Abstract

China announced its first policy framework for the construction of a protected areas system centered on national parks in 2019. It is increasingly recognized that the intentions of local community residents to engage in environmentally responsible behaviors are essential to achieving biodiversity goals in area-based conservation. Using an extended theory of planned behavior that incorporates the emotional factors of “Awe” and “place attachment,” this research tested hypotheses and constructed a theoretical model regarding the environmentally responsible behavioral intentions of community residents within and outside Potatso National Park, a pilot park in the new Chinese protected area system. A quantitative questionnaire survey of residents yielded 503 valid responses, and structural equation modeling was used to test the theoretical hypotheses. The results show that Awe has a significantly positive effect on environmentally responsible behavioral intentions. It also has a significantly positive effect on Place Attachment and subjective norms, which also strengthen environmentally responsible behavioral intentions. In addition, Place Attachment was found to be an important mediating factor for the influence of Awe on environmentally responsible behavioral intentions. According to the general model, both rational and emotional factors drive the behavioral intentions of local residents. Moreover, the findings reveal that the regulating effect of Place Attachment plays a greater role among those whose livelihoods are more dependent on the natural environment, while subjective norms play a greater role among those whose livelihoods are less dependent on the natural environment. The results provide a useful theoretical basis and practical reference for the use of rational and emotional factors to drive environmentally responsible behaviors among residents in and surrounding national parks, and for the promotion of the role of protected areas in nature preservation and community development.

1. Introduction

There is an urgent need to increase our actions to conserve biodiversity and natural resources. Increasingly, scholars and practitioners recognize the value of area-based conservation. However, this form of conservation continues to face certain challenges [1]. Dudley et al. (2018) [2] suggest that effective area-based biodiversity conservation must address human rights and social safeguarding issues, while Maxwell et al. (2020) [3] argue that it must include meaningful collaboration with indigenous peoples, community groups, and private initiatives. This paper seeks to expand our understanding of the role of local residents in area-based conservation, and focuses on the relationship between Awe, Place Attachment, and environmental behavioral intentions among local residents of Potatso National Park in China.

By 2017, China had established nine categories of nature-protected areas on 11,800 sites, covering approximately 18% of the country’s land area. In order to resolve the issue of overlapping protected area management regimes, the Chinese government, in 2019, announced its first policy framework for the development of a protected areas system centered on national parks [4]. National park management increasingly plays a role in limiting local community livelihood practices that may be ecologically damaging. Such management impacts local economies and resource utilization patterns, leading to conflict, and may not, therefore, result in successful nature preservation [5,6,7].

Given current national park development trends in China, land use and natural resource rights inevitably involve local communities. As Cheng et al. (2020) [8] point out, community residents and other stakeholders are key elements in the sustainable development of national parks, and their environmentally responsible behaviors influence the effectiveness of protection programs [9]. However, Wang (2019) [4] argues that China’s top-down approach to conservation risks undermining the rights of local communities and threatens the goals that national parks aim to achieve. This research, therefore, sought to develop a deeper understanding of the Awe and Place Attachment that local residents feel towards their national park home.

Research by Pan et al. (2019) [10] into the cognitive attitudes of national park residents and visitors found that, while visitors emphasize the function of nature protection, residents believe that greater attention should be paid to the sustainable use of natural resources. While both groups are concerned about environmental protection, community residents have multi-generational livelihoods and cultural connections to place, they have more extensive and intensive contact with the environment, and their production and lifestyles have a greater impact on the environment [11]. Therefore, understanding the emotional impact of the environment on local residents is of great practical significance in guiding their environmentally responsible behaviors.

The factors and mechanisms that affect environmentally responsible behaviors are worthy of some consideration. While there have been many such studies elsewhere [12,13,14,15], such research is limited in China. Some Chinese research has explored environmentally responsible behavior from the perspective of environmental satisfaction, Place Attachment, and nostalgia [16,17,18,19]; although, such research has centered on the perspectives of visitors, with relatively little attention paid to local residents.

China comprises many ethnic groups, and factors such as religious beliefs, history, culture, and relationships with nature have a profound impact on ecological consciousness and behavior [20,21,22]. However, exploring the environmentally responsible behaviors of national park residents is particularly rare [23]. The purpose of this research was to explore environmentally responsible behavioral intentions through an extended theory of planned behavior (TPB) incorporating Awe and Place Attachment.

The findings of a quantitative survey of residents of Potatso National Park in Shangri-La, Yunnan Province, extend our existing knowledge of environmentally responsible behavioral intentions. They provide a theoretical basis and practical reference for the scientific protection and rational utilization of natural resources, and for the sustainable development of communities within and outside national parks in China’s protected areas system.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theory of Planned Behavior

The TPB, developed by psychologist Icek Ajzen (1991) [24], purports that intentions to perform behaviors can be predicted with high accuracy based on attitudes toward that behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. Behavioral intention is the most direct factor determining an individual’s actual behavior [25]. Understanding individual intentions can help to predict behaviors, making research into intentions very important in understanding behaviors that impact the environment. TPB has been used in a variety of fields [9], including in the study of healthy eating [26], engaging in dishonest actions [27], smoking cessation [28], and Internet purchasing behavior [29]. Increasingly, the TPB is used in the interpretation and prediction of environmentally responsible behaviors at the individual level.

This research defines environmentally responsible behavioral intentions as the degree to which individuals are willing to actively participate in solving or preventing environmental problems. According to Ajzen (1991) [24], behavioral intentions are mediated by behavioral attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. Behavioral attitudes are the positive or negative evaluations one makes when assessing environmentally responsible behavior. Subjective norms are the social mores and pressures felt by community residents when deciding whether to engage in environmentally responsible behavior. Minton et al. (2018) [30], for example, found that national norms and a country’s level of pragmatism influence individual consumption practices. Perceived behavioral control is one’s perceived ability to perform a behavior, which can affect such behaviors as the use of green energy [31] or choosing green transport [32].

These three aspects of TPB are mutually influencing. Deng (2012) [33] and Zhou et al. (2014) [34] have shown that subjective norms can effectively drive behavioral attitudes and intentions, and, in general, the more positive an individual’s attitude toward environmentally responsible behavior, the stronger their behavioral intentions (Hong and Zhang, 2016) [23]. Meanwhile, Zhao et al. (2013) [19] found that perceived behavioral control is an effective predictor of behavioral intentions. Research by Deng (2012) [33] has found that perceived behavioral control positively affects behavioral attitudes and intentions.

2.2. Extended TPB Model

Yuriev et al. (2020) [35] argue that scholars have tended to overlook mediating variables when predicting environmentally responsible behaviors, and claim that additional variables increase the predictive power of the theory. Ajzen (1991) [24] recognized that the TPB model was imperfect, and argued for the inclusion of other factors in the study of individual behavior in certain situations.

Empirical research has found that the explanatory power of emotional factors is significantly higher than that of cognitive factors, thereby turning attention away from traditional rational motivation analysis to emotional motivation analysis. Emotion plays an important role in the expansion of the TPB model, and can effectively enhance its explanatory power [36].

Indeed, in their study of neighborhood curbside recycling, Nigbur et al. [37] (2010) used an extended TPB model that included self-identity, personal norms, neighborhood identification, and social norms, while de Leeuw et al.’s (2015) [38] study of the pro-environmental behaviors of high school students included empathy and parental behavior. This study incorporated “Awe” and “Place Attachment” as two additional factors in an extended TPB.

2.2.1. Place Attachment

Place Attachment has long been a significant research theme in environmental psychology, and its emotional connectedness is mainly reflected in the interactions between people and places. Williams and Roggenbuck (1989) [39] have suggested a theoretical framework of place identity (the emotional attachment between people and places) and place dependence (the functional attachment between people and places). Empirical research by Zhou et al. (2014) [34], Tang et al. (2018) [40], and Zhao et al. (2018) [41] confirms that Place Attachment has a positive impact on behavioral attitudes and environmentally responsible behaviors.

2.2.2. Awe

Awe is a complex mixture of emotions, including reverence, respect, and wonder. It arises when one is confronted with something vast, expansive, and beyond one’s current understanding [42]. In a complex environment, Awe arises when an individual perceives the vastness of that environment. Keltner and Haidt (2003) [43] suggest that Awe can be triggered by social factors, such as religious belief, tangible factors, such as a landscape or piece of music, and cognitive factors, such as knowledge or perception. Qi et al.’s (2018) [44] research on religious mountain scenic spots found that Awe has a significant impact on environmentally responsible behavior. Awe can be triggered by both nature-based and human-made phenomena [45]. Research by both Qi et al. (2018) [44] and Hu et al. (2019) [46] found that Awe has a significant positive impact on environmentally responsible behavior, while Hu et al. (2019) [46] found that Awe can directly and indirectly influence green consumer behavior.

2.3. Social Connectedness and Nature Connectedness

Individuals feel different levels of “social connectedness” or “nature connectedness” with the world around them [46]. Environmentally responsible behaviors are influenced by both forms of connectedness, intersecting with concerns regarding sustainable development and the protection and sustainable utilization of natural resources. Social connectedness can directly impact perceptions of and relationships with nature. For instance, in Buddhist societies, temples are often built in beautiful and secluded environments [47], and mountains and other physical features are imbued with religious and cultural meaning, thereby inducing social Awe. Moreover, the subjective norms inherent in social connectedness exert social pressures when deciding whether to engage in environmentally responsible behavior.

Nature connectedness refers to the relationship between the individual and the natural environment. It reflects an individual’s cognition of being integrated with nature, of attachment to nature, of the ability to appreciate the beauty of nature, and a willingness to live with nature. When an individual’s emotional and cognitive intimacy with nature increases, so too does their willingness and behavioral intention to think from a natural perspective [48]. Empirical research shows that Awe generated by tangible triggers, such as the natural environment, can significantly predict pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors. For instance, Gosling and Williams (2010) [49] found that farmers with higher nature connectedness exhibit a stronger willingness to protect local vegetation, while Lu et al. (2017) [50] found that natural connectedness plays a mediating role on the influence of Awe on pro-environmental behavior. Place Attachment is an emotional connectedness produced by the interactions between peoples and places, and includes functional attachment (place dependence) and emotional attachment (place identity).

3. Methodology

3.1. Potatso National Park

Before 2015, there were nine categories of protected areas in China, including nature reserves, forest parks, wetland parks, geoparks, and others, but there was no national park category. In 2015, the National Development and Reform Commission, together with 13 ministries and commissions of China, jointly issued The Plan for Establishing National Park System Pilot [51]. This officially launched the pilot project of China’s National Park System [52]. The National Park System incorporates 12 Chinese provinces, covering an area of nearly 0.22 million km2, and accounting for 3% of the country’s land area [53]. In June 2019, China issued the Guideline to Establish the System of Protected Areas with National Parks as a Major Component by the Chinese government to improve the conservation efficiency of PAs. It marks a leap in the establishment of China’s new protected area system, which re-divided the previous nine categories into three categories of protected area.

Potatso National Park is located in Shangri-La, Diqing Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Yunnan Province of China, which was one of 10 pilot national parks. The park covers an area of 602.1 km2 and is rich in landscape diversity, biodiversity, and cultural diversity [54]. The park is located in UNESCO World Natural Heritage Site “Three Parallel Rivers” and has 84% forest coverage, with many plants including meconopsis, primrose, spruce, and fir, and animals including wild boar, leopard, musk deer, and numerous bird species. Bitahai Lake and Shuduhu Lake are key features of the park, and are called the eyes of Shangri-La. There are fish with cracks on their bellies, locally called “Liefuyu”, living in the limpid water of Shuduhu Lake [54]. All the important physical features of the park are connected by hiking trails and shuttle bus, offering visitors the opportunity to experience the natural environment at close quarters.

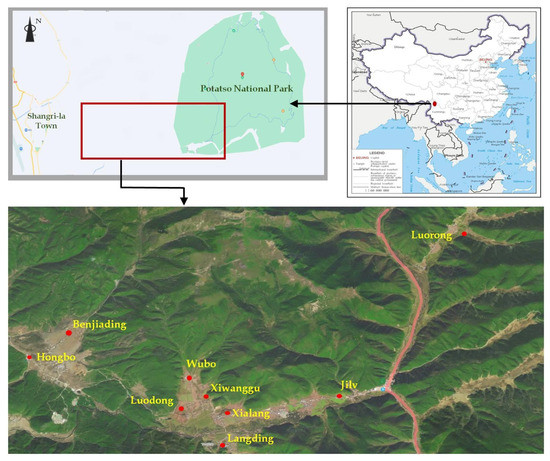

There are 3700 residents living in nine villages within and outside the park (see Figure 1). Luorong Village is located within the park, and the other eight villages are located outside of the park. There is no restrictions difference between the people living within and outside the park. Most are Tibetan; although, there are smaller numbers of Yi, Han, and Naxi people. For the majority of resident Tibetan Buddhists, the surrounding landscape is imbued with spiritual meaning [55]. Local religious beliefs, history and culture, Awe of nature, local attachment, and other socio-cultural factors have a deep impact on the ecological consciousness and behavior of residents [20,47].

Figure 1.

Location of research site.

Traditional livelihoods and lifestyles in the past were mostly semi-agricultural and semi-pastoral [54], and included cattle and sheep husbandry, and collecting and selling wild fungi [55,56]. The tourism industry gradually began to develop around 2000 with the residents of Luorong Village providing a holding horses service, selling barbecue, and renting Tibetan clothes and taking photos for visitors. Such disorderly business activities seriously damaged the local ecological environment and were also restricted. When the national park system pilot was implemented, ecotourism service projects at the Shuduhu Lake ecological recreation area and the Shudugang River ecological recreation area were licensed to local ecotourism companies to improve facilities; residents had the opportunity to participate in sanitation, transportation, and interpretation services and to provide ecological, agriculture, and animal husbandry products [54]. Meanwhile, each household within and outside the park received an annual bonus of RMB 20,000 [57]. This eco-compensation aimed to improve livelihoods while encouraging environmental protection. In a word, only 2.3% of Potatso National Park is utilized, effectively protecting 97.7%, which produces ecological, social, and economic benefits [55].

3.2. Theoretical Model

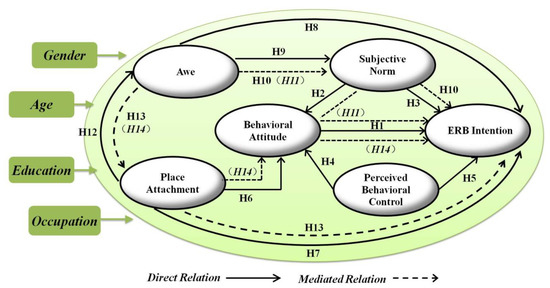

Based on the investigation of Potatso National Park communities and the religious belief of Tibetans, we propose 14 hypotheses. These hypotheses introduce two emotional factors, namely, Awe and Place Attachment, into the TPB framework. Moreover, we have constructed a model of the influencing mechanism of community residents’ environmentally responsible behavioral intentions based on these hypotheses and the extended TPB model (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Hypothetical model. Hx, Hypothesis x; ERB, Environmentally responsible behavior.

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Behavioral attitude has a significant positive effect on environmentally responsible behavioral intentions.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Subjective norm has a significant positive impact on behavioral attitude.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Subjective norm has a significant positive impact on environmentally responsible behavioral intention.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Perceived behavioral control has a significant positive effect on behavioral attitude.

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Perceived behavioral control has a significant positive effect on environmentally responsible behavioral intention.

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

Place Attachment has a significant positive impact on behavioral attitude.

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

Place Attachment has a significant positive impact on environmentally responsible behavioral intention.

Hypothesis 8 (H8).

Awe has a significant positive impact on environmentally responsible behavioral intention.

Hypothesis 9 (H9).

Awe has a significant positive effect on subjective norm.

Hypothesis 10 (H10).

Subjective norm plays a significant positive mediating role between Awe and environmentally responsible behavioral intention.

Hypothesis 11 (H11).

The pathway of “subjective norm → behavioral attitude” plays a significant and long-range mediating role between Awe and environmentally responsible behavioral intention.

Hypothesis 12 (H12).

Awe has a significant positive effect on Place Attachment.

Hypothesis 13 (H13).

Place Attachment has a significant positive effect on the relationship between Awe and environmentally responsible behavioral intentions.

Hypothesis 14 (H14).

The pathway of “Place Attachment → behavioral attitudes” plays a significant and long-range mediating role between Awe and environmentally responsible behavioral intention.

In addition, the demographic factors including gender, age, education, and occupation were employed for adjustment effect analysis of the mediating effect paths to reveal the existence of significant differences.

3.3. Questionnaire Design and Variable Measurement

The questionnaire consisted of three parts: (a) Environmentally Responsible Behavior intention (ERB); (b) five influencing factors including behavioral attitude (BA), Place Attachment (PA), Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC), Subjective Norm (SN), and Awe (AWE); and (c) demographics factors including gender, age, education, occupation, local or permanent residents, number of years resident in the area, nationality, sources of family income, religion, and political affiliation. The scale items were drawn from pre-existing dimensions. Following the translation of some scales from English to Mandarin, the wording of some items was fine-tuned based on the actual research situation.

The questions for six items were designed according the relevant research. Each of the six items used a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly agree, 2 = agree, 3 = neutral, 4 = disagree, and 5 = strongly disagree). Environmentally responsible behavioral intention (ERB) was measured using six questions exploring general behavior(GB) and specific behavior (SB) developed by Vaske and Kobrin (2001) [15], Halpenny (2010) [58], and Cheng et al. (2013) [59]. Behavioral attitude(BA) was measured using three questions of semantic differences from Fielding et al. (2008) [60]. Place Attachment(PA) was measured using nine questions exploring place dependence(PD) and place identity(PI) from Williams et al. (1992) [61] and Tang et al. (2008) [40]. Perceived behavioral control (PBC) was measured using three questions from Williams and Roggenbuck (1989) [39]. Subjective norm (SN) was measured using three questions from Zhou et al. (2014) [34]. Awe (AWE) was measured using six questions exploring natural environment (NE) and religious atmosphere (RA) from Tian et al. (2015) [62] and Tian et al. (2015) [63] (see Table 1 for details).

Table 1.

The definitions and sources of items.

3.4. Data Collection

The survey was conducted between July and August 2019. A convenience sampling method was adopted, and data were collected from questionnaires distributed on-site. The questionnaires were administered by four local residents and three postgraduate students. The postgraduate students received systematic training in questionnaire survey administration at the university and the local residents provided the postgraduate students with logistic and language assistance. The survey was conducted in one village within Potatso National Park, six villages at the entrance to the park, and two relatively distant villages (the farthest village was 13 km from the entrance to the park, see Figure 2). The respondents were required to be over 16 years old. A total of 536 questionnaires were distributed and 33 invalid questionnaires (containing confused or incomplete answers) were eliminated, resulting in 503 valid questionnaires, with an effective response rate of 93.8% (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Potatso National Park survey participants.

3.5. Data Analysis Methods and Procedures

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to test the conceptual model and hypothetical relationships between the dimensions. SEM is a superior large-sample analysis technique commonly used in the social and behavioral sciences. Given that this research comprised multiple elements, such as Awe, Place Attachment, Environmentally Responsible Behavior intention, and so on, SEM allowed for a structural analysis of the relationships between these different components. The structure of the model allowed us to analyze the statistical and causal relationships between variables and factors.

According to Hair Jr. et al. (1998) [64], research generally requires that the ratio of observed variables to sample size be between 1:10 and 1:25. This survey consisted of 30 questions, so a sample size of 300–750 was appropriate. The effective sample size of 503 meets the requirements of SEM analysis.

The internal consistency of the scale and the normality of the data distribution were tested. The coefficients of the internal consistency of the scale were found to be all greater than 0.7, meaning that the scale exhibited good consistency. The kurtosis and skewness of the scale items and the absolute values of skewness were between 0.046 and 2.317 and 0.129 and 1.413, respectively. The absolute values of the kurtosis coefficients of all variable items were less than 8, and the absolute values of the skewness coefficients were all less than 3. Item data coincided with the normal distribution of a single variable, which is suitable for parameter estimation using maximum likelihood estimation. On this basis, Amos 23 software was employed to analyze the data. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) verified the reliability and validity of the measurement model, the overall fit of the structural model, and the research hypotheses [65,66,67].

For the reliability and validity test, the verification of the measurement items revealed that most of the standardized factor loads were less than 0.7, and the p-values were all less than 0.001, demonstrating that the items had good reliability. The study adopted Fornell and Larcker’s (1981) [68] method; i.e., the square root of the AVE of the latent variable and the correlation coefficient of the latent variable were compared to verify the discriminant validity between the latent variables.

For model fitting and hypothesis test, we used X², df, X²/df, root mean square residual (RMR), root mean square error approximation (RMSEA), goodness of fit index (GFI), adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI), normed fit index (NFI), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), comparative fit index (CFI), and other indexes were selected to comprehensively verify the fitting of the structural model [69].

For mediating effect test, the bootstrap procedure was employed to test the mediating effects of the variables. Repeated random sampling of the original data (n = 503) was conducted to collect 5000 bootstrap samples. An approximate sampling distribution was then generated, and the 97.5th and 2.5th percentiles were used to estimate the 95% confidence interval for the mediating effect [70]. If the 95% confidence interval of the indirect effect did not include 0, this would indicate that the mediating effect was statistically significant; otherwise, it would indicate complete mediation.

For mediating effects of demographic factors test, the statistical multi-group structural equations method was selected, and Amos group comparisons were conducted to test for differences in the structural coefficients, covariances, and factor loadings between two different groups [71]. A significant result indicates a difference between the groups, and, therefore, the existence of the interference effect. The Amos manage model [72] was employed for adjustment effect analysis of the direct effect paths, while the heterogeneity test was employed for adjustment effect analysis of the mediating effect paths to reveal the existence of significant differences [73]. The heterogeneity test was employed for adjustment effect analysis of the mediating effect paths to reveal the existence of significant differences between the two groups of educational background and age, respectively, on the analysis of environmentally responsible behavioral intentions. All sample data were divided into “basic education” (junior high school and below) and “secondary and higher education,”(high school/technical secondary school and above), and into “young adults” (aged 44 and below) and “middle-aged and elderly” (aged 45 and above) [72,73].

4. Results

4.1. Reliability and Validity Test

Confirmatory factor analysis and reliability and validity testing of the questionnaire data were conducted. The overall reliability of the questionnaire was 0.884, indicating that the overall questionnaire index exhibited good consistency. The α coefficients of each potential variable were between 0.749 and 0.846 and, therefore, met the requirement for a value of at least 0.7 [65]. The values of composite reliability were between 0.751 and 0.849, which were all greater than 0.6. The average variance extracted (AVE) was between 0.502 and 0.653 and, therefore, all values satisfied the requirement of a value of at least 0.5, indicating that the model exhibited both internal consistency and convergent validity [66,67]. The specific parameters are reported in Table 3.

Table 3.

Results of confirmatory factor analysis.

As shown in Table 4, the square roots of the AVEs of all the dimensions were greater than the coefficient of correlation with other sub-items, demonstrating that the sub-items had good discriminant validity [68].

Table 4.

Dimension discriminant validity test.

4.2. Model Fitting and Hypothesis Test

4.2.1. Modification of Model Fitting

Amos 23 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was used to estimate the parameters of the initial model. Because the X² value is greatly affected by the sample size, the results revealed that the overall fitting index of the model was X² = 820.663 (p < 0.001), df = 388, X²/df = 2.115, RMR = 0.047, RMSEA = 0.047, GFI = 0.900, AGFI = 0.880, NFI = 0.885, TLI = 0.928, and CFI = 0.935. Where the overall fitness index of the model has not yet reached the standard, Bollen and Stine (1992) [69] and Enders (2005) [70] suggest that the overall fitness of the model be revised by using the chi-square value estimated by the Bollen–Stine bootstrap method. The overall fitting index results of the revised model revealed that X² = 548.109 (p < 0.001), df = 388, and X²/df = 1.413, which was between 1 and 3, indicating that the model had good simplicity. Moreover, GFI = 0.923, AGFI = 0.904, NFI = 0.920, TLI = 0.973, and CFI = 0.976 were all greater than the generally accepted value of 0.90, RMR = 0.047 was less than the accepted critical value of 0.05, and RMSEA = 0.003 was less than the accepted critical value of 0.08, indicating that the sample data and the proposed model fit were good (see Table 5 for details).

Table 5.

Comparison of the overall fitness of the model.

4.2.2. Path Analysis and Significance Test

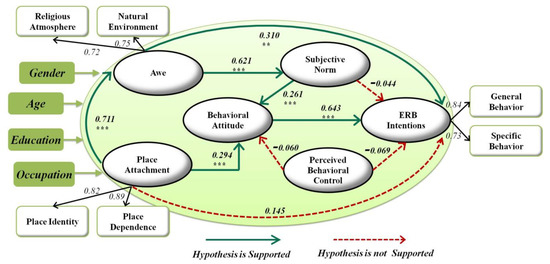

According to Table 6 and Figure 3, most of the hypotheses were supported by the data, and the regression coefficient of determination (R²) of the dependent variable, namely environmentally responsible behavioral intentions, was 0.79, indicating that the independent variables explained 79% of the variance of residents’ environmentally responsible behavioral intentions. Therefore, the good effect of the model was supported.

Table 6.

Path coefficient estimation and hypothesis testing.

Figure 3.

Results of the structural equation model. ***, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.01.

The results of data analysis show that hypotheses H1 and H8 were supported, and behavioral attitudes (path coefficient = 0.628) and Awe (path coefficient = 0.275) had significant positive effects on environmentally responsible behavioral intention. Hypotheses H2 and H6 were supported; subjective norms (path coefficient = 0.188) and Place Attachment (path coefficient = 0.404) have significant positive effects on behavioral attitude. Hypotheses H9 and H12 were supported; Awe has a significant positive effect on both subjective norms (path coefficient = 0.781) and Place Attachment (path coefficient = 0.470).

Hypotheses H3, H5, and H7 were not verified, and subjective norm, perceived behavioral control, and Place Attachment were not found to have significant effects on environmentally responsible behavioral intentions. Moreover, hypothesis H4 was not verified, and no significant effect of perceived behavioral control on behavioral attitudes was found.

4.3. Mediating Effect Test

Hypotheses H10 and H13 were not supported, and hypotheses H11 and H14 were supported. No indirect effects between subjective norms and Place Attachment on Awe and environmentally responsible behavioral intentions were found. In contrast, subjective norms and behavioral attitudes (path coefficient = 0.093) and Place Attachment and behavioral attitudes (path coefficient = 0.119) were found to play long-range and partially positive mediating roles between Awe and environmentally responsible behavioral intentions [71]. In other words, the mediating effect of Awe through subjective norms and Place Attachment must change behavioral attitudes in order to influence environmentally responsible behavioral intentions. The effect of Awe via the mediation of Place Attachment was found to be greater than that via the mediation of subjective norms, but with no significant difference. The path coefficients of the total effects of Awe, subjective norms, and Place Attachment on environmentally responsible behavioral intentions were found to be 0.487, 0.118, and 0.254, respectively (see Table 7 and Table 8).

Table 7.

Analysis of the mediating effect of Awe.

Table 8.

Total effect of other influencing factors.

4.4. Mediating Effects of Demographic Factors

Table 9 summarizes the comparison results of the non-standardized path coefficients of multi-group analysis and the significance of the mediating effects. The results indicate no significant difference between the environmentally responsible behavioral intentions of male and female residents from the perspective of behavioral attitudes, Place Attachment, and Awe. The environmentally responsible behavioral intentions of young adults were found to be positively influenced by behavioral attitudes to a greater extent than those of the middle-aged and elderly. In addition, the positive influence of Place Attachment on the environmentally responsible behavioral intentions of the middle-aged and elderly was found to be significantly greater than that of young adults.

Table 9.

Results of multi-group analyses of demographic factors.

Meanwhile, the environmentally responsible behavioral intentions of residents with basic education were found to be more influenced by Awe, the mediation path of which was “place dependence → behavioral attitudes”, and the influence was significantly greater than that for residents with secondary and higher education.

The effect of Awe on the environmentally responsible behavioral intentions of farmers and herdsmen, along the mediation path of “Place Attachment → behavioral attitudes,” was found to be significantly greater than for others. The environmentally responsible behavioral intentions of non-farmers and non-herdsmen were found to be more affected by behavioral attitudes and subjective norms via the mediation effect of behavioral attitudes, and more affected by Awe via the mediation effect of subjective norms and behavioral attitudes. These results indicate the mediating effect of Place Attachment plays a more significant role among farmers and herdsmen, while the mediating effect of subjective norms plays a more significant role among non-farmers and non-herdsmen. The subjective norms also have a more significant mediating effect on the environmentally responsible behavioral intentions of farmers and herdsmen (as shown in Figure 3).

5. Conclusions

5.1. Preliminary Findings

“Awe” and “Place Attachment” expand and improve the theory of planned behavior in the context of the environmentally responsible behavior of community residents in and around a national park. The empirical research conducted at such a location provides further insight into the influencing factors and mechanisms of the environmentally responsible behavioral intentions of community residents. Hong and Zhang (2016) [23] found that residents pay more attention than visitors to the sustainable use of natural resources, and more intensely consider issues closely related to economic development, employment, access to resources, and family income generation. The research analyses led to the following conclusions.

5.1.1. Awe Has a Significant Positive Impact on Environmentally Responsible Behavioral Intention

Awe directly and positively affects environmentally responsible behavioral intentions via the stimulation of religious belief and the natural environment. Moreover, via the mediation paths of “subjective norm → behavioral attitude” and “Place Attachment → behavioral attitude”, Awe has a significant positive influence on environmentally responsible behavioral intention.

5.1.2. The Mediating Factor of Place Attachment Affects Awe and Environmentally Responsible Behavioral Intention

Awe has significant positive effects on subjective norm and Place Attachment, and plays a long-range and partially positive mediating role through the respective mediating paths of “subjective norms → behavioral attitude” and “Place Attachment → behavioral attitude,” with no significant difference between the mediating effects of Place Attachment and subjective norm. Moreover, when Awe affects environmentally responsible behavioral intention with subjective norm and Place Attachment as mediators, behavioral attitude must change to influence environmentally responsible behavioral intention, and cannot directly affect environmentally responsible behaviors through subjective norm or Place Attachment.

5.1.3. Behavioral Attitude Has a Direct Mediating Effect on the Influence of Subjective Norm and Place Attachment on Environmentally Responsible Behavioral Intention

Subjective norms and Place Attachment have a significant and direct positive effect on behavioral attitudes. Both subjective norms and local attachment affect environmentally responsible behavioral intentions through behavioral attitudes. These findings are consistent with Qiu (2017) [74], who found that both subjective norms and Place Attachment can indirectly influence environmentally responsible behavior through behavioral attitudes. Therefore, behavioral attitudes have complete mediating effects on both subjective norms and Place Attachment.

5.1.4. Occupation, Place Attachment, and Subjective Norm

The effect of Awe on the environmentally responsible behavioral intentions of farmers and herdsmen via the mediation path of “Place Attachment → behavioral attitudes” was significantly greater than that for other occupations. These results indicate that the path mediating effect of Place Attachment plays a more significant role among farmers and herdsmen, while the mediating effect of subjective norms plays a more significant role among non-farmers and non-herdsmen.

5.1.5. Rational and Emotional Factors Jointly Drive Environmentally Responsible Behavioral Intention

Rational factors (behavioral attitude, subjective norm) and emotional factors (Awe, Place Attachment) jointly drive environmentally responsible behavioral intentions. Behavioral attitudes and Awe have significant positive impacts on environmentally responsible behavioral intentions. Awe has an indirect effect on behavioral intentions, and has significant positive impacts on subjective norms and Place Attachment. Both rational and emotional factors can directly and indirectly affect environmentally responsible behavioral intentions. The analysis of demographic variables revealed that environmentally responsible behavioral intentions can be produced in young and middle-aged adults by changing rational factors (behavioral attitudes), while the intentions of the middle-aged can be produced by changing emotional factors (Awe).

5.2. Theoretical Implications

TPB was applied to the study of the factors and mechanisms that influence the environmentally responsible behavioral intentions of community residents in the context of China’s national parks protected areas system. This work complements existing empirical research on the influencing factors and mechanisms of environmentally responsible behavioral intentions [30,37,38,75], and enriches and improves the TPB, broadens its application, and proves the universal value of the TPB model in the field of individual behavior decision making.

First, we found that Awe directly influences environmentally responsible behavioral intentions. Such intentions rely on both social and nature connectedness via subjective norms and Place Attachment. Therefore, we revealed the mechanism by which Awe affects environmentally responsible behavioral intentions. We also demonstrated that Awe affects Place Attachment and subjective norms, and is an antecedent variable that affects environmentally responsible behavioral intentions.

Second, we found that Place Attachment and subjective norms have a significant positive impact on behavioral attitudes and on environmentally responsible behavioral intentions via the mediating effect of behavioral attitudes. This highlights the importance of behavioral attitudes in affecting environmentally responsible behavioral intentions.

Finally, by introducing the two emotional factors of Place Attachment and Awe into the TPB and analyzing and verifying their impacts on environmentally responsible behavioral intentions, we further verified that emotional factors play an important role in the extended TPB model [33]. Analyzing rational and emotional motivation enhances the ability to explain environmentally responsible behavioral intentions, and demonstrates the importance of Place Attachment and Awe in explaining and predicting individual behaviors.

5.3. Management Recommendations

First, a consensus of positive behavioral attitudes should be cultivated via multiple channels, and awareness of environmentally responsible behavior should be nurtured. Residents should be given the opportunity to participate in environmental interpretation services that will guide their behavior [76], and community environmental protection and governance systems should be built that cover all aspects of environmental protection, involve everyone, and include mutual supervision [77,78]. For example, Luorong Village in Potatso national park has established village rules, such as each household can only rebuild one house for self-occupation every 30 years, only dead wood can be used as firewood, each household must take turns to participate in the work of guarding the mountains, and mutual supervision between village committee cadres and villagers is carried out. The implementation of village rules and regulations is restoring the previously destroyed environment and avoids the tragedy of the commons. These measures have produced good results in fostering norms and in guiding community residents to engage in responsible environmental behavior.

Second, local residents’ beliefs, traditions, and customs should be respected and integrated into modern scientific rural management to enrich the ecological culture of the community. In order to develop effective community governance, the point of integration between modern ecological civilization and local history and culture must be found, thereby enhancing the local identity of community residents [79]. With a focus on Place Attachment, community residents should be guided to actively participate in the scientific protection and rational use of natural resources. The reasonable needs of community residents should be actively met through the provision of more jobs and opportunities. Interaction between residents and national parks should be strengthened, and residents’ opinions on the development of national parks should be actively adopted [80]. The protection of this proportion of land leads to improved local ecology and biodiversity, and residents receive ecological compensation and more educational and employment opportunities. The resident lives outside of the national park, but their production and lifestyle are important to the nature preservation of the protected area. We will study different effective incentive measures promoting environmentally responsible behavioral intentions to people in the park and to people outside the park, in the future.

Third, managers should pay attention to the natural and social factors that induce Awe among local residents, and then effectively apply those factors to environmentally responsible behavioral intentions. Different management measures should be implemented for the Buddhists and non-Buddhists, and for people in the park and people outside the park. For example, the Tibetan people worship hallowed mountains and lakes [81], and the Dai people express Awe for the concept of the “Long Forest” [21]. The social connectedness of Tibetan Buddhism emphasizes abstinence from killing and the protection of life, compassion, equality, kindness, mercy, and karmic retribution. Moreover, the worship of hallowed mountains, lakes, and animals can be harnessed to develop ecologically protective behaviors that maintain the diversity of life [47]. Such nature- and culture-induced Awe can be used to cultivate environmentally responsible behavioral intentions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Z. and B.X.; Data curation, T.T.; Formal analysis, T.T., Z.M.; Funding acquisition, M.Z., Z.L., and B.X.; Investigation, W.C., Z.M., and Y.D.; Methodology, M.Z. and W.C.; Resources, Z.L.; Software, W.C.; Supervision, Z.L.; Writing—original draft, M.Z. and W.C.; Writing—review and editing, B.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 41801220 and 42011530079), and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (grant number 2021M703179).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Xueqiong Tang and Shouming Qiu of Southwest Forestry University, China, and Yao Li, Jinlong Zhang, and Yunzhi Deng of Potatso National Park Service. The authors would also like to express their sincere gratitude to volunteers Snaram, Qilichumu, Zhishi Qilin, and Lurong Enzhu. The authors would like to thank the editor and reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Woodley, S.; Bhola, N.; Maney, C.; Locke, H. Area-based conservation beyond 2020: A global survey of conservation scientists. Parks 2019, 25, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley, N.; Jonas, H.; Nelson, F.; Parrish, J.; Pyhälä, A.; Stolton, S.; Watson, J.E.M. The essential role of other effective area-based conservation measures in achieving big bold conservation targets. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2018, 15, e00424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, S.L.; Cazalis, V.; Dudley, N.; Hoffmann, M.; Rodrigues, A.S.L.; Stolton, S.; Visconti, P.; Woodley, S.; Kingston, N.; Lewis, E.; et al. Area-based conservation in the twenty-first century. Nature 2020, 586, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.H.Z. National parks in China: Parks for people or for the nation? Land Use Policy 2019, 81, 825–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igoe, J. National parks and human ecosystems—The challenge to community conservation. A case study from Simanjiro, Tanzania. In Conservation and Mobile Indigenous Peoples: Displacement, Forced Settlement, and Sustainable Development; Berghahn Books: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Vimal, R.; Khalil-Lortie, M.; Gatiso, T. What does community participation in nature protection mean? The case of tropical national parks in Africa. Environ. Conserv. 2018, 45, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Seebunruang, J.; Burns, R.C.; Arnberger, A. Is national park affinity related to visitors’ satisfaction with park service and recreation quality? a case study from a Thai Forest National Park. Forests 2022, 13, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Cheng, X.; Ma, K.; Zhao, X.; Qu, J. Offering the win-win solutions between ecological conservation and livelihood development: National parks in Qinghai, China. Geogr. Sustain. 2020, 1, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Swanson, S.R. The effect of destination social responsibility on tourist environmentally responsible behavior: Compared analysis of first-time and repeat tourists. Tour. Manag. 2017, 60, 308–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.L.; Wang, X.Q.; Mao, Y.; Wang, K.; Yu, Y. An analysis of the awareness and attitudes of community residents and visitors to national parks—Taking Shennongjia National Park as an example. Environ. Prot. 2019, 47, 65–69. [Google Scholar]

- Su, L.; Huang, S.; Pearce, J. How does destination social responsibility contribute to environmentally responsible behaviour? A destination resident perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 86, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, D.; Avenzora, R.; Lee, J.-h. Exploring the outdoor recreational behavior and new environmental paradigm among urban forest visitors in Korea, Taiwan and Indonesia. Forests 2021, 12, 1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshar Jahanshahi, A.; Maghsoudi, T.; Shafighi, N. Employees’ environmentally responsible behavior: The critical role of environmental justice perception. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2021, 17, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobley, C.; Vagias, W.M.; DeWard, S.L. Exploring additional determinants of environmentally responsible behavior: The influence of environmental literature and environmental attitudes. Environ. Behav. 2009, 42, 420–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaske, J.J.; Kobrin, K.C. Place attachment and environmentally responsible behavior. J. Environ. Educ. 2001, 32, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.-Y.; Yu, H.-W.; Hsieh, C.-M. Evaluating forest visitors’ place attachment, recreational activities, and travel intentions under different climate scenarios. Forests 2021, 12, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Mei, F. Environmental satisfaction and environmentally responsible behavior research: A case study on Shenzhen Coastal Ecological Park. Acta Sci. Nat. Univ. Pekin. 2018, 54, 1303–1310. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Cheng, J.; Zhu, G.; Liu, Y.; Xiangyang, Y.U. Research on the influential mechanism of nostalgia, leisure involvement, place attachment and environmentally responsible behavior. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2019, 33, 190–196. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.; Dong, L.; Wang, X. The Relationship between place attachment and environmental responsible behaviors: The research based on the beach tourists. Sociol. Rev. China 2013, 1, 76–85. [Google Scholar]

- Sang, J.D.Z. Tibetan Buddhism ecological protection thought and practice. Qinghai Soc. Sci. 2001, 1, 102–105. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. Ecological implication on the LONG forest culture of Dai nationality. Stud. Dialectics Nat. 2011, 27, 78–84. [Google Scholar]

- Leahy, J.; Lyons, P. Place attachment and concern in relation to family forest landowner behavior. Forests 2021, 12, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, X.; Zhang, H. Progress of environmentally responsible behavior research and its enlightenment to China. Prog. Geogr. 2016, 35, 1459–1472. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.A.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behaviour: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Conner, M.; Norman, P.; Bell, R. The theory of planned behavior and healthy eating. Health Psychol. 2002, 21, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, L.; Ajzen, I. Predicting dishonest actions using the theory of planned behavior. J. Res. Personal. 1991, 25, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, P.; Conner, M.; Bell, R. The theory of planned behavior and smoking cessation. Health Psychol. 1999, 18, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.F. The theory of planned behavior and Internet purchasing. Internet Res. 2004, 14, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Minton, E.A.; Spielmann, N.; Kahle, L.R.; Kim, C.-H. The subjective norms of sustainable consumption: A cross-cultural exploration. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 82, 400–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru, X.; Wang, S.; Yan, S. Exploring the effects of normative factors and perceived behavioral control on individual’s energy-saving intention: An empirical study in eastern China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 134, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallentin, F.Y.; Schmidt, P.; Davidov, E. Is there any interaction effect between intention and perceived behavioral control in the theory of planned behavior? A meta-analysis and an evaluation with three estimation methods. Methods Psychol. Res. Online 2003, 8, 127–157. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, X.M. Consumers’ ethical purchasing intention in Chinese context: Based on TPB perspective. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2012, 15, 22–32. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Li, Q.; Lin, Z. Outcome efficacy, people-destination affect, and tourists’ environmentally responsible behavior intention: A revised model based on the theory of planned behavior. J. Zhejiang Univ. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2014, 44, 88–98. [Google Scholar]

- Yuriev, A.; Dahmen, M.; Paillé, P.; Boiral, O.; Guillaumie, L. Pro-environmental behaviors through the lens of the theory of planned behavior: A scoping review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 155, 104660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Longchang, W.U. The categories, dimensions and mechanisms of emotions in the studies of pro-environmental behavior. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 23, 2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigbur, D.; Lyons, E.; Uzzell, D. Attitudes, norms, identity and environmental behaviour: Using an expanded theory of planned behaviour to predict participation in a kerbside recycling programme. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 49, 259–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leeuw, A.; Valois, P.; Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P. Using the theory of planned behavior to identify key beliefs underlying pro-environmental behavior in high-school students: Implications for educational interventions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 42, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Roggenbuck, J.W. Measuring place attachment: Some preliminary results. In Proceedings of the National Parks and Recreation, Leisure Research Symposium, San Antonio, TX, USA, 20–22 October 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, W.Y.; Zhang, J.; Luo, H. Relationship between the place attachment of ancient village residents and their attitude towards resource protection—A Case study of Xidi, Hongcun and Nanping villages. Tour. Trib. 2008, 23, 87–92. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, M.; Dong, S.; Wu, H.C.; Li, Y.; Su, T.; Xia, B.; Zheng, J.; Guo, X. Key impact factors of visitors’ environmentally responsible behaviour: Personality traits or interpretive services? A case study of Beijing’s Yuyuantan Urban Park, China. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 23, 792–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, D.; Peng, K.; Feng, Y. Positive emotion: Awe. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 21, 1996–2005. [Google Scholar]

- Keltner, D.; Haidt, J. Approaching awe, a moral, spiritual, and aesthetic emotion. Cogn. Emot. 2003, 17, 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.X.; Zhao, L.; Hu, C.Y. Tourists’ Awe and environmentally responsible behavior: The mediating role of place attachment. Tour. Trib. 2018, 33, 110–121. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Lyu, J. Inspiring awe through tourism and its consequence. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 77, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, C.; Yu, P.; Chu, G. What influences tourists’ intention to participate in the Zero Litter Initiative in mountainous tourism areas: A case study of Huangshan National Park, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 657, 1127–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, J.Z.X. The relationship between Tibetan religious belief and environment protection. J. Qinghai Normal Univ (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2014, 36, 68–72. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.M.; Li, J.; Wu, F.H. Connectedness to nature: Conceptualization, measurements and promotion. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2018, 34, 120–127. [Google Scholar]

- Gosling, E.; Williams, K.J.H. Connectedness to nature, place attachment and conservation behaviour: Testing connectedness theory among farmers. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Liu, Y.; Lai, I.; Yang, L. Awe: An important emotional experience in sustainable tourism. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, W.; Feng, C.; Liu, F.; Li, J. Biodiversity conservation in China: A review of recent studies and practices. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnol. 2020, 2, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, H.; Chen, J.; Shi, J.; Wang, W.; Huang, L.; Ye, J.; Luan, X. Impacts of spatial relationship among protected areas on the distribution of giant panda in Sichuan area of giant panda national park. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2020, 40, 2347–2359. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, X. The establishment of national park system: A new milestone for the field of nature conservation in China. Int. J. Geoherit. Parks 2020, 8, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Qiu, M. Research on establishing nature reserve system with national park as the main body: A case study of Potatso National Park System Pilot Area. Int. J. Geoherit. Parks 2020, 8, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. Development status and ecological compensation mechanism of Shangri-La Pudacuo National Park. J. Southwest For. Univ. Soc. Ences 2018, 2, 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, X.L. Investigation report on the pilot reform of the system of Potatso National Park. Creation 2022, 30, 59–62. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J.Y.; Xue, X.M. Survey on participatory tourism development in luorong community around Pudacuo National Park in Shangri-La. J. Southwest For. Univ. 2010, 30, 71–74. [Google Scholar]

- Halpenny, E.A. Pro-environmental behaviours and park visitors: The effect of place attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.-M.; Wu, H.C.; Huang, L.-M. The influence of place attachment on the relationship between destination attractiveness and environmentally responsible behavior for island tourism in Penghu, Taiwan. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 1166–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, K.S.; Terry, D.J.; Masser, B.M.; Hogg, M.A. Integrating social identity theory and the theory of planned behaviour to explain decisions to engage in sustainable agricultural practices. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 47, 23–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Patterson, M.E.; Roggenbuck, J.W.; Watson, A.E. Beyond the commodity metaphor: Examining emotional and symbolic attachment to place. Leis. Sci. 1992, 14, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Dong, L.U.; Powpaka, S. Tourist’s Awe and Loyalty: An explanation based on the appraisal theory. Tour. Trib. 2015, 30, 80–88. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Dong, L.U.; Ting, W.U. Impacts of awe emotion and perceived value on tourists’ satisfaction and loyalty—The case of Tibet. East China Econ. Manag. 2015, 29, 79–85. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis, 5th ed.; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Nunally, J.C. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Kolar, T.; Zabkar, V. A consumer-based model of authenticity: An oxymoron or the foundation of cultural heritage marketing? Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 652–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Mavondo, F.; Sowamber, V. Corporate social responsibility at LUX* resorts and hotels: Satisfaction and loyalty implications for employee and customer social responsibility. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, K.A.; Stine, R.A. Bootstrapping goodness-of-fit measures in structural equation models. Sociol. Methods Res. 1992, 21, 205–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enders, C.K. An SAS macro for implementing the modified bollen-stine bootstrap for missing data: Implementing the bootstrap using existing structural equation modeling software. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 2005, 12, 620–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun. Monogr. 2009, 76, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, T.L. The selection of upper and lower groups for the validation of test items. J. Educ. Psychol. 1939, 30, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, D.G.; Bland, J.M. Interaction revisited: The difference between two estimates. BMJ Br. Med. J. 2003, 326, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qiu, H. Developing an Extended Theory of planned behavior model to predict outbound tourists’ civilization tourism behavioral intention. Tour. Trib. 2017, 32, 75–85. [Google Scholar]

- Sethi, V.; Jain, A. The role of subjective norms in purchase behaviour of green FMCG products. Int. J. Technol. Transf. Commer. 2020, 17, 219–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Dong, S.; Guo, H.; Gao, N.; Yu, L.I.; Tang, T.; Tengwei, S.U. Effects of environmental interpretation service of national park on guiding public’s behavior. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2019, 33, 202–208. [Google Scholar]

- Godden, L.; Ison, R. Community participation: Exploring legitimacy in socio-ecological systems for environmental water governance. Australas. J. Water Resour. 2019, 23, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Arriaga, E.; Williams-Beck, L.; Vidal, L.E.; Hernández, L.E.V.; Arjona, M.E.G. Crafting grassroots’ socio-environmental governance for a coastal biosphere rural community in Campeche, Mexico. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2021, 204, 105518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhamad Khair, N.K.; Lee, K.E.; Mokhtar, M. Sustainable city and community empowerment through the implementation of community-based monitoring: A conceptual approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelan, A.; Ruhanen, L.; Mair, J. Ecosystem services approach for community-based ecotourism: Towards an equitable and sustainable blue economy. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1665–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Department, J.E.; University, Q.N. On ecological thought and practice in the Tibetan buddhism. J. Qinghai Norm. Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2016, 38, 35–40. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).