MVSegNet: A Multi-Scale Attention-Based Segmentation Algorithm for Small and Overlapping Maritime Vessels

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We introduce a new high-resolution benchmark dataset, namely MAKSEA, covering the Makkoran Coast in the southeast of Iran, annotated with quadrilateral bounding boxes to better represent small, overlapping fishing vessels in complex coastal environments.

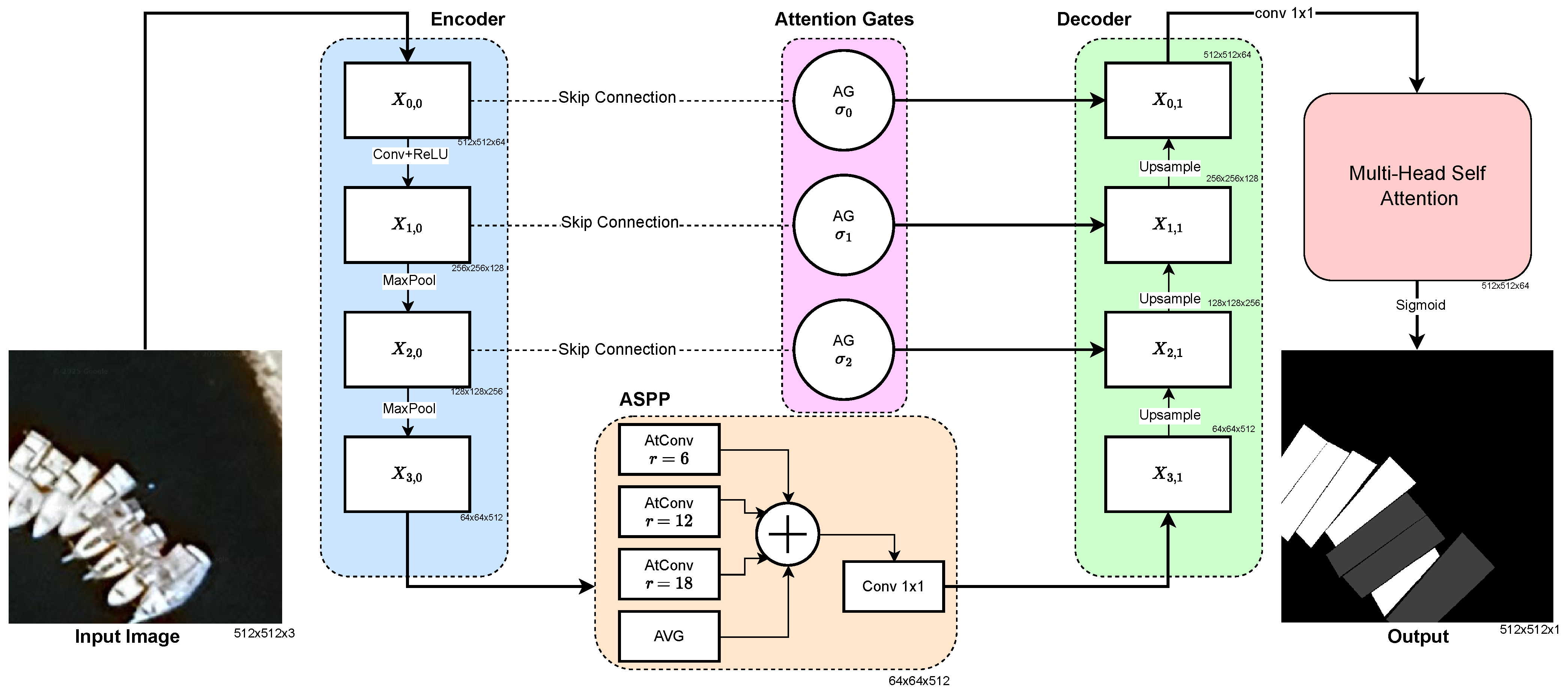

- We propose Makkoran Vessel Segmentation Network (MVSegNet), an enhanced U-Net++ architecture that integrates an Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling (ASPP) module to capture multi-scale contextual information, attention gates for noise suppression, and self-attention modules for long-range spatial dependency modeling.

- We design a lightweight module for detecting sub-pixel vessels and employ a hybrid loss function combining Binary Cross-Entropy, Dice, and Focal losses under deep supervision to improve accuracy and training stability.

- Extensive experiments on multiple benchmarks, including the proposed dataset, demonstrate that MVSegNet achieves notable improvements in IoU, precision, and recall over SoTA ship segmentation methods.

2. Related Work

2.1. Classical Ship Detection in Remote Sensing

2.2. Deep Learning-Based Ship Detection and Segmentation

2.3. Multi-Scale Feature Extraction

2.4. Attention Mechanism

2.5. Benchmark Datasets for Ship Detection and Segmentation

2.6. Automated Annotation Tools

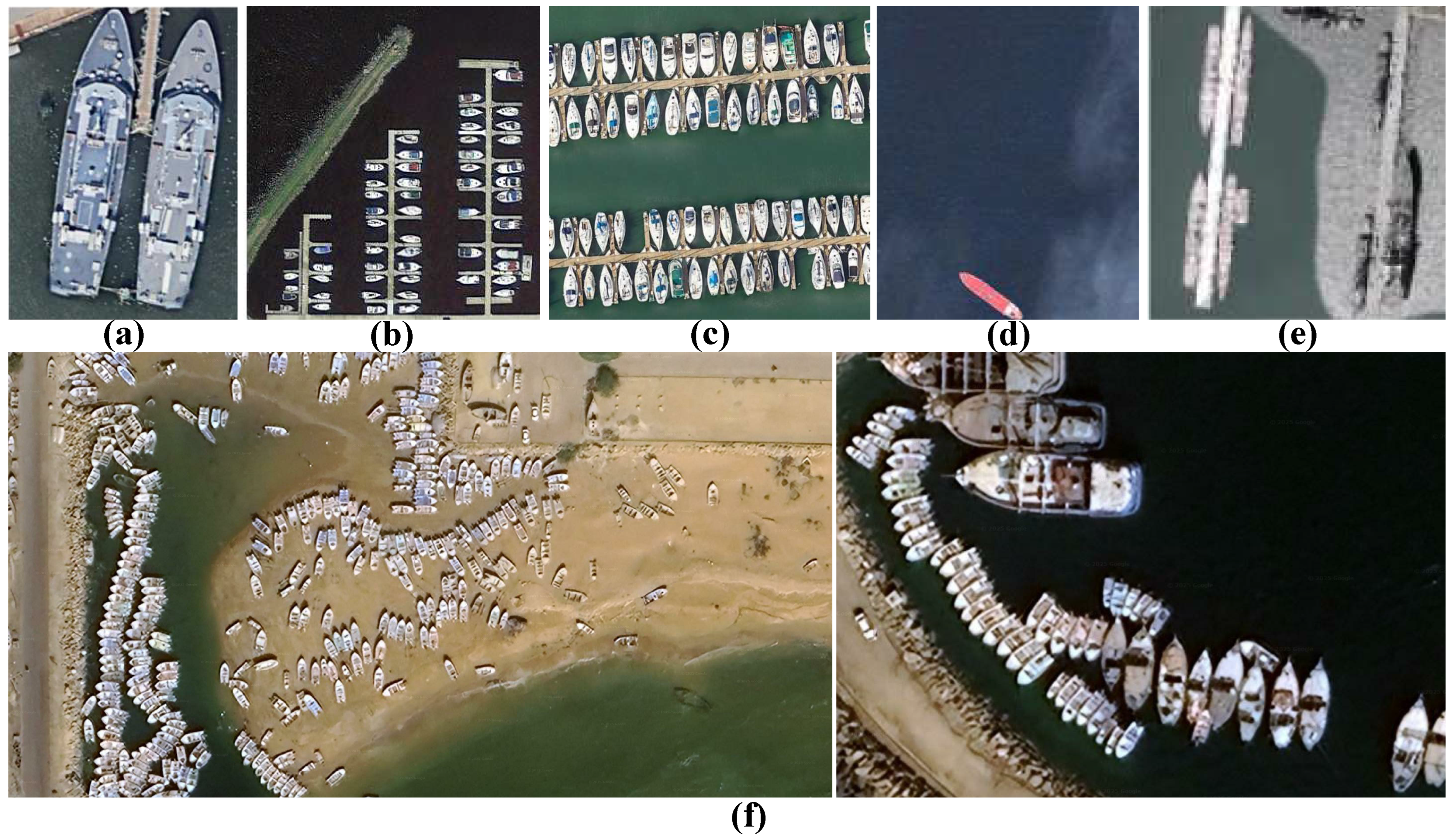

3. The Proposed Makkoran SEA (MAKSEA) Dataset

3.1. Study Area and Data Collection

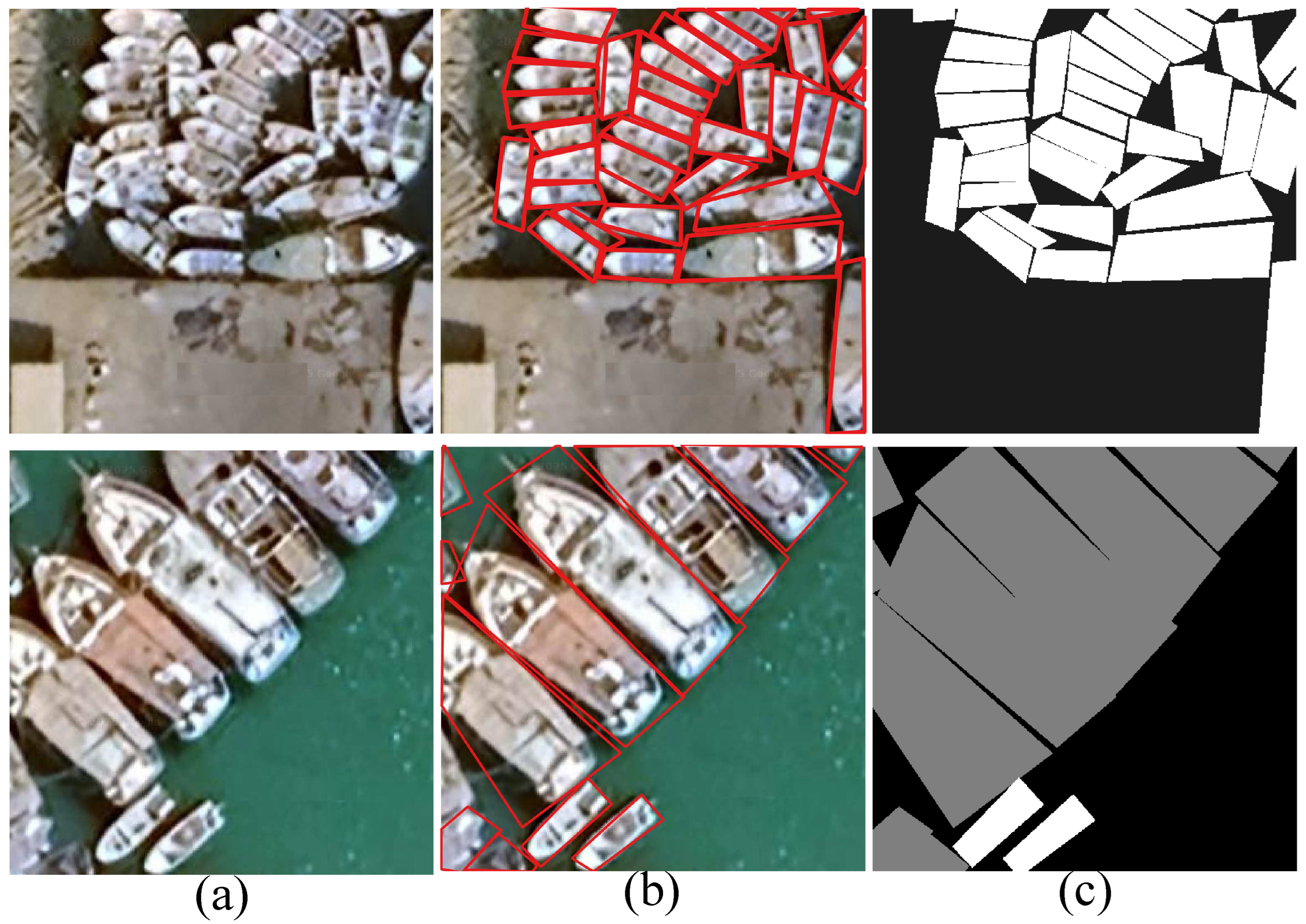

3.1.1. Annotation Protocol

3.1.2. Dataset Statistics

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Architecture Overview

4.2. Enhanced U-Net++ Backbone with Dense Skip Connections

4.2.1. Dense Connectivity Formulation

4.2.2. Feature Processing at Each Level

4.3. Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling (ASPP) Module

4.3.1. Multi-Scale Context Extraction

4.3.2. Atrous Convolution Formulation

4.3.3. Global Context Integration

4.3.4. Feature Fusion and Output

4.4. Attention Gate Mechanisms

4.5. Multi-Head Self-Attention Module

4.5.1. Self-Attention Mechanism

4.5.2. Multi-Head Attention Formulation

4.5.3. Positional Encoding Integration

4.6. Loss Function Design

5. Experimental Results

5.1. Datasets

5.1.1. DIOR_SHIP Dataset

5.1.2. LEVIR_SHIP Dataset

5.1.3. MAKSEA Dataset

5.2. Evaluation Metrics

5.3. Implementation Details

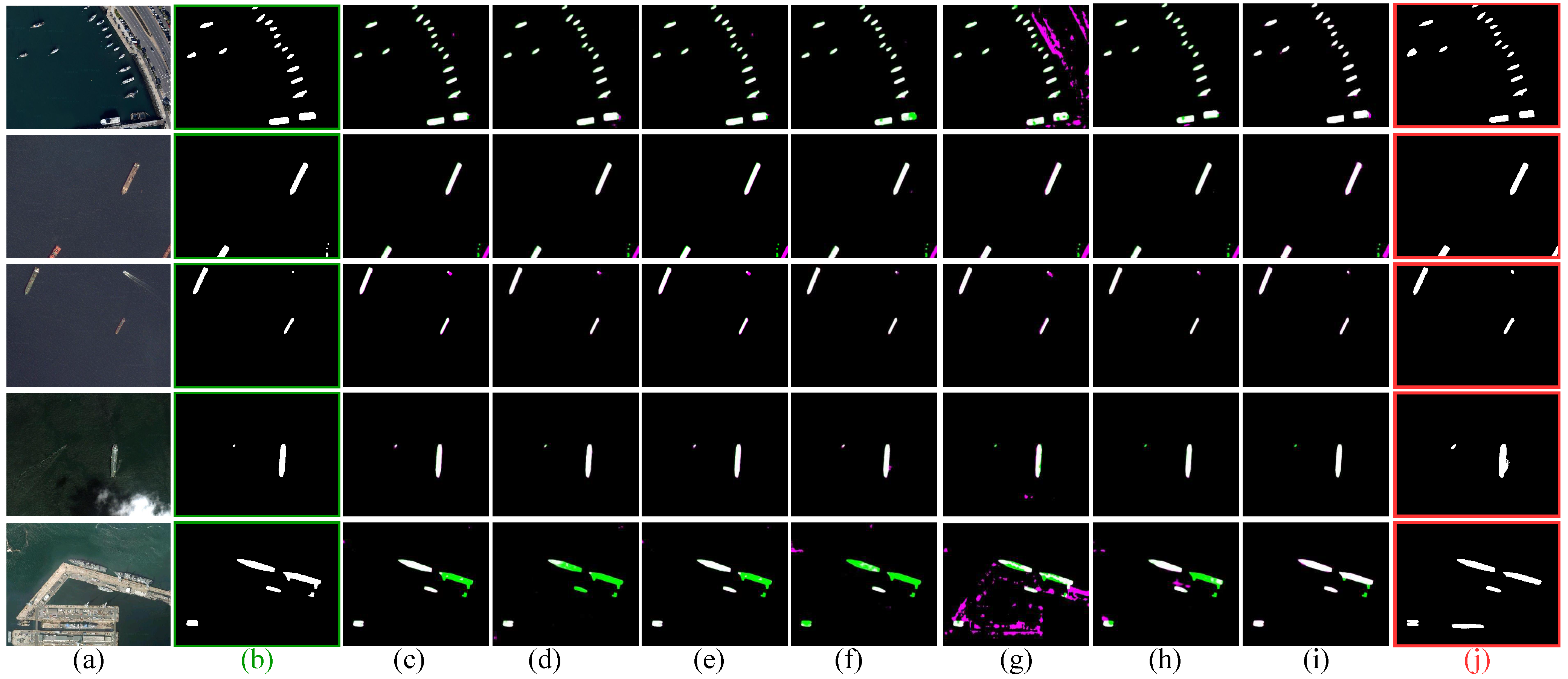

5.4. Quantitative and Qualitative Comparison Against SoTA Methods

5.4.1. DIOR_SHIP Benchmark Dataset

5.4.2. LEVIR_SHIP Benchmark Dataset

5.4.3. Comparison of SoTA Models on MAKSEA Dataset

5.5. Ablation Experiments

5.5.1. Effect of the Utilized Components on the Proposed Model

5.5.2. Ablation Study on Vessel Size and Geodetic Area Analysis

5.5.3. Cross-Dataset Generalization

5.5.4. Computational Efficiency

5.6. Discussion

5.6.1. Interpretation of Results

5.6.2. Limitations and Future Work

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MVSegNet | Makkoran Vessel Segmentation Network |

| SoTA | State of The Art |

| IoU | Intersection over Union |

| ASPP | Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling |

| CNNs | Convolutional Neural Networks |

References

- Kanjir, U.; Greidanus, H.; Štir, K. Vehicle Detection in Very High Resolution Satellite Images of City Areas. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2018, 56, 2311–2323. [Google Scholar]

- Corbane, C.; Carrion, D.; Lemoine, G.; Broglia, M. Rapid Damage Assessment Using High Resolution Satellite Imagery and Semi-Automatic Object-Based Image Analysis: The Case of the 2003 Bam Earthquake. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 2008, 74, 1021–1035. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, K.; Bhatt, C.; Mazzeo, P.L. Deep Learning-Based Automatic Detection of Ships: An Experimental Study Using Satellite Images. J. Imaging 2022, 8, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reggiannini, M.; Salerno, E.; Bacciu, C.; D’Errico, A.; Lo Duca, A.; Marchetti, A.; Martinelli, M.; Mercurio, C.; Mistretta, A.; Righi, M.; et al. Remote Sensing for Maritime Traffic Understanding. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, D.; Hu, J.; Zhi, X.; Yang, D. FANT-Det: Flow-Aligned Nested Transformer for SAR Small Ship Detection. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Gao, Y.; Chen, C.; Feng, H.; Zhao, Z. Ship Detection with Deep Learning in Optical Remote-Sensing Images: A Survey of Challenges and Advances. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhou, Z.; Luo, R.; Zhao, L.; Liu, L. Small Ship Detection in SAR Images Based on Asymmetric Feature Learning and Shallow Context Embedding. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 28466–28479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbane, C.; Najman, L.; Pecoul, E.; Demagistri, L.; Petit, M. A Complete Processing Chain for Ship Detection Using Optical Satellite Imagery. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2010, 31, 5837–5854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, X.; Ji, K.; Yang, K.; Zou, H. Ship Detection Based on Fusion of Multi-Feature and Sparse Representation in High-Resolution SAR Images. J. Syst. Eng. Electron. 2015, 26, 736–743. [Google Scholar]

- Dalal, N.; Triggs, B. Histograms of Oriented Gradients for Human Detection. In Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR’05), San Diego, CA, USA, 20–25 June 2005; Volume 1, pp. 886–893. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, D.G. Distinctive Image Features from Scale-Invariant Keypoints. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2004, 60, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, C.; Vapnik, V. Support-Vector Networks. Mach. Learn. 1995, 20, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasir, M.; Jianhua, W.; Mingming, X.; Hui, S.; Zhe, Z.; Shanwei, L.; Colak, A.T.I.; Hossain, M.S. Ship Detection Based on Deep Learning Using SAR Imagery: A Systematic Literature Review. Soft Comput. 2023, 27, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Han, J.; Zhou, P.; Guo, L. Multi-Feature Fusion for Ship Detection in Optical Satellite Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2014, 52, 4992–5004. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidhuber, J. Deep Learning in Neural Networks: An Overview. Neural Netw. 2015, 61, 85–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep Learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Yao, J.; Zhang, K.; Feng, C.; Zhang, J. A Deep Learning Approach for Ship Detection from Satellite Imagery. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2016, 5, 142. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. YOLOv3: An Incremental Improvement. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.02767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Hu, J.; Weng, L.; Yang, Y. HRSC2016: A High-Resolution Ship Collection for Ship Detection in Optical Remote Sensing Images. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), Fort Worth, TX, USA, 23–28 July 2017; pp. 620–623. [Google Scholar]

- Airbus, A. Airbus Ship Detection Challenge. 2018. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/c/airbus-ship-detection (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Zou, Z.; Shi, Z. Random Access Memories: A New Paradigm for Target Detection in High Resolution Aerial Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2018, 27, 1100–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Wan, G.; Cheng, G.; Meng, L.; Han, J. Object Detection in Optical Remote Sensing Images: A Survey and a New Benchmark. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2020, 159, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 7–12 December 2015; pp. 91–99. [Google Scholar]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Girshick, R. Fast R-CNN. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 1440–1448. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Spatial Pyramid Pooling in Deep Convolutional Networks for Visual Recognition. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Zurich, Switzerland, 6–12 September 2014; pp. 346–361. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.-Y.; Berg, A.C. SSD: Single Shot MultiBox Detector. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Long, J.; Shelhamer, E.; Darrell, T. Fully Convolutional Networks for Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 3431–3440. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R. Mask R-CNN. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2961–2969. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Rahman Siddiquee, M.M.; Tajbakhsh, N.; Liang, J. UNet++: A Nested U-Net Architecture for Medical Image Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2018, 39, 1856–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badrinarayanan, V.; Kendall, A.; Cipolla, R. SegNet: A Deep Convolutional Encoder-Decoder Architecture for Image Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 39, 2481–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-C.; Zhu, Y.; Papandreou, G.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H. Encoder-Decoder with Atrous Separable Convolution for Semantic Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 801–818. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, E.; Wang, W.; Yu, Z.; Anandkumar, A.; Alvarez, J.M.; Luo, P. SegFormer: Simple and Efficient Design for Semantic Segmentation with Transformers. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), Virtual, 6–14 December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, G.; Xu, G.; Yu, Y.; Xie, J.; Yang, J.; Yue, D. MSCFNet: A lightweight network with multi-scale context fusion for real-time semantic segmentation. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 23, 25489–25499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Xie, J.; Chen, M.; Chen, H.; Liu, W. MA-UNet++: A multi-attention guided U-Net++ for COVID-19 CT segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2022 13th Asian Control Conference (ASCC), Jeju, Republic of Korea, 4–7 May 2022; pp. 682–687. [Google Scholar]

- Niyogisubizo, J.; Zhao, K.; Meng, J.; Pan, Y.; Didi, R.; Wei, Y. Attention-guided residual U-Net with SE connection and ASPP for watershed-based cell segmentation in microscopy images. J. Comput. Biol. 2025, 32, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhu, C.; Lian, X.; Hua, F. A nested attention guided UNet++ architecture for white matter hyperintensity segmentation. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 66910–66920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zou, B.; Guo, Z.; Huang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Qin, F.; Li, Q.; Wang, C. SCUNet++: Swin-UNet and CNN bottleneck hybrid architecture with multi-fusion dense skip connection for pulmonary embolism CT image segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–8 January 2024; pp. 7759–7767. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, N.; Lu, Z.; Lian, W.; Tian, M.; Ma, C.; Peng, L. HMSAM-UNet: A hierarchical multi-scale attention module-based convolutional neural network for improved CT image segmentation. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 79415–79427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, L.; Phung, S.L.; Di, Y.; Le, H.T.; Nguyen, T.T.P.; Burden, S.; Bouzerdoum, A. UOW-Vessel: A Benchmark Dataset of High-Resolution Optical Satellite Images for Vessel Detection and Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Workshop on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–7 January 2024; pp. 4416–4424. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, G.-S.; Bai, X.; Ding, J.; Zhu, Z.; Belongie, S.J.; Luo, J.; Datcu, M.; Pelillo, M.; Zhang, L. DOTA: A Large-Scale Dataset for Object Detection in Aerial Images. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bovolo, F.; Bruzzone, L.; Marconcini, M. A Novel Approach to Unsupervised Change Detection Based on a Semisupervised SVM and a Similarity Measure. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2008, 46, 2070–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Shi, Z. Ship Detection in Spaceborne Optical Image with SVD Networks. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2016, 54, 5832–5845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, H. A Robust Ship Detection Method for SAR Images. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2019, 16, 768–772. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Tong, L.; Cao, Y.; Xue, Z. A Deep Learning Method for Ship Detection in Optical Satellite Images. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2020, 13, 5234–5247. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Duan, T.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, M. End-to-End Ship Detection in SAR Images for Complex Scenes Based on Deep CNNs. J. Sens. 2021, 2021, 8893182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Li, M.; Ma, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L. SAR Ship Detection Using Deep Learning. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2017, 14, 1154–1158. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, S.; Su, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, X. Surface Ship Detection in SAR Images Based on Deep Learning. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2019, 12, 3792–3803. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; Van Der Maaten, L.; Weinberger, K.Q. Densely Connected Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 4700–4708. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.; Lin, L.; Tong, R.; Hu, H.; Zhang, Q.; Iwamoto, Y.; Han, X.; Chen, Y.-W.; Wu, J. UNet 3+: A Full-Scale Connected UNet for Medical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2020—2020 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Barcelona, Spain, 4–8 May 2020; pp. 1055–1059. [Google Scholar]

- Ibtehaz, N.; Rahman, M.S. MultiResUNet: Rethinking the U-Net Architecture for Multimodal Biomedical Image Segmentation. Neural Netw. 2020, 121, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, X.; Shi, J.; Wei, S.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Su, H.; Zhou, Y.; Ye, H. Ship Detection in SAR Images Based on Multi-Scale Feature Extraction and Adaptive Feature Fusion. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 536. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Hariharan, B.; Belongie, S. Feature Pyramid Networks for Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 2117–2125. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, F.; Koltun, V. Multi-Scale Context Aggregation by Dilated Convolutions. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), San Juan, Puerto Rico, 2–4 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.-C.; Papandreou, G.; Kokkinos, I.; Murphy, K.; Yuille, A.L. Deeplab: Semantic Image Segmentation with Deep Convolutional Nets, Atrous Convolution, and Fully Connected CRFs. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2018, 40, 834–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; He, C.; Liu, A.; Lv, X.; He, P.; Lv, Z. Dense Connection and Depthwise Separable Convolution Based CNN for Polarimetric SAR Image Classification. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2020, 194, 105584. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M.; Yu, K.; Zhang, C.; Li, Z.; Yang, K. DenseASPP for Semantic Segmentation in Street Scenes. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 3684–3692. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- Raisi, Z.; Naiel, M.A.; Younes, G.; Wardell, S.; Zelek, J.S. Transformer-Based Text Detection in the Wild. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) Workshops, Nashville, TN, USA, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 3162–3171. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Lu, Y.; Yu, Q.; Luo, X.; Adeli, E.; Wang, Y.; Lu, L.; Yuille, A.L.; Zhou, Y. Transunet: Transformers Make Strong Encoders for Medical Image Segmentation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.04306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktay, O.; Schlemper, J.; Folgoc, L.L.; Lee, M.; Heinrich, M.; Misawa, K.; Mori, K.; McDonagh, S.; Hammerla, N.Y.; Kainz, B.; et al. Attention U-Net: Learning Where to Look for the Pancreas. In Proceedings of the Medical Imaging with Deep Learning, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 4–6 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ciocarlan, A.; Stoian, M. Ship Detection in Sentinel-2 Multi-Spectral Images with Self-Supervised and Transfer Learning. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kızılkaya, S.; Alganci, U.; Sertel, E. VHRShips: An Extensive Benchmark Dataset for Scalable Ship Detection from Google Earth Images. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirillov, A.; Mintun, E.; Ravi, N.; Mao, H.; Rolland, C.; Gustafson, L.; Xiao, T.; Whitehead, S.; Berg, A.C.; Lo, W.Y.; et al. Segment anything. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023; pp. 4015–4026. [Google Scholar]

- Ravi, N.; Gabeur, V.; Hu, Y.T.; Hu, R.; Ryali, C.; Ma, T.; Khedr, H.; Rädle, R.; Rolland, C.; Gustafson, L.; et al. SAM 2: Segment anything in images and videos. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Conference on Learning Representations, Singapore, 24–28 April 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, J.; Du, B.; Xu, M.; Liu, L.; Tao, D.; Zhang, L. Samrs: Scaling-up remote sensing segmentation dataset with segment anything model. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2023, 36, 8815–8827. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, Q.; Liu, J.; Xiong, H. ALPS: An auto-labeling and pre-training scheme for remote sensing segmentation with segment anything model. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2025, 34, 2408–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, R.; Yuan, Y.; Xu, X.; Yin, S.; Chen, Z.; Zeng, H.; Wang, Z. MambaSegNet: A Fast and Accurate High-Resolution Remote Sensing Imagery Ship Segmentation Network. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Ji, S.; Lu, M. Toward Automatic Building Footprint Delineation from Aerial Images Using CNN and Regularization. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2020, 58, 2178–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loshchilov, I.; Hutter, F. Decoupled Weight Decay Regularization. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, New Orleans, LA, USA, 6–9 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Jiang, Y.; Li, M.; Yin, S. Attention-Based U-Net for Retinal Vessel Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2018 24th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR), Beijing, China, 20–24 August 2018; pp. 3949–3954. [Google Scholar]

| Datasets | Source | # Images | Pixel Size | Class | Resolution (m) | Band | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRSC2016 [20] | Google Earth | 1061 | Various sizes | 1 | 0.4–2 | RGB | 2016 |

| DIOR_SHIP [70] | Google Earth | 1258 | 1 | 0.5–30 | RGB | 2025 | |

| LEVIR_SHIP [70] | Google Earth | 1461 | 1 | 0.2–1 | RGB | 2025 | |

| MAKSEA | Google Earth | 8438 | 1 | 0.5–10 | RGB | This work |

| Framework | IOU | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Inference Time (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unet [26] | 0.7650 | 0.8320 | 0.8060 | 0.7820 | 0.7940 | 87.70 |

| Unet++ [32] | 0.7880 | 0.8470 | 0.8290 | 0.8430 | 0.8239 | 125.2 |

| DeepLabV3+ [34] | 0.7923 | 0.8520 | 0.8300 | 0.8509 | 0.8403 | 119.1 |

| segNet [33] | 0.6700 | 0.8680 | 0.8380 | 0.8670 | 0.8609 | 118.3 |

| segformer [35] | 0.7791 | 0.8776 | 0.8441 | 0.8776 | 0.8758 | 61.90 |

| TransUNet [62] | 0.8296 | 0.9903 | 0.9263 | 0.9114 | 0.9169 | 174.0 |

| MambaSegNet [70] | 0.8208 | 0.9176 | 0.9276 | 0.9076 | 0.9176 | 91.20 |

| MVSegNet (Ours) | 0.8611 | 0.9542 | 0.9683 | 0.9534 | 0.9607 | 65.40 |

| Framework | IOU | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Inference Time (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U-Net [26] | 0.5980 | 0.7810 | 0.7400 | 0.7250 | 0.7324 | 87.70 |

| U-Net++ [32] | 0.7330 | 0.7970 | 0.8300 | 0.8450 | 0.8374 | 125.2 |

| DeepLabV3+ [34] | 0.7789 | 0.8030 | 0.8030 | 0.6830 | 0.7382 | 119.1 |

| segNet [33] | 0.6850 | 0.8160 | 0.8130 | 0.7850 | 0.7988 | 118.3 |

| segformer [35] | 0.5603 | 0.7606 | 0.7260 | 0.7106 | 0.7182 | 61.90 |

| TransUNet [62] | 0.7292 | 0.9970 | 0.8346 | 0.8335 | 0.8177 | 174.0 |

| MambaSegNet [70] | 0.8094 | 0.8595 | 0.8695 | 0.8995 | 0.8795 | 91.20 |

| MVSegNet (Ours) | 0.8324 | 0.8736 | 0.8924 | 0.9135 | 0.9028 | 65.40 |

| Method | mIoU | Dice | Precision | Recall | AP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mask-RCNN [31] | 0.681 | 0.743 | 0.710 | 0.723 | 0.694 |

| FCN [30] | 0.695 | 0.761 | 0.731 | 0.733 | 0.711 |

| U-Net [26] | 0.723 | 0.812 | 0.784 | 0.795 | 0.756 |

| U-Net++ [32] | 0.756 | 0.834 | 0.816 | 0.823 | 0.789 |

| DeepLabV3+ [34] | 0.782 | 0.851 | 0.839 | 0.841 | 0.815 |

| SegNet [33] | 0.764 | 0.844 | 0.828 | 0.829 | 0.842 |

| Seg-Former [35] | 0.796 | 0.850 | 0.842 | 0.838 | 0.826 |

| Attention U-Net [63] | 0.791 | 0.859 | 0.847 | 0.852 | 0.823 |

| TransUNet [62] | 0.803 | 0.868 | 0.861 | 0.863 | 0.839 |

| SCUNet++ [40] | 0.783 | 0.862 | 0.841 | 0.849 | 0.822 |

| MVSegNet (Ours) | 0.826 | 0.885 | 0.879 | 0.881 | 0.857 |

| Configuration | IoU | Dice | Precision | Recall | AP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (U-Net++) | 0.756 | 0.834 | 0.816 | 0.823 | 0.789 |

| +ASPP | 0.793 | 0.862 | 0.849 | 0.853 | 0.827 |

| +Attention Gates | 0.812 | 0.876 | 0.865 | 0.868 | 0.843 |

| +Self-Attention | 0.826 | 0.885 | 0.879 | 0.881 | 0.857 |

| Full Model (MVSegNet) | 0.826 | 0.885 | 0.879 | 0.881 | 0.857 |

| Attention Configuration | IoU | Dice | Precision | Recall |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Attention | 0.793 | 0.862 | 0.849 | 0.853 |

| Attention Gates Only | 0.812 | 0.876 | 0.865 | 0.868 |

| Self Attention Only | 0.805 | 0.869 | 0.857 | 0.861 |

| Both Attention (MVSegNET) | 0.826 | 0.885 | 0.879 | 0.881 |

| Size Category | IoU | Dice | Precision | Recall |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small (≤20 m2) | 0.781 | 0.852 | 0.843 | 0.847 |

| Medium (20 m2–200 m2) | 0.832 | 0.889 | 0.883 | 0.885 |

| Large (≥200 m2) | 0.845 | 0.896 | 0.891 | 0.893 |

| Average | 0.826 | 0.885 | 0.879 | 0.881 |

| Training | Testing | IoU | Dice | Precision | Recall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DIOR_SHIP | MAKSEA | 0.698 | 0.767 | 0.754 | 0.759 |

| LEVIR_SHIP | MAKSEA | 0.712 | 0.776 | 0.768 | 0.771 |

| MAKSEA | LEVIR_SHIP | 0.789 | 0.841 | 0.867 | 0.892 |

| MAKSEA | DIOR_SHIP | 0.803 | 0.861 | 0.869 | 0.902 |

| Method | Params (M) | FLOPs (G) | Inference Time (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|

| U-Net [26] | 66.80 | 218 | 97.50 |

| U-Net++ [32] | 79.40 | 283 | 136.2 |

| DeepLabV3+ [34] | 34.20 | 162 | 104.1 |

| Attention U-Net [73] | 41.50 | 238 | 78.70 |

| TransUNet [62] | 105.3 | 385 | 182.3 |

| Ours | 24.70 | 115 | 65.40 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Raisi, Z.; Had, V.N.; Damani, R.; Sarani, E. MVSegNet: A Multi-Scale Attention-Based Segmentation Algorithm for Small and Overlapping Maritime Vessels. Algorithms 2026, 19, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/a19010023

Raisi Z, Had VN, Damani R, Sarani E. MVSegNet: A Multi-Scale Attention-Based Segmentation Algorithm for Small and Overlapping Maritime Vessels. Algorithms. 2026; 19(1):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/a19010023

Chicago/Turabian StyleRaisi, Zobeir, Valimohammad Nazarzehi Had, Rasoul Damani, and Esmaeil Sarani. 2026. "MVSegNet: A Multi-Scale Attention-Based Segmentation Algorithm for Small and Overlapping Maritime Vessels" Algorithms 19, no. 1: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/a19010023

APA StyleRaisi, Z., Had, V. N., Damani, R., & Sarani, E. (2026). MVSegNet: A Multi-Scale Attention-Based Segmentation Algorithm for Small and Overlapping Maritime Vessels. Algorithms, 19(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/a19010023