Abstract

In Korea, a persistent shortage of Japanese larch (Larix kaempferi) seeds and the high costs of managing seed orchards have created a significant demand for alternative reforestation methods. This pilot study, conducted over nine years, evaluated the field performance of somatic embryo-derived larch seedlings (emblings) across 14.4 hectares in nine different locations. The study addressed challenges with SE technology, such as limited genetic diversity and the inconsistent quality of seedlings due to year-round production. Despite these initial issues and other environmental interferences, the statistical analysis revealed age to be the sole significant fixed factor driving tree growth and root collar diameter (RCD) increase (p < 0.001 for both). Crucially, the growth rate (slope) for height and RCD was not statistically different between the embling and seed-derived groups (seedlings). Furthermore, the GLMM for survival confirmed that age was not a significant predictor (p > 0.35 for both types). Instead, site-specific factors were the primary drivers of overall survival and growth variation. The random effects analysis showed that site heterogeneity was substantial for height (, indicating that somatic embryo-derived larch plantlets were more sensitive to site-specific environmental conditions than seed-derived seedlings ( was 1.078 for embling survival and 0.4074 for seedling survival). We also found no significant difference in overall tree form or evidence that emblings developed dominant side branches. This research demonstrates that SE technology can produce high-quality larch emblings that are statistically equivalent to their seedling counterparts in long-term growth trajectory and RCD development. It confirms that this method offers a viable and cost-effective solution to Korea’s seed shortage without sacrificing long-term growth or survival.

1. Introduction

According to The Gymnosperm Database, the genus Larix consists of 11 species and grows mainly in the boreal and subarctic regions of the Northern Hemisphere (https://conifers.org/pi/Larix.php (accessed on 3 December 2025)). In the Far East, Japanese larch (Larix kaempferi) grows naturally in central (Honshu) and northern (Hokkaido) Japan. Due to its rapid growth, upright form, and versatile wood, it was favored as a planting species imported to Korea in 1904 [1]. Right after its introduction, this tree species became an important plantation tree in the central and northern regions of Korea. Therefore, demand for larch has surged, leading to a significant increase in planted areas. For instance, in Korea, larch accounted for 28.8% (4206 ha) of the total 14,584 ha planted in 2018 [2]. Similarly, in Japan, larch comprised about 25% of newly planted forests [3].

However, like other larch species, Japanese larch is notorious for its poor seed set. The high proportion of empty seeds, which often exceeds 70%, is as problematic as low overall seed production [4,5]. Although Korea has 250 hectares of larch seed orchards, annual seed production remains insufficient. For instance, in 2023, the entire 250-hectare area yielded a mere 497 kg of seeds. Various techniques, such as thinning, girdling, and hormone treatments, have been explored to boost seed production [6]. However, inconsistent results have hindered their widespread application.

Besides the poor seed production in larch seed orchards, maintaining large areas of seed orchards and harvesting seeds from them are becoming new challenges in terms of cost and efficiency. In Korea, where two-thirds of the land is mountainous, seed orchards are predominantly located on slopes. In rural areas where these seed orchards are operated, it has become increasingly difficult to find competent laborers capable of harvesting seeds from trees on steep slopes. Consequently, managing large seed orchard areas with scarce labor and an aging population has become prohibitively expensive. Given that this situation is unlikely to change for decades, innovative solutions are urgently needed to address this persistent challenge in larch seed supply.

Somatic embryogenesis (SE) is a promising technique for the mass production of conifer plantlets, as highlighted in recent studies [7,8,9]. Applying this technology to larch can resolve the problem of insufficient seed production by providing a stable and reliable supply of seedlings, which bypasses the need for unpredictable and labor-intensive seed harvesting. Although SE has been successfully applied to numerous 56 conifers, its deployment in larch (Larix spp.) presents unique challenges related to culture optimization, maturation, and acclimatization. Larix SE protocols are well-established, having achieved high multiplication rates and clonal fidelity, yet challenges persist in maintaining consistent embryo quality and managing the cost-efficiency required for mass production programs [10,11,12]. The successful transition from laboratory to field is also highly species- and genotype-dependent [5]. The resulting emblings must not only demonstrate field survival rates comparable to those of seedlings but also maintain desirable juvenile growth characteristics, such as straightness and apical dominance, without exhibiting common somaclonal variation issues like excessive branchiness or poor form [13]. These biological hurdles underscore the need for rigorous, long-term field validation.

Despite this potential, however, larch emblings have not been widely tested in afforestation, particularly with respect to long-term field performance data for Larix kaempferi. While smaller-scale studies exist, a key challenge is providing robust, multi-site evidence that these SE clones are not inferior to seed-derived controls. To fill this knowledge gap and provide the empirical foundation needed for integrating SE into Korea’s national reforestation program, this nine-year, large-scale, multi-site field trial was conducted. It represents one of the most extensive evaluations of Larix kaempferi emblings in Asia to date. The primary objective was to determine if larch emblings are a viable and functionally equivalent alternative to traditional seedlings by comparing the long-term survival, growth, and tree form of larch emblings and seedlings across a diverse range of Korean sites. This pilot study thus investigated the adaptation and growth of larch emblings on 14.4 hectares of plantations across nine sites in the central and northern regions of Korea, up to the age of 9.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Seedling Development and Acclimation

Larch seeds collected in late July from a superior seed orchard tree in the central region of Korea were cultured on LM medium [14] to initiate embryonic tissue. The detailed procedure and conditions for establishing somatic embryogenic masses, forming embryos, and developing into emblings have been previously described [15]. In this study, the term embling refers to a plant regenerated via somatic embryogenesis (SE), whereas the term seedlings refers exclusively to seed-derived plants. Embryogenic mass was subcultured onto a medium for somatic embryo maturation. The medium’s pH was adjusted to 5.7 and contained half-strength LM [16] with full vitamins (), 0.15 M maltose, 7.5% PEG 4000 (Polyethylene Glycol 4000), 0.8% gelrite, and 60 µM ABA. The matured somatic embryos were then germinated for three weeks on a modified version of the same medium that contained of activated charcoal but was without ABA. They were further cultured on the same basal medium, also without activated charcoal and ABA, for 6 to 8 weeks. When the germinated seedlings reached approximately 3 cm in height, they were transplanted into 105-cell pot trays (25 mm diameter × 40 mm depth) filled with a commercial soil mix. This mix was composed of 35% peat moss, 40% perlite, 24.5% vermiculite, and 0.5% humic acid. For the first four weeks, the seedlings were acclimatized in a greenhouse under 60% shade. To prevent fungal growth, a fungicide (Hymexazol, diluted 1:1000) was sprayed weekly. As the seedlings grew larger, they were transferred to a larger deep tray with 24 cells and raised for 12 to 15 weeks until they reached a height of 5 to 10 cm. They were then moved to a controlled greenhouse and cultivated until they reached a final height of 35 cm. Due to the continuous, year-round production of emblings, only seedlings potted before May were moved to nurseries, as they were suitable for field transplanting the following spring. Emblings produced after June were physiologically less mature and were stored in a cold room at 4 °C until the next spring. While necessary for mass production, this variation in physiological maturity should be considered when interpreting early growth comparisons.

2.2. Establishment of Larch Plantations Using Somatic Clone Seedlings

In 2017, we began establishing embling plantations on land cleared after logging existing forests of pines and oaks. For this study, we selected nine plantation sites in the central and northern temperate regions, which are known to be suitable for larch. To allow for a direct comparison, emblings and seedlings (which originated from the same superior seed orchard as the source material for the SE line and thus share a homologous, though not identical, genetic background) were planted adjacently at each site (Table 1). The design employed an adjacent-plot pattern, where large, distinct blocks of emblings were established immediately next to blocks of seedlings, ensuring they shared the same immediate site conditions and topography. A proliferative clone (IL-15-112, which was selected from over 50 embryogenic lines) was used to ensure consistency throughout the study. While this clone was not the fastest-growing in our preliminary, small-scale nursery trial, its moderate growth rate and high proliferation made it the most appropriate choice for producing a large number of emblings. Planting took place each spring from 2017 until 2021. Before planting, the sites were prepared with mechanical weeding, and emblings were deployed at a spacing of 1.5 m × 1.5 m. Weeding was performed twice a year (in May and August) for the first two years. A total of over 43,000 emblings were planted every spring between 2017 and 2021, placed adjacent to the planting sites of seedlings. The nine selected sites, identified by two-letter codes (GP 1, GP 2, JJ, MS, MA, PC1, PC2, HY, and GJ), are geographically and environmentally diverse (Table 1). They span a range of latitudes from approximately 34°44′34′′ N to 37°57′58′′ N and longitudes from approximately 127°24′53′′ E to 128°37′49′′ E. The altitudes also vary significantly, from a low of 364 m (HY) to a high of 985 m (PC2), representing a wide variety of environments. Table 2 details the topology and precipitation for 9 larch seedling planting sites, which exhibit diverse physical and climatic conditions. The topographic data includes slope, aspect, and soil depth. In most sites, the stand was established on a very steep slope, ranging from 27° to 40°, which is typical for most tree plantations in Korea. The soil depth was relatively shallow, ranging from 29 to 41 cm. This value represents the average of six sample points at the sites. The precipitation data, provided for the months of May and August, represents the mean values recorded from the time of planting upto 2024. This is consistent with Korea’s climate, where spring is typically dry and summer is characterized by hot, rainy conditions.

Table 1.

Location of planting sites for larch emblings.

Table 2.

Topology and precipitation of planting sites for larch somatic and seed derived seedlings (Precipitation: average precipitation since planting).

Table 2 details the topology and precipitation for 9 larch seedling planting sites, which exhibit diverse physical and climatic conditions. The topographic data includes slope, aspect, and soil depth. In most sites, the stand was established on a very steep slope, ranging from 27° to 40°, which is typical for most tree plantations in Korea. The soil depth was relatively shallow, ranging from 29 to 41 cm. This value represents the average of six sample points at the sites. The precipitation data, provided for the months of May and August, represents the mean values recorded from the time of planting up to 2024. This is consistent with Korea’s climate, where spring is typically dry and summer is characterized by hot, rainy conditions.

2.3. Survey Plots and Inventories

A total of 51 plots, each 10 m by 10 m, were established across 17 larch stands. These stands were distributed across the nine field sites described in Table 1. Specifically, one site contained only emblings, and the remaining eight sites contained both adjacent embling and seedling stands. To ensure robust spatial sampling, each stand was represented by three replicate plots. In 2024, measurements were taken for survival rates, tree height, root collar diameter, and the presence of dominant side branches. To minimize errors in site-to-site comparisons, measurements were conducted on eight dominant and subdominant trees within each plot. This approach was taken to avoid data influenced by factors such as low-quality seedlings, planting errors, damage from vines, or mechanical damage during weeding. As a result, the data for each site was obtained from trees of different ages. All soil chemical properties were determined according to standard methods employed by the National Institute of Forest Science (NIFoS), Korea. Specifically, pH was measured using a glass electrode in a 1:5 soil-water suspension. Organic matter was determined by the Walkley-Black method. Total nitrogen was analyzed using the Kjeldahl method. Available phosphate () was measured using the Lancaster method, and exchangeable cations (, Ca2+, and Mg2+) were extracted with 1N NH4OAc (pH 7.0) and analyzed using Inductively Coupled Plasma Atomic Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-AES). Tree form is a qualitative trait, not a quantitative one, so it was converted into a quantitative tree form index for statistical analysis. For this purpose, a 1-to-5 grading scale was assigned based on the degree of deviation from an ideal, high-quality tree form observed within each stand. The criteria for the index were defined by evaluating physical straightness, the number and size of side branches, and general tree health (including physical, disease and insect damage) against the best-performing tree in the stand (Grade 5). From each plot, approximately 500 g of soil were sampled from a depth of 5–10 cm below the organic layer. Soil samples were collected systematically using a soil auger. Three composite samples were taken from randomized spots within each 10 m × 10 m plot, resulting in a total of 153 samples (51 plots × 3 replicates/plot). These samples were analyzed to determine soil properties, including pH, organic matter, total nitrogen, phosphate (P2O5), and exchangeable ions (potassium, calcium, and magnesium).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The growth and survival of larch trees were analyzed using mixed-effects models to properly account for data dependence and varying precision among sites. All analyses were performed in R (version 4.5.2) using the lme4 and lmerTest packages.

2.4.1. Survival Analysis (GLMM)

Differences in survival probability between embling and seedling larch types were analyzed using a generalized linear mixed model (GLMM). Data were structured as the number of surviving and non-surviving trees (successes and failures) at each measurement point. A binomial distribution with a logit link function was used to model the log-odds of survival. Age (continuous) was included to test for overall trends, and tree type was implicitly compared. Site location was included as a random intercept, (1∣site), to quantify and control for baseline survival variability due to unmeasured site factors (site heterogeneity). Results were assessed using the random effect variance (), which quantifies site-specific sensitivity, and the p-values of the fixed effects.

2.4.2. Growth and Form Analysis (LMM/WLMM)

Differences in height, root collar diameter (RCD), and tree form index over time were analyzed using linear mixed-effects models (LMMs) to account for the non-independence of measurements nested within sites. The model included tree type (embling/seedling) and age as fixed factors. Site was included as the primary random effect, recognizing that plots were nested within sites. The basic LMM structure used was: outcome ∼ type × age + (1∣site).

2.4.3. Weighted LMM (WLMM) for Aggregated Data

Tree form index (and RCD) were analyzed using a weighted LMM (WLMM) because the dependent variable was derived from mean values () with varying precision (unequal n and SD). A weight () based on the inverse of the mean’s variance ( = /) was applied to prioritize the more reliable observations (those with larger n).

3. Results

3.1. Seedling Development and Acclimation

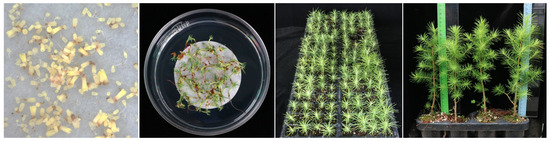

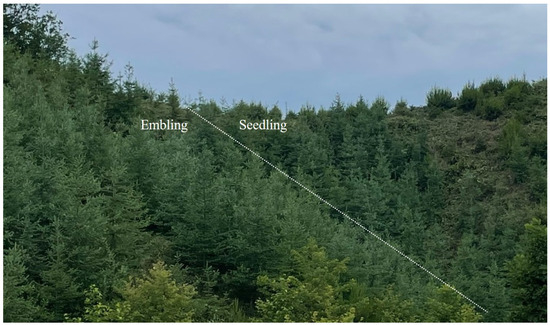

Figure 1 shows the developmental steps of somatic seedlings from somatic embryo culture. The number of somatic embryos developed per 1.8 g of somatic embryogenic mass varied with cell lines, ranging from 27 to 90 mature somatic embryos. The germinated somatic embryos grew well in acclimation conditions without problems. With more than 100,000 somatic seedlings produced, 43,000 seedlings were planted in this study. However, the quality of the somatic seedlings was inconsistent due to being transferred to pots at different times of the year. Consequently, some stocks were physiologically more mature than others, resulting in uneven conditions when compared with the seed-derived seedlings. Their growth was inferior to seed-derived trees in earlier years. However, they grew to be equivalent to seed-derived trees as they aged (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Larch somatic seedling development from somatic embryo culture. From left to right: Somatic embryos forming from a somatic embryos, somatic embryo germination, acclimation on an artificial soil mixture, and somatic seedlings before transplanting.

Figure 2.

An eight-year-old larch somatic tree stand at Muju Anseong (MA). The somatic trees caught up with seed-derived trees as they aged.

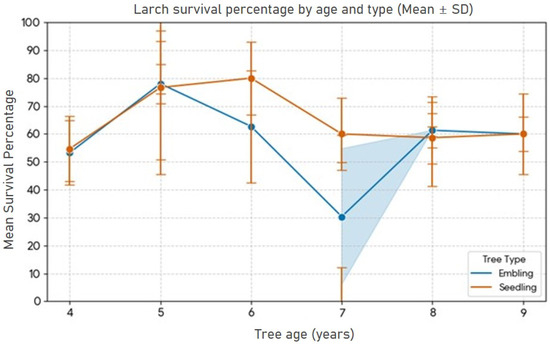

3.2. Analysis of Survival Percentage by Age and Type

Figure 3 is a line plot comparing the mean survival rate of two larch types—embling and seedling—across different tree ages (4 to 9 years). The seedling type consistently exhibits a higher and more stable mean survival rate than the embling type throughout the study period, with most points clustering between 50% and 95%. The shorter error bars for seedlings confirm their survival is less sensitive to site variability compared to emblings. Conversely, the embling data display an extreme outlier at Age 7 (dropping severely to nearly 6%). This single, low point drastically pulls the overall embling average down and confirms that the embling type is highly vulnerable to adverse site-specific conditions, resulting in high site variability. Finally, the trend lines for both types are relatively flat or slightly fluctuating across the measured ages, indicating that age is not a statistically significant linear predictor of the survival percentage once the trees are established.

Figure 3.

Larch survival percentage by age and type (Mean ± SD across sample sites).

Table 3 shows the results of the generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) analysis of embling survival odds, with site variability treated as a random effect. The model revealed that site conditions were the overwhelming and most important factor influencing survival. This is evidenced by the large site variance (1.078), which indicates substantial site-specific differences in survival probability not explained by the measured fixed effects. Site variability is significantly higher for emblings (1.078) than for seedlings (0.407), confirming greater site sensitivity. Conversely, Age was not a statistically significant predictor of survival (p = 0.502 for emblings and p = 0.359 for seedlings), and no other fixed effects (intercept or age) were found to be significant. This leads to the conclusion that most of the observed variability in survival is due to these unmeasured site factors (the large random effect) rather than a linear trend over time. Furthermore, for all sites where data for both somatic and seed-derived trees are available, the p values for the differences in survival rates are greater than 0.05, which independently confirms that the observed differences in survival rates between the two tree types at these sites are not statistically significant.

Table 3.

Comparative GLMM summary of survival parameters by tree type.

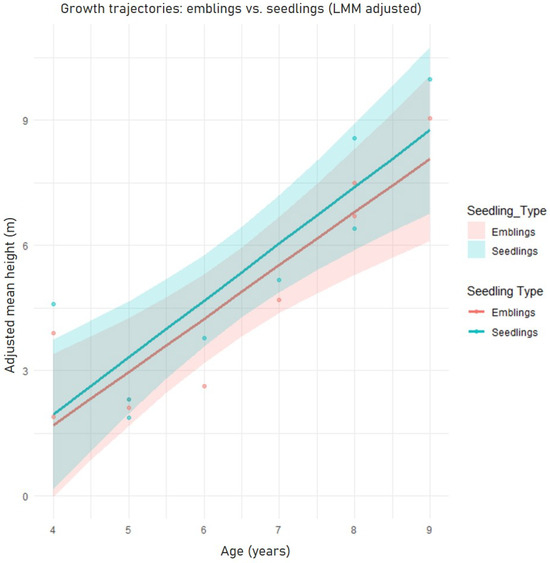

3.3. Height Growth

Figure 4 presents the average growth trajectories for both emblings and seedlings, derived from the linear mixed-effects model (LMM). The analysis reveals two distinct phases: Initial growth (ages 4–6) and long-term trajectory (ages 6–9). At the earliest measured age (age 4), the seedling trajectory (blue line) shows a slightly higher mean height than the embling trajectory (red line). Critically, the confidence bands for the two groups overlap almost completely across this period (ages 4 through 6). This visual evidence strongly supports the statistical conclusion that there is no significant difference in the initial height or early growth rate between the two larch types. Beyond age 6, the two trajectory lines remain largely parallel, indicating that both types maintain a statistically similar rate of growth (slope) throughout the long-term period. However, the seedling line consistently maintains a slightly higher adjusted mean height than the embling line. While the confidence bands show a slight tendency to narrow, they still overlap across the means, which indicates that the small numerical advantage held by the seedlings is not statistically significant throughout the entire measured period. The graph suggests that the SE technology (emblings) did not impose a long-term growth penalty, as emblings performed comparably to seedlings. While seedlings maintain a small, consistent height advantage across all measured ages, the highly similar growth trajectories confirm that the two seedling types grow at essentially the same rate.

Figure 4.

A graph generated from linear mixed-effects model (LMM) showing average growth trajectories for both emblings and seedlings. The colored areas around each line represent the 95% confidence interval (CI). Small Dots are the actual observed mean height data points (the raw data means for each age and type).

Table 4 summarizes the linear mixed-effects model (LMM) results for larch height growth. The analysis revealed that age was the sole statistically significant factor driving height increase. The model found that height reliably increased by 0.916 m per year (p < 0.001). Conversely, no other fixed effects were significant: the average height at age 0 (the intercept, = −0.1991) was not significant, indicating unreliable extrapolation. Furthermore, there was no significant difference in the initial baseline height or the subsequent annual growth rate between the seedling and embling types. Supporting the necessity of the LMM, the random effects showed that site-to-site differences were substantial, with a standard deviation of 0.8256. This large variance indicates that unmeasured site-specific factors are the main source of random variation in the trees’ baseline height.

Table 4.

Combined LMM results: Larch height growth.

3.4. Root Collar Diameter (RCD) Growth

Table 5 summarizes the linear mixed-effects model (LMM) results for larch root collar diameter (RCD) growth. As in the case of height growth, Age was the sole statistically significant factor driving RCD increase. The model found that RCD reliably increased by 1.096 cm per year (p < 0.001 for the Age Fixed Effect). Conversely, no other fixed effects were significant: the average RCD at Age 0 (the Intercept, = −1.1194) was not significant. Furthermore, there was no significant difference in the initial baseline RCD or the subsequent annual growth rate between the seedling and embling types. The random effects analysis revealed the site characteristics: the site standard deviation (0.4907) is lower than the residual standard deviation (0.8315). This indicates that the random variation attributable to unmeasured site-specific factors is lower than the unexplained tree-to-tree variability (residual error) in RCD growth.

Table 5.

Combined LMM results: Larch root collar diameter (RCD) growth.

3.5. Comparison of Height and RCD Growth

Based on Table 4 and Table 5, the growth patterns of the two parameters (height and RCD) were very similar. In both traits, growth is highly significant, and age is the most powerful predictor of tree size. Emblings show a faster annual increase in RCD ( RCD = 1.096 cm/year) than in height ( Height = 0.916 m/year). Critically, the growth rate of seedlings is statistically the same as emblings for both traits, and there is no significant difference in the initial size between the two types of seedlings in either trait. Site variability, however, was higher for height ( site was higher), indicating that the environment causes greater random variation in tree height than in RCD. Conversely, the RCD model has higher unexplained error (residual) than the height model, suggesting more noise in the RCD measurements not accounted for by the fixed or random effects.

3.6. Tree Form

Tree form scores show a highly significant improvement with age compared to the baseline (age 3) (Table 6). The average tree form score for all later ages (age 4, 5, 6, and beyond) is significantly higher (better) than the reference mean (emblings at age 3). For example, the score is 2.8 units higher at Age 4, 2.3 units higher at Age 5, and 2.6 units higher at age 6, all demonstrating a clear, positive progression of tree form over time. However, the model found no significant difference in tree form between seedlings and emblings (p = 0.091). There is only a marginal, non-significant difference in the baseline tree form score, with seedlings being slightly higher than emblings at age 3. The interaction term is not significant at age 4, meaning the difference between seedlings and emblings does not change as the trees age. Both types follow the same significant path of improvement. Site-to-site differences are minimal for tree form. The random effect indicates that site location is not a significant factor in explaining the variation in tree form scores.

Table 6.

Weighted LMM results summary: Tree form score (age as factor).

3.7. Soil Chemical Properties

Table 7 provides a comprehensive profile of soil properties across several planting sites (GP1, GP2, PC1, PC2, HY, JJ, MA, MS, and GJ). In general, the data indicates that the soil properties can vary considerably from site to site and even between adjacent plots for the two different tree types. Phosphorous (P2O5) content showed significant variation by site, ranging from a low of 10 at MA to a high of 238 at GP2. Among the properties, soil texture (the ratio of sand, silt, and clay composition) appeared to be consistent across the sites. There is no consistent pattern where somatic or seed-derived trees are always grown in more fertile soil. Instead, it shows the heterogeneity of the planting sites, which could significantly influence the growth and survival outcomes observed in the study.

Table 7.

Soil properties of somatic and seed-derived tree plantations by site (Note: E = somatic trees, S = seed-derived trees).

3.8. Comparison of Larch Growth Performance Between Two Contrasting Sites (GP2 and PC1)

Two 4-year-old embling plantations (GP2 and PC1) exhibited significantly different growth performance, as shown in Figure 4. To investigate this disparity, we compared several topographical, nutritional, and climatic factors and included seedlings in the analysis. At GP2, the emblings had a mean height of 3.90 m and the seedlings had a mean height of 4.60 m. At PC1, emblings had a mean height of 1.89 m and seedlings had a mean height of 2.30 m. Statistical analysis confirmed that both seedling types exhibited significantly poorer growth at PC1 compared to GP2 (emblings: p < 0.01; seedlings: p < 0.01). The disparity was not attributed to soil properties, which were largely similar across sites (Table 7). However, significant differences were found in topographical features and wind protection. GP2 was well-protected in a mid-slope valley, while PC1 was located near a ridge and directly exposed to wind. The ridge location of PC1 likely caused increased evaporation and greater soil water drainage, leading to water stress. Crucially, the parallel decline in performance for both emblings and seedlings confirms that site-specific environmental factors, rather than the SE technology itself, were the primary cause of the observed growth variation between GP2 and PC1.

3.9. Comparison of Seedling Growth Performance Between Two Contrasting Sites (MA and MS)

Two seedling derived larch stands (MA and MS) of the same age showed significant differences in both height (8.56 m at MS vs. 6.41 m at MA, p < 0.01) and root collar diameter (8.74 cm at MS vs. 6.38 cm at MA, p < 0.01) growth. Since the two sites were in close proximity, the climate was very similar (Table 1). Among the soil nutrients, exchangeable Ca and K were the only two factors that showed a significant difference between the two sites (Table 7). The level of exchangeable Ca in MS was over five times higher than at MA (p < 0.01). The level of exchangeable K in MS was twice as high as at MA (p < 0.05). In both cases, MA had significantly fewer nutrients than MS. No other soil nutrient factors showed any significant difference between the two sites. However, there is another notable difference between the two plantations. Although they were of the same age, the trees at MS were planted in 2017 as 1-0 seedlings, and those at MA were planted in 2018 as 2-0 seedlings. Planting younger seedlings may be advantageous for establishing trees in the field.

4. Discussion

Japanese larch (Larix kaempferi) is a valuable timber species in Korea, but a chronic shortage of seeds has created a high demand that traditional seed orchards cannot consistently meet. SE technology is a promising solution to this problem, offering a complementary approach to large-scale seedling production [13,17,18]. This pilot program was conducted to identify and address the problems associated with implementing this technology in a real-world setting. The first challenge of applying clonal technology to plantations was establishing an efficient regeneration system from an embryogenic mass. Although a dozen combinations of crosses between superior parent trees yielded a number of embryogenic mass cell lines, only six of them successfully matured and developed into usable somatic embryos. This significantly limited the genetic diversity of the emblings available for field trials [19]. Furthermore, our preliminary experiments showed that emblings from the most prolific cell lines did not always exhibit the best growth, but this line was nonetheless chosen for mass planting to meet large-scale production demands. The second challenge involved the rather small number of staff and small-scale facilities. This inevitably led to the continuous, year-round production of somatic embryos and emblings, resulting in stock with a wide range of physiological ages. This heterogeneity caused varied outcomes when seedlings were transplanted to the field, leading to inferior survival, reduced early growth, and inconsistent tree form in some individuals. To mitigate this heterogeneity, adopting both spring and fall planting may be a viable solution. A final challenge in making a proper comparison between the two seedling types was the array of interfering factors in the plantations. These included site heterogeneity, overtopping vines, competition from other rapidly growing trees, grazing by wildlife, and mechanical damage during weeding. It is common to observe that survival rates decrease with stand age in a plantation. However, the unexpectedly poor survival rate in the 4-year-old trees at GP2 was specifically attributed to overtopping vines. Nevertheless, the surviving trees at GP2, which is richer in nutrients, grew faster than those of the same age at PC1, a harsher environment with less competing vegetation. By comparing the same somatic clone at sites GP2 and PC1, a clear site factor influence on the growth of a larch plantation was identified. Although larch is a hardy species, its growth was severely limited on sites with high elevation that were exposed to wind due to water shortage [20]. Our survival analysis (GLMM, Table 3) provided strong statistical evidence for this site effect: the random effect variance ( = 1.078) for embling survival was much higher than for seedling survival ( = 0.4074). This confirms that while the survival probability for both types is not significantly correlated with age, the emblings are far more sensitive to site-specific, unmeasured environmental factors, which aligns with the observed vulnerability at sites like GP2. A comparison of two sites of the same age, MS and MA, which were established with different seedling ages, showed that initial seedling age played a role in affecting later-stage growth. A study on corsican pine also demonstrated that the field performance of container-raised seedlings was determined by initial seedling size and site factors, noting that the height advantage of taller seedlings at planting was maintained or even increased in subsequent years [21]. Our trees recovered in the third and fourth years after planting and tended to follow the same growth curve. Thus, although 2-0 larch seedlings may have an initial size advantage, they did not ultimately catch up with the 1-0 seedlings planted a year earlier. The linear mixed-effects model (LMM) results confirmed that age was the sole statistically significant driver of overall growth for both height and RCD (p < 0.001). However, the RCD growth rate for emblings (1.096 cm/year) was faster than the height growth rate (0.916 m/year). Crucially, for both height and RCD, the LMM found no significant difference in the long-term annual growth rate (slope) or initial size between the embling and seedling types. Despite these multiple challenges, emblings appeared to overcome any initial growth disparities in both height and root collar diameter during later growth stages. The data suggest that any difference in growth between the two seedling types is not statistically significant and is primarily influenced by site conditions. Similar results were reported in Norway spruce, where emblings were initially smaller than seedlings after the first and second growth periods because a large proportion of emblings were small [22]. Furthermore, a common concern among nursery workers—that emblings produce dominant side branches—was not supported by our findings. Both emblings and seedlings followed an identical and highly significant pattern of form improvement with age. The difference in form score between the two types was not statistically significant (interaction p = 0.858), which contradicts the hypothesis of inferior branching in emblings unless physical damage occurred. Ultimately, in terms of overall tree form and shape, the trees from both emblings and seedlings were indistinguishable from each other. However, for the SE technique to become more practical, the procedures for embryogenesis, germination, and acclimatization of seedlings from a diverse genetic background need to be refined. If these hurdles are overcome, we could finally realize the genetic gains from clonal plantations established with superior somatic seedlings, as shown by other researchers [13,23].

5. Conclusions

This long-term field investigation confirmed that somatic embryo-derived (SE) Larix kaempferi seedlings can achieve comparable survival and growth to conventional seed-derived seedlings under diverse site conditions in Korea. Despite early concerns about limited genetic variation and morphological irregularities, no abnormalities such as dominant lateral branching were observed, indicating that SE propagation can produce stable planting stock. The results suggest that environmental heterogeneity, rather than propagation method, is the main determinant of growth variation among sites. These findings support the technical feasibility and field reliability of SE technology for large-scale reforestation. As Korea faces increasing seed shortages and production costs, the adoption of SE-based clonal propagation offers a practical and economically viable alternative for sustainable larch seedling supply. Future work should focus on broadening the genetic base of SE lines, optimizing cost-efficient bioreactor production, and assessing long-term adaptability under changing climate conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, data analysis, and writing—original draft, C.A.; data collection and validation, H.C. and Y.-I.C.; statistical analysis, E.W.N.; field investigation, S.Y.K., K.J., Y.B.K. and J.K.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Institute of Forest Science of the Republic of Korea (grant number: FG0701-2024-01-2025).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to institutional restrictions associated with field-site information and nursery production records, but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kim, S.H.; Kim, D.H.; Jo, J.I.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, S.H.; Choi, J.K.; Kim, N.H. A comparative study on the physical and mechanical properties of Dahurian larch and Japanese larch grown in Korea. Wood Res. 2021, 66, 415–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea Forest Service. Statistical Yearbook of Forestry. 2019. Available online: https://www.forest.go.kr/ (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Matsushita, M.; Nishikawa, H.; Tamura, A.; Takahashi, M. Effects of light intensity and girdling treatments on the production of female cones in Japanese larch (Larix kaempferi (Lamb.) Carr.): Implications for the management of seed orchards. Forests 2020, 11, 1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosiński, G. Empty seed production in European larch (Larix decidua). For. Ecol. Manag. 1987, 19, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.W. Somatic Embryogenesis and Plant regeneration with Embryogenic Tissue Lines in Larix leptolepis. J. Korean For. Soc. 2010, 99, 633–637. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, W.Y.; Lee, J.S.; Lee, J.H.; Noh, E.W.; Park, E.J. Enhanced seed production and metabolic alterations in Larix leptolepi by girdling. For. Ecol. Manag. 2011, 261, 1957–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga, H.P.d.F.; Moraes, P.E.C.; Vieira, L.d.N.; Guerra, M.P. Somatic Embryogenesis in Conifers: One Clade to Rule Them All? Plants 2023, 12, 2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaj, T.; Klubicová, K.; Matusova, R.; Salaj, J. Somatic embryogenesis in selected conifer trees Pinus nigra Arn. and Abies hybrids. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Wang, J.; Hu, J.; Ling, J. Mini review: Application of the somatic embryogenesis technique in conifer species. For. Res. 2022, 2, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, K.C.; Dedicova, B.; Johansson, S.; Lelu-Walter, M.A.; Egertsdotter, U. Temporary immersion bioreactor system for propagation by somatic embryogenesis of hybrid larch (Larix × eurolepis Henry). Biotechnol. Rep. 2021, 32, e00684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelu-Walter, M.A.; Pâques, L.E. Simplified and improved somatic embryogenesis of hybrid larches (Larix × eurolepis and Larix × marschlinsii): Perspectives for breeding. Ann. For. Sci. 2009, 66, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmakov, V.; Konstantinov, Y. Somatic embryogenesis in Larix: The state of art and perspectives. Vavilov J. Genet. Breed. 2020, 24, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.S. Implementation of conifer somatic embryogenesis in clonal forestry: Technical requirements and deployment considerations. Ann. For. Sci. 2002, 59, 651–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvay, J.D.; Verma, D.C.; Johnson, M.A. Influence of a loblolly pine (Pinus taeda L.). Culture medium and its components on growth and somatic embryogenesis of the wild carrot (Daucus carota L.). Plant Cell Rep. 1985, 4, 325–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.W.; Youn, Y.; Noh, E.R.; Kim, J.C. Somatic embryogenesis and plant regeneration from immature zygotic embryos of Japanese larch (Larix leptolepis). Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 1998, 55, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aderkas, P.v.; Bonga, J.; Nagmani, R. Promotion of embryogenesis in cultured megagametophytes of Larix decidua. Can. J. For. Res. 1987, 17, 1293–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egertsdotter, U.; Ahmad, I.; Clapham, D. Automation and scale up of somatic embryogenesis for commercial plant production, with emphasis on conifers. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelu-Walter, M.A.; Teyssier, C.; Guérin, V.; Pâques, L.E. Vegetative propagation of larch species: Somatic embryogenesis improvement towards its integration in breeding programs. In Vegetative Propagation of Forest Trees; National Institute of Forest Science (NIFoS): Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2016; pp. 551–571. [Google Scholar]

- Yanchuk, A.; Bishir, J.; Russell, J.; Polsson, K. Variation in volume production through clonal deployment: Results from a simulation model to minimize risk for both a currently known and unknown future pest. Silvae Genet. 2006, 55, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyderski, M.K.; Paź, S.; Frelich, L.E.; Jagodziński, A.M. How much does climate change threaten European forest tree species distributions? Glob. Change Biol. 2018, 24, 1150–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinks, R.; Kerr, G. Establishment and early growth of different plant types of Corsican pine (Pinus nigra var. maritima) on four sites in Thetford Forest. Forestry 1999, 72, 293–304. [Google Scholar]

- Högberg, M.N.; Bååth, E.; Nordgren, A.; Arnebrant, K.; Högberg, P. Contrasting effects of nitrogen availability on plant carbon supply to mycorrhizal fungi and saprotrophs–a hypothesis based on field observations in boreal forest. New Phytol. 2003, 160, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O Neill, G.; Russell, J.; Hooge, B.; Ott, P.; Hawkins, C. Estimating gains from genetic tests of somatic emblings of interior spruce. For. Genet. 2005, 12, 57. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).