Abstract

Osteoarthritis (OA) of the hip (coxarthrosis) and knee (gonarthrosis) is a leading cause of disability worldwide. Differential diagnosis typically relies on imaging modalities such as X-rays and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). However, advanced imaging can be expensive and inaccessible, highlighting the need for non-invasive diagnostic tools. This study aimed to develop and validate an interpretable machine learning model to distinguish between hip and knee osteoarthritis using standard preoperative clinical and laboratory data. This model is designed to assist physicians in prioritizing whether to order a hip or a knee X-ray first, thereby saving time and medical resources. The study utilized retrospective data from 1792 patients treated at the City Clinical Hospital in Almaty, Kazakhstan. After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, five machine learning algorithms were used for training and evaluation: Decision Tree, Random Forest, Logistic Regression, XGBoost, and CatBoost. SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) and Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME) were employed to interpret predictions and determine the contribution of each feature. The XGBoost model demonstrated the best performance, achieving an accuracy of 93.85%, a precision of 95.15%, a recall of 90.51%, and an F1-score of 92.41%. SHAP analysis revealed that age, glucose and leukocyte levels, urea, and BMI made the greatest contributions to the model’s predictions, while local analysis using LIME indicated that age, leukocyte levels, glucose, erythrocytes, and platelets were the most influential features. These findings support the use of machine learning for cost-effective early osteoarthritis triage using routine preoperative data.

1. Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a leading global cause of disability, primarily affecting the knee (~250 million people) and hip. Hip OA affects 3–11% of Western adults over 35 and ~15% globally [1], with prevalence varying significantly by socioeconomic status and geography [2]. As populations age and obesity rates rise, surgical demand is escalating. In the U.S., joint replacement costs exceeded $22.6 billion in 2004, with over 25% of patients requiring additional procedures within 5–8 years [3,4]. Similarly, Australia projects a 276% rise in total knee replacements (TKRs) and 208% in total hip replacements (THRs) by 2030, with obesity alone driving substantial cost increases [5]. Across Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, knee arthroplasty use is projected to quadruple to 5.7 million procedures by 2030, increasing fastest in patients under 65 [6]. High costs and rising surgical rates are also evident across Europe and Iran, where implants drive the majority of expenses [7,8,9,10,11].

OA can be diagnosed with imaging, yet current methods have important limitations. Radiography detects structural changes but correlates poorly with symptoms; only ~15% of patients with radiographic knee OA report pain, and it frequently misses early disease and soft tissue damage. While MRI offers earlier detection, it remains costly and less accessible. Diagnostic challenges are amplified in post-traumatic osteoarthritis (PTOA), where radiographs detect only 14–21% of cases compared to 33–39% for MRI [12,13,14]. Veterinary research reinforces these limitations, as early joint changes remain undetectable with standard imaging, while MRI use is further restricted by cost, lengthy scans, and the need for anesthesia [15]. Advanced imaging, including com-positional MRI, PET-MRI, and weight-bearing CT, improves sensitivity but is restricted by high costs, radiation, and workflow constraints [16,17]. Furthermore, interpretation remains subjective: radiographic Kellgren & Lawrence (KL) grading has poor reproducibility in early stages, and MRI lacks standardized definitions for early OA [18,19,20].

These constraints of imaging have accelerated interest in non-imaging strategies. A large body of work demonstrates the effectiveness of machine learning using non-imaging data for KOA prediction. Using clinical and laboratory data from 2594 samples, LASSO and SHAP identified key predictors, with Random Forest achieving an AUC of 0.961 using only five variables [21]. Deep neural networks based on demographic and personal data have also shown moderate performance, reaching AUCs of 76.8% [22]. Analysis of the OAI database further showed that combining symptoms, activity, health status, and examination data enabled SVM to achieve 74.07% accuracy, supporting the value of heterogeneous clinical inputs for KOA prediction [23].

Beyond standard clinical variables, EHR-based models such as SVM, logistic regression, Random Forest, XGBoost, and KNN have been applied to predict osteoarthritis risk and the need for surgical intervention. In parallel, deep learning and omics-based approaches have been used to identify relevant biomarkers and molecular pathways [24]. Models relying solely on health behavior and routine medical records achieved AUCs of 76.8%, demonstrating the feasibility of early diagnosis without imaging [25]. Progression-focused studies using non-imaging OAI data reported up to 83.3% accuracy for joint space narrowing prediction [26]. Notably, models trained exclusively on demographics and laboratory indices achieved AUCs above 0.90, highlighting the potential of low-cost clinical data for early KOA risk stratification [21].

Compared to previous research, which has predominantly focused on applying machine learning to imaging data for grading the severity of osteoarthritis, our work shifts the focus away from imaging-based assessment. The main contribution of this paper is the proposal of a non-invasive differential diagnostic method. This method distinguishes between coxarthrosis and gonarthrosis using routinely available clinical and laboratory data prior to imaging. While extensive work has analyzed OA using radiographs and MRI scans, a gap remains in the clinical sorting of patients who present with lower limb joint pain that has not yet been clearly localized.

The explicit goal of this study was to determine whether a reliable differential diagnosis between coxarthrosis and gonarthrosis could be achieved prior to imaging, relying solely on low-cost, universally accessible preoperative data. This work is not intended to replace imaging-based gold standards, but rather to serve as a practical tri-age tool within the initial clinical assessment. The clinical scenario targeted is that of a patient presenting with non-specific lower limb pain, where the model can assist the clinician in deciding whether to first request a hip or a knee X-ray. Importantly, this work was not designed for initial diagnostic screening (i.e., distinguishing OA from healthy individuals or other joint diseases). Instead, it was specifically intended to assist in differentiating between two already symptomatic and clinically suspected osteoarthritis types.

First, we propose and validate a machine learning model to classify symptomatic OA as either coxarthrosis or gonarthrosis using a panel of preoperative clinical and laboratory parameters. Second, we apply SHAP and LIME to interpret the model’s predictions and highlight the most influential factors that differentiate the two conditions. SHAP offers a global perspective on how variables contribute across the dataset, while LIME provides local, patient-specific explanations, and together they enhance both transparency and clinical trust in the model. The clinical novelty of this work addresses a common diagnostic challenge related to the difficulty of localizing the primary source of pain when shared innervation pathways are involved. This includes referred pain in which hip pathology may manifest as knee pain. In standard practice, such ambiguity often leads to unnecessary negative X rays or referrals to an inappropriate sub specialist. By utilizing routinely available clinical and laboratory data, our models resolve this localization challenge before the patient is exposed to radiation or incurs imaging costs. By offering a faster and less costly approach, our study aims to provide a tool that supports clinical triage. This tool helps direct symptomatic musculoskeletal patients toward the appropriate specialist pathway, thereby improving resource utilization and ensuring more timely access to care.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset Description

The dataset used in this study was collected in the endoprosthetics department of the City Clinical Hospital of Almaty, Kazakhstan and includes the clinical and laboratory indicators of 1792 patients. The inclusion criteria were age 50 years or older, clinically and radiologically confirmed coxarthrosis or gonarthrosis (Kellgren–Lawrence grade ≥ II) [27], normal levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) [28]. These eligibility criteria were selected to define a homogeneous OA cohort and to minimize diagnostic confounding. Requiring age ≥ 50 and KL grade ≥ II ensured the inclusion of patients with definite radiographic OA, thereby avoiding borderline or preclinical cases and improving internal validity [27]. The restriction to normal CRP and ESR values was applied to exclude inflammatory joint diseases, since OA is typically characterized by normal or only mildly elevated systemic inflammatory markers [29].

The exclusion criteria comprised elevated levels of CRP, ESR, RF, ACPA, or uric acid; diagnosed inflammatory arthritis (rheumatoid and others); aseptic necrosis, tumors, infections, or recent joint injuries; primary source of pain originating from the spine; as well as severe comorbid pathologies, significant cognitive impairments, or incomplete clinical and laboratory records [28]. These criteria were applied to eliminate patients whose joint pain or dysfunction might be attributable to other causes (such as autoimmune diseases, metabolic disorders, infections, or neoplasms) rather than OA. By excluding cases with significant comorbidities or incomplete data, the study aimed to improve the reliability of subsequent analyses, ensure diagnostic clarity, and reduce potential bias when interpreting outcomes [30].

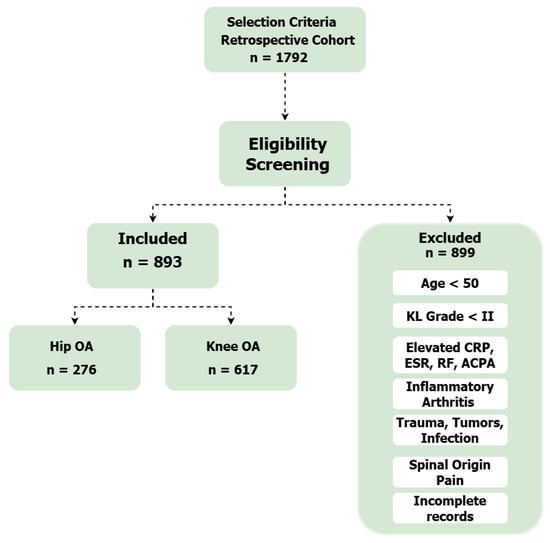

This study initially included data from 1792 patients. After applying the clearly defined inclusion and exclusion criteria, followed by a data preprocessing phase to ensure data completeness and quality, the final dataset used for the analysis retained homogeneous data from 893 patients.

The dataset contains 20 variables. Demographic information includes gender, age, weight, and height. Clinical indicators comprise heart rate (HR), number of hospital bed-days, and diagnosis. Hematological parameters include hemoglobin, leukocytes, platelets, erythrocytes, hematocrit, and ESR. Biochemical measurements cover total protein, urea, creatinine, total bilirubin, liver enzymes (ALT and AST), and glucose.

The distinctive feature of this dataset is that all information was collected exclusively during the preoperative period. This provides an opportunity to apply machine learning methods for early assessment of patient condition, prediction of disease progression risks, and support in treatment decision-making [31]. The comprehensiveness of the collected data allows for an integrated analysis of demographic, clinical, hematological, and biochemical indicators. Moreover, the clearly defined inclusion and exclusion criteria ensure the homogeneity of the study population and enhance the predictive accuracy of the applied models.

The final cohort consisted of 893 patients, including 660 females and 233 males. The mean age was 62.38 ± 11.76 years, with an average body weight of 75.41 ± 7.99 kg and a mean height of 169.9 ± 6.84 cm. The mean body mass index (BMI) was 26.21 ± 2.4 kg/m2, indicating that most participants were within the overweight range. The mean resting heart rate (HR) was 76.67 ± 2.82 beats per minute. The participant characteristics are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of participant characteristics.

Figure 1 depicts the study selection process, starting with an initial retrospective cohort of 1792 patients. Following a rigorous screening process that excluded 899 individuals based on specific eligibility criteria—such as age, inflammatory markers, and data completeness—a final homogeneous group of 893 patients was retained. This final cohort was divided into two diagnostic groups: 276 patients with coxarthrosis (hip osteoarthritis) and 617 patients with gonarthrosis (knee osteoarthritis).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study selection process.

2.2. Data Preprocessing

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and followed the ethical standards of institutional and international research committees [32]. Ethical review was conducted and approved by the Bioethics Committee of NCSTO named after academician N.D.Batpenov (Protocol № 1/4).

In accordance with local legislation and the approved protocol (№ 1/4), the Bioethics Committee waived the requirement for individual patient informed consent. This waiver was granted because the study involved the retrospective analysis of a dataset that was fully anonymized by the institution prior to its release to the research team.

Data curation and anonymization were conducted under the governance policies of NCSTO named after academician N.D.Batpenov. The dataset was fully anonymized before analysis: all direct identifiers (such as names, initials, hospital record numbers) were removed, and indirect identifiers (such as full dates) were generalized or pseudonymized following principles consistent with ISO 25237:2017.

The research team received only this anonymized data; no identifiable information was accessible to the researchers during or after analysis. All data were stored on secure institutional servers with access restricted to the research team only.

In this study, the quality of the dataset was considered critical, as it directly affects the performance and interpretability of machine learning models [33,34]. Since the data were collected in a real clinical environment, they contained missing values, numerical variables measured on different scales, and class imbalance. To address these challenges and ensure the robustness of subsequent analyses, several systematic preprocessing steps were applied.

First, to handle missing values and ensure data integrity, a listwise deletion approach was adopted. All patient records containing at least one missing value were excluded from the analysis, resulting in a complete dataset for model training [35]. Following this, a multicollinearity analysis was conducted using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) to assess the linear dependence between predictor variables [35]. This analysis revealed high VIF values for ‘height’, ‘weight’, and ‘BMI’, indicating strong correlation. To mitigate this issue and enhance the stability of model interpretation, the ‘height’ and ‘weight’ features were removed, while the clinically relevant ‘BMI’ feature was retained. A subsequent VIF analysis on the remaining features confirmed the absence of significant multicollinearity.

Categorical variables were also processed to ensure compatibility with machine learning algorithms, which generally require numerical inputs. In this dataset, gender was a categorical variable with two values. Label Encoding was chosen over one-hot encoding, assigning “Female” = 0 and “Male” = 1. Because the variable was binary, this approach provided a simple and efficient solution, avoiding unnecessary dimensionality while ensuring that demographic information was preserved in the predictive process.

Another important step was feature scaling [36]. Clinical indicators were recorded in different units—age in years, hemoglobin in g/L, glucose in mmol/L, and platelets in ×109/L. If left unscaled, features with larger numerical ranges could dominate the model and bias the learning process. To prevent this, Z-score normalization was applied, standardizing all variables to a common scale with a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one [37]. The transformation is defined as:

where x is the observed value, is the mean, and is the standard deviation. This method was preferred over min-max scaling because it preserves the distributional properties of the data and is less sensitive to outliers [38], which are frequent in clinical measurements. By applying this procedure, the influence of each variable on the model was balanced, ensuring that features such as platelet count did not overshadow others like glucose levels.

Beyond harmonization, it was important to assess the diagnostic contribution of each variable. To achieve this, mutual information analysis was performed, as it quantifies non-linear dependencies between features and the target outcome [39]. Unlike simple correlation coefficients, mutual information can capture more complex relationships [40], which are common in medical data.

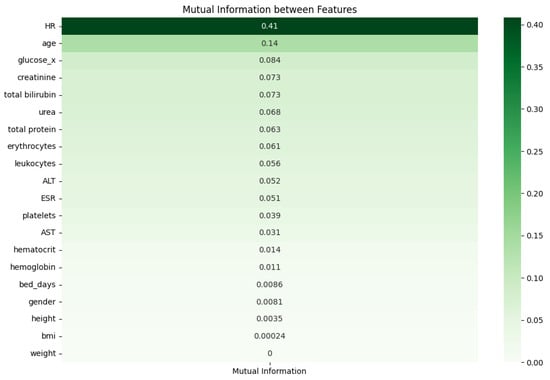

Figure 2 illustrates the mutual information values of variables in the dataset. The highest information contribution was attributed to HR (0.41), age (0.14), and glucose (0.084). In addition, clinical indicators such as creatinine (0.073), total bilirubin (0.073), urea (0.068), and total protein (0.063) demonstrated moderate levels of relevance.

Figure 2.

Mutual Information between features.

Meanwhile, AST, body weight, height, and bed days showed lower mutual information values, suggesting their limited role in the model. Hemoglobin, hematocrit, BMI, and gender had values close to zero, indicating lower predictive importance compared to other variables.

This analysis makes it possible to compare the predictive contribution of variables and provides a foundation for selecting the most informative indicators and improving the model [41]. Critically, to ensure rigorous validation and avoid data leakage, SMOTE was applied strictly to the training folds only during each iteration of the stratified 5-fold cross-validation. The validation folds remained composed entirely of original, real-world patient data. This setup ensures that the reported performance metrics reflect the model’s ability to generalize to unseen, non-synthetic clinical data [42]. The model is then trained and evaluated five times, with each fold used once as the test set while the other four are used for training. The final performance metrics are reported as the average across all five folds. This approach minimizes the risk of bias from a single data split and provides a more reliable estimate of the model’s ability to generalize to new, unseen data [43,44].

These preprocessing steps enhanced the quality and balance of the dataset and created a solid foundation for building interpretable machine learning models. Each method was carefully selected to address specific challenges: label encoding enabled categorical variables to be included, Z-score normalization harmonized scales, mutual information highlighted the most relevant predictors and stratified cross-validation provided a robust validation framework. Collectively, these measures not only improved predictive performance but also ensured that the resulting models were clinically trustworthy and transparent.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

A multivariable binary logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify and quantify factors independently associated with the differential diagnosis of coxarthrosis versus gonarthrosis. The logistic regression model was selected as the primary statistical method because it enables the simultaneous assessment of multiple predictor variables while accounting for confounding effects, and it is well-suited for binary outcome variables [45]. In this model, the dependent variable was the diagnosis outcome (gonarthrosis coded as 1, coxarthrosis coded as 0), and all preoperative demographic, clinical, and laboratory parameters were included as independent variables.

The regression coefficients were estimated using the maximum likelihood method, a computer-intensive technique that identifies parameter values maximizing the likelihood of observing the actual data [46]. Each regression coefficient represents the change in the natural log of odds (log-odds) of the outcome for a one-unit increase in the corresponding predictor variable, controlling for all other variables in the model.

The primary outputs of the multivariable logistic regression analysis were odds ratios (ORs) with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) and p-values for each predictor variable [47]. The odds ratio was calculated by exponentiating the logistic regression coefficient according to the formula [48]:

An OR greater than 1 indicates that an increase in the predictor variable is associated with increased odds of the outcome; conversely, an OR less than 1 indicates decreased odds. The 95% confidence interval for the odds ratio was computed to provide a range of plausible values around the point estimate [49]. Statistical significance was determined using the Wald test with a threshold of p < 0.05. This approach provides clinically interpretable estimates of the magnitude and direction of association for each variable, while simultaneously controlling for the confounding effects of other variables in the model [50].

2.4. Machine Learning Algorithms for Classification

Both classical and ensemble machine learning algorithms were applied to distinguish between coxarthrosis and gonarthrosis. The primary objective was to compare models that are not only accurate but also interpretable, thereby identifying the most effective approach from a clinical perspective. To achieve this, Decision Tree, Random Forest, Logistic Regression, XGBoost, and CatBoost algorithms were employed. To benchmark these models against modern deep learning architectures, a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) and a TabNet model, specifically designed for tabular data, were also included in the analysis.

In all binary classification tasks, coxarthrosis was designated as the positive class (Class 1), while gonarthrosis was treated as the negative class (Class 0). This class designation was maintained consistently across all training, validation, and interpretability analyses (including SHAP and LIME). This definition ensured clinical clarity in performance metrics interpretation—true positives representing correctly identified cases of coxarthrosis, and true negatives corresponding to correctly classified gonarthrosis patients.

The Decision Tree was selected as a simple and intuitive algorithm [51]. It partitions features based on threshold values and produces a model that is easy to interpret. This structure allows clinicians to visually follow the decision-making process, making the model highly transparent.

Random Forest represents an ensemble of decision trees [52]. Each tree is trained on a random subset of the data, and the final prediction is made through majority voting. This reduces the risk of overfitting and enhances stability, making Random Forest particularly suitable for complex and heterogeneous medical data.

Logistic Regression is a widely used classical method for binary classification [53]. It models probabilities through the logistic function and quantifies the effect of each variable via coefficients. This statistical transparency makes it valuable in clinical contexts, where interpretability and the ability to assess the influence of individual features are essential.

XGBoost is a gradient boosting algorithm that incrementally improves weak classifiers to achieve high predictive accuracy [54]. It is well-suited for modeling non-linear relationships, robust to missing values, and optimized for computational speed, which makes it a strong choice for large and complex clinical datasets.

CatBoost is a modern boosting method that handles categorical variables automatically [55], eliminating the need for prior transformations such as Label Encoding or One-hot Encoding. This feature is especially beneficial in healthcare data, where categorical predictors like gender or diagnosis type are common and clinically relevant.

A Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) is a feedforward neural network composed of an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer [56]. It learns complex non-linear relationships by applying weighted transformations followed by activation functions at each layer [57,58]. MLPs are widely used for classification and regression tasks due to their flexibility, simplicity, and strong performance on structured data [59].

TabNet is a deep learning architecture specifically designed for tabular data, using sequential attention to choose which features to focus on at each decision step [60]. Its sparse feature selection makes the model both highly interpretable and efficient compared to traditional neural networks.

Given the imbalanced nature of the dataset, where gonarthrosis cases outnumbered coxarthrosis cases, the Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) was implemented to prevent model bias towards the majority class [61]. Critically, SMOTE was applied only to the training data within each fold of the cross-validation pipeline, ensuring that the test data remained unaltered and providing an unbiased evaluation of model performance [62].

Since model performance depends heavily on hyperparameter selection, Grid Search was used for optimization [63]. The hyperparameter tuning process was performed within the cross-validation loop to prevent data leakage. We defined a specific search space for each algorithm. For the gradient boosting models, we optimized the learning rate (range: 0.01–0.1), tree depth (range: 4–10), and number of iterations (range: 300–700). For Random Forest, we tuned the number of estimators (100–500) and max features. The specific optimal parameters selected for the final CatBoost model were depth: 6, iterations: 700, and learning rate: 0.05. This exhaustive search examines all possible parameter combinations to determine the most effective configuration. For interpretability, the LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) method was employed [64]. Unlike global interpretability techniques, LIME focuses on explaining individual predictions. It works by perturbing the input data around a specific instance and then training a simple interpretable model (such as a linear regression or decision tree) on the perturbed samples to approximate the local decision boundary of the complex model. By doing so, LIME provides clinicians with an intuitive explanation of why the model classified a particular patient as having coxarthrosis or gonarthrosis, highlighting which features contributed most strongly to that decision. This local interpretability is particularly valuable in clinical contexts, where understanding individual predictions is often more important than global model behavior.

In addition to LIME, SHAP was applied to provide a more comprehensive interpretation of model predictions [65]. SHAP is based on cooperative game theory and assigns each feature a Shapley value, which represents its contribution to the difference between the actual prediction and the average baseline prediction. Unlike LIME, which explains a single prediction locally, SHAP offers both global and local interpretability: it can show which features are most important across the entire dataset while also detailing their influence on specific individual cases. In a clinical setting, SHAP allows practitioners to understand not only why a given patient was classified in a certain way, but also which predictors consistently drive decision-making across the patient population. This dual perspective enhances transparency and trust in the model’s outputs.

The models were evaluated using four standard performance metrics: Accuracy, Recall, Precision, and F1-score [66].

Accuracy—represents the overall proportion of correctly classified cases among all samples:

where TP is true positives, TN true negatives, FP false positives, and FN false negatives.

Recall (Sensitivity)—measures the proportion of actual positive cases that were correctly identified by the model:

This metric reflects the model’s ability to detect true cases of the disease, which is especially critical in clinical applications where missed diagnoses (false negatives) may have severe consequences.

Precision—indicates the proportion of predicted positive cases that were actually correct:

This metric evaluates the reliability of positive predictions, reducing the risk of false alarms (false positives) in diagnostic practice.

F1-score—represents the harmonic mean of Precision and Recall, balancing both metrics in a single value:

The F1-score is particularly useful in imbalanced datasets, as it provides a more comprehensive evaluation of model performance by combining sensitivity and predictive precision.

These metrics allowed a comprehensive evaluation of the models, assessing not only overall accuracy but also their ability to minimize false positives and false negatives—factors of particular importance in clinical applications. Results demonstrated that while Decision Tree provided the highest interpretability, ensemble methods such as Random Forest, XGBoost, and CatBoost achieved superior predictive accuracy. Logistic Regression, meanwhile, remained valuable for its statistical interpretability and clinical transparency. The use of LIME further enhanced trust in the models by providing clear, case-specific explanations of diagnostic predictions, making the decision-making process more reliable and clinically actionable.

To complement the predictive machine learning models and adopt a formal statistical perspective, we conducted a separate analysis to identify and quantify factors independently associated with the differential diagnosis of coxarthrosis versus gonarthrosis. For this purpose, a multivariable binary logistic regression model, a form of Generalized Linear Model (GLM), was employed.

The dependent variable in the model was the diagnosis, coded as 0 for coxarthrosis and 1 for gonarthrosis. All preoperative demographic, clinical, and laboratory parameters presented in the dataset were included as independent variables (predictors) to assess their individual contributions while controlling for the effects of other variables.

The primary outputs of this analysis were Odds Ratios (ORs) with their corresponding 95% Confidence Intervals (95% CIs) and p-values for each predictor. The OR represents the multiplicative change in the odds of having gonarthrosis versus coxarthrosis for a one-unit increase in the independent variable. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

The comparative evaluation of the applied machine learning algorithms revealed distinct performance patterns. The Decision Tree, while offering the clearest interpretability, demonstrated relatively moderate predictive performance compared to other methods. Random Forest consistently improved upon the Decision Tree by reducing variance and achieving more stable results across different data partitions [67]. Logistic Regression showed balanced outcomes [68], providing clinically relevant coefficients that highlighted the influence of individual predictors, though its accuracy was slightly lower than that of the ensemble methods.

Among the boosting algorithms, both CatBoost and XGBoost achieved strong predictive performance. CatBoost demonstrated the highest overall accuracy and F1-score, confirming its strength in handling the dataset’s complexities. XGBoost also performed exceptionally well, showing a strong balance between precision and recall. The best-performing CatBoost model was trained using the following hyperparameters: depth: 6; iterations: 700; learning rate: 0.05. The newly introduced deep learning models, MLP and TabNet, provided a valuable benchmark, though their performance was generally lower than the top-performing gradient boosting models on this particular dataset [54].

Table 2 provides a comparative overview of the performance of all seven machine learning algorithms, with metrics averaged across the 5-fold cross-validation. Among them, CatBoost achieved the highest overall performance. Its average Accuracy reached 0.9373 (±0.0198), reflecting a high proportion of correctly classified cases, while the Precision score of 0.9333 (±0.0128) indicated that its positive predictions were highly reliable. With a Recall of 0.8592 (±0.0666), the model demonstrated strong sensitivity, and the F1-score of 0.8932 (±0.0379) confirmed an effective balance between precision and recall.

Table 2.

Sensitivity Analysis: Model Performance with SMOTE.

Ensemble methods such as XGBoost and Random Forest also performed strongly. XGBoost achieved an Accuracy of 0.9339 (±0.0155) and an F1-score of 0.8899 (±0.0308), while Random Forest produced stable results with an Accuracy of 0.9194 (±0.0108). The inclusion of standard deviations for each metric highlights the robustness of these models across different data partitions during cross-validation.

Decision Tree remained valuable due to its simplicity and interpretability. Although its overall results were slightly lower than the top boosting models, with an Accuracy of 0.9284 (±0.0207), it delivered a very high Precision value of 0.9458 (±0.0453), highlighting its strength in minimizing false positives.

Logistic Regression, in contrast, recorded lower performance compared to the ensemble models, with an Accuracy of 0.8948 (±0.0117) and an F1-score of 0.8295 (±0.0210). Nevertheless, it retained clinical relevance by offering transparency in how each variable contributed to classification outcomes. The deep learning models, MLP and TabNet, yielded F1-scores of 0.8541 (±0.0215) and 0.8207 (±0.0465), respectively, serving as an important baseline for comparison.

The deep learning models, MLP and TabNet, yielded the following results: MLP achieved an Accuracy of 0.9093 (±0.0135) and an F1-score of 0.8541 (±0.0215). TabNet, in turn, showed an Accuracy of 0.8881 (±0.0287) and an F1-score of 0.8207 (±0.0465). These results serve as an important baseline for comparison.

To address potential biases introduced by the data augmentation technique and to ensure methodological transparency, we conducted a sensitivity analysis by retraining all models on the original, imbalanced dataset without applying SMOTE. The objective was to verify whether the high predictive performance was driven by genuine biological signals rather than artifacts of synthetic oversampling. The results of this analysis are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Sensitivity Analysis: Model Performance without SMOTE (Imbalanced Dataset).

Comparing the results from the SMOTE-enhanced training (Table 2) with the original imbalanced data (Table 3) reveals a high degree of robustness across the ensemble models. For instance, the CatBoost model showed minimal deviation, with accuracy slightly shifting from 0.9339 (with SMOTE) to 0.9396 (without SMOTE), and the F1-score remaining stable (0.8932 vs. 0.8863). Interestingly, XGBoost and Random Forest exhibited slightly higher precision in the absence of SMOTE, likely due to a more conservative prediction threshold on the minority class. Overall, the consistency of these metrics confirms that the models’ discriminative power is robust and not heavily dependent on the balancing technique.

The findings demonstrated that ensemble models, particularly gradient boosting methods, outperformed other approaches. CatBoost and XGBoost achieved the highest and most stable performance, while other models like Random Forest and Decision Tree also provided competitive and interpretable results.

Interpreting machine learning models is essential in clinical practice, as it allows physicians to not only see the outcome of a prediction but also to assess the relative importance of individual clinical variables. To achieve this, the SHAP approach was applied [60]. Unlike methods that provide only local explanations, SHAP delivers both a global perspective on feature contributions across the dataset and localized insights at the patient level. This combination enhances the transparency and interpretability of the model, helping to connect advanced machine learning predictions with established clinical reasoning.

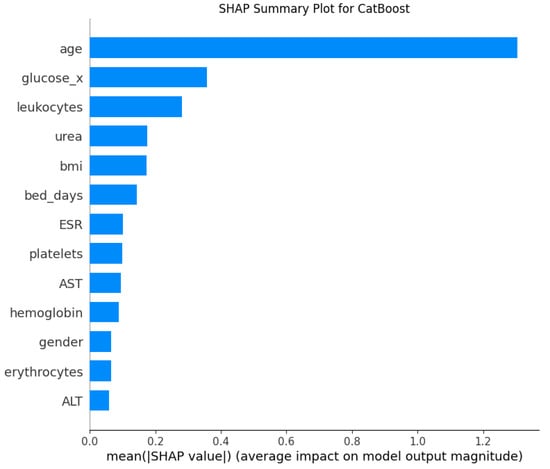

As shown in Figure 3, the mean absolute SHAP values illustrate the average contribution of each feature to the predictions of the CatBoost model. The analysis shows that age is by far the most influential variable, having a substantially larger impact than any other feature. It is followed by glucose level (glucose_x), leukocyte count, urea, and BMI, which also make significant contributions to the model’s decisions. Other clinical and demographic parameters such as the number of bed-days, ESR, platelet count, and AST demonstrated a moderate level of importance. Features like hemoglobin, gender, erythrocytes, and ALT had the smallest effect on the model’s output. These outcomes highlight the importance of not only well-established demographic risk factors like age and BMI, but also systemic biochemical and hematological markers in the differential diagnosis of coxarthrosis and gonarthrosis.

Figure 3.

SHAP Feature Importance for the CatBoost Model.

Both SHAP and LIME analyses revealed that age, glucose, and leukocytes were the most influential factors driving the machine learning model’s predictions. This finding is also clinically supported by existing medical evidence. Age is widely recognized as the primary risk factor for OA [69]. The continuous use of joints throughout an individual’s lifetime leads to progressive deterioration. Combined with the limited regenerative capacity of articular cartilage, this cumulative wear contributes to the onset and progression of OA [70]. Elevated glucose levels play a significant role in OA pathogenesis. High glucose concentrations can stimulate the production of proinflammatory cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases within joint tissues, which in turn damage human chondrocytes and promote the development of OA [71]. Similarly, leukocytes, also referred to as white blood cells (WBCs) [72] have been shown to have a causal relationship with OA. In OA, the white blood cell count is usually less than 500 cells per mm2 (or 0.5 × 109 per L) [73].

Model interpretation is clinically essential, as physicians need to understand not only the outcome of a prediction but also which features contributed most to the decision-making process. For this purpose, the LIME method was selected [64]. This approach allows the model’s predictions to be explained at a local level for each individual patient. LIME is model-agnostic, meaning it can be applied to any complex algorithm regardless of its internal structure. This represents a significant advantage in clinical applications, as it translates complex predictions into a simple and understandable form for physicians.

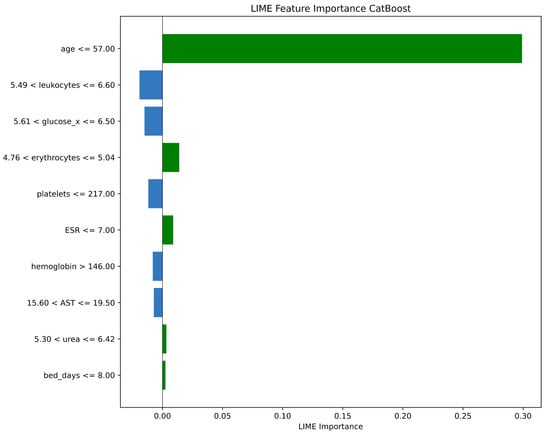

As illustrated in Figure 4, the feature importance results for a single test sample were generated using the LIME method for the CatBoost model. This analysis not only illustrates the contribution of each variable to the model’s decision but also enables interpretation of the prediction at the patient level. For this specific patient, the most influential factor was age, with a value of 57 years or less (age ≤ 57.00), which strongly supported the model’s prediction (indicated by the large green bar). Other factors that contributed to this prediction, albeit with much smaller impacts, included erythrocyte levels (4.76 < erythrocytes ≤ 5.04) and ESR (ESR ≤ 7.00). Conversely, factors such as leukocyte and glucose levels pushed the prediction in the opposite direction (indicated by the blue bars). This detailed, patient-specific explanation demonstrates how the model weighs different clinical indicators to arrive at a conclusion for an individual case.

Figure 4.

LIME Feature Importance for the CatBoost Model.

These interpretations align the model’s predictions with established clinical knowledge. In other words, the LIME method makes it possible to explain the decisions of complex “black-box” models in simple terms for physicians [69,70,71,72,73,74]. This approach enhances trust in the predictions and facilitates the use of the model as a supportive tool in real clinical decision-making.

Model interpretability is a key requirement in clinical machine learning, and both SHAP and LIME offer complementary advantages. SHAP provides a global perspective, quantifying the average contribution of each feature across the dataset, while also allowing local insights. This makes it particularly useful for understanding the overall role of clinical variables such as age, leukocytes, and glucose in cardiovascular risk prediction. In contrast, LIME focuses on local interpretability, explaining individual predictions for each patient. This patient-specific view helps clinicians understand why a particular decision was made, thus increasing trust in model outputs.

A comparative synthesis of the Multivariable Logistic Regression, SHAP, and LIME analyses reveals a high degree of consistency in identifying key predictors. All three approaches independently confirmed that demographic and hematological profiles are the strongest differentiators. Specifically, Age emerged as the dominant predictor across all methods (Logistic Regression: p < 0.001; SHAP: highest global contribution; LIME: primary local driver). Furthermore, systemic markers such as Glucose and Leukocytes were consistently ranked among the top features by both the non-linear boosting models (via SHAP) and the linear statistical model. This triangulation of findings across different algorithmic approaches reinforces the clinical validity of these biological markers in distinguishing coxarthrosis from gonarthrosis.

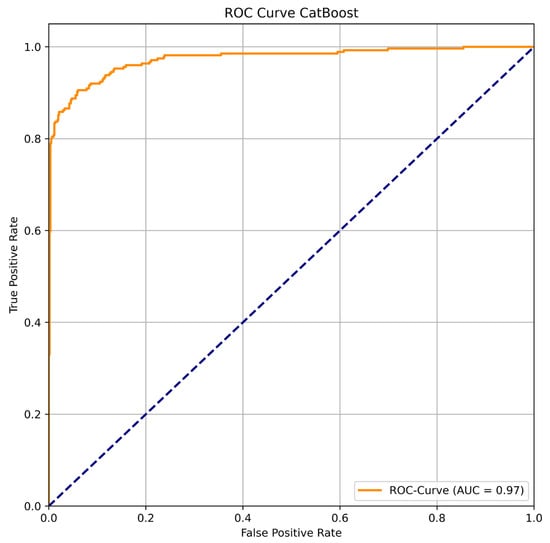

To further evaluate the diagnostic ability of the best-performing model, CatBoost, a Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve was generated, and the Area Under the Curve (AUC) was calculated. As shown in Figure 5, the ROC curve lies close to the top-left corner, indicating a high degree of separability between the two classes. The model achieved an outstanding AUC value of 0.97, which signifies its excellent discriminative power in distinguishing between coxarthrosis and gonarthrosis. This high AUC confirms that the model maintains a strong balance between high sensitivity (True Positive Rate) and high specificity (low False Positive Rate) across all classification thresholds.

Figure 5.

ROC Curve for CatBoost.

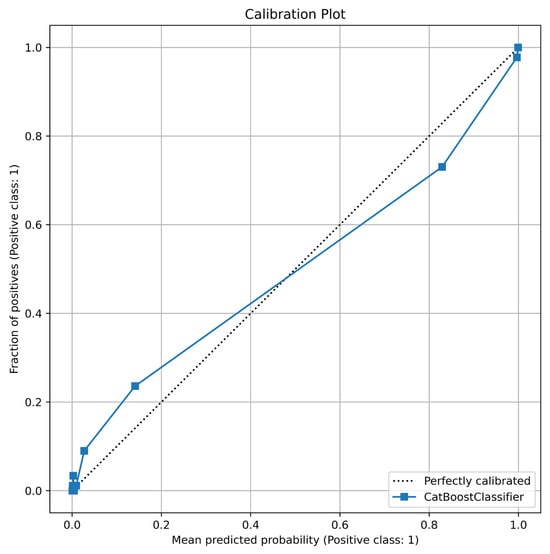

Beyond its discriminative power, the reliability of the model’s probabilistic predictions was assessed using a calibration plot and the Brier score. The calibration curve, depicted in Figure 6, compares the predicted probabilities against the actual observed frequencies. The plot shows that the CatBoost model’s calibration line closely follows the diagonal “perfectly calibrated” line, indicating that its predicted probabilities are highly reliable. For instance, when the model predicts a probability of ~0.7, the actual fraction of positive cases in that bin is indeed close to 0.7. This visual assessment is quantitatively supported by a very low Brier score of 0.0500. Such a low score confirms excellent calibration and implies that the confidence of the model’s predictions can be trusted in a clinical setting, which is crucial for supporting medical decision-making.

Figure 6.

Calibration Plot for CatBoost.

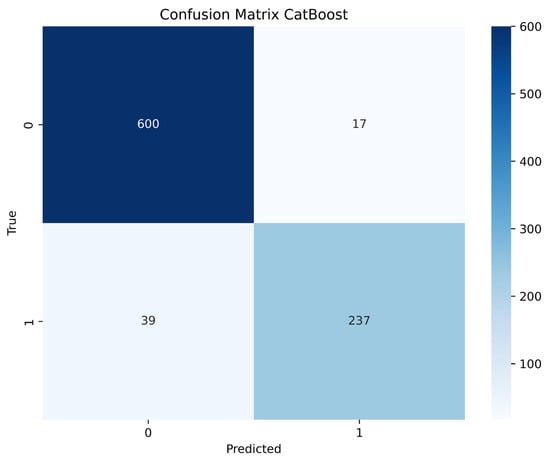

An essential approach for evaluating the quality of classification results is the Confusion Matrix, as it provides a clear breakdown of correct and incorrect predictions. This method not only reflects the overall performance of the model but also highlights the types of misclassifications. In clinical applications, the role of the Confusion Matrix is particularly critical, since both false positives and false negatives may carry significant medical implications.

Figure 7 presents the Confusion Matrix for the CatBoost model, aggregated across all cross-validation folds. The model correctly classified 600 cases as true negatives (Class 0) and 237 cases as true positives (Class 1). In terms of misclassifications, there were 17 instances of false positive predictions (Class 0 incorrectly predicted as Class 1), while false negatives were recorded in 39 cases (Class 1 incorrectly predicted as Class 0). This distribution demonstrates that while the model generally performs well, it has a tendency to miss some true positive cases more frequently than it makes false positive errors.

Figure 7.

Confusion Matrix for XGBoost.

These results confirm the overall effectiveness of the CatBoost model: it shows excellent accuracy in detecting negative cases and correctly identifies a substantial majority of positive cases. However, the presence of 39 false negatives must be carefully considered in a medical context, as missing a true diagnosis could delay appropriate treatment. Conversely, the low number of false positives (17) suggests that positive predictions are highly reliable. Nevertheless, the strong overall performance indicators, coupled with the high AUC and good calibration, highlight the reliability of the model and its potential applicability in clinical decision-making.

To identify factors independently associated with a diagnosis of gonarthrosis versus coxarthrosis, a multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed. The model revealed several statistically significant predictors after adjusting for all other variables in the model. The full results are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Results of a multivariable logistic regression analysis.

The strongest associations were observed with demographic and clinical variables. Male gender was a powerful predictor, with males having nearly three times the odds of being diagnosed with gonarthrosis compared to females (OR = 2.96; 95% CI [1.611–5.436]; p = 0.0005). Conversely, age demonstrated a strong negative association; for each additional year of age, the odds of a patient having gonarthrosis versus coxarthrosis decreased by 9.5% (OR = 0.90; 95% CI [0.883–0.926]; p < 0.001). A similarly strong negative association was observed for heart rate (HR), where each one-beat-per-minute increase was associated with a 59.2% decrease in the odds of having gonarthrosis (OR = 0.41; 95% CI [0.361–0.461]; p < 0.001).

Among laboratory parameters, hematological markers showed significant associations. Hematocrit was a significant positive predictor, with each one-unit increase raising the odds of gonarthrosis by 14.3% (OR = 1.14; 95% CI [1.086–1.203]; p < 0.001). In contrast, hemoglobin showed a statistically significant, albeit smaller, negative association (OR = 0.97; 95% CI [0.957–0.984]; p < 0.001). From the biochemical panel, only total bilirubin emerged as a statistically significant factor, where higher levels were associated with a slight reduction in the odds of gonarthrosis (OR = 0.95; 95% CI [0.910–0.996]; p = 0.032).

It is noteworthy that several other variables did not reach statistical significance in the multivariable model. These included leukocyte count (p = 0.104) and, most notably, Body Mass Index (BMI) (p = 0.113). Additionally, glucose levels showed a trend towards significance but did not cross the p < 0.05 threshold (p = 0.064).

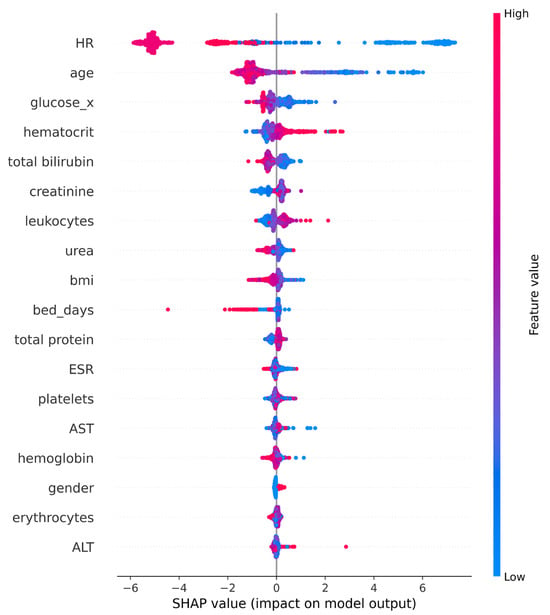

The SHAP summary plot, in Figure 8, provides a comprehensive visualization of both the global importance and individual impact of each feature on the model’s predictions. The horizontal position of each point represents the SHAP value—how strongly and in what direction a feature influences the prediction—while the color indicates the feature value (blue for low, red for high). The uppermost feature, age, demonstrates the strongest overall contribution, confirming that age is the dominant driver of the model’s output. This finding aligns with the previously discussed feature-importance ranking, where age outperformed all other predictors, followed by glucose, leukocytes, urea, and BMI.

Figure 8.

SHAP Summary plot (CatBoost).

For glucose and leukocytes, the SHAP distribution shows a clear rightward shift for higher values (red), suggesting that elevated levels of these biomarkers increase the model’s likelihood of a positive prediction. Urea and BMI display moderate yet consistent influence, with their points forming balanced distributions, indicating broad but less intense effects across the dataset. In contrast, bed_days exhibits a few extreme outliers with large negative SHAP values, implying that longer hospitalization has a strong, but infrequent, impact on model outputs. Features such as ESR, platelets, and AST cluster near zero, showing limited global contribution, while hemoglobin, gender, erythrocytes, and ALT have the smallest overall effect, aside from isolated cases.

4. Discussion

Our study demonstrates the potential of machine learning, particularly the CatBoost algorithm, to differentiate between coxarthrosis and gonarthrosis using readily available, non-invasive preoperative data. The high accuracy (93.73%), precision (93.33%), and strong F1-score (89.32%) achieved by our model demonstrate its overall effectiveness and reliability. This is a significant finding, as it addresses a research gap in the early clinical management of osteoarthritis. While previous research has focused on applying machine learning to imaging data for grading disease severity, our work explores the untapped potential of routine clinical and laboratory markers. These markers are used to distinguish between coxarthrosis and gonarthrosis at the initial diagnostic stage. Crucially, this study was not intended for initial diagnostic screening (e.g., distinguishing OA from healthy subjects or other joint disorders), but rather aimed to assist in differentiating between two clinically suspected and already symptomatic forms of OA.

The higher performance of CatBoost over XGBoost aligns with emerging evidence supporting gradient boosting methods in medical classification tasks. A recent comparative analysis by [75] demonstrated that CatBoost achieved an accuracy of 98.37% in a medical diagnostic task, outperforming XGBoost. This finding aligns with the results of the present study, further supporting the superior predictive performance of CatBoost. The inclusion of both traditional ensemble methods, such as Random Forest and Decision Tree, strengthens the comparative validity of the results. This is further reinforced by the use of modern gradient boosting techniques (XGBoost, CatBoost) and deep learning benchmarks (MLP, TabNet). The stratified 5-fold cross-validation approach used in this study is consistent with best practices in recent machine learning research for osteoarthritis, as emphasized by [76], who highlighted that robust validation frameworks are essential for generalizability and reliable performance estimation.

Beyond the choice of algorithm, the validity of our approach is supported by a growing body of literature favoring non-imaging inputs. Across recent research, non-imaging, machine learning–based models have emerged as powerful tools for diagnosing and predicting KOA and related conditions. Ref. [77] developed an interpretable XGBoost–SHAP diagnostic framework using demographic and clinical questionnaire data, deliberately excluding radiographic inputs to enhance accessibility. Ref. [21] similarly constructed clinical biomarker-based models from laboratory data without relying on imaging, achieving high diagnostic accuracy for KOA. Complementing these, Ref. [78] built a multifactorial, explainable CatBoost model predicting sarcopenia risk in KOA patients from routine health and survey variables. These studies demonstrate that robust, explainable AI systems using demographic, laboratory, and clinical data—rather than imaging—can accurately identify and stratify musculoskeletal disorders, supporting the methodological consistency of our non-imaging research approach.

Drawing from this consistent approach, the inclusion of SHAP provided global interpretability, showing that variables such as age, leukocyte count, AST, glucose, and erythrocytes had the strongest overall influence on the model’s predictions. On the other hand, the LIME analysis further enhances the clinical utility of our model by providing transparent, patient-specific explanations for its predictions. The identification of age, glucose, leukocytes, urea, and BMI as the most influential predictors through SHAP analysis aligns remarkably well with contemporary biomarker-based approaches to osteoarthritis diagnosis. A comprehensive 2025 study [21] that analyzed 2594 clinical samples to identify biomarkers for knee osteoarthritis found that the top five clinical predictors were age, plasma prothrombin time, gender, BMI, and prothrombin time international normalized ratio (PTINR), with Random Forest achieving AUC values exceeding 0.95 [21]. This congruence with the feature ranking in the present study validates the mechanistic understanding of which laboratory and demographic variables drive osteoarthritis differentiation. A 2024 systematic review [78] examined the application of LIME and SHAP in Alzheimer’s disease detection. The review emphasized that combining global and local interpretability approaches enhances the trustworthiness and clinical adoption of machine learning models in medical practice [79].

In addition to biological plausibility, this non-imaging framework directly responds to evolving clinical standards. The non-imaging approach used in this study addresses a critical gap identified by clinical guidelines and recent research. A 2025 review [80] on knee osteoarthritis diagnosis emphasized that routine imaging is often unnecessary for initial diagnosis when appropriate clinical assessment and laboratory data are available. This approach can reduce radiation exposure and healthcare costs [80]. Recent research on automated machine learning for predicting knee osteoarthritis progression demonstrated that models incorporating clinical variables alone—without advanced imaging—achieved competitive performance. These models were also more feasible for implementation in resource-limited settings, directly paralleling the clinical applicability emphasized in the present work [76].

While the clinical utility is clear, it is also necessary to address the methodological divergence observed in our results regarding feature selection. The discrepancy between the predictors identified by the multivariable logistic regression model and the feature importance rankings derived from the CatBoost-SHAP analysis highlights the distinct methodological paradigms. Specifically, it reflects the difference between statistical inference and machine learning prediction. Logistic regression, as a generalized linear model [81], evaluates the statistical significance of individual variables based on linear assumptions. Consequently, this method prioritizes predictors with consistent, linear additive effects across the entire cohort.

On the other hand, the CatBoost algorithm utilizes gradient-boosted decision trees [82], which are non-parametric [83] and inherently designed to maximize predictive accuracy [84,85] rather than statistical significance. This architecture allows the model to capture complex non-linear relationships and high-order feature interactions that linear models may fail to detect or deem statistically insignificant. A variable may exhibit high predictive value (SHAP importance) because it strongly influences classification within specific patient subgroups or value ranges, even if it lacks a robust linear association across the general population.

The robustness provided by this architecture allows our model to compete favorably against more resource-intensive modalities. The performance of our CatBoost model is not only robust in isolation. It is also highly competitive when compared to other machine learning applications in osteoarthritis research, many of which rely on more complex, costly, or invasive diagnostic methods. For instance, studies leveraging imaging data, such as radiographs or MRI scans, have reported accuracies in the range of 83% to 90.8% [22,86]. While valuable, these imaging-based approaches often involve significant financial costs, radiation exposure [80], and long waiting times [87], making them less suitable for initial, large-scale screening. Similarly, research incorporating advanced biomarkers has shown promising results. However, these biomarkers are not always part of routine clinical practice [88]. In this context, our model’s ability to achieve a high level of accuracy by non-invasive methods using routinely collected clinical and laboratory data represents a significant step forward. This approach highlights the overlooked diagnostic value embedded in standard preoperative workups.

These advantages in cost and non-invasiveness translate directly into operational efficiency. The efficiency and accessibility of our proposed method are particularly noteworthy. In healthcare environments with limited resources, where access to advanced imaging technologies or specialized laboratory tests is restricted, our model offers a practical and cost-effective alternative. By providing a data-driven solution to a common diagnostic challenge, our work presents a practical tool that can fundamentally streamline the clinical pathway for patients with suspected lower limb osteoarthritis. This can lead to more efficient patient triage, a reduction in unnecessary and costly imaging procedures, and more timely referrals to orthopedic specialists, ultimately improving patient outcomes and optimizing the use of healthcare resources.

However, to ensure this efficiency translates safely into practice, we critically analyzed the decision threshold and calibration performance in response to observed misclassification patterns. We employed a standard classification threshold of 0.5, empirically selected to maximize the F1-score and ensure a balance between precision and recall. However, the Confusion Matrix (Figure 6) reveals a disparity between false positives (17 cases) and false negatives (39 cases). This relatively higher false-negative rate likely reflects a subset of coxarthrosis patients presenting with systemic biological profiles mimicking those of gonarthrosis. In a real-world triage context, the clinical implication of this misclassification is manageable: it would primarily result in a rerouted X-ray request (e.g., ordering a knee X-ray for a hip patient) rather than a missed diagnosis. Regarding calibration, while the global curve (Figure 5) demonstrates excellent probability alignment, we acknowledge the limitation concerning demographic subgroups. Although we aimed to examine calibration across strata (e.g., by age or sex), the stratified sample sizes within test folds were insufficient to generate statistically robust curves. Future prospective studies with larger cohorts will be essential to validate subgroup calibration and, importantly, to determine if the decision threshold should be dynamically adjusted (e.g., lowered below 0.5) to prioritize sensitivity and further reduce false negatives in clinical practice.

The successful deployment of this diagnostic tool relies on its effective integration into existing clinical workflows and Electronic Medical Record (EMR) systems. An optimal implementation strategy involves the use of Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) to automate the retrieval of key predictors, such as age and hematological markers. This approach reduces data entry redundancy and preserves clinical efficiency. Additionally, the user interface should be designed to present not only the classification result but also the underlying interpretability metrics. By visualizing SHAP values within the clinical dashboard, the model functions as an explainable Clinical Decision Support System (CDSS). This allows practitioners to validate algorithmic outputs against their own clinical judgment, ensuring the tool serves as a transparent aid to decision-making.

Despite the promising results, this study has several limitations that need to be considered. The study sample was focused on patients at a specific, late stage of the disease—those who were already indicated for joint replacement surgery. Consequently, the cohort represents a homogeneous, surgery-indicated population characterized by advanced late-stage pathology (patients indicated for arthroplasty; Kellgren–Lawrence grade ≥ II). This introduces a selection bias because the metabolic and hematological profiles of these patients may differ substantially from those with early stage or mild osteoarthritis managed in primary care. The model shows high predictive accuracy that may partly reflect the distinct biological signatures present in severe disease, which are less pronounced in early-stage cases. Therefore, the generalizability of the model to primary care settings where disease severity is more heterogeneous remains to be validated. Moreover, data was collected from a single institution. As a result, the model reflects the specific demographic genetic and environmental characteristics of this local population. The retrospective design of this study introduces the possibility of selection bias, as the cohort was restricted to patients already scheduled for surgery at a single clinical center. Moreover, while the SMOTE was applied to mitigate class imbalance, this approach has inherent limitations. Since SMOTE generates synthetic samples via interpolation between existing minority instances, it may not fully replicate the complex, stochastic variations inherent in real-world patient distributions. Consequently, there is a risk that the model may learn from patterns that, while mathematically plausible in a high-dimensional space, do not perfectly align with the biological heterogeneity of a broader, prospective population. This suggests that while the internal validation results are robust, the model’s performance should be interpreted with caution until validated on independent, naturally distributed cohorts. External validation of the model on broader, multi-center, and prospective patient cohorts covering all stages of the disease is required to confirm that the identified features such as age, glucose and leukocytes remain robust predictors across diverse populations.

In general, this model is not intended to serve as a standalone diagnostic tool. It does not incorporate imaging data or clinical symptoms, which limits its ability to provide a comprehensive assessment of OA. Additionally, the model cannot distinguish OA patients from healthy individuals or from patients with non-OA joint pathologies due to the absence of a control group. Consequently, the model is not designed for initial screening or for broad evaluation of general joint pain; if applied to a healthy individual, it would erroneously force a classification into one of the two pathological categories. It is strictly intended as a triage tool for patients who have already been clinically assessed as having osteoarthritis but lack definitive localization. The study also relied solely on routine clinical and laboratory variables to prioritize accessibility and cost effectiveness. However, this design required the exclusion of other potentially informative data sources. Specifically, the model does not incorporate imaging features, patient reported symptoms, biomechanical assessments, or advanced omics biomarkers. While the current results demonstrate the significant diagnostic value of standard preoperative data, the omission of these high dimensional variables likely constrains the upper limit of the model predictive power. Future research should focus on developing multimodal models that integrate these diverse data streams, combining routine clinical inputs with biomechanical and patient reported data to enhance diagnostic precision and clinical utility.

5. Conclusions

This study initially included clinical and laboratory data from 1792 patients. After rigorous filtering based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria, a homogeneous dataset of 893 patients remained. Such data cleaning enhanced the quality of the sample, reduced noise, and allowed the applied machine learning models to achieve high predictive performance.

Among the algorithms used, XGBoost demonstrated the best results, achieving an accuracy of 93.85%, a precision of 95.15%, a recall of 90.51%, and an F1-score of 92.41%. Model interpretability was ensured through SHAP and LIME methods. SHAP analysis revealed that age, leukocyte count, AST, glucose, and erythrocyte levels were the most influential factors in decision-making, while LIME highlighted patient-specific drivers such as age, ESR, and gender. These interpretability approaches enhanced clinical trust and brought the results closer to practical application in medical practice.

The novelty of this work lies in demonstrating that hip and knee OA can be differentiated without imaging techniques, relying solely on routine clinical and laboratory indicators. While previous studies have depended on radiographs or MRI, our method offers a more affordable, accessible, and faster solution, which is particularly relevant for healthcare systems with limited resources. The primary objective of this study was to evaluate whether it is possible to distinguish between two established forms of osteoarthritis—coxarthrosis (hip OA) and gonarthrosis (knee OA)—prior to imaging, relying solely on low-cost, universally available preoperative data. Notably, the study was not intended for initial diagnostic screening (i.e., differentiating OA from healthy individuals or other joint conditions), but rather aimed to facilitate differential diagnosis between two clinically suspected and already symptomatic OA types.

Future research should expand this work by validating the model in prospective, multi-center cohorts that encompass the full spectrum of disease severity, specifically targeting early-stage (Kellgren–Lawrence grades 0–I) and non-surgical outpatient populations. Since the systemic metabolic and inflammatory signals leveraged by the current model may be less pronounced in the initial phases of OA compared to the advanced surgical cases analyzed here, evaluating the model’s sensitivity in these milder cohorts is critical to determine its utility for early screening and preventive intervention. Extending the analysis to diverse healthcare settings will allow for the assessment of the model’s resilience against variations in laboratory measurement standards and demographic heterogeneity, ensuring that the diagnostic predictions remain reliable across different populations and technical environments. Incorporating additional data, such as patient-reported outcomes, functional assessments, or omics-based biomarkers, could further enhance predictive power. Developing hybrid models that integrate clinical data with imaging features may provide a comprehensive framework for early diagnosis, disease monitoring, and treatment planning.

Future work should also specifically aim to benchmark the machine learning algorithm against clinician-predicted diagnoses. Since the current retrospective analysis of electronic health records precluded a real-time comparison with unassisted clinical judgment, a prospective study is necessary to compare the model’s performance against human clinicians. This step will be essential to contextualize the model’s incremental value and ensure its reliability before routine clinical deployment. Ultimately, the implementation of interpretable AI systems in real-world clinical practice, supported by continuous physician feedback, will be essential to evaluate their impact on healthcare efficiency, patient outcomes, and resource allocation.

While the current framework establishes the feasibility of differentiating between specific osteoarthritis phenotypes using preoperative data, future research aims to expand the model’s diagnostic utility. A key objective is to evolve the current binary classifier into a multiclass framework capable of distinguishing osteoarthritis from other common musculoskeletal conditions. This expansion would transform the model into a comprehensive first-line triage tool for undifferentiated lower limb pain in primary care settings. Moreover, we intend to adapt the machine learning architecture to address prognostic challenges. By shifting the focus from static classification to dynamic longitudinal assessment, future iterations could predict disease progression trajectories, stratifying patients based on the risk of rapid deterioration or estimating the anticipated time-to-surgery, thereby facilitating more personalized long-term management strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.B., B.I., A.B., B.A. and N.T.; methodology, Z.B., A.B., B.I., B.A., N.T., K.O. and N.M.-N.; software, B.A., N.T., D.B. and R.B.; validation, B.I., K.O., D.B., N.M.-N. and R.B.; formal analysis, B.I., K.O., D.B., N.M.-N. and R.B.; investigation, Z.B., B.I., A.B., B.A. and N.T.; resources, Z.B., A.B., B.A. and N.T.; data curation, D.B., N.M.-N. and R.B.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.B., A.B., B.A., N.T. and R.B.; writing—review and editing, N.M.-N., B.I., K.O. and D.B.; visualization, Z.B., A.B., B.A. and N.T.; supervision, B.I., K.O., D.B. and N.M.-N.; project administration, B.I. and K.O.; funding acquisition, K.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Grant No. BR24992820).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Bioethics Committee of NCSTO named after academician N.D.Batpenov.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation is not required as per local legislation [Protocol № 1/4].

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon the request.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Zhanel Baigaraeva and Assiya Boltaboyeva, Naoya Maeda-Nishino was employed by the company LLP “Kazakhstan R&D Solutions”, Naoya Maeda-Nishino was employed by the company HAKUAI Medical Corporation. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| OA | Osteoarthritis |

| KL | Kellgren–Lawrence grading |

| TKR | Total Knee Replacement |

| THR | Total Hip Replacement |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| KOA | Knee Osteoarthritis |

| PTOA | Post-Traumatic Osteoarthritis |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| PET-MRI | Positron Emission Tomography–Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| DNN | Deep Neural Network |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| LR | Logistic Regression |

| RF | Random Forest |

| KNN | K-Nearest Neighbors |

| XGBoost | Extreme Gradient Boosting |

| CatBoost | Categorical Boosting |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| SHAP | SHapley Additive exPlanations |

| LIME | Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations |

| EHR | Electronic Health Record |

| CRP | C-Reactive Protein |

| ESR | Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate |

| ACPA | Anti-Citrullinated Protein Antibody |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| PTINR | Prothrombin Time International Normalized Ratio |

| ALT | Alanine Aminotransferase |

| AST | Aspartate Aminotransferase |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| TP | True Positive |

| TN | True Negative |

| FP | False Positive |

| FN | False Negative |

| HR | Heart Rate |

| DCS | Decision Tree Classifier |

| JSN | Joint Space Narrowing |

References

- Alkady, E.A.M.; Selim, Z.I.; Abdelaziz, M.M.; El-Hafeez, F.A. Epidemiology and Socioeconomic Burden of Osteoarthritis. J. Curr. Med. Res. Pract. 2023, 8, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, L.F.; Cleveland, R.J.; Allen, K.D.; Golightly, Y.M. Racial/Ethnic, Socioeconomic, and Geographic Disparities in the Epidemiology of Knee and Hip Osteoarthritis. Rheum. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2021, 47, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palazzo, C.; Nguyen, C.; Lefevre-Colau, M.-M.; Rannou, F.; Poiraudeau, S. Risk Factors and Burden of Osteoarthritis. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2016, 59, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamplot, J.D.; Bansal, A.; Nguyen, J.T.; Brophy, R.H. Risk of Subsequent Joint Arthroplasty in Contralateral or Different Joint after Index Shoulder, Hip, or Knee Arthroplasty. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2018, 100, 1750–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ackerman, I.N.; Bohensky, M.A.; Zomer, E.; Tacey, M.; Gorelik, A.; Brand, C.A.; De Steiger, R. The Projected Burden of Primary Total Knee and Hip Replacement for Osteoarthritis in Australia to the Year 2030. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2019, 20, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabinger, C.; Lothaller, H.; Geissler, A. Utilization Rates of Knee Arthroplasty in OECD Countries. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2015, 23, 1664–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savvari, P.; Skiadas, I.; Barmpouni, M.; Menegas, D. Moderate to Severe Osteoarthritis: What Is the Economic Burden for Patients and the Health Care System? Insights from the “PONOS” Study. Cartilage 2023, 15, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajos, L.F.; Molics, B.; Elmer, D.; Pónusz-Kovács, D.; Kovács, B.; Horváth, L.; Csákvári, T.; Bódis, J.; Boncz, I. Annual Epidemiological and Health Insurance Disease Burden of Hip Osteoarthritis in Hungary Based on Nationwide Data. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2024, 25, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabi, M.; Pourahmadi, E.; Adel, A.; Kemmak, A.R. Economic Burden of Knee Joint Replacement in Iran. Cost Eff. Resour. Alloc. 2024, 22, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, I.N.; Bohensky, M.A.; De Steiger, R.; Mehnert, F.; Pedersen, A.B.; Robertsson, O. Substantial Rise in the Lifetime Risk of Primary Total Knee Replacement Surgery for Osteoarthritis from 2003 to 2013: An International, Population-Level Analysis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2017, 25, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottle, A.; Parikh, S.; Aylin, P.; Loeffler, M. Risk Factors for Early Revision after Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty: National Observational Study from a Surgeon and Population Perspective. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Agostino, V.; Sorriento, A.; Cafarelli, A.; Donati, D.; Papalexis, N.; Russo, A.; Lisignoli, G.; Ricotti, L.; Spinnato, P. Ultrasound Imaging in Knee Osteoarthritis: Current Role, Recent Advancements, and Future Perspectives. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Long, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chin, K.Y. Osteoarthritis: An Integrative Overview from Pathogenesis to Management. Malays. J. Pathol. 2024, 46, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fogarty, A.E.; Chiang, M.C.; Douglas, S.; Yaeger, L.H.; Ambrosio, F.; Lattermann, C.; Jacobs, C.; Borg-Stein, J.; Tenforde, A.S. Posttraumatic Osteoarthritis after Athletic Knee Injury: A Narrative Review of Diagnostic Imaging Strategies. PM&R 2024, 16, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.M.C.; Pitsillides, A.A.; Meeson, R.L. Moving beyond the Limits of Detection: The Past, the Present, and the Future of Diagnostic Imaging in Canine Osteoarthritis. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 789898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, D.; Roemer, F.W.; Link, T.; Li, X.; Kogan, F.; Segal, N.A.; Omoumi, P.; Guermazi, A. Latest Advancements in Imaging Techniques in OA. Ther. Adv. Musculoskelet. Dis. 2022, 14, 1759720X221146621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piccolo, C.L.; Mallio, C.A.; Vaccarino, F.; Bernetti, C.; Agostini, F.; Pennone, M.; Corona, F.; Kitchen, F.; Palazzo, C. Imaging of Knee Osteoarthritis: A Review of Multimodal Diagnostic Approach. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2023, 13, 7582–7595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cueva, J.H.; Castillo, D.; Espinós-Morató, H.; Perez, R.; Lopez, M.; Martinez, L.; Rodriguez, J. Detection and Classification of Knee Osteoarthritis. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Roemer, F.W.; Cicuttini, F.; MacKay, J.W.; Turmezei, T.; Link, T.M. Early Knee OA Definition—What Do We Know at This Stage? An Imaging Perspective. Ther. Adv. Musculoskelet. Dis. 2023, 15, 1759720X231158204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallio, C.A.; Bernetti, C.; Agostini, F.; Palazzo, C.L.; Vaccarino, F.; Pal, M.; Longo, U.G. Advanced MR Imaging for Knee Osteoarthritis: A Review on Local and Brain Effects. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Zheng, H.; Ye, B.; Guo, T.; Xu, Y.; Fu, Z.; Ji, X.; Chai, X.; Li, S.; Deng, Q. Identification of Biomarkers for Knee Osteoarthritis through Clinical Data and Machine Learning Models. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 85945–85949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, A.; Chen, H.; Chen, T.; Li, J.; Lu, S.; Fan, T.; Zeng, D.; Wen, Z.; Ma, J.; Hunter, D.; et al. The Application of Machine Learning in Early Diagnosis of Osteoarthritis: A Narrative Review. Ther. Adv. Musculoskelet. Dis. 2023, 15, 1759720X231158198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkotis, C.; Moustakidis, S.; Giakas, G.; Tsaopoulos, D. Identification of Risk Factors and Machine Learning-Based Prediction Models for Knee Osteoarthritis Patients. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, J.; Zhang, J.; Alswadeh, M.; Zhu, Z.; Tang, J.; Sang, H.; Lu, K. Advancing Osteoarthritis Research: The Role of AI in Clinical, Imaging and Omics Fields. Bone Res. 2025, 13, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, J.; Kim, J.; Cheon, S. A Deep Neural Network-Based Method for Early Detection of Osteoarthritis Using Statistical Data. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ntakolia, C.; Kokkotis, C.; Moustakidis, S.; Tsaopoulos, D. Prediction of Joint Space Narrowing Progression in Knee Osteoarthritis Patients. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, S.; Zhang, C.; Oo, W.M.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Han, W.; Ding, C. Osteoarthritis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2025, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]