Abstract

The development of neuroanatomy and neurophysiology has revealed many new details about neurons’ operation over the past few decades, requiring modifications to their theoretical models. The development of computing technology enables us to consider the fine details the new model requires, but it necessitates a different approach. To achieve that goal, the disciplinarity of science must be revisited for living matter, the theoretical model must be updated, and a series of processes instead of states must be considered; furthermore, new mathematics, algorithms, and computing technologies for the new view are also needed. We provide an algorithm implementing the mathematics of the updated theoretical model that considers the neuronal current to consist of charged ions (and so considers thermodynamic effects) and opens the way for explaining the mechanical, optical, etc., consequence phenomena of the electrical operation. We use a new technology in this effort: a tool designed to achieve extreme accuracy in simulating high-speed electronic circuits. The algorithm applies the cross-disciplinary unified electrical/thermodynamic model, along with an unusual programming method, to provide new insights into neuronal operations, describe the processes that take place in living matter, and determine their computing implementation.As has long been suspected, the faithful simulation of biological processes requires accurately mapping biological time to technical computing time. Therefore, the paper focuses on time handling in biology-targeting computations, especially in large-scale tasks. We also touch on the question of simulating the operation of their network, which is contrasted with that of Spiking Neural Networks. The way technical computing works inhibits efforts to achieve the required accuracy in reproducing the temporal behavior of biological operations using conventional computer programs.

1. Introduction

The brain, with its information-processing capability, and the mind, with its conscience and behavior, are among the biggest mysteries in science. From the perspective of understanding neural computing, the large, coordinated projects spanning many years failed. A decade ago, it was decided that “The Human Brain Project (https://www.humanbrainproject.eu/en/, accessed on 1 December 2025) should lay …a new model of …brain research, …to achieve a new understanding of the brain …and new brain-like computing technologies”. However, only new graphic user interfaces and libraries [1] have been achieved to delineate the many-decades-old understanding; furthermore, “surprisingly, [among the winners of the supercomputer competition] there have been no brain-inspired massively parallel specialized computers” [2]. As the Brain Initiative summarized, “Yet for the most part, we still do not understand the brain’s underlying computational logic” [3].

On the occasion of the anniversary of Erwin Schrödinger’s famous book [4], we could revive the following statements: “The construction [of living matter] is different from anything we have yet tested in the physical laboratory”; “It is working in a manner that cannot be reduced to the ordinary laws of physics”. Even if we find the ‘non-ordinary’ physical laws [5] The theory of neural information processing also needs to revisit our notions of information and its processing [6,7,8].

The “new understanding” of the brain encompasses the incorporation of recent anatomical and physiological discoveries from the past few decades into the model along with the correct (physically based) electrical and thermodynamic descriptions of the processes. As the observations revealed finer details of its operation, we have learned that the operation of the neuron is too complex to be described by a single physical process (and, what is more, even by a single discipline); using a model described by a single mathematical equation, we followed Feynman’s hint: “Breaking down topics into digestible chunks and explaining them helps you identify gaps in your knowledge. This creates new neural pathways in your brain, which makes connecting ideas and concepts easier” [9]. Our model divides the neuron’s operation into stages (see Section 6.3 and Section 4 in [10]) where different physical processes take place. Even within those stages, the intensity of different contributions changes over time. Describing those processes requires precise time handling, which can be ensured only by using ‘non-ordinary’ time-handling technology and simulation algorithms.

First, we discuss the fundamental concepts used in the paper: in Section 2, we explain how time and events are interpreted. In Section 3, we show the fallacies that block advances in the field in connection with spiking and information, including mapping information-processing-related concepts between technical and biological implementations. We also discuss the relevance of spiking across the two implementations. In addition to the principal aspects, the technical implementations, prepared for different goals or having outdated implementations, also introduce problems for implementation, as touched upon briefly in Section 4. Although biological computing can be interpreted in terms of generalized computing, we present its neuronal operation-specific aspects in Section 5. The different attributes and implications of the neuronal operation are presented in Section 6 without going into detail on the biological implementation. Section 7 synthesizes the different mentioned aspects of the algorithm.

2. Fundamental Concepts

We formulate problems, provide their numerical solutions (including algorithms), and open the way for mathematics to provide analytical solutions. Our procedure is surely not ordinary, yet it meets the requirement given by Feynman [9]: “an effective procedure is a set of rules telling you, moment by moment, what to do to achieve a particular end; it is an algorithm.” We know from the beginnings that we must use “the language of the brain, not the language of mathematics” [11] and that “whatever the system [of the brain] is, it cannot fail to differ from what we consciously and explicitly consider mathematics” [12]; moreover, we add that, maybe, appropriate mathematical methods have not yet been invented for this problem. “We so far lack principles to understand rigorously how computation is done” [13] in living, or active, matter. We also note that we lack principles of computation for large-scale, complex computing systems [14], especially when using them to imitate neuronal operations.

As Ref. [15] classified, “the term neuromorphic encompasses at least three broad communities of researchers, distinguished by whether they aim to emulate neural function (reverse-engineer the brain), simulate neural networks (develop new computational approaches), or engineer new classes of electronic device.” We address the first class, indirectly touch upon the second, and discuss the third in [10]. Many methods and ideas, including half-understood and misleading ones, are used to imitate the brain’s operation. Unfortunately, all these communities inherited the wrong ideas above; see [10]. We aim to provide an algorithmic-level description of the genuine processes of neuronal operation (see Section 4 in [10]) for these fields, facilitating a better understanding. Mainly because “the operation of our brain differs vastly from that of human-made computing systems, both in terms of topology and in the way it processes information” [16], a precise description of how to map one’s operation (including its temporal behavior) to the other is needed.

At the level of abstraction we use, one does not need to consider all biological details since “despite the extraordinary diversity and complexity of neuronal morphology and synaptic connectivity, the nervous systems adopt a number of basic principles” [17]. Moreover, we proceed based on those basic principles, emphasizing the need for precise timing. Although we discuss the operation of single neurons here, we must not forget that “what makes the brain a remarkable information processing organ is not the complexity of its neurons, but the fact that it has many elements interconnected in a variety of complex ways” [18]. We must implement the operation and cooperation of the fundamental pieces with great accuracy. Any inaccuracy in the biological model or its mapping to computing can lead to far-reaching consequences in their complex interaction. Physiology and neuroscience discovered that “timing of spike matters”, giving way to interpreting Hebb’s learning rule [19,20], which usually remains outside the scope of mathematics when it attempts to imitate biological learning. A vital part of what happens in a biological neuron is the temporal coordination of events [14] not only during learning. Although it is not widely known and used, technical computing also has temporal behavior [14]. The two types of temporal behaviors, however, differ drastically [10]. Misinterpretation of those time courses leads to poor results when attempting to emulate one type of computation with another. In addition, technical solutions (such as time slicing, scheduling, caching, threading, queuing, timestamping, arbitration, etc.) are prepared for entirely different goals, leading to quasi-randomized operating times. So they introduce severe limitations on the implementable time resolution for biological purposes, distort the linearity of time scales, and they can even change the order of events, leading to non-reproducible causality problems.

The topic of describing neuronal operation is pervasive and comprises several subtopics, such as the cross-disciplinary discussion of the underlying physical theory, the new mathematics because of changing the oscillator type, the time-aware biological operation from the point of view of computing, the computer architectural aspects of large-scale tasks, intensive communication, and time-aware implementation, and the algorithm implementing the new features above. We also cite our parallel publications to avoid unnecessary repetition.

2.1. Schrödinger’s Question

In their very accurately formulated question, “How can the events in space and time which take place within the spatial boundary of a living organism be accounted for by physics and chemistry?”, Schrödinger also pointed to the importance of time handling in understanding neuronal operation, so it must have a central place in our algorithmic handling. He focused on (at least) these significant points:

- ‘events’: Unlike non-living matter, living matter is dynamic, changing autonomously by its internal laws; we must think differently about it, including making hypotheses and testing them in the labs (including computing methods). Processes (and not only jumps) occur within it, and we can observe some characteristic points.

- ‘space and time’: Those characteristic points are significant changes resulting from processes that have material carriers, which change their positions with finite speed, so (unlike in classical science) the events also have the characteristic of ‘time’ in addition to their ‘position’. In biology, the spatiotemporal behavior is implemented by slow ion currents. In other words, instead of ‘moments’, we sometimes must consider ‘periods’, and, in the interest of mathematical description, we model slow processes by closely matching ‘instant’ processes.

- ‘living organism’: To describe its dynamic behavior, we must introduce a dynamic description.

- ‘within the spatial boundary’: Laws of physics are usually derived for stand-alone systems in the sense that the considered system is infinitely far from the rest of the world; also, in the sense that the changes we observe do not significantly change the external world, so too its idealized disturbing effect will not change it. In biology, we must consider changes in the non-infinite resources.

- ‘accounted for by physics’: [by non-ordinary laws] We are accustomed to abstracting and testing a static attribute, and we derive the ‘ordinary’ laws of motion for the ’net’ interactions. In the case of physiology, nature prevents us from testing ‘net’ interactions. We must understand that some interactions are non-separable, and we must derive ‘non-ordinary’ laws [4]. The forces are not unknown, but the known ‘ordinary’ laws of motion of physics are about single-speed interactions.

- ‘yet tested in the physical laboratory’ [including physiological ones]: We need to test those ‘constructions’ in laboratories, in their actual environment, and in their ‘working state’. As with non-living matter, we need to develop and gradually refine the testing methods and the hypotheses. Moreover, we must not forget that our classical methods refer to ‘states’, and this time, we test ‘processes’. For not only measuring them but also in handling them computationally, we need slightly different algorithms.

2.2. Concept and Time of Event

The central idea of simulation is the concept of an “event”. We use the term ‘event’ in the classic sense: something happens at a given time. In biology, “A signal is a physical event that, to the receiver, was not bound to happen at the time or in the way it did” [21]. Similarly, we “define an elementary operation of the brain as a single synaptic event” [22], which must have an accompanying time. Notice that the time in a system working with temporal arguments, whether biological or technical, per definitionem, is the time of a received instead of a sent event. It makes no difference in technical computing where “instant signal propagation” is assumed, but the signal propagation in biological systems is slow; we need to introduce the time when something happens in one component and the time when the other component receives a message about what happened. In biological systems, the period between these events is much longer than the period when the objects compute the information content of the messages; this is why von Neumann told [23] that it would be ‘unsound’ to apply their mathematical theory to neural computing. In the technical implementation, the slow signal propagation must be implemented by using artificial delays. Given that one must add an appropriately calculated delay to the time of sending, the sending system must know the downstream partners (i.e., which nodes require the result it sends) and the propagation delay added per message to the time of sending. Biological systems employ various mechanisms for synchronization to compensate for the slow signal propagation speed. In technical systems, one must follow the “proper sequencing” principle of computation [10,14,23].

When simulating biological time in technical systems, we must simulate the transmission time by an appropriate delay time. The upstream neuron must maintain the needed delay times (the temporal length of the axon) per connection. The receiver has no way to distinguish its inputs, as triggering its output spike works on a “first-come, first-served” basis. The incoming spikes must be received strictly in the order of their arrival time. Exceeding the neuron’s membrane threshold voltage renders the still unprocessed inputs obsolete: the neuron closes its inputs. By exceeding the threshold, it prepared its result: how quickly the membrane received its needed charge. Making an accurate “digital twin” of the anatomic structure of the brain without attaching the temporal length to the spatial length of the axons (the conduction velocities may be very different) is not sufficient, as the failure of the whole-brain simulations witnessed [24,25]. However, as Ref. [26] summarizes, none of the past or present projects plan to consider timing when making a connectivity map.

In addition, we know that the propagation time is modulated by the receiving neurons, per synaptic input [14], with the goal to implement neuronal-level learning. Furthermore, a membrane maintains a per-synaptic input neuronal memory by keeping its voltage level above its resting potential. Because of those temporal changes, the result of the neuronal computation (the time of the output spike) is susceptible to the correct time handling. “The timing of spikes is important with a precision roughly two orders of magnitude greater than the temporal dynamics of the stimulus” [27]. One must prepare the systems targeting to imitate biological networks to handle the simulated time with such accuracy.

By using the Inter-Spike Interval (ISI) only, a biological system with a firing rate at 500 can only achieve a time resolution worse than 2 (independently of the assumed coding type). To achieve the much better observed resolution, biology uses the exact relative timing of spikes from networked neurons. That method assumes an independent parallel processing of signals. Furthermore, the neurons cooperate in a very special form. Upstream neurons send information they want at the time they want. The receiving neuron (by setting its time windows) selects from which upstream neurons it receives information and how much charge it wants to receive. A time-slicing-based technical system implements about 1 ms slices of processor time, which is apparently similar to the ISI times. In addition, the processor provides a clock signal of precision, so apparently, much finer timing is possible. However, the instruction sequence can be changed only by hardware (HW) means, and the independent software (SW) scheduling processes (including thread and neuron scheduling) not only allow a scheduling precision with the multiples of time slices, but also they do not guarantee the “proper sequencing” of the events.

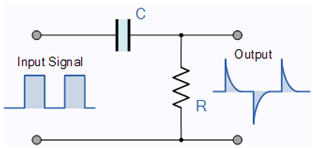

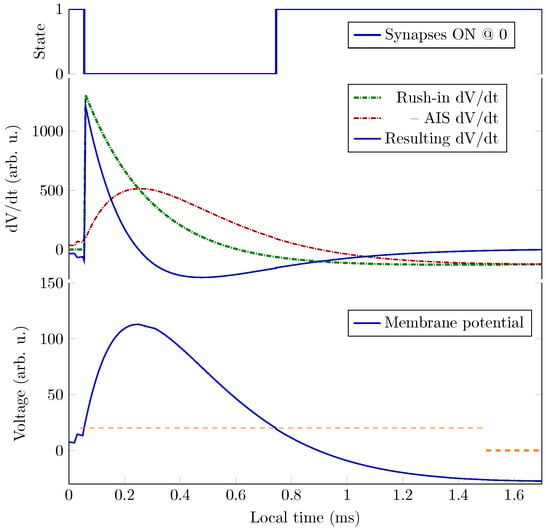

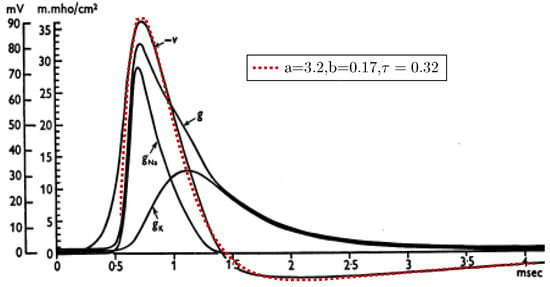

As Figure 3 shows, the non-excitable period of a neuron is shorter than 1 ms, and to integrate the sharp gradient, an integration step of about 2 may be needed. Precise time measurement (in the sense that is measured by its effect) at this scale can be carried out only by using special hardware devices; the “time slices”, the ordinary computers use, are at least an order of magnitude larger. By economizing on measuring time, one derives very inaccurate temporal dependencies; see, for example, Figure 5.

For artificial neurons, the needed time sensitivity should be derived from the technical implementation and strongly depends on the coding/decoding method. In our timing analysis, we check the parameters that influence the achievable resolution. It was known from the beginning that using von Neumann’s stored-program concept converts the logical dependence of actions into temporal dependence [28]. One must consider that biological computing is inherently parallel, while technical computing is serial (or, at best, parallelized sequentially), breaking down events that co-occur. The fundamental requirement against a correct algorithm is to convert parallelized sequential events into parallel events (with the same time resolution).

2.3. Time

The paper uses different time concepts and emphasizes their differences. The different time concepts are outlined below:

- Biological time that physiologists record when observing biologically meaningful events;

- Simulated time is a logical time (a biologically faithful time scale) maintained by a user-level scheduler. The simulations of the biological events are scheduled to happen exactly at the true biological time independent of the computer facilities;

- Processor time that the processor spends with the simulation task (instruction time and processor speed dependent);

- Wall clock time that the programmer records when the computation reaches code parts that simulate biologically meaningful events;

- Non-payload time that the HW/SW parts of the system spend with needed but not directly task-related activities (system load, task type, and architecture dependent);

- Time step (or grid time): a global time step on wall-clock time scale in parallelized computations where different threads/processors wait for each other’s results;

- Heartbeat time is a per-object and per-stage time step on simulated time scale where values of the simulated variables of a process are calculated;

- Time resolution on the simulated time scale is the period within which the exact time makes no significant difference (the simulator digitizes the continuous time);

- Quasi-biological time assumes a linear dependence between the wall-clock time (or the processor time) and the simulated time; it is used by non-time-aware simulations.

Biological time is not related to the complexity of simulating the corresponding events by computing. A biological ‘step’ may need a large amount of machine instructions. The non-payload time depends on the workload (which is a very demanding one for neural networks, as the paper emphasizes). Furthermore, it makes the computation’s length quasi-random.

In the text below, the results refer to biological time (sometimes called simulated time). The concept of “grid time” is used in technical computing, where the whole computation (in a technical sense) is suspended, and the gridpoints only communicate: they share their state at the time when the computing was suspended. The “heartbeat time” is actually an integration time step on a biological time scale and does not involve communication. The concept and expression are extensively used in SystemC V3.3 to distinguish it from “clocking”; it is a less resource-hungry method of timing (independent from the clock-based synchronization) and provides more flexibility for implementing the model.

2.3.1. Time in Technical Computing

In technical computing, an event is an electrical signal that denotes the beginning or end of an elementary operation or signals transferring control to another place in the program, or it denotes that the program’s control reached a specific instruction in the memory. It has a particular ‘wall-clock’ time, a ‘processor-time’, and a ‘pseudo-biological time’ (in the library and language we use [29], it is called ‘simulation time’). The last one (provided that the computer program is accurate and faithfully reproduces neuronal operation) corresponds to biological time, and the paper is about controlling the simulation time of neuronal operation. The other two depend on many factors, and whether they can be uniquely and proportionally mapped to the simulation time is doubtful. Not only can the time of elementary operations be mapped to each other with a factor differing by several orders of magnitude, but they also include the subtleties of computer operation (system calls, Input/Output (I/O) operations, memory access, and bus arbitration times) and scheduling computer resources between the simulated biological resources. In addition, the latter two times depend on the type of workload the simulation represents [30,31,32,33,34]. The scaling of computing performance (and, as a consequence, the mapping of computing-related time to biology-related time) is strongly nonlinear.

The notion of time is vital for biological and electronic computing [14]. However, when simulating biological objects by electronic computers, they are not identical, and, what is worse, they are not even proportional. The way computers work [14] destroys even the sequence of events. For this reason, a pseudo-time is used, which we call ‘simulated time’. The biological processes are divided into segments of varying sizes. At the characteristic points, the period for the biological process is set and its length is transferred to the scheduler of the engine (important: this scheduler sits on top of the scheduler of the operating system and works independently from it). The information includes a callback function that determines when the activity is to be executed. Many biological processes run simultaneously, and they individually communicate with the scheduler. This way, the scheduler has the information on which biological process wants to use the processor in chronological order.

The scheduler maintains the simulated time as multiples of a ‘time resolution’. In this way, the continuous simulated time is mapped to discrete time steps. The time between those discrete steps is considered to be the same. When comparing continuous time values of any kind, a practical need is to define a tolerance (called “time resolution”), which is a period within which two values are considered equal. A shorter period makes the computation more accurate, but it requires more computing capacity. The time course of the considered biological quantities may also require varying time resolutions for the simulation. In this sense, the per-system “grid time” is also a form of time resolution. We use a per-neuron varying “heartbeat time” in the simulator, which is close to the actual time resolution in the simulated biological system, and a (much) smaller technical time resolution used by the simulator’s scheduler.

2.3.2. Time Scales

The basic issue with simulating biology by technological means is that three time scales exist, and they are connected by events only (i.e., non-temporal characteristics of what happens). We have a wall-clock time, that is, how much time passes between the events on the wall-clock; how much processor time is needed to imitate the operating results in the events, and how much time the genuine biological system needs to operate between those events. The actual computer processing time is not directly measurable, so a proportionality (implying a homogeneous workload and uniform resource utilization) between the processing and the wall-clock times is usually assumed. After that, the wall-clock time is used as ’the time’ or ’the computing time’ by adding its empirical ratio to the also empirical biological time. The lengths of the computing and the biological operation time periods are not proportional at all. Their ratio depends on several factors, including the technical parameters and architecture of the computing system, as well as the complexity and detail of the computation.

This empirical ratio is an integral quantity (a long-term average) only; it cannot be used directly to align the simulated events. Since biological neurons communicate with each other, and at that given communication time, the equivalent computing time may be different, the time scales of the technical neurons must be aligned by some method—at least approximately. The oldest method (see Algorithm 1) is to use “time slices” (also called “grid time”), i.e., to divide the biological time into slices and to perform simulating calculations only for that slice period in all neurons and then stop. That is, at these synchronization points, all the neuronal computations stop, send the result of their computations to their fellow neurons, and receive similar data.

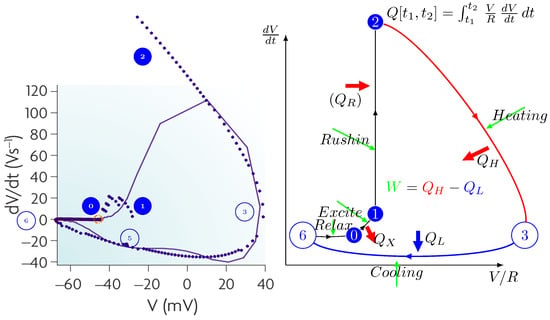

The ratio of computing time to biological time is called real-time performance (i.e., how closely the two match). To overcome the limitation stemming from the computing workload [30,31,32,33,34], typically, a 1 ms ‘integration time step’ (measured on biological scale) is used. To study biological processes with finer time resolution, one can also use a smaller step time. That step time, however, disproportionately prolongs the overall computation time (slowing down the simulation). Furthermore, as seen in Figure 3, the gradients change steeply; in some phases, they need integration step sizes near . Figure 5 depicts the effect of the time resolution on the accuracy of deriving a phase diagram.

Natively, computing can only eventually account for the processing time but not control it. It is also hard to find an integration time step that is not a waste of computing time and still provides sufficiently accurate results.

2.3.3. Aligning the Time Scales

The deviation and nonlinearity in the simulation’s wall-clock time and simulated biological time were observed, and various methods to mitigate their effects were introduced. The most straightforward approach is to compare the total simulated time to the total wall-clock time and assume that, on average, a constant factor relates biological time to simulation time. It is, however, not valid for the individual events: they can change their distance and even their order; the time course of the events may differ drastically. The usual (although high-speed) serial bus makes the transfer times nondeterministic [10,14]. In vast technical computing systems, performing all scheduled transfers may require up to dozens of minutes, as shown in Figure 1 of [35]. In other words, the transfer time varies in a quasi-random way between a few nanoseconds and several minutes, so in the worst case, the length of the period of two events with a distance of a fraction of a millisecond on the biological time scale can amount to minutes on the computing time scale. To avoid practically never-ending computations, “spikes are processed as they come in and are dropped if the receiving process is busy over several delivery cycles” [36]. These are clear signs that, mainly due to the differing operating principles, the vast technical systems cannot handle the amount and/or density of events that biological simulations need, which is mainly due to their extensive communication needs. The present available serial systems do not enable that performance to be reached [32]. “The idea of using the popular shared bus to implement the communication medium is no longer acceptable, mainly due to its high contention” [37].

2.3.4. Time Resolution

The way we perform the simulation is by defining events (such as the beginning or end of computing, receiving an input, etc.) or, moreover, performing the actions that happen at the same (biological) time. The “same time” in this context means that the simulated times are within a so-called “time resolution”. The biological actions are implemented as a kind of callback function that is activated when the corresponding (simulated) time arrives. Choosing a shorter time resolution results in slightly more accurate results at the price of much more computing time. Our experience shows that given that the time derivative of the rush-in voltage is a very steep function (see Section 6.2), which is made even steeper by adding the Axon Initial Segment (AIS) current-related derivative, it should be as low as 2 to keep the value of around 1 (compare it to the 1 ms integration step commonly used by neuronal simulators [36]).

2.4. Timestamping

When using timestamping (i.e., attaching the wall-clock times of happening to the events), there are two bad choices. Option one is for neurons to have a (biological) sending-time-ordered input queue and begin processing when all partner neurons have sent their message. (The neurons form a linear chain, but the computing scheduler does not know about that chaining.) That needs a synchrony signal, leading to severe performance loss [32]. Option two is processing the messages as soon as they arrive, enabling one to give feedback to a neuron when processing a message with a timestamp referring to a biologically earlier time but received physically later. In all cases, it is worth considering if their effect exceeds some tolerance level compared to the last state. Moreover, one shall mitigate the need for communication in this way.

When training an Artificial Neural Network (ANN), one starts showing an input, and the system begins to work. It uses its synaptic weights as valid before showing that input. Its initial weights may be randomized or correspond to the previous input data. The system sends correct signals, but a receiver processes a signal only after it is physically delivered (whether or not the message envelope contains a timestamp). It may start to adjust its weight to a state that is not yet defined. In a cyclic operation, the state is returned to its previous state. (Of course, the effect cannot be observed when random weights are used.) It is fine in continuously operating biological systems but not when a technical system is just starting to work, especially when upgrading with new information, leading to ‘catastrophic forgetting’. In their operation (essentially an iteration), without synchronization, the actors, in most cases, use wrong input signals, and they surely adjust their weights to false signals initially and with a significant time delay at later stages. Neglecting networks’ temporal behavior, in a lucky case, the system will converge but painfully slowly. Or not at all.

Synchronization is a must, even in ANNs. Care must be taken when using accelerators, feedback, and recurrent networks. Time matters; furthermore, the computing theory is valid only for linear sequential computing. Providing faster feedback for computing neuronal results faster cannot help. The received feedback delivers the state variables that were valid long ago, which slows down the computation. In biology, spiking is also a ‘look-at-me’ signal: the feedback shall be addressed to that neuron that caused the change. Without considering the spiking time (organizing neuron polling in a software cycle), neurons receive feedback about ‘the effect of all fellow neurons, including me’, and adjust all weights of neurons using the same metric. Unlike in biology, the inputs are not distinguished: the same correction is applied to both good and wrong inputs.

2.5. Simulating Time in SystemC

The software we use is a special C++-based library SystemC with a user-level scheduler [29,38]. The primary field of application of the software library is to prepare electronic designs, so some formal elements are to be considered. For using all its features, the complete Reference Guide [38] may be needed for developing the code, but using the well-written core of the packet, no special programming knowledge is necessary. However, it is advantageous to study the textbook [29]. The SystemC-specific elements are typically confined to low-level modules, and the user-accessible modules resemble standard C++ modules, although their names and descriptions may reflect their specialties.

When executing the next element of the event queue follows (see Section 4.1.1), the scheduler advances the simulated time to the value of the requested time of action of the actual item. If more than one action is scheduled at the same time, all those actions are performed in an arbitrary order. At the end of the period, the callback function notifies the biology-imitating process that the requested timing period is over (meaning that the requested computing activity was performed), and the scheduler takes the following item in the queue.

This way, the simulated biological objects work on the same time scale. Through the elapsed time and/or notifying each other, they can cooperate. Although the periods of the simulated time and the period while the computer works out the simulated task are vastly disproportional, the simulation is perfectly timed. The simulated process requests that its phases be scheduled to the biologically correct time, and they are executed at a processor time when the processor has free activity time.

3. Spiking and Information

One of the most eye-catching features (historically) of biological neurons is that they receive and generate intense charge pulses called spikes. It is known from the beginning that “There is, however, another parameter of our neuronal signal. The time interval between the successive impulses can vary” [21]. Although the role of time has been confirmed in several studies, and there is general agreement that time is at the heart of communication within neural systems, there is no consensus on how time is encoded. It is even questionable if coding as a metaphor is acceptable for neurons [39].

3.1. Information Coding

We must distinguish “coding” at the perception level and “coding” at the neural communication level. “Information that has been coded [at the perception level] must at some point be decoded also. One suspects, then, that somewhere within the nervous system there is another interface, or boundary, but not necessarily a geometrical surface, where ‘code’ becomes ‘image’” [40]. We use the concept of “coding” at the neuronal level, that is, how the spike pulses convey information. Given that the information is temporally and spatially distributed—moreover, most of the preconditions of the applicability of Shannon’s communication theory [41] are not fulfilled—it is unrealistic to expect a quantitative relation between spikes and the information they deliver.

The information must be coded (and will be converted to a signal after coding), and if so, it must be correspondingly decoded and converted to information. Shannon [42] also warned that this coding/decoding must not be confused with that “the human being acts in some situations like an ideal decoder, this is an experimental and not a mathematical fact”. Notice that a human observer sees a signal instead of the coded information. Up to this point, we can assume that a presynaptic neuron produces information, and the system transfers it to the postsynaptic neuron using an axon. Notice also that Shannon requires cutting a neuron logically to a receiver (the synapses and the membrane) and a transmitter (the AIS) units, which is in line with the input and output sections that von Neumann introduced.

In neuroscience, “the interpretational gamut implies hundreds, perhaps thousands, of different possible neuronal versions of Shannon’s general communication system” [43]. As we discussed in [6], neuronal communication does not follow Shannon’s model for communication. In this way, some “information loss” is surely incurred. If we consider that the ISI carries information and a neuron takes into consideration in its “computing” only the spikes that arrive within an appropriate time window [10], some information is lost again. The “the size of the action potential” is much longer than the size of the neuron [44]. Even the result of the computation, a single output spike, may be issued before either of the input spikes was entirely delivered—one more reason why we should revisit the notion of information. As we discuss below, the information is spatially distributed (between input channels), has a hologram-like behavior (the information is reconstructed from several variable pieces), and it is delivered by the relative arrival times of the gradients of the front sides of the spikes.

3.2. Spiking

Similarly, definitions such as “Multiple neuromorphic systems use Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs) to perform computation in a way that is inspired by concepts learned about the human brain” [45] and “SNNs are artificial networks made up of neurons that fire a pulse, or spike, once the accumulated value of the inputs to the neuron exceeds a threshold” [45] are misleading. That review “looks at how each of these systems solved the challenges of forming packets with spiking information and how these packets are routed within the system”. In other words, the technically needed “servo” mechanism, a well-observable symptom of neural operation, inspired the “idea of spiking networks”. The idea lacks knowledge of information handling and replaces the (in space and time) distributed information content by well-located timestamps in packets, the continuous analog signal transfer by discrete packet delivering, the dedicated wiring of neural systems by bus-centered transfer with arbitration and packet routing, and the continuous biological operating time with a mixture of digital quanta of computer processing plus transferring time. Even the order of timestamps conveyed in spikes (not to mention the information they deliver) is not reminiscent of biology; furthermore, due to the vast need for communication, the overwhelming majority of the generated events must be killed [36] without delivering and processing them to provide a reasonable operating time and to avoid the collapse [46] of the communication system. In the rest of the aspects, such a system may provide an excellent imitation of the brain.

In addition to wasting valuable time with contenting for the exclusive use of the single serial bus, utilization of the bit width (and package size) is also inefficient. Temporal precision “encodes the information in the spikes and is estimated to need up to three bits/spike” [47]. The time-unaware timestamping of artificial spikes does not encode temporal precision given that the message comprises the sending time coordinate of the event instead of the relative time to a local synchrony signal (a base frequency); furthermore, the conduction time is not included in the message. Timestamping misses the biological method of coding information [6]. Moreover, it uses a central clock that is missing from biological systems [48].

3.3. Neuronal Learning

Biological neurons are data-controlled, and they learn autonomously: they adjust their synaptic sensitivity based on the timing relations of the data arriving at their inputs. On the contrary, one must train artificial neurons, typically using the back-propagation method; see [49] and our figures about bus transfer in [10]. During that operation, the program, which works in instruction-driven mode, supervises the learning process, performs computations, and sends its results through the network and the bus in opposite directions. That operations are not relevant for biology. In the figure, the directions of data transmission are opposite in the ‘forward’ and ‘backward’ directions, whereas time flows in only one direction. One should operate the feedback in the ‘backward’ direction when the computation in the ‘forward’ direction has already terminated (the time windows overlap [10,14], and they have no transfer time window between). Furthermore, the above restriction is also valid for the computations inside the layers.

3.4. Information Density

As discussed in [6], when sending messages with finite speed, the message comprises temporal and spatial components. The statement applies to both technical and biological computing. In technical computing, the temporal contribution is unintended and unwanted, so it is suppressed as much as possible by introducing clock domains and clock distribution times [10,14]. In biological computing, the arrival of a spike is only a synchronization signal (in line with Shannon, “if a source can produce only one particular message, its entropy is zero” [41]). The difficulties in deriving experimental conclusions are hard: “These observations on the encoding of naturalistic stimuli cannot be understood by extrapolation from quasi-static experiments, nor do such experiments provide any hint of the timing and counting accuracy that the brain can achieve” [50]. In biological systems, evidence shows that more than one bit (some guesses, see [47], ch. 6, suggest 3 bits) is transferred in a spike (modeled as a bit train). When the number of bits in messages can seriously change (and becomes significantly higher than one or two bits), the proportionality between the number of spikes and the conveyed information ceases.

An unwanted synergy between computing and neuroscience is the hypothesis that the information transfer and the phenomenon of ‘spiking’ (sending short identical pulses) are closely related. A study [50] investigated the connection between spike firing patterns and the visual information they convey. They experienced that “constant-velocity motion produces irregular spike firing patterns, and spike counts typically have a variance comparable to the mean”. In statistics, a significant variance indicates that the numbers in a set are far from the mean and from one another. In other words, in the actual case of a constant velocity, there is a very weak (if any) dependence between the number of spikes and the motion, clearly showing that some other parameter of the transferred signal delivers the information. The experimenters noticed this, and they looked for some other “more natural” case: “However, more natural, time-dependent input signals yield patterns of spikes that are much more reproducible”. Simulating nature-defined encoding is a real challenge, but human-encoding is also made complicated by human-made technical systems. As discussed in [6], presumably, in the “much more reproducible” scenario, the number of bits per spike in the analog component is much smaller than in the “less natural” case, so using a wrong merit function for the information meets experimenters’ (false) expectation much better.

The fallacy of selecting a wrong merit function leads directly to the conclusion [51] that “energy efficiency [of neural transfer] falls by well over 90%” (many other similar examples could be cited, but this one shows the mistake explicitly). By defining their measurement method—“We calculated the firing rate of the spiking neuron model”—and measuring “spikes/s” [50,52] (assuming that the neuron is a repeater and the spike carries on/off information), they draw a false parallel with electronic circuits.

4. Technical Aspects

One can separate the subject of simulating neural networks into two independent segments: what a model is that produces spikes (and what information the spikes convey) and how the system (principally and technically) takes the delivered information into account. The numerous enormous differences between technical and biological computing make the simulation of neural operation by technical means a real challenge. A fundamental issue is that the biological time of the events is not directly proportional to the computer processing time. Given that the processing time comprises computing time plus transfer time, timestamping cannot provide a solution for time handling. The timestamp records the clock time when an event happens in the computing process instead of its biological time. Given that several neurons share the computing resources, and the computer’s execution is sequential, the events happening at a biologically identical time will generate timestamps at different technical times. Furthermore, for the same reason, the generated event will be considered again at different times with a (technically random) delay compared to the time of generating those events and to each other. However, when using random weights and equalizing mathematical methods, the mentioned effects can hardly be seen. Furthermore, the propagation time through the axons (and so: the equivalent of biological learning) cannot be included. These effects are late consequences of omitting the transfer time in computing science.

4.1. Neural Connectivity

It is typical that several spikes arrive at a neuron, and only one spike is produced (although it branches toward several downstream neurons): “A single neuron may receive inputs from up to 15,000–20,000 neurons and may transmit a signal to 40,000–60,000 other neurons” [53]. “In the terminology of communication theory and information theory, [a neuron] is a multiaccess, partially degraded broadcast channel that performs computations on data received at thousands of input terminals and transmits information to thousands of output terminals by means of a time-continuous version of pulse position. Moreover, [a neuron] engages in an extreme form of network coding; it does not store or forward the information it receives but rather fastidiously computes a certain functional of the union of all its input spike trains, which it then conveys to a multiplicity of select recipients” [54].

In small-scale artificial neuronal networks, all neurons in a layer receive input from the neurons of the upstream layer and provide input for the downstream layer. In an extensive system, this method requires an enormous amount of communication actions. Algorithms 1 and 2 show how non-time-aware algorithms work (how they run on an abstract mathematical computer). The blue lines inserted into Algorithm 3 illustrate the usually neglected yet necessary and time-consuming implicit actions that were not considered in the algorithm design. When calculating algorithmic time, they are considered as zero-time contributions, but in real computing systems, they can become dominant. In small-scale (toy) systems, they can be neglected. As the system grows, performance saturates, as measurement [34,55] and theory [30,32] have shown.

| Algorithm 1 The basic clock-driven algorithm [56], Figure 1 |

|

| Algorithm 2 The basic event-driven algorithm with instantaneous synaptic interactions Figure 2 in [56] |

|

| Algorithm 3 The basic event-driven algorithm with non-instantaneous synaptic interactions, Figure 3 in [56] |

|

4.1.1. Queue Handling

Attempts to simulate spiking biological neural networks started early, and different types of simulation strategies and algorithms have been implemented; for an excellent review, see [56]. As experienced, the precision of those simulations sensitively depends on the applied strategies—in particular in cases where plasticity depends on the exact timing of the spikes. It was found that the appropriateness (or applicability) of some method or strategy sensitively depends on the given task. The analysis method can be followed for artificial spiking neural networks, too. The paper discusses the basic algorithms used to compute neural networks (notice that computing the individual neurons according to different models is not detailed).

We detail the calculation algorithm in a single node of the network, as it is the vital component of the correctness of the biological network. Given that “overall, it appears that the crucial component in general event-driven algorithms is the queue management” [56], we used the highly optimized queue handling of SystemC [29,38]. This way, we use at least one time event and at most one event per neuron in the queue. In most cases, however, servicing one event inserts one or more other events into the queue. An essential difference is that SNNs reduce the possible events to one (so they naturally cannot imitate the length of a neuronal action), while we have a sequence of (non-simultaneous) events per neuron. For SNNs, “Event-driven algorithms implicitly assume that we can calculate the state of a neuron at any given time in advance, i.e., we have an explicit solution of the differential equations”. Our approach is distinct: we employ a heartbeat-based calculation method that enables us to determine a neuron’s state at any given (discretized) time depending on the actual conditions. Our method is “spiking” in the sense that a neuron sends a message only when the calculation is complete (thereby minimizing communication). However, it is time-aware (operates on the actual biological time scale) at the cost of increased scheduling complexity. Of course, it can utilize single-shot operating neurons that correspond to step-like changes rather than slow processes.

- The two latter algorithms comprise a deadlock, as all neurons expect the others to compute their inputs (or work with values calculated in previous cycles, mixing “this” and “previous” values);

- After processing a spike initiation, the membrane potential is reset, excluding the important role of local neuronal memory (also learning);

- The algorithms are optimized for single-thread processing by applying a single event queue.

We must consider the conclusion [56] that “these results support the argument that the speed of neuronal simulations should not be the sole criterion for the evaluation of simulation tools, but must complement an evaluation of their exactness.” Following [56], we can assume that enqueue/dequeue operations of events can be performed relatively quickly; however, queue management remains a crucial component in general event-driven algorithms. Moreover, as the number of events in the queue grows, the hit ratio of finding an event in the cache quickly decreases. Given that the memory addresses of neurons found in the queue are “random” for the cache, data locality is not effective anymore, and practically, the processor can access all neuron data after a cache failure. The I/O operations are protected mode instructions, so a single I/O command must be accompanied by context switchings, there and back, with about 20,000 machine instruction offsets [57,58]. This offset is why “artificial intelligence, …it’s the most disruptive workload from an I/O pattern perspective.” (https://www.nextplatform.com/2019/10/30/cray-revamps-clusterstor-for-the-exascale-era/, accessed on 1 December 2025).

4.1.2. Limiting Computing Time

One must drop some result/feedback events because of long queuing to provide seemingly higher performance in excessive systems. The feedback the neuron receives provides a logical dependence that the physical implementation of the computing system converts to temporal dependence [14]. The feedback arrives later, so those messages stand at the end of the queue. Because of this, it is highly probable that they “are dropped if the receiving process is busy over several delivery cycles” [36]. In excessive systems, undefined inputs may cause the feedback to become unstable, and the system may ignore (perhaps correct) feedback. Another danger when simulating an asynchronous system on a system, using at least one single centrally synchronized component, introduces a hidden “clock signal” [32], which degrades the system’s computing efficiency by orders of magnitude.

The authors of [59] provide an excellent “experimental proof” of the statements above: “Yet the task of training such networks remains a challenging optimization problem. Several related problems arise. Very long training time (several weeks on modern computers, for some problems), the potential for over-fitting (whereby the learned function is too specific to the training data and generalizes poorly to unseen data), and more technically, the vanishing gradient problem”. “The immediate effect of activating fewer units is that propagating information through the network will be faster, both at training and test time.” The intention to compute feedback faster has its price: “As increases, the running time decreases, but so does performance.” Introducing the spatiotemporal behavior of ANNs improved the efficacy of video analysis significantly [60]. Investigations in the time domain directly confirmed the role of time (mismatching): “The Computer Neural Network (CNN) models are more sensitive to low-frequency channels than high-frequency channels” [61]. The feedback can follow slow changes with less difficulty than faster changes.

4.1.3. Sharing Processing Units

To speed up overall execution, several threads and cores share the task. The different computing times across cores and threads are unrelated to the biological scale, so the programmer divides the biological time into relatively short periods and forcefully stops the simulation in a given thread when the activity up to that biological time has been simulated. That means the threads must wait for each other at the “meeting points” and must mutually inform each other. This is accomplished by sending the relevant calculated result(s) to each other and receiving the results of other computing units as input parameters. This idea is the exact equivalent of the central clocking used by processors. Typically, a 1 ms “grid time” is used. As we discussed [32], the final result is using a very high-performance processor under the control of a very low-frequency (1 kHz) central clock. As experienced, the operating characteristics correspond to the theoretical expectations [30,31]. The system can load content into memory in linear time [62] (in this sense, as designed, “can simulate one billion neurons”). However, when those simulated neurons need to communicate, fewer than 80,000 can be operated on simultaneously. It means that at this special workload, the computing efficiency is less than . It is well understood theoretically [30,31] (the first observation and theoretical description is more than 3 decades old [63]) and it was also experimentally confirmed [33,55] that for such workloads, only a couple of dozen processors can be used efficiently. It is also known that limiting the number of communication messages, for example, to support real-time operation [61], decreases operational quality. In vast systems, collecting the data from all participating processors takes dozens of minutes [35].

After finding the data address, the instruction address must also be set appropriately (it is not certain that all neurons, at all times, execute the same code). Usually, several neurons share a processor core. As Ref. [36] estimated, about 10% of the computing capacity is used for administration, provided that once the core is scheduled, all neurons assigned to it compute without needing system-level rescheduling. This means that the relative non-payload contribution can be as good as 10/1000% if all cores are scheduled sequentially, but it can be as wrong as only one payload activity follows the expensive rescheduling operation. Experience shows that “small differences in spike times can accumulate and lead to severe delays or even cancellation of spikes, depending on the simulation strategy utilized or the temporal resolution within clock-driven strategies used” [56].

4.1.4. Pruning Connections

Communication, anyhow, tragically decreases the efficiency of computation also in large-scale neural networks (including brain simulation and ANNs). Grid-time-based computing results in sending and receiving messages regardless of whether a significant change occurs in the neuron’s state. The number of communication actions must be reduced, and the number of epochs (including scheduling) that require non-payload communication must be reduced. The most evident manifestation of biological operation—sending spikes to fellow neurons—inspired the creation of “spiking neural networks”. They target reducing messaging by limiting communication to a single message, which is sent by a neuron when it “fires”. The issue against the biological application of the idea is the content of the message: the information the spike delivers is the time when the effect of the environment (the fellow neurons) causes the neuron to fire. The time is the ‘clock time’ the sender stamps into the message, and the receiver can work out the message based on that time.

In neuroscience, it is known that although a neuron may have several thousand input axons, only about a dozen of them participate in integrating charge (see Equation (7)). Biology also applies pruning during the development of individuals [64,65].

In technical systems, pruning can be applied randomly, based on empirical utilization statistics of the connection line, or using predefined models (such as a Large Language Model (LLM)) based on theoretical assumptions on the targeted utilization. The idea of spiking networks is that only the neurons that have collected enough charge send a notification (a spike) to their downstream neurons. This idea reduces the communication traffic considerably, but it has ‘side effects’ in locality, as discussed. If the spikes carry timing information, the neuron can finish charge integration when sufficient charge has arrived to raise the membrane’s voltage to above the threshold level. This idea assumes that at the time of summing, all input spikes to be considered by a neuron are available as a time-ordered queue, so one can decide when the charge integration shall start and finish. After that time, at a fixed-time delivery offset, the neuron sends a message to its downstream neurons. The arrival time at the downstream neurons is composed of the event time, the delivery time, and the transfer time per connection line.

The time values are on the ‘clock time’ scale: the computer prepares the timestamp when executing the operation that caused exceeding the membrane’s threshold. Given that the time depends on the thread scheduler (and that up to 1000 neurons per core can be used), in a clock-based algorithm, the neurons send messages (spikes) at approximately the same time offset. When running an event-based algorithm, the non-payload activity is no longer uniform, thereby increasing the dispersion of spiking times and, consequently, reducing the temporal precision of information transfer.

When imitating biological processes, one needs to consider both the time at which the event can be “seen” in wet neurobiology (the biological time) and the time required for the computer processor to deliver the result corresponding to the biological event (computing time). Computing objects, intended to imitate biological systems, need to be aware of both time scales. As discussed above, in connection with the serial bus, the technical implementation may introduce enormously low payload computing efficiency and significantly distort the time relationships between computing and data delivery.

The passing of time is measured by counting some periodic events, such as clock periods in computing systems or spiking events in biological systems. In this event-based world, everything that happens between events occurs “at the same time”. However, the technical implementation (including the measurement of biological processes) may introduce another unintended granularity. The biological neurons perform analog integration; the technological implementations are prepared to perform “step-wise” digital integration. This step involves (mostly) losing phase information. Furthermore, as detailed in [32], it imposes severe limits on the payload performance for neuronal operations.

Furthermore, an issue is that the artificial neurons work “at the same time” (biological time) and they are scheduled essentially in a random way on the wall-clock time scale. Since the neurons integrate “signals from the past”, this method is not suitable for simulating the effects of spikes with a decay time comparable to the length of the grid time. In addition, this grid time is “making all cores likely to send spikes at the same time”, and [SpiNNaker] “does not cope well with all the traffic occurring within a short time window within the time step” [36]. This is why the designers of the HW simulator [66] say that the events arrive “more or less” in the same order they should. The difference in the timing behavior is also noticed by [36]: “The spike times from the cortical microcircuit model obtained with different simulation engines can only be compared in a statistical sense”.

In ANNs, the signals are delivered via a bus, and the interconnection type and sequence depend on many factors (ranging from the kind of task to the actual inputs). During training ANNs, their feedback complicates the case. The only fixed thing in timing is that the neuronal input inevitably arrives only after a partner has produced it (which also takes time). The time ordering of delivered events, however, is not certain: it depends on the technical parameters of delivery rather than on the logic that generates them. Timestamping cannot help much. There are two bad choices. Option one is that neurons should have a (biological) sending-time-ordered input queue and begin processing only after all partner neurons have sent their message. That needs a synchronous signal and leads to severe performance loss. Option two is that they have a (physical) arrival-time ordered queue, and they are processing the messages as soon as they arrive. This technical solution enables us to give feedback to a neuron that fired later (according to its timestamp) and set a new neuronal variable state, which is a “future state” when processing a message received physically later but with a timestamp referring to a biologically earlier time. A third, maybe better, option would be to maintain a biological-time ordered queue (that is what SystemC follows), and either in some time slots (much shorter than the commonly used “grid time”), send out output and feedback, individually process the received events, or send back feedback and output immediately. In both cases, it is worth considering whether their effect is significant (exceeds some tolerance level relative to the last state) and, if so, mitigating the need for communication in this way.

4.2. Hardware/Software Limitations

The processor time is shared between non-payload tasks, such as the operating system’s tasks [67], including context switching [57,58], as well as scheduling computing tasks and simulated units, and the payload tasks, which involve computing for simulating neuronal activity. For an illustration, we use a flagship project [36]. As published, approximately 10% of the time is spent on non-payload activity. As the calculation in [31] details, the time share and number of cores mean a computing efficacy of ; in other words, out of the cores, only 10 can contribute full-value computing performance. This result is in line with the results that (at slightly less demanding workloads) only a few dozen processors (out of several hundreds of thousands) can be effectively used for computation [33,34]—similarly to the case of large neural networks [30,55].

Based on theoretical expectations such as “The naïve conversion between Operations Per Second (OPS) and Synaptic Operations Per Second (SOPS) as follows: 1 SOPS ≈ 2 OPS” [68], and the ratio of their operating times (1 ns vs. 1 ms), it was designed that 1000 neurons share a processor core [36]. That is, in addition to thread scheduling (by the operating system), additional neuron scheduling must also take place (and take time) in the computing thread(s). In this way, much less than (on another scale: much less than one thousand machine instructions) can go for calculating the 1 ms activity of a neuron (a detailed consideration of the required computing cycles is given in [36]). If some neurons cannot complete the required flow of calculations, or if not all simulated neurons have a time slice, and if the computed result cannot be processed, the whole computation in the timeslot is (almost) useless. This is why, according to [36], “Each of these cores also simulates 80 units per core” (out of the designed 1000 units): when reducing the number of required context switchings, the core also has some time to perform payload calculations. The limitation is hard: “As a consequence of the combination of required computation step size and large numbers of inputs, the simulation has to be slowed down compared to real-time. Reducing the number of neurons to be processed on each core, which we presently cannot set to fewer than 80, may contribute to faster simulation” [36]. In other words, using fewer cores results in higher performance. After reaching a critical number of cores, the computing performance of many-processor systems starts to decrease, as observed earlier [63].

One of the significant drawbacks of the “grid time” method is that the time resolution (the “sampling rate”) cannot be shorter than the “grid time”; the “computing neurons” always send messages at that time whether they have or not a new state; the event time is quantized; and at the end of the “time grid” periods, “communication bursts” [46] happen: the achievable performance is severely limited [32]. In particular, the intense communication needed in vast systems can lead to communication collapse [46], limiting the number of collaborating units [36,69], pruning the connections by HW/SW methods [65,70,71] or simply omitting some events to speed up processing [36], apparently.

5. Biological Computing

Biological computing was created by nature without a user’s guide attached, so our basic difficulty is that “engineers want to design systems; neuroscientists want to analyze an existing one they little understand” [72]. We must never forget, especially when experimenting to imitate neuronal learning using recurrence and feedback, that “Neurons ensure the directional propagation of signals throughout the nervous system. The functional asymmetry of neurons is supported by cellular compartmentation: the cell body and dendrites (somatodendritic compartment) receive synaptic inputs, and the axon propagates the action potentials that trigger synaptic release toward target cells” [73]. We must recall the functional asymmetry and the networked nature (slow, distributed processing) when discussing the biological relevance of a method, such as backpropagation.

A neuron operates in tight cooperation with its environment (the fellow neurons, with outputs distributed in space and time). We must never forget that “the basic structural units of the nervous system are individual neurons” [17], but neurons “are linked together by dynamically changing constellations of synaptic weights” and “cell assemblies are best understood in light of their output product” [6,74]. A neuron receives multiple inputs at different times (at different offset times from the different upstream neurons) and in different stages. To understand the operation of their assemblies and higher levels, we must provide an accurate description of single-neuron operation.

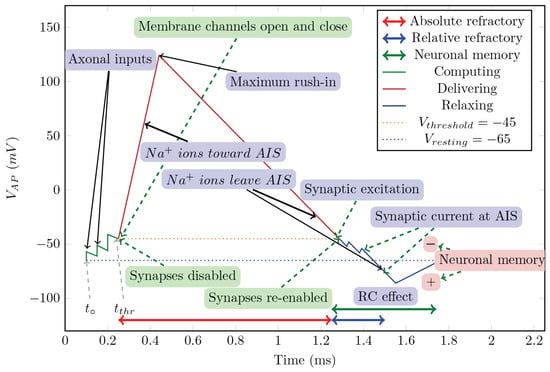

We generalized computing [14] and, furthermore, its closely integrated communication. Moreover, we extended the idea to biological operations. We abstract the operation as shown in Figure 1, present its mathematical description in Section 6.2, construct its state-diagram-like summary in Figure 2, describe some details of the algorithm in Section 6.3, and present the results of the calculation in Figure 3.

5.1. Conceptual Operation

We describe neuronal operation using its conceptual operating graph in Figure 1 and stage diagram in Figure 2. We use some biological concepts but omit unnecessary details. We subdivide the neuron’s operation into three stages (green, red, and blue sections of the broken diagram line) in line with the state machine in Figure 2. The continuous change (the presence of a voltage gradient) is fundamental for a biological computing system. The stages are, at another abstraction level, states with internal processes.

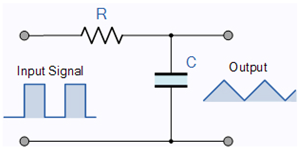

Our model incorporates the latest discoveries, including those related to the AIS. The neuron’s operation in the resting state resembles a parallel oscillator given that only the ion channels, which are embedded in the membrane’s wall, play a role in the electric operation. However, in the transient state, most of the current flows through the AIS, which is between the membrane and the axon and has much higher conductance, so the neuron resembles a serial oscillator [75]. Although those circuits comprise the same electric components, their electrical behavior is entirely different; see Table 1.

Table 1.

RC circuit types https://www.electronics-tutorials.ws/rc/rc-integrator.html (accessed on 1 December 2025).

Figure 1.

The conceptual graph of the action potential (Figure 10 from [10]).

Figure 2.

The model of a neuron as an abstract state machine (Figure 9 from [10]).

A neuron has a stage variable (the membrane potential) and a regulatory threshold value. Crossing the membrane’s voltage threshold value upward and downward causes a stage transition from “Computing” to “Delivering” and from “Delivering” to “Relaxing”, respectively. In the lack of external current contribution, the length of the period “Delivering” is fixed (entirely defined by physiological parameters), while the length of “Computing” depends on the activity of the upstream neurons (furthermore, on the gating due to the membrane’s voltage). Due to the finite speed, we discuss all operations in the neuron’s “local time”.

The cycle begins in the resting (ground) state [76] (it is a steady state with the membrane’s voltage at its resting value). Everything is balanced, and synaptic inputs are enabled. Due to an external perturbation, the neuron passes to a transient stage: “Computing”. When the membrane’s voltage exceeds its threshold, it passes into another transient stage, “Delivering”, and, by releasing the obsolete ions, it attempts to return to its resting stage. When the membrane’s voltage decreases below the threshold value, the neuron passes to the “Relaxing” stage, although its state variable has not yet been reset. The axonal inputs are reopened, which may mean an instant passing to the “Computing” stage again when new synaptic input arrives. The event that is issued when the stage “Computing” ends and “Delivering” begins separates two physically different operating modes: inputting payload signals for computing and inputting “servo” ions for transmitting (signal transmission to fellow neurons begins and happens in parallel with further computation(s)).

The loops “Leaking” means that independently from the stage, when the membrane potential is above the resting potential, a current (proportional to the voltage difference above the resting potential, see Equation (3)) flows and tends to restore the resting potential. However, no current flows (neither input nor output) in the resting stage; there is no (significant) “leakage current” assumed in the Hodgkin–Huxley model [77]. The time of the end of the operation is ill-defined and so is the value of the membrane’s voltage when the next axonal input arrives. The residual potential acts as a (time-dependent) memory with about a ms lifetime; see Figure 1. Notice that this is the way nature implements Analog In-Memory Computing (AIMC).

5.2. Stage Machine

Figure 2 illustrates our abstract view of a neuron, in this case, as a “stage machine”. The double circles are stages (states with event-defined periods and internal processing) connected by bent arrows representing instant stage transitions. At the same time, at some other abstraction level, we consider them as processes that have a temporal course with their event handling. Fundamentally, the system circulates along the blue pathway and maintains its state (described by a single stage variable, the membrane potential) using the black loops. However, sometimes it takes the less common red pathways. It receives its inputs cooperatively (controls the accepted amount of its external inputs from the upstream neurons by gating them by regulating its stage variable). Furthermore, it actively communicates the time of its state change (not its state as assumed in the so-called neural information theory) toward the downstream neurons.

5.2.1. Stage ‘Relaxing’

Initially, a neuron is in the ‘Relaxing’ stage, which is the ground state of its operation. In this stage, the neuron’s synaptic gates are open. (We also introduce a “Sleeping” (or “Standby”) helper stage, which can be imagined as a low-power mode [78] in the electronic or state maintenance mode of biological computing or “creating the neuron” in biology—a “No Payload Activity” stage). The stage transition from “Sleeping” also resets the internal stage variable (the membrane potential) to the value of the resting potential. In biology, a “leakage” background activity takes place: it changes (among others) the stage variable toward the system’s “no activity” value.

The ion channels generating an intense membrane current are closed. However, the membrane’s potential may differ from the resting potential. The membrane voltage plays the role of an accumulator (with a time-dependent content): a non-zero initial value acts as a short-term memory in the subsequent computing cycle. A new computation begins (the neuron passes to the “Computing” stage) when a new axonal input arrives. Given that the computation is analog, a current flows through the AIS, and the result is the length of the period to reach the threshold value. The local time is reset at the start of each computing cycle. Notice that the same stage control variable plays many roles: the input pulse writes a value into the memory (the synaptic inputs generate voltage increment contributions which decay with time, so the different decay times set a per-channel memory value while simultaneously the weighted sum is calculated).

5.2.2. ‘Computing’ Stage

The neuron receives its inputs as ‘Axonal Inputs’. For the first input in the “Relaxing” stage, the neuron enters the “Computing” stage. The time of this event is the base time used for calculating the neuron’s “local time”. Notice that to produce the result, the neuron cooperates with upstream neurons (the neuron gates its input currents). One of the upstream neurons opens computing, and the receiving neuron terminates it.

The figure also reveals one of the secrets of the marvelous efficiency of neuronal computing. The dynamic weighting of the synaptic inputs, plus adding the local memory content, happens analog, per synapse, and the summing happens at the jointly used membrane. The synaptic weights are not stored for an extended period. It is more than a brave attempt to accompany (in the sense of technical computing) a storage capacity to this time-dependent weight and a computing capacity to the neuron’s time measurement.

While computing, a current flows out from the neuronal condenser, so the arrival time of its neural input charge packets (spikes) matters. All charges arriving when the time window is open increase or decrease the membrane’s potential. The neuron has memory-like states [79] (implemented by different biophysical mechanisms). The computation can be restarted, and its result also depends on the actual neural environment and neuronal sensitivity. Although the operation of neurons can be described when all factors are known, because of the enormous number of factors and their time dependence (including ‘random’ spikes), it is much less deterministic (however, not random!) than the technical computation.

The inputs considered in the computation (those arriving within the time window), their weights and arrival times change dynamically between the operations. On the one hand, this change makes it hard to calculate the result; on the other hand, it is accompanied by the learning mechanism, it enables the implementation of higher-order neural functionality, such as redundancy, rehabilitation, intuition, association, etc. Constructing solid electrolytes enables the creation of artificial synapses [80], and many biological facilities in reach, with the perspective of having a thousand times faster neurons, provide facilities for coming closer to the biological operation.

The external signal triggers a stage change and simultaneously contributes to the value of the internal stage variable (membrane voltage). During regular operation, when the stage variable reaches a critical value (the threshold potential), the system generates an event that passes to the “Delivering” stage and “flushes” the collected charge. In that stage, it sends a signal toward the environment (to the other neurons connected to its axon). After that period, it passes to the “Relaxing” stage without resetting the stage variable. From this event on, the “leaking” and the input pulses from the upstream neurons contribute to its stage variable.

5.2.3. ‘Delivering’ Stage