Abstract

Unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV)-captured RGB imagery, with high spatial resolution and ease of acquisition, is increasingly applied to individual tree crown detection (ITCD). However, ITCD in dense subtropical forests remains challenging due to overlapping crowns, variable crown size, and similar spectral responses between neighbouring crowns. This paper investigates to what extent the ITCD accuracy can be improved by using dual-seasonal UAV-captured RGB imagery in different subtropical forest types: urban broadleaved, planted coniferous, and mixed coniferous–broadleaved forests. A modified YOLOv8 model was employed to fuse the features extracted from dual-seasonal images and perform the ITCD task. Results show that dual-seasonal imagery consistently outperformed single-seasonal datasets, with the greatest improvement in mixed forests, where the F1 score range increased from 56.3%–60.7% (single-seasonal datasets) to 69.1%–74.5% (dual-seasonal datasets) and the AP value range increased from 57.2%–61.5% to 70.1%–72.8%. Furthermore, performance fluctuations were smaller for dual-seasonal datasets than for single-seasonal datasets. Finally, our experiments demonstrate that the modified YOLOv8 model, which fuses features extracted from dual-seasonal images within a dual-branch module, outperformed both the original YOLOv8 model with channel-wise stacked dual-seasonal inputs and the Faster R-CNN model with a dual-branch module. The experimental results confirm the advantages of using dual-seasonal imagery for ITCD, as well as the critical role of model feature extraction and fusion strategies in enhancing ITCD accuracy.

1. Introduction

The monitoring and management of forest resources have become increasingly important in the context of global climate change. Individual tree detection and segmentation play a critical role in forest management, because information at the individual tree level, such as locations and crown sizes, can be used to model growth, yield and fire behaviour, and to understand the ecology and dynamics of forests in ways that are directly applicable to forest management [1,2].

Thus far, the existing studies have primarily utilized satellite imagery, aerial imagery, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) imagery, and light detection and ranging (LiDAR) point cloud data to detect individual trees. Satellite imagery, although offering wide coverage, lacks the resolution necessary for individual tree detection [3,4]. LiDAR data can provide accurate three-dimensional information but the equipment to collect the data is usually expensive [5]. Furthermore, as LiDAR typically uses a single spectral band, there is a lack of spectral information and only geometric information is employed to detect and segment individual trees. When the branches of neighbouring trees intertwine, it is difficult to separate the trees solely based on geometric information. Compared to the other data sources, UAV imagery stands out as an important data source for individual tree detection and segmentation due to its ease of acquisition, abundant spectral information, and high spatial resolution [6,7,8].

By loading a UAV with different camera sensors, red-green-blue (RGB), multispectral, or hyperspectral images can be obtained. In particular, UAV-based visible light imaging has gained popularity due to its ability to capture extremely high-resolution RGB images and the low cost of equipment [9].

Existing research on individual tree crown detection (ITCD) using RGB imagery can be broadly classified into three categories: traditional image processing methods, machine learning-based methods, and deep learning-based methods. Traditional image processing methods include techniques like local maxima filtering [10], watershed segmentation [11,12] and region-growing [13]. These methods do not require the construction of a sample dataset for model training and are computationally efficient. However, they often rely on the assumption of high brightness at the top of the tree crown. Such an assumption may not hold in forests with significant crown overlap or a large proportion of broadleaf species [14]. Crown overlap often results in unclear crown boundaries, while broadleaf trees typically have irregular shapes and may have multiple treetops. Additionally, although UAV RGB imagery has high resolution, the complex texture within individual crowns, spectral heterogeneity, and noise make detection of individual tree crowns particularly challenging [15]. Machine learning-based methods, such as random forests and support vector machines, rely on hand-crafted features like colour, texture, and shape. Although these approaches can outperform traditional methods, they require extensive feature selection and are prone to overfitting without diverse training data [16,17]. Deep learning techniques have made significant progress in object detection from remote sensing imagery in recent years. Various deep learning networks, such as the YOLO series, Faster R-CNN and RetinaNet, have been developed for object detection. The detection of individual tree crowns can be considered as an object detection task. Some studies have used deep learning techniques to detect individual trees [18,19,20]. Deep learning-based methods are considered to be more effective and have better transferability than traditional machine learning-based approaches for detecting individual tree crowns due to their ability to learn hierarchical combinations of object-level image features and directly delineate objects of interest [21,22].

Existing approaches to individual tree detection primarily rely on single-seasonal images. In the forests with large canopy gaps or obvious treetops, such approaches based on brightness or spectral information can provide high accuracies of ITCD. However, in mixed species forests with a high proportion of broadleaf species, the detection and delineation of individual tree crowns remain a challenge. Neighbouring trees of different species may have similar spectral responses [23]. The varying crown size and the intertwining branches of broadleaf trees increase the difficulty of ITCD. One solution is to explore more features that can facilitate the differentiation between neighbouring trees of different species. Some studies have used multi-seasonal images to classify tree species, based on the observation that the seasonal variation in the spectral response of tree crowns differs between species [24,25]. For instance, ever-green trees may have a small seasonal variation in the spectral response, whereas the spectral response of deciduous trees may vary greatly due to defoliation and leaf regrowth. Although the use of multi-seasonal imagery helps improve the mapping of tree species [26], research on the application of multi-seasonal imagery to ITCD is rare. Berra [27] employed leaf-off imagery for digital terrain model (DTM) generation, while utilizing leaf-on imagery to derive digital surface model (DSM). A canopy height model was generated from the DTM and the DSM, which was then used for individual tree delineation. However, they did not employ the phenological signatures inherent in dual-seasonal datasets. Therefore, it is necessary to evaluate the extent to which the accuracy of ITCD can be improved by using dual- or multi-seasonal imagery. The selection of seasonal combinations for dual- or multi-seasonal imagery is another problem that requires systematic investigation.

To characterize the seasonal variations in the spectral responses of trees of different species, appropriate spectral, textural, and geometric features need to be extracted from dual- or multiple-seasonal images and be fused. However, the feature selection has always been a complex problem in related studies [28]. To address this issue, deep learning techniques can be used to simplify the complex problem and automate the data processing [29]. Among various object detection architectures, You Only Look Once (YOLO) series is well-known for its computational efficiency and superior performance in object detection tasks, in particular its ability to handle small and irregularly shaped objects [30]. Compared to its predecessors (e.g., YOLOv5 and YOLOv7), YOLOv8 introduces a series of vital enhancements and offers significant advantages in both efficiency and adaptability [31,32]. Previous studies have used this model for ITCD from UAV imagery [33].

In this study, we aim to explore the feasibility of improving the accuracy of ITCD by detecting individual trees from dual-seasonal UAV-captured RGB imagery. For this purpose, we modified the YOLOv8 model so as to automatically extract and fuse features from dual-seasonal RGB imagery for the detection of individual tree crowns. To assess the benefits of utilizing dual-seasonal RGB imagery, the modified model was trained and tested across three test sites featuring different subtropical forest types: urban broadleaved forest, planted coniferous forest, and mixed coniferous and broadleaved forest. UAV-captured RGB images collected across three seasons (winter, spring and autumn for test sites 1 and 3; winter, spring and summer for test site 2) were grouped into dual-seasonal combinations and employed for ITCD. The ITCD results were compared with those derived from single-seasonal imagery at each test site. Comparative analyses were further conducted on various seasonal combinations to quantify the impact of data acquisition timing on ITCD performance. Finally, we evaluated our modified YOLOv8 model against the original YOLOv8 model, which employed channel-wise stacked dual-seasonal inputs, to demonstrate our model’s capability for feature extraction and fusion.

2. Study Area and Datasets

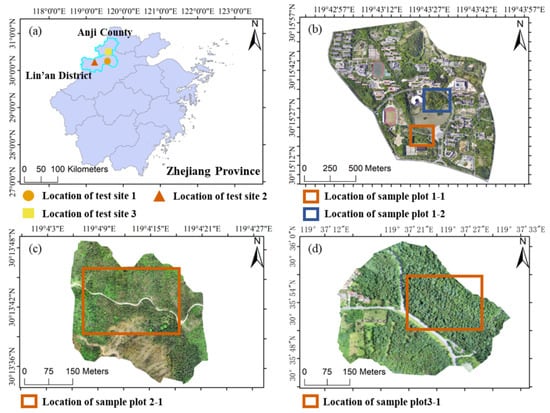

In this study, three test sites were selected to assess the application of dual-seasonal UAV-captured RGB imagery. Two are located in Lin’an District, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province, and the third is in Anji County, Huzhou City, Zhejiang Province (Figure 1). China’s administrative hierarchy primarily consists of the central government, provinces, prefecture-level cities, county-level administrative divisions (counties, county-level cities, districts, etc.), and township-level administrative divisions (towns, townships, subdistricts, etc.). RGB imagery was acquired using a DJI Phantom 4 RTK UAV, which is equipped with a 24 mm wide-angle camera with a 1-inch CMOS sensor. The operation area and flight route were set in the DJI GS RTK application, and the flight was automatically carried out following the set route. The flight parameters at each test site are detailed in Table 1. The details of all sample plots are summarized in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Overview of three test sites. (a) Location of three test sites. (b) Two sample plots (orange rectangles) on a UAV RGB image at test site 1. (c) One sample plot (orange rectangle) on a UAV RGB image at test site 2. (d) One sample plot (orange rectangle) on a UAV RGB image at test site 3.

Table 1.

Experimental data and UAV flight parameters.

Table 2.

Sample plot details.

Field datasets were acquired in each plot to facilitate subsequent tree crown labelling in images. A real-time kinematic (RTK) global navigation satellite system (GNSS) was used to determine stem locations. Other information such as tree species and diameter at breast height (DBH) was also documented. More details of the test sites and datasets are given as follows:

- (1)

- Test site 1

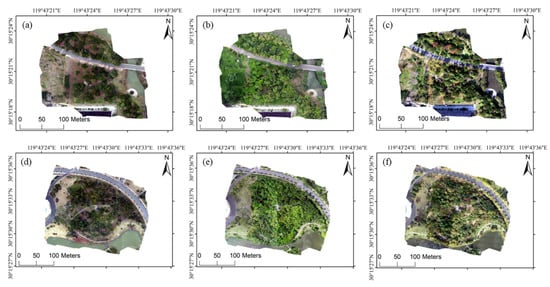

As shown in Figure 1, test site 1 is located on the campus of Zhejiang A&F University in Lin’an District, Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province (30.1533° N, 119.4327° E). This area has a typical subtropical monsoon climate, with an average annual temperature of around 16 °C and annual rainfall of around 1500 mm. Two sample plots (Figure 2) were selected to generate image sample dataset. The terrain within the sample plots is flat. Both sample plots have a high degree of canopy cover, with only a few shrubs. UAV RGB photos for test site 1 were collected in February (winter), May (spring), and November (autumn) 2023.

Figure 2.

UAV RGB images of the two sample plots at test site 1. (a,d) Winter images. (b,e) Spring images. (c,f) Autumn images.

- (2)

- Test site 2

Test site 2 is located in Changhua, Lin’an District, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province (30.1342° N, 119.4133° E). This area has a subtropical monsoon climate, with an average annual rainfall of around 1400 mm and an average annual temperature of 15.8 °C. One sample plot (Figure 3) was selected to generate image sample dataset. The main species within the sample plot is Chinese fir. Some broadleaved trees are unevenly distributed in this area, accounting for roughly 20% of the total population. Most of the area has a simple stand structure and relatively large tree spacing, with dense shrubs and small trees growing beneath the upper canopy in summer. UAV RGB photos for test site 2 were collected in January (winter), April (spring), and August (summer) 2023.

Figure 3.

UAV RGB images of the sample plot at test site 2. (a) Winter image. (b) Spring image. (c) Summer image.

- (3)

- Test site 3

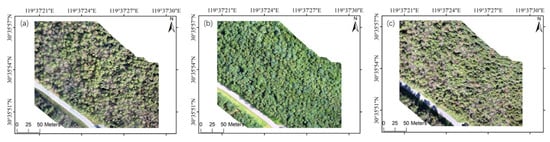

Test site 3 is located in Anji County, Huzhou City, Zhejiang Province (30.6382° N, 119.6820° E). This area has a subtropical monsoon climate characterized by a humid environment and dense vegetation, with annual rainfall of around 1600 mm and an average annual temperature of around 17 °C. One sample plot (Figure 4) was selected to generate image sample dataset. The forest type within test site 3 is a coniferous and broadleaved mixed forest. The tree density in this area is high, and the forest structure is complex, with multiple vertical layers. UAV RGB photos for test site 3 were collected in January (winter), April (spring), and October (autumn) of 2023.

Figure 4.

UAV RGB images of the sample plot at test site 3. (a) Winter image. (b) Spring image. (c) Autumn image.

3. Methodology

3.1. Pre-Processing of Datasets

After data collection, the UAV-captured RGB photos were preprocessed to generate a dataset for training and testing the deep learning model for ITCD. First, the UAV-captured RGB photos were processed in the DJI mapping software, DJI Terra 4.2.3, to generate orthomosaics. The images acquired in different seasons may have coordinate discrepancies, which would affect the ITCD result. Therefore, the image alignment tool in ArcMap 10.8 was then employed to align the orthorectified imagery acquired in different seasons to reduce the influence of coordinate discrepancy. All orthorectified imagery were resampled to the same spatial resolution of 0.035 m in ArcMap 10.8.

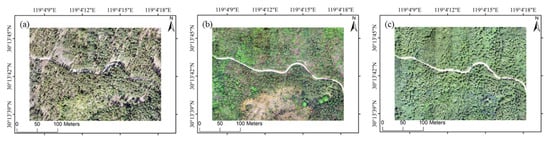

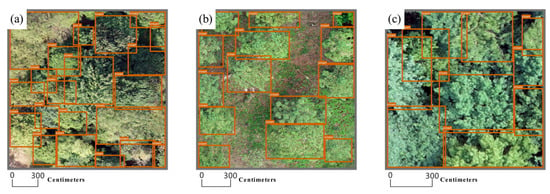

Subsequently, the preprocessed UAV images were cropped without overlapping, after which we conducted a quality inspection of all tiles and removed those that did not contain trees, resulting in a total of 1482 images with a size of 1024 × 1024 pixels for all three test sites. Each cropped image was then visually interpreted to accurately label each crown using rectangular boxes in LabelImg software [34], and we treat these manual labels as ground-truth bounding boxes, which is a common practice in ITCD studies [20]. Tree crowns were labelled mainly based on spectral disparities between neighbouring crowns and variations in the spectral response of tree crowns across seasons, as observed from the UAV images captured across different seasons. The quality of crown labelling was verified using the field dataset acquired by GNSS-RTK. Figure 5 presents the partial crown labelling results from three test sites.

Figure 5.

Example of crown labelling. (a) Partial result of crown labelling at test site 1. (b) Partial result of crown labelling at test site 2. (c) Partial result of crown labelling at test site 3.

A total of 4496 individual crowns were labelled. Following the strategy adopted in previous studies [35,36,37], the labelled cropped images were randomly divided into training, validation, and test datasets in a ratio of 7:2:1 within each test site. The training dataset was used for model training; the validation dataset was used for tuning model hyperparameters; the test dataset was used to evaluate the transferability of the trained model. The details of the sample datasets for each test site are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Information of cropped images and labelled tree crowns. Image count indicates the count of cropped images for each test site. Sample count indicates the count of labelled tree crowns for each test site.

The discrepancy between the sample counts and field-measured tree counts in Table 2 arises because some trees were completely occluded by the upper canopy in the orthophotos. Therefore, there were more field-measured trees than labelled samples used for the deep learning model.

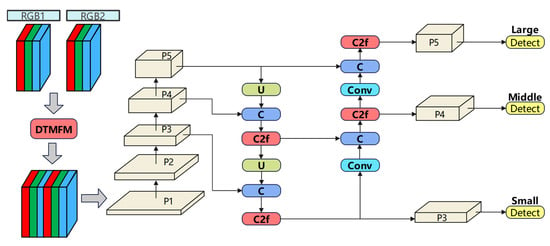

3.2. YOLOv8-DualFusion Model

YOLOv8 is an efficient computer vision model for object detection, classification, segmentation, etc. Since the original YOLOv8 model takes a single image as input, we proposed a modified YOLOv8 model, termed YOLOv8-DualFusion, to handle dual-seasonal images. The network architecture of YOLOv8-DualFusion is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of the YOLOv8-DualFusion network. DTMFM: dual-seasonal masked fusion module; Conv: convolutional block; U: up-sampling; C: concatenation; C2f: feature extraction module; P1–P5: multi-scale feature maps. This figure was adapted from reference [38]. Detailed description of the modules C2f and P1–P5 can be found in the original figure.

Similar to the original YOLOv8 model, the YOLOv8-DualFusion network architecture consists of three components: the backbone, the neck, and the head [32]. The original backbone of YOLOv8 is a convolutional neural network (CNN) which is used to extract multi-level image features. Our YOLOv8-DualFusion network adds a dual-seasonal masked fusion module (DTMFM) in the backbone to merge the dual-seasonal images at an early stage of the processing. Such an early fusion strategy allows the model to explore the correlations between the dual-seasonal images and thus capture the spectral variation in the crowns caused by seasonal changes [39,40].

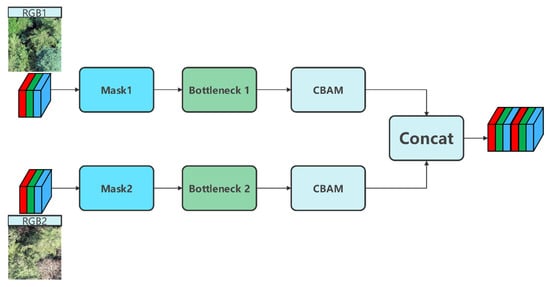

The architecture of DTMFM is shown in Figure 7. In this module, the dual-seasonal RGB images are taken as inputs. A mask generator is first applied to each input image to generate binary masks. These masks serve to highlight salient features pertinent to each input image while suppressing irrelevant information, thereby reducing background noise and enhancing the quality of the feature representations. During the feature extraction phase, two Bottleneck blocks, Bottleneck1 and Bottleneck2, are applied to each input image, respectively. These Bottleneck blocks decrease computational complexity by reducing the number of channels and facilitate the extraction of more refined and meaningful features through convolutional operations. Residual connections are integrated within the Bottleneck blocks to address the vanishing gradient problem commonly encountered in deep neural networks. Following feature extraction, the feature maps are processed by the convolutional block attention module (CBAM), which applies both channel and spatial attention mechanisms [41]. The channel attention mechanism enhances the network’s response to important channels while suppressing irrelevant ones. The spatial attention mechanism weights the spatial locations of the feature map, enabling the model to focus on spatial regions crucial for target detection. The DTMFM allows the model to focus on crown features in complex backgrounds, improving the robustness and accuracy of the model.

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram of DTMFM. CBAM: convolutional block attention module.

3.3. Experimental Design and Model Training

3.3.1. Experimental Design

At each test site, the UAV RGB images acquired over three seasons were combined into three sets of dual-seasonal data. Specifically, the seasonal combinations for test sites 1 and 3 were spring and winter, autumn and winter, spring and autumn, while for test site 2, the combinations were spring and winter, summer and winter, spring and summer. The YOLOv8-DualFusion model proposed in this study was trained and tested on each dual-seasonal image dataset at each test site in order to analyze the influence of the combination of seasons on the ITCD result in different forest types. In addition, the original YOLOv8 model was trained and tested on each single-seasonal image dataset at each test site to evaluate the difference between the ITCD results of dual- and single-seasonal image datasets. The original YOLOv8 model, which employed channel-wise stacked dual-seasonal inputs, was also applied to each dual-seasonal image dataset to assess the advantage of the YOLOv8-DualFusion model. Finally, to verify whether the observed improvements are detector-agnostic and arise from the use of dual-seasonal RGB imagery, we applied a Faster R-CNN model with the same dual-branch fusion module.

3.3.2. Training

The YOLOv8-DualFusion model was trained on a Windows 11 Professional operating system, with an Intel Core i9-12900K processor (Intel, Santa Clara, CA, USA), 32GB of memory, and an NVIDIA GeForce GTX 3070 Ti GPU (NVIDIA, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The Python version used was 3.8, and the deep learning framework was PyTorch 2.4.0 with CUDA 11.8.

Our model retained most of the default settings of the original YOLOv8 model. A variety of data augmentation techniques, such as random cropping, flipping, rotation, and mosaic, were used during training. The values of some key parameters used to train the model are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Key parameter values during model training.

3.4. Accuracy Evaluation Method

Following the accuracy evaluation method used in other studies [17,42,43], the accuracy evaluation metrics used in this study include Precision, Recall, F1 score, average precision (AP), and average intersection over union (IoU). Precision measures the proportion of positive predictions that are truly correct, while Recall evaluates the proportion of actual positive samples correctly identified. The F1 Score is used to balance Precision and Recall. The formulas used to calculate Precision, Recall, and F1 score are:

where TP is the number of true positives, i.e., samples that are actually positive and correctly predicted as positive by the model; FP represents the number of false positives, i.e., samples that are actually negative but incorrectly predicted as positive; FN is the number of false negatives, i.e., samples that are actually positive but incorrectly predicted as negative.

To determine TP, FP and FN, each bounding box prediction was compared with the ground truth bounding boxes that had been manually labelled in the images (see Section 3.1). For each ground truth, the bounding box prediction with the highest IoU and IoU value greater than 50% was taken as a match. TP is the number of matched bounding boxes, FP is the number of unmatched bounding box predictions, and FN is the number of unmatched ground truths.

The IoU is defined as the ratio of the area of overlap between the predicted box and the ground truth box to the area of their union:

The definition of AP is as follows:

where p(r) is a function that represents the change in Precision with Recall. The AP was calculated by first plotting the Precision-Recall curve and then calculating the area under the curve. The IoU threshold for calculating AP was set to 0.50, with the resulting AP denoted as AP@0.50. For detecting tree crowns with ambiguous boundaries, an AP evaluated with an IoU threshold of 0.5 is considered to be able to provide a more robust measure of detection performance [42,43,44,45].

The average IoU (referred to as AIoU) of all detected ground truths was calculated to quantify the overlap between predicted bounding boxes and ground-truth bounding boxes. Higher AIoU values indicate greater overlap and, therefore, a stronger correspondence between predictions and ground truths [46,47].

4. Results

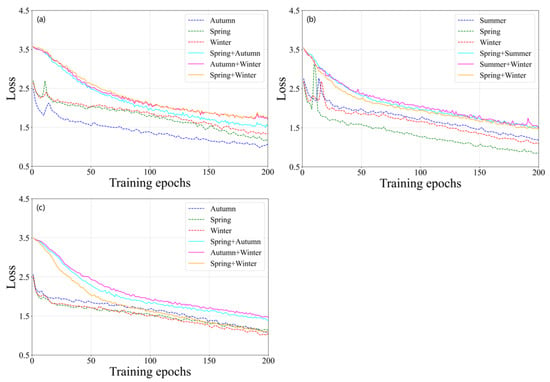

4.1. Model Training Result

Figure 8 illustrates the loss curves during the training process of the deep learning model from the three test sites. As shown in the figure, the loss values of the six models based on either dual- or single-seasonal data were initially high and then oscillated downward as the number of training epochs increased. The use of dual-seasonal imagery added complexity to the deep learning model, which had to learn more information than the model based on single-seasonal data. As a result, the models based on dual-seasonal imagery had slower convergence and higher loss values. Nevertheless, all models eventually stabilized and reached convergence.

Figure 8.

Model loss curves during training. (a) Test site1. (b) Test site2. (c) Test site3.

4.2. Evaluation of Model Accuracy on Test Datasets

Upon completion of model training, each trained model was applied to the test datasets from each test site in order to evaluate its transferability. The Precision, Recall, F1 score, AP, and AIoU values of the ITCD results were calculated. Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7 present the accuracies of the ITCD results for the three test sites using either single- or dual-seasonal test data.

Table 5.

Accuracy of ITCD from the test data on test site 1 (urban broadleaved forest).

Table 6.

Accuracy of ITCD from the test data on test site 2 (planted coniferous forest).

Table 7.

Accuracy of ITCD from the test data on test site 3 (mixed coniferous and broadleaved forest).

4.2.1. Accuracy Evaluation at Test Site 1

As indicated in Table 5, the detection accuracies (F1 and AP) were higher for all three dual-seasonal image datasets than for the single-seasonal data. The only exception was the combination of spring and winter data (hereafter referred to as spring + winter data), which exhibited a slightly lower AP value than the autumn data but a higher F1 score. Among the three dual-seasonal image combinations, the spring + autumn combination performed the best, achieving an F1 score of 75.4%, an AP value of 77.5%, and an AIoU value of 76.7%, all of which were higher than the detection accuracies of the single-seasonal data. Furthermore, despite the much lower accuracies obtained by using only spring or winter data, combining spring and winter data resulted in a significant improvement in ITCD accuracy. Compared to the spring data, the F1 score improved by 21.0% and the AP by 27.9%. In comparison to the winter data, the F1 score improved by 11.2% and the AP by 18.9%. These results demonstrate that incorporating features describing the spectral changes in different tree species can significantly improve the accuracy of ITCD. A subset of the ITCD result with the highest accuracy is shown in Figure 9.

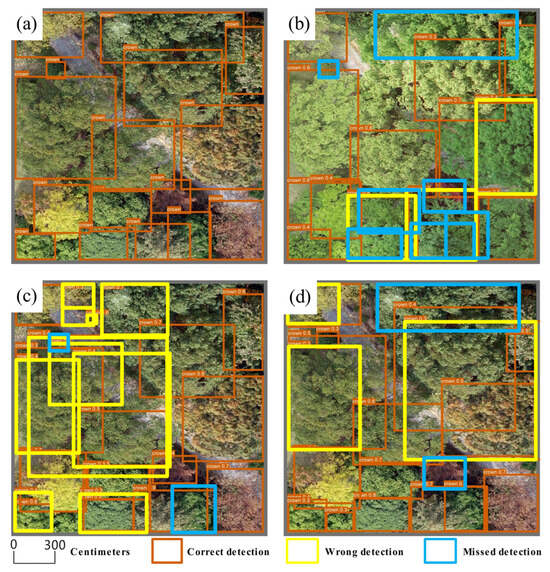

Figure 9.

Partial ITCD result at test site 1. (a) Labelled data. (b) Result of spring data. (c) Result of autumn data. (d) Result of spring + autumn data.

As shown in Figure 9, the ITCD result based on dual-seasonal data had fewer wrong and missed detections than the results based on spring or autumn data. In the spring images, the similar spectral values of neighbouring tree crowns and the crown overlap made it difficult to distinguish between crowns. In contrast, the leaves of almost all tree species changed colour to varying degrees in autumn, making it easier to distinguish between trees of different species. Therefore, the ITCD using the spring data had a much lower accuracy than the one using the autumn data. Combining the spring and autumn data resulted in additional features that can describe the spectral changes in different tree species from spring to autumn, facilitating the improvement of ITCD accuracy.

4.2.2. Accuracy Evaluation at Test Site 2

On test site 2 dominated by a planted Chinese fir forest, relatively high ITCD accuracies were derived by using single-seasonal image data. The ITCD accuracy was improved by using the dual-seasonal image combinations compared to the single-seasonal data. The spring + winter image combination performed best with an F1 score of 74.9%, an AP value of 82.1%, and an AIoU value of 79.3%. Compared to the spring data, the F1 score has improved by 3.4%, the AP by 8.5%, and the AIoU by 5.4%. Compared to the winter data, the F1 score increased by 3.1%, the AP by 13.9%, and the AIoU by 7.4%. A subset of the ITCD result with the highest accuracy is shown in Figure 10.

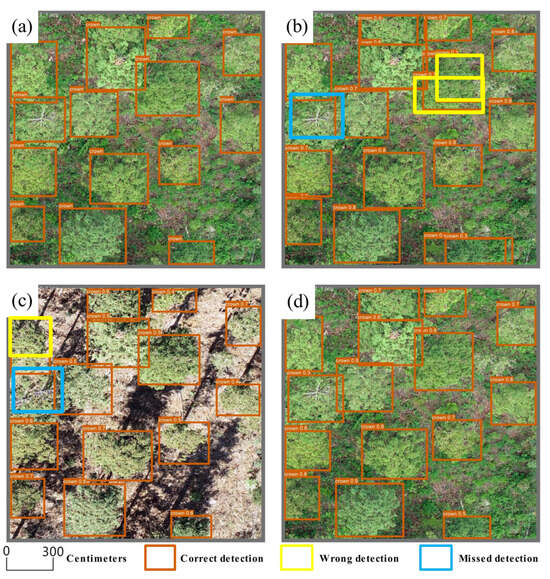

Figure 10.

Partial ITCD result at test site 2. (a) Labelled data. (b) Result of spring data. (c) Result of winter data. (d) Result of spring + winter data.

In the spring image (Figure 10b), the spectral response of the grass and shrubs on the ground is similar to that of tree crowns. The spectral similarity tended to cause the model to misclassify background (grass and shrubs) as canopy, or to misclassify canopy as background. In summer, the grass and shrubs became more abundant, making it more difficult to detect individual tree crowns. Consequently, the ITCD accuracy of the summer data was the lowest, as shown in Table 6. The summer + winter and spring + summer image combinations derived only slight improvement in detection accuracy, indicating the influence of the grass and shrubs between tree crowns on the ITCD result. The techniques of feature extraction and background suppression should be further investigated to address this issue. In winter, the influence of grass and shrubs was minimized. However, the detection accuracy was affected by the shadows in the winter images (see Figure 10c), which were usually caused by the timing of image acquisition. Nevertheless, the experimental results from this test site further confirm that the use of dual-seasonal data can improve the ITCD accuracy.

4.2.3. Accuracy Evaluation at Test Site 3

Of the three test sites, test site 3 had the most complex forest structure, resulting in lower ITCD accuracies for the single-seasonal data, with F1 values ranging from 56.3% to 60.7% and AP values ranging from 57.2% to 61.5%. The detection accuracies for all three dual-seasonal image combinations were much higher than those of the single-seasonal data. Among these, the spring + winter image combination performed the best, achieving a significant improvement in both F1 score and AP value compared to the single-seasonal images. A subset of the ITCD result with the highest accuracy is shown in Figure 11.

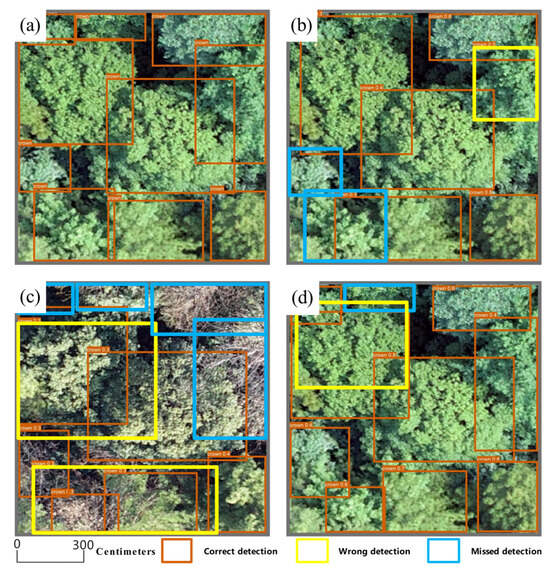

Figure 11.

Partial ITCD result at test site 3. (a) Labelled data. (b) Result of spring data. (c) Result of winter data. (d) Result of spring + winter data.

As shown in the figure, the spectral and textural features in the spring and winter images are highly complementary. By combining data from both seasons, neighbouring crowns of different tree species can be better distinguished, thereby improving the detection accuracy. This result indicates that even in a forest with a complex structure, a high detection accuracy can be derived by using dual-seasonal RGB imagery, which is only slightly lower than the accuracies at test sites 1 and 2. Moreover, similar to test site 1, the tree crowns detected at test site 3 have a large variation in size, indicating the ability of the modified YOLOv8 model to detect multi-scale objects.

4.3. Ablation Analysis

The DTMFM used in our YOLOv8-DualFusion model comprises two feature-extraction components (CBAM and Bottleneck blocks) for each branch. To evaluate the contributions of the blocks, the YOLOv8-DualFusion model was revised by removing the CBAM block and retaining the Bottleneck block in the DTMFM. The YOLOv8-DualFusion model without the CBAM block is referred to as YOLOv8-BN. The YOLOv8-BN model was trained and tested using the dual-seasonal imagery from each test site. Table 8 shows the ITCD accuracy derived from the test datasets by the YOLOv8-BN model and YOLOv8-DualFusion.

Table 8.

Accuracy of ITCD using the YOLOv8-BN model on test datasets for each test site.

For each dual-seasonal image dataset at each test site, YOLOv8-DualFusion achieved higher F1, AP and AIoU values than YOLOv8-BN. The only exception was the autumn + winter combination at test site 3, where the difference in F1 score between the two models was slight (0.6%). The ablation test indicates that integrating CBAM into DTMFM yields consistently better detection and localization across sites and seasonal combinations. As a result, the findings confirm that CBAM materially contributes to performance gains under dual-seasonal fusion.

4.4. Comparison with Original YOLOv8 Model

To determine whether the gains of dual-seasonal RGB imagery arise merely from an increase in channels or from our YOLOv8-DualFusion’s capability to acquire complementary seasonal information, we applied the original YOLOv8 model, which employed channel-wise stacked dual-seasonal inputs, to the datasets at each test site.

As shown in Table 9, the original YOLOv8 model achieved lower F1 scores and AP values than the YOLOv8-DualFusion model. YOLOv8-DualFusion achieved higher Precision and Recall values than the original YOLOv8 model in almost all cases. At test sites 1 and 2, the F1 score or AP value derived from the original YOLOv8 model using dual-seasonal RGB imagery as input is even lower than that derived from single-seasonal imagery. These results indicate that simply concatenating RGB images from different seasons into a multi-band input increases dimensionality but fails to extract salient features for differentiating between neighbouring trees. The likely reason is that, under layer stacking, the network is forced to learn a single feature set that must accommodate markedly different crown appearances across seasons, leading to compromised representations and, in turn, generally inferior detection accuracy. In contrast, the dual-branch architecture of YOLOv8-DualFusion can learn season-specific representations and fuse them at the feature level. This preserves complementary information, such as leaf-off texture and leaf-on morphology, and yields higher, more consistent ITCD accuracy across sites and seasonal combinations. However, the original YOLOv8 and YOLOv8-DualFusion models produced consistent results and achieved similar accuracies at test site 3. This suggests that dual-seasonal RGB imagery offers a significant advantage for this type of forest, exerting an influence that surpasses that of the models employed.

Table 9.

Evaluation against original YOLOv8 model.

4.5. Evaluation Against Faster R-CNN

In order to evaluate the applicability of dual-seasonal imagery to ITCD across different detectors, we compared YOLOv8-DualFusion with Faster R-CNN, a popular two-stage object detection model. The dual-branch fusion module (DTMFM) used by YOLOv8-DualFusion was added to the original Faster R-CNN. The modified version of Faster R-CNN (hereafter referred to as Faster-DualFusion) was applied to the same dual-seasonal datasets as YOLOv8-DualFusion. As a comparison, the original Faster R-CNN was applied to the single-seasonal datasets. The reported Precision, Recall, F1 score, AP, and AIoU for each test site are summarized in Table 10.

Table 10.

Accuracy of ITCD using the Faster R-CNN or Faster-DualFusion model on test datasets for each test site.

As shown in Table 10, the test accuracy of Faster-DualFusion using dual-seasonal imagery was higher than that using single-seasonal imagery at all three test sites. The optimal seasonal combinations that achieved the highest F1, AP and AIoU values for each test site were the same for both the Faster-DualFusion and YOLOv8-DualFusion models. Further comparisons between YOLOv8-DualFusion and other models can be found in Supplementary Materials document.

5. Discussion

5.1. Advantages of Dual-Seasonal Image Combination

In this study, the ITCD results derived from single-seasonal image datasets indicated that the season of UAV data collection had a significant effect on the ITCD result. There were considerable differences in the ITCD accuracy (F1, AP and AIoU) between data from different seasons. In the urban broadleaved forest (test site 1), the autumn data yielded the best results (F1 = 71.0%, AP = 76.1%, AIoU = 72.9%), whereas the spring data had the lowest accuracy (F1 = 51.5%, AP = 46.7%, AIoU = 66.3%). In contrast, the optimal data for the other two test sites were from the spring season. The crowns of different tree species have similar spectral reflectance in the spring and summer data, making it challenging for the model to distinguish between neighbouring tree crowns. This is especially problematic in dense forests. Furthermore, in summer, grass and shrubs grow taller, and their spectral reflectance is similar to that of tree crowns, making it difficult to distinguish between background (grass and shrubs) and canopy and increasing the difficulty of ITCD. In both autumn and winter data, the spectral reflectance of the crowns of different tree species is significantly different. The winter data also show considerable differences in textural characteristics as a result of defoliation. However, the spectral reflectance of deciduous trees in winter is similar to that of the ground, leading to misclassification between canopy and ground. In addition, the ITCD result is also influenced by data quality. Environmental conditions, the timing of UAV data collection, and the equipment used for data collection all affect data quality. For instance, the data collected in the morning or afternoon tends to be heavily shaded, causing the canopy to be misclassified as background and undetected. Excessive image noise caused by instrument imperfections or environmental factors can also affect the ITCD result. In summary, it is difficult to find an optimal season for data collection for all forests due to differences in forest conditions and data quality.

With the use of dual-seasonal image data, the accuracy of ITCD improved to varying degrees at the three test sites compared to the use of single-seasonal data. Even if low ITCD accuracies were derived by using single-seasonal data, combining the data from two seasons can lead to significant improvements. For example, at test site 1, the F1 score was 51.5% for spring data, and was 61.3% for winter data. When the spring and winter data were combined, the F1 score rose to 72.5%. These results indicate that the features extracted from dual-seasonal images can effectively capture species-specific spectral reflectance variations in tree crowns across seasons, enabling enhanced crown delineation in mixed stands. In addition, the combination of dual-seasonal images can help mitigate the effects of background (e.g., grass and shrubs) and data quality issues (e.g., shadows) on the ITCD result. However, the extent of these gains depends on the approach to feature extraction and fusion. Simply concatenating dual-seasonal imagery into a six-channel input does not necessarily improve the accuracy of ITCD. This was evaluated in Section 4.4 through a comparison between the original YOLOv8 and our modified version (YOLOv8-DualFusion). Some of the accuracy values derived by the original YOLOv8 using dual-seasonal imagery were even slightly lower than those derived using single-seasonal imagery.

The improvement in accuracy gained by using dual-seasonal imagery was also demonstrated by applying the original Faster R-CNN and the modified version (Faster-DualFusion) to the single- and dual-seasonal image datasets, respectively (see Section 4.5). The consistent results between Faster R-CNN and YOLOv8 suggest that the improvement in accuracy achieved by using dual-seasonal RGB imagery is independent of the detector and primarily arises from the fusion of complementary seasonal features. However, the ITCD accuracy derived by the Faster-DualFusion model was lower than that derived by the YOLOv8-DualFusion model at all three test sites (see Figures S1–S3 in Supplementary Materials). This suggests that the accuracy of ITCD is influenced to some extent by model selection.

The benefits of using dual-seasonal image data have also been proven in other studies that fulfil tasks such as tree species classification and disease tree detection. For example, Veras et al. [48] used UAV-captured RGB imagery across four phenological stages (February, May, August, November) to train a tree species classification network, which demonstrated a 21.1% enhancement in classification accuracy over the models based on single-seasonal data. However, they adopted a pixel-based rather than tree-level classification method. By integrating dual-seasonal satellite imagery (WorldView-3 for summer and Google Earth for winter), Guo et al. [49] achieved a 3% improvement in tree species classification accuracy (from 75.1% to 78.1%). The study employed a marker-controlled watershed segmentation algorithm to delineate individual tree crowns, subsequently generating training datasets for the deep learning model. More recently, Li et al. [36] fused UAV imagery acquired on two consecutive dates (18 and 19 October) within a YOLOv8—based framework for pine wood nematode disease tree detection, raising mAP50 from 71.9% to 78.5%. Although dual- or multi-seasonal remote sensing imagery has proven effective for diverse applications, the benefits of using dual- or multi-seasonal imagery for ITCD within a deep learning framework have not been systematically evaluated. Our study evaluated the advantages of using dual-seasonal imagery for ITCD in various types of forest and examined the impact of different seasonal combinations.

Although the optimal seasonal combination differed between test sites, the differences in F1 score and AP value between the three seasonal combinations were smaller than the differences between single-seasonal datasets. On test sites 1, 2 and 3, the largest difference in F1 score between the three single-seasonal datasets was 19.5%, 5.4% and 4.4%, respectively, while the largest difference between the three seasonal combinations was 2.9%, 3.4% and 5.4%, respectively. As for the AP value, the largest difference between the three single-seasonal datasets was 29.4%, 8.1% and 4.3%, respectively, while the largest difference between the three seasonal combinations was 2.9%, 6.1% and 2.7%, respectively. The comparative analysis shows that relatively consistent ITCD accuracy can be obtained by integrating dual-seasonal images from any two seasons. Therefore, data from any two seasons can be combined in practical applications, depending on data availability. However, this conclusion still needs to be further validated using more datasets over four seasons in different types of forest.

Notably, the enhanced ITCD performance enabled by dual-seasonal imagery facilitates more effective forest monitoring and management. Accurate detection of individual trees makes it possible to derive information such as crown widths and tree density within a specific area. It also allows tasks such as tree species classification and disease tree detection to be conducted at an individual tree level. Seasonal variations in the spectral responses of individual tree crowns can facilitate these tasks. In further study, we will investigate the phenological signatures of broad-leaved species inherited in dual- or multi-seasonal imagery and adapt our dual-seasonal framework for tree species classification based on individual tree detection.

5.2. Limitations

As indicated by the experimental results, the most significant improvement in accuracy was achieved at test site 3, which is covered by a dense mixed coniferous and broadleaved forest. At test site 3, the F1 score exhibited a range of 56.3% to 60.7% when utilizing different single-seasonal datasets. This range increased to 69.1%–74.5% when dual-seasonal datasets were used instead. Correspondingly, the AP value range increased from 57.2%–61.5% to 70.1%–72.8%. In contrast, less improvement in accuracy was observed at both test sites 1 and 2. In particular, at test site 2, which is dominated by a planted coniferous forest with relatively large tree spacing, the ITCD results from the single-seasonal image datasets already had high accuracies (F1 score and AP value above 70%). Therefore, ITCD based on dual-seasonal RGB imagery is more advantageous in dense mixed species forests than in forests with a simple structure.

It is worth noting that this study does not rely on a very large dataset. This is due to limitations in data collection. Multiple-seasonal RGB image datasets covering different forest types were required, as well as field-measured data to verify the tree crown labelling. Such datasets were difficult to collect over a large area. However, Bumbaca et al. [50] showed that the YOLO models can reach benchmark performance with approximately 110–130 annotated training images. Everingham et al. [45] also utilized relatively small training datasets for object detection benchmarks. In their research, the number of annotated objects per class was in the hundreds. Zhang et al. [51] used only 2610 bounding boxes across three tree species for species classification. Sun et al. [52] trained a deep learning model using 2269 manually labelled samples of individual trees (340 of which were used for testing) and achieved strong performance in the segmentation of individual tree crowns and extraction of crown width. Additionally, previous studies have shown that data augmentation can increase the size of training datasets and improve their quality, thereby enhancing model performance and generalization [53]. In the context of remote sensing, Hao et al. [54] compared a range of augmentation techniques and highlighted their effectiveness for small-sample training. In our study, we employed a range of augmentation techniques, including translation, scaling, rotation, and noise perturbation, to expand the training dataset. Nevertheless, more datasets covering different forest types should be acquired to further evaluate the advantages of dual-seasonal RGB imagery for ITCD and tree species classification, and to improve the deep learning model.

The deep learning model employed in this study, i.e., YOLOv8-DualFusion, used rectangular boxes to approximate the extents of tree crowns, providing location information for individual tree crowns. However, the precise boundaries of the tree crowns were not extracted. On one hand, the focus of this study is to evaluate the advantages of using dual-seasonal images, rather than delineating precise crown boundaries. On the other hand, in dense forests with significant crown overlap, especially in broad-leaved forests, the boundaries between adjacent crowns are difficult to delineate. In this study, both test sites 1 and 3 are covered by dense forests with a large proportion of broad-leaved trees. In such forests, even manually delineating crown boundaries is challenging. Future research can combine instance segmentation networks with boundary optimization algorithms to achieve accurate crown boundary delineation. It should also be noted that the difficulty of delineating crown boundaries in dense forests poses a great challenge to crown labelling. Although we performed crown labelling based on both seasonal variations in spectral responses of crowns and field measurements, inaccurate crown boundaries may still degrade model accuracy.

6. Conclusions

This study assesses the application of dual-seasonal UAV-captured RGB imagery for individual tree crown detection (ITCD) and examines the potential accuracy improvements across various forest types. A modified YOLOv8 model (YOLOv8-DualFusion) was trained and tested at three sites with different forest types. It was compared with the original YOLOv8 model, which was applied to single-seasonal datasets, and with the original model using channel-wise stacked dual-seasonal imagery as inputs. For comparison, the original and modified Faster R-CNN models were also applied to the single- and dual-seasonal datasets, respectively. An ablation analysis was conducted to evaluate the contribution of the convolutional block attention module. The experimental results showed that using dual-seasonal imagery improved detection accuracy, particularly in dense mixed forests with complex structures. The use of single-seasonal datasets resulted in performance fluctuations influenced by acquisition season, data quality issues (e.g., shadow interference), and spectral confusion between canopy and background objects (e.g., grass/shrubs). In contrast, when using dual-seasonal image data, the detection accuracies obtained for different combinations of seasons showed relatively small variations. Model comparison revealed that YOLOv8-DualFusion achieved higher ITCD accuracy than other models at each test site. These results demonstrate that the improvement in ITCD accuracy was due not only to the complementary seasonal information, but also to the model structure and the way features extracted from dual-seasonal imagery were fused.

The findings of this study provide guidance on selecting between single-seasonal and dual-seasonal image datasets across various forest types and also inform the optimal data collection season or combination of seasons. However, we used a rectangular box to approximate the crown extent rather than trying to outline the crown boundary. Models that can perform instance segmentation should be considered, or post-processing can be implemented to extract accurate crown boundaries.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/f16101614/s1: Figure S1. Accuracy comparison of four models on Test Site 1: (a) F1 score; (b) AP; (c) AIoU. Figure S2. Accuracy comparison of four models on Test Site 2: (a) F1 score; (b) AP; (c) AIoU. Figure S3. Accuracy comparison of four models on Test Site 3: (a) F1 score; (b) AP; (c) AIoU.

Author Contributions

S.Y.: Methodology, Writing—original draft. K.C.: Methodology, Writing—review and editing. K.X.: Writing—review and editing, Funding acquisition. Y.W.: Resources, Writing—review and editing. H.L.: Methodology, Investigation. S.D.: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing—review and editing, Funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under grant numbers 32101517, 32271869, and the National Key Research and Development Program of China under grant number 2022YFD2200504.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used in this study are available from a third-party repository upon reasonable request and under a research-use licence. The analysis code is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request for academic, non-commercial purposes.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editor and anonymous reviewers whose comments have contributed to improving the quality of this article. They also gratefully acknowledge the support of various foundations.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Jeronimo, S.M.A.; Kane, V.R.; Churchill, D.J.; McGaughey, R.J.; Franklin, J.F. Applying LiDAR individual tree detection to management of structurally diverse forest landscapes. J. For. 2018, 116, 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.Y.; Zeng, W.S.; Tang, S.Z. Individual tree biomass models to estimate forest biomass for large spatial regions developed using four pine species in China. For. Sci. 2017, 63, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ontl, T.A.; Janowiak, M.K.; Swanston, C.W.; Daley, J.; Handler, S.D.; Cornett, M.W.; Hagenbuch, S.; Handrick, C.; McCarthy, L.; Patch, N. Forest management for carbon sequestration and climate adaptation. J. For. 2020, 118, 86–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdarici-Ok, A. Automatic detection and delineation of citrus trees from VHR satellite imagery. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2015, 36, 4275–4296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Hyyppä, J.; Kaartinen, H.; Lehtomäki, M.; Pyörälä, J.; Pfeifer, N.; Holopainen, M.; Brolly, G.; Francesco, P.; Hackenberg, J.; et al. International benchmarking of terrestrial laser scanning approaches for forest inventories. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2018, 144, 137–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Y.; Wang, Q.; Iio, A. Tree crown detection and delineation in a temperate deciduous forest from UAV RGB imagery using deep learning approaches: Effects of spatial resolution and species characteristics. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Grybas, H.; Congalton, R.G. Individual tree crown delineation from UAS imagery based on region growing and growth space considerations. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troles, J.; Schmid, U.; Fan, W.; Tian, J. BAMFORESTS: Bamberg benchmark forest dataset of individual tree crowns in very-high-resolution UAV images. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez, Y.; Kentsch, S.; Fukuda, M.; Caceres, M.L.L.; Moritake, K.; Cabezas, M. Deep learning in forestry using UAV-acquired RGB data: A practical review. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhou, Z.; Tang, Y.; Qu, Y. Individual tree crown detection from high spatial resolution imagery using a revised local maximum filtering. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 258, 112397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Tian, J.; Troles, J.; Döllerer, M.; Kindu, M.; Knoke, T. Comparing deep learning and MCWST approaches for individual tree crown segmentation. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2024, 10, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Li, X.; Chen, C. Individual tree crown detection and delineation from very-high-resolution UAV images based on bias field and marker-controlled watershed segmentation algorithms. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2018, 11, 2253–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, M.; Olofsson, K. Comparison of three individual tree crown detection methods. Mach. Vis. Appl. 2005, 16, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Jing, L.; Hu, B.; Li, H.; Tang, Y. A new individual tree crown delineation method for high resolution multispectral imagery. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harikumar, A.; D’Odorico, P.; Ensminger, I. Combining spectral, spatial-contextual, and structural information in multispectral UAV data for spruce crown delineation. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, W.; Ho, H.W.; Zhou, Y.; Suandi, S.A.; Ismail, F. A comprehensive review on tree detection methods using point cloud and aerial imagery from unmanned aerial vehicles. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 227, 109476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivanandam, P.; Lucieer, A. Tree detection and species classification in a mixed species forest using unoccupied aircraft system (UAS) RGB and multispectral imagery. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, J.G.C.; Hickman, S.H.M.; Jackson, T.D.; Koay, X.J.; Hirst, J.; Jay, W.; Archer, M.; Aubry-Kientz, M.; Vincent, G.; Coomes, D.A. Accurate delineation of individual tree crowns in tropical forests from aerial RGB imagery using Mask R-CNN. Remote Sens. Ecol. Conserv. 2023, 9, 641–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freudenberg, M.; Magdon, P.; Nolke, N. Individual tree crown delineation in high-resolution remote sensing images based on U-Net. Neural Comput. Appl. 2022, 34, 22197–22207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, B.G.; Marconi, S.; Aubry-Kientz, M.; Vincent, G.; Senyondo, H.; White, E.P. DeepForest: A Python package for RGB deep learning tree crown delineation. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2020, 11, 1743–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boston, T.; Van Dijk, A.; Larraondo, P.R.; Thackway, R. Comparing CNNs and random forests for Landsat image segmentation trained on a large proxy land cover dataset. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäyrä, J.; Keski-Saari, S.; Kivinen, S.; Tanhuanpää, T.; Hurskainen, P.; Kullberg, P.; Poikolainen, L.; Viinikka, A.; Tuominen, S.; Kumpula, T.; et al. Tree species classification from airborne hyperspectral and LiDAR data using 3D convolutional neural networks. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 256, 112322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onishi, M.; Ise, T. Explainable identification and mapping of trees using UAV RGB image and deep learning. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, M.P.; Wagner, F.H.; Aragão, L.E.O.C.; Shimabukuro, Y.E.; de Moraes, M.V.A.; Honkavaara, E. Tree species classification in tropical forests using visible to shortwave infrared WorldView-3 images and texture analysis. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2019, 149, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyoshi, G.T.; Imai, N.N.; Tommaselli, A.M.G.; de Moraes, M.V.A.; Honkavaara, E. Evaluation of hyperspectral multitemporal information to improve tree species identification in the highly diverse Atlantic Forest. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyns, R.; Efthymiadis, K.; Libin, P.; Canters, F. Fusion of multi-temporal PlanetScope data and very high-resolution aerial imagery for urban tree species mapping. Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 99, 128410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berra, E.F. Individual tree crown detection and delineation across a woodland using leaf-on and leaf-off imagery from a UAV consumer-grade camera. J. Appl. Remote Sens. 2020, 14, 034501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassnacht, F.E.; Latifi, H.; Stereńczak, K.; Modzelewska, A.; Lefsky, M.; Waser, L.T.; Straub, C.; Ghosh, A. Comparison of feature reduction algorithms for classifying tree species with hyperspectral data on three Central European test sites. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2014, 7, 2547–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.P.; Yadav, M. 3D-MFDNN: Three-dimensional multi-feature descriptors combined deep neural network for vegetation segmentation from airborne laser scanning data. Measurement 2023, 221, 113465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, R.; Sambath, M. YOLOv8: A novel object detection algorithm with enhanced performance and robustness. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Advances in Data Engineering and Intelligent Computing Systems (ADICS), Chennai, India, 18–19 April 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, L.; Casas, E.; Bendek, E.; Romero, C.; Rivas-Echeverría, F. Hyperparameter optimization of YOLOv8 for smoke and wildfire detection: Implications for agricultural and environmental safety. Artif. Intell. Agric. 2024, 12, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, E.; Ramos, L.; Bendek, E.; Rivas-Echeverría, F. Assessing the effectiveness of YOLO architectures for smoke and wildfire detection. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 96554–96583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prousalidis, K.; Bourou, S.; Velivassaki, T.-H.; Voulkidis, A.; Zachariadi, A.; Zachariadis, V. Olive tree segmentation from UAV imagery. Drones 2024, 8, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-Y. LabelImg. GitHub Repository. Available online: https://github.com/tzutalin/labelImg (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Zhou, Z.; Cui, Z.; Tang, K.; Tian, Y.; Pi, Y.; Cao, Z. Gaussian meta-feature balanced aggregation for few-shot synthetic aperture radar target detection. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2024, 208, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, K.; Ji, Y.; Xu, Z.; Gu, J.; Jing, W. A spatio-temporal multi-scale fusion algorithm for pine wood nematode disease tree detection. J. For. Res. 2024, 35, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Lan, S.; Fan, X.; Tjahjadi, T.; Jin, S.; Cao, L. A dual-branch weakly supervised learning based network for accurate mapping of woody vegetation from remote sensing images. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2023, 124, 103499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ultralytics. Brief Summary of YOLOv8 Model Structure. Issue #189, Ultralytics/Ultralytics (GitHub). 2023. Available online: https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics/issues/189 (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Gadzicki, K.; Khamsehashari, R.; Zetzsche, C. Early vs late fusion in multimodal convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 23rd International Conference on Information Fusion (FUSION), Rustenburg, South Africa, 6–9 July 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roitberg, A.; Pollert, T.; Haurilet, M.; Martin, M.; Stiefelhagen, R. Analysis of deep fusion strategies for multi-modal gesture recognition. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), Long Beach, CA, USA, 16–17 June 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kweon, I.S. CBAM: Convolutional block attention module. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beloiu, M.; Nojar, M.; Bularca, M.C.; Săvulescu, I.; Savin, A.; Popa, I. Individual tree-crown detection and species identification in heterogeneous forests using aerial RGB imagery and deep learning. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M.; Feirer, S.; Hogan, S.; Lyons, A.; Lin, F.; Jacygrad, E. Mapping orchard trees from UAV imagery through one growing season: A comparison between OBIA-based and three CNN-based object detection methods. Drones 2025, 9, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäyrä, J.; Tanhuanpää, T.; Kuzmin, A.; Heinaro, E.; Kumpula, T.; Vihervaara, P. Using UAV images and deep learning to enhance the mapping of deadwood in boreal forests. Remote Sens. Environ. 2025, 329, 114906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everingham, M.; Van Gool, L.; Williams, C.K.I.; Winn, J.; Zisserman, A. The PASCAL visual object classes (VOC) challenge. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2010, 88, 303–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Yang, H.; Chen, T. Building extraction from very-high-resolution remote sensing images using semi-supervised semantic edge detection. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Tian, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, R. Water body extraction from high spatial resolution remote sensing images based on enhanced U-Net and multi-scale information fusion. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veras, H.F.P.; Ferreira, M.P.; da Cunha Neto, E.M.; Figueiredo, E.O.; Dalla Corte, A.P.; Sanquetta, C.R. Fusing multi-season UAS images with convolutional neural networks to map tree species in Amazonian forests. Ecol. Inform. 2022, 71, 101815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Li, H.; Jing, L.; Wang, P. Individual tree species classification based on convolutional neural networks and multitemporal high-resolution remote sensing images. Sensors 2022, 22, 3157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bumbaca, S.; Borgogno-Mondino, E. On the minimum dataset requirements for fine-tuning an object detector for arable crop plant counting: A case study on maize seedlings. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lei, F.; Fan, X. Parameter-efficient fine-tuning for individual tree crown detection and species classification using UAV-acquired imagery. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Huang, C.; Zhang, H.; Chen, B.; An, F.; Wang, L.; Yun, T. Individual tree crown segmentation and crown width extraction from a heightmap derived from aerial laser scanning data using a deep learning framework. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 914974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorten, C.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M. A survey on image data augmentation for deep learning. J. Big Data 2019, 6, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Liu, L.; Yang, R.; Yin, L.; Zhang, L.; Li, X. A review of data augmentation methods of remote sensing image target recognition. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).