Abstract

Cyclocarya paliurus, native to China, is a medicinal and edible plant with important health benefits. Anthracnose is an emerging disease in southern China that causes severe economic losses and poses a great threat to the C. paliurus tea industry. However, to date, the species diversity of pathogens causing C. paliurus anthracnose has remained limited. From 2018 to 2022, a total of 331 Colletotrichum isolates were recovered from symptomatic leaves in eight major C. paliurus planting provinces of southern China. Phylogenetic analyses based on nine loci (ITS, GAPDH, ACT, CHS-1, TUB, CAL, HIS3, GS and ApMat) coupled with phenotypic characteristics revealed that 43 representative isolates belonged to seven known Colletotrichum species, including C. brevisporum, C. fructicola, C. gloeosporioides sensu stricto, C. godetiae, C. nymphaeae, C. plurivorum and C. sojae. Pathogenicity tests demonstrated that all species described above were pathogenic to wounding detached leaves of C. paliurus, with C. fructicola being the most aggressive species. However, C. brevisporum, C. plurivorum and C. sojae were not pathogenic to the intact plant of C. paliurus. These findings reveal the remarkable species diversity involved in C. paliurus anthracnose and will facilitate further studies on implementing effective control of C. paliurus anthracnose in China.

1. Introduction

Cyclocarya paliurus (Batal.) Iljinsk., commonly called “sweet tea” in China, is the sole extant species belonging to the Juglandaceae family, and is naturally distributed in the central southern mountains [1]. In Chinese folk medicine, leaves of C. paliurus have been used in traditional tea or medicine for the treatment of diabetes mellitus or obesity for more than 1000 years [2]. In recent years, considerable attention has been given to C. paliurus because pharmacological studies have suggested that its leaves exhibit hypoglycaemic [3], hypolipidemic [4], antioxidant [5], anti-HIV-1 [6] and anticancer [7] properties. Consequently, C. paliurus leaves were investigated as a substitute for common tea (Camellia sinensis) and authorized as a new food raw material by the National Health and Family Planning Commission of China in 2013 [8]. During the past few years, large-scale plantings of C. paliurus have been established for leaf-harvesting to meet the increasing demand for tender C. paliurus leaves for tea production or medical use in China [9]. The cultivation of C. paliurus is beneficial for the national economy and livelihoods of local farmers but also leads to infectious diseases.

The destructive pathogens causing C. paliurus anthracnose were attributed exclusively to Colletotrichum spp. within the C. gloeosporioides species complex [10], which are also responsible for anthracnose on numerous tree species and crops in subtropical and tropical regions. Although historical data are unavailable, it has been recently reported in Jiangsu Province that the incidence of C. paliurus anthracnose can reach 64% in some newly established plantations and can also result in mortality of branches and even plants in severe cases [10]. In the presence of appropriate temperatures and high moisture conditions in the fields of southern China, Colletotrichum spp. can form fruiting bodies and spread rapidly; thus, anthracnose leads to significant losses in yield and economy, ultimately posing a major threat to the C. paliurus tea industry in China [11].

C. paliurus anthracnose is considered an emerging and serious disease since multiple Colletotrichum species can coexist on a single host plant, even within the same lesion [10]. Hence, accurate identification of the Colletotrichum spp. associated with C. paliurus anthracnose is highly important for understanding its epidemiology and effective application of management strategies. Identification and circumscription of Colletotrichum spp. have historically been based on symptoms in particular hosts, host range and a series of morphological features [12]. Nevertheless, the use of these conventional criteria has failed to delimit Colletotrichum spp. due to phenotypic variations in the same species under different environmental conditions [12,13]. According to Liu et al. [14], the current classification system of Colletotrichum comprises 15 species complexes, all of which can be differentiated from each other by utilizing the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region alone, whereas the species-within-species complex can be resolved by sequence differences in additional genes, such as five loci (GADPH, CHS-1, HIS3, ACT and TUB) that have been used for the C. acutatum (Acutatum) and C. orchidearum (Orchidearum) species complexes [15,16], while two additional loci (GS and ApMat) have been employed for the C. gloeosporioides (Gloeosporioides) species complex [13,17].

Anthracnose has increasingly aroused concern among growers in the C. paliurus tea-producing areas of southern China. Hence, the objectives of this study were (i) to investigate the diversity of Colletotrichum species associated with C. paliurus anthracnose among the major production provinces in southern China based on morphological features and phylogenetic analyses and (ii) to determine the distribution and pathogenicity of these Colletotrichum species in the region.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Fungal Isolation

From July to October in 2018–2022, C. paliurus leaves exhibiting typical anthracnose symptoms (Figure 1) were collected from the eight main C. paliurus tea-producing provinces (Fujian, Guangxi, Guizhou, Hubei, Hunan, Jiangxi, Sichuan, and Zhejiang; Table A3) of southern China. One commercial plantation was surveyed per location/county. Before sampling, the disease incidence was estimated by randomly counting and rating 100 plants after zigzag walking throughout the orchards. In total, 83 leaf samples were obtained (Table A3). Symptomatic leaves were examined with a ZEISS Stereo Microscope (Discovery V20, Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) to observe asexual or sexual fungal structures for preliminary identification. Foliar fragments (lesion margin; 4 mm in side length) without sporulation were surface-sterilized (1% NaClO for 45 s, followed by 70% ethanol for 45 s, rinsed in sterile distilled water three times and dried), placed to potato dextrose agar (PDA; 200 g/L of potato; 20 g/L of glucose; 20 g/L of agar; Solarbio, Beijing, China) plates supplemented with 100 μg/mL ampicillin, and incubated at 25 °C in the dark. For symptomatic leaves with sporulation, conidial suspensions were collected by rinsing fruiting bodies with sterile distilled water, diluted to a concentration of 1 × 104 cfu/mL, and coating them on the surface of 2% water agar (WA; Solarbio, China) [18]. The edges of the emerging myceliawere were transferred onto fresh PDA plates, and pure cultures were obtained by single spore (conidium or ascospore) isolation following the methods of Cai et al. [19]. Representative isolates were deposited at Nanjing Forestry University (NJFU) and the Microbiological Culture Collection Centre at Jiangsu Vocational College of Agriculture and Forestry (JSAFC).

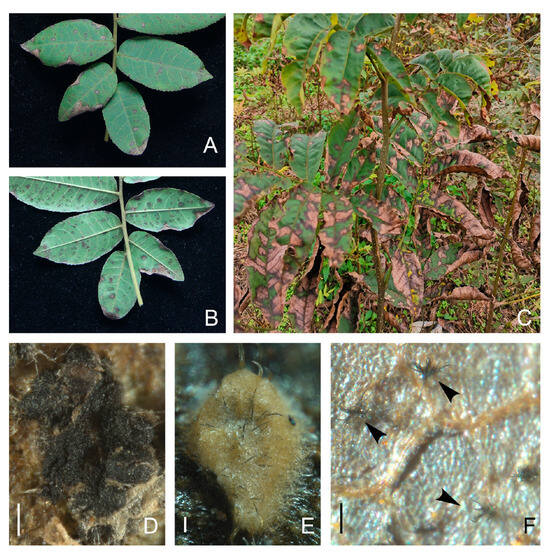

Figure 1.

Typical symptoms of Cyclocarya paliurus anthracnose. (A) Front and (B) reverse view of irregular necrotic lesions on leaves; (C) field symptoms; (D) Colletotrichum fruiting bodies of ascomata and (E,F) Acervuli developed on diseased leaf tissues, with arrows point to setae. Scale bars: (D) =200 μm; (E) =50 μm; (F) =100 μm.

2.2. Molecular Identification

2.2.1. DNA Extraction

Aerial mycelia of each single-spore isolate were collected with a sterile scalpel from a 5-day-old colony and placed in a sterile 2 mL centrifuge tube. Total genomic DNA was extracted using a Genomic DNA Extraction Kit (D2300, Solarbio, Beijing, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA concentrations were quantified using a Nanodrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and the DNA was manually diluted to 100 ng/μL for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification.

2.2.2. Multigene Amplification and Sequencing

As an initial analysis of genetic diversity, portions of the ITS and GADPH loci were amplified from all the isolates to select representative sequences for further multilocus phylogenetic analysis The genetic loci and primers used for amplification and sequencing are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Genetic loci and primers used in this study.

The procedure and conditions for PCR amplification were adopted from Zheng et al. [10], except for HIS3, for which the annealing temperature was 55 °C. The amplification products were visualized on a 1.2% agarose gel after electrophoresis (120 V, 20 min), and positive amplicons were purified and sequenced by Sangon Biotechnology Company (Shanghai, China). The forward and reverse sequences of all representative isolates were assembled, and consensus sequences were deposited in GenBank (Table A1 and Table A2).

2.2.3. Phylogenetic Analyses

Reference sequences from authentic specimens of the Gloeosporioides, Acutatum, Magnum and Orchidearum complexes were retrieved from GenBank and aligned with sequences generated in the present study to construct phylogenetic trees. Monilochaetes infuscans (CBS 869.96) was included as the outgroup taxon. Sequence alignments of each locus were performed with BioEdit (version 7.1.9) and optimized by manual adjustment to allow for maximum alignment. Subsequently, multiple loci were concatenated with SequenceMatrix 1.8 [29].

The concatenated sequences of different gene combinations were used to infer phylogenetic relationships under the maximum-likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) criteria, implemented in MEGA X [30] and MrBayes 3.2.6 [31], respectively. MEGA was first used to determine the best model of nucleotide substitution for the combined dataset using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). The ML analysis utilized the nearest-neighbor-interchange (NNI) heuristic search method, with clade stability assessed by 1000 bootstrap replicates [30]. For BI, two independent analyses were conducted with four Markov chains, evaluating 3 × 106 generations, with samples taken every 1000th generation. Posterior probabilities (PPs) were calculated after discarding the first 25% of generations as burn-in. A PP equal to 1.00 and bootstrap values (Bv) greater than 85% were taken as evidence for branch support. The consensus tree was visualized using FigTree (version 1.3.1).

2.3. Phenotypic Analysis

For macroscopic and microscopic characterization of representative Colletotrichum isolates, mycelial blocks (2–3 mm2) were aseptically removed from the edge of actively growing cultures, transferred to fresh PDA and synthetic nutrient-poor agar (SNA [18]) plates and incubated as described above. The culture characteristics were recorded at 6 days after inoculation, and images of the upper and lower surfaces of the colonies were taken. The colony diameters on the PDA plates were measured at 24 h intervals to calculate the mean daily growth (mm/d). The experiment was performed as a randomized complete block, with three replicates for each isolate. Conidial and ascospore suspensions of each selected isolate were prepared in sterile water from conidial masses and ascomata on PDA plates, respectively. Conidial appressoria were induced via a previously published technique [32]. The conidiophores were observed on the colonies grown on PDA or SNA plates. At least 100 measurements were conducted for each Colletotrichum fungal structure (conidia, appressoria and ascospores) with a ZEISS fluorescence microscope (Axio Imager A2m, Carl Zeiss, Germany) using differential interference contrast.

2.4. Pathogenicity Tests

Three representative isolates of each identified Colletotrichum species were selected to confirm their pathogenicity on detached leaves and whole plants of C. paliurus using the mycelial plug method because some Colletotrichum species showed no satisfactory sporulation on culture media. Prior to inoculation, asymptomatic leaves of C. paliurus were surface-disinfected and air-dried as described above.

To inoculate the detached C. paliurus leaves, both wounding and nonwounding techniques were utilized. A mycelial plug (5 mm in diameter) was prepared from a fresh colony as mentioned above, and the plug was adhered to the adaxial surface of each leaf, which was punctured with a hot-top needle (0.5-mm in diameter) or left unwounded. A noncolonized PDA plug was used to treat the control leaves. All the inoculated leaves were then placed in sterilized transparent containers (260 × 260 × 30 mm) with a layer of moist absorbent paper to maintain high relative humidity (RH). The containers were sealed with parafilm and maintained in a growth chamber at 25 °C with a 12 h photoperiod [33]. The experiment was conducted in three replicates for each treatment, and the entire experiment was repeated twice.

Plant inoculations were performed on newly developed leaves on potted seedlings of C. paliurus using the wounding method as described above. C. paliurus seedlings treated with noncolonized PDA plugs were used as controls. All the inoculated seedlings were subsequently placed in an incubator (25 °C, 12 h photoperiod, 90%–95% RH). Three replicates were performed for each treatment, and the entire experiment was repeated twice.

Inoculated leaves were monitored and recorded for symptom development of anthracnose for up to three weeks. Disease incidence (percentage of infected leaves) was evaluated at 10 days post inoculation (dpi), and severity was assessed by measuring lesion length in two perpendicular directions at 15 dpi. To fulfil Koch’s postulates, all Colletotrichum isolates used in pathogenicity tests were reisolated from the infected leaves and their identity were confirmed according to cultural characteristics and GADPH sequences as described above. In addition, inoculated leaves bearing typical Colletotrichum conidial masses or ascomata were collected and prepared in accordance with Fu et al. [18]. Photomicrographs were taken under a ZEISS fluorescence microscope (Stereo Discovery V20, Carl Zeiss, Germany).

2.5. Data Analyses

The data used for the statistical analyses of the morphological characteristics and virulence of Colletotrichum species are presented as the mean ± standard error (SE) or standard deviation (SD) and were analyzed using Origin 2021. Differences between treatments were evaluated using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) in SPSS 26.0 software. When ANOVA revealed significant differences, the treatment means were compared according to Tukey’s honestly significant difference test (p = 0.05).

3. Results

3.1. Symptomatology and Fungal Isolation

The typical symptoms of C. paliurus anthracnose observed in the present study were initially circular or irregularly shaped black-brown spots that gradually enlarged and then collapsed into necrotic lesions, turning grey, white or brown in the middle and dark brown at the edges (Figure 1A,B). Severe infection resulted in extensive early defoliation and eventually the death of the whole plant (Figure 1C). Under high-humidity conditions, typical structures of Colletotrichum, such as ascomata (Figure 1D), conidiomata (Figure 1E), and setae (Figure 1F), appeared on these lesions. In total, 337 isolates were recovered from symptomatic C. paliurus leaves that were collected in eight surveyed provinces of southern China. According to ITS sequence alignment, 331 isolates were identified as Colletotrichum spp. Other isolates belonging to Pestalotiopsis, Alternaria and Phomopsis were also isolated, but those were not further studied for the time being (Table A3).

3.2. Molecular Identification and Phylogenetic Analyses

Based on the alignment of ITS and GADPH sequences and cultural characteristics, all Colletotrichum isolates were grouped into the Gloeosporioides (249 isolates), Acutatum (37 isolates), Orchidearum (32 isolates) and Magnum complexes (13 isolates). Subsequently, a subset of 43 isolates representing different geographic origins, phenotypic characteristics (conidial shape and size) and genetic diversity (ITS and GADPH sequence analysis) was selected for further investigation (Table A1 and Table A2).

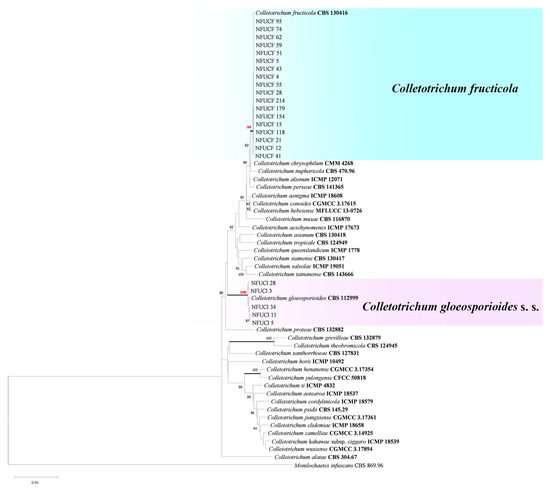

For isolates in the Gloeosporioides complex, phylogenetic analyses of eight concatenated loci (ITS, GADPH, CHS-1, ACT, TUB, CAL, GS and ApMat) sequences were carried out with corresponding sequences from 39 authentic specimens (Table A1). The concatenated matrixes of the aligned dataset were composed of 3537 characters and gaps in the alignment. The GTR+G model was selected based on the AIC to reconstruct the ML tree. For BI analysis, the corresponding models were selected by MrModeltest: GTR+I+G for ITS; K80+G for GAPDH and ApMat; HKY+I+G for CHS-1; and GTR+G for ACT, TUB, CAL and GS. The isolates in the Gloeosporioides complex were clustered into two well-supported clades (Bv > 99% and Bayesian PP = 1.00): 18 isolates were grouped into the C. fructicola clade, and five were clustered with C. gloeosporioides s. s. (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Phylogram tree inferred from a maximum likelihood analysis based on eight-gene combined dataset (ITS, GADPH, CHS-1, ACT, TUB, CAL, GS and ApMat) alignments of the Colletotrichum gloeosporioides species complex. Bootstrap support values (Bv) above 80% are shown at the nodes. Branches in bold represent strong support (posterior probability values = 1.00) confirmed by Bayesian analysis. Ex-type or other authoritative cultures are emphasized in bold font. The tree was rooted to Monilochaetes infuscans (CBS 869.96). The scale bar indicates the average number of expected changes per site.

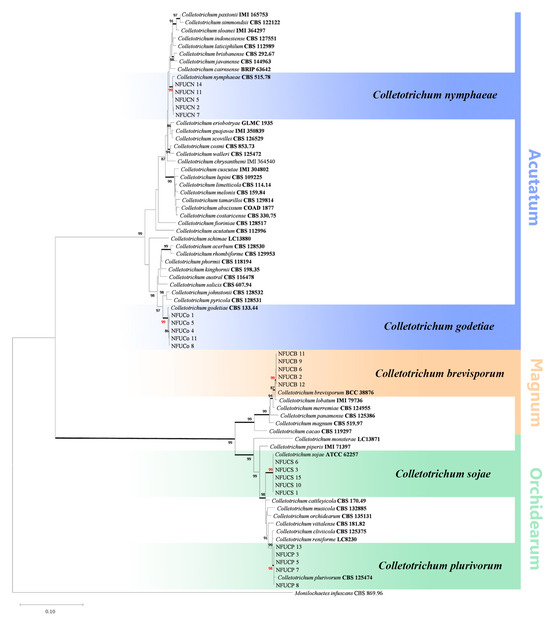

To identify the Colletotrichum species within the Acutatum, Magnum and Orchidearum complexes, a dataset of six combined genes (ITS, GADPH, CHS-1, ACT, TUB and HIS3) from 49 authentic specimens was used, and the dataset comprised 1905 characters after alignment. The ML tree was reconstructed utilizing the GTR+G+I model. The best models for BI were found by MrModeltest: GTR+I+G for ITS, CHS-1 and HIS3, K80+G for GADPH, GTR+G for ACT, and HKY+I+G for TUB. The isolates in the Acutatum complex could be well defined as C. nymphaeae and C. godetiae because five isolates clustered together with the C. nymphaeae ex-type strain CBS 515.78 with strong support (99% Bv/1.00 PP), and five isolates clustered in another highly supported clade (99% BP/1.00 PP) with the C. godetiae type strain CBS 133.44. Among the isolates in the Orchidearum complex, five were grouped in C. plurivorum Damm, Alizadeh & Toy. Sato (98% Bv/1.00 PP), whereas the other five isolates were clustered with C. sojae Damm & Alizadeh (99% Bv/1.00 PP). Additionally, the remaining five isolates clustered with the C. brevisporum authentic strain BCC 38876 with high support (99% Bv/1.00 PP) in the Magnum clade (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic tree resulting from maximum likelihood analysis using the six-gene combined dataset (ITS, GADPH, CHS-1, ACT, TUB and HIS3) alignments of the Colletotrichum acutatum (Acutatum), C. magnum (Magnum) and C. orchidearum (Orchidearum) species complexes. Bootstrap support values (Bv) above 80% are shown at the nodes. Branches in bold represent strong support (posterior probability values = 1.00) confirmed by Bayesian analysis. Ex-type or other authoritative cultures are emphasized in bold font. The tree was rooted with Monilochaetes infuscans (CBS 869.96). The scale bar indicates the average number of expected changes per site.

3.3. Morphological Characteristics

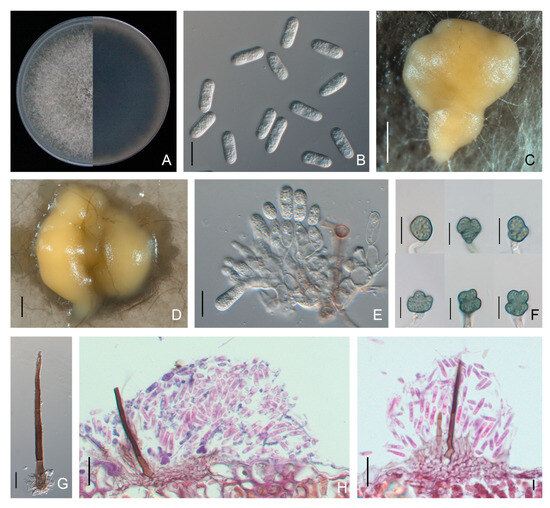

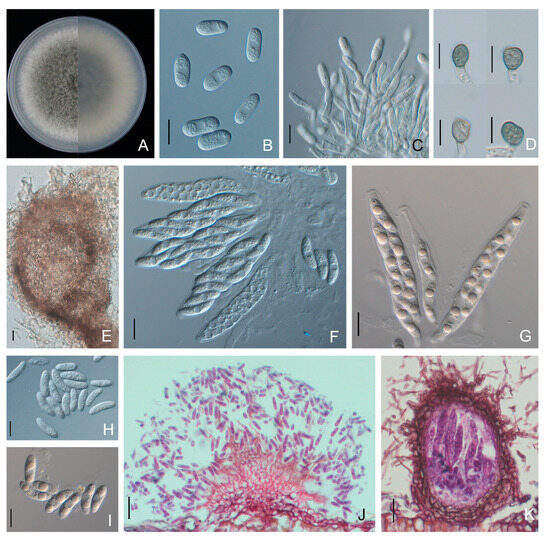

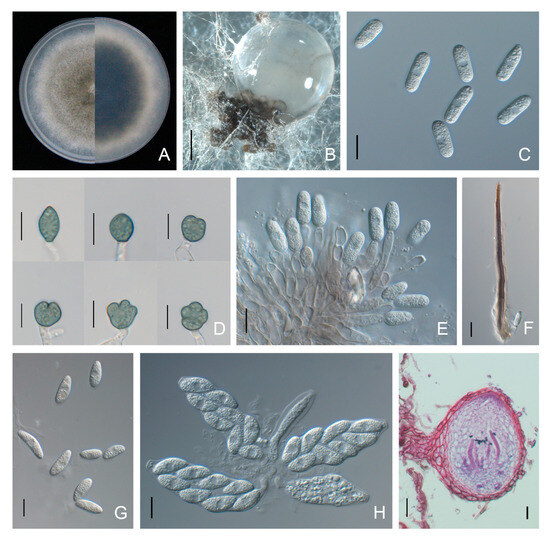

Colonies of C. brevisporum isolates on PDA were dark grey with grey aerial mycelium and edges (Figure 4). Yellowish conidial conidiomata formed across the colony after 14 days of incubation at 25 °C. The conidia were cylindrical to clavate, smooth-walled, hyaline, aseptate, and rounded at both ends (few one end rounded to acute), measuring 10.6 to 17.3 × 5.0 to 6.8 μm (average 14.1 ± 1.2 × 5.8 ± 0.3 μm). The appressoria were globose, puce, with an entire or lobed margin, and 7.5 to 17.5 × 5.6 to 13.2 μm (average 10.5 ± 1.7 × 8.9 ± 0.9 μm) in size (Table 2). Conidiophores and setae formed from a brown stroma. The setae were dark brown, straight to slightly curved, opaque, tip acute, and base cylindrical (Figure 4). The mycelial growth rate was 12.7 ± 0.2 mm per day on PDA at 25 °C (Table 2).

Figure 4.

Morphological features of Colletotrichum brevisporum isolate NFUCB-6 from Cyclocarya paliurus: (A) front and back views of a 6-d-old PDA culture; (B) conidia; (C,D) conidiomata produced on PDA and SNA, respectively; (E) conidiophores; (F) appressoria; (G) setae; (H,I) section view of acervuli produced on a Cyclocarya paliurus leaf. Scale bars: (B,E–G) =10 μm; (C) =200 μm; (D) =500 μm; (H,I) =20 μm.

Table 2.

Phenotypic and morphological characteristics of representative isolates from Cyclocarya paliurus of the seven Colletotrichum species identified in the present study.

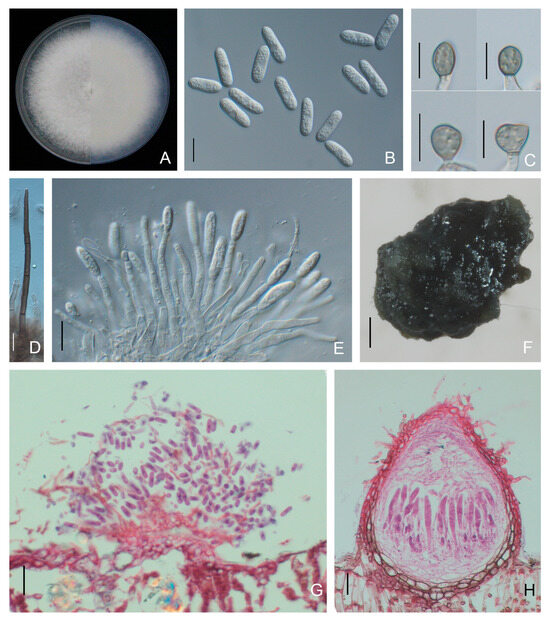

Colonies of C. fructicola isolates were olive-grey with whitish edges on PDA, and the average growth rate was 14.4 ± 0.2 mm/day. Conidia were produced as brick-red masses and were hyaline, smooth-walled, aseptate, cylindrical with rounded ends, and 10.3 to 22.5 × 4.4 to 7.9 μm (average 13.5 ± 1.8 × 5.8 ± 0.5 μm) in size. Conidiophores were hyaline, simple to 2-septate, and unbranched. Appressoria were greyish brown to black and formed singularly, with ovoid to slightly irregular outlines, measuring 6.5 to 16.0 × 4.5 to 9.1 μm (average 9.5 ± 1.6 × 7.0 ± 0.9 μm). Asci were clavate, fasciculate and 8-spored. Ascospores were smooth-walled, hyaline, aseptate, partly guttulate, curved fusoid with rounded ends and 12.3 to 23.2 × 3.8 to 6.5 μm (average 17.7 ± 1.7 × 5.0 ± 0.6 μm) in size (Figure 5, Table 2).

Figure 5.

Morphological features of Colletotrichum fructicola isolate NFUCF-62 from Cyclocarya paliurus. (A) Front and back views of a 6-d-old PDA culture; (B) conidia; (C) conidiophores; (D) appressoria; (E) ascomata; (F,G) asci; (H,I) ascospores; (J,K) section view of acervuli and ascomata produced on a Cyclocarya paliurus leaf, respectively. Scale bars: (B–D,F–I) =10 μm; (E,J,K) =20 μm.

Colonies of C. gloeosporioides s. s. on PDA were white to off-white with dense aerial mycelia and edges, and the average growth rate was 12.6 ± 0.5 mm/day. Conidia were cylindrical, straight with a few slightly curved, aseptate, hyaline, rounded at both ends, and were 13.1 to 22.7 × 4.5 to 6.3 μm (average 15.9 ± 1.1 × 5.5 ± 0.4 μm) in size. Brown-colored appressoria were ovoid to slightly irregular, with an entire margin measuring 7.2 to 12.5 × 6.0 to 10.3 μm (average 9.6 ± 1.0 × 7.2 ± 0.9 μm) (Figure 6, Table 2). Conidiophores and setae formed from a dark brown stroma. Setae were dark brown, straight to slightly curved, and opaque, with acute tip and cylindrical base (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Morphological features of Colletotrichum gloeosporioides sensu stricto isolate NFUCl-5 from Cyclocarya paliurus. (A) Front and back views of a 6-d-old PDA culture; (B) conidia; (C) appressoria; (D) setae; (E) conidiophores; (F) conidiomata produced on SNA; (G,H) section view of acervuli and ascomata produced on a Cyclocarya paliurus leaf, respectively. Scale bars: (B–E) =10 μm; (F) =200 μm; (G,H) =20 μm.

The C. godetiae isolates exhibited dense and white colonies on PDA, and the average growth rate was 8.4 ± 0.2 mm/day. Conidia were produced in orange conidiomata and were aseptate, hyaline and fusiform, with one end rounded and one end rounded to acute, measuring 12.6 to 20.7 × 3.8 to 6.8 μm (average 15.9 ± 1.3 × 5.1 ± 0.4 μm). Conidiophores and setae formed from a brown stroma. Setae were dark brown, straight or curved, and opaque, with acute tip and cylindrical base. Sexual morphs were not observed (Figure 7). Appressoria were greyish brown to black, ovoid to globose, with entire or lobed margins, and 7.6 to 13.2 × 4.9 to 8.7 μm (average 9.5 ± 1.0 × 6.4 ± 0.7 μm) in size (Figure 7, Table 2).

Figure 7.

Morphological features of Colletotrichum godetiae isolate NFUCo-1 from Cyclocarya paliurus. (A) Front and back views of a 6-day-old PDA culture; (B) conidia; (C,D) conidiomata produced on SNA and PDA, respectively; (E) conidiophores; (F) setae; (G) appressoria; (H) section view of acervuli produced on a Cyclocarya paliurus leaf. Scale bars: (B,E–G) =10 μm; (C) =200 μm; (D) =500 μm; (H) =20 μm.

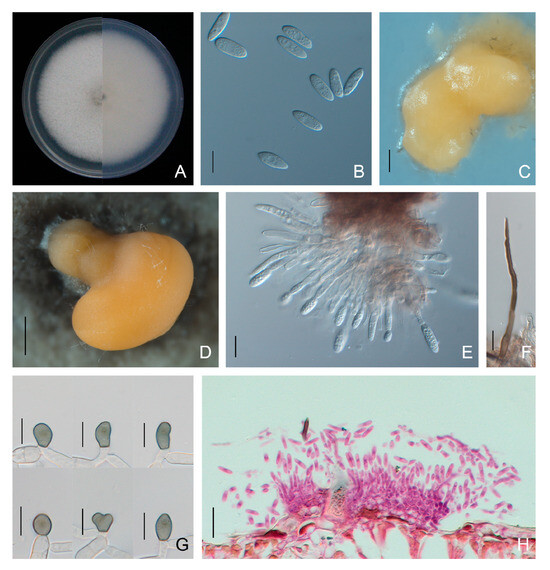

Colletotrichum nymphaeae colonies on PDA were dense, olive-grey with a white margin after 6 days of incubation, and had similar morphological features to those of C. godetiae. Conidia were fusiform with one end rounded and one end rounded to acute, measuring 11.1 to 18.0 × 4.0 to 6.9 μm (average 14.5 ± 1.9 × 5.5 ± 0.9 μm). Appressoria were greyish brown to black, ovoid, with smooth margins, and 7.0 to 11.9 × 5.0 to 8.9 μm (average 9.1 ± 1.3 × 7.0 ± 1.1 μm) in size (Figure 8, Table 2). The average growth rate of Colletotrichum nymphaeae isolates on PDA was 9.8 ± 0.2 mm per day (Table 2).

Figure 8.

Morphological features of Colletotrichum nymphaeae isolate NFUCN-2 from Cyclocarya paliurus. (A) Front and back views of a 6-d-old PDA culture; (B,C) conidiomata produced on PDA and SNA, respectively; (D) conidia; (E) appressoria; (F) conidiophores; (G) sectional view of acervuli produced on a Cyclocarya paliurus leaf. Scale bars: (B,C) =200 μm; (D–F) =10 μm; (G) =20 μm.

Colonies of C. plurivorum isolates on PDA were olive-grey with white margins, and the average growth rate was 11.1 ± 0.1 mm/day. Conidia were aseptate, hyaline, cylindrical with rounded ends, and 12.1 to 20.2 × 5.0 to 7.7 μm (average 14.9 ± 1.6 × 6.2 ± 0.6 μm) in size. Conidiophores were hyaline, unbranched, and formed from a brown stroma. Setae were dark brown, straight and opaque, with acute tip and cylindrical base (Figure 9). Appressoria were globose to ovoid, puce, with an entire or lobed margin, and 8.6 to 20.5 × 6.4 to 12.5 μm (average 12.4 ± 2.2 × 9.2 ± 1.2 μm) in size. Ascomata were semi-immersed in agar medium, subglobose to pyriform, and dark brown. Asci were clavate or fasciculate, and eight-spored (Figure 9). Ascospores were hyaline, smooth-walled, aseptate, fusiform to curved fusoid, and rounded at both ends, measuring 13.6 to 23.0 × 5.0 to 9.3 μm (average 18.0 ± 1.6 × 7.0 ± 0.8 μm) (Figure 9, Table 2).

Figure 9.

Morphological features of Colletotrichum plurivorum isolate NFUCP-13 from Cyclocarya paliurus. (A) Front and back view of 6-day-old PDA culture; (B) ascomata produced on SNA; (C) conidia; (D) appressoria; (E) conidiophores; (F) setae; (G) ascospores; (H) asci; (I) section view of ascomata produced on Cyclocarya paliurus leaf. Scale bars: (B) =500 μm; (C–H) =10 μm; (I) =20 μm.

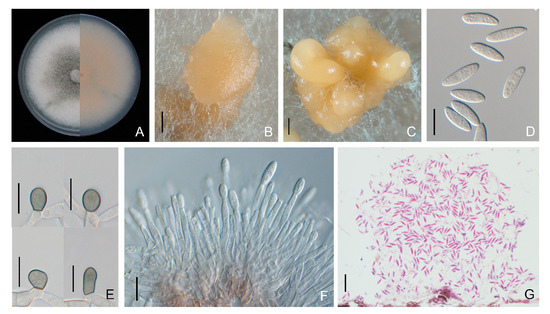

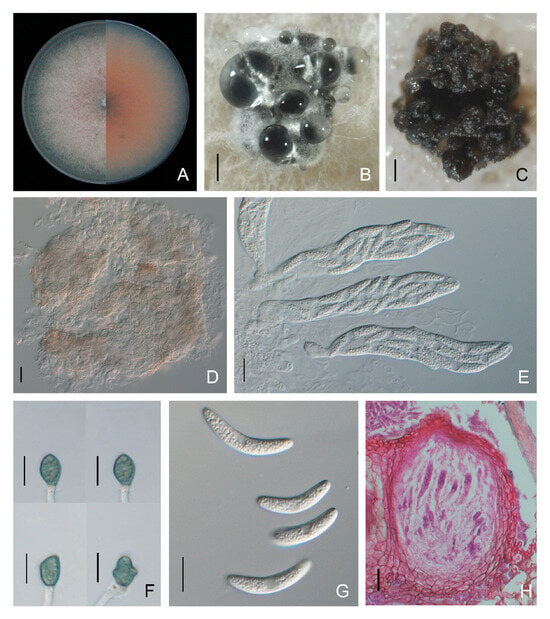

Colletotrichum sojae colonies on PDA were light orange-red with whitish aerial mycelia and edges, and the average growth rate was 14.7 ± 0.7 mm per day. Asexual morphs were not observed. Ascomata formed on PDA or SNA after two weeks of inoculation, which were subglobose to pyriform, dark brown, ostiolate, and semi-immersed in the agar medium. Asci were clavate or fasciculate and eight-spored (Figure 10). Ascospores were hyaline, aseptate, smooth-walled and curved fusoid with rounded ends, had granular content and measured 13.2 to 32.1 × 3.0 to 6.8 μm (average 24.4 ± 4.4 × 5.0 ± 0.7 μm). Appressoria were puce, ovoid with an entire or lobed margin and 7.2 to 18.0 × 5.7 to 9.4 μm (average 11.1 ± 1.7 × 7.4 ± 0.7 μm) in size (Figure 10, Table 2).

Figure 10.

Morphological features of Colletotrichum sojae isolate NFUCS-10 from Cyclocarya paliurus. (A) Front and back views of a 6-day-old PDA culture; (B,C) ascomata produced on PDA and SNA, respectively; (D) ascomata; (E) asci; (F) appressoria; (G) ascospores; (H) section view of ascomata produced on a Cyclocarya paliurus leaf. Scale bars: (B) =500 μm; (C) =200 μm; (D,H) =20 μm; (E–G) =10 μm.

3.4. Pathogenicity Tests

The data from the pathogenicity tests are given in Table 3. Representative isolates of all seven Colletotrichum species produced typical symptoms of anthracnose on detached C. paliurus leaves, while the corresponding mock controls remained asymptomatic up to 10 dpi. Inoculation with C. fructicola, C. godetiae, C. gloeosporioides s. s., C. nymphaeae and C. sojae isolates led to the development of anthracnose symptoms on leaves through both wounding and nonwounding methods, whereas C. brevisporum and C. plurivorum ones exhibited weaker virulence and were only capable of infecting wounded leaves.

Table 3.

Results of pathogenicity tests of Colletotrichum isolates artificially inoculated on Cyclocarya paliurus.

All isolates of Colletotrichum species showed a higher incidence and severity of disease on wounded leaves than on nonwounded leaves. Moreover, the isolates of the different species displayed distinct levels of aggressiveness. Among them, isolates of C. fructicola exhibited the highest aggressiveness on both detached leaves and intact plants. At 3 dpi, symptoms began to appear around the inoculation site, and then the lesion expanded rapidly. Dark-brown necrotic lesions were observed with typical Colletotrichum acervuli or ascomata after 15 dpi. The average lesion diameters (mean ± SE) were 25.3 ± 0.8 mm, 20.1 ± 1.3 mm and 9.4 ± 1.0 mm on wounded detached leaves, nonwounded detached leaves and intact plants, respectively. The virulence of C. gloeosporioides s. s., C. godetiae and C. nymphaeae isolates was weaker than that of C. fructicola isolates. In contrast, C. brevisporum, C. plurivorum and C. sojae were weakly aggressive to C. paliurus leaves, and at 15 dpi, the symptoms on nonwounded leaves and intact plants did not markedly spread or remained asymptomatic. There was no significant difference in pathogenicity between different strains of the same Colletotrichum species. Re-isolation from infected leaves was successful and confirmed by morphological and molecular identification, thus fulfilling Koch’s postulates.

4. Discussion

Anthracnose is the most prevalent foliar disease in all major C. paliurus-growing areas in southern China, causing enormous pecuniary losses under humid conditions and disease-favorable temperatures. Unfortunately, the species diversity of C. paliurus anthracnose pathogens in southern China remains largely unclear. In the present study, we collected and characterized 331 Colletotrichum isolates from eight C. paliurus planting provinces and identified seven species belonging to the Gloeosporioides, Acutatum, Magnum and Orchidearum complexes, demonstrating that diverse Colletotrichum species complexes can infect C. paliurus.

The ascomycete genus Colletotrichum includes important phytopathogens that cause anthracnose worldwide. Among them, three species belonging to the Gloeosporioides complex have been identified to induce C. paliurus anthracnose in China [10], whereas C. fructicola and C. gloeosporioides s. s. were identified in this study. The composition of Colletotrichum spp. causing C. paliurus anthracnose has been reported only in Jiangsu Province, where the Gloeosporioides complex was consistently reported as the most dominant instigator. Nevertheless, based on extensively collected samples, we found that the Gloeosporioides complex was not the only species complex causing C. paliurus anthracnose.

Taxonomic studies of Colletotrichum species have focused on disentangling intraspecific or specific taxa, traditionally according to phenotypic differences, mainly characteristics of cultural morphology, growth rate and microstructure morphs [34,35]. However, environmental factors and cultural conditions have major impacts on the stability of phenotypic traits. Furthermore, the morphological characteristics of Colletotrichum spp. within the species complex largely overlap; thus, phenotypical criteria are not adequate for a precise identification [34].

In terms of molecular characterization, for several fungi, the ITS region has been proposed as a universal DNA marker [36]; however, previous studies have proven that Colletotrichum species cannot be efficiently distinguished by ITS alone. Consequently, other loci such as GADPH, GS and ApMat must be considered. Hyde et al. [37] suggested that the GADPH gene is the most variable marker across multiple Colletotrichum species complexes. Several studies have recommended the use of the ApMat marker for the delimitation of cryptic species within the Gloeosporioides complex, yet Tovar-Pedraza [38] reported that C. jiangxiense and C. kahawae in the Gloeosporioides complex cannot be distinguished from each other by only ApMat sequence data, and their identification requires GS- and ApMat-concatenated phylogenetic analysis. In the present work, phylogenetic analyses of eight loci (ITS, GAPDH, ACT, CHS-1, TUB, CAL, GS and ApMat) in the Gloeosporioides complex and six loci (ITS, GAPDH, ACT, CHS-1, TUB, CAL and HIS3) in the other species complexes revealed that 43 representative isolates belonged to seven known Colletotrichum species, including C. brevisporum, C. fructicola, C. gloeosporioides s. s., C. godetiae, C. nymphaeae, C. plurivorum and C. sojae (Figure 2 and Figure 3). Furthermore, the morphological groups identified based on colony features, asexual or sexual morphs, and typical Colletotrichum conidial masses or ascomata that developed on inoculated leaves were entirely consistent with the results of the molecular data.

Pathogenicity tests revealed that all seven Colletotrichum species were pathogenic to wounding detached leaves of C. paliurus. When the foliar tissue was wounded, the incidence and severity of disease increased significantly. These results suggest that wounds may play an important role for pathogen penetration into the host. On average, species within the Gloeosporioides and Acutatum complexes produced larger lesions than those in the Magnum and Orchidearum complexes, which may be one of the notable factors contributing to the prevalence of the Gloeosporioides complex. Moreover, different Colletotrichum species had various degrees of aggressiveness on C. paliurus leaves. C. fructicola in the Gloeosporioides complex was the most aggressive species. Thus, a species-specific diagnosis is highly important for the prediction of relative aggressiveness; the species complex alone is not a sufficient indicator of pathogenicity or disease risk.

A previous study demonstrated that C. fructicola was the most common pathogen causing C. paliurus anthracnose in Jiangsu Province, China [10]. Similarly, in the present work, the dominant causal agent associated with C. paliurus anthracnose was C. fructicola on the basis of the highest isolation rate and aggressiveness levels. C. fructicola was originally isolated from coffee berries in Thailand [39]. It has been subsequently reported that C. fructicola could cause serious anthracnose infections in Australia, Brazil, China, Malaysia and the USA [18,40,41,42,43]. C. fructicola has been found on a broad range of host plants, such as fruit trees and economically important crops, including apple (Malus spp.), Citrus spp., mango (Mangifera indica), peach (Prunus persica), pear (Pyrus spp.), strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa) and tea (Camellia sinensis), possibly due to its parasitic and endophytic lifestyle [18,40,44,45,46,47,48,49].

5. Conclusions

This study presents the first large-scale survey of Colletotrichum species associated with C. paliurus anthracnose in southern China. It offers novel insights into the disease’s aetiology, including the first report of C. brevisporum, C. godetiae, C. nymphaeae, C. plurivorum and C. sojae associated with C. paliurus anthracnose. Considering the occurrence of several species involved in C. paliurus anthracnose, future research should take into account that the effective control of this disease may depend on the individual characteristics of each Colletotrichum species and their distribution in the C. paliurus planting areas. Furthermore, in view of the dominance of C. fructicola in major planting regions and its greater aggressiveness than other species, more epidemiological studies are needed to elucidate this pathological system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.-M.C.; methodology, X.-R.Z.; software, X.-R.Z.; validation, M.-J.Z.; formal analysis, M.-J.Z.; investigation, X.-R.Z.; resources, F.-M.C.; data curation, M.-J.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, X.-R.Z.; writing—review and editing, X.-R.Z. and M.-J.Z.; visualization, X.-R.Z. and M.-J.Z.; supervision, F.-M.C.; project administration, F.-M.C.; funding acquisition, F.-M.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Postgraduate Research and Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province, grant number KYCX20_0875 and KYCX23_1222.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article and Appendix A.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Isolates of Colletotrichum from leaves of wheel wingnut and various hosts examined in this study.

Table A1.

Isolates of Colletotrichum from leaves of wheel wingnut and various hosts examined in this study.

| Species | Culture/Isolate a | Host | Location | GenBank Accession Number b | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | GAPDH | CHS | ACT | TUB | CAL | GS | ApMat | ||||

| Colletotrichum aenigma | ICMP 18608 | Persea americana | Israel | JX010244 | JX010044 | JX009774 | JX009443 | JX010389 | JX009683 | JX010078 | KM360143 |

| C. aeschynomenes | ICMP 17673 | Aeschynomene virginica | USA | JX010176 | JX009930 | JX009799 | JX009483 | JX010392 | JX009721 | JX010081 | KM360145 |

| C. alatae | CBS 304.67 | Dioscorea alata | India | JX010190 | JX009990 | JX009837 | JX009471 | JX010383 | JX009738 | JX010065 | KC888932 |

| C. alienum | ICMP 12071 | Malus domestica | New Zealand | JX010251 | JX010028 | JX009882 | JX009572 | JX010411 | JX009654 | JX010101 | KM360144 |

| C. aotearoa | ICMP 18537 | Coprosma sp. | New Zealand | JX010205 | JX010005 | JX009853 | JX009564 | JX010420 | JX009611 | JX010113 | KC888930 |

| C. asianum | CBS 130418 | Coffea arabica | Thailand | FJ972612 | JX010053 | JX009867 | JX009584 | JX010406 | FJ917506 | JX010096 | FR718814 |

| C. camelliae | CGMCC 3.14925 | Camellia sinensis | China | KJ955081 | KJ954782 | MZ799255 | KJ954363 | KJ955230 | KJ954634 | KJ954932 | KJ954497 |

| C. chrysophilum | CMM 4268 | Musa sp. | Brazil | KX094252 | KX094183 | KX094083 | KX093982 | KX094285 | KX094063 | KX094204 | KX094325 |

| C. clidemiae | ICMP 18658 | Clidemia hirta | USA | JX010265 | JX009989 | JX009877 | JX009537 | JX010438 | JX009645 | JX010129 | KC888929 |

| C. conoides | CGMCC 3.17615 | Chili pepper | China | KP890168 | KP890162 | KP890156 | KP890144 | KP890174 | KP890150 | - | - |

| C. cordylinicola | ICMP 18579 | Cordyline fruticosa | Thailand | JX010226 | JX009975 | JX009864 | HM470235 | JX010440 | HM470238 | JX010122 | JQ899274 |

| C. fructicola | CBS 130416 | Coffea arabica | Thailand | JX010165 | JX010033 | JX009866 | FJ907426 | JX010405 | FJ917508 | JX010095 | JQ807838 |

| NFUCF-4 | Cyclocarya paliurus | Sichuan, China | OR056200 | OR069484 | OR073817 | OR096449 | OR073835 | OR096522 | OR098645 | OR105821 | |

| NFUCF-5 | Cy. paliurus | Guizhou, China | OR056201 | OR069485 | OR073818 | OR096450 | OR073836 | OR096523 | OR098646 | OR105822 | |

| NFUCF-12 | Cy. paliurus | Sichuan, China | OR056202 | OR069486 | OR073819 | OR096451 | OR073837 | OR096524 | OR098647 | OR105823 | |

| NFUCF-15 c | Cy. paliurus | Guangxi, China | OR056203 | OR069487 | OR073820 | OR096452 | OR073838 | OR096525 | OR098648 | OR105824 | |

| NFUCF-21 | Cy. paliurus | Fujian, China | OR056204 | OR069488 | OR073821 | OR096453 | OR073839 | OR096526 | OR098649 | OR105825 | |

| NFUCF-28 | Cy. paliurus | Hubei, Chna | OR056205 | OR069489 | OR073822 | OR096454 | OR073840 | OR096527 | OR098650 | OR105826 | |

| NFUCF-35 | Cy. paliurus | Jiangxi, China | OR056206 | OR069490 | OR073823 | OR096455 | OR073841 | OR096528 | OR098651 | OR105827 | |

| NFUCF-41 | Cy. paliurus | Guangxi, China | OR056207 | OR069491 | OR073824 | OR096456 | OR073842 | OR096529 | OR098652 | OR105828 | |

| NFUCF-43 | Cy. paliurus | Fujian, China | OR056208 | OR069492 | OR073825 | OR096457 | OR073843 | OR096530 | OR098653 | OR105829 | |

| NFUCF-51 | Cy. paliurus | Jiangxi, China | OR056209 | OR069493 | OR073826 | OR096458 | OR073844 | OR096531 | OR098654 | OR105830 | |

| NFUCF-59 | Cy. paliurus | Guizhou, China | OR056210 | OR069494 | OR073827 | OR096459 | OR073845 | OR096532 | OR098655 | OR105831 | |

| NFUCF-62 c | Cy. paliurus | Hunan, China | OR056211 | OR069495 | OR073828 | OR096460 | OR073846 | OR096533 | OR098656 | OR105832 | |

| NFUCF-74 | Cy. paliurus | Guangxi, China | OR056212 | OR069496 | OR073829 | OR096461 | OR073847 | OR096534 | OR098657 | OR105833 | |

| NFUCF-95 | Cy. paliurus | Zhejiang, China | OR056213 | OR069497 | OR073830 | OR096462 | OR073848 | OR096535 | OR098658 | OR105834 | |

| NFUCF-118 | Cy. paliurus | Guizhou, China | OR056214 | OR069498 | OR073831 | OR096463 | OR073849 | OR096536 | OR098659 | OR105835 | |

| NFUCF-154 | Cy. paliurus | Hunan, China | OR056215 | OR069499 | OR073832 | OR096464 | OR073850 | OR096537 | OR098660 | OR105836 | |

| NFUCF-179 | Cy. paliurus | Jiangxi, China | OR056216 | OR069500 | OR073833 | OR096465 | OR073851 | OR096538 | OR098661 | OR105837 | |

| NFUCF-214 c | Cy. paliurus | Zhejiang, China | OR056217 | OR069501 | OR073834 | OR096466 | OR073852 | OR096539 | OR098662 | OR105838 | |

| C. gloeosporioides | CBS 112999 | Citrus sinensis | Italy | JX010152 | JX010056 | JX009818 | JX009531 | JX010445 | JX009731 | JX010085 | JQ807843 |

| NFUCl-3 | Cy. paliurus | Guangxi, China | OR064046 | OR069502 | OR073853 | OR096419 | OR096467 | OR096540 | OR098663 | OR105839 | |

| NFUCl-5 c | Cy. paliurus | Jiangxi, China | OR064047 | OR069503 | OR073854 | OR096420 | OR096468 | OR096541 | OR098664 | OR105840 | |

| NFUCl-11 c | Cy. paliurus | Guizhou, China | OR064048 | OR069504 | OR073855 | OR096421 | OR096469 | OR096542 | OR098665 | OR105841 | |

| NFUCl-28 | Cy. paliurus | Guizhou, China | OR064049 | OR069505 | OR073856 | OR096422 | OR096470 | OR096543 | OR098666 | OR105842 | |

| NFUCl-34 c | Cy. paliurus | Hunan, China | OR064050 | OR069506 | OR073857 | OR096423 | OR096471 | OR096544 | OR098667 | OR105843 | |

| C. grevilleae | CBS 132879 | Grevillea sp. | Italy | KC297078 | KC297010 | KC296987 | KC296941 | KC297102 | KC296963 | KC297033 | - |

| C. hebeiense | MFLUCC13–0726 | Vitis vinifera | China | KF156863 | KF377495 | KF289008 | KF377532 | KF288975 | - | - | - |

| C. henanense | CGMCC 3.17354 | Ca. sinensis | China | KJ955109 | KJ954810 | MZ799256 | KM023257 | KJ955257 | KJ954662 | KJ954960 | KJ954524 |

| C. horii | ICMP 10492 | Diospyros kaki | Japan | GQ329690 | GQ329681 | JX009752 | JX009438 | JX010450 | JX009604 | JX010137 | JQ807840 |

| C. jiangxiense | CGMCC 3.17361 | Ca. sinensis | China | KJ955149 | KJ954850 | MZ799257 | KJ954427 | OK236389 | KJ954701 | KJ955000 | KJ954561 |

| C. kahawae subsp. ciggaro | ICMP 18539 | Olea europaea | Australia | JX010230 | JX009966 | JX009800 | JX009523 | JX010434 | JX009635 | JX010132 | - |

| C. musae | CBS 116870 | Musa sp. | USA | JX010146 | JX010050 | JX009896 | JX009433 | HQ596280 | JX009742 | JX010103 | KC888926 |

| C. nupharicola | CBS 470.96 | Nuphar lutea | USA | JX010187 | JX009972 | JX009835 | JX009437 | JX010398 | JX009663 | JX010088 | JX145319 |

| C. perseae | CBS 141365 | Avocado | Israel | KX620308 | KX620242 | MZ799260 | KX620145 | KX620341 | KX620206 | KX620275 | KX620177 |

| C. proteae | CBS 132882 | Protea sp. | South Africa | KC297079 | KC297009 | KC296986 | KC296940 | KC297101 | KC296960 | KC297032 | - |

| C. psidii | CBS 145.29 | Psidium sp. | Italy | JX010219 | JX009967 | JX009901 | JX009515 | JX010443 | JX009743 | JX010133 | KC888931 |

| C. queenslandicum | ICMP 1778 | Carica papaya | Australia | JX010276 | JX009934 | JX009899 | JX009447 | JX010414 | JX009691 | JX010104 | KC888928 |

| C. salsolae | ICMP 19051 | Salsola tragus | Hungary | JX010242 | JX009916 | JX009863 | JX009562 | JX010403 | JX009696 | JX010093 | KC888925 |

| C. siamense | CBS 130417 | Coffea arabica | Thailand | JX010171 | JX009924 | JX009865 | FJ907423 | JX010404 | FJ917505 | JX010094 | JQ899289 |

| C. tainanense | CBS 143666 | Capsicum annuum | China | MH728818 | MH728823 | MH805845 | MH781475 | MH846558 | - | MH748259 | MH728836 |

| C. theobromicola | CBS 124945 | Theobroma cacao | Panama | JX010294 | JX010006 | JX009869 | JX009444 | JX010447 | JX009591 | JX010139 | KC790726 |

| C. ti | ICMP 4832 | Cordyline sp. | New Zealand | JX010269 | JX009952 | JX009898 | JX009520 | JX010442 | JX009649 | JX010123 | KM360146 |

| C. tropicale | CBS 124949 | Theobroma cacao | Panama | JX010264 | JX010007 | JX009870 | JX009489 | JX010407 | JX009719 | JX010097 | KC790728 |

| C. wuxiense | CGMCC 3.17894 | Camellia sinensis | China | KU251591 | KU252045 | KU251939 | KU251672 | KU252200 | KU251833 | KU252101 | KU251722 |

| C. xanthorrhoeae | CBS 127831 | Xanthorrhoea preissii | Australia | JX010261 | JX009927 | JX009823 | JX009478 | JX010448 | JX009653 | JX010138 | KC790689 |

| C. yulongense | CFCC 50818 | Vaccinium dunalianum | China | MH751507 | MK108986 | MH793605 | MH777394 | MK108987 | MH793604 | MK108988 | - |

| Monilochaetes infuscans | CBS 869.96 | Ipomoea batatas | South Africa | JQ005780 | JX546612 | JQ005801 | JQ005843 | JQ005864 | - | - | - |

a Culture numbers in bold type represent ex-type or other authentic specimens. CBS 869.96 (Monilochaetes infuscans) was added as an outgroup. b Sequences in italics were generated in this study. “-”indicates missing data. c Isolates used for macroscopic and microscopic characterization and virulence tests.

Table A2.

Strains of Colletotrichum excluded from the C. gloeosporioides species complex. Details are provided about clade, host and location, and GenBank accessions of the sequences generated.

Table A2.

Strains of Colletotrichum excluded from the C. gloeosporioides species complex. Details are provided about clade, host and location, and GenBank accessions of the sequences generated.

| Species | Culture/Isolate a | Clade | Host | Location | GenBank Accession Number b | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | GAPDH | CHS-1 | HIS3 | ACT | TUB2 | |||||

| C. abscissum | COAD 1877 | Acutatum | Citrus sinensis cv. Pera | Brazil | KP843126 | KP843129 | KP843132 | KP843138 | KP843141 | KP843135 |

| C. acerbum | CBS 128530 | Acutatum | Malus domestica | New Zealand | JQ948459 | JQ948790 | JQ949120 | JQ949450 | JQ949780 | JQ950110 |

| C. acutatum | CBS 112996 | Acutatum | Carica papaya | Australia | JQ005776 | JQ948677 | JQ005797 | JQ005818 | JQ005839 | JQ005860 |

| C. australe | CBS 116478 | Acutatum | Trachycarpus fortunei | South Africa | JQ948455 | JQ948786 | JQ949116 | JQ949446 | JQ949776 | JQ950106 |

| C. brevisporum | BCC 38876 | Magnum | Neoregalia sp. | Thailand | JN050238 | JN050227 | MZ799287 | MZ673841 | JN050216 | JN050244 |

| NFUCB-2 c | Magnum | Cyclocarya paliurus | Hunan, China | OR064061 | OR069517 | OR073868 | OR096507 | OR096434 | OR096482 | |

| NFUCB-6 c | Magnum | Cy. Paliurus | Hunan, China | OR064062 | OR069518 | OR073869 | OR096508 | OR096435 | OR096483 | |

| NFUCB-9 | Magnum | Cy. Paliurus | Hunan, China | OR064063 | OR069519 | OR073870 | OR096509 | OR096436 | OR096484 | |

| NFUCB-11 | Magnum | Cy. Paliurus | Hunan, China | OR064064 | OR069520 | OR073871 | OR096510 | OR096437 | OR096485 | |

| NFUCB-12 c | Magnum | Cy. Paliurus | Guizhou, China | OR064065 | OR069521 | OR073872 | OR096511 | OR096438 | OR096486 | |

| C. brisbanense | CBS 292.67 | Acutatum | Capsicum annuum | Australia | JQ948291 | JQ948621 | JQ948952 | JQ949282 | JQ949612 | JQ949942 |

| C. cacao | CBS 119297 | Magnum | Theobroma cacao | Costa Rica | MG600772 | MG600832 | MG600878 | MG600916 | MG600976 | MG601039 |

| C. cairnsense | BRIP 63642 | Acutatum | Capsicum annuum | Australia | KU923672 | KU923704 | KU923710 | KU923722 | KU923716 | KU923688 |

| C. cattleyicola | CBS 170.49 | Orchidearum | Cattleya sp. | Belgium | MG600758 | MG600819 | MG600866 | MG600905 | MG600963 | MG601025 |

| C. chrysanthemi | IMI 364540 | Acutatum | Chrysanthemum coronarium | China | JQ948273 | JQ948603 | JQ948934 | JQ949264 | JQ949594 | JQ949924 |

| C. cliviicola | CBS 125375 | Orchidearum | Clivia miniata | China | MG600733 | MG600795 | MG600850 | MG600892 | MG600939 | MG601000 |

| C. cosmi | CBS 853.73 | Acutatum | Cosmos sp. | Netherlands | JQ948274 | JQ948604 | JQ948935 | JQ949265 | JQ949595 | JQ949925 |

| C. costaricense | CBS 330.75 | Acutatum | Coffea arabica, cv. Typica | Costa Rica | JQ948180 | JQ948510 | JQ948841 | JQ949171 | JQ949501 | JQ949831 |

| C. cuscutae | IMI 304802 | Acutatum | Cuscuta sp. | Dominica | JQ948195 | JQ948525 | JQ948856 | JQ949186 | JQ949516 | JQ949846 |

| C. eriobotryae | GLMC 1935 | Acutatum | Eriobotrya japonica | China | MF772487 | MF795423 | MN191653 | MN191658 | MN191648 | MF795428 |

| C. fioriniae | CBS 128517 | Acutatum | Fiorinia externa | USA | JQ948292 | JQ948622 | JQ948953 | JQ949283 | JQ949613 | JQ949943 |

| C. godetiae | CBS 133.44 | Acutatum | Clarkia hybrida cv. Kelvon Glory | Denmark | JQ948402 | JQ948733 | JQ949063 | JQ949393 | JQ949723 | JQ950053 |

| NFUCo-1 c | Acutatum | Cy. paliurus | Guizhou, China | OR064051 | OR069507 | OR073858 | OR096497 | OR096424 | OR096472 | |

| NFUCo-4 c | Acutatum | Cy. paliurus | Jiangxi, China | OR064052 | OR069508 | OR073859 | OR096498 | OR096425 | OR096473 | |

| NFUCo-5 c | Acutatum | Cy. paliurus | Hunan, China | OR064053 | OR069509 | OR073860 | OR096499 | OR096426 | OR096474 | |

| NFUCo-8 | Acutatum | Cy. paliurus | Hunan, China | OR064054 | OR069510 | OR073861 | OR096500 | OR096427 | OR096475 | |

| NFUCo-11 | Acutatum | Cy. paliurus | Hunan, China | OR064055 | OR069511 | OR073862 | OR096501 | OR096428 | OR096476 | |

| C. guajavae | IMI 350839 | Acutatum | Psidium guajava | India | JQ948270 | JQ948600 | JQ948931 | JQ949261 | JQ949591 | JQ949921 |

| C. indonesiense | CBS 127551 | Acutatum | Eucalyptus sp. | Indonesia | JQ948288 | JQ948618 | JQ948949 | JQ949279 | JQ949609 | JQ949939 |

| C. javanense | CBS 144963 | Acutatum | Capsicum annuum | Indonesia | MH846576 | MH846572 | MH846573 | MH846571 | MH846575 | MH846574 |

| C. johnstonii | CBS 128532 | Acutatum | Solanum lycopersicum | New Zealand | JQ948444 | JQ948775 | JQ949105 | JQ949435 | JQ949765 | JQ950095 |

| C. kinghornii | CBS 198.35 | Acutatum | Phormium sp. | UK | JQ948454 | JQ948785 | JQ949115 | JQ949445 | JQ949775 | JQ950105 |

| C. laticiphilum | CBS 112989 | Acutatum | Hevea brasiliensis | India | JQ948289 | JQ948619 | JQ948950 | JQ949280 | JQ949610 | JQ949940 |

| C. limetticola | CBS 114.14 | Acutatum | Citrus aurantifolia | USA, Florida | JQ948193 | JQ948523 | JQ948854 | JQ949184 | JQ949514 | JQ949844 |

| C. lobatum | IMI 79736 | Magnum | Piper catalpaefolium | Trinidad | MG600768 | MG600828 | MG600874 | MG600912 | MG600972 | MG601035 |

| C. lupini | CBS 109225 | Acutatum | Lupinus albus | Ukraine | JQ948155 | JQ948485 | JQ948816 | JQ949146 | JQ949476 | JQ949806 |

| C. magnum | CBS 519.97 | Magnum | Citrullus lanatus | USA | MG600769 | MG600829 | MG600875 | MG600913 | MG600973 | MG601036 |

| C. melonis | CBS 159.84 | Acutatum | Cucumis melo | Brazil | JQ948194 | JQ948524 | JQ948855 | JQ949185 | JQ949515 | JQ949845 |

| C. merremiae | CBS 124955 | Magnum | Merremia umbellata | Panama | MG600765 | MG600825 | MG600872 | MG600910 | MG600969 | MG601032 |

| C. monsterae | LC13871 | Orchidearum | Monstera deliciosa | China | MZ595897 | MZ664121 | MZ799351 | MZ673917 | MZ664195 | MZ674015 |

| C. musicola | CBS 132885 | Orchidearum | Musa sp. | Mexico | MG600736 | MG600798 | MG600853 | MG600895 | MG600942 | MG601003 |

| C. nymphaeae | CBS 515.78 | Acutatum | Nymphaea alba | Netherlands | JQ948197 | JQ948527 | JQ948858 | JQ949188 | JQ949518 | JQ949848 |

| NFUCN-2 c | Acutatum | Cy. paliurus | Guangxi, China | OR064071 | OR069527 | OR073878 | OR096517 | OR096444 | OR096492 | |

| NFUCN-5 c | Acutatum | Cy. paliurus | Hunan, China | OR064072 | OR069528 | OR073879 | OR096518 | OR096445 | OR096493 | |

| NFUCN-7 | Acutatum | Cy. paliurus | Hunan, China | OR064073 | OR069529 | OR073880 | OR096519 | OR096446 | OR096494 | |

| NFUCN-11 c | Acutatum | Cy. paliurus | Guizhou, China | OR064074 | OR069530 | OR073881 | OR096520 | OR096447 | OR096495 | |

| NFUCN-14 | Acutatum | Cy. paliurus | Jiangxi, China | OR064075 | OR069531 | OR073882 | OR096521 | OR096448 | OR096496 | |

| C. orchidearum | CBS 135131 | Orchidearum | Dendrobium nobile | Netherlands | MG600738 | MG600800 | MG600855 | MG600897 | MG600944 | MG601005 |

| C. panamense | CBS 125386 | Magnum | Merremia umbellata | Panama | MG600766 | MG600826 | MG600873 | MG600911 | MG600970 | MG601033 |

| C. paxtonii | IMI 165753 | Acutatum | Musa sp. | Saint Lucia | JQ948285 | JQ948615 | JQ948946 | JQ949276 | JQ949606 | JQ949936 |

| C. phormii | CBS 118194 | Acutatum | Phormium sp. | Germany | JQ948446 | JQ948777 | JQ949107 | JQ949437 | JQ949767 | JQ950097 |

| C. piperis | IMI 71397 | Orchidearum | Piper nigrum | Malaysia | MG600760 | MG600820 | MG600867 | MG600906 | MG600964 | MG601027 |

| C. plurivorum | CBS 125474 | Orchidearum | Coffea sp. | Vietnam | MG600718 | MG600781 | MG600841 | MG600887 | MG600925 | MG600985 |

| NFUCP-3 c | Orchidearum | Cy. paliurus | Guizhou, China | OR064066 | OR069522 | OR073873 | OR096512 | OR096439 | OR096487 | |

| NFUCP-5 c | Orchidearum | Cy. paliurus | Hunan, China | OR064067 | OR069523 | OR073874 | OR096513 | OR096440 | OR096488 | |

| NFUCP-7 | Orchidearum | Cy. paliurus | Hunan, China | OR064068 | OR069524 | OR073875 | OR096514 | OR096441 | OR096489 | |

| NFUCP-8 | Orchidearum | Cy. paliurus | Hunan, China | OR064069 | OR069525 | OR073876 | OR096515 | OR096442 | OR096490 | |

| NFUCP-13 c | Orchidearum | Cy. paliurus | Jiangxi, China | OR064070 | OR069526 | OR073877 | OR096516 | OR096443 | OR096491 | |

| C. pyricola | CBS 128531 | Acutatum | Pyrus communis | New Zealand | JQ948445 | JQ948776 | JQ949106 | JQ949436 | JQ949766 | JQ950096 |

| C. reniforme | LC8230 | Orchidearum | Smilax cocculoides | China | MZ595847 | MZ664110 | MZ799290 | MZ673867 | MZ664145 | MZ673968 |

| C. rhombiforme | CBS 129953 | Acutatum | Olea europaea | Portugal | JQ948457 | JQ948788 | JQ949118 | JQ949448 | JQ949778 | JQ950108 |

| C. salicis | CBS 607.94 | Acutatum | Salix sp. | Netherlands | JQ948460 | JQ948791 | JQ949121 | JQ949451 | JQ949781 | JQ950111 |

| C. schimae | LC13880 | Acutatum | Schima sp. | China | MZ595885 | MZ664105 | MZ799347 | MZ673905 | MZ664183 | MZ674003 |

| C. scovillei | CBS 126529 | Acutatum | Capsicum sp. | Indonesia | JQ948267 | JQ948597 | JQ948928 | JQ949258 | JQ949588 | JQ949918 |

| C. simmondsii | CBS 122122 | Acutatum | Carica papaya | Australia | JQ948276 | JQ948606 | JQ948937 | JQ949267 | JQ949597 | JQ949927 |

| C. sloanei | IMI 364297 | Acutatum | Theobroma cacao | Malaysia | JQ948287 | JQ948617 | JQ948948 | JQ949278 | JQ949608 | JQ949938 |

| C. sojae | ATCC 62257 | Orchidearum | Glycine max | USA | MG600749 | MG600810 | MG600860 | MG600899 | MG600954 | MG601016 |

| NFUCS-1 c | Orchidearum | Cy. paliurus | Jiangxi, China | OR064056 | OR069512 | OR073863 | OR096502 | OR096429 | OR096477 | |

| NFUCS-3 c | Orchidearum | Cy. paliurus | Hunan, China | OR064057 | OR069513 | OR073864 | OR096503 | OR096430 | OR096478 | |

| NFUCS-6 | Orchidearum | Cy. paliurus | Hunan, China | OR064058 | OR069514 | OR073865 | OR096504 | OR096431 | OR096479 | |

| NFUCS-10 c | Orchidearum | Cy. paliurus | Guizhou, China | OR064059 | OR069515 | OR073866 | OR096505 | OR096432 | OR096480 | |

| NFUCS-15 | Orchidearum | Cy. paliurus | Fujian, China | OR064060 | OR069516 | OR073867 | OR096506 | OR096433 | OR096481 | |

| C. tamarilloi | CBS 129814 | Acutatum | Solanum betaceum | Colombia | JQ948184 | JQ948514 | JQ948845 | JQ949175 | JQ949505 | JQ949835 |

| C. vittalense | CBS 181.82 | Orchidearum | Theobroma cacao | India | MG600734 | MG600796 | MG600851 | MG600893 | MG600940 | MG601001 |

| C. walleri | CBS 125472 | Acutatum | Coffea sp. | Vietnam | JQ948275 | JQ948605 | JQ948936 | JQ949266 | JQ949596 | JQ949926 |

| Monilochaetes infuscans | CBS 869.96 | outgroup | Ipomoea batatas | South Africa | JQ005780 | JX546612 | JQ005801 | JQ005822 | JQ005843 | JQ005864 |

a Culture numbers in bold type represent ex-type or other authentic specimens. CBS 869.96 (Monilochaetes infuscans) was added as an outgroup. b Sequences in italics were generated in this study. c Isolates used for phenotypic analysis and virulence tests.

Table A3.

Location information and incidence rate statistics of the investigated area.

Table A3.

Location information and incidence rate statistics of the investigated area.

| Province | County/Location | Leaf Samples | Latitude (N) | Longitude (E) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fujian | Xiapu | 4 | 27°03′08″ | 119°56′33″ |

| Jianyang | 6 | 27°33′08″ | 117°47′03″ | |

| Guangxi | Longsheng | 7 | 26°01′13″ | 109°55′08″ |

| Guizhou | Lipin | 12 | 26°06′50″ | 109°11′08″ |

| Hubei | Yidu | 6 | 30°26′04″ | 111°19′54″ |

| Sui | 6 | 32°11′43″ | 113°16′11″ | |

| Hunan | Jianghua Yao nationality | 13 | 24°54′01″ | 112°06′43″ |

| Jiangxi | Jinggangshan | 6 | 26°42′03″ | 114°17′47″ |

| Shangrao | 7 | 28°49′54″ | 118°11′07″ | |

| Sichuan | Xuyong | 5 | 28°09′11″ | 105°23′54″ |

| Zhejiang | Lanxi | 11 | 29°08′50″ | 119°23′28″ |

References

- Zhao, W.; Tang, D.; Yuan, E.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Shen, B.; Chen, J.; Yin, Z. Inducement and cultivation of novel red Cyclocarya paliurus callus and its unique morphological and metabolic characteristics. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 147, 30–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Xiong, L.; Chen, H.; Liu, X.; Wang, N.; Ouyang, K.; Wang, W. Antihyperlipidemic and hepatoprotective activities of polysaccharide fraction from Cyclocarya paliurus in high-fat emulsion-induced hyperlipidaemic mice. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 183, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Hu, J.; Nie, Q.; Chang, X.; Fang, Q.; Xie, J.; Li, H.; Nie, S.P. Hypoglycemic mechanism of polysaccharide from Cyclocarya paliurus leaves in type 2 diabetic rats by gut microbiota and host metabolism alteration. Sci. China Life Sci. 2020, 64, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.; Peng, Y.; Zhu, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, L.; Kong, F.; Wang, J.; Yu, D. The phytochemicals and health benefits of Cyclocarya paliurus (Batalin) Iljinskaja. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1158158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, X.; Hu, W.B.; Yang, Z.W.; Chen, H.; Wang, N.; Liu, X.; Wang, W. Enzymolysis-ultrasonic assisted extraction of flavanoid from Cyclocarya paliurus (Batal) Iljinskaja: HPLC profile, antimicrobial and antioxidant activity. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 130, 615–626. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, W.C.; Luo, H.R.; Yuan, E.; Sakah, J.; Yang, Q.Y.; Xiao, W.L.; Zheng, Y.T.; Liu, M.F. Triterpene constituents from the fruits of Cyclocarya paliurus and their anti-HIV-1 IIIB activity. Nat. Prod. Res. 2022, 37, 1787–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, M.; Quek, S.Y.; Shang, X.; Fang, S. Geographical variations of triterpenoid contents in Cyclocarya paliurus leaves and their inhibitory effects on HeLa cells. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 162, 113314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Fu, X.; Shang, X.; Yang, W.; Fang, S. Natural population structure and genetic differentiation for heterodicogamous plant: Cyclocarya paliurus (Batal.) Iljinskaja (Juglandaceae). Tree Genet. Genomes 2017, 13, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.R.; Liu, C.L.; Zhang, M.J.; Shang, X.L.; Fang, S.Z.; Chen, F.M. First report of leaf blight of Cyclocarya paliurus caused by Nigrospora sphaerica in China. Crop Prot. 2020, 140, 105453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.R.; Zhang, M.J.; Shang, X.L.; Fang, S.Z.; Chen, F.M. Etiology of Cyclocarya paliurus Anthracnose in Jiangsu Province, China. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 11, 613499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Xu, X.; Cheng, J.; Zheng, L.; Huang, J.; Li, D.W. Identification and Characterization of Colletotrichum Species Associated with Anthracnose Disease of Camellia oleifera in China. Plant Dis. 2020, 104, 474–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyde, K.; Cai, L.; Cannon, P.; Crouch, J.A.; Crous, P.; Damm, U.; Goodwin, P.H.; Chen, H.; Johnston, P.; Jones, E.; et al. Colletotrichum—Names in current use. Fungal Divers. 2009, 39, 147–182. [Google Scholar]

- Weir, B.S.; Johnston, P.R.; Damm, U. The Colletotrichum gloeosporioides species complex. Stud. Mycol. 2012, 73, 115–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Ma, Z.Y.; Hou, L.; Diao, Y.; Wu, W.; Damm, U.; Song, S.; Cai, L. Updating species diversity of Colletotrichum, with a phylogenomic overview. Stud. Mycol. 2022, 101, 1–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damm, U.; Sato, T.; Alizadeh, A.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Crous, P.W. The Colletotrichum dracaenophilum, C. magnum and C. orchidearum species complexes. Stud. Mycol. 2019, 92, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damm, U.; Cannon, P.F.; Woudenberg, J.H.C.; Crous, P.W. The Colletotrichum acutatum species complex. Stud. Mycol. 2012, 73, 37–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Weir, B.; Damm, U.; Crous, P.; Wang, Y.; Liu, B.; Wang, M.; Zhang, M.; Cai, L. Unravelling Colletotrichum species associated with Camellia: Employing ApMat and GS loci to resolve species in the C. gloeosporioides complex. Persoonia 2016, 35, 63–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, M.; Crous, P.W.; Bai, Q.; Zhang, P.F.; Xiang, J.; Guo, Y.S.; Zhao, F.F.; Yang, M.M.; Hong, N.; Xu, W.X.; et al. Colletotrichum species associated with anthracnose of Pyrus spp. in China. Persoonia 2019, 42, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Hyde, K.; Taylor, P.; Weir, B.; Waller, J.; Abang, M.; Zhang, J.Z.; Yang, Y.L.; Phoulivong, S.; Liu, Z.Y. A polyphasic approach for studying Colletotrichum. Fungal Divers. 2009, 39, 183–204. [Google Scholar]

- Gardes, M.; Bruns, T. ITS primers with enhanced specificity for basidiomycetes—Application to the identification of mycorrhizae and rusts. Mol. Ecol. 1993, 2, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, J.; Innis, M.; Gelfand, D.; Sninsky, J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Guerber, J.C.; Liu, B.; Correll, J.C.; Johnston, P.R. Characterization of diversity in Colletotrichum acutatum sensu lato by sequence analysis of two gene introns, mtDNA and intron RFLPs, and mating compatibility. Mycologia 2003, 95, 872–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbone, I.; Kohn, L.M. A method for designing primer sets for speciation studies in filamentous ascomycetes. Mycologia 1999, 91, 553–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crous, P.W.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Risede, J.M.; Simoneau, P.; Hywel-Jones, N.L. Calonectria species and their Cylindrocladium anamorphs: Species with sphaeropedunculate vesicles. Stud. Mycol. 2004, 50, 415–430. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell, K.; Cigelnik, E. Two divergent intragenomic rDNA ITS2 types within a monophyletic lineage of the fungus Fusarium are nonorthologous. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 1997, 7, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, N.L.; Donaldson, G.C. Development of primer sets designed for use with the PCR to amplify conserved genes from filamentous ascomycetes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995, 61, 1323–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, K.; Nirenberg, H.I.; Aoki, T.; Cigelnik, E. A Multigene phylogeny of the Gibberella fujikuroi species complex: Detection of additional phylogenetically distinct species. Mycoscience 2000, 41, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.N.; Talhinhas, P.; Varzea, V.; Cai, L.; Paulo, O.S.; Batista, D. Application of the Apn2/MAT locus to improve the systematics of the Colletotrichum gloeosporioides complex: An example from coffee (Coffea spp.) hosts. Mycologia 2012, 104, 396–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, G.; Lohman, D.J.; Meier, R. SequenceMatrix: Concatenation software for the fast assembly of multi-gene datasets with character set and codon information. Cladistics 2011, 27, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronquist, F.; Teslenko, M.; Mark, P.; Ayres, D.; Darling, A.; Höhna, S.; Larget, B.; Liu, L.; Suchard, M.; Huelsenbeck, J. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian Phylogenetic Inference and Model Choice Across a Large Model Space. Syst. Biol. 2012, 61, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.R.; Zhang, M.J.; Qiao, Y.H.; Li, R.; Alkan, N.; Chen, J.Y.; Chen, F.M. Cyclocarya paliurus Reprograms the Flavonoid Biosynthesis Pathway Against Colletotrichum fructicola. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 933484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L.F.; Li, X.X.; Gao, Y.Y.; Li, B.X.; Mu, W.; Liu, F. Characterization and Fungicide Sensitivity of Colletotrichum spp. from Different Hosts in Shandong, China. Plant Dis. 2019, 103, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, S.; Katan, T.; Shabi, E. Characterization of Colletotrichum Species Responsible for Anthracnose Diseases of Various Fruits. Plant Dis. 1998, 82, 596–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, S.; Horowitz, S.; Sharon, A. Pathogenic and Nonpathogenic Lifestyles in Colletotrichum acutatum from Strawberry and other Plants. Phytopathology 2001, 91, 986–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoch, C.; Seifert, K.; Huhndorf, S.M.; Robert, V.; Spouge, J.; Levesque, C.; Chen, W.; Janzen, D.; Consortium, A. Nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region as a universal DNA barcode marker for Fungi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 6241–6246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyde, K.D.; Nilsson, R.H.; Alias, S.A.; Ariyawansa, H.A.; Blair, J.E.; Cai, L.; Cock, A.W.A.M.; Dissanayake, A.J.; Glockling, S.L.; Goonasekara, I.D.; et al. One stop shop: Backbones trees for important phytopathogenic genera: I. Fungal Divers. 2014, 67, 21–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovar-Pedraza, J.M.; Mora-Aguilera, J.A.; Nava-Díaz, C.; Lima, N.B.; Michereff, S.J.; Sandoval-Islas, J.S.; Câmara, M.P.S.; Téliz-Ortiz, D.; Leyva-Mir, S.G. Distribution and Pathogenicity of Colletotrichum Species Associated with Mango Anthracnose in Mexico. Plant Dis. 2020, 104, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prihastuti, H.; McKenzie, E.; Hyde, K.; Cai, L.; Hu, M.; Hyde, E. Characterization of Colletotrichum species associated with coffee berries in northern Thailand. Fungal Divers. 2009, 39, 89–109. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; de Silva, D.D.; Moslemi, A.; Edwards, J.; Ades, P.K.; Crous, P.W.; Taylor, P.W.J. Colletotrichum Species Causing Anthracnose of Citrus in Australia. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, M.; Edwards, S.; Inocencio, H.; Machado, F.; Nuckles, E.; Farman, M.; Gauthier, N.; Vaillancourt, L. Diversity and Cross-Infection Potential of Colletotrichum Causing Fruit Rots in Mixed-Fruit Orchards in Kentucky. Plant Dis. 2020, 105, 1115–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, R.R.; Peres, N.A.; May, D.M.L.L. Colletotrichum acutatum and C. gloeosporioides Species Complexes Associated with Apple in Brazil. Plant Dis. 2019, 103, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noor, N.M.; Zakaria, L. Identification and characterization of Colletotrichum spp. associated with chili anthracnose in peninsular Malaysia. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2018, 151, 961–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Zhou, Y.; Tan, G.; Zhang, L. Identification and characterization of Colletotrichum species associated with Camellia sinensis anthracnose in Anhui province, China. Plant Dis. 2020, 105, 2649–2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, Y.; Li, Y.; Tang, G.; Zheng, X.; Khaskheli, M.I.; Gong, G. Identification of Colletotrichum Species Associated with Anthracnose Disease of Strawberry in Sichuan Province, China. Plant Dis. 2021, 105, 3025–3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Fu, D.; Wang, W.; Gleason, M.L.; Zhang, R.; Liang, X.; Sun, G. Diversity of Colletotrichum Species Causing Apple Bitter Rot and Glomerella Leaf Spot in China. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Q.; Schnabel, G.; Chaisiri, C.; Yin, L.; Yin, W.; Luo, C. Colletotrichum Species Associated with Peaches in China. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, J.; Zhao, G.; Li, Q.; Solangi, G.S.; Tang, L.; Guo, T.; Huang, S.; Hsiang, T. Identification and Characterization of Colletotrichum Species Associated with Mango Anthracnose in Guangxi, China. Plant Dis. 2018, 102, 1283–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, Y.; Jin, G.; Li, D.; Wu, S.; Zhu, L. First report of Colletotrichum fructicola causing leaf spots on Liriodendron chinense × tulipifera in China. Forest Pathol. 2022, 52, e12779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).