Highlights

What are the main findings?

- MHBTZ exhibits excellent corrosion inhibition performance for pure iron and aluminum in aggressive acidic media.

- EIS results reveal very high inhibition efficiencies of 98.94% for Fe and 99.16% for Al at 2500 ppm.

- PDP measurements confirm that MHBTZ acts as a mixed-type inhibitor, suppressing both anodic metal dissolution and cathodic hydrogen evolution.

- Experimental findings are strongly supported by DFT and MD simulations, indicating robust interactions between the inhibitor and metal.

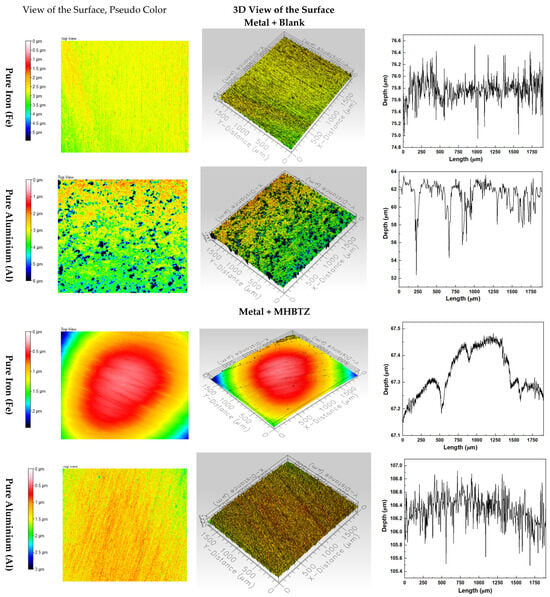

- 3D optical profilometry demonstrates the formation of a compact and protective film on Fe and Al surfaces in the presence of MHBTZ.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- MHBTZ can be considered a highly effective organic inhibitor for protecting Fe- and Al-based materials in acidic industrial environments.

- The combined experimental–computational approach provides reliable mechanistic insight into corrosion inhibition behavior.

- The high efficiency at relatively low concentration highlights the potential of MHBTZ for cost-effective and practical corrosion control applications.

Abstract

The influence of 5-Methyl-1H-benzotriazole (MHBTZ) on the corrosion of pure iron (Fe) and aluminum (Al) in 1 M HCl was investigated in this study. The experimental and theoretical aspects of MHBTZ adsorption onto pure iron (Fe) and aluminum metal (Al) surfaces, as well as the stability of adsorbed layers based on the metal type, were also studied. Different electrochemical measurements were performed to explore the corrosion rates and inhibition efficiencies on the Fe and Al surfaces at 298 K. Optical profilometry was used to obtain the 3D surface topography of Fe and Al metals after immersion with and without the MHBTZ molecule. The results showed that MHBTZ exhibited excellent inhibition properties for both metals. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) achieved inhibition efficiencies of 98.1% and 98.5% for Fe and Al, respectively, at a concentration of 2500 ppm. Potentiodynamic polarization (PDP) indicated that MHBTZ acted as a mixed-type inhibitor. Density functional theory (DFT) analysis and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were used to explore the relationship between the molecular structure of MHBTZ and its inhibition efficiency at the atomic level.

1. Introduction

Corrosion is a major challenge faced by the industrial sector, as it affects all areas of operation, especially in environments such as chemical processing, desalination, and oil and gas production. Acid corrosion can cause significant material damage during critical operations, such as industrial cleaning and descaling processes [1,2,3]. The use of HCl and other acids for scale removal creates problems because they break down metal substrates, which damages equipment structures and shortens operational periods [4,5]. The worldwide economic damage caused by corrosion is approximately USD 2.5 trillion each year, highlighting the need for successful protective methods [6,7].

Corrosion inhibition is one of the solutions used in industry to minimize the corrosion rates of metals and alloys at a low cost. Organic compounds serve as fundamental components in corrosion inhibition science because their performance can be enhanced by modifying their molecular structures and physicochemical properties [8,9,10]. The mechanism of action of these inhibitors is adsorption on metal surfaces, thus creating a protective layer that blocks corrosive electrolyte access. The most effective corrosion inhibitors function through chemisorption, forming dense and stable films by establishing strong covalent or coordinate bonds with the metal surfaces. The effectiveness of organic inhibitors depends on the presence of particular functional groups, including heteroatoms (N, S, O, and P) and π-systems (aromatic or heterocyclic rings) that serve as adsorption sites [8,11,12,13,14,15].

In recent years, numerous studies have been conducted to develop organic inhibitors that can target metal species. For carbon steel, which mostly contains 99% pure iron, a vast body of research work has explored compounds that can mitigate its high susceptibility to acid-induced corrosion [4,16,17,18,19,20,21]. Similarly, for aluminum alloys that contain 98% pure Al, several studies have investigated different corrosion inhibitors ranging from amines and hydrazine derivatives to Schiff bases and surfactants [7,22,23,24,25,26,27,28].

Previous studies have extensively documented the performance of various triazole derivatives as corrosion inhibitors for carbon steel and aluminum in acidic media [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38]. Research shows that specific derivatives reach up to 95% inhibition efficiency when evaluated against mild steel and aluminum alloys, but these experimental tests were conducted for individual metals with different sets of inhibitors [39,40,41,42,43,44,45].

In addition, the scientific literature indicates that information on the use of a corrosion inhibitor to protect multiple metals from corrosion during the acid cleaning process is scarce [38,46,47]. Therefore, this research is important because modern industrial operations require this capability as their production systems consist of assemblies that include multiple metal components.

This research investigates 5-Methyl-1H-benzotriazole (MHBTZ) as a dual-action molecule that demonstrates effective corrosion inhibition toward pure iron and aluminum in 1 M HCl solution. Electrochemical techniques combined with 3D optical profilometry analysis were employed to obtain inhibition efficiency and further confirm the adsorption of MHBTZ on the Fe and Al surfaces. Furthermore, DFT calculations at the GGA/PBE level and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were used to provide further understanding of the inhibition effect of MHBTZ at the molecular level.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Material and Solution

The preparation of the solutions required 5-Methyl-1H-benzotriazole (MHBTZ) and 1 Molar hydrochloric acid (1 M HCl). All reagents employed in this study were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich to ensure high analytical quality of the reagents. Test solutions were subsequently prepared at concentrations of 1000, 1500, 2000, and 2500 ppm MHBTZ solutions at room temperature (298 K). Corrosion experiments were conducted on the pure iron (Fe) and pure aluminum (Al) samples. Before each experiment, pure Fe and Al specimens were mechanically polished using successive grades of emery paper (400, 600, 800, and 1200 grit). Following the polishing procedure, the samples were thoroughly rinsed with distilled water to remove residual particles from the surface.

2.2. Electrochemical Measurements

Electrochemical studies were performed using a Gamry Interface 5000 E potentiostat/galvanostat (Gamry Instrument, Warminster, PA, USA). The working electrodes consisted of pure Fe and Al samples with a 0.5 cm2 exposed surface area. A saturated calomel electrode and graphite were used as the reference and the counter electrodes, respectively. The three-electrode system corrosion cell contained 150 mL of 1 M HCl solution, with and without the corrosion inhibitor. The experiments were first conducted for one hour at a steady state open-circuit potential (OCP) to ensure stability. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) analysis was subsequently performed with an AC signal with an amplitude of 10 mV at the OCP within a frequency range of 100 kHz to 0.1 Hz. This was followed by linear polarization resistance (LPR) measurements using a potential scan of ±0.1V relative to the OCP at a rate of 0.125 mV/s. Finally, potentiodynamic polarization (PDP) studies were obtained from −0.250 V to −0.25 V at OCP at a scan rate of 1.0 mV/s.

2.3. Computational Details

2.3.1. Microspecies Analysis of Mhbtz

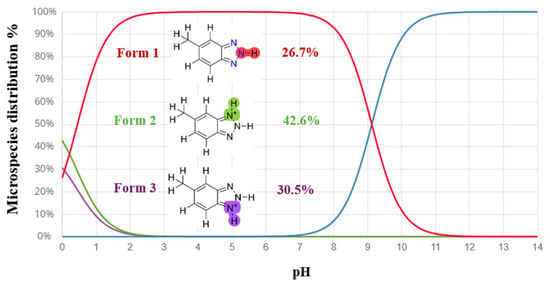

The major microspecies of MHBTZ as a function of pH were identified using Marvin Sketch software (https://chemaxon.com/marvinsketch_js, accessed on 16 November 2025) within a pH range of 0.0 to 14.0. For the theoretical calculations, the microspecies present at pH = 0 were selected, because experimental investigations were carried out under acidic conditions (1 M HCl). The analysis revealed that MHBTZ exists as three distinct microspecies at pH = 0. The relative distribution was estimated to be 26.7% for the neutral form (Form 1), along with protonated species (Form 2 (42.6%) and Form 3 (30.5%)). Representative microspecies at pH = 0 are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Distribution of MHBTZ forms as a function of pH.

2.3.2. Molecular Properties Calculations Using DFT Simulations

Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations were performed using the Dmol3 module in Materials Studio 17 to optimize the molecular geometry of MHBTZ. The Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) functional within the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) was employed to describe the electronic exchange and correlation potential, together with all-electron calculations using a double-numeric basis set with polarization functions (DNP) [48,49]. Geometry optimizations were performed without imposing symmetry constraints, and vibrational frequency analyses were performed to verify that the optimized structure corresponded to the true minimum on the potential energy surface. To account for solvent effects, the COSMO continuum solution model was applied using water as the medium. All calculations were conducted using the fine convergence criteria [50]. Based on frontier molecular orbital theory, electronic parameters such as the highest occupied molecular orbital energy (EHOMO), lowest unoccupied molecular orbital energy (ELUMO), and energy gap (ΔE) were subsequently evaluated

2.3.3. MD Simulations

The Forcite module in Materials Studio was employed to investigate the interaction between the inhibitor molecules and the metallic surfaces of iron and aluminum [51]. Initially, the primitive abc unit cells of Fe and Al were optimized to their lowest-energy configurations, after which supercells of Fe (110) and Al (111) with dimensions of 10 × 10 were constructed, each consisting of five atomic layers derived from the optimized unit cells. Using the “build layers” tool, a simulation slab was generated by introducing a solvent layer containing water molecules together with the inhibitor species on the Fe (110) and Al (111) surfaces. The constructed box with periodic boundary conditions had a size of 24.82 Å × 24.82 Å × 57.61 Å for Fe (110) and 28.63 Å × 28.63 Å × 53.04 Å for Al (111). The MD simulation used the COMPASS II force field at 298 K under NVT ensemble conditions with a total simulation time of 100 ps and a 0.1 fs time step. During the simulations, Fe and Al atoms were constrained to their bulk positions, while one inhibitor molecule, nine Cl− anions, nine H3O+ cations, and 491 H2O molecules were allowed to relax fully. The interaction energy (Eint) between the inhibitor and Fe (110) and Al (111) surfaces was evaluated using the following expression [52]:

2.4. Surface Analyses

3D Profilometry Spectroscopy

The surfaces of the two metals, with and without MHBTZ, were characterized using a Profilm3D optical profiler (Filmetrics, San Diego, CA, USA) fitted with a Nikon 50× DI objective lens (Nikon Corporation, Minato, Japan), providing high-resolution three-dimensional imaging. The surfaces of Fe and Al metals were analyzed after immersion in a 1 M HCl solution at 25 °C with and without 2500 ppm for 6 h.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. OCP Measurements

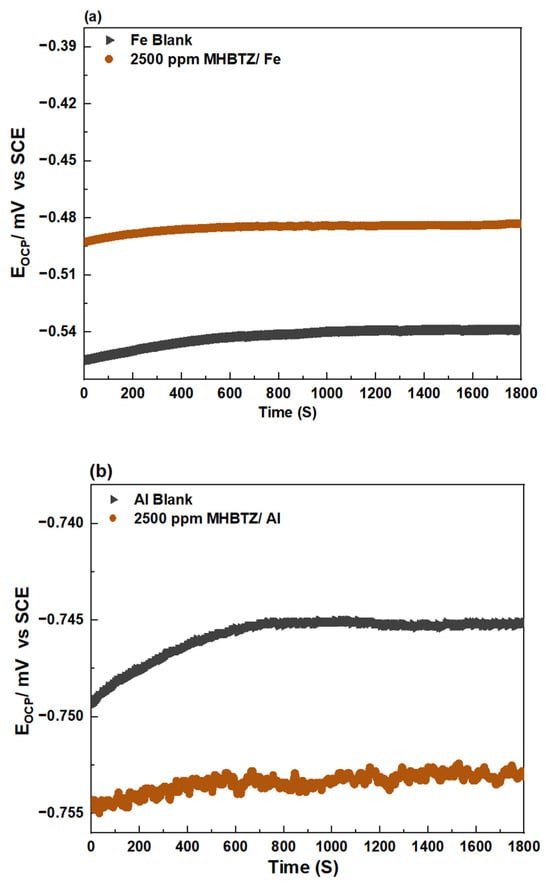

Measurement of the open-circuit potential over time is a crucial technique that must be performed before each electrochemical test to achieve reliable results. The OCP versus time plots in Figure 2 show the behavior of the blank solution and the solutions containing 2500 ppm of MHBTZ (the concentration of 2500 ppm presented in this figure is a representative plot only, as concentrations ranging from 500–2500 ppm were investigated in this study). The OCP reached a stable state during the time used in this work (half an hour for pure Fe and Al metals). The OCP values were −0.52 V vs. SCE for Fe and −0.749 V vs. SCE for Al in the blank solution, indicating active corrosion of the pure Fe and Al substrates. The Al metal showed a strongly negative potential upon immersion in HCl solution because of its strong tendency to corrode in acid when compared to Fe. With the introduction of the optimum concentration of the inhibitor (2500 ppm MHBTZ), Al exhibited cathodic behavior relative to the blank system, indicating a more pronounced inhibitory effect on cathodic hydrogen production. The noisy OCP of Al metal in the presence of the inhibitor arises from the dynamic adsorption–desorption of inhibitor molecules, unstable oxide/inhibitor film formation, and localized activation events on the aluminum surface. In contrast, for Fe corrosion, the addition of 2500 ppm of MHBTZ shifted the potential toward positive values until it reached approximately −0.48 V. The positive shift in the corrosion potential confirmed the role of the inhibitor in suppressing anodic Fe corrosion through adsorption onto its surface [46,53].

Figure 2.

OCP variation of (a) Pure Fe, (b) Pure Al electrodes in 1 M HCl solution with and without the 2500 ppm MHBTZ at 25 °C.

3.2. EIS Measurement

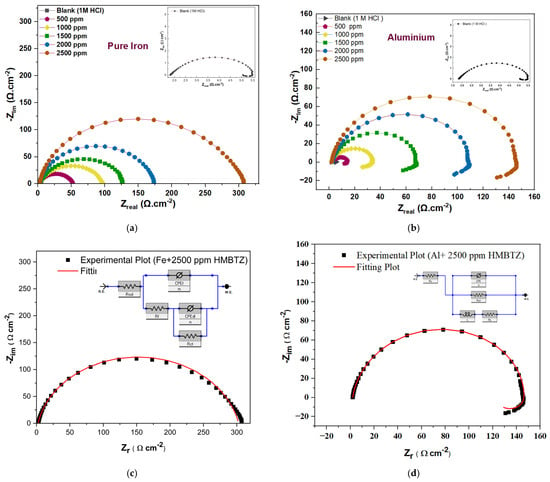

The Nyquist plots in Figure 3 display single depressed semi-circles, which stem from the Fe surface heterogeneity due to impurities and surface roughness, together with dislocations and other factors [54]. To achieve reliable results and match the experimental data, the equivalent circuit uses a constant phase element (CPE) instead of a capacitor because it allows the model to consider a depressed semicircular shape. In this case, the capacitive loops expanded with increasing MHBTZ concentration, indicating better corrosion inhibition effects. In this case, the polarization resistance (Rp) is the sum of the solution resistance (Rs), the film resistance (Rf) and charge transfer resistance (Rct).

Rp = Rs + Rf + Rct

Figure 3.

Nyquist plots of (a) Pure Fe, (b) Pure Al electrodes in 1 M HCl solution without and with different concentrations of MHBTZ at 25 °C. Representatives of an equivalent circuit suitable for EIS analysis of various metals of (c) pure iron and (d) aluminum at 2500 ppm.

The polarization resistance (Rp) represents the combination of the film resistance (Rf) and charge transfer resistance (Rct) because they were connected in series based on the equivalent circuit.

The Nyquist plots for aluminum displayed depressed semicircles that increased with increasing inhibitor concentration. However, aluminum showed inductive loops after capacitive loops, which led to the use of a different equivalent circuit for Al under the investigated conditions. The inductive behavior of aluminum in HCl is mainly attributed to the relaxation of adsorbed chloride-containing intermediates formed during oxide film breakdown and dissolution. It is also associated with localized depassivation, where coupled anodic dissolution and cathodic hydrogen evolution at corrosion fronts cause a delayed response. Additionally, time-dependent changes at the Al/solution interface can lead to an apparent low-frequency inductive loop in EIS spectra [55,56]. The polarization resistance (Rp) was calculated using Equation (4).

The charge transfer (Rct) and inductive resistances (RL) were operated in parallel in the equivalent circuit [26]. The effective double-layer capacity (Cdl) values obtained from the impedance data were calculated using the formula described in Equation (5) and presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

EIS parameters for pure Fe and pure Al after immersion in 1M HCl solution with (without) corrosion inhibitor (2500 ppm MHBTZ) at 25 °C.

Rp indicates the polarization resistance, Y0 measures the CPE coefficients (reciprocal impedance values also known as admittances), and n describes surface heterogeneity.

The inhibition efficiency (IE) (Equation (6)) was determined through polarization resistance (Rp) measurements because this parameter serves as a standard method to evaluate electrochemical corrosion behavior. The Rp(blank) value represents the resistance of the uninhibited solution, while Rp(inh) shows the resistance values obtained with the inhibitor present. The difference between these two parameters directly indicates the extent to which the inhibitor protects the surface while minimizing the corrosion activity.

Table 1 lists the EIS parameters for iron and aluminum metals with and without the investigated inhibitor. The results showed that the double-layer capacitance (Cdl) decreased when the MHBTZ concentration increased. However, Rp increased with increasing MHBTZ concentration and reached 302.78 Ωcm2 at the highest concentration. The highest Rp value corresponded to the maximum inhibition efficiency of MHBTZ, which reached 98.94% at 2500 ppm. The high Rp resistance was caused by the film resistance that appeared in the Fe equivalent circuit as the barrier film resistance at the electrode surface.

The electrochemical parameters from the aluminum results showed that the polarization resistance increases as the MHBTZ concentration increases, reaching its highest value of 201.67 Ω.cm2 at 2500 ppm. Enhanced resistance indicates shorter distances between the adsorbed inhibitor-metal surface, thus verifying the order of the inhibition performance while showing a decreased double-layer capacitance. The optimum concentration resulted in 99.16% inhibition. Moreover, the charge transfer resistance (Rct) and induction resistance (RL) increased when the MHBTZ concentration increased, whereas the double layer capacitance decreased until it reached 27.95 μF·cm−2 at 2500 ppm. The equivalent circuit model for the aluminum working electrodes includes an inductor, which indicates the presence of induction resistance. The equivalent circuit model for Fe metal does not include this parameter because it lacks an inductor element.

MHBTZ exhibited excellent inhibitory properties under the examined conditions by forming an effective protective barrier. The protective barrier on the Fe and Al metal surfaces resulted from the adsorption of MHBTZ molecules. This adsorption behavior arises from the benzotriazole and phenyl rings in the molecular structure. The experimental results demonstrate that MHBTZ exhibits strong reactivity, which is consistent with theoretical predictions.

EIS was employed to evaluate the performance of the MHBTZ molecules against pure Fe and Al metals in 1 M HCl at 298 K, both with and without MHBTZ. Figure 3 shows Nyquist plots and the equivalent circuit simulations for each metal.

3.3. LPR Measurement

The efficiency of MHBTZ as a corrosion inhibitor in 1 M HCl was assessed using the linear polarization resistance (LPR) method. This electrochemical method provides a reliable, non-destructive, and real-time evaluation of corrosion rates and is widely employed to quantify the protective performance of inhibitors. In this approach, a small potential perturbation of ±10 mV relative to the OCP was applied, establishing a direct relationship between the corrosion current density icorr and the measured potential response. The polarization resistance Rp was determined using Equation (7) [57], where βa and βc are the anodic and cathodic Tafel slopes, respectively.

The inhibition efficiency (IE%) was subsequently calculated using Equation (8):

Rp (blank) denotes the polarization resistance of the uninhibited solution, whereas Rp (inh) corresponds to the values obtained in the presence of the inhibitor. These parameters provide quantitative insights into the ability of the tested compounds to suppress both anodic and cathodic processes during the corrosion of pure iron and pure aluminum (±standard deviation), as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

LPR results for pure Fe and pure Al after immersion in 1M HCl solution with (without) corrosion inhibitor (2500 ppm MHBTZ) at 25 °C.

3.4. PDP Measurement

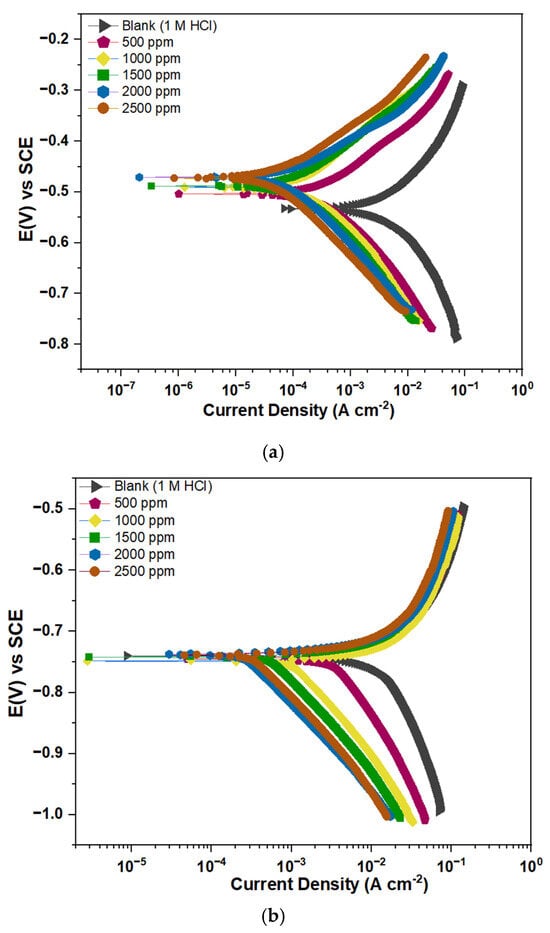

To understand the corrosion kinetics at the Fe/Al metal solution interfaces, PDP measurements were performed. The recorded and displayed polarization curves for Fe and Al immersed in 1 M HCl with and without MHBTZ are shown in Figure 4. The electrochemical parameters (icorr, Ecorr, ßc, and ßa) were obtained by extrapolating both the anodic and cathodic regions using the Gamry Echem Analyst program and are presented in Table 3. The addition of the MHBTZ inhibitor caused a shift in the obtained plots toward lower corrosion current densities compared with the uninhibited solution, based on the polarization curves. The reduction in icorr values became more pronounced with increasing inhibitor concentrations. The inhibitor demonstrated dual functionality, blocking both the anodic and cathodic reactions. MHBTZ was absorbed onto Fe and Al metal surfaces by slowing down hydrogen evolution reactions and preventing chlorides from contacting the electrode surface [24,58].

Figure 4.

Polarization curves of (a) Pure Fe, (b) Pure Al electrodes in 1 M HCl solution without and with different concentrations of MHBTZ at 25 °C.

Table 3.

PDP results for pure Fe and pure Al after immersion in 1M HCl solution with (without) corrosion inhibitor (2500 ppm MHBTZ) at 25 °C.

The Polarization curves of (Figure 4a) Pure Fe and (Figure 4b) Pure Al electrodes in 1 M HCl solution without and with different concentrations of MHBTZ at 25 °C are presented in Figure 4. The result shows that MHBTZ slows down hydrogen evolution more effectively than metal dissolution for both pure Fe and Al metals, as evident in their distinct parallel cathodic curves [47]. The icorr values for Fe metal decreased as the MHBTZ concentration increased until it reached 0.103 mA·cm−2, resulting in 99.20% inhibition at 2500 ppm. On the other hand, the Al metal achieved an inhibition level of 99.27% at the same concentration, with a corrosion current density of 0.703 mA·cm−2.

The cathodic Tafel slope (βc) did not exhibit significant variations with increasing inhibitor concentration, indicating that hydrogen evolution followed a pure activation process [59,60]. The MHBTZ inhibitor protects both the anodic and cathodic processes at the Fe and Al metal surfaces through its mixed inhibition properties. The polarization curve results shown in Figure 4 confirm this finding [61,62].

The high inhibition level, which produces minimal corrosion current densities, can be attributed to the enhanced surface coverage by adsorbed molecules on the electrode surface. The formation of a barrier film is improved, which protects the material from aggressive environments [63]. The PDP analysis results followed the order of inhibition performance determined by LPR measurement.

The inhibition efficiencies were calculated from the icorr values using Equation (9):

The corrosion current densities of the sample in 1 M HCl solution with and without inhibitors are denoted by icorr (blank) and icorr (inh), respectively.

3.5. Computational Details

3.5.1. Chemical Reactivity Prediction of MHBTZ

Quantum chemical calculations have become powerful tools for predicting molecular reactivity before experimental validation, thereby minimizing unnecessary effort, costs, and time. In this study, the DMol3 module executes all the quantum chemical calculations using DFT methods. Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations were performed at the PBE/GGA/DNP level to gain insights into the structural and electronic properties of MHBTZ and evaluate its potential as a corrosion inhibitor. Because the central aim of this study was to assess the applicability of MHBTZ in acidic environments, particular attention was given to the species expected to dominate under such conditions. The possible protonated forms were identified using the Marvin Sketch software to approximate the experimental environment. As illustrated in Figure 1, the second protonated form (Form 2) was predicted to be the most stable species at highly acidic pH, exhibiting the highest distribution percentage near pH 0.

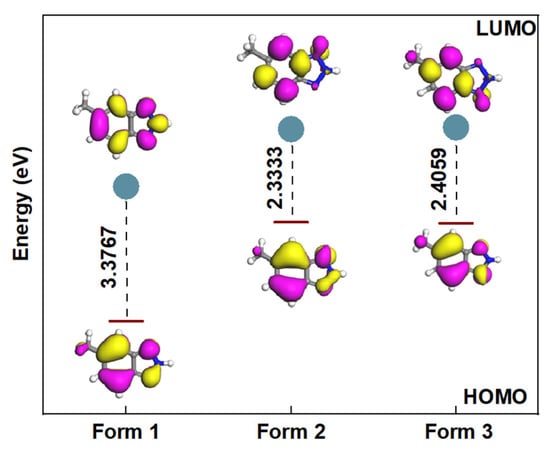

Aqueous phase optimization of the MHBTZ molecule resulted in a complete geometric configuration determination, as shown in Figure 5. The chemical activity of the molecule was determined by analyzing the two frontier molecular orbitals, LUMO and HOMO. The ELUMO shows the ability of a molecule to accept electrons, whereas EHOMO shows the potential of a molecule to donate electrons. The energy gap (ΔE) between the molecular orbitals is equal to ELUMO-EHOMO. Figure 5 shows that Form 2 exhibits the lowest energy gap. This implies that Form 2 is the most reactive and has the highest potency for interacting with the Fe and Al surfaces compared to Forms 1 and 3.

Figure 5.

HOMO, LUMO and energy gaps (in eV) of MHBTZ forms using in their abundant forms at pH = 0 in aqueous solution.

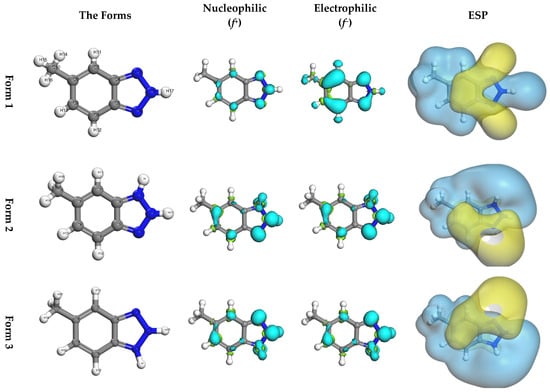

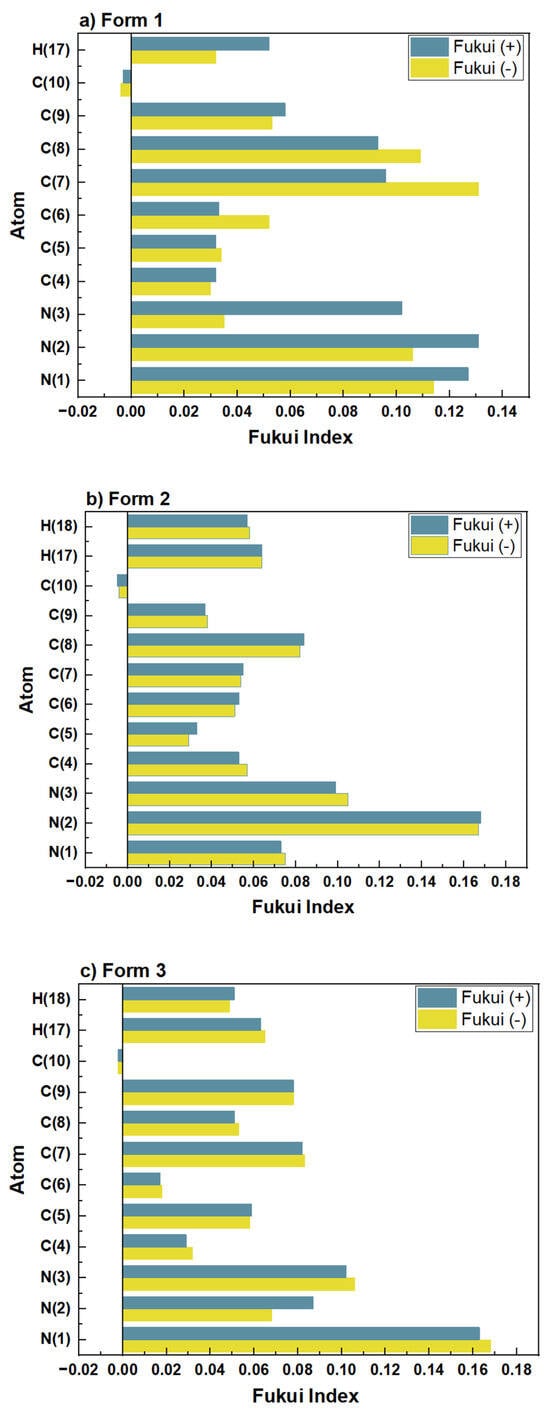

Furthermore, the Fukui function provides atomic-level insights into the potential electron transfer pathways between MHBTZ molecules and the surfaces of iron and aluminum. This approach highlights the specific reactive centers responsible for adsorption, thereby strengthening the mechanistic understanding of the inhibition process. The nucleophilic and electrophilic properties of MHBTZ are shown in Figure 6 and Figure 7, respectively. The Fukui indices (ƒ+ and ƒ−) were calculated using Mulliken population analysis to perform a detailed assessment of the local reactivity. The Fukui indices show which atoms in the MHBTZ molecules accept or donate electrons during nucleophilic, electrophilic, or radical attacks. For a molecular structure, the nucleophilic Fukui function (ƒ−) indicates locations prone to providing electrons, whereas the electrophilic Fukui function (ƒ+) indicates regions that are inclined to accept electrons. For instance, higher ƒ+ values were concentrated at the N1, N2, and N3 atoms in Form 1–3. Similarly elevated ƒ− values were prominent at the C7, C8, N1 and N2 atoms in all forms. Notably, these findings from the Fukui indices shed light on the reaction sites between donors and recipients for all forms of MHBTZ, thus identifying the metal surface adsorption sites at the atomic level.

Figure 6.

Optimized geometries, nucleophilic (f+), electrophilic (f−) and molecular electrostatic potential (ESP) of the three MHBTZ forms.

Figure 7.

Fukui functions for nucleophilic and electrophilic sites of the three MHBTZ forms.

3.5.2. Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations

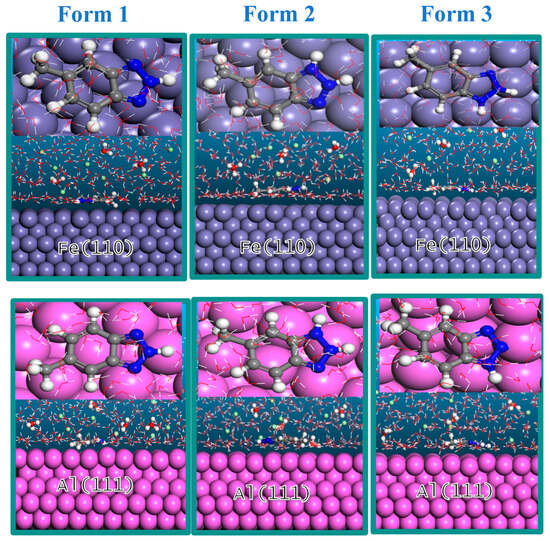

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were used to obtain the interaction energies between the Fe and Al metal surfaces and the three different forms of MHBTZ. Before conducting the MD simulation, the system was equilibrated to achieve a stable temperature and energy. The most stable adsorption positions of MHBTZ forms on the Fe and Al metal specimens are shown in Figure 8. The adsorption sites that drive the adsorption process mainly consist of N atoms located on the triazole and charge distribution on the phenyl ring structure found in the inhibitor molecule. The MHBTZ molecule aligns parallel to the metal surface, resulting in complete surface coverage and solidification of the strong interaction bond between the adsorbate and substrate systems. Table 4 presents the interaction energies of the three forms of the MHBTZ inhibitor on Fe (110) and Al (111) surfaces. The energy values presented in Table 4 were calculated according to Equation (2), which defines the interaction energy of the inhibitor-metal system. The interaction energy of form 2 of MHBTZ was the most negative for the Fe (110) surface (−103.53 kcal/mol) and Al (111) surface (−65.61 kcal/mol). The high negative energy interaction indicates a stronger interaction between Form 2 of MHBTZ and the two metal surfaces. This indicates that among the different forms of MHBTZ, Form 2 is the most important in acidic solutions.

Figure 8.

Most stable adsorption configurations of the three forms of the MHBTZ inhibitor on Fe (110) and Al (111) surfaces. Gray ( ) =Fe, Purple (

) =Fe, Purple ( ) = Al, Dark gray (

) = Al, Dark gray ( ) = C, Green (

) = C, Green ( ) = Cl, Red (

) = Cl, Red ( ) = O, Blue (

) = O, Blue ( ) = N, White (

) = N, White ( ) = H.

) = H.

) =Fe, Purple (

) =Fe, Purple ( ) = Al, Dark gray (

) = Al, Dark gray ( ) = C, Green (

) = C, Green ( ) = Cl, Red (

) = Cl, Red ( ) = O, Blue (

) = O, Blue ( ) = N, White (

) = N, White ( ) = H.

) = H.

Table 4.

Interaction energy of the three forms of the MHBTZ inhibitor on Fe (110) and Al (111) surfaces (Kcal/mol).

3.6. Optical Profilometry Analysis

The 3D optical profilometer is a vital instrument for studying pitting corrosion and metal surface roughness under both corrosion inhibitor-free and inhibitor-present conditions [64,65]. The optical profilometry (2D and 3D) images in Figure 9 demonstrate the surface conditions of pure Fe and Al metals after 4 h in 1 M HCl solution with and without 2500 ppm MHBTZ corrosion inhibitor. The addition of corrosion resulted in substantial surface quality enhancement of iron and aluminum materials (±standard deviation), according to the 3D profilometry results shown in Figure 9 and Table 5, respectively. The iron surface experienced a substantial reduction in the Arithmetic Mean Height (Sa) value from 0.26 µm to 0.16 µm because of the ability of the inhibitor to fight general corrosion. The inhibitor had an enhanced effect on aluminum surfaces, as the Sa value decreased from 0.80 µm to 0.18 µm, indicating a substantial improvement in surface smoothness. Sq is represented by the Root Mean Square Height, which shows the root mean square value of surface height measurements relative to the mean plane, making it suitable for surface roughness evaluation. The surface appeared more even when the Sq values were low. The value of the iron and aluminum surface decreased from 0.34 in the blank solution to 0.20 in the inhibited solution for Fe, and from 1.16 to 0.23 for Al, which measures the effectiveness of corrosion inhibitors in surface protection. Moreover, the Ssk parameter indicates how the surface height data points are distributed across the measurement area. The presence of deep pits or valleys on the surfaces. The application of inhibitors resulted in changes in the Ssk value, indicating both reduced pit depth and frequency, as well as a surface transition from pitting to uniform corrosion. The Ssk value of iron and aluminum decreased from −0.87 in the blank solution to −0.17 in the inhibited solution for Fe, and also from −2.14 to −0.38 for Al metal. The kurtosis (Sku) value of the aluminum surface decreased dramatically from 10.82 to 3.95, indicating that the inhibitor transformed severe localized pitting corrosion into a more uniform and less aggressive corrosion pattern. The formation of the protective layer was confirmed by a substantial decrease in the Maximum Peak Height (Sp), Maximum Valley Depth (Sv), and maximum peak-to-valley height (St). values for both metals, demonstrating the ability of the inhibitor to minimize the surface deterioration. The inhibitor was exceptionally effective in blocking localized corrosion on aluminum surfaces, which is essential for maintaining material durability in harsh environments [66].

Figure 9.

Three-dimensional morphology scanning results for the front side of the pure metals after 4 h immersion in 1 M HCl solution (with and without 2500 ppm of MHBTZ as corrosion inhibitor).

Table 5.

Summarizes the 3D profilometry parameters of pure metals after immersion in electrolytes with (without) corrosion inhibitor (2500 ppm MHBTZ) after 4 h.

4. Conclusions

This study was motivated by the need to encourage the development of multi-purpose corrosion inhibitor systems that offer sufficiently high efficiency against acid cleaning-induced corrosion of multi-metallic industrial equipment. This minimizes expenses and encourages convenience for the industry. In this study, 5-Methyl-1H-benzotriazole (MHBTZ) was investigated for its ability to mitigate acid corrosion of Fe and Al metals. In this study, experimental electrochemical techniques and theoretical approaches were employed to assess the inhibition performance of MHBTZ on iron and aluminum in 1 M HCl. This combined strategy offers valuable insights into protective mechanisms by linking molecular reactivity with electrochemical behavior. The following conclusions were obtained from this study:

- MHBTZ acts as a good corrosion inhibitor for pure Fe and Al in 1 M HCl, confirming the high reactivity of this derivative. It achieved inhibition percentages of 97.82% and 96.09% for Fe and Al pure metals, respectively.

- MHBTZ was adsorbed on Fe and Al metal surfaces using mostly N atoms in its triazole ring. These sites are also the centers of protonation through which MHBTZ engages in the respective adsorption and inhibition mechanisms for the two pure metals.

- For Fe corrosion in HCl, the polarization curves revealed that MHBTZ acted as a mixed-type inhibitor, inhibiting both the metal dissolution/hydrogen evolution reaction. However, for Al corrosion, the polarization curves show mainly cathodic inhibition, indicating a hydrogen evolution mechanism.

- The 3D surface optical profilometer analysis confirmed the adsorption of the MHBTZ inhibitor on the pure Fe and Al metal surfaces and the reduction in localized corrosion.

- A DFT study based on the frontier molecular orbital theory revealed that the MHBTZ molecule can exhibit good reactivity because it has various active sites that act as nucleophiles and/or electrophiles.

- MD simulations revealed that the MHBTZ molecule exhibited a high negative interaction energy on the Fe and Al metal surfaces, indicating a strong interaction and, by extension, the high inhibition efficiencies obtained experimentally.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to Imam Abdulrahman bin Faisal University, Dammam, Saudi Arabia, for providing resources. The author acknowledges KFUPM for its support in using BIOVIA Material Studio Software.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ahmad, Z. Principles of Corrosion Engineering and Corrosion Control; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Vera, J.R.; Daniels, D.; Achour, M.H. Under deposit corrosion (UDC) in the oil and gas industry: A review of mechanisms, testing and mitigation. In Proceedings of the Nace Corrosion, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 11–15 March 2012; NACE: Houston, TX, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, R.I.; Odah, M.K.; Sami, H.A. A review on recent techniques for boiler tubes corrosion protection and fouling mitigation using PLC. Anbar J. Eng. Sci. 2020, 11, 184–191. [Google Scholar]

- Obot, I.; Meroufel, A.; Onyeachu, I.B.; Alenazi, A.; Sorour, A.A. Corrosion inhibitors for acid cleaning of desalination heat exchangers: Progress, challenges and future perspectives. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 296, 111760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgkiess, T.; Al-Omari, K.; Bontems, N.; Lesiak, B. Acid cleaning of thermal desalination plant: Do we need to use corrosion inhibitors? Desalination 2005, 183, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, G.A. NACE international’s IMPACT study breaks new ground in corrosion management research and practice. Bridge 2016, 55, 28–32. [Google Scholar]

- Abd El Rehim, S.S.; Hassan, H.H.; Amin, M.A. Corrosion inhibition study of pure Al and some of its alloys in 1.0 M HCl solution by impedance technique. Corros. Sci. 2004, 46, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, M.; Kumar, S.; Bahadur, I.; Verma, C.; Ebenso, E.E. Organic corrosion inhibitors for industrial cleaning of ferrous and non-ferrous metals in acidic solutions: A review. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 256, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larabi, L.; Harek, Y.; Benali, O.; Ghalem, S. Hydrazide derivatives as corrosion inhibitors for mild steel in 1 M HCl. Prog. Org. Coat. 2005, 54, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tidke, S.D.; Kulkarni, S.S.; Marathe, A.C. Comprehensive review of green corrosion inhibitors for safe and sustainable protection of mild steel in acidic environments. Discov. Electrochem. 2025, 2, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, J.; Srivastava, V.; Verma, C.; Quraishi, M. Experimental and quantum chemical analysis of 2-amino-3-((4-((S)-2-amino-2-carboxyethyl)-1H-imidazol-2-yl) thio) propionic acid as new and green corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in 1 M hydrochloric acid solution. J. Mol. Liq. 2017, 225, 848–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetouani, A.; Hammouti, B.; Aouniti, A.; Benchat, N.; Benhadda, T. New synthesised pyridazine derivatives as effective inhibitors for the corrosion of pure iron in HCl medium. Prog. Org. Coat. 2002, 45, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Amiery, A.A.; Kadhum, A.A.H.; Mohamad, A.B.; Junaedi, S. A novel hydrazinecarbothioamide as a potential corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in HCl. Materials 2013, 6, 1420–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q.; Shi, H.-W.; Ding, N.-N.; Chen, B.-Q.; He, X.-P.; Liu, G.; Tang, Y.; Long, Y.-T.; Chen, G.-R. Novel triazolyl bis-amino acid derivatives readily synthesized via click chemistry as potential corrosion inhibitors for mild steel in HCl. Corros. Sci. 2012, 57, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puzikova, D.; Khussurova, G.; Leontyeva, X.; Kholkin, O.; Kenzin, N.; Zhurinov, M.; Peshaya, S. Review of organic corrosion inhibitors: Application with respect to the main functional group. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2025, 29, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedir, A.G.; Abd El-raouf, M.; Abdel-Mawgoud, S.; Negm, N.A.; El Basiony, N. Corrosion inhibition of carbon steel in hydrochloric acid solution using ethoxylated nonionic surfactants based on schiff base: Electrochemical and computational investigations. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 4300–4312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mrani, S.A.; Salim, R.; Arrousse, N.; El Abiad, C.; Radi, S.; Saffaj, T.; Taleb, M. Computational, SEM/EDX and experimental insights on the adsorption process of novel Schiff base molecules on mild steel/1 M HCl interface. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 368, 120648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindert, A.; Johnston, W.G. New low toxicity corrosion inhibitors for industrial cleaning operations. In Proceedings of the NACE CORROSION, San Antonio, TX, USA, 25–30 April 1999; NACE: Houston, TX, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Prasanna, B.; Praveen, B.; Hebbar, N.; Venkatesha, T. Anticorrosion potential of hydralazine for corrosion of mild steel in 1m hydrochloric acid solution. J. Fundam. Appl. Sci. 2015, 7, 222–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, E.; Rodríguez, J.A.; Cruz-Borbolla, J.; Alvarado-Rodríguez, J.G.; Thangarasu, P. Development of a predictive model for corrosion inhibition of carbon steel by imidazole and benzimidazole derivatives. Corros. Sci. 2016, 108, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoud, D.; Douadi, T.; Hamani, H.; Chafaa, S.; Al-Noaimi, M. Corrosion inhibition of mild steel by two new S-heterocyclic compounds in 1 M HCl: Experimental and computational study. Corros. Sci. 2015, 94, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomma, G.K.; Wahdan, M.H. Schiff bases as corrosion inhibitors for aluminium in hydrochloric acid solution. Mater. Chem. Phys. 1995, 39, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, M.; El Rehim, S.A. The effect of some ethoxylated fatty acids on corrosion of aluminium in hydrochloric acid solutions. Mater. Chem. Phys. 1998, 53, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitra, A.; Barua, S. Dicyandiamide—An inhibitor for acid corrosion of pure aluminium. Corros. Sci. 1974, 14, 587–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, M.; Taha, F.; Gouda, M.; Singab, G. The effect of some hydrazine derivatives on the corrosion of Al in HCl solution. Corros. Sci. 1976, 16, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Deng, S.; Xie, X. Experimental and theoretical study on corrosion inhibition of oxime compounds for aluminium in HCl solution. Corros. Sci. 2014, 81, 162–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, M.; Thakar, B.; Chhaya, P.; Gandhi, M. Inhibition of corrosion of aluminium-51S in hydrochloric acid solutions. Corros. Sci. 1976, 16, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Etre, A. Inhibition of acid corrosion of aluminum using vanillin. Corros. Sci. 2001, 43, 1031–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutouil, A.; Laamari, M.R.; Elazhary, I.; Bahsis, L.; Anane, H.; Stiriba, S.-E. Towards a deeper understanding of the inhibition mechanism of a new 1,2,3-triazole derivative for mild steel corrosion in the hydrochloric acid solution using coupled experimental and theoretical methods. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2020, 241, 122420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naciri, M.; El Aoufir, Y.; Lgaz, H.; Lazrak, F.; Ghanimi, A.; Guenbour, A.; El Moudane, M.; Taoufik, J.; Chung, I.-M. Exploring the potential of a new 1,2,4-triazole derivative for corrosion protection of carbon steel in HCl: A computational and experimental evaluation. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2020, 597, 124604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahlé, A.; Salim, R.; El Hajjaji, F.; Aouad, M.; Messali, M.; Ech-Chihbi, E.; Hammouti, B.; Taleb, M. Novel triazole derivatives as ecological corrosion inhibitors for mild steel in 1.0 M HCl: Experimental & theoretical approach. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 4147–4162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, M.K.; Mustafa, M.R.; Elnga, M.M.A. Computational simulation of the molecular structure of some triazoles as inhibitors for the corrosion of metal surface. J. Mol. Struct. Theochem 2010, 959, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Olvera, R.; Espinoza-Vázquez, A.; Negrón-Silva, G.E.; Palomar-Pardavé, M.E.; Romero-Romo, M.A.; Santillan, R. Multicomponent click synthesis of new 1, 2, 3-triazole derivatives of pyrimidine nucleobases: Promising acidic corrosion inhibitors for steel. Molecules 2013, 18, 15064–15079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L.; Zhu, S.; Zhang, S.; He, Q.; Li, W. Theoretical studies of three triazole derivatives as corrosion inhibitors for mild steel in acidic medium. Corros. Sci. 2014, 87, 366–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raviprabha, K.; Bhat, R.S. Electrochemical and quantum chemical studies of 5-[(4-Chlorophenoxy) methyl]-4H-1,2,4-Triazole-3-Thiol on the corrosion inhibition of 6061 Al alloy in hydrochloric acid. J. Fail. Anal. Prev. 2020, 20, 1598–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scendo, M.; Staszewska-Samson, K. Assessment of the inhibition efficiency of 3-amino-5-methylthio-1H-1,2,4-triazole against the corrosion of mild steel in acid chloride solution. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2017, 12, 5668–5691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, M.; Ashmawy, A.M.; Reheim, M.A.A.; Bedair, M.A.; Abuelela, A.M. Molecular structure aspects and molecular reactivity of some triazole derivatives for corrosion inhibition of aluminum in 1 M HCl solution. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1236, 130292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, R.; Ech-chihbi, E.; Fernine, Y.; Koudad, M.; Guo, L.; Berdimurodov, E.; Azam, M.; Rais, Z.; Taleb, M. Inhibition behavior of new ecological corrosion inhibitors for mild steel, copper and aluminum in acidic environment: Theoretical and experimental investigation. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 393, 123579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashgari, M.; Malek, A.M. Fundamental studies of aluminum corrosion in acidic and basic environments: Theoretical predictions and experimental observations. Electrochim. Acta 2010, 55, 5253–5257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouda, A.; Moussa, M.; Taha, F.; Elneanaa, A. The role of some thiosemicarbazide derivatives in the corrosion inhibition of aluminium in hydrochloric acid. Corros. Sci. 1986, 26, 719–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.M.; Elawady, Y.; Ahmed, A.I.; Baghlaf, A. Studies on the inhibition of aluminium dissolution by some hydrazine derivatives. Corros. Sci. 1979, 19, 951–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsissou, R.; Benhiba, F.; Dagdag, O.; El Bouchti, M.; Nouneh, K.; Assouag, M.; Briche, S.; Zarrouk, A.; Elharfi, A. Development and potential performance of prepolymer in corrosion inhibition for carbon steel in 1.0 M HCl: Outlooks from experimental and computational investigations. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 574, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, C.; Obot, I.; Bahadur, I.; Sherif, E.-S.M.; Ebenso, E.E. Choline based ionic liquids as sustainable corrosion inhibitors on mild steel surface in acidic medium: Gravimetric, electrochemical, surface morphology, DFT and Monte Carlo simulation studies. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 457, 134–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowsari, E.; Arman, S.; Shahini, M.; Zandi, H.; Ehsani, A.; Naderi, R.; PourghasemiHanza, A.; Mehdipour, M. In situ synthesis, electrochemical and quantum chemical analysis of an amino acid-derived ionic liquid inhibitor for corrosion protection of mild steel in 1M HCl solution. Corros. Sci. 2016, 112, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, G.; Berent, K.; Proniewicz, E.; Banas, J. Guar Gum as an eco-friendly corrosion inhibitor for pure aluminium in 1-M HCl solution. Materials 2019, 12, 2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamghafri, S.; Daoudi, W.; Dagdag, O.; Naguib, I.A.; Nik, W.M.N.W.; Berisha, A.; Kim, H.; El Aatiaoui, A.; Zarrouk, A.; Lamhamdi, A. Promising corrosion resistance of mild steel, copper, and aluminum in hydrochloric acid solution using an environmentally friendly corrosion inhibitor. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2025, 146, 332–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odusote, J.; Asafa, T.; Oseni, J.; Adeleke, A.; Adediran, A.; Yahya, R.; Abdul, J.; Adedayo, S. Inhibition efficiency of gold nanoparticles on corrosion of mild steel, stainless steel and aluminium in 1M HCl solution. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 38, 578–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdew, J.P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delley, B. Ground-state enthalpies: Evaluation of electronic structure approaches with emphasis on the density functional method. J. Phys. Chem. A 2006, 110, 13632–13639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klamt, A.; Schüürmann, G. COSMO: A new approach to dielectric screening in solvents with explicit expressions for the screening energy and its gradient. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2 1993, 799–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, C.; Lgaz, H.; Verma, D.; Ebenso, E.E.; Bahadur, I.; Quraishi, M. Molecular dynamics and Monte Carlo simulations as powerful tools for study of interfacial adsorption behavior of corrosion inhibitors in aqueous phase: A review. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 260, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Tang, Y.; Qi, S.; Dong, D.; Cang, H.; Lu, G. The inhibition performance of long-chain alkyl-substituted benzimidazole derivatives for corrosion of mild steel in HCl. Corros. Sci. 2016, 102, 517–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrousse, N.; Fernine, Y.; Al-Zaqri, N.; Boshaala, A.; Ech-Chihbi, E.; Salim, R.; El Hajjaji, F.; Alami, A.; Touhami, M.E.; Taleb, M. Thiophene derivatives as corrosion inhibitors for 2024-T3 aluminum alloy in hydrochloric acid medium. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 10321–10335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouakki, M.; Galai, M.; Benzekri, Z.; Aribou, Z.; Ech-chihbi, E.; Guo, L.; Dahmani, K.; Nouneh, K.; Briche, S.; Boukhris, S. A detailed investigation on the corrosion inhibition effect of by newly synthesized pyran derivative on mild steel in 1.0 M HCl: Experimental, surface morphological (SEM-EDS, DRX& AFM) and computational analysis (DFT & MD simulation). J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 344, 117777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menkuer, M.; Ozkazanc, H. Anticorrosive polypyrrole/zirconium-oxide composite film prepared in oxalic acid and dodecylbenzene sulfonic acid mix electrolyte. Prog. Org. Coat. 2020, 147, 105815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Scenini, F.; Stevens, N.; Curioni, M. Relationship between the inductive response observed during electrochemical impedance measurements on aluminium and local corrosion processes. Corros. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2019, 54, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umoren, S.A. Polypropylene glycol: A novel corrosion inhibitor for× 60 pipeline steel in 15% HCl solution. J. Mol. Liq. 2016, 219, 946–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouakki, M.; Galai, M.; Benzekri, Z.; Verma, C.; Ech-Chihbi, E.; Kaya, S.; Boukhris, S.; Ebenso, E.E.; Touhami, M.E.; Cherkaoui, M. Insights into corrosion inhibition mechanism of mild steel in 1 M HCl solution by quinoxaline derivatives: Electrochemical, SEM/EDAX, UV-visible, FT-IR and theoretical approaches. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2021, 611, 125810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazkour, A.; El Hajjaji, S.; Labjar, N.; Lotfi, E.M.; El Mahi, M. Corrosion inhibition effect of 5-azidomethyl-8-hydroxyquinoline on AISI 321 stainless steel in phosphoric acid solution. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2021, 16, 210336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.; Guo, J.; Zhao, Q.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Y. Enhanced corrosion inhibition of carbon steel by pyridyl gemini surfactants with different alkyl chains. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2020, 240, 122156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iroha, N.B.; Maduelosi, N.J. Corrosion inhibitive action and adsorption behaviour of justicia secunda leaves extract as an eco-friendly inhibitor for aluminium in acidic media. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem 2021, 11, 13019–13030. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, M.; Tiwari, P.; Srivastava, S.K.; Prakash, R.; Ji, G. Electrochemical investigation of Irbesartan drug molecules as an inhibitor of mild steel corrosion in 1 M HCl and 0.5 M H2SO4 solutions. J. Mol. Liq. 2017, 236, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Jing, J.; Feng, L.; Zhu, H.; Hu, Z.; Ma, X. Study on corrosion inhibition behavior and adsorption mechanism of novel synthetic surfactants for carbon steel in 1 M HCl solution. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2021, 23, 100500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Jiang, L.; Qian, L. Achievement of sub-nanometer surface roughness of bearing steel via chemical mechanical polishing with the synergistic effect of heterocyclic compounds containing N and S. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2022, 52, 357–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finšgar, M. 2-Mercaptobenzimidazole as a copper corrosion inhibitor: Part I. Long-term immersion, 3D-profilometry, and electrochemistry. Corros. Sci. 2013, 72, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuha Wazzan, I.B.O. Unraveling the structure-property relationship of pyrimidine-derivatives as CO2 corrosion inhibitors: Experimental and periodic DFT investigations. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 112206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.