Abstract

Accurate estimation of individual tree Above-Ground Biomass (AGB) is essential for assessing forest carbon sequestration. This study integrates multi-source Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) remote sensing (LiDAR and RGB) with machine learning to estimate the AGB of Larix principis-rupprechtii in a natural secondary forest. We applied an instance segmentation approach to identify individual trees and extract structural and spectral features, which were subsequently optimized before model training. Our results demonstrate that models utilizing combined multi-source features significantly outperformed those relying on a single data source. The Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) algorithm achieved the best performance, with an R2 of 0.770 using the combined feature set. SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) interpretation revealed that structural attributes—particularly tree height and crown volume—were the most influential predictors, underscoring their greater importance over spectral information. This study presents an effective and interpretable framework for accurate tree-level AGB estimation, supporting scalable monitoring of regional forest carbon dynamics.

1. Introduction

Forests, as the most significant carbon pool in the global carbon cycle, store more than two-thirds of the total carbon in terrestrial ecosystems, possessing substantial carbon sequestration potential and the capacity to mitigate climate change [1,2]. Forest biomass serves as a key indicator for assessing forest carbon storage capacity and is crucial for research on the global carbon cycle and climate change evaluation [3]. Accurate estimation of forest biomass contributes to predicting carbon emissions from forests and is of great importance for sustainable forest management and conservation [4].

Remote sensing offers comprehensive, multi-temporal, and large-scale monitoring capabilities, enabling continuous observation of forest conditions. Compared to traditional survey methods, it significantly reduces labor, material, and financial costs [5]. Remote sensing data contain abundant information related to forest biomass [6,7,8,9], such as tree height and canopy structure. By analyzing the relationship between these variables and forest biomass, optimal biomass models can be developed. Numerous studies have demonstrated that integrating multiple types of remote sensing data can improve the accuracy of forest biomass estimation [10,11,12], including optical imagery and LiDAR. Optical remote sensing imagery provides rich spectral information and supports the derivation of vegetation indices for estimating Above-Ground Biomass (AGB) [13]. However, optical data are limited in capturing vertical structural information at the individual tree level and are susceptible to weather conditions and signal saturation, which can reduce biomass estimation accuracy [14]. In contrast, LiDAR is highly valued for forest biomass estimation due to its strong penetration capability, multi-echo information, and efficiency in acquiring vertical forest structure. It shows great potential, particularly for biomass estimation at the individual tree level, and provides a solid foundation for accurately retrieving forest parameters [15,16,17]. Nevertheless, the use of multi-source data also introduces challenges in forest biomass prediction, including the processing of diverse datasets, the extraction and matching of individual tree information, the selection of appropriate metrics, and the choice of a suitable predictive model.

Accurate individual tree segmentation is crucial for improving the estimation of forest biomass. With advances in artificial intelligence, deep learning algorithms have achieved significant results in individual tree segmentation. The application of deep learning in this field primarily relies on Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and other deep learning frameworks, among which CNNs and their improved architectures are the most widely used. These technologies provide new solutions for individual tree segmentation [18,19,20,21]. Some studies have proposed the use of optimization algorithms to enhance segmentation accuracy and have also explored integrating deep learning methods with traditional segmentation approaches to improve performance. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that methods combining CNNs and ensemble learning for tree species identification using Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) imagery can significantly increase the overall accuracy of individual tree detection [22,23,24].

Machine learning techniques have been widely applied in forest AGB estimation. These methods primarily utilize computer systems to learn from data, autonomously improve and adapt, and make estimations or decisions based on learned patterns. They are effective in handling high-dimensional and correlated data. Algorithms such as Random Forest (RF) [25,26], Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM) [27], Support Vector Regression (SVR) [28], Categorical Boosting (CatBoost) [29], and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) [30] have been employed in forest biomass estimation. These methods can effectively model the relationship between variables and AGB and handle high-dimensional correlated data, demonstrating significant advantages in the process of forest biomass inversion. Although different data sources and machine learning algorithms can be used to construct individual tree AGB prediction models, their application across different forest stands is subject to certain limitations due to factors such as regional vegetation structure and environmental heterogeneity. Therefore, selecting the optimal prediction model that aligns with the ecological characteristics of the target region is essential.

This study was conducted in the Guandi Mountain Forest Region of Shanxi Province, Northern China. We developed a novel, integrated framework that synergizes UAV-LiDAR and RGB data with interpretable machine learning to improve the estimation of forest AGB in natural secondary forests of Larix principis-rupprechtii. The proposed approach spans from accurate individual tree extraction to the selection of feature variables significantly correlated with AGB, effectively addressing the critical limitations associated with single-source remote sensing data. To evaluate the framework, we employed three representative machine learning algorithms—RF, LightGBM, and XGBoost—using RF as a baseline to compare predictive accuracy. The findings not only provide a scientific basis for the quantitative management of local forest resources but also offer a transferable methodology for AGB estimation in other forest ecosystems, supporting broader efforts in sustainable forest management and carbon monitoring.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

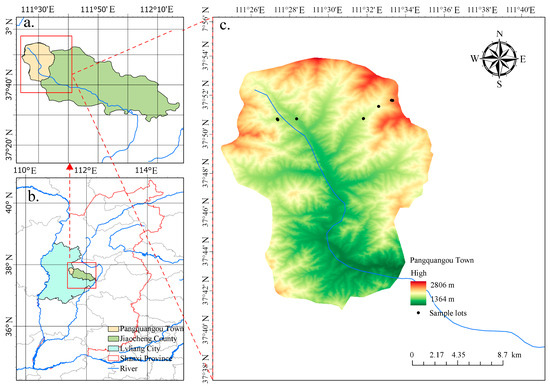

The study area is located in the Pangquangou Nature Reserve, Lvliang City, Shanxi Province, Northern China (Figure 1). It spans from 111°22′ to 111°33′ E longitude, and 37°45′ to 37°55′ N latitude, with an elevation ranging from 1800 to 2831 m above sea level. The region experiences a warm–temperate continental monsoon mountain climate, characterized by an average annual temperature of 4.3 °C, a mean relative humidity of 70%, and an average annual precipitation of approximately 820 mm, primarily concentrated between July and September. The frost-free period lasts about 180 days. Vegetation types include cold-temperate coniferous mixed forests, coniferous-broadleaf mixed forests, and temperate broadleaf mixed forests. Dominant tree species consist of Larix principis-rupprechtii, Pinus tabuliformis, Populus davidiana, Betula albosinensis, and Betula platyphyll.

Figure 1.

Location of the sample plots. (a) Pangquangou Town, Jiaocheng Count; (b) Jiaocheng County, Lvliang City, Shanxi Province; (c) Layout of sampling plots in the study area.

2.2. Data and Processing

2.2.1. Field Data Collection and AGB Calculation

This study was conducted within the optimal distribution range of natural secondary forests of Larix principis-rupprechtii. Eight representative 60 m × 60 m square sample plots were established after comprehensive consideration of stand density and site conditions. All trees with a Diameter at Breast Height (DBH) ≥ 5 cm were measured in the field survey. A total of 936 Larix principis-rupprechtii trees from these plots were used for model development. The survey recorded DBH, tree Height (H), crown width (CW), elevation, slope, aspect, and individual tree position for each tree. A summary of the plot characteristics is provided in Table 1. Individual tree biomass was calculated using allometric equations [31] based on the field survey data. The calculation formula is as follows:

where Y is the aboveground biomass (kg), DBH is the Diameter at Breast Height (cm), and H is the tree Height (m). The model parameters are a = 0.0275 and b = 0.9576. This species-specific model originally reported a high predictive accuracy (R2 = 0.99).

Table 1.

Summary of sample plot data.

The field-measured DBH and H used in the allometric equations are associated with inherent uncertainties, estimated at ±0.5 cm and ±5%, respectively, based on standard forestry practices. These uncertainties propagate into the computed AGB values, contributing to noise in the ground reference data. It is important to emphasize that all models were trained and evaluated against this common reference, ensuring a fair and valid comparison of their performance.

2.2.2. UAV Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

This study utilized a DJI Matrice 300 RTK unmanned aerial vehicle equipped with a Zenmuse H20T multi-sensor platform to acquire RGB imagery and LiDAR point cloud data within the study area in July 2024. The flight mission was conducted in terrain-following mode at a relative altitude of 90 m, with both forward and side overlap rates set to 85%. Meteorological conditions during data acquisition met aerial surveying standards. The original images were processed using DJI Terra software (Version 3.7.6) to generate a Digital Orthophotography Map (DOM), and a Digital Surface Model (DSM). Simultaneously, the collected point cloud data were processed in LiDAR360 (Version 8.1, Beijing Green Valley International, located in Beijing, China) for denoising and classification, enabling the extraction of a high-precision Digital Elevation Model (DEM). We assessed the vertical accuracy of the DEM by comparing it with 8 high-precision GPS ground control points, which indicated a mean error of 1.64 m. To account for this systematic bias, we subtracted this constant offset from the original DEM to produce an adjusted DEM for all downstream analyses. This calibration significantly reduced elevation estimation errors. Based on the elevation difference between the surface and terrain, a Canopy Height Model (CHM) was generated through algebraic subtraction of the DSM and DEM, expressed as: CHM = DSM − DEM.

2.3. Individual Tree Feature Extraction

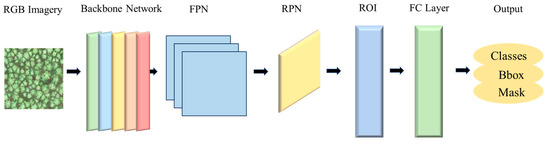

Mask Region-Based Convolutional Neural Network (Mask R-CNN) builds upon Faster R-CNN by incorporating an additional mask branch within the object detection framework. Its primary structure consists of a backbone network, a region proposal network (RPN), a module for region of interest (ROI) classification and bounding box regression, and a mask segmentation branch [32] (Figure 2). In this study, ResNet50 combined with a feature pyramid network (FPN) was employed as the backbone network. Multi-scale feature extraction and fusion techniques were utilized to enhance detection performance. The RPN was used to identify candidate object regions within the feature maps. The network architecture primarily operates in three stages to achieve accurate detection and segmentation of individual trees from UAV imagery. First, the original image was input into the backbone CNN to extract multi-scale fused feature information. Next, the resulting feature maps, along with the original UAV image, were fed into the RPN. By applying a sliding window over the feature maps and combining predefined anchors, the RPN predicts the location and confidence score of bounding boxes associated with each anchor. After a series of filtering and non-maximum suppression (NMS) operations, a set of high-quality ROIs were generated, which serve as key regions for subsequent processing. Finally, feature alignment was performed on the generated ROI to mitigate quantization errors inherent in traditional ROI pooling, thereby ensuring the accuracy of feature extraction.

Figure 2.

The framework of the Mask Region-Based Convolutional Neural Network (Mask R-CNN) model. Note: FPN, feature pyramid network; RPN, region proposal network; ROI, region of interest; FC Layer, fully connected layer.

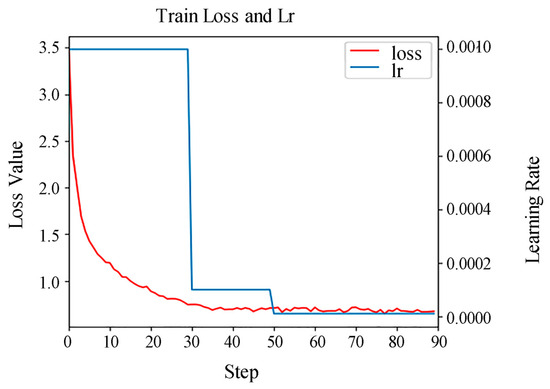

To meet the input requirements of the Mask R-CNN algorithm, the RGB images were cropped into 512 × 512 pixel tiles with a 25% overlap rate, ensuring all trees within the sample plots were completely represented in the imagery. Crucially, this overlap was applied only within each dataset split, and the training, validation, and test sets were strictly separated with no spatial overlap between them. A total of 72 images were obtained and randomly divided into training, validation, and test sets in a ratio of 7:1:2. the images were annotated using the VIA software (Version 1.0.6), and the annotation files were saved in JSON format. Among these, the test set contained 457 individually annotated trees for the final performance evaluation. All annotations were cross-verified by two independent experts, with a third expert resolving discrepancies to ensure quality and consistency. For model training, ResNet50 was selected as the feature extraction backbone network. Due to GPU memory constraints when processing the 512 × 512 pixel image tiles, a batch size of 2 was employed. Given the potential for instability with a small batch size, significant attention was paid to learning rate tuning and training monitoring. The resulting validation loss curve (Figure 3) shows a smooth, monotonic descent and stable convergence, indicating that the training process was not adversely affected. The Mask R-CNN model was trained with the following specifications: an initial learning rate of 0.001, a batch size of 2, and a maximum of 90 epochs. Early stopping was implemented, halting training if the validation loss showed no improvement for 15 consecutive epochs, with restoration to the best-performing weights. To enhance model robustness and prevent overfitting, comprehensive data augmentation techniques were applied during training, including: random horizontal flipping (50% probability), random vertical flipping (20% probability) and color jittering with brightness, contrast, and saturation variations of ±20%. For performance evaluation, a detection was considered a true positive only if the Intersection over Union (IoU) with a ground-truth annotation exceeded 0.5. Segmentation errors were handled as follows: in cases of over-segmentation (multiple predicted masks for a single tree), only the prediction with the highest IoU was retained as a true positive, and the others were counted as false positives; in cases of under-segmentation (a single predicted mask covering multiple trees), it was counted as one false positive and the corresponding ground truth trees were counted as multiple false negatives.

Figure 3.

Validation loss curve. Note: Lr denotes the learning rate.

To ensure consistency in feature extraction, individual trees detected in the RGB imagery were matched with those in the point cloud data. To account for potential GPS-coordinate misalignment between the two datasets, a two-stage matching strategy was employed. First, the geographic coordinate systems of the RGB-derived tree locations and the LiDAR-derived tree locations were rigorously aligned by referencing common ground control points visible in both the orthophoto and the point cloud. Subsequently, tree matching was performed based on both spatial proximity and crown morphology. Tree segmentation from the point cloud was performed using a seed point-based region growing algorithm in LiDAR360. The algorithm operated in two sequential steps: first, potential tree apexes were identified as local maxima within a variable-sized moving window (5 m) applied to the CHM, with the window size adaptively scaled based on the estimated tree height to account for varying crown sizes. Subsequently, these seed points served as initiation markers for a region-growing process that delineated individual tree crowns, constrained by a minimum height threshold of 1.5 m to suppress spurious segmentation of low-lying vegetation. Based on the co-extraction of point cloud and RGB imagery, a total of 88 feature variables were obtained (see Supplementary Table S1 for the complete list), comprising 23 from the RGB images and 65 from the point cloud data. The results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Feature extraction.

2.4. Variable Selection and Importance Analysis

In forest ecosystems, the accuracy of AGB estimation and modeling efficiency are closely related to the selected variables. Multiple variables derived from disparate remote sensing data sources have inherently different units. Incorporating all of them into AGB modeling increases model complexity and computational demand, and may lead to overfitting, thereby reducing estimation accuracy. To identify the most influential variables for AGB prediction, this study performed variable selection separately for each data source. Furthermore, prior to the feature importance analysis, all features were standardized using Z-score normalization to ensure a fair comparison of their contributions across different measurement units and scales. To prevent data leakage, feature selection was rigorously embedded within each fold of the cross-validation. In every iteration, the feature subsets for RGB, LiDAR, and combined data were independently identified from the training set using RF permutation importance, with the test set completely excluded from this process.

In the first step, we applied permutation importance from a training-set-trained RF model to both identify and rank the most influential features for AGB estimation [33]. This approach primarily measures feature importance by observing the extent of model performance degradation after randomly shuffling the values of a specific feature in the training set, thereby enabling the ranking of variables based on their importance. By comparing prediction results using the full set of variables with those from the filtered set, influential variables were selected for AGB prediction according to their importance rankings, thereby avoiding the inclusion of redundant variables that could diminish model accuracy. The same feature set identified from the training data was then applied to the test set for final model evaluation. In the second step, SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) analysis was applied to interpret the magnitude and direction (positive or negative) of each variable’s contribution to predictions across different models. As an interpretability method grounded in game theory, SHAP can be used to explain the contributions of features in machine learning models [34,35,36]. It quantifies the “contribution value” of each variable to the prediction outcome, thereby aiding in understanding how the model makes decisions. This study adopted a combined approach of RF and SHAP analysis to perform variable selection and interpret feature contributions, providing a more holistic explanation of the relationships between features and predicted values.

2.5. AGB Model Prediction and Parameter Tuning

Bayesian optimization constitutes a family of algorithms designed for the global optimization of black-box functions. These methods leverage Bayesian statistical techniques to model the unknown objective function and iteratively explore the search space to identify optimal solutions. Each algorithm possesses unique characteristics, advantages, and limitations, making them applicable to diverse optimization problems [27].

Prior to modeling, we assessed the spatial dependency of our predictor variables using Global Moran’s I tests across the eight study plots. The analysis confirmed significant spatial autocorrelation (p < 0.05) in six key vegetation-related features derived from RGB imagery (see Supplementary Table S2 for complete results). This empirical finding of spatial structure necessitated a validation approach that explicitly accounts for spatial clustering to prevent overoptimistic performance estimates. To address potential spatial autocorrelation and provide a robust assessment of model generalizability, we adopted a spatial validation approach using leave-one-plot-out cross-validation (LOPO-CV). In this scheme, models were trained on data from seven plots and tested on the remaining held-out plot, with this process repeated eight times until each plot had served as the test set once. This ensures that the evaluation reflects performance on completely independent spatial units with differing environmental conditions.

On this basis, the extracted feature variables were divided into three groups according to their data sources: RGB image features, LiDAR point cloud features, and their combined feature set. Individual tree biomass estimation models were developed using three representative machine learning algorithms: RF, LightGBM, and XGBoost. In our comparative framework, RF was employed as the baseline model, representing a strong, well-established benchmark in machine learning for ecological applications. The performance of the more advanced LightGBM and XGBoost algorithms was then evaluated against this RF baseline to assess potential improvements in predictive accuracy. Hyperparameter optimization for all algorithms was performed via the Bayesian optimization algorithm (see Supplementary Table S3 for hyperparameter settings). All algorithms were implemented in Python 3.8, primarily utilizing Scikit-learn, LightGBM, and XGBoost computational libraries.

2.6. Evaluation Metrics

2.6.1. Accuracy Evaluation of Individual Trees

Recall, precision, and the F1-score were used to evaluate individual tree crown detection, while the IoU was employed to assess the accuracy of crown delineation (Equations (2)–(5)). A tree crown was considered correctly extracted when the IoU exceeded 50%. Recall represents the proportion of correctly identified trees in the test set, while precision indicates the proportion of correctly identified trees among all model detections. The F1-score reflects the overall accuracy based on the harmonic mean of recall and precision.

where TP denotes the number of correctly detected trees; FN denotes the number of undetected trees; FP denotes the number of erroneously detected trees; Bactual denotes the ground truth crown mask; Bpredicted denotes the predicted crown mask.

2.6.2. Performance Evaluation of the AGB Models

The determination coefficient (R2) and the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) were selected to evaluate the agreement between predicted and measured values (Equations (6) and (7)). The value of R2 ranges between 0 and 1, where values closer to 1 indicate a better fit of the model to the data. A lower RMSE value signifies higher predictive accuracy of the model, reflecting smaller discrepancies between the predicted and actual values. Furthermore, the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) was used as a robust measure of average error magnitude, while the relative RMSE (rRMSE) expressed the error as a percentage to facilitate cross-study comparisons. The Bias metric was calculated to identify any systematic overestimation or underestimation tendencies in the predictions (Equations (8)–(10)).

where n denotes the sample size; yi denotes the actual measured value; ŷi denotes the predicted value; denotes the mean of the actual values.

To quantify the uncertainty associated with these performance estimates, the 95% confidence intervals for all metrics were derived through a non-parametric bootstrapping procedure with 1000 iterations. This approach provides a robust empirical estimate of the precision and stability of our model evaluations.

3. Results

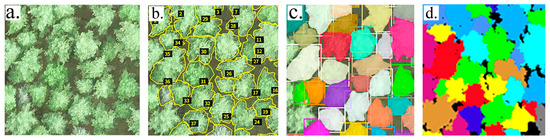

3.1. Individual Tree Segmentation

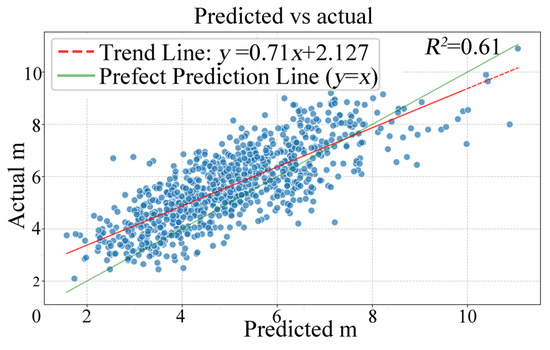

This study employed the Mask R-CNN segmentation method to perform individual tree segmentation on RGB imagery of a natural secondary forest of Larix principisrupprechtii. The segmentation results in Figure 4 demonstrate tree crowns with clear and complete contours. The evaluation of the model yielded high performance, with a recall of 93.07%, a precision of 87.5%, and an F1-score of 90.21%. Following the COCO evaluation protocol, the model attained an Average Precision (AP) of 0.663 across IoU thresholds from 0.50 to 0.95. At the specific IoU threshold of 0.50, the AP was 0.905, while at the more stringent threshold of 0.75, the AP reached 0.844, demonstrating robust performance across varying matching criteria. To further validate the deep learning model, we conducted a comparative analysis between the measured average crown width and the automatically segmented average crown width (Figure 5). The results demonstrate good consistency in the overall trend, with an RMSE of 0.90 m. This indicates a strong correlation between the crown width parameters derived from the deep learning segmentation and the field-measured data. Based on the RGB segmentation results, a canopy matching process was further applied to the point cloud data, where individual trees were identified using a seed point-based algorithm (Figure 4d). The summary of the matching outcomes is shown in Table 3. Out of the total 1070 field-measured trees, 936 (87.5%) were successfully matched. The remaining 134 trees (12.5%) were excluded from subsequent analysis due primarily to omission errors (8.4%), where trees were not detected in the imagery, and segmentation errors (4.1%).

Figure 4.

Individual tree segmentation results. (a) Original RGB imagery; (b) Annotated imagery, where the yellow outlines indicate tree crown areas and the numbers within black boxes correspond to individual tree crown IDs; (c) Segmentation result from RGB imagery, with each color representing a distinct tree crown; (d) Segmentation result from point cloud data, with each color also representing a tree crown—these crowns correspond to the same trees shown in Subfigure (c).

Figure 5.

Scatter plot of mean crown width extraction.

Table 3.

Individual tree matching outcomes.

3.2. Selection of Variables for Modeling

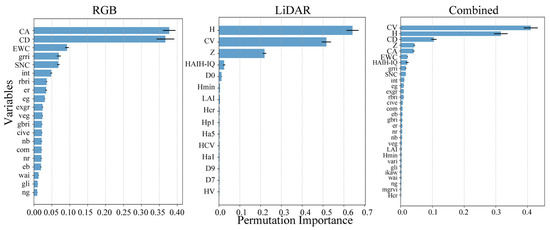

This study employed the RF algorithm to perform variable selection on three datasets, and evaluated the importance ranking of variables within each group. A higher importance value indicates a greater contribution of the variable to the model. Figure 6 illustrates the importance distribution of the filtered variables in the three groups, with the horizontal axis representing the variable importance value, and the vertical axis listing the feature names.

Figure 6.

Ranking of feature importance.

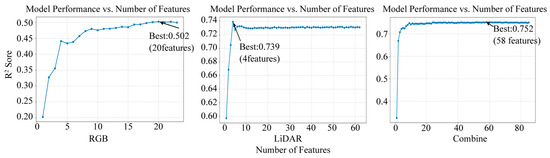

To quantitatively determine the optimal number of features for each dataset, we conducted a feature ablation analysis by sequentially incorporating the top-k ranked features and evaluating the corresponding model performance (R2). The resulting ablation curves (Figure 7) provide a data-driven justification for our final feature set sizes. The selected variables exhibited a highly skewed importance distribution, where a few key variables accounted for the majority of the feature importance scores, while the majority contributed minimally. For the RGB dataset, the ablation curve showed that model performance peaked at k = 20 features, which was consequently selected as the optimal set. For the LiDAR dataset, the importance ranking showed clear hierarchical differences. Starting from the Hmin variable, the contribution to the model decreased noticeably. The ablation analysis revealed that while the highest R2 was achieved with only the top 4 features, the performance stabilized and formed a distinct plateau after approximately k = 15 features. We therefore selected the top 15 features to ensure model robustness. For the combined dataset, the ablation curve demonstrated that model performance reached a clear plateau around k = 30 features, with subsequent additions yielding negligible improvement. Although the absolute performance peak occurred at k = 58 features, the marginal gain in R2 (less than 0.01) did not justify the incorporation of 28 additional potentially redundant variables that could increase model complexity and overfitting risk. Thus, k = 30 was selected as the optimal cutoff, effectively balancing predictive accuracy with model parsimony. By comparing the predictive performance before and after variable selection, the final feature sets were determined as follows: the top 20 important variables were retained for RGB data, the top 15 for LiDAR point cloud data, and the top 30 for the combined dataset.

Figure 7.

Feature ablation curves.

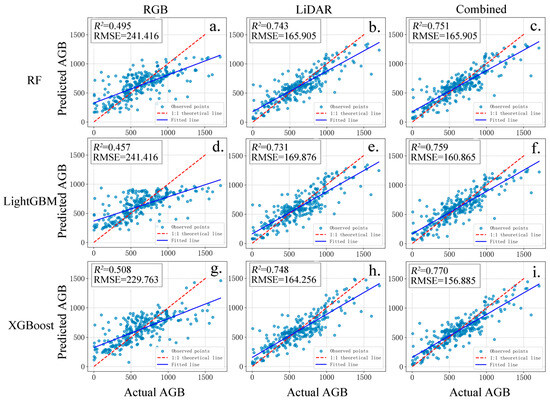

3.3. Accuracy Assessment of the AGB Estimation

This study developed nine individual tree AGB prediction models from the three datasets. Their performance was evaluated using scatter plots (Figure 8) and evaluation metrics (Table 4). The precision of the estimates was quantified using 95% confidence intervals derived from non-parametric bootstrapping (see Supplementary Table S4). The results indicated that models based on single-feature datasets exhibited lower prediction accuracy compared to those using combined features. When predicting individual tree AGB using only RGB features, the R2 values of the three models were 0.495, 0.457, and 0.508, respectively. Among them, the XGBoost model achieved the highest R2 value (0.508), followed by the RF model (0.495), with the LightGBM model yielding the lowest R2 (0.457) in RGB-only feature prediction. Notably, the models using RGB data alone exhibited the highest uncertainty, with the widest confidence intervals for R2, specifically, the interval for the RF model was [0.3953, 0.5795]. Furthermore, these models also yielded the largest rRMSE, exceeding 36%, indicating that their estimates are less reliable and accurate. For AGB prediction using only LiDAR point cloud features, the R2 values of the three models were 0.743, 0.731, and 0.748, respectively. The ranking of model performance remained consistent with that of the RGB-only models, with the XGBoost algorithm consistently yielded the highest R2 values across different feature sets. When LiDAR features were incorporated into the RGB-based feature set for biomass prediction, the R2 values of the different models were 0.751, 0.759, and 0.770, respectively. The XGBoost model again achieved the best performance in individual tree AGB prediction. However, it is worth noting that in the combined feature modeling scenario, the LightGBM model achieved a higher R2 value (0.759) compared to the RF model (0.751) in the combined feature scenario. Furthermore, an analysis of the bias metric revealed a general tendency for slight underestimation (negative bias) across all models, particularly in the combined and LiDAR scenarios. However, the bootstrapped confidence intervals for bias in all cases encompassed zero, suggesting that this systematic error was not statistically significant.

Figure 8.

Predicted and actual AGB values. (a) RGB-RF AGB model; (b) LiDAR-RF AGB model; (c) Combined-RF AGB model; (d) RGB-LightGBM AGB model; (e) LiDAR-LightGBM AGB model; (f) Combined-LightGBM AGB model; (g) RGB-XGBoost AGB model; (h) LiDAR-XGBoost AGB model; (i) Combined-XGBoost AGB model.

Table 4.

Model performance evaluation for individual tree AGB estimation.

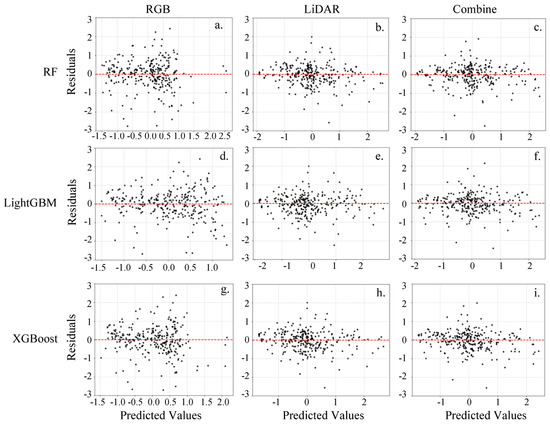

To further evaluate the prediction accuracy and error characteristics of these models, we conducted comprehensive residual analysis for all nine models across the three feature datasets (Figure 9). Among them, models using combined and LiDAR features exhibited similarly compact residual distributions, while RGB-only models showed comparatively greater dispersion. This visual pattern aligns with the rRMSE metrics in Table 4, where RGB models consistently demonstrated higher error rates (>36%). All models displayed slight underestimation tendencies, with random residual scatter indicating no systematic bias.

Figure 9.

The residual distribution plots of various models on the test datasets. (a) Residual distribution plot for the RGB-RF AGB model; (b) Residual distribution plot for the LiDAR-RF AGB model; (c) Residual distribution plot for the Combined-RF AGB model; (d) Residual distribution plot for the RGB-LightGBM AGB model; (e) Residual distribution plot for the LiDAR-LightGBM AGB model; (f) Residual distribution plot for the Combined-LightGBM AGB model; (g) Residual distribution plot for the RGB-XGBoost AGB model; (h) Residual distribution plot for the LiDAR-XGBoost AGB model; (i) Residual distribution plot for the Combined-XGBoost AGB model.

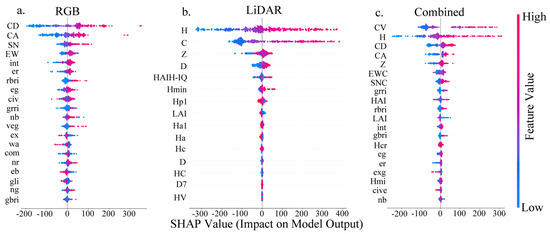

3.4. SHAP Analysis

Based on the performance of the three model groups in predicting AGB, the XGBoost model was selected for variable interpretation. Figure 10 illustrates the SHAP values of each feature in the three variable groups under the XGBoost model, quantifying their contribution to the model’s AGB predictions. In the plot, the sign of the SHAP value denotes the direction of a feature’s influence on the model output, with positive values exerting a positive influence and negative values a negative one. The color scale encodes feature values, with red indicating higher values that enhance the output and blue indicating lower values that diminish it. Among the three variable groups, the analysis based on RGB features revealed that CD, CA, and SNC had the highest mean absolute SHAP values, identifying them as the most influential features for the model’s predictions. Although other variables also contributed to the model outputs, their relative influence was weaker. The analysis of LiDAR-based features demonstrated that H and CV were the most influential predictors in the model, as indicated by their wide distributions and high mean absolute SHAP values. When all variables were combined, the top three features—CV, H, and CD—exhibited broad distributions and large absolute SHAP values, indicating strong associations with the model’s prediction target and their dominant role in the model’s decision-making process. Among these, the first two (CV and H) were derived from LiDAR data, while CD originated from RGB data. Notably, the features assigned the highest importance by the model were derived from point cloud data.

Figure 10.

SHAP analysis of the XGBoost model. (a) Interpretation based solely on RGB features; (b) Interpretation using LiDAR point cloud features only; (c) Interpretation with combined features. Each point in the plot represents the SHAP value for an individual sample. The horizontal axis shows the direction and magnitude of a feature’s impact on the model output: positive values denote a feature that increases the predicted AGB, while negative values indicate a suppressing effect that reduces the prediction. The vertical axis ranks features by their overall importance in descending order. The absolute SHAP value reflects the strength of the feature’s influence. A color gradient from red to blue (right bar) corresponds to the actual feature value, with red representing high values and blue low values.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effectiveness of Individual Tree Segmentation

Building upon previous studies [20,21,24,37], this study employed the Mask R-CNN instance segmentation model to perform individual tree crown segmentation from high-resolution visible light imagery acquired by UAVs in forested areas, achieving automated detection and identification of individual trees. Although the data generation and model training process was relatively time-consuming, the evaluation metrics (recall: 93.07%, precision: 87.5%, F1-score: 90.21%) indicate that the segmentation results compare favorably with or exceed those reported in existing studies using traditional remote sensing methods for individual tree segmentation [23,38,39]. Furthermore, the results are consistent with findings from studies by Zhang et al. [20] and Fu et al. [40], providing further evidence of the applicability of deep learning methods in complex forest stand structures. This establishes a reliable foundation for subsequent canopy matching with point cloud data. Further comparison between automatically extracted crown widths and field-measured results (Figure 5) revealed good consistency in overall trends, aligning with existing studies, and further confirming the reliability of the instance segmentation model in extracting crown width parameters. Although certain deviations were observed, these may be attributed to factors such as image resolution, shadow occlusion, crown overlap, and manual measurement errors [41]. Moreover, based on the RGB image segmentation results, this study implemented canopy matching with point cloud data and applied a seed point-based algorithm to extract three-dimensional information of individual trees (Figure 4d), thereby extending the application potential of two-dimensional segmentation results into three-dimensional space. Despite achieving satisfactory individual tree detection rates, challenges remained in areas with high crown overlap, where distinguishing individual trees was difficult due to severe occlusion, complicating the isolation of complete crowns. This is likely attributable to high canopy closure in denser areas, which adversely affects crown segmentation and individual tree extraction [42,43]. Additionally, factors such as terrain slope within the UAV flight area and understory vegetation types may indirectly constrain crown segmentation effectiveness by influencing image quality [44].

4.2. Advantages of Using UAV-Based Multisource Data for Estimating AGB

In remote sensing-based AGB prediction, variable selection directly influences estimation accuracy, making the choice of appropriate feature variables crucial for reliable AGB estimation [45]. This study employed RF-based feature importance evaluation to identify key features for individual tree AGB prediction. The filtered datasets (RGB, LiDAR, and combined features) all exhibited a significantly skewed distribution of feature importance (Figure 6), indicating that the AGB prediction model performance is predominantly driven by core structural variables, regardless of the data source type, and that a larger number of variables does not necessarily yield better results [46,47]. When using single-data sources for AGB estimation, a notable performance gap was observed between RGB-only (R2 = 0.508) and LiDAR-only (R2 = 0.748) models. Among RGB-derived features, crown width contributed the most, reflecting the indicative role of crown metrics in AGB prediction, which aligns with findings from related studies [48,49,50]. For LiDAR data, tree height was the most influential factor, underscoring the significant contribution of vertical growth to biomass accumulation [6,51,52]. It should be acknowledged that tree height measurement, derived from the LiDAR point cloud, is contingent upon the accuracy of the DEM. The residual vertical uncertainty of the calibrated DEM (mean error = 1.64 m) therefore propagates into the tree height extraction process, becoming a potential source of error in the AGB estimation. This propagated error is considered to have a limited effect on the final AGB values but is included in the overall uncertainty budget.

After integrating LiDAR data with RGB features, model accuracy improved to R2 = 0.770, achieving the optimal performance by synergistically combining horizontal and vertical structural information. This represents an improvement of 0.093 in R2 over the previous method of Li et al. (R2 = 0.677) [46]. This is consistent with previous research demonstrating that combining variables enhances AGB prediction accuracy [53,54]. According to the variable importance ranking, tree height and crown volume contributed most significantly to AGB prediction, followed by crown width. Previous studies have also confirmed a strong relationship between tree height and biomass [55,56].

4.3. Biomass Prediction Model

This study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of different machine learning algorithms in predicting individual tree AGB in natural secondary forests of Larix principis-rupprechtii by integrating UAV multi-source remote sensing features, ultimately to construct a robust prediction model. Among the nine AGB models developed from the three datasets, XGBoost consistently achieved the highest R2 values across all variable groups (RGB: R2 = 0.503, LiDAR: R2 = 0.732, combine: R2 = 0.760) compared to the other two model algorithms. The feasibility of the XGBoost model for forest AGB prediction has also been confirmed by studies such as Wang et al. [30] and Sainuddin et al. [57], indicating promising prospects for enhancing biomass estimation accuracy. Furthermore, some researchers suggested that variable selection had a more pronounced impact on XGBoost than on RF [47], which might explain the superior performance of XGBoost over the other model algorithms. However, the performance trends of the RF and LightGBM models differed from those of XGBoost. When using either RGB or LiDAR data alone, when using either RGB or LiDAR data alone, the RF model achieved higher R2 values than LightGBM. In contrast, LightGBM yielded a higher R2 value than RF when the two data sources were combined for prediction. This observation aligns with findings from Luo et al. [58], whose study indicated that model performance does not follow a completely consistent trend across different variables. This discrepancy is likely due to variations in variable importance rankings across different models, potentially explaining why LightGBM outperformed RF when combined variables were used.

4.4. SHAP Interpretation

In addition to improving the prediction accuracy of individual tree AGB, we aim to understand how input variables contribute to this enhancement. This study employed SHAP analysis on the optimal model to interpret the relative importance of variables in the constructed AGB model. In the RGB feature group, CD and CA were identified as the most influential predictors within the model, with their SHAP values showing a wide distribution range, and absolute values significantly higher than other variables. This aligns with findings from studies by Yu et al. [49], Liu et al. [50], Goodman et al. [59], and others. In contrast, vegetation indices such as exgr, er, and int demonstrated a relatively minor contribution to the model’s predictive performance. This may be because vegetation indices primarily reflect macro-level information like green coverage and luxuriance, making them more suitable for describing biomass conditions over large areas or at an overall level, while their effect on individual tree biomass variation is limited. Additionally, vegetation indices mainly reflect green leaf area and growth status rather than total biomass. Once trees reach a certain growth stage, green leaf area may change little, while woody volume and biomass continue to increase. Studies by Liu et al. [60] and Khaled et al. [61] also indicated that vegetation indices can be important predictors for stand-level biomass, which contrasts with their lower importance in our individual-tree-level model. In the point cloud feature group, H and CV were assigned the highest importance by the model. The high variability of their SHAP values indicates that the model’s predictions may be highly sensitive to changes in these vertical structure metrics [62]. When using combined variables to build the prediction model, the fitting accuracy was much greater than using RGB data alone, but the improvement compared to using LiDAR data alone was not substantial. According to the fitting results, the overall level of model accuracy does not depend on the number of variables. Instead, excessive redundant variables can significantly reduce model training speed. Therefore, selecting appropriate variables can accelerate model training, enhance model performance, and improve interpretability [60].

5. Conclusions

Accurate estimation of forest Above-Ground Biomass (AGB) is critical for assessing carbon sequestration potential and informing sustainable forest management. This study established an interpretable framework for estimating individual tree AGB in a Larix principis-rupprechtii natural secondary forest by integrating multi-source UAV remote sensing (RGB and LiDAR) with machine learning. The main conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- The Mask R-CNN model demonstrated robust performance in segmenting individual trees in open canopies (F1-score: 90.21%), yet its accuracy decreased in areas with dense and overlapping crowns, indicating a limitation in complex structural environments.

- (2)

- Feature-level fusion of RGB and LiDAR data significantly enhanced AGB estimation accuracy. The XGBoost model trained on the fused dataset achieved the best performance (R2 = 0.770), outperforming models using only RGB (R2 = 0.508) or LiDAR (R2 = 0.748) features, which confirms the complementary roles of horizontal crown detail and vertical structural information.

- (3)

- SHAP analysis revealed that structural attributes—including tree height, crown volume, mean crown width, and crown projection area—were the most influential predictors, while spectral vegetation indices contributed minimally at the individual tree level.

This study offers a scalable and transparent solution that can be extended to carbon stock monitoring in other structurally similar forest stands. Future work should advance the segmentation of dense canopies, integrate topographic correction factors, and validate model performance across trees of varying sizes and diverse forest conditions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/f16121819/s1, Table S1: Description of RGB and LiDAR features; Table S2: Results of the spatial autocorrelation analysis for individual tree AGB; Table S3: Configuration of the hyperparameter search space for Bayesian optimization; Table S4: Performance metrics for individual AGB estimation models: Mean and 95% confidence interval; Table S5: Dataset of LiDAR metrics, RGB features, and AGB data (partial).

Author Contributions

X.C. and L.Z. designed the specific scheme, completed the experiments, and wrote the paper. X.C., S.L., C.H. and Y.T. completed the result data analysis. L.Z. and Y.T. modified and directed the writing of the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Shanxi Basic Research Program Project, grant number 202303021222073.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the technical support from Yujun Sun’s research team at the College of Forestry, Beijing Forestry University. We extend our particular thanks to Yujun Sun, Hua Yang, Yifu Wang, Zhidan Ding, Yunhong Xie and Ruiting Liang for their valuable assistance and contributions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to have influenced the work reported in this paper.

References

- Matsuo, T.; Poorter, L.; van der Sande, M.T.; Abdul, S.M.; Koyiba, D.W.; Opoku, J.; de Wit, B.; Kuzee, T.; Amissah, L. Drivers of biomass stocks and productivity of tropical secondary forests. Ecology 2025, 106, e4488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Li, G.; Wang, M.; Fan, Z. Analyzing the Uncertainty of Estimating Forest Aboveground Biomass Using Optical Imagery and Spaceborne LiDAR. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favero, A.; Daigneault, A.; Sohngen, B.; Baker, J. A system wide assessment of forest biomass production, markets, and carbon. GCB Bioenergy 2022, 15, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Song, W.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Ji, Y.; Zhang, X.; Gao, J. Climate factors affect forest biomass allocation by altering soil nutrient availability and leaf traits. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2023, 65, 2292–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D.; Onisimo, M.; Cletah, S.; Adelabu, S.; Tsitsi, B. Remote sensing of aboveground forest biomass: A review. Trop. Ecol. 2016, 57, 125–132. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Su, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Lin, G.; Guo, Q. Mapping the Global Mangrove Forest Aboveground Biomass Using Multisource Remote Sensing Data. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Pan, J.; Wang, J.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, J. Mapping of Forest Biomass in Shangri-La City Based on LiDAR Technology and Other Remote Sensing Data. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiy, I.A.; Im, S.T.; Kharuk, V. Estimating Aboveground Forest Biomass Using Radar Methods. Contemp. Probl. Ecol. 2022, 15, 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, M.L.; Pierce, L.; Bergen, K.; Sarabandi, K. Model-based estimation of forest canopy height and biomass in the Canadian Boreal forest using radar, LiDAR, and optical remote sensing. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2020, 59, 4635–4653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, B. Status and future of laser scanning, synthetic aperture radar and hyperspectral remote sensing data for forest biomass assessment. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2010, 65, 581–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zou, Y.; Wang, Y. Remote Sensing of Forest Above-Ground Biomass Dynamics: A Review. Forests 2025, 16, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, R.; Knapp, N.; Bohn, F.; Shugart, H.H.; Huth, A. The Relevance of Forest Structure for Biomass and Productivity in Temperate Forests: New Perspectives for Remote Sensing. Surv. Geophys. 2019, 40, 709–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankey, T.; Donager, J.; McVay, J.; Sankey, J.B. UAV lidar and hyperspectral fusion for forest monitoring in the southwestern USA. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 195, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncanson, L.I.; Niemann, K.O.; Wulder, M.A. Integration of GLAS and Landsat TM data for aboveground biomass estimation. Can. J. Remote Sens. 2010, 36, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyyppä, J.; Yu, X.; Hyyppä, H.; Vastaranta, M.; Holopainen, M.; Kukko, A.; Kaartinen, H.; Jaakkola, A.; Vaaja, M.; Koskinen, J.; et al. Advances in Forest Inventory Using Airborne Laser Scanning. Remote Sens. 2012, 4, 1190–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, S.C.; Zhao, K.; Neuenschwander, A.; Lin, C. Satellite lidar vs. small footprint airborne lidar: Comparing the accuracy of aboveground biomass estimates and forest structure metrics at footprint level. Remote Sens. Environ. 2011, 115, 2786–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Wu, X.; Tao, Y.; Li, M.; Qian, C.; Liao, L.; Fu, W. Review of Remote Sensing-Based Methods for Forest Aboveground Biomass Estimation: Progress, Challenges, and Prospects. Forests 2023, 14, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcin, C. Review of Segmentation Methods for Coastline Detection in SAR Images. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2023, 31, 839–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y. Research and Application of Data Classification Algorithm Based on Deep Learning. Acad. J. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2024, 7, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhou, J.; Wang, H.; Tan, T.; Cui, M.; Huang, Z.; Wang, P.; Zhang, L. Multi-Species Individual Tree Segmentation and Identification Based on Improved Mask R-CNN and UAV Imagery in Mixed Forests. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Lin, L.; Post, C.J.; Mikhailova, E.A.; Li, M.; Chen, Y.; Yu, K.; Liu, J. Automated tree-crown and height detection in a young forest plantation using mask region-based convolutional neural network (Mask R-CNN). ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2021, 178, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, R.; Habib, A. Optimization Method of Airborne LiDAR Individual Tree Segmentation Based on Gaussian Mixture Model. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 6167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Im, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhen, Z. A deep-learning-based tree species classification for natural secondary forests using unmanned aerial vehicle hyperspectral images and LiDAR. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 159, 111608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dersch, S.; Schöttl, A.; Krzystek, P.; Heurich, M. Towards complete tree crown delineation by instance segmentation with Mask R–CNN and DETR using UAV-based multispectral imagery and lidar data. ISPRS Open J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2023, 8, 100037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fararoda, R.; Reddy, R.S.; Rajashekar, G.; Chand, T.K.; Jha, C.; Dadhwal, V. Improving forest above ground biomass estimates over Indian forests using multi source data sets with machine learning algorithm. Ecol. Inform. 2021, 65, 101392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyre, T.T.; Aitor, B.; Ana, B.; Jose Manuel, L.G.; Manuel, G. Above-ground biomass estimation from LiDAR data using random forest algorithms. J. Comput. Sci. 2022, 58, 101517. [Google Scholar]

- Bui, Q.-T.; Pham, Q.-T.; Pham, V.-M.; Tran, V.-T.; Nguyen, D.-H.; Nguyen, Q.-H.; Nguyen, H.-D.; Do, N.T.; Vu, V.-M. Hybrid machine learning models for aboveground biomass estimations. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 79, 102421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Song, W.; Meng, J. Enhancing Mangrove Aboveground Biomass Estimation with UAV-LiDAR: A Novel Mutual Information-Based Feature Selection Approach. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, G.; Zhong, Q.; Xing, L.; Du, H. Prediction of Urban Forest Aboveground Carbon Using Machine Learning Based on Landsat 8 and Sentinel-2: A Case Study of Shanghai, China. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Xing, Y.; Fu, A.; Tang, J.; Chang, X.; Yang, H.; Yang, S.; Li, Y. Mapping Forest Aboveground Biomass Using Multi-Source Remote Sensing Data Based on the XGBoost Algorithm. Forests 2025, 16, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Xiao, Y.; Gai, Q.; Ji, W. A Preliminary Study on the Biomass of Larix principis-rupprechtii Forest Community in Pangquangou Nature Reserve. J. Shanxi Agric. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 1991, 11, 8. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollár, P.; Ross, G. Mask R-CNN. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. 2020, 42, 386–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altmann, A.; Toloşi, L.; Sander, O.; Lengauer, T. Permutation importance: A corrected feature importance measure. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 1340–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Du, H.; Mao, F.; Xu, Y.; Huang, Z.; Xuan, J.; Zhou, Y.; Hu, M. Estimation aboveground biomass in subtropical bamboo forests based on an interpretable machine learning framework. Environ. Model. Softw. 2024, 178, 106071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcilio, W.E.; Eler, D.M. From explanations to feature selection: Assessing SHAP values as feature selection mechanism. In Proceedings of the 2020 33rd SIBGRAPI Conference on Graphics, Patterns and Images (SIBGRAPI), Porto de Galinhas, Brazil, 7–10 November 2020; pp. 340–347. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, N.; Mason, E.; Xu, C.; Morgenroth, J. Estimating individual tree DBH and biomass of durable Eucalyptus using UAV LiDAR. Ecol. Inform. 2025, 89, 103169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Hao, Z.; Post, C.J.; Mikhailova, E.A.; Lin, L.; Zhao, G.; Tian, S.; Liu, J. Comparison of Classical Methods and Mask R-CNN for Automatic Tree Detection and Mapping Using UAV Imagery. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.; Eo, Y.; Kim, Y.; Kim, Y. Identification of individual tree crowns from LiDAR data using a circle fitting algorithm with local maxima and minima filtering. Remote Sens. Lett. 2013, 4, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Liang, D.; Ying, B.; Zhu, W.; Zhou, G.; Wang, Y. Assessment of an improved individual tree detection method based on local-maximum algorithm from unmanned aerial vehicle RGB imagery in overlapping canopy mountain forests. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2021, 42, 106–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Zhao, H.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, G.; Xiao, W.; Du, S.; Guo, W.; Liu, X. Automatic detection tree crown and height using Mask R-CNN based on unmanned aerial vehicles images for biomass mapping. For. Ecol. Manag. 2024, 555, 121712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, B.G.; Marconi, S.; Bohlman, S.; Zare, A.; White, E. Individual Tree-Crown Detection in RGB Imagery Using Semi-Supervised Deep Learning Neural Networks. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Li, J.; Jing, L.; Judah, A. Improving the efficiency and accuracy of individual tree crown delineation from high-density LiDAR data. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2014, 26, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, G.; Zheng, Y.; Lei, L.; Yao, Z.; Chen, M.; Zhang, X. A novel solution for extracting individual tree crown parameters in high-density plantation considering inter-tree growth competition using terrestrial close-range scanning and photogrammetry technology. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 209, 107849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Li, K.; Qiao, X.; Jiang, J.; Zhao, Y. An adaptive method for individual tree segmentation synthesizing canopy cover and competitive mechanism using UAV data. Ecol. Inform. 2025, 91, 103360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wang, Y.; Ren, C.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Z. Optimal Combination of Predictors and Algorithms for Forest Above-Ground Biomass Mapping from Sentinel and SRTM Data. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Bao, W.; Wang, X.; Song, Y.; Liao, T.; Xu, X.; Guo, M. Estimating Aboveground Biomass of Boreal forests in Northern China using multiple datasets. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 4408410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, C.; Li, M.; Liu, Z. Influence of Variable Selection and Forest Type on Forest Aboveground Biomass Estimation Using Machine Learning Algorithms. Forests 2019, 10, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Mura, M.; Zheng, X.; Chen, Q.; Wei, X.; Qiu, Y.; Li, M.; Ren, Y. More Accurately Estimating Aboveground Biomass in Tropical Forests with Complex Forest Structures and Regions of High-Aboveground Biomass. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2024, 129, e2023JG007864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Ye, Q.; Zhao, Q.; Li, Z.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, H.; Zhao, Z. Effects of Driving Factors on Forest Aboveground Biomass (AGB) in China’s Loess Plateau by Using Spatial Regression Models. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Dong, L.; Li, S.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Mao, Z.; Deng, L. Improving AGB estimations by integrating tree height and crown radius from multisource remote sensing. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0311642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Lei, J.; Huang, Y. Forest Aboveground Biomass Estimation Based on Unmanned Aerial Vehicle-Light Detection and Ranging and Machine Learning. Sensors 2024, 24, 7071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poley, L.G.; McDermid, G.J. A Systematic Review of the Factors Influencing the Estimation of Vegetation Aboveground Biomass Using Unmanned Aerial Systems. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Yu, Z.; Wang, S.; Wu, F.; Wen, K.; Qi, J.; Huang, H. Crown Structure Metrics to Generalize Aboveground Biomass Estimation Model Using Airborne Laser Scanning Data in National Park of Hainan Tropical Rainforest, China. Forests 2022, 13, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.D.; Yokoya, N.; Xia, J.; Ha, N.T.; Le, N.N.; Nguyen, T.T.T.; Dao, T.H.; Vu, T.T.P.; Pham, T.D.; Takeuchi, W. Comparison of Machine Learning Methods for Estimating Mangrove Above-Ground Biomass Using Multiple Source Remote Sensing Data in the Red River Delta Biosphere Reserve, Vietnam. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Wang, M.; Ma, M.; Lin, Y. Aboveground Tree Biomass Estimation of Sparse Subalpine Coniferous Forest with UAV Oblique Photography. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra-Hernández, J.; González-Ferreiro, E.; Monleón, V.J.; Faias, S.P.; Tomé, M.; Díaz-Varela, R.A. Use of Multi-Temporal UAV-Derived Imagery for Estimating Individual Tree Growth in Pinus pinea Stands. Forests 2017, 8, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainuddin, S.F.; Guljar, M.; Ankur, R.; Nagar, P.S.; Asok, S.V.; Sudhakar, R.C. Estimating Above-Ground Biomass of the Regional Forest Landscape of Northern Western Ghats Using Machine Learning Algorithms and Multi-sensor Remote Sensing Data. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 2024, 52, 885–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Anees, S.A.; Huang, Q.; Qin, X.; Qin, Z.; Fan, J.; Han, G.; Zhang, L.; Shafri, H.Z.M. Improving Forest Above-Ground Biomass Estimation by Integrating Individual Machine Learning Models. Forests 2024, 15, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, G.R.; Lhillips, P.O.; Baker, B.T. The importance of crown dimensions to improve tropical tree biomass estimates. Ecol. Appl. Publ. Ecol. Soc. Am. 2014, 24, 680–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Lei, P.; You, Q.; Tang, X.; Lai, X.; Chen, J.; You, H. Individual Tree Aboveground Biomass Estimation Based on UAV Stereo Images in a Eucalyptus Plantation. Forests 2023, 14, 1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaled, A.; Solomon, W.N.; Shelter, M.; Elhadi, A.; Byrne, M.J. Mapping eucalypts trees using high resolution multispectral images: A study comparing WorldView 2 vs. SPOT 7. Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Space Sci. 2020, 24, 333–342. [Google Scholar]

- Whelan, A.W.; Cannon, J.B.; Bigelow, S.W.; Rutledge, B.T.; Meador, A.J.S. Improving generalized models of forest structure in complex forest types using area- and voxel-based approaches from lidar. Remote Sens. Environ. 2023, 284, 113362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).