1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic irrevocably altered the global work landscape, marking a significant shift worldwide toward computer-based occupations. Remote work became the norm, increasing dependence on digital platforms and substantially extending daily screen time. While this transformation ensured business continuity, it also introduced new health concerns, particularly those related to prolonged sedentary behavior and suboptimal ergonomic conditions [

1]. The transition to work-from-home (WFH) environments exacerbated posture-related health risks. Extended sitting hours in improvised home offices have been linked to a range of medical complications, including chronic back and neck pain, musculoskeletal disorders, and reduced respiratory efficiency. Studies have shown that poor posture can result in [

2]:

Musculoskeletal Disorders: Imbalances due to poor posture may lead to repetitive strain injuries and spinal misalignment.

Respiratory Issues: Slouched sitting compresses the thoracic cavity, reducing lung capacity and impairing breathing.

Circulatory Problems: Prolonged immobility hinders blood flow and increases the risk of deep vein thrombosis.

Metabolic Concerns: Sedentary lifestyles contribute to metabolic syndrome, including obesity, insulin resistance, and hypertension.

Addressing these risks requires both medical interventions and preventive strategies. Physical therapy, chiropractic care, and occupational therapy provide clinical solutions, while ergonomic workstations, frequent movement breaks, and wearable posture devices represent preventive measures. Fundamental to these solutions is maintaining a correct sitting posture—keeping feet flat on the ground, knees and elbows at 90 degrees, spine supported, and the head aligned vertically above the shoulders [

3]. In recent years, artificial intelligence (AI) and computer vision have emerged as powerful enablers for automated ergonomic assessment, offering non-invasive and continuous posture detection capabilities that traditional solutions often lack. Such technologies facilitate early identification of unhealthy posture patterns and support user awareness in real time [

4].

To address these posture-related challenges in digital work environments, this study introduces ALIGN—an IoT-enabled intelligent system designed for real-time sitting posture detection. ALIGN integrates a camera sensor and a single-board computer to enable continuous posture assessment from side-view video input. The captured video stream is processed using machine learning and deep learning algorithms trained to classify sitting postures as correct or incorrect. When sustained improper posture is detected, the system generates visual and auditory alerts to notify the user and support posture awareness.

The system is designed to operate in real time and can support posture awareness in decentralized or hybrid work environments. The use of an Internet of Things (IoT) architecture enables scalable deployment and supports data collection for future analysis, without requiring wearable sensors. Beyond individual posture detection, ALIGN contributes to broader goals in workplace ergonomics and preventive digital health. By enabling timely identification of posture-related risks, the system aligns with the principles of Healthcare 4.0 and intelligent human–machine interaction.

The main contributions of this research are summarized as follows:

- 1.

Development of ALIGN, an IoT-integrated real-time sitting posture detection system combining camera-based sensing and embedded processing.

- 2.

Implementation and comparative evaluation of multiple machine learning (KNN, SVC, MLP) and deep learning (ResNet52, 20-layer CNN, DenseNet121) models for binary posture classification.

- 3.

Adoption of standardized training and evaluation procedures, including early stopping and consistent hyperparameter tuning, using performance metrics such as accuracy, F1-score, and ROC-AUC.

- 4.

Confusion-matrix-based analysis to examine classification behavior and model-specific strengths and weaknesses.

In summary, ALIGN demonstrates the effective integration of artificial intelligence, deep learning, and IoT technologies for real-time sitting posture detection. The proposed system offers a scalable and non-invasive solution for posture assessment in modern work environments.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 reviews relevant literature on posture detection and vision-based ergonomic assessment.

Section 3 outlines the proposed ALIGN architecture and processing pipeline.

Section 4 describes the dataset curation process, including data acquisition, labeling strategy, and preprocessing.

Section 5 presents the modeling framework, encompassing both traditional machine learning classifiers and deep learning architectures.

Section 6 reports the experimental evaluation and comparative results. Finally,

Section 7 summarizes the findings and outlines directions for future research.

2. Related Work

Posture detection has received considerable attention in recent years due to the growing interest in health-aware computing and workplace ergonomics. Research efforts have primarily focused on enhancing the accuracy, adaptability, and real-time performance of posture detection systems through the integration of machine learning (ML), deep learning (DL), computer vision, and sensor-based technologies [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. This section presents a thematic review of existing approaches, highlighting key advancements and identifying gaps that motivate the development of the proposed ALIGN system.

Various DL architectures have been employed for human pose estimation and 3D joint localization. In one line of work, multilayer neural network cascades were utilized to estimate full-body 3D pose with high accuracy [

11]. Similarly, deep pose estimation models have been proposed for predicting biomechanical load on lower back joints during physical activity, demonstrating the potential of DL techniques in posture-related strain analysis [

12]. Multimodal approaches have also been explored, where body pose is analyzed alongside facial features using multitask manifold learning, enabling more comprehensive assessments [

13]. Such advancements underline the versatility of deep architectures in modeling spatial and contextual dependencies that are central to posture understanding.

Hybrid systems that combine ML and DL techniques have been shown to improve classification robustness and interpretability. For instance, a fusion of deep neural networks with conventional classifiers has resulted in improved posture classification performance in complex environments [

14]. In another approach, body part segmentation and parsing-based strategies were surveyed for enhancing the granularity of human pose interpretation [

15]. These hybrid strategies demonstrate that integrating shallow and deep learners can enhance modularity and interpretability—two attributes essential for deployable posture detection systems.

Real-time posture awareness through alert-based feedback mechanisms has also gained traction. Smart fitness systems and wearable-based devices capable of issuing auditory or vibrational alerts upon detecting improper alignment have been proposed [

16,

17]. In parallel, computer vision systems have been developed for skeletal pose grading and yoga posture assessment through contrastive feature learning [

18,

19,

20,

21]. The introduction of multimodal alerting cues, including visual, auditory, and haptic signals, has proven effective in increasing user awareness of postural deviations. These studies emphasize the importance of timely and context-aware detection in posture-related applications.

Several studies have leveraged OpenPose and similar frameworks for ergonomic assessment and pose normalization. Open-source systems have demonstrated promise in assessing occupational ergonomics, especially in tasks involving seated posture evaluation and workplace activity analysis [

22,

23]. Techniques for joint coordinate normalization have also been proposed to improve pose estimation accuracy across individuals and environments [

24]. Despite these advances, many open-source frameworks rely on high computational resources or cloud-based inference, limiting their suitability for embedded or low-power IoT deployments.

Sensor-based approaches represent another key direction in posture research. Wearable systems have been implemented to track lumbar spine posture during athletic activity, such as competitive swimming, or to assess body alignment in yoga practice [

18,

25]. In many cases, data from inertial sensors have been integrated with ML models to support continuous posture detection. Bayesian network modeling and two-stage classification architectures have been explored to enhance robustness under diverse physical conditions [

18]. Nevertheless, wearable systems often face challenges related to comfort, calibration drift, and user adherence, motivating the need for camera-based, non-contact posture detection alternatives.

Comprehensive surveys have synthesized the state of the art in 2D and 3D human pose estimation, covering a wide range of DL techniques and architectural advancements [

26]. These works provide essential taxonomies and performance benchmarks that inform the algorithmic choices and evaluation strategies of newer posture detection systems. However, relatively few studies have addressed the deployment of these architectures on resource-constrained, IoT-enabled platforms capable of real-time posture detection at the edge.

In summary, significant progress has been made in posture estimation through the integration of vision-based techniques, wearable sensing, and hybrid learning methods. However, existing approaches often lack modularity or suitability for real-time inference in decentralized, IoT-enabled environments. Building upon these insights, the present work introduces a modular, real-time posture detection framework that synthesizes the strengths of computer vision, ML/DL algorithms, and embedded IoT infrastructure.

3. Proposed Approach for Real-Time Posture Detection

This study proposes an integrated approach based on computer vision and machine learning for real-time sitting posture detection. The methodology comprises multiple primary stages that collectively contribute to the development of a robust and accurate posture classification system. These stages include problem definition, mathematical modeling, dataset construction, machine learning-based classification, and deep learning-based evaluation, as detailed below.

3.1. Problem Definition

The objective of the proposed framework is to enable real-time classification of sitting posture using visual input. The system operates on a continuous RGB video stream captured from a side-view camera. Each incoming video frame is processed to extract pose landmarks through computer vision-based pose estimation. From these landmarks, geometric descriptors—namely horizontal offset, neck inclination, and torso inclination—are computed to quantitatively characterize upper-body posture. These descriptors are represented as numerical feature vectors and are used to train classical machine learning models, while the corresponding RGB frames are retained to construct an image-based dataset for deep learning models. The output of the framework is a binary classification decision for each processed frame, indicating whether the observed sitting posture is classified as correct or incorrect. Formally, the posture detection task addressed in this work is defined as a binary classification problem that maps each incoming RGB video frame to a posture label (True for correct posture, False for incorrect posture), while higher-level feedback is generated only when the False label persists across a predefined number of consecutive frames.

- 1.

A robust mathematical model is introduced to quantify sitting posture using anatomical landmarks extracted via computer vision techniques. This model captures geometric relationships—such as angles and relative alignments—between key body points, including the hip, shoulder, and ear, and serves as the foundation for posture annotation and supervised learning.

- 2.

An extensive dataset is constructed comprising both numerical and image-based samples. The numerical dataset is generated by applying the mathematical model to recorded posture instances, each labeled as correct or incorrect. In parallel, RGB images of individuals exhibiting various seated postures are collected and annotated accordingly, enabling multimodal training and evaluation. This dual representation allows the framework to exploit both geometric precision and visual contextual information for posture classification.

- 3.

Classical machine learning algorithms, including Support Vector Machines (SVM) and k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), are applied to the numerical dataset. Following preprocessing and feature normalization, the models are trained and evaluated with respect to their ability to accurately classify sitting posture. Hyperparameter tuning is performed to improve generalization capability. This stage establishes a computationally efficient baseline suitable for deployment in resource-constrained environments.

- 4.

Deep learning techniques are applied to the image-based dataset, with architectures such as Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs) and convolutional neural networks employed to learn discriminative visual patterns associated with sitting posture. These models are evaluated and benchmarked against classical approaches to assess differences in classification accuracy and robustness. Convolutional layers are explored to capture spatial dependencies and enhance visual feature representation.

Any posture configuration that does not simultaneously satisfy the predefined neck and torso inclination thresholds is deterministically assigned to the Incorrect Posture class.

During deployment, the above components are integrated into a real-time processing loop in which each incoming frame is classified independently. When an incorrect posture decision persists for a predefined number of consecutive frames, the system triggers an alert to notify the user of sustained postural deviation. This design supports continuous posture monitoring and user awareness while avoiding explicit posture correction instructions or ergonomic recommendations.

This multi-stage framework effectively combines computer vision, traditional machine learning, and deep learning, leveraging both geometric and visual data to deliver a comprehensive solution for posture evaluation. The modular structure of the proposed approach facilitates scalability and enables future integration with additional sensing modalities, such as inertial or depth sensors, thereby extending system adaptability. Applications of this framework span healthcare monitoring, workplace ergonomics, fitness assessment, and occupational safety, where real-time posture detection is critical for awareness and prevention.

3.2. Mathematical Modeling of Posture

A mathematical model is proposed to formalize the evaluation of upper-body posture through geometric analysis of key anatomical landmarks. The model relies on three primary body points—the hip, shoulder, and ear—identified using computer vision-based pose estimation. These landmarks define two vectors: , extending from the hip to the shoulder, and , extending from the shoulder to the ear.

Figure 1 illustrates the vector-based geometric model used to compute posture alignment. The angle

between these vectors quantifies the relative alignment of the torso and neck and serves as a measurable criterion for classifying posture as correct or incorrect.

The coordinates of the body landmarks are defined as follows:

Hip:

Shoulder:

Ear:

The vectors are computed using vector subtraction:

The angle

between vectors

and

is calculated using the dot product:

This model allows dynamic configuration of angular thresholds, accommodating individual anatomical variability while maintaining biomechanically meaningful alignment criteria [

27,

28]. Empirically, upright sitting postures are typically associated with angles in a narrow range (e.g.,

–

), whereas forward-leaning or slouched postures yield smaller values of

, enabling straightforward rule-based annotation.

3.3. Keypoint Extraction Using MediaPipe Pose

Keypoint extraction constitutes a foundational step in vision-based posture assessment, as it enables the identification of anatomical reference points required for evaluating postural alignment. In the proposed framework, landmarks corresponding to the shoulder, hip, and ear are used to represent upper-body posture and to detect deviations associated with non-upright sitting.

In this work, the MediaPipe Pose framework is employed for pose estimation. It provides high-precision landmark detection using BlazePose, which extends standard COCO keypoints by offering a total of 33 anatomical landmarks. From these landmarks, a subset of six keypoints is selected for tracking in a side-view configuration, enabling reliable estimation of torso and neck orientation [

29]. The resulting angular measurements are compared against a vertical reference axis to assess postural alignment. This targeted landmark selection minimizes computational overhead while preserving sufficient accuracy for upper-body posture estimation.

To ensure reliable real-time posture detection, the system processes side-view RGB video frames captured under natural seating conditions. MediaPipe Pose achieves inference rates ranging from approximately 8 to 60 frames per second (FPS), depending on the underlying hardware. Empirical evaluation showed that a processing rate of at least 10 FPS is sufficient to provide stable and responsive posture classification. The proposed implementation operates efficiently on single-board computing platforms, confirming its suitability for deployment in embedded IoT environments.

The adoption of a side-view camera configuration does not constrain the user’s natural ability to rotate the head; rather, it reduces perspective distortion in the sagittal plane, ensuring that hip–shoulder–ear angular relationships remain geometrically meaningful. In cases of pronounced head rotation or forward inclination, the resulting landmark configuration leads to increased deviations in neck inclination, which are consistently classified as incorrect posture according to the geometric model described above.

By leveraging the robust keypoint tracking capabilities of MediaPipe Pose, the framework ensures stable and reliable landmark localization as the foundation for downstream machine learning and deep learning stages. Accurate landmark detection directly affects posture classification accuracy and the consistency of user alerts. In side-view configurations, the ear landmark may visually appear near the cheek region due to 2D projection effects; nevertheless, the framework consistently relies on the hip–shoulder–ear triplet for geometric computation, even when certain landmarks are not explicitly rendered in the real-time visualization.

4. Dataset Preparation

To ensure the effectiveness of the proposed posture detection framework, careful dataset preparation was undertaken for both machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) models. Using keypoints extracted with MediaPipe, two complementary datasets were constructed: one numerical (for ML) and one image-based (for DL). In summary, the classical ML models operate on compact numerical feature vectors explicitly derived from geometric relations between anatomical landmarks, whereas the DL models are trained directly on the corresponding posture images resized to a fixed resolution. Both datasets are generated within the same acquisition and labeling pipeline and are produced synchronously at the frame level, ensuring that numerical features and images correspond to identical posture instances. This one-to-one correspondence guarantees consistent labeling and enables a fair and controlled comparison between ML- and DL-based learning paradigms.

The ML dataset comprises structured numerical data encoding coordinates of anatomical landmarks such as the hip and neck. By applying the mathematical model introduced in

Section 3.2, inclination angles are computed from the side-view camera perspective and stored in Comma-Separated Values (CSV) format. Each record is annotated with a binary label (True or False), indicating correct or incorrect posture based on predefined angular thresholds. The use of automatically derived geometric features ensures label consistency and reduces subjectivity during annotation.

In parallel, an image-based dataset is prepared for DL models. These images are extracted from video frames, and each is labeled in accordance with the mathematical model’s outputs. Unlike ML models, which use precomputed features, DL models learn directly from the spatial patterns in these labeled images, enabling the discovery of more complex posture-specific features. This complementary dual-dataset design enables both interpretable (angle-based) and end-to-end (image-based) learning paradigms within the same experimental framework.

The complete algorithmic pipeline for dataset creation is illustrated in

Figure 2. The workflow begins with library imports including OpenCV for video input, MediaPipe for pose keypoint extraction, and additional modules for CSV handling, geometry, and image storage [

30]. A PoseDetector class was implemented, encapsulating the system logic. It includes methods for computing distances, angles, and alignment offsets, as well as CSV writing and visual feedback generation. This modular implementation ensures that the same data processing pipeline can be seamlessly reused for both offline training and online inference.

For each processed frame, once a posture label has been determined, the corresponding numerical feature vector and RGB frame are stored within the same processing cycle. Although these operations are executed sequentially at the software level, they are logically paired, ensuring that every stored image has a directly matching feature vector. This design eliminates ambiguity regarding data synchronization and clarifies that the notion of “simultaneous” data generation in the pipeline refers to semantic, rather than parallel, processing.

Each incoming frame is preprocessed and analyzed for postural alignment using a reference offset. If the posture meets the alignment and inclination criteria, the frame is labeled as True (correct posture), and both the numerical and image data are saved. Otherwise, it is marked as False and stored in the corresponding directories. Frames are processed at 10 frames per second, providing sufficient temporal granularity for capturing subtle postural changes without data redundancy.

This dual-format dataset enables supervised learning for both ML and DL models. The approach ensures high-quality, balanced, and consistently labeled data that supports reliable real-time classification in practical deployments. All collected data were anonymized and captured in controlled indoor environments under consistent lighting conditions to ensure ethical and technical validity.

Figure 3 depicts how the system captures, analyzes, and labels sitting postures using RGB input and keypoint-based inference.

The curated dataset consists of approximately 50,000 labeled samples (30,000 correct and 20,000 incorrect postures). Each instance includes geometric features such as offset, neck inclination, and torso inclination, along with a binary label. Descriptive statistics reveal a mean offset of 115.5 with a standard deviation of 26.28, while inclination values span a broad range, indicating substantial postural variability and supporting model generalization.

Figure 4 presents the distributions of these features across the dataset, illustrating characteristic clustering patterns and variability across posture classes.

To further examine the data’s internal structure, dimensionality reduction techniques such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) were applied [

31]. These are visualized in

Figure 5. Such exploratory visualizations help assess the separability of postural classes before classifier training and confirm the consistency of extracted features.

Although the feature space is already low-dimensional, PCA and t-SNE are not employed here as preprocessing steps for model training. Instead, they are used exclusively for exploratory visualization, enabling qualitative inspection of class separability, cluster structure, and overlap between correct and incorrect posture instances. In all cases, the input to PCA and t-SNE consists of three-dimensional feature vectors computed for each frame, providing a compact and physically interpretable representation of sagittal-plane sitting posture.

The PCA projection reveals moderate separability between correct and incorrect posture classes, while t-SNE shows significant local structure and overlapping clusters. A silhouette score of 0.3038 suggests that meaningful class boundaries exist, providing a solid basis for learning. These observations justify the subsequent use of both linear (e.g., SVM) and nonlinear (e.g., MLP, CNN) models in our comparative evaluation.

With its breadth, label consistency, and statistical richness, the dataset offers a robust foundation for developing accurate, real-time posture classification models using both ML and DL techniques.

5. Modeling Framework: Machine Learning and Deep Learning Approaches

This section presents the complete modeling framework adopted for binary sitting posture classification, integrating both classical machine learning (ML) methods and modern deep learning (DL) architectures. The objective is to systematically examine the trade-offs between lightweight, interpretable models and higher-capacity neural networks in capturing the geometric and visual cues that distinguish correct from incorrect posture. Classical ML models—including K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), and Support Vector Classifier (SVC)—are evaluated primarily for their computational efficiency and interpretability. In parallel, three deep learning architectures—a custom 20-layer Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), ResNet52, and DenseNet121—are assessed for their representational power and scalability when operating directly on image data. The following subsections describe the modeling assumptions, theoretical foundations, architectural choices, and training strategies employed for each approach. All models were trained and evaluated on the same balanced dataset described in

Section 4, using standardized preprocessing procedures and systematic hyperparameter optimization to ensure a fair, controlled, and reproducible comparison across methods.

5.1. Machine Learning-Based Approaches

Machine learning techniques offer an effective means of posture classification when compact and informative feature representations are available. In this work, ML algorithms such as K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), and Support Vector Classifier (SVC) are employed to classify sitting posture as correct or incorrect based on geometrically derived features. Each posture instance is represented by a low-dimensional feature vector constructed from geometric descriptors—offset, neck inclination, and torso inclination—computed from MediaPipe pose landmarks and normalized prior to training.

Throughout this section, the input to all classical machine learning models is denoted by the feature vector , defined as . This compact, low-dimensional representation captures the dominant sagittal-plane characteristics of sitting posture and provides a computationally efficient yet discriminative input for real-time posture classification.

Each selected algorithm offers complementary strengths: SVC provides robust decision boundaries in low- to moderate-dimensional spaces, MLP enables nonlinear decision modeling with controlled complexity, and KNN offers an intuitive instance-based baseline. Collectively, these models support the development of an interpretable and computationally efficient classification pipeline suitable for real-time ergonomic monitoring.

5.1.1. Support Vector Classifier

The Support Vector Machine (SVM) is a supervised learning algorithm designed to identify an optimal separating hyperplane between two classes by maximizing the margin between them [

32]. In this study, SVM is employed in its soft-margin formulation with a Radial Basis Function (RBF) kernel to accommodate nonlinear separability in the posture feature space.

The decision function is defined as:

where

denotes the weight vector,

the input feature vector, and

b the bias term.

The optimization problem is expressed as:

subject to

where

are slack variables,

are class labels, and

C controls the margin–error trade-off.

To handle nonlinear decision boundaries, the RBF kernel is used:

where

is a parameter controlling the kernel’s spread and

is the Euclidean distance between data points

and

. Grid search with five-fold cross-validation was employed to optimize

C and

, balancing bias and variance.

5.1.2. Multi-Layer Perceptron

The Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) is a feedforward neural network composed of fully connected layers capable of modeling nonlinear relationships in the input space [

33]. In the proposed framework, the MLP serves as an intermediate solution between strictly linear classifiers and deep convolutional models, offering nonlinear modeling capacity with moderate computational cost.

A perceptron unit computes a weighted sum of its inputs followed by a non-linear activation:

where

are input features,

are associated weights,

b is the bias, and

is an activation function such as ReLU or Sigmoid.

In the case of an MLP with one hidden layer, the computations are:

where

and

are the weight matrices for the hidden and output layers, respectively, and

,

are the bias vectors. The model is trained via backpropagation using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001. ReLU is applied in hidden layers to address vanishing gradients, while the sigmoid function is used in the output layer for binary classification. Dropout regularization (

) was incorporated to prevent overfitting and improve generalization on unseen postures. This model structure is grounded in foundational work on multilayer perceptrons [

34].

5.1.3. K-Nearest Neighbors

K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) is a non-parametric, instance-based learning algorithm. It classifies a new instance based on the majority label of its

k nearest neighbors in the training set [

35,

36].

The Euclidean distance between two points

x and

in

n-dimensional space is given by:

The predicted class label is assigned based on majority voting among the

k neighbors. In our work,

was selected through cross-validation. Euclidean distance was used due to its consistency with the t-SNE projections of the dataset [

37]. Before training, all features were standardized to zero mean and unit variance, ensuring distance metrics remained scale-invariant.

While KNN is intuitive and effective, it suffers from computational inefficiency on large datasets and is sensitive to irrelevant features. To mitigate these limitations, feature scaling and dimensionality reduction techniques (such as PCA and t-SNE) were applied prior to classification.

5.2. Deep Learning-Based Approaches

Posture detection has experienced a substantial advancement with the adoption of deep learning, which provides robust models capable of extracting fine-grained patterns from large visual datasets. At the core of these advancements are Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), particularly effective in processing spatial hierarchies. In this work, we utilize a custom-designed 20-layer CNN and integrate two established architectures: ResNet52 and DenseNet121, to assess their efficacy in classifying human posture [

38,

39].

Unlike the classical ML approaches, deep learning models are trained exclusively on raw RGB posture images resized to pixels. No pose keypoints or handcrafted geometric descriptors are used as input, allowing these models to learn posture-relevant features in an end-to-end manner directly from visual data.

This separation between feature-engineered ML models and end-to-end DL models enables a clear methodological comparison, highlighting the relative contribution of explicit geometric modeling versus implicit visual representation learning.

These deep networks exploit hierarchical feature learning, where early layers detect low-level features (edges, gradients), and deeper layers abstract high-level structures (limb alignments, joint orientation). The 20-layer CNN is tailored for this application, while ResNet52 addresses gradient vanishing using residual learning, and DenseNet121 leverages dense connectivity for efficient feature reuse. The following subsections detail the theoretical foundations, architecture, and results of each model.

5.2.1. Convolutional Neural Networks

The custom 20-layer CNN was developed to capture the detailed nuances of human posture in image data. The architecture is composed of a sequence of convolutional, activation, pooling, normalization, and fully connected layers. These layers are designed to learn spatial hierarchies of features—from low-level textures in early stages to complex postural patterns in deeper stages [

40]. The network uses small

kernels, batch normalization after each convolution, and ReLU activations, with a final sigmoid output layer producing binary probabilities.

The foundational operation of a CNN is the convolution, which in the continuous domain is defined as:

This operation measures the overlap between a function

f and a shifted, flipped version of a kernel

g, which helps detect specific patterns across the input. In the discrete 2D case, applicable to image processing, the convolution becomes:

where

denotes the pixel value at position

in the input image, and

K is the kernel or filter applied to the image. The filter slides spatially across the input to produce feature maps that highlight key patterns such as edges or corners.

To introduce non-linearity into the network, the Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation function is applied after each convolution:

This simple yet powerful function accelerates convergence by preserving positive activations and zeroing out negatives, effectively allowing the network to model complex, non-linear relationships.

To reduce spatial dimensions while retaining critical features, pooling layers—typically max pooling—are used:

where

S is the set of values within the pooling window. This operation reduces computational complexity and enforces translational invariance.

Training stability and speed are improved using Batch Normalization, which normalizes the outputs of a layer across the mini-batch:

where

is the activation,

is the batch mean,

is the batch variance, and

is a small constant for numerical stability. Batch normalization also acts as a mild regularizer, complementing dropout layers used later in the network.

To mitigate overfitting, dropout regularization is employed. Dropout randomly disables a fraction p of neurons during training, which forces the network to learn more robust features by preventing co-adaptation of neurons.

The high-level features extracted through the convolutional layers are then passed to one or more fully connected layers. These layers perform the final classification by computing a weighted sum of inputs:

where

are the features,

are the corresponding weights,

b is the bias term, and

is the activation function—typically softmax for multi-class classification or sigmoid for binary tasks. The model was trained using the binary cross-entropy loss function and optimized with Adam at a learning rate of

.

Each design choice in this architecture—from kernel size to dropout rate—was empirically tuned to ensure optimal performance on the posture classification task. The overall structure of the network reflects a balance between depth and regularization, enabling it to distinguish subtle variations in postural alignment with high accuracy.

5.2.2. Residual Networks

Residual Networks (ResNets) introduced a significant advancement in deep learning by addressing the vanishing gradient problem, which often hampers the training of very deep neural networks [

41]. The core idea is to allow information to skip one or more layers through identity shortcut connections, forming what are known as residual blocks. This design principle enables deeper architectures to converge faster and achieve better generalization.

In a traditional deep network, each layer attempts to learn a desired mapping

. In contrast, ResNets reformulate this as learning the residual function

, which leads to the layer output being:

where

x is the input to the residual block,

is the residual function parameterized by weights

, and

y is the output. This formulation allows gradients to flow directly through the skip connections during backpropagation, making it possible to train much deeper networks without degradation in accuracy.

When the dimensions of

x and

differ, a linear projection

is applied to match dimensions:

This enables the shortcut path to still function when dimensionality changes due to convolutional strides or filter increases. In ResNet52, the network is composed of several such residual blocks, each containing sequences of batch normalization, ReLU activation, and convolution operations.

Each residual block typically contains two or three layers, structured as:

where BN denotes batch normalization, ReLU is the activation function, and

,

represent convolutional layers. Global average pooling replaces traditional fully connected layers, further reducing parameter count and mitigating overfitting. This layered structure enables ResNets to learn identity mappings more easily and preserve important low-level features through the depth of the network.

ResNet52, used in this study, stacks these residual blocks in a deep configuration to facilitate hierarchical feature learning. Its design is particularly well-suited for visual tasks like posture detection, where subtle variations in body alignment must be learned and preserved across many layers. The architecture is modular, scalable, and robust to the degradation problems seen in earlier deep CNNs.

5.2.3. Dense Convolutional Networks

Dense Convolutional Networks (DenseNets) represent a significant advancement in deep learning architecture by introducing dense connectivity between layers. Unlike traditional CNNs where each layer has connections only to its immediate predecessor, DenseNets connect each layer to every other preceding layer in a feed-forward fashion [

42]. This facilitates maximum information flow between layers and promotes parameter efficiency.

Formally, for a network with

L layers, each layer

l receives as input the concatenation of all feature maps from previous layers:

where

denotes the concatenation of the feature maps, and

is a composite function typically consisting of batch normalization, a ReLU activation, and a 3 × 3 convolution:

This design has several key advantages for deep visual learning tasks such as posture classification:

Feature Reuse: By concatenating all previous feature maps, each layer has access to the full knowledge accumulated up to that point. This allows early visual cues (e.g., edges or outlines) to remain accessible in deeper layers, which is particularly beneficial in tasks requiring fine-grained analysis.

Improved Gradient Flow: The dense connectivity ensures that gradients can flow directly to earlier layers during backpropagation, alleviating the vanishing gradient problem and stabilizing training.

Parameter Efficiency: DenseNets require fewer parameters than traditional CNNs because redundant feature maps are avoided. Layers do not need to relearn the same patterns, reducing overfitting risks.

Implicit Deep Supervision: Since each layer receives signals from the loss function through many paths, it is effectively supervised during training, making optimization easier.

DenseNet121, used in this study, consists of dense blocks interleaved with transition layers that include 1 × 1 convolutions and 2 × 2 average pooling operations to compress feature maps and control complexity. Each dense block contains multiple composite layers of the form described in Equation (

7), with growth rate

k determining how many new feature maps each layer adds. The network’s compactness and ability to reuse low-level features make it a natural fit for posture classification, where subtle geometric cues recur across samples.

This architecture is especially appropriate for posture detection where both global postural structure and fine local deviations must be preserved and interpreted across layers. The reuse of features and improved gradient dynamics make DenseNet a theoretically strong candidate for this classification task.

6. Experimental Evaluation

This section presents a detailed experimental evaluation of the proposed posture classification framework. Both traditional machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) models were assessed under a common protocol: stratified train/validation/test splits with a fixed random seed, standardized preprocessing, and early stopping for DL models. Hyperparameters for ML models were selected via GridSearchCV. Performance is reported in terms of classification accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and ROC-AUC. The evaluation is structured in two parts: the first examines the performance of lightweight ML models, while the second analyzes the behavior and effectiveness of deeper neural architectures. Additionally, confusion matrices and training dynamics are provided to offer deeper insight into model reliability, generalization, and convergence behavior.

To ensure methodological transparency and reproducibility, all reported metrics are computed on the held-out test set using the same class mapping throughout this section, where True denotes correct posture and False denotes incorrect posture. Unless otherwise stated, precision, recall, and F1-score are reported in a class-wise manner (per posture category), while ROC-AUC is computed from the corresponding model scores and summarized as a single scalar value for comparison.

6.1. Evaluation of Machine Learning Models

To establish a performance baseline for the proposed posture classification framework, three machine learning algorithms were evaluated: K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Support Vector Classifier (SVC), and Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP). Each represents a distinct modeling approach—KNN relies on local neighborhood patterns, SVC constructs global decision boundaries using kernel methods, and MLP captures nonlinear feature relationships through learned parameters.

Table 1 reports their class-wise precision, recall, F1-score, and ROC-AUC, offering a detailed comparison beyond overall accuracy.

All ML models were trained on the same low-dimensional geometric feature vectors described in

Section 4 and

Section 5. Standardization was applied prior to training to ensure that distance- and margin-based methods (KNN and SVC) operate on comparable feature scales, and hyperparameters were selected exclusively using the training/validation partition to avoid test-set leakage.

As shown in

Table 1, precision, recall, and F1-scores are consistent with overall accuracy, indicating balanced classification across both posture categories. KNN achieved the highest precision for the False class (0.99) and strong F1 for the True class (0.98), suggesting minimal false positives and an excellent precision–recall trade-off. SVC and MLP also performed reliably, although slightly behind KNN. The ROC-AUC scores further confirm these findings, with MLP achieving 0.9778 and KNN closely behind at 0.9689. Given its instance-based nature and the low-dimensional geometric feature space, KNN provides a competitive, low-latency baseline suitable for embedded deployment.

6.2. Evaluation of Deep Learning Models

To complement the results of traditional classifiers, three deep learning architectures were evaluated: a custom 20-layer Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), ResNet52, and DenseNet121. These models operate directly on the image-based dataset, learning spatial and structural patterns from raw visual input. Their evaluation aims to determine how end-to-end feature extraction compares with manually derived geometric features.

Table 2 lists the main hyperparameters used during training, ensuring a fair comparison across models.

In contrast to ML evaluation, the deep learning models receive only image inputs and therefore reflect purely end-to-end learning from RGB posture frames. To enable controlled comparison across architectures, training procedures (optimizer choice, learning rate, batch size, and early stopping policy) are kept fixed, so that performance differences can be attributed primarily to architectural characteristics rather than procedural variation.

All models were trained with the same learning rate (0.001) and Adam optimizer, using early stopping to prevent overfitting once validation accuracy stabilized. A batch size of 64 provided a practical balance between gradient stability and computational efficiency. These controlled conditions ensure that observed differences reflect architectural rather than procedural factors.

Early stopping is interpreted here as a convergence regularizer: training is halted once validation performance ceases to improve for a sustained period, preventing unnecessary optimization on the training set and reducing the risk of overfitting. The reported stopping epochs in

Table 2 therefore provide a compact indication of convergence speed and validation stability across architectures.

Table 3 summarizes the quantitative performance of the three models. ResNet52 achieved the best results overall, with 94.37% test accuracy and an F1-score of 0.9448, followed by the custom 20-layer CNN at 93.57% and DenseNet121 at 81.53%.

ResNet52 exhibited the most stable convergence, maintaining a narrow gap between training and validation accuracy. Its residual connections improved gradient flow and minimized overfitting, allowing consistent generalization across datasets. The 20-layer CNN performed comparably but showed early saturation of validation accuracy after approximately 45 epochs, suggesting mild overfitting despite early stopping. DenseNet121 demonstrated strong training performance but limited generalization, likely due to its higher architectural complexity relative to dataset size.

To further assess classification reliability,

Table 4 reports confusion matrices for all three models. ResNet52 showed balanced detection across both posture classes, with only a small number of misclassifications. The 20-layer CNN was conservative, generating fewer false positives but more false negatives, while DenseNet121 produced the highest overall error counts.

To avoid ambiguity in interpretation,

Table 4 follows the convention that True Positive corresponds to correctly detected True (correct posture) samples, and True Negative corresponds to correctly detected False (incorrect posture) samples. This mapping aligns with the binary labeling strategy used during dataset construction.

The confusion matrices confirm that ResNet52 achieved the most balanced performance, with only minor false detections. The 20-layer CNN favored conservative classification, prioritizing accuracy for incorrect posture detection at the cost of occasional missed detections of correct posture (i.e., increased false negatives for the True class). DenseNet121, though effective in feature reuse, appeared less suitable for smaller, domain-specific datasets without stronger regularization or augmentation.

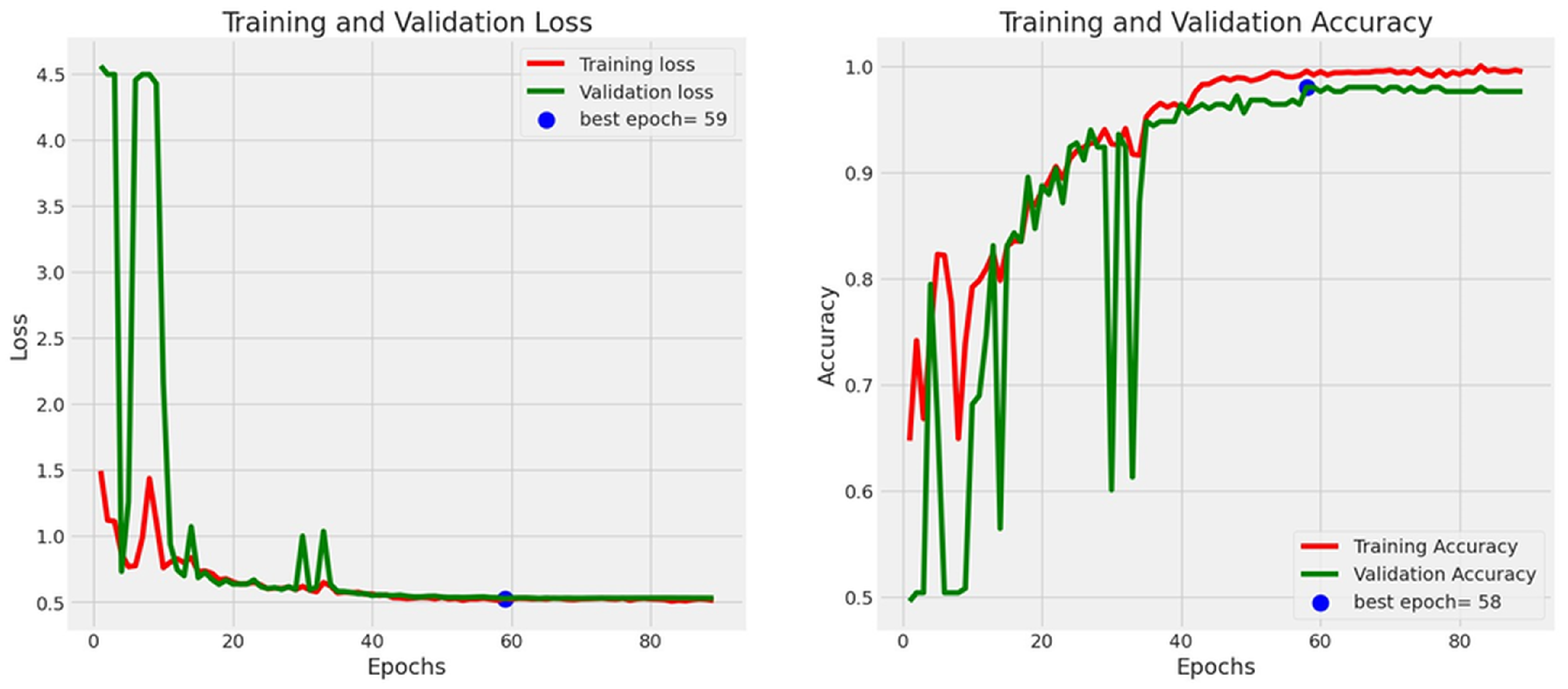

Figure 6 shows that ResNet52 converges smoothly: training accuracy rises steadily and the validation curve follows closely, with both stabilizing near the early-stopping point (epoch 88). The absence of large oscillations and the small, persistent gap between training and validation trajectories indicate stable optimization and limited overfitting. This behavior aligns with the residual architecture’s facilitation of gradient flow, supporting the strong generalization observed in

Table 3.

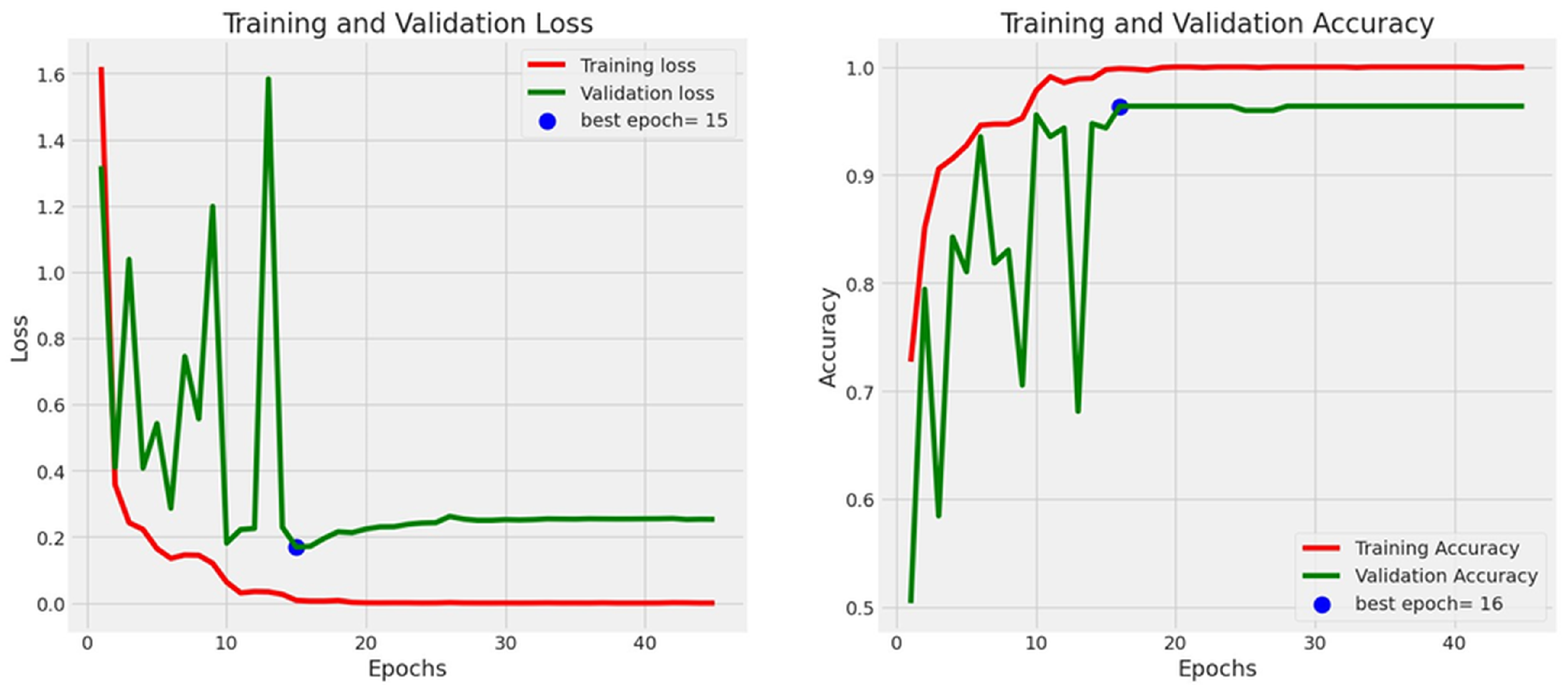

Figure 7 indicates that the 20-layer CNN attains near-perfect training accuracy rapidly, but validation accuracy plateaus earlier and at a lower level, leading to early stopping around epoch 46. The widening gap between the two curves after mid-training reflects mild overfitting: capacity is sufficient to fit the training set, while validation gains saturate. This pattern is consistent with its test results—competitive overall performance with a tendency toward conservative predictions (cf. confusion matrix in

Table 4).

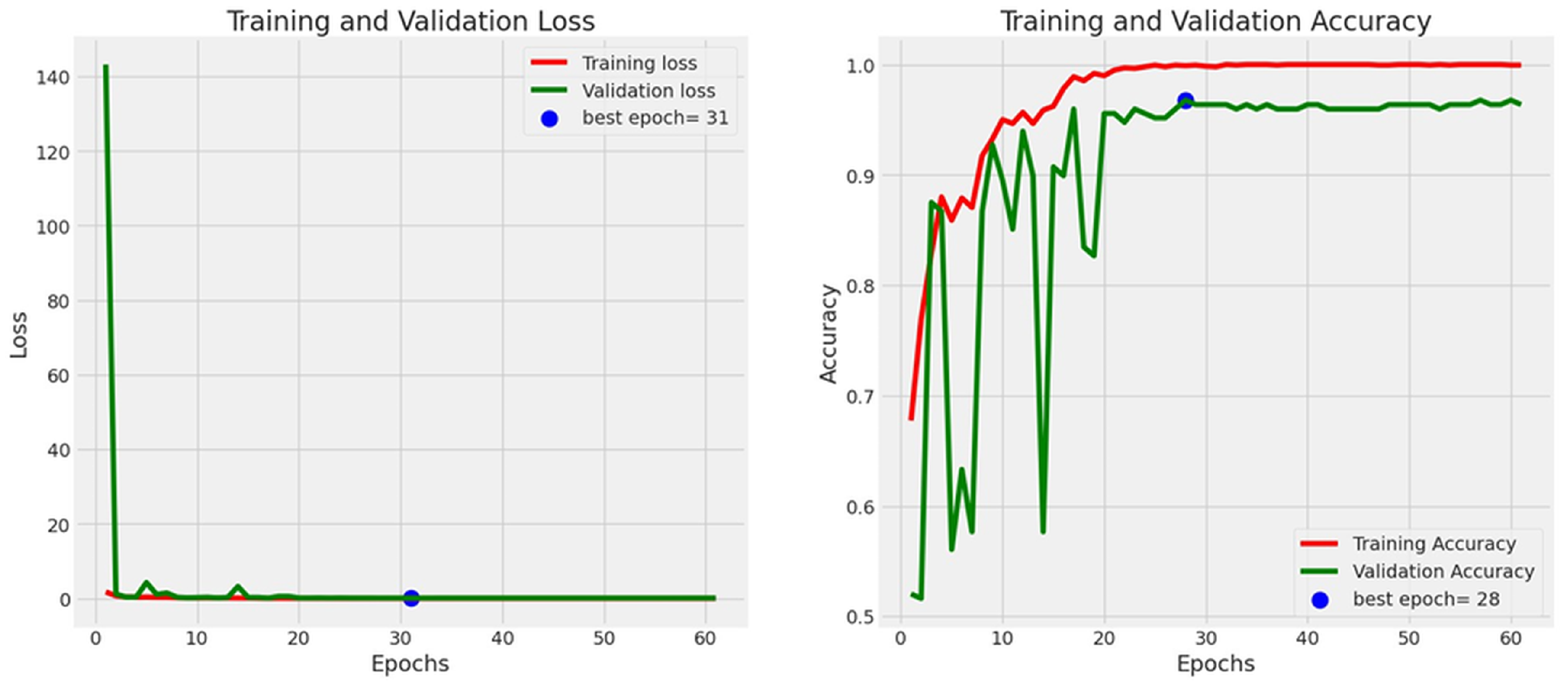

Figure 8 exhibits less stable learning for DenseNet121: the validation accuracy fluctuates and plateaus below the training curve despite continued training to approximately epoch 84. The persistent train–val gap and irregular validation trajectory suggest sensitivity to dataset size and regularization. This instability explains the weaker generalization on the test set (

Table 3) and the higher error counts in the confusion matrix (

Table 4).

In conclusion, ResNet52 outperformed the other models across nearly all evaluation metrics, demonstrating the best trade-off between learning capacity and generalization. The custom 20-layer CNN showed competitive performance and fast convergence but would benefit from stronger regularization to mitigate overfitting. DenseNet121, while architecturally sophisticated, underperformed for the current dataset size, indicating that further adjustments in feature scaling, training duration, and regularization are required to fully exploit its potential.

6.3. Discussion

The experimental results highlight clear distinctions between traditional machine learning and deep learning approaches for posture classification. Machine learning models, trained on handcrafted geometric features, achieved high predictive accuracy with minimal computational cost. Among them, K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) attained the best overall accuracy (98.74%) and exhibited consistent precision and recall across both posture classes. Its strong performance stems from its ability to leverage local feature distributions, which are particularly effective in the low-dimensional space defined by inclination angles and offsets. The Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) demonstrated similarly balanced results and the highest ROC-AUC (0.9778), indicating that even a shallow neural model can capture nonlinear dependencies effectively when provided with well-engineered inputs. In contrast, the Support Vector Classifier (SVC) performed reliably but slightly below the other two, suggesting that its margin-based kernel mapping was less adaptive to intra-class variability in the dataset.

The deep learning results confirmed that larger architectures can provide additional representational power but require careful control of training dynamics and data scale. ResNet52 emerged as the most effective model, combining high test accuracy (94.37%) with smooth convergence and robust generalization. Its residual learning structure mitigated gradient vanishing and supported deeper feature hierarchies, yielding consistent improvement over both the 20-layer CNN and DenseNet121. The custom CNN achieved competitive results (93.57%) but showed early signs of overfitting, suggesting that additional regularization or data augmentation could further enhance stability. DenseNet121, while theoretically advantageous due to its dense connectivity and feature reuse, failed to generalize adequately—likely a consequence of its complexity relative to dataset size and limited variability in training samples.

From an experimental design perspective, the results emphasize that (i) carefully engineered geometric features can yield extremely strong baselines for posture classification in controlled settings, and (ii) deep architectures may require stronger regularization and/or augmentation to translate high training accuracy into robust test-time generalization. This observation is consistent with the train–validation gaps and the confusion-matrix patterns reported for the evaluated CNN-based models.

From an application perspective, these findings underscore a trade-off between computational simplicity and architectural depth. Lightweight models such as KNN and MLP provide near-optimal accuracy while maintaining low latency, making them well-suited for embedded or IoT-based posture monitoring systems. Conversely, deep architectures like ResNet52 deliver more consistent performance under complex visual conditions, at the cost of higher resource requirements. In practice, the choice between these approaches depends on deployment context: on-device, low-power systems may favor ML baselines, while cloud-connected or workstation-based systems can leverage deeper models for enhanced robustness.

Overall, the experimental evidence validates the effectiveness of both paradigms within their operational domains. The integration of geometric modeling with modern neural architectures provides a scalable and interpretable foundation for real-time posture assessment. These insights guide future improvements in model selection, data augmentation, and edge-based optimization for intelligent ergonomic systems.

7. Conclusions and Future Work

This study presented a comprehensive evaluation of traditional machine learning and deep learning techniques for binary posture classification, emphasizing their respective strengths, limitations, and suitability for real-world ergonomic monitoring. The proposed framework integrated both geometric feature extraction and visual learning, enabling a comparative analysis of interpretable classical models—K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Support Vector Classifier (SVC), and Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP)—against high-capacity deep architectures, including a custom 20-layer Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), ResNet52, and DenseNet121.

Beyond reporting model performance, the study contributes a unified, reproducible evaluation setting in which classical feature-based learning and end-to-end visual learning are assessed under consistent data splits and standardized preprocessing, thereby enabling a fair comparison of competing modeling paradigms for posture monitoring.

Among the machine learning approaches, KNN achieved the highest classification accuracy and balanced precision–recall behavior, confirming its reliability for low-dimensional geometric feature spaces. MLP also performed competitively, capturing nonlinear patterns effectively despite its compact architecture. SVC, while consistent, was slightly less robust, suggesting sensitivity to kernel configuration and margin regularization in posture-specific datasets.

Within the deep learning domain, ResNet52 outperformed the other architectures, demonstrating the best trade-off between depth, convergence stability, and generalization. Its residual learning mechanism enabled efficient gradient propagation and mitigated overfitting. The 20-layer CNN produced comparable results but exhibited moderate overfitting, indicating the need for enhanced regularization or data augmentation. DenseNet121, though efficient in theory, underperformed in practice, likely due to its parameter complexity relative to dataset scale and diversity.

These results underscore the importance of aligning model complexity with dataset characteristics and deployment constraints. Lightweight ML models remain well-suited for embedded and real-time IoT applications, offering high accuracy at minimal computational cost, whereas deeper architectures provide superior feature abstraction for larger-scale or cloud-based systems. Model stability was further supported by consistent hyperparameter tuning, standardized input dimensions, and early stopping criteria.

A key limitation of the present evaluation is that posture is treated as an independent per-frame decision, which does not explicitly capture temporal continuity and may penalize brief transitional movements. This motivates future extensions toward sequence-aware modeling and temporal smoothing, where posture persistence can be modeled more naturally and alerts can be triggered based on sustained deviations rather than instantaneous fluctuations.

Future work will extend this framework toward temporal and multimodal learning, incorporating sequential data to analyze posture evolution over time. Expanding the dataset to include more participants, viewpoints, and environmental conditions will improve generalization and reduce bias [

13]. Additionally, exploring semi-supervised, transfer, and ensemble learning strategies could enhance robustness while lowering dependence on labeled data [

43,

44]. Personalized adaptation mechanisms that account for ergonomic differences among users represent another promising direction for improving adherence and long-term health outcomes. Finally, ethical considerations surrounding data privacy, transparency, and informed consent must remain central to the design and deployment of posture monitoring systems, particularly in healthcare and workplace settings.

Overall, this work establishes a solid foundation for intelligent, scalable, and ethically responsible posture detection systems. By combining interpretable geometric modeling with modern visual learning, it contributes to the advancement of preventive digital healthcare and human–computer interaction at the intersection of artificial intelligence and ergonomics.