1. Introduction

The welfare and safety of the elderly are paramount social and governmental concerns. A significant portion of the elderly live alone in their homes, often because they cannot afford specialised residential care facilities or they prefer their own home environment. This situation has resulted in incidents where a significant number of individuals are discovered deceased in their homes long after their passing [

1]. Research indicated that the incidence of unobserved deaths has risen considerably in recent decades [

2], underscoring an urgent need for effective home monitoring facilities. There is a technological need to detect and interpret abnormal or prolonged inactivity to alert care givers to perform a timely intervention [

3].

Patient monitoring technologies have undergone considerable improvements in recent years, mainly due to advancements in sensing and data interpretation technologies. Smartphones are now ubiquitous and are utilised by individuals across all age groups. They contain integrated movement detection sensors, such as accelerometers, that can be conveniently adapted for remote detection of abnormal movement activities by the elderly. Despite their widespread adaptation, the potential of these devices for continuous health monitoring has remained underutilised. This gap is partly attributable to the extensive focus on dedicated Internet of Things (IoT) devices in healthcare. While IoT devices have extensive potential, they often have limitations concerning power consumption, user acceptability, and requirements for complex installation [

4,

5].

Existing artificial intelligence (AI)-based solutions increasingly rely on deep learning models. Although these models are powerful, they frequently encounter difficulties with personalised behavioural analysis in time-critical emergency detection scenarios [

6,

7]. Furthermore, these models are conventionally trained on extensive and centralised datasets which inevitably introduce significant user privacy concerns. This study directly addresses these technological challenges by presenting a novel remote patient home monitoring application, specifically designed to improve the safety of the elderly living independently in their own homes [

7,

8].

The innovative feature of this application is its effective integration of the smartphone’s built-in accelerometer with AI interpretation of the user’s movement patterns in real-time. Its on-device (i.e., integrated in the smartphone) deep learning LSTM model is specifically devised to distinguish between the user’s normal movements and routine inactivity (such as sleeping), thus ensuring that alerts are only issued during true emergencies. Crucially, the LSTM model automatically trains on the individualised movement patterns after just one week of initial data collection, which significantly reduces the false alarms. The application also includes an option for follow-on update training when this becomes necessary. This intelligent, on-line training approach not only enhances the user privacy but also provides an essential reassurance to the caregivers by ensuring a timely intervention in emergency situations.

The primary contribution of this study is the development of an adaptive, personalised, real-time home monitoring application. The application effectively leverages accelerometery data and an LSTM-based AI model to reliably detect inactivity patterns. Its further contributions include the precise methodology for the LSTM’s training and its evaluation using a smartphone. This approach has potential to improve response time and consequently enhance patient safety in emergencies, particularly for the elderly who may be at a higher risk of medical emergency. By implementing an on-line training protocol for the AI model, the application both guarantees enhanced privacy and reduces reliance on an external server, ensuring a timely intervention, even in a resource-limited environment. Therefore, this work provides a significant contribution to the field, supporting the creation of a personalised, scalable, and efficient monitoring application that safeguards patient’s well-being and facilitates a rapid reaction during emergencies. In the following sections, the related literature is reviewed, the methodology used to design and evaluate the application is explained, and the results are discussed.

2. Literature Review

This section provides a review of the existing body of literature relevant to the current study. It aims to highlight the key contributions of the earlier studies, identify the existing limitations, and delineate the critical research gaps that necessitated the development of the application reported in this article.

2.1. Remote Patient Monitoring

The decision-making process in remote patient monitoring (RPM) is crucial for accurately recognising various activities, such as jogging, sitting, standing, and walking. Fuzzy logic is a technique previously used for this purpose, proving valuable for managing uncertainty when training data is limited [

9]. However, a significant drawback is that the inherent rules in fuzzy systems are fixed and cannot adapt to evolving user behaviours, which can restrict their real-world flexibility. This inflexibility constitutes a key research gap, one that can be effectively addressed by employing adaptive AI models. The models like convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and LSTM networks can learn movement patterns over time, thereby potentially offering superior performance and individualization [

10].

AI-based applications for patient home monitoring represent a paradigm shift in healthcare by enabling continuous tracking from remote settings. The ability of AI models to interpret complex information can provide informative decision making [

11]. Integration of deep learning with the Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) has potential to assist with healthcare diagnostics, treatment, and patient monitoring [

12]. Transformer-based deep learning models have been devised for real-time activity and fall detection of the elderly [

13]. An adaptive dilated transformer bidirectional long short-term memory (Bi-LSTM) was used as part of a secure wearable sensor-based remote healthcare monitoring device [

14]. The integration of smart devices, along with their built-in sensors, facilitates a real-time decision support environment. When these are combined with LSTM models, they facilitate an adaptive analysis that measurably enhances clinical decision-making [

15,

16]. By analysing individual patient datasets, these applications become capable of providing early detection of a patient’s health deterioration. A primary strength of AI in remote patient monitoring (RPM) is its ability to learn and implement personalised healthcare behaviours, which significantly improves outcomes in managing chronic diseases and providing dedicated elderly care.

The benefits and risks in utilising RPM in different patient groups have received varied levels of investigation [

17]. For example, RPM is cancer patients has been associated with a significant reduction in the length of hospital stay, emergency department visits and hospital readmissions [

18]. RPM deployment should consider care transition from an inpatient hospital environment to a home setting to facilitate its successful adaptation [

19]. The considerations include patient’s safety, adherence to the prescribed medical guidance, quality of life and the financial implications. RPM development should involve affected patients through a codesign process. The codesign ensures an active participation of stakeholders, e.g., technologists, patients, and health providers, in the conceptualisation, design, and deployment of RPM devices, systems, and services [

20]. The importance of a patient-centred approach to RPM development has been emphasised in a study involving high-risk oncology patients [

21]. Retention of patients included in an RPM programme is an important consideration. In a study involving diabetic patients, it was reported that being younger or having higher blood glucose or blood pressure at the baseline increased the risk of withdrawing from an RPM programme [

22]. A study has explored patients’ experiences of RPM for chronic management focusing on health literacy and therapeutic relationships [

23]. RPM deployment in rural and regional areas can have its own specific challenges that could include inadequate literacy, language barriers, disparity in IT infrastructure and devices, reliability of services, training opportunities, and funding models [

24]. The devices used for RPM should have a carefully designed user interface for the intended patient group to ensure acceptability across a wide range of patients with varying IT skills [

25].

The complexities in RPM have resulted in integrated care practices that accommodate technology design, service design, and organisational structures and policies [

26]. A review article has examined the pros and cons of RPM [

27]. Its pros included issues such as providing continuous monitoring, facilitating early detection, cost efficiency, convenience, and comfort of the patients. For its limitations the article highlighted issues such as data accuracy and reliability, privacy and security risks, technical barriers, and compliance factors. A study has recommended considerations to assist in the design and implementation of RPM [

28]. These included the codesign of RPM devices with the intended users, interactive capability, and having dedicated professional responsible for monitoring data and communication.

To successfully construct an intelligent application that can adaptively track a patient’s unique movement activities across time, LSTM networks are an ideal choice. These networks are a specialised form of recurrent neural networks (RNNs), specifically designed to model sequential data [

29]. When an LSTM is trained using accelerometery data, it gains the ability to analyse time-series activity patterns. It then uses this data to monitor the patient’s overall activities and to respond appropriately to emergencies. However, these methods are not without their limitations. Traditional AI models are typically trained on powerful, centralised servers using extensive datasets. This conventional workflow necessitates that all personal data to be transmitted over the internet to remote systems, raising serious concerns regarding privacy breaches and potential security threats [

30,

31,

32]. A substantially safer and more patient-centric approach involves training these models directly on the user’s own smartphone. This approach keeps the individual’s data confidential locally, ensuring that the users retain greater control over their collected personal information.

2.2. On-Device Training to Mitigate Data Risks

The development of on-device AI models has attracted considerable interest for its capability to facilitate real-time processing and enhance data privacy by keeping all computations on edge devices [

33]. This approach effectively addresses the requirement for highly efficient health tracking solutions. In contrast to the cloud-based systems, for on-devices, their AI handles data processing directly on the smart device, thereby reducing reliance on external servers. This feature is especially pertinent for immediate-response situations, such as detecting falls or prolonged inactivity. A primary benefit of on-device AI approaches is their ability to offer continuous monitoring without requiring an active internet connection, significantly increasing reliability, particularly in remote areas. Moreover, by ensuring data is processed locally, an on-device solution substantially reduces the privacy concerns typically associated with server-oriented architectures [

34]. This localised approach also reduces overall computational demands, which makes personalised health monitoring more widely accessible [

35].

2.3. Activity Monitoring Using Smartphone Sensors Integrated with AI

Smartphone-based accelerometer sensors have rapidly emerged as promising tools for RPM. They can provide a low-cost, scalable, and user-friendly solutions for continuous health assessments. These integrated sensors facilitate the detection of physical activities without the requirement of an extra hardware. Recent research has demonstrated that an accelerometer-based data can classify human activities with a high degree of accuracy, strongly supporting their viability in mobile health applications [

36].

Studies have reported that employing smartphone accelerometers for patient monitoring is both practical and practical to administer. As smartphones are already a routine part of daily life, patients are not compelled to wear intrusive, supplementary devices or fundamentally alter their daily routines. A study indicated that smartphones could reliably pick up changes in activity levels, thereby making healthcare more accessible and considerably less expensive, which is especially important for long-term care scenarios [

35].

We summarise this literature review by highlighting four major challenges in the current RPM approaches that can limit their effectiveness. These include difficulties in operation by the elderly users; reliance on rigid, fixed fuzzy rules; the transmission of patient data over the internet, which raises security concerns; and a dependency on external sensors, which increases the cost and maintenance complexity due to required cloud services. To systematically address these limitations, our proposed solution offers several advantages. Firstly, it introduces a lightweight, user-friendly application that demands minimal interaction from the elderly. Secondly, it incorporates an adaptive deep neural network model based on LSTM to significantly enhance both accuracy and flexibility. Additionally, the entire system, including model training, operates exclusively on a smartphone that eliminates the need for data transmission and greatly enhances data privacy. Lastly, by utilising only the smartphone’s built-in accelerometer, the solution removes the need to purchase supplementary equipment, thereby reducing the overall cost significantly.

3. Design of the RPM Architecture

The proposed application consists of an Android-based RPM software application, specifically designed to identify abnormal physical activities using the smartphone’s integrated motion sensors. This includes an embedded LSTM-based machine learning inference engine that runs entirely on the smartphone. The overall architecture was optimised to operate autonomously on commercially available Android handsets, effectively removing the necessity for external devices or continuous connectivity to cloud services. The application functions by continuously monitoring the user’s movements, capturing their real-time motion data, and analysing it locally using an LSTM model that identifies potential fall incidents or other abnormal movement patterns. Once detected, the application automatically initiates real-time alerts directed to designated caregivers.

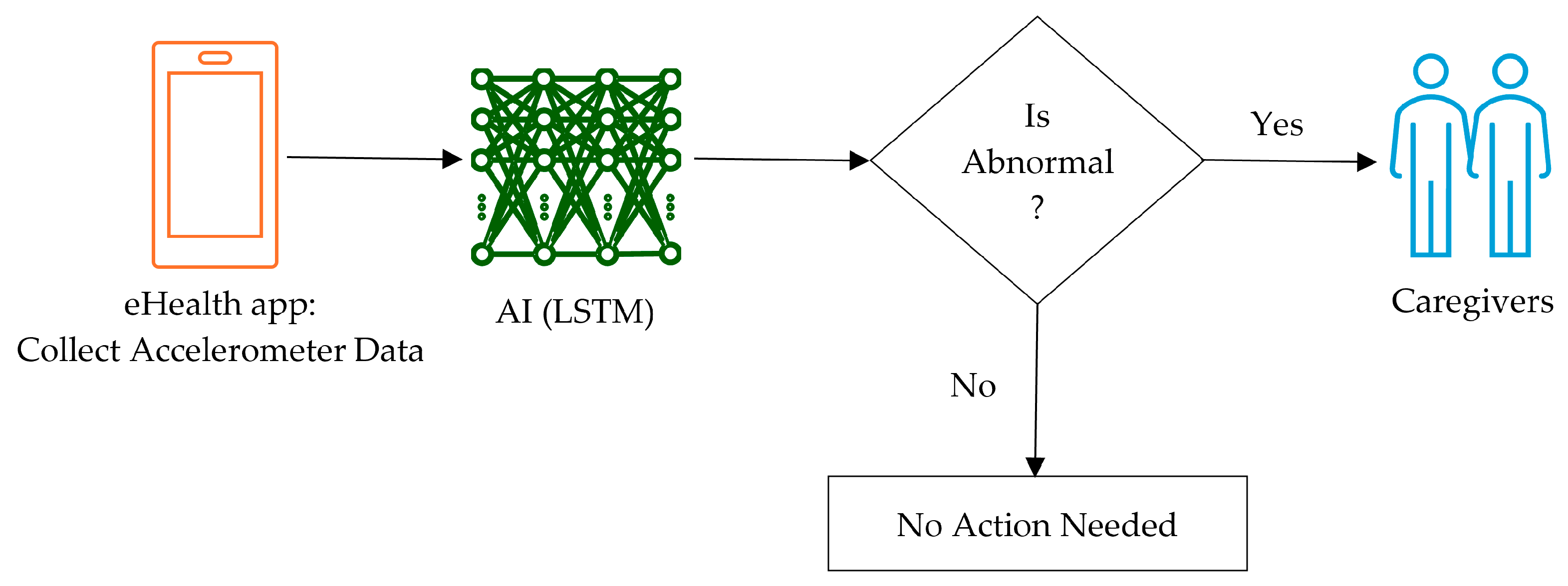

Figure 1 illustrates the overall application’s architecture and the flow of data. This diagram includes the sensor input, the processes of on-device data analysis, the classification stage, and the final alert notification module.

The core of the application is an LSTM artificial neural network, specifically implemented to detect unusual movement patterns and accurately identify fall incidents and unusual periods of inactivity. Once these events are detected, the application automatically triggers and sends real-time alerts to pre-designated caregivers through an email and an SMS. This section provides a comprehensive description of the application architecture, the process used for data collection, the configuration of the LSTM model, the alert mechanisms, and the final evaluation of the application’s performance.

The core functionality of the application is delivered through a native Android application developed in Kotlin (version 1.9.0) utilising the Android Studio Hedgehog (2023.1.1). To guarantee compatibility across current devices, the application was rigorously tested on a selection of smartphones operating on the Android 12 or a higher model. Testing devices included the Samsung Galaxy A53 5G, A73 5G, and M54 5G (Samsung Electronics, Suwon, Republic of Korea), the Huawei P30 and P40 (Huawei Technologies, Shenzhen, China), and the Google Pixel 7a (Google LLC, Mountain View, CA, USA).

The application captures motion data using the smartphone’s integrated accelerometer sensor. This data is then pre-processed directly on the smartphone and temporarily stored within a local SQLite database. This strategy of using a lightweight offline data processing allows the application to remain functional even without continuous access to the internet. A machine learning inference engine, written in Python (version 3.10.x) and implemented using TensorFlow Lite (TFLite version 2.13.0), is fully integrated into the application to facilitate efficient, on-device monitoring. This engine employs a trained LSTM model to analyse motion patterns in real time and successfully identify potential fall incidents or abnormal movement patterns.

When an unusual movement is detected, the application immediately activates alerts across several mechanisms. These include email notifications, local alerts on the device, and emergency messages sent to caregivers whose details have been pre-configured using either SMS or internet-based messaging services. When no abnormal activity occurs, the application continues its silent operation in the background, ensuring the user’s routine use of the smartphone is not interfered. This architecture delivers a solution for continuous real-time monitoring that is scalable, cost-effective, and conscious of user privacy. It is highly suitable for deployment in both home-based care and clinical environments. By deliberately removing the requirement for external hardware or persistent reliance on cloud connectivity, the system supports practical and efficient deployment across a wide range of real-world settings.

4. Materials and Methods

This study employed a quantitative experimental approach for the design, development, and evaluation of a smartphone-based home monitoring application underpinned by AI. The application was evaluated using data recorded from 25 healthy adult volunteers, comprising males and females aged 40 to 70 years. This diversity in age and gender ensured the application could be assessed across a wider range of user profiles, thereby enhancing the generalisability and real-world applicability of the findings. The study had ethics approval from Sheffield Hallam University Research Ethics Committee, the ethics application code is ER76195762.

4.1. Data Collection and Preprocessing

The application continuously gathered movement data from the smartphone’s integrated triaxial accelerometer to monitor user activity in real time. The recorded raw sensor readings consisted of acceleration values along the

x,

y, and

z axes of the phone’s accelerometer, each paired with its corresponding timestamp. To effectively standardise the data, each axis value underwent normalisation by dividing its values by the standard gravitational acceleration (9.81 m/s

2), resulting in the normalised values

xg,

yg, and

zg. Based on these derived values, a signal magnitude vector (SMV) was subsequently generated to provide a measure of the overall intensity of movement, determined as follows:

This approach is widely adopted in human activity recognition systems that rely on smartphones and has been proven effective at capturing meaningful motion patterns [

37]. The raw accelerometer values were initially sampled at 200 Hz to ensure the capture of fine-grained motion details, particularly sudden impacts. However, to ensure efficient on-device processing and long-term pattern analysis, this raw data underwent aggregation. The data points were temporarily collected in 1 s intervals and stored in an in-memory list over a 60 s window. At the end of each 60 s window, the highest SMV peak value recorded within the period was identified and saved, along with its corresponding timestamp, in a local SQLite database. This sequence of peak SMV values, representing a single data point per minute, served as the univariate time-series input for the LSTM model, thus enabling sequential analysis of user movements for the accurate detection of falls and other unusual motion patterns [

38]. Using SQLite for local data storage provided several distinct advantages. It eliminated any reliance on cloud-based services, thereby ensuring that sensitive user data remained secure and private directly on the device. The application was specifically configured to retain up to three months of historical activity data, which facilitates both long-term movement pattern analysis and trend monitoring.

4.2. LSTM Model and Activity State Classification

At the end of every 60 s window, the application identifies the highest SMV (i.e.,

) from the recorded accelerometer readings. This observed value is then immediately compared to the corresponding predicted value generated by the on-device LSTM model

. This model has been trained to learn and recognise the user’s normal movement patterns [

39,

40]. This critical comparative approach allows the system to effectively distinguish between the expected day-to-day fluctuations in movement activities and genuine, significant anomalies. The classification system is driven by two key derived metrics and a set of predefined thresholds (ϵ, τ

1, τ

2):

Prediction Error (

E): This metric quantifies the absolute deviation of the observed movement activity from the LSTM’s prediction:

Relative Anomaly Score (

AR): This score is particularly sensitive to rapid, high-magnitude changes in movement intensity, calculated as the percentage increase in the actual SMV over the predicted SMV:

The application employs the pre-defined thresholds (ϵ, τ

1, τ

2) and applies them to these calculated metrics to subsequently classify the movement into one of five distinct states. The tolerance threshold for confidently declaring a “Normal” state is specifically defined as ϵ = 0.05 g. Based on these metrics and the established thresholds, the application categorises each time window into one of five clear movement pattern states that are formally outlined in

Table 1. The integration of LSTM-based pattern prediction with these dynamic, rule-based heuristics facilitates a highly fine-grained differentiation of real-world movement behaviour.

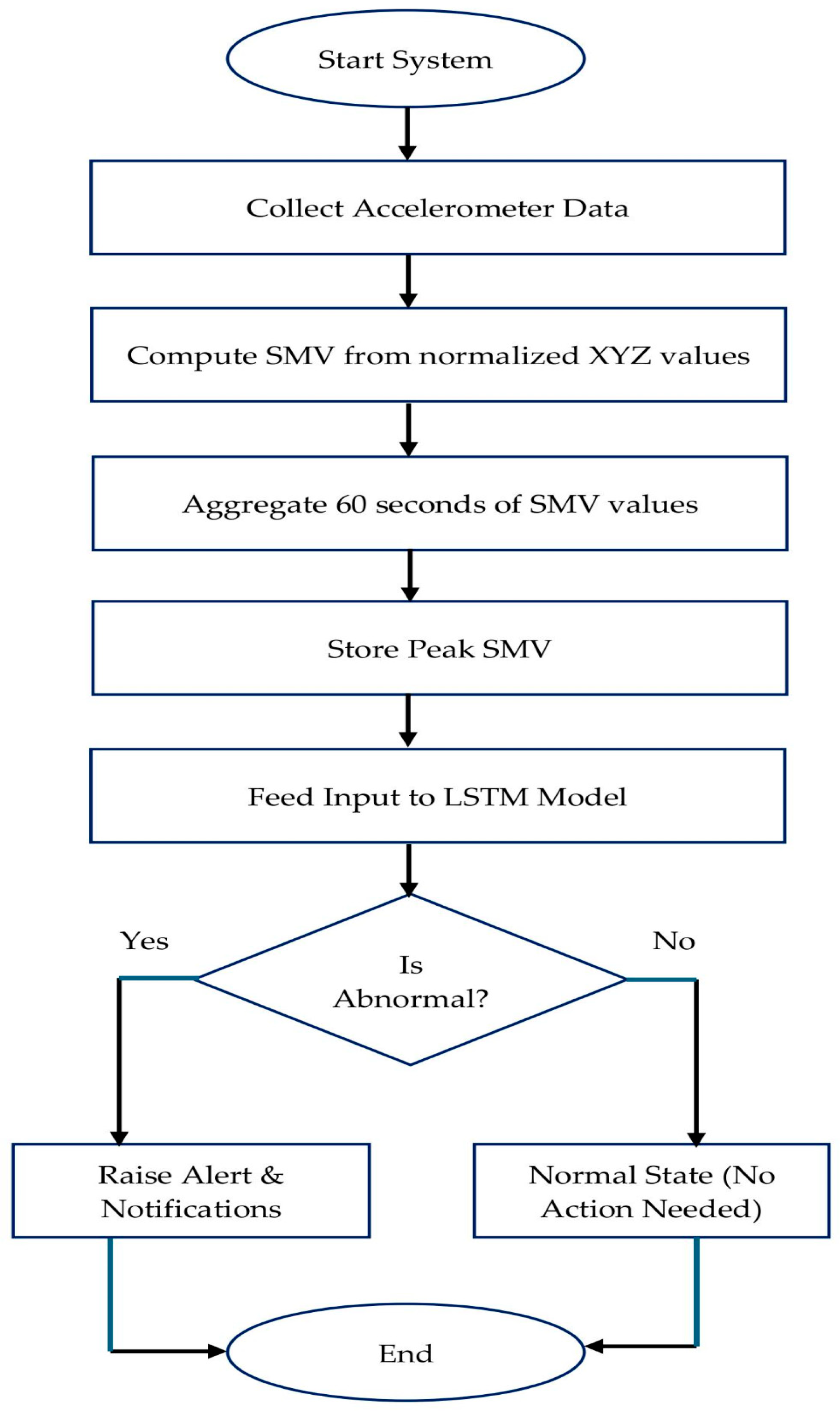

Figure 2 visually represents the overall system flow, where the decision block labelled ‘Is Abnormal?’ encapsulates the entirety of the multi-state classification logic detailed within this section and

Table 1, ultimately leading either to the initiation of an alert or to no further action.

4.3. LSTM Model Architecture and Training

The LSTM model, a variant of the recurrent neural network (RNN), was specifically chosen for its outstanding capability to recognise time-dependent patterns within sequential data. Unlike standard feedforward networks, the LSTM is equipped with an internal memory cell that allows it to selectively retain or discard information over various time steps. This capability is essential for effectively analysing accelerometer signals, where the sequential order of a user’s movements is necessary for correctly identifying activity patterns, such as walking, resting, or detecting a fall [

41].

In this application, the LSTM is structured as a univariate time-series regression task focused on abnormal movement detection. Its core objective is to predict the expected peak signal magnitude vector (SMV) value for the upcoming minute

by analysing the movement intensity patterns that preceded it. The input sequence consists of the last N = 60 peak SMV values (representing the preceding one hour of activity, with one value recorded per minute). This hour-long context is important for generating a reliable prediction. The output is a single predicted SMV value, which is then continuously compared against the actual observed peak

within the current minute to determine the user’s activity state, as outlined in

Section 4.2 [

39,

40]. The architecture itself comprises an LSTM layer with 128 hidden units, followed by a Dropout layer with a 30% rate to mitigate overfitting. This feeds into a fully connected dense layer (64 neurons, (Rectified Linear Unit activation function), and finally, a single-neuron output layer with a linear activation function used for the regression task.

A key element of this system is its personalised, on-line training protocol, designed explicitly to counter the high false-alarm rates common in generic models. The application initiates a learning phase upon initial deployment, collecting the first seven days of the user’s aggregated SMV data to establish a stable, personalised baseline. Following this, the model is fine-tuned on a rolling basis: once every 24 h, the LSTM undergoes a brief re-training process using only the most recent seven days of the user’s data to adjust its internal weights. This daily fine-tuning involves a limited number of epochs (typically 5) and employs the Adam optimizer. By consistently updating its knowledge, the model adapts successfully to the routine changes, significantly minimising the prediction error for normal activities and reducing false positive alerts. The entire procedure is performed locally on the smartphone using TensorFlow Lite (TFLite), which guarantees both data privacy and operational autonomy.

To maintain high sensitivity to genuine anomalies whilst preventing the model from over-fitting to routine fluctuations, this daily re-training protocol is highly constrained. The system employs only the most recent seven days of the user’s data for fine-tuning, restricting the adjustment to a maximum of 5 epochs. The Mean Squared Error (MSE) is used as the loss function. This choice strongly penalises larger prediction deviations that helps the model swiftly anchors itself to the individual’s stable activity baseline. This approach achieves essential personalization without compromising predictive stability on the mobile hardware. Training was conducted using the Adam optimizer. The MSE was the primary loss function, with the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) tracked as a secondary evaluation metric. The overall protocol included a maximum of 50 epochs, a mini-batch size of 32, and an 80:20 split between the training and validation data. To further prevent overfitting and reduce unnecessary computation time, early stopping was implemented with a patience threshold set at 10 epochs. This configuration represents a practical compromise between achieving high accuracy, maintaining computational efficiency, and ensuring real-time performance on resource-constrained smartphone devices.

4.4. Alert Generation and Notification System

Once the user’s activity has been classified based on the comparison between the actual and the predicted movement magnitudes, the application proceeds to determine whether the resulting state necessitates intervention. In the event of an abnormal state, e.g., a detected fall, unexpected idleness or sudden unusual activity, an alert is promptly generated and sent to the user’s pre-configured emergency contacts using both email and SMS communication channels. The alert was deliberately devised to be proactive, highly responsive, and unobtrusive. It functions asynchronously, which ensures that critical notifications are dispatched without interfering with the primary application workflow. When an emergency state is identified, the application automatically drafts an alert message, incorporating personalised details like the user’s name and the contact’s name. The email alert utilises a structured HTML template that clearly outlines the nature of the detected abnormal activity and suggests appropriate actions, such as checking on the individual and reviewing their recent data via the mobile application. This email is directed to the designated caregivers. Simultaneously, a concise SMS message with emergency wording is sent to ensure the fastest possible delivery and visibility. All generated alerts are systematically recorded in a local database, capturing the contact details, the precise time of the alert, and the reason for the notification to support future auditing and application evaluation.

If the user subsequently confirms that they are safe, for example, by interacting with a safety confirmation feature within the application, the application transmits a follow-up notification to the same contacts. This subsequent message reassures caregivers that no immediate action is required thereby effectively reducing unnecessary worry or panic. The entire alert mechanism is designed with fail-safety and redundancy as its core principles, supporting both internet-based communication (Email) and cellular networks SMS to maximise delivery reliability, even in situations where connectivity may be limited. This multi-channel, real-time notification application constitutes a critical element of a broader remote patient monitoring framework, ensuring a timely response to potentially life-threatening events.

5. Results

This section presents the experimental findings and the performance validation of the developed smartphone-based remote monitoring application. The application underwent rigorous evaluations with 25 volunteer participants. The participants were university staff, PhD students, and MSc students. Each participant installed and utilised the application on the provided mobile phone (all an identical model) over a continuous period of two months. These comprehensive evaluations were specifically designed to assess the application’s effectiveness in detecting both critical abnormal events (such as simulated falls) and prolonged periods of inactivity, ensuring that timely alerts were reliably triggered when necessary.

5.1. Evaluation and Performance

The proposed LSTM-based activity classification application was evaluated through a combination of standard model performance metrics and rigorous real-world testing involving human participants. The comprehensive dataset used for this testing was gathered from 25 volunteers (both male and female, aged 40–70), who performed routine daily activities (for instance, walking, sitting, and standing) and simulated fall scenarios under controlled indoor conditions. These varied evaluation tasks ensured that the model was assessed across a wide range of activity profiles and abnormal motion patterns.

While the analysis involved all 25 participants, the specific time-series activity plots and the critical alert performance graph presented in this paper are derived solely from the two-month monitoring data of a single, representative individual (Participant-1, a male, 62 years old). This focused, case-study methodology was adopted because the personalisation trends observed, specifically the marked reduction in false positives during the first week of training were consistently representative of the overall group’s general pattern. Presenting this detailed, individualised data offers a clearer illustration of the LSTM’s adaptive learning process than a potentially diluted, averaged group analysis.

For the regression-based fall detection model, performance was evaluated on a held-out validation set using standard regression metrics: Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Mean Squared Error (MSE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and R

2 (Coefficient of Determination). These results are shown in

Table 2.

An R2 value of 0.931 indicates that the model can account for 93.1% of the variance present in the actual SMV values that clearly demonstrates its strong generalisation ability. The observed low values for both MAE and RMSE further confirm that the predicted values remain consistently close to the observed values, even during periods when motion fluctuates rapidly. These results collectively prove the model’s effectiveness in accurately predicting movement intensity and capturing the temporal dynamics inherent in human motion.

To rigorously evaluate the application’s capacity to classify the five distinct activity states, we assessed its performance based on the formalised classification logic detailed in

Section 4.2. Although the application achieved a strong overall classification accuracy of approximately 93% across all activity types, performance was primarily gauged using metrics that focus specifically on patient safety and the crucial need to minimise alert fatigue: sensitivity (true positive rate) and specificity (true negative rate).

The regression metrics presented in

Table 2 form the foundational basis for the application’s operation. The high (close to 1) R

2 value of 0.931 confirms that the personalised LSTM model successfully learns and replicates 93.1% of the variance observed in the individual user’s movement patterns. This high level of predictive accuracy is essential, as the system’s overall effectiveness is directly reliant on the model’s capacity to accurately forecast normal movement. When the disparity between the predicted and actual SMV values exceeds the established thresholds (Equations (2) and (3)), it reliably signals a true anomaly. The subsequent section evaluates the results of the on-device personalisation against real-world data from the testing phase, which confirms the application’s effectiveness in minimising false alarms, a significant limitation of typical generalised monitoring systems.

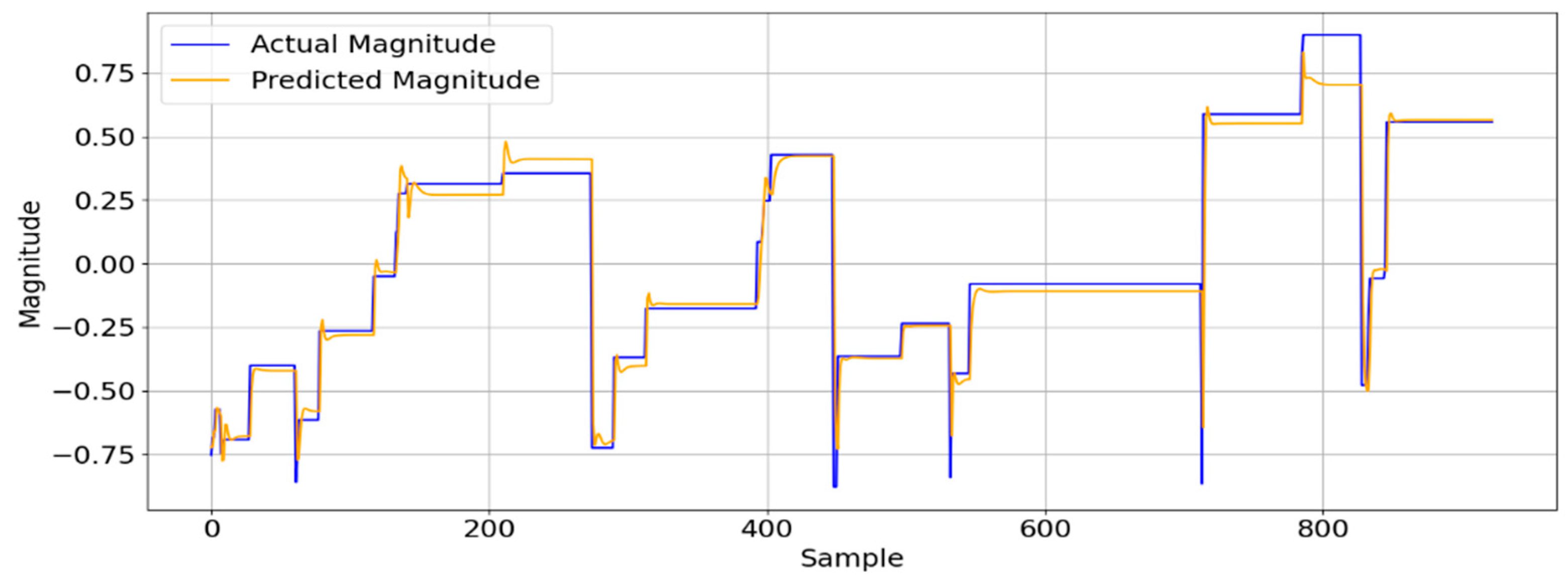

A visual comparison between the actual SMV values and the LSTM model’s estimated SMV is displayed in

Figure 3.

This specific example is derived from the data collected from a 62-year-old participant during the validation phase. While the figure focuses on a single individual, a similar close alignment was consistently observed across the other participants. Rather than merely forecasting future values, the LSTM model utilises sequential SMV inputs to identify patterns that are indicative of either normal or abnormal motion. The close tracking observed between the actual and estimated SMV values demonstrates the model’s ability in recognising real-time variations in movement, thereby supporting accurate activity classification and timely alert generation. The predicted SMV values (illustrated in orange) generated by the LSTM model track the actual SMV values (illustrated in blue) very closely. This clearly demonstrates the model’s robust ability to learn and accurately replicate real motion patterns. This visualisation was generated using a Python script based on test sequences gathered from the human participants.

5.2. Activity Monitoring and Behavioural Trends

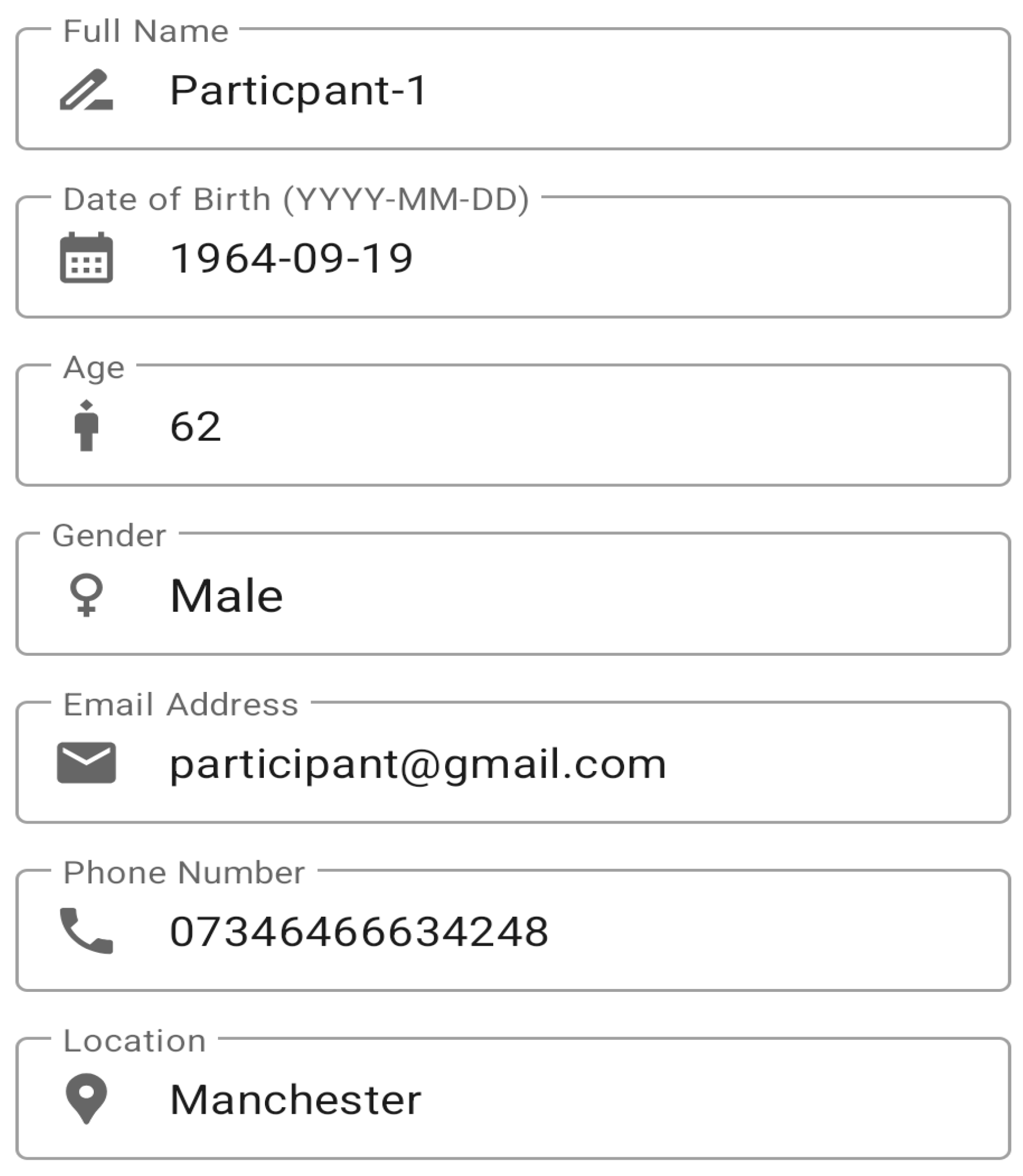

This section presents the real-world operational results of the application, focusing specifically on how the monitored activity data is both collected and visualised. Most critically, it examines the direct influence of the on-device LSTM’s personalised learning on alert reliability. The initial configuration of the mobile application was deliberately devised to be straightforward and user-friendly, requiring only minimal input from the user. The participant details form, shown in

Figure 4, facilitates the entry of the monitored individual’s demographic and contact information, including their full name, age, and location.

Complementing this, the Add/Update Caregiver interface, illustrated in

Figure 5, provides a structured form for inputting caregiver details. The design of this form follows a sequential and minimal-interference methodology, necessitating that users only enter basic demographic and contact information. When previously stored caregiver details require modification, the same interface is automatically repurposed into an updated mode, with fields pre-filled with the existing data to minimise the user’s learning curve.

The Participant and Caregiver Details Summary Dashboard, shown in

Figure 6, serves as a central hub that links the monitored individual with their caregiver. The screen provides a clear overview of the participant’s key demographic information at the top, while a dedicated list below shows a summary of each registered caregiver’s contact details and relationship to the participant.

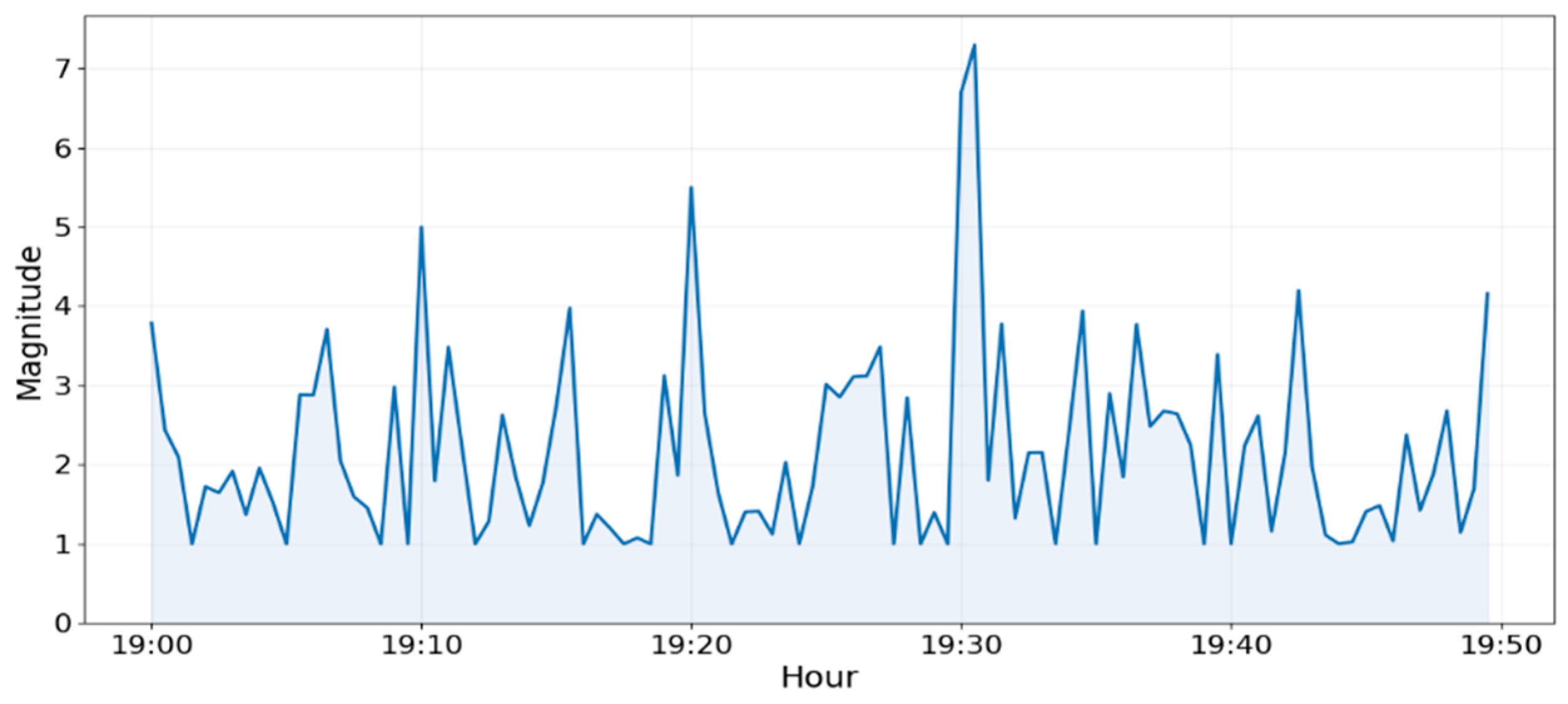

The monitoring interface provides a clear, easily interpretable view of a user’s activity levels across different time scales, which the on-device LSTM model then uses to learn the user’s habitual, normal routine. As

Figure 7 demonstrates, the “Hourly Activities” graph displays the recorded movement magnitude, highlighting the periods when activities are heightened.

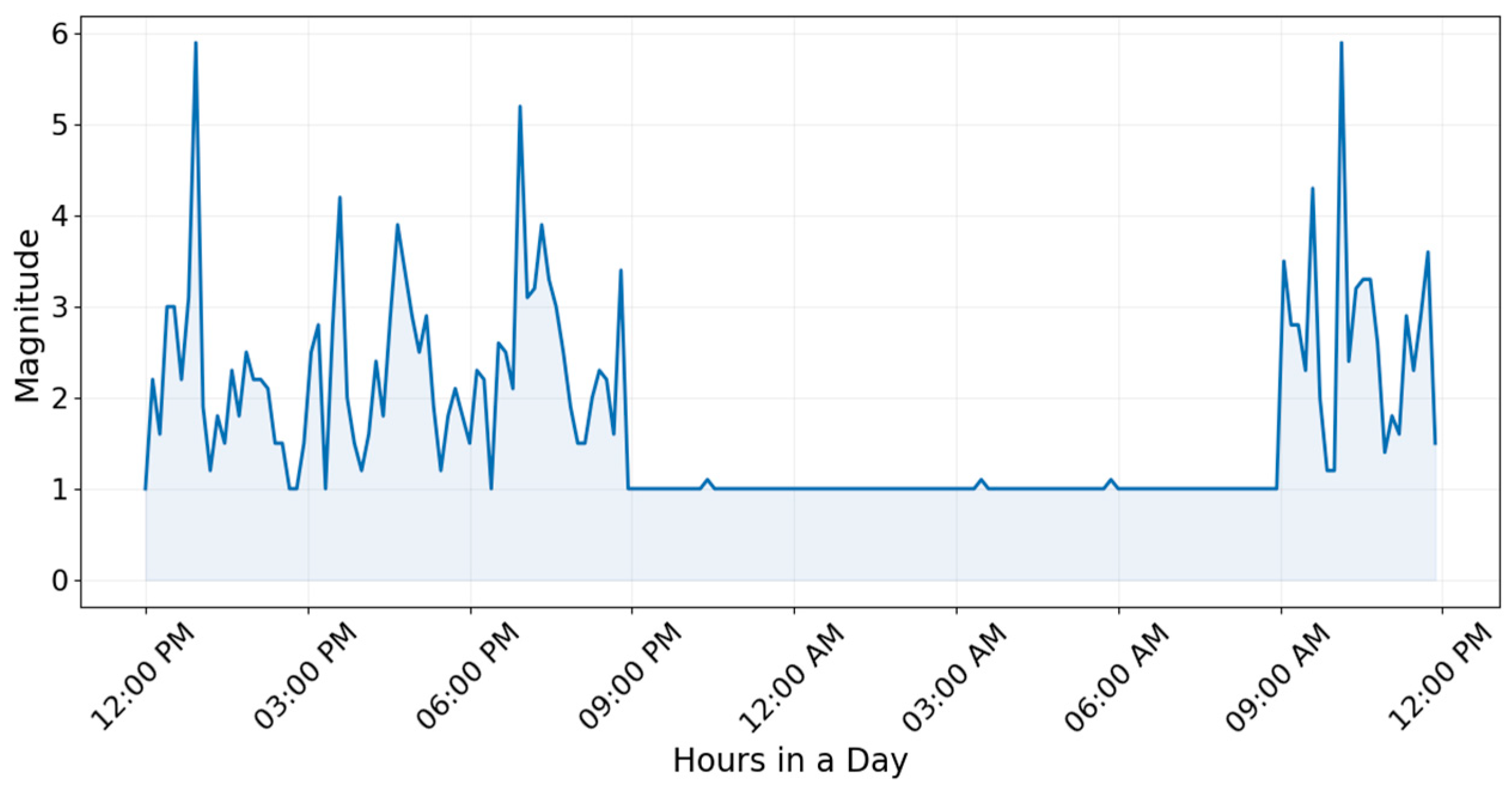

These data points, visible as sharp spikes, indicate that the user is actively moving, probably using the phone, walking, or engaging in other movements while carrying the device. The model analysed these specific patterns to gain an understanding of the user’s hourly movement patterns. The “Daily Activities” graph, represented in

Figure 8, offers a broader view by summarising the maximum magnitude of movement recorded over each 24 h period.

The application utilises these daily trends as a core input for the LSTM model, enabling it to learn and appropriately account for natural variations in physical activities across days. By analysing these visualised plots, the application builds a robust understanding of the user’s customary activity patterns, which is critical for identifying significant deviations that justify generating an alert.

The application continuously gathers and analyses motion data utilising the smartphone’s integrated accelerometer. This data is processed by the on-device LSTM model that is trained to recognise the user’s unique patterns of physical activity across time. By closely monitoring the daily and weekly variations in movement intensity, the model successfully establishes a personalised behavioural baseline for every user, making it far more effective at detecting anomalies.

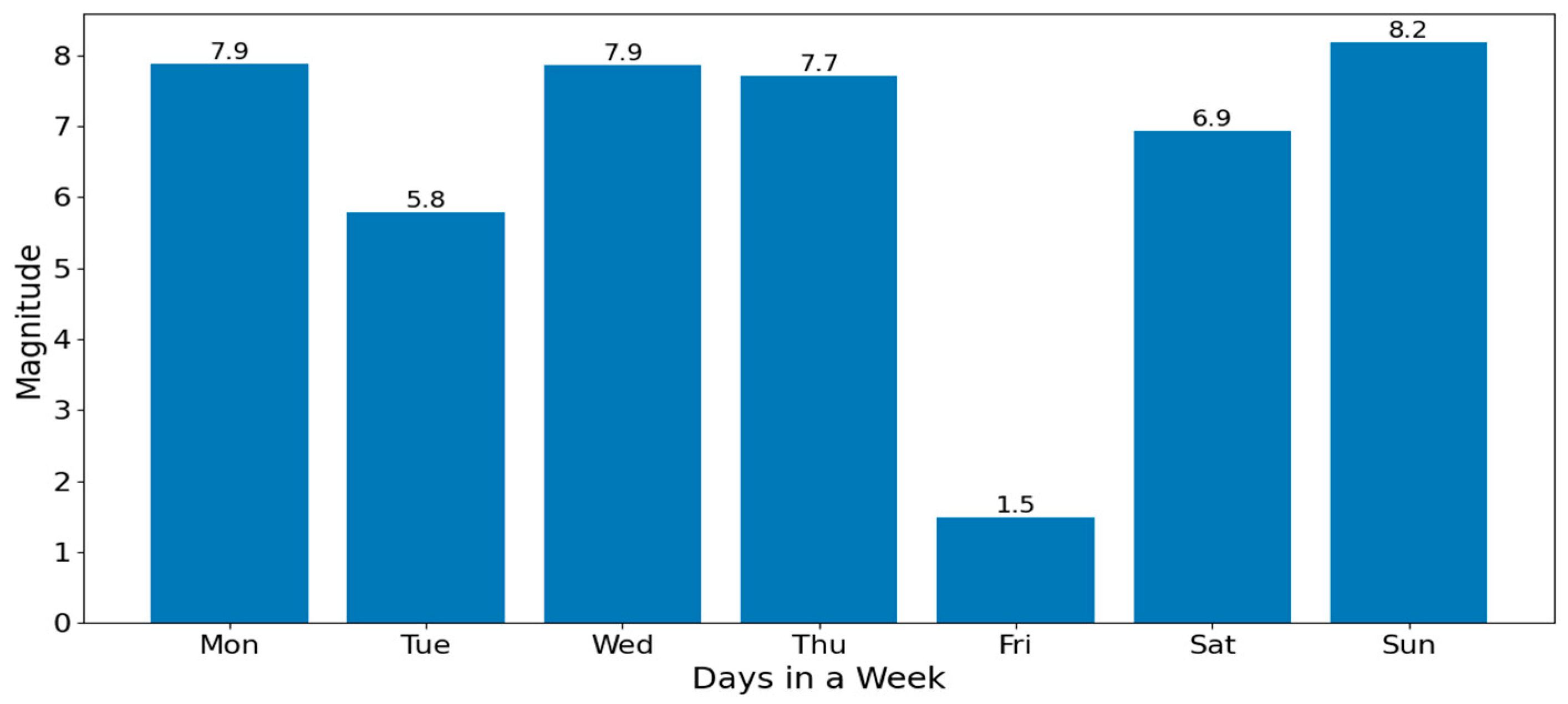

The “Weekly Activities” bar chart (shown in

Figure 9) visualises the maximum movement magnitude recorded each day over the past seven days.

These values, which ranged from 1.48 to 8.18 in our evaluations, represent key indicators of the user’s daily physical intensity. Higher values reflect more active days, while conversely, lower values suggest minimal movements. The LSTM model strategically uses these daily peaks to reinforce its understanding of the short-term fluctuations present in the user’s routine.

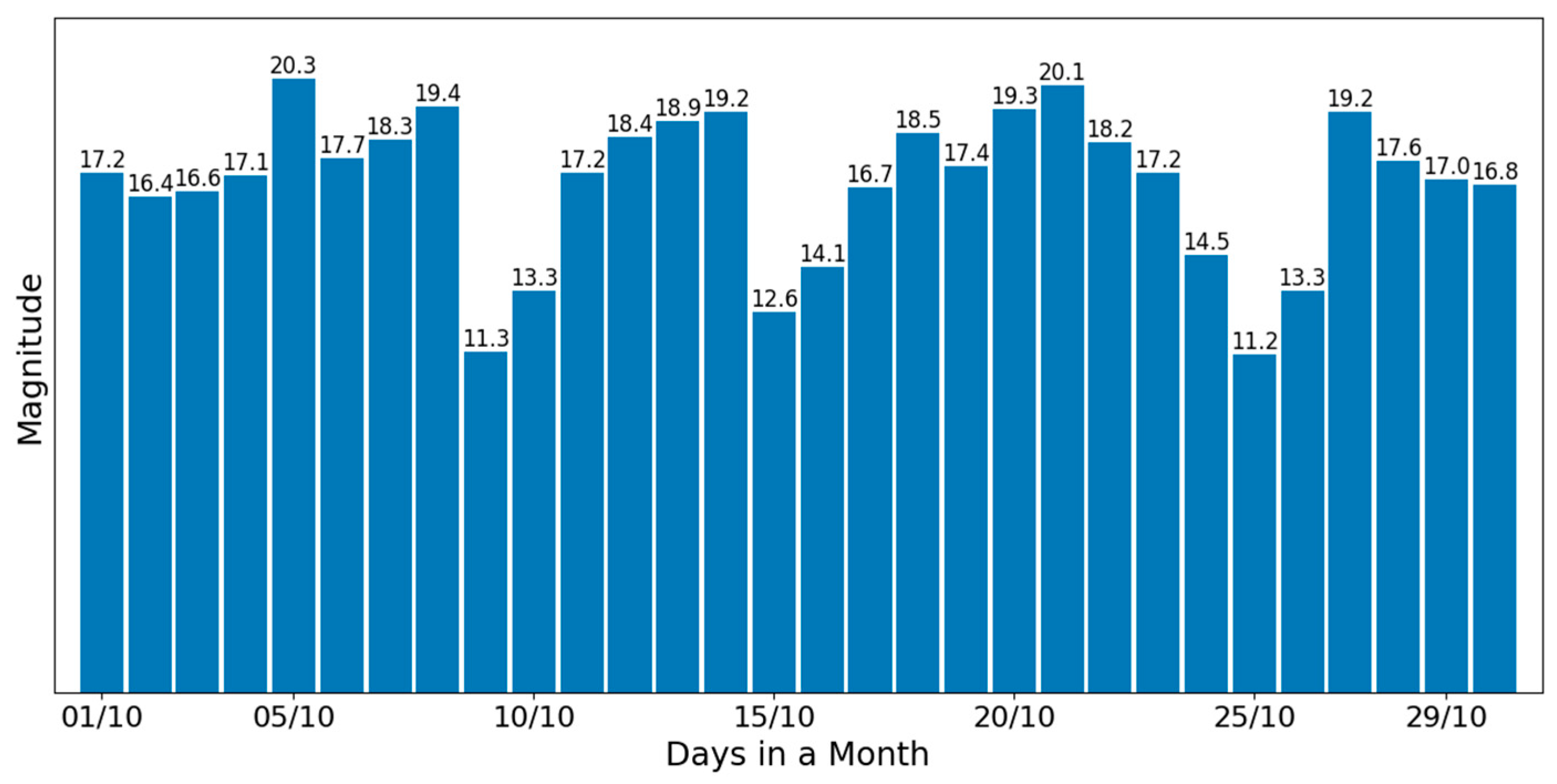

Similarly, the “Monthly Activities” chart (shown in

Figure 10) offers a broader perspective on long-term behaviour by displaying the maximum daily magnitude for every day of the month.

This extended history allows the model to further refine its baseline and successfully identify prolonged deviations from typical activity levels, e.g., sustained inactivity or unexpected surges in movement that could potentially signal emergencies requiring a caregiver’s urgent attention.

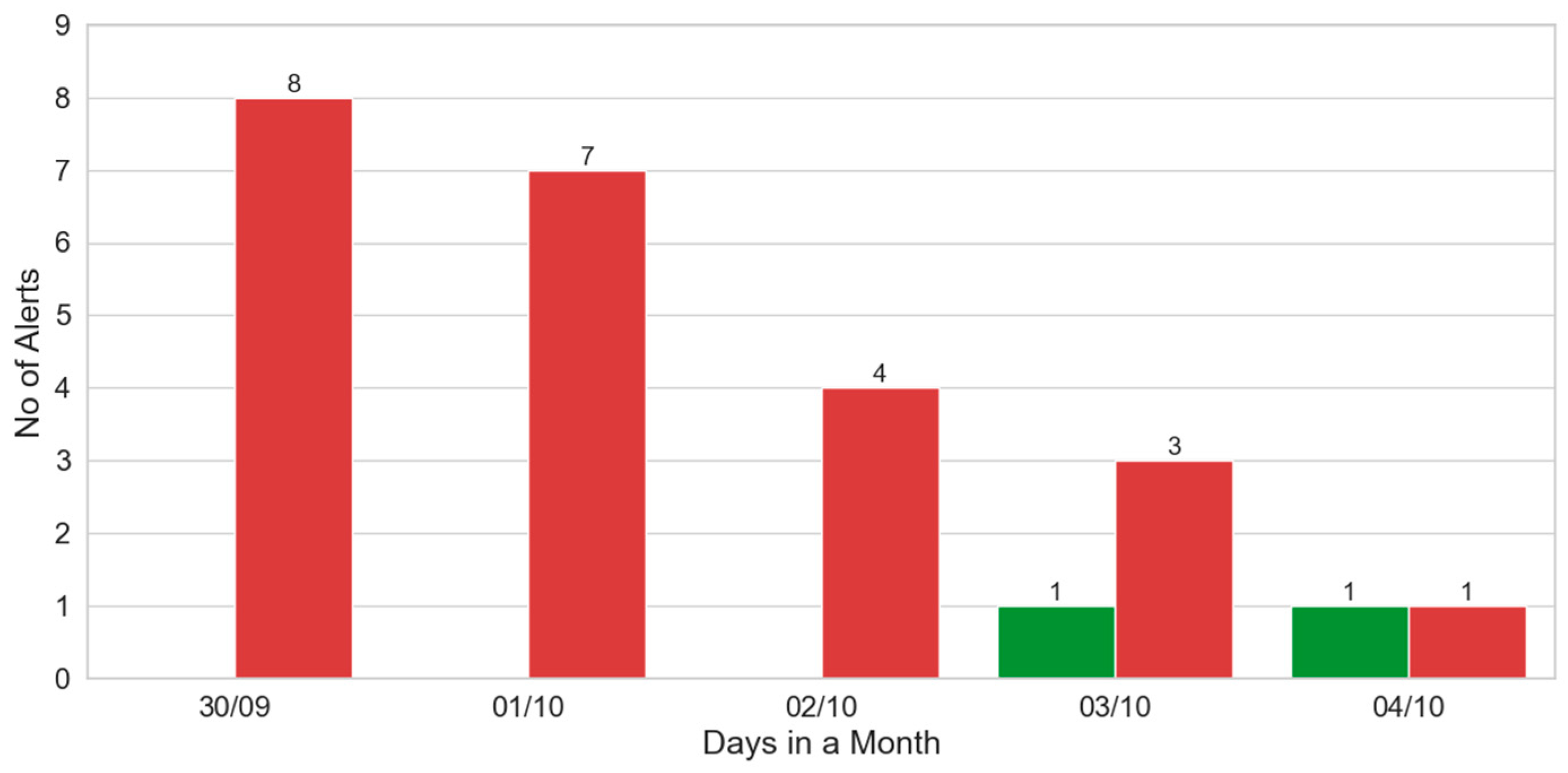

The monitoring interface offers critical insights into both the system’s operational performance and its decision-making process.

Figure 11 displays the “Number of Alerts by Day” bar chart, which tracks the system’s activity across the testing period.

The red bars on the chart represent the number of alerts successfully transmitted to a caregiver following the detection of an abnormal movement pattern. This figure visually confirms the success of the on-device fine-tuning protocol that was defined in

Section 4.3 The

x-axis indicates the days of the month during the test period, and the

y-axis shows the corresponding number of alerts. initially, the red bars (‘Not Okay’) largely represent system-generated alerts that were effectively false positives. Crucially, as the LSTM model has learnt the participant’s unique movement patterns over the first few days (from 30 September 2025 to 4 October 2025), the number of these false alarms progressively decreased from 8 on the first day to just 1 on the final day. This outcome clearly demonstrates the model’s ability to reduce false alarms and significantly enhance its predictive specificity through continuous, adaptive learning.

The application provides an Emergency Assistance interface to allow participants to communicate their status directly to their caregivers. This screen presents two clear, distinct buttons for immediate user action. If a genuine emergency arises, the participant can press the prominent ‘Emergency!’ button to instantly transmit both SMS and email alerts to the designated caregivers, ensuring a prompt notification and response. Alternatively, if the participant secures their safety, or if a system-generated alert was triggered unintentionally, they can press the ‘I Am Okay!’ button. This action sends a follow-up notification to the caregivers to confirm the user is safe and alleviates any unnecessary concern. This purposeful design supports timely communication, successfully reduces caregiver anxiety, and ensures that genuine emergencies are given the necessary priority for rapid intervention.

5.3. Mobile Application Notifications

Upon anomaly detection, the application consistently dispatches timely alerts to designated emergency contacts via email (using SMTP) and SMS to the primary carer. The alert content is structured for immediate action. The automated email carries the subject “Urgent: Abnormal Activity Detected” and explicitly instructs the caregiver to check on the individual and review the application’s activities, providing three distinct required actions. The corresponding SMS message, designed for rapid delivery, provides a concise, urgent warning: “This is an automated message! [Participant-1] needs emergency! From eHealth.”

Should the ‘I Am Okay’ button be selected, the user’s status is immediately updated. Concurrently, both an SMS and an email notification containing the message ‘All is well’ are dispatched to the designated caregiver. Furthermore, when the ‘I Am Okay’ button is selected, the application registers this event locally in the SQLite database (referencing

Table 3 and

Table 4), marking it as an instance where the alert required user override. This logging process is crucial, as it provides audit data on specific false positive instances which will be used to train future, more advanced versions of the system.

5.4. Local Storage—SQLite Dataset

This section details the application’s local storage design, which utilises an SQLite database. This design is fundamental to guaranteeing both operational efficiency and user data privacy by entirely removing any reliance on external cloud services.

Table 3 provides a conceptual overview of the four critical components within this database schema. The following outlines the Data Schema Components.

The component displayed in

Table 3, specifically the sensor data, functions as the primary data source for the LSTM model. It continually logs raw accelerometer readings, where the

X-axis,

Y-axis, and

Z-axis columns record the normalised triaxial acceleration values. Crucially, the magnitude column stores the calculated signal magnitude vector (SMV). This time-series data, specifically the sequence of peak SMV values extracted from the magnitude column, is the direct input used for the on-device LSTM model to learn individual behavioural patterns (as discussed in

Section 4.2). The integrity and volume of this data are essential for effective predictive regression.

The alerts information indicating the log of all real-time notifications is shown in

Table 4. It indicates that the system classification (detailed in

Section 4.2) has triggered an alert.

Each stored record includes details such as the Date/Time of Alert and, most importantly, the Alert Reason. The reasons, such as ‘Fall detected state’ and ‘Unexpected active state,’ are the direct result of the LSTM’s anomaly detection combined with the subsequent heuristic ruleset. This complete log serves as a critical component for system auditing and is essential for verifying the effectiveness of the false positive reduction strategy (as was visually demonstrated in

Figure 11). The Participant Information data shown in

Table 5 indicate the manner of securely storing user-specific demographic data, including the individual’s age, gender, and location. This data is utilised during the initial setup phase and is essential for ensuring that the entire monitoring and alert system is correctly personalized and accurately linked to the unique individual.

The caregiver contact data shown in

Table 6 indicates the manner of storing the designated emergency contacts. This data is essential as it ensures the system can efficiently retrieve necessary details like email and phone number to transmit automated alerts via SMS, email, or push notification in the event of a detected emergency.

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6 provide an overview of the four core components in the SQLite local storage schema. The local storage design enables secure data handling, seamless LSTM processing, responsive real-time monitoring through alert logging and contact retrieval.

6. Discussion and Future Work

There were studies utilisting smartphones for human activity detection (e.g., [

42]). Our study however demonstrated an on-device, LSTM-based application offering a highly effective and practical solution for remote patient monitoring. It successfully addressed the key limitations associated with existing approaches. The quantitative results, particularly the high R

2 score of 0.931 and the low Mean Absolute Error (MAE), confirm the LSTM model’s robust capability to accurately predict movement patterns based on raw accelerometer data. This high predictive accuracy is crucial, as it allows the application to establish a highly reliable baseline of an individual’s normal behaviour.

The most significant contribution of this research is the application’s inherent adaptability, which directly tackles the prevalent issue of false alarms often found in generic AI-based solutions. The “Number of Alerts by Day” chart (

Figure 11) visually confirms that as the LSTM model has learnt each participant’s unique daily routine over a week, the number of alerts progressively decreased. This on-device, personalised learning mitigates the need for large, pre-trained datasets and successfully eliminates the significant privacy risks associated with transmitting sensitive health data to external servers. Furthermore, the application’s reliance on a smartphone’s integrated sensors offers a cost-effective and scalable alternative to expensive, dedicated IoT devices.

The main limitation of the current study was that the evaluations were based on healthy adult volunteers. Patients with diverse medical conditions can have different movement pattens than healthy adults. Brain disorders such as Parkinson’s disease that affect movement can have symptoms such as involuntary shaking, slow movement, and stiff muscles. These can affect the manner in which the application reacts and learns. Therefore, while this study effectively establishes the efficacy of the proposed application, several areas exist for future enhancement of its capabilities and real-world applicability. Firstly, to validate the application’s overall generalizability, future studies should aim to validate it on a substantially larger and more diverse cohort of participants, including individuals with varying health conditions and mobility challenges. Secondly, the application could be enhanced by integrating data from other on-device sensors, such as a gyroscope, to further improve the accuracy of both activity classification and fall detection. Finally, future research could explore advanced machine learning techniques, such as reinforcement learning, to allow the model to learn more effectively from the user’s “I am okay” overrides, which would make the system even more efficient and reduce false alarms more rapidly. It could also concentrate on expanding the model’s capabilities to not only detect anomalies but also to classify a wider spectrum of daily activities, thereby providing a richer, more detailed log for proactive health monitoring. Finally, future studies will implement additional application-level protections, such as data encryption for the local SQLite database, to safeguard stored sensor data against device-level threats.

7. Conclusions

This study successfully developed and rigorously evaluated a novel, on-device remote patient monitoring application that offers a privacy-preserving and highly cost-effective solution specifically tailored for elderly individuals residing alone. By strategically leveraging the readily available, built-in accelerometer of a smartphone, the application eliminated the dependency on costly, dedicated hardware, and external cloud servers. The central and most impactful contribution of this work lie in the application’s innovative use of a personalised Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) model, which is trained exclusively and directly on the individual user’s unique behavioural data.

The experimental results definitively demonstrated the substantial importance of adopting this on-device learning approach. As the LSTM model continuously learned and adapted to the user’s motion patterns across the monitoring period, the number of false alarms, clearly visualized by a progressive decrease in unnecessary alerts sent to caregivers, was significantly mitigated. This critical adaptability enabled the application to reliably distinguish between normal daily routines and genuine, urgent anomalies, such as unexpected falls or extended periods of inactivity. By thoughtfully combining this intelligent, learning-based model with a user-override feature (the “I Am Okay” option), the application provided a notably reliable and trustworthy monitoring solution. Ultimately, this research offers a scalable and practical application that successfully improves patient safety in their home environment while simultaneously upholding their privacy, thereby proving the efficacy and readiness of on-device AI for critical, real-world health monitoring applications.