Abstract

Evapotranspiration (ET) plays a vital role in understanding water and energy cycles in forest ecosystems, particularly in tropical regions where rubber plantations are widespread. In this study, a rubber plantation system was used. By combining meteorological data from flux towers and 30 periods of Landsat-8 image data, we estimated the daily ET of a rubber plantation from 2022 to 2024 using the Surface Energy Balance System (SEBS) model. Additionally, the study employed the eddy covariance method to validate the accuracy of the daily average ET estimated by the SEBS model in different source areas, in order to explore the model’s applicability. Simultaneously, we examined the key drivers influencing ET in rubber plantations by analyzing meteorological factors and physiological growth indicators. The results indicated that the SEBS model exhibited the highest estimation accuracy (R2 = 0.90, RMSE = 0.43 mm, RE = 15.23%) for the rubber plantation ET in the region 1.5 km away from the flux tower, and the retrieval accuracy of 30 periods of ET was higher (RMSE ≤ 1 mm, RE ≤ 46.84%), indicating that the SEBS model was well-suited for estimating ET in rubber plantations. From 2022 to 2024, the daily average and monthly cumulative ET showed a unimodal distribution, with high summer and low winter values; the average monthly accumulated ET during the wet season (102.75 mm) was found to be significantly greater than that during the dry season (50.61 mm). On the daily and monthly scales, the correlation between atmospheric pressure, temperature, and ET was the most significant. These findings enhance our understanding of rubber plantation water use patterns and support the application of remote sensing models for regional water resource management, offering valuable insights for optimizing irrigation strategies and ensuring sustainable rubber production in tropical regions.

1. Introduction

Natural rubber (Hevea brasiliensis) is widely used in national defense, transportation, medical, and other fields [1,2], and it mainly comes from the latex secreted by rubber trees. In recent years, the supply of natural rubber has outstripped demand, leading to increased prices that have stimulated a swift expansion of rubber plantation areas in tropical regions [3]. However, this continuous expansion of rubber plantations has come at the expense of tropical rainforests, and the shift from tropical rainforests to a monoculture rubber plantation land use pattern has negatively impacted the local water balance and hydrological cycle [4]. In the context of global warming, water reserves are gradually decreasing, and water, as a key medium for material circulation and energy flow in the ecosystem, is a fundamental element for the normal operation and function of the ecosystem [5]. At the same time, an effective water supply is a crucial determinant for the growth and production of rubber trees [6]. Hainan Island has distinct wet and dry seasons, and water scarcity in the dry season inhibits rubber growth and production. Moreover, water consumption by rubber tree transpiration draws moisture from deeper soil layers as surface water is depleted [7]. The high-intensity ET and runoff erosion in the wet season leads to soil degradation and reduce soil fertility and productivity. Therefore, a water shortage seriously threatens the ecological and economic value of rubber plantations [8]. Consequently, understanding the interrelationships between rubber plantations and water resources, and analyzing the water balance and eco-hydrological effects are significant for water resource management in rubber plantation and for sustaining rubber production.

Evapotranspiration (ET) refers to the combined process of water evaporation and plant transpiration [9], reflecting the interaction of water and energy under atmospheric, soil, and vegetation changes [10]. Ling et al. [11] showed that the ET in the dry season of a rubber plantation is approximately 114%–140% of precipitation, and their water demand may exceed the natural precipitation supply, which has a negative impact on the local water resource balance. In addition, the annual ET of natural rubber plantations is much higher than that of other plantation types [12], and the water loss due to ET is greater in areas dominated by rubber plantations [13]. The high ET characteristics of rubber plantations deeply affect the water resource balance and soil moisture dynamics in the region. Therefore, studying ET water consumption and its spatiotemporal variation characteristics of rubber plantations is crucial for optimizing management strategies, ensuring effective utilization of water resources, and enhancing rubber production.

Currently, there are two main methods for estimating ET: field observations and model inversion [14]. Field observations include the use of evapotranspirometers, large aperture scintillometers, ET meters, and the eddy covariance method [15,16], but field observations require a long period of time, high cost, and are affected by the heterogeneity of the subsurface [17], which makes it difficult to realize the regional ET estimation and precise agricultural monitoring. Although the eddy covariance method can be used for high-precision measurement of large-scale observations, it still faces challenges in accurately delineating the range of flux source areas and identifying the specific location of flux contribution peak points in current research on measuring ET. Model inversion, on the other hand, includes the Penman–Monteith (P–M) model, Priestley–Taylor (P–T) model, energy balance model, water balance model, and others [18], which are based on environmental factors and the principle of energy balance, and use meteorological, soil, and vegetation data as input parameters to estimate ET through the model. In addition, land surface models can also predict ET. For example, Ali et al. [19] simulated a new rubber plant functional type (PFT) using the Community Land Model Version 5 (CLM5) to improve the estimation of carbon and water fluxes in rubber plantations, and the CLM5 can simulate carbon and energy fluxes similar to existing rubber models such as SVAT rubber (a soil–vegetation–atmosphere transfer model for rubber plantations) and LUCIA (the Land Use Change Impact Assessment model to simulate rubber plantations), indicating that the CLM rubber land surface model has a certain ability in estimating ET. However, SVAT-rubber developed by Kumagai et al. [20] only considered one location, so its results may be location-specific. Similarly, Yang et al. [21] used LUCIA but failed to effectively simulate the canopy development of rubber trees. On this basis, the development of remote sensing technology provides a new way to estimate ET, and satellite remote sensing combined with the energy balance model has become the most economical and accurate means to estimate ET [22]. The energy balance principle is the basis for the inversion and estimation of ET through remote sensing technologies. Models that utilize the energy balance approach for ET inversion primarily encompass SEBAL [23], SEBS [24], and TSEB models [25]. This study uses the SEBS model with clear physical concepts and high estimation accuracy. This model is a single-layer model developed on the basis of the SEBAL model. Compared with the SEBAL model, the SEBS model fully considers both dry and wet extreme conditions, reduces the uncertainty caused by complex near surface atmospheres, and effectively improves the remote sensing estimation accuracy of latent heat flux, sensible heat flux, and ET [26]. Compared with the problem of solving equations with many unknowns in the dual source model, the single-layer model can estimate ET based on basic meteorological data and remote sensing images, which is more feasible.

At present, the SEBS model is a widely used single-layer remote sensing ET model, which has achieved good research results in inverting ET in multiple regions through the SEBS model. For example, Zamani and Rahimzadegan [27] estimated the ET of Amirkabir Reservoir from 2011 to 2017 using the SEBAL and SEBS models, respectively, and the findings indicated that the SEBS model had a higher reliability of freshwater ET estimation (R2 = 0.62, RMSE = 0.93 mm). Bhattarai et al. [28] tested five models, namely the Surface Energy Balance Algorithm for Land (SEBAL), Mapping Evapotranspiration at High Resolution with Internalized Calibration (METRIC), Simplified Surface Energy Balance Index (S-SEBI), Surface Energy Balance System (SEBS), and Operational Simplified Surface Energy Balance (SSEBop), to determine the most suitable single source SEB model for use in the humid southeastern United States. The results indicated that in estimating daily ET for different land covers, SEBS is generally superior to other models (RMSE = 0.74 mm), and SSEBop was consistently the worst performing model (RMSE = 1.67 mm). Therefore, SEBS may be the best SEB model for humid areas. However, most current studies on ET focus on agricultural crops [29,30], and the studies on rubber plantations are fewer and limited to the point scale, which makes it impossible to estimate ET at the regional scale [31]. Therefore, this study applied the remote sensing model method to the estimation of the ET of rubber plantations and evaluated the applicability of the SEBS model for the ET in rubber plantations, with the aim of establishing a scientific foundation for the management of water resources and the sustainable development of rubber plantations.

The essence of ET involves the transfer of water vapor from ecosystems into the atmosphere. This process is affected by a variety of factors, including vegetation, meteorological, and soil factors. In addition, the process of ET is relatively complex, influenced by the climate, environment, and underlying surface, and has strong spatial heterogeneity [32]. Vegetation factors mainly include vegetation type, stand age, diameter at breast height (DBH), soil and plant analyzer development (SPAD), and leaf area index (LAI). SPAD is a key pigment contained in vegetation. With an increase in SPAD, vegetation will turn green, resulting in more solar radiation being intercepted by the vegetation canopy, leading to an increase in vegetation transpiration and canopy interception evaporation [33]. Testi et al. [34] demonstrated a significant positive covariance between LAI and ET in olive groves. Meteorological factors encompass air temperature (Ta), atmospheric pressure (Pre), wind speed (WS), precipitation (Prc), and net radiation (Rn) [35], and expansion of rubber plantations can cause warming, humidity, rainfall, and drought, which in turn affect the ET from rubber plantations. Among the soil factors, soil temperature, soil water content (SWC), and soil texture are also important factors affecting ET. Understanding soil characteristics can improve water use efficiency and alleviate water resource problems [36]. Sadras and Milroy [37] showed that SWC is integral to the ecological sustainability of rubber plantations.

Current research on tropical ET and its influencing factors is limited [38], with most studies focusing on traditional ET measurement methods at focal scales. Lacking research on using remote sensing technology to expand spatial scales and estimate surface scale ET in rubber plantations, the influencing factors are mainly concentrated on environmental factors, and the covariance between physiological growth indicators and ET has not been studied in depth. Therefore, this study integrated Landsat-8 satellite remote sensing data with meteorological observation data. The SEBS model was used to invert the daily ET of rubber plantations, and the accuracy of the model was verified using eddy covariance flux observation data. The applicability of the SEBS model in tropical artificial forest ecosystems was systematically evaluated. On this basis, the dynamic changes in ET in rubber plantations were analyzed in depth, with a focus on exploring the covariance of six meteorological factors and two physiological growth indicators with ET and elucidating the main driving factors with ET. This study provides important evidence for revealing the spatiotemporal variation characteristics and driving mechanisms of ET in rubber plantations. These research findings have important scientific significance for understanding the water use strategies of tropical economic forests and their response mechanisms to environmental changes, as well as optimizing water resource management in rubber plantations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

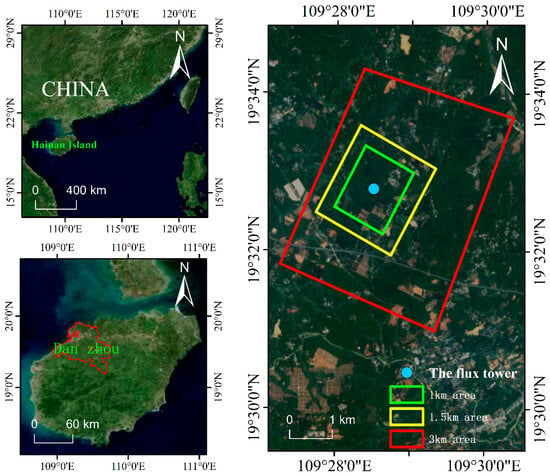

The research site is situated in the rubber core planting area of Danzhou City, Hainan Province, within the Danzhou Tropical Agricultural Resources and Ecological Environment Key Field Scientific Observation Experiment Station (19°32′47″ N, 109°28′30″ E). The average elevation is 144 m, and the relative height difference is within 10 m. This region is characterized by a typical tropical monsoon climate, exhibiting an annual average temperature ranging from 23.5 to 24.1 °C, solar radiation of 4.86 × 105 J/cm2, and 2100 h of annual sunshine. Hainan has distinct dry and wet seasons, characterized by an uneven distribution of precipitation. The rainy season extends from May to October, while the dry season occurs from November to April [39]. In the four seasons, spring is from March to May, summer is from June to August, autumn is from September to November, and winter is from December to February of the following year.

The information about the footprint of the flux tower has been detailed in the article published by Yang et al. [40]. Based on this footprint analysis, rubber plantations located with an interval of 3 km (total area 19.57 km2), 1.5 km (total area 4.62 km2), and 1 km (total area 2.08 km2) from the flux towers were selected as validation areas in order to assess the accuracy of ET estimation in various source areas of the SEBS model (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Location of research area. The upper panels provide the geographical context, showing the location of the study area (green font) within China. Select rubber plantations located (total area 19.57 km2), 1.5 km (total area 4.62 km2), and 1 km (total area 2.08 km2) away from the flux tower as validation areas for the accuracy of ET estimation in different source regions of the SEBS model.

2.2. Data

2.2.1. Landsat-8 Remote Sensing Image Data

Landsat-8 is a remote sensing satellite jointly launched by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and the United States Geological Survey (USGS), with a return period of 16 days and an altitude of 705 km [41]. The satellite remote sensing image data utilized in this research was sourced from the USGS (https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/), with strip number and line number 124, 047, and the Landsat-8 image data covering the study area were downloaded for a total of 30 periods from 2022 to 2024, respectively, with cloud content less than 30%. The remote sensing images of February and August 2022, June, September, and October 2023, and May 2024 could not be used due to high cloud content or large cloud cover in the upper layers of the study area (Table 1).

Table 1.

Statistical table of Landsat-8 data acquisition date.

2.2.2. The Flux Tower Data

The meteorological and flux data used in this study were obtained from the forest gradient flux tower observation system (Campbell Scientific, Inc., Logan, UT, USA) and the open path eddy covariance (Li-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA) automated measurement installed in the study area (19°32′47″ N, 109°28′30″ E) (Figure 2), with the height of the observation tower approximately being 50 m, and the frequency of observation being 30 min. The data used in this study mainly included the daily average air temperature, daily average air pressure, and latent heat flux. The data used in this study primarily include daily relative humidity, daily mean temperature, daily mean air pressure, and latent heat flux. The observation period spans from 1 January 2022 to 31 December 2024. The eddy covariance method directly determines the latent heat flux by identifying the covariance between vertical wind speed and water vapor flux, calculated using the following formula:

Figure 2.

Device of flux tower. The meteorological and flux data used in this study were obtained from the forest gradient flux tower observation system and open circuit vorticity system installed in the study area (19°32′47″ N, 109°28′30″ E).

The observation period was from 1 January 2022 to 31 December 2024. The eddy covariance method can directly determine the latent heat flux by determining the covariance between the vertical wind speed and water vapor flux, which is calculated using the following formula [42].

where LE is the latent heat flux (W/m2), ρ is the air density (g/m3), L is the latent heat of vaporization of water (cal/g), w’ is the pulsation value of vertical wind speed (m/s), q′ is the pulsation value of humidity, and the horizontal line is the average value over a period of time.

The ET was calculated as [43]

where T is the air temperature at the canopy height measured over a half-hour period (°C) and 0.43 is the unit conversion factor. The daily ET (mm) was obtained by summing the values of each 30 min scale within a day.

2.2.3. The Digital Elevation Data

In the present research, the DEM data from ASTER GDEM V2, which encompasses the study area, were acquired from the Geospatial Data Cloud (http://www.gscloud.cn) with UTM/WGS84 projection and a spatial resolution of 30 m. The original data were cropped with the vector data of the boundary of the study area to obtain the digital elevation model of the study area.

2.3. SEBS Model Flux Calculation

The SEBS model is a single-layer surface energy balance model that integrates surface data obtained through satellite remote sensing techniques with meteorological data from ground observations to estimate surface fluxes and deduce the actual ET of the region. The model equation [24] is as follows:

where Rn is the net radiative flux (W/m2), G0 is the soil heat flux (W/m2), H is the sensible heat flux (W/m2), λ is the coefficient of latent heat of vaporization of water, which is usually taken as 2.49 × 106 J/kg, and E is the ET rate (kg/m2·s).

The net radiative flux reflects the equilibrium state of the surface energy balance. The calculation formula [24] is as follows:

where α is the surface albedo, Rswd is the solar downward shortwave radiation (W/m2), εa is the atmospheric specific emissivity, εs is the surface specific emissivity, and σ is the Stefan–Boltzmann constant [44], which takes the value of 5.67 × 10−8 (W/m2·k4); Ta is the atmospheric temperature (K), and T0 is the surface temperature (K).

Soil heat flux refers to the amount of heat exchanged per unit area of soil per unit time during the process of exchange and transfer of energy from the surface and is the ratio of heat stored in vegetation and soil, depending on the surface characteristics and soil water content [24] with the following equation:

where ƒc is the degree of vegetation cover, Γc is the ratio of G0 to Rn under full vegetation cover (taking the value of 0.05), and Γs is the ratio of G0 to Rn in the bare ground area (taking the value of 0.315).

Sensible heat flux refers to the heat transfer through the unit area in unit time, and this heat transfer will cause the change in temperature, so that the heat exchange between the atmosphere and the subsurface in the form of turbulence, and the formula [22] is as follows:

where Cp is the constant-pressure specific heat of air, which is 1005 J/(kgˑK); θ0 and θa are the imaginary temperatures (k) at the surface and reference height, respectively; and γa is the aerodynamic impedance (s/m).

ET at the instant of satellite transit was estimated using the SEBS model. In this study, time scale expansion was performed using the evaporation ratio invariant method [45] to obtain the daily ET, that is, assuming that ET ratio is kept constant in one day, in which case the ET ratio at the instant of satellite transit is equivalent to the daily average ET ratio. The expression for the daily ET is as follows:

where ET24 is the daily ET (mm), Λ is the ET ratio, Rn24 is the daily net radiative flux (W/m2), G024 is the daily soil heat flux (W/m2), and ρw is the density of water, which is 1000 kg/m3.

The ET ratio in the study area was estimated by inversion of the SEBS model as the ratio of actual ET to the available energy. Monthly ET was estimated using the constant ratio of ET estimated by the model, and the ET was calculated by the eddy covariance method for that month, using the measured eddy covariance values to obtain the model inversion values for all days of the month, and summing up the ET estimated by the model within the month to obtain the total ET for that month. The formula [45] is as follows:

In the formula, ETs,i is the ET (mm) of day i that needs to be converted to SEBS-based model inversion; ETs,j is the ET (mm) of day j that is based on SEBS-based model inversion; ETw,i and ETw,j are the actual ET (mm) of day i and that day j, respectively, calculated using the eddy covariance method.

2.4. Indicator Measurement

This study selected six meteorological factors and two physiological growth indicators to compare and analyze the influencing factors of ET in rubber plantations at different scales. Meteorological factors include Ta, Prc, Pre, WS, SWC, Rn, while physiological growth indicators include SPAD and LAI. The acquisition of Ta, Prc, Pre, and WS in meteorological factors comes from meteorological data from flux towers. SWC, SPAD, and LAI were measured at the experimental sites. Three rubber plantation sample plots were selected in the area near the flux tower, and 15 rubber trees were selected as test sample points using the five-point method. The soil sampling time was from January to December 2024, and the determination of chlorophyll content and leaf area index was from April to December 2024. At the beginning, middle, and end of each month, growth indicators were measured and soil sampling was carried out at the sample sites, and the average of the three measurements was taken as the data for the month.

2.4.1. Measurement of Soil and Plant Analyzer Development (SPAD)

Three leaves were selected from each rubber tree in each sample point, and the measurement of each leaf was repeated three times with a LYS-B plant chlorophyll meter (KONICA MINOLTA, Tokyo, Japan), and the mean value was utilized as the value of SPAD.

2.4.2. Determination of LAI

LAI was measured using an LAI-2200C canopy analyzer (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE, USA), and the measurements were repeated four times in four directions at each sample point, and the average value was taken.

2.4.3. Measurement of Soil Water Content (SWC)

Around each sample point, surface soil samples were obtained from a depth of 0 to 5 cm, put into sealed bags labeled with a number and time, and returned to the laboratory to determine the soil mass water content by a drying method. The SWC was calculated according to the following formula [46]:

where m1 is the mass of empty aluminum box, m2 is the mass of aluminum box and soil sample, and m3 is the mass of aluminum box and soil sample after 24 h of drying.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

We used Microsoft Office Excel 2016 software to analyze meteorological data, rubber plantation ET, growth indicators, and soil water content. To determine the predictors’ influence on response variables, we employed correlation and regression analysis using SPSS version 25.0 software (p < 0.05) and used Origin 2021 software to plot the data. The accuracy of the SEBS model’s inversion was assessed through the comparison of the coefficient of determination (R2), root mean square error (RMSE), and relative error (RE). The calculation formula [47] is as follows.

The smaller the RMSE and RE, along with an R2 value approaching 1, indicates that the SEBS model has higher accuracy and precision in inverting ET from rubber plantations.

where Oi is the measured value of eddy covariance, Pi is the predicted value of SEBS model, is the mean value, and n is the number of samples.

3. Results

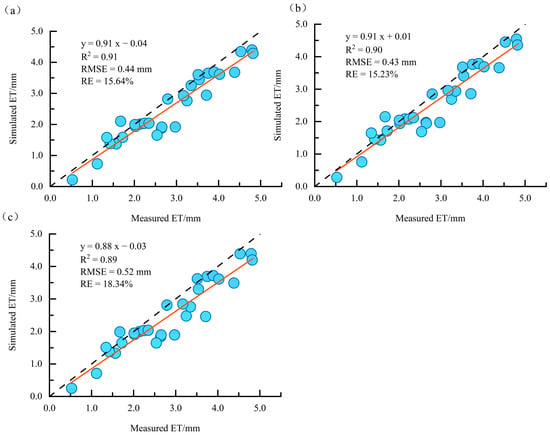

3.1. Inversion Results of Daily ET from Rubber Plantations in Different Source Areas

We used 30 Landsat-8 satellite remote sensing image data from 2022 to 2024, combined with meteorological data observed by flux towers during the corresponding period, and used the SEBS model to invert the daily ET of rubber plantations in different source areas. We used the high-precision eddy covariance method to calculate the measured daily ET of rubber plantations for model accuracy verification. As shown in Figure 3, the model-estimated ET in the 1.5 km area from the flux tower showed the best consistency with the measured ET related to vorticity (R2 = 0.90, RMSE = 0.43 mm, RE = 15.23%), moderate consistency in the 3 km area (R2 = 0.91, RMSE = 0.44 mm, RE = 15.64%), and the worst consistency for the 1 km area (R2 = 0.89, RMSE = 0.52 mm, RE = 18.34%).

Figure 3.

Comparison of simulated and measured daily ET from rubber plantations from 2022 to 2024 ((a–c) represent the comparison of simulated and measured daily ET at 3 km, 1.5 km, and 1 km from the flux tower, respectively). The blue circle represents the scatter points of “simulated daily evapotranspiration (vertical axis)” and “measured daily evapotranspiration (horizontal axis)” in different source areas. The orange solid line represents the linear regression line between simulated and measured values, while the black dashed line represents the 1:1 reference line, representing the ideal state where the simulated and measured values are completely consistent.

The SEBS model estimates of daily ET from the rubber plantation 1.5 km from the flux tower were compared with the data obtained through the eddy covariance method in 2022–2024 (Table 2). In 2022, the SEBS model had the highest accuracy in estimating ET on 28 May (RMSE = 0.01 mm, RE = 0.32%) and also had good estimation accuracy (RMSE ≤ 0.25 mm, RE ≤ 8.81%) on five periods of ET, including 28 January, 9 March, 10 April, 31 July, and 1 September, and the lowest accuracy was for 28 November (RMSE = 1.00 mm, RE = 33.74%). In 2023, the accuracy of the SEBS model for estimating ET was highest on 23 November (RMSE = 0.08 mm, RE = 4.02%) and also had good estimation accuracy for three periods of ET on 7 January, 8 February, and 27 August (RMSE ≤ 0.30 mm, RE ≤ 46.84%), and the lowest accuracy on 9 December (RMSE = 0.85 mm, RE = 33.40%). In 2024, the accuracy of the SEBS model for ET estimation was highest on 19 December (RMSE = 0.01 mm, RE = 0.66%), and was higher for seven periods, 18 January, 6 March, 7 April, 10 June, 12 July, 24 October, and 1 November (RMSE ≤ 0.23 mm, RE ≤ 9.66%), with the lowest accuracy for 14 September (RMSE = 0.46 mm, RE = 9.51%). Overall, the SEBS model had a high prediction accuracy of ET from the rubber plantations, with RMSE of 0.39, 0.43, and 0.18, and RE of 13.19%, 20.89%, and 7.26%, respectively, for 2022–2024.

Table 2.

Accuracy verification results of SEBS model for daily ET of rubber plantation at a distance of 1.5 km from the flux tower.

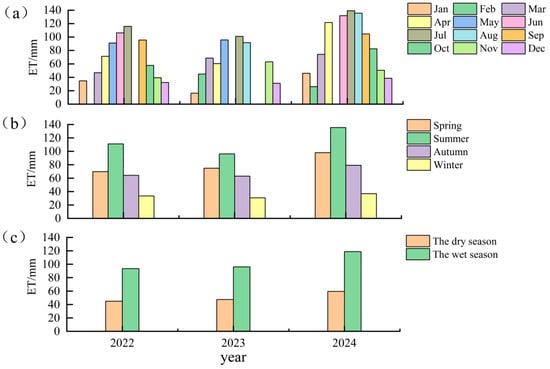

3.2. Variation Characteristics of ET in Rubber Plantation

The monthly cumulative ET of rubber plantations from 2022 to 2024 showed a single-peaked distribution (Figure 4a). In 2022, the monthly cumulative ET of rubber plantations showed a rapid increase in January-July and then showed a gradual decrease in September-December. The monthly cumulative ET of rubber plantations in 2022 increased rapidly from January to July and decreased from September to December. The smallest monthly cumulative ET was 32.23 mm in December, the largest was 116.03 mm in July, and the average monthly cumulative ET was 69.13 mm. In 2023, the monthly cumulative ET of the rubber plantations increased rapidly from January to March, from 16.29 mm to 68.70 mm, showed a low value in April, continued to increase from May to July, and gradually decreased from August to December. The minimum monthly cumulative ET was 16.29 mm in January, the maximum monthly cumulative ET was 100.94 mm in July, and the mean monthly cumulative ET was 63.63 mm. In 2024, the monthly cumulative ET of the rubber plantations decreased in February, maintained an increasing trend until July and then showed a decreasing trend from August to December, with the smallest monthly cumulative ET of 26.07 mm in February and the largest monthly cumulative ET of 139.17 mm in July.

Figure 4.

Characteristics of monthly, seasonal, and dry and wet season changes in ET from 2022 to 2024. (a–c) represents monthly cumulative ET, seasonal ET, and dry and wet season ET from 2022 to 2024, respectively. Among them, the rainy season is from May to October, and the dry season is from November to April of the following year. Spring is from March to May, summer is from June to August, autumn is from September to November, and winter is from December to February of the following year.

Overall, the monthly cumulative ET in the study area showed significant temporal variability within the year, with an overall trend of an initial rise followed by a subsequent decline, with the maximum values occurring in July. In different years, except for February and November 2023 when the monthly cumulative ET was higher than that of 2024, the monthly cumulative ET of the remaining months were higher in 2024 than in 2022 and 2023.

The seasonal variation in rubber plantations over the years varied significantly, exhibiting an overall trend of initial growth followed by a subsequent decline (Figure 4b). In summer, the rubber plantation ET mean value was the highest, 114.35 mm, with the largest summer ET mean value of 135.60 mm in 2024 and the smallest mean value of 96.30 mm in 2023, followed by spring, with the largest spring ET mean value of 97.96 mm in 2024 and the smallest mean value of 69.79 mm in 2022, followed by fall, with 79.22 mm in 2024 and 63.09 mm in 2023. The lowest mean value of ET in the rubber plantation was 33.70 mm in winter, with the highest mean value of 36.92 mm in winter in 2024 and the lowest mean value of 30.71 mm in 2023.

The average ET levels exhibited a year on year (2022 to 2024) upward trend during both the dry and wet seasons (Figure 4c). Moreover, the rubber plantation’s average ET values during the wet season were considerably greater than those during the dry season. The disparity between the wet and dry seasons reached its peak in 2024, amounting to 59.26 mm. In the dry season, the mean ET value in 2022 was the smallest, 44.90 mm, and the mean ET value in 2024 was the largest, 59.53 mm, with a difference of 14.63 mm. In the wet season, the mean ET value in 2022 was the smallest, 93.36 mm, and the mean ET value in 2024 was the largest, 118.79 mm, with a difference of 25.43 mm.

3.3. Factors Affecting ET in Rubber Plantation

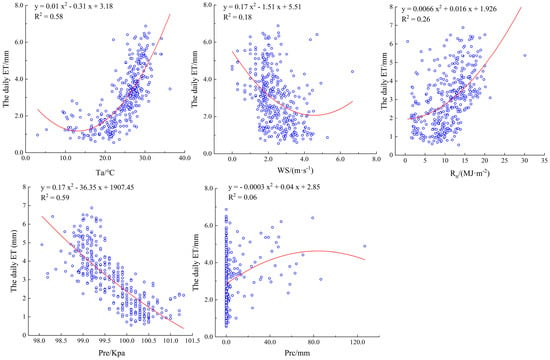

Air temperature (Ta), precipitation (Prc), wind speed (WS), atmospheric pressure (Pre), and net radiative flux (Rn) have strong correlations with daily average ET at the daily scale and are the main meteorological factors affecting rubber plantation ET (Table 3). Among them, Ta, Prc, and Rn demonstrated a highly statistically significant positive correlation with ET (p < 0.01), with corresponding correlation coefficients of 0.69, 0.24, and 0.50, respectively, and Pre and WS exhibited a highly statistically significant negative correlation with ET (p < 0.01), with correlation coefficients of −0.77 and −0.40, respectively. Among the four meteorological factors, Pre had the highest correlation with ET, with a correlation of −0.77.

Table 3.

The correlation between impact factors and ET of rubber plantation on a daily scale.

As shown in Figure 5, the average daily ET of rubber plantations decreased and then increased with increasing Ta, with a coefficient of determination of 0.58. As WS increases, the average daily ET tends to decrease and then increase, and the correlation between the two is low, with a determination coefficient of 0.18. The correlation between the daily average ET and Rn is 0.26, and the daily average ET shows an upward trend. The daily average ET gradually decreases with the increase in Pre, and the determination coefficient R2 of the two reaches 0.59. The daily average ET shows an increasing and then decreasing trend with increasing Prc, and the correlation between the two was very low, with a coefficient of determination of 0.06.

Figure 5.

Effects of impact factors on ET of rubber plantation on a daily scale. The blue circle represents the quantity of influencing factors on a daily scale.

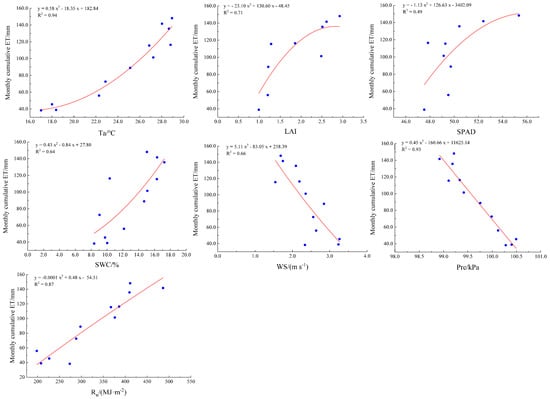

According to Table 4, Ta, Prc, WS, Pre, SWC, SPAD, and LAI are all strongly correlated with monthly cumulative ET and are the primary factors influencing ET in rubber plantations. Ta, SWC, SPAD, Rn and LAI exhibited significant positive correlations with ET (p < 0.01), with correlation coefficients exceeding 0.68. Prc showed a significant positive correlation with ET (p < 0.05), with a correlation coefficient of 0.64. Conversely, Pre and WS demonstrated significant negative correlations with ET (p < 0.01), with correlation coefficients of −0.96 and −0.81, respectively. Ta has the highest positive correlation with ET, at 0.95, Pre has the highest negative correlation with ET, at −0.96, and WS has the lowest negative correlation with ET, at −0.81. Comparing the daily scale, it can be found that Ta, Prc, Pre, Rn and WS have significantly improved correlations with ET on the monthly scale.

Table 4.

The correlation between impact factors and ET of rubber plantation on a monthly scale.

From Figure 6, the monthly cumulative ET of Ta, LAI, SPAD, SWC, and Rn are generally on the rise, with the highest determination coefficients of 0.94 and 0.87 for monthly cumulative ET and Ta and Rn, respectively. The determination coefficients of LAI, SPAD, SWC, and monthly cumulative ET are 0.71, 0.49, and 0.64, respectively. Monthly cumulative ET tended to decrease significantly with both Pre and WS, with a high correlation with Pre (R2 = 0.93), and with WS (R2 = 0.66).

Figure 6.

Effects of impact factors on ET of rubber plantation on a monthly scale. The blue dots represent the monthly quantity of influencing factors.

4. Discussion

4.1. Evaluation of the Accuracy of the SEBS Model for Inversion of ET in Rubber Plantations

This study demonstrates that using Landsat-8 satellite remote sensing combined with SEBS model to estimate the actual ET of rubber plantations in the study area from 2022 to 2024 achieved high accuracy and reliability, with an R2 ranging from 0.89 to 0.91. Baboli et al. [48] used GEE and the SEBAL algorithm combined with Landsat-8 satellite images to invert the ET of wheat, and the results were highly consistent with lysimeter data (R2 = 0.94, RMSE = 0.98 mm). Wang et al. [49] applied the SEBS model for ET inversion based on remotely sensed images and meteorological data, and the results showed that the SEBS model was highly applicable, with a coefficient of determination in the range of 0.57–0.77; Xiao et al. [50] estimated ET in the Tarim Basin using the SEBS model combined with multi-source remotely sensed data, and the results showed that the simulated ET on land and water surface had a better correlation with the observed measurements, with RMSE values of 0.92 mm and 1.63 mm, respectively. The above studies all indicate that the SEBS model combined with remote sensing information has high inversion accuracy for estimating ET, which is consistent with the results of this study.

Accuracy verification in different source regions shows that the SEBS model’s ET inversion exhibits enhanced accuracy within a 1.5-kilometer radius (R2 = 0.90, RMSE = 0.43 mm, RE = 15.23%) from the flux tower in comparison to the 3-kilometer radius (R2 = 0.91, RMSE = 0.44 mm, RE = 15.64%), which may be related to the spatial heterogeneity of the study area [51]. The spatial variability of the rubber plantation surface can significantly influence surface water and heat flux [52,53]. The meteorological data observed by the flux tower, such as temperature, humidity, and wind speed, also exhibit a specific spatial representativeness. This leads to variations in the accuracy of rubber tree transpiration inversion across different coverage areas. Furthermore, the growth characteristics of rubber trees differ across regions including tree density, canopy structure, soil properties, and moisture conditions all of which contribute to variations in transpiration values. In the area of 1.5 km from the flux tower, rubber plantations were uniformly distributed with low spatial heterogeneity, and the model fit was better, while in the area of 3 km from the flux tower, the heterogeneity increased, and the environmental and meteorological conditions were variable, which led to a decline in inversion accuracy. In general, the closer the area to the flux tower, the higher the model accuracy should be, but in this study, the SEBS model had the lowest inversion accuracy for ET in rubber plantations in the area 1 km from the flux tower (R2 = 0.89, RMSE = 0.52 mm, RE = 18.34%). Combining analysis of flux tower characteristics and remote sensing image resolution, the cause of this phenomenon may be that the area within 1 km of the flux tower is significantly influenced by the microenvironment near the tower. For example, terrain, soil moisture, and vegetation cover may exhibit high spatial heterogeneity. These local factors could cause the spatial distribution of ET to not fully match the meteorological data observed by the flux tower, making it difficult for the model to accurately capture the spatial distribution patterns of ET. The SEBS model is a single-layer remote sensing ET model, Kustas et al. [54] have shown that single-source models had significant limitations over partially vegetative surfaces. The SEBS model relies on remote sensing data, whose resolution may impact results. Within a 1 km grid cell, multiple land cover types—such as rubber plantations and bare soil—may coexist, leading to high intra-cell heterogeneity [55] and consequently reducing model accuracy. Additionally, remote sensing imagery underwent preprocessing such as FLASH atmospheric correction. However, due to the study area’s tropical location, where climate and precipitation exhibit high variability, atmospheric parameters may be inaccurate. Errors in sensor calibration, atmospheric corrections, and the specification of surface emissivity have been shown to impair methods that rely on absolute surface temperature or surface-air temperature difference to derive regional surface energy balance [56].

For 30 distinct periods of Landsat-8 image data, the seasonal variation trend of ET estimated by the SEBS model was generally consistent with that measured using the eddy covariance method throughout the year. The error remained within a reasonable range, with a determination coefficient ranging from 0.89 to 0.91. This suggests that the integration of Landsat-8 satellite remote sensing and the SEBS model demonstrates high accuracy and reliability in estimating the actual ET of rubber plantations. This performance can be attributed to the SEBS model contains a new residual impedance KB−1 parameterization that takes into account canopy structure, climate adaptation, and land cover change [57], which can accurately determine the thermal roughness length, and the SEBS model effectively distinguishes between the atmospheric boundary layer and the near-surface layer of the atmosphere, and the overall similarity theory [58] or the Mourning-Obukhov similarity theory [59] can be selected according to different scales to correct the atmospheric stability and improve the applicability of the model at different regional scales. However, compared with the estimated values of the SEBS model and the measured data of the eddy covariance method for the daily ET of rubber plantation 1.5 km from the flux tower from 2022 to 2024, there are certain errors (RMSE ≥ 0.67 mm, RE ≥ 16.07%) in the simulated and measured ET of the SEBS model on 29 June, 11 October, 28 November, and 22 December 2022, and 31 May and 9 December 2023. This may be due to the fact that the SEBS model is a single-layer energy balance model, which is suitable for quantifying the impact of the average underlying surface on the surface flux. But in practice, due to factors such as local planting patterns, growth conditions, and human activities, rubber plantations are not fully covered, which can affect the accuracy of model inversion of rubber plantation ET, the underlying surface is not homogeneous and single and is limited by the accuracy of the input data, so there is a certain error in estimating ET [60]. The eddy covariance method calculates the daily ET based on the meteorological data of a single station, while the SEBS model calculates the average daily ET value based on each cell, and considering the differences in the physical structure of the land surface, there must be an error between the two [11]. In addition, the daily average ET inverted by the model in this study is mostly lower than the measured ET, and in the long-term series analysis, the remote sensing images will be covered by a small amount of clouds, and the net radiation will drop rapidly, which makes the model inversion results smaller.

4.2. Characteristics of Spatial and Temporal Changes in ET in Rubber Plantations

The seasonal variation in ET in rubber plantations is significant, with higher values in summer (114.35 mm) than in winter (30.70 mm). As spring temperatures gradually rise, rubber trees emerge from winter dormancy, sprouting new leaves and entering their growth phase. Increased precipitation and irrigation water for vegetation during the growing season lead to heightened transpiration rates and soil moisture evaporation, causing ET to gradually increase. Summer is Hainan’s hottest season, with high temperatures accelerating water evaporation from both soil and vegetation. Simultaneously, summer is the season with the most abundant rainfall, ensuring ample soil moisture and providing a sufficient water source for ET. Furthermore, rubber trees exhibit high photosynthetic efficiency under high temperature and humidity conditions, further enhancing ET. Consequently, ET in rubber plantations reaches its maximum value during summer. As temperatures gradually decrease in autumn, vegetation enters the leaf-falling phase, growth rates slow, and ET gradually declines. Winter is the coldest season in Hainan. With shorter daylight hours and reduced precipitation, insufficient soil moisture supply leads to decreased ET. Rubber plantations enter a dormant period during this time. The low temperature in Hainan in winter and cold stress may cause significant defoliation of rubber plantations [61], vegetation transpiration slows down. Under the combined influence of the above factors, ET in rubber plantations during this period reaches its lowest value throughout the year. In addition, the average ET of rubber plantation in the wet season (102.75 mm) was significantly higher than that in the dry season (50.61 mm) in 2022–2024. During the growth and development of rubber trees, water availability is one of the primary factors limiting their normal growth [62]. The wet season is a vigorous period for the growth and development of rubber trees, with active photosynthesis, resulting in elevated surface evaporation and plant transpiration. The precipitation during the wet season significantly increases, and the ability of the root system to absorb water is enhanced, further promoting plant ET. Therefore, the ET of rubber plantations during the wet season is higher; during the dry season, rainfall fails to replenish soil moisture lost through ET in a timely manner, causing soil moisture content to decline continuously. Studies indicate that prolonged atmospheric drought or seasonal drought significantly inhibits rubber tree growth and latex production [63], leading to reduced leaf area index and decreased transpiration rates. Furthermore, during this period, rubber tree vegetation in the study area began to wither, experiencing widespread defoliation, transpiration weakened, and ET consequently diminished [64]. In the dry season, due to arid conditions and scarce precipitation, soil moisture gradually depleted and groundwater levels dropped, resulting in insufficient water supply to plant roots and thereby limiting ET. Therefore, the ET of rubber plantations during the dry season shows a low value.

4.3. Main Driving Factors Affecting ET in Rubber Plantations

Ta, Pre, WS, SWC, SPAD, LAI and Rn were the main factors affecting ET from rubber plantations. This finding is consistent with the results of Wang et al. [65], who showed that LAI, Ta, and WS were the main factors affecting ET from vegetation. Among the meteorological factors, Pre and Ta had the most significant correlation with ET on both daily and monthly scales, with Pre having a highly significant negative correlation with ET (p < 0.01), and Ta having a highly significant positive correlation with ET (p < 0.01). Ahmadpour et al. [66] also showed that Ta had a strong correlation with ET, with Ta contributing to ET by 30.9%. This occurs because at lower temperatures, the stomata of rubber trees are partially closed to minimize water loss, resulting in lower ET, and as temperatures rise, stomata gradually open, transpiration increases, and ET increases [67]. Research has shown that vegetation can reduce surface reflectance by absorbing solar radiation, thereby affecting regional ET [68], which is consistent with the results of this study. The present study showed that ET was negatively correlated with WS, which was different from the findings of Wang et al. [69] and Zhang et al. [70]. Ling et al. [71] Research has shown that there is a positive or negative correlation between rubber plantation ET and wind speed in different regions of Xishuangbanna. However, the sensitivity coefficient of wind speed to ET0 is relatively low, and Xishuangbanna is a calm area with slightly increased wind speed variation rate. Wang et al. [72] showed that ETa was negatively correlated with wind speed with a correlation coefficient of −0.76; this is the same as the results of this study. This phenomenon may occur because high wind speed will change the microclimate within the rubber plantation, may cause plant leaves to close their stomata and affect the photosynthetic characteristics, lead to a decrease in vegetation transpiration rate. The above studies showed that the results of different scholars on the influence factors of ET varied [73,74]. Both Zhou et al. [75] and Gao et al. [76] showed that precipitation is the main reason for the actual ET change. Hainan wet season precipitation is much larger than the dry season, and the ET is sensitive to the change in precipitation [77]. However, this is inconsistent with the determination coefficient of 0.06 for ET and precipitation on a daily scale in this study. At the daily scale, rainfall intercept a portion of evaporation [78], a portion of precipitation is intercepted by the canopy of rubber plantations, accumulating on leaf surfaces. Daily ET typically remains low during rainfall. Within 2–3 days post-rain, soil moisture gradually infiltrates downward and redistributes, increasing soil humidity. Concurrently, rising air temperatures stimulate soil evaporation and vegetation transpiration, causing ET to gradually increase. This dynamic produces a distinct lagged peak, explaining the lower correlation between ET and precipitation at the daily scale. Among the vegetation physiological growth indicators, LAI and ET were significantly positively correlated; this finding was consistent with the results obtained by Gong et al. [79]. As a pivotal variable in the exchange of matter and energy between the biosphere and the atmosphere [80], LAI has obvious physical correlation with ET, that is, an increase in leaf area results in an enhancement of total surface area and stomatal conductance [81] and more water vapor can be diffused from the leaves in the form of transpiration, so the ET of vegetation increases.

5. Conclusions

Our research indicates that the SEBS model has good accuracy in estimating the daily ET of rubber plantations in different source regions. Specifically, the model inversion results are consistent with the measured data in terms of seasonal variation trends, and the ET in summer and rainy season is higher than that in winter and dry season, respectively. These results indicate that hydrothermal conditions have a significant impact on ET. In addition, among the factors affecting ET, Pre and Ta have the highest correlation with ET, indicating that ET in rubber plantations in tropical regions has different feedback and key factors on climate change. Collectively, our findings provide a scientific basis for water resource management in rubber plantations based on remote sensing technology, which may be crucial for adaptive management strategies of rubber plantation ecosystems in response to climate change.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.W. and W.L.; methodology, J.W. and W.L.; validation, J.W., W.L., Q.C., H.Y., J.Z., Z.W. and C.Y.; formal analysis, J.W. and W.L.; investigation, J.W., W.L., H.Y., J.Z., Z.W. and C.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, J.W. and W.L.; writing—review and editing, Q.C. and B.W.; supervision, B.W.; project administration, B.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was jointly funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 42167011), Hainan Provincial Science and Technology Special Fund (No. ZDYF2025XDNY112, No. ZDYF2024XDNY196), Fundamental Research Funds for Rubber Research Institute, CATAS (1630022024020) and Natural Science Foundation of Hainan Province (No. 323MS076).

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ET | Evapotranspiration |

| SEBS | Surface Energy Balance System |

| P–M | Penman–Monteith |

| P–T | Priestley–Taylor |

| PFT | Plant Functional Type |

| CLM5 | Community Land Model Version 5 |

| SVAT | Soil–Vegetation–Atmosphere Transfer |

| LUCIA | Land Use Change Impact Assessment |

| SEBAL | Surface Energy Balance Algorithm for Land |

| METRIC | Mapping Evapotranspiration at high Resolution with Internalized Calibration |

| S-SEBI | Simplified Surface Energy Balance Index |

| SSEBop | Operational Simplified Surface Energy Balance |

| DBH | Diameter at breast height |

| SPAD | Soil and plant analyzer development |

| LAI | Leaf area index |

| Ta | Air temperature |

| Pre | Atmospheric pressure |

| WS | Wind speed |

| Prc | Precipitation |

| Rn | Net radiation |

| SWC | Soil water content |

| NASA | National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

| USGS | United States Geological Survey |

| R2 | Coefficient of determination |

| RMSE | Root mean square error |

| RE | Relative error |

References

- Oleinik, G.; Soares, L.C.; Benvegnú, D.M.; Lima, F.O.; Rodrigues, P.R.P.; Gallina, A.L. Rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis) seed shell extracts as a promising green antioxidant alternative to increase biodiesel oxidation stability. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 190, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Xiao, J.F.; Bai, R.; Wang, J.; Wu, L.; Gao, W.L.; Li, W.; Chen, M.; Li, Q.F. Preseason sunshine duration determines the start of growing season of natural rubber forests. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2023, 124, 103513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Kou, W.; Chen, B.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Yung, T.; Ma, J.; Sun, R.; Li, Y. Spatio-temporal changes of rubber plantations in Hainan Island over the past 30 years. J. Nanjing For. Univ. 2023, 47, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Fu, R.; Cheng, S.; Qiao, D.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Dai, L. Effects of the conversion of natural tropical rainforest to monoculture rubber plantations on soil hydrological processes. J. Plant Ecol. 2024, 17, rtae021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlon, B.R.; Fakhreddine, S.; Rateb, A.; de Graaf, I.; Famiglietti, J.; Gleeson, T.; Grafton, R.Q.; Jobbagy, E.; Kebede, S.; Kolusu, S.R.; et al. Global water resources and the role of groundwater in a resilient water future. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, P.; Gohet, E.; Nouvellon, Y.; Lacote, R.; Gay, F.; Do, F.C. Rubber tree ecophysiology and climate change. What do we know? In Proceedings of the Workshop on Natural Rubber Systems and Climate Change, CGIAR; CIFOR, Online, 23–25 June 2021; Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research. 2021. Available online: https://hal.science/hal-05177285v1 (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Ling, Z.; Shi, Z.T.; Gu, S.X.; Peng, H.Y.; Feng, G.J.; Huo, H. Energy balance and evapotranspiration characteristics of rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis) plantations in Xishuangbanna, Southwest of China. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2022, 20, 11–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiarelli, D.D.; Rosa, L.; Rulli, M.C.; D’Odorico, P. The water-land-food nexus of natural rubber production. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 1739–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhou, Z.; Li, H.; Wei, Y.; Huang, J.; Liang, H.; Wang, W. Evaluation of the performance of three types of two-source evapotranspiration models in urban woodland areas. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Z.; Shi, Z.; Xia, T.; Gu, S.; Liang, J.; Xu, C.Y. Short-term evapotranspiration forecasting of rubber (Hevea brasiliensis) plantations in Xishuangbanna, Southwest China. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Z.; Shi, Z.; Gu, S.; He, G.; Liu, X.; Wang, T.; Zhu, W.; Gao, L. Estimation of applicability of soil model for rubber (Hevea brasiliensis) plantations in xishuangbanna, southwest China. Water 2022, 14, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giambelluca, T.W.; Mudd, R.G.; Liu, W.; Ziegler, A.D.; Kobayashi, N.; Kumagai, T.; Miyazawa, Y.; Lim, T.K.; Huang, M.; Fox, J.; et al. Evapotranspiration of rubber (Hevea brasiliensis) cultivated at two plantation sites in Southeast Asia. Water Resour. Res. 2016, 52, 660–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guardiola-Claramonte, M.; Troch, P.A.; Ziegler, A.D.; Giambelluca, T.W.; Durcik, M.; Vogler, J.B.; Nullet, M.A. Hydrologic effects of the expansion of rubber (Hevea brasiliensis) in a tropical catchment. Ecohydrology 2010, 3, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshnood, S.; Lotfata, A.; Mombeni, M.; Daneshi, A.; Verrelst, J.; Ghorbani, K. A spatial and temporal correlation between remotely sensing evapotranspiration with land use and land cover. Water 2023, 15, 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruyama, T.; Ito, K.; Takimoto, H. Abnormal data rejection range in the Bowen ratio and inverse analysis methods for estimating evapotranspiration. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2019, 269, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Lakshmi, V.; Wang, D.; Lin, P.; Pan, M.; Cai, X.; Wood, E.F.; Zeng, Z. The reliability of global remote sensing evapotranspiration products over amazon. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.G.; Pereira, L.S.; Howell, T.A.; Jensen, M.E. Evapotranspiration information reporting: I. Factors governing measurement accuracy. Agric. Water Manag. 2010, 98, 899–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Shi, L.; Lin, G.; Lin, L. Comparison of physical-based, data-driven and hybrid modeling approaches for evapotranspiration estimation. J. Hydrol. 2021, 601, 126592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.A.; Fan, Y.; Corre, M.D.; Kotowska, M.M.; Preuss-Hassler, E.; Cahyo, A.N.; Moyano, F.E.; Stiegler, C.; Röll, A.; Meijide, A.; et al. Implementing a New Rubber Plant Functional Type in the Community Land Model (CLM5) Improves Accuracy of Carbon and Water Flux Estimation. Land 2022, 11, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumagai, T.; Mudd, R.G.; Miyazawa, Y.; Liu, W.; Giambelluca, T.W.; Kobayashi, N.; Lim, T.K.; Jomura, M.; Matsumoto, K.; Huang, M.; et al. Simulation of canopy CO2/H2O fluxes for a rubber (Hevea brasiliensis) plantation in central Cambodia: The effect of the regular spacing of planted trees. Ecol. Model 2013, 265, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Blagodatsky, S.; Marohn, C.; Liu, H.; Golbon, R.; Xu, J.; Cadisch, G. Climbing the mountain fast but smart: Modelling rubber tree growth and latex yield under climate change. For. Ecol. Manag. 2019, 439, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.L.; Tang, R.; Wan, Z.; Bi, Y.; Zhou, C.; Tang, B.; Yan, G.; Zhang, X. A review of current methodologies for regional evapotranspiration estimation from remotely sensed data. Sensors 2009, 9, 3801–3853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastiaanssen, W.G.M.; Menenti, M.; Feddes, R.A.; Holtslag, A.A.M. A remote sensing surface energy balance algorithm for land (SEBAL). 1. Formulation. J. Hydrol. 1998, 212, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z. The Surface Energy Balance System (SEBS) for estimation of turbulent heat fluxes. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2002, 6, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, J.M.; Kustas, W.P.; Humes, K.S. Source approach for estimating soil and vegetation energy fluxes in observations of directional radiometric surface temperature. Agric. For. Meteorol. 1995, 77, 263–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.M.; Liu, J. Evolution of evapotranspiration models using thermal and shortwave remote sensing data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 237, 111594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani Losgedaragh, S.; Rahimzadegan, M. Evaluation of SEBS, SEBAL, and METRIC models in estimation of the evaporation from the freshwater lakes (Case study. Amirkabir dam, Iran). J. Hydrol. 2018, 561, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, N.; Shaw, S.B.; Quackenbush, L.J.; Im, J.; Niraula, R. Evaluating five remote sensing based single-source surface energy balance models for estimating daily evapotranspiration in a humid subtropical climate. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2016, 49, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoratipour, E.; Mohammadi, A.S.; Zoratipour, A. Evaluation of SEBS and SEBAL algorithms for estimating wheat evapotranspiration (case study: Central areas of Khuzestan province). Appl. Water Sci. 2023, 13, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, T.F.; Pavek, M.J.; Holden, Z.J.; Garza, R. Evaluating potato evapotranspiration and crop coefficients in the Columbia Basin of Washington state. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 286, 108371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, P. Comparison of remote sensing evapotranspiration models: Consistency, merits, and pitfalls. J. Hydrol. 2023, 617, 128856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, K.; Liaqat, U.W.; Choi, M. Dual-model approaches for evapotranspiration analyses over homo-and heterogeneous land surface conditions. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2014, 197, 169–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Kong, D.; Zhang, X.; Tian, J.; Li, C. Impacts of vegetation changes on global evapotranspiration in the period 2003–2017. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2021, 76, 584–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testi, L.; Villalobos, F.J.; Orgaz, F. Evapotranspiration of a young irrigated olive orchard in southern Spain. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2004, 121, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, R.G.; Pereira, L.S.; Raes, D.; Smith, M. Crop evapotranspiration-Guidelines for computing crop water requirements-FAO Irrigation and drainage paper 56. Fao Rome 1998, 300, D05109. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, V.; Chaplot, B.; Omar, P.J.; Mishra, S.; Md. Azamathulla, H. Experimental study on infiltration pattern: Opportunities for sustainable management in the Northern region of India. Water Sci. Technol. 2021, 84, 2675–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadras, V.O.; Milroy, S.P. Soil-water thresholds for the responses of leaf expansion and gas exchange: A review. Field Crops Res. 1996, 47, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pour, S.H.; Wahab, A.K.A.; Shahid, S.; Ismail, Z.B. Changes in reference evapotranspiration and its driving factors in peninsular Malaysia. Atmos. Res. 2020, 246, 105096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Xiong, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Zhao, J.; Nie, T.; Wu, L.; Sun, Z. A Study on the Vulnerability of the Gross Primary Production of Rubber Plantations to Regional Short-Term Flash Drought over Hainan Island. Forests 2022, 13, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Wu, Z.; Yang, C.; Song, B.; Liu, J.; Chen, B.; Lan, G.; Sun, R.; Zhang, J. Responses of carbon exchange characteristics to meteorological factors, phenology, and extreme events in a rubber plantation of Danzhou, Hainan: Evidence based on multi-year data. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 11, 1194147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, D.P.; Wulder, M.A.; Loveland, T.R.; Woodcock, C.E.; Allen, R.G.; Anderson, M.C.; Helder, D.; Irons, J.R.; Johnson, D.M.; Kennedy, R.; et al. Landsat-8: Science and product vision for terrestrial global change research. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 145, 154–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclerc, M.Y.; Foken, T. Footprints in Micrometeorology and Ecology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yu, S.; Zhang, H.; Li, F.; Liang, C.; Wang, Z. Estimating the actual evapotranspiration using remote sensing and SEBAL model in an arid environment of Northwest China. Water 2023, 15, 1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blevin, W.R.; Brown, W.J. A precise measurement of the Stefan-Boltzmann constant. Metrologia 1971, 7, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Song, K.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, B.; Liu, D. Evapotranspiration estimation based on MODIS products and surface energy balance algorithms for land (SEBAL) model in Sanjiang Plain, Northeast China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2013, 23, 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, W.H. Water content. In Methods of Soil Analysis: Part 1 Physical and Mineralogical Methods; American Society of Agronomy, Inc.: Madison, WI, USA, 1986; Volume 5, pp. 493–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicco, D.; Warrens, M.J.; Jurman, G. The coefficient of determination R-squared is more informative than SMAPE, MAE, MAPE, MSE and RMSE in regression analysis evaluation. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2021, 7, e623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baboli, N.; Ghamarnia, H.; Hafezparast Mavaddat, M. Estimating wheat evapotranspiration through remote sensing utilizing GeeSEBAL and comparing with lysimetric data. Appl. Water Sci. 2024, 14, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yang, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Kong, J.; Yang, Y. Estimation of evapotranspiration and its relationship with environmental factors in Jinghe River Basin. J. Appl. Remote Sens. 2021, 15, 034518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Sun, F.; Wang, T.; Wang, H. Estimation and validation of high-resolution evapotranspiration products for an arid river basin using multi-source remote sensing data. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 298, 108864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.M.; Xu, Z.W.; Wang, W.Z.; Jia, Z.Z.; Zhu, M.J.; Bai, J.; Wang, J.M. A comparison of eddy-covariance and large aperture scintillometer measurements with respect to the energy balance closure problem. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2011, 15, 1291–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelmann, C.; Bernhofer, C. Exploring eddy-covariance measurements using a spatial approach: The eddy matrix. Bound.-Layer Meteorol. 2016, 161, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Li, X.; Xu, Z.; Che, T.; Xiao, Q.; Ma, M.; Liu, Q.; Jin, R.; Guo, J.; Wang, L.; et al. The Heihe Integrated Observatory Network: A basin-scale land surface processes observatory in China. Vadose Zone J. 2018, 17, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kustas, W.P.; Daughtry, C.S.T. Estimation of the soil heat flux/net radiation ratio from spectral data. Agric. For. Meteorol. 1990, 49, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Chen, J.; Chen, J.; Zhan, W.; Wang, C.; Ma, W.; Yao, X.; Zhou, S.; Zhu, K.; Sun, R. Enhanced observations from an optimized soil-canopy-photosynthesis and energy flux model revealed evapotranspiration-shading cooling dynamics of urban vegetation during extreme heat. Remote Sens. Environ. 2024, 305, 114098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mecikalski, J.R.; Diak, G.R.; Anderson, M.C.; Norman, J.M. Estimating fluxes on continental scales using remotely sensed data in an atmospheric-land exchange model. J. Appl. Meteorol. 1999, 38, 1352–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brutsaert, W. Aspects of bulk atmospheric boundary layer similarity under free-convective conditions. Rev. Geophys. 1999, 37, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foken, T. 50 years of the Monin-Obukhov similarity theory. Bound.-Layer Meteorol. 2006, 119, 431–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, J.B.; Whittaker, R.J.; Malhi, Y. ET come home: Potential evapotranspiration in geographical ecology. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2011, 20, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhao, W. Satellite-based actual evapotranspiration estimation in the middle reach of the Heihe River Basin using the SEBAL method. Hydrol. Process. 2010, 24, 3337–3344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, W.; Dong, Y.; Fei, X.; Song, Q.; Sha, L.; Wang, S.; Grace, J. Pattern and driving factor of intense defoliation of rubber plantations in SW China. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 94, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, M.K.V. The water relations of rubber (Hevea brasiliensis): A review. Exp. Agric. 2012, 48, 176–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, F.; Zou, Z.; Cai, X.; Wang, J.; Rookes, J.; Lin, W.; Cahill, D.; Kong, L. Regulation of HbPIP2; 3, a latex-abundant water transporter, is associated with latex dilution and yield in the rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis Muell. Arg.). PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0125595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priyadarshan, P.M. Breeding hevea rubber: Formal and molecular genetics. Adv. Genet. 2004, 52, 51–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, L.; Jia, Q.; Ping, X. Direct and indirect effects of environmental factors on daily CO2 exchange in a rainfed maize cropland-a SEM analysis with 10 year observations. Field Crops Res. 2019, 242, 107591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadpour, S.; Bayzidi, Y.; Trachte, K. Spatio-temporal patterns of evapotranspiration in the temperate Eastern German lowlands and its response to climate and land use change. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2025, 156, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, J.; Li, X.; Xu, C.Y. Distinguishing the relative impacts of climate change and human activities on variation of streamflow in the Poyang Lake catchment, China. J. Hydrol. 2013, 494, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwar, A.; Renner, M.; Kleidon, A. Imprints of evaporation and vegetation type in diurnal temperature variations. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss. 2020, 2020, 4923–4942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xie, P.; Lai, C.; Chen, X.; Wu, X.; Zeng, Z.; Li, J. Spatiotemporal variability of reference evapotranspiration and contributing climatic factors in China during 1961–2013. J. Hydrol. 2017, 544, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Chen, Y. Analysis of dynamic spatiotemporal changes in actual evapotranspiration and its associated factors in the Pearl River Basin based on MOD16. Water 2017, 9, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Z.; Shi, Z.; Gu, S.; Wang, T.; Zhu, W.; Feng, G. Impact of climate change and rubber (Hevea brasiliensis) plantation expansion on reference evapotranspiration in Xishuangbanna, Southwest China. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 830519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhao, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhao, J. Spatial and temporal characteristics of actual evapotranspiration and its influencing factors in Selin Co Basin. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2024, 155, 6195–6211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhajharia, D.; Dinpashoh, Y.; Kahya, E.; Singh, V.P.; Fakheri-Fard, A. Trends in reference evapotranspiration in the humid region of northeast India. Hydrol. Process. 2012, 26, 421–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.-X.; Thomas, A. Spatiotemporal variability of reference evapotranspiration and its contributing climatic factors in Yunnan Province, SW China, 1961–2004. Clim. Change 2013, 116, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, Y.; He, D. Spatiotemporal variations of actual evapotranspiration over the Lake Selin Co and surrounding small lakes (Tibetan Plateau) during 2003–2012. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2016, 59, 2441–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.; Xu, C.-Y.; Chen, D.; Singh, V.P. Spatial and temporal characteristics of actual evapotranspiration over Haihe River basin in China. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2012, 26, 655–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Zhao, Y.; Guan, H.; Tang, Y.; Yang, M.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, J. Estimating spatiotemporal dynamics of ET and assessing the cause for its increase in China. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2023, 333, 109394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringgaard, R.; Herbst, M.; Friborg, T. Partitioning forest evapotranspiration: Interception evaporation and the impact of canopy structure, local and regional advection. J. Hydrol. 2014, 517, 677–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, D.; Kang, S.; Yao, L.; Zhang, L. Estimation of evapotranspiration and its components from an apple orchard in northwest China using sap flow and water balance methods. Hydrol. Process. 2007, 21, 931–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, G.G. Tamm review: Leaf Area Index (LAI) is both a determinant and a consequence of important processes in vegetation canopies. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 477, 118496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.S.; Paredes, P.; Melton, F.; Johnson, L.; Mota, M.; Wang, T. Prediction of crop coefficients from fraction of ground cover and height. background and validation using ground and remote sensing data. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 241, 106197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).