Abstract

Recently, the concept of participatory democracy developed in the early 1970s has come back into fashion to revitalize the public involvement in political decision-making processes. Public participation in forest policy has been fully conceptualized by the scientific community in the late 1990s and early 2000s, but in many contexts, the practical application remains unfulfilled. The aim of this study is to identify and analyse the participatory techniques used in the literature to increase knowledge and facilitate its transferability into forest policies and strategies. A literature review was carried out to offer an overview of the participatory techniques adopted in the decision-making process. At the end of the literature review, 24 participatory techniques were identified based on over 2000 publications. Afterwards, the participatory techniques were assessed using seven indicators (degree of participation, type and number of participants, type of selection, time scale, cost, and potential influence on policy). The results showed that the type of actors involved in the participatory technique is a key variable for the complexity and usefulness of the process, while the number of participants influences how information is disseminated. The Correspondence Analysis highlighted that the participatory techniques can be divided into four groups: the first group includes those techniques with a high degree of participation (i.e., collaborate) and a contextual high potential influence on policies (e.g., citizens’ juries and wisdom council); the second one includes techniques with a low degree of participation (inform) and influence on policies (e.g., social media, adverting, surveys, and polls); while the third and fourth groups consist of those with a medium–high degree of participation (consult or involve), but a variable type of selection and number of participants, and consequently of time and costs.

1. Introduction

In the early 1970s, the concept of participatory democracy spread in the Western world as an alternative to representative (or elitist) democracy in order to involve citizens in the political decision-making process [1]. Participatory democracy can be defined as a form of representative democracy, wherein citizens are actively participating in decision-making processes to define the agenda-setting together with policy makers [2]. The conceptualization of the participatory democracy has identified citizens as key actors in the political process and participation as modus operandi [3]. However, participatory democracy has often been implemented through a top-down approach to include citizen input into policy decisions from a practical point of view [4]. This approach allows policy makers to decide the level of involvement of citizens and other stakeholders controlling the decision-making process. Alternatively, self-mobilization through social movements or citizens’ committees follows a bottom-up approach closer to the ideal of participatory democracy in which power is in the hands of citizens [5]. Between these two extremes, different forms and levels of citizen involvement in political decision-making processes have emerged in the international literature from the 1970s of the last century to today. The first publication on participatory democracy in the forest sector—published in 1990—discussed the reasons behind participatory democracy and outlines the criteria for evaluating public participation in forest management in United States [6]. Afterwards, a proper line of research was developed on public participation in forest planning, management, and policy to define the key principles to support policy makers [7,8,9,10]. In the forest sector, the first impulse to public participation in decision-making processes occurred in many National Forest Programmes (NFPs) thanks to the principles established during the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) held in Rio de Janeiro in 1992 [11,12]. The UNCED encouraged a broad-based bottom-up approach in the management of natural resources, thus placing public participation fully on the global political agenda [13]. In this sense, the Intergovernmental Panel on Forests (IPF), taking up the UNCED principles, recommended to develop NFPs through a participatory process [14]. From the late 1990s to the early 2000s, many NFPs have been developed based on key principles such as partnership and participatory mechanisms to involve interested parties; the empowerment of regional and local government structures; and recognition and respect for customary and traditional rights of indigenous people and local communities [15,16]. These key principles refer to those of participatory democracy applied to the forestry sector. Similarly, the Ministerial Conferences on Protection of Forests in Europe (MCPFE) asserted that… “develop the conditions for the participation of relevant stakeholders in the development of forest policies and programmes” (Lisbon Resolution L1, MCPFE 1998) [17]. Additionally, in 1998, the first EU Forest Strategy stressed the importance of an active participation in all forest-related international processes and the need to improve coordination, communication and cooperation in all policy areas of relevance to the forest sector [18]. Recently, the new EU Forest Strategy for 2030 encouraged forest and forestry stakeholders to establish a skills partnership under the Pact for Skills to work together to increase the number of upskilling and reskilling opportunities in forestry [19]. The Pact for Skills is aimed to mobilize and incentivize private and public stakeholders to take concrete actions such as education and training for foresters to the challenges and needs of today’s realities [20]. Since 2020, the concept of public participation in forest discourse has slowed down due to the difficulty in translating theoretical principles of participation into practice. The reduction of public participation in political decision-making processes has occurred in all areas, including, as mentioned, forest discourse. Therefore, currently, it is important to rethink public participation in decision-making processes to ensure that citizens are transformed from passive citizens to responsible and expert citizens [21]. As emphasized by Tikkanen (2018) [22], forest discourse is in the era of participatory downturn; therefore, it is fundamental to “find new solutions” oriented towards innovations and creative thinking about the future. Starting from these considerations, the concept of public participation in the forest sector must be rethought and revitalized to keep up with the times. The aim of the present study is to identify and analyse the participatory techniques of involving citizens and stakeholders in decision-making processes used in political, social, planning, and environmental sciences to evaluate their suitability for the forest-based sector. The participatory techniques and processes have been identified through a literature review and analysed considering a set of criteria to evaluate their applicability to the forest policies and strategies. To achieve the aforementioned objective, the research questions are the following: (R1) How can the participatory techniques used in participatory democracy be applied to forest policies and strategies? (R2) What participatory techniques can be efficiently adopted to implement forest policies and strategies at different levels (national, regional, and local)?

2. Materials and Methods

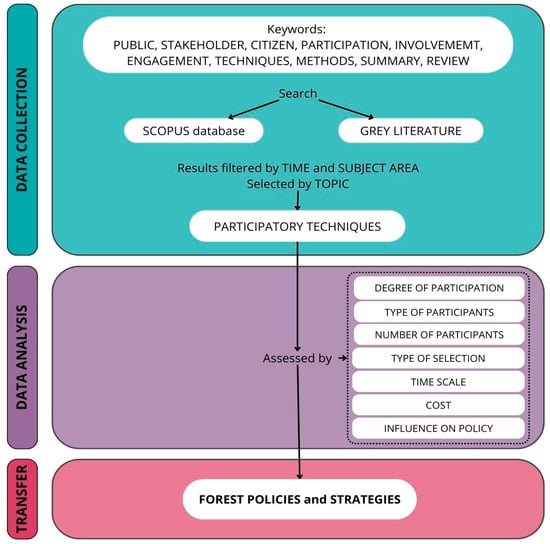

The study was structured in three steps in order to identify and analyse the participatory techniques used in different disciplinary sectors and evaluate their suitability in the forest-related decision-making process. The structure of the study is described in Scheme 1.

Scheme 1.

Framework of the three literature review steps.

2.1. Data Collection

A literature review was carried out to offer an overview of the participatory processes used to involve citizens and/or stakeholders in the decision-making process across different scientific fields. The review was designed following the guidelines proposed by the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis) protocol [23]. First of all, the peer-reviewed publications were retrieved from Scopus database (https://www.scopus.com, accessed on 30 April 2024) using the following search query:

(“PUBLIC” OR “STAKEHOLDER*” OR “CITIZEN*”) AND (“PARTICIPATION” OR “INVOLVEMENT” OR “ENGAGEMENT”) AND (“TECHNIQUE*” OR “METHOD*”) AND (“SUMMARY” OR “REVIEW*”).

The search, conducted without setting a timeframe, returned a total of 11,791 documents. Afterwards, further filtering was applied based on the timeframe (from 2000 to 2024 to consider the most recent publications) and subject area (restricted to “Environmental Science”, “Business, Management and Accounting”, “Multidisciplinary”, and “Economics, Econometrics and Finance”, to ensure relevance to the contexts being analysed). This refinement reduced the number of documents to 2275. In addition, 20 documents from other sources—e.g., Ph.D. and Master theses, manuals, and guides—were included to consider also technical reports and informative publications. Therefore, a total of 2295 documents were considered and analysed in this literature review.

2.2. Data Analysis

The participatory techniques identified through the literature review were assessed by considering seven individual criteria [24,25,26,27]: degree of participation, type of participants, number of participants, selection of participants, time scale, cost, and potential influence on final policy (described below). All these criteria were successively used to evaluate the participatory techniques through the Correspondence Analysis (CA) method. The CA method is an analysis procedure for nominal categorical data that allows researchers to study the association between two or more variables, synthesizing the set of data (e.g., participation indicators) in a two-dimensional graphical form [28].

In this study, the CA method was applied by considering the following variables and the related attributions: degree of participation (from inform to empower); number of participants (less than 25 people, between 25 and 10, and more than 100); time scale (includes a duration from minutes to days and periodicity); type of participants (citizens, stakeholders, and experts, but more than one category can be involved, depending on the context); type of selection (no selection, self-selection, or random or targeted selection; also in this case, the type of selection applied may include more than one); cost (from low to high); and influence on policy (from low to high).

For the analysis, the complete disjunctive matrix was subjected to the CA algorithm; all statistical tests were performed using the XLStat 2020 software.

2.3. Criteria to Assess Participatory Techniques

2.3.1. Degree of Participation

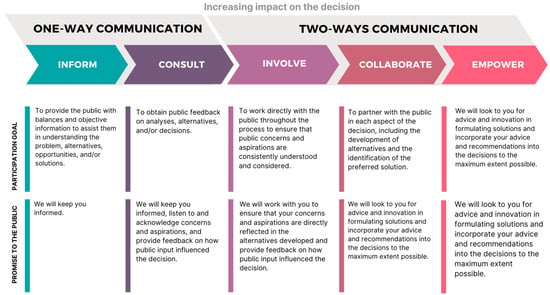

To classify participatory techniques based on the level of citizen involvement, the model developed in [24] by Arnstein (1969) has been used as subsequently simplified by the International Association for Public Participation (Figure 1). Therefore, the following five degrees of participation were considered in this study [29]:

Figure 1.

Spectrum of public participation, revised by the International Association for Public Participation (https://www.iap2.org/, accessed on 9 May 2024) [29].

- Informing—providing balanced and objective information about new programs or services, and about the reasons for choosing them; providing updates during implementation;

- Consulting—inviting feedback and suggestions on alternatives, analyses, and decisions related to new programs or services; possibly adjusting and decisions according to their feedback;

- Involving—working directly with the public throughout the process to ensure that public concerns and aspirations are consistently understood and considered; letting people know how their involvement has influenced decisions;

- Collaborating—enabling community members to participate in every aspect of planning and decision making for new programs or services, which means sharing responsibilities with citizens, working together, and making decisions collaboratively;

- Empowering—delegating of decision-making and giving the full managerial power over project development and implementation to the stakeholders/public.

The five degrees of participation of the International Association for Public Participation were considered in this study rather than a continuum of degrees of participation in order to better distinguish and analyse the identified participatory technologies.

2.3.2. Type of Participants

This indicator refers to the nature of individuals engaged in the participatory process, differentiating between the types of participants and the staff members who enable the process to occur [30]. There are several main categories of actors that can be included in the process, as follows [26,27]:

- Citizens—members of the community or public directly impacted by the decisions or issues being addressed. Their involvement can range from providing input and feedback to actively co-designing solutions.

- Stakeholders—individuals or groups who have an interest, involvement, or “stake” in a particular project, organization, or issue. Stakeholders can include local businesses, advocacy groups, government agencies, and non-profit organizations [31].

- Experts—professionals or subject matter experts who contribute specialized knowledge and insights to inform decision-making [32]. Experts may provide technical guidance, analysis, or recommendations based on their expertise.

- Policy-Makers—individuals or entities responsible for making final decisions based on the inputs and recommendations gathered through the participatory process. These could include elected officials, policy-makers, or project managers [33].

- Supporting Figures—individuals who oversee and guide the participatory process to ensure that it runs properly and remains inclusive, transparent and productive (e.g., facilitators help manage discussions, encourage participation, and maintain a respectful environment).

The composition of participants can vary depending on the specific context and objectives of the participatory method; engaging a diverse range of participants ensures that multiple perspectives are considered.

2.3.3. Number of Participants

This criterion refers to the number of individuals who are actively involved in the participatory process. It can impact the dynamics, effectiveness, and outcomes of the participatory approach [34]. Larger groups may require more structured facilitation to ensure everyone’s voices are heard, while smaller groups may enable more intimate and in-depth conversations [27].

Processes in presence can be divided into processes for small groups (up to 25 participants), for medium-sized groups (from 25 to 100 participants), and for large groups (100 and more participants) [26]. There are also flexible types, which are suitable for groups of participants of different sizes (‘variable’), and open processes, for which there is an indication of the number of participants involved but it is not binding [35].

2.3.4. Selection of Participants

The selection of participants can be influenced by the objectives, context, and nature of the project or initiative. The process may be more or less stringent based on the number and characteristics of participants involved. The main selection methods can be summarized as follows [25]:

- Self-Selection—processes are open to all stakeholders; those who participate have decided to do so consciously and by their own choice;

- Random sampling—recruitment can achieve a broad representativeness of participants through random sampling and thus reduce the prevalence of specific interests, and one approach to ensure a better representativeness is to select a random stratified sample of the affected population [27];

- Targeted selection—this form of selection is generally open to all stakeholders; however, to achieve a higher degree of representativeness among participants, individuals or representatives from various demographic groups are specifically invited to participate based on factors such as age, gender, education, or professional criteria [36].

2.3.5. Time Scale

The duration of the method varies depending on the project’s complexity, potential deadlines, and the desired level of engagement, encompassing both the number of participants and the depth of topics explored. Certain participatory activities—e.g., interviews, focus groups, workshops, or community meetings—can be completed within a short span, ranging from a few hours to several days, while others may extend over months or even years [25].

The present study offers an attempt to provide the average time required by individual participants to take part in the single technique. Due to the absence of standardized durations, this time is often represented as a range. Additionally, since participatory methods frequently involve iterative processes evolving over time, including multiple cycles of consultation and feedback, indications are given as to whether the technique is periodic or ends in a single event.

2.3.6. Cost

The processes should be cost-effective: cost is a significant concern for those organizing a participation exercise, and achieving value for money is a key motivation. For instance, a large public hearing might not be justified for a relatively minor policy decision. Prior to conducting a participation exercise, it is prudent to assess the potential costs of alternative methods in terms of time, human resources, and money, and to evaluate how well they meet other criteria. Although monetary costs are objectively measurable, most discussions on participation methods in the literature do not delve deeply into costs [27]. Moreover, due to the wide range of ways each method can be implemented, establishing a precise classification of the “costliness” of procedures is challenging and typically results in only an estimate or deduction [37]; in this case, the classification of costs has developed for classes such as variable, low, moderate, and potentially high. These indicators were selected based on the literature, prioritizing those frequently mentioned in summary reviews and those most aligned with our objectives. In the same way, the values of the parameters/indicators were assigned to each technique mainly through the data obtained from the literature by considering the information obtained for each technique.

2.3.7. Potential Influence on Final Policy

When implemented effectively, participatory methods contribute to more informed, equitable, and sustainable policy development and implementation. It is important to evidence that one major criticism of participation methods is their perceived ineffectiveness. In fact, these methods sometimes are considered as tools used primarily to justify decisions or create the appearance of consultation without genuine intent to act on recommendations [27]. The impact of participatory techniques on final policy outcomes relies on the quality of engagement, inclusivity of participants, and the extent to which stakeholder input is integrated into decision-making processes. The degree of influence on policy is indicative because it depends on many factors (including technology). It has been classified as low, moderate, and (potentially) high [27].

2.4. Application into Forest Policies

In the last step, the diffusion of the previously identified participatory techniques in forest policies and strategies was analysed with a further literature review. The data were obtained from the Scopus database using the following queries (either by applying the processes individually or in groups): (“FOREST POLIC*” OR “FOREST STRATEG*” OR “FOREST GOVERNANC*”) AND technique name.

The data collected with this further literature review allow us to outline which participatory techniques have been used more and less in forest policies and the trend of practical applications of participatory techniques in forest sector.

3. Results

3.1. Results of the Literature Review

A total of 24 participatory techniques, along with the tools required for their implementation, were gathered from the literature review. In Table 1, the techniques are described and supported by examples of tools used for their implementation.

Table 1.

Description of the participatory techniques identified in the literature.

The participatory techniques listed cover a wide range of approaches from traditional and well-known methods (e.g., public hearings and surveys) to more innovative and lesser-known approaches (e.g., citizen juries and role-playing games). The description of each technique outlines the modalities of development and the context of the participation process. This description permits us to understand the differences, evidencing the importance of tailoring engagement strategies to specific contexts and purposes.

Observing Table 1, the possible tools useful for the application of the technique indicated are shown and emerge such that they can be applied in most cases in both physical and virtual settings. This adaptability underscores the growing importance of online platforms for public participation, especially considering recent global events.

The choice of the tool certainly has a great impact on many criteria such as costs, number of partners, and time scale. On one hand, this is an advantage in terms of the flexibility of the technique according to the available resources, but on the other hand, this flexibility makes the comparability between techniques more difficult.

3.2. Assessment of Participatory Techniques

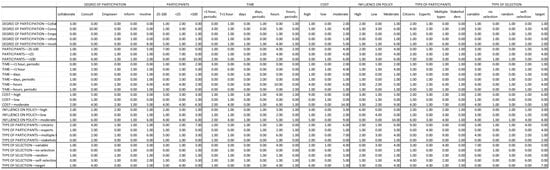

The participatory techniques are listed in Table 2 based on the degree of participation (from inform to empower) and are identified by considering the descriptive criteria.

Table 2.

Assessment of participatory techniques based on seven criteria (degree of participation, type and number of participants, selection of participants, time scale, cost, and potential influence on policy).

In several cases, different grades/intervals are reported. This variability arises from the function assigned and the process implementation (e.g., virtual or face-to-face tools) that are at the origin of the several variants found during the document analysis.

The data evidence that processes with a low degree of participation (e.g., informing) can involve many people (more than 100), usually unselected citizens, who are required to participate for a short time on average (a few minutes); this is typical of social media and advertising.

Usually, higher levels of involvement (e.g., empowering) correspond to participatory techniques involving smaller groups, often consisting mainly of selected stakeholders or experts, and the time required for participants is generally longer (hours or periodic events). In this category, it is possible to find examples such as working groups and expert panels.

Exceptions include participatory techniques like a referendum, which have a high level of participation while involving the general population and requiring little time, and interviews, which despite having a low level of participation, typically involve relatively small groups.

As noted, higher levels of involvement (i.e., empower and collaborate) have a greater influence on policy and this significant relationship is also represented by the CA method; this correlation is easily deduced but is not always verified. Advertising and the media, which have an informative purpose, can indirectly influence policies more than other processes; understanding the potential influence helps in setting realistic expectations and assessing the effectiveness of the engagement process in achieving policy objectives.

Potential stronger influences on policies usually translate into higher costs. It is important to recognize that these costs are not only monetary but also include the need for human resources and time to develop and complete the participatory techniques. In many cases, this parameter has been deduced by considering the possible variability of the tools (e.g., implementing a role in person versus online can have significant differences), the scope of the area of interest (corporate, local, or national), and the cases found during the search.

Some processes, such as role-playing games and educational events, do not follow this connection; in fact, although they have limited effects on policies, they can involve significant organizational costs. It is important to calibrate the use of resources with the purposes, especially if resources are limited.

The dataset used for the Correspondence Analysis is composed of 24 techniques and seven nominal variables, as shown in the Table 3.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics (active qualitative variables).

The total inertia, which is a function of the number of active variables and modes and is proportional to χ2 (evaluates the dispersion of the profiles), amounts to 3143; this value is explained for 28.39% by the eigenvalues F1 and F2 and for more than 57% by the eigenvalues F1, F2, F3, F4, and F5 (Table 4). The inertia explained by the first factors is not very high because of the large number of modes and, consequently, the variability present in the data matrix.

Table 4.

The eigenvalues, the percentages of variability of inertia, the percentages of adjusted inertia, and the cumulative percentage; only the most significant eigenvalues are reported.

The results of the Burt matrix show that (see Figure A1) the variable high influence on policies is related to a medium–high degree of participation (i.e., collaborate and empower), a low number of participants (less than 25), and higher timescales and costs. Conversely, the variable low influence on policies is related to a low degree of participation (i.e., consult) and moderate costs and time, but a high number of participants (more than 100).

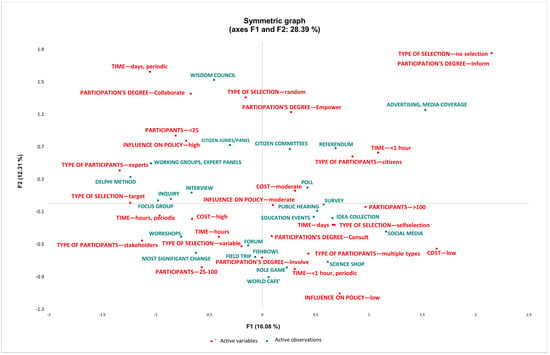

The results of the Correspondence Analysis (CA) based on various indicators associated with different modes of public participation are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Correspondence Analysis (CA)—symmetric graph of participatory techniques.

The results evidence that the 24 participatory techniques can be grouped according to four dimensions. A first group (upper left quadrant—Figure 2) includes those processes with a high degree of participation (collaborate) and a contextual high potential influence on policies, but long times and a low number of participants (less than 25). This group includes participatory techniques such as citizen juries, citizen committees, and wisdom councils. The second group (upper right quadrant—Figure 2) includes participatory techniques with a low time (less than one hour) and costs in terms of resources, but a low degree of participation (information) and influence on policies, such as social media, adverting, surveys, and polls. This group includes participatory techniques addressed to citizens without a selection of them (information shower). The third group (lower left quadrant—Figure 2) consists of those techniques with a medium–high degree of participation (involve) and medium–high time and costs in terms of resources, with a number of participants (mainly stakeholders) between 25 and 100. This group of participatory techniques—e.g., forums, workshops, and field trips—has a medium–low influence on policies. The fourth group (lower right quadrant—Figure 2) includes participatory techniques characterized by a medium degree of participation (consult) with a variable number of participants (from 25–100 to more than 100) identified through self-selection, such as education events, role games, science shops, and world cafés. Based on the number of participants, the participatory techniques included in the fourth group can be developed over different periods of time ranging from one day for a single event or less than an hour but on a periodic basis.

Observing the two axes, the results show for the first axis (F1) a contrast between the self-section of the participants (with positive values) and the target selection (with negative values). Self-selection is suitable for involving many participants (more than 100) in participatory techniques that do not require a specific target of participants (e.g., social media, surveys, and polls). Conversely, target selection is suitable for those participatory techniques that do not require a high number of participants, but the choice of participants is key to the success of the participatory process (e.g., Delphi method and focus group). For the second axis (F2), a contrast between the degree of participation “empower” (with positive values) and “involve” (with negative value) is highlighted. Empower the participants is a degree of involvement more typical of participatory techniques such as wisdom councils, while involve the participants is commonly used for participatory techniques such as world cafés and role games.

3.3. Transfer to Forest Policies

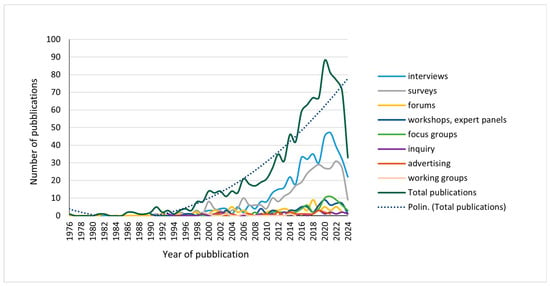

The first publication on participatory processes in forest policy in the Scopus database dates back to 1976. Table 5 shows the number of publications per technique (arranged in descending order) and the years of the first and last publications.

Table 5.

Participatory techniques adopted in forest policy.

Interviews and surveys are the two most common participatory techniques used in forestry policies and strategies, followed by forums, workshops, and focus groups. These three techniques—although widespread—currently account for about 15%–20% of the first two, which are currently the most significant in the context of forest policies. The Delphi method, referendums, field trips, working and public groups, focus groups, and advertising are techniques that were widespread in the forest policy sector in the late 1990s and early 2000s. As shown in Table 3, techniques like social media, role games, and citizen committees have grown, especially in recent years, emphasizing the increasing complexity and diversification of research approaches.

Figure 3 shows that the overall number of publications has significantly increased over the years, especially after 2000. The trend of total publications shows a sharp rise peaking around 2020, followed by a decline in the last four years.

Figure 3.

Number of publications over the years (considering only participatory techniques with at least 10 publications).

4. Discussion

The participatory democracy is based on active and creative participation in policy-making in which stakeholders and citizens have the possibility to participate in the political sphere and public life [44]. The application of the participatory democracy principles to forest policies and strategies presupposes that all the actors—from public authorities to citizens—are actively involved in decision-making processes at all the different levels (from national to municipal), but not necessarily in the same way. In the reason for this, the choice of the most suitable participatory technique to adopt in a decision process is linked to several variables which are listed as follows:

- The objective of the participatory process;

- The spatial scale of the process;

- The kind of information needed to develop the process;

- The kind and number of actors who should be involved more or less actively.

The objective of the actors’ involvement and the type of contribution desired from participants are the first aspects to consider before structuring a participatory process [39]. In fact, the results of the present study highlighted that some participatory techniques are designed to inform participants about a topic (e.g., advertising, social media, and public hearings), while others are aimed at collecting opinions to gather public feedback on policy alternatives and suggestions that could potentially influence decision-making (e.g., surveys, inquiries, interviews, and science shops). In other cases, the decision-making process actively involves citizens and/or experts in shaping final policies to achieve more effective and efficient outcomes through collaboration (e.g., wisdom councils and citizen juries). In the international literature, several authors have emphasized how a clear and well-defined participatory objective is fundamental to legitimize the process itself [9,45]. In some cases, the main participatory objectives can be to (i) improve and facilitate the decision-making process by increasing the level of trust among participants [44,46] or reduce the conflicts between opposing interest groups [47]; (ii) include marginalized categories of social actors in the process and choices [48]; and (iii) create a sense of community in the management of common goods/natural resources [49]. If the priority objective is to increase the level of mutual trust between participants, it is necessary to adopt techniques based on dialogue and mutual discussion in periodic meetings supported by a facilitator, such as working groups. Conversely, if the priority objective is to include the opinions and point of views of the marginalized social actors in the final choices, single events supported by a facilitator may also be appropriate.

The results of the literature review showed that the kind and number of actors involved in the participatory process are two key variables to take into consideration. The actors to be involved depend primarily on the spatial context or scale (national, regional, or local) and on the kind of information/data to be collected [50]. Regarding the spatial scale, the issues dealt with in the participatory process may be of interest to local, national, and transnational policies [26,27]. The spatial scale where the participatory policy process is applied influences not only the technique but also the tools, the number of stakeholders/citizens, the participants’ selection modalities, and the time. In fact, the definition of a national forest policy should engage multiple stakeholders but with a medium–low degree of participation (i.e., consultation or involvement). Instead, a regional forest program or a landscape forest planning should engage only those who have a “stake” related to the territory but with a high degree of participation (i.e., collaboration or empowerment).

Regarding the kind of information, if specialized—e.g., technical or scientific—information is needed for the policy process, only experts are involved. On the other hand, if the objective is to inform or to implement a comparison, it is necessary to involve experts, stakeholders, and citizens. In addition, the data collected can be either quantitative (the data are numbered, numerable, or measurable), qualitative (the data are interpretative, descriptive, and language-related) or both [25]. Additionally, different tools can be used, depending on the level of detail of the information requested. In general, techniques can be developed in presence (face-to-face), via online tools, or in hybrid mode [42,51].

The results of this study showed that some participatory techniques involve multiple types of actors (experts and citizens in science shops; experts, citizens and policy makers in fishbowls), while others focus only on one type of actors (citizens in wisdom councils and experts in the Delphi method and expert panels). In the literature, some authors have highlighted that the engagement of different types of actors could be more efficient when the topics are complex [36,52]. In fact, experts can play a role in translating stakeholder/citizen discourses into policy options [36] and improving knowledge transfer through cross-scientific collaboration and coalitions with stakeholders [53]. Furthermore, the results highlighted that increasing the types of actors involved in the process increases the complexity but can also increase the usefulness of the data for policy implementation such as citizen juries/panels and fishbowls. Conversely, the number of participants is a good indicator when the participatory process aims to collect or disseminate information (e.g., citizens or stakeholders’ needs, expectations, and knowledge), while it can be counterproductive when such information must be included in policies (information overload). In fact, adverting and social media are the two techniques with the highest number of participants but with a low level of influence on policies. As emphasized by Słupińska et al. (2022) [54], social media are a new tool for communicating and promoting sustainable forest management towards society.

The results of the CA highlight the direct relationship between the degree of participation and the potential impact of participatory power on policies. The greater the involvement of different actors, the greater the corrective power of the participation process that emerges. When multiple actors are involved and degree of participation is high, participatory processes have great force in correcting the societal power imbalance. In fact, when actors that have different power positions in the society are engaged in the process, this imbalance is in part addressed and levelled [55]. Furthermore, a low level of participation (inform or consult) is related to a possibly high number of unselected participants with low time and costs for the implementation of the participatory process.

The participatory techniques and processes identified in the forest policies and strategies framework confirmed that participatory processes have increased their spread in the forestry sector in the wake of the Rio Conference and the Intergovernmental Panel on Forests in the late 1990s and the early 2000s. However, it is important to highlight the low and repetitive number of participatory techniques adopted in forest policies. This fact is related to a low level of social science knowledge adopted and the static nature of the forest sector. The static nature of the forest sector has been emphasized by Notaro et al. [56], who have observed that innovations struggle to be introduced by forest actors. Our results showed that some participatory techniques have been widely used in different fields and contexts (i.e., focus groups and surveys), while others are still almost unknown to the forestry scientific and policy community. The preference for certain techniques is due on the one hand to their ease of application and on the other to the fact that they are now common knowledge in the forest sector.

It is important to remark that the choice of the most appropriate participatory technique to implement in a decision process is fundamental. In fact, the adoption of techniques that are inappropriate for the participatory method chosen or for the specific phase of the process, or unsuitable for the social and cultural context of the forest policies application can translate to the failure of the process. Furthermore, the implementation of a participatory technique that does not have a strong link with technical aspects of policies at stake is another cause of failure. In fact, those responsible for participation need to have in-depth knowledge of issues dealing with forest policies and strategies and to maintain continuous and close contact with the context where forest policies are implemented throughout the entire process. Otherwise, participatory processes and policy implementation proceed along two separate tracks.

Finally, another common mistake—that it is easy to fall into either accidentally or intentionally—is linked to the kind and number of actors who should be involved in the process. When some of the actors are neglected, the result is that opinions, points of view, and requests are not considered and the process loses transparency and openness.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Recommendations to Take Home

The comprehensive overview of various participatory techniques of public participation offered in the present study has the advantage of considering critical factors related to the various techniques. In reason of this, the overview can better support decision-makers and practitioners involved in public engagement initiatives. In fact, it helps to select the most appropriate method based on the desired level of participation, available resources, and policy objectives, enabling informed decision-making and maximizing the impact of public participation efforts.

It is important to remark that the adoption of participatory techniques represents an opportunity for the implementation of forest policies and strategies, provided that the strengths and limitations are assessed and evaluated in the specific context of application and remembering that there exist, at a methodological level, appropriate and applicable recipes for each situation.

The present study has also shown the complexity of participatory processes, where diverse variables must run together with harmony to obtain the desired results. This complexity must be taken in consideration while maintaining a high degree of analytical and methodological openness during the development of the participatory processes. In this way, the constantly existing contingencies and contradictions that emerge during the process can be considered and addressed.

The wish is that this kind of research may be a useful instrument in the hands of forest managers and decision-makers when choosing tools to take into consideration the evolution of society’s demands, a crucial aspect during periods of rapid and important change, such the ones we are facing today. Most of all, the actual challenge will be to encourage the spread of collaborative practice—like the participatory processes—to support the actual belief that forests ultimately belong to the community and are a common good to be protected and managed collectively.

5.2. Strengths and Weaknesses of the Study

From a methodological point of view, the main strength of the study is to have clearly identified 24 participatory techniques by grouping together similar ones but known in the literature with different names. However, this inevitably led to the identification of a different number of studies for each participatory technique, highlighting the terminological synonyms used. Conversely, the main weakness is having considered the Scopus-indexed publications, which are almost exclusively in English, while those in other languages have not been included. A further weakness of the study concerns the results of the Correspondence Analysis, which should be considered purely descriptive of the key characteristics of the 24 participatory techniques considered. In fact, the inertia value of the CA was found to be 28.39% (F1 of 16.08% and F2 of 12.31%), probably due to the large variability present in the data matrix, and therefore our conclusions can only be limited.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.B., I.D.M. and A.P.; methodology, S.B.; software, A.P.; investigation, S.B.; data curation, S.B. and A.P.; writing—original draft preparation, S.B., A.P. and I.D.M.; writing—review and editing and project administration, I.D.M.; funding acquisition, I.D.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work was supported by the ForestValue2 Project “Innovating forest-based bioeconomy” (Horizon Europe GA no. 101094340), which runs from January 2023 until December 2027.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available by requesting them from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Burt matrix for the participatory techniques used in participatory democracy.

References

- Pateman, C. Participation and Democratic Theory; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Barber, B.R. Participatory Democracy. In The Encyclopedia of Political Thought; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Vitale, D. Between deliberative and participatory democracy: A contribution on Habermas. Philos. Soc. Crit. 2006, 32, 736–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bherer, L.; Dufour, P.; Montambeault, F. The participatory democracy turn: An introduction. J. Civ. Soc. 2016, 12, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Porta, D. Meeting Democracy: Power and Deliberation in Global Justice Movements; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Knopp, T.B.; Calbeck, E.S. The role of participatory democracy in forest management. J. For. 1990, 88, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchy, M.; Hoverman, S. Understanding public participation in forest planning: A review. For. Policy Econ. 2000, 1, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttoud, G.; Solberg, B.; Tikkanen, I.; Pajari, B. The Evaluation of Forest Policies and Programmes. Eur. For. Inst. (EFI) 2004, 52, 216. [Google Scholar]

- Cantiani, M.G. Forest planning and public participation: A possible methodological approach. iForest 2012, 5, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paletto, A.; Cantiani, M.G.; De Meo, I. Public Participation in Forest Landscape Management Planning (FLMP) in Italy. J. Sustain. For. 2015, 34, 465–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, N. Participation or involvement? Development of forest strategies on national and sub-national level in Germany. For. Policy Econ. 2018, 89, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hügel, S.; Davies, A.R. Public participation, engagement, and climate change adaptation: A review of the research literature. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2020, 11, e645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelstrand, M. Participation and societal values: The challenge for lawmakers and policy practitioners. For. Policy Econ. 2002, 4, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPF (Intergovernmental Panel on Forests). Report of the Ad Hoc Intergovernmental Panel on Forests on Its Fourth Session/Commission on Sustainable Development, Fifth Session; (UN DPCSD E/CN. 17/1997/12); IPF: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kouplevatskaya, I. The national forest programme as an element of forest policy reform: Findings from Kyrgyzstan. Unasylva 2006, 225, 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Balest, J.; Hrib, M.; Dobšinská, Z.; Paletto, A. Analysis of the Effective Stakeholders’ Involvement in the Development of National Forest Programmes in Europe. Int. For. Rev. 2016, 18, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MCPFE (1998): Third Ministerial Conference on the Protection of Forests in Europe. General Declaration and Resolutions Adopted. Resolution L 1., Liaison Unit in Lisbon. Available online: https://foresteurope.org/about/ministerial-conferences/lisbon/ (accessed on 9 May 2024).

- European Commission. Communication of 3 November 1998 from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament on a Forestry Strategy for the European Union. In COM 1998/649 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. New EU Forest Strategy for 2030. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, COM, 572 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sandström, C.; Pilstjärna, M.; Hannerz, M.; Sonesson, J.; Nordin, A. A One-Size-Fits-All Solution for Forests in the European Union: An Analysis of the New EU Forest Strategy. 2022. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4037179 (accessed on 9 May 2024).

- Maas, F.; Wolf, S.; Hohm, A.; Hurtienne, J. Citizen Needs—To Be Considered. I-Com 2021, 20, 141–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikkanen, J. Participatory turn—And down-turn—In Finland’s regional forest programme process. For. Policy Econ. 2018, 89, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2020, 372, n71. [Google Scholar]

- Arnstein, S.R. A ladder of citizen participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A.R.; Wentholt, M.T.; Rowe, G.; Frewer, L.J. Expert involvement in policy development: A systematic review of current practice. Sci. Public Policy 2014, 41, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, G.; Frewer, L. Public participation methods: A framework for evaluation. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 2000, 25, 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanz, P.; Fritsche, M. La Partecipazione dei Cittadini: Un Manuale. Metodi Partecipativi: Protagonisti, Opportunità e Limiti; Regione Emilia-Romagna, Assemblea Legislativa: Bologna, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Greenacre, M.J. Theory and Applications of Correspondence Analysis; Academic Press: London, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- International Association for Public Participation. Available online: https://www.iap2.org/ (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Savini, F. The Endowment of Community Participation: Institutional Settings in Two Urban Regeneration Projects. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2010, 35, 949–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.S.; Graves, A.; Dandy, N.; Posthumus, H.; Hubacek, K.; Morris, J.; Prell, C.; Quinn, C.H.; Stringer, L.C. Who’s in and why? A typology of stakeholder analysis methods for natural resource management. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 1933–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnerooth-Bayer, J.; Scolobig, A.; Ferlisi, S.; Cascini, L.; Thompson, M. Expert engagement in participatory processes: Translating stakeholder discourses into policy options. Nat. Hazards 2015, 81, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, S.; Maule, J.; Papamichail, N. Decision Behaviour, Analysis and Support; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- French, S.; Bayley, C. Public participation: Comparing approaches. J. Risk Res. 2010, 14, 241–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäck, A.; Friedrich, P.; Ropponen, T.; Harju, A.; Hintikk, K.A. From design participation to civic participation–participatory design of a social media service. Int. J. Soc. Humanist. Comput. 2013, 14, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krick, E. Participant Selection Modes for Policy-Developing Collectives. In Expertise and Participation. Palgrave Studies in European Political Sociology; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 137–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, G.; Horlick Jones, T.; Walls, L.; Pidgeon, N. Difficulties in evaluating public engagement initiatives: Reflections on an evaluation of the UK GM Nation? Public debate about transgenic crops. Public Underst. Sci. 2005, 14, 331–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rough, J. Dynamic facilitation and the magic of self-organizing change. J. Qual. Particip. 1997, 20, 34–38. [Google Scholar]

- Luyet, V.; Schlaepfer, R.; Parlange, M.B.; Buttler, A. A framework to implement Stakeholder participation in environmental projects. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 111, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannay, D. ‘Who put that on there … why why why?’ Power games and participatory techniques of visual data production. Vis. Stud. 2013, 28, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadka, C.; Prasad Aryal, K.; Edwards-Jonášová, M.; Upadhyaya, A.; Dhungana, N.; Cudlin, P.; Vacik, H. Evaluating participatory techniques for adaptation to climate change: Nepal case study. For. Policy Econ. 2018, 97, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geekiyanage, D.; Fernando, T.; Keraminiyage, K. Mapping Participatory Methods in the Urban Development Process: A Systematic Review and Case-Based Evidence Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, J.J. Participatory democracy: Drawing on C. West Churchman’s thinking when making public policy. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2023, 20, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landauer, M.; Komendantova, N. Participatory environmental governance of infrastructure projects affecting reindeer husbandry in the Arctic. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 223, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nijnik, M.; Mather, A. Analyzing public preferences concerning woodland development in rural landscapes in Scotland. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2008, 86, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dral, G.J.; Witte, P.A.; Hartmann, T. The impact of participatory decision-making on legitimacy in planning. Disp—Plan. Rev. 2023, 59, 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, R.J. Beyond radicalism and resignation: The competing logics for public participation in policy decisions. Policy Press 2017, 45, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rukunuddin Ahmed, M. Gender differences of participation in social forestry programmes in Bangladesh. For. Trees Livelihoods 2003, 13, 79–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, I. Participation experiences and civic concepts, attitudes and engagement: Implications for citizenship education projects. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2003, 2, 430–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, V.; Barreira, A.P.; Loures, L.; Antunes, D.; Panagopoulos, T. Stakeholders’ Engagement on Nature-Based Solutions: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidwell, D.; Schweizer, P.-J. Public values and goals for public participation. Environ. Policy Gov. 2020, 31, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grilli, G.; De Meo, I.; Garegnani, G.; Paletto, A. A multi-criteria framework to assess the sustainability of renewable energy development in the Alps. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2017, 60, 1276–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werland, S. Global Forest governance—Bringing forestry science (back) in. For. Policy Econ. 2009, 11, 446–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Słupińska, K.; Wieruszewski, M.; Szczypa, P.; Kożuch, A.; Adamowicz, K. Social Media as Support Channels in Communication with Society on Sustainable Forest Management. Forests 2022, 13, 1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpentier, N. Beyond the ladder of participation: An analytical toolkit for the critical analysis of participatory media processes. In Critical Perspectives on Media, Power and Change; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2018; Volume 23, pp. 67–85. [Google Scholar]

- Notaro, S.; Gios, G.; Paletto, A. Using the Contingent Valuation Method for ex ante service innovation evaluation. Schweiz. Z. Fur Forstwes. 2006, 157, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).