Abstract

Does position matter? In many respects, it certainly does, but does it also matter in the case of a functional group such as 4-diethylaminophenyl in the structure of phenanthro[9,10-d]imidazole derivatives? We attempt to answer this question in this article by considering selected physicochemical properties of the presented compounds. Therefore, in this work, four phenanthro[9,10-d]imidazole derivatives (AM-0–AM-3) were obtained by Debus-Radziszewski condensation. All derivatives were purified, and their structures were confirmed using NMR spectroscopy. The synthesized compounds were then compared for their thermal, electrochemical, and optical properties. This demonstrated that the derivatives (AM-0 and AM-1) containing a 4-diethylaminophenyl substituent at the C2 position exhibit better physicochemical parameters than the other compounds, particularly in terms of thermal stability, energy gap, and even quantum yield. In the case of the latter parameter, derivatives containing 4-diethylaminophenyl at the C2 position show an increase of up to 15–30% (depending on the solvent used) compared to the compound containing the considered substituent at N1. The obtained research results were compared with DFT calculations to gain a deeper understanding of the experiments performed.

1. Introduction

Intensive technological development means that the requirements placed on chemical compounds used in practice are constantly increasing. This applies not only to the price and purity of the chemicals under consideration, but also, in particular, to the expected physicochemical properties. This trend is largely observed in organic electronics. This field of science and technology currently places particular requirements on chemical compounds in terms of their physicochemical properties. This often results from the fact that the better the physicochemical parameters of a chemical compound, the better the application for which it was designed. A prime example of this type is structural elements whose operation is based on the phenomenon of electroluminescence, such as organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) [1,2,3,4,5] and light-emitting electrochemical cells (LECs) [6,7,8,9,10]. To a large extent, the final parameters of OLEDs and LECs depend on the chemical compounds used in the individual layers, with particular emphasis on the emissive layer. In recent years, great hopes have been placed on emitters based on organic compounds. This is mainly due to the numerous advantages of such derivatives, including repeatable and efficient synthesis, a precisely defined structure that can be achieved using a variety of available methods, extensive processability thanks to excellent solubility in organic solvents, and the ability to modify physicochemical properties (at the synthesis stage) through the appropriate selection of substituents.

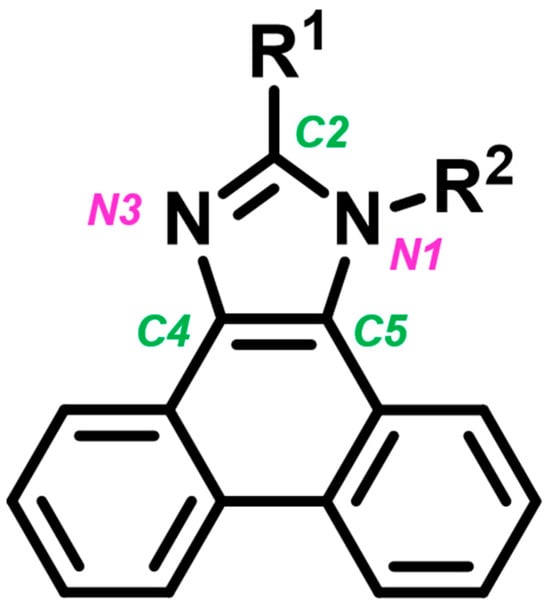

An example of chemical compounds that have been intensively studied in recent years for use as emitters in OLEDs and LECs is phenanthro[9,10-d]imidazole derivatives [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33]. In the case of these molecules, the heterocyclic imidazole ring core is connected to two substituents at the N1 and C2 positions, as well as three aromatic rings in the phenanthrene system (attached to the core through the C4 and C5 positions)—Figure 1. The appropriate selection of substituents enables the tailoring of the physicochemical properties of the compounds to meet the specific needs of various applications. As a result, many phenanthro[9,10-d]imidazole derivatives have been described in the literature, demonstrating high thermal stability and excellent electrochemical, optical, and electroluminescent properties, which are beneficial for use in OLEDs and LECs [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33].

Figure 1.

Structure of phenanthro[9,10-d]imidazole derivatives with numbering of the central imidazole ring, which is the core of the molecule.

However, the vast majority of phenanthro[9,10-d]imidazole derivatives described in the literature differ in the substituent at the C2 position [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33]. The indicated structural fragment is introduced into the structure of the final molecule via an aldehyde used as a substrate in the Debus-Radziszewski condensation reaction [15,16,18,19,20,22,26,28,29,32,33]. The wide selection of commercially available and synthetically advantageous aldehydes makes it easy to obtain a wide range of compounds, differentiated by their C2 position. In contrast, the N1 substituent is introduced by using an amine [15,16,18,19,20,22,26,28,29,32,33,34]. This is significantly more difficult, as the selection of commercially available and easily synthesized amines is considerably smaller than that of aldehydes. Furthermore, the reactivity of amines in the Debus-Radziszewski condensation reaction varies considerably. Therefore, the question arises: which of the considered positions (C2 and N1) will be more advantageous in terms of introducing a selected substituent or functional group that modifies physicochemical properties?

Therefore, in the research described in this article, we attempted to compare selected physicochemical properties of phenanthro[9,10-d]imidazole derivatives differing in the position of the 4-diethylaminophenyl substituent at the N1 and C2 positions (AM-1 and AM-2). The results were enriched by a comparison with two phenanthro[9,10-d]imidazole derivatives serving as reference systems. The first is a derivative (AM-0) containing a 4-diethylaminophenyl substituent at C2 and an N-H moiety at the N1 position. The second is 1,2-diphenyl-1H-phenanthro[9,10-d]-imidazole (AM-3), a derivative containing phenyl substituents at the N1 and C2 positions. All compounds were compared for their thermal, electrochemical, and optical properties. The aim was to determine the effect of the 4-diethylaminophenyl substituent on the final physicochemical properties of phenanthro[9,10-d]imidazole derivatives. Also, it allowed us to determine which position, N1 or C2, of the 4-diethylaminophenyl group has a more favorable effect on the expected properties from the perspective of using phenanthro[9,10-d]imidazole derivatives in OLEDs and LECs.

2. Experimental Section

All details concerning the chemicals, materials, apparatus, experimental procedures and DFT calculations are provided in the Supporting Information (SI). The SI also includes NMR spectra, TGA thermograms, voltammograms, absorption and emission spectra of the compounds.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Synthesis

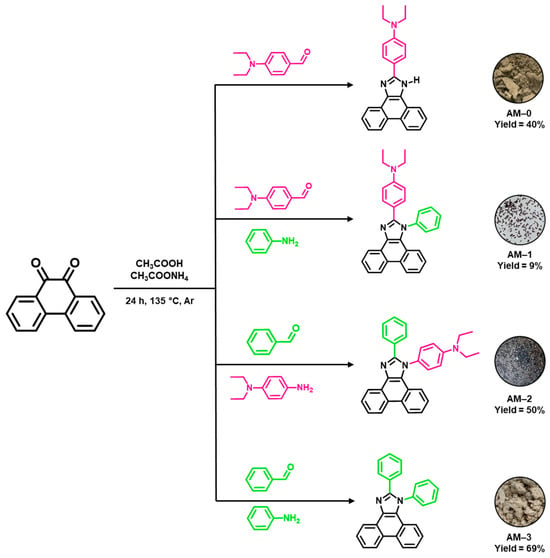

All syntheses were performed based on the one-step Debus-Radziszewski condensation reaction [15,16,18,19,20,22,26,28,29,32,33]. In this method, mixing a diketone, an aldehyde, and an amine in an acidic medium leads to the formation of an imidazole derivative. The aldehyde introduces a substituent at the C2 position into the molecular structure. A suitably selected amine, in turn, provides the N1 substituent. If only the diketone, aldehyde, and ammonium acetate are used in the reaction, a hydrogen atom (N-H group) will be present at the N1 position of the resulting imidazole. In this work, four phenanthro[9,10-d]imidazole derivatives (AM-0, AM-1, AM-2, AM-3) were obtained, differing in the substituents at the C2 and N1 positions. For this purpose, 9,10-phenanthroquinone, the appropriate aldehyde (benzaldehyde or 4-diethylaminobenzaldehyde), amine (aniline or N,N-diethyl-p-phenylenediamine), and ammonium acetate were used in the reaction (Figure 2). The reaction medium was acetic acid. The syntheses were carried out at the boiling point of the reaction mixtures, under an argon atmosphere. After 24 h, the obtained precipitates were precipitated in water and filtered on filter paper. The residual ammonium acetate and acetic acid were removed by washing the precipitates with distilled water. To purify compounds AM-1, AM-2, and AM-3, column chromatography and crystallization in methanol were performed. Compound AM-0 was purified by double crystallization in methanol. As a result, four phenanthro[9,10-d]imidazole derivatives were obtained in yields ranging from 9 to 69% (Figure 2). The structures of the obtained compounds were confirmed by NMR spectroscopy (1H and 13C). Detailed experimental procedures and NMR spectra are provided in the Supporting Information (Sections S3 and S4).

Figure 2.

Synthesis of compounds AM-0–AM-3 with yields and photographs of the powders.

3.2. Thermal Properties

To investigate the thermal properties of the obtained molecules, thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed and melting points were measured. Based on the conducted studies, 5% and 10% mass loss (T5, T10), decomposition temperatures (Tmax), and melting points of the tested compounds (Tm) were determined—Table 1. Thermograms of the tested compounds are provided in the Supporting Information (Figure S1). Of the analyzed compounds, the AM-0 derivative exhibits the highest thermal stability, as evidenced by a 5% mass loss occurring only at 312 °C. Comparison of the AM-0 and AM-1 derivatives, which share the same structural fragment, 4-diethylaminophenyl at the C2 position, enables an assessment of the effect of the substituent at the N1 position. Introduction of a phenyl group at N1 (AM-1) results in a decrease in thermal stability—a 5% mass loss is observed already at 289 °C. Compounds AM-2 and AM-3, which contain a phenyl group at the C2 position, enable a similar comparison of the effect of substituents at the N1 position. In this case, the AM-2 derivative with the 4-diethylaminophenyl group exhibits higher stability. For AM-3 (with the phenyl group at the N1 position), a 5% mass loss occurs at 257 °C, making it the least stable compound among the derivatives studied. Based on the analysis, it can be concluded that the presence of the 4-diethylaminophenyl group at both the C2 and N1 positions promotes increased thermal stability of the compounds. Notably, the substituent at the C2 position has a greater impact on thermal stability—the 4-diethylaminophenyl substituent (AM-1, T5 = 289 °C) at this position provides higher stability than the phenyl substituent (AM-2, T5 = 283 °C). For all derivatives, complete decomposition occurs above 300 °C—the highest Tmax is observed for AM-2 (379 °C) and the lowest for AM-3 (347 °C). Melting was also observed for each compound in the range of 186–312 °C. The melting point decreased in the series AM-0 > AM-1 > AM-3 > AM-2.

Table 1.

Thermal parameters of the tested compounds.

3.3. Redox Behavior

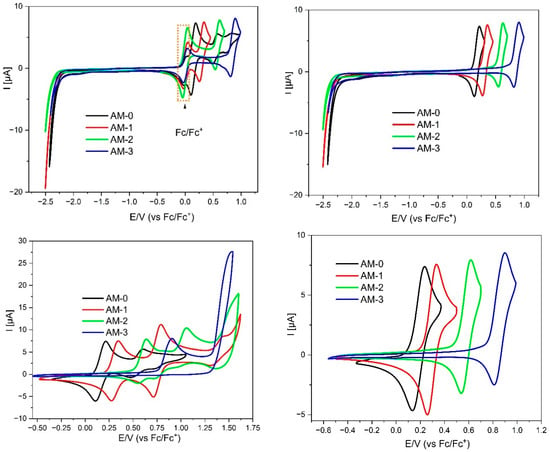

The next stage of the research was a series of measurements using the differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) and cyclic voltammetry (CV) method which were used to study the electrochemical properties of dissolved substances. DPV is a sensitive technique in which a series of voltage pulses is superimposed on potential stair steps. Thus, only the faradaic current is examined, which allows for accurate redox analysis of the tested samples. CV measures the electric current flowing through the electrochemical system in response to a linearly changing potential of the working electrode, which in turn enables the study of the thermodynamics of electrode processes. These measurements allow the determination of ionization potential (IP), electron affinity (EA), and energy gap (Eg) of the investigated compounds (assuming the IP of ferrocene equals −5.1 eV [34]. This, finally, allows us to calculate the energy band gap (Eg), which is the key value. Representative voltammograms showing the redox behavior of the compounds are shown below. All of the reduction and oxidation voltammograms obtained during the research were placed in SI (Figure S2). Additionally, a summary table detailing the electrochemical properties is provided below (Table 2).

Table 2.

Data obtained from electrochemical measurements.

The first part of the electrochemical studies began with the analysis of the redox properties of the molecules using the DPV method. All derivatives underwent the oxidation process at relatively low potentials—i.e., below 1V—confirming the high electron density within the molecules and their potential for being p-doped. The precise Eox values varied significantly depending on the type of substituents, both at the C2 and N1 positions. This indicates that oxidation is localized to (or involves a significant contribution from) the imidazole moiety. The lowest Eox value was measured for the AM-0 derivative (i.e., 0.08 V), which contains an N-H bond. This bond is highly polarized—the hydrogen is somewhat acidic (as confirmed by 1H NMR analysis). Therefore, the electron density is shifted to the imidazole ring, stabilizing the oxidized forms. Bearing this in mind, it is easy to predict that the AM-3 derivative undergoes oxidation at the highest potential—it has two phenyl substituents (both at the N1 and C2 positions), which have the weakest electron-donating properties. In contrast, the AM-1 and AM-2 derivatives (having a phenyl substituent in one position and a p-aniline substituent in the other), resulting in oxidation rates intermediate between those observed for AM-0 and AM-3. However, it is worth noting that substitution at the C2 position has a more favorable effect on the stabilization of oxidized forms than substitution at the N1 position.

Most importantly, the first oxidation state for this group of compounds is fully thermodynamically reversible (Figure 3). Additionally, (except for the AM-3 derivative), the second oxidation state is also reversible. This demonstrates excellent p-doping properties, as well as the fact that the molecules can, to some extent, act as hole conductors, for example, in an LEC device.

Figure 3.

Cyclic voltammograms of the investigated compounds with sweep rate ν = 100 mV/s, 0.1 M Bu4NPF6 in CH2Cl2.

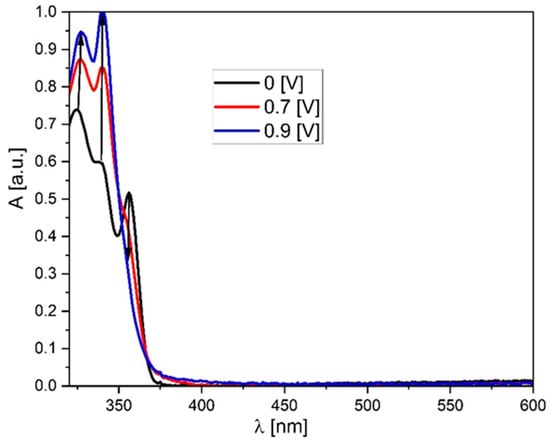

In turn, analyzing the properties of the molecules during reduction, they behave quite similarly (all of them were reducing below −2.25 V), which is typical for the phenantorimidazole core [35]. Taking both these values (Eox and Ered) into account, the electrochemical energy gap can be calculated—it lies between 2.33 eV (AM-0) and 3.11 eV (AM-3). This value is slightly lower than the energy gap determined by UV-VIS absorption spectroscopy, indicating that the HOMOs and LUMOs are (at least partially) separated in space. Spectroelectrochemical measurements were also performed for the studied compounds. As can be seen in Figure 4, the appearance of the absorption band changes after oxidation. Initially, three local minima can be distinguished at 325, 339, and 356 nm. However, after oxidation, the lowest energy band disappears, and the other bands increase, with the middle band becoming the most intense. What is crucial, however, is that after dedoping (i.e., the molecule returns to its neutral form), the spectrum returns to its original shape, further demonstrating the high stability and reversibility of oxidation. It is also worth noting that the absorption region remains unchanged—oxidation does not produce additional bands that could negatively impact the performance of OLED or LED devices built using this group of compounds.

Figure 4.

UV-Vis spectroelectrochemistry of the AM-0 derivative in DCM solution (c = 1 × 10−4 mol/L, as an inset on the graph potentials vs. Fc/Fc + redox couple).

3.4. DFT Calculations

To better understand how the position of substitution affects the properties of the presented compounds, DFT calculations were performed. Geometry optimization of the AM-0–AM-3 derivatives was performed using density functional theory (DFT) calculations at the PBE0/def2TZVP level, implemented in the Gaussian 16 software package. Transition energies and oscillator strengths of the compounds were calculated using a time-dependent DFT (TD-DFT) approach.

Looking at the structures of the presented compounds, one might get the impression that they are similar. AM-0 and AM-1 have the same substituent (4-diethylaminophenyl) at the C2 position. However, they differ in the substitution at the N1 position. Analyzing the dihedral angles between the 1H-phenanthro[9,10-d]imidazole plane and the substituent at the C2 position, a significant difference can be observed between these compounds. AM-0 exhibits a practically planar conformation (Figure S3), which may result in substantial fluorescence quenching at high compound concentrations, e.g., in pure layers [36]. AM-1, having a phenyl group at the N1 position, is not planar. This compound exhibits a distorted molecular geometry due to two torsion angles between the core plane and the C2 substituent (33°) and the phenyl ring at the N1 position (77°) (Figure S3). The twisted geometry of the compound may prevent the molecules from tightly packing at increased concentrations, resulting in suppressed fluorescence quenching in pure layers [36,37]. However, when we compare AM-1 to compound AM-3, we observe a certain similarity between them. AM-3 also does not have a planar conformation, and the dihedral angle between the phenyl group in N1 and the molecular core is the same. Changing the substituent at the C2 position does not affect this angle. Interestingly, the phenyl substituent attached at the C2 position increases the torsion angle (between C2 and the core) in the final structure of the compound compared to the 4-diethylaminophenyl fragment. Considering AM-2, the substituent reciprocal of AM-1, one can observe an increase in the dihedral angle between the N1 planes and the core compared to AM-1. Inserting the 4-diethylaminophenyl substituent at the N1 position decreases the torsion angle between C2 and the core compared to AM-3 (Figure S3). In the case of AM-1, AM-2, and AM-3, the core of the molecule is relatively well coupled to the substituents at the C2 position, which lie on the same axis, but due to the large angles, it exhibits weaker electronic communication with the pendant units at the N1 position. Analysis of the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) showed that for AM-0, AM-1, and AM-3, this orbital was distributed throughout the molecule (except the highly twisted phenyl moiety attached to the N1 position in AM-1 and AM-3). The 1H-phenanthro[9,10-d]imidazole core of AM-1 and AM-3 is well coupled to the substituents attached at the C2 position, which lie on the same axis. However, it exhibits weak electronic communication with the pendant unit at the N1 position. The HOMO of AM-2 was dominated primarily by the orbitals of the 4-diethylaminophenyl moiety located at the N1 position. Moreover, the HOMO also encompasses orbitals originating from the core and the phenyl moiety on the same axis. In the case of this molecule, the strong torsion angle did not constitute a barrier to electron flow. As can be seen in Figure S4, the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) for AM-2 and AM-3 encompasses the entire molecule, except for the motifs at the N1 position. Completely opposite behavior was exhibited by molecules possessing a substituent with pronounced electron-donating properties (AM-0 and AM-1). These compounds were characterized by a shift in the LUMO toward the 1H-phenanthro[9,10-d]imidazole core. Literature reports confirmed this behavior [36,37,38,39,40,41,42]. Electron affinity and ionization potential were calculated for all derivatives (Table 3). These values are close to the energies of the frontier orbitals. Compounds with an electron-rich substituent at the C2 position destabilized the HOMO the most. Also, they exhibited the greatest ability to undergo reduction processes (Table 3). The energy gap, calculated from the difference between the IP and EA values, ranged from 3.56 eV to 3.90 eV. The trend of the energy gap results is consistent with the energy gap obtained from electrochemical measurements.

Table 3.

Data obtained from DFT calculations.

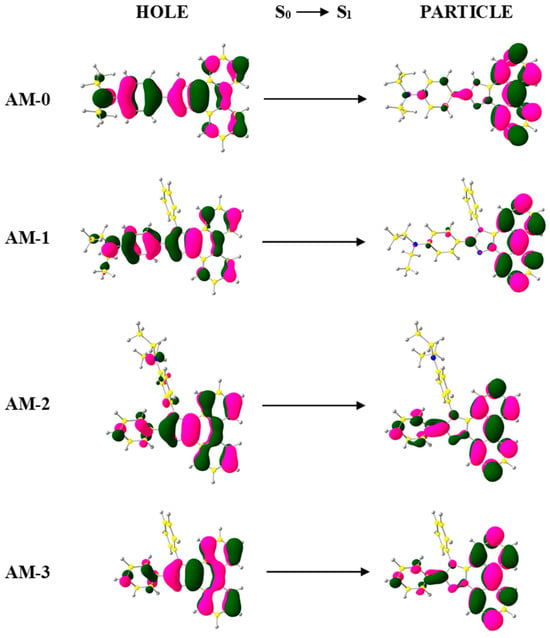

Furthermore, excited-state properties were calculated using TD-DFT (Figure S5 and Table S1). Analysis of natural transition orbitals (NTO) showed that the S0→S1 transition for AM-3 exhibits predominantly locally excited (LE) character due to the completely overlapping “holes” and “particles” (Figure 5). Interestingly, for AM-2, the “hole” wave functions encompassed the entire molecule, while the “particles” were located on the main axis of the compound, giving the AM-2 transitions an LE character. For AM-0 and AM-1, this transition may have an HLCT character, as partial orbital separation is observed between the “hole” and “particle” wave functions (Figure 5) [38,39]. The optical gaps determined from TD-DFT calculations were in the range of 3.15–3.50 eV, which corresponded to the actual results.

Figure 5.

The S0→S1 transition NTO of AM-0–AM-3.

3.5. Optical Properties

The optical absorption and fluorescence properties of compounds AM-0–AM-3 were assessed by UV/Vis absorption and photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy in dilute solutions (at a concentration of 2.5 × 10−5 mol/L) of six solvents with different dielectric constants. The obtained spectra are presented in the Supplementary Materials (Figures S6 and S7), and the detailed photophysical data are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Optical properties of AM-0–AM-3 derivatives.

The properties of the presented derivatives AM-0 to AM-3, observed in dilute solutions at low concentrations of the compounds, allowed for the revelation of the influence of intramolecular mechanisms. The recorded spectra for AM-2 and AM-3 exhibited similar absorption profiles, with the lowest energy band peak having a maximum value of approximately 360 nm (Figure S7). The bands in this range can be assigned to π − π* transitions originating from the 1H-phenanthro[9,10-d]imidazole core [43]. It is worth emphasizing that changing the substituent at the N1 position did not significantly affect the shape or the maximum absorption value. Compounds AM-0 and AM-1 with the 4-diethylaminophenyl substituent showed a spectrum with a clearly broadened lowest energy absorption band. This may indicate electron flow from the donor to the acceptor in these molecules. Furthermore, for AM-0 and AM-1, an increase in the molar absorption coefficient was observed, which is typical for D-A molecules and results from an increased transition dipole moment [36]. In terms of absorption studies, no solvatochromic effect was observed. The emission curves for compounds AM-2 and AM-3 show minor differences in shape and position. The emission maxima with strong violet photoluminescence (PL) are in the range of 365–390 nm. The excitation character of both derivatives can be assigned to a locally excited state [43]. This is indicated by the fine structure of the spectra of both compounds (Figure S6). AM-2 and AM-3 do not exhibit a solvatochromic effect upon excitation. Interestingly, in this case, the N1 position did not significantly influence the position of the band maxima. For AM-2 with a 4-diethylaminophenyl substituent at the N1 position, a distortion of the vibronic structure was observed in solvents with a higher dielectric constant. AM-0 and AM-1 are significantly bathochromically shifted upon excitation relative to AM-2 and AM-3 (Figure S7). Also, their emission spectra showed deep blue emission with a maximum above 400 nm. Solvent polarity in the case of AM-0 and AM-1 significantly affects the excited emission states. With increasing solvent polarity (toluene → DMSO), a red shift was observed. Initially, emission with a vibrational band structure was observed in toluene. This indicates that the excited states of these molecules in a nonpolar solvent are LE states [42]. With increasing solvent polarity, the double-peak emission gradually decreased and finally turned into single-peak emission (Figure S6). This may indicate a gradual transition to the HLCT state. The single-peak emission occurring in high-dielectric solvents may be caused by the influence of intramolecular charge distribution and intermolecular interactions by solvent polarity [41]. Fluorescence quantum yields (QY) for AM-0 and AM-1 ranged from 0.20 to 0.41. Such high quantum yields may be due to the HLCT nature of these molecules. As is well known, compounds exhibiting this characteristic benefit from both LE and CT processes. Moreover, the AM-1 derivative with a phenyl substituent at the N1 position showed higher quantum yields than AM-0. This may be due to the inability of the substituent to form hydrogen bonds with the imidazole ring and the less rigid structure of this compound (Figure S3). Compounds AM-2 and AM-3 showed lower QY than AM-0 and AM-1. Of the entire group, AM-2 was characterized by the lowest QY values (Table 4). This is most likely due to the presence of the 4-diethylaminophenyl group at the N1 position. The structure of this compound is unfavorable in terms of charge transfer (the HOMO is located on the N1 substituent, and the LUMO is located on the core of the molecule).

4. Conclusions

The primary goal of this study was to determine the effect of the 4-diethylaminophenyl substituent at the N1 and C2 positions on selected physicochemical properties of phenanthro[9,10-d]imidazole derivatives. Therefore, four compounds (AM-0–AM-3) were obtained, differing in terms of the substituents at the considered positions. Analyzing the thermal properties of the studied derivatives, we observe that the 4-diethylaminophenyl group has a favorable effect on thermal stability compared to the phenyl substituents. Derivatives with the 4-diethylaminophenyl substituent at the C2 position (AM-0–AM-1) exhibit better thermal parameters, particularly when the N1 position contains only an N-H moiety (AM-0). Electrochemical properties of the studied compounds revealed that substitution of phenanthro[9,10-d]imidazole at the C2 position with a 4-diethylaminophenyl group had a more favorable effect on the stabilization of oxidized forms than substitution with a phenyl group. Additionally, the choice of the substituent at the N1 position also plays a role during the oxidation process. AM-0 with an N-H motif at the N1 position underwent this process most readily. Absorption and emission properties were strongly related to the substituents at the C2 position. Their absorption profiles and maxima were similar in the AM-2–AM-3 and AM-0–AM-1 pairs. It is worth emphasizing that changing the substituent at the N1 position did not significantly affect the shape or maximum absorption value. Emission studies showed that compounds with a 4-diethylaminophenyl substituent at the C2 position were more red-shifted. Furthermore, these compounds exhibited solvatochromism. Substitution at the N1 position did not affect the emission maxima values. The modification of the N1 group in the described compounds affected the QY values. Considering the same emission character in the AM-0/AM-1 and AM-2/AM-3 pairs, the N1 substituent played a role in stiffening the structure or withdrawing electrons, which resulted in an increase or decrease in QY. To sum up, a detailed analysis of the physicochemical properties of the tested molecules (AM-0–AM-3) with particular emphasis on parameters such as thermal stability, energy gap and quantum efficiency showed that the suitability of the considered compounds for further application studies in OLEDs is classified as follows: AM-1 > AM-0 > AM-3 > AM-2.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ma19010055/s1. Figure S1. TGA thermogram—thermal properties of AM-0–AM-3 series. Figure S2. Differential pulse voltammetry and cyclic voltammograms of AM-0–AM-3 with sweep rate ν = 100 mV/s, 0.1 M Bu4NPF6 in CH2Cl2. Figure S3. Dihedral angle between the C2 or N1 substituent and the central core of 1H-phenanthro[9,10-d]imidazole for AM-0–AM-3. Figure S4. Contours of HOMO and LUMO orbitals for AM-0–AM-3. Figure S5. Experimental (pink line) absorption spectra and calculated transitions (black sticks) of AM-0–AM-3 in dichloromethane. Table S1. Electronic transition energies assigned to the lowest absorption bands of the AM-0–AM-3 wavelengths. Figure S6. Absorption and emission spectra in different solvents for AM-0–AM-3. Figure S7. Comparison of absorption and emission spectra for AM-0–AM-3.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K.; methodology, A.K., M.F. and S.K.; validation, A.K., M.F. and S.K.; investigation, A.K., M.F. and S.K.; resources, S.K.; data curation, A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K., M.F. and S.K.; writing—review and editing, A.K., M.F. and S.K.; visualization, A.K., M.F. and S.K.; supervision, S.K.; project administration, S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Calculations have been carried out using resources provided by Wroclaw Centre for Networking and Supercomputing (http://wcss.pl) (SCCESSED ON 14 November 2025) grant No. 18.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Keerthika, P.; Nutalapati, V.; Konidena, R.K. A Guide to Mastering Multi-Resonance Thermally Activated Delayed Fluorescence: From Challenges to Strategies for High-Performance OLEDs. J. Mater. Chem. C 2025, 13, 17416–17457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, B.; Zhou, J.; Duan, C.; Xu, H. Blue Multiple-Resonance Thermally Activated Delayed Fluorescence Materials. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2025, 13, 2403295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, A.; Utochnikova, V.; Zhu, Y.; Meng, H. Chemical Strategies for Modifying Carbonyl/Nitrogen-Based MR-TADF Materials toward Narrowband Emission. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2025, 13, e01289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Su, S.-J. Recent Advances in Highly Efficient Small-Molecule TADF Emitters for Solution-Processed OLEDs. J. Mater. Chem. C 2025, 13, 19909–19926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Lv, Y. Recent Advances of Aromatic Cyclic Imide/Amide Acceptors in Thermally Activated Delayed Fluorescent Materials for Organic Light-Emitting Diodes. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2025, 13, e01835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, V.; Bizzarri, C.; Bräse, S. Thermally Activated Delayed Fluorescence (TADF) Materials Based on Earth-Abundant Transition Metal Complexes: Synthesis, Design and Applications. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2404866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.; Gao, A.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Xiong, W.; Xu, Y.; Meng, L.; Dang, D. Recent Advances of Organic Emitters in Deep-red Light-emitting Electrochemical Cells. Luminescence 2024, 39, e4657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahary, R.; Rabiei, M.; Nasiri, S.; Padgurskas, J.; Rukuiza, R. Overview on the Thermally Activated Delayed Fluorescence and Mechanochromic Materials: Bridging Efficiency and Versatility in LECs and OLEDs. Materials 2025, 18, 2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlingman, K.; Chen, Y.; Carmichael, R.S.; Carmichael, T.B. 25 Years of Light-Emitting Electrochemical Cells: A Flexible and Stretchable Perspective. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2006863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawiec, A.; Szłapa-Kula, A.; Kula, S. 1H-Imidazo [4,5-f][1,10]Phenanthroline Derivatives as Promising Ligands for Ir and Ru Complex Compounds for Applications in LECs: Mini-Review. Materials 2025, 18, 4380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.-N.; Liu, J.; Li, G.; Zhao, B. Efficient deep blue fluorescent emitters based on bipolar phenanthroimidazole-carbazole hybrid for non-doped electroluminescent device with small CIEy. Dye. Pigment. 2024, 222, 111885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavgeniene, D.; Blazevicius, D.; Kirstukas, M.; Krucaite, G.; Kazlauskas, K.; Banevicius, D.; Jankauskas, V.; Kamarauskas, E.; Grigalevicius, S. Phenanthro[9,10-d]imidazole having electroactive derivatives as potential host materials for third generation organic light emitting diodes. Synth. Met. 2025, 311, 117822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akshaya, M.; Gayathri, R.; Imran, P.M.; Nagarajan, S. Exploring Single Atom Substitution In Phenanthro[9,10-d]Imidazole -Based D–π–A Architectures with Fluorene and its Heteroanalogs for Non-Volatile Resistive WORM Memory Device Applications. Chem. Eur. J. 2025, 31, e202404337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathirvelan, D.; Mayakrishnan, S.; Uma Maheswari, N.; Biswas, C.; Raavi, S.S.K.; Panda, T.K. A Simple D–π–A System of Phenanthroimidazole-π-Fluorenone for Highly Efficient Non-Doped Bipolar AIE Luminogens: Synthesis, and Molecular Optical, Thermal and Electrochemical Properties. New J. Chem. 2020, 44, 1785–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Wu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, S.; Zhao, X.; Liu, H.; Dong, X.; Wang, S.; Li, X. Achieving Non-Doped Deep-Blue OLEDs by Applying Bipolar Imidazole Derivatives. Org. Electron. 2019, 69, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-C.; Yuan, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Rogach, A.L.; Tong, Q.-X.; Lee, C.-S. Aromatically C6- and C9-Substituted Phenanthro[9,10-d]Imidazole Blue Fluorophores: Structure–Property Relationship and Electroluminescent Application. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 26268–26278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.-Y.; Liu, B.; Zhao, J.-W.; Ruan, G.-L.; Tao, S.-L.; Tong, Q.-X. Bipolar Deep-Blue Phenanthroimidazole Derivatives: Structure, Photophysical and Electroluminescent Properties. Org. Electron. 2018, 52, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Fang, D. Deep Blue Organic Light-Emitting Devices Enabled by Bipolar Phenanthro[9,10-d]Imidazole Derivatives. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 72009–72018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayabharathi, J.; Prabhakaran, A.; Thanikachalam, V.; Jeeva, P. Efficient Non-Doped Blue Emitting Devices Based on Bis(Phenanthrimidazolyl)Biphenyl Derivatives. New J. Chem. 2016, 40, 8768–8777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanikachalam, V.; Sarojpurani, E.; Jayabharathi, J.; Jeeva, P. Efficient Phenanthroimidazole-Styryl-Triphenylamine Derivatives for Blue OLEDs: A Combined Experimental and Theoretical Study. New J. Chem. 2017, 41, 2443–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Liu, H.; Liu, F.; He, X.; Xu, X.; Chen, J.; Peng, Q.; Lu, P. Efficient Red Electroluminescence From Phenanthro[9,10-d]imidazole-Naphtho[2,3-c][1,2,5]Thiadiazole Donor-Acceptor Derivatives. Chem. Asian J. 2021, 16, 1942–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Xie, N.; Xu, Y.; Li, C.; Mu, X.; Wang, Y. Fluorine-Substituted Phenanthro[9,10-d]Imidazole Derivatives with Optimized Charge-Transfer Characteristics for Efficient Deep-Blue Emitters. Org. Mater. 2020, 02, 011–019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Tan, Y.; Liu, H.; Tang, X.; Gao, L.; Du, C.; Min, J.; Jin, H.; Lu, P. High-Efficiency near-Infrared Fluorescent Organic Light-Emitting Diodes with Small Efficiency Roll-off Based on AIE-Active Phenanthro[9,10-d]Imidazole Derivatives. J. Mater. Chem. C 2020, 8, 6883–6890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, J.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Liu, D.; Zhu, F.; Wang, Y.; Yan, D. High-Efficiency Non-Doped Deep-Blue Fluorescent Organic Light-Emitting Diodes Based on Carbazole/Phenanthroimidazole Derivatives. J. Mater. Chem. C 2020, 8, 10185–10190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, S.S.; Sree, V.G.; Gunasekar, K.; Cho, W.; Gal, Y.; Song, M.; Kang, J.; Jin, S. Highly Efficient Bipolar Deep-Blue Fluorescent Emitters for Solution-Processed Non-Doped Organic Light-Emitting Diodes Based on 9,9-Dimethyl-9,10-dihydroacridine/Phenanthroimadazole Derivatives. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2016, 4, 1236–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.-H.; Yao, J.-F.; Li, H.-Z.; Li, G.-Z.; Xie, F.-M.; Li, Y.-Q.; Hu, Y.-Y.; Tang, J.-X.; Zhao, X. New Strategy for Developing Deep Blue TADF Materials with Narrow Emission and CIEy < 0.06 Employing Host Materials as Donors. New J. Chem. 2023, 47, 3026–3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wei, J.; Song, X.; Ye, K.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y. Non-Doped Luminescent Material Based Organic Light-Emitting Devices Displaying High Brightness under Very Low Driving Voltage. J. Mater. Chem. C 2016, 4, 7013–7019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keerthika, P.; Kumar, A.; Selvaganesan, A.; Moon, J.; Nutalapati, V.; Lee, J.Y.; Konidena, R.K. Overcoming the 5% EQE Ceiling in Deep-Blue Fluorescent OLEDs with Hybridized Local and Charge Transfer Featured Phenanthroimidazole-Carbazole Emitters. J. Mater. Chem. C 2025, 13, 20540–20548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szlapa-Kula, A.; Kula, S. Progress on Phenanthroimidazole Derivatives for Light-Emitting Electrochemical Cells: An Overview. Energies 2023, 16, 5194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Li, J.; Man, X.; Liu, H.; Sun, X.; Liu, F.; Lu, P. Synthesis and Characteristics of Organic Red-Emissive Materials Based on Phenanthro[9,10-d]Imidazole. Chem. Asian J. 2019, 14, 821–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Mu, G.; Tan, J.; Lei, Z.; Jin, J.; Wang, L. Pyridine-Containing Phenanthroimidazole Electron-Transport Materials with Electron Mobility/Energy-Level Trade-off Optimization for Highly Efficient and Low Roll-off Sky Blue Fluorescent OLEDs. J. Mater. Chem. C 2015, 3, 7709–7719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Li, W.; Wei, D.; Wei, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, S.; Li, S.; Wei, B.; Cao, G.; Zhai, B. Synthesis, Photophysical and Electroluminescent Properties of Blue-Emitting Dual Core Imidazole–Anthracene/Pyrene Derivatives. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 60264–60270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiyasuan, C.; Chasing, P.; Nalaoh, P.; Wongkaew, P.; Sudyoadsuk, T.; Kongpatpanich, K.; Promarak, V. Twisted Phenanthro[9,10-d]Imidazole Derivatives as Non-doped Emitters for Efficient Electroluminescent Devices with Ultra-Deep Blue Emission and High Exciton Utilization Efficiency. Chem. Asian J. 2021, 16, 2328–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bujak, P.; Kulszewicz-Bajer, I.; Zagorska, M.; Maurel, V.; Wielgus, I.; Pron, A. Polymers for Electronics and Spintronics. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 8895–8999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kula, S.; Ledwon, P.; Maroń, A.M.; Siwy, M.; Grzelak, J.; Szalkowski, M.; Maćkowski, S.; Schab-Balcerzak, E. Synthesis, Photophysical Properties and Electroluminescence Characterization of 1-Phenyl-1H-Phenanthro[9,10-d]Imidazole Derivatives with N-Donor Substituents. Dyes Pigm. 2021, 192, 109437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanauskaite, A.; Lygaitis, R.; Raisys, S.; Kazlauskas, K.; Kreiza, G.; Volyniuk, D.; Gudeika, D.; Jursenas, S.; Grazulevicius, J.V. Structure–Property Relationship of Blue Solid State Emissive Phenanthroimidazole Derivatives. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 16737–16748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, W.; Yang, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Lam, J.W.Y.; Liang, G.; Kwok, H.S.; Tang, B.Z. Construction of Efficient Deep Blue Aggregation-Induced Emission Luminogen from Triphenylethene for Nondoped Organic Light-Emitting Diodes. Chem. Mater. 2015, 27, 3892–3901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, W.; Yao, L.; Pan, Y.; Shen, F.; Xiao, R.; Yang, B.; Ma, Y. Enhanced Proportion of Radiative Excitons in Non-Doped Electro-Fluorescence Generated from an Imidazole Derivative with an Orthogonal Donor–Acceptor Structure. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 11302–11304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Dong, G.; Wang, H.; Liu, J.; Chen, J.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, C. Novel Fluorescence Sensing of D-A Type Imidazole Derivatives to Fe3+ and Its Application on Rewritable Paper. J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 1307, 137977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, H.; Tan, H.-J.; Yang, L.; Qin, P.; Zheng, X.-H.; Tang, S.-S.; Liu, Y.; Tong, Q.-X. Rational Molecular Design of Multifunctional Blue-Emitting Materials Based on Phenanthroimidazole Derivatives. Chem. Eur. J. 2021, 27, 7275–7282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Zhu, S.; Liu, Y.; Shi, T.; Yang, L.; He, Y.; Niu, X.; Yang, Z.; Yuan, J.; Feng, Z. Hybridized Local and Charge-Transfer Excited States of Blue OLEDs Based on Phenanthroimidazole Derivates with a Narrow FWHM of 24 Nm. J. Mater. Chem. C 2024, 12, 14129–14138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yao, L.; Peng, Q.; Li, W.; Pan, Y.; Xiao, R.; Gao, Y.; Gu, C.; Wang, Z.; Lu, P.; et al. Achieving a Significantly Increased Efficiency in Nondoped Pure Blue Fluorescent OLED: A Quasi-Equivalent Hybridized Excited State. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2015, 25, 1755–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, F.C.; Spanggaard, H. An Exceptional Red Shift of Emission Maxima upon Fluorine Substitution. J. Org. Chem. 2002, 67, 7185–7192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.