Strain Range Dependent Cyclic Hardening of 08Ch18N10T Stainless Steel—Experiments and Simulations

Abstract

1. Introduction

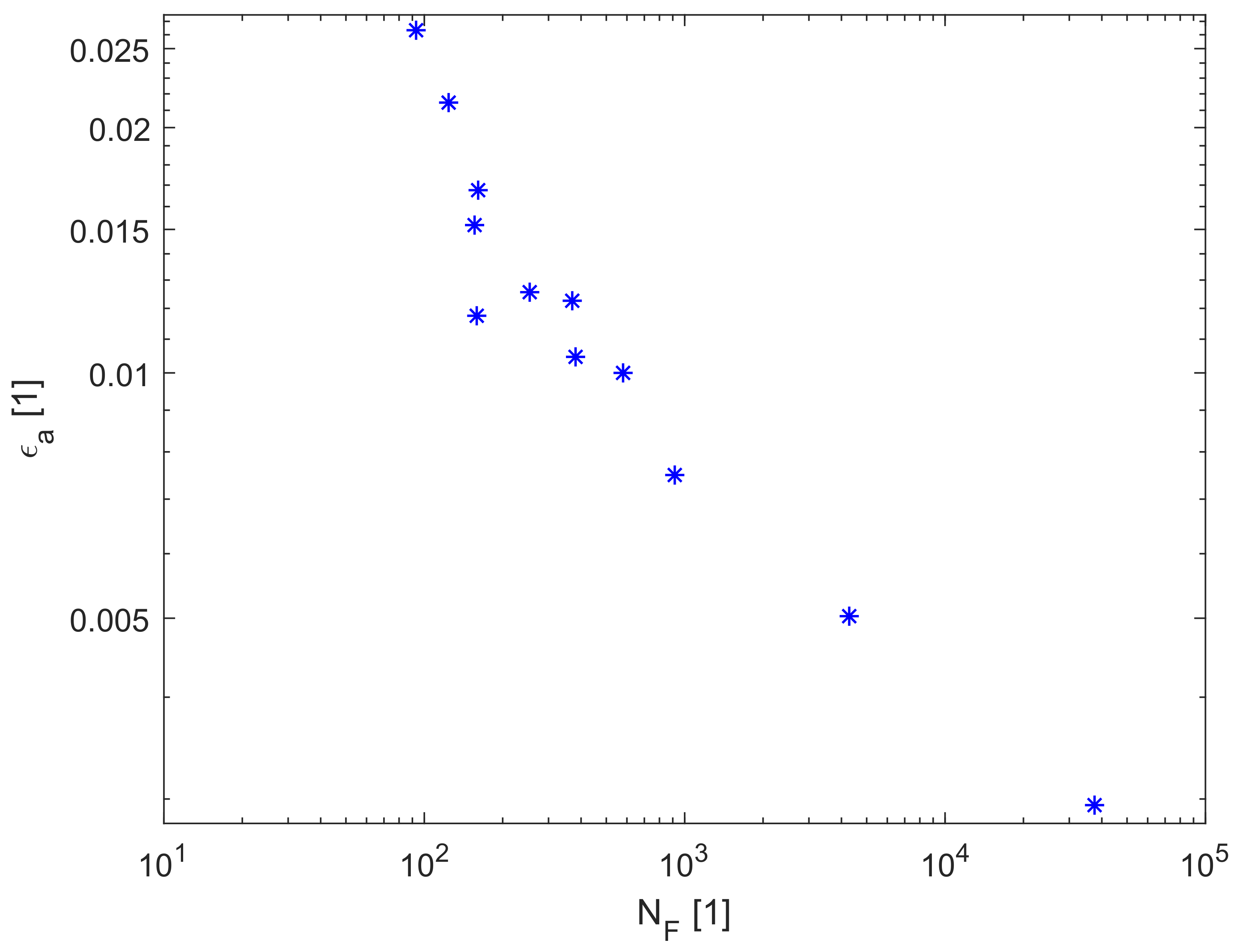

2. Experiments

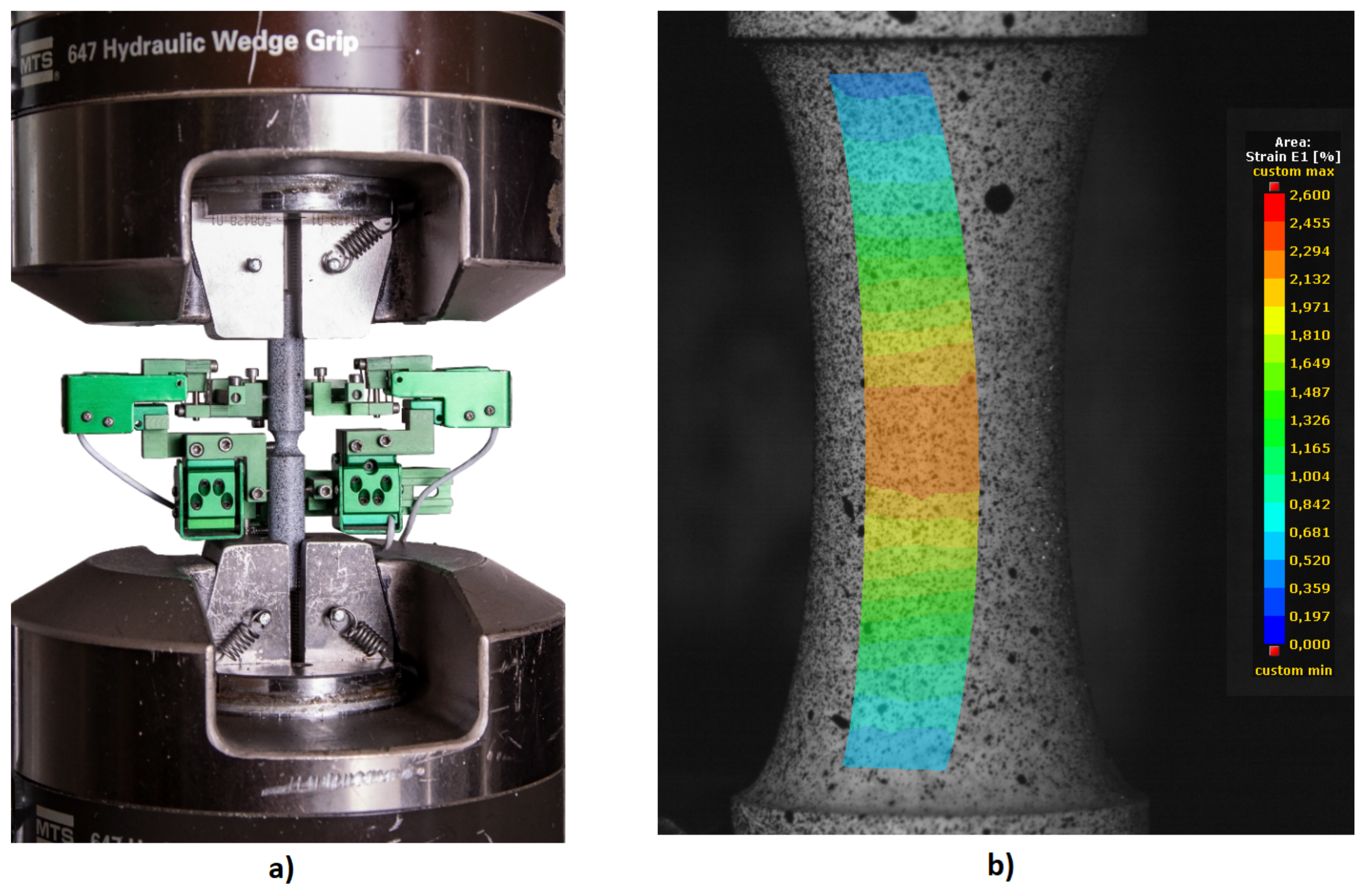

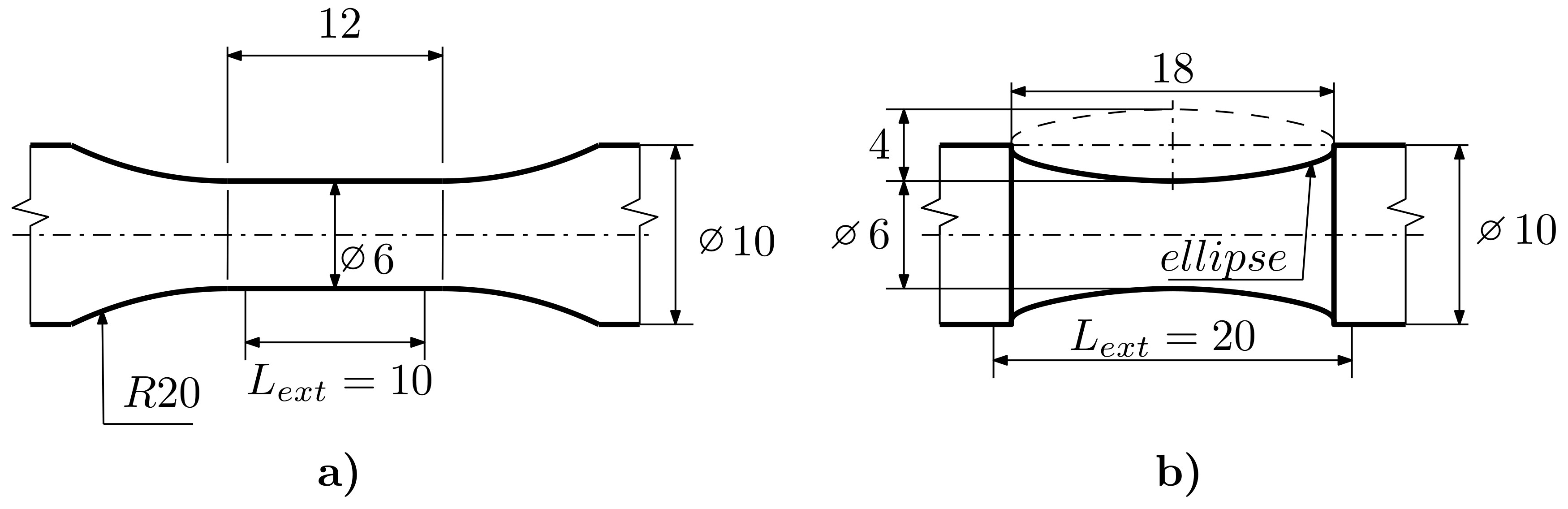

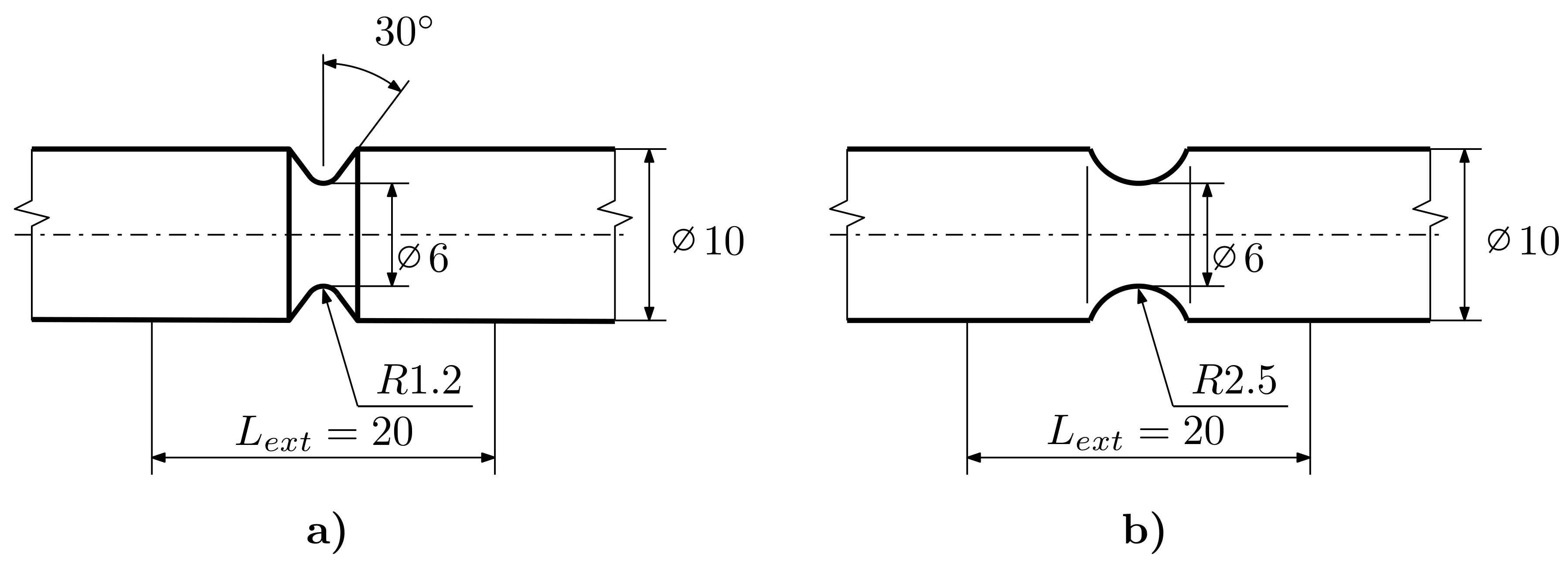

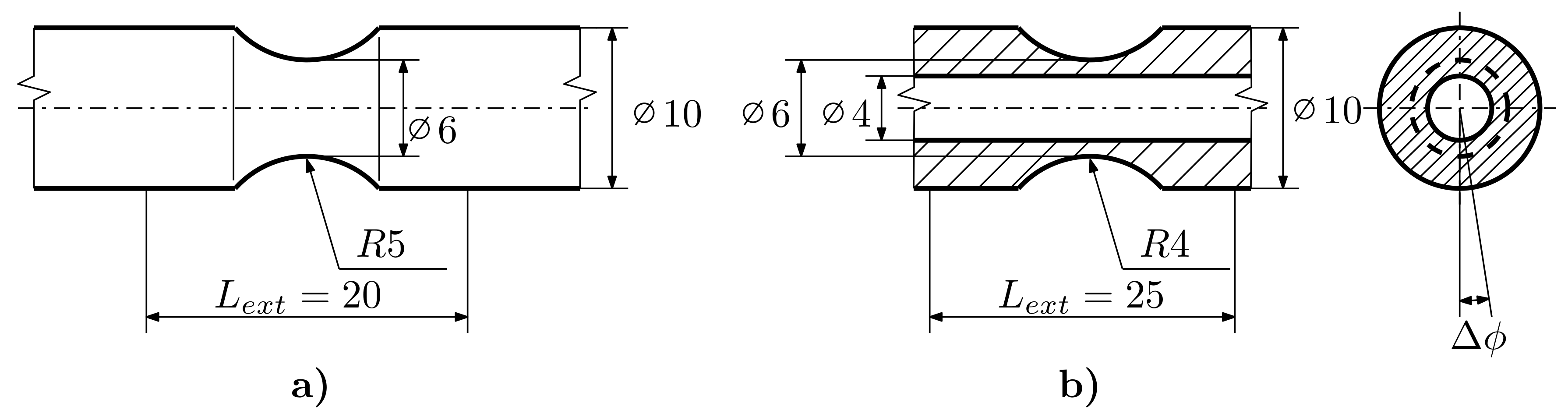

2.1. Experimental Setup

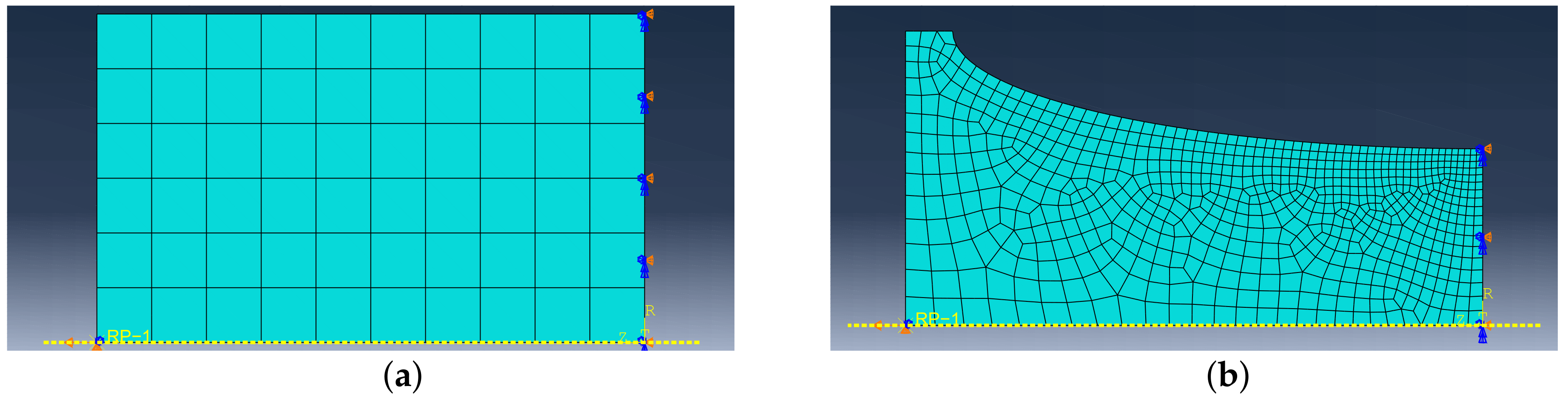

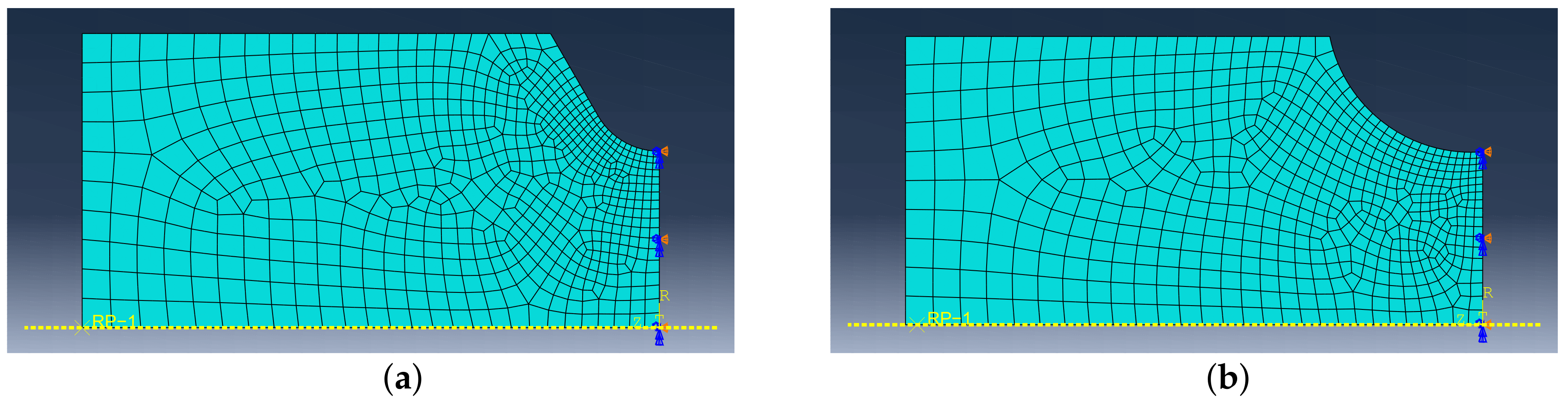

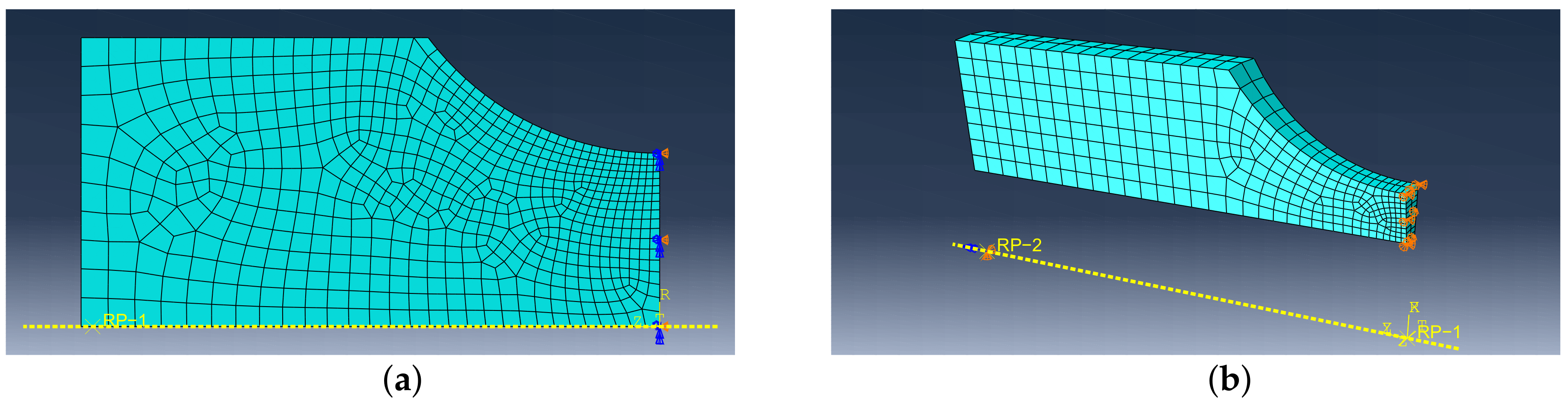

2.2. Experimental Program

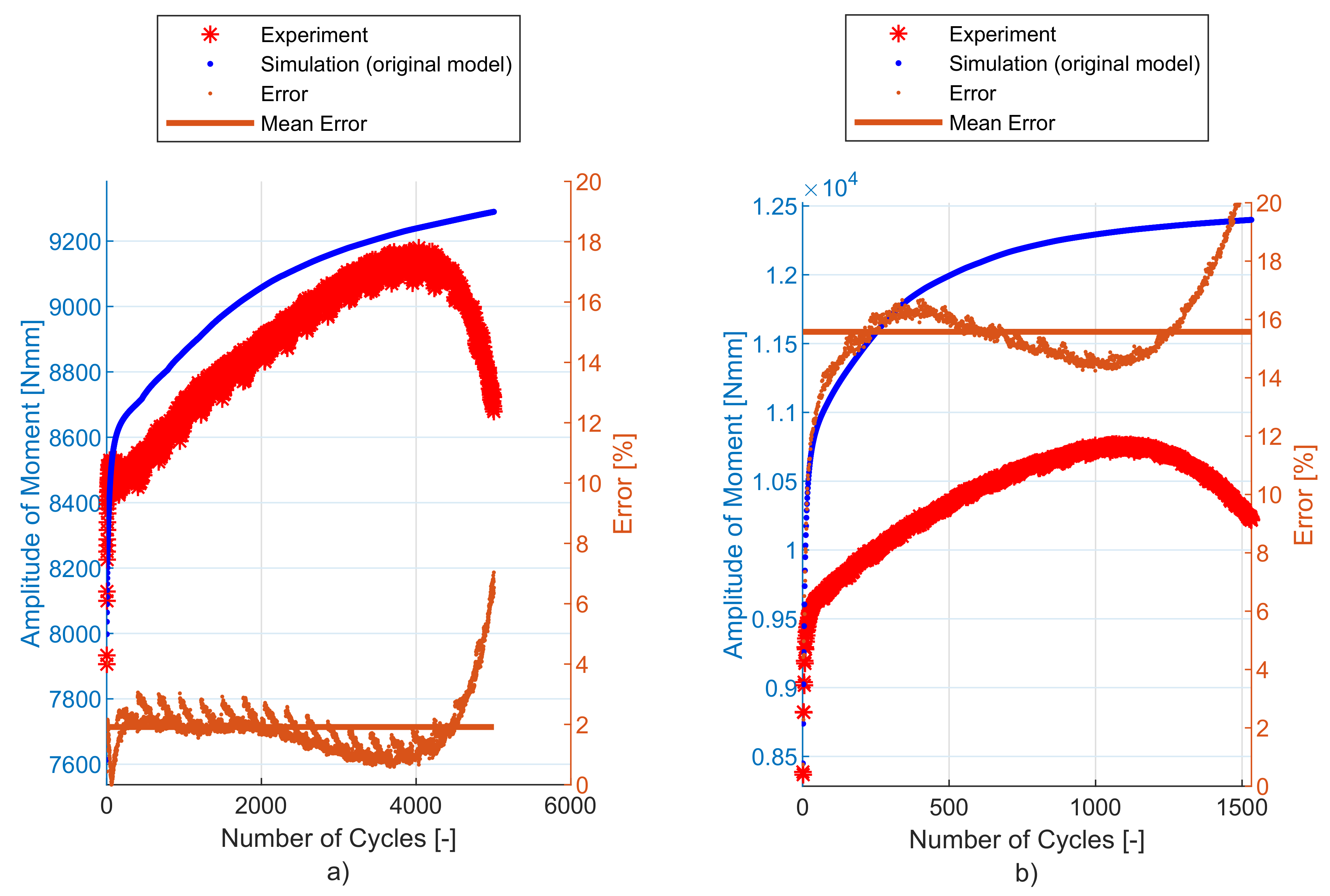

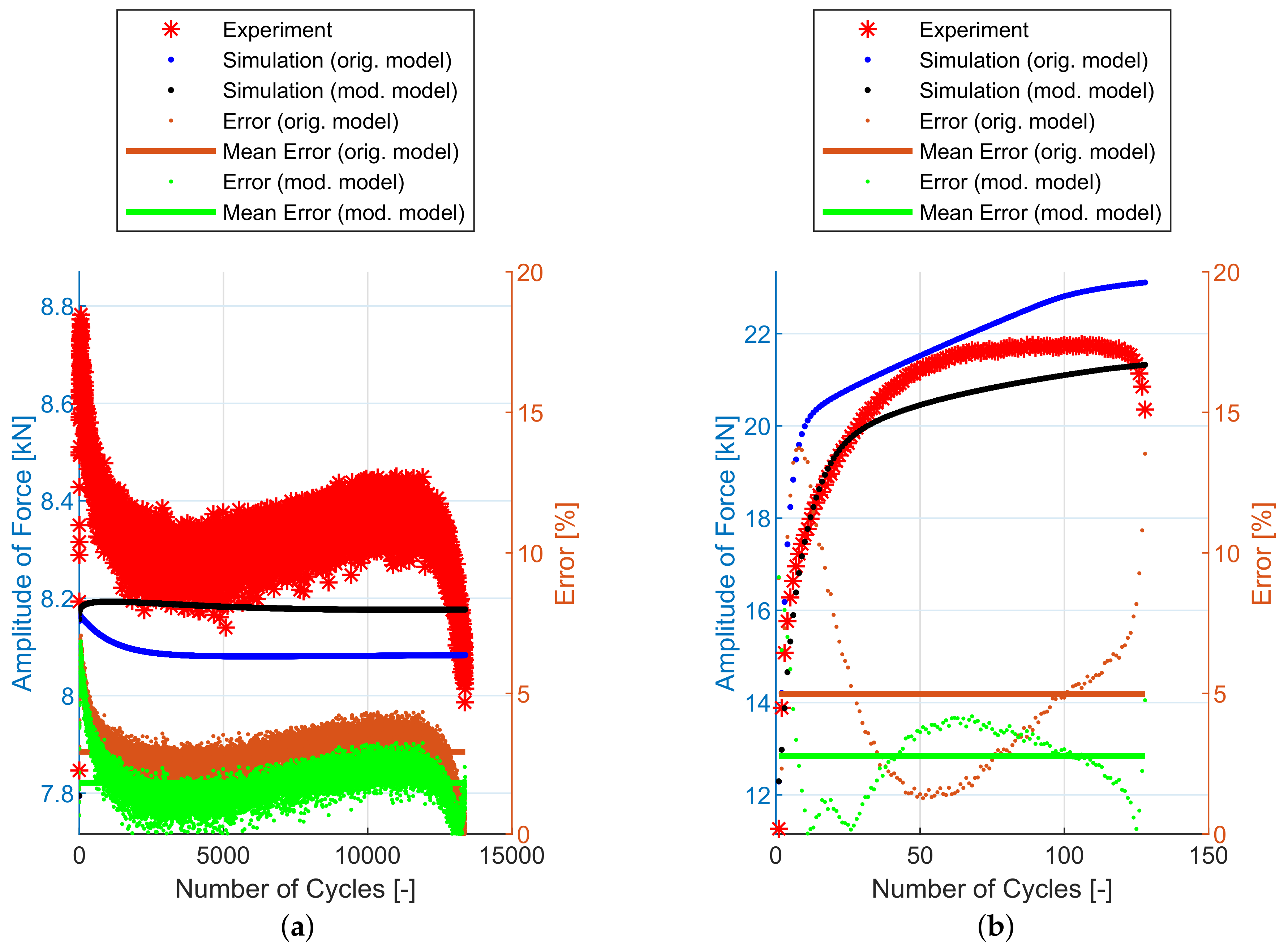

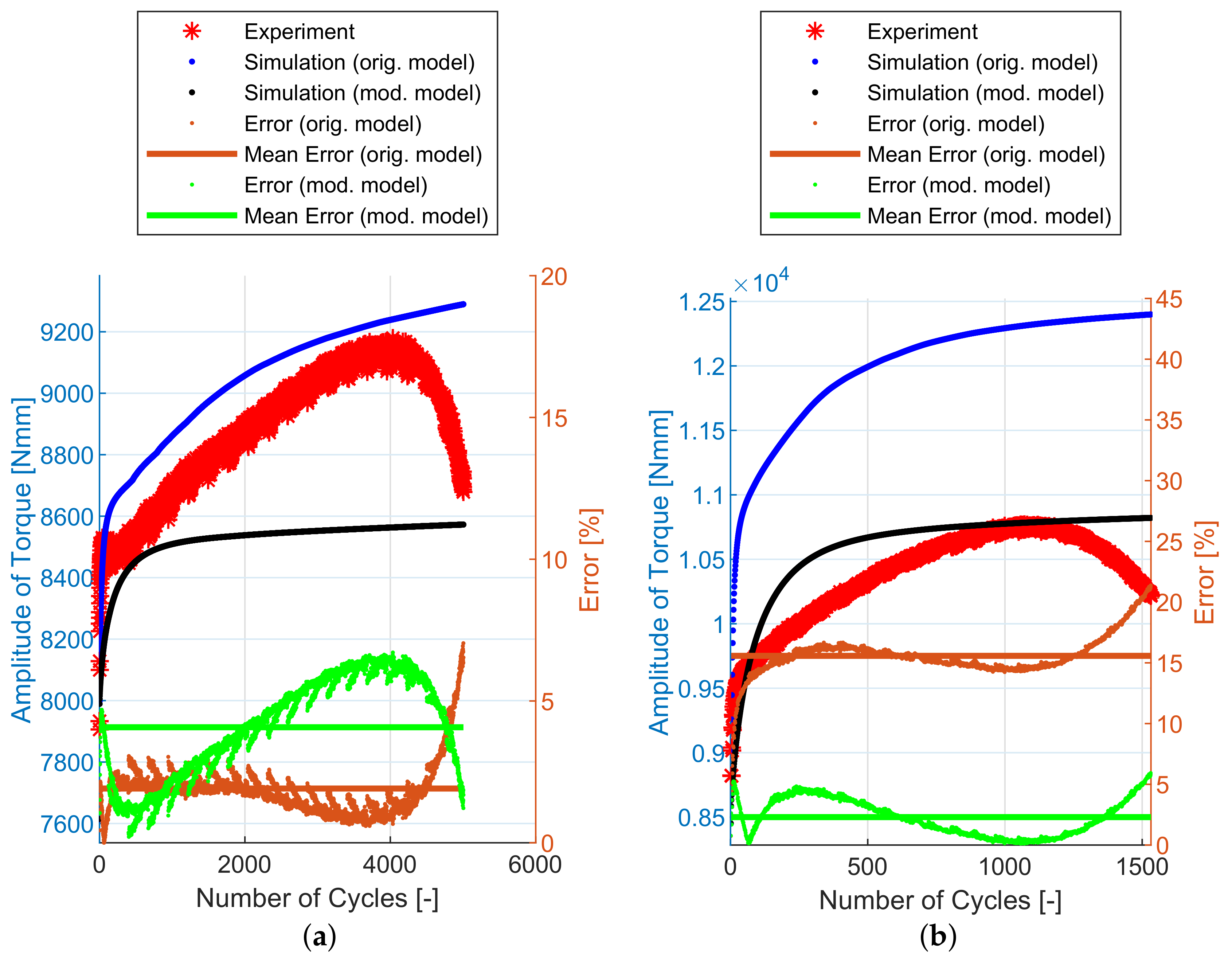

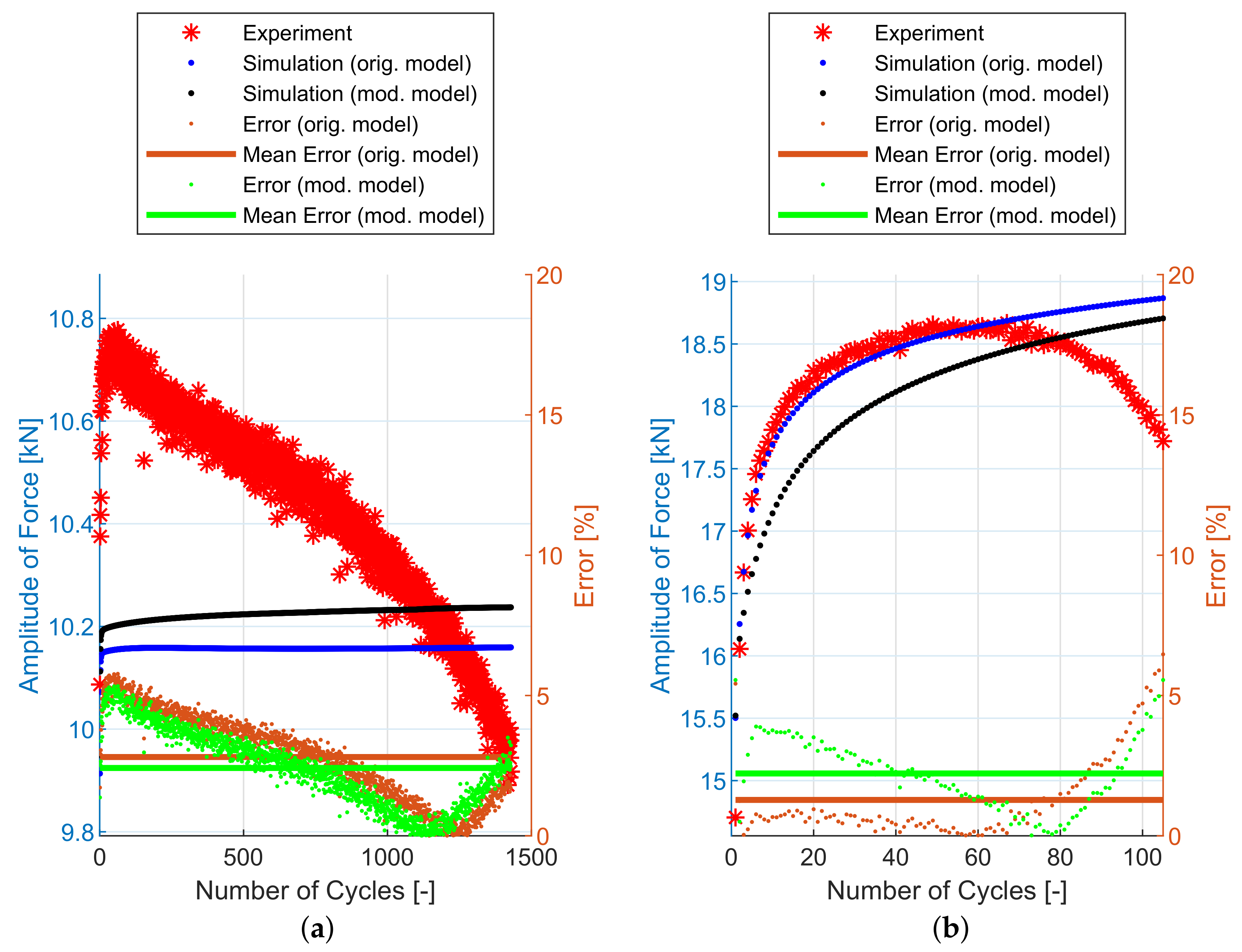

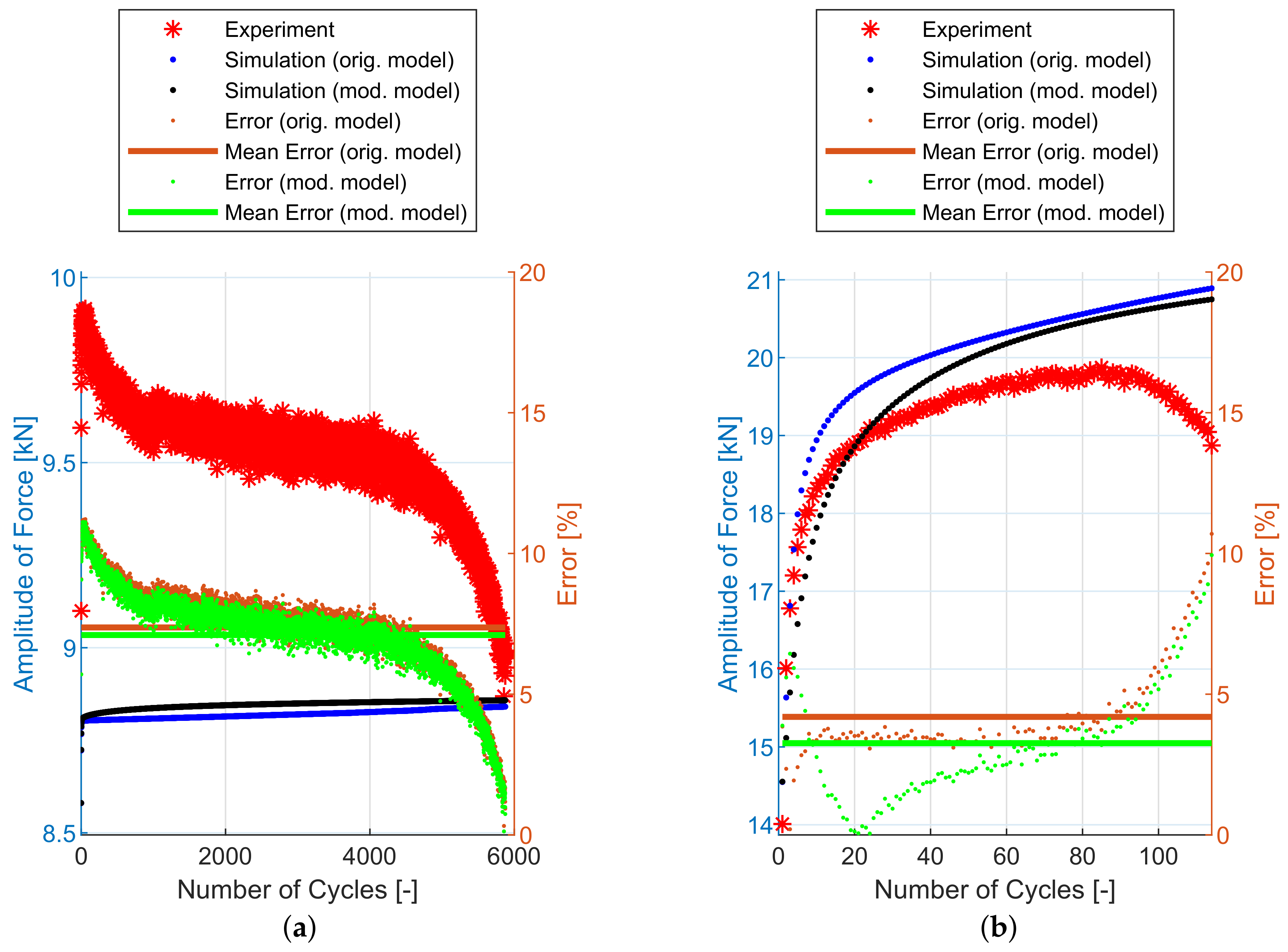

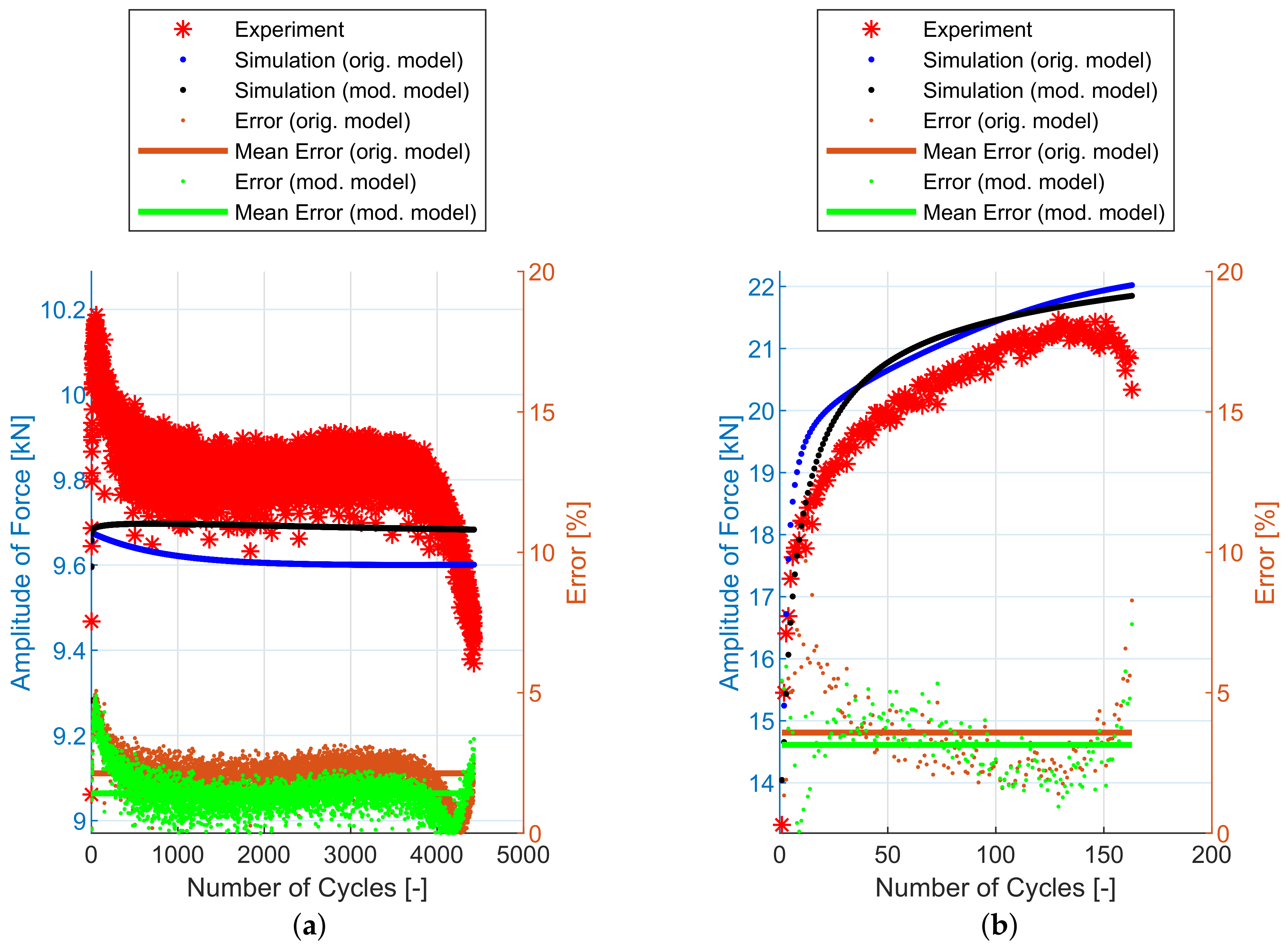

3. Constitutive Model with Strain Range Dependency

3.1. Cyclic Plasticity and Memory Surface

3.2. Isotropic Hardening

3.3. Kinematic Hardening

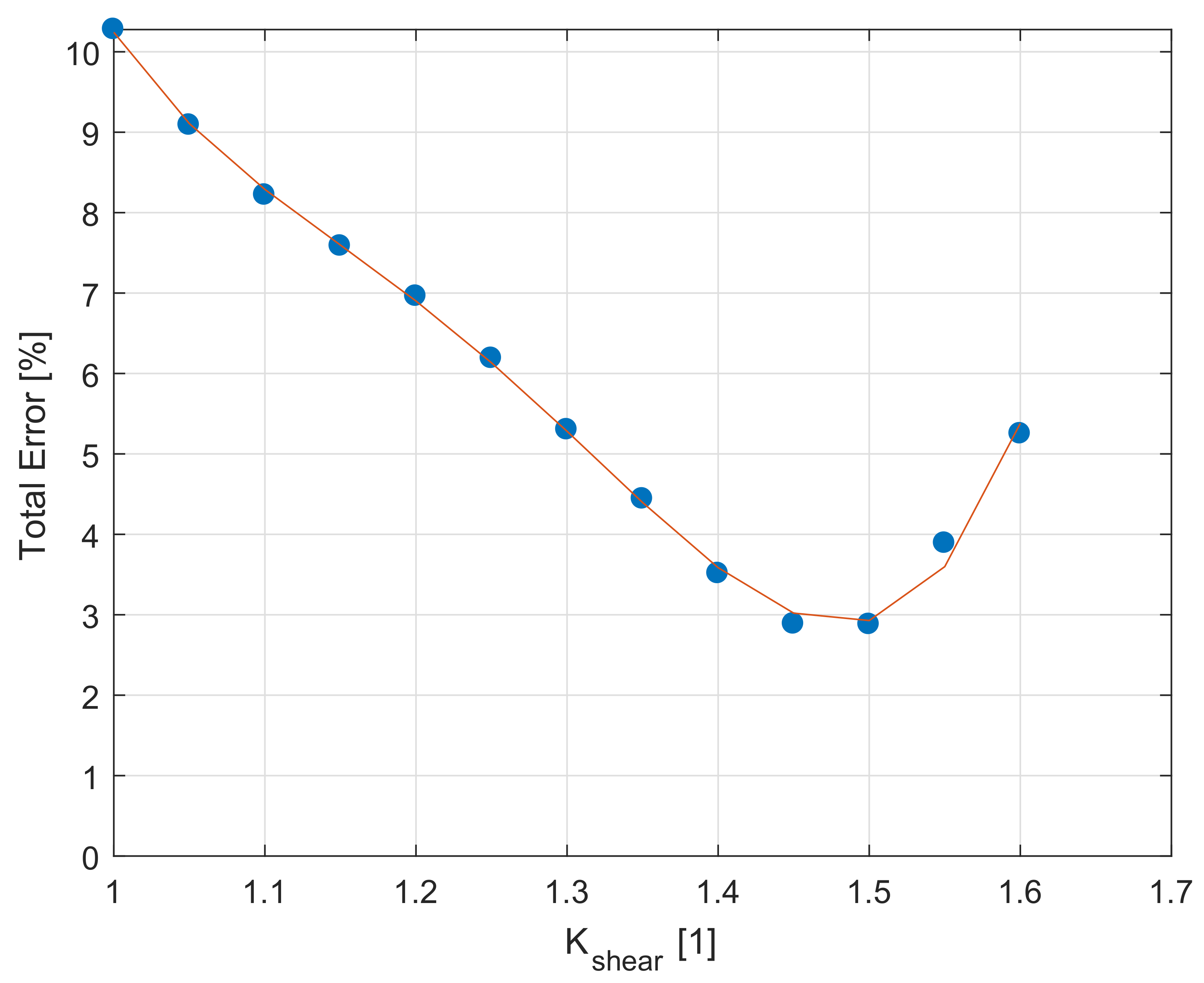

3.4. Modification for Torsional Loading

4. Identification of Material Parameters

5. FE Simulations

6. Experimental and Simulation Results

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DIC | digital image correlation |

| IDF | identification specimen series |

| FE | finite element |

| FEM | finite element method |

| UG | uniform-gage |

Appendix A. Boundary Conditions of Simulations

| Specimen Name | Geometry Type | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| IDF-1 | UG | 0.030 | 37509 |

| IDF-2 | UG | 0.050 | 4285 |

| IDF-3 | UG | 0.075 | 916 |

| IDF-4 | UG | 0.100 | 580 |

| IDF-5 | UG | 0.125 | 254 |

| IDF-6 | E9 | 0.132 | 159 |

| IDF-7 | E9 | 0.154 | 381 |

| IDF-8 | E9 | 0.176 | 370 |

| IDF-9 | E9 | 0.198 | 161 |

| IDF-10 | E9 | 0.245 | 156 |

| IDF-11 | E9 | 0.264 | 124 |

| IDF-12 | E9 | 0.353 | 93 |

| Specimen Name | Geometry Type | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| E9-1 | E9 | 0.0447 | 13382 |

| E9-2 | E9 | 0.0446 | 15104 |

| E9-3 | E9 | 0.0662 | 4053 |

| E9-4 | E9 | 0.0662 | 3887 |

| E9-5 | E9 | 0.0881 | 1529 |

| E9-6 | E9 | 0.0880 | 1853 |

| E9-7 | E9 | 0.1100 | 1158 |

| E9-8 | E9 | 0.1100 | 631 |

| E9-9 | E9 | 0.1320 | 748 |

| E9-10 | E9 | 0.1540 | 546 |

| E9-11 | E9 | 0.1770 | 406 |

| E9-12 | E9 | 0.1980 | 332 |

| E9-13 | E9 | 0.2200 | 253 |

| E9-14 | E9 | 0.2420 | 181 |

| E9-15 | E9 | 0.2420 | 195 |

| E9-16 | E9 | 0.2640 | 220 |

| E9-17 | E9 | 0.3520 | 128 |

| Specimen Name | Geometry Type | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| NT-1 | NT | 0.8703 | 5006 |

| NT-2 | NT | 0.8694 | 6894 |

| NT-3 | NT | 1.1423 | 2222 |

| NT-4 | NT | 1.1414 | 2289 |

| NT-5 | NT | 1.4031 | 2045 |

| NT-6 | NT | 1.3772 | 1532 |

| NT-7 | NT | 1.6554 | 1170 |

| NT-8 | NT | 2.1492 | 925 |

| Specimen Name | Geometry Type | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| R1.2-1 | R1.2 | 0.0245 | 1429 |

| R1.2-2 | R1.2 | 0.0246 | 946 |

| R1.2-3 | R1.2 | 0.0326 | 715 |

| R1.2-4 | R1.2 | 0.0406 | 523 |

| R1.2-5 | R1.2 | 0.0407 | 490 |

| R1.2-6 | R1.2 | 0.0489 | 290 |

| R1.2-7 | R1.2 | 0.0485 | 356 |

| R1.2-8 | R1.2 | 0.0560 | 241 |

| R1.2-9 | R1.2 | 0.0563 | 256 |

| R1.2-10 | R1.2 | 0.0639 | 134 |

| R1.2-11 | R1.2 | 0.0642 | 202 |

| R1.2-12 | R1.2 | 0.0721 | 171 |

| R1.2-13 | R1.2 | 0.0718 | 164 |

| R1.2-14 | R1.2 | 0.0794 | 112 |

| R1.2-15 | R1.2 | 0.0868 | 145 |

| R1.2-16 | R1.2 | 0.0869 | 114 |

| R1.2-17 | R1.2 | 0.0945 | 96 |

| R1.2-18 | R1.2 | 0.0944 | 105 |

| Specimen Name | Geometry Type | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| R2.5-1 | R2.5 | 0.0228 | 5875 |

| R2.5-2 | R2.5 | 0.0341 | 1245 |

| R2.5-3 | R2.5 | 0.0340 | 1041 |

| R2.5-4 | R2.5 | 0.0454 | 607 |

| R2.5-5 | R2.5 | 0.0454 | 761 |

| R2.5-6 | R2.5 | 0.0568 | 378 |

| R2.5-7 | R2.5 | 0.0567 | 429 |

| R2.5-8 | R2.5 | 0.0718 | 242 |

| R2.5-9 | R2.5 | 0.0679 | 346 |

| R2.5-10 | R2.5 | 0.0794 | 265 |

| R2.5-11 | R2.5 | 0.0791 | 212 |

| R2.5-12 | R2.5 | 0.0904 | 210 |

| R2.5-13 | R2.5 | 0.0903 | 221 |

| R2.5-14 | R2.5 | 0.1015 | 205 |

| R2.5-15 | R2.5 | 0.1015 | 163 |

| R2.5-16 | R2.5 | 0.1126 | 189 |

| R2.5-17 | R2.5 | 0.1126 | 156 |

| R2.5-18 | R2.5 | 0.1237 | 132 |

| R2.5-19 | R2.5 | 0.1237 | 129 |

| R2.5-20 | R2.5 | 0.1419 | 106 |

| R2.5-21 | R2.5 | 0.1346 | 114 |

| Specimen Name | Geometry Type | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| R5-1 | R5 | 0.0308 | 4427 |

| R5-2 | R5 | 0.0461 | 1700 |

| R5-3 | R5 | 0.0457 | 1072 |

| R5-4 | R5 | 0.0603 | 733 |

| R5-5 | R5 | 0.0589 | 953 |

| R5-6 | R5 | 0.0727 | 623 |

| R5-7 | R5 | 0.0747 | 527 |

| R5-8 | R5 | 0.0893 | 342 |

| R5-9 | R5 | 0.0869 | 543 |

| R5-10 | R5 | 0.1050 | 297 |

| R5-12 | R5 | 0.1010 | 374 |

| R5-13 | R5 | 0.1154 | 264 |

| R5-14 | R5 | 0.1156 | 290 |

| R5-15 | R5 | 0.1146 | 228 |

| R5-16 | R5 | 0.1287 | 152 |

| R5-17 | R5 | 0.1276 | 272 |

| R5-18 | R5 | 0.1418 | 179 |

| R5-19 | R5 | 0.1467 | 155 |

| R5-20 | R5 | 0.1403 | 177 |

| R5-21 | R5 | 0.1540 | 163 |

| R5-22 | R5 | 0.1531 | 174 |

| R5-23 | R5 | 0.1663 | 144 |

| R5-24 | R5 | 0.1685 | 189 |

| R5-25 | R5 | 0.1652 | 163 |

Appendix B. Abaqus USDFLD Subroutine

Appendix B.1. Full Fortran Code of Abaqus USDFLD Subroutine

C Material model by Miro Fumfera C

C version 2019-11-10 C

CCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCC

C USDFLD Subroutine for 08Ch18N10T Austenitic Stainless Steel

C Original modely by Radim Halama

C modified by Miro Fumfera for 08Ch18N10T

SUBROUTINE USDFLD(FIELD,STATEV,PNEWDT,DIRECT,T,CELENT,

1 TIME,DTIME,CMNAME,ORNAME,NFIELD,NSTATV,NOEL,NPT,LAYER,

2 KSPT,KSTEP,KINC,NDI,NSHR,COORD,JMAC,JMATYP,MATLAYO,LACCFLA)

INCLUDE 'ABA_PARAM.INC'

CHARACTER*80 CMNAME,ORNAME

CHARACTER*3 FLGRAY(15)

DIMENSION FIELD(NFIELD),STATEV(NSTATV),DIRECT(3,3),T(3,3),TIME(2)

DIMENSION ARRAY(15),JARRAY(15),JMAC(*),JMATYP(*),COORD(*)

parameter ZERO=0D0,ONE=1D0,TWO=2D0,THREE=3D0,TOLER=1D-12,

+ NTENS=6 !NTENS=4 for Axisymetric, NTENS=6 for 3D

real*8 RMused,RM,RMmax,RMmin,oRM,dRM, RMRused,RMR,oRMR,dRMR,

+ heavisideG,DDP,G,DirVec(NTENS),DirVecR(NTENS)

real*8 ALPHAv(NTENS),dALPHA1v(NTENS),ALPHA1v(NTENS),

+ dALPHA2v(NTENS),ALPHA2v(NTENS),dALPHA3v(NTENS),ALPHA3v(NTENS),

+ dALPHAv(NTENS),oALPHAv(NTENS),magALPHAv

real*8 ALPHAr(NTENS),dALPHA1r(NTENS),ALPHA1r(NTENS),

+ dALPHA2r(NTENS),ALPHA2r(NTENS),dALPHA3r(NTENS),ALPHA3r(NTENS),

+ dALPHAr(NTENS),oALPHAr(NTENS),magALPHAr

real*8 EPLAS(NTENS),oEPLAS(NTENS),dEPLAS(NTENS),EQPLAS,oEQPLAS,

+ dEQPLAS,FLOW(NTENS)

real*8 R,oR,dR,AR,BR,CR,ER

real*8 PhiInfty,dPHIcyc,PHIcyc,oPHIcyc,PHI0,PHI

real*8 AInfty,BInfty,CInfty,DInfty,EInfty

real*8 AOmega,BOmega,COmega

real*8 KShear

real*8 C1,GAMMA1,C2,GAMMA2,C3,GAMMA3

integer K1,iEPLAS,iALPHA1v,iALPHA2v,iALPHA3v,iEQPLAS,iRM,iPHI,

+ iPHIcyc,iALPHAv,iR,iFIELD1,iFIELD2,iALPHA1r,iALPHA2r,iALPHA3r,

+ iRMR,iALPHAr

parameter(iEPLAS=7,iALPHA1v=31,iALPHA2v=37,iALPHA3v=43,iEQPLAS=49,

+ iR=50,iRM=51,iPHI=52,iPHIcyc=53,iPhiInfty=54,iRMR=61,iALPHA1r=71,

+ iALPHA2r=77,iALPHA3r=83,iRMRused=95,iRMused=96,iALPHAv=97,

+ iALPHAr=94,iFIELD1=98,iFIELD2=99)

C Material parameters

C1 = 6.339971e+04

GAMMA1 = 1.485569e+02

C2 = 9.999778e+03

GAMMA2 = 9.113512e+02

C3 = 2000

GAMMA3 = 0

SYIELD = 150

PHI0 = 2.317802e+00

AInfty = -1.312737e-09

BInfty = 1.798138e-06

CInfty = -8.670490e-04

DInfty = 1.667770e-01

EInfty = -1.060028e+01

RMmin = 1.305410e+02

RMmax = 5.065918e+02

BR = 3.011316e-01

CR = 1.486489e-01

ER = 1.181843e-02

AOmega = 0

BOmega = 2.002387e-13

COmega = -4.859126e+00

KShear = 1.50

C get PE components

call GETVRM('PE',ARRAY,JARRAY,FLGRAY,JRCD,JMAC,JMATYP,

+ MATLAYO,LACCFLA)

C EQPLAS

EQPLAS = ARRAY(7)

oEQPLAS = STATEV(iEQPLAS)

dEQPLAS = EQPLAS - oEQPLAS

C get PE

do K1=1,NTENS

oEPLAS(K1) = STATEV(iEPLAS-1+K1)

EPLAS(K1) = ARRAY(K1)

dEPLAS(K1) = EPLAS(K1) - oEPLAS(K1)

enddo

C get ALPHAv

do K1=1,NTENS

ALPHA1v(K1) = STATEV(iALPHA1v-1+K1)

ALPHA2v(K1) = STATEV(iALPHA2v-1+K1)

ALPHA3v(K1) = STATEV(iALPHA3v-1+K1)

oALPHAv(K1) = STATEV(iALPHAv-1+K1)

ALPHA1r(K1) = STATEV(iALPHA1r-1+K1)

ALPHA2r(K1) = STATEV(iALPHA2r-1+K1)

ALPHA3r(K1) = STATEV(iALPHA3r-1+K1)

oALPHAr(K1) = STATEV(iALPHAr-1+K1)

enddo

C get FLOW vector

if(dEQPLAS.gt.ZERO) then

do K1=1,NDI

FLOW(K1) = dEPLAS(K1)/dEQPLAS

enddo

do K1=NDI+1,NTENS

FLOW(K1) = dEPLAS(K1)/TWO/dEQPLAS

enddo

else

do K1=1,NTENS

FLOW(K1) = ZERO

enddo

endif

C RM

RM = STATEV(iRM)

oRM = RM

C dALPHAv

do K1=1, NDI

dALPHA1v(K1) = (TWO/THREE*C1*dEQPLAS*FLOW(K1) -

+ GAMMA1*ALPHA1v(K1)*dEQPLAS)/(ONE+GAMMA1*dEQPLAS)

dALPHA2v(K1) = (TWO/THREE*C2*dEQPLAS*FLOW(K1) -

+ GAMMA2*ALPHA2v(K1)*dEQPLAS)/(ONE+GAMMA2*dEQPLAS)

dALPHA3v(K1) = (TWO/THREE*C3*dEQPLAS*FLOW(K1) -

+ GAMMA3*ALPHA3v(K1)*dEQPLAS)/(ONE+GAMMA3*dEQPLAS)

ALPHAv(K1) = (ALPHA1v(K1)+dALPHA1v(K1)) +

+ (ALPHA2v(K1)+dALPHA2v(K1)) + (ALPHA3v(K1)+dALPHA3v(K1))

!dALPHAv(K1) = ALPHAv(K1)-oALPHAv(K1)

dALPHAv(K1) = dALPHA1v(K1) + dALPHA2v(K1) + dALPHA3v(K1)

enddo

do K1=NDI+1, NTENS

dALPHA1v(K1) = (TWO/THREE*C1*dEQPLAS*FLOW(K1) -

+ GAMMA1*KShear*ALPHA1v(K1)*dEQPLAS)/(ONE+GAMMA1*dEQPLAS)

dALPHA2v(K1) = (TWO/THREE*C2*dEQPLAS*FLOW(K1) -

+ GAMMA2*KShear*ALPHA2v(K1)*dEQPLAS)/(ONE+GAMMA2*dEQPLAS)

dALPHA3v(K1) = (TWO/THREE*C3*dEQPLAS*FLOW(K1) -

+ GAMMA3*KShear*ALPHA3v(K1)*dEQPLAS)/(ONE+GAMMA3*dEQPLAS)

ALPHAv(K1) = (ALPHA1v(K1)+dALPHA1v(K1)) +

+ (ALPHA2v(K1)+dALPHA2v(K1)) + (ALPHA3v(K1)+dALPHA3v(K1))

!dALPHAv(K1) = ALPHAv(K1)-oALPHAv(K1)

dALPHAv(K1) = dALPHA1v(K1) + dALPHA2v(K1) + dALPHA3v(K1)

enddo

do K1=1, NTENS

ALPHA1v(K1) = ALPHA1v(K1) + dALPHA1v(K1)

ALPHA2v(K1) = ALPHA2v(K1) + dALPHA2v(K1)

ALPHA3v(K1) = ALPHA3v(K1) + dALPHA3v(K1)

ALPHAv(K1) = ALPHA1v(K1) + ALPHA2v(K1) + ALPHA3v(K1)

enddo

C magALPHAv

magALPHAv = ZERO

do K1=1, NDI

magALPHAv = magALPHAv + ALPHAv(K1)**2

enddo

do K1=NDI+1, NTENS

magALPHAv = magALPHAv + TWO*ALPHAv(K1)**2

enddo

magALPHAv = sqrt(THREE/TWO*magALPHAv)

C G function

G = magALPHAv - RM

if(magALPHAv.gt.ZERO) then

do K1 = 1, NTENS

DirVec(K1)=ALPHAv(K1)/magALPHAv

enddo

else

do K1 = 1, NTENS

DirVec(K1) = ZERO

enddo

endif

C double dot product DDP

DDP = ZERO

do K1 = 1, NDI

DDP = DDP+DirVec(K1)*dALPHAv(K1)

enddo

do K1 = NDI+1, NTENS

DDP = DDP+TWO*DirVec(K1)*dALPHAv(K1)

enddo

C heaviside function of G

if (G.gt.ZERO) then

heavisideG = ONE

elseif (abs(G).lt.TOLER) then

heavisideG = ONE/TWO

else

heavisideG = ZERO

endif

C memory surface RM

dRM = heavisideG*abs(DDP)

RM = oRM + dRM

if (RM.lt.RMmin) then

RMused = RMmin

elseif (RM.gt.RMmax) then

RMused = RMmax

else

RMused = RM

endif

C RMR

RMR = STATEV(iRMR)

oRMR = RMR

do K1=1, NDI

dALPHA1r(K1) = (TWO/THREE*C1*dEQPLAS*FLOW(K1) -

+ GAMMA1*ALPHA1r(K1)*dEQPLAS)/(ONE+GAMMA1*dEQPLAS)

dALPHA2r(K1) = (TWO/THREE*C2*dEQPLAS*FLOW(K1) -

+ GAMMA2*ALPHA2r(K1)*dEQPLAS)/(ONE+GAMMA2*dEQPLAS)

dALPHA3r(K1) = (TWO/THREE*C3*dEQPLAS*FLOW(K1) -

+ GAMMA3*ALPHA3r(K1)*dEQPLAS)/(ONE+GAMMA3*dEQPLAS)

ALPHAr(K1) = (ALPHA1r(K1)+dALPHA1r(K1)) +

+ (ALPHA2r(K1)+dALPHA2r(K1)) + (ALPHA3r(K1)+dALPHA3r(K1))

!dALPHAr(K1) = ALPHAr(K1)-oALPHAr(K1)

dALPHAr(K1) = dALPHA1r(K1) + dALPHA2r(K1) + dALPHA3r(K1)

enddo

do K1=NDI+1, NTENS

dALPHA1r(K1) = (TWO/THREE*C1*dEQPLAS*FLOW(K1) -

+ GAMMA1*KShear*ALPHA1r(K1)*dEQPLAS)/(ONE+GAMMA1*dEQPLAS)

dALPHA2r(K1) = (TWO/THREE*C2*dEQPLAS*FLOW(K1) -

+ GAMMA2*KShear*ALPHA2r(K1)*dEQPLAS)/(ONE+GAMMA2*dEQPLAS)

dALPHA3r(K1) = (TWO/THREE*C3*dEQPLAS*FLOW(K1) -

+ GAMMA3*KShear*ALPHA3r(K1)*dEQPLAS)/(ONE+GAMMA3*dEQPLAS)

ALPHAr(K1) = (ALPHA1r(K1)+dALPHA1r(K1)) +

+ (ALPHA2r(K1)+dALPHA2r(K1)) + (ALPHA3r(K1)+dALPHA3r(K1))

!dALPHAr(K1) = ALPHAr(K1)-oALPHAr(K1)

dALPHAr(K1) = dALPHA1r(K1) + dALPHA2r(K1) + dALPHA3r(K1)

enddo

do K1=1, NTENS

ALPHA1r(K1) = ALPHA1r(K1) + dALPHA1r(K1)

ALPHA2r(K1) = ALPHA2r(K1) + dALPHA2r(K1)

ALPHA3r(K1) = ALPHA3r(K1) + dALPHA3r(K1)

ALPHAr(K1) = ALPHA1r(K1) + ALPHA2r(K1) + ALPHA3r(K1)

enddo

C magALPHAr

magALPHAr = ZERO

do K1=1, NDI

magALPHAr = magALPHAr + ALPHAr(K1)**2

enddo

do K1=NDI+1, NTENS

magALPHAr = magALPHAr + TWO*ALPHAr(K1)**2

enddo

magALPHAr = sqrt(THREE/TWO*magALPHAr)

C G function

G = magALPHAr - RMR

if(magALPHAr.gt.ZERO) then

do K1 = 1, NTENS

DirVecR(K1)=ALPHAr(K1)/magALPHAr

enddo

else

do K1 = 1, NTENS

DirVecR(K1) = ZERO

enddo

endif

C double dot product DDP

DDP = ZERO

do K1 = 1, NDI

DDP = DDP+DirVecR(K1)*dALPHAr(K1)

enddo

do K1 = NDI+1, NTENS

DDP = DDP+TWO*DirVecR(K1)*dALPHAr(K1)

enddo

C heaviside function of G

if (G.gt.ZERO) then

heavisideG = ONE

elseif (abs(G).lt.TOLER) then

heavisideG = ONE/TWO

else

heavisideG = ZERO

endif

C memory surface RMR

dRMR = heavisideG*abs(DDP)

RMR = oRMR + dRMR

if (RMR.lt.RMmin) then

RMRused = RMmin

elseif (RMR.gt.RMmax) then

RMRused = RMmax

else

RMRused = RMR

endif

C R

oR = STATEV(iR)

AR = CR*exp(ER*RMRused)

dR = AR*((EQPLAS+dEQPLAS)**BR-EQPLAS**BR)

R = oR + dR;

C PHIinfty

PhiInfty = AInfty*RMused**4 + BInfty*RMused**3 +

+ CInfty*RMused**2 + DInfty*RMused + EInfty

C Omega

OMEGA∼= AOmega+BOmega*(RMused)**-COmega

C PHIcyc

oPHIcyc = STATEV(iPHIcyc)

dPHIcyc = OMEGA*(PhiInfty-oPHIcyc)*DEQPLAS

PHIcyc = oPHIcyc + dPHIcyc

C PHI

PHI = PHI0 + PHIcyc

C save STATEV

STATEV(iEQPLAS) = EQPLAS

do K1=1,NTENS

STATEV(iEPLAS-1+K1) = EPLAS(K1)

STATEV(iALPHA1v-1+K1) = ALPHA1v(K1)

STATEV(iALPHA2v-1+K1) = ALPHA2v(K1)

STATEV(iALPHA3v-1+K1) = ALPHA3v(K1)

STATEV(iALPHAv-1+K1) = ALPHAv(K1)

STATEV(iALPHA1r-1+K1) = ALPHA1r(K1)

STATEV(iALPHA2r-1+K1) = ALPHA2r(K1)

STATEV(iALPHA3r-1+K1) = ALPHA3r(K1)

STATEV(iALPHAr-1+K1) = ALPHAr(K1)

STATEV(120+K1) = dALPHAv(K1)

enddo

STATEV(iR) = R

STATEV(iRM) = RM

STATEV(iRMR) = RMR

STATEV(iRMused) = RMused

STATEV(iRMRused) = RMRused

STATEV(iPHIcyc) = PHIcyc

STATEV(iPHI) = PHI

STATEV(iPhiInfty) = PhiInfty

STATEV(127) = SYIELD+R

STATEV(128) = DDP

C FIELD(1)

FIELD(1) = SYIELD+R

STATEV(iFIELD1) = FIELD(1)

C FIELD(2)

FIELD(2) = PHI

STATEV(iFIELD2) = FIELD(2)

RETURN

END

Appendix B.2. Material Parameters Definition in the Abaqus Input File

*Material, name=Material-1

*Depvar

128

*Elastic

210000.0,0.3

*Plastic, dependencies=2, hardening=COMBINED, datatype=PARAMETERS,

number backstresses=3

** Material data as∼a∼function of FIELD1 and∼FIELD2 follows:

SYIELD,C1,GAMMA1,C2,GAMMA2,C3,GAMMA3,FIDEL1,FIELD2

%%

** Material data as∼a∼function of FIELD1 and∼FIELD2 follows: ** ... 250.0,63399.70889,222.83539,9999.77788,1367.02686,2000.0,0.0,250.0,1.5 150.0,63399.70889,237.69108,9999.77788,1458.16199,2000.0,0.0,150.0,1.6 151.0,63399.70889,237.69108,9999.77788,1458.16199,2000.0,0.0,151.0,1.6 ** ...

References

- Halama, R.; Sedlák, J.; Šofer, M. Phenomenological Modelling of Cyclic Plasticity. In Numerical Modelling; Miidla, P., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2012; pp. 329–354. [Google Scholar]

- Halama, R.; Fumfera, J.; Gál, P.; Kumar, T.; Makropulos, A. Modeling the Strain-Range Dependent Cyclic Hardening of SS304 and 08Ch18N10T Stainless Steel with a Memory Surface. Metals 2019, 9, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhang, J. Benchmark experiments and characteristic cyclic plastic deformation behavior. Int. J. Plast. 2008, 24, 1481–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facheris, G.; Janssens, K.G.F.; Foletti, S. Multiaxial fatigue behavior of AISI 316L subjected to strain-controlled and ratcheting paths. Int. J. Fatigue 2014, 68, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C. Nondestructive Evaluation of Strain-Induced Phase Transformation and Damage Accumulation in Austenitic Stainless Steel Subjected to Cyclic Loading. Metals 2018, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borodii, M.; Shukayev, S. Additional cyclic strain hardening and its relation to material structure, mechanical characteristics, and lifetime. Int. J. Fatigue 2007, 29, 1184–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.; Tian, D.J.; Li, J.H.; Sakane, M. Low-cycle fatigue of 316L stainless steel under proportional and nonproportional loadings. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 2016, 39, 850–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, R.; Dunji, Y.; Shouwen, S.; Xu, C. Cyclic deformation of 316L stainless steel and constitutive modeling under non-proportional variable loading path. Int. J. Plast. 2019, 120, 127–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srnec Novak, J.; Benasciutti, D.; De Bona, F.; Stanojevic, A.S.; De Luca, A.; Raffaglio, Y. Estimation of Material Parameters in Nonlinear Hardening Plasticity Models and Strain Life Curves for CuAg Alloy. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2016, 119, 012020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benallal, A.; Marquis, D. Constitutive Equations for Nonproportional Cyclic Elasto-Viscoplasticity. J. Eng. Mater. Technol. 1987, 109, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, E. A nonproportionality parameter and a cyclic viscoplastic constitutive model taking into account amplitude dependences and memory effects of isotropic hardening. Eur. J. Mech. A/Solids 1994, 13, 155–173. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Sehitoglu, H. Modeling of cyclic ratchetting plasticity, part I: Development of constitutive relations. J. Appl. Mech. 1996, 63, 720–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM Standard E606-92. Standard Practise for Strain-Controlled Fatigue Testing; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Fumfera, J.; Halama, R.; Kuželka, J.; Španiel, M. Strain-Range Dependent Cyclic Plasticity Material Model Calibration for the 08Ch18N10T Steel. In Proceedings of the 33rd Conference with International Participation on Computational Mechanics, Špičák, Czech Republic, 6–8 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Karim, M.; Ohno, N. Kinematic hardening model suitable for ratchetting with steady-state. Int. J. Plast. 2000, 16, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peč, M.; Šebek, F.; Zapletal, J.; Petruška, J.; Hassan, T. Automated calibration of advanced cyclic plasticity model parameters with sensitivity analysis for aluminium alloy 2024-T351. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2019, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halama, R.; Pagáč, M.; Paška, Z.; Pavlíček, P.; Chen, X. Ratcheting Behaviour of 3D Printed and Conventionally Produced SS316L Material. In Proceedings of the ASME 2019 Pressure Vessels & Piping Conference PVP2019, San Antonio, TX, USA, 14–19 July 2019. Paper Number PVP2019-93384. [Google Scholar]

| 210,000 | 0.3 | 150 | 63,400 | 148.6 | 10,000 |

| 911.4 | 2000 | 0 | |||

| 130.54 | |||||

| 0 | −4.8591 | 506.59 | 2.3178 | 1.5 |

| Specimen Name | Orig. Model Mean Err. [%] | Mod. Model Mean Err. [%] | Specimen Name | Orig. Model Mean Err. [%] | Mod. Model Mean Err. [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E9-1 | 2.9226 | 1.8207 | E9-10 | 7.8144 | 8.8757 |

| E9-2 | 2.3311 | 1.2756 | E9-11 | 2.5028 | 3.9003 |

| E9-3 | 2.4027 | 1.1938 | E9-12 | 4.3523 | 6.5915 |

| E9-4 | 1.6977 | 0.7773 | E9-13 | 4.0929 | 3.4343 |

| E9-5 | 8.0687 | 7.0447 | E9-14 | 2.1610 | 3.8515 |

| E9-6 | 8.8658 | 7.4521 | E9-15 | 2.9195 | 2.9485 |

| E9-7 | 11.7310 | 10.4229 | E9-16 | 1.8601 | 2.7524 |

| E9-8 | 3.8241 | 3.9171 | E9-17 | 4.9766 | 2.7579 |

| E9-9 | 9.8245 | 9.5508 |

| Specimen Name | Orig. Model Mean Err. [%] | Mod. Model Mean Err. [%] | Specimen Name | Orig. Model Mean Err. [%] | Mod. Model Mean Err. [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NT-1 | 1.9100 | 4.0682 | NT-5 | 14.2137 | 1.3947 |

| NT-2 | 0.8367 | 5.9823 | NT-6 | 15.5549 | 2.2815 |

| NT-3 | 11.2048 | 1.3797 | NT-7 | 13.1168 | 1.5014 |

| NT-4 | 11.1021 | 1.0934 | NT-8 | 8.8054 | 4.7887 |

| Specimen Name | Orig. Model Mean Err. [%] | Mod. Model Mean Err. [%] | Specimen Name | Orig. Model Mean Err. [%] | Mod. Model Mean Err. [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1.2-1 | 2.8075 | 2.4172 | R1.2-10 | 1.6518 | 1.7538 |

| R1.2-2 | 3.7011 | 3.1679 | R1.2-11 | 2.0827 | 2.2332 |

| R1.2-3 | 2.2438 | 2.2027 | R1.2-12 | 3.9411 | 3.2028 |

| R1.2-4 | 2.8530 | 2.7056 | R1.2-13 | 2.5308 | 3.1540 |

| R1.2-5 | 2.8984 | 2.7105 | R1.2-14 | 1.4521 | 1.8444 |

| R1.2-6 | 4.7877 | 4.4405 | R1.2-15 | 3.6781 | 2.6435 |

| R1.2-7 | 1.4888 | 1.4897 | R1.2-16 | 1.5820 | 1.9106 |

| R1.2-8 | 7.1382 | 6.7943 | R1.2-17 | 1.6089 | 2.5930 |

| R1.2-9 | 2.4171 | 2.2355 | R1.2-18 | 1.2789 | 2.2219 |

| Specimen Name | Orig. Model Mean Err. [%] | Mod. Model Mean Err. [%] | Specimen Name | Orig. Model Mean Err. [%] | Mod. Model Mean Err. [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2.5-1 | 7.3714 | 7.1025 | R2.5-12 | 2.1944 | 1.6489 |

| R2.5-2 | 8.1586 | 7.6327 | R2.5-13 | 1.2466 | 1.0057 |

| R2.5-3 | 9.1468 | 8.6587 | R2.5-14 | 8.7778 | 9.1473 |

| R2.5-4 | 6.8139 | 6.8130 | R2.5-15 | 2.6624 | 3.0678 |

| R2.5-5 | 6.6714 | 6.6118 | R2.5-16 | 1.4643 | 1.3563 |

| R2.5-6 | 9.9838 | 9.1708 | R2.5-17 | 0.9873 | 1.5697 |

| R2.5-7 | 4.3249 | 3.4860 | R2.5-18 | 1.4020 | 1.4515 |

| R2.5-8 | 3.8551 | 3.8250 | R2.5-19 | 1.6099 | 2.6423 |

| R2.5-9 | 1.0034 | 0.9027 | R2.5-20 | 0.9634 | 2.4069 |

| R2.5-10 | 4.7921 | 4.9816 | R2.5-21 | 4.1944 | 3.2605 |

| R2.5-11 | 1.9673 | 2.1464 |

| Specimen Name | Orig. Model Mean Err. [%] | Mod. Model Mean Err. [%] | Specimen Name | Orig. Model Mean Err. [%] | Mod. Model Mean Err. [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R5-1 | 2.1303 | 1.4186 | R5-13 | 6.7479 | 6.8700 |

| R5-2 | 2.0673 | 1.8112 | R5-14 | 5.1055 | 5.4414 |

| R5-3 | 0.7021 | 0.8284 | R5-15 | 1.3043 | 1.4251 |

| R5-4 | 0.9757 | 0.9284 | R5-16 | 1.1829 | 1.3661 |

| R5-5 | 1.4847 | 1.4209 | R5-17 | 3.6903 | 3.6048 |

| R5-6 | 1.7435 | 1.6993 | R5-18 | 3.1399 | 2.9518 |

| R5-7 | 2.9066 | 2.7548 | R5-19 | 6.1649 | 6.1226 |

| R5-8 | 5.3372 | 5.4106 | R5-20 | 2.8263 | 2.6683 |

| R5-9 | 4.9004 | 4.5530 | R5-21 | 1.0485 | 1.2882 |

| R5-10 | 2.3623 | 2.6227 | R5-22 | 8.2167 | 7.6119 |

| R5-11 | 7.0110 | 6.8065 | R5-23 | 2.2011 | 1.6441 |

| R5-12 | 2.3912 | 3.1025 | R5-24 | 3.5803 | 3.1425 |

| Geometry | The Original Nodel [2] Total Error [%] | The Modified Model Total Error [%] |

|---|---|---|

| E9 | 4.84 | 4.61 |

| NT | 9.60 | 2.85 |

| R1.2 | 2.79 | 2.76 |

| R2.5 | 4.27 | 4.23 |

| R5 | 3.30 | 3.23 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fumfera, J.; Halama, R.; Procházka, R.; Gál, P.; Španiel, M. Strain Range Dependent Cyclic Hardening of 08Ch18N10T Stainless Steel—Experiments and Simulations. Materials 2019, 12, 4243. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma12244243

Fumfera J, Halama R, Procházka R, Gál P, Španiel M. Strain Range Dependent Cyclic Hardening of 08Ch18N10T Stainless Steel—Experiments and Simulations. Materials. 2019; 12(24):4243. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma12244243

Chicago/Turabian StyleFumfera, Jaromír, Radim Halama, Radek Procházka, Petr Gál, and Miroslav Španiel. 2019. "Strain Range Dependent Cyclic Hardening of 08Ch18N10T Stainless Steel—Experiments and Simulations" Materials 12, no. 24: 4243. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma12244243

APA StyleFumfera, J., Halama, R., Procházka, R., Gál, P., & Španiel, M. (2019). Strain Range Dependent Cyclic Hardening of 08Ch18N10T Stainless Steel—Experiments and Simulations. Materials, 12(24), 4243. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma12244243