Abstract

Soil organic carbon (SOC) is a critical component of the soil carbon pool, significantly influencing soil fertility and forest ecosystem productivity. Eucalyptus grandis (Rose Gum), one of the most widely introduced and economically valuable fast-growing tree species worldwide, plays an indispensable role in pulpwood production, construction, and bioenergy, and is commonly established and managed in successive rotations in operational practice. Despite its importance, the effects of successive planting on SOC and its labile fractions in plantation soils remain poorly understood. In May 2017, a space-for-time substitution approach was employed to study the effects of successive planting of E. grandis plantations on SOC and its labile fractions, including dissolved organic carbon, light-fraction organic carbon, particulate organic carbon, microbial biomass carbon, and readily oxidizable carbon. The results indicated that the content of SOC and labile organic carbon (LOC) fractions declined concomitant with an increase in successive planting generations. Specifically, total SOC content significantly decreased from 12.63 g·kg−1 in the first-generation forest to 9.37 g·kg−1 in the third-generation forest. The contents of LOC fractions also showed a significant decrease from the first to the second generation, but the rate of this decline slowed in the third generation. The soil carbon pool management index (CPMI) decreased significantly from 100 in the control forest to 46.64 in the third-generation plantation. Redundancy analysis identified water-soluble nitrogen and total nitrogen as the principal common factors exerting influence over SOC and its labile fractions in E. grandis plantations. These findings indicate that successive planting of E. grandis in artificial forests primarily reduces SOC and LOC fractions by lowering soil nutrient content, leading to a decline in soil carbon pool quality. The findings of this study may help provide a scientific basis for the sustainable development of E. grandis plantations in this region.

1. Introduction

Forest soils play an important role in sequestering atmospheric CO2, storing at least three times as much carbon (C) as found in living plants [1]. The C stock in forest soils is critical in sustaining soil fertility and mediating global climate change [2], as even small changes can lead to significant variations in atmospheric CO2 levels [3]. Soil organic carbon (SOC) undergoes changes that are reflected not only in the total size of the carbon pool but also in the composition of its various fractions [4]. Among these, Soil labile organic carbon (LOC) is commonly quantified by dissolved organic carbon (DOC), light-fraction organic carbon (LFOC), microbial biomass carbon (MBC), readily oxidizable organic carbon (ROC), and particulate organic carbon (POC) [5]. These fractions are marked by high mobility, low stability, and pronounced susceptibility to oxidation and mineralization; although they constitute only a small proportion of total SOC, they play a pivotal role in regulating soil biogeochemical processes [6,7]. Owing to their rapid turnover, labile fractions respond to land-use change, climate warming, and management interventions (e.g., tillage, fertilization, and vegetation restoration) well in advance of more recalcitrant pools and are widely regarded as sensitive indicators of soil-health dynamics and key short-term drivers of carbon-cycle variability [8,9]. Hence, a comprehensive understanding of the dynamics of LOC fractions in forest soil is of paramount importance for the assessment of carbon sequestration and the long-term stability of the soil carbon pool [10].

As a key management practice for fast-growing, high-yield plantations, successive planting primarily affects SOC and LOC fractions by altering soil physicochemical properties and microbial activity [11]. The high nutrient uptake by trees in continuous cropping systems can result in soil nutrient depletion [12], which impedes plant growth and development and modifies microbial activity [13,14], thereby changing litterfall returns [15]. Concurrently, this process impacts the microbial fixation and transformation of organic carbon, ultimately modifying the content of soil organic carbon and its labile fractions [16]. However, the effects of successive planting on SOC and LOC fractions remain inconclusive, with studies reporting increases, decreases, or no significant change. For example, in eucalyptus plantations in the southern subtropical zone, SOC and LOC fractions decreased significantly following successive rotations [17]. In contrast, SOC content in Cunninghamia lanceolata plantations in the mid-subtropical zone initially increased and then declined with successive generations [18], whereas Pinus massoniana plantations showed significant increases in SOC content under successive rotations [19]. In addition, an eight-year study by Li et al. [20] reported no significant differences in SOC content among eucalyptus plantations across different rotation stages. The discrepancies in these results may be attributed to variations in climate, soil conditions, tree species, and rotation stages across the study areas. Despite this, the influence mechanism of successive planting on SOC and LOC fractions remains unclear.

The soil carbon pool management index (CPMI) serves as a comprehensive indicator reflecting both soil carbon dynamics and the overall quality of the soil carbon pool [21]. Higher CPMI values correspond to faster turnover rates of SOC, indicating greater susceptibility to microbial degradation and assimilation, and consequently, a higher quality carbon pool [22]. Compared with single-parameter indicators such as SOC concentration and stock, the CPMI provides a more integrative assessment of the dynamic changes in both the quantity and quality of the soil carbon pool following successive planting [23]. Currently, research concerning CPMI has primarily focused on agricultural systems. For instance, field experiments conducted by Wang et al. [24] in southern China revealed that the application of steel slag, biochar, or their combination significantly reduced CPMI values in early-season rice paddies compared with the control, suggesting that these practices may decrease soil carbon pool activity and impair its nutrient retention capacity. Conversely, research by Moharana et al. [25] in Rajasthan, India, demonstrated that, relative to uncultivated wasteland, land-use systems such as grassland cultivation, rice–wheat intercropping, citrus orchards, and agroforestry significantly increased CPMI. Among these, grassland cultivation yielded the highest CPMI, highlighting its potential to improve soil fertility and enhance carbon sequestration capacity. However, the effects of successive planting on the CPMI of forest soils have been rarely reported in the literature. Consequently, there is a clear need for further investigation in this area.

E. grandis is one of the world’s three major fast-growing tree species [26]. It is characterized by a tall, straight trunk, smooth bark, and elliptic or lanceolate leaves that contain volatile oils and emit a strong aromatic odor. The wood of E. grandis is rich in cellulose and has a moderate density [27,28]. Furthermore, its litter has a high carbon-to-nitrogen (C/N) ratio, which results in a slow decomposition rate in the soil [29]. E. grandis possesses significant economic value in the pulpwood, construction, and energy sectors and is often established through successive planting in forestry practice [30,31]. The species is characterized by a high nutrient requirement and yields litter of poor quality, resulting in limited nutrient return to the soil. This combination of high uptake and low return establishes E. grandis as a premier model system for studying the “successive planting obstacle” in plantation systems [32]. However, most studies on successive planting in E. grandis have focused on stand productivity and biodiversity—for example, Dai et al. [33] reported in southern China that tree growth increased with rotation number, whereas Xu et al. [34] found that successive rotations significantly reduced microbial community diversity and richness. By contrast, the responses of soil organic carbon—particularly its labile fractions—to successive rotations in E. grandis plantations remain insufficiently understood and warrant further investigation.

This study investigated E. grandis plantations in Qingshen County, Sichuan Province, China, and determined the contents of SOC and LOC fractions across different successive planting generations using a space-for-time substitution approach. The objectives of this study were to: (1) quantify the effects of different consecutive planting generations on the content of SOC and LOC fractions in Eucalyptus grandis plantations; (2) analyze the main factors influencing the impact of successive planting of Eucalyptus grandis on SOC and LOC fractions, in relation to soil physicochemical properties; and (3) provide scientific evidence to reveal the mechanisms through which successive planting of Eucalyptus grandis affects SOC and LOC fractions in plantation soils.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The study was performed in the northern part of Baiguo village in Xilong township, Qingshen county, Sichuan Province, China (29°77′–29°82′ N, 103°84′–103°92′ E). The site is located on the southwestern margin of the West Sichuan Plain, forming a transitional zone between the plain and the western Sichuan hills. The region has a mild and humid climate with distinct seasons and is classified as a subtropical mountain monsoon climate. The mean annual temperature is 17.1 °C, with an annual sunshine duration of 1182 h and a mean annual precipitation of approximately 1132 mm. The predominant soil type is yellow soil, with a depth exceeding 50 cm. The zonal forest community is subtropical evergreen broad-leaved forest, and the dominant tree species include E. grandis, C. camphora, Phoebe zhennan, Quercus acutissima, Liquidambar formosana and Pinus massoniana.

2.2. Establishment of Standard Plots

In May 2017, first-(I), second-(II), and third-generation (III) E. grandis plantations were selected within the study area. These plantations were established under comparable site conditions, planting methods, management practices, stand density, and age. Within each generation, three standard plots (20 m × 20 m) were established, with a minimum spacing of 50 m between plots (detailed characteristics are presented in Table 1). The first-generation plantation was established in 2010 on a clear-cut Pinus massoniana site, while the second- and third-generation plantations were established in 2010 on clear-cut sites of 8-year-old first- and second-generation Eucalyptus plantations, respectively. For all three generations, a basal fertilizer (2.00 kg farmyard manure + 0.25 kg urea per plant, applied in planting holes) was applied only once prior to planting, and seedlings were manually planted.

Table 1.

Standard plot conditions of E. grandis plantations of different generations.

2.3. Soil Sample Collection and Processing

In June 2017, five soil profiles were established in each standard plot following an “S”-shaped sampling pattern to better account for the inherent spatial variability of soil properties [35]. From each profile, soil samples were collected from the 0–20 cm layer and thoroughly mixed, after which they were divided into two portions. One portion was passed through a 2 mm sieve and refrigerated at 4 °C for the determination of DOC and MBC concentrations [36]. The other portion was air-dried, passed through 2 mm and 0.15 mm sieves, and subsequently used to determine soil chemical properties as well as the contents of SOC, ROC, LFOC and POC [36]. At the same time, undisturbed soil samples were collected using 100 cm3 cutting rings to measure soil bulk density, porosity, and moisture content.

2.4. Methods of Determination

Following the methods described in Soil Agrochemical Analysis [36], the contents of various carbon fractions were determined. SOC was measured by the potassium dichromate oxidation–external heating method. In this procedure, SOC was oxidized with potassium dichromate and concentrated sulfuric acid under external heating, and the residual oxidant was quantified by titration to back-calculate the SOC content. DOC was measured by a colorimetric method, where DOC was first extracted with water, then reacted with a strong oxidizing agent, and its concentration was quantified by measuring absorbance with a spectrophotometer. MBC was determined using the chloroform fumigation–extraction method. Soil microorganisms were lysed by chloroform fumigation, and the released organic carbon was extracted with a K2SO4 solution. The difference in extractable carbon between fumigated and non-fumigated samples was then converted to MBC content using an appropriate conversion factor. ROC was quantified by the potassium permanganate oxidation method, whereby ROC was oxidized and its content calculated based on the absorbance of the residual oxidant. LFOC was measured by first separating the light fraction from the soil and then oxidizing it with potassium dichromate and concentrated sulfuric acid under external heating; the amount of potassium dichromate consumed was used to calculate the LFOC content. Finally, POC was measured following the wet-sieving and size-fractionation method described by Cambardella et al. [37], with the organic carbon content of the isolated fractions determined using the potassium dichromate oxidation–external heating method.

Soil bulk density, total porosity, and moisture content were determined using the core method. Fresh soil was collected in a cutting ring and weighed. The soil was then oven-dried at 105 °C to a constant weight and reweighed to determine its dry mass. Bulk density was calculated as the dry mass divided by the ring volume. Soil moisture content was calculated as the ratio of water mass to dry soil mass. Total porosity was subsequently calculated from the measured bulk density and an assumed particle density. Soil pH was determined potentiometrically by measuring a soil–water suspension with a pH meter. Total nitrogen was determined using the semi-micro Kjeldahl method, where soil nitrogen was digested to ammonium and subsequently quantified by distillation and titration. Water-soluble nitrogen was measured using the alkali diffusion method, in which ammonia released from soil treated with an alkaline solution was quantified by acid titration. Total phosphorus was determined by the NaOH fusion-colorimetric method. Soil samples were fused with sodium hydroxide at high temperature to convert insoluble phosphorus minerals into soluble phosphates, and the phosphorus content in the resulting solution was measured colorimetrically. Available phosphorus was quantified by extracting soil with a sodium bicarbonate solution and determining the phosphorus content in the extract spectrophotometrically. For potassium analysis, available potassium was first extracted with a neutral ammonium acetate solution, while total potassium was released by acid digestion. The potassium concentrations in all clarified extracts were then determined using a flame photometer by comparison with standard solutions.

2.5. Calculation of the Soil Carbon Pool Management Index (CPMI)

Referring to the method of Blair et al. [38], the CPMI was used to evaluate the impact of successive planting on SOC sequestration. The calculation formula is as follows:

In the equations above, the carbon pool activity (CPA) is defined as the ratio of the labile carbon fraction (ROC) to the non-labile organic carbon fraction (calculated as SOC minus ROC) within the same generation of E. grandis plantation [38]. The carbon pool activity index (CPAI) is the ratio of CPA in a successive rotation to that of the first rotation (control), thereby reflecting changes in the relative proportion and dynamics of labile organic carbon [38]. Similarly, the carbon pool index (CPI) is defined as the ratio of total SOC content in a successive rotation to that of the control, reflecting relative differences in total SOC abundance [38]. The variables used in these calculations are defined as follows: CPAL and SOCL denote the carbon pool activity and SOC content, respectively, after successive planting; while CPACK and SOCCK represent the corresponding values for the control (first-rotation) forest.

2.6. Statistical Analyses

Data were processed using Excel 2019 and SPSS 25.0, and figures were generated with Origin Pro 2024. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) combined with the least significant difference (LSD) test was applied to evaluate the effects of successive rotations on soil physicochemical properties, SOC and labile carbon fractions, and to test for significant differences among treatments, with the significance threshold set at p = 0.05. Redundancy analysis (RDA) was performed using Canoco 5.0. Prior to RDA, variance inflation factor (VIF) analysis was employed to examine multicollinearity among parameters. Variables exhibiting strong correlations with others (VIF > 10) in the initial analysis were excluded, and the remaining variables were used for subsequent RDA.

3. Results

3.1. Soil Organic Carbon and Labile Carbon Fractions

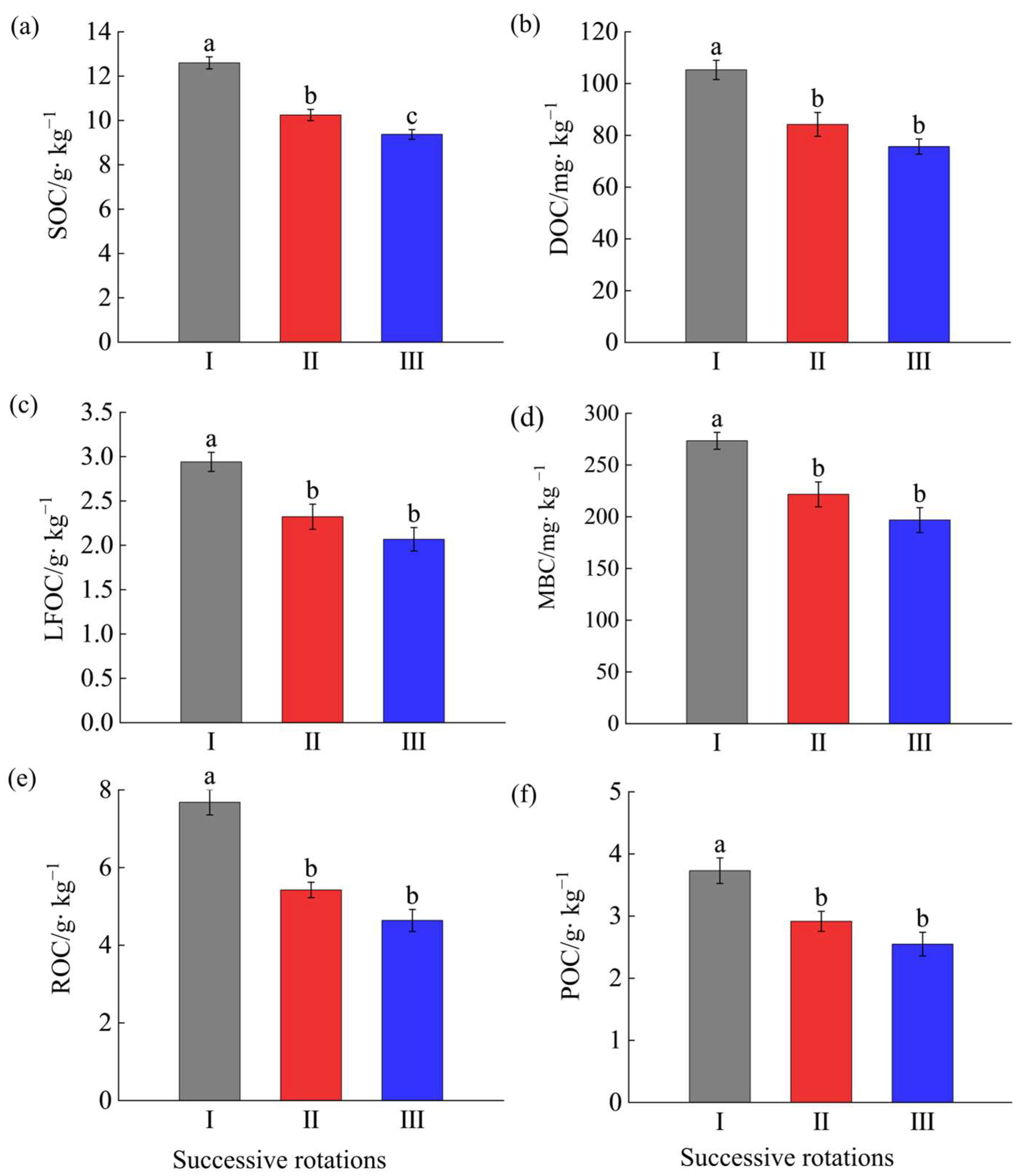

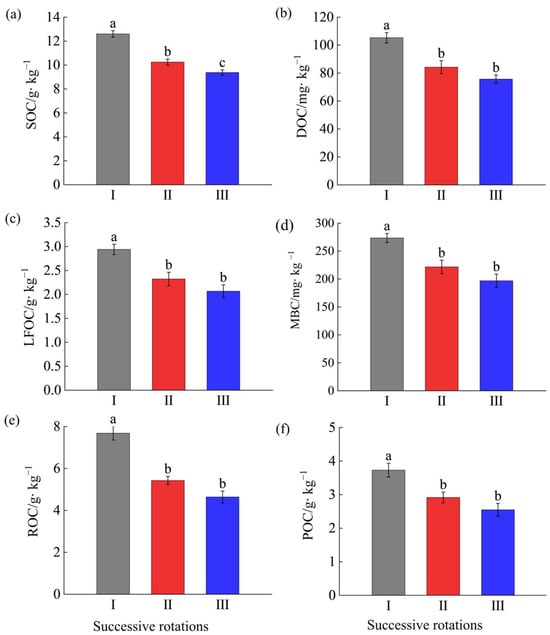

As shown in Figure 1a, compared with the first- generation Eucalyptus plantation, SOC in the second and third generations declined significantly by 18.85% and 25.82%, respectively, and the third generation was a significant 10% lower than the second generation (p < 0.05). Figure 1b–f illustrate that, relative to the first generation, soil DOC content in the second- and third-generation plantations decreased significantly (p < 0.05) by 20.01% and 28.16%, LFOC by 21.09% and 29.60%, MBC by 19.93% and 28.02%, ROC by 29.25% and 14.95%, and POC by 22.32% and 31.46%, respectively. Notably, although the contents of all labile organic carbon fractions in the third-generation E. grandis plantations were lower than those in the second generation, the differences were not statistically significant. From the above, the contents of SOC and LOC fractions show a declining trend with increasing successive rotations of E. grandis.

Figure 1.

Content of soil organic carbon and its labile fractions of Eucalyptus grandis plantations of different successive rotations. Subfigures (a–f) present the contents of SOC, DOC, LFOC, MBC, ROC, and POC in different generations, respectively. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05). SOC: soil organic carbon; DOC: dissolved organic carbon; LFOC: light fraction organic carbon; MBC: microbial biomass carbon; ROC: readily oxidizable organic carbon; POC: particulate organic carbon. I: The first generation plantations. II: The second generation plantations. III: The third generation plantations. The same below.

3.2. Physical and Chemical Properties

As shown in Table 2, soil capillary porosity, maximum water-holding capacity, pH, total nitrogen, water-soluble nitrogen, total phosphorus, available phosphorus, and available potassium were significantly lower (p < 0.05) in the second- and third-rotation Eucalyptus plantations than in the first rotation. Furthermore, the third rotation exhibited significantly lower (p < 0.05) non-capillary (air-filled) porosity, capillary porosity, maximum water-holding capacity, total phosphorus, and total potassium compared with the second rotation. Soil bulk density tended to increase with successive rotations, although the differences were not statistically significant. These results indicate that continuous cropping of E. grandis has significant adverse effects on soil physicochemical properties, leading to a gradual reduction in nutrient content and increased soil compaction.

Table 2.

Difference in physicochemical properties of E. grandis plantation soils across three successive planting generations.

3.3. Soil Carbon Pool Management Index

As shown in Table 3, with increasing rotation cycles, all indicators that collectively reflect the health of the soil carbon pool—including carbon pool lability, the lability index, the carbon pool index, and the carbon pool management index (CPMI)—exhibited significant (p < 0.05) declining trends. Among these, the CPMI, as the core evaluation metric, showed the sharpest decline. Compared to the first rotation, the CPMI in the second and third rotations decreased by 40.64% and 53.36%, respectively. The increase in the magnitude of decline from the second to the third rotation clearly indicates that the negative effects of successive E. grandis cultivation on soil carbon pool quality are cumulative and progressively exacerbating. This suggests that successive planting of E. grandis not only reduces the total amount of soil organic carbon but also markedly degrades the quality of the soil carbon pool.

Table 3.

Difference in soil carbon pool management index of E. grandis plantation across three successive planting generations.

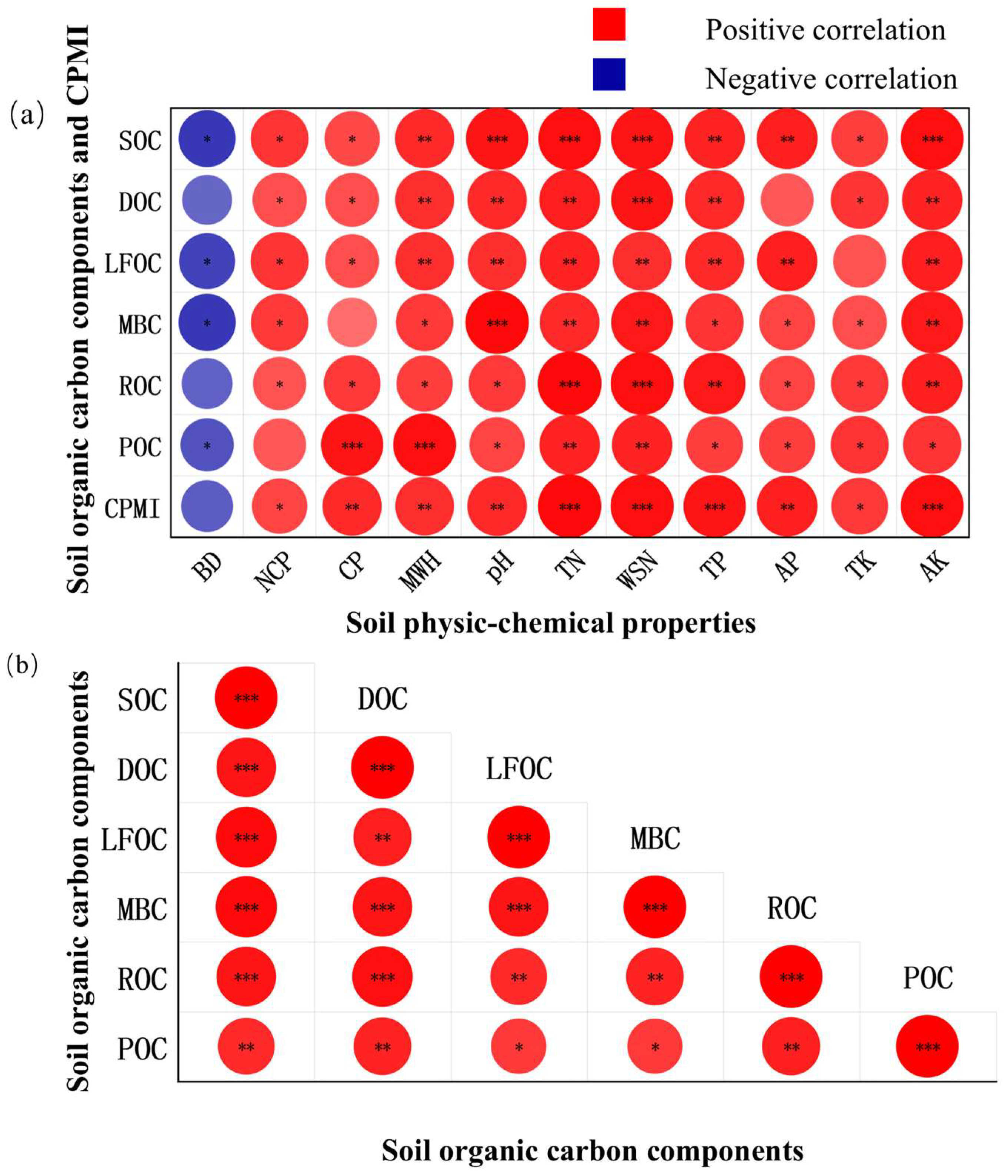

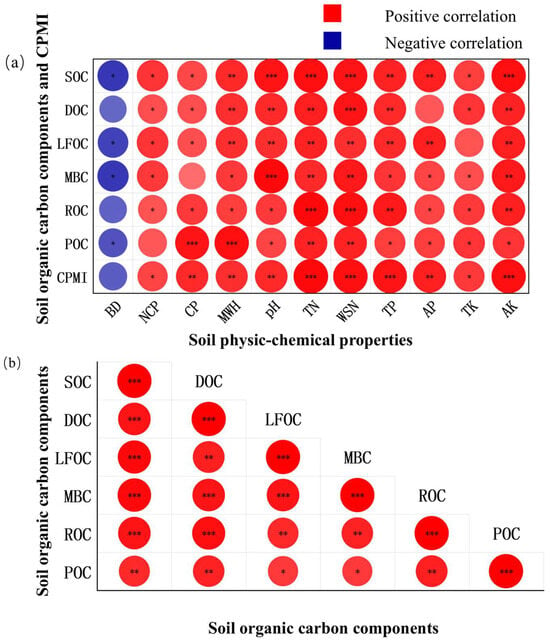

3.4. Correlation Analysis

Pearson’s correlation analysis (Figure 2) revealed that SOC, DOC, LFOC, MBC, ROC, and POC were all highly positively correlated with total nitrogen and water-soluble nitrogen (p < 0.01). SOC, DOC, LFOC, MBC, and ROC were significantly positively correlated with available potassium (p < 0.01); SOC, DOC, LFOC, and POC were significantly positively correlated with maximum water-holding capacity (p < 0.01); SOC, DOC, LFOC, and MBC were significantly positively correlated with soil pH (p < 0.01); and SOC, DOC, LFOC, and ROC were significantly positively correlated with total phosphorus (p < 0.01). In addition, SOC and LFOC showed highly significant positive correlations with available phosphorus (p < 0.01), while POC was significantly positively correlated with capillary porosity (p < 0.01). Moreover, DOC, LFOC, MBC, ROC, and POC were all strongly positively correlated with SOC (p < 0.01). The soil carbon pool management index exhibited highly significant positive correlations with capillary porosity, maximum water-holding capacity, soil pH, total nitrogen, water-soluble nitrogen, total phosphorus, available phosphorus, and available potassium (p < 0.01).

Figure 2.

Correlation analysis among variables. Subfigure (a) illustrates the correlations between soil organic carbon fractions and soil physicochemical properties, while Subfigure (b) illustrates the correlations among the soil organic carbon fractions. The darker the color in the figure indicates a stronger correlation. * indicated significant correlation at p < 0.05; ** indicated highly significant correlation at p < 0.01; *** indicated very highly significant correlation at p < 0.001. BD: bulk density; NCP: non-capillary (air-filled) porosity; CP: capillary porosity; MWH: maximum water-holding capacity; pH: soil pH; TN: total nitrogen; WSN: water-soluble nitrogen; TP: total phosphorus; AP: available phosphorus; TK: total potassium; AK: available potassium; CPMI: carbon pool management index. The same below.

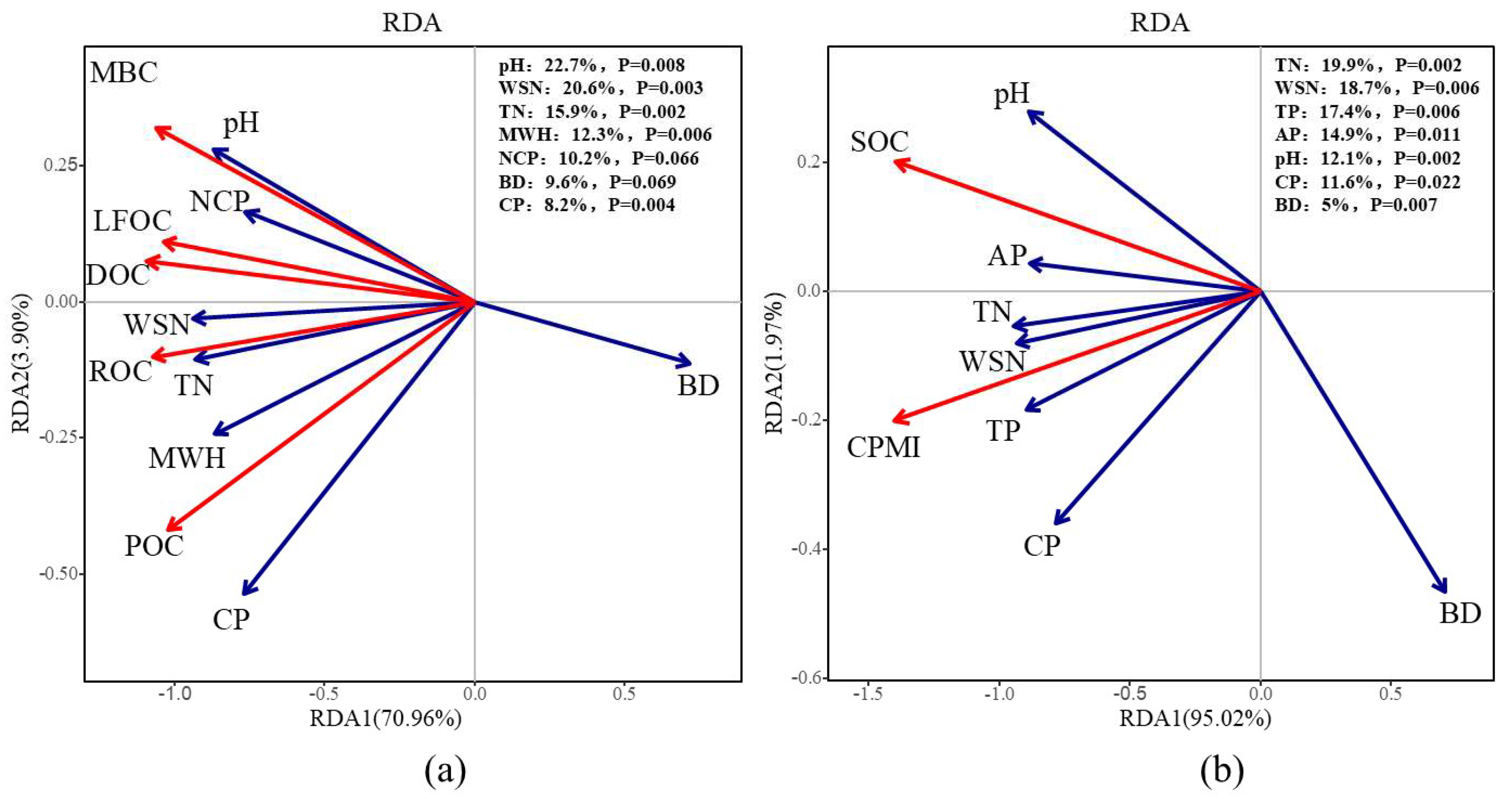

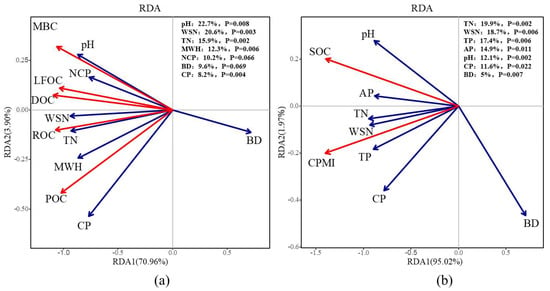

The results of the redundancy analysis (Figure 3) indicated that soil pH, water-soluble nitrogen, and total nitrogen were the primary factors significantly influencing soil LOC fractions, explaining 22.7%, 20.61%, and 15.68% of the variation, respectively. For SOC and CPMI, the significant factors were total nitrogen, water-soluble nitrogen, and total phosphorus, with explanatory powers of 19.91%, 18.66%, and 17.37%, respectively. In summary, soil nutrients emerged as the key drivers influencing the soil carbon pool during the continuous cropping of E. grandis.

Figure 3.

Redundancy analysis (RDA) of soil organic carbon and active carbon components and soil factors in E. grandis plantations of different successive generations. Subfigure (a) presents the results of the RDA between soil active carbon components and soil physicochemical properties, while Subfigure (b) presents the RDA results for soil organic carbon, the carbon pool management index, and soil physicochemical properties.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Influence of E. grandis Successive Planting on Soil Organic Carbon and Its Labile Fractions

Overall, our results showed that the content of soil LOC fractions declined significantly across successive rotations of E. grandis (Figure 2), aligning with the findings of Zhang et al. [39]. This is mainly related to changes in soil nutrient availability, pH, and moisture conditions.

We found that the contents of soil nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium decreased with increasing generations of successive E. grandis planting (Table 2). This may be attributed to the rapid growth of E. grandis, which leads to a high uptake of soil nutrients [40]. Furthermore, its litter has a high carbon-to-nitrogen (C/N) ratio and typically decomposes slowly [41], and the removal of all aboveground biomass at harvest prevents the effective return of nutrients to the soil [42]. Therefore, in the absence of exogenous nutrient supplementation (e.g., fertilization), successive planting leads to soil nutrient depletion. To cope with this challenge, microbes initiate a key ecological adaptation strategy—nutrient mining [43]. This strategy involves secreting large amounts of extracellular enzymes to accelerate the decomposition of soil organic matter (SOM), thereby mobilizing the mineral nutrients required by plants and themselves to alleviate metabolic limitations [44,45,46]. However, this process also results in a significant loss of soil LOC fractions.

Specifically, as the most readily available carbon source for direct microbial utilization in the soil solution, DOC is rapidly consumed as an energy source under the drive of nutrient mining, leading to its decrease in content [47]. LFOC and POC are primarily derived from partially decomposed plant residues [48,49]. A decline in microbial activity disrupts the SOM decomposition chain, reducing the formation of new LFOC and POC; concurrently, nutrient mining accelerates the consumption of existing stocks, collectively causing their content to decrease. For MBC, soil nutrient limitation directly suppresses microbial activity and reduces their growth and reproduction rates [50]; simultaneously, driven by nutrient mining, microbes may decompose their own biomass to provide energy, causing the MBC content to show a declining trend [51]. ROC, a key component of the labile carbon pool, encompasses most of the active fractions from DOC, LFOC, MBC, and POC [52]. Therefore, the reduction in the content of these aforementioned components also leads to a decrease in soil ROC content. Correlation analysis showed that the various LOC fractions were significantly positively correlated with soil N, P, and K (Figure 2). Redundancy analysis further revealed that soil total nitrogen and water-soluble nitrogen were the primary regulatory factors influencing the LOC fractions (Figure 3), which is consistent with the findings of Zhong et al. [53]. This indicates that continuous E. grandis cropping primarily reduces the accumulation of LOC fractions by depleting soil nutrient content.

Furthermore, we also found that successive planting of E. grandis reduced soil pH and moisture content (Table 2). Monoculture planting of tree species in artificial forests leads to soil acidification [54]. This, in turn, suppresses microbial activity, thereby reducing the MBC content in the soil. The decrease in microbial activity also limits the decomposition of litter, leading to a reduction in the content of POC and LFOC, which mainly originate from partially decomposed litter [48]. The high water consumption of E. grandis during its growth reduces soil moisture content, worsening the soil water conditions [55]. DOC is a water-soluble organic carbon fraction, and its migration and transformation are highly dependent on soil moisture conditions [56]. The decrease in water availability restricts the dissolution and leaching of organic matter [57], thereby hindering the release of DOC from litter or humus [58]. Correlation analysis indicated that the LOC fractions in soil were significantly or highly positively correlated with soil pH and the maximum water-holding capacity (Figure 2). This result is similar to that reported by Zhang et al. for E. grandis plantations [59]. This suggests that the reduction in soil pH and the deterioration of water conditions during the successive planting of E. grandis lead to a decrease in the content of LOC fractions in the soil.

In this study, the contents of LOC fractions in the second-generation forest were all significantly lower than those in the first-generation forest (Figure 1). However, this declining trend leveled off in the third-generation forest (Figure 1). This is because during the transition from the first- to the second-generation forest, substantial amounts of labile organic matter remained in the soil for microbial utilization. Subsequently, in the second- and subsequent generations, this labile organic matter was substantially depleted and became less available for further decomposition, leading to a comparatively smaller loss of LOC fractions.

We found that the content of SOC significantly decreased with the increasing number of E. grandis replanting cycles (Figure 1), which is consistent with the findings of Santos et al. [60]. This decline may be attributed to the reduction in the content of LOC fractions, which are an essential component of SOC, leading to an overall decrease in SOC levels. Correlation analysis revealed a highly significant positive correlation between SOC and all LOC fractions in the soil (Figure 2). This suggests that the reduction in SOC content is the result of the combined decrease in the levels of various LOC fractions.

4.2. The Influence of Successive Planting of E. grandis on the Soil Carbon Pool Management Index

The CPMI serves as a comprehensive indicator for evaluating soil carbon dynamics. By quantifying the ratio between labile and recalcitrant carbon fractions, as well as their deviations from reference conditions (e.g., natural vegetation, undisturbed soils, or specific management baselines), CPMI provides an integrative framework to assess the effects of management practices [61]. This approach enables a more precise evaluation of how different management strategies influence the stability, turnover rate, and long-term sustainability of soil carbon pools. This study indicated that successive planting of E. grandis plantations significantly reduced the soil carbon pool management index. This reduction was primarily due to the deterioration of soil physicochemical properties and the decline in microbial activity, which together decreased the accumulation of SOC and its labile fractions. The reduction in these components diminished soil carbon pool activity, leading to corresponding declines in the carbon pool activity index and carbon pool index. Correlation analysis showed that the soil carbon pool management index was strongly positively correlated with soil nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium contents, as well as with soil pH, maximum water-holding capacity, and capillary porosity. Redundancy analysis further revealed that total nitrogen, water-soluble nitrogen, total phosphorus, available phosphorus, pH, capillary porosity, and bulk density explained 19.9%, 18.7%, 17.4%, 14.9%, 12.1%, 11.6%, and 5.0% of the variation in CPMI, respectively (Figure 3). These findings indicate that successive planting of E. grandis reduces the soil carbon pool management index by altering soil physicochemical properties, ultimately resulting in a significant decline in soil quality. Therefore, during successive planting of E. grandis, timely fertilization should be applied to replenish soil nutrients, and the introduction of suitable tree species for rotation should also be considered to maintain soil quality.

5. Conclusions

Successive planting of E. grandis significantly alters soil physicochemical properties, reduces the contents of SOC and its labile fractions, degrades soil fertility and structure, and consequently leads to a significant decline in soil carbon pool quality. The primary cause of this outcome is the soil nutrient depletion induced by successive planting. Soil total nitrogen and water-soluble nitrogen are the key co-factors influencing SOC and its labile fractions during continuous E. grandis cultivation. Therefore, during the cultivation process, one strategy is to increase fertilizer application, particularly nitrogen, to maintain soil nutrient levels. Alternatively, a rotational cropping system with nitrogen-fixing tree species could be considered to improve soil quality. For instance, in the study area, species such as Robinia pseudoacacia, Alnus spp., and Coriaria nepalensis could be used for rotation. This would enhance the soil’s carbon sequestration capacity and promote the sustainable development of E. grandis plantations.

By employing the space-for-time substitution method, this study efficiently revealed the evolutionary trends of the long-term process of continuous E. grandis cropping, providing an important basis for evaluating its ecological effects. However, this method has certain limitations, as it is difficult to completely exclude the interference from spatial heterogeneity of initial soil conditions among different plots. In inferring causality, its accuracy is weaker than that of true long-term, fixed-location experiments. Therefore, future research could consider establishing long-term, fixed monitoring plots and designing experiments under different environmental backgrounds. Additionally, the response mechanisms of soil carbon fractions to successive E. grandis planting under conditions of fertilization and rotation should be further investigated, in order to more comprehensively understand the impact of successive E. grandis planting on soil carbon cycling.

Author Contributions

Data curation, Z.Z. and C.H.; methodology, Z.Z.; software, Z.Z.; formal analysis, Z.Z.; visualization, Z.Z.; writing—original draft, Z.Z.; investigation, J.T. and X.L.; Validation, R.W., Z.L., A.S., X.Z. and S.W.; Conceptualization, J.H., S.Z. and C.H.; writing—review and editing, J.H., S.Z. and C.H.; funding acquisition, S.Z.; supervision, C.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32401425), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2024M763192), the Natural Science Foundation of Sichuan Province (2025ZNSFSC0266, 2025ZNSFSC1033, and 2024NSFSC1191).

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Authors Jingxing Tan and Xiao Luo are employed by the company Sichuan Forestry Survey, Design and Research Institute Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Carvalhais, N.; Forkel, M.; Khomik, M.; Bellarby, J.; Jung, M.; Migliavacca, M.; Mu, M.Q.; Saatchi, S.; Santoro, M.; Thurner, M.; et al. Global covariation of carbon turnover times with climate in terrestrial ecosystems. Nature 2014, 514, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Soil carbon sequestration impacts on global climate change and food security. Science 2004, 304, 1623–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Managing soils for negative feedback to climate change and positive impact on food and nutritional security. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2020, 66, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C.; Tan, Q.Y.; Liu, G.B.; Xu, M.X. Forest thinning increases soil carbon stocks in China. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 482, 118812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Cui, S.; Liang, G.P.; Zhang, Q.P. Microbial-derived carbon components are critical for enhancing soil organic carbon in no-tillage croplands: A global perspective. Soil Tillage Res. 2021, 205, 104758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.; Kleber, M. The contentious nature of soil organic matter. Nature 2015, 528, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wen, Y.C.; Li, X.H.; Li, Y.T.; Yang, X.D.; Lin, Z.; Song, Z.Z.; Cooper, J.M.; Zhao, B.Q. Soil labile organic carbon fractions and soil organic carbon stocks as affected by long-term organic and mineral fertilization regimes in the North China Plain. Soil Tillage Res. 2018, 175, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesmeier, M.; Urbanski, L.; Hobley, E.; Lang, B.; von Lützow, M.; Marin-Spiotta, E.; van Wesemael, B.; Rabot, E.; Liess, M.; Garcia-Franco, N.; et al. Soil organic carbon storage as a key function of soils-A review of drivers and indicators at various scales. Geoderma 2019, 333, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotrufo, M.F.; Wallenstein, M.D.; Boot, C.M.; Denef, K.; Paul, E. The Microbial Efficiency-Matrix Stabilization (MEMS) framework integrates plant litter decomposition with soil organic matter stabilization: Do labile plant inputs form stable soil organic matter? Glob. Chang. Biol. 2013, 19, 988–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, H.J.; Liu, D.Y.; Liao, X.; Miao, Y.C.; Li, Y.; Li, J.J.; Yuan, J.J.; Chen, Z.M.; Ding, W.X. Field-aged biochar enhances soil organic carbon by increasing recalcitrant organic carbon fractions and making microbial communities more conducive to carbon sequestration. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2022, 340, 108177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, R.L.; Wang, C.; Cheng, F.; Ma, X.F.; Cheng, X.; He, B.; Chen, D. Effects of Successive Planting of Eucalyptus on Soil Physicochemical Properties 1–3 Generations after Converting Masson Pine Forests into Eucalyptus Plantations. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2023, 32, 4503–4514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.H.; Wang, Y.C.; Li, J.J.; Cai, Y.H.; Hu, M.Y.; Lin, W.X.; Wu, Z.Y. Effects of continuous monoculture on rhizosphere soil nutrients, growth, physiological characteristics, hormone metabolome of Casuarina equisetifolia and their interaction analysis. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhang, C.C.; Deng, J.; Zhang, B.W.; Chen, F.S.; Chen, W.; Fang, X.M.; Li, J.J.; Zu, K.L.; Bu, W.S. Response of tree growth to nutrient addition is size dependent in a subtropical forest. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 923, 171501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.X.; Moorhead, D.L.; Guo, X.B.; Peng, S.S.; Wang, Y.Q.; Zhang, X.C.; Fang, L.C. Stoichiometric models of microbial metabolic limitation in soil systems. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2021, 30, 2297–2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, M.; Ukonmaanaho, L.; Johnson, J.; Benham, S.; Vesterdal, L.; Novotny, R.; Verstraeten, A.; Lundin, L.; Thimonier, A.; Michopoulos, P.; et al. Quantifying carbon and nutrient input from litterfall in European forests using field observations and modeling. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2018, 32, 784–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.J.; Huo, X.M.; Ma, R.H.; Zhai, J.; Zhang, H.Y.; Guo, J.C.; Hu, Z.H.; Yang, B. Enhance soil organic carbon accumulation in degraded poplar forests via microbial activation: Stump grafting transformed pure forests surpassing mixed forests. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2025, 234, 121541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Silong, W.; Zongwei, F. Stability of soil organic carbon changes in successive rotations of Chinese ffir (Cunninghamia lanceolata (Lamb.) Hook) plantations. J. Environ. Sci. 2009, 21, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.C.; Yang, J.Y.; Zeng, S.C.; Wu, D.M.; Jacobs, D.F.; Sloan, J.L. Soil pH, organic matter, and nutrient content change with the continuous cropping of Cunninghamia lanceolata plantations in South China. J. Soils Sediment. 2017, 17, 2230–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Li, Q.; Zou, S.; Bai, X.L.; Li, W.J.; Chen, Y. Dynamic changes of soil microbial communities during the afforestation of Pinus armandii in a karst region of Southwest China. Microb. Ecol. 2024, 87, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.Q.; Ye, D.; Liang, H.W.; Zhu, H.G.; Qin, L.; Zhu, Y.L.; Wen, Y.G. Effects of successive rotation regimes on carbon stocks in eucalyptus plantations in subtropical China measured over a full rotation. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.Q.; Hu, N.J.; Zhang, Z.W.; Xu, J.L.; Tao, B.R.; Meng, Y.L. Short-term responses of soil organic carbon and carbon pool management index to different annual straw return rates in a rice–wheat cropping system. Catena 2015, 135, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.L.; Fu, L.C.; AO, G.K.; Ji, C.J.; Zeng, H.; Zhu, B. Climate, plant and microorganisms jointly influence soil organic matter fractions in temperate grasslands. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 958, 178133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, C.; Saba, T.; Wang, J.Y.; Hui, W.K.; Liu, W.L.; Fan, J.T.; Wu, J.H.; Liu, X.Z.; Gong, W. Conversion effects of farmland to Zanthoxylum bungeanum plantations on soil organic carbon mineralization in the arid valley of the upper reaches of Yangtze River, China. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.Q.; Lai, D.Y.F.; Abid, A.A.; Neogi, S.; Xu, X.P.; Wang, C. Effects of steel slag and biochar incorporation on active soil organic carbon pools in a subtropical paddy field. Agronomy 2018, 8, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moharana, P.C.; Meena, R.L.; Nogiya, M.; Jena, R.K.; Sharma, G.K.; Sahoo, S.; Jha, P.K.; Aditi, K.; Vara Prasad, P.V. Impacts of Land Use on Pools and Indices of Soil Organic Carbon and Nitrogen in the Ghaggar Flood Plains of Arid India. Land 2022, 11, 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Lai, D.Y.F.; Wang, C.; Pan, T.; Zeng, C. Effects of rice straw incorporation on active soil organic carbon pools in a subtropical paddy field. Soil Tillage Res. 2015, 152, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutt, D.; Tyagi, C.H. Comparison of various eucalyptus species for their morphological, chemical, pulp and paper making characteristics. Indian J. Chem. Technol. 2011, 18, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguayo, M.G.; Quintupill, L.; Castillo, R.; Baeza, J.; Freer, J.; Mendonça, R.T. Determination of differences in anatomical and chemical characteristics of tension and opposite wood of 8-year old Eucalyptus globulus. Maderas-Cienc. Tecnol. 2010, 12, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.H.; Hu, C.; Zhang, Z.H.; Peng, X.B.; Hu, G. Ecological stoichiometric characteristics of leaf, litter, and soil in Eucalyptus plantations with different ages in subtropical, South China. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2023, 21, 3755–3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nistal França, F.J.; Filgueira Amorim França, T.S.; Vidaurre, G.B. Effect of growth stress and interlocked grain on splitting of seven different hybrid clones of Eucalyptus grandis × Eucalyptus urophylla wood. Holzforschung 2020, 74, 917–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Arnold, R.J.; Wu, Z.; Chen, S.; DU, A.P. Advances in eucalypt research in China. Front. Agric. Sci. Eng. 2017, 4, 380–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.T.; Ling, A.Y.; Zhu, L.Y.; Wu, Q.Z.; Huang, K.T.; Zhang, D.X.; Wang, Z.Y.; Qin, Z.Y.; Wu, L.C.; Tang, J. Co-occurrence networks dominated by rare and abundant fungal species influence the potential function of fungal communities in Eucalyptus urophylla plantations under successive planting. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2025, 215, 106421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.L.; Wang, T.H.; Wei, P.L.; Fu, Y.L. Effects of successive planting of Eucalyptus plantations on tree growth and soil quality. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Li, C.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, W.; Wu, L.; Du, A. The shifts in soil microbial community and association network induced by successive planting of Eucalyptus plantations. For. Ecol. Manag. 2022, 505, 119877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.K. Analytical Methods for Soil Agricultural Chemistry; Agricultural Science and Technology Press: Beijing, China, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, S.D. Soil Agro-Chemical Analysis, 3rd ed.; Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cambardella, C.A.; Elliott, E.T. Particulate soil organic-matter changes across a grassland cultivation sequence. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1992, 56, 777–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, G.J.; Lefroy, R.D.; Lisle, L. Soil carbon fractions based on their degree of oxidation, and the development of a carbon management index for agricultural systems. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 1995, 46, 1459–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zheng, H.; Chen, F.L.; Ouyang, Z.Y.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.F.; Lan, J.; Fu, M.; Xiang, X.W. Changes in soil quality after converting Pinus to Eucalyptus plantations in southern China. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2015, 6, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi, G.; Meir, P.; Cromer, R.; Tompkins, D.; Jarvis, P.G. Photosynthetic parameters in seedlings of Eucalyptus grandis as affected by rate of nitrogen supply. Plant Cell Environ. 2002, 25, 1677–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, S.; Huang, Y. Leaf litter decomposition in the pure and mixed plantations of Cunninghamia lanceolata and Michelia macclurei in subtropical China. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2009, 45, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Wu, F.Z.; Peng, C.H.; Peñuelas, J.; Vallicrosa, H.; Sardans, J.; Peng, Y.; Wu, Q.Q.; Li, Z.M.; Hedenec, P.; et al. Global spectra of plant litter carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus concentrations and returning amounts. J. Ecol. 2024, 112, 717–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.L.; Cui, Y.X.; Xia, Z.Q.; Zhang, X.H.; Zhou, C.R.; An, S.Y.; Zhu, M.M.; Gao, Y.; Yu, W.T.; Ma, Q. Microbial nutrient limitations limit carbon sequestration but promote nitrogen and phosphorus cycling: A case study in an agroecosystem with long-term straw return. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 870, 161865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyte, K.Z.; Schluter, J.; Foster, K.R. The ecology of the microbiome: Networks, competition, and stability. Science 2015, 350, 663–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinsabaugh, R.L.; Manzoni, S.; Moorhead, D.L.; Richter, A. Carbon use efficiency of microbial communities: Stoichiometry, methodology and modelling. Ecol. Lett. 2013, 16, 930–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.S.; Zhu, W.L.; Xu, F.Y.; Du, J.L.; Tian, X.H.; Shi, J.L.; Wei, G.H. Organic amendments affect soil organic carbon sequestration and fractions in fields with long-term contrasting nitrogen applications. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2021, 322, 107643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentges, A.; Feenders, C.; Deutsch, C.; Blasius, B.; Dittmar, T. Long-term stability of marine dissolved organic carbon emerges from a neutral network of compounds and microbes. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 17780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarino, S.H.; Pinto, P.; Jackson, R.B.; Piñeiro, G. Plant rhizodeposition: A key factor for soil organic matter formation in stable fractions. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabd3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janzen, H.H.; Campbell, C.A.; Brandt, S.A.; Lafond, G.P.; Townley-Smith, T. Light-fraction organic matter in soils from long-term crop rotations. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1992, 56, 1799–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, P.P.; Wang, C.Q.; Wanek, W.; Yang, X.Y.; Hu, P.L.; Wang, K.L.; Li, D.J. Soil microbial phosphorus limitation constrains carbon use efficiency in subtropical forests. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2025, 210, 109937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.L.; Cui, Y.X.; Moorhead, D.L.; Dijkstra, F.A.; Sun, L.F.; Xia, Z.Q.; Gao, Y.; Ma, Q.; Yu, W.T. Phosphorus limitation regulates the responses of microbial carbon metabolism to long-term combined additions of nitrogen and phosphorus in a cropland. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2025, 200, 109614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Lützow, M.; Kögel-Knabner, I.; Ekschmitt, K.; Flessa, H.; Guggenberger, G.; Matzner, E.; Marschner, B. SOM fractionation methods: Relevance to functional pools and to stabilization mechanisms. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2007, 39, 2183–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.D.; Pan, P.; Xiao, S.H.; Ouyang, X.Z. Influence of Eucalyptus plantation on soil organic carbon and its fractions in severely degraded soil in Leizhou Peninsula, China. Forests 2022, 13, 1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, G.Q.; Wu, L.H.; Qu, X.Y.; Dai, L.L.; Ye, Y.Q.; Xu, S.S.; Wu, C.; Chen, Y. Correlation between changes in soil properties and microbial diversity driven by different management in artificial Chinese fir (Cunninghamia lanceolata (Lamb.) Hook.) plantations. Forests 2023, 14, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dye, P. A review of changing perspectives on Eucalyptus water-use in South Africa. For. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 301, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.Y.; Yoshitake, S.; Iimura, Y.; Asai, C.; Ohtsuka, T. Dissolved organic carbon (DOC) input to the soil: DOC fluxes and their partitions during the growing season in a cool-temperate broad-leaved deciduous forest, central Japan. Ecol. Res. 2017, 32, 713–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.C.; Wang, L.L.; Fu, Y.; Lin, D.G.; Hou, M.R.; Li, X.D.; Hu, D.D.; Wang, Z.H. Transformation of soil organic matter subjected to environmental disturbance and preservation of organic matter bound to soil minerals: A review. J. Soils Sediment. 2023, 23, 1485–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Dai, Q.H.; Yan, Y.J.; He, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, Z.Y.; Meng, W.P.; Wang, C.Y. Litter input promoted dissolved organic carbon migration in karst soil. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2024, 202, 105606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.H.; Zhu, K.X.; Zhuang, S.Y.; Wang, H.L.; Cao, J.Z. Soil Nutrient, Enzyme Activity, and Microbial Community Characteristics of E. urophylla × E. grandis Plantations in a Chronosequence. Forests 2024, 15, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.S.; Oliveira, F.C.C.; Ferreira, G.W.D.; Ferreira, M.A.; Araújo, E.F.; Silva, I.R. Carbon and nitrogen dynamics in soil organic matter fractions following eucalypt afforestation in southern Brazilian grasslands (Pampas). Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2020, 301, 106979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Zhang, Y.G.; Long, J.M.; Luo, K.; Huang, Z.G. Responses of soil labile organic carbon stocks and the carbon pool management index to different vegetation restoration types in the Danxia landform region of southwest China. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0318195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).