The two main challenges lie in the scientific computations themselves, particularly regarding memory usage and numerical precision. These difficulties arise from the large number of elements involved in generating each solution field, as well as the increase in computational cost when the mesh is refined and the number of elements grows.

4.2.1. Predefined and Optimized Meshes

Mesh generation is a fundamental step in Finite Element Analysis (FEA), but it often involves complex algorithms, extensive user input, and large data structures. Many existing mesh generators are part of larger software ecosystems that require developers to learn an entire environment, making them difficult to integrate into lightweight or purpose-driven applications—particularly for users who simply need to mesh a domain quickly and efficiently. Moreover, these general-purpose tools are typically designed for desktop computing and are not optimized for smartphones, which are limited in both memory and processing power. This makes their direct integration into mobile applications impractical.

To address these limitations, we propose a simple and efficient solution: a predefined structured mesh specifically tailored for typical bridge geometries. This approach eliminates the need for real-time meshing, significantly reduces code complexity, and remains fully compatible with the computational constraints of mobile devices, all while maintaining acceptable accuracy.

The proposed meshing strategy is algorithmically efficient. It relies on analytical formulations that directly compute node coordinates and element connectivity using closed-form expressions. This avoids the need for recursive subdivision or graph-based searches, which are typical in general-purpose mesh generators. As a result, the algorithm achieves linear computational complexity and very low memory overhead.

The proposed approach consists of two main steps:

Initial Node Placement, using a linear distribution to define the mesh structure.

Fast Mesh Refinement, particularly for triangular meshes (both 3-node and 6-node), in order to obtain accurate and stable results.

This meshing strategy was implemented and tested within the developed mobile FEA application. To validate its performance, the predefined mesh was applied to the analysis of two-dimensional structural domains representing typical bridge configurations. The geometries include rectangular, trapezoidal, and arch-shaped domains, which serve as representative examples to demonstrate the flexibility and robustness of the proposed approach.

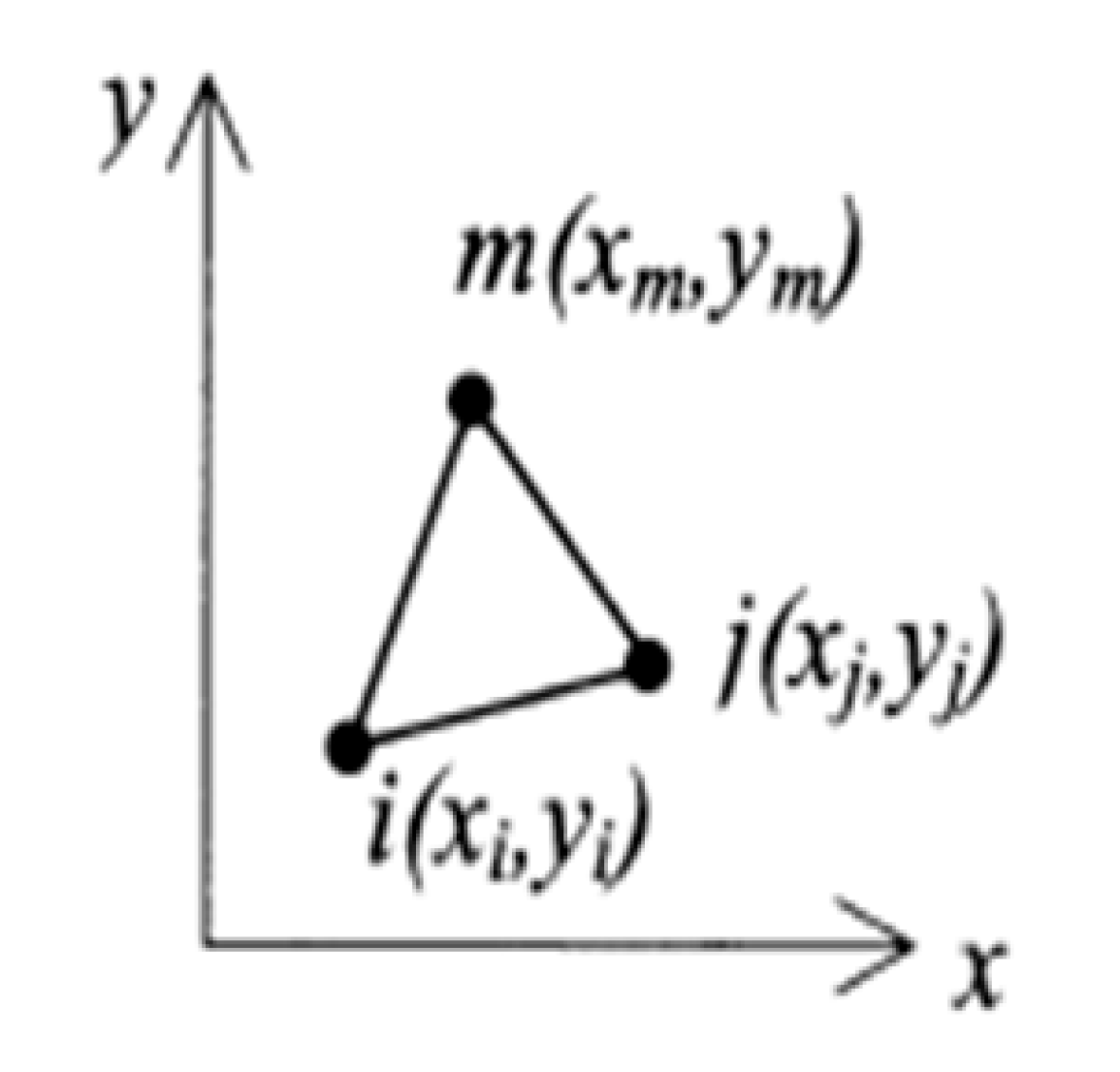

For the rectangular-shaped structure, the algorithm presented below is created to generate a structured triangular mesh for finite element analysis (FEA).

The algorithm outputs a 3-node triangular mesh, the x- and y-coordinates of all nodes, and the total number of nodes and elements.

The inputs consist of the rectangular domain dimensions (width and height) and the number of divisions along the x- and y-directions, which determine the desired level of mesh refinement.

The mesh generation procedure used for the rectangular domain is formalized in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1. Structured Triangular Mesh Generation for a Rectangular Domain. |

Input:

- Domain dimensions (Lx, Ly)

- Number of divisions in x and y directions (Nx, Ny)

- Refinement level (r)

Step 1: Initialize Node Coordinates

For i = 0 to Nx:

For j = 0 to Ny:

x = i * (Lx/Nx)

y = j * (Ly/Ny)

Store (x, y) as node[i][j]

Step 2: Generate Initial Triangular Mesh

For i = 0 to Nx − 1:

For j = 0 to Ny − 1:

Triangle 1: (i, j), (i + 1, j), (i + 1, j + 1)

Triangle 2: (i, j), (i + 1, j + 1), (i, j + 1)

Store both triangles

Step 3: Refine Mesh (Repeat r Times)

For each triangle in mesh:

Compute edge midpoints

Compute triangle centroid

Create 4 new sub-triangles using midpoints and centroid

Replace old triangles with refined ones

Output:

- List of node coordinates

- Connectivity of triangular elements |

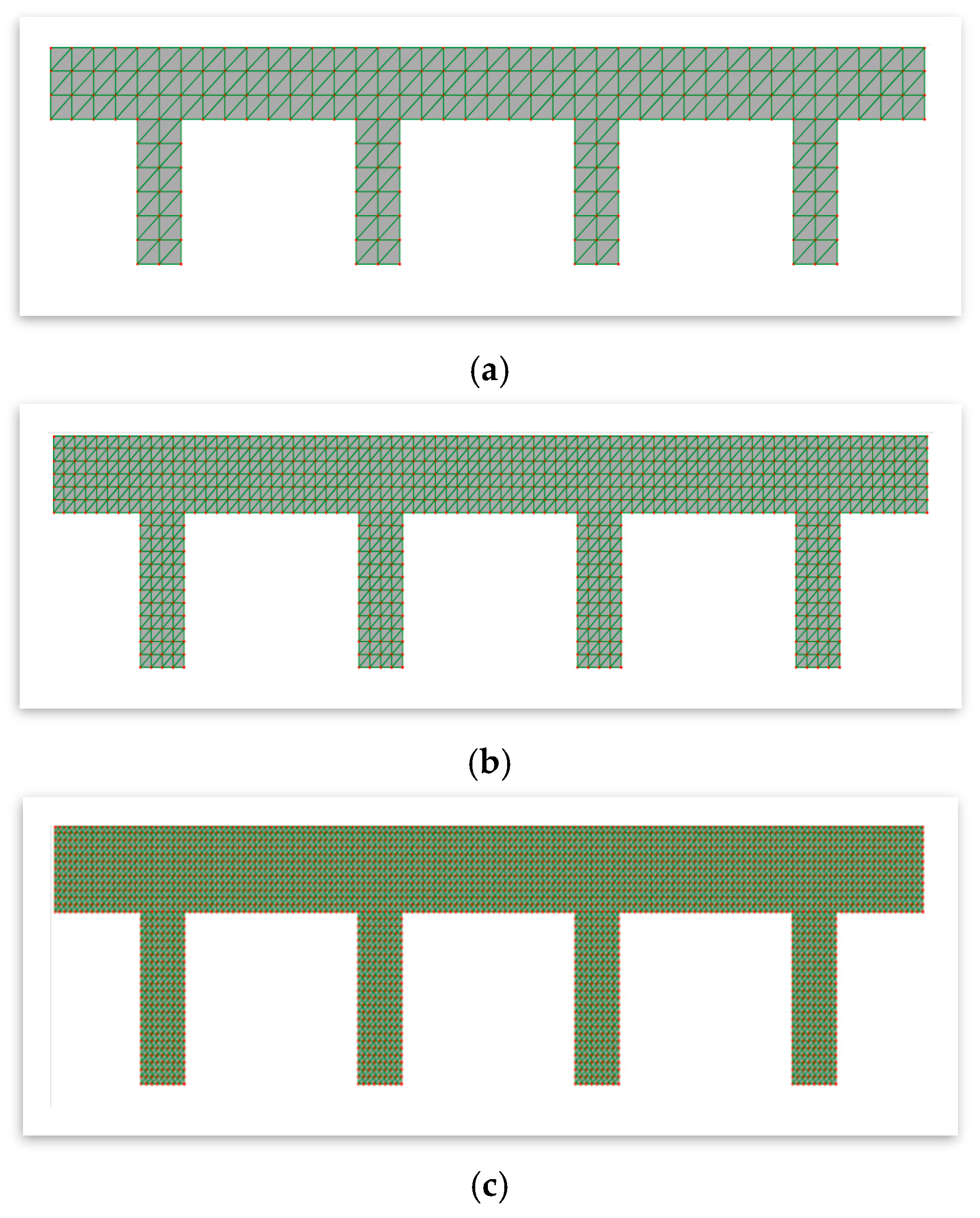

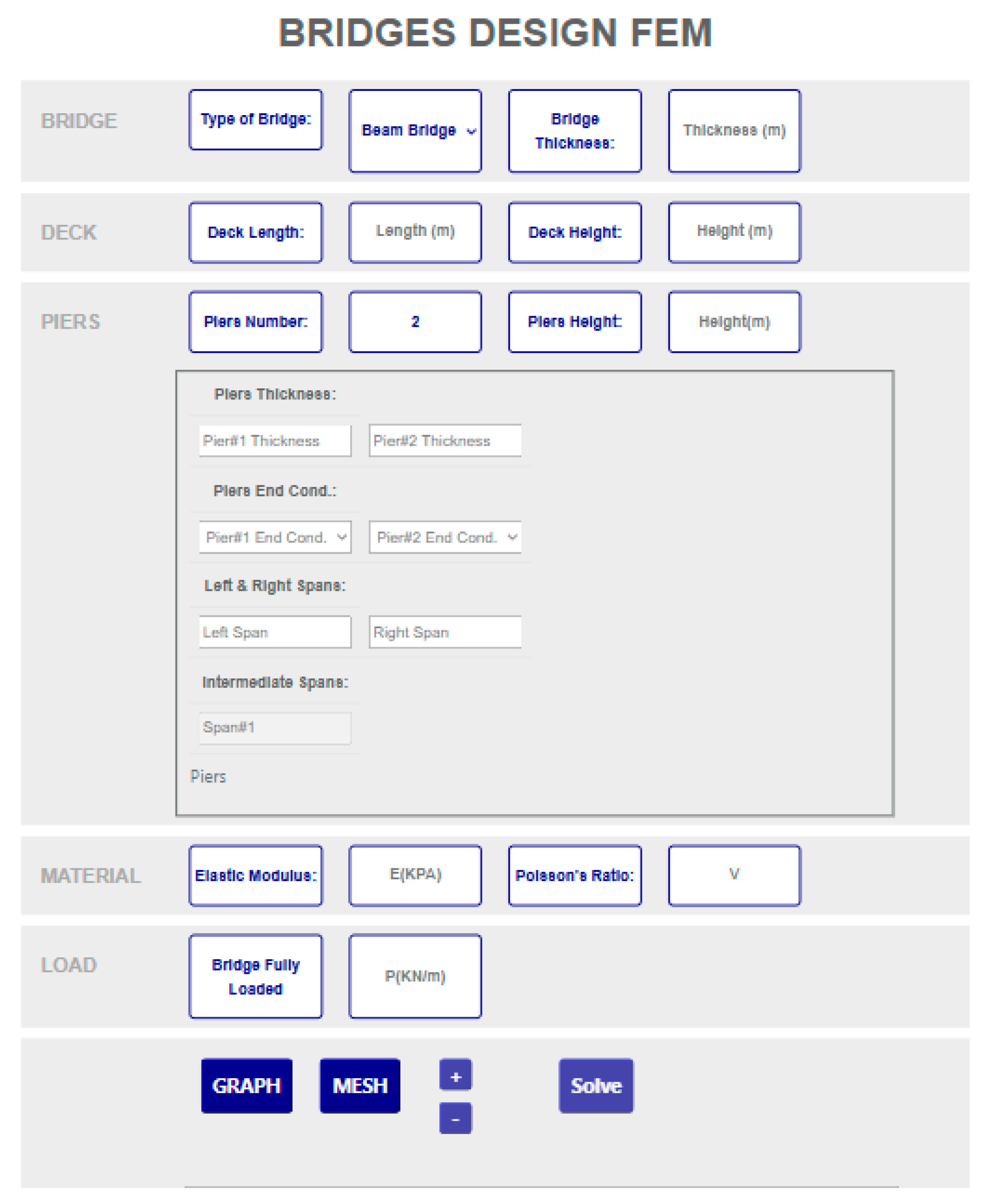

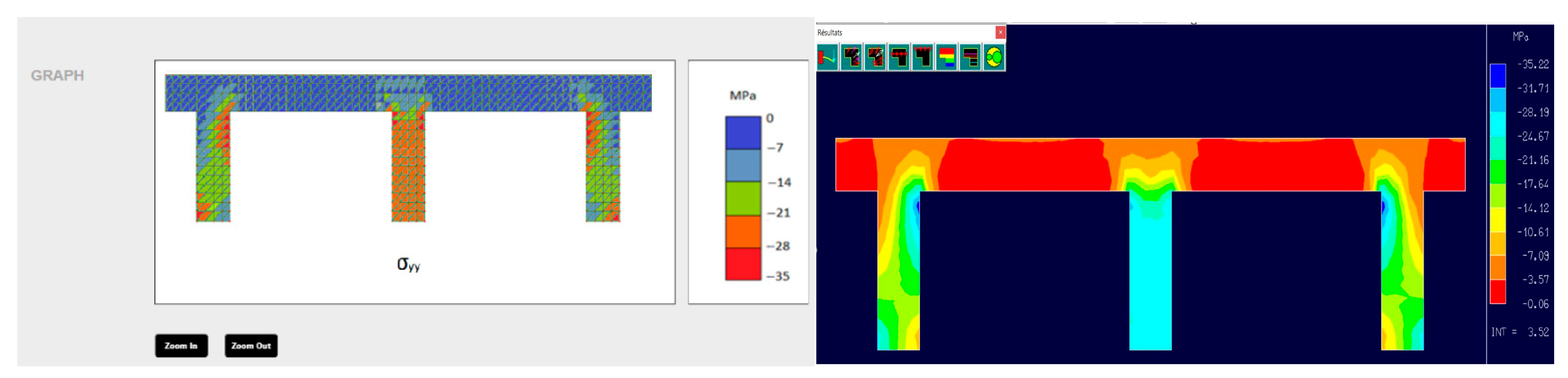

An example of a girder bridge meshed by our application is presented in

Figure 2. The bridge has a total length of 40 m and consists of 4 piers, each 2 m thick and 6 m high. The bridge girder is modeled as a rectangular domain of 40 × 3 m.

Using the mesh generator, the domain is discretized with 40 divisions on the x axis and 3 on y-axis. The number of elements is calculated as:

And the number of Nodes is:

This initial coarse mesh is then refined to generate a finer mesh. The refinement is performed by splitting each triangle into four smaller triangles through edge bisection, allowing for the easy creation of 6-node triangular.

Thus, for the example shown in

Figure 2, refining the girder mesh increases the number of elements from 240 to 960 (

Figure 2b), and then to 3840 elements (

Figure 2c).

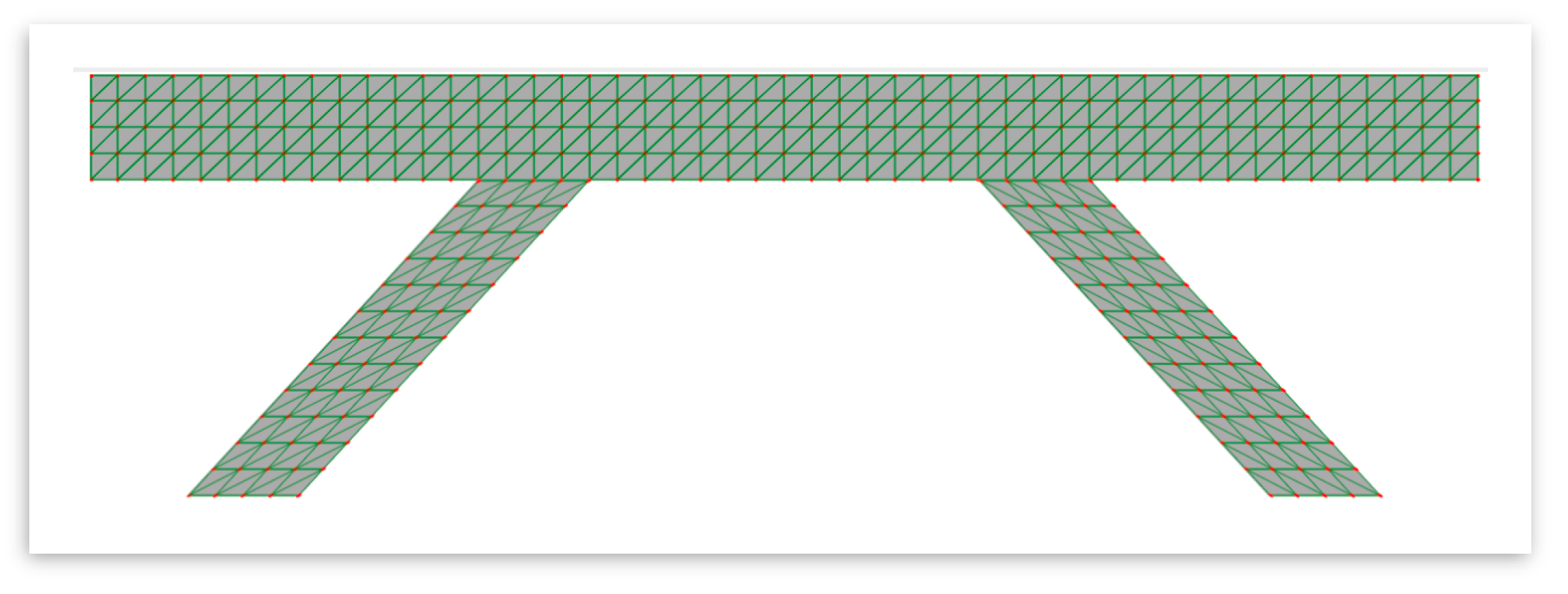

A triangular mesh for the trapezoidal-shaped structure is generated using a geometric transformation matrix. The function

context.setTransform (a, b, c, d, e, f), built into Canvas.js, enables the rectangular domain to be efficiently transformed into a trapezoidal one.

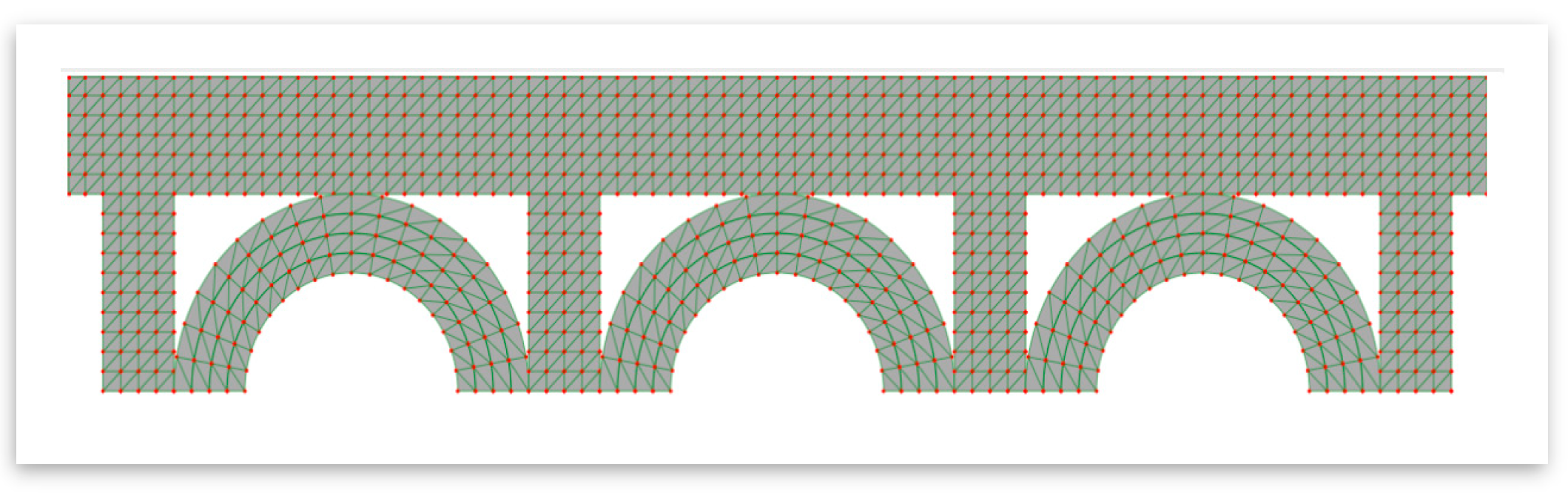

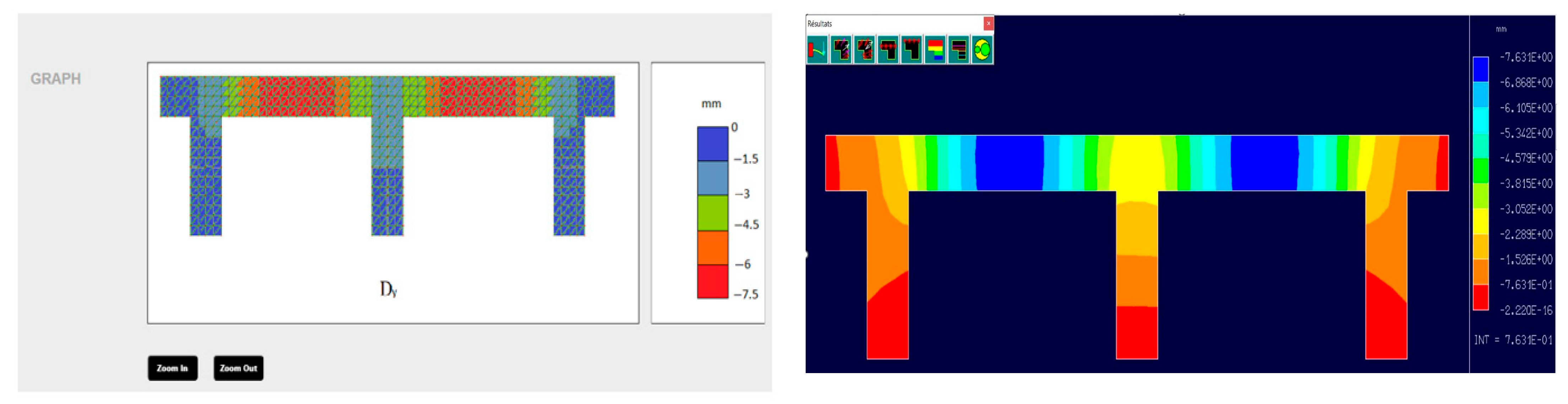

Figure 3 illustrates the resulting mesh for the trapezoidal portion of the crutch bridge. The mesh for arch-shaped structures is created by distributing nodes uniformly along the arc, using polar coordinates. The number of divisions along the arc defines the refinement level.

The complete node-generation procedure for the arch-shaped domain is formal-ized in Algorithm 2.

| Algorithm 2. Node Distribution and Triangular Mesh Generation for Arch-Shaped Domains. |

for (let i = 0; i <= numDivisions; i++) {

const angle = i * angleStep;

const x = centerX + Math.cos(angle) * radius;

const y = centerY + Math.sin(angle) * radius;

drawPoints(x, y);

} |

This results in a clean, efficient triangular mesh for the arch geometry, as illustrated in

Figure 4.

The predefined mesh strategy adopted in this work is intentionally tailored to simple, parameterized bridge geometries (rectangular, trapezoidal, and arch domains), as it ensures predictable memory usage and avoids the computational overhead of general-purpose mesh generators. However, this approach naturally limits geometric flexibility. In future extensions, adaptive refinement schemes could be integrated—for example, refining elements in regions of high stress gradients or near geometric singularities. Additionally, simple element distortion checks, such as minimum angle or Jacobian-based quality criteria, could be incorporated to prevent poorly shaped triangles during refinement. Such mechanisms would enable the predefined meshes to remain lightweight while improving robustness for more complex or irregular geometries.

Computational Efficiency and Memory Cost on Mobile Device

To assess the performance of the predefined mesh generation algorithm, Performance tests were conducted on a Samsung Galaxy A52 ((Snapdragon 720G, 6 GB RAM; manufactured by Samsung in Suwon, South Korea)), a mid-range smartphone chosen to ensure efficiency on resource-limited hardware. This guarantees that performance would further improve on more powerful devices.

Table 1 summarizes the computation time and memory usage for different mesh sizes, ranging from 100 to 5000 triangular elements.

The results demonstrate that the proposed approach maintains both low computational cost and minimal memory usage, even for relatively dense meshes. The memory required to generate 5000 triangular elements does not exceed 1 KB, while the computation time remains below 50 ms, making the meshing process practically instantaneous for the user.

The computational complexity of the algorithm increases approximately linearly with the number of elements (O(n)), confirming its efficiency for real-time applications. Such performance is mainly achieved the fact that both node coordinates and element connectivity are determined using explicit analytical relationships derived from the geometric parameters of the domain. Consequently, the algorithm avoids recursive searches and graph-based data structures typical of generic mesh generators, significantly reducing computational overhead and memory usage. These results confirm that the predefined mesh strategy is well-suited for mobile finite element simulations, ensuring an optimal balance between accuracy, execution time, and resource consumption.

Accuracy Evaluation with Mesh Refinement

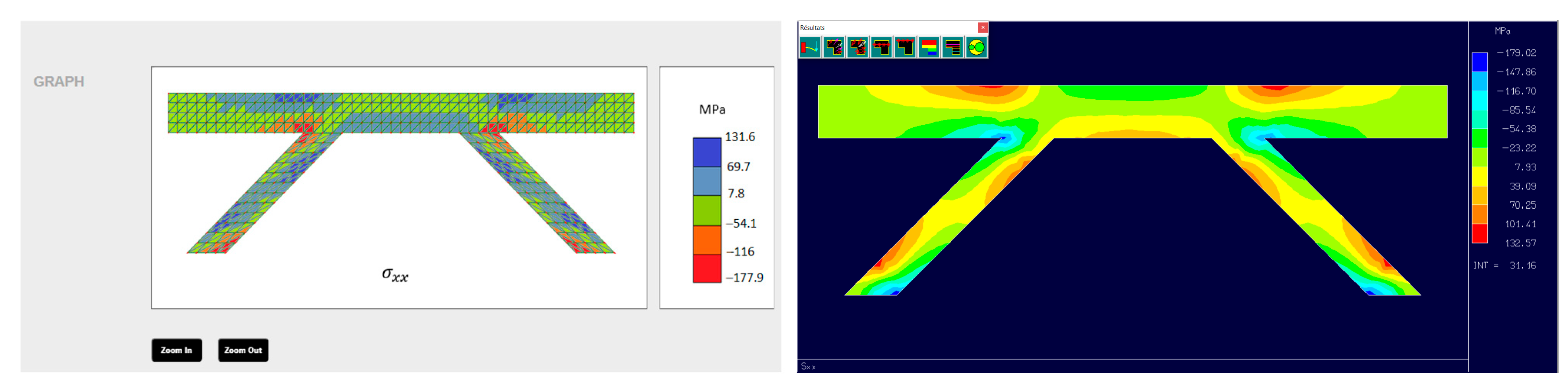

Mesh refinement is a well-established strategy in finite element analysis to improve solution accuracy by reducing discretization error. However, finer meshes also increase the computational load during assembly and solving phases, which is particularly critical on mobile devices where memory and processing power are limited. To quantify the accuracy of the proposed mobile solver, three predefined refinement levels—coarse, medium, and refined—were evaluated on the 2D girder bridge case study shown in

Figure 2. A high-resolution desktop FEM model was generated using RDM6 with a fine mesh to obtain reference displacement and stress fields. For each refinement level in the mobile application, the corresponding maximum vertical displacement and maximum Von Mises stress were extracted and compared to the reference values. All simulations were performed under the same geometric configuration, boundary conditions, loading setup, and homogeneous material properties to ensure that differences in results arise solely from the mesh resolution. The percentage error was computed using the standard relative deviation formula:

Table 2 summarizes the error evolution with respect to the number of elements.

As expected from classical finite element theory, increasing mesh density consistently reduces discretization error. The results show that the error decreases systematically with refinement, from approximately 2–3% for the coarse mesh to below 1% for the refined mesh. This quantitative evaluation confirms that the proposed predefined mesh strategy achieves acceptable accuracy while respecting the memory–time constraints of mobile devices.

4.2.2. Efficient Solvers for Linear Systems in Mobile FEA Applications

One of the most computationally intensive phases in the Finite Element Analysis (FEA) process is the resolution of the global linear system of equations, typically expressed as [K]{U} = {F}, where [K] is the global stiffness matrix, {U} is the unknown nodal displacement vector, and {F} is the global force vector. For large meshes with a high number of elements, the resulting system becomes very large and sparse, making direct solvers (based on matrix inversion or factorization) impractical for mobile devices due to their limited memory and processing power. To address this challenge, the proposed application implements and compares several iterative solvers, which are more suitable for constrained environments. Each solver is evaluated based on computation time, memory usage, and solution accuracy. By conducting a series of benchmark tests on representative structural problems, the performance of these algorithms is compared to identify the most efficient and reliable approach for mobile FEA. The goal is to achieve an optimal balance between speed, resource efficiency, and precision, making it feasible to run real-time structural simulations on smartphones and tablets.

Solution Methods

In structural analysis using the Finite Element Method, the resulting global stiffness matrix is typically symmetric, sparse, and positive-definite. These properties allow for the use of specialized iterative solvers that are optimized for such matrix types. To address the computational limitations of mobile platforms, we conducted a focused review of the literature and selected several iterative methods that are known to be efficient for solving this class of linear systems.

The methods implemented and evaluated in our study include: the Conjugate Gradient (CG) method, the Preconditioned Conjugate Gradient (PCG) method with LLt incomplete factorization, the Gauss-Seidel method, a modified version of Gauss-Seidel known as the One-Dimensional Double Successive Projection Method (1D-DSPM), the Two-Dimensional Double Successive Projection Method (2D-DSPM), the Minimum Residual Method (MINRES), and the Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno (BFGS) method. These methods were chosen based on their mathematical suitability for sparse and symmetric positive-definite matrices, and their performance as reported in the literature. Each algorithm is briefly described and referenced in the following section.

- A.

Conjugate Gradient Method (CG)

The conjugate gradient method derives its name from the fact that it generates a sequence of conjugate (or orthogonal) vectors. The conjugate gradient method (CG) [

23] is an iterative method which can be used to solve matrix equations while its coefficient matrix is symmetric and positive definite, since storage for only a limited number of vectors is required [

24,

25]. CG method has been the subject of considerable interest in recent years because of its efficiency and ability to solve difficult problems. The conjugate gradient method is summarized in Algorithm 3.

| Algorithm 3. Conjugate Gradient Method for Symmetric Positive Definite Systems. |

if

|

where A is a symmetric positive definite matrix, b is the nodal force vector,

is the initial value of the solution vector to be determined,

is the initial value of the residual vector, ε is a tolerance, and

is gradient vectors set, in which arbitrary two vectors are conjugate to each other. It can be noticed that one multiplication of matrix and vector and two vectors inner productions requires to be computed during each iterative procedure in CG algorithm.

- B.

Preconditioned conjugate gradient (PCG)

The conjugate gradient algorithm is a widely recognized iterative method for solving sparse, symmetric, and positive definite linear systems. However, as an iterative solver, it is known for its lack of robustness. This drawback can be improved by using preconditioning.

Consider a linear system Ax = b, where A is symmetric and positive definite. It is assumed that a preconditioner M is available and also Symmetric Positive Definite.

A mathematically equal preconditioned system is obtained as follows:

where M =

and L is the lower triangular matrix. The looking-left column-by-column incomplete factorization procedure is applied and details in [

26,

27,

28].

Replacing the usual Euclidean inner product in the Conjugate Gradient algorithm by the M-inner product, the resulting preconditioned Conjugate Gradient method is obtained, as presented in Algorithm 4 [

29]:

| Algorithm 4. Preconditioned Conjugate Gradient Method. |

if

|

Compared with CG, PCG demands an additional linear system solution during each iteration, and additional memory for storage of the preconditioner while converging faster.

- C.

Gauss Seidel Method

The Gauss–Seidel (GS) method is one of the most commonly used iterative techniques for solving large linear systems. It is well established that GS converges for linear systems with a symmetric positive-definite matrix [

29]. The iterative scheme of the GS solver can be written as follows:

The Gauss–Seidel iterative method is summarized in Algorithm 5.

| Algorithm 5. Gauss–Seidel Iterative Method. |

|

This method updates each unknown using the most recently computed values, which enhances convergence compared to methods that rely solely on previous iterations. Unlike the Jacobi method—where two full sets of unknowns must be stored, the Gauss–Seidel method requires storing only a single set of unknowns throughout the iterative procedure.

- D.

One-dimensional double successive projection method (1D-DSPM) Modified Guass Siedel Method

Ujević [

30] introduced a new iterative method for solving linear systems, which can be interpreted as a modification of the classical Gauss–Seidel scheme. In this approach, two components of the approximation vector xk are updated simultaneously at each iteration. Numerical results show that the modified method can converge up to twice as fast as the standard Gauss–Seidel method and provides a more significant reduction in the error.

The formulation of this modified Gauss–Seidel procedure is summarized in Algorithm 6. For a detailed derivation and further theoretical background, the reader is referred to [

30].

| Algorithm 6. One-Dimensional Double Successive Projection Method (1D-DSPM). |

where

|

- E.

Two-dimensional double successive projection method (2D-DSPM)

Following Ujević’s modification of the Gauss–Seidel method [

30], Jing and Huang [

31] introduced an algorithm based on the Two-Dimensional Double Successive Projection Method (2D-DSPM). This algorithm significantly enhances performance by incorporating projection-space adjustment strategies along with a two-step correction procedure [

32].

This method has been tested on symmetric sparse matrices and has outperformed both Gauss-Seidel (GS) and Modified Gauss-Seidel (MGS) achieving faster convergence and improved computational efficiency [

31,

32]. The DSPM method can be expressed in the following iterative form:

Here,

The Minimal Residual Method (MINRES) is a Krylov subspace method for the iterative solution of symmetric linear equation systems. It was proposed by Paige and Saunders in 1975 [

16]. Even when A is positive definite, MINRES has been shown to possess several advantageous properties that allow it to be considered a strong alternative to the widely used Conjugate Gradient (CG) method [

33,

34]. MINRES minimizes the 2-norm of the residual over Krylov subspaces of increasing dimension, rather than minimizing the A-norm of the error as in CG. Additional details can be found in the original work [

16] and in standard references [

33].

In this study, we use the following MINRES algorithm (Algorithm 7) derived from the MINRES method, which has been demonstrated to be particularly effective for symmetric positive-definite (SPD) matrices [

16,

33].

| Algorithm 7. Minimal Residual Method (MINRES). |

|

- G.

BFGS (Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno)

The BFGS algorithm (Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno) is an optimization method used to find the minimum of a differentiable function. It is a quasi-Newton method that approximates the Hessian matrix to find the minimum of a function [

35]. The algorithm iteratively updates an approximation of the inverse Hessian matrix, making it efficient for solving problems with a large number of variables. The BFGS optimization procedure is summarized in Algorithm 8.

| Algorithm 8. BFGS (Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno) Algorithm. |

Initial inverse Hessian approximation (identity matrix)

); Perform line search with wolf conditions to find

|

Update inverse Hessian approximation:

Numerical Experiments and Results

To evaluate the performance of the seven implemented iterative solvers, we conducted a series of numerical experiments by solving linear systems of increasing size, generated by our finite element mobile application. Each solver was implemented in JavaScript with optimized memory usage strategies, tailored for the constraints of mobile environments.

The experiments were carried out on a Samsung Galaxy A52, a widely available mid-range smartphone featuring a Qualcomm Snapdragon 720G processor (Octa-core CPU), 6 GB RAM, and an Adreno 618 GPU. By selecting a non-high-end device, we aimed to ensure that the application remains functional and efficient even on resource-constrained hardware. This also means that its performance will scale favorably on more advanced smartphones.

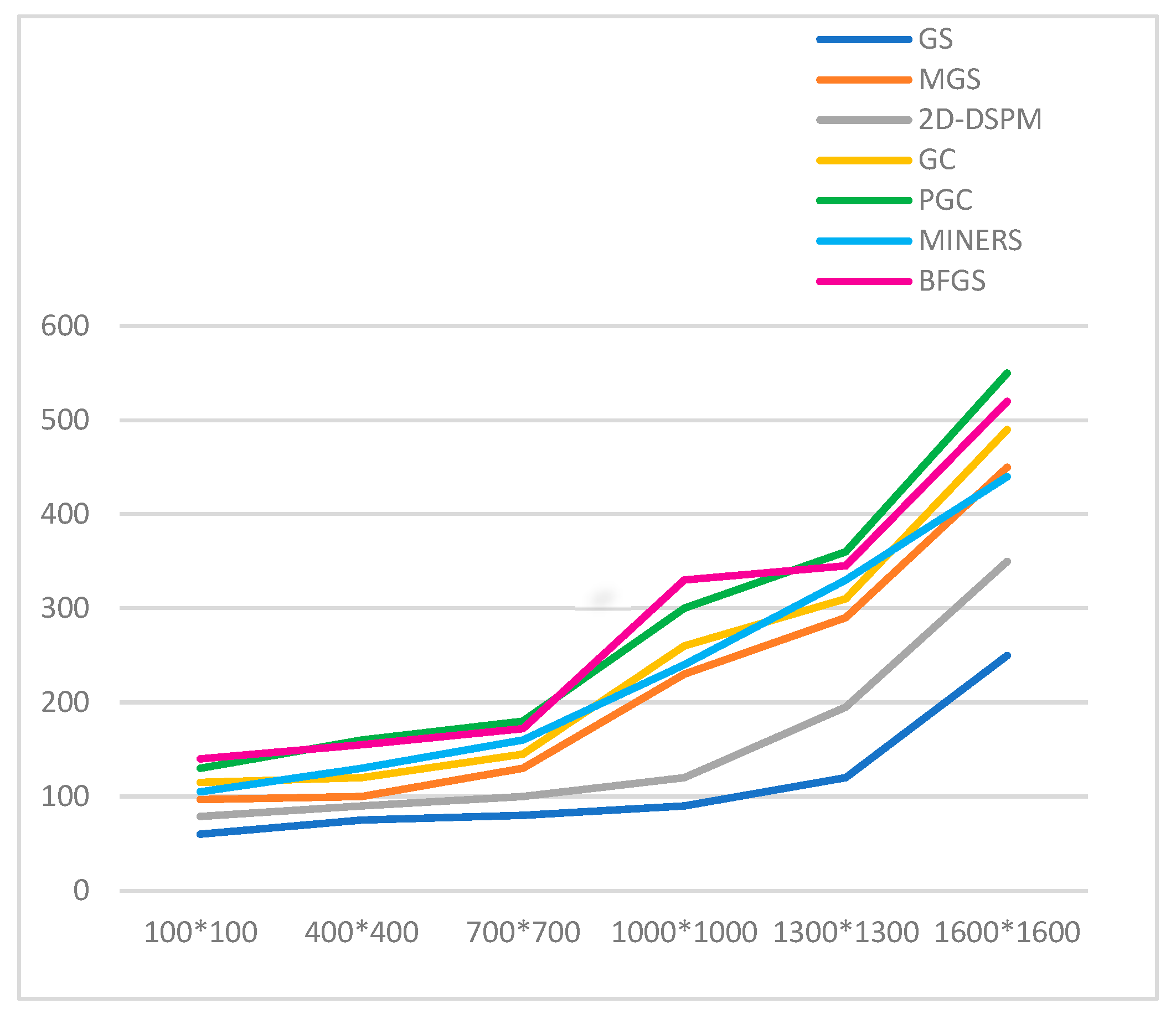

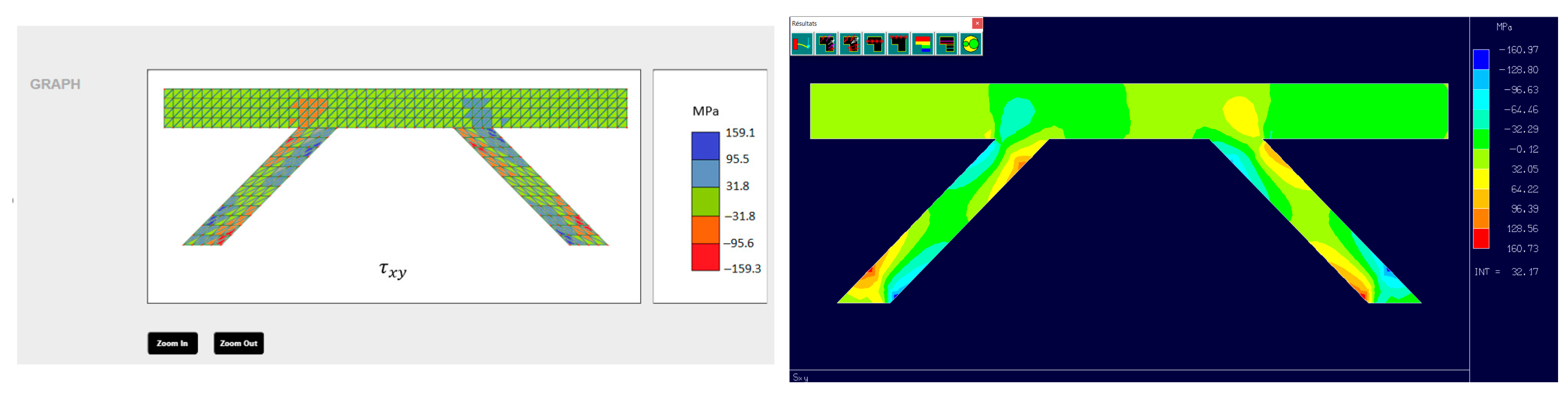

Figure 5 presents the execution time (in seconds) required by seven iterative methods to solve matrices of increasing size, each over a fixed number of 3000 iterations. As expected, execution time increases with matrix size for all methods due to the larger number of unknowns and increased computational workload. Among the tested algorithms, the Gauss-Seidel (GS) method consistently shows the lowest execution time across all matrix sizes, making it the most time-efficient in this fixed-iteration context. However, this does not necessarily imply better convergence or accuracy.

The 2D-DSPM method also demonstrates strong performance, especially for larger matrices, with a moderate and steady increase in computation time, reflecting its efficient iteration strategy.

In contrast, GC, PGC, MINRES, MGS, and BFGS form a group with noticeably higher execution times, particularly beyond matrix sizes of 1000 × 1000. Among these, BFGS and PGC exhibit the highest time costs for the largest matrices (e.g., 1600 × 1600), suggesting greater computational overhead.

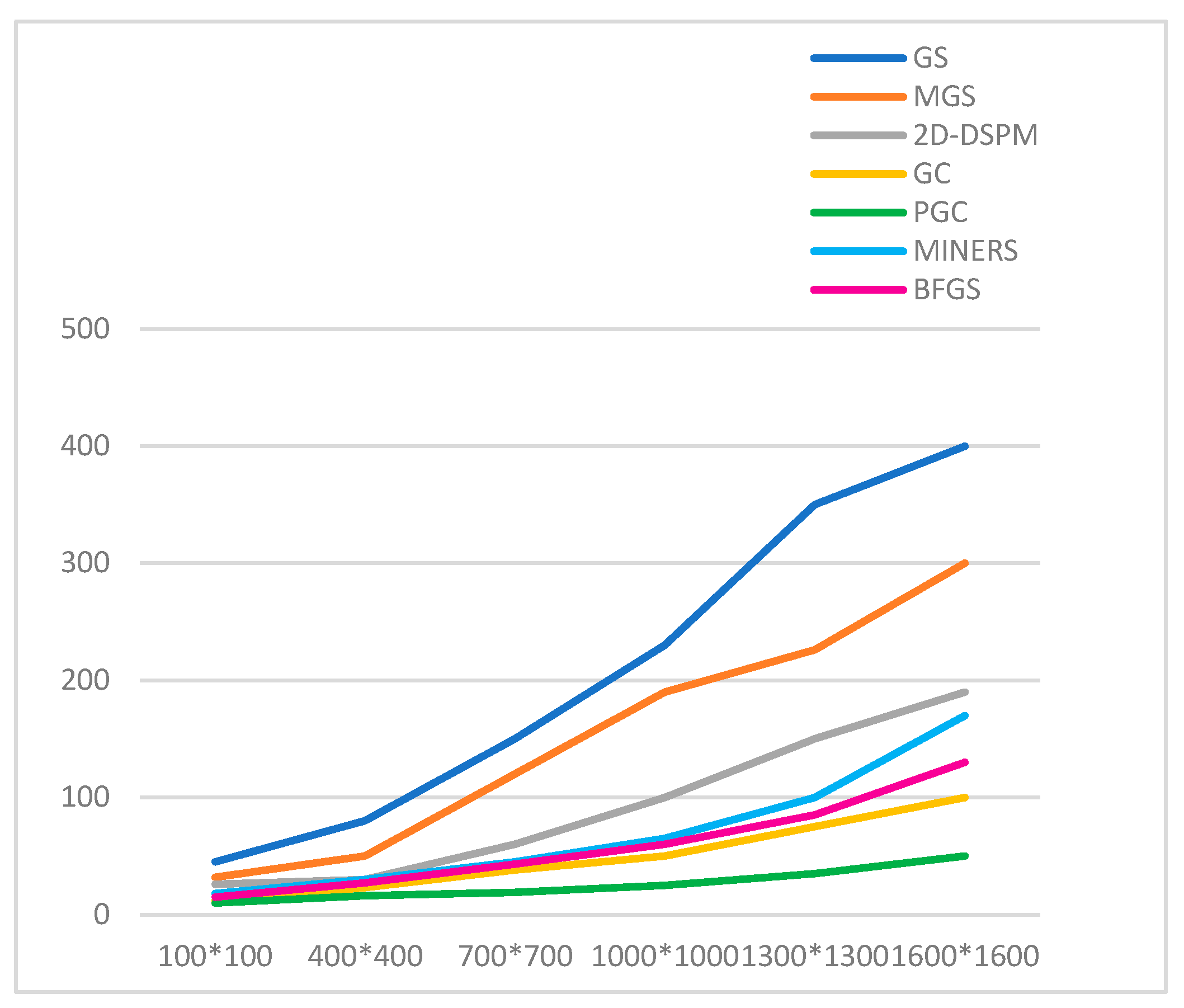

In the following tolerance-based experiments (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7), all iterative solvers use a relative residual tolerance of

(0.01%). This value is particularly suitable for symmetric, well-conditioned structural stiffness matrices, which characterize the 2D linear-elastic bridge problems studied in this work. It also provides an effective balance between numerical accuracy and execution time on resource-constrained mobile devices. In classical FEM workflows, convergence thresholds in the range of

to

are commonly used for smoother-type algorithms, preconditioning stages, or low-memory iterative solvers [

29,

36,

37]. These values are also consistent with the relaxed convergence criteria recommended by commercial FEM solvers when hardware and memory limitations are present. By selecting a tolerance of

, the mobile solver remains aligned with standard FEM practices while enabling real-time execution on mid-range smartphone.

Figure 6 illustrates the average execution times over fifteen simulations of the seven iterative solvers for solving matrices of increasing size, where the stopping criterion is defined by a convergence tolerance of 0.01% as mentioned above. This differs from the previous scenario, which used a fixed number of iterations. Unlike the previous scenario with a fixed number of iterations, this setup allows each method to stop once the desired accuracy is achieved, offering a more realistic comparison of practical efficiency.

The performance varies significantly across the methods, with the Gauss-Seidel (GS) and Modified Gauss-Seidel (MGS) methods demonstrating the longest execution times, especially as the matrix size grows. This trend indicates poor scalability and efficiency in large systems.

The 2D-DSPM and MINERS method shows moderate execution time, outperforming GS and MGS but remaining slower than others methods. In contrast, methods such as GC, BFGS, and especially PGC show superior performance, consistently achieving lower execution times—even for the largest tested matrix (1600 × 1600), with PGC emerging as the fastest method overall.

This suggests that these solvers are more robust and better suited for mobile environments where processing power and memory are limited.

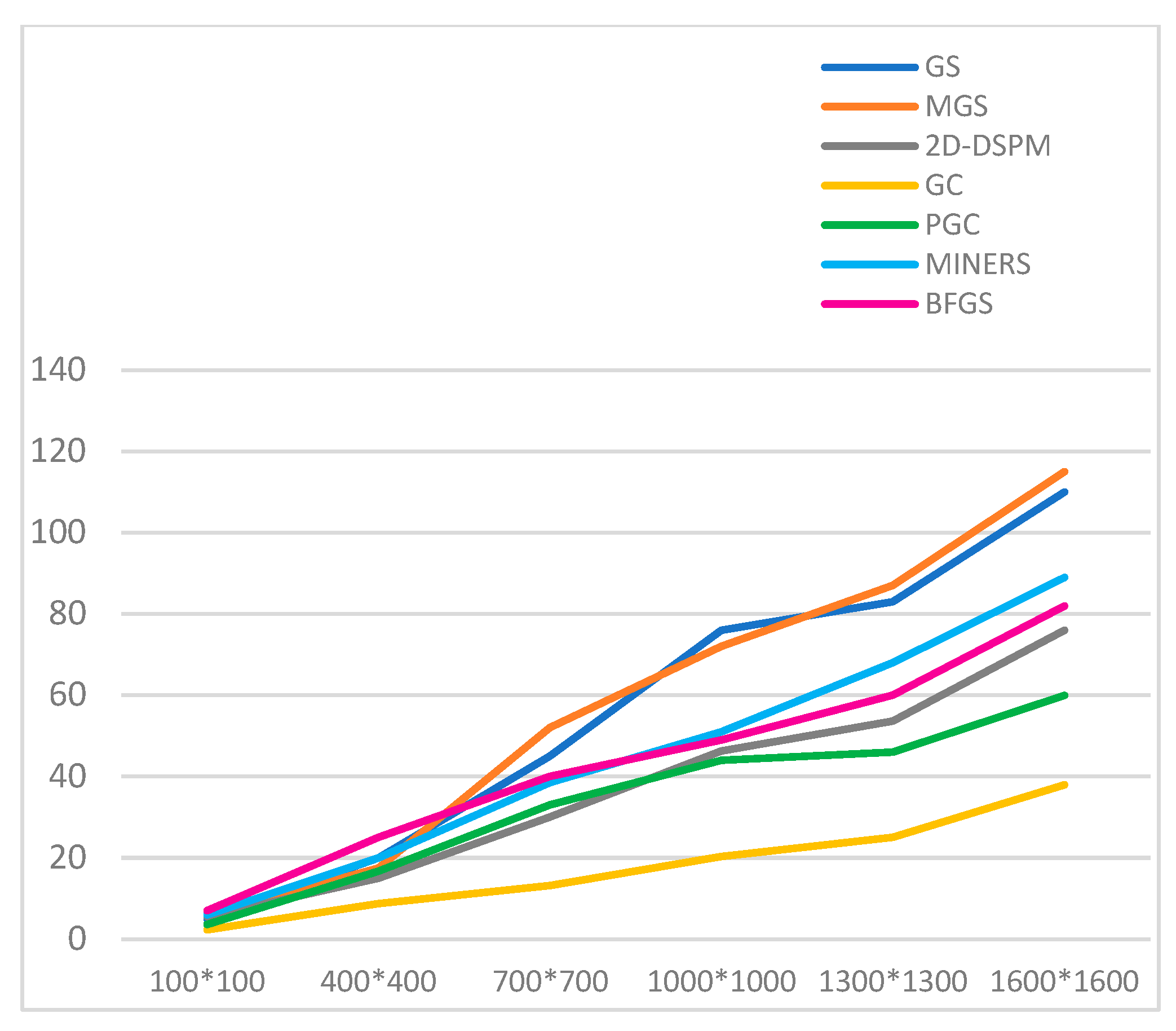

Memory consumption for completing simulations under the same error threshold (0.01%) is shown in

Figure 7 for all methods. The Gauss-Seidel (GS) and Modified Gauss-Seidel (MGS) methods exhibit the highest memory usage, which may limit their practicality for larger problems on resource-constrained mobile devices.

At the opposite end, the Conjugate Gradient (GC) method demonstrates remarkably low memory consumption, remaining the most efficient across all matrix sizes. This highlights its suitability for low-memory environments, such as mid-range smartphones. The Preconditioned Conjugate Gradient (PCG) method, while not the most memory-efficient, maintains a relatively stable memory footprint, making it a balanced choice when both execution speed and memory usage are considered.

Convergence Behavior

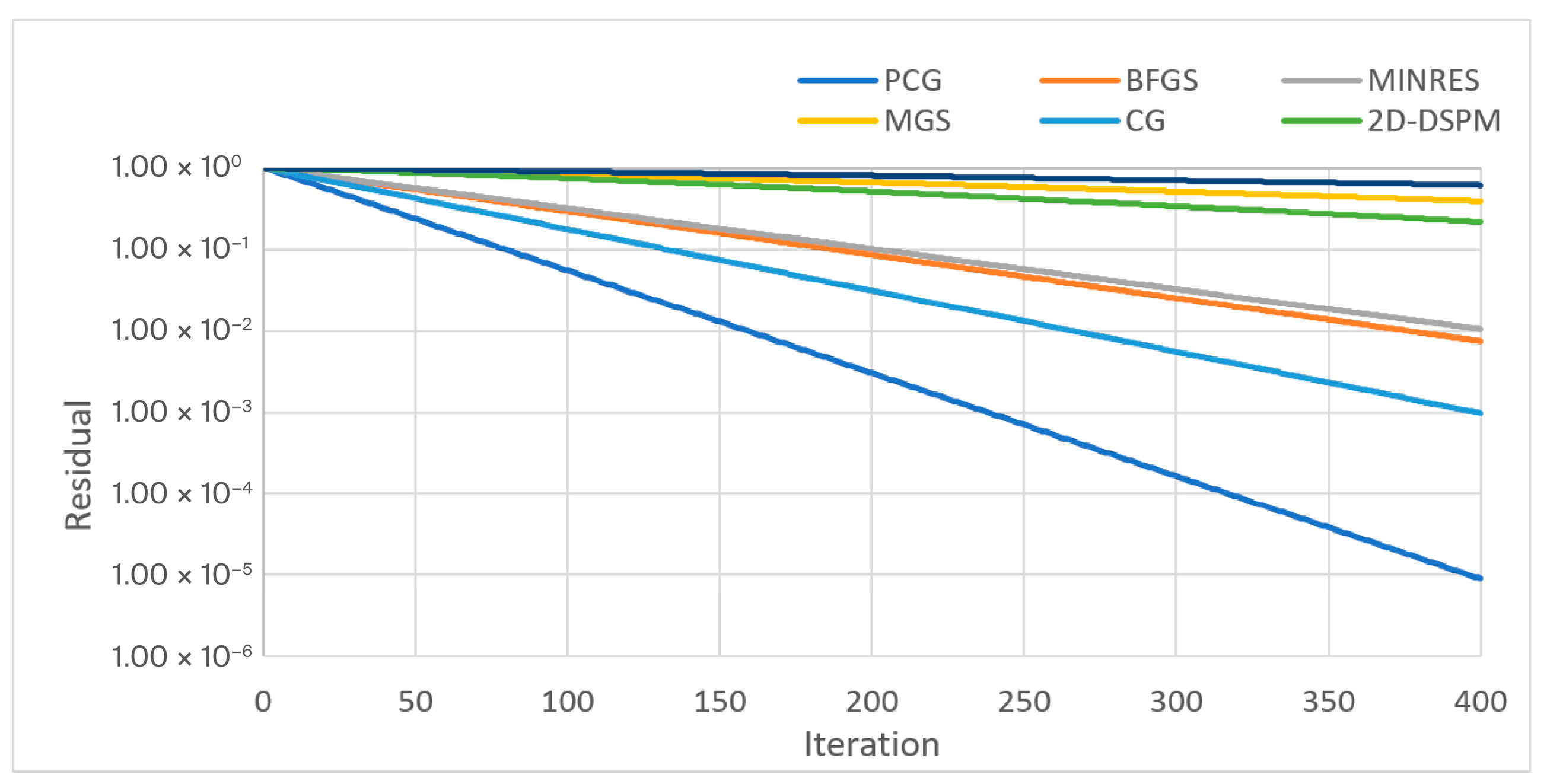

To further strengthen the comparative analysis, we additionally examined the convergence behavior of the iterative solvers.

Figure 8 illustrates the evolution of the residual norm as a function of the iteration count for a representative matrix of size 700 × 700. The x-axis is shown on a linear scale, whereas the y-axis uses a logarithmic scale.

The results show that the Krylov-based solvers (CG, PCG) converge rapidly and monotonically, while GS, MGS, and 2D-DSPM require significantly more iterations to reach the same tolerance. This behavior is fully consistent with the execution-time experiments and explains why CG and PCG deliver the best performance under a fixed accuracy threshold.

Discussion

The evaluation of seven iterative solvers under various matrix sizes and stopping criteria reveals that the most suitable method for mobile finite element applications depends on the balance between accuracy, memory usage, and execution time. In our context, where precision is essential and hardware limitations impose strict constraints—particularly on memory—priority is given first to memory efficiency, followed by computational speed.

Our results show that the Conjugate Gradient (CG) method offers the best compromise across these criteria. It maintains consistently low memory consumption across all matrix sizes, which is critical for deployment on mid-range mobile devices. Additionally, it achieves competitive execution times while still satisfying a fixed convergence threshold, making it both practical and robust for real-world mobile applications.

While methods such as PCG and BFGS demonstrate strong speed performance, their higher memory demands reduce their suitability for memory-limited devices. On the other hand, although GS and MGS are simple and initially fast under fixed iterations, they perform poorly in precision-based scenarios and exhibit high memory consumption.

In conclusion, the CG method emerges as the most balanced and scalable choice, offering a favorable trade-off between memory usage and computational efficiency, without compromising accuracy—aligning closely with the priorities of finite element analysis on mobile platforms.