Abstract

Mercury, a global pollutant with both persistence and high toxicity, has remained a focal point in environmental science research over the past half-century. As a key pathway in the terrestrial mercury cycle, plants actively assimilate gaseous elemental mercury (Hg0) through leaf stomata, constituting a critical pathway for terrestrial mercury cycling. The litterfall mercury concentration serves as a biological indicator to quantify vegetation’s mercury interception capacity, providing essential data for global mercury cycle modelling. To investigate this, 15 sampling sites throughout the country were selected, and litterfall was collected monthly for 12 consecutive months to determine the litterfall amount, composition, and leaf mercury dynamics. The results revealed that annual litterfall production ranged from 1.10–8.56 t·hm−2, with leaf components dominating (45.58%–89.11%). Furthermore, three seasonal litterfall patterns emerged: unimodal, bimodal, and irregular. Regarding mercury, the mercury concentration in leaf litter exhibited a certain seasonal variation trend, with the mercury content in leaves in most areas being higher in autumn and winter. Specifically, the mercury concentration in litterfall showed a significant negative correlation with latitude and a significant positive correlation with air temperature, precipitation, and litterfall amount (p < 0.05). Additionally, the concentration of Hg in dying leaves exhibited some geographical variations.

1. Introduction

Mercury (Hg), a typical heavy-metal pollutant, ranks among the top global contaminants in terms of ecological toxicity [1]. It exhibits persistence, mobility, and significant bioaccumulation potential [2]. Particularly, various Hg species can be transformed into methylmercury (MeHg) during biogeochemical processes, leading to strong neurotoxicity, which poses serious threats to the ecosystem and human health [3]. Given these characteristics, mercury pollution has been listed as a persistent toxic pollutant by the United Nations Environment Programme [4].

Atmospheric mercury pollution is characterised by significant transboundary transport, and its speciation distribution—gaseous elemental mercury (GEM), reactive gaseous mercury (RGM), and particulate-bound mercury (PBM)—directly influences its migration and transformation pathways [5]. GEM constitutes over 95% of total atmospheric mercury and is characterised by long-range transport [5]. Mercury deposition in forest systems is predominantly through dry deposition (accounting for 70%–85% of total deposition) [6], and approximately 75% of the dry deposition flux is realised through the litterfall vector [7]. This makes mercury input via litterfall the primary source of the mercury pool in forest soils [8].

Mercury in plant leaves primarily originates from the uptake of atmospheric gaseous elemental mercury. The plant assimilation of atmospheric GEM is recognised as a significant and relatively novel pathway for atmospheric mercury removal [9]. Current research on plant mercury primarily focuses on food safety risks associated with crops (rice, vegetables) [10,11], quantification of forest mercury pools [12], and differences in mercury enrichment among plant species and organs within urban functional areas [13]. In contrast, biogeochemical studies on mercury in plant leaves are relatively lacking. In recent years, leaf mercury has gained increasing attention as a tracer for atmospheric mercury cycling. Its efficient assimilation of atmospheric GEM through stomata has been confirmed [14,15], and the leaf mercury concentration shows a significant positive correlation with atmospheric GEM exposure levels [16,17]. Controlled experiments indicate that leaf mercury tends to stabilise after 2–3 months of growth [18]; however, natural observations show that tree leaves continuously accumulate mercury throughout the growing season [15]. This continuous absorption characteristic makes tree leaves a novel biological monitoring vector for regional atmospheric mercury pollution [19]. Mercury enriched by vegetation is transferred to the soil surface via litterfall; therefore, monitoring mercury concentration in litterfall is a potential method for studying vegetation’s mercury absorption capacity. Study of mercury concentrations in litterfall essentially captures the critical state of long-term biological accumulation of atmospheric mercury by plants before its transfer to the ground, avoiding the transient fluctuations seen in fresh leaves and also serving as an irreplaceable parameter for assessing the ecological risks of regional mercury deposition. Due to mercury’s characteristics of long-range atmospheric transport and global cycling [2], its pollution patterns are closely related to regional environmental backgrounds, the intensity of human activities, and ecosystem types. Relying solely on localised studies makes it difficult to fully understand its spatial differentiation patterns and driving mechanisms. Therefore, this study selected 15 sampling sites across China to analyse differences in litterfall production and leaf mercury concentration, alongside their influencing factors, aiming to provide data support and a theoretical foundation for future research on forest response mechanisms to mercury pollution. This study uniquely investigates both litterfall production and mercury concentration simultaneously across a national scale, revealing their coupled geographical patterns and driving factors. It highlights the integrated effects of tree species traits, climate, and geological background on mercury accumulation, addressing a gap left by prior localised or single-factor research.

2. Materials and Methods

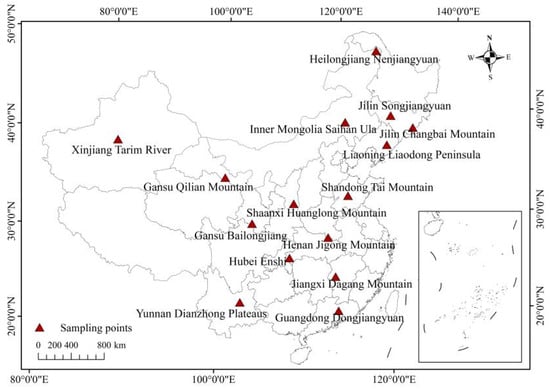

This study selected 15 sampling sites across China for litterfall sample collection (Figure 1, Table 1). At each site, the dominant tree species was chosen as the research subject. Litterfall samples were collected monthly for 12 consecutive months.

Figure 1.

Sampling points. Note: The map is produced based on the standard map with review number GS(2019)1822 downloaded from the Standard Map Service website of the State Administration of Surveying, Mapping and Geographic Information, with no modifications to the base map.

Table 1.

Sampling areas and species.

A unified standard was followed at all sampling sites. From August 2020 to October 2021, plots were established according to different stand types at each ecological station. Within these plots, 3–5 litterfall traps were placed to collect plant litterfall monthly (including leaves, branches, bark, reproductive organs, and others five major component). Litterfall was collected using the direct collection method. A 1 m × 1 m × 0.25 m collector made of nylon mesh with a 1.0 mm aperture was placed at each sampling point, with the mesh bottom positioned 0.5 m above the ground. The collected litterfall was placed in plastic sealable bags, brought back to the laboratory, and dried in an oven at 65 °C. Subsequently, the litterfall from each stand was separated into leaves, branches, bark, reproductive organs, and other parts, and then weighed. Plant samples from different organs were all pulverised and ground using the FW100 high-speed universal pulveriser (Sapeen Scientific Instruments (Shanghai) Corporation, Shanghai, China). After grinding, the samples were stored in plastic sealable bags, recording the stand type, litterfall type, sampling time, and ecological station name for subsequent analysis.

Tea leaves (GBW08001, 17 ng/g) were used as the standard reference material for establishing the calibration curve for determining litterfall leaf mercury concentration. Following the order of blank control—0.03 g, 0.06 g, 0.09 g, 0.12 g, 0.15 g, and 0.18 g—each sample was weighed in duplicate. After this measurement, the experimental data were checked to ensure that the absorbance of the blank group was below 0.0030 and the coefficient of determination (R2) reached or exceeded 0.999. Based on the established standard curve, weigh 0.02 g of each sample and directly measure the mercury concentration in the litter using a mercury analyser. The sample tray can hold 40 sample boats at a time. Considering the large number of samples to be analysed, group the sample boats on the tray into sets of 20. Include one blank group per tray, and randomly add one standard sample and one replicate group (repeated 3 times) to each set. After completion of the measurements, results were checked as follows: (1) Blank group absorbance < 0.0030; (2) Deviation among replicates within each group < 10% (if deviation among 3 replicates exceeds 10%, removing one replicate to achieve < 10% deviation is also considered valid); (3) Deviation of standard sample concentration from 17 ng·g−1 < 10%. If the blank group absorbance > 0.0030, redo the entire plate. If the blank group absorbance < 0.0030, but the parallel group or standard sample deviation of any group > 10%, the analysis results for that group of samples are considered invalid and must be retested.

Data on litterfall amount and mercury concentrations in litter from various organs at different study sites are presented as mean ± standard deviation. All data were initially collated and analysed using Excel 2021. Subsequently, IBM SPSS Statistics 21.0 was used for homogeneity of variance tests and one-way ANOVA analysis (p < 0.05 indicates a significant difference). Pearson correlation analysis was conducted between influencing factors—such as temperature and precipitation—and the litterfall leaf mercury concentration to study the differences in litterfall production and leaf mercury concentration across different regions, along with their influencing factors.

3. Results

3.1. Differences in Litterfall Production Across Regions

3.1.1. Annual Total Litterfall Production

In the 15 regions studied, the annual total litterfall production varied. Litterfall production generally decreased from the humid and warm southern and southwestern regions to the cold and arid northern and northwestern regions. The order from highest to lowest was as follows: Yunnan Dianzhong (8.56 ± 2.35 t·hm−2) > Gansu Bailongjiang (7.72 ± 0.69 t·hm−2) > Henan Jigongshan (6.55 ± 0.00 t·hm−2) > Hubei Enshi (6.54 ± 1.31 t·hm−2) > Jilin Songjiangyuan (6.51 ± 0.00 t·hm−2) > Shaanxi Huanglongshan (4.75 ± 0.23 t·hm−2) > Liaodong Peninsula (4.51 ± 0.95 t·hm−2) > Guangdong Dongjiangyuan (4.44 ± 1.45 t·hm−2) > Gansu Qilian Mountains (3.02 ± 0.45 t·hm−2) > Heilongjiang Nenjiangyuan (2.93 ± 0.21 t·hm−2) > Jiangxi Dagangshan (2.77 ± 0.61 t·hm−2) > Shandong Taishan (2.75 ± 0.48 t·hm−2) > Inner Mongolia Saihanwula (2.51 ± 0.95 t·hm−2) > Jilin Changbai Mountains (1.42 ± 0.15 t·hm−2) > Xinjiang Tarim River (1.10 ± 0.36 t·hm−2).

3.1.2. Annual Litterfall Production by Component

This study revealed differences in litterfall composition across regions (Table 2), with leaves, branch, bark, and reproductive organs being the main components. The results show that leaves constituted the largest proportion of litterfall in most tree species, followed by branches. Among the 15 regions studied, the proportion of leaves in litterfall ranged from 45.58% to 89.11%, while the proportion of branches ranged from 6.21% to 34.88%. Specifically, Betula platyphylla at the Heilongjiang Nenjiangyuan site had the highest leaf proportion, at 89.11%, with branches accounting for 9.55%. In contrast, Abies nephrolepis at the Jilin Changbai Mountains site had the lowest leaf proportion, at only 45.58%, followed by reproductive organs, at 29.16%.

Table 2.

Amount of litterfall and its proportion in each component of species in different regions.

3.1.3. Monthly Dynamics of Litterfall Production

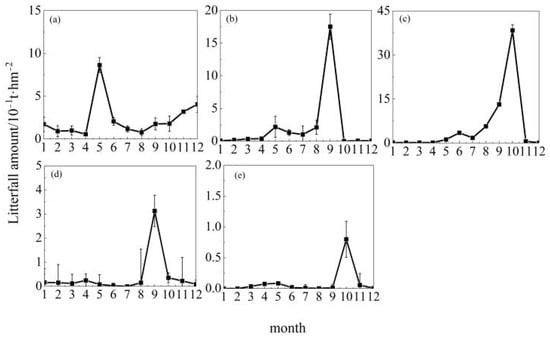

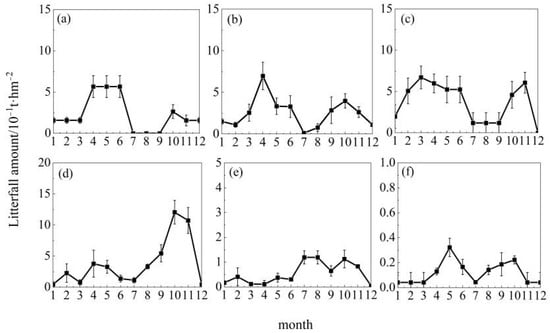

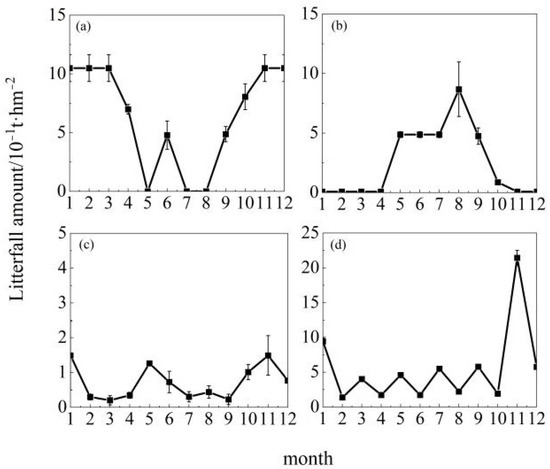

As shown in Figure 2, among the 10 tree species across the 15 study regions, Cunninghamia lanceolata at Jiangxi Dagangshan, Pinus tabuliformis at Shaanxi Huanglongshan, Quercus mongolica at Jilin Songjiangyuan and Inner Mongolia Saihanwula, and Populus euphratica at Xinjiang Tarim River exhibited unimodal patterns. However, the timing of peak litterfall production varied: Cunninghamia lanceolata at Jiangxi Dagangshan peaked in May; Pinus tabuliformis at Shaanxi Huanglongshan and Quercus mongolica at Inner Mongolia Saihanwula peaked in September; and Quercus mongolica at Jilin Songjiangyuan and Populus euphratica at Xinjiang Tarim River both peaked in October. On the other hand, as shown in Figure 3, Metasequoia glyptostroboides at Gansu Qilian Mountains, Cunninghamia lanceolata at Guangdong Dongjiangyuan, Abies nephrolepis at Jilin Changbai Mountains, Pinus densiflora at Liaodong Peninsula and Shandong Taishan, and Liriodendron chinense at Hubei Enshi exhibited bimodal patterns. Specifically, Metasequoia glyptostroboides at Gansu Qilian Mountains peaked in April with another smaller peak in October; Cunninghamia lanceolata at Guangdong Dongjiangyuan peaked in March with another smaller peak in November; Abies nephrolepis at Jilin Changbai Mountains reached its highest litterfall in May and maintained high levels in October; Pinus densiflora at Liaodong Peninsula had a minor peak in April and the highest peak in October; Pinus densiflora at Shandong Taishan had high litterfall from April to June and formed another minor peak in October; Liriodendron chinense at Hubei Enshi reached its annual peak from July to August and showed a second peak in October. As shown in Figure 4, the litterfall patterns of Metasequoia glyptostroboides at Gansu Bailongjiang, Betula platyphylla at Heilongjiang Nenjiangyuan, Cunninghamia lanceolata at Henan Jigongshan, and Yunnan Pine at Yunnan Dianzhong were classified as irregular.

Figure 2.

Monthly dynamics of unimodal litterfall. Note: (a) Jiangxi Dagangshan, (b) Inner Mongolia Saihan Ula, (c) Jilin Songjiangyuan, (d) Shaanxi Huanglongshan, (e) Xinjiang Tarim River. Each point indicates the mean monthly litterfall amount of the tree species.

Figure 3.

Monthly dynamics of bimodal litterfall. Note: (a) Shandong Taishan, (b) Gansu Qilian Mountain, (c) Guangdong Dongjiangyuan, (d) Liaoning Liaodong Peninsula, (e) Hubei Enshi, (f) Jilin Changbai Mountain. Each point indicates the mean monthly litterfall amount of the tree species.

Figure 4.

Monthly dynamics of irregular litterfall. Note: (a) Gansu Bailongjiang, (b) Heilongjiang Nenjiangyuan, (c) Yunnan Dianzhong Plateaus, (d) Henan Jigong Mountain. Each point indicates the mean monthly litterfall amount of the tree species.

3.2. Variation in Litterfall Leaf Mercury Concentration Across Regions and Influencing Factors

Significant differences in leaf mercury concentration were observed among different regions. Overall concentrations were significantly higher in central and eastern regions compared to the west. The concentrations ranked from high to low, as follows: Hubei Enshi (103.57 ± 16.24 ng·g−1) > Jiangxi Dagangshan (76.41 ± 14.21 ng·g−1) > Henan Jigongshan (46.29 ± 15.47 ng·g−1) > Guangdong Dongjiangyuan (46.22 ± 3.94 ng·g−1) > Gansu Bailongjiang (41.68 ± 10.11 ng·g−1) > Shandong Taishan (40.71 ± 8.50 ng·g−1) > Yunnan Dianzhong (36.56 ± 9.29 ng·g−1) > Jilin Changbai Mountains (31.37 ± 8.86 ng·g−1) > Gansu Qilian Mountains (29.53 ± 4.09 ng·g−1) > Liaodong Peninsula (29.07 ± 5.02 ng·g−1) > Jilin Songjiangyuan (25.03 ± 10.90 ng·g−1) > Shaanxi Huanglongshan (24.68 ± 1.45 ng·g−1) > Inner Mongolia Saihanwula (14.62 ± 6.09 ng·g−1) > Xinjiang Tarim River (12.56 ± 2.45 ng·g−1) > Heilongjiang Nenjiangyuan (11.95 ± 3.07 ng·g−1). This indicates that Liriodendron chinense tree leaves in Hubei Enshi more readily absorb atmospheric mercury. Hubei’s warm, moist climate gives leaves a longer growing season, which may increase mercury uptake, enhancing their mercury absorption capacity.

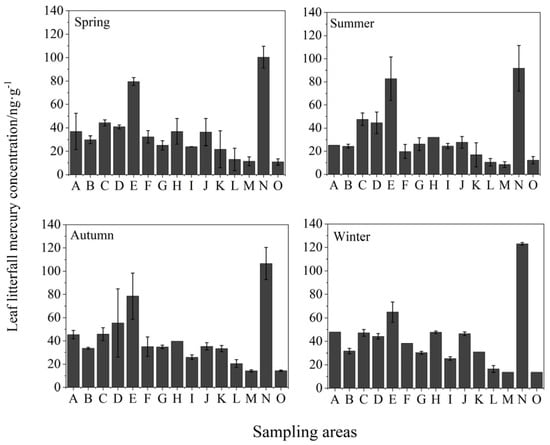

This study showed that the mercury content in leaves was higher in autumn and winter in most regions (Figure 5). Litterfall leaf mercury concentrations were lowest in summer and highest in winter in Gansu Bailongjiang, Jilin Changbai Mountains, Shandong Taishan, Yunnan Dianzhong, and Hubei Enshi. They were lowest in summer and highest in autumn in Gansu Qilian Mountains, Jilin Songjiangyuan, Inner Mongolia Saihanwula, and Heilongjiang Nenjiangyuan. In Guangdong Dongjiangyuan, concentrations were lowest in spring and highest in summer. In Henan Jigongshan, Liaodong Peninsula, Shaanxi Huanglongshan, and Xinjiang Tarim River, concentrations were lowest in spring and highest in autumn. In Jiangxi Dagangshan, concentrations were lowest in winter and highest in summer.

Figure 5.

Monthly dynamics of irregular litterfall. Note: A is Gansu Bailongjiang, B is Gansu Qilian Mountain, C is Guangdong Dongjiangyuan, D is Henan Jigong Mountain, E is Hubei Enshi, F is Jiangxi Dagangshan, G is Yunnan Dianzhong Plateaus, H is Jilin Changbai Mountain, I is Shandong Taishan, J is Liaoning Liaodong Peninsula, K is Shaanxi Huanglongshan, L is Inner Mongolia Saihan Ula, M is Jilin Songjiangyuan, N is Heilongjiang Nenjiangyuan, O is Xinjiang Tarim River. Each bar graph represents the monthly average leaf mercury concentration of each tree species in different seasons.

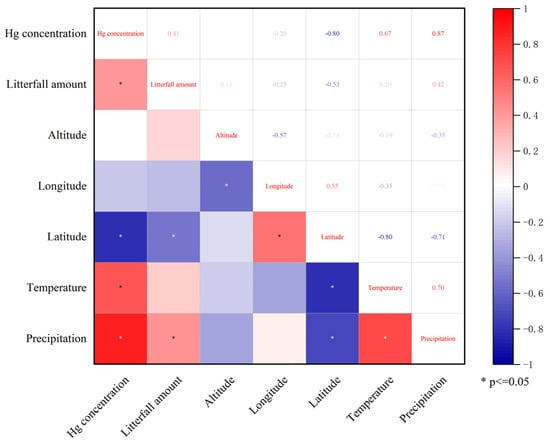

The results are shown in Figure 6. The precipitation and litterfall leaf mercury concentration exhibited significant positive correlations with litterfall production (p < 0.05), while latitude showed a significant negative correlation with litterfall production (p < 0.05). Precipitation, temperature, and litterfall production showed significant positive correlations with litterfall leaf mercury concentration (p < 0.05), while latitude showed a significant negative correlation with litterfall leaf mercury concentration (p < 0.05).

Figure 6.

Correlation analysis of mercury concentration in litterfall leaves, amount of litterfall and various influencing factors.

4. Discussion

Forest litterfall, as a key carrier in biogeochemical cycles, reflects the regulatory capacity of ecological processes within forest communities through its production dynamics [20]. The results of annual litterfall production across different tree species indicate that the tree species is an important factor influencing litterfall production, consistent with previous research conclusions [21]. Zhu [22], synthesising global forest litterfall data, found that although annual forest litterfall varies greatly, the total annual litterfall generally stabilises between 1.6 and 9.2 t·hm−2, a range within which the results of this study largely fall. But, the patterns may be driven more by species-specific traits than by geographic location.

Zhang et al. [23] showed that canopy structure parameters (stand density, basal area at breast height) are key regulatory factors for litterfall production. This study reveals the high litterfall production characteristics of Yunnan Dianzhong, Gansu Bailongjiang, and Henan Jigongshan. Their causes may be related to advantageous values of canopy parameters, but the biophysical coupling mechanism between these parameters and litterfall formation still needs to be elucidated through controlled experiments. Beyond this, the amount of litterfall is influenced not only by geographical factors such as climate, soil, and altitude but also by the species composition, thickness of the stand itself, and the degree of litter decomposition [24,25]. Correlation analysis in this study also found a significant positive correlation between precipitation and litterfall production (p < 0.05).

Leaves are the key organs for photosynthesis in woody plants. The temperature -regulated patterns governing leaf senescence hold significant ecological importance [20]. Seasonal temperature drops (e.g., in autumn) drive the concentrated senescence process of coniferous and broadleaved trees, forming the main component of forest floor litter. Broadleaved species (e.g., Liriodendron chinense) invest primary nutrients into leaf growth, achieving efficient nutrient cycling through rapid litterfall; hence, the leaf proportion exceeds 60%. Quercus mongolica, evolving in the severe cold of the north, has developed a special strategy: shedding a large number of branches in winter to reduce transpiration consumption, enhance resistance to wind and snow, and improve environmental adaptability [20]. Coniferous and broadleaved species differ significantly in organ allocation: broadleaved trees prioritise developing photosynthetic organs, while coniferous trees reinforce stress-resistant structures. The differences in biomass allocation between these two types of trees reveal their ecological trade-off mechanisms for resource acquisition and stress resistance, providing a theoretical basis for understanding the adaptive evolution of forest ecosystems [26].

The seasonal dynamics of forest litterfall are jointly regulated by the life-history strategies of community-building species and regional climate fluctuation characteristics, forming three typical patterns: unimodal, bimodal, and irregular [27]. This study found that the concentrated litterfall phenomenon in most tree species in autumn is closely related to photoperiod-regulated phenological responses, driven by resource reallocation, and achieved through programmed senescence mechanisms to maximise the transfer and storage of photosynthetic products [28]. Previous studies have shown that the seasonal dynamic pattern of litterfall in evergreen forests is bimodal, while that in deciduous broadleaved forests is generally unimodal [20,29]. Spring is the main leaf-out period for evergreen species; nutrient competition between new and old leaves inevitably triggers the senescence and litterfall of old leaves in spring [30]. Deciduous forests are strongly influenced by seasonality, with peak litterfall on the forest floor mostly occurring in autumn and winter. The conclusions of this study are also largely consistent with those of previous research [31].

Notably, although Cunninghamia lanceolata at Jiangxi Dagangshan and Pinus tabuliformis at Shaanxi Huanglongshan are evergreen species, their litterfall patterns are unimodal. This may be because Cunninghamia lanceolata experiences synchronous shedding of old leaves driven by rapid new leaf sprouting in spring, forming a litterfall peak [20]: a physiological adaptation to the optimal resource allocation in spring following metabolic inhibition by low winter temperatures in the subtropical monsoon climate. The litterfall peak of Pinus tabuliformis involves the concentrated shedding of senescent needles to reduce transpirational water loss, while strong light in the dry season accelerates photo-oxidative damage to needles, triggering protective leaf fall [32]. Although Liriodendron chinense in Hubei Enshi is a deciduous species, its litterfall pattern is bimodal. This may be due to mechanical leaf abscission caused by rainy weather in July–August in Hubei Enshi, while October represents normal seasonal leaf fall. For forest communities with the same litterfall dynamic pattern, driven by differences in species composition, their litterfall peaks also show significant variation. Cunninghamia lanceolata reaches its peak earlier than other species with unimodal patterns, which may be related to the species’ phenology and tolerance [20]. Furthermore, as temperatures warm in April–May, trees enter the new leaf-sprouting period, during which nutrient transfer to new tissues leads to concentrated abscission of old leaves, also forming a small spring litterfall peak [33]. The seasonal dynamics of litterfall are influenced by climatic conditions, species composition, and their biological characteristics [20]. Tree species with different biological characteristics, due to varying tolerances to environmental conditions, will consequently also affect the litterfall pattern.

This study found that leaf litter mercury concentration exhibits certain geographical differences. These regional variations may be attributed to the complex interactions of various natural and anthropogenic factors. The research results of Cao [34] indicate that regions with higher atmospheric mercury concentrations are mainly concentrated in areas with high population density and strong industrial activity in China, such as the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region, the Yangtze River Delta, the Pearl River Delta, and the Yunnan and Guizhou provinces in the southwest. However, in this study, regions with high mercury concentration values, such as Hubei Enshi (103.57 ± 16.24 ng·g−1) and Jiangxi Dagangshan (76.41 ± 14.21 ng·g−1), are likely driven by geologically Hg-enriched backgrounds: Enshi is located within a globally rare selenium-mercury paragenetic ore belt [35], where weathering of Hg-rich rocks may leads to extremely high soil background values, compounded by the persistent impact of historical metal mining. Simultaneously, dense coal combustion emissions from the Central China industrial belt further elevate plant mercury accumulation through atmospheric deposition [34]. Clearly, regions with high atmospheric mercury concentrations do not necessarily have high forest leaf mercury concentrations, which may be related to differences in mercury speciation, plant physiological barriers, environmental factors, etc. [36]. Future research should focus on the interactions between the mercury deposition flux and plant–environment interactions.

The humid climate regions of Guangdong Dongjiangyuan and Henan Jigongshan are probably more influenced by regional industrial transport and agricultural activities. Medium-to-low concentration areas in the north, such as Shandong Taishan and Gansu Bailongjiang, are affected by local industrial point sources or mining activities. Areas like Jilin Changbai Mountains and Liaodong Peninsula have relatively moderate concentrations due to the lower adsorption efficiency of mercury by the waxy leaves of coniferous forests [37]. The lowest values occur in remote, cold, or arid regions—Xinjiang Tarim River and Heilongjiang Nenjiangyuan—may due to their distance from pollution sources, Hg-poor soils, and atmospheric mercury deposition and plant metabolic activity suppressed by low temperatures; the low value in Inner Mongolia Saihanwula is directly related to weakly weathered soils in arid regions and limited anthropogenic input. Notably, the high-altitude cloud and fog processes in Yunnan Dianzhong may promote mercury uptake, while wetlands in Jilin Songjiangyuan reduce plant accumulation due to mercury volatilisation. The overall significantly higher concentrations in central and eastern regions compared to the west also reflect the superimposed influence of the long-range transport of atmospheric mercury in the East Asian monsoon region. Furthermore, studies show that the leaf age is proportional to the accumulated mercury concentration [38]. Deciduous broadleaved tree species have short leaf lifespans (less than 1 year), large leaf areas, numerous stomata, and high stomatal conductance, which favour atmospheric mercury uptake by leaves, resulting in higher mercury accumulation rates. Conversely, coniferous tree species primarily have long needle lifespans (2–5 years), making changes in leaf mercury concentration less apparent over short monitoring periods [39]. In summary, this spatial differentiation pattern is shaped by the geological background, climate-driven deposition efficiency, vegetation physiological characteristics, and the regional intensity of industrial emissions, mining, and agricultural activities.

In terms of the seasonal variation pattern of litterfall leaf mercury concentration, leaf mercury concentration in most regions gradually increased during the growing season, which is consistent with the findings of Ericksen [18] and Wang Qi et al. [40]. Research indicates that after gaseous elemental mercury (Hg0) migrates into leaves through stomata, it is oxidised to divalent mercury (Hg2+). This form of mercury binds and is retained within the leaf via coordination bonds with sulphur-containing organic compounds, such as cysteine [41]. This biological fixation mechanism results in the continuous accumulation of leaf mercury concentration as leaves develop. Leaf mercury concentration exhibited a certain seasonal variation pattern, with higher mercury content in leaves observed during autumn and winter in most areas. The highest leaf mercury concentration in Jiangxi Dagangshan during summer might be related to its high litterfall production in summer. Correlation analysis results also indicated a significant positive correlation between litterfall leaf mercury concentration and litterfall production (p < 0.05). However, leaf mercury concentration is not only influenced by litterfall production but also by meteorological factors [42]. The results of this study show that there was a significant negative correlation between litterfall leaf mercury concentration and latitude (p < 0.05), and a significant positive correlation with precipitation (p < 0.05).

5. Conclusions

This study systematically monitored and analysed litterfall and litterfall leaf mercury concentrations across 15 typical forest ecosystems in China, revealing the geographical variation patterns and key influencing factors. The main conclusions are as follows:

Litterfall Production and Composition: Annual litterfall production ranged from 1.10 to 8.56 t·hm−2, generally decreasing from the humid and warm southern and southwestern regions to the cold and arid northern and northwestern regions. Leaves constituted the largest proportion (45.58%–89.11%) of litterfall, followed by branches (6.21%–34.88%). The organ allocation strategies of different tree species reflect ecological trade-off mechanisms between resource acquisition and stress resistance.

Seasonal Dynamics of Litterfall: Monthly litterfall dynamics exhibited three typical patterns: unimodal, bimodal, and irregular, primarily regulated by the life-history strategies of tree species and regional climate characteristics. Evergreen species (e.g., some Cunninghamia lanceolata, Pinus yunnanensis) often showed bimodal or irregular patterns, while deciduous species (e.g., Quercus mongolica, Populus euphratica) typically showed unimodal patterns. Exceptions exist (e.g., bimodal pattern for Liriodendron chinense in Hubei Enshi), indicating significant influences from species-specific biological traits, phenology, and local climate (e.g., precipitation, light).

Geographical Variation in Leaf Mercury Concentration: Significant spatial heterogeneity was observed in litterfall leaf mercury concentration, with overall significantly higher values in central and eastern regions compared to the west. The highest value was found in Hubei Enshi (103.57 ± 16.24 ng·g−1), and the lowest in Heilongjiang Nenjiangyuan (11.95 ± 3.07 ng·g−1). This spatial pattern results from the complex interplay of various natural and anthropogenic factors, including geological background (e.g., the Se-Hg paragenetic ore belt in Enshi), climate-driven mercury deposition efficiency, vegetation physiological characteristics (e.g., leaf lifespan, stomatal characteristics), and the intensity of regional industrial emissions, mining, and agricultural activities.

Seasonal Variation in Leaf Mercury Concentration: In most regions, the mercury concentration in litterfall leaves showed an accumulating trend during the growing season and reached higher levels in autumn and winter. This seasonal dynamic is closely related to the continuous uptake of atmospheric gaseous elemental mercury (Hg0) by leaves and its biological fixation mechanism (binding to sulphur-containing organic compounds) within the leaf tissue.

Correlation with Influencing Factors: Correlation analysis indicated that litterfall production showed a significant positive correlation with precipitation and a significant negative correlation with latitude. Litterfall leaf mercury concentration showed significant positive correlations with precipitation, temperature, and litterfall production and a significant negative correlation with latitude. This confirms that hydrothermal conditions, by promoting plant growth, metabolism, and mercury uptake, along with influencing atmospheric mercury deposition, jointly regulate the mercury enrichment capacity of vegetation.

In summary, the characteristics of litterfall and its mercury load in typical forest ecosystems in China exhibit distinct spatial variations and seasonal dynamics, primarily influenced by climatic factors (temperature, precipitation), geographical factors (latitude), and tree species’ biological characteristics. This study provides essential data support and a theoretical foundation for understanding the role of forest ecosystems in the mercury biogeochemical cycle and for assessing the ecological risks of regional mercury pollution.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition, X.N. and B.W.; software, Z.W.; validation, writing—review and editing, S.H. and X.N.; formal analysis, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, visualisation, S.H.; investigation, J.Z.; resources, R.H. and D.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Project on Accounting for Forest and Grassland Resources and Ecosystem Services in China: “Forest and Grassland Ecosystem Assessment and Value Accounting”.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following national positioning observation and research stations for their support and cooperation: Gansu Bailongjiang Forest Ecosystem Station, Gansu Qilian Mountains Forest Ecosystem Station, Gansu Xinglongshan Forest Ecosystem Station, Guangdong Dongjiangyuan Forest Ecosystem Station, Henan Jigongshan Forest Ecosystem Station, Heilongjiang Nenjiangyuan Forest Ecosystem Station, Hubei Enshi Forest Ecosystem Station, Jilin Songjiangyuan Forest Ecosystem Station, Jilin Changbai Mountains Forest Ecosystem Station, Jiangxi Dagangshan Forest Ecosystem Station, Liaoning Liaodong Peninsula Forest Ecosystem Station, Inner Mongolia Saihanwula Forest Ecosystem Station, Shandong Taishan Forest Ecosystem Station, Shaanxi Huanglongshan Forest Ecosystem Station, Xinjiang Tarim River Poplar Forest Ecosystem Station, and Yunnan Dianzhong Plateau Forest Ecosystem Station. Thanks are also extended to Xu Tingyu, Wang Qiang, Du Jiajie, and Liu Pingping for their assistance in sample measurement.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Feng, X.B.; Chen, J.B.; Fu, X.W.; Hu, H.Y.; Li, P.; Qiu, G.L.; Yan, H.Y.; Yin, R.S.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, W. Progresses on Environmental Geochemistry of Mercury Bulletin of Mineralogy. Petrol. Geochem. 2013, 32, 503–530. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.H. Review of Mercury Pollution Distribution Status Research at Home and Abroad. Environ. Prot. Sci. 2008, 1, 38–41. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Zhou, Q.X. Atmospheric Mercury Pollution in Typical Cities of China and Its Influences on Human Health. Asian J. Ecotoxicol. 2014, 9, 832–842. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, X.B.; Wang, X.; Sun, G.Y.; Yuan, W. Research Progresses and Challenges of Mercury Biogeochemical Cycling in Global Vegetation Ecosystem. Earth Sci. 2022, 47, 4098–4107. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, N.; Qian, G.L.; Duan, L.; Zhao, M.F.; Xiu, G.L. Correlation of Speciated Mercury with Carbonaceous Components in Atmospheric PM2. 5 in Shengsi Region. Environ. Sci. 2017, 38, 438–444. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Bao, Z.D.; Lin, C.J.; Yuan, W.; Feng, X.B. Assessment of Global Mercury Deposition through Litterfall. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 8548–8557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Yuan, W.; Feng, X.B. Global Review of Mercury Biogeochemical Processes in Forest Ecosystems. Prog. Chem. 2017, 29, 970–980. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, Z.C.; Zhang, X.S.; Wang, Z.W.; Ci, Z.J. Mercury in leaf litter in typical suburban and urban broadleaf forests in China. J. Environ. Sci. 2011, 23, 2042–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.H.; Feng, X.B. Environmental Mercury and Arsenic Pollution and Health, 1st ed.; Hubei Science and Technology Press: Wuhan, China, 2019; pp. 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, F.H.; Yang, L.; Xu, X.F.; Shan, M.N.; Chen, Z.M.; Bao, Y.L.; Pu, Y.X. Lead, cadmium, total mercury and total arsenic contamination in real estate grains and vegetables in Inner Mongolia, 2017–2019. J. Hyg. Res. 2021, 50, 846–848. [Google Scholar]

- Pelcova, P.; Ridoskova, A.; Hrachovinova, J.; Grmela, J. Evaluation of mercury bioavailability to vegetables in the vicinity of cinnabar mine. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 283, 117092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sa, R.; Wang, Z.W.; Xu, Z.H.; Zhao, Q.P.; Zhang, X.S. Distribution characteristics of mercury concentration and estimation biomass mercury pools in different natural forests of Xiaoxing’an Mountain. Acta Sci. Circumstantiae 2021, 41, 4703–4709. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Zhou, Z.F. Mercury pollution characteristics of plants and soils in different functional areas in Qingdao city. Ecol. Environ. 2008, 2, 802–806. [Google Scholar]

- Rea, A.W.; Lindberg, S.E.; Scherbatskoy, T.; Keeler, G.J. Mercury accumulation in foliage over time in two northern mixed-hardwood forests. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2002, 133, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laacouri, A.; Nater, E.A.; Kolka, R.K. Distribution and uptake dynamics of mercury in leaves of common deciduous tree species in Minnesota, U.S.A. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 10462–10470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericksen, J.A.; Gustin, M.S. Foliar exchange of mercury as a function of soil and air mercury concentrations. Sci. Total Environ. 2004, 324, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Z.C.; Zhang, X.S.; Wang, S.; Ci, Z.J.; Kong, X.R.; Wang, Z.W. The linear accumulation of atmospheric mercury by vegetable and grass leaves: Potential biomonitors for atmospheric mercury pollution. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 6337–6343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericksen, J.A.; Gustin, M.S.; Schorran, D.E.; Johnson, D.W.; Lindberg, S.E.; Coleman, J.S. Accumulation of atmospheric mercury in forest foliage. Atmos. Environ. 2003, 37, 1613–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, D.D.; Mcclenahen, J.R.; Hutnik, J.R. Selection of a biomonitor to evaluate mercury levels in forests of Pennsylvania. Northeast. Nat. 2002, 9, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.L.; Mao, Z.J.; Sun, T.; Song, Y. Dynamic of litterfall in ten typical community types of Xiaoxing’an Mountain, China. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2013, 33, 1994–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, L.L.; Zhang, H.D.; Yi, D.; Huang, X. Dynamics and decomposition characteristics of litter of two typical forest species. Liaoning For. Sci. Technol. 2024, 3, 11–16+68. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, B.K. The Dynamic of Litterfalls in Broad-Leaved Korean Pine Mixed Forest in Changbai Mountain. Master’s Thesis, Northeast Normal University, Jilin, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.D.; Liu, Y.C.; Gu, F.X.; Guo, M.M.; Miu, N.; Liu, S.R. Litter composition and its dynamic in five main forest types in subalpine areas of west Sichuan, China. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2019, 39, 502–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, M.L.; Zhu, C.G.; Zhai, C.B.; Qu, Y. Water-holding Capacity of Litter and Soil in Three Kinds of Soil and Water Conservation Forests in Taihang Mountains of Hebei Province. Bull. Soil Water Conserv. 2017, 37, 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Y.T. The Litter Storage Capacity and Water—holding Characteristics of 5 Typical Forests in Baihua Mountain. For. Resour. Manag. 2019, 3, 113–117+146. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.P.; Wang, X.P.; Zhu, B.; Zong, Z.J.; Peng, C.H.; Fang, J.Y. Litterfall Production in Relation to Environmental Factors in Northeast Chnia’s Forests. J. Plant Ecol. 2008, 32, 1031–1040. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, X.X.; Wang, Z.C.; Li, C.; Guo, H.; Jin, K.C. Seasonal dynamics of the litter fall production of evergreen broadleaf forest and its relationships with meteorological factors at Tiantong of Zhejiang province. J. Cent. South Univ. For. Technol. 2017, 37, 73–78. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Z.Q.; Li, B.H.; Bai, X.J.; Lin, F.; Shi, S.; Ye, J.; Wang, X.G.; Hao, Z.Q. Composition and seasonal dynamics of litter falls in a broad-leaved Koraen pine (Pinus koraiensis) mixed forest in Chnagbai Mountains, Northeast China. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2010, 21, 2171–2178. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.Y. Review on the study of the forest litter fall. Adv. Ecol. 1989, 6, 82–89. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.C. Leaffall Phenology and Patterns of 22 Evergreen Woody Species in Subtropical Evergreen Forest in Tiantong Zhejiang, China. Master’s Thesis, Zhejiang Normal University, Zhejiang, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zong, H.; Yao, Y.N.; Liu, L.; Zhang, L. Accumulation amounts and water holding characteristics of litter in the typical 8 tree species of Linpan settlements in the western Sichuan Plain. Ecol. Sci. 2024, 43, 18–26. [Google Scholar]

- Da, A.; Han, H.R.; Li, H.Y.; Wu, H.F.; Cheng, X.Q. Plant-litter-soil stoichiometric characteristics of typical plantation forests and their interaction in loess hilly and gully region. Sci. Soil Water Conserv. 2024, 22, 119–128. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.L.; Tao, L.; Lv, Z.W. Study on the characteristic of litterfall of Picea likiangensis var. linzhiensis forest in Tibet. Acta Phytoecol. Sin. 1998, 22, 566–570. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, S.Z. Optimization of Anthropogenic Atmospheric Mercury Emission Inventory and Evaluation of Co-benefit Control Effectiveness in China. Master’s Thesis, Nanjing University, Nanjing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, X.; Qian, H.D.; Wu, X.M. Geochemical and Genetic Characteristics of Selenium Ore Deposit in Shuanghe, Enshi, Hubei Province. Geol. J. China Univ. 2006, 1, 83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J. Spatial Distribution Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Total Mercury in Picea Schrenkiana Forests in Tianshan Mountains. Master’s Thesis, Xinjiang University, Xinjiang, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G.; Sun, T.; An, S.W.; Ma, M. Mercury Release Flux and Its Influencing Factors Under Four Typical Vegetation Covers at Jinyun Mountain, Chongqing. Environ. Sci. 2017, 38, 4774–4781. [Google Scholar]

- Fleck, J.A.; Grigal, D.F.; Nater, E.A. Mercury Uptake by Trees: An Observational Experiment. Water Air Soil Pollut. 1999, 115, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Yuan, W.; Zhang, Y.T.; Chang, S.L. Spatial and Temporal Variations of Leaf Mercury Concentration in Urumqi: Implications of Environmental Significance. Earth Environ. 2022, 50, 360–367. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.J.; Zhou, L.M.; Zheng, X.M. Temporal and spatial characteristics of mercury concentrations in leaves of common deciduous tree species in parks of Shanghai and its environmental implications. Environ. Chem. 2021, 40, 232–239. [Google Scholar]

- Khwaja, A.R.; Bloom, P.R.; Brezonik, P.L. Binding constants of divalent mercury (Hg2+) in soil humic acids and soil organic matter. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 844–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Y.; Xiu, G.L.; Zhang, D.N.; Zhang, M.G.; Zhang, R.J. Total gaseous mercury in ambient air of shanghai: Its seasonal variation in relation to meteorological condition. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 35, 155–158+255. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).