Transcriptomic Analysis of Anthocyanin Degradation in Salix alba Bark: Insights into Seasonal Adaptation and Forestry Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

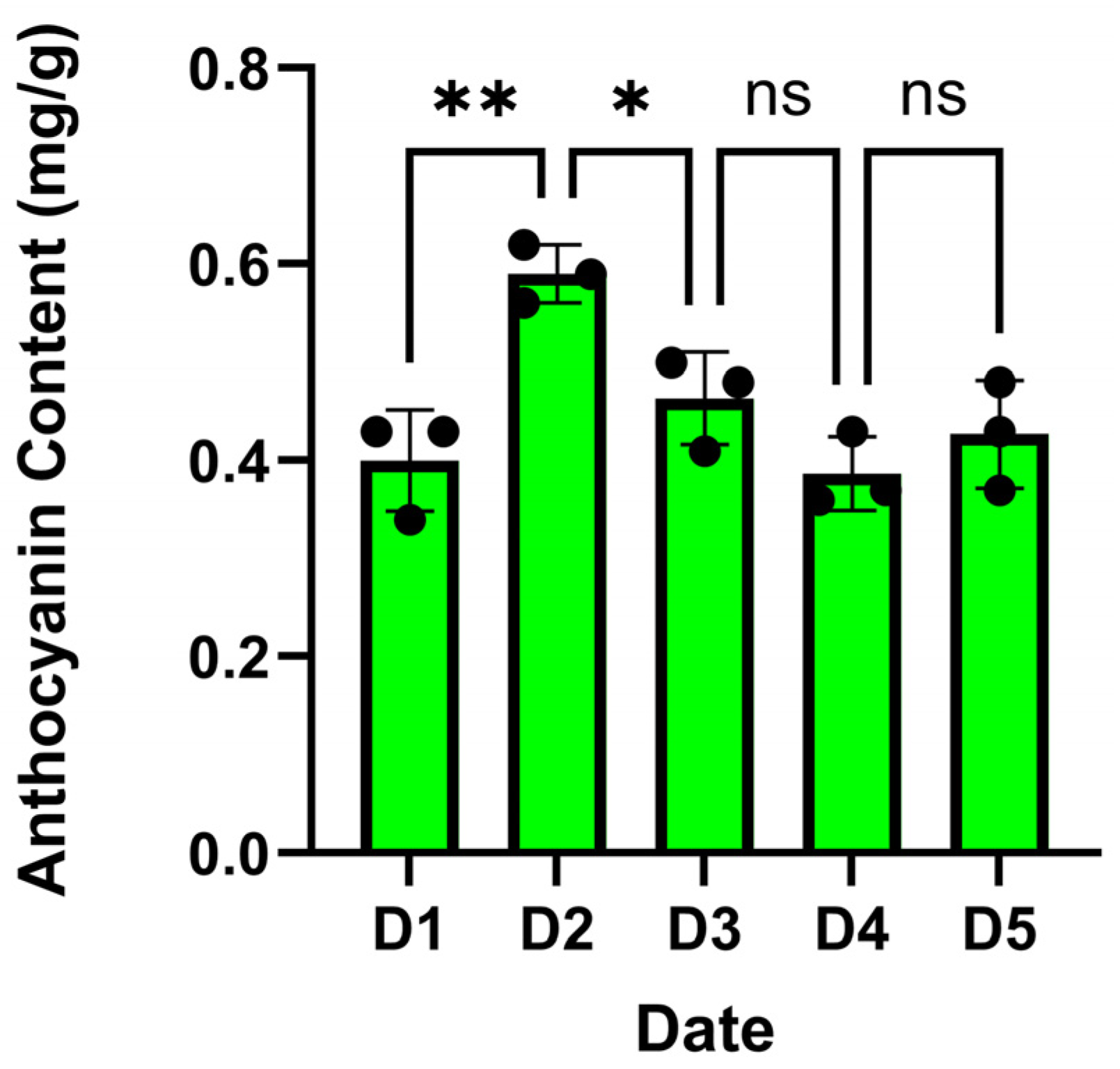

2.1. Differential Anthocyanin Content in Salix alba Bark During Color Transitions

2.2. Transcriptome Sequencing and Assembly

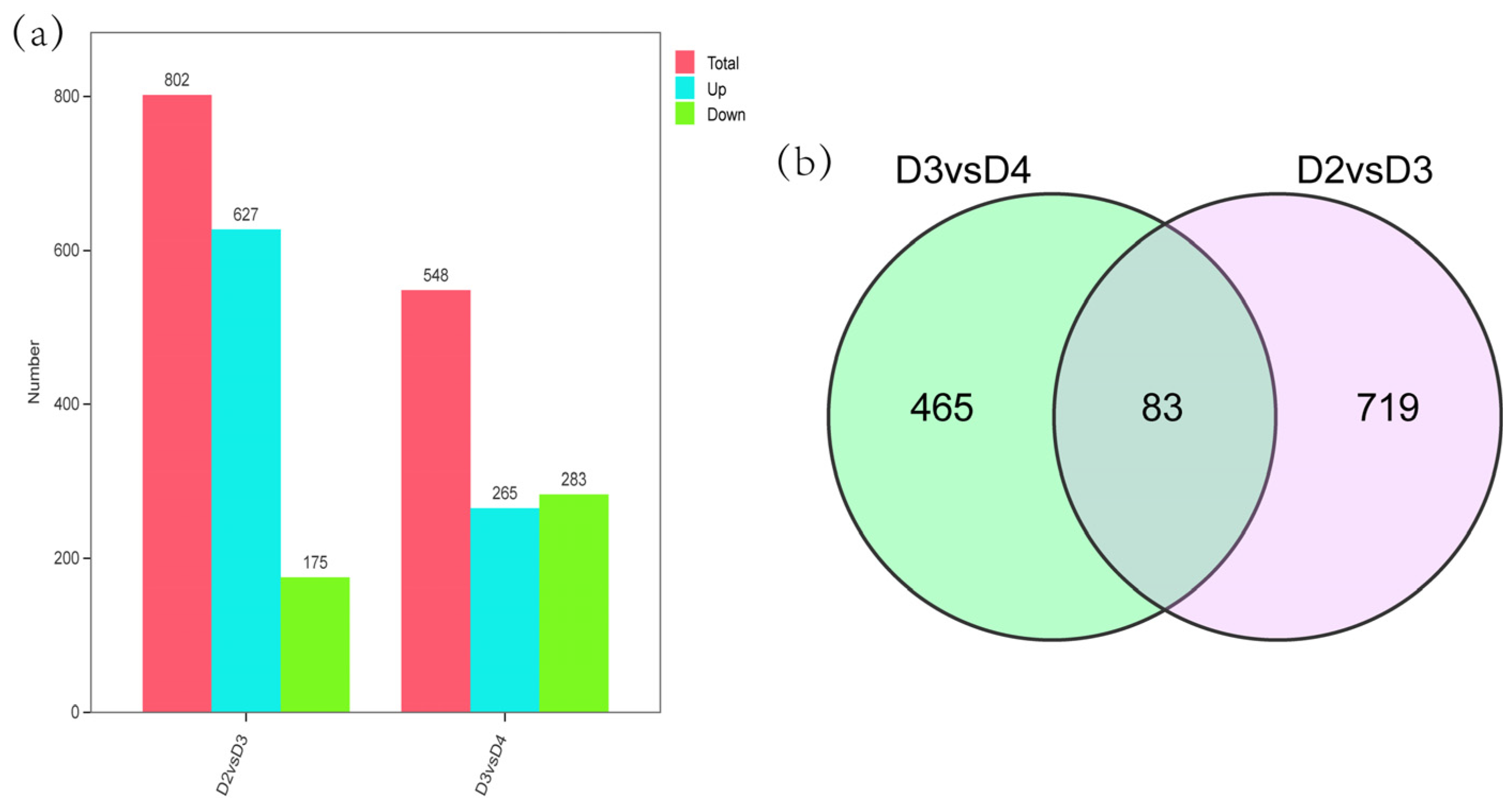

2.3. Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) Analysis

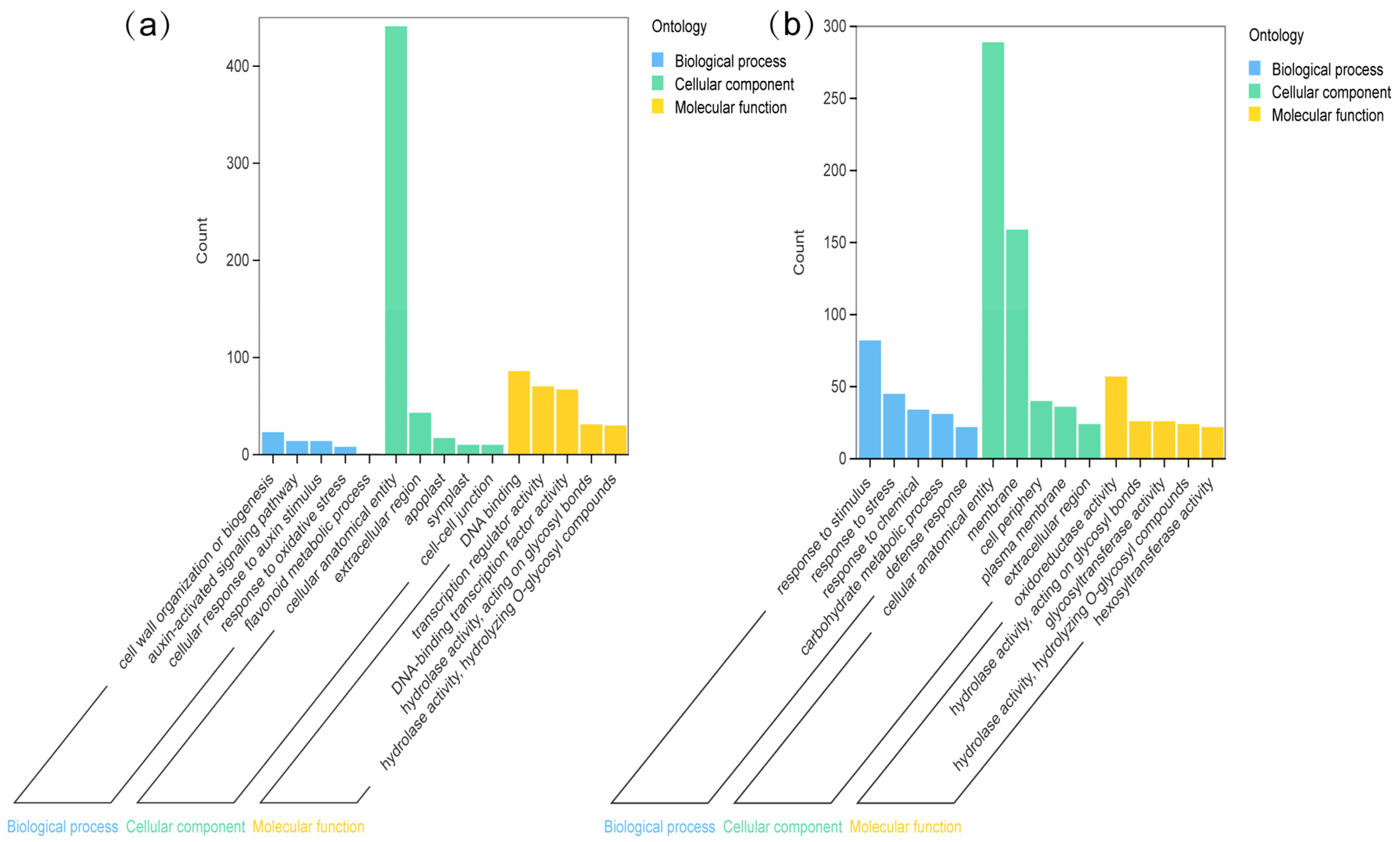

2.4. GO Enrichment Analysis of Common DEGs

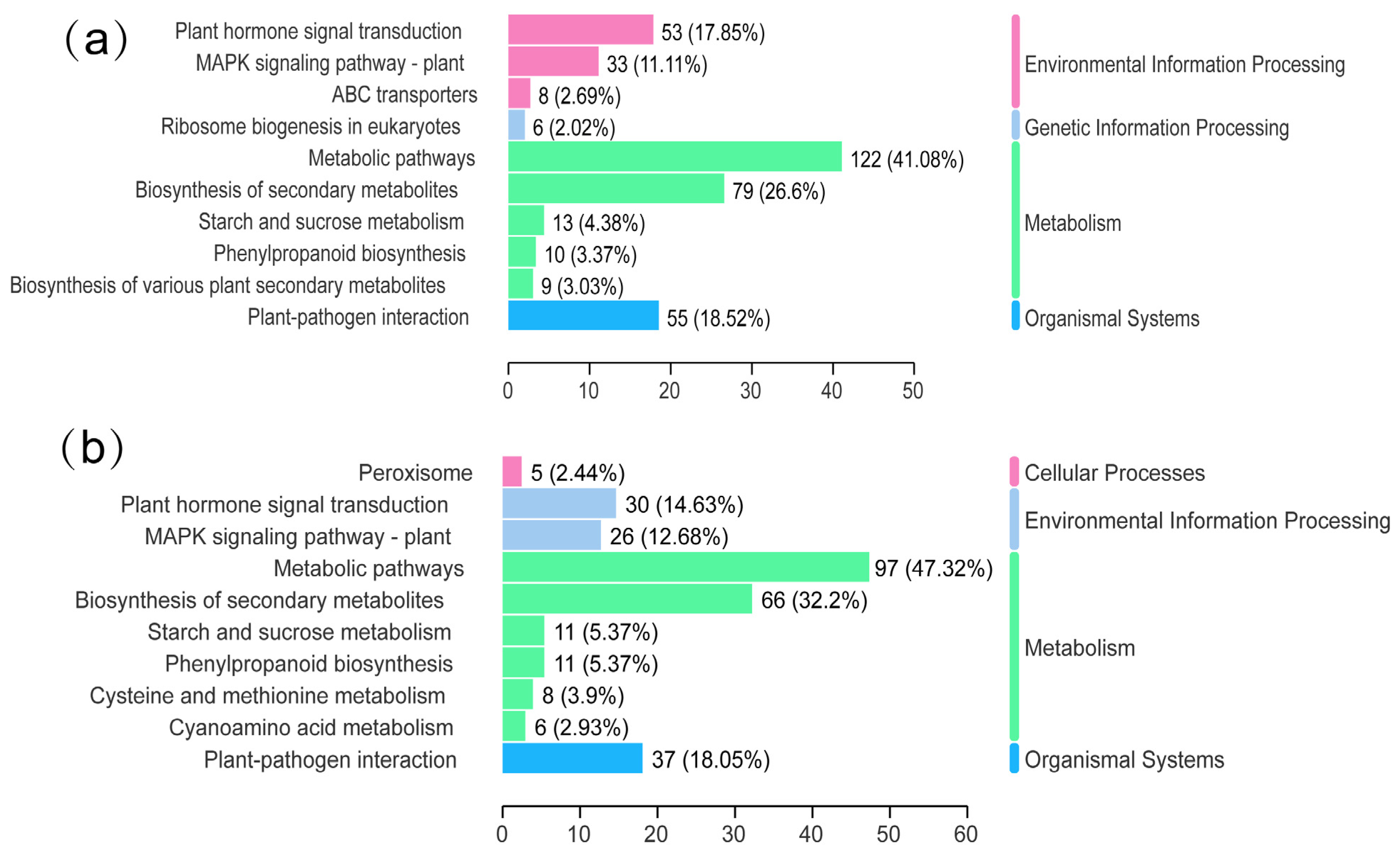

2.5. KEGG Pathway Enrichment Analysis of Common DEGs

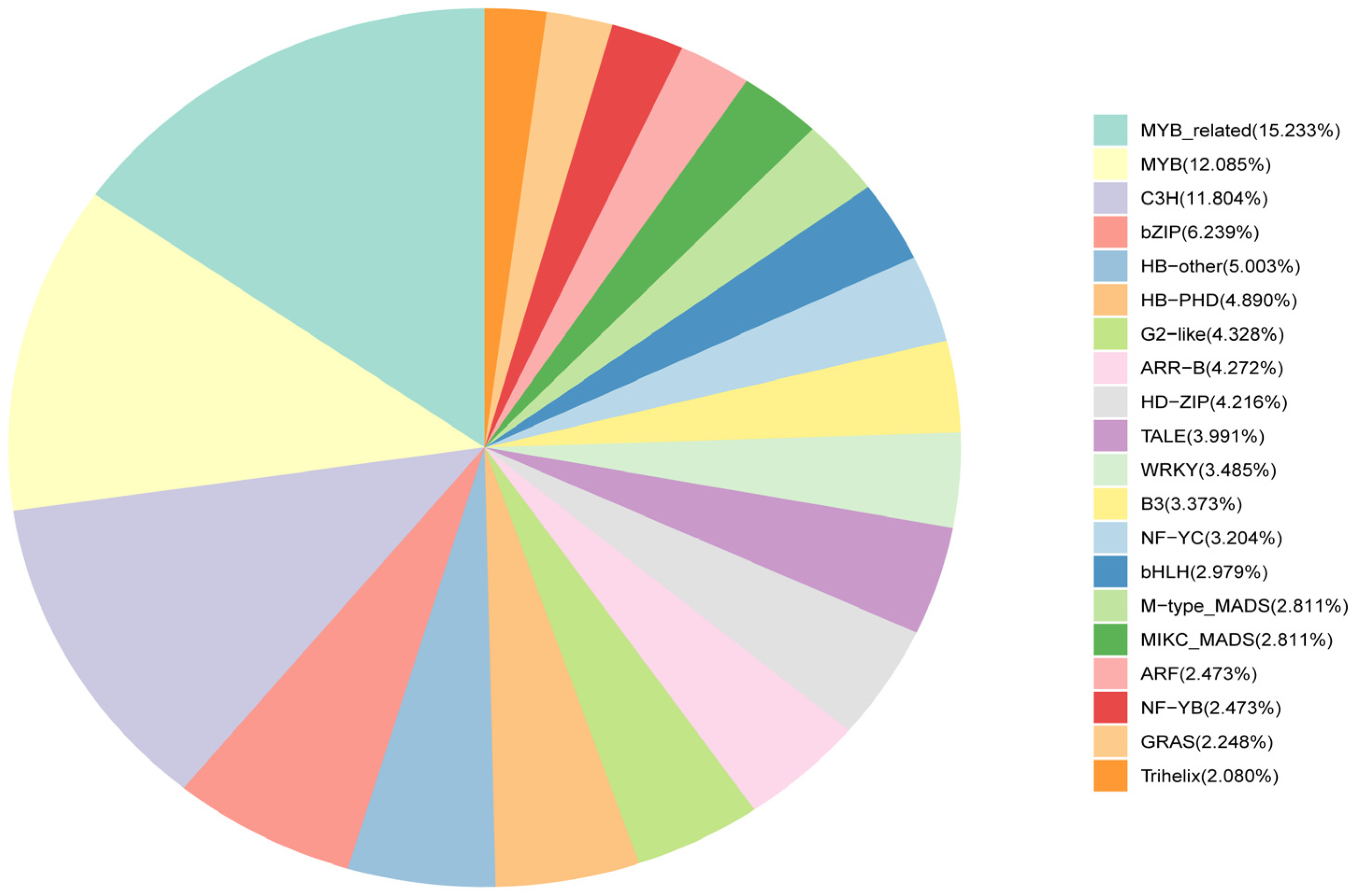

2.6. Transcription Factor Profiling Associated with Anthocyanin Degradation

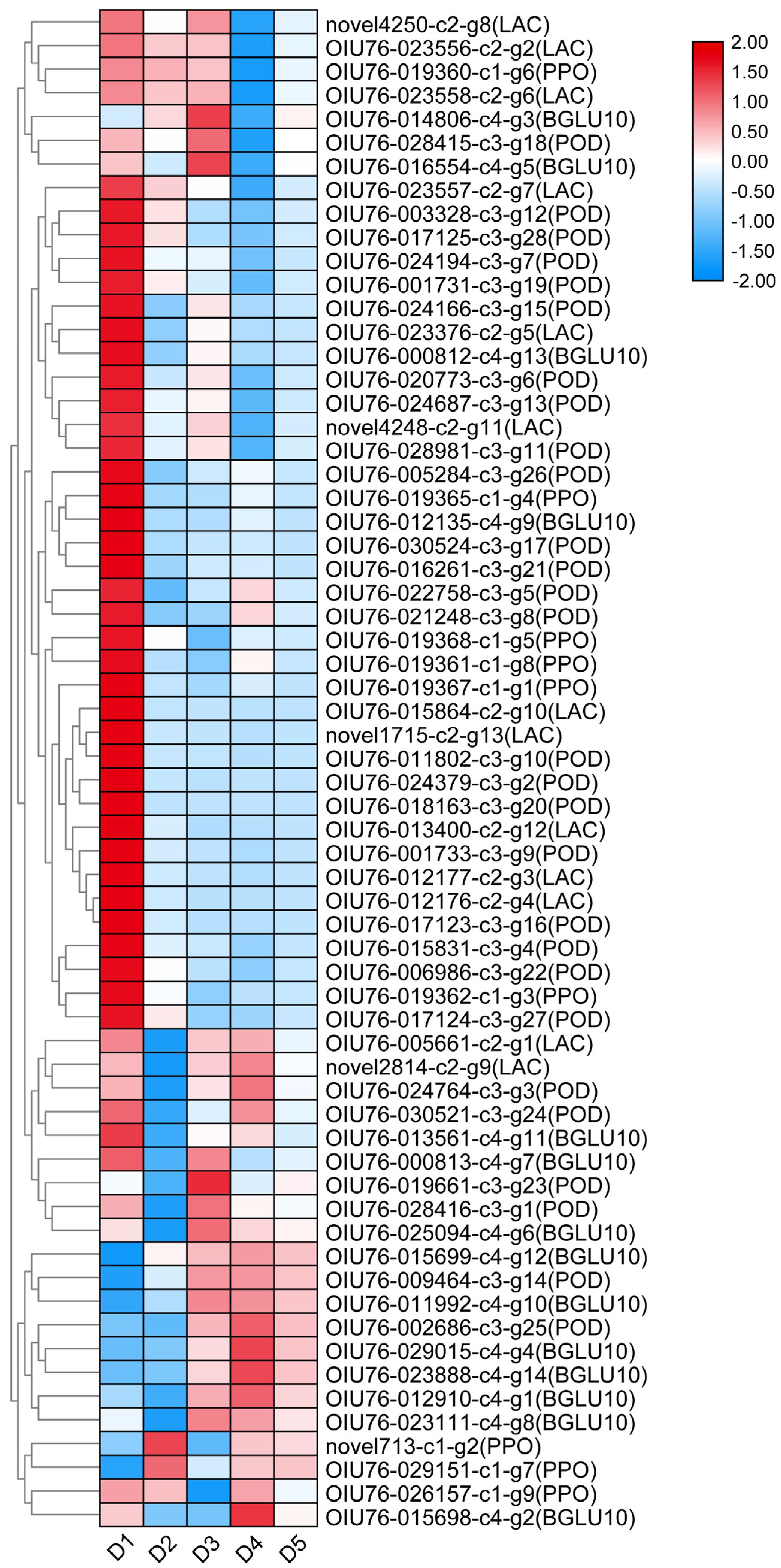

2.7. Identification of Candidate Genes Involved in Anthocyanin Degradation

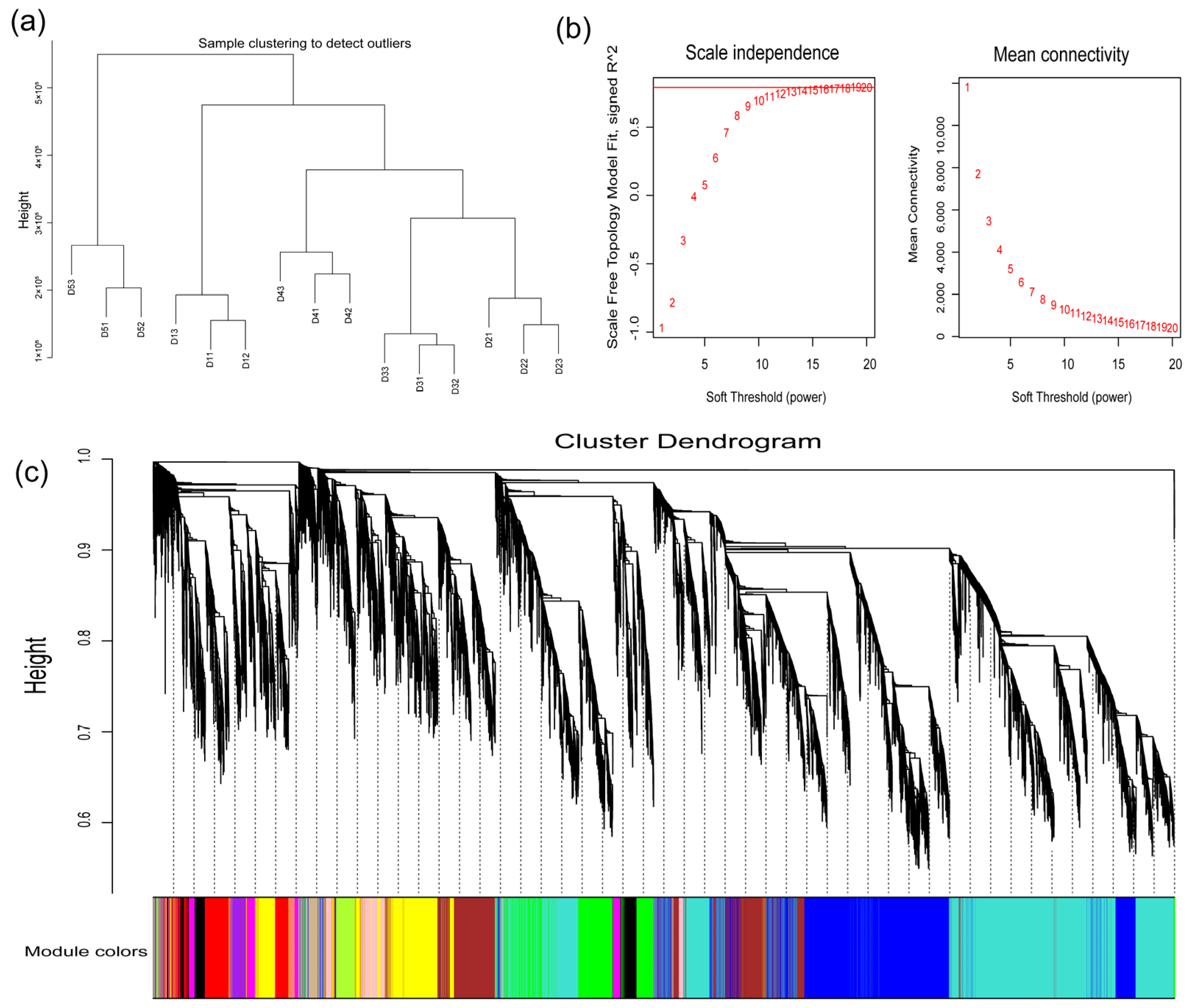

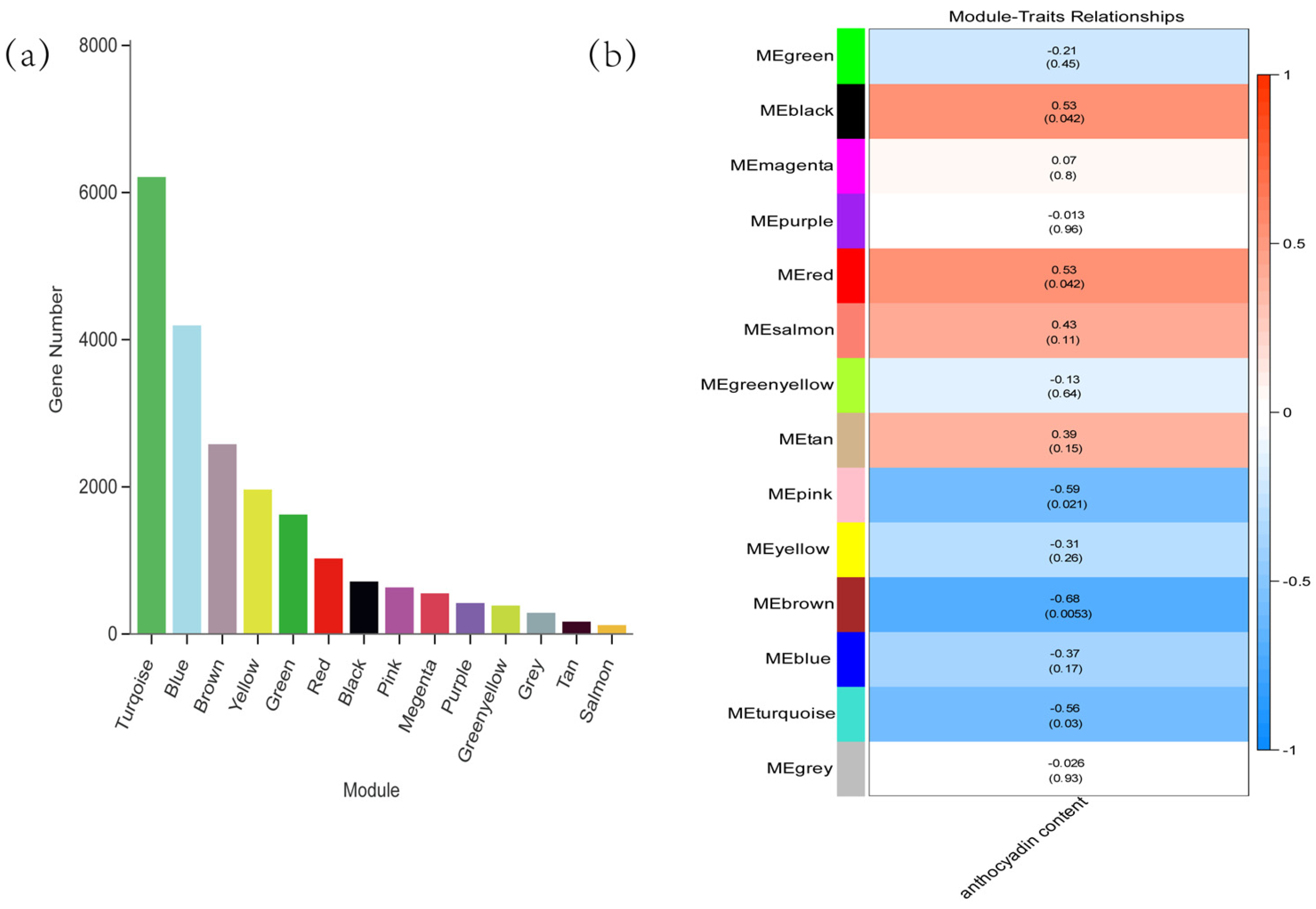

2.8. Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis (WGCNA)

2.9. Transcription Factor–Enzyme Co-Expression and Integrated Regulatory Framework of Anthocyanin Degradation

3. Discussion

3.1. Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Anthocyanins in Bark and Ecological Implications

3.2. Candidate Enzyme Genes as Central Mediators of Anthocyanin Degradation

3.3. Functional Enrichment Reveals Multi-Layered Metabolic Regulation

3.4. Transcription Factors and Co-Expression Networks in Regulatory Control

3.5. Limitations and Future Perspectives

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials, Experimental Site, and Climate Background

4.2. Sampling Design and Sample Preparation

4.3. Anthocyanin Quantification

4.4. RNA Extraction and Transcriptome Sequencing

4.5. Transcriptome Data Processing and Co-Expression Network Analysis

4.6. Transcription Factor Annotation and Co-Expression Analysis

4.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, L.; Wang, X. A Comprehensive Review of Phenolic Compounds in Horticultural Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, L.; Chen, J.; Bao, X.; Zhang, D.; Liu, J.; Wang, W.; Wei, Y.; Zong, C. Environmental and Phytohormonal Factors Regulating Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in Fruits. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Câmara, J.S.; Locatelli, M.; Pereira, J.A.M.; Oliveira, H.; Arlorio, M.; Fernandes, I.; Perestrelo, R.; Freitas, V.; Bordiga, M. Behind the Scenes of Anthocyanins—From the Health Benefits to Potential Applications in Food, Pharmaceutical and Cosmetic Fields. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheaib, A.; Mahmoud, L.M.; Vincent, C.; Killiny, N.; Dutt, M. Influence of Anthocyanin Expression on the Performance of Photosynthesis in Sweet Orange, Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck. Plants 2023, 12, 3965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashikhmin, A.; Bolshakov, M.; Pashkovskiy, P.; Vereshchagin, M.; Khudyakova, A.; Shirshikova, G.; Kozhevnikova, A.; Kosobryukhov, A.; Kreslavski, V.; Kuznetsov, V.; et al. The Adaptive Role of Carotenoids and Anthocyanins in Solanum lycopersicum Pigment Mutants under High Irradiance. Cells 2023, 12, 2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammed, H.A.; Khan, R.A. Anthocyanins: Traditional Uses, Structural and Functional Variations, Approaches to Increase Yields and Products’ Quality, Hepatoprotection, Liver Longevity, and Commercial Products. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabravolski, S.A.; Isayenkov, S.V. The Role of Anthocyanins in Plant Tolerance to Drought and Salt Stresses. Plants 2023, 12, 2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Wang, K.; Tang, R.; Liu, J.; Cheng, K.; Gao, G.; Wang, Y.; Qin, G. Recent advances in biosynthesis and regulation of strawberry anthocyanins. Hortic. Res. 2025, 12, uhaf135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Xiang, F.; Zhang, S.; Song, J.; Li, X.; Song, L.; Zhai, R.; Yang, C.; Wang, Z.; Ma, F.; et al. PbLAC4-like, activated by PbMYB26, related to the degradation of anthocyanin during color fading in pear. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Han, T.; Lyu, L.; Li, W.; Wu, W. Research progress in understanding the biosynthesis and regulation of plant anthocyanins. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 321, 112374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.W.; Wang, C.K.; Huang, X.Y.; Hu, D.G. Anthocyanin stability and degradation in plants. Plant Signal. Behav. 2021, 16, 1987767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, T.; Wang, M.; Ren, H.; Xiong, Q.; Xu, J.; Yang, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, W. Comprehensive analysis of the physiological, metabolome, and transcriptome provided insights into anthocyanin biosynthesis and degradation of Malus crabapple. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 223, 109821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, H.; Thuy, N. Kinetic study on peroxidase inactivation and anthocyanin degradation of black cherry tomatoes (Solanum lycopersicum cv. OG) during blanching. Herba Pol. 2021, 67, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, J.; Araghi, L.R.; Singh, R.; Adhikari, K.; Patil, B.S. Continuous-Flow High-Pressure Homogenization of Blueberry Juice Enhances Anthocyanin and Ascorbic Acid Stability during Cold Storage. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 11629–11639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achim, F.; Dinca, L.; Chira, D.; Raducu, R.; Chirca, A.; Murariu, G. Sustainable Management of Willow Forest Landscapes: A Review of Ecosystem Functions and Conservation Strategies. Land 2025, 14, 1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y.; Huang, R.; Xu, M.; Xu, L.A. Transcriptome-Wide Identification and Response Pattern Analysis of the Salix integra NAC Transcription Factor in Response to Pb Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, M.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, H.; Li, H.; Niu, X.; Zhou, Z.; Hou, X.; Zhu, J. Metabolome combined with transcriptome profiling reveals the dynamic changes in flavonoids in red and green leaves of Populus × euramericana ‘Zhonghuahongye’. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1274700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Wang, S.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, X.; Ji, X.; Yun, C.; Wu, S.; Takayoshi, K.; Wang, W.; Wang, H. Plant species richness regulated by geographical variation down-regulates triterpenoid compounds production and antioxidant activities in white birch bark. Flora 2023, 305, 152343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almuktar, S.A.A.A.N.; Abed, S.N.; Scholz, M. Biomass Production and Metal Remediation by Salix alba L. and Salix viminalis L. Irrigated with Greywater Treated by Floating Wetlands. Environments 2024, 11, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajraktari, D.; Bauer, B.; Zeneli, L. Antioxidant Capacity of Salix alba (Fam. Salicaceae) and Influence of Heavy Metal Accumulation. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piątczak, E.; Dybowska, M.; Płuciennik, E.; Kośla, K.; Kolniak-Ostek, J.; Kalinowska-Lis, U. Identification and accumulation of phenolic compounds in the leaves and bark of Salix alba (L.) and their biological potential. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Guo, J.; Chen, Q.; Wang, B.; He, X.; Zhuge, Q.; Wang, P. Different color regulation mechanism in willow barks determined using integrated metabolomics and transcriptomics analyses. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Jacquier, J.-C.; Harbourne, N. Preparation of Polyphenol-Rich Herbal Beverages from White Willow (Salix alba) Bark with Potential Alzheimer’s Disease Inhibitory Activity In Silico. Beverages 2024, 10, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, R.N.U.; You, Y.; Zhang, L.; Goudia, B.D.; Khan, A.R.; Li, P.; Ma, F. High Temperature Induced Anthocyanin Inhibition and Active Degradation in Malus profusion. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumaker, B.; Mortensen, L.; Klein, R.R.; Mandal, S.; Dykes, L.; Gladman, N.; Rooney, W.L.; Burson, B.; Klein, P.E. UV-induced reactive oxygen species and transcriptional control of 3-deoxyanthocyanidin biosynthesis in black sorghum pericarp. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1451215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enaru, B.; Drețcanu, G.; Pop, T.D.; Stǎnilǎ, A.; Diaconeasa, Z. Anthocyanins: Factors Affecting Their Stability and Degradation. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langfelder, P.; Horvath, S. WGCNA: An R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinform. 2008, 9, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.P.; Wang, X.F.; Zhang, X.W.; Xu, H.F.; Bi, S.Q.; You, C.X.; Hao, Y.J. An apple MYB transcription factor regulates cold tolerance and anthocyanin accumulation and undergoes MIEL1-mediated degradation. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 337–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, H.; Gao, F.; Linying, L.; He, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, M.; Wei, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Q.; et al. WRKY33 negatively regulates anthocyanin biosynthesis and cooperates with PHR1 to mediate acclimation to phosphate starvation. Plant Commun. 2024, 5, 100821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Tikunov, Y.; Schouten, R.E.; Marcelis, L.F.M.; Visser, R.G.F.; Bovy, A. Anthocyanin Biosynthesis and Degradation Mechanisms in Solanaceous Vegetables: A Review. Front. Chem. 2018, 6, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhai, J.; Shao, L.; Lin, W.; Peng, C. Accumulation of Anthocyanins: An Adaptation Strategy of Mikania micrantha to Low Temperature in Winter. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ahammed, G.J. Plant stress response and adaptation via anthocyanins: A review. Plant Stress 2023, 10, 100230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Ren, Y.; Zhao, W.; Li, R.; Zhang, L. Low Temperature Promotes Anthocyanin Biosynthesis and Related Gene Expression in the Seedlings of Purple Head Chinese Cabbage (Brassica rapa L.). Genes 2020, 11, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.; Blum, J.A.; Ma, F.; Wang, Y.; Borejsza-Wysocka, E.; Ma, F.; Cheng, L.; Li, P. Anthocyanin Accumulation Provides Protection against High Light Stress While Reducing Photosynthesis in Apple Leaves. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, N.M.; Neufeld, H.S.; Burkey, K.O. Functional role of anthocyanins in high-light winter leaves of the evergreen herb Galax urceolata. New Phytol. 2005, 168, 575–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, D.; Qiu, S.; Gong, Z.; Shen, H. Effects of environmental factors on seedling growth and anthocyanin content in Betula ‘Royal Frost’ leaves. J. For. Res. 2017, 28, 1147–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Yang, H.; Ji, S.; Tian, C.; Chen, N.; Gong, H.; Li, J. Metabolome and Transcriptome Analyses of Anthocyanin Accumulation Mechanisms Reveal Metabolite Variations and Key Candidate Genes Involved in the Pigmentation of Prunus tomentosa Thunb. Cherry Fruit. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 938908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, F.; Zhang, X.L.; Luo, H.H.; Zhou, J.J.; Gong, Y.H.; Li, W.J.; Shi, Z.W.; He, Q.; Wu, Q.; Li, L.; et al. An Intracellular Laccase Is Responsible for Epicatechin-Mediated Anthocyanin Degradation in Litchi Fruit Pericarp. Plant Physiol. 2015, 169, 2391–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Pang, X.; Xuewu, D.; Ji, Z.; Jiang, Y. Role of peroxidase in anthocyanin degradation in litchi fruit pericarp. Food Chem. 2005, 90, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, K.; Li, X.; Zeng, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhu, Y.; Hu, J.; Sun, J.; Bai, W. Chemical stability of carboxylpyranocyanidin-3-O-glucoside under β-glucosidase treatment and description of their interaction. Food Chem. 2024, 447, 138840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallis, M.J.; Lin, Y.; Rogers, A.; Zhang, J.; Street, N.R.; Miglietta, F.; Karnosky, D.F.; De Angelis, P.; Calfapietra, C.; Taylor, G. The transcriptome of Populus in elevated CO2 reveals increased anthocyanin biosynthesis during delayed autumnal senescence. New Phytol. 2010, 186, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Ren, Y.; Liu, Y.; Sun, F.; Abozeid, A.; Tang, Z.; Mu, L. Comparison of Seasonally Adaptive Metabolic Response Strategies of Two Acer Species. Forests 2022, 13, 2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maritim, T.K.; Masand, M.; Seth, R.; Sharma, R.K. Transcriptional analysis reveals key insights into seasonal induced anthocyanin degradation and leaf color transition in purple tea (Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze). Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoclanclounon, Y.A.B.; Rostás, M.; Chung, N.J.; Mo, Y.; Karlovsky, P.; Dossa, K. Characterization of Peroxidase and Laccase Gene Families and In Silico Identification of Potential Genes Involved in Upstream Steps of Lignan Formation in Sesame. Life 2022, 12, 1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Lin, B.; Hao, P.; Yi, K.; Li, X.; Hua, S. Multi-Omics Analysis Reveals That Anthocyanin Degradation and Phytohormone Changes Regulate Red Color Fading in Rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) Petals. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Sun, Y.; Li, J.; Zhou, Z.; Deng, X.; Wang, Z.; Wu, S.; Lin, L.; Huang, Y.; Zeng, W.; et al. High Light Intensity Triggered Abscisic Acid Biosynthesis Mediates Anthocyanin Accumulation in Young Leaves of Tea Plant (Camellia sinensis). Antioxidants 2023, 12, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Li, Y.; Du, T.; Kang, L.; Pei, B.; Zhuang, W.; Tang, F. Transcriptome sequencing and anthocyanin metabolite analysis involved in leaf red color formation of Cinnamomum camphora. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 31470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgedaitė-Šėžienė, V.; Čėsnienė, I.; Vaitiekūnaitė, D. Temporal Variations in Enzymatic and Non-Enzymatic Antioxidant Activity in Silver Birch (Betula pendula Roth.): The Genetic Component. Forests 2024, 15, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yang, N.; Zhang, Q.; Pei, Z.; Chang, M.; Zhou, H.; Ge, Y.; Yang, Q.; Li, G. Anthocyanin Biosynthesis Associated with Natural Variation in Autumn Leaf Coloration in Quercus aliena Accessions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Z.; Huang, Y.; Ni, J.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Q. For a Colorful Life: Recent Advances in Anthocyanin Biosynthesis during Leaf Senescence. Biology 2024, 13, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fermaniuk, C.; Fleurial, K.G.; Wiley, E.; Landhäusser, S.M. Large seasonal fluctuations in whole-tree carbohydrate reserves: Is storage more dynamic in boreal ecosystems? Ann. Bot. 2021, 128, 943–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, D.R.; Schädel, C.; Smith, K.R.; Richardson, A.D.; Bahn, M.; Arain, M.A.; Varlagin, A.; Ouimette, A.P.; Frank, J.M.; Barr, A.G.; et al. Phenology of Photosynthesis in Winter-Dormant Temperate and Boreal Forests: Long-Term Observations From Flux Towers and Quantitative Evaluation of Phenology Models. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2024, 129, e2023JG007839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, T.P.; Malladi, A.; Nambeesan, S.U. Sustained carbon import supports sugar accumulation and anthocyanin biosynthesis during fruit development and ripening in blueberry (Vaccinium ashei). Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 24964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Huang, H.; Tan, C.; Gao, L.; Wan, S.; Zhu, B.; Chen, D.; Zhu, B. Transcriptome and WGCNA Analyses Reveal Key Genes Regulating Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in Purple Sprout of Pak Choi (Brassica rapa L. ssp. chinensis). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broucke, E.; Dang, T.T.V.; Li, Y.; Hulsmans, S.; Van Leene, J.; De Jaeger, G.; Hwang, I.; Wim, V.d.E.; Rolland, F. SnRK1 inhibits anthocyanin biosynthesis through both transcriptional regulation and direct phosphorylation and dissociation of the MYB/bHLH/TTG1 MBW complex. Plant J. 2023, 115, 1193–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cappellini, F.; Marinelli, A.; Toccaceli, M.; Tonelli, C.; Petroni, K. Anthocyanins: From Mechanisms of Regulation in Plants to Health Benefits in Foods. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 748049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, C.; Jiang, C.; Lin, H.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, Y. VvWRKY5 positively regulates wounding-induced anthocyanin accumulation in grape by interplaying with VvMYBA1 and promoting jasmonic acid biosynthesis. Hortic. Res. 2024, 11, uhae083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gai, S.; Du, B.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Turupu, M.; Yao, Q.; Wang, X.; Yan, Y.; Li, T. bZIP Transcription Factor PavbZIP6 Regulates Anthocyanin Accumulation by Increasing Abscisic Acid in Sweet Cherry. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, H. Expression Pattern Analysis of Larch WRKY in Response to Abiotic Stress. Forests 2022, 13, 2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levée, V.; Major, I.; Levasseur, C.; Tremblay, L.; MacKay, J.; Séguin, A. Expression profiling and functional analysis of Populus WRKY23 reveals a regulatory role in defense. New Phytol. 2009, 184, 48–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, P.; Chen, M.; Chen, L.; Yang, Y.; Ma, L.; Bi, P.; Tang, S.; Luo, Q.; Chen, J.; Chen, H.; et al. Deciphering the Anthocyanin Metabolism Gene Network in tea plant(Camellia sinensis) through Structural Equation modeling. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, G.; Ren, Y.; Kang, J.; Wang, B.; Zhang, J.; Fang, J.; Wu, W. Integrative analysis of grapevine (Vitis vinifera L) transcriptome reveals regulatory network for Chardonnay quality formation. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1187842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Li, J.; Wang, D.; Wang, H.-C.; Yonghua, Q.; Hu, G.; Zhao, J. Transcriptome profiling of Litchi chinensis pericarp in response to exogenous cytokinins and abscisic acid. Plant Growth Regul. 2018, 84, 437–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giusti, M.M.; Wrolstad, R.E. Characterization and Measurement of Anthocyanins by UV-Visible Spectroscopy. Curr. Protoc. Food Anal. Chem. 2001, 1, F1.2.1–F1.2.13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Raw Reads | Clean Reads | Q20_Rate | Q30_Rate | GC_Content |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1-1 | 43,335,042 | 43,335,026 | 98.10% | 94.82% | 44.68% |

| D1-2 | 43,340,716 | 43,340,702 | 98.39% | 95.60% | 44.79% |

| D1-3 | 43,344,920 | 43,344,894 | 97.43% | 93.09% | 44.84% |

| D2-1 | 43,359,260 | 43,359,236 | 97.87% | 94.27% | 45.33% |

| D2-2 | 43,383,632 | 43,383,614 | 97.99% | 94.51% | 44.98% |

| D2-3 | 40,257,396 | 40,257,384 | 97.65% | 93.60% | 45.22% |

| D3-1 | 43,372,770 | 43,372,736 | 97.47% | 93.14% | 44.59% |

| D3-2 | 43,334,934 | 43,334,914 | 97.47% | 93.20% | 44.58% |

| D3-3 | 42,901,164 | 42,901,140 | 97.55% | 93.37% | 44.63% |

| D4-1 | 43,376,796 | 43,376,776 | 98.16% | 95.00% | 44.50% |

| D4-2 | 43,375,470 | 43,375,456 | 98.09% | 94.74% | 43.93% |

| D4-3 | 43,398,338 | 43,398,322 | 98.20% | 95.06% | 44.65% |

| D5-1 | 43,334,392 | 43,334,348 | 97.95% | 94.46% | 44.44% |

| D5-2 | 43,351,042 | 43,350,978 | 97.15% | 92.67% | 43.94% |

| D5-3 | 43,351,570 | 43,351,560 | 97.90% | 94.21% | 44.00% |

| Stage | Month | Temperature (°C) | Precipitation (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| D1 | Nov 2024 | 7.61 | 20.4 |

| D2 | Dec 2024 | −0.45 | 1.6 |

| D3 | Jan 2024 | −1.74 | 5.0 |

| D4 | Feb 2025 | −0.60 | 0.6 |

| D5 | Mar 2025 | 7.78 | 4.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, H.-Y.; Liu, X.-J.; Yin, M.-Z.; Cui, S.-J.; Liang, H.-Y.; Xu, Z.-H. Transcriptomic Analysis of Anthocyanin Degradation in Salix alba Bark: Insights into Seasonal Adaptation and Forestry Applications. Forests 2025, 16, 1598. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16101598

Wang H-Y, Liu X-J, Yin M-Z, Cui S-J, Liang H-Y, Xu Z-H. Transcriptomic Analysis of Anthocyanin Degradation in Salix alba Bark: Insights into Seasonal Adaptation and Forestry Applications. Forests. 2025; 16(10):1598. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16101598

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Hong-Yong, Xing-Ju Liu, Meng-Zhen Yin, Sheng-Jia Cui, Hai-Yong Liang, and Zhen-Hua Xu. 2025. "Transcriptomic Analysis of Anthocyanin Degradation in Salix alba Bark: Insights into Seasonal Adaptation and Forestry Applications" Forests 16, no. 10: 1598. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16101598

APA StyleWang, H.-Y., Liu, X.-J., Yin, M.-Z., Cui, S.-J., Liang, H.-Y., & Xu, Z.-H. (2025). Transcriptomic Analysis of Anthocyanin Degradation in Salix alba Bark: Insights into Seasonal Adaptation and Forestry Applications. Forests, 16(10), 1598. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16101598