazilian energy forests. Renew. Energy 2021, 164, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INEGI. Cuaderno Estadístico Municipal. Tecpan de Galeana, Gro; Technical Report; Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática (INEGI): Aguascalientes, Mexico, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Mercado, R.; Ríos Saucedo, J.M.; Armendáriz Bejarano, J.; Avila Casillas, E.; Morales Maza, A. Tecnología para la Producción de Carbón Vegetal con el Horno Metálico Tipo CEVAG, 1st ed.; Number 1 in Folleto para Productores Núm 69; Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias (INIFAP): Campeche, Mexico, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Guardado, M.; Rodríguez, J.; Monge, L. Evaluación de la Calidad del Carbón Vegetal Producido en Hornos de Retorta y Hornos Metálicos Portátiles en El Salvador. Ph.D. Thesis, Facultad de Ingeniería y Arquitectura, Universidad Centroamericana “José Simeón Cañas”, Antiguo Cuscatlán, El Salvador, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rangel, S.R.; Carlos, E.; Zenteno, R.; de Lourdes, M.; Enríquez, A. El género Quercus (Fagaceae) en el estado de México. Ann. Mo. Bot. Gard. 2002, 89, 551–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirección General de Normas. D.G.N. NOM-EE-117-1981: Envase y Embalaje. Determinación de peso Específico Aparente en Maderas; Secretaría de Patrimonio y Fomento Industrial: Mexico City, Mexico, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante-García, V.; Carrillo-Parra, A.; González-Rodríguez, H.; Ramírez-Lozano, R.G.; Corral-Rivas, J.J.; Garza-Ocañas, F. Evaluation of a charcoal production process from forest residues of Quercus sideroxyla Humb., & Bonpl. in a Brazilian beehive kiln. Ind. Crops Prod. 2013, 42, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Aquino, F.; Ruiz-Ángel, S.; Santiago-García, W.; Fuente-Carrasco, M.E.; Sotomayor-Castellanos, J.R.; Carrillo-Parra, A. Energy characteristics of wood and charcoal of selected tree species in Mexico. Wood Res. 2019, 64, 71–82. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-Martínez, J.; Borja-de la Rosa, A.; Machuca-Velasco, R. Características tecnológicas de la madera de palo morado (Peltogyne mexicana Martínez) de Tierra Colorada, Guerrero, México. Rev. Chapingo. Ser. Cienc. For. Ambiente 2005, 11, 73–82. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM. Standard Test Method for Gross Calorific Value of Refuse-Derived Fuel by the Bomb Calorimeter; Annual Book of ASTM Standards, Method E711; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Royston, J.P. An extension of Shapiro and Wilk’s W test for normality to large samples. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. C (Appl. Stat.) 1982, 31, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, M.S. Properties of sufficiency and statistical tests. Proc. R. Soc. London. Ser. A Math. Phys. Sci. 1937, 160, 268–282. [Google Scholar]

- Box, G.E.; Cox, D.R. An analysis of transformations. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 1964, 26, 211–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, J.; Friendly, G.G.; Graves, S.; Heiberger, R.; Monette, G.; Nilsson, H.; Ripley, B.; Weisberg, S.; Fox, M.J.; Suggests, M. The car package. R Found. Stat. Comput. 2007, 1109, 1431. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, W.G. Which Stats Package? Sportscience 2016, 20, i–ii. [Google Scholar]

- Team, R.C. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tazebew, E.; Sato, S.; Addisu, S.; Bekele, E.; Alemu, A.; Belay, B. Improving traditional charcoal production system for sustainable charcoal income and environmental benefits in highlands of Ethiopia. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tazebew, E.; Sato, S.; Addisu, S.; Bekele, E.; Alemu, A.; Belay, B. Charcoal Production Systems from Smallholder Plantation implications on Carbon Emission and Sustainable Livelihood Benefits in North Western Ethiopia. Res. Sq. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Molina, J. Carbón de encino: Fuente de calor y energía. In La Riqueza de los Bosques Mexicanos: Más allá de la Madera. Experiencias de Comunidades Rurales; Semarnat: Mexico City, Mexico, 2008; Volume 77, pp. 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Aquino, F.R.; Mijangos-Ricárdez, O.F. El carbón Vegetal: Proceso de Producción, Calidad y Rendimiento. Available online: https://www.conafor.gob.mx/apoyos/docs/externos/2023/Noticiencia_Forestal_No_4_El_carbon_vegetal.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Dias, A.F.; Andrade, C.R.; Protásio, T.d.P.; Brito, J.O.; Trugilho, P.F.; Oliveira, M.P.; Dambroz, G.B.V. Thermal profile of wood species from the Brazilian semi-arid region submitted to pyrolysis. Cerne 2019, 25, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaikua, M.; Thana, P. Development of Commercial Charcoal Kilns Using Thermal Control Techniques for High-Quality Charcoal Production. J. Renew. Energy Smart Grid Technol. 2025, 20, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mencarelli, A.; Greco, R.; Balzan, S.; Grigolato, S.; Cavalli, R. Charcoal-based products combustion: Emission profiles, health exposure, and mitigation strategies. Environ. Adv. 2023, 13, 100420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, S.; Glavonjić, G. Standards and certificates for charcoal and charcoal briquettes in the function of harmonization of their quality and market development. In Proceedings of the Development Trends in Economic and Management in Wood Processing and Furniture Manufacturing, Kozina, Slovenia, 8–10 June 2011; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- Valverde, J.C.; Arias, D.; Campos, R.; Guevara, M. Caracterización física y química del carbón de tres segmentos de fuste y ramas de Eucalyptus camaldulensis Dehnh. proveniente de plantaciones dendroenergéticas. Rev. For. Mesoam. Kurú 2018, 15, 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Canal, D.; Schlicht, L.; Manzano, J.; Camacho, C.; Potti, J. Socio-ecological factors shape the opportunity for polygyny in a migratory songbird. Behav. Ecol. 2020, 31, 598–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostinho-Da Silva, D.; Otomar-Caron, B.; Sanquetta, C.R.; Behling, A.; Scmidt, D.; Bamberg, R.; Eloy, E.; Dalla-Corte, A.P. Ecuaciones para estimar el poder calorífico de la madera de cuatro especies de árboles. Rev. Chapingo. Ser. Cienc. For. Ambiente 2014, 20, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordóñez Díaz, J.A.B.; Galicia Naranjo, A.; Venegas Mancera, N.J.; Hernández Tejeda, T.; Ordóñez Díaz, M.d.J.; Dávalos-Sotelo, R. Densidad de las maderas mexicanas por tipo de vegetación con base en la clasificación de J. Rzedowski: Compilación. Madera Bosques 2015, 21, 77–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).