Abstract

Student dropout prediction remains critical in higher education, where timely identification enables effective interventions. Learning Management Systems (LMSs) capture rich temporal data reflecting student behavioral evolution, yet existing approaches underutilize this sequential information. Traditional machine learning methods aggregate behavioral data into static features, discarding dynamic patterns that distinguish successful from at-risk students. While Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks model sequences, they assume discrete time steps and struggle with irregular LMS observation intervals. To address these limitations, we introduce Completion-aware Risk Neural Ordinary Differential Equations (CR-NODE), integrating continuous-time dynamics with completion-focused features for early dropout prediction. CR-NODE employs Neural ODEs to model student behavioral evolution through continuous differential equations, naturally accommodating irregular observation patterns. Additionally, we engineer three completion-focused features: completion rate, early warning score, and engagement variability, derived from root cause analysis. Evaluated on Canvas LMS data from 100,878 enrollments across 89,734 temporal sequences, CR-NODE achieves Macro F1 of 0.8747, significantly outperforming LSTM (0.8123), Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) (0.8300), and basic Neural ODE (0.8682). McNemar’s test confirms statistical significance (). Cross-dataset validation on the Open University Learning Analytics Dataset (OULAD) demonstrates generalizability, achieving 84.44% accuracy versus state-of-the-art LSTM (83.41%). To support transparent decision-making, SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) analysis reveals completion patterns as the primary prediction drivers.

1. Introduction

Student dropout remains a critical challenge in higher education, with significant implications for institutional effectiveness and student success. Early identification of at-risk students enables timely interventions that can improve retention rates and academic outcomes. Traditional approaches to dropout prediction have primarily relied on static features and conventional machine learning methods, which fail to capture the dynamic nature of student behavior throughout a course.

Recent advances in educational data mining and learning analytics have demonstrated the value of temporal modeling for understanding student learning patterns [1,2]. Learning Management Systems (LMSs) such as Canvas generate rich longitudinal data capturing student interactions, assignment submissions, and engagement over time. Macfadyen and Dawson [3] pioneered the use of LMS data for early warning systems, demonstrating that student activity patterns contain predictive signals for academic risk. However, most existing prediction models treat these temporal sequences as aggregated statistics, losing critical information about behavioral trajectories and engagement patterns that distinguish successful students from those at risk of failure [4,5].

The application of machine learning to student performance prediction has evolved considerably. Traditional approaches using Random Forest, Logistic Regression, and Support Vector Machines have shown promising results when applied to static feature representations [6,7]. More recently, ensemble methods such as Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) have achieved strong performance [8]. Aouarib et al. [9] demonstrated the effectiveness of genetic algorithms combined with XGBoost for dropout prediction in Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs), achieving high accuracy. However, these methods fundamentally treat student data as static snapshots rather than continuous temporal processes.

Temporal modeling approaches have emerged to address this limitation. Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks [10] have been successfully applied to student dropout prediction by capturing sequential dependencies in learning behaviors [11,12]. Fei and Yeung [13] introduced temporal models for predicting student dropout in MOOCs, demonstrating that recurrent architectures can learn meaningful representations from time series data. Despite these advances, LSTM networks suffer from discrete time assumptions and difficulty handling irregularly sampled observations common in real-world educational data.

Neural Ordinary Differential Equations (Neural ODEs), introduced by Chen et al. [14], offer a powerful framework for modeling continuous-time dynamics. Unlike discrete recurrent architectures, Neural ODEs parameterize the continuous dynamics of hidden states using ordinary differential equations, enabling natural handling of irregular time intervals. Rubanova et al. [15] extended this framework to handle irregularly sampled time series through Latent ODEs. While Neural ODEs have been successfully applied in various domains, their application to educational data mining remains limited.

A critical gap in existing approaches is the failure to explicitly model assignment completion patterns, despite extensive evidence that missing work is a primary cause of student failure. Márquez-Vera et al. [16] identified that early dropout detection requires careful feature selection focused on engagement and completion indicators. This observation motivates our completion-focused approach, which extends temporal modeling with three novel engineered features: completion rate, early warning score, and engagement variability.

The challenge of model interpretability in student risk prediction has gained increasing attention [17,18]. Adadi and Berrada [19] surveyed explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) techniques, emphasizing the importance of transparency in educational applications. SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP), introduced by Lundberg and Lee [20], provides a unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Recent work has demonstrated the effectiveness of SHAP for understanding student dropout models [21], though prior studies have focused primarily on static feature importance rather than temporal behavioral patterns.

In this paper, we introduce Completion-aware Risk Neural ODE (CR-NODE), a temporal deep learning algorithm that integrates completion-focused features with Neural ODE dynamics for early student risk detection. Our contributions are (1) a CR-NODE architecture combining temporal behavioral sequences with completion-focused static features, (2) three engineered features capturing assignment completion patterns critical for identifying at-risk students, (3) comprehensive evaluation against six baselines including LSTM, XGBoost, and basic Neural ODE with statistical significance testing, and (4) explainable AI analysis using SHAP revealing interpretable failure patterns and root causes.

Our experiments on Canvas LMS data from 100,878 students across 89,734 temporal sequences demonstrate that CR-NODE achieves a 0.8747 Macro F1 score, significantly outperforming LSTM (0.8123), XGBoost (0.8300), and basic Neural ODE without completion features (0.8682). McNemar’s test [22] confirms statistical significance with p-values less than 0.0001 for all baseline comparisons.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews related work in educational data mining and temporal modeling. Section 3 describes the CR-NODE algorithm and methodology. Section 4 presents the experimental setup and results. Section 5 provides the explainable AI analysis. Section 6 discusses implications and limitations. Section 6 concludes with future directions.

2. Related Work

2.1. Educational Data Mining and Predictive Approaches

Educational data mining (EDM) and learning analytics have evolved significantly, with comprehensive surveys documenting the progression from traditional statistical methods to sophisticated machine learning approaches [1,2]. Early warning systems represent a foundational application, with pioneering work demonstrating that LMS activity data including discussion board posts, content access patterns, and interaction logs can predict student performance [3,23]. Subsequent research identified optimal feature sets including clicking behavior, time spent, session counts, and assignment scores as strong predictors, though model portability across courses remains challenging due to varying course structures [4,5,24].

Traditional machine learning approaches including Naive Bayes, decision trees, and ensemble methods have been extensively applied to student dropout prediction using static features [6,25]. More recent work has achieved strong performance with advanced ensemble methods; Márquez-Vera et al. [16] achieved reliable predictions within 4–6 weeks and identified missing assignments as a critical predictor, while Aouarib et al. [9] combined genetic algorithms with XGBoost achieving 91.67% accuracy, and Costa et al. [7] confirmed that ensemble methods generally outperform single classifiers. Despite strong performance, these approaches share a fundamental limitation: they aggregate temporal information into summary statistics, losing information about behavioral trajectories that distinguish different risk profiles requiring different interventions.

Recognition of temporal dynamics has motivated the application of sequential models to educational data. Fei and Yeung [13] demonstrated that temporal models including HMMs and RNNs improved dropout prediction over static approaches, while Whitehill et al. [26] applied feature engineering with temporal analysis for MOOC dropout detection. Deep learning approaches have shown promise: Wang et al. [27] proposed CNN-based models for automatic feature learning, Basnet et al. [11] found deep learning to be comparable to traditional methods with advantages in feature extraction, and Hassan et al. [12] achieved 97.25% accuracy using LSTM networks. Related work in Deep Knowledge Tracing [28,29,30] has applied LSTMs to model student knowledge states, inspiring extensions for educational prediction tasks.

2.2. Neural Ordinary Differential Equations

Neural ODEs, introduced by Chen et al. [14], represent hidden state dynamics as continuous-time ordinary differential equations rather than discrete recurrent updates. This formulation provides natural handling of irregularly-sampled observations, memory-efficient gradient computation through the adjoint sensitivity method, and explicit modeling of continuous temporal dynamics. Rubanova et al. [15] extended Neural ODEs to handle latent dynamics in irregularly sampled time series, demonstrating superior performance on sparse temporal data compared to RNN-based approaches. Further extensions include Augmented Neural ODEs [31] for improved representational capacity and Neural Controlled Differential Equations [32] achieving state-of-the-art results on irregular time series benchmarks.

Despite theoretical advantages and strong performance in domains such as healthcare and finance, Neural ODEs have seen limited application to educational data mining, and their potential for student dropout prediction remains largely unexplored.

2.3. Explainable AI in Education

Explainable AI techniques have become essential for educational applications where both accuracy and interpretability are critical [19]. SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) [20] provides a unified framework for interpreting model predictions, and has been applied to student dropout prediction to guide intervention strategies [21]. Alternative approaches such as LIME [33] offer local explanations but lack the theoretical guarantees and global consistency properties of SHAP.

Ethical considerations in educational AI extend to fairness and bias. Holmes et al. [18] proposed a community-wide framework emphasizing transparency, fairness, and human oversight, while Slade and Prinsloo [17] identified ethical dilemmas including privacy, consent, and potential for discrimination. Recent work has addressed fairness explicitly through counterfactual fairness evaluation [34], investigation of perceived fairness among students [35], and privacy-preserving federated learning approaches [36].

2.4. Gap Analysis and Our Contributions

Existing work on student dropout prediction exhibits three critical gaps that our research addresses. First, despite strong performance of ensemble methods like XGBoost on static features, these approaches fail to capture temporal dynamics of student behavior. While LSTM networks model temporal sequences, they assume discrete time and struggle with irregularly sampled LMS data. Neural ODEs offer theoretical advantages for continuous-time modeling but have not been applied to educational risk prediction.

Second, prior work has not explicitly focused on assignment completion patterns despite extensive evidence that missing work is a primary cause of failure. Existing models include completion-related features implicitly through aggregate statistics, but do not engineer features specifically designed to capture completion trajectories and early warning signals.

Third, while explainable AI techniques have been applied to static dropout models, temporal pattern analysis revealing how at-risk students diverge from successful students over time remains underexplored. Understanding not just which features are important but when and how behavioral trajectories differ is essential for timing interventions effectively.

CR-NODE addresses these gaps by combining Neural ODE temporal modeling with engineered completion-focused features and providing comprehensive explainable AI analysis including temporal pattern visualization and root cause identification.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Dataset and Preprocessing

We conducted experiments using Canvas Learning Management System data collected from a large public university over multiple academic terms. The dataset comprises comprehensive longitudinal records of student interactions, assignment submissions, communication patterns, and final outcomes across diverse course offerings. Table 1 summarizes the complete dataset characteristics.

Table 1.

Canvas LMS dataset characteristics.

The data includes 100,878 student enrollments with final grade information, from which we extracted 89,734 valid temporal sequences satisfying minimum observation requirements. Student success was defined as achieving a final score of 70% or higher, resulting in a binary classification task. The test set exhibits class distribution of 71.9% passing students and 28.1% failing students, reflecting realistic educational settings where class imbalance necessitates careful evaluation using metrics appropriate for imbalanced data [37].

Data preprocessing involved several steps to ensure temporal consistency and data quality. All timestamps were converted to hours elapsed since course start using UTC timezone normalization. We filtered observations to the first 10 weeks (1680 h) of each course, corresponding to the period when early intervention is most effective [16]. Temporal sequences were aggregated into 4 h time buckets to reduce noise while preserving fine-grained behavioral patterns; however, students exhibit activity only in a subset of buckets, resulting in non-uniform intervals between consecutive observations. For students with sequences exceeding 60 observations, we applied uniform downsampling using linear interpolation to maintain temporal coverage while limiting computational requirements. Sequences with fewer than 3 observations were excluded as insufficient for temporal modeling. The dataset was partitioned into training and test sets using stratified random sampling with 80-20 split ratio and random seed 42 for reproducibility.

3.2. Feature Engineering

Our feature set comprises temporal features capturing time-varying student behavior and static features representing cumulative course performance. Table 2 provides complete definitions for all features used in this study.

Table 2.

Feature definitions and descriptions.

The four temporal features capture student behavior across complementary dimensions: page_views measures engagement intensity through LMS access frequency, submission_score quantifies academic performance on submitted work, late_count tracks time management patterns, and messages reflects communication activity with instructors. These features are observed at each 4 h time bucket throughout the course duration, enabling continuous-time modeling of behavioral dynamics.

The static features consist of two categories. The eight baseline static features represent standard predictors commonly used in educational data mining [1], including cumulative activity time, current grade standing, submission counts and scores, and communication volume. These features aggregate student behavior over the entire observation period.

The three completion-focused features were engineered specifically to capture assignment completion patterns identified through root cause analysis of failing students. The completion rate measures the proportion of expected coursework completed, defined mathematically as

where expected_submissions represents the unique assignment count per course, and the denominator offset prevents division by zero. The early warning score aggregates incompletion signals with differential weighting:

where missing assignments receive double weight relative to late submissions, reflecting their stronger association with course failure. The engagement variability quantifies consistency in daily activity patterns:

where and denote standard deviation and mean, respectively, computed across all days with recorded activity. Higher values indicate erratic engagement patterns potentially signaling disengagement or external barriers to consistent participation.

All features were standardized using z-score normalization with statistics computed on the training set and applied consistently to both the training and test sets:

This normalization ensures that features with different scales contribute proportionally to model learning while preventing data leakage from test set statistics.

3.3. CR-NODE Architecture

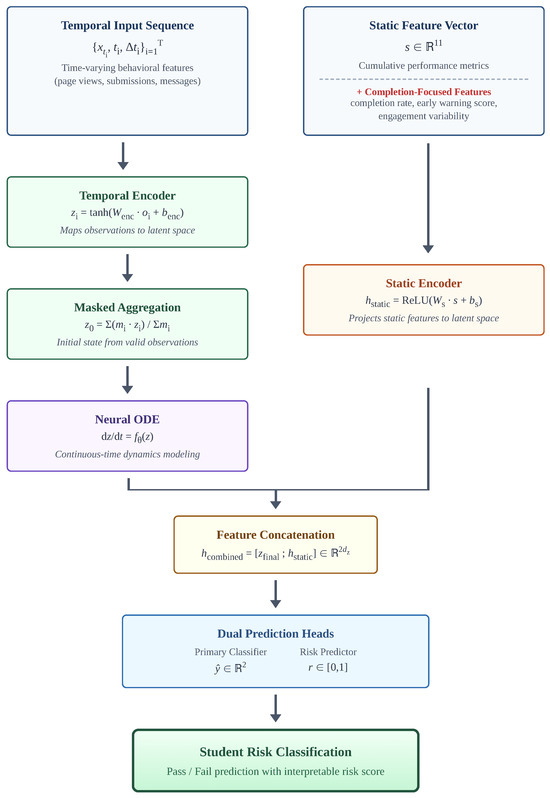

Completion-aware Risk Neural ODE (CR-NODE) integrates continuous-time temporal modeling via Neural Ordinary Differential Equations with completion-focused static features for student dropout prediction. The architecture comprises four interconnected components: a temporal observation encoder, an ODE-based latent dynamics module, a static feature encoder, and dual prediction heads for classification and risk estimation. Figure 1 provides a schematic overview of the complete architecture and Table 3 defines all mathematical notation used throughout the model description.

Figure 1.

CR-NODE architecture overview showing the dual-pathway design: temporal behavioral sequences are encoded and evolved through Neural ODE dynamics, while static features including completion-focused metrics are processed through a separate encoder. Both representations are concatenated and fed to dual prediction heads for classification and risk estimation.

Table 3.

Mathematical notation and variable definitions.

The temporal encoder transforms observed behavioral features into latent representations suitable for continuous-time dynamic modeling. At each observation time , we construct an augmented feature vector by concatenating temporal features with absolute time and inter-observation gaps:

where for and . Including temporal gaps explicitly enables the model to distinguish between regular consistent engagement patterns and sporadic irregular access patterns. The encoder maps these augmented observations to a latent space via

where and are learnable parameters. The hyperbolic tangent activation function bounds latent states within , improving numerical stability during subsequent ODE integration.

Given a variable-length sequence with binary mask indicating valid observations, we compute an aggregated initial state through masked averaging:

where prevents division by zero for edge cases. This pooling operation provides a summary representation that remains robust to variable sequence lengths while incorporating information from all valid observations.

The core of CR-NODE models continuous temporal evolution of student states through a Neural Ordinary Differential Equation:

where represents a neural network parameterized by learnable weights . This continuous-time formulation naturally accommodates irregular observation intervals without requiring imputation or resampling of missing time points [15]. The ODE function is instantiated as a two-layer feedforward network:

where , , and corresponding biases constitute learnable parameters. The expanded hidden dimension () provides sufficient representational capacity for modeling complex temporal dynamics. While the function signature includes time t following standard Neural ODE notation [14], our implementation treats dynamics as time-invariant by depending solely on the latent state .

To ensure numerical stability during integration, we apply state clamping before each ODE function evaluation:

This prevents extreme values that could cause overflow or underflow in subsequent computations. The ODE is solved numerically using the Euler method with fixed step size h:

We evaluate the ODE trajectory at three normalized time points and extract the final state:

During backpropagation, gradients are computed efficiently using the adjoint sensitivity method [14], which provides memory complexity independent of the number of ODE solver steps, enabling scalable training on long sequences.

Static features are processed through a separate encoding pathway:

where projects static features to match the dimensionality of temporal representations. The ReLU activation introduces nonlinearity while maintaining computational efficiency. The encoded temporal and static representations are then concatenated to form a unified feature vector:

This combined representation feeds into two parallel prediction heads. The primary classifier employs a three-layer fully connected architecture with dropout regularization:

with layer dimensions . The output logits represent un-normalized log-probabilities for failure and success, respectively. Dropout rates decrease in deeper layers following common practice to balance regularization with representational capacity.

The auxiliary risk predictor provides complementary fine-grained probability estimates through a similar three-layer architecture:

with layer dimensions . The sigmoid activation in the output layer constrains risk scores to the unit interval , providing interpretable probability estimates for student failure risk. The complete CR-NODE forward pass is formalized in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 CR-NODE forward pass algorithm showing temporal encoding, ODE evolution, static feature integration, and dual-head prediction. |

| Input: Temporal sequence , static features , mask |

| Output: Class logits , risk score r |

| // Encode temporal observations |

| for to T do |

| end for |

| // Aggregate initial state |

| // Solve ODE |

| // Encode static features |

| // Combine representations |

| // Classification |

| // Risk prediction |

| return |

3.4. Training Procedure

CR-NODE is optimized using a composite loss function that combines primary classification objectives with auxiliary risk prediction. To address the inherent class imbalance in dropout prediction, we employ Focal Loss [38], which down-weights well-classified examples and concentrates learning effort on hard misclassified cases:

where represents the predicted probability for the true class, denotes a class-specific weighting factor, and controls the focusing strength. Based on validation experiments, we set for the failure class, for the success class, and . This configuration increases emphasis on the minority failure class while the focusing parameter reduces the relative loss contribution from easy examples.

The auxiliary risk predictor is trained using binary cross-entropy loss with inverted labels to map high risk of failure:

where represents the true label (0 for failure, 1 for success), denotes the predicted risk probability, and balances the auxiliary objective against the primary classification loss. The risk target ensures that failing students receive high risk scores while successful students receive low scores, providing interpretable probability estimates suitable for prioritizing interventions.

The complete training objective combines both loss components:

We optimize this objective using AdamW [39], an adaptive learning rate method with decoupled weight decay regularization:

with momentum parameters and , learning rate , and weight decay . Gradient clipping with maximum L2 norm of 1.0 prevents exploding gradients that could destabilize training. The learning rate is reduced by a factor of 0.5 when the validation Macro F1 score fails to improve for 8 consecutive epochs, enabling fine-tuning in later training stages. Training proceeds for a maximum of 60 epochs with early stopping triggered if no improvement occurs within 20 epochs, preventing overfitting while ensuring convergence. Mini-batches of 64 sequences are processed with shuffling enabled during training.

3.5. Baseline Models

We compare CR-NODE against six baseline approaches (Logistic Regression, Random Forest, XGBoost, Gradient Boosting, LSTM, and Basic Neural ODE) representing diverse modeling paradigms to establish comprehensive performance benchmarks. The comparison includes both traditional machine learning methods operating on static aggregated features and modern temporal deep learning architectures.

For fair comparison, all static machine learning baselines utilize the complete feature set including both the eight baseline static features and the three completion-focused features defined in Table 2, ensuring that performance differences reflect algorithmic capabilities rather than feature availability. Logistic Regression serves as a linear baseline with L2 regularization, balanced class weights to address class imbalance, and LBFGS optimization for up to 1000 iterations. Random Forest implements an ensemble of 100 decision trees with maximum depth constrained to 10 and balanced class weights applied during tree construction. XGBoost employs gradient boosting with 100 estimators, maximum tree depth of 6, learning rate of 0.1, and automatically computed scale_pos_weight parameter equal to the ratio of negative to positive training examples. Gradient Boosting uses scikit-learn’s implementation with 100 estimators and maximum depth of 5, providing an alternative boosting baseline.

The temporal deep learning baseline models sequential behavioral patterns directly. LSTM employs a two-layer recurrent architecture with hidden dimension 64 and inter-layer dropout of 0.2. The complete set of 11 static features, including the 3 completion-focused features, is encoded through a separate fully connected layer and concatenated with the final LSTM hidden state before classification, ensuring identical feature access to CR-NODE. The LSTM model uses the same three-layer classifier architecture as CR-NODE (dimensions ) with dropout rates of 0.3 and 0.2, and is trained using identical loss functions (Focal Loss without auxiliary risk loss) and optimizer settings to isolate the impact of the temporal modeling approach.

The Basic Neural ODE baseline provides an ablation study isolating the contribution of completion-focused feature engineering. This model employs an architecture identical to CR-NODE in all respects except that it processes only the eight baseline static features, excluding the three completion-focused features (completion_rate, early_warning_score, engagement_variability). All hyperparameters, training procedures, and evaluation protocols remain consistent with CR-NODE. Performance differences between CR-NODE and Basic Neural ODE therefore directly quantify the value added by explicit completion-focused feature engineering.

Table 4 provides a comprehensive summary of hyperparameter configurations for all models evaluated in this study.

Table 4.

Hyperparameter configuration for all models.

3.6. Evaluation Methodology

We evaluate all models using metrics specifically appropriate for imbalanced binary classification in educational contexts where both false negatives (missing at-risk students) and false positives (unnecessarily flagging successful students) carry significant consequences.

For each class corresponding to failure and success, respectively, we compute precision, recall, and F1 score:

where , , and denote true positives, false positives, and false negatives for class c. Precision quantifies the fraction of predicted positives that are correct, recall measures the fraction of actual positives successfully identified, and F1 score provides their harmonic mean.

Our primary evaluation metric is Macro F1 score, which averages F1 across both classes:

Macro averaging treats both classes with equal importance regardless of their frequency in the dataset. This is particularly appropriate for educational risk prediction where correctly identifying the minority failure class is as critical as correctly identifying the majority success class [37]. Unlike accuracy, which can be misleadingly high when dominated by majority class performance, Macro F1 requires strong performance on both classes simultaneously.

To assess the statistical significance of performance differences between CR-NODE and baseline models, we apply McNemar’s test [22]. This non-parametric test evaluates whether two models make errors on different subsets of examples by analyzing their disagreement patterns. Given predictions from CR-NODE (model A) and a baseline (model B) on the same test set, we construct a contingency table:

where represents examples correctly classified by A but incorrectly by B, while represents the reverse. The test focuses on disagreement cases where models differ in their predictions.

The McNemar test statistic with continuity correction is computed as

Under the null hypothesis that both models have equal error rates, this statistic follows a chi-squared distribution with 1 degree of freedom. We reject the null hypothesis at significance level when the computed p-value satisfies , concluding that one model significantly outperforms the other. This paired test is more powerful than comparing accuracy scores independently because it accounts for the fact that models are evaluated on identical test examples, reducing variance from test set sampling.

3.7. Implementation Details

All models were implemented in Python 3.9 using PyTorch 1.13 for neural network architectures and scikit-learn 1.2 for traditional machine learning methods. Neural ODE integration was performed using the torchdiffeq library [14] with automatic differentiation for gradient computation. XGBoost version 1.7 was used for gradient boosting baselines. All experiments were conducted on CPU hardware to ensure broad reproducibility without specialized GPU requirements. Random seed 42 was set globally across all random number generators to ensure deterministic reproducibility of results.

Training CR-NODE on the complete training set of 68,444 sequences required approximately 3.8 min on a standard multi-core CPU, demonstrating computational efficiency suitable for practical deployment. The final CR-NODE model contains 39,395 trainable parameters distributed across the temporal encoder, ODE function, static encoder, classifier, and risk predictor components.

4. Results

4.1. Overall Performance Comparison

We evaluated CR-NODE against six baseline approaches (Logistic Regression, Random Forest, XGBoost, Gradient Boosting, LSTM, and Basic Neural ODE) on the held-out test set comprising 17,111 student sequences. Table 5 presents comprehensive performance metrics for all models. CR-NODE achieved the highest Macro F1 score of 0.8747, demonstrating substantial improvements over all baselines.

Table 5.

Performance comparison across all models.

CR-NODE outperformed all baselines with statistically significant margins. Compared to LSTM [10], CR-NODE achieved Macro F1 improvement of 6.24 percentage points (0.8747 vs. 0.8123), with particularly strong gains in failure class prediction where F1 increased by 9.70 percentage points (0.8186 vs. 0.7216), demonstrating the advantage of continuous-time modeling via Neural ODEs [14,15] over discrete recurrent architectures. Among static machine learning methods, XGBoost achieved the strongest performance with Macro F1 of 0.8300. CR-NODE exceeded XGBoost by 4.47 percentage points, with improvement concentrated in failure class detection (0.8186 vs. 0.7482). Logistic Regression achieved Macro F1 of 0.7262, confirming that nonlinear modeling is essential. The Basic Neural ODE baseline achieved Macro F1 of 0.8682. The 0.65 percentage point gap directly quantifies the contribution of completion-focused feature engineering.

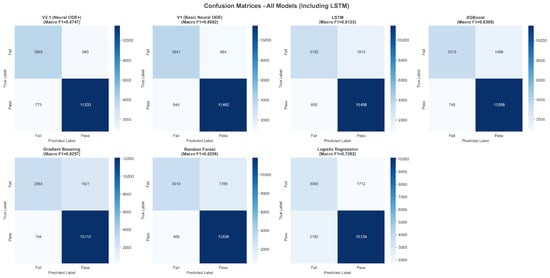

Figure 2 presents confusion matrices for all seven models. CR-NODE correctly identified 3865 of 4805 failing students and 11,533 of 12,306 passing students, yielding 940 false positives and 773 false negatives. Compared to LSTM, CR-NODE reduced false negatives by 10.3% (850 to 773) while maintaining competitive false-positive rates, critical for practical deployment [3,23].

Figure 2.

Confusion matrices for all seven models showing prediction distributions across failure and success classes. CR-NODE achieves the best balance between true-positive and true-negative rates.

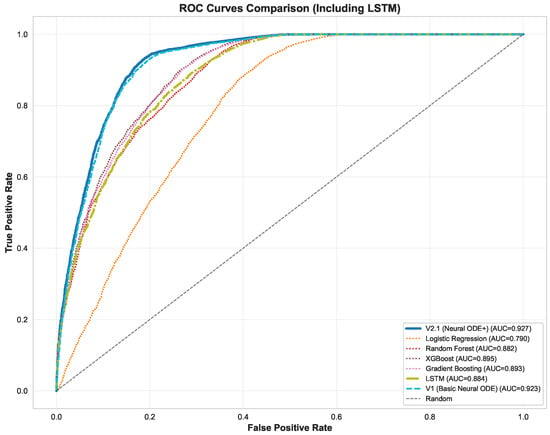

Figure 3 presents Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves with corresponding AUC values. CR-NODE achieved an Area Under the Curve (AUC) of 0.927, closely followed by Basic Neural ODE at 0.923. Both substantially exceeded LSTM (0.884), XGBoost (0.895), and traditional baselines. For imbalanced educational datasets, precision–recall-based metrics provide more informative evaluation than ROC-based metrics [37].

4.2. Statistical Significance Analysis

To rigorously assess whether CR-NODE’s performance improvements represent statistically significant differences, we applied McNemar’s test [22] comparing CR-NODE predictions against each baseline model. McNemar’s test evaluates disagreement patterns between paired classifiers, providing more statistical power by accounting for evaluation on the same examples [40].

Figure 3.

ROC curves comparing all models. Neural ODE variants (CR-NODE and Basic Neural ODE) achieve superior discrimination ability with AUC exceeding 0.92, substantially outperforming both temporal (LSTM) and static machine learning baselines.

Table 6 presents McNemar’s test results. CR-NODE demonstrated statistically significant superiority over all six baselines with p-values below 0.0001. Against LSTM, CR-NODE correctly classified 1514 students that LSTM misclassified, while making errors on only 764 students that LSTM classified correctly, yielding a net improvement of 750 students and a chi-squared of 246.27 (p < 0.0001), confirming that continuous-time Neural ODE modeling provides genuine advantages over discrete-time recurrent architectures.

Table 6.

McNemar’s test results: CR-NODE vs. all baselines.

Against static baselines, CR-NODE correctly classified 2983 students that Logistic Regression misclassified while erring on only 802, yielding chi-squared of 1255.59. Against XGBoost, CR-NODE achieved net improvement of 521 students with chi-squared of 138.31, demonstrating that temporal modeling captures predictive information absent from aggregated static features. Against Basic Neural ODE, CR-NODE achieved a net improvement of 95 students and chi-squared of 22.48 (p < 0.0001), confirming that explicit completion metrics provide measurable performance gains.

4.3. Model Training and Convergence

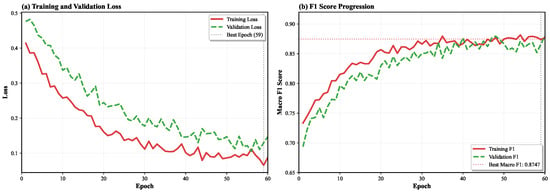

Figure 4 illustrates CR-NODE’s training dynamics across 60 epochs. Training loss decreased smoothly from 0.42 to 0.07, while validation loss declined from 0.48 to 0.12, exhibiting no overfitting despite 39,395 trainable parameters. Training Macro F1 improved from 0.73 to 0.87, tracking validation F1 which increased from 0.72 to 0.8747. The best model was selected at epoch 59.

Figure 4.

Training dynamics for CR-NODE showing (a) training and validation loss progression, and (b) training and validation Macro F1 score evolution. The vertical dashed line indicates the best epoch (59) selected via early stopping. Smooth convergence with consistent train–validation gaps indicates well-regularized learning without overfitting.

Training required approximately 3.8 min on standard CPU hardware to process 68,444 sequences, demonstrating computational efficiency suitable for practical deployment without specialized hardware. The adjoint sensitivity method [14] enables memory-efficient gradient computation despite continuous-time formulation. CR-NODE achieved strong performance without extensive hyperparameter tuning, contrasting with some deep learning approaches requiring extensive computational resources [11,27].

4.4. Ablation Study: Feature Contribution Analysis

To systematically evaluate completion-focused feature contributions, we conducted an ablation study training CR-NODE variants with different configurations. Table 7 presents results across six configurations.

Table 7.

Ablation study: contribution of completion-focused features.

Removing individual features revealed that early_warning_score provides the largest contribution, reducing Macro F1 by 0.96 percentage points (0.8747 to 0.8651) and Fail F1 by 1.52 percentage points. Completion_rate contributed 1.24 percentage points to Macro F1 and 1.99 percentage points to Fail F1. Engagement_variability provided 0.58 percentage points to Macro F1 and 0.88 percentage points to Fail F1. These demonstrate that all three features encode complementary predictive signals. The configuration using only completion-focused features achieved Macro F1 of 0.7234, substantially below all other configurations, confirming that completion metrics alone cannot replace comprehensive behavioral features but provide complementary information. The gap between this configuration and Basic Neural ODE (0.7234 vs. 0.8682) demonstrates that baseline features capture fundamental patterns, while completion-focused features provide incremental but significant improvements. These results validate our feature engineering approach grounded in root cause analysis, aligning with prior research emphasizing assignment completion and submission timeliness as leading indicators of academic risk [5,16,24].

4.5. Temporal Pattern Analysis

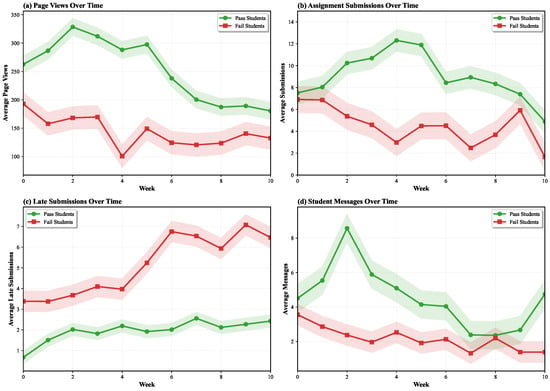

Figure 5 illustrates temporal behavioral patterns distinguishing passing and failing students across 10 weeks, revealing systematic differences enabling Neural ODE temporal modeling to achieve superior performance.

Figure 5.

Temporal behavioral patterns comparing passing students (green) and failing students (red) across four key dimensions: (a) LMS page views showing sustained engagement differences, (b) assignment submissions revealing completion gaps, (c) late submissions indicating time management challenges, and (d) communication patterns reflecting help-seeking behavior. Shaded regions represent 95% confidence intervals.

LMS engagement patterns exhibit persistent divergence. Passing students maintain average page views between 180 and 330 per week with peak activity during weeks 2–3, while failing students exhibit consistently lower engagement averaging 100–200 page views with declining trajectory after week 4, supporting that continuous monitoring provides early signals of academic risk [4,41]. Assignment submission patterns reveal the most striking differences. Passing students maintain steady submission rates of 8–12 assignments per week, with a characteristic peak around week 4. Failing students show dramatically lower volumes averaging 3–7 per week with erratic patterns. The submission gap widens progressively, validating our completion-focused feature engineering and explaining why Neural ODE temporal modeling outperforms static aggregation methods.

Late submission behavior provides complementary signals. Passing students maintain stable low rates around 2–3 per week. Failing students exhibit escalating patterns starting around week 5–6, reaching 6–7 per week by week 10, enabling Neural ODE dynamics to model progressive deterioration in time management. Communication patterns reveal differential help-seeking behaviors. Passing students maintain moderate volumes of 4–8 per week, with a notable spike around week 2. Failing students show consistently lower communication, averaging 1–3 messages per week, potentially indicating disengagement or social isolation.

These patterns collectively demonstrate why continuous-time Neural ODE modeling achieves superior performance. The Neural ODE formulation [14,15] naturally accommodates irregular observation intervals while capturing smooth temporal trajectories characterizing behavioral evolution. In contrast, LSTM models require fixed time-step discretization that may miss important dynamics [32], while static methods aggregate away temporal patterns entirely.

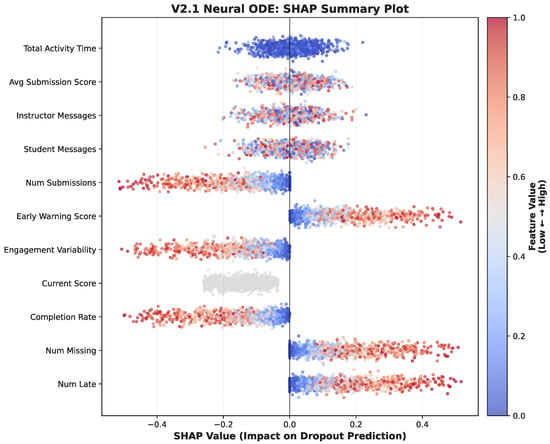

4.6. Feature Importance and Interpretability

To enhance model transparency, we analyzed feature importance using SHAP 0.42.1 (SHapley Additive exPlanations) [20]. Figure 6 presents a SHAP summary plot showing each feature’s impact on CR-NODE’s dropout predictions.

Figure 6.

SHAP summary plot for CR-NODE showing feature importance and directionality. Features are ranked by mean absolute SHAP value (importance). Each point represents one student, with color indicating feature value (red = high, blue = low) and position on the x-axis indicating impact on dropout prediction (positive = increased dropout risk; negative = decreased risk). The three completion-focused features (highlighted) appear among the most influential predictors.

Completion-focused features appear prominently among the most influential predictors. Early_warning_score ranks as the second-most important feature, with high values strongly increasing dropout prediction scores, validating that missing and late assignment counts serve as powerful early indicators. Num_missing emerges as the single most influential feature, aligning with research identifying assignment completion as a fundamental predictor of academic success [16,24]. Num_late shows complex patterns where both very low and very high values increase risk, potentially reflecting complete disengagement versus chronic time management problems.

Among baseline features, current_score shows strong intuitive patterns where low values increase dropout risk and high values decrease risk. However, current_score exhibits more dispersed impact compared to completion-focused features, suggesting it alone provides incomplete risk assessment, supporting our approach of combining performance metrics with behavioral completion patterns. Engagement_variability demonstrates that both very low and very high variability increase dropout risk, with consistent moderate engagement associated with success. This U-shaped relationship validates that erratic engagement patterns signal either disengagement or ineffective study strategies. Communication features show weaker scattered importance, suggesting messaging behavior provides less reliable risk signals.

SHAP analysis reveals CR-NODE’s superior performance stems from leveraging complementary information from multiple feature types: temporal behavioral patterns captured by Neural ODE dynamics, cumulative performance metrics from baseline features, and explicit completion signals from engineered features, aligning with recommendations for actionable learning analytics [2,42]. The interpretability addresses critical requirements for ethical deployment in educational settings [17,18]. By exposing which features drive individual predictions, SHAP enables educators to understand not just which students are at risk, but why, facilitating targeted interventions addressing specific underlying issues.

4.7. Error Analysis and Misclassification Patterns

To provide deeper insight into model behavior beyond aggregate performance metrics, we conducted systematic analysis of CR-NODE’s prediction errors, examining the characteristics of misclassified students and identifying patterns that explain model limitations.

4.7.1. Characterization of Misclassified Students

CR-NODE produced 940 false positives (successful students incorrectly predicted to fail) and 773 false negatives (failing students incorrectly predicted to pass) from the 17,111 test set students. Table 8 compares the behavioral characteristics of correctly classified versus misclassified students across key features.

Table 8.

Behavioral characteristics by classification category.

False negatives (missed at-risk students) exhibit behavioral profiles remarkably similar to passing students: high current scores (86.81 vs. 90.28 for true negatives), moderate engagement levels (839 vs. 1035 page views), and comparable completion rates (0.06 vs. 0.06). These students maintain performance indicators suggesting success throughout most of the course but ultimately fail, likely due to poor performance on final assessments or late-semester disengagement not fully captured within the 10-week observation window. The SHAP analysis (Figure 6) provides insight into this pattern: current score exhibits relatively concentrated SHAP values near zero compared to completion-focused features, indicating the model appropriately prioritizes behavioral completion patterns over instantaneous grade standing—yet this design choice means students with strong current scores but latent risk factors may be missed.

False positives (incorrectly flagged successful students) display high current scores (88.69) and lower engagement variability (0.95 vs. 1.02 for true negatives), suggesting these students exhibited early warning indicators but subsequently recovered. The model correctly identifies initial risk signals but cannot fully predict successful self-correction or the effects of intervention.

4.7.2. Confidence–Accuracy Relationship

We examined the relationship between prediction confidence (maximum softmax probability) and classification accuracy to assess model calibration. Table 9 presents accuracy stratified by confidence level.

Table 9.

Prediction accuracy by confidence level.

CR-NODE exhibits well-calibrated confidence estimates: predictions with confidence ≥0.85 achieve 99.8% accuracy, while intermediate confidence predictions (0.50–0.60) yield only 70.4% accuracy. This calibration has practical implications for deployment—students receiving intermediate-confidence predictions warrant closer human review and additional monitoring, while high-confidence predictions can reliably inform automated engagement or support workflows.

4.7.3. Performance Across Engagement Subgroups

To assess whether model performance varies systematically across student populations, we stratified the test set into engagement terciles based on total page views. Table 10 presents performance metrics for each subgroup.

Table 10.

CR-NODE performance across engagement subgroups.

Performance remains robust across engagement levels, with Macro F1 ranging from 0.861 to 0.878. However, fail recall decreases in the high-engagement subgroup (0.76 vs. 0.81–0.83 for lower engagement groups), reflecting increased difficulty in identifying at-risk students whose high engagement levels mask underlying academic struggles. High-engagement students who ultimately fail represent only 20.9% of their subgroup but are disproportionately likely to be missed by the model. This finding has practical implications: high-engagement students flagged with intermediate confidence may benefit from assessment-focused review rather than engagement-based interventions.

4.7.4. Sources of Prediction Error

Synthesizing across error characterization, confidence analysis, and SHAP-based feature importance (Section 4.6), we identify three primary sources of CR-NODE prediction errors:

- Engagement–performance dissociation: Students with high engagement but poor assessment outcomes present conflicting behavioral signals. As shown in Table 8, false negatives maintain page views (839) approaching those of passing students (1035), yet their ultimate failure suggests engagement quantity does not guarantee learning quality. The SHAP analysis confirms the model prioritizes completion-focused features over raw engagement metrics, which successfully identifies most at-risk students but misses those whose activity levels mask academic difficulties.

- Late behavioral transitions: False negatives exhibit current scores (86.81) nearly matching passing students (90.28), indicating that these students maintain successful performance trajectories through most of the observation period before experiencing late-semester decline. The 10-week feature extraction window, while aligned with early intervention goals [16], may not capture critical end-of-term deterioration that determines final outcomes.

- Recovery trajectories: False positives demonstrate early risk indicators that appropriately trigger high-risk predictions, but these students subsequently improve through self-correction or successful intervention. The model cannot distinguish between students who will persist in at-risk patterns versus those who will recover, representing an inherent limitation of early prediction systems that prioritize timely identification over waiting for behavioral stabilization.

These findings suggest several directions for model refinement: incorporating assessment-specific performance trajectories to complement behavioral features, developing adaptive prediction windows that extend monitoring for intermediate-confidence cases, and exploring separate modeling pathways for high-engagement students whose risk profiles differ from typical at-risk patterns.

4.8. Generalization to OULAD Dataset

To assess CR-NODE’s generalizability, we evaluated the model on the Open University Learning Analytics Dataset (OULAD) [43], a widely used benchmark containing 32,593 student records. We extracted 17,928 valid temporal sequences (11,641 passing, 6287 failing) following identical preprocessing protocols. The model was trained with the same hyperparameters, using only the eight baseline static features available in OULAD, without completion-focused engineered features.

Table 11 presents CR-NODE’s performance compared to recent state-of-the-art results from Torkhani and Rezgui [44].

Table 11.

Performance comparison on OULAD dataset with recent studies.

CR-NODE achieved 84.44% accuracy on the OULAD test set (3,586 students), outperforming the best model from Torkhani and Rezgui [44]—LSTM at 83.41%—by 1.03 percentage points. Our model demonstrated consistent superiority: 84.30% precision versus 82.20% for LSTM (2.10 point improvement), and 84.40% recall versus 81.88% for LSTM (2.52 point improvement). The confusion matrix revealed 920 correctly identified failing students, 2108 correctly identified passing students, with 338 false negatives and 220 false positives. Class-specific performance showed Fail F1 of 0.767 and Pass F1 of 0.883, yielding Macro F1 of 0.8252.

These results provide strong evidence for CR-NODE’s cross-dataset generalizability. Despite using a different institutional context (UK Open University versus US educational-based traditional university), different LMS platform (Open University VLE versus Canvas), and lacking engineered completion-focused features, CR-NODE maintained competitive performance and exceeded current state-of-the-art approaches. The model’s ability to achieve superior results using only baseline features demonstrates that the Neural ODE temporal modeling framework contributes substantially to predictive performance, independent of specialized feature engineering. Training required only 29.8 s on standard CPU hardware for 14,342 sequences, confirming computational efficiency for practical deployment across diverse educational settings.

5. Discussion

5.1. Performance Achievements and Model Contributions

CR-NODE achieved Macro F1 of 0.8747 on 17,111 test students, significantly outperforming six baselines (p < 0.0001), demonstrating that continuous-time temporal modeling with explicit completion metrics achieves substantial improvements over traditional machine learning and contemporary deep learning architectures. Performance places CR-NODE among the highest-achieving systems in the recent literature. Basnet et al. [11] reported F1 around 0.88 for MOOC dropout prediction on OULAD, Hassan et al. [12] achieved 0.86 recall using LSTM, and Aouarib et al. [9] achieved 0.92 accuracy using genetic algorithm-optimized XGBoost, though accuracy can be misleading for imbalanced datasets, where our Macro F1 provides more balanced evaluation [37]. Our results are competitive while offering distinct advantages: explicit interpretability through SHAP analysis, computational efficiency requiring only 3.8 min training, and direct applicability to traditional semester-based courses. The 6.24 percentage point improvement over LSTM (0.8747 vs. 0.8123) represents substantial advancement, particularly notable because both models utilize identical feature sets and training procedures, isolating the Neural ODE continuous-time formulation’s architectural contribution versus discrete recurrent processing. Prior work found more modest differences between architectures [13,27], suggesting that irregular observation patterns characteristic of LMS data provide especially favorable conditions for Neural ODE approaches naturally accommodating variable time intervals [15,32].

The synergy between temporal modeling and completion-focused features further explains CR-NODE’s advantage: temporal dynamics reveal when during the course behavioral changes occur, while completion metrics quantify what patterns accumulate, together capturing signals that neither component achieves independently.

5.2. Temporal Modeling Advantages over Static and Discrete Methods

Temporal pattern analysis revealed systematic behavioral trajectories distinguishing passing and failing students that static aggregation methods obscure. Progressive divergence in assignment submissions, escalating late submissions after week 5, and temporal stability of engagement differences throughout 10 weeks collectively demonstrate why continuous-time modeling achieves superior performance. These findings align with prior research emphasizing the importance of temporal dynamics [45,46], while extending work by demonstrating that continuous-time Neural ODE formulations capture patterns more effectively than discrete-time recurrent architectures. The 4.47 percentage point improvement over XGBoost (0.8747 vs. 0.8300) quantifies the value of temporal modeling versus static aggregation, even when static methods access identical underlying behavioral data. This gap suggests temporal ordering and evolution encode predictive information that summary statistics cannot capture. Prior studies similarly found that temporal sequence models outperform static methods [7,26], though typically employing discrete-time RNNs rather than continuous ODE formulations.

The Neural ODE framework offers technical advantages for educational data explaining superior performance. First, LMS data exhibits highly irregular observation intervals. Traditional RNN architectures require either fixed time-step discretization potentially missing important dynamics or complex attention mechanisms handling irregular sampling [47]. Neural ODEs naturally accommodate arbitrary observation patterns by modeling continuous underlying processes [14], avoiding discretization information loss. Second, the adjoint sensitivity method enables memory-efficient training with long temporal sequences, addressing persistent challenges in applying deep learning to educational datasets with extensive longitudinal records [31]. Third, continuous formulation provides natural regularization encouraging smooth temporal trajectories, potentially improving generalization by avoiding overfitting to noisy observation-to-observation fluctuations.

5.3. Completion-Focused Feature Engineering and Domain Knowledge Integration

The ablation study demonstrated that completion-focused features contribute 0.65 percentage points to Macro F1, with statistical significance confirmed versus Basic Neural ODE baseline (p < 0.0001). While representing a smaller effect than architectural contribution, it constitutes meaningful and reliable improvement achievable through feature engineering informed by domain expertise and root cause analysis, validating that data-driven machine learning benefits from substantive domain knowledge integration [1,48]. The three completion-focused features capture complementary assignment engagement aspects. Completion_rate quantifies the expected proportion of coursework submitted, providing a normalized metric robust to varying course structures. Early_warning_score aggregates missing and late assignment counts with differential weighting, reflecting research showing that missing work predicts failure more strongly than late submission [16,24]. Engagement_variability measures consistency through coefficient of variation, capturing that both sporadic and obsessive engagement patterns indicate difficulty, while moderate, consistent engagement characterizes successful students [4].

SHAP analysis revealed that engineered features rank among the most influential predictors, with early_warning_score and num_missing in the top three positions. This validates feature engineering while highlighting that explicit quantification of completion patterns enhances performance beyond temporal dynamics alone. Strong SHAP importance aligns with extensive research identifying assignment completion as fundamental academic success determinant [5,41], suggesting that explicit feature engineering successfully operationalizes insights from the literature into predictive features that deep learning models effectively leverage. The configuration using only completion-focused features achieved an Macro F1 of 0.7234, substantially below configurations including baseline features but above naive baselines, indicating that completion metrics alone capture meaningful signals but cannot replace comprehensive behavioral and performance indicators. This suggests a productive integration strategy where domain-specific feature engineering complements rather than replaces data-driven temporal modeling.

While prior early warning systems incorporated missing assignment counts as predictive indicators [16,23], these approaches treated completion variables as static features within aggregate models rather than engineering features to capture completion dynamics integrated with temporal behavioral modeling.

5.4. Interpretability, Trust, and Actionable Insights

SHAP-based interpretability analysis addresses critical requirements for ethical and effective deployment. Educational stakeholders require not merely accurate predictions but transparent explanations supporting evidence-based interventions [17,18]. Analysis revealed that CR-NODE’s predictions primarily reflect completion patterns, engagement consistency, and cumulative performance metrics, providing interpretable risk profiles educators can act upon, contrasting with black-box approaches offering limited insight [19]. Feature importance rankings provide actionable intervention design guidance. The prominence of early_warning_score and num_missing suggests that monitoring systems should prioritize tracking assignment completion with automated alerts for missing work. The importance of engagement_variability indicates that flagging both sporadic and obsessive activity patterns may identify students requiring support before grade indicators reveal problems. Communication features’ lower importance suggests that messaging behavior provides less reliable risk signals. These insights enable targeted resource allocation focusing intervention efforts on high-impact behavioral indicators [3,23]. The auxiliary risk head complements binary classification by providing continuous risk probabilities between 0 and 1, serving dual purposes. The first is as a multi-task learning signal that regularizes training through calibrated probability estimation, and the second is as a practical output enabling instructors to rank students by risk severity rather than relying on binary classifications alone, particularly valuable when intervention resources are limited.

Recent work increasingly emphasizes the necessity of explainable AI in educational applications, with Liu et al. [21] demonstrating ensemble learning with SHAP analysis and Chang et al. [49] developing personalized intervention systems based on interpretable predictions. Our approach contributes by showing that Neural ODE temporal models, despite mathematical sophistication, can be made interpretable through post hoc analysis methods, addressing the accuracy-transparency tension challenging educational AI deployment [33,48]. Interpretability supports continuous model improvement through expert feedback. Educators reviewing SHAP explanations can identify cases where predictions contradict professional judgment, enabling feature or training procedure refinement. This human-in-the-loop approach aligns with recommendations for responsible learning analytics positioning automated systems as decision support tools augmenting rather than replacing human expertise [2,42].

5.5. Practical Implications and Limitations

CR-NODE’s computational efficiency and interpretability position it as practical solution for institutional deployment. The 3.8 min training time on standard CPU hardware demonstrates feasibility for routine model updates, avoiding specialized infrastructure requirements limiting some deep learning approaches [11,12]. The model’s 39,395 parameters represent modest scale enabling deployment on conventional institutional computing resources without GPU acceleration. Strong performance within the first 10 weeks corresponds to a critical intervention window where support meaningfully impacts outcomes, aligning with research identifying weeks 4–6 as optimal for early warning activation [16,45]. CR-NODE achieves 940 false positives and 773 false negatives from 17,111 students (7.6% FPR, 16.1% FNR), reflecting prioritization of sensitivity while maintaining reasonable precision to avoid alert fatigue. Alternative threshold configurations could shift this trade-off. Recent work emphasizes explicitly examining trade-offs across student subpopulations to ensure equitable performance [34,35]. SHAP-based explanations facilitate integration with advising workflows by providing specific behavioral indicators underlying predictions, enabling targeted outreach. For instance, students flagged due to high early_warning_score and engagement_variability might benefit from time management coaching, whereas students with strong engagement but declining submission_scores might require content tutoring. This differentiated approach offers more effective resource utilization versus generic interventions [23,49]. To illustrate concretely, consider a student predicted as at risk whose SHAP analysis reveals high contributions from num_missing and low completion_rate, but neutral contributions from engagement metrics. This profile indicates the student is active in the LMS but failing to submit work, suggesting an intervention focused on assignment completion support rather than engagement encouragement.

The OULAD cross-validation addresses questions regarding CR-NODE’s applicability across contexts. The model achieved a Macro F1 of 0.8252 using only eight baseline features, demonstrating that completion-focused features enhance performance when available but are not essential. The Neural ODE temporal modeling framework provides the primary predictive advantage. For institutions lacking fine-grained assignment data, CR-NODE can be deployed with baseline behavioral features alone. Cross-platform generalization is supported by successful validation across our data and OULAD’s, representing substantially different institutional contexts and student populations. The 5.0 percentage point performance difference reflects both feature availability and inherent cross-institutional variation. Generalization to other contexts—such as community colleges, quarter-system courses, or alternative LMS platforms—requires local validation, and systematic parameter sensitivity analysis remains a direction for future research.

Several limitations warrant consideration. First, the data originates from a single large public university, potentially limiting generalizability. Prior research documented substantial performance variation across institutional contexts [5,6]. Multi-institutional validation would strengthen confidence in generalization. Second, the dataset reflects students completing courses through to the end of the semester, excluding early withdrawals lacking comprehensive behavioral records. This selection effect may introduce optimistic bias [25,50]. Third, validation employed standard train–test holdout rather than temporal validation mimicking deployment conditions [51]. Fourth, the analysis does not address algorithmic fairness across demographic subgroups. LMS interaction patterns may vary across demographic groups due to differences in technology access, work obligations, or educational backgrounds, meaning models trained on behavioral data could inadvertently encode such disparities. Recent research highlighted that models achieving strong aggregate performance may exhibit disparate accuracy across racial, socioeconomic, or gender categories, potentially amplifying educational inequities [34,35]. Fifth, privacy considerations require careful attention. Operational deployment necessitates robust data governance frameworks addressing student consent, data security, and transparency about surveillance practices [17,36,52]. Finally, this study focuses exclusively on predictive accuracy without evaluating whether deployment actually improves student outcomes. Prediction constitutes only the first step in the intervention pipeline. Demonstrating that predictive systems improve retention and outcomes requires controlled evaluation in operational settings [2,3,23].

6. Conclusions and Future Work

This study introduced CR-NODE, combining Neural Ordinary Differential Equations with completion-focused feature engineering for early student dropout prediction. Evaluated on over 100,000 Canvas LMS enrollments, CR-NODE achieved a Macro F1 of 0.8747, significantly outperforming LSTM, XGBoost, and traditional methods (McNemar’s test p < 0.0001). Three primary contributions emerge: First, continuous-time Neural ODE modeling provides a 6.24 percentage point improvement over LSTM and 4.47 points over XGBoost, quantifying advantages for irregular observation patterns. Second, completion-focused features contribute 0.65 percentage points with high statistical significance, integrating data-driven learning with educational domain knowledge. Third, SHAP-based interpretability reveals completion patterns, engagement consistency, and performance trajectories as prediction drivers, supporting transparent early warning systems. Temporal analysis revealed behavioral divergence within 4-6 weeks, identifying the critical intervention window. Training in 3.8 min on a standard CPU with 39,395 parameters demonstrates practical deployment feasibility [49,53,54].

The convergence of continuous-time modeling, completion-focused engineering, and interpretability establishes foundations for next-generation early warning systems. Maintaining focus on actionable, interpretable, equitable, and privacy-respecting predictions ensures learning analytics serve genuine educational objectives [42]. Future research can advance methodological innovations and practical systems supporting student success at scale.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B. and F.-Z.B.; methodology, A.B.; software, A.B.; validation, A.B., F.-Z.B. and H.H.; formal analysis, A.B.; investigation, A.B.; resources, H.H.; data curation, A.B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.B.; writing—review and editing, F.-Z.B. and H.H.; visualization, A.B.; supervision, H.H.; project administration, H.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study were obtained from internal student records of a Moroccan higher education institution and cannot be shared publicly due to privacy and ethical restrictions. Derived datasets and aggregated results are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the institutional data team for secure data access.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| CPU | Central Processing Unit |

| CR-NODE | Completion-aware Risk Neural Ordinary Differential Equations |

| DKT | Deep Knowledge Tracing |

| EDM | Educational Data Mining |

| EWS | Early Warning System |

| F1 | F1 Score |

| FNR | False-Negative Rate |

| FPR | False-Positive Rate |

| GPU | Graphics Processing Unit |

| HMM | Hidden Markov Model |

| LA | Learning Analytics |

| LIME | Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations |

| LMS | Learning Management System |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| MOOC | Massive Open Online Course |

| MLP | Multilayer Perceptron |

| ODE | Ordinary Differential Equation |

| OULAD | Open University Learning Analytics Dataset |

| ReLU | Rectified Linear Unit |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| SHAP | SHapley Additive exPlanations |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| UTC | Coordinated Universal Time |

| XAI | Explainable Artificial Intelligence |

| XGBoost | Extreme Gradient Boosting |

References

- Romero, C.; Ventura, S. Educational data mining and learning analytics: An updated survey. WIREs Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2020, 10, e1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, R. Learning analytics: Drivers, developments and challenges. Int. J. Technol. Enhanc. Learn. 2012, 4, 304–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macfadyen, L.P.; Dawson, S. Mining LMS data to develop an “early warning system” for educators: A proof of concept. Comput. Educ. 2010, 54, 588–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, A.; Zdrahal, Z.; Nikolov, A.; Pantucek, M. Improving retention: Predicting at-risk students by analysing clicking behaviour in a virtual learning environment. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Learning Analytics and Knowledge (LAK ’13), Leuven, Belgium, 8–12 April 2013; pp. 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conijn, R.; Snijders, C.; Kleingeld, A.; Matzat, U. Predicting Student Performance from LMS Data: A Comparison of 17 Blended Courses Using Moodle LMS. IEEE Trans. Learn. Technol. 2017, 10, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsiantis, S.; Pierrakeas, C.; Pintelas, P. Predicting students’ performance in distance learning using machine learning techniques. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2004, 18, 411–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, E.B.; Fonseca, B.; Santana, M.A.; de Araújo, F.F.; Rego, J. Evaluating the effectiveness of educational data mining techniques for early prediction of students’ academic failure in introductory programming courses. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 73, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almalawi, A.; Soh, B.; Li, A.; Samra, H. Predictive Models for Educational Purposes: A Systematic Review. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2024, 8, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aouarib, H.E.; Henouda, S.E.; Laallam, F.Z. Predicting Student Dropout in MOOCs Using Genetic Algorithms and XGBoost. J. Inf. Syst. Eng. Manag. 2025, 10, 1081–1092. [Google Scholar]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long Short-Term Memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basnet, R.B.; Johnson, C.; Doleck, T. Dropout prediction in MOOCs using deep learning and machine learning. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 11499–11513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.U.; Waheed, H.; Aljohani, N.R.; Ali, M.; Ventura, S.; Herrera, F. Virtual learning environment to predict withdrawal by leveraging deep learning. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2019, 34, 1935–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, M.; Yeung, D.Y. Temporal Models for Predicting Student Dropout in Massive Open Online Courses. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining Workshop (ICDMW), Atlantic City, NJ, USA, 14–17 November 2015; pp. 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.T.Q.; Rubanova, Y.; Bettencourt, J.; Duvenaud, D.K. Neural Ordinary Differential Equations. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Montréal, QC, Canada, 2–8 December 2018; Volume 31. [Google Scholar]

- Rubanova, Y.; Chen, R.T.Q.; Duvenaud, D.K. Latent Ordinary Differential Equations for Irregularly-Sampled Time Series. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019; Volume 32. [Google Scholar]

- Márquez-Vera, C.; Cano, A.; Romero, C.; Noaman, A.Y.M.; Fardoun, H.M.; Ventura, S. Early dropout prediction using data mining: A case study with high school students. Expert Syst. 2016, 33, 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, S.; Prinsloo, P. Learning Analytics: Ethical Issues and Dilemmas. Am. Behav. Sci. 2013, 57, 1510–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, W.; Porayska-Pomsta, K.; Holstein, K.; Sutherland, E.; Baker, T.; Buckingham Shum, S.; Santos, O.C.; Rodrigo, M.T.; Cukurova, M.; Bittencourt, I.I.; et al. Ethics of AI in Education: Towards a Community-Wide Framework. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2022, 32, 504–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adadi, A.; Berrada, M. Peeking Inside the Black-Box: A Survey on Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI). IEEE Access 2018, 6, 52138–52160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Zhou, X.; Liu, Y. Student Dropout Prediction Using Ensemble Learning with SHAP-Based Explainable AI Analysis. J. Soc. Syst. Policy Anal. 2025, 2, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNemar, Q. Note on the sampling error of the difference between correlated proportions or percentages. Psychometrika 1947, 12, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, K.E.; Pistilli, M.D. Course signals at Purdue: Using learning analytics to increase student success. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Learning Analytics and Knowledge (LAK ’12), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 29 April–2 May 2012; pp. 267–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.W. Identifying significant indicators using LMS data to predict course achievement in online learning. Internet High. Educ. 2016, 29, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lykourentzou, I.; Giannoukos, I.; Nikolopoulos, V.; Mpardis, G.; Loumos, V. Dropout prediction in e-learning courses through the combination of machine learning techniques. Comput. Educ. 2009, 53, 950–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehill, J.; Mohan, K.; Seaton, D.; Rosen, Y.; Tingley, D. Delving Deeper into MOOC Student Dropout Prediction. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1702.06404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Yu, H.; Miao, C. Deep Model for Dropout Prediction in MOOCs. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Crowd Science and Engineering (ICCSE’17), Beijing, China, 6–9 July 2017; pp. 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piech, C.; Bassen, J.; Huang, J.; Ganguli, S.; Sahami, M.; Guibas, L.J.; Sohl-Dickstein, J. Deep Knowledge Tracing. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Montréal, QC, Canada, 7–12 December 2015; Volume 28. [Google Scholar]

- Yeung, C.K.; Yeung, D.Y. Addressing two problems in deep knowledge tracing via prediction-consistent regularization. In Proceedings of the Fifth Annual ACM Conference on Learning at Scale (L@S ’18), London, UK, 26–28 June 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Gong, Z.; Luo, P.; Li, Z. DKVMN-KAPS: Dynamic Key-Value Memory Networks Knowledge Tracing with Students’ Knowledge-Absorption Ability and Problem-Solving Ability. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 55146–55156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, E.; Doucet, A.; Teh, Y.W. Augmented Neural ODEs. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019; Volume 32. [Google Scholar]

- Kidger, P.; Morrill, J.; Foster, J.; Lyons, T. Neural Controlled Differential Equations for Irregular Time Series. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Virtual, 6–12 December 2020; Volume 33, pp. 6696–6707. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, M.T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. “Why Should I Trust You?”: Explaining the Predictions of Any Classifier. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (KDD ’16), San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 1135–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Kim, H. Counterfactual Fairness Evaluation of Machine Learning Models on Educational Datasets. In Generative Systems and Intelligent Tutoring Systems; Graf, S., Markos, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 88–103. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.; Li, C.; Xing, W.; Lyu, B.; Zhu, W. Investigating perceived fairness of AI prediction system for math learning: A mixed-methods study with college students. Internet High. Educ. 2025, 65, 101000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]