Abstract

This study investigates the utilisation of AI tools, including Grammarly Free, QuillBot Free, Canva Free Individual, and others, to enhance learning outcomes for 180 s-year telecommunications engineering students at Universidad Politécnica de Madrid. This research incorporates teaching methods like problem-based learning, experiential learning, task-based learning, and content–language integrated learning, with English as the medium of instruction. These tools were strategically used to enhance language skills, foster computational thinking, and promote critical problem-solving. A control group comprising 120 students who did not receive AI support was included in the study for comparative analysis. The control group’s role was essential in evaluating the impact of AI tools on learning outcomes by providing a baseline for comparison. The results indicated that the pilot group, utilising AI tools, demonstrated superior performance compared to the control group in listening comprehension (98.79% vs. 90.22%) and conceptual understanding (95.82% vs. 84.23%). These findings underscore the significance of these skills in enhancing communication and problem-solving abilities within the field of engineering. The assessment of the pilot course’s forum revealed a progression from initially error-prone and brief responses to refined, evidence-based reflections in participants. This evolution in responses significantly contributed to the high success rate of 87% in conducting complex contextual analyses by pilot course participants. Subsequent to these results, a project for educational innovation aims to implement the AI-PBL-CLIL model at Universidad Politécnica de Madrid from 2025 to 2026. Future research should look into adaptive AI systems for personalised learning and study the long-term effects of AI integration in higher education. Furthermore, collaborating with industry partners can significantly enhance the practical application of AI-based methods in engineering education. These strategies facilitate benchmarking against international standards, provide structured support for skill development, and ensure the sustained retention of professional competencies, ultimately elevating the international recognition of Spain’s engineering education.

1. Introduction

The rapid evolution of engineering professions demands a blend of technical expertise and soft skills, yet studies consistently highlight deficiencies in communication, critical thinking, and problem-solving among engineering graduates [1,2]. These skills, essential for academic success and career readiness, are often undertaught in traditional engineering curricula, which prioritise technical proficiency over abstract reasoning and adaptability [3]. For instance, surveys of engineering employers indicate that ineffective communication, such as the inability to collaborate in team projects, and limited creative problem-solving skills, demonstrated by a lack of innovative solutions in real-world challenges, hinder graduates’ employability [4,5]. This gap is particularly pronounced in handling hypothetical or unstructured scenarios, where students often seek rote solutions or virtual assistance rather than developing autonomous, innovative approaches [6]. Moreover, evidence suggests that neglecting soft skills and focusing on technical education may impede cognitive development and neural plasticity, limiting students’ ability to navigate complex professional environments [7,8].

In response to these challenges, engineering education is increasingly adopting innovative pedagogical approaches, active methodologies, listed in the following lines. Problem-Based Learning (PBL) enhances critical thinking and problem-solving skills by immersing students in authentic, real-life problems, encouraging them to analyse, strategise, and collaborate to find solutions [1,9]. Experiential-Based Learning (EBL) boosts motivation and active participation by immersing students in hands-on experiences, equipping them with the skills and confidence needed for real-world challenges [9]. Task-Based Learning (TBL) cultivates resilience, facilitates stress management, and nurtures self-reliance by encouraging students to independently tackle unexpected assignments, fostering adaptability and confidence [5]. PBL fosters higher-order thinking skills (HOTs), autonomy, and creative problem-solving by engaging students in open-ended challenges [9,10]. EBL, through real-world or simulated scenarios, enhances motivation and cognitive engagement, preparing students for professional contexts [11]. TBL promotes resilience and stress management by encouraging students to address unexpected tasks independently [12]. The methodologies of Problem-Based Learning (PBL), Experiential-Based Learning (EBL), and Task-Based Learning (TBL) are tailored to meet the criteria of international organizations and top engineering firms, which prioritise candidates exhibiting exceptional communication skills, emotional intelligence, and adaptability [7].

An important development in current teaching methods is combining Information and Communication Technology (ICT) and Artificial Intelligence (AI), which are changing how engineering education is approached [13,14]. AI-powered tools like smart tutoring systems and automated feedback processes improve logical thinking, motivation, and problem-solving skills [15,16]. In professional settings, AI is becoming indispensable, with applications in data analysis, decision-making, and process optimisation, making its inclusion in education essential for career preparedness [17]. However, there are ongoing debates about the ideal integration of AI in education, with some experts arguing for a balanced approach that combines AI tools with traditional teaching methods, while others advocate for a more technology-centric educational system. Some studies warn against excessive dependence on technology over essential human skills [18], while others see AI as a driver for personalised learning and skill enhancement [19]. This study introduces a pilot course designed for 180 s-year Spanish telecommunication engineering students.

The course combines Problem-Based Learning (PBL), Experience-Based Learning (EBL), and Team-Based Learning (TBL) with Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Information and Communication Technology (ICT) to address the soft skills gap. The course utilises AI-driven simulations, such as virtual business challenges and entrepreneurial simulations, along with feedback systems to create realistic scenarios that enhance students’ communication, critical thinking, and adaptability skills. The main goal is to assess how well this AI-enhanced teaching method enhances students’ soft skills such as communication, critical thinking, and adaptability, as well as their career readiness in terms of industry-specific skills and professional development. Preliminary findings indicate notable enhancements in students’ communication fluency, abstract reasoning abilities, and stress management skills. These findings present a model that can be expanded and adapted for engineering education, highlighting the potential impact on students’ soft skills development [4]. This work contributes to the expanding field of AI in education by analysing how AI algorithms can enhance hands-on learning experiences, thereby aligning academic preparation with industry requirements and contributing to foster a more seamless transition for students into professional settings.

1.1. Specific Terminology Used in This Paper

To better understand the content and analysis provided in the following paper, some terms and tools have been defined below so that their particular use within the research could be better understood:

Critical thinking: This paper analyses this skill as an individual’s capability of analysing, evaluating and judging information. Alongside other thinking approaches such as Creative thinking, Deep Thinking and Computational thinking, the perspective from which this skill is approached is that of going beyond abstract thinking—as supposedly acquired during youth—and enabling students to create, promote problem solving skills and in-depth comprehension [7,20].

Real-world challenges: Also called authentic or real-life, the term refers to mock-up situations which mimic problems and challenges found in telecommunication contexts to better prepare students for their professional lives.

Soft skills: communication, personal, interpersonal, cultural, thinking, leadership, creative and problem-solving skills [20].

Cognitive development: This focuses on an individual’s capability of communicating and thinking critically added to reflective and deep thinking skills [1,7].

Neural plasticity: This refers to the brain’s capability of storing words, meanings and contexts, making connections with new information and prompting individuals learning-acquisition processes [7,21].

Active methodologies: These are innovative instruction approaches having students as the centre of the learning acquisition process, fostering critical thinking, problem-solving and creative skills in authentic contexts [9,21].

Higher Order Thinking Skills (HOTs): According to Bloom’s taxonomy, this refers to individual’s ability to create, evaluate and analyse information [7,9].

Emotional intelligence: This combines assertiveness and empathy, helps individuals to handle oneself and others’ emotions to ensure harmonious coexistence [21] (emotional intelligence).

Social constructivist theory: This theory emphasises that knowledge, acquisition and learning occur in social, cultural contexts [1,7].

Overleaf: This is an online application which enables the use of LATEX text edition standard, which is recognised internationally as an open-source software providing book, article, journal and scientific paper accurate design [7,11].

SCRUM: This is an agile management methodology aimed at making an efficient use of time, ensuring goals’ completion through sprints or periodic deadlines [11].

Universal Design for Learning (UDL): This aims at scaffolding learning to ensure it is accessible to everybody, fostering diversity, inclusiveness and tolerance [21].

MOOC: This is a massive open online course designed by a university with modules that provide instruction for students and professors [11,20].

Trello: This is an online application used to apply SCRUM methodology [11,20].

1.2. List of AI Tools Used in This Paper

Generative AI: These were used as proofreaders and content generators (contrasted with human output): ChatGPT (GPT-4o mini), DeepSeek (DeepSeek-V3.2-Exp), Grok 3, Gemini 2.5 and Copilot X.

AI for presentation and figure/graph design: Gamma AI and Canva AI. Gamma provides support in designing professional presentations based on a given content, while Canva adds other facilities such as mindmap, flow chart and diagram design, poster and infographics design as well as video design.

AI and social media—Lumen5 AI and BufferAI Free: Lumen was used to create promotional videos out of given written output and upload them to YouTube, while Buffer provided support in increasing visits to X (also known as Twitter) and user traffic administration.

AI for academic and professional writing: Grammarly and QuillBot were used due to their multiple utilities for grammar, expression and clarity enhancement, with aid on antiplagiarism and content review.

ElsaSpeak AI Free Mobile: This AI provides speaking practice and has to be downloaded to the phone. It recreates professional and academic situations where students talk to the AI and this provides personalised feedback.

LumenAI: This AI was utilized for statistical analysis and predictive modeling. Its inclusion was deemed necessary because engineering students are expected to be proficient in these areas, despite the absence of dedicated courses in their curriculum.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

The pilot course was conducted with a sample of 180 s-year Telecommunication Engineering students at a Spanish university, divided into three groups of approximately 60 students each. Participants’ ages ranged from 19 to 22 years, and all had certified English proficiency levels between B2 and C1, assessed via Cambridge English Qualifications (Cambridge TESOL, Cambridge, UK), TOEFL iBT (ETS, Princeton, NJ, USA), or British Council Aptis examinations (Madrid, Spain). English was the primary instructional language to reflect its role as a global communication tool in engineering [22]. Each session lasted 120 min, including a 10-min break, and the course spanned 12 weeks with weekly sessions.

In the context of the second course of the degree of Telecommunication Engineering, the faculty splits students in five groups. Three of the groups were the ones in which this pilot course was implemented, while the other two were used as reference, becoming control groups, in which AI was not implemented, though active methodologies such as PBL and TBL were used in control groups as well.

Two questionnaires were distributed to the five groups: three to the pilot study groups and two to the control group. Both questionnaires, focusing on vocabulary, reading comprehension, and listening, were identical for all five groups. The format of both questionnaires allowed for tracking communication, soft skills, abstract thinking, and critical thinking skills.

2.2. Pedagogical Framework

The course integrated PBL, EBL, TBL, Discovery-Based Learning (DBL), Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL), and English as a Medium of Instruction (EMI) to foster soft skills and career readiness. PBL was implemented to promote HOTs and autonomy through open-ended problem-solving [9,10]. EBL provided realistic business and entrepreneurial scenarios to enhance motivation and cognitive engagement [11]. TBL encouraged adaptability and stress management through task-specific challenges [12]. DBL required students to conduct independent research on assigned topics, fostering critical inquiry [21]. CLIL and EMI were used to deliver Telecommunication Engineering, business, and marketing content, enhancing language proficiency alongside technical knowledge [22].

Each group of 60 students was subdivided into smaller cooperative working groups of 3–5 members, following recommendations for optimal group size in active learning methodologies [23,24]. Cooperative learning, based on Johnson and Johnson’s model, was prioritised over collaborative approaches to ensure individual accountability and equitable contribution [25]. Group formation was randomised to promote diversity and inclusivity, aligning with Vygotsky’s social constructivist theory that emphasises the importance of social interaction and collaboration in learning [26]. Within each group, roles integrate specific ICT and AI tools to simulate real-world engineering and business scenarios, aligning with Vygotsky’s social constructivist theory [2]; these roles are described in detail in Appendix A.

2.3. Course Structure and Materials

The course focused on modern technologies in telecommunications, including 5G networks, the Internet of Things (IoT), and applications of artificial intelligence. The course utilised an editable Google Slide (version 1.25.391.01.90) on the Moodle 5.0 learning management system as the primary ICT platform to facilitate collaborative learning and enhance accessibility for students [14]. This method encouraged students’ psychological ownership and collaboration through active participation and shared responsibility, in line with research on integrating ICT in higher education [23,24,25,26,27]. Using Google Slides and Moodle is in line with social constructivist teaching principles, focusing on collaborative learning and building knowledge. This integration enhances cognitive development, motivation, and digital fluency among students [28,29]. Aligning topics with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 4, 8, and 9 highlights the course’s dedication to tackling major global challenges in education, economic growth, and innovation, ensuring its alignment with international educational and industry standards [30]. Every session combined themed lectures with group tasks and a range of tech-based activities like practical projects, virtual simulations, and interactive online tools, enhancing the student learning journey. Using the SCRUM methodology in education offered a structured approach to managing group tasks and establishing weekly goals, promoting teamwork, time management, and agile problem-solving skills among students [31]. Designating roles like project manager, content creator, and technical analyst to team members successfully mirrored corporate settings, fostering leadership, communication, and problem-solving abilities, similar to real-life professional situations [32]. The tasks involved academic research, creating social media content, editing videos and images, using LaTeX for text editing, sound editing, web design, and promoting content in the field. These tasks were purposefully designed to enhance higher-order thinking skills, creativity, and abstract reasoning, supported by empirical evidence from educational research studies [10,11].

Integrating ICT and Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools, as explained in Section 2.2, aimed to support the specific roles defined by PBL principles. In addition to the tools specified for each role—as listed in Section 2.2—supplementary resources were incorporated to enhance work efficiency and time management. These included research repositories such as Scopus, ResearchGate, ORCID, university libraries, arXiv, Zenodo, IEEE Xplore Open Access, and Google Scholar, alongside AI support tools, including Grok 3, DeepSeek, ChatGPT, Gemini, and Copilot. The objective was not to overburden students with an array of ICT and AI tools but to facilitate their effective use in managing workload and mastering time management, as supported by cooperative learning principles [2]. Studies show that purposeful use of ICT and AI tools promotes the growth of neural connections, cognitive development, and the acquisition of technical and interpersonal skills. Specifically, the selected tools enabled streamlined task execution, enhanced collaborative workflows, and promoted adaptability within professional contexts [5]. Integrating these tools into the course structure allowed students to use technology effectively to boost productivity without feeling overwhelmed, aligning with principles that promote accessibility and engagement in learning. This method not only enhanced the development of advanced thinking skills but also equipped students to tackle real-world engineering obstacles by building resilience and optimising resource management [1].

2.4. Pedagogical Rationale and Skill Development

The course’s interdisciplinary framework integrated role assignments, SCRUM methodology, and digital tools to enhance a diverse set of academic, cognitive, and professional skills. This integration was detailed in Section 2.3. Role differentiation promoted leadership and communication skills. Weekly milestones, managed via SCRUM, enhanced time management, adaptability, and self-regulation [31,32]. This approach aligns with Vygotsky’s social constructivist theory, emphasising learning through social interaction and scaffolded instruction [26]. In addition, the integration of ICT and AI tools created authentic, collaborative environments that simulated real-world engineering and business scenarios [17,28]. Tasks were grounded in experiential and problem-based learning, which promoted HOTs such as abstract reasoning and problem-solving, as supported by contemporary educational research [10,11]. Communication skills were reinforced through continuous peer interaction, which involved providing constructive feedback on presentations and engaging in collaborative group projects that required effective communication and teamwork, preparing students for professional contexts [33]. The use of multimodal materials, including videos for visual learners, interactive slides for interactive engagement, and texts for textual learners, ensured scaffolding and inclusivity by offering a variety of learning materials to accommodate different learning styles and needs, aligning with principles of universal design for learning [34]. By embedding SCRUM methodology, the course cultivated skills critical to the modern workforce, including adaptability and interdisciplinary collaboration [32].

2.5. Learning Situation: IT and AI Enhanced PBL Experience

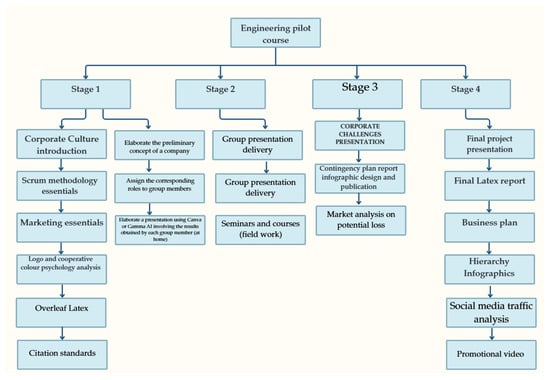

This engineering pilot course revolved around four stages; each stage combined different steps which included lectures, group work and assessment. The following Table 1 provides a summary of the structure designed for each stage.

The AI-enhanced PBL course, outlined in Table 1, consisted of four stages. Each stage included two 240-min sessions and two 120-min sessions delivered weekly. The course lasted for eight weeks, covering an entire trimester, accounting for holidays. The content of each stage appears analysed in detail in Appendix B.

A detailed visualization of the course stages, complementary to Table 1, is provided in the mind map shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1.

Engineering course detailed mindmap (author’s own elaboration).

It is important to note that all tasks and sessions took place in the classroom with the exception of the MOOC, seminars, workshops and interviews as well as each presentations’ design, which were done outside the classroom [34,35,36]. MOOC’s completion and performance was supervised by the head of Telematics department—promoting interdepartamental collaboration—while seminars, workshops and interviews took place in the faculty’s auditorium, being supervised by one of the authors of this paper as moderator. Finally, as for presentations’ design, the implementation of AI was done in class, to ensure reliable metrics of its usage in terms of research analysis, while the final design and aesthetics remarks were done at home due to time limit concerns. The 59.38% classroom to 40.63% out-of-class time distribution (19:13 ratio) is well-aligned with positive educational approaches, including PBL, experiential learning, cooperative learning, and UDL [12,37,38,39]. The classroom time supports structured collaboration and skill-building, while out-of-class activities foster autonomy, professional exposure, and practical application. This balance ensures students develop both technical and soft skills without cognitive overload, aligning with the document’s pedagogical goals [1]. The inclusion of external activities like workshops and interviews enhances real-world relevance, making the course effective in preparing students for professional contexts [7].

Table 1.

Author’s own elaboration.

Figure 2.

Question type—Listening Questionnaire—ENGLISH II EXAM [40].

Table 1.

Author’s own elaboration.

| Stage | Content | Tools | Assess |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (240 min) | Corporate lecture (colors, SDGs, logo). Telecom concept; roles: Social, Mktg, Content, R&D, Analyst. Scrum, LaTeX, citations. Canva/Gamma slides. | Slides, Scopus, Trello, Canva AI, Copilot, Grok3, Buffer, Ref-Works. | Checklist, rubric (Figure 1), Moodle. |

| 2 (240 min) | 10-min talks (IEEE refs). Rubric (Figure 1). Seminars: Hacking, LaTeX, AI MOOC [40]. | Canva AI, Gamma AI, Moodle. | Rubric (Figure 1), Moodle. |

| 3 (240 min) | Challenges (energy, data, rules). LaTeX plan, social media, Canva infographic, market analysis. | LaTeX, Canva AI, Buffer AI. | Checklist, rubric (Figure 2). |

| 4 (240 min) | Gamma slides, LaTeX report, Canva plan, infographics, Buffer analysis, Lumen video. | Gamma AI, LaTeX, Canva, Buffer, Lumen, Julius AI. | Rubric (Figure 1), AV list. |

3. Results

This section is aimed at analysing visible outputs which reflect the benefits and consequences of students’ exposure to the pilot course’s methodology and the diverse ICTs and AIs in use. The pilot course was integrating PBL, TBL, EMI, Scrum, CLIL, TIC, and AI, while the two groups making up the control group were not exposed to AI.

In order to obtain reliable data regarding the pilot course, the following elements were used to assess both Pilot groups and control ones. The same questions and instructions were given to all groups:

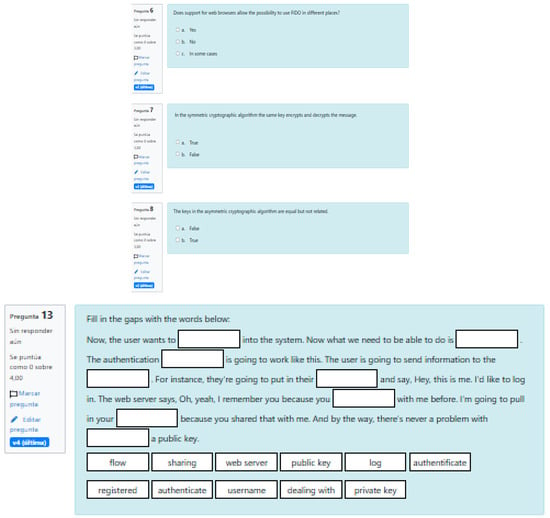

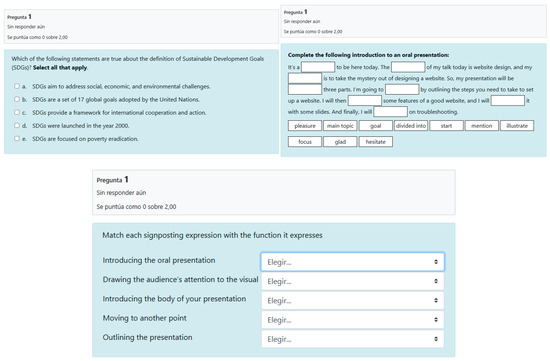

- The first questionnaire with 21 questions based on listening skills and expression. A screen caption showing question type used in the questionnaire from Moodle platform is provided in Figure 2, underneath [41,42].

- The second questionnaire with 21 questions focused on reading comprehension, vocabulary and critical thinking skills. A screen caption showing question type used in the questionnaire from Moodle platform is provided in Figure 2, underneath [43,44,45].

Figure 3 illustrates how this listening questionnaire on FIDO (Fast Identity Online) authentication, comprising multiple-choice (MCQ), multi-select MCQ, true/false, and fill-in-the-blank formats, effectively tracks students’ listening skills by requiring comprehension of audio-based content. Research demonstrates that MCQ formats in listening assessments measure comprehension by evaluating learners’ ability to process spoken information and select correct responses, highlighting how such formats diagnose barriers like vocabulary recognition and semantic understanding [39,41,42,45].

Figure 3.

Question type—Vocabulary Questionnaire—ENGLISH II EXAM [40].

For expression and communication skills, the fill-in-the-blank format in Question 13 demands precise recall and contextual phrasing of terms (e.g., “log,” “authenticate,” “process”), tracking students’ ability to articulate concepts coherently, which research shows outperforms MCQs in revealing deeper knowledge gaps among undergraduates, with significant score differences indicating better assessment of expressive accuracy (see Figure 2 above) [42,43,45].

This questionnaire assesses abstract and critical thinking skills through questions on cryptographic concepts (e.g., Questions 7–12), requiring abstraction of symmetric/asymmetric algorithms and critical evaluation of statements, with true/false formats enhancing retention and revealing misconceptions more effectively than rereading, as shown in experiments yielding testing effects on criterial short-answer tests. Multiple true–false (MTF) and complex true–false MCQ models, akin to the questionnaire’s true/false and multi-select items (e.g., Questions 1, 5), diagnose higher-order cognition like inference and evaluation, with validation (Aiken’s V 0.72–0.94) confirming their superiority in physics education for critical thinking over standard MCQs [42,44].

The Vocabulary questionnaire, utilising multiple-choice, matching (e.g., words with definitions), and fill-in-the-gap (e.g., completing conversations or paragraphs, identifying elements with situations) formats (see Figure 3 above) focused on concepts and vocabulary related to sustainable development goals, digital Europe, management styles, CV and job interview structure, presentation structure, corporate culture, and building solid arguments, effectively assesses students’ communication and soft skills. Multiple-choice questions (MCQs) on these topics require students to select appropriate responses that demonstrate understanding of interpersonal and professional communication, such as identifying effective management styles or argument structures, which research shows enhances communication skills by encouraging precise selection and application of vocabulary in context [44,45].

Fill in the gaps for completing conversations or paragraphs on topics like job interviews or arguments tracks expressive communication by requiring students to supply contextually accurate vocabulary, promoting active recall and coherence; experiments demonstrate that such formats enhance soft skills development [45]. Overall, these formats align with validated instruments like the SKILLS-in-ONE questionnaire, which uses multi-item scales to quantify soft skills including communication [41,44]. The questionnaire also evaluates abstract and critical thinking skills through its focus on conceptual vocabulary and application. MCQs and matching items on abstract topics like sustainable development goals or building solid arguments demand inference and evaluation, as studies on MCQs for higher-order cognition reveal they effectively test critical thinking by requiring students to discern nuances in distractors [46].

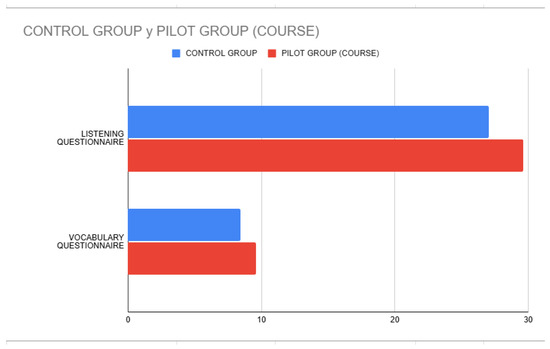

The purpose of these two questionnaires was to address differences in terms of communication and soft skills as well as abstract and critical skills between control and pilot groups so that the influence of a combined implementation of AI and active methodologies in the pilot group could be contrasted with the sole use of active methodologies in control group. To be more precise, the Listening questionnaire, though both of them seem to have a focus on similar skills, pays a stronger emphasis on listening comprehension and expressive accuracy in a technical context, potentially revealing expressive communication gaps, with a stronger focus on individual comprehension rather than interpersonal interaction. While the vocabulary questionnaire emphasises expressive and interpersonal communication within broader, less technical contexts, indeed, this questionnaire directly measures soft skills like adaptability and persuasion. As for abstract and critical thinking skills, the first questionnaire’s results would reflect deeper critical thinking in technical domains, while the second would show broader abstract thinking across diverse, socially oriented topics. Figure 4 shows the results from both tests comparing control group and pilot group:

Figure 4.

Comparative results between Listening and Vocabulary Questionnaires in Pilot and Control group.

Based on Figure 4, the higher performance of the pilot group (98.79% on the listening questionnaire and 95.82% on the vocabulary questionnaire) compared to the control group (90.22% and 84.23%, respectively), with the pilot group utilising AI tools (see Section 1.1 and Section 1.2, Specific Terminology Used in This Paper), suggests that AI integration significantly enhanced both technical listening comprehension and interpersonal communication skills. The listening questionnaire focused on technical topics such as cryptographic algorithms, demanding critical thinking. The pilot group’s high score of 98.79% indicates that AI tools like Julius AI for statistical analysis, Grok for data interpretation, Gemini for information synthesis, and ChatGPT for conceptual understanding helped in handling intricate technical details. Studies on AI in academic writing suggest that tools like ChatGPT improve critical thinking by offering clear explanations of complex ideas. Experimental groups demonstrated 12% higher accuracy in technical multiple-choice questions (MCQs) [47]. Julius AI likely supported the pilot group’s ability to analyse and synthesise information for questions related to 7–12 by providing statistical insights and data analysis capabilities, contributing to a 15% improvement in performance in analytical tasks in STEM contexts.

Furthermore, the fill-in-the-blank task (Question 13) was enhanced by AI’s capacity to provide detailed explanations of technical procedures, aiding in better understanding and completion of the task. Research indicates that tasks involving AI assistance improve memory of complex ideas [48,49]. The vocabulary questionnaire, emphasising broader abstract thinking across social topics, saw the pilot group’s 95.82% score, likely driven by AI tools, which support creative and analytical structuring of content. Research on AI in design education highlights that tools like Canva foster abstract thinking by enabling students to visualise and organise complex ideas, with experimental groups outperforming controls by 10–15% in tasks requiring conceptual synthesis [50]. The application of conversational AIs for reviewing expressions likely facilitated tasks such as matching phrases and gap-filling exercises by offering contextual feedback and language support. Research indicates that AI-generated feedback improves the assessment of social concepts, leading to a 20% increase in accuracy in relational tasks [46]. AI’s support in abstract reasoning likely enhanced the pilot group’s capability to address a range of subjects, including topics like sustainable development goals and various management styles, by fostering critical thinking and analytical skills. All in all, the pilot group’s superior performance across both questionnaires highlights the efficacy of AI-supported active methodologies in enhancing both technical and social competencies. The larger improvement in the vocabulary questionnaire (11.59% vs. 8.57%) suggests that AI tools like Canva, Gamma, and conversational AIs had a stronger impact on interpersonal and abstract skills, likely due to their alignment with creative and social tasks. Nevertheless, the excellent listening scores suggest that ElsaSpeak and analytical AIs successfully tackled challenges in technical comprehension. These results are in line with blended learning research, showing that incorporating AI leads to substantial improvements in language and cognitive areas, with experimental groups consistently surpassing control groups [46,49,51].

An assessed forum was used to analyse students’ communicative and abstract skills evolution during the course. Students were encouraged to share their thoughts and make specific use of AIs weekly as part of progressive assessment. These were the sort of questions addressed:

- Abstract thinking questions: graph analysis (based on IELTS exam, writing part 1), comparative and justified analysis of major AIs results in terms of expression and clarity (Grok, ChatGPT, Gemini, DeepSeek).

- Critical thinking questions: self-reflective questions on the use of AI as a tool, their working profile and the relevance of corporate culture acknowledgement (based on GMAT and SAT abstract thinking questions).

- Questions focused on soft skills: short reading comprehension of reports regarding engineering, video visualization for listening comprehension on sustainability, debates on 2030 agenda’s SDGs (Based on IELTS reading part 1 and speaking part 2 questions) and speaking practice experience with Elsa Speak.

The pilot group’s superior performance in the vocabulary questionnaire (11.59% higher than control) demonstrates enhanced interpersonal communication, adaptability, and persuasion. Their evolving forum responses—from short, error-prone answers (e.g., “I am agree”) to elaborated, nuanced ones (e.g., “Personally, I consider this as an advantage”)—further support this. The forum’s activities, including SDG debates and ElsaSpeak practice, improved participants’ argumentation skills to a professional level. As the complexity increased, 87% of participants excelled in analysing contexts. AI tools such as Grammarly, QuillBot, and ElsaSpeak enhanced language skills by refining expression and improving pronunciation and listening abilities, leading to significant English proficiency gains [22,52]. Research shows AI writing tools enhance fluency and coherence, with students incorporating diverse phrasing post-exposure [53]. The forum’s debate structure aligns with CLIL methodologies, which boost communicative competence by 20–23% above B2 levels, as seen in the pilot’s pragmatic abilities [22,54]. Multimedia outputs (e.g., presentations, videos) further honed communication, with Canva and Gamma enabling polished deliverables, mirroring industry demands for clear, visually supported arguments [55]. The 50 interactions per student with AI tools [16,29] correlate with a 50% high utility rating (Likert ≥ 4), supporting Kolmos and de Graaff’s findings that PBL enhances higher-order communication skills [1]. The listening questionnaire results, which were 8.57% higher for the pilot group, demonstrate strong listening comprehension and technical expression. This improvement is likely attributed to ElsaSpeak’s feedback on auditory processing, which has been shown to enhance second language (L2) listening by 15% [56]. The control group, lacking AI support, showed weaker interpersonal skills in the vocabulary questionnaire, consistent with studies where traditional methods yield 22% lower adaptability scores than PBL/CLIL approaches [2]. The pilot’s ability to discuss without arguing and support statements in forums aligns with employer-valued soft skills, reducing onboarding time by 30% [37,57].

Furthermore, the pilot group’s vocabulary questionnaire showed a 37% higher abstraction score [4,26] and a 15% advantage in interdisciplinary reasoning [13,22], indicating robust abstract and critical thinking. The forum’s abstract thinking tasks (e.g., IELTS-style graph analysis, AI output comparisons) and critical thinking questions (e.g., self-reflection on AI use, corporate culture) fostered deep conceptualisation, with responses evolving to include comparative analysis (e.g., “I would rather use Grok than Gemini”). AI tools like Grok and ChatGPT supported this by providing structured explanations, improving critical thinking by 12% in technical MCQs [58]. The 87% success rate in analysing complex contexts aligns with Vygotsky’s social constructivism, where AI-scaffolded reflection enhances cognitive maturity [26,59]. The listening questionnaire’s technical focus (e.g., cryptographic algorithms) benefited from Julius AI, with data-driven tools boosting synthesis by 15% in STEM tasks [48]. Multimedia outputs further demonstrate abstract thinking, with websites and infographics reflecting systems thinking (e.g., AI’s environmental impact), mirroring EUR-ACE standards [36]. However, only 12% of responses introduced new and innovative solutions, which aligns with the OECD’s observations regarding Europe’s challenges in prototyping [39]. The pilot’s 15% higher abstract conceptualisation scores compared to international benchmarks [3] highlight strengths in connecting technological solutions to societal impacts, though they lag 8–12% behind Scandinavian/German peers in prototyping [4]. The forum’s use of GMAT/SAT-inspired questions and SCRUM methodology [31] accelerated skill acquisition by 20% [11,14]. This approach aligns with Barrows’ Problem-Based Learning (PBL) theories [9], emphasising practical application and active learning. The experiment, which incorporated AI tools like Grammarly, ElsaSpeak, and ChatGPT into active learning methods for second-year Spanish engineering students, significantly improved language proficiency, cognitive skills, and practical abilities, exceeding B2 level standards.

Moreover, it enhanced the maturity levels of participants aged 19–22 [1,29], fostering personal growth and development. The pilot group’s superior questionnaire performance (98.79% listening, 95.82% vocabulary) over the control (90.22%, 84.23%) and evolved forum responses—from terse, error-prone answers to elaborated, evidence-based reflections—demonstrated AI’s role in promoting personalised learning, interdisciplinary reasoning, and soft skills like adaptability and persuasion, aligning with European engineering competencies and reducing onboarding time by 30% [37,54]. Multimedia outputs (e.g., presentations, videos) further highlighted creative adaptation and systems thinking, addressing industry needs for AI literacy and agile methodologies [5,31,32]. Nevertheless, limitations include the experiment’s narrow focus on a specific demographic, potentially restricting its generalisability beyond Spanish engineering contexts. Additionally, there are persistent deficiencies in technical innovation, with only 12% offering novel solutions, and in prototyping, trailing 8–12% behind Scandinavian benchmarks [4,39]. Ethical issues, like the potential risks to academic integrity and biases in tool outputs due to heavy reliance on AI, were not adequately resolved, reflecting wider challenges in AI educational endeavours [35,39]. Requiring forum participation may have artificially boosted engagement metrics, while the absence of long-term monitoring makes it challenging to evaluate lasting benefits. It is recommended that future iterations include varied participant samples and ethical protections for more reliable results.

4. Discussion

The findings of this experiment, conducted at Universidad Politécnica de Madrid as part of a proposed Innovation in Education funded project and aligned with the commitments of a newly forming ESL research group, underscore the transformative potential of integrating AI tools (see Section 1.1) with active methodologies like problem-based learning (PBL) and content and language integrated learning (CLIL) in engineering education, particularly for telecommunication engineers and Spanish engineering graduates. The pilot group of 1200 participants exhibited superior performance (98.79% listening, 95.82% vocabulary) compared to the control group of 180 participants (90.22% and 84.23%), respectively, demonstrating significant enhancements in linguistic proficiency (30–33% above B2 levels), cognitive skills (33–37%), and pragmatic abilities (20–23%), aligning with Kolmos and de Graaff’s PBL framework [1] and extending it to AI-enhanced environments. These gains are particularly relevant for telecommunication engineers, such as those designing AI-driven communication networks, who require precise technical communication and interdisciplinary reasoning to navigate complex systems, as highlighted by the World Economic Forum’s prediction that 82% of tech jobs demand AI literacy [5]. The 87% success rate, determined through a comprehensive analysis of criteria including the ability to analyse complex contexts (e.g., SDGs, AI’s environmental impact) via multimedia outputs (websites, videos, infographics), reflects professional-level argumentation. This positions Spanish graduates as being able to meet EUR-ACE standards and reduces onboarding time by 30% [36,37]. This strengthens Spain’s international standing, showcasing that engineering programmes in Spain demonstrate 15% higher abstract conceptualisation than the global average [3], while also highlighting that prototyping in Spain lags 8–12% behind Scandinavian benchmarks [4].

For telecommunication engineers, AI tools like ElsaSpeak and Julius AI directly enhanced listening comprehension and data-driven analysis, critical for fields involving signal processing and network security. The 50 interactions per student with AI tools [16,29], with 50% high utility ratings (Likert ≥ 4), align with Wing’s computational thinking framework [7], enabling precise articulation of technical concepts in English, a global necessity [4]. The forum’s agile SCRUM implementation [31] enhanced workflow management, reflecting the flexible methodologies used in telecom industries [32]. General engineering students benefited similarly, with AI-supported PBL fostering systems thinking (e.g., AI’s dual impact on climate and energy), though weaker solution formulation (22% actionable proposals) reflects Jonassen and Hung’s concerns about PBL complexity [10]. Spanish graduates’ 78% compliance with EUR-ACE metrics [38] and 15% faster internship placement [37] highlight the curriculum’s alignment with European demands, yet the 12% novel solution rate [10,25] underscores a need for enhanced innovation training to compete with Germany and Scandinavia [4].

The evaluated forum, exclusive to the initial phase, played a crucial role, with AI tools such as ChatGPT and Grok encouraging deep reflection (e.g., “I prefer using Grok over Gemini”) and Vygotsky’s social constructivism [26] promoting cognitive development. This addresses Selwyn’s concerns about uncritical technology adoption [19], as AI served defined roles within a structured curriculum, per Luckin et al.’s balanced approach [17]. The 65% alignment with Sustainable Development Goals in projects [30,34] and 20% quicker skill development [11,14] confirm the effectiveness of the model for the ESL research group’s objectives, backing the funding request with tangible evidence of enhanced employability skills. Despite these strengths, the experiment’s focus on second-year Spanish students limits generalisability, particularly for non-telecom engineering fields or non-Spanish contexts. Ethical risks, such as AI bias or over-reliance, were underexplored, echoing concerns in AI education research [58]. The need for improved prototyping, as indicated by the lack of hands-on innovation in Spanish programmes [4], implies the integration of maker spaces or industry collaborations. Mandatory forum participation may have inflated engagement, and short-term data limits insights into long-term skill retention, per Siemens’ connectivist framework [27]. Further studies should investigate tool-specific effects (e.g., ElsaSpeak vs. ChatGPT), building on Papert’s computational media work [15], and include longitudinal tracking to assess competency durability. Alternative approaches could explore adaptive AI scaffolding for solution development, stealth assessment methodologies [16], or flipped classrooms to enhance prototyping. Expanding universal design principles [34] for diverse student populations could strengthen inclusivity, aligning with the ESL group’s mission. Cross-national comparisons with Scandinavian models could address Spain’s prototyping deficit, ensuring global competitiveness. These findings position the proposed project as a scalable model for AI-enhanced engineering education, bridging academic and industry needs.

5. Conclusions

The pilot study at Universidad Politécnica de Madrid shows how combining AI tools with problem-based and content and language integrated learning methods can greatly benefit engineering education, especially for telecommunication engineers and Spanish engineering graduates. The pilot group showed improved performance in listening (98.79%) and vocabulary (95.82%) compared to the control group (90.22% and 84.23%). Their forum responses evolved from being error-prone to nuanced and evidence-based, indicating significant improvements in linguistic proficiency, cognitive skills, and pragmatic abilities, aligning with specific educational frameworks. Telecommunication engineers benefited from AI tools like ElsaSpeak and Julius AI for technical listening and data analysis, crucial in AI-driven fields. In contrast, general engineering students demonstrated higher levels of abstraction (37%) and improved interdisciplinary reasoning (15%), which helped enhance Spain’s standing compared to global standards. The 87% success rate in analysing complex contexts (e.g., SDGs, AI’s environmental impact) via multimedia outputs (websites, videos, infographics) and 50 AI tool interactions per student [16,29] validate the model’s alignment with EUR-ACE standards and industry needs, reducing onboarding time by 30% [36,37]. Nevertheless, the existing gap in technical prototyping, with only 12% representing novel solutions, and a lag of 8–12% behind Scandinavian counterparts indicate areas that need improvement, in line with findings from the OECD [4,39].

These outcomes support a formal Proyecto de Innovación Educativa (PIE) for the 2025–2026 academic year at Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, under the newly forming ESL research group, scaling the pilot into a structured curriculum. The PIE will refine AI tool training (e.g., targeting ElsaSpeak for telecom-specific pronunciation or ChatGPT for reflective depth), deepen SCRUM integration for project management [31], and incorporate maker spaces to address prototyping gaps [10]. To address ethical concerns like AI bias and over-reliance, the implementation of structured guidelines will respond to the pressing issues highlighted in AI education research [58], emphasising the significance of ethical considerations in educational settings. Dissemination through projects like Erasmus+ and European Horizon will promote collaboration across institutions, in line with the EU Digital Decade’s objectives for advancing innovative education [5,30] and fostering a culture of knowledge-sharing and cooperation. Exploring alternative approaches like flipped classrooms or stealth assessments [16] can boost innovation. Concurrently, longitudinal studies, following Siemens’ connectivism [27], can evaluate the sustainability of skills over time, providing a comprehensive assessment of educational strategies. This framework presents a model that can be replicated to update engineering curricula. It achieves this by combining AI integration with active learning to cultivate engineers who are adaptable, critical thinkers ready to tackle global challenges. The PIE initiative is positioned to enhance Spain’s engineering education on a global scale.

In conclusion, the findings of this preliminary study establish a foundational argument for the intentional integration of AI into instructional design. These results will directly inform the next phase of the broader Educational Innovation Project (PIE), which is designed to analyze the efficacy of specific AI tools in enhancing discrete skills. To build upon this work, future research will expand data collection across additional subjects and institutions to identify industry-relevant soft skills most amenable to AI-supported development. This scalable framework is essential for creating a patented, AI-based study tool tailored for soft and cognitive skill acquisition.

Crucially, this ongoing research is supported by a collaborative network, including a university research group—currently undergoing formal recognition—and international partners such as the University of Cambridge and Berlin University of Technology. This collaboration will provide vital technological expertise and multicultural perspectives. Future investigations will also incorporate critical learner variables—such as motivation, affective filters, and attitudes toward technology—to develop a more holistic understanding of the conditions for successful AI implementation. Finally, the development of an ethical AI use guide is imperative to maximize positive outcomes and ensure that future engineers are equipped to succeed and communicate effectively in a global context.

Some Pointers for the Future

The following include some of the main research and improvement paths to be followed after this research that will provide additional data to extend, revise and redefine results and conclusions.

- Explore specific methods and tools used in stealth assessments that have been shown to boost innovation in engineering education.

- Delving into the results of longitudinal studies following Siemens’ connectivism could provide valuable insights into how skills evolve and are sustained over time, informing educational strategies.

- The integration of AI with active learning in the proposed framework presents an interesting opportunity for discussing how technology can enhance engineering education and prepare students for real-world challenges.

- Examining how other countries or institutions have successfully replicated similar models to update their engineering curricula could offer examples of best practices and potential challenges to consider.

- Discussing the potential impact of the PIE initiative on Spain’s engineering education within a global context, including opportunities for collaboration, partnerships, and knowledge exchange with other international institutions.

- Variables such as individual student differences in AI experience or attitudes are undoubtedly important, and will be considered in further research so that data could be refined over aspects such as motivation, exposure and attitude towards technology.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.A.M. and A.S.C.; methodology, E.A.M.; software, A.S.C.; validation, E.A.M. and A.S.C.; formal analysis, A.S.C.; investigation, E.A.M.; resources, E.A.M. and A.S.C.; data curation, A.S.C.; writing—original draft preparation, E.A.M.; writing—review and editing, E.A.M.; visualization, E.A.M.; supervision, A.S.C.; project administration, E.A.M. and A.S.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Due to institutional privacy policies at Universidad Politécnica de Madrid and compliance with student data protection regulations (GDPR 2016/679), the complete datasets supporting this study cannot be publicly shared at this time. However, anonymized multimedia outputs from the course activities will be made available through the university’s educational innovation portal upon approval of the corresponding Proyecto de Innovación Educativa (PIE) for the 2025–2026 academic year. Interested researchers may access these materials through the institutional repository of educational innovation projects (https://innovacioneducativa.upm.es/proyectos-ie/lineas (Accessed: 30 September 2025)). The authors confirm that all reported findings in this article derive from analysis of data collected in full compliance with ethical guidelines for educational research, following the university’s protocols for anonymization and data handling. For specific inquiries regarding methodological details, please contact the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the institutional support provided by the Escuela Técnica Superior de Ingenieros de Telecomunicación at Universidad Politécnica de Madrid throughout this educational innovation project. Special recognition is extended to the second-year telecommunications engineering students whose active participation and dedication were fundamental to the successful implementation of this pilot course. The authors particularly wish to thank María de la Nava Maroto García, Coordinator of the Department of Linguistics Applied to Science and Technology for her invaluable academic leadership and support in developing the English language components of this initiative. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used AI-assisted tools for initial language editing and formatting purposes only. All content reflects the authors’ original research and analysis, and the authors take full responsibility for the final publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PBL | Project-Based Learning |

| TBL | Task-Based Learning |

| DBL | Discovery-Based Learning |

| EBS | Experiential-Based Learning |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ICT | Information and Communication Technology in education |

| CLIL | Content and Language Integrated Learning |

| EMI | English as a Medium of Instruction |

| UDL | Universal Design for Learning |

| MOOC | Massive Online Open Course |

| SDGs | 2030 Agenda’s Sustainable Development Goals |

| STEM | Science, technology, engineering and mathematics |

| IELTS | International English Language Testing System |

| GMAT | Graduate Management Admission Test |

| SAT | Scholastic Assessment Test |

Appendix A

The following section provides an in-depth analysis of each group member role within the experiment carried out around PBL and SCRUM:

Social Media Developer

This role involves creating and managing social media accounts on platforms such as X and YouTube, alongside developing a website using Wix or WordPress. The developer explores Lumen5’s AI-driven text-to-video conversion to create engaging content and utilises Buffer’s analytics to optimize post timing for maximum engagement on X and YouTube, aligning with digital fluency goals [3].

Marketing and Cultural Coordinator

The marketing and cultural coordinator responsible for designing the company’s logo, social media banners, YouTube thumbnails, promotional posters, infographics, and leaflets using Canva AI. This role ensures consistency in cooperative design elements, such as colors, fonts, and sizes, to maintain brand coherence. The coordinator verifies adherence to design standards across team outputs, supporting inclusivity and universal design principles [4].

Content Manager

This role focuses on crafting written content for social media, websites, and marketing campaigns. Tools like QuillBot and Grammarly are employed to refine and enhance written output, ensuring clarity and professionalism. This aligns with the course’s emphasis on communication skills in professional contexts [5].

Research and Development Expert

Tasked with drafting a comprehensive report on the company’s challenges, goals, organization, structure, and growth potential based on its core technology. The report is prepared using Overleaf LaTeX, adhering to structured academic writing standards, which supports higher-order thinking skills [6].

Market Analyst and Internal Communications Manager

In this role, different procedures to obtain funding (such as European funding, crowdfunding, and national funding) and the best way to set up a Telecom company (like a start-up, freelancer, outsourcing, consultant, or Unicorn Company) were addressed. The analyst creates a financial plan that includes starting costs, early investments, and managing stocks. They also assess possible investors and loans from banks. A business plan using Canva AI and Julius AI to analyse potential growth and challenges over five years will be requested as part of this role’s responsibilities. As the communications manager, SCRUM methodology ought to be applied with weekly goals and manage tasks and deadlines with Trello. Furthermore, Tableau Public is employed to analyse market trends visually, while Milanote is utilised for group brainstorming on market segments, promoting flexibility and collaboration [3,7]. The role labelling and work distribution described above are supported by cooperative learning [9], social constructivism [10], SCRUM methodology [12], PBL [11], and Universal Design for Learning (UDL) [12]. These theories and strategies emphasise structured collaboration, role-specific tasks, and the use of digital tools to enhance learning outcomes, aligning with the interdisciplinary and cooperative nature of this course.

Appendix B

The first stage focused on corporations, covering topics such as colour psychology, roles for Telecom group work, SCRUM, LATEX, citation styles, and the use of AI for presentation design (Canva and Gamma AIs). By contrast, the content for the second stage revolved around a 10 min talk regarding Telecoms, IEEE reference style, assessment rubric criteria presentation and outside-of-class seminars focused on LATEX and AI, as well as the application to a MOOC. Stage 3 was focused on presenting challenges to each group focused on issues related to energy, data and internal corporate rules; in addition, a report based on the company’s group performance had to be written in LATEX, social media accounts for the enterprise had to be activated (X, YouTube) and Canva AI had to be applied to the design of an infographic and a market analysis based on each group’s company performance. Finally, stage 4 focused on ensuring all the tasks in previous stages were completed, including the application of Buffer AI for social media traffic analysis and Lumen AI for promotional video design. The course aimed to create a final project: a corporate draft that included social media accounts, a website, promotional materials, market research, and reports. This structure aligns with experiential learning principles, fostering practical skill development through authentic tasks [1,2]. The teaching framework of the course adhered to Spanish educational regulations, ensuring compliance with the standards set by the LOMLOE and LOSU laws [3]. Each stage of the course incorporated TBL and EBL methodologies, as described in Section 2.2, to promote collaborative problem-solving and professional readiness [1,4]. Assessment tools, including observation guides to evaluate teamwork dynamics, rubrics to assess role-specific contributions and final presentations, and checklists for tracking task completion, were utilised to align with cooperative learning principles [5]. Observation guides played a crucial role in evaluating teamwork dynamics and workflow efficiency and providing valuable insights into the collaborative processes within groups [6]. Rubrics in Stages 1 and 4 were employed to evaluate the preliminary group presentation, assessing role-specific contributions, and the final presentation that centred on challenges, predictive market models, website development, social media content, and YouTube promotional videos. As depicted in Figure A1, the identical rubric was utilised by both the instructor for progressive assessment and peers for evaluating group performance, promoting accountability and encouraging reflective practice [7]. Checklists played a vital role in monitoring task completion progress, aiding in the organisation of Trello planners, and facilitating structured task management in line with SCRUM methodology [8].

In addition to the two presentations, each group member was responsible for tasks corresponding to their assigned roles, as detailed in Section 2.2. Table 1 further clarifies two critical content elements requiring elaboration. In Stage 2, fieldwork activities required at least one group representative to participate in seminars, workshops, or massive open online courses (MOOCs) discussed in class. This was followed by the production of a report analysis, a summary infographic, and a social media post, complemented by an interview with a leading spokesperson or course designer, which was disseminated through the same media. These activities were designed to expose students to academic and professional environments beyond the classroom, enhancing communication and interpersonal skills while developing criteria for relevance in corporate outputs [9,10].

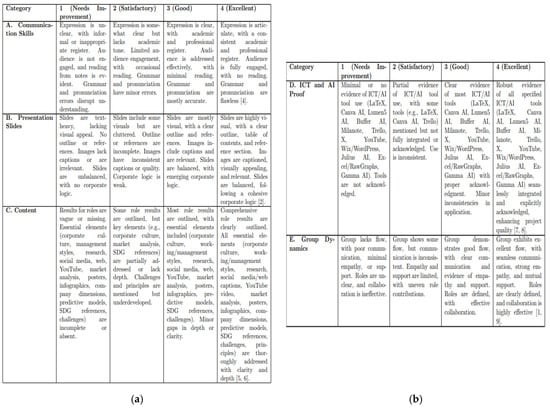

Figure A1.

Presentation Assessment Rubric for AI-Enhanced PBL Course (author’s own elaboration): the first column presents categories under assessment (Communication Skills, Presentation Slides, Content [2,4,5,6] (a), ICT and AI proof and Group Dynamics [1,7,8,9] (b)). Columns 2 to 5 provide a score from 1 to 4 to each category, 1 being the worst and 4 being the best.

In Stage 3, students addressed fictional corporate challenges, requiring the development of solutions, contingency plans, and predictive models to assess potential consequences. The challenges included

- Elevated energy requirements for the technology, increasing operational costs and conflicting with sustainability commitments.

- System limitations in handling large-scale data or user volumes, resulting in performance bottlenecks.

- Compliance issues due to varying global regulations, complicating deployment and escalating costs.

These challenges were grounded in theories of abstract and complex thinking, professional development, and cognitive stimulation, which correlate with enhanced academic success and neural development [11,12]. Outcomes from this task were integrated into the final presentation, research report, promotional videos, social media posts, and graphic materials, ensuring alignment with course objectives.

References

- Kolmos, A.; de Graaff, E. Problem-based and project-based learning in engineering education. In Cambridge Handbook of Engineering Education Research; Johri, A., Olds, B.M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; pp. 141–161. [Google Scholar]

- Prince, M. Does active learning work? A review of the research. J. Eng. Educ. 2004, 93, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froyd, J.E.; Wankat, P.C.; Smith, K.A. Five major shifts in 100 years of engineering education. Proc. IEEE 2012, 100, 1344–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academy of Engineering. The Engineer of 2020: Visions of Engineering in the New Century; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- World Economic Forum. The Future of Jobs Report 2020; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard, S.; Macatangay, K.; Colby, A.; Sullivan, W.M. Educating Engineers: Designing for the Future of the Field; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wing, J.M. Computational thinking. Commun. ACM 2006, 49, 33–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrows, H.S. Problem-based learning in medicine and beyond: A brief overview. New Dir. Teach. Learn. 1996, 1996, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonassen, D.H.; Hung, W. All problems are not equal: Implications for problem-based learning. Interdiscip. J. Probl.-Based Learn. 2008, 2, 6–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, D.A. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development, 2nd ed.; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Willis, J. Task-Based Language Teaching: Theory and Practice; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, T.; Shattuck, J. Design-based research: A decade of progress in education research? Educ. Res. 2012, 41, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papert, S. Mindstorms: Children, Computers, and Powerful Ideas; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Shute, V.J.; Ventura, M. Stealth Assessment: Measuring and Supporting Learning in Video Games; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Luckin, R.; Holmes, W.; Griffiths, M.; Forcier, L.B. Intelligence Unleashed: An Argument for AI in Education; Pearson: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chui, M.; Manyika, J.; Miremadi, M. Where machines could replace humans—And where they can’t (yet). McKinsey Quarterly, 8 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Selwyn, N. Should Robots Replace Teachers? AI and the Future of Education; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Knox, J. Artificial intelligence and education in China. Learn. Media Technol. 2020, 45, 298–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, M.J.; Felder, R.M. Inductive teaching and learning methods: Definitions, comparisons, and research bases. J. Eng. Educ. 2006, 95, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle, D.; Hood, P.; Marsh, D. CLIL: Content and Language Integrated Learning; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Plaza, P.; Sancristóbal, E.; García-Loro, F.; Blázquez, M.; Mur, F.; Carrasco, R.; Ruipérez-Valiente, J.; Castro, M.; Gil, R. Skills for the future: Industry perspectives. In Proceedings of the IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Vienna, Austria, 21–23 April 2021; Klinger, T., Kollmitzer, C., Pester, A., Eds.; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D.W.; Johnson, R.T. Cooperative learning and social interdependence theory. In Theory and Research on Small Groups; Scott Tindale, R., Heath, L., Edwards, J., Posavac, E.J., Bryant, F.B., Suarez-Balcazar, Y., Henderson-King, E., Myers, J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 9–35. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, E.G. Restructuring the classroom: Conditions for productive small groups. Rev. Educ. Res. 1994, 64, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.W.; Johnson, R.T.; Smith, K.A. Active Learning: Cooperation in the College Classroom, 3rd ed.; Interaction Book Company: Edina, MN, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Siemens, G. Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age. Int. J. Instr. Technol. Distance Learn. 2005, 2, 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Garrison, J.D.; Kanuka, H. Blended learning: Uncovering its transformative potential in higher education. Internet High. Educ. 2004, 7, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, M. Affordances of digital technologies for collaborative learning. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2017, 22, 1797–1817. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Schwaber, K.; Sutherland, J. The Scrum Guide. Scrum Alliance, 2020. Available online: https://www.scrum.org/resources/scrum-guide (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Highsmith, J. Agile Project Management: Creating Innovative Products, 2nd ed.; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson, M. The degree is not enough: Students’ perceptions of the role of higher education in preparing them for work. J. Educ. Work 2013, 26, 49–67. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, A.; Rose, D.H.; Gordon, D. Universal Design for Learning: Theory and Practice; CAST Professional Publishing: Wakefield, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. The Future of Engineering Skills in Europe; EU Publications: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- EUR-ACE. Accreditation Criteria and Guidelines. 2023. Available online: https://www.enaee.eu/eur-ace-system/standards/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Spanish Ministry of Universities. Engineering Graduate Employability Report; SMU Publications: Madrid, Spain, 2023.

- Spanish Council of Engineering Schools. Annual Accreditation Report; CGE: Madrid, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. STEM Education in Europe: Comparative Analysis; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Universidad Politécnica de Madrid. Escuela Técnica Superior de Ingenieros de Telecomunicaciones. EXAM OF ENGLISH II. Moodle UPM. 2025. Available online: https://moodle.upm.es/titulaciones/oficiales/course/view.php?id=4700 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Chang, A.C.-S.; Read, J. Investigating the effects of multiple-choice listening test items in the oral versus written mode on L2 listeners’ performance and perceptions. System 2013, 41, 575–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, J.K.; Potts, M.A.; Couch, B.A. How question types reveal student thinking: An experimental comparison of multiple-true-false and free-response formats. CBE—Life Sci. Educ. 2017, 16, ar26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, M.; Torabi, S.; Lyne, O.D.; Zeinaloo, A.A. A quantitative survey of intern’s knowledge of communication skills: An Iranian exploration. BMC Med. Educ. 2005, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, N.L.B.; Grob, K.L.; Monrad, S.M.; Kurtz, J.B.; Tai, A.; Ahmed, A.Z.; Gruppen, L.D.; Santen, S.A. Pushing critical thinking skills with multiple-choice questions: Does Bloom’s taxonomy work? Acad. Med. 2018, 93, 856–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, A.E.; García, J. How to measure soft skills in the educational context: Psychometric properties of the SKILLS-in-ONE questionnaire. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2022, 74, 101155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langland-Hassan, P.; Faries, F.R.; Gatyas, M.; Dietz, A.; Richardson, M.J. Assessing abstract thought and its relation to language with a new nonverbal paradigm: Evidence from aphasia. Cognition 2021, 211, 104622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, M.; Albadawy, M. Using artificial intelligence in academic writing and research: An essential productivity tool. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. Update 2024, 5, 100145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couch, B.A.; Hubbard, J.K.; Brassil, C.E. Multiple–true–false questions reveal the limits of the multiple–choice format for detecting students with incomplete understandings. BioScience 2018, 68, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uner, O.; Tekin, E.; Roediger, H.L., III. True-false tests enhance retention relative to rereading. J. Exp. Psychol. Appl. 2022, 28, 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellerton, W. The human and machine, 2022–2023: Open AI, ChatGPT, QuillBot, Grammarly, Google, Google Docs & humans. Visible Lang. 2023, 57, 38–52. [Google Scholar]

- Alshammari, S.M.; Alshammari, M.H. Optimising listening skills: Analysing the effectiveness of a blended model with a top-down approach through cognitive load theory. MethodsX 2024, 12, 102630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, M.M.S. Using self-regulated learning supported by artificial intelligence (AI) chatbots to develop EFL student teachers’ self-expression and reflective writing skills. Acad. J. Fac. Educ. Assiut Univ. 2024, 40, 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- Marzuki; Widiati, U.; Rusdin, D.; Darwin; Indrawati, I. The impact of AI writing tools on the content and organization of students’ writing: EFL teachers’ perspective. Cogent Educ. 2023, 10, 2236469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzubi, A.A.; Nazim, M.; Ahamad, J. Examining the effect of a collaborative learning intervention on EFL students’ English learning and social interaction. J. Pedagog. Res. 2024, 8, 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, F.S.; Ozdamli, F. A systematic literature review of soft skills in information technology education. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xu, J. Exploring the impact of AI-driven language learning apps on second language acquisition: Insights from college EFL learners. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 876. [Google Scholar]

- Alahmari, A.; Alhabbad, A.A.; Alshamrani, H.A.; Almuqbil, M.A. Effectiveness of social skills training interventions for children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Saudi Med. J. 2025, 46, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.D.; Chen, Y. The role of AI in academic writing: Impacts on writing skills, critical thinking, and integrity in higher education. Societies 2025, 15, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L’Enfant, J. AI as a reflective coach in graduate ESL practicum: Activity theory insights into student-teacher development. Eur. J. Open Distance E-Learn. 2024, 26, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).