1. Introduction

Forests constitute a vital component of the Earth’s ecosystems, playing a pivotal role in preserving biodiversity, regulating climate, and conserving soil and water. Nevertheless, wildfires pose a persistent and severe threat to these ecosystems. Conventional monitoring techniques—including ground patrols, observation from lookout towers, and satellite remote sensing—all exhibit significant limitations. These include significant constraints imposed by manpower, material resources, and geographical conditions, coupled with low detection accuracy and slow response times. With advances in science and technology, drones have increasingly been deployed for wildfire detection. Since the US Forest Service’s (USFS) inaugural deployment in 1961, drone forest fire monitoring technology has undergone substantial advancement. Over several decades, a series of pivotal projects—such as Firebird 2001, the Wildfire Research and Applications Partnership (WRAP) project, NASA’s “Altair” and the “Ikhana” (Predator-B) missions, and the First Response Experiment (FiRE) project—have demonstrated UAV capabilities in real-time imaging, data transmission, and operational deployment, validating their effectiveness in real-time disaster data collection [

1]. However, wildfire imagery captured from a drone perspective presents challenges including highly variable target scales, a high proportion of small targets, and severe background interference.

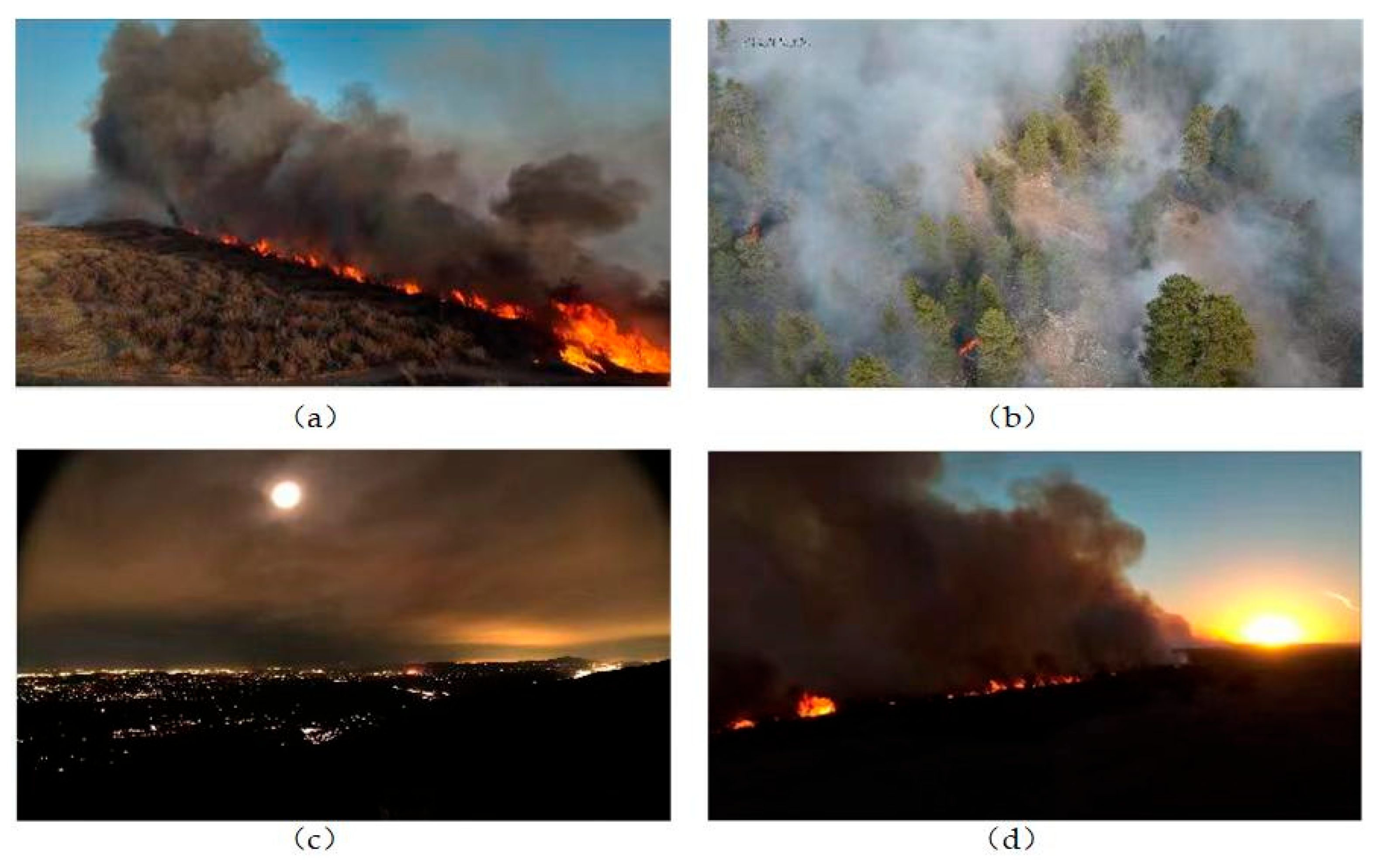

Figure 1 shows an example of a wildfire captured by a drone. As shown in

Figure 1a, the image contains multiple flame targets with significant scale differences;

Figure 1b indicates that flame targets account for a tiny proportion of the image during the early stages of a fire;

Figure 1c,d show that many background elements in the images share similar features with the fire targets, such as sunset and nighttime lights resembling flame targets, and cloud layers resembling smoke targets. These traits affect the precision of wildfire detection and elevate the likelihood of false alarms. Additionally, since drones are edge devices with limited computational resources, efforts to improve model accuracy must also consider the model’s parameters and computational complexity.

Many scholars have conducted targeted research on the above issues. Addressing the problems of variable target scales in wildfires and the high proportion of tiny targets in the initial stages of a fire, Zhang et al. [

2] enhanced small target recognition through the BRA-MP downsampling module, achieving an AP of 87.0% on a self-built dataset, a 2.3% improvement over the original YOLOv7. Yan et al. [

3] proposed the dense pyramid pooling module MCCL, which improves the model’s small target detection capability by integrating feature maps of different scales, resulting in a 1.1% increase in mAP; Cao et al. [

4] designed the full-dimensional dynamic convolutional space pyramid (OD-SPP), which dynamically adjusts the weights of convolutional kernels to adapt to multi-view inputs, resulting in a 4% increase in the model’s mAP50; Li et al. [

5] optimized the feature allocation strategy by combining BiFPN with the eSE attention module, significantly reducing the small object miss rate; Jia et al. [

6] enhanced the model’s proficiency in detecting tiny objects by introducing a multi-head attention mechanism; Ye et al. [

7] integrated the k-nearest neighbor (k-NN) attention mechanism into the Swin Transformer, significantly boosting the model’s proficiency in detecting diminutive fireworks, resulting in an impressive bbox_mAP50 score of 96.4%. Yuan et al.’s [

8] FF module employs three parallel decoding paths to effectively cover the spatial distribution differences from ground fires to crown fires; Zheng et al.’s [

9] GBFPN network fuses contextual information through bidirectional cross-scale connections and Group Shuffle convolutions, improving the mAP for object detection by 3.3%; Li et al. [

10] achieve mAP50 of 80.92% on the D-Fire dataset by integrating the GD mechanism for multi-scale information fusion; Dai et al. [

11] replace the backbone network of YOLOv3 with the MobileNet network; Zhao et al. [

12] augment the YOLOv3 architecture with an additional detection layer to bolster its capacity for pinpointing minor targets. These studies establish important technical references for multi-scale wildfire detection.

Addressing the challenges of complex forest environments and severe background interference, Yuan et al. [

8] enhanced flame region responses through position encoding in their FA mechanism, maintaining an 89.6% recall rate in hazy conditions; Zheng et al. [

9] embedded the BiFormer mechanism to filter key features via dynamic sparse attention, reducing false positive rates by 51.3% in tree canopy occlusion scenarios; Sheng et al. [

13] utilized dilated convolutions to construct a spatial attention map, improving focus on smoke targets by 2.9%; Pang et al. [

14] introduced a coordinate attention mechanism, increasing recall to 78.69% in foggy scenarios; Yang et al. [

15] enhanced small object detection through a Coordinated Attention (CA), improving mAP50 by 2.53%; Qian et al. [

16] adopted the SimAM attention mechanism, achieving an mAP50 of 92.10%, an improvement of 4.31% over the baseline. These attention mechanisms effectively address the issue of complex background interference.

Drones and other edge devices have limited resources, so researchers are not only focusing on accuracy but also actively developing lightweight models. Zhang et al. [

17] further optimized the neck structure of YOLOv5s, replacing traditional components with the GC-C3 module and SimSPPF, reducing the number of parameters by 46.7%; Ma et al. [

18] introduced the lightweight cross-scale feature fusion module CCFM and the receptive field attention mechanism RFCBAMConv, reducing the number of parameters by 20.2% while maintaining an average accuracy of 90.2%; Yun et al. [

19] combined GSConv with VoV-GSCSP, reducing the computational complexity of the Neck layer by 30.6%; Sheng et al. [

13] replaced standard convolutions with GhostNetV2, achieving parameter compression through inexpensive convolution operations; Chen et al. [

20] used a lightweight initial network and parallel mixed attention mechanism (PMAM) to maintain a low parameter count while improving detection accuracy; Feng et al. [

21] employed GhostNetV2 and a hybrid attention mechanism to reduce the parameter count by 22.77%; Lei et al. [

22] used DSConv and GhostConv to reduce the model parameter count by 41%; Han et al. [

23] combined GhostNetV2 with multi-head self-attention to reduce the parameter count to 2.6 M while achieving 86.3% mAP. These lightweight designs provide feasible solutions for edge device deployment.

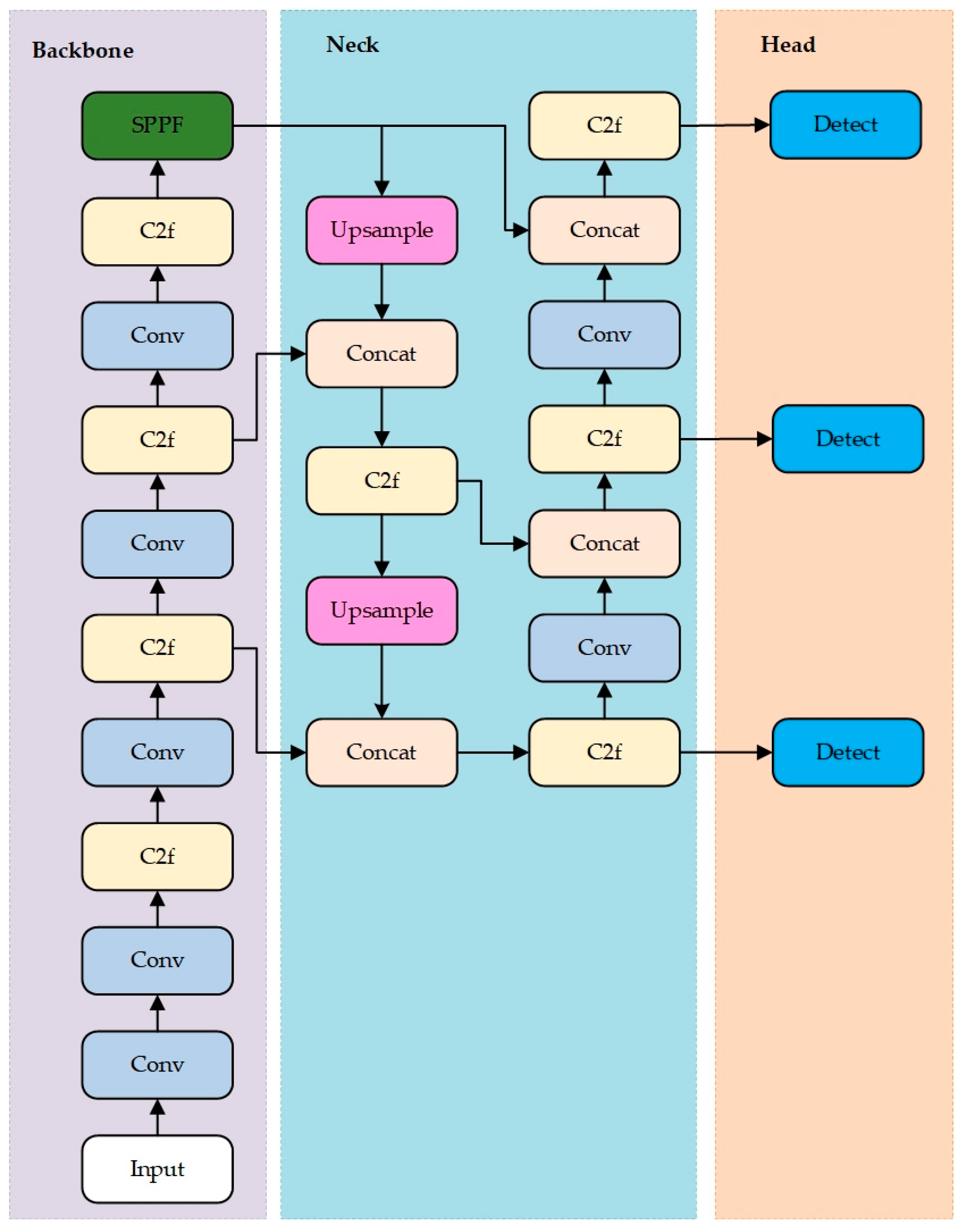

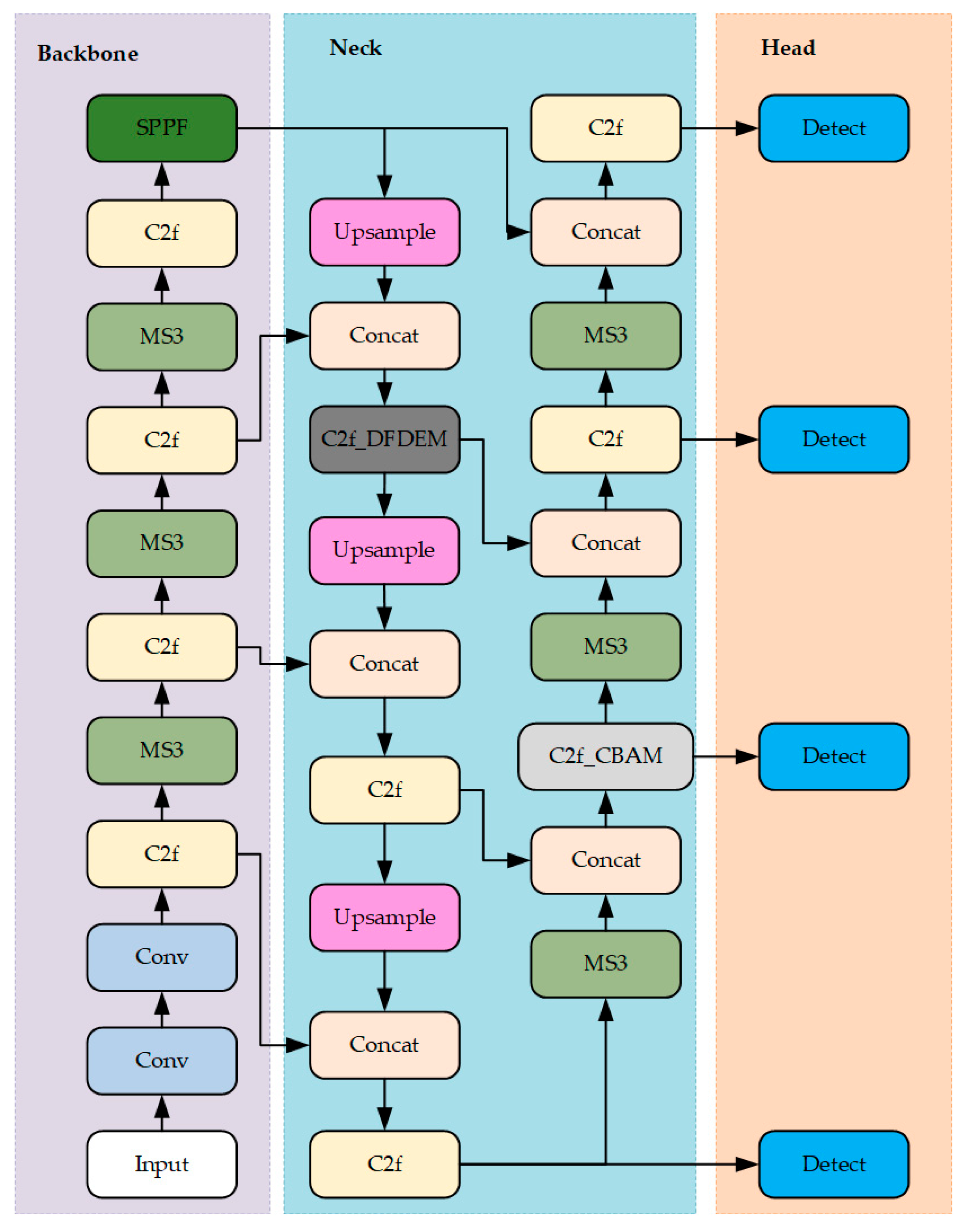

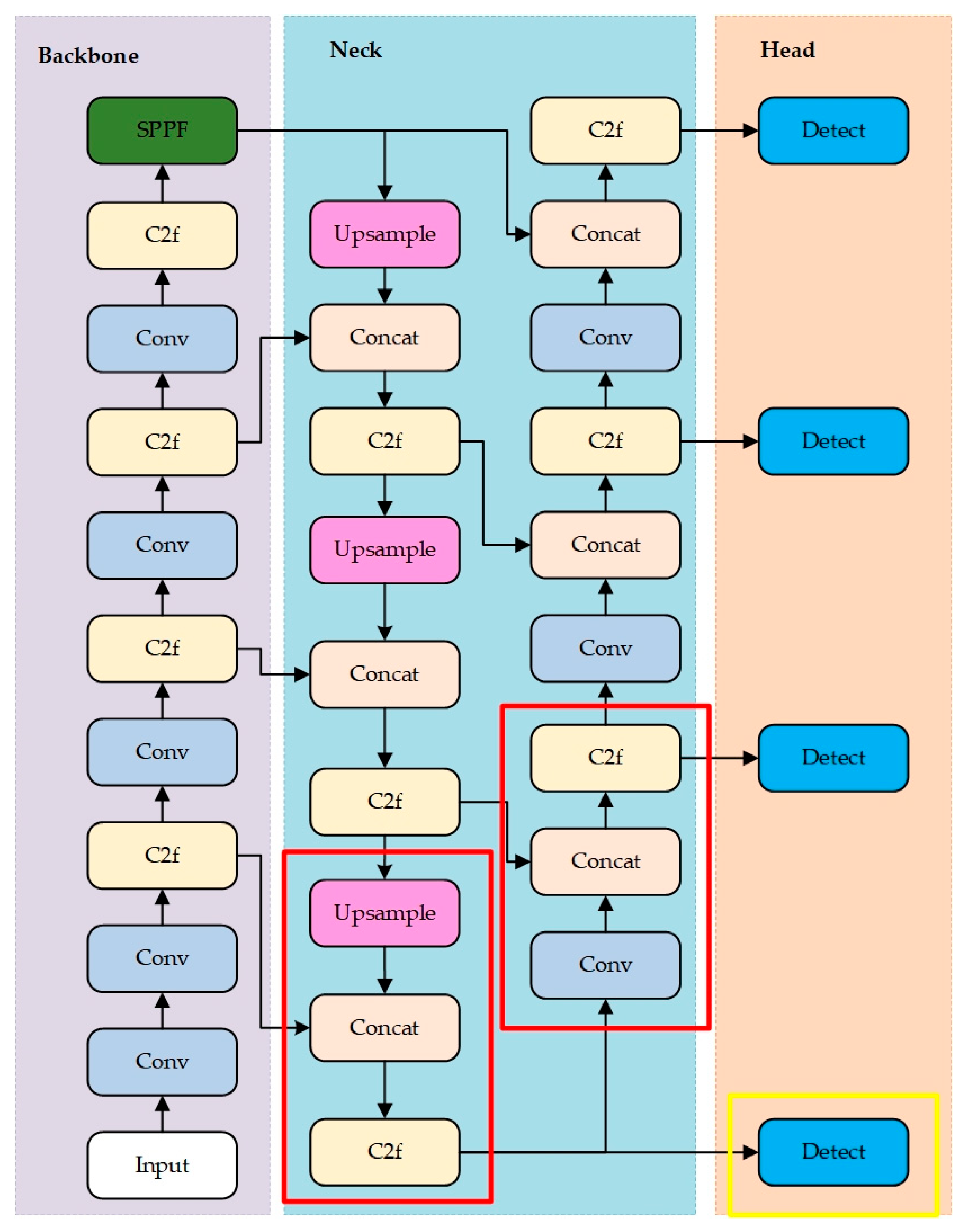

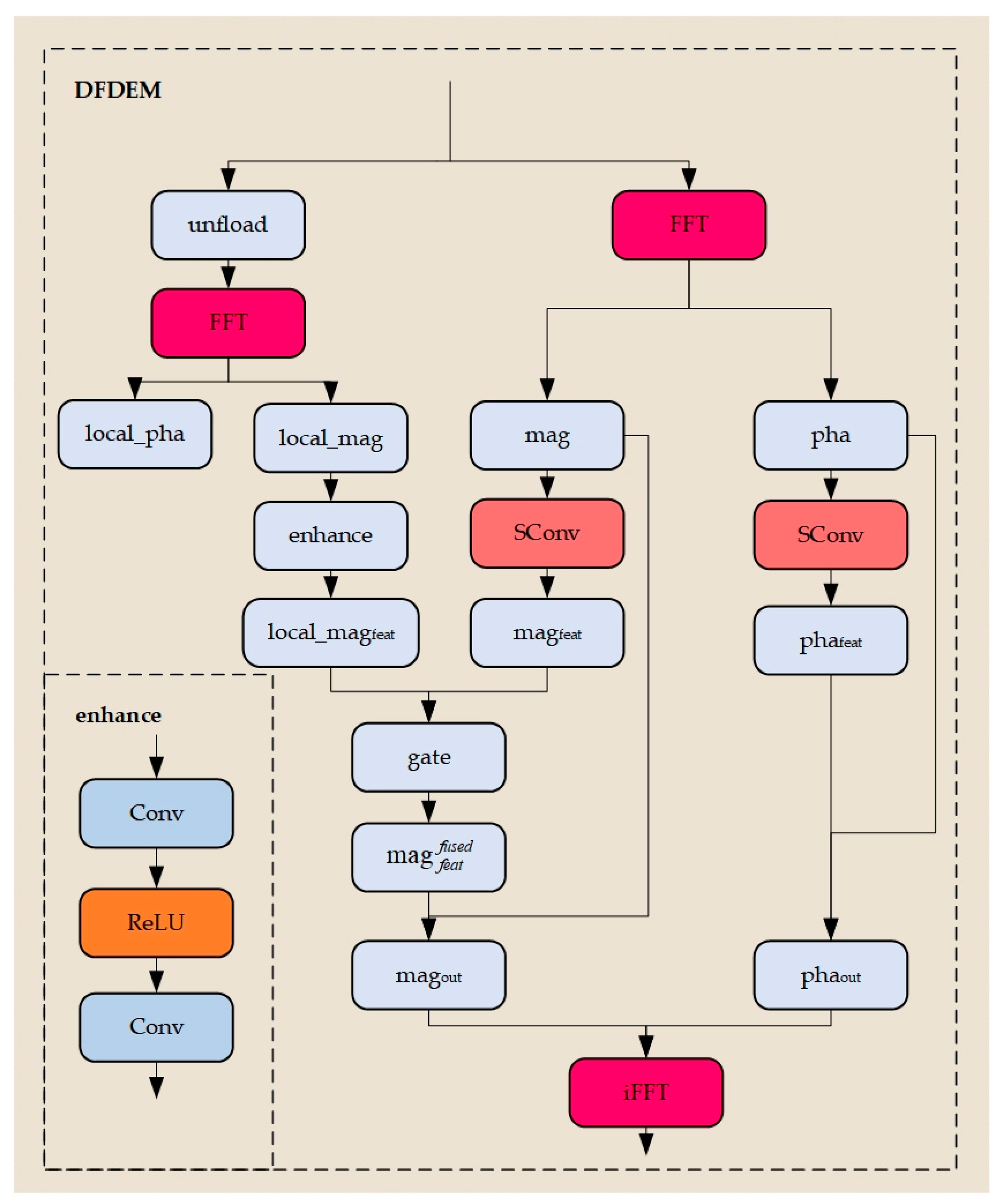

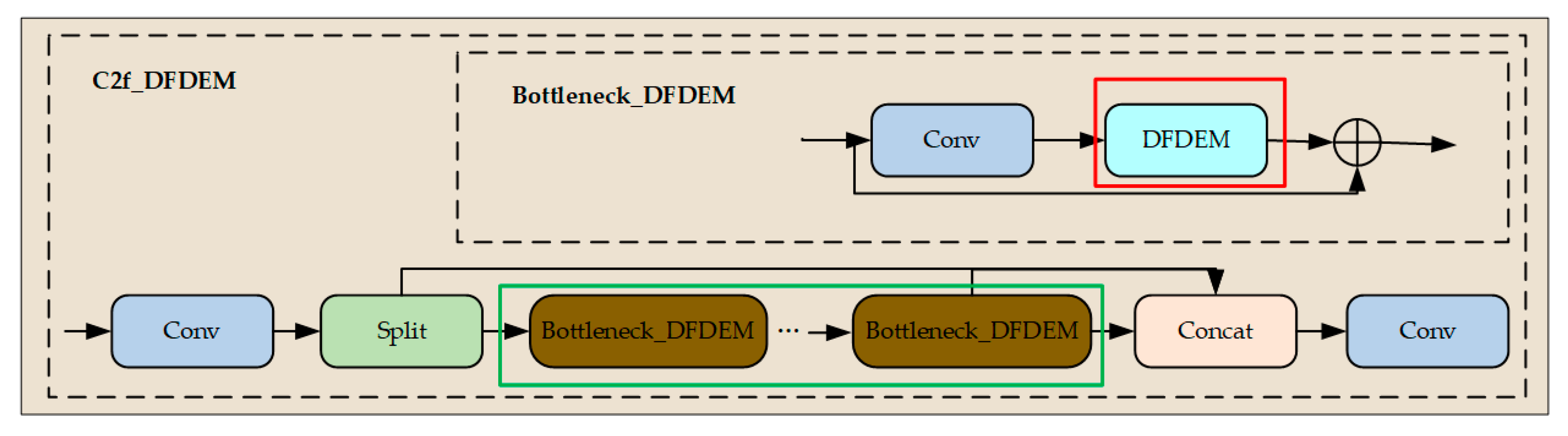

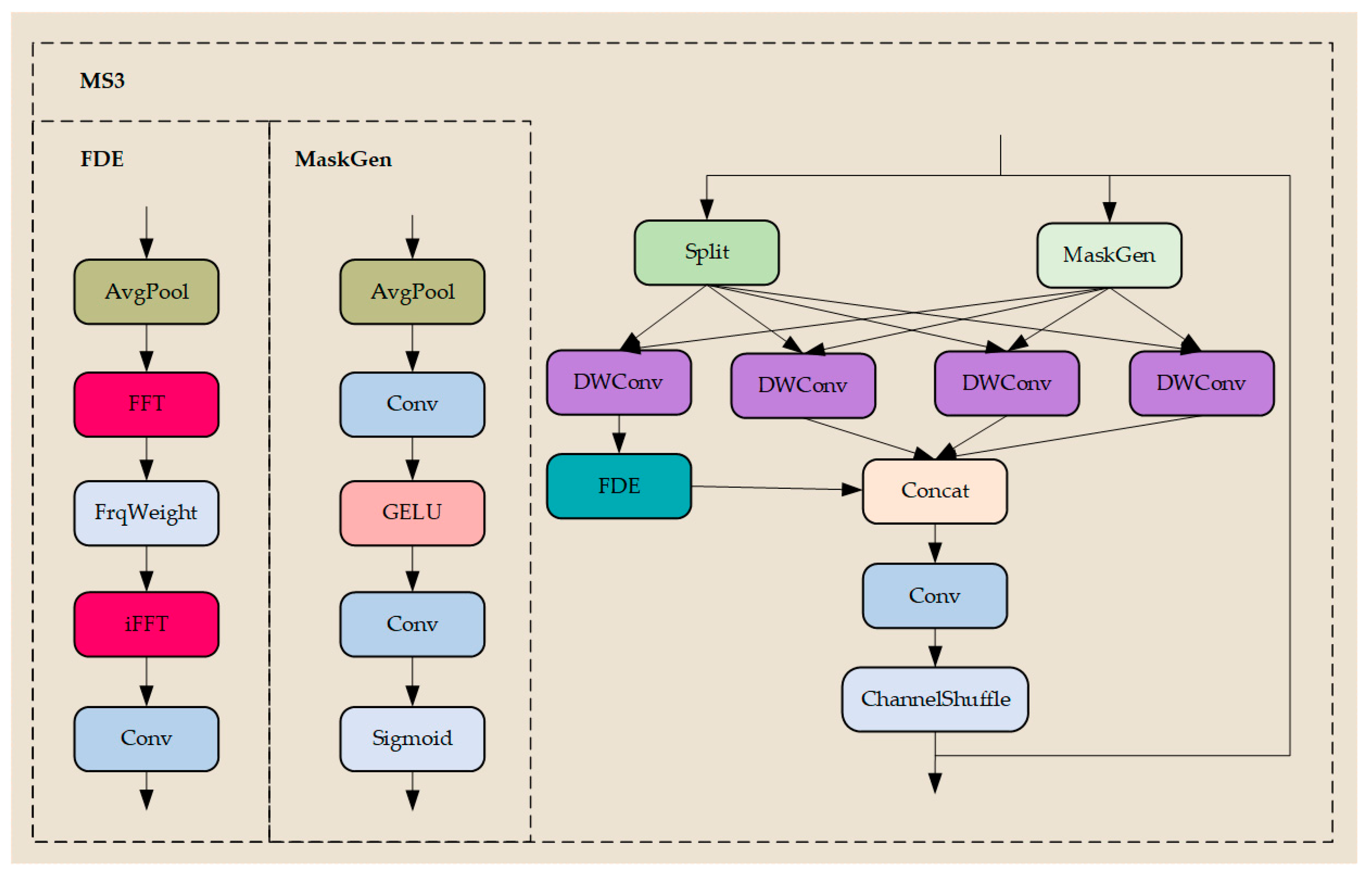

Despite significant progress achieved through numerous approaches addressing challenges in wildfire detection from drone perspectives, most existing methods struggle to simultaneously enhance small-target features while accommodating large targets within drone wildfire detection scenarios. This is particularly problematic given the substantial variation in target scales and the high proportion of small objects. Furthermore, while some models incorporate attention mechanisms to mitigate false positives and false negatives caused by complex background interference, these often incur increased computational costs, rendering them ill-suited to the resource constraints inherent in drone operations. To address the aforementioned issues, this paper presents DFE-YOLO, a wildfire detection model for drone perspectives based on dynamic frequency domain enhancement. Firstly, by expanding the traditional three-stage detection mechanism to a four-stage approach, a dedicated small-object feature processing layer and corresponding detection head are introduced, significantly enhancing the model’s detection capability for small-scale targets. Secondly, two core modules are innovatively designed during feature fusion: (1) the lightweight Dynamic Frequency Domain Enhancement Module (DFDEM), which captures detail information overlooked by conventional spatial convolutions through frequency domain analysis; (2) the Feature Enhancement Module (C2f_CBAM), integrating the CBAM attention mechanism within the C2f architecture to achieve dynamic weighting of key features. Finally, a multi-scale sparse sampling module (MS3) was constructed to substantially reduce computational complexity while preserving feature extraction capability, addressing resource constraints on drone platforms. Experimental results demonstrate that DFE-YOLO achieves superior performance on the public datasets Multiple lighting levels and Multiple wildfire objects Synthetic Forest Wildfire Dataset (M4SFWD) and Fire-detection, attaining mAP50 scores of 88.4% and 88.0%, respectively, with a 23.1% reduction in parameters compared to baseline models. This effectively balances detection accuracy with computational efficiency. The proposed method combines lightweight design with high precision, enabling accurate identification of multi-scale fire sources and providing a reliable solution for wildfire detection by unmanned aerial vehicles.

4. Discussion

This study innovatively proposes DFE-YOLO, a drone-based wildfire detection model enhanced with dynamic frequency domain augmentation, building upon YOLOv8. By incorporating a novel small object detection layer, it substantially enhances detection capabilities for small-scale targets. The lightweight Dynamic Frequency Domain Enhancement Module (DFDEM) and the target feature enhancement module C2f_CBAM strengthen the model’s ability to extract features from targets of varying scales and resist interference from complex backgrounds. The designed lightweight Multi-Scale Sparse Sampling Module (MS3) effectively reduces the model’s parameter count. Ablation studies validate the effectiveness of each module in drone-based wildfire detection. On the M4SFWD dataset, DFE-YOLO achieves 88.4% mAP50 and 50.6% mAP50-95 with only 2.3 million parameters—a 23.1% reduction compared to the baseline YOLOv8 model, representing the lowest parameter count among comparable models. Compared to models such as YOLOv10, Hyper-YOLO, and Drone-YOLO, it demonstrates superior detection accuracy while achieving a better balance between precision and parameter count.

At the practical application level, DFE-YOLO’s lightweight design enables deployment on embedded airborne hardware platforms with limited computational power. When integrated with Jetson Xavier (produced by NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA) on typical drone platforms such as the DJI M300 RTK (manufactured by SZ DJI Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China), it can fulfill real-time monitoring requirements. Given typical drone endurance times (25–35 min), the system can continuously monitor approximately 10–15 square kilometers of forest during a single flight, identifying and localizing fires in their early stages to significantly enhance firefighting response efficiency. However, the model’s current computational complexity (11.2 GFLOPs) remains challenging for sustained high-performance computing on airborne platforms. However, on hardware with more constrained power consumption, such as the Jetson Nano (developed by NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA), frame rates may experience a reduction. Subsequent work will focus on optimizing model structure parallelism and hardware utilization, developing dynamic inference mechanisms that adapt computation paths based on image complexity. This approach will reduce computational overhead in simple scenarios, enabling the model to maintain lightweight characteristics while further accelerating inference speeds.