Abstract

This paper presents a novel method based on a Hybrid Multi-Objective Evolutionary strategy for the automatic design of a lightweight convolutional neural network used for coronary stenosis classification. The hybrid methodology consists of two search stages, starting with the Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithm based on Decomposition, to generate a set of optimal solutions focused on the minimization of two objectives: the accuracy classification error and the number of learning parameters in the convolutional neural network. Subsequently, the Simulated Annealing algorithm is applied to improve a subset of the solutions produced in the previous step. After the method was complete, a convolutional neural network model consisting of 3498 learning parameters was found by the proposed hybrid strategy, which is a considerably low number compared with the other architectures reported in the literature. Consequently, the found model achieved the highest classification performance rate in terms of the Accuracy and Jaccard Similarity Coefficient metrics with values of and , respectively, using a database consisting of 608 images of regions with positive and negative coronary stenosis cases. On a second test, the model was tested using a database consisting of 2788 instances of natural and synthetic images of coronary stenosis cases. Corresponding maximum classification rates of and for the Accuracy and Jaccard Similarity Coefficient metrics, respectively, were achieved. In addition, the average required time to classify a single instance was seconds. The obtained results showed that the proposed method is feasible for the automatic design of lightweight convolutional neural networks that can be used as a part of decision-making systems in clinical practice.

1. Introduction

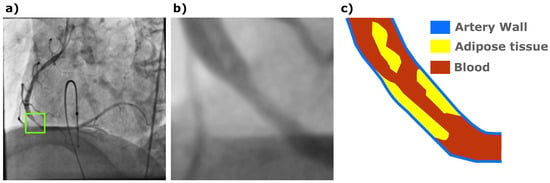

Coronary stenosis is a common disease which leads to heart attacks and eventually the death of patients, but it is not always accurately diagnosed by cardiology specialists [1]. X-ray tomography still remains the most widely adopted method to acquire coronary angiographies from patients with heart diseases [2]. However, the acquired X-ray coronary digital images are commonly low resolution with narrow regions or a low contrast of vessels and background, which makes it difficult for cardiologists to find affected arteries by an exhaustive visual image exploration. Figure 1 presents a coronary angiography involving a region with a stenosis case labeled by a cardiology specialist and a corresponding schematic representation.

Figure 1.

(a) A coronary angiography with a stenosis case labeled (green square) by a cardiology specialist. (b) The labeled region expanded. (c) A schematic representation of the corresponding coronary stenosis case.

Since the identification of coronary stenosis cases relies on the expertise and visual accuracy of cardiology specialists, to identify toxin or adipose tissue areas inside the arteries, the use of techniques and digital image processing methods is important to improve the detection of artery diseases. The automatic detection and classification of coronary stenosis cases from digital images of coronary angiographies have been reported in the literature using distinct approaches and methods. The use of feature extraction and machine learning classification techniques are some of the pioneer approaches [3]. For instance, the use of image processing techniques to enhance or segment arteries, which allows working with morphological features, has been used to differentiate healthy arteries from those indicating disease [4,5,6,7]. The combination of feature extraction and automatic feature selection techniques is also used to extract optimal feature subsets able to train specific classification machine learning models [8].

The problem has been also addressed by the use of deep learning techniques, which are a completely different approach when compared with manual feature extraction and machine learning techniques. The use of convolutional neural networks (CNN) for coronary stenosis detection and classification is the most common approach reported in deep learning-related literature [9,10]. One of main drawbacks of using traditional CNN architectures is the need for large image databases. This commonly leads to the use of highly complex CNN architectures, which could decrease its performance in terms of accuracy when small image databases are used for object detection or classification tasks [11]. To overcome the disadvantages of work with small image databases, the use of data augmentation and transfer learning techniques has been applied successfully. Despite the gains in classification accuracy provided by data augmentation, the absence of novel, empirical datasets poses challenges for clinical adoption [12,13]. In addition, as CNN architectural complexity increases, the difficulty of identifying the specific components most critical to the classification task scales accordingly [14].

The search for optimal CNN architectures is described in the literature as the Neural Architecture Search (NAS) problem. It is not a trivial task due to the high number of combinations that are possible to form with the distinct layer types. Furthermore, structural constraints must be addressed to prevent inconsistent layer connectivity or execution errors during the training phase. Beyond these constraints, representing CNN architectures across diverse structural formats—conforming to various computational techniques and algorithms—remains a significant challenge [15,16]. Consequently, numerous methodologies for the automated design of CNN models have emerged in the literature. For instance, Jiang et al. [17], utilize the Multi-Objective Particle Swarm Optimization along with the problem decomposition technique to generate CNN architectures. Similarly, Elsken et al. [18] propose a hill-climbing approach, which is validated using the CIFAR-10 image database [19]. More recently, Franco-Gaona et al. [20] employed an Estimation of Distribution Algorithm (EDA) to evolve optimal architectures for diverse image-processing tasks, including table detection and coronary stenosis classification. Parallel to these developments, substantial research has focused on the automated design of lightweight CNNs. Pham et al. [21] introduced a methodology for the creation of lightweight CNN architectures by optimizing inter-layer connections. Alternatively, proposals for the design of CNN architectures that are able to run on mobile and embedded devices with important hardware limitations have been reported [22,23]. The use of model compression techniques have been also applied to reduce the resource consumption cost of CNN models [24,25].

While CNNs have revolutionized medical image recognition, their application is significantly hindered by the scarcity of large-scale, annotated datasets. Unlike general-purpose image databases such as ImageNet, which served as the foundation for modern CNN architectures, medical databases often lack the volume and diversity required for robust training. In this context, high-complexity architectures including ResNet50 [26], InceptionV3 [27] and VGG-16 [28] yield suboptimal classification results when trained on limited image databases. Similarly, lightweight models such as MobileNetV2 [29] and EfficientNetB0 [30], despite their efficiency on large-scale image databases, exhibit a considerable decline in performance when applied to constrained medical image databases. Even when the use of transfer learning increases classification rates, there is a need to augment the original images because of large differences in the number of instances in which transfer learning is supported [31]. However, while data augmentation can be beneficial, some strategies could incorporate unrealistic variances or narrow relevant features that are critical to the analysis [32]. In addition, since data augmentation is a standard technique to improve model generalization, its application in medical imaging presents unique challenges that can compromise diagnostic integrity or violate critical data relationships [33,34].

This paper proposes a novel Hybrid Multi-Objective Evolutionary method to automatically design lightweight CNNs for classifying coronary stenosis cases. The use of multi-objective strategies such as the Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithm based on Decomposition (MOEA-D) [35] is relevant because it avoids the problem of assigning weights to the distinct goals involved. In addition, since the MOEA-D produces a set of trade-off solutions among the objectives involved, an additional search-refined stage driven by the Simulated Annealing (SA) method is performed [36]. In this stage, a subset containing the 3 best solutions achieved by the MOEA-D is extracted in order to perform a second search stage driven by the SA algorithm, which decreases the architecture complexity and, at the same time, tries to maintain or increase the classification accuracy.

The main contribution of this paper is a methodology that is able to automatically design lightweight specialized CNN architectures focused on the classification of positive and negative coronary stenosis cases using small image databases. It involves important design constraints to assure the creation of consistent CNN models. The proposed method conceptualizes the NAS problem as a multi-objective optimization problem with two goals: minimizing the classification error rate and the architecture complexity. A high classification accuracy is essential to guarantee the quality of the model architecture to be used in clinical practice. On the other hand, the use of a lightweight architecture is adequate to achieve optimal classification rates using small image datasets. In order to measure the classification rate, the Accuracy error metric was used during the training stage. Furthermore, to assure the obtained results, additional metrics such as Precision, Recall, F1-Score and Jaccard Similarity Coefficient were also used on posterior independent tests. In addition, the number of learning parameters was used as a complexity measure. For the experiments, two distinct image databases of coronary stenosis cases were used to confirm the obtained results. The first image database is composed of negative and positive coronary stenosis patches. On consecutive experiments, a second independent database, involving natural and synthetic images of coronary stenosis cases, was used. In the conducted tests, the proposed method performs better than the other compared techniques from the literature in almost all metrics. Finally, based on the presented results, the proposed methodology was adequate to produce CNN models that can be used in clinical practice as part of information systems for computer-aided diagnosis.

2. Background

2.1. Convolutional Neural Networks

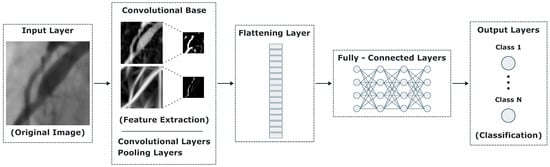

The convolutional neural network (CNN) is a deep learning technique which has been applied successfully in distinct types of problems involving image classification and object detection tasks [37]. CNNs are based on traditional artificial neural networks (ANNs), inheriting their learning capacity but with substantial differences. The ANN is a general-purpose model where every neuron is connected to every other neuron in the next layer. It was designed primarily for classification and pattern recognition tasks over plain data more than spatial information. In contrast, the input data on a CNN is formed by the original image information involving its size and pixel intensities in each color band. The accuracy of a CNN relies in its internal structure or architecture, which is formed by combining and linking distinct layer types. From a general perspective, a CNN model focused on classification tasks can be viewed as a three-component artifact. It starts with an input layer, followed by a set of internal layers, and it ends with an output layer which involves the distinct expected classes to produce a weighted value according to the most similar computed class. Figure 2 illustrates a top-level overview of a CNN model for classification tasks.

Figure 2.

Top-level overview of a CNN model for classification tasks.

The input layer corresponds to the pixel values of the original image, whose shape is a matrix of size , where w and h correspond to the image width and height, respectively, for a grayscale image. Consequently, for data processing and feature extraction, distinct layer types are used as described below.

- Convolution Layer. This is the core processing layer in a CNN. It is designed to perform the convolution operation, which in the spatial domain of a discrete image is expressed as follows in practical implementations:where I is the input image, K is the kernel expressed as a matrix of size , G is the convolution operation response, and correspond to the coordinates of the pixel in the image. Finally, m and n are the kernel K indices. The kernel height and width are defined as and , respectively.In the convolution operation, a small matrix (or filter) is slid over the original image to produce an output in which certain features are enhanced or segmented, depending on the kernel size and its values. In CNNs, the convolution layer is governed by four main parameters: the kernel size, the number of filters to be created, the stride size and the padding type. It is important to mention that the stride and the padding parameters are related and must be established coherently. Since the stride defines the step length in which the kernel is passed over the image pixels, the output size will be affected. For instance, if the input size in pixels is and the stride parameter is established with a value of 2, the output size will be . As a consequence, a padding of type ‘valid’ will not modify the output. However, if the padding value is established as ‘same’, the ouput image will have the original size filling with zeros around the output image.

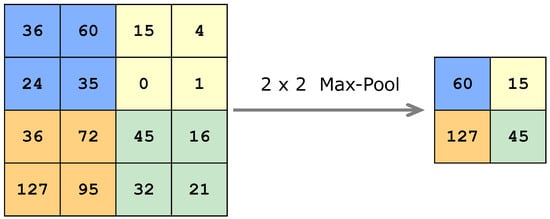

- Maxpooling Layer. A maxpooling layer is focused in the dimensional reduction of the input data by discriminating low values. Figure 3 illustrates how a maxpooling layer discriminates information from an input matrix to produce a new one of lower size.

Figure 3. Representation of the max-pooling operation. Colors are only representative for the groups of values that are considered for the dimensional reduction operation.

Figure 3. Representation of the max-pooling operation. Colors are only representative for the groups of values that are considered for the dimensional reduction operation. - Normalization Layer. Since the convolution layers produce outputs with out-of-range values, normalization layers rescale them into a valid range. In addition, normalized values help to accelerate the overall training process of the CNN [38].

- Rectification Layer. Rectification layers such as Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) and Leaky Rectified Linear Unit (LeakyReLU) are intended to introduce non-linear capabilities to the CNN. The main difference between ReLU and LeakyReLU layers is the way they manage negative input values. A ReLU layer will set negative values to zero. Otherwise, the output will be the same. This function is expressed as follows:where x is the value of each element in the input matrix or vector. On the other hand, the LeakyReLU layer transforms negative values into a small positive fraction of the input. The LeakyReLU is a less aggressive rectification method compared with ReLU, since neurons with zero value can be inactive permanently and are considered dead neurons. The LeakyReLU function can be expressed as follows:where is a small constant value, for instance .

- Flatten Layer. This layer flattens the input. If the input is a matrix of size , the flatten layer will convert it into a vector of 16 elements, as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Representation of a matrix flattening of size .Flatten layers are necessary in CNNs because they allow the CNN to be connected by dense layers.

Figure 4. Representation of a matrix flattening of size .Flatten layers are necessary in CNNs because they allow the CNN to be connected by dense layers. - Dense Layer. The dense layer or fully connected layer is an essential part of a CNN that will be used for classification purposes. This layer connects every one of its neurons with every neuron of the preceding layer. As a consequence, dense layers allow the learning of complex relationships and patterns.

2.2. Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithm Based on Decomposition

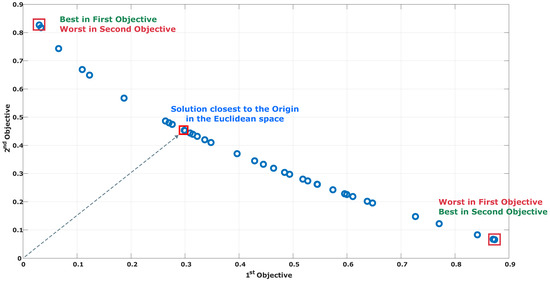

The Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithm based on Decomposition (MOEA-D) is a strategy focused on the search of solutions that accomplish distinct objectives simultaneously [39]. The MOEA-D decomposes a multi-objective problem (MOP) into a set of interconnected single-objective subproblems, which are solved simultaneously. A key difference from other multi-objective evolutionary strategies is the use of neighborhoods to create new populations instead of elitist selection mechanisms based on the Pareto dominance. The MOEA-D selects individuals from the closest neighborhood to each solution, and then traditional operators such as crossover and mutation are applied to create the individuals for the new population. Figure 5 illustrates the set of the best trade-off solutions produced by the MOEA-D, which was focused on the minimization of the ZDT1 function of Zitzler et al. [40] involving two objectives.

Figure 5.

Set of trade-off solutions produced by the MOEA-D in the minimization of the multi-objective ZDT1 problem.

An inherent trait in multi-objective optimization strategies is the generation of diverse solutions involving a trade-off among the objectives. The solution marked in a red square in the upper-left position of Figure 5 achieves the minimum value for the first objective with a high cost in the second one. In contrast, the solution marked in the red square at the bottom-right achieves the worst and best cost for the first and second objective, respectively. As a consequence, the solution that has the closest distance to the origin, in terms of the Euclidean definition, was found near the center of all the solution sets, which have equilibrated fitness values for the two involved objectives. The main strategy of the MOEA-D to solve multi-objective problems is the decomposition process, which decomposes the problem into a set of interconnected single-objective scalarized subproblems. The problem decomposition starts by defining a number N of weight vectors defined as follows:

where is the set of weight vectors , which are distributed over the solution space (that is formed the first time by evaluating the initial population). Consequently, each element corresponds to the solution (fitness value) for a unique subproblem whose scalarization can be computed using the Tchebicheff formula [41], which is expressed as follows:

where is the fitness value for a solution x, and is an ideal point for subproblem j computed as follows:

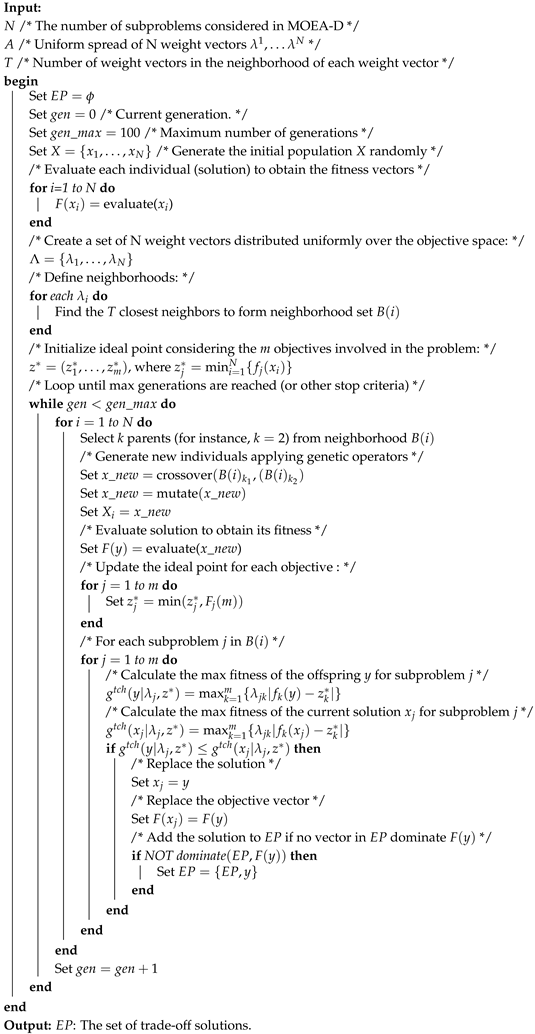

where . By applying the Equations (5) and (6), the MOEA-D pseudocode is described in detail in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: MOEA-D Pseudocode. |

|

2.3. Simulated Annealing

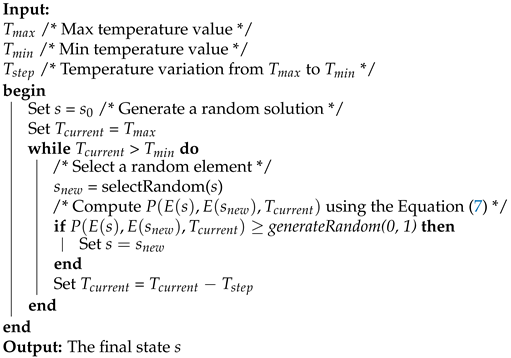

Simulated Annealing (SA) is a search strategy which was abstracted from the controlled cooling process used in metallurgy. SA starts with a temperature factor and an initial solution that will be transformed iteratively until the method ends. On each iteration, the temperature factor is decreased constantly, and it is used along with an energy difference value to compute an acceptance probability, which is computed as follows:

where T is the current temperature, and e and are the corresponding function objective values of the current and the new solution, respectively. The SA pseudocode is described in Algorithm 2.

| Algorithm 2: Simulated Annealing Pseudocode |

|

2.4. Performance Evaluation Metrics

The classification performance can be measured using distinct metrics which relies on the fraction of the four distinct results that can be obtained in a binary classification process:

- True Positive (TP): the number of instances that are classified as positive and correspond to real positive cases.

- True Negative (TN): the number of instances that are classified as negative and correspond to real negative cases.

- False Positive (FP): the number of instances that are classified as positive and correspond to real negative cases.

- False Negative (FN): the number of instances that are classified as negative and correspond to real positive cases.

By using the TP, TN, FP and FN classification results, different classification performance metrics such as Accuracy (Acc), Precision, Recall, Jaccard Coefficient of Similarity (JSC) and F1-Score can be computed as follows:

Additionally, the complexity of a CNN can be measured by its number of learning parameters. It is important to note that the complexity is related to the performance of a CNN in terms of hardware resources usage such as RAM, CPU/GPU, the required time for the training and classification stages, and the classification performance in terms of Accuracy or another metric [42].

3. Proposed Method

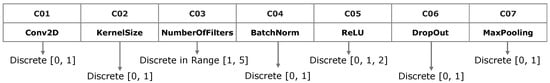

The proposed method involves two main stages related to the NAS problem. In the first stage, a set of solutions is produced by the MOEA-D strategy. Each solution is a trade-off between the error classification accuracy during the training and validation stages and the architecture complexity, which is measured using the number of learnable parameters of the CNN. In the second stage, a subset of optimal solutions, found by the MOEA-D, are selected and improved independently using the SA algorithm to finally select the optimal solution. The difficulty of designing an optimal CNN architecture is due to needing the correct number and combination of distinct layer types involving their own setup parameters. Since the multi-objective evolutionary algorithms such as the MOEA-D work with the concepts of individual and population, each solution (or individual) is represented as a vector of values considering the distinct variables involved in the problem. Therefore, a vector of 7 elements was used for the representation of a basic CNN architecture by considering the most common CNN layer types. Figure 6 illustrates the design approach used for the representation of distinct CNN layer types.

Figure 6.

Codification of distinct layer types of the CNN using a vector of 7 elements identified as cells to .

According to Figure 6, distinct CNN layers are represented as a vector of values requiring important considerations, which are described as follows. The first cell stores a discrete value to decide if a convolution layer will be present (1) or not (0). The second cell stores the convolution kernel size, which is constrained to sizes of if the value is 0 or otherwise [28]. Cell governs the number of convolution filters. The cell stores a discrete value in the range [1, 5] to generate the power of 2 values, which can be 2, 4, 8, 16 and 32 convolution filters [43]. Cell indicates if a normalization layer will be added (1) or not (0). Cell controls the activation and type of the rectified linear unit layer, where 0 means that a ReLu layer will not be added, 1 adds a ReLu layer, and 2 adds a LeakyReLU layer. Cell activates the addition of a dropout layer if the value is 1. If the value is 0, the dropout layer will not be added. Cell is a discrete value indicating if a maxpooling layer will be added (1) or not (0). The size of a pooling layer can be established arbitrarily. However, CNN architectures such as VGG and ResNet have demonstrated that applying a half uniform downsampling strategy produces optimal classification results, decreasing the computational load, memory and CPU/GPU resources [44].

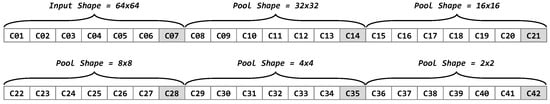

By considering distinct pooling sizes (, , , , and ), the previous structure can be repeated 6 times to form the full representation of the CNN architecture as a vector of 42 elements, as illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Codification of the full representation of a uniform downsampling CNN architecture using a vector of 42 elements.

In addition, several constraints were added to the architecture representation as follows. It was strategic to set the parameter stride of convolutional layers with a value of 2 in order to add stabilization and performance improvement [26,45]. Even when the CNN architecture representation is intended to decrease on each block of seven cells, the insertion of a pooling layer that downscales the inputs to subsequent layers depends on the activation of cells , , , and . If some of those cells are not active (has a value of 1), the inputs remain in the last downscale size from previous layers. In addition, cell does not have an effect on the process, but it is present to keep the CNN representation structure. This design strategy allows adding a diversity of solutions because the CNN architectures are not constrained to a single form. After a solution is produced, it is important to finish the CNN architecture by adding the corresponding flatten and dense layers, which are responsible for the classification task. Since the input of these layer types depends of the output of the previous layer, they were not considered as part of the solution representation.

Based on the representation described before, the proposed method for the NAS stage can be implemented accordingly. Figure 8 illustrates the hybrid multi-objective evolutionary method schema, which is focused on the automatic design of a lightweight CNN for the classification of positive and negative coronary stenosis cases.

Figure 8.

Proposed method steps for the automatic design of CNN architectures.

According to Figure 8, the hybrid metaheuristic starts with an initial CNN architecture search driven by the MOEA-D method, which returns a set of trade-off solutions known as the Pareto front. In step 2, a subset of N solutions is selected from the Pareto front to be improved. For this paper, we selected 3 solutions closest to the origin in terms of the Euclidean distance. In step 3, the SA algorithm is used to improve the previously selected solutions.

It is important to mention that since the SA method is single-objective, a solution is accepted as the best only if the two involved objectives (Accuracy classification error and number of learning parameters) are minimized simultaneously, which is equivalent to assigning a balanced weight to each of them. Finally, in step 4, the best solution (closest to the origin of the Euclidean space) is taken in accordance with the results obtained by the SA algorithm.

4. Results and Discussion

For the experiments, two distinct publicly available image databases of coronary stenosis cases were used. The first image database contains 608 images corresponding to regions of coronary angiograms, which were properly validated by cardiology experts [46]. Each image size is pixels. The number of positive and negative cases is 304 for each. Figure 9 illustrates a sample of 14 images containing positive and negative coronary stenosis cases.

Figure 9.

Image samples taken from the Stenosis608 [46] image database. The first row presents positive coronary stenosis cases. Consequently, the second row corresponds to negative coronary stenosis cases.

The second image database involves real and synthetic images corresponding to coronary stenosis regions [47]. The size of each image is pixels. Figure 10 illustrates a sample of 21 images containing natural and synthetic coronary regions of positive and negative stenosis cases.

Figure 10.

Image samples taken from the Antczak [47] image database. The first row contains natural images of coronary stenosis positive cases. The second row corresponds to synthetic images of positive cases. The third row corresponds to natural negative cases.

All the experiments were carried out on a computer with an Intel Core i7-9700K CPU with 3.60 GHz and 16 GB of RAM. It also contains an NVidia Titan RTX GPU with 24 GB of DDR6 VRAM, 4608 CUDA Cores and 576 Tensor Cores. The algorithms and search strategies were written in Matlab R2024a software.

For the NAS task, driven by the MOEA-D and the SA strategies, the Stenosis608 database was split using the holdout strategy with a proportion of 80–20% for training and testing, respectively. In addition, a cross-validation strategy with was used on the training stage. It is important to mention that only the training partition was used for the NAS process. In addition, the MOEA-D implementation is derived from the Kalami [48] code base. The corresponding setup parameters required for the MOEA-D and the CNN training are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Parameter values for the MOEA-D and CNN training, which are used in the first stage of the proposed method for the NAS process.

Consequently, for the second step, the value of N, which corresponds to the number of taken solutions from the Pareto front produced by the MOEA-D, was established as 3. The corresponding parameter values for the SA and the CNN training options are described in detail in Table 2.

Table 2.

Parameter values for the SA and CNN training, which are used in the second stage of the proposed method for the NAS process.

As described in Table 2, the number of epochs for the CNN models training was increased considerably due to the single-solution nature of the SA method. Consequently, it is important to mention that all of the previous parameter values were established as a trade-off between the required time to obtain a response and an adequate fitness value.

After the NAS stage was concluded, the results show that the hybrid approach improved almost all of the solutions for all of the metaheuristics, as described in Table 3.

Table 3.

Performance comparison in terms of accuracy and number of CNN learnable parameters for the Hybrid MOPSO, Hybrid NSGA-II and Hybrid MOEA-D algorithms. Data columns are related to the method name, the number of solutions, the number of initial learning parameters (ILPs) before the improvement step, the number of final learning parameters (FLPs) after the SA improvement step, the initial validation accuracy (IVA) before the improvement step, and the final validation accuracy (FVA) after the SA improvement step.

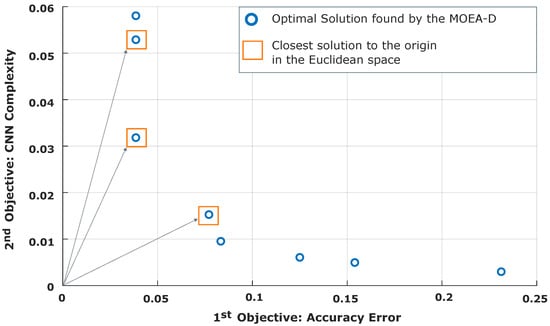

Based on data described in Table 3, the hybrid approach improves the CNN architecture in almost all cases. By comparing columns related with the initial learning parameters (ILPs) and final learning parameters (FLPs), there is evidence related to decreasing the number of learning parameters in almost all of the CNN models. However, due to the nature of the SA algorithm, in which the worst solutions are accepted in the first iterations and many goals are involved, the final result could be affected when an accepted solution improves only one of the goals. For instance, the solutions produced by the Hybrid MOPSO slightly improve the CNN complexity and the validation accuracy. However, its performance is below those of the other methods. Consequently, the first solution of the NSGA-II starts with a CNN architecture consisting of 1026 learnable parameters and a validation accuracy of . When the SA method ends, the number of parameters was improved because the value decreases to 646. In addition, the validation accuracy also decreases to instead of increasing or keeping the initial value. In contrast, the second solution found by the MOEA-D algorithm was improved considerably, since it started with 11,910 learnable parameters and a validation accuracy of . Once the SA algorithm concluded, the number of learnable decreased to 3438 and the validation accuracy increased to , indicating that the final solution improved the two goals simultaneously. To complement the previous data, Figure 11 illustrates the Pareto front found by the MOEA-D.

Figure 11.

Representation of the Pareto front involving the optimal solutions found by the MOEA-D.

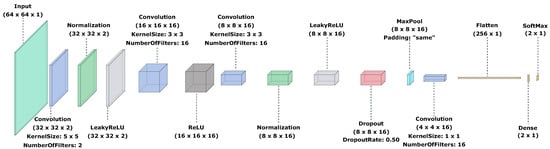

Figure 12 illustrates the CNN architecture for the best solution found by the proposed method.

Figure 12.

CNN lightweight architecture designed automatically by the proposed method based on the MOEA-D and the SA algorithm.

The CNN architecture found by the proposed hybrid evolutionary multi-objective method is formed by 15 processing layers plus the classification one. As illustrated in Figure 12, the resulting architecture makes use of all common layer types, starting with a convolution in the second layer, whose corresponding kernel size is . Because of the stride value, which was established in 2 as a constant, an initial input downscale is performed, transforming the input size of to pixels, increasing computational efficiency and showing that the selected strategy was adequate. Consequently, a normalization layer and leaky ReLU layers were added, respectively. The fifth layer type is a convolution layer with a kernel size of and 16 filters, which is followed by a ReLU layer. The seventh layer is of convolution type involving a kernel size of and 16 filters. At this point, and because of the fifth layer, the image data size was decreased to pixels. Layers 8, 9 and 10 correspond to normalization, leaky ReLU and dropout types, respectively. The eleventh layer is a maxpool with no padding to assure that all input pixels are covered (including edges) in the input feature map. The cost of this consideration is that the image size is not reduced. However, this behavior is compensated by the stride value in the convolution layers. The twelfth layer corresponds to a convolution using 16 filters. Because of the previous maxpool layer and the fact that in the last part, the maxpool size is , a kernel size of is used, which decreases the input size from to . The thirteenth layer transforms the input from the last layer, whose size is , to a data vector of 256 values. Consequently, a fully connected layer consisting of neurons (the number of classes) is added at the fourteenth position. Finally, an activation softmax, plus the classification layer, are added.

To assure model stability, the CNN architecture formed by each strategy was trained using 488 random images (≈80%) from the Stenosis608 image database. The remaining 120 instances (≈20%) were used for testing on a later step. In this test, only training images were involved, using a cross-validation with on 30 independent trials. The number of epochs was established in 1000 to perform an exhaustive training of the models to increase its reliability and efficiency in terms of the Accuracy metric. The corresponding results are described in Table 4.

Table 4.

Statistical analysis of the training performance in terms of the Accuracy metric and a cross-validation process with for the proposed method and distinct evolutionary-based methods on 30 independent trials, using 488 images from the Stenosis608 image database. In addition, the number of learning parameters for each model is described in the Learners column, which is expressed in units of millions (M) and thousands (K).

Based on data described in Table 4, the proposed method achieved the highest classification rates in terms of the Accuracy metric. However, there is evidence of the impact of multi-objective search strategies, since the number of learning parameters in the models decreases significantly to the order of thousands. Consequently, all models were stable, since the standard deviation of the classification accuracy was low for all cases. In order to measure reliability, the previous models were tested against additional classification metrics such as Precision, Recall, F1-Score and Jaccard Similarity Coefficient, as described in Section 2.4, using the trained model with the highest classification rate from the previous test. The corresponding results are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Comparison of classification performance rates achieved by the proposed method and distinct CNN models from the literature, using 120 testing instances from the Stenosis608 image database. The classification performance was measured in terms of the Accuracy (Acc), Precision (Pres), Recall, F1-Score (F1) and Jaccard Similarity Coefficient (JSC). Additionally, the number of learning parameters for each model is described in the Learners column and expressed in units of millions (M) and thousands (K).

According to the results presented in Table 5, there is evidence related to the effect of the solution improvement stage performed by the SA algorithm, in which some of the best solutions produced by the multi-objective techniques are taken and improved individually. However, even when some of the compared methods achieved high rates in metrics such as Accuracy, Recall and F1-Score, in clinical practice, they fail to accurately classify real positive disease cases, which is critical. As a consequence, the use of the Jaccard Similarity Coefficient metric was important, because it inflicts a high penalty to positive cases classified as negative (False Negatives). By considering this, the proposed method achieved the best classification results compared to the other methods.

To assure the reliability of the designed CNN architecture, a second test was performed using the Antczak image database, which contains natural and synthetic artery coronary stenosis images. For the first test, only natural images were considered, forming a dataset of 244 instances in a balanced way between positive and negative coronary stenosis cases. The dataset was split into 194 and 50 instances of training and testing, respectively. In Table 6, a statistical analysis of the training accuracy, based on the classification performance, is presented. Each model was trained using the cross-validation strategy with on 30 independent trials.

Table 6.

Statistical analysis of the training performance in terms of the Accuracy metric and a cross-validation process with for the proposed method and distinct evolutionary-based methods on 30 independent trials, using 194 natural images from the Antczak [47] image database. In addition, the number of learning parameters for each model is described in the Learners column, which is expressed in units of millions (M) and thousands (K).

Consequently, each architecture was tested by taking its corresponding model, which achieved the highest validation classification Accuracy in the previous test. The pretrained models were tested using the image testing partition consisting of 50 images. The obtained results are presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Comparison of classification performance rates achieved by the proposed method and distinct CNN models from the literature using the testing set, which consists of 50 images. The tests were performed using the the model with the maximum Accuracy rate on validation according to the previous statistical analysis. The classification performance was measured in terms of the Accuracy (Acc), Precision (Pres), Recall, F1-Score (F1) and Jaccard Similarity Coefficient (JSC) metrics. In addition, the number of learning parameters for each model is described in the Learners column and expressed in units of millions (M) and thousands (K).

Based on the results presented in Table 7, the proposed method achieved the highest rates in almost all metrics. It is difficult for complex CNN architectures to achieve correct training and classification rates with image databases having a low number of instances. Consequently, the design of lightweight CNN architectures was adequate because they achieve superior classification results with datasets containing a low number of instances. Finally, a dataset containing 2788 images was formed. Since the Antczak coronary stenosis database contains 1394 and 122 natural images corresponding to negative and positive cases, respectively, the database was equilibrated by adding 1272 synthetic images of positive cases using the author’s method to generate them. Similar to the previous test, the image dataset was split in a proportion of ≈80–20% for training and testing, which corresponds to 2240 and 548 images, respectively. Using the images from training partition, each model was trained using the cross-validation strategy with on 30 independent trials. Based on the obtained results in each trial, a corresponding statistical analysis is presented in Table 8.

Table 8.

Statistical analysis of the training performance in terms of the Accuracy metric and a cross-validation process with for the proposed method and distinct evolutionary-based methods on 30 independent trials. The training partition is used, which consists of 2240 images from the Antczak [47] image database, involving natural and synthetic coronary stenosis cases. In addition, the number of learning parameters for each model is described in the Learners column and expressed in units of millions (M) and thousands (K).

Based on the data presented in Table 8, the increase in the number of instances improved the training validation accuracy considerably for all CNN architectures. However, the CNN model found by the proposed method overpassed or was equal to the rest of them in all measurements.

According to the data described in Table 9, the CNN architectures produced by all the compared strategies increased their classification rate under all of the measured metrics. This is an important fact in traditional CNN architectures such as ResNet50 and VGG-16 because they tend to improve classification rates by increasing the size of the training image dataset. Consequently, lightweight models such as MobileNetV2 [29] and EfficientNetB0 [30] also increased on all classification metrics considerably, using the testing set. However, the proposed methodology, based on the MOEA-D and the SA methods, performs considerably better than the other compared techniques in all metrics, which provides evidence about the CNN model’s reliability when analyzing distinct coronary stenosis image databases.

Table 9.

Comparison of classification performance rates achieved by the proposed method and distinct CNN models from the literature using the testing set, which consists of 548 images. The tests were performed using the the model with the maximum Accuracy rate on validation according to the previous statistical analysis. The classification performance was measured in terms of the Accuracy (Acc), Precision (Pres), Recall, F1-Score (F1) and Jaccard Similarity Coefficient (JSC) metrics. In addition, the number of learning parameters for each model is described in the Learners column and expressed in units of millions (M) and thousands (K).

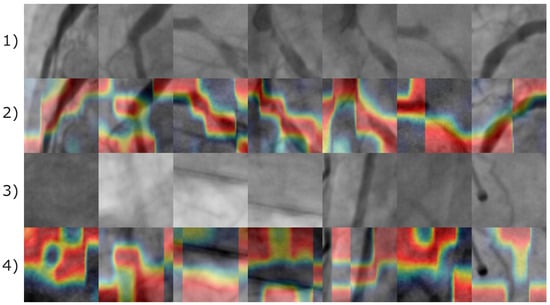

In order to explore details about the image features that allow the proposed CNN model to classify positive and negative coronary stenosis cases, the Grad-CAM technique was used [50]. Figure 13 presents distinct images from the Stenosis608 database, consisting of 21 positive coronary stenosis cases with relevant features marked in a heatmap by the Grad-CAM method.

Figure 13.

Image samples of the Stenosis608 image database. First and third rows illustrates the original images of positive and negative coronary stenosis cases, respectively. The second and fourth rows display the corresponding Grad-CAM heatmaps, where a color gradient from red to blue represents feature importance; red regions highlight the most influential features, while blue denotes areas of minimal contribution to the classification.

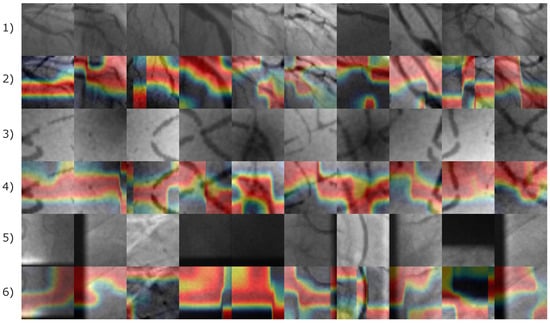

According to Figure 13, the image features leading the CNN model to produce a positive classification result are almost related to the pixels corresponding to arteries. Consequently, for negative stenosis classification results, the model involves features from arteries and non-artery pixels. In Figure 14, the corresponding Grad-CAM results from the Antczak image database are also presented.

Figure 14.

Image samples of the Antczak image database involving natural and synthetic images. The first row illustrates the original images of positive coronary stenosis cases. The second row illustrates the corresponding Grad-CAM heatmaps. The third and fourth rows illustrate the original and the corresponding Grad-CAM heatmap images for the synthetically generated instances of positive coronary stenosis cases. The fifth and sixth rows corresponds to natural images of negative coronary stenosis cases with their respective Grad-CAM heatmap. The heatmap is represented by a color gradient from red to blue denoting feature importance. Red regions highlight the most influential features, while blue denotes areas of minimal contribution to the classification.

Based on the images presented in Figure 14, the Grad-CAM shows evidence that artery pixels were also relevant to the identification of features related to positive coronary stenosis cases. Consequently, non-artery information form the image was relevant to the identification of negative coronary stenosis cases.

Finally, the required time for each stage of the experiments was interesting. For instance, in the initial search step, training a single solution consumed an average of ≈85 s: when multiplied by the number of individuals (50) and by the number of generations (100), the total required time was ≈5 days. For the second step, after the MOEA-D method produced the solution set, the SA takes ≈2.30 h to improve the best solutions found in the previous step. The required time in this step was considerably low when compared with the initial search step. Moreover, once the model is trained, the classification of a single image takes an average time of s, which is a considerably low value. In Appendix A, the corresponding Matlab code to build, train and perform a single test of the CNN architecture of the proposed method is presented.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, a novel method based on a Hybrid-Evolutionary Multi-Objective strategy for the automatic design of lightweight CNN architectures was presented. The main contribution is a methodology that can be applied for the automatic design of CNN models that are able to learn from small datasets without the need for data augmentation or transfer learning mechanisms. This aspect is relevant in distinct contexts such as medicine, where the image databases are scarce due to ethical and legal restrictions. The proposed method starts with an exhaustive search stage driven by the MOEA-D strategy over distinct combinations of layer types in order to produce an optimal CNN architecture. In the process, all produced models are validated to be coherent between the distinct layers that are added and connected. For instance, two consecutive ReLU layers did not improve the model, so the second was removed from the solution. Another type of inconsistency can occur if all of the convolution activation values of an encoded solution have a value of 0, which indicates the absence of convolution operations in the CNN model. In this case, the solution is corrected by adding a convolution layer. After the first stage of the search process concluded, the best solutions are selected from the Pareto front and improved independently using the SA algorithm. The hybrid approach produced a CNN architecture consisting of 15 layers and 3498 learning parameters, which is considered lightweight when compared with other such as ResNet50 or VGG-16 in which the number of learners is 25 and 138 million, respectively. As for the model architecture’s effectiveness, a public database consisting of 608 images corresponding to regions of coronary angiographies was used. In the test stage, we achieved classification rates of , , , and in terms of the Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-Score and Jaccard Similarity Coefficient, which achieved superior results to those of the other techniques from the literature. In a consecutive step, an independent image database consisting of natural and synthetic images was used to test the achieved model architecture. The test started using an image dataset of 244 instances, containing only natural images. The proposed method achieved classification rates of , , , and for Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-Score and Jaccard Similarity Coefficient metrics, respectively. In the last test, natural and synthetic images were used to form an image bank of 2788 instances. Using this image database, the CNN model achieved classification rates of , , , and under the same metrics. Moreover, once the model is trained, the required average time to classify a single image was seconds. The main disadvantage of the proposed method is the required time to achieve a solution. The NAS stage is very time consuming, considering that in the population-based search methods, each individual (solution) corresponds to a CNN architecture that must be trained independently. Regarding this point, it is important to mention that the proposed method is intended to work with small image databases, which is a common fact in medical context. Consequently, its use on large image databases could considerably increase the required time to produce an optimal result. Another disadvantage of the representation of CNN architectures in the proposed method is the design of only feed-forward architectures. As a consequence, future work could be focused on performing non-adjacent connections between the distinct layers of the model and implementing a strategy to decrease the required time during the NAS stage. However, according to the presented results, the proposed method could be applied in the automatic design of lightweight CNN architectures for other medical databases involving retina, chest, lung or other human organ images. Finally, based on the obtained results, it can be concluded that the proposed method can be applied to design lightweight CNN models to assist in clinical practice as a part of information systems for computer-aided diagnosis and decision-making support.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.-A.G.-R. and I.C.-A.; Formal analysis, M.-A.G.-R. and I.C.-A. and E.-G.G.-d.-P.; Investigation, A.H.-A. and E.-G.G.-d.-P.; Methodology, M.-A.G.-R., I.C.-A. and J.-M.L.-H.; Project administration, A.H.-A. and J.-M.L.-H.; Software, M.-A.G.-R., A.H.-A. and J.-M.L.-H.; Validation, M.-A.G.-R., I.C.-A. and E.-G.G.-d.-P.; Visualization, M.-A.G.-R., E.-G.G.-d.-P. and J.-M.L.-H.; Writing—original draft, M.-A.G.-R. and I.C.-A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Research images and achieved results are accessible at: https://github.com/mgil-utleon/lightweight_cnn_coronary_stenosis, accessed on 1 January 2026.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Centro de Investigación en Matemáticas A.C. along with the Instituto de Innovación, Ciencia y Emprendimiento para la Competitividad para el Estado de Guanajuato (IDEA GTO), under the project “Supercómputo como impulsor de colaboraciones Academia-Industria”; Universidad Tecnológica de León. This work was supported by SECIHTI under Project IxM-SECIHTI No. 3097-7185.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Acc | Accuracy Metric |

| Avg | Average |

| BatchNorm | CNN Batch Normalization Layer |

| EDA | Estimation Distribution Algorithm |

| IVA | Initial Validation Accuracy |

| Conv2D | CNN Convolution 2-D Layer for single color channel images |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| CPU | Central Unit Processing |

| F1 | F1-Score |

| FLP | Final Learning Parameters |

| FVA | Final Validation Accuracy |

| GA | Genetic Algorithm |

| GHz | Gigahertz |

| ILP | Initial Learning Parameters |

| JSC | Jaccard Similarity Coefficient |

| Max | Maximum |

| Min | Minimum |

| MOEA-D | Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithm based on Decomposition |

| MOPSO | Multi-Objective Particle Swarm Optimization |

| NAS | Neural Architecture Search |

| NSGA-II | Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm version 2 |

| Pres | Precision |

| RAM | Random Access Memory |

| ReLU | Rectified Linear Unit |

| SA | Simulated Annealing |

| StdDev | Standard Deviation |

Appendix A. Matlab Code for the CNN Model Obtained with the Hybrid MOEAD-SA Algorithm

The corresponding code is available at: https://github.com/mgil-utleon/lightweight_cnn_coronary_stenosis, accessed on 4 January 2020.

% Prepare the training dataset:

dir_training = ’path/to/your/training/dir/’;

dataset_training = imageDatastore(dir_training, ...

“IncludeSubfolders”, true, ...

“LabelSource”, “foldernames”);

% Split the training dataset for validation during training:

[imgs_train, imgs_val] = splitEachLabel(dataset_training, ...

0.9, ...

0.1, ...

’randomized’);

% Prepare the testing dataset:

dir_testing = ’path/to/your/testing/dir/’;

% Load an image to extract its size:

img = imread([dir_training, ’Positive/xyz_Positive.pgm’]);

image_size = size(img);

% Set the max train epochs:

max_train_epochs = 1000;

% Configure training parameters:

cnn_train_options = trainingOptions(’adam’, ...

’InitialLearnRate’, 0.001, ...

’MaxEpochs’, max_train_epochs, ...

’MiniBatchSize’, 16, ...

’Shuffle’, ’every-epoch’, ...

’ValidationData’, imgs_val, ...

’ValidationFrequency’, 30, ...

’Verbose’, true);

% Build the CNN model found by the proposed method:

cnnmodel=[

imageInputLayer(image_size), ...

convolution2dLayer(5, 2, ’Padding’, ’same’, ’Stride’, 2), ...

batchNormalizationLayer(), ...

leakyReluLayer(), ...

convolution2dLayer(3, 16, ’Padding’, ’same’, ’Stride’, 2), ...

reluLayer(), ...

convolution2dLayer(3, 16, ’Padding’, ’same’, ’Stride’, 2), ...

batchNormalizationLayer(), ...

leakyReluLayer(), ...

dropoutLayer(0.5), ...

maxPooling2dLayer([2, 2], ’Padding’, ’same’), ...

convolution2dLayer(1, 16, ’Padding’, ’same’, ’Stride’, 2), ...

flattenLayer(), ...

fullyConnectedLayer(2), ...

softmaxLayer(), ...

classificationLayer()

];

% Uncomment next line to show the full model information:

%analyzeNetwork(cnnmodel(1:numel(cnnmodel)-1));

% Train the CNN model:

[cnnmodel_trained, t_info] = trainNetwork(imgs_train, ...

cnnmodel, ...

cnn_train_options);

% Test the model with an image:

predicted_label = classify(cnnmodel_trained, img);

References

- Kay, F.U.; Canan, A.; Kukkar, V.; Hulsey, K.; Scanio, A.; Fan, C.; Hallam, K.A.; Gulsun, M.A.; Wels, M.; Schoebinger, M.; et al. Diagnostic accuracy of on-premise automated coronary CT angiography analysis based on Coronary Artery Disease Reporting and Data System 2.0. Radiology 2025, 315, e242087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasiou, L.S.; Fotiadis, D.I.; Michalis, L.K. Atherosclerotic Plaque Characterization Methods Based on Coronary Imaging; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhary, C.L.; Acharjya, D. Segmentation and Feature Extraction in Medical Imaging: A Systematic Review. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2020, 167, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessmann, M.; Vega-Higuera, F.; Fritz, D.; Scheuering, M.; Greiner, G. Multi-scale feature extraction for learning-based classification of coronary artery stenosis. In Proceedings of the Medical Imaging 2009: Computer-Aided Diagnosis; Lake Buena Vista, FL, USA, 7–12 February 2009, Karssemeijer, N., Giger, M.L., Eds.; International Society for Optics and Photonics, SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2009; Volume 7260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes-Sanchez, F.; Cruz-Aceves, I.; Hernandez-Aguirre, A. Automatic detection of coronary artery stenosis in X-ray angiograms using Gaussian filters and genetic algorithms. AIP Conf. Proc. 2016, 1747, 020005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sameh, S.; Azim, M.A.; AbdelRaouf, A. Narrowed Coronary Artery Detection and Classification using Angiographic Scans. In Proceedings of the 2017 12th International Conference on Computer Engineering and Systems (ICCES), Cairo, Egypt, 19–20 December 2017; pp. 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, T.; Feng, H.; Tong, C.; Li, D.; Qin, Z. Automated identification and grading of coronary artery stenoses with X-ray angiography. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2018, 167, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil-Rios, M.A.; Cruz-Aceves, I.; Hernandez-Aguirre, A.; Moya-Albor, E.; Brieva, J.; Hernandez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Solorio-Meza, S.E. High-Dimensional Feature Selection for Automatic Classification of Coronary Stenosis Using an Evolutionary Algorithm. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, S. Convolutional Neural Networks for Medical Image Processing Applications, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, L.; Deng, Y.; Chen, Y.; Luo, Y. Accuracy of deep learning in the differential diagnosis of coronary artery stenosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. Imaging 2024, 24, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maji, P.; Mullins, R. On the Reduction of Computational Complexity of Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. Entropy 2018, 20, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chlap, P.; Min, H.; Vandenberg, N.; Dowling, J.; Holloway, L.; Haworth, A. A review of medical image data augmentation techniques for deep learning applications. Med. Imaging Radiat. Oncol. 2021, 65, 545–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcea, F.; Serra, A.; Lamberti, F.; Morra, L. Data augmentation for medical imaging: A systematic literature review. Comput. Biol. Med. 2023, 152, 106391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdoch, W.J.; Singh, C.; Kumbier, K.; Abbasi-Asl, R.; Yu, B. Definitions, methods, and applications in interpretable machine learning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 22071–22080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Xue, B.; Zhang, M.; Yen, G.G.; Tan, K.C. A Survey on Evolutionary Neural Architecture Search. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2023, 34, 550–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Y.; Zhou, T.; Liu, L.; Xia, C. Automatic Convolutional Neural Architecture Search for Image Classification Under Different Scenes. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 38495–38506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Han, F.; Ling, Q.; Wang, J.; Li, T.; Han, H. Efficient network architecture search via multiobjective particle swarm optimization based on decomposition. Neural Netw. 2020, 123, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsken, T.; Metzen, J.H.; Hutter, F. Simple And Efficient Architecture Search for Convolutional Neural Networks. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1711.04528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A. Learning Multiple Layers of Features from Tiny Images. 2009. Available online: https://www.cs.utoronto.ca/~kriz/learning-features-2009-TR.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Franco-Gaona, E.; Avila-Garcia, M.S.; Cruz-Aceves, I. Automatic Neural Architecture Search Based on an Estimation of Distribution Algorithm for Binary Classification of Image Databases. Mathematics 2025, 13, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, H.; Guan, M.; Zoph, B.; Le, Q.; Dean, J. Efficient Neural Architecture Search via Parameters Sharing. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning; Stockholm, Sweden, 10–15 July 2018, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research; Dy, J., Krause, A., Eds.; PMLR: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; Volume 80, pp. 4095–4104. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, A.; Sandler, M.; Chu, G.; Chen, L.C.; Chen, B.; Tan, M.; Wang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Pang, R.; Vasudevan, V.; et al. Searching for MobileNetV3. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Chen, B.; Pang, R.; Vasudevan, V.; Sandler, M.; Howard, A.; Le, Q.V. MnasNet: Platform-Aware Neural Architecture Search for Mobile. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 16–20 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Chen, K.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, B.; Yao, L.; Jensen, C.S. Design Automation for Fast, Lightweight, and Effective Deep Learning Models: A Survey. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2208.10498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafiz, A.M. A Survey on Light-Weight Convolutional Neural Networks: Trends, Issues and Future Scope. J. Mob. Multimed. 2023, 19, 1277–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szegedy, C.; Liu, W.; Jia, Y.; Sermanet, P.; Reed, S.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Vanhoucke, V.; Rabinovich, A. Going deeper with convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1409.1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandler, M.; Howard, A.; Zhu, M.; Zhmoginov, A.; Chen, L.C. MobileNetV2: Inverted Residuals and Linear Bottlenecks. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1801.04381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q.V. EfficientNet: Rethinking Model Scaling for Convolutional Neural Networks. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1905.11946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovalle-Magallanes, E.; Avina-Cervantes, J.G.; Cruz-Aceves, I.; Ruiz-Pinales, J. Transfer Learning for Stenosis Detection in X-ray Coronary Angiography. Mathematics 2020, 8, 1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirichenko, P.; Ibrahim, M.; Balestriero, R.; Bouchacourt, D.; Vedantam, S.R.; Firooz, H.; Wilson, A.G. Understanding the detrimental class-level effects of data augmentation. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2023, 36, 17498–17526. [Google Scholar]

- Stacke, K.; Eilertsen, G.; Unger, J.; Lundström, C. A Closer Look at Domain Shift for Deep Learning in Histopathology. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.11575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, D.C.; Walker, I.; Glocker, B. Causality matters in medical imaging. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, H. MOEA/D: A multiobjective evolutionary algorithm based on decomposition. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2007, 11, 712–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, S.; Gelatt, C.D.; Vecchi, M.P. Optimization by simulated annealing. Science 1983, 220, 671–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeCun, Y.; Boser, B.; Denker, J.S.; Henderson, D.; Howard, R.E.; Hubbard, W.; Jackel, L.D. Backpropagation Applied to Handwritten Zip Code Recognition. Neural Comput. 1989, 1, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Cao, X.; Liang, H.; Huang, W.; Chen, Z.; Li, Z. New Interpretations of Normalization Methods in Deep Learning. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2020, 34, 5875–5882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, A.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, G. A multiobjective evolutionary algorithm based on decomposition and probability model. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation, Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 10–15 June 2012; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitzler, E.; Deb, K.; Thiele, L. Comparison of Multiobjective Evolutionary Algorithms: Empirical Results. Evol. Comput. 2000, 8, 173–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, Y.; Aranha, C.; Sakurai, T. Dynamic adaptation of decomposition vector set size for MOEA/D. In Proceedings of the GECCO’21: Genetic and Evolutionary Computation Conference Companion, Lille, France, 10–14 July 2021; pp. 181–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Yan, L.; Hou, Z.; Lin, J.; Zhao, Y.; Ji, Z.; Wang, Y. Error Analysis Strategy for Long-Term Correlated Network Systems: Generalized Nonlinear Stochastic Processes and Dual-Layer Filtering Architecture. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 33731–33745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Cui, J.; Li, Z.; Jiao, S.; Jiajia, L. CUTHERMO: Understanding GPU Memory Inefficiencies with Heat Map Profiling. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.18729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, A.; Aamir, M.; Mohd-Nawi, N.; Arshad, A.; Riaz, S.; Alruban, A.; Dutta, A.K.; Almotairi, S. A Comparison of Pooling Methods for Convolutional Neural Networks. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost-Tobias, S.; Dosovitskiy, A.; Brox, T.; Riedmiller, M. Striving for Simplicity: The All Convolutional Net. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1412.6806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Rios, M.A.; Cruz-Aceves, I.; Hernandez-Aguirre, A.; Hernandez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Solorio-Meza, S.E. Improving Automatic Coronary Stenosis Classification Using a Hybrid Metaheuristic with Diversity Control. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antczak, K.; Liberadzki, Ł. Stenosis Detection with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the MATEC Web of Conferences, Mallorca Island, Spain, 14–17 July 2018; EDP Sciences: Ulis, France, 2018; Volume 210, p. 04001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalami-Heris, M. MOEA/D in MATLAB. 2015. Available online: https://la.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/fileexchange/52873-multi-objective-evolutionary-algorithm-based-on-decomposition-moea-d (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Deb, K.; Pratap, A.; Agarwal, S.; Meyarivan, T. A fast and elitist multiobjective genetic algorithm: NSGA-II. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2002, 6, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraju, R.R.; Cogswell, M.; Das, A.; Vedantam, R.; Parikh, D.; Batra, D. Grad-CAM: Visual Explanations from Deep Networks via Gradient-Based Localization. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2019, 128, 336–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.