Abstract

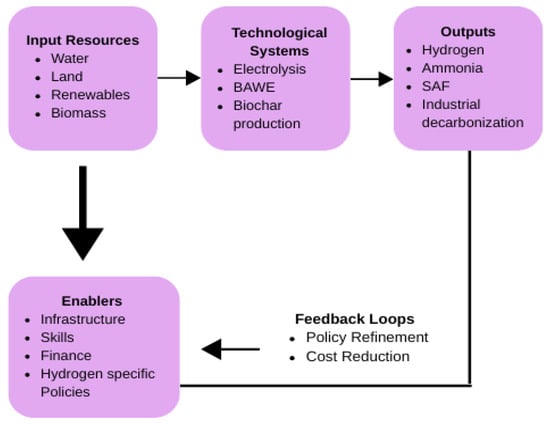

Growing global energy demand and the imperative to reduce greenhouse gas emissions have accelerated interest in low-carbon hydrogen production. This review synthesizes advances at the intersection of electrolysis and biomass pyrolysis, with particular emphasis on the emerging role of biochar as a functional and catalytic material that enhances hydrogen generation while supporting sustainable bioenergy value chains. Recent evidence shows that biochar-assisted water electrolysis (BAWE) can lower energy requirements, improve reaction efficiency, and valorize locally available biomass resources. This positions biochar as a promising complement to conventional green hydrogen pathways. The review further assesses South Africa’s evolving policy and regulatory architecture by highlighting the country’s ambition to build a competitive hydrogen economy alongside structural constraints such as limited electrolyzer manufacturing capability, inadequate infrastructure, and insufficiently targeted frameworks for technology scale-up. The review analysis therefore emphasizes that integrating biomass-derived materials into hydrogen production presents an underexplored yet high-potential route for advancing national decarbonization goals. Strengthened research, development, and innovation systems, supported by coherent and technology-specific policy measures, will be essential for South Africa to unlock the full economic, environmental, and industrial benefits of a green hydrogen and biochar-integrated future.

1. Introduction

The rising global demand for energy, the depletion of fossil resources, and the accelerating impacts of climate change have intensified efforts to identify sustainable and renewable energy pathways. Although fossil fuels have historically supported economic growth, their continued use presents persistent challenges, including high greenhouse gas emissions, exposure to price volatility, and long-term resource constraints [1]. These pressures have shifted attention toward renewable energy systems, particularly bioenergy, which converts organic materials such as agricultural residues, forestry waste, and municipal biomass into useful energy carriers. Bioenergy contributes to both emissions reduction and waste management, thus making it an increasingly important component of national decarbonization strategies [2].

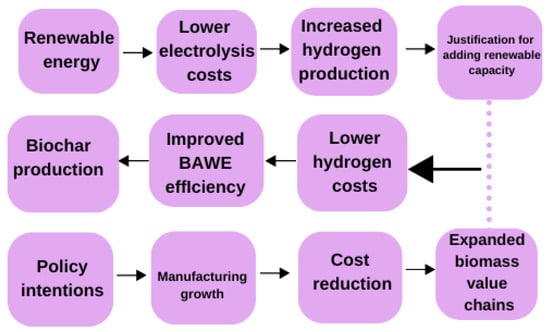

Within this broader renewable energy landscape, green hydrogen has gained prominence as a versatile energy carrier capable of decarbonizing sectors that are otherwise difficult to electrify, including heavy transportation and industrial feedstock production. Conventional hydrogen production methods, mostly steam methane reforming and partial oxidation, remain carbon-intensive [3], whereas water electrolysis enables near-zero-carbon hydrogen when powered by renewable electricity. Emerging research demonstrates growing interest in hybrid approaches that integrate biomass-derived materials within electrolysis systems. For example, biochar-assisted water electrolysis (BAWE) reduces energy consumption and creates opportunities for valorizing biomass residues, thus illustrating a converging trend between biomass utilization and green hydrogen technologies.

Biochar, a carbon-rich product of biomass pyrolysis, has become particularly relevant in this context. Pyrolysis not only yields fuels and value-added chemicals but also limits pollutant formation relative to other thermochemical processes [4]. The physicochemical characteristics of biochar, which are high surface area, tunable porosity, and stable carbon structure, enable its application as a support material for electrocatalysts, thus potentially enhancing reaction efficiency and lowering system costs [5]. As studies increasingly investigate biochar’s catalytic and electrochemical roles, a pattern emerges: biochar offers both functional performance advantages and environmental benefits through waste reduction and carbon retention.

Integrating biochar with electrolysis technologies also creates opportunities for local research, development, and innovation, which are essential for industrial scaling and long-term competitiveness in green hydrogen production [6]. For countries such as South Africa, with abundant biomass residues and strong ambitions to build a green hydrogen economy, the combined use of bioenergy, biomass processing, and biochar-enabled hydrogen production represents a potential pathway to align industrial development with climate commitments.

This review, therefore, aims to critically examine the intersection between electrolysis and biomass pyrolysis pathways for the sustainable production of green hydrogen. The unique contribution of this review lies in its integrated assessment of biomass conversion using locally available resources as a cost-reducing and environmentally beneficial pathway within South Africa’s energy transition. In doing so, it highlights the potential of biochar as a value-added product within the green hydrogen value chain while exploring its overall potential, and it also highlights recent research advances in biochar-assisted hydrogen production. Unlike existing studies, which do not bridge the gap between green hydrogen pathways and policy perspective, this review explicitly combines electrolysis and biomass pyrolysis routes for green hydrogen production with an evaluation of the policy and regulatory landscape in South Africa, thereby considering how current frameworks support, or could better enhance research, development, and innovation in green hydrogen technologies. By connecting technological developments with policy and industrial considerations, particularly in the South African context, this review highlights perspectives that have been largely underexplored in the literature.

2. Advances in Renewable Energy and Green Hydrogen Production Technologies

South Africa faces increasing pressure to reduce its carbon footprint while simultaneously addressing the energy trilemma of security, equity, and environmental sustainability. The country’s substantial solar, wind, and biomass resources create opportunities to diversify its energy system and stimulate local economic development. Solar photovoltaics (PV), onshore wind systems, concentrated solar power (CSP), and biomass conversion processes, such as pyrolysis, enable the generation of electricity with comparatively low environmental impact. Solar PV converts incident radiation into electricity, wind turbines harness kinetic energy from atmospheric flows, and CSP plants convert solar heat into thermal power. With an average annual solar irradiation of approximately 2025 kWh m−2 [7], and favourable wind conditions averaging 6 m s−1 at 100 m hub height, South Africa has the technical potential to generate more than 60 TWh of wind energy annually [8]. The literature demonstrates extensive progress in the deployment and optimization of solar and wind technologies. However, a recurring pattern across studies is the limited research emphasis on biomass utilization relative to other renewable energy sources. This gap persists despite the extensive use of biomass across the African continent, primarily sourced from wood residues, agricultural by-products, and municipal organic waste and mainly used for heating and cooking. South Africa is among the users of biofuels on the continent, and projections indicate an increasing demand for bioenergy over the next two decades [9,10]. The limited innovation-oriented research on biomass conversion therefore represents a missed opportunity, particularly given its relevance for waste management, rural development, and low-carbon fuel production.

Given its resource base, South Africa is well positioned to develop a competitive green hydrogen industry capable of supporting domestic decarbonization and generating export revenue. Growing interest in hydrogen, especially green hydrogen, reflects the country’s advantages such as access to low-cost renewable energy, large platinum group metal reserves for electrolyzer technologies, and an emerging policy focus on hydrogen industrialization. These factors collectively enhance South Africa’s prospects across the green hydrogen value chain. However, the literature consistently shows that the cost of green hydrogen remains a central barrier, and sustained advances in catalysis, electrolyzer efficiency, and system integration are required to achieve cost reductions. As hydrogen gains relevance in the global energy transition, research and innovation will play a decisive role in determining whether South Africa can leverage its natural and mineral resources to facilitate a just and inclusive transition to low-carbon energy systems.

2.1. Water Electrolysis Technologies

Water electrolysis is projected to play a major role in supplying clean hydrogen by 2050 for applications in transportation, industrial energy demand, building heating, and carbon utilization pathways. By the same year, hydrogen demand for electrolysis-based production is expected to increase nearly tenfold, driven by growing requirements for low-carbon fuels, chemicals, and energy carriers [11,12]. Hydrogen production routes are commonly categorized by colour codes that reflect their feedstock and carbon intensity: grey hydrogen from fossil fuels without carbon capture, blue hydrogen from fossil fuels with carbon capture and storage, turquoise hydrogen from methane pyrolysis, pink hydrogen from nuclear-powered electrolysis, and green hydrogen from renewable-powered electrolysis [13].

Recent studies have found that blue hydrogen emits almost as much carbon as grey hydrogen with limited efficiency of carbon capture and unavoidable CH4 (3.5%), which is 86 times the global warming potential of CO2. Thus, water electrolysis is the most established method for carbon-free hydrogen production. The cost of green hydrogen in recent times has been several times more than that of grey hydrogen (1–2 USD/kg); grey hydrogen is less costly than blue hydrogen as blue hydrogen incurs additional costs due to carbon capture and utilization (CCU) processes. As a result, technological advancements and economies of scale can aid in lowering the cost of green hydrogen [12,14,15,16,17].

Types of Electrolysis Technologies

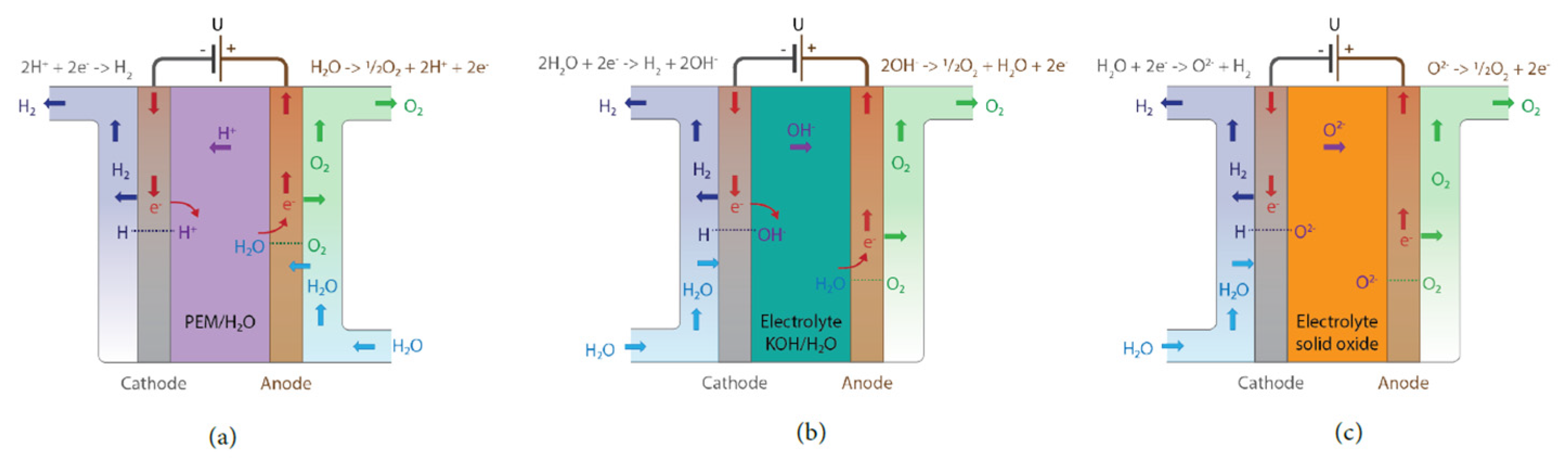

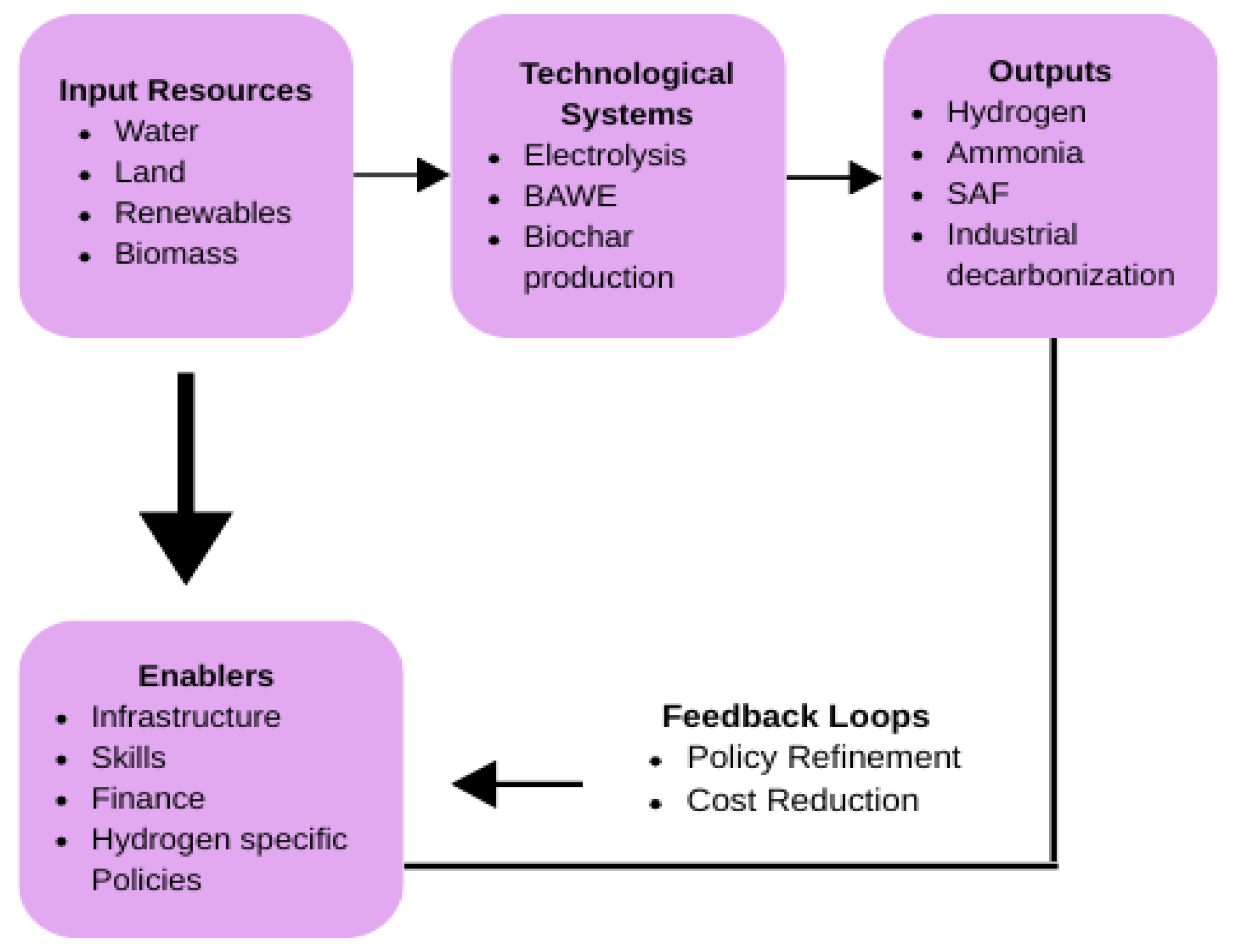

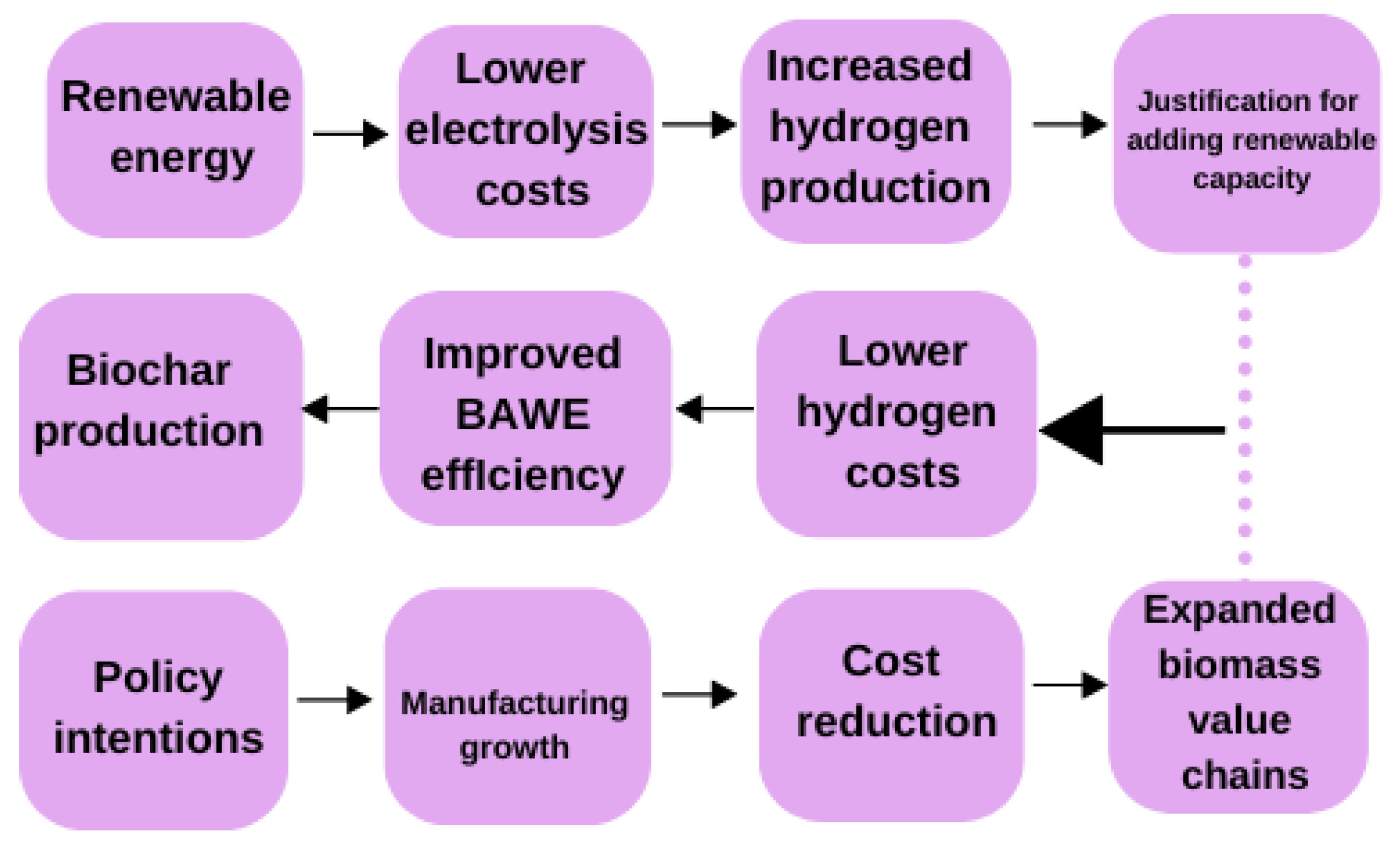

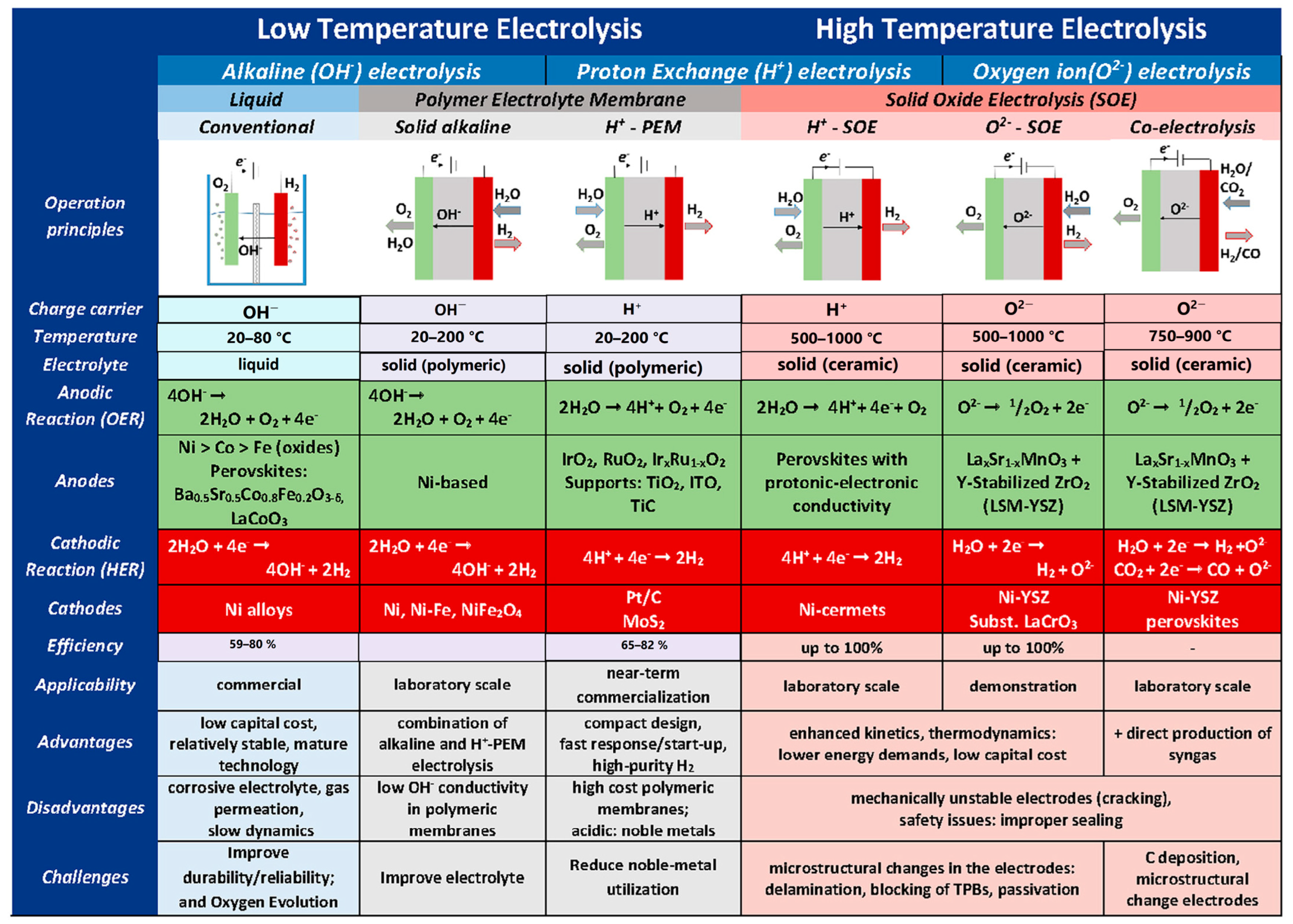

Water electrolyzers are broadly classified into alkaline electrolyzers, polymer electrolyte membrane (PEM) electrolyzers, and solid oxide electrolyzers (SOE). They are distinguished by their electrolyte composition, ionic conductivity mechanisms, and operating temperatures. In all systems, hydrogen forms at the cathode and oxygen at the anode as shown in Figure 1, but the transport of charge and the operational characteristics differ significantly across the configurations as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Working principles of (a) Polymer Electrolyte Membrane) (b) Alkaline and (c) Solid oxide electrolyzer cells [18].

Alkaline electrolyzers have been a mature technology since 1939 and typically use non-noble metals (Ni/Ni alloys), thus offering long-term stability. Nevertheless, they experience gas crossovers and consequently lower product purity, which results in reduced current densities and high series resistance. They also operate effectively only within a limited partial load range, generally above 40% load, and at low O2 production rates the associated gas crossover can create explosive hydrogen–oxygen mixtures. Proton exchange membrane (PEM) electrolyzers, also referred to as polymer electrolyte membrane systems, cannot easily operate at very high pressures or in highly corrosive electrolytes. They represent the current state of the art and prioritize water electrolysis efficiency, primarily because they can deliver high current densities, high voltage efficiency, and low ohmic losses due to their highly conductive membranes. In addition, they have a wide partial load operating range, can function down to about 10% load, and feature a fast dynamic response along with a compact system design. Unfortunately, they are limited by the high cost of system components, the reliance on scarce catalytic materials, and the need for an acidic electrolyte [19,20,21,22].

Anion exchange membrane electrolyzers, which combine the complementary advantages and key characteristics of both alkaline and PEM electrolyzers, have strong potential for application in green hydrogen production. Although this is the case, their infancy-stage, low technology readiness level impedes their rapid development and long-term durability, which is not yet established. The SOE cells have a solid oxide electrolyte that conducts oxygen ions. They are durable in elevated temperature operation of around 800 °C with high-efficiency water electrolysis, low minimum load of 3% and non-noble catalysts. Interestingly, their high temperature operation results in long start-up times, ceramic embrittlement, low durability and high energy requirements as well as infancy lab scale, thus low technology readiness level (TRL) [20,21,22].

South Africa’s renewable energy endowment positions the country to expand hydrogen production using these technologies, but widespread deployment will depend on lowering electrolyzer costs, improving system durability, and aligning technology development with policy support. While electrolysis remains the most technologically mature pathway for low-carbon hydrogen, biomass-derived pathways introduce complementary benefits, particularly through the co-production of biochar. Continued research, development, and innovation in both electrolyzer design and biomass-assisted hydrogen production are essential for building an efficient, competitive, and inclusive clean hydrogen economy.

Figure 2.

Key operating parameters for Polymer Electrolyte Membrane, Alkaline and Solid oxide electrolyzer cells [23].

Figure 2.

Key operating parameters for Polymer Electrolyte Membrane, Alkaline and Solid oxide electrolyzer cells [23].

2.2. The Role of Biomass in Advancing Decarbonization

Biomass derived from plants, animals, and microorganisms remains a central component of global and regional decarbonization strategies. Across the African continent, it has historically served as a primary energy source due to its availability and adaptability in rural and urban contexts. Biomass encompasses agricultural residues, forestry by-products, organic fractions of municipal waste, and purpose-grown energy crops, thus making it a versatile and dispatchable energy resource. Its compatibility with existing power generation infrastructure positions it as a strategic complement to variable renewable energy sources, particularly in emerging hydrogen economies where firm, low-carbon feedstocks will be increasingly important [24]. However, large-scale biomass deployment faces constraints, including feedstock aggregation challenges and the high cost associated with transporting biomass to centralized processing facilities.

With its high carbon content and wide resource base, biomass provides a sustainable platform for producing bio-based fuels, chemicals, and advanced materials. Pyrolysis generates three main products: bio-oil, syngas, and biochar. Among these, biochar has gained growing attention for both its carbon-sequestration potential and its applicability in catalytic and electrochemical processes. Patterns in the literature increasingly emphasize that biomass will contribute to decarbonization, not only through energy generation but also through its integration into circular systems, where biomass residues are transformed into value-added materials [25]. As energy systems transition toward low-carbon pathways, bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) has emerged as a key strategy for achieving net-negative emissions. Biochar production is integral to this approach because it stabilizes carbon and enables the long-term removal of atmospheric CO2. Beyond its role in carbon management, biochar offers additional advantages within the green hydrogen value chain. Its tunable surface chemistry and structural characteristics allow it to function as a catalyst or catalyst support, thus reducing reliance on conventional materials and increasing the opportunities for waste valorization [26]. These dual benefits, environmental and functional, contribute to growing interest in integrating biomass-derived products into hydrogen production systems.

Realizing the full potential of biomass and biochar requires supportive policy and regulatory frameworks that address feedstock supply, land-use considerations, and incentives for low-carbon innovation [24,27]. The following section examines biochar in greater detail, with particular focus on its properties, production pathways, and relevance to green hydrogen technologies and production.

2.2.1. Biochar

Biochar is a carbon source acquired through pyrolysis, typically via varying operating temperatures for varying maximum yields, as shown in Table 1, in comparison to other by-products. It can be used in a variety of applications, including carbon-based support materials in electrocatalysts for fuel cells. It is a cheap and readily available material that can be produced from different feedstocks, including invasive plant species, agricultural residues, and forestry waste, amongst others. Moreover, due to its high surface area, porosity, and electrical conductivity, which are detailed by Chia et al. (2015) [28], it can also serve as a support nanomaterial for catalysts that facilitate electrochemical reactions. It has been proven to improve the stability and durability of these catalysts, resulting in more efficient and longer-lasting fuel cells. However, its properties may differ depending on the feedstock and manufacturing process used [29].

Table 1.

Typical pyrolysis temperatures and their resulting product yield. Data source: [30].

In catalytic applications, biochar competes with alternative support materials such as graphene, silica, and activated carbon. Graphene is often highlighted for its exceptionally high surface area, electron mobility, and mechanical strength. Its uniform lattice structure improves adsorption and catalytic performance. However, the literature consistently identifies barriers related to graphene’s energy-intensive synthesis methods, reliance on limited precursor materials, and high production costs, which restrict large-scale deployment [31]. Additionally, while other support materials such as silica exhibit higher surface area than biochar, biochar’s lower cost, renewable origin, and straightforward functionalization offer compelling advantages for electrochemical applications, particularly in water electrolysis and fuel cell systems [29,32].

Biochar’s high energy content and adjustable physicochemical properties such as surface functional groups, pore structure, and thermal stability make it an effective catalyst support and energy carrier. These properties are strongly dependent on the original feedstock and pyrolysis conditions. Biochar generally exhibits higher heating values than raw biomass feedstocks, enabling its use in combustion and gasification processes for power and heat generation. In addition, its capacity to store stable carbon positions biochar as a critical component in BECCS systems, with growing evidence that it can significantly contribute to long-term carbon mitigation [33,34].

Although biochar has been widely explored for soil amendments, environmental remediation, and energy generation, fewer comprehensive assessments address its catalytic and electrocatalytic functionalities. Emerging studies demonstrate its application in fuel cells, energy storage devices, and as activated carbon in gas treatment system [29].

2.2.2. Biochar Applications

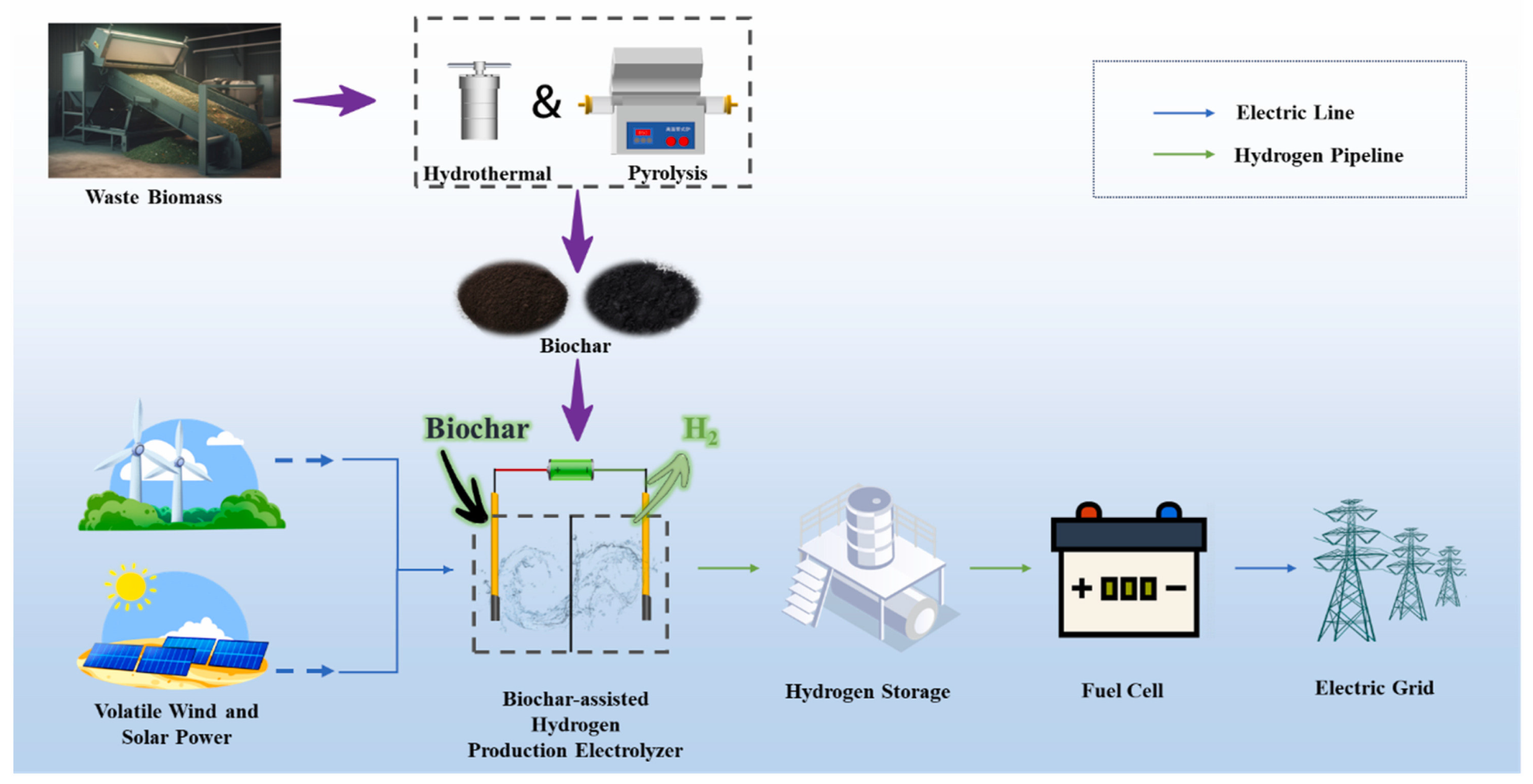

Biochar has emerged as a promising support material for catalysts in hydrogen fuel cells, as shown in Figure 3. This is due to its availability, low production cost, and adaptability to a wide range of biomass feedstocks, including invasive alien vegetation. Its porous structure provides a large specific surface area that enhances catalyst dispersion and increases the number of active sites for electrochemical reactions, thereby improving overall fuel cell efficiency [35].

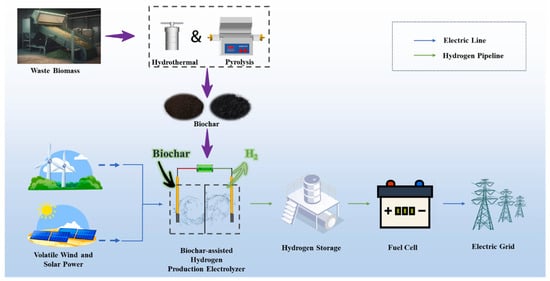

Figure 3.

Process Diagram of Biochar-Enhanced Water Electrolysis for Industrial Green Hydrogen Generation [35].

Despite these advantages, several challenges influence biochar’s suitability as a catalyst support. Variability in feedstock composition and pyrolysis conditions can lead to significant differences in structural properties such as porosity, conductivity, and functional group distribution. These variations affect catalytic performance and create uncertainty regarding reproducibility across production batches. Furthermore, the long-term electrochemical durability of biochar remains insufficiently characterized, and understanding degradation mechanisms under operational conditions is an important area for future research [36].

In fuel cell systems, biochar can enhance catalyst performance through its high porosity and electrical conductivity, which facilitate efficient electron transfer and improve mass transport. Studies demonstrate that biochar-supported catalysts, including those based on platinum, palladium, nickel, and other transition metals, exhibit improved stability and durability relative to unsupported catalysts. These findings highlight a broader trend in the literature; biomass-derived carbon materials are increasingly being explored as cost-effective alternatives to conventional catalyst supports such as carbon black or synthetic nanomaterials [37,38]. The capacity to functionalize biochar surfaces further expands its applicability across fuel cells, electrolysis systems, adsorption processes, and energy storage devices.

In general, biochar’s role in renewable energy systems extends beyond its immediate catalytic applications. Its carbon-rich nature supports climate mitigation through long-term carbon sequestration, while its versatility enables integration into energy conversion, material synthesis, and environmental remediation. Research efforts are increasingly focused on optimizing production methods, improving material stability, and developing new functional modifications to expand biochar’s performance in energy technologies. With sustained investment in research and development, biochar can contribute meaningfully to a low-carbon energy transition. For countries such as South Africa, which is the highest carbon emitter on the continent, advancing biochar-based green hydrogen technologies could support both emissions reduction and localized economic development within the broader renewable energy landscape.

2.2.3. Biochar Applications in Hydrogen Production

Biochar in Anaerobic Digestion to Produce Hydrogen

Anaerobic digestion (AD) is a well-established biological process in which microorganisms decompose organic matter to produce biogas consisting primarily of methane (CH4) and carbon dioxide (CO2). Although hydrogen can be generated during specific stages of AD, its concentration in conventional biogas streams is typically very low, thus limiting its direct contribution to hydrogen-based decarbonization pathways [39].

The literature consistently indicates that incorporating biochar into AD can increase hydrogen yields and improve overall system performance [40]. However, important uncertainties remain regarding optimal operating conditions. Key variables including biochar dosage, pyrolysis temperature, particle size, feedstock characteristics, and reactor temperature and pressure, significantly influence outcomes and are not yet standardized across studies. These variations contribute to inconsistent results and highlight the need for systematic investigations to define optimal biochar properties and process configurations. Overall, biochar-assisted anaerobic digestion represents a promising pathway for augmenting biohydrogen production while simultaneously improving process efficiency and digestate quality. Continued research is required to address technical variabilities, assess long-term system stability, and evaluate the scalability of this approach as part of an integrated low-carbon hydrogen production strategy.

Biochar as a Catalyst for Steam Methane Reforming to Produce Hydrogen

Biochar has gained increasing attention as a potential catalytic material for steam methane reforming (SMR), one of the most widely used industrial processes for hydrogen production. Conventional SMR relies on high temperatures (typically 800–950 °C) and produces substantial carbon dioxide emissions, which pose environmental challenges for its continued large-scale use. Under optimized operating conditions, syngas yields approaching 93.2% have been reported, thus indicating strong catalytic activity and meaningful potential for energy savings and reduced emissions [41]. Importantly, SMR using biochar not only generates hydrogen-rich syngas but also converts two major greenhouse gases, methane (CH4) and carbon dioxide (CO2), into useful products, thereby contributing to emissions reduction through resource utilization.

Recent studies have further examined the structural resilience of biochar catalysts under high-temperature conditions. At approximately 850 °C, coke deposited within the mesoporous and macroporous networks of various biochars was effectively gasified, thus enabling sustained catalytic performance over extended operation. These findings suggest that meso- and macro-porous biochars possess the durability necessary for practical reforming applications, particularly in processes where tar cracking and carbon deposition often limit catalyst lifetimes [42].

Collectively, the literature indicates that biochar offers a viable pathway for enhancing SMR efficiency while lowering operational temperatures and reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Nevertheless, several uncertainties remain. Optimal biochar characteristics such as feedstock selection, pyrolysis temperature, pore architecture, and surface modification are not yet standardized, and long-term performance under industrial SMR conditions requires further investigation. Addressing these gaps will be critical to determining the extent to which biochar can be integrated into large-scale hydrogen production as part of a broader low-carbon energy transition.

Biochar as Catalysts for Water Splitting to Produce Hydrogen

Water splitting is a key pathway for producing clean hydrogen, and it relies on catalytic materials to drive the hydrogen and oxygen evolution reactions. Conventional catalysts such as platinum, iridium, and nickel provide high performance but are limited by high cost, scarcity, and supply-chain constraints. These challenges have motivated research into alternative catalytic materials that are affordable, renewable, and scalable. Biochar has emerged as a promising candidate due to its large surface area, porous architecture, and ability to facilitate efficient charge and mass transfer during catalytic reactions [36,43].

Studies demonstrate that biochars derived from different feedstocks exhibit distinct structural and electronic characteristics that influence their photocatalytic activity. For example, biochar produced from sewage sludge, softwood pellets, and rice husk at 700 °C displays different thermal degradation profiles and surface functionalities, which in turn affect hydrogen generation efficiency. Biochars derived from sugarcane bagasse have shown strong catalytic activity for both the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) and oxygen evolution reaction (OER), thereby highlighting the role of feedstock chemistry in determining catalytic performance [44].

Quantitative assessments further illustrate biochar’s catalytic potential. Norouzi et al. (2019) [45] reported hydrogen production rates of 4162 μmol/g from biochar produced at 700 °C, thus attributing this high activity to the following synergistic properties: extensive surface area, high porosity, reduced band-gap energy (2.27 eV), improved photocurrent density, and low charge-transfer resistance. Similarly, biochar derived from sugarcane bagasse demonstrated HER and OER overpotentials of 154 mV and 362 mV at 10 mA cm−2, respectively, which the authors linked to nitrogen- and sulfur-containing functional groups that enhance catalytic processes.

In comparison, traditional catalyst supports such as zeolites, activated carbon, and the two-dimensional nanomaterial graphene are extensively employed because of their intrinsically high surface areas, adjustable pore architectures, and robust morphological characteristics. Graphene is of significant technological interest due to its very high specific surface area of about 2600 m2·g−1, which far exceeds that of conventional graphite powder (~10 m2·g−1) and carbon black (~900 m2·g−1). Furthermore, graphene’s large interlayer spacing, outstanding charge carrier mobility, structural flexibility, and excellent mechanical strength together confer a high electrical conductivity (5–6.4 × 106 S·m−1). Its uniform hexagonal lattice structure and ease of surface functionalization make graphene highly attractive for diverse applications, ranging from next-generation energy storage systems to catalysis, where its tunable surface properties establish it as a superior carbon-based support. However, commonly used precursor materials and synthesis methods for graphene often require substantial energy inputs and rely on scarce resources, thereby resulting in high production costs and raising concerns about long-term sustainability [31,46,47,48].

These findings reflect a broader trend; biochar’s catalytic performance is strongly governed by its feedstock origin, pyrolysis conditions, and chemical functionalities. Its tunability, low cost, and carbon-negative production pathway position biochar as a viable material for advancing water-splitting technologies. However, the literature also reveals persistent uncertainties related to long-term stability, catalyst degradation, and performance under industrial-relevant conditions [49]. Moreover, scaling biochar-enabled water electrolysis requires a deeper understanding of region-specific biomass characteristics and techno-economic feasibility. For South Africa, these knowledge gaps are particularly relevant given the country’s biomass resources, hydrogen ambitions, and carbon mitigation needs. Critical gaps include the following:

- (i)

- Limited studies on biochar catalysts derived from South African feedstocks, such as agricultural residues, forestry waste, and invasive species, despite their abundance and potential value.

- (ii)

- A lack of techno-economic, life cycle, and carbon-accounting analyses examining biochar-assisted electrolysis under South African energy cost structures and policy conditions.

- (iii)

- Minimal integrated investigations that evaluate both hydrogen production and carbon sequestration, despite the dual benefits associated with biochar reuse.

- (iv)

- Insufficient exploration of hybrid or functionalized biochar catalysts, particularly systems tailored to local mineral compositions and critical materials availability.

Addressing these research gaps is essential for advancing biochar-assisted water electrolysis and realizing its potential contribution to South Africa’s emerging green hydrogen sector.

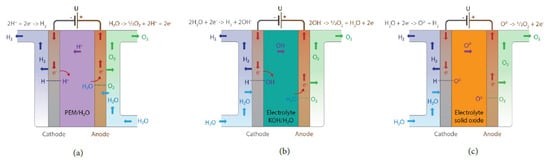

2.2.4. Recent Advances in Biochar Integration for Green Hydrogen Production

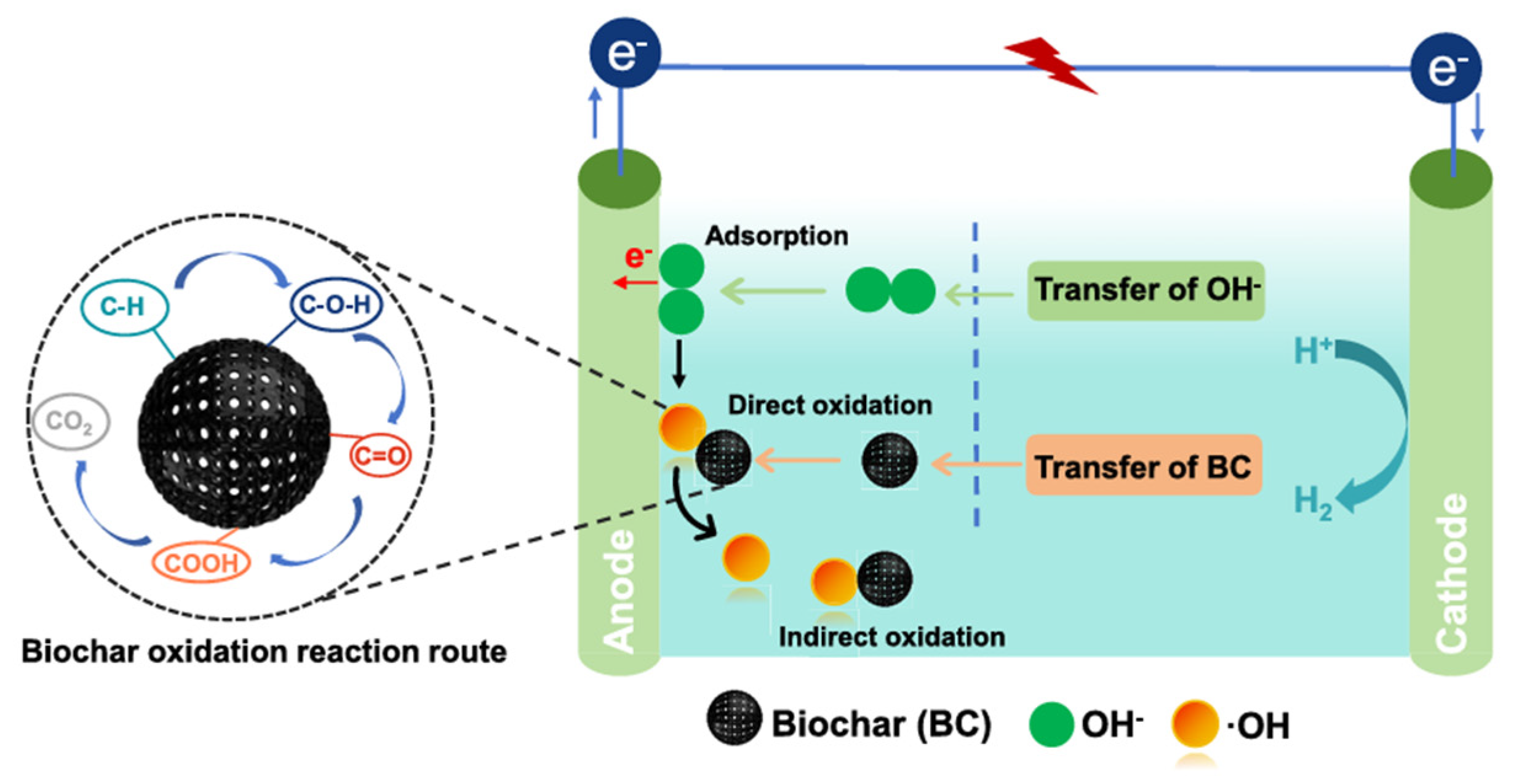

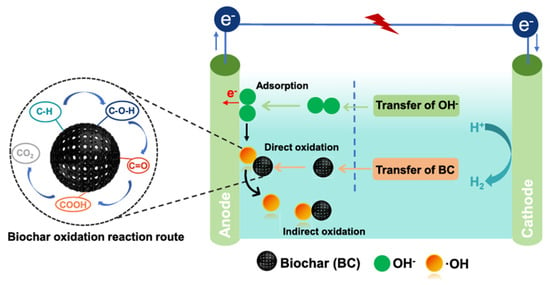

Recent research has increasingly focused on biochar-assisted water electrolysis (BAWE) as a promising, energy-efficient alternative to conventional electrolysis. Key advancements reported by Sun et al. (2025) [50] involve replacing the OER, a kinetically slow and energy-intensive half-reaction, with the more thermodynamically favourable biochar oxidation reaction (BOR), as illustrated in Figure 4. Substituting OER with BOR substantially reduces the overall energy demand of electrolysis while simultaneously converting biochar into value-enhanced products.

Figure 4.

The illustration of oxygen evolution reaction (OER) with biochar oxidation reaction (BOR) [6].

Emerging studies reveal that simple pre-treatment steps can significantly influence the electrochemical performance of biochar in BAWE systems. Moderate water washing has been shown to markedly improve the activity of lignocellulosic biochars. Water-washed biochar has achieved Faradaic efficiencies of up to 99.5% for hydrogen production at a current density of 50 mA cm−2, thereby demonstrating substantial gains over untreated materials. These improvements are attributed to the removal of inorganic impurities, increased accessibility of active surface sites, and enhanced ionic transport pathways [50].

Beyond hydrogen generation, the electrooxidized biochar produced during BAWE exhibits improved environmental functionality. Studies report increased Cr(VI) removal capacity after electrooxidation, driven by the formation of oxygen-containing functional groups on the biochar surface. This dual benefit—efficient hydrogen production coupled with the generation of environmentally active carbon materials—reflects a growing trend in the literature toward multifunctional, integrated hydrogen production systems [50].

Another study by Hu et al. (2024) [35] further demonstrates the potential of BAWE by substituting the oxygen evolution reaction with the biochar oxidation reaction. This substitution markedly lowers the required cell potential and increases current density, with performance improvements amplified through the use of Fe2+ redox mediators. Hu et al. show that pretreatment strategies such as pickling and KOH activation significantly enhance biochar morphology by increasing surface area, enriching micropores, and introducing oxygen-containing functional groups that facilitate oxidation kinetics. Notably, pickled hydrothermal biochar achieved an oxidation current density of 180 mA cm−2 at only 1.2 V, thus indicating substantial gains in electrochemical efficiency. These findings reinforce the view that biochar provides a practical means of coupling biomass waste utilization with lower-energy hydrogen production.

Additional work by Ying et al. (2024) [51] highlights the decisive role of biochar physicochemical properties in governing BAWE performance. Functional group abundance, hydrophilicity, and electrical conductivity were shown to strongly influence biochar oxidation reactions, directly affecting hydrogen yield. Using biochar derived from cellulose-lignin pyrolysis, the study identified optimized materials such as MBC-800 that exhibited superior BOR kinetics due to improved electron and mass transfer at the anode-electrolyte interface. Ying et al. further demonstrated that maintaining cell potential below 1.6 V (vs. RHE) promotes efficient biochar oxidation and high current densities, whereas higher potentials shift reaction dominance back to OER, thereby reducing system efficiency. These insights accentuate the importance of controlling electrode potential to maximize BAWE performance.

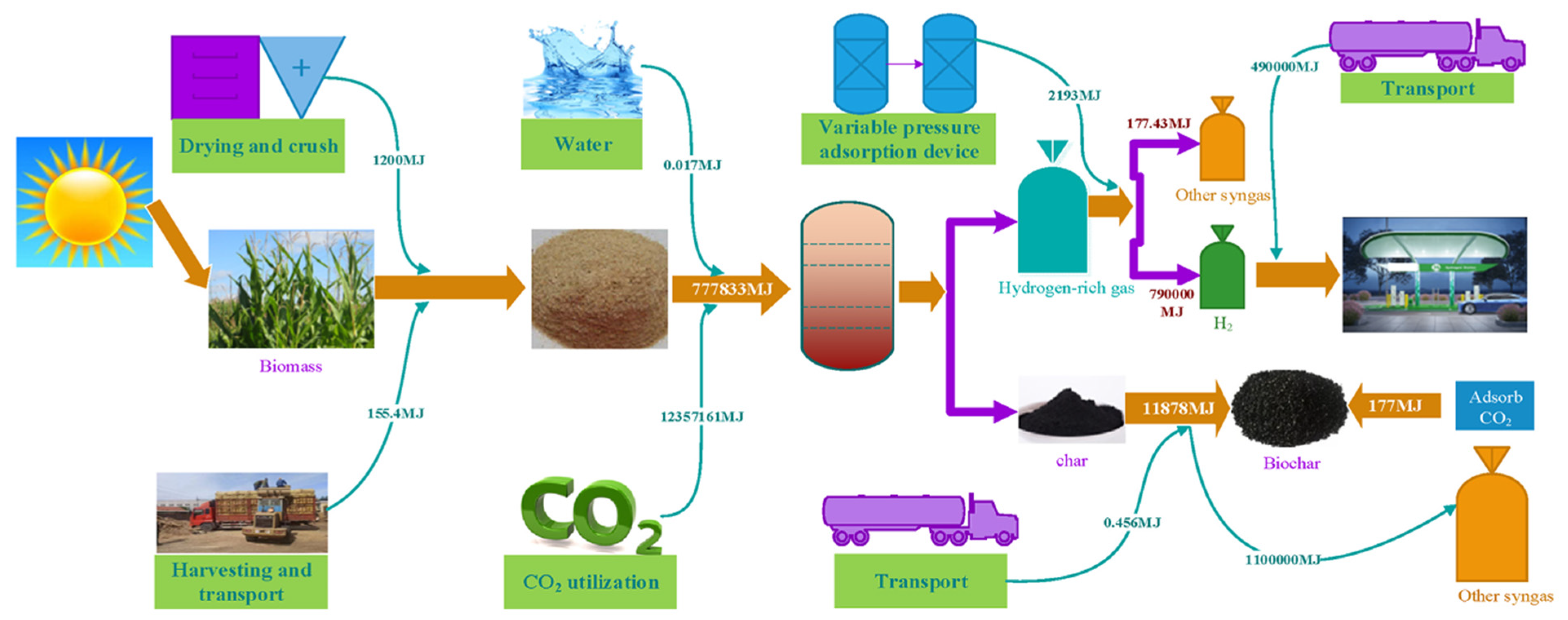

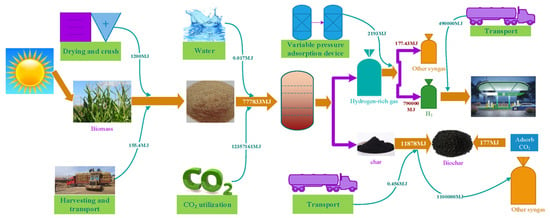

Studies have proven that BAWE is not usually energy-intensive, thus making it a practical and competitive hydrogen production option. Figure 5 illustrates the energy consumption distribution across the entire life cycle. For a full component-oriented pyrolysis process using 5.55 t of corn straw, the total life cycle energy consumption for producing hydrogen gas and biochar is 1.31 × 107 MJ, corresponding to a hydrogen production capacity of 0.55 × 103 kg h−1. In this system, the key contributions from hydrogen transportation and corn straw collection amount to 155 MJ for producing 0.55 × 103 kg of hydrogen. Consequently, the energy required for the biomass pretreatment step is 1.26 × 107 MJ for hydrogen production. Gas purification and transportation together consume about 4.92 × 105 MJ, while the expected energy output is 7.94 × 104 MJ. This indicates that the overall biomass conversion process corresponds to 0.46 kJ, yielding an energy output of 1.19 × 104 MJ. The total system energy for valorizing corn straw via full component-oriented pyrolysis is 1.31 × 107 MJ, with an additional 9.13 × 104 MJ associated with hydrogen-rich gas. On an annual basis, the system can generate 40,000 t of biochar, 26,000 t of hydrogen-rich gas, and 3991.3 t of hydrogen. In comparison with other hydrogen production routes, the life cycle energy consumption and total energy output of 9.56 × 1010 MJ and 6.58 × 108 MJ, respectively, demonstrate that this biomass-to-hydrogen conversion process is relatively easy to operate and not energy intensive [52].

Figure 5.

Energy Consumption Distribution across the entire Life Cycle [52].

Overall, the demonstrated energy performance of biochar-assisted water electrolysis highlights its strong potential relevance for South Africa’s energy transition. The relatively low life-cycle energy intensity, together with the ability to convert abundant agricultural residues such as corn straw into clean hydrogen and value-added co-products, positions BAWE as a practical and competitive pathway for expanding green hydrogen production while addressing persistent national electricity constraints. In addition, the co-production of biochar offers environmental benefits while aligning closely with South Africa’s climate commitments, circular economy objectives, and Just Energy Transition framework. Collectively, recent advances in BAWE illustrate a compelling opportunity to diversify South Africa’s clean energy mix while strengthening locally anchored hydrogen value chains. However, realizing the full potential of these systems will require deliberate scale-up efforts, particularly through increased investment in research, development, and innovation to improve system durability, optimize biochar synthesis routes, and enable pilot- and industrial-scale demonstrations. Equally important is the establishment of coherent policy and regulatory frameworks that support efficient and competitive deployment. Coordinated strategies across the energy, agriculture, and waste sectors will therefore be essential for commercializing advanced BAWE systems, accelerating green hydrogen development, and maximizing the environmental and socio-economic benefits of integrated biochar-hydrogen technologies within South Africa’s energy transition.

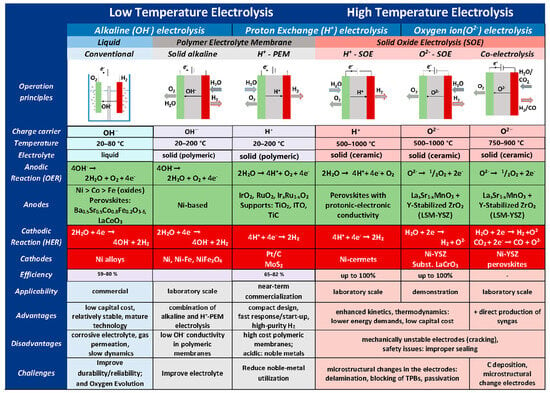

3. South Africa’s Renewable Energy Landscape

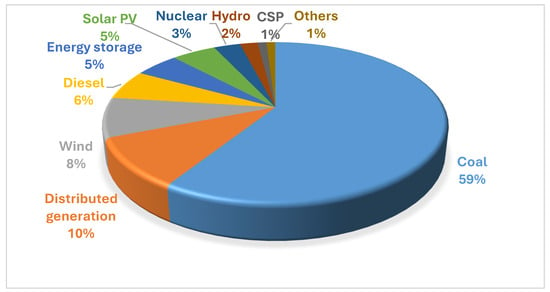

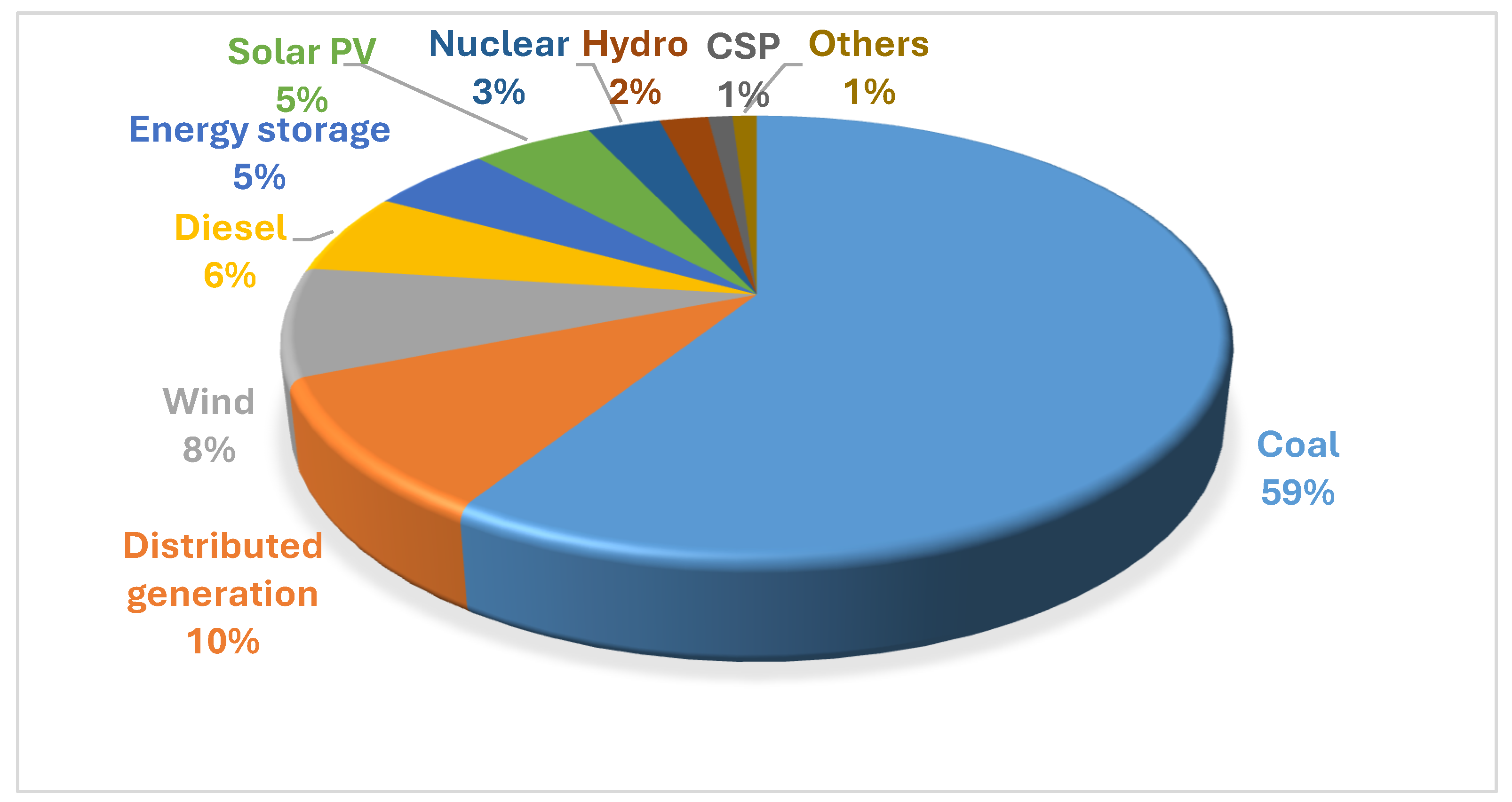

As of 2021, South Africa remained the largest producer and consumer of energy on the African continent, with a total installed electricity generation capacity of approximately 53.7 GW, of which 8.8 GW was derived from renewable energy sources [53]. The national energy mix continues to be dominated by coal, as shown in Figure 6, reflecting decades of reliance on coal-fired baseload power. Despite this legacy structure, South Africa aims to become one of the leading investors in renewable energy technologies in Africa.

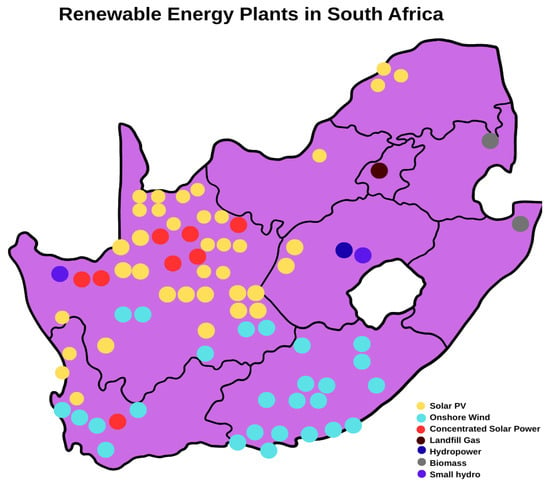

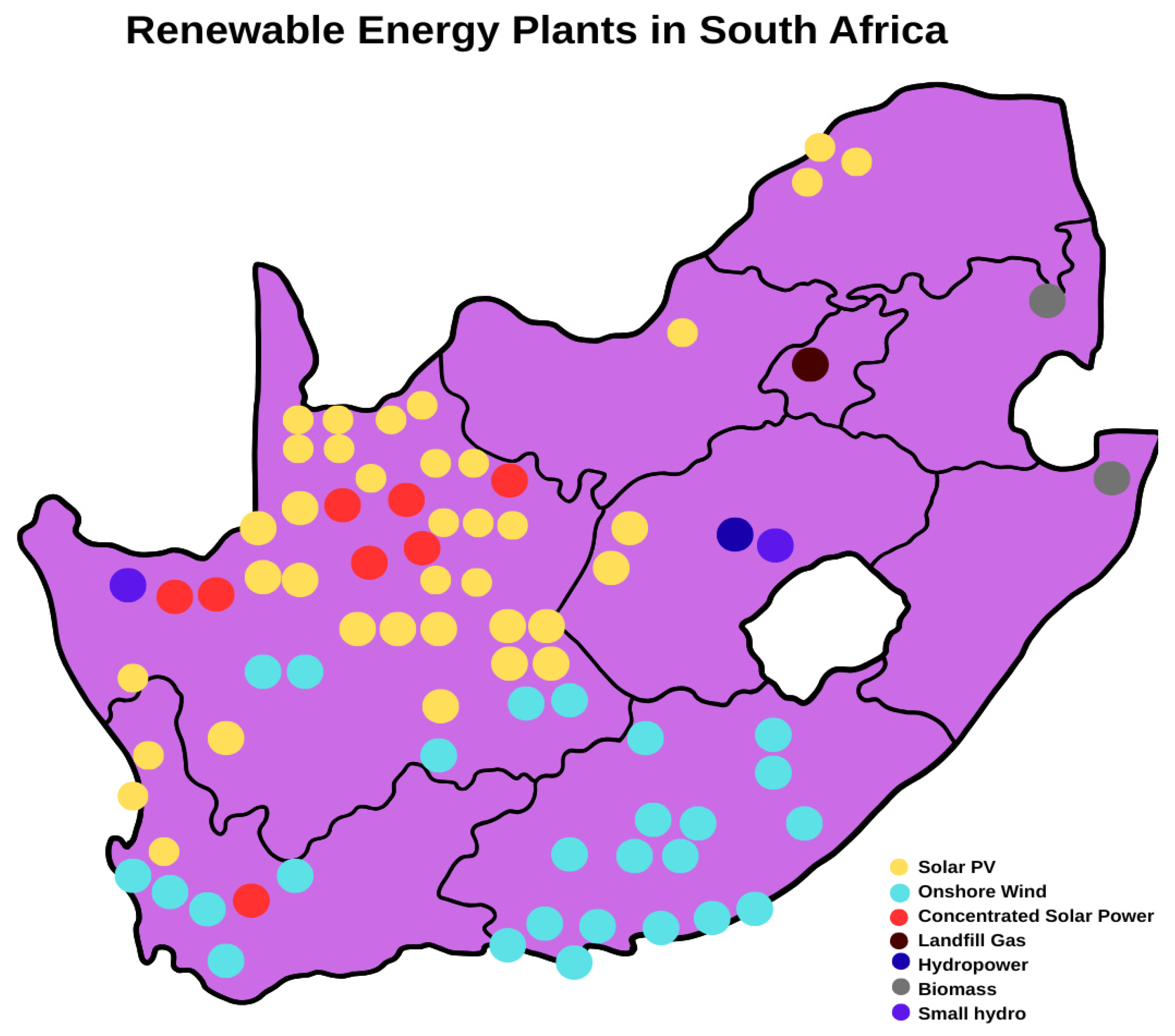

The country’s geographical characteristics provide strong potential for multiple renewable energy options, including solar, wind, and biomass. High solar radiation levels averaging 5.55 kWh m−2 per day, combined with favourable wind resources, with typical speeds around 6 m s−1 at 100 m hub height, support the technical viability of large-scale renewable deployment [54,55]. These conditions have stimulated rapid market growth, particularly for solar PV installations and solar water heating systems, some of which are now manufactured domestically. In addition, close to 30,000 small-scale wind turbines have been deployed in rural, arid, and agricultural settings, mainly for water pumping and household use. However, the literature shows that commercial-scale wind energy deployment remains limited relative to the country’s potential, thus indicating opportunities for further expansion [54]. Major progress in renewable energy development has been driven by the Renewable Energy Independent Power Producers Procurement Programme (REIPPPP). This programme, initiated by the South African government, aims to secure renewable electricity from independent power producers (IPPs) through competitive auctions and private-sector investment. REIPPPP has facilitated the deployment of diverse technologies, including onshore wind, solar PV, concentrated solar power, biomass, landfill gas, and small hydropower as illustrated in Figure 7 [56]. The programme is widely recognized as one of the most successful renewable energy procurement mechanisms, thus contributing to increased investor confidence and accelerating South Africa’s transition toward a more diversified and lower-carbon energy system.

Figure 6.

South Africa’s installed capacity in 2025. Data source: [57].

Figure 6.

South Africa’s installed capacity in 2025. Data source: [57].

Figure 7.

Illustration of the distribution of renewable energy power plants from the REIPPP in South Africa. Data source: [53].

Figure 7.

Illustration of the distribution of renewable energy power plants from the REIPPP in South Africa. Data source: [53].

3.1. Renewable Energy Independent Power Producer Programme (REIPPP)

Established in 2011, the REIPPPP has become a central mechanism for stimulating private-sector investment in South Africa’s renewable energy sector. The programme was designed to diversify the national energy mix by procuring electricity from IPPs across a range of technologies, thereby reducing the country’s dependence on fossil fuel-based generation. Its impact has been substantial: renewable energy capacity increased from 1501 MW in 2013 to 7336 MW by the end of 2024 including contributions from diesel-fueled emergency generators. By 2020, renewable energy accounted for approximately 10% of South Africa’s total electricity supply [58]. South Africa’s long-term ambitions further highlight the importance of REIPPPP. Government plans indicate targets of 17,711 MW of installed wind capacity and 8300 MW of solar capacity by 2030, thereby contributing to an anticipated 37.3 GW of total renewable energy capacity [53]. Achieving these goals requires consistent procurement cycles, stable incentives, and strong private-sector confidence.

Despite early momentum, recent developments have introduced uncertainty into the market. By the end of 2024, Bid Window 7 was the most recent procurement round to be released; however, no new bid windows had been announced by late 2025. Analysts note that such irregular procurement creates concentrated bursts of demand for components and services, compressing supply timelines and creating operational pressures for manufacturers and service providers. These fluctuations complicate production planning, inventory management, and investment decisions across the renewables value chain. As a result, project developers often struggle to meet local content requirements within prescribed timelines, leading many to request exemptions that allow for the importation of key components [59]. The literature points to a clear conclusion: a predictable, sustained, and sufficiently large procurement pipeline is essential for anchoring local manufacturing, ensuring supplier readiness, and securing long-term private investment. Strengthening and expanding the REIPPPP with improved policy certainty, regular procurement cycles, and targeted incentives will be critical for South Africa to meet its 2050 decarbonization commitments and to position the country as a competitive renewable energy hub.

3.2. South Africa’s Green Hydrogen Landscape

Global interest in green hydrogen and its derivative products such as ammonia and synthetic aviation fuels continue to rise as countries pursue decarbonization commitments and long-term climate targets. Several major importers, including Japan and the European Union, are actively seeking strategic partnerships and long-term supply agreements, often at premium prices, to stimulate production capacity in exporting countries and secure future supply [60]. South Africa, endowed with vast renewable energy resources, large land availability, and established industrial capabilities, is well positioned to produce green hydrogen at competitive costs for both domestic consumption and export markets.

Green hydrogen also holds strategic relevance within South Africa’s Just Energy Transition (JET). The country continues to experience high unemployment, approximately 32.9% in the second quarter of 2024 [61], while the fossil fuel sector currently provides significant employment, particularly in rural and traditionally underdeveloped regions. A shift away from coal must therefore be accompanied by alternative economic opportunities that support affected communities. Studies indicate that green hydrogen development could play an important role in this transition. Dyantyi-Gwanya et al. (2025) [62] estimate that 1 GWe of installed green hydrogen capacity could generate up to 700 local jobs across the power-to-hydrogen value chain. Complementary evidence from Irarrazaval et al. (2026) [63] emphasizes the importance of evaluating employment effects across the entire hydrogen value chain, noting that hydrogen projects generate construction-phase employment, long-term operational jobs, and roles associated with eventual decommissioning. National planning documents reinforce this potential. According to South Africa’s Green Hydrogen Commercialization Strategy 2022, the country aims to produce approximately 7 Mt of green hydrogen annually by 2050. If achieved, the green hydrogen industry could generate up to R75 billion (approximately 6.5% of GDP), create as many as 370,000 jobs, and contribute an estimated R24 billion in annual tax revenues. International experience also supports these projections. A case study of five green hydrogen projects in Chile’s Magallanes region found that the developments collectively created 23,076 jobs, thus highlighting the substantial labour requirements embedded across hydrogen production, processing, logistics, and associated infrastructure [63,64]. Taken together, the literature indicates that South Africa’s green hydrogen landscape is shaped by the following three reinforcing dynamics: strong international demand signals, the country’s competitive resource base, and the socio-economic imperative to drive an equitable energy transition. Realizing this potential will depend on coordinated investment, regulatory clarity, local skills development, and integrated planning across energy, industrial, and regional development policy domains.

The green hydrogen economy also holds significant potential to stimulate domestic industrial development and generate foreign revenue through export-oriented value chains [55,65]. However, several studies caution that this potential is accompanied by considerable risks. Cloete et al. (2026) [65] highlight concerns that unrealistic or poorly timed localization requirements could create supply bottlenecks, increase project lead times, and raise the cost of renewable electricity inputs. These risks are amplified by South Africa’s current structural constraints, including limited local manufacturing capacity for renewable energy components, restricted access to financial capital, shortages in technical skills, water availability challenges, and persistent energy security issues, as emphasized by Olifant et al. (2025) [55].

At present, South Africa produces grey hydrogen, accounting for nearly 2% of global hydrogen output, primarily through Sasol’s Fischer-Tropsch (FT) coal-to-liquids process. In contrast, national projections envision South Africa contributing approximately 4% of global green hydrogen production by 2025, with an estimated split of 2% for domestic use and the remaining share destined for export markets. Exported green hydrogen and its derivatives are expected to be priced in the range of USD 3–6 per kilogram, depending on production scale and renewable energy costs [62].

To advance national green hydrogen ambitions, South Africa has announced 24 green hydrogen and green ammonia projects, as catalogued by Olifant et al. (2025) [55]. Among these initiatives is the Green Hydrogen Valley, which integrates three provincial hubs—Limpopo, Gauteng, and KwaZulu-Natal—to form an industrial cluster intended to stimulate early market development. Other strategic locations include the Coega Special Economic Zone, where salt-processing operations already produce desalinated water as a by-product, and the Saldanha Bay Special Economic Zone, which is situated near high-quality solar and wind resources in the Northern Cape [62]. Alongside government-led initiatives, several private-sector projects signal growing early-stage activity within the following national hydrogen ecosystem:

- (i)

- In 2022, Anglo American commissioned the world’s first and largest hydrogen-powered mine haul truck, supplied by a 3.5 MW on-site green hydrogen plant [55].

- (ii)

- In October 2023, Sasol, Anglo American Platinum, and the BMW Group formed a consortium to support transport decarbonization through the establishment of a domestic green hydrogen mobility ecosystem. The partnership aims to pilot hydrogen fuel cell vehicles, with Sasol producing green hydrogen, Anglo American Platinum providing catalyst metals, and BMW supplying the vehicles [55].

- (iii)

- In February 2024, the consortium launched a pilot fleet of BMW iX5 Hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicles, positioning hydrogen mobility as a potential complement to battery-electric vehicles in South Africa’s transition to zero-emission transport [66].

Despite these developments, progress toward large-scale project implementation remains limited. Current activity largely reflects conceptual planning, early feasibility studies, and demonstration-scale deployments rather than mature investment decisions. As highlighted in the literature, the South African government continues to promote the sector through policy instruments and regulatory frameworks; however, persistent structural constraints such as financing gaps, infrastructure deficits, and policy uncertainty continue to slow advancement toward commercialization.

Meanwhile, several African peers, including Morocco, Namibia, and Egypt, are emerging as competitive green hydrogen producers. These countries benefit from high installed renewable energy capacities, targeted investment strategies, government support, and streamlined regulatory processes. This positions them as early movers in global export markets. As summarized in Table 2, their accelerated progress introduces increasing regional competition, thus highlighting the need for South Africa to strengthen implementation capacity and improve policy coherence to remain competitive.

Table 2.

Capacity of renewable deployed and green hydrogen ambitions.

3.3. The Challenges Facing South Africa’s Green Hydrogen Economy

Beyond renewable energy inputs such as solar and wind, the development of a viable green hydrogen economy depends on a range of additional resource enablers, including water, land, infrastructure, manufacturing capacity, financial investment, and effective policy implementation. As highlighted by Olifant et al. (2025) [55] and Tonelli et al. (2023) [71], gaps across these factors pose substantial constraints to the pace and scale of South Africa’s green hydrogen transition. While acknowledging these broader enablers, water remains a critical limiting resource for national green hydrogen production.

Water is fundamental to hydrogen production via electrolysis. Approximately 9–15 kg of water is required to produce 1 kg of hydrogen; however, when considering full life-cycle processes, the solar-to-hydrogen water footprint increases to an estimated 43 litres per kilogram of hydrogen [72]. This requirement is significant when positioned against South Africa’s broader water security context. The country faces a projected 17% water-demand gap equivalent to 2.7 billion m3 by 2030, which may increase to 3.8 billion m3 under climate change scenarios. South Africa receives less than half of the global average annual rainfall, and wet-day precipitation is expected to decline by an additional 15–45% [73]. Urban water use already accounts for roughly 3.5 billion m3 annually, second to agriculture at 8.4 billion m3, and substantially above industrial consumption at 1.5 billion m3. These dynamics illustrate that the national water system is running at or near capacity, leaving very limited room for expansion into additional water-intensive industries such as green hydrogen production.

Water scarcity has direct implications for equity. Many South African communities, particularly in rural areas, still lack consistent access to clean and reliable water supplies. Expanding green hydrogen infrastructure could therefore intensify competition between industrial and domestic water needs, with further risks to agricultural production. This positions water at the centre of South Africa’s water-energy-food nexus, thus highlighting the need for integrated planning approaches [55,74]. While the legacy fossil fuel sector has also contributed to water stress through extraction processes and large cooling water requirements, green hydrogen, if poorly governed, carries the risk of replicating similar pressures.

Several researchers propose seawater electrolysis as an alternative pathway; however, direct seawater electrolysis remains technologically immature, and desalination introduces additional energy consumption, cost, and environmental considerations. Nonetheless, South Africa has begun exploring desalination opportunities. The Coega Special Economic Zone already hosts salt-processing operations that discharge desalinated water as a by-product, thereby offering a potential foundation for co-located hydrogen production [62]. While promising, these initiatives require coordinated policy and regulatory measures to ensure that hydrogen production balances efficiency gains with water security, environmental protection, and social equity.

Beyond water, land availability and land-use governance are critical determinants of hydrogen infrastructure development. Securing land requires early engagement with communities and landowners, particularly in high-resource regions such as the Northern Cape, which spans approximately 285,000 km2. Strategic environmental assessments and socio-economic impact studies are essential to avoid conflicts related to biodiversity loss, tourism, agriculture, and conservation, as well as to prevent additional pressures on already fragile rural economies [75].

South Africa’s existing energy infrastructure remains predominantly designed for fossil fuels, necessitating new investments in hydrogen-compatible systems. The successful rollout of hydrogen production, storage, transmission, and end-use infrastructure will depend on coordinated planning involving government, state-owned enterprises, financiers, and local manufacturing sectors [65,75].

A range of additional enablers, including international partnerships, financial and supply chain capacity, and the development of a skilled workforce, are emphasized in the JET-IP as essential for scaling South Africa’s green hydrogen industry. However, persistent structural constraints limit progress. South Africa’s fiscal pressures, high sovereign risk, and the debt burdens of state-owned enterprises reduce the bankability of large-scale hydrogen projects by elevating the cost of capital. Even with access to concessional finance through the JET-IP, project deployment remains slow, and barriers to be highlighted include underdeveloped local value chains, workforce readiness and environmental approvals. These constraints highlight the need for targeted interventions across the entire green hydrogen value chain. Addressing them is essential not only for unlocking production and export opportunities but also for ensuring that green hydrogen contributes meaningfully to South Africa’s socio-economic priorities and supports the broader goals of a just energy transition.

3.4. Green Hydrogen Research, Development and Innovation in South Africa

Although large-scale green hydrogen deployment in South Africa has not yet materialized, the country remains active in advancing research, development, and innovation (RDI). A growing body of work across universities, universities of technology, science councils, and specialized research institutions reflect increasing national commitment to building foundational knowledge and technological readiness. Several initiatives focus on electrolyzer technologies, hydrogen storage, fuel cell systems, catalyst development, and feasibility assessments. Table 3 summarizes selected research programmes, their objectives, and key outputs, illustrating the breadth and early momentum of the national RDI landscape.

Despite South Africa’s strong agricultural base and substantial generation of biomass residues, the potential of these resources for BAWE remains largely unexplored. The country produces significant quantities of lignocellulosic residues from agro-industrial activities, particularly from the sugar industry, which generates approximately 8 million tonnes of sugarcane bagasse annually [76]. However, current research, development and innovation efforts in South Africa have largely focused on conventional electrolysis pathway, with minimal attention given to the valorization of biomass as functional materials within electrolysis systems.

Table 3.

Current Green Hydrogen Research Activities in South Africa. Summary of ongoing green hydrogen projects at South African universities, science councils, and research institutions, including their main objectives and associated research and innovation outputs.

Table 3.

Current Green Hydrogen Research Activities in South Africa. Summary of ongoing green hydrogen projects at South African universities, science councils, and research institutions, including their main objectives and associated research and innovation outputs.

| Research Name | Hosts | Research and Innovation Focus | Objectives | Research Outputs | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HySA Catalysis | Mintek and the University of Cape Town | Fuel cells and electrolyzer systems | To develop advanced fuel cell and fuel to hydrogen systems. | Publication | [77] |

| HySA Infrastructure | North-West University and the CSIR | Fuel cells and Storage/infrastructure | To develop hydrogen production systems and prototypes. | Publication, patents and trademarks. | [78] |

| CSIR hydrogen storage facility | CSIR | Renewable electricity and associated infrastructure, as well as hydrogen production. | To advance research in hydrogen production, storage, and energy systems and develop cost-effective, locally sourced hydrogen and battery technologies. | Publications and study programmes. | [79] |

| Hydrogen Energy Applications (HYENA) | University of Cape Town | Fuel cells and hydrogen production. | To develop hydrogen-based electric power solutions and create sustainable “green” LPG alternatives from CO2 and green hydrogen. | Publications, educational programmes, patents and commercial licensed technologies. | [80] |

| Sustainable Energy and Environment Research Unit (SEERU) | University of the Witwatersrand | Renewable Energy Production systems, mainly focus on biofuel and hydrogen for fuel cell. | To develop expertise through research and teaching tools for processes that are important for clean/or renewable energy production and sustainable environment. | Publications. | [81] |

Nonetheless, progress in electrolysis is supported by a combination of public and private stakeholders. Government departments including the Department of Science, Technology and Innovation; the Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment; the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy; and the Department of Higher Education and Training provide coordination, strategy development, and targeted funding for hydrogen-related research. These efforts are complemented by private-sector and non-governmental entities such as GreenCape, PwC, Mitochondria Energy Company, Trade & Industrial Policy Strategies (TIPS), and the South African Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA). Together, these organizations contribute technical studies, policy analysis, advisory services, and commercialization insights that expand the national research ecosystem.

Collectively, the emerging evidence indicates that South Africa’s RDI efforts are still in a formative phase but demonstrate increasing alignment with global technological trends. There is growing emphasis on developing locally relevant hydrogen technologies, evaluating the country’s resource endowment, and assessing pathways for industrial-scale production. However, current research remains fragmented, and many programmes are exploratory rather than oriented toward near-term commercialization. Strengthening coordination, ensuring stable funding, and expanding partnerships between academia, industry, and government will be essential for translating research outputs into deployable technologies. These elements are particularly important for South Africa, where innovation capacity will directly influence the competitiveness and long-term sustainability of the national green hydrogen economy.

Although recent developments indicate progress, South Africa must still place greater emphasis on research, development, and innovation across the green hydrogen value chain. Priority areas include the following:

- (i)

- Advancing direct knowledge transfer from international research programmes.

- (ii)

- Adapting and localizing global technologies to domestic conditions.

- (iii)

- Expanding primary research that focuses on national opportunities, including renewable integration, grid stability, and resource-specific optimization.

At present, RDI efforts remain fragmented, largely due to siloed institutional practices and an overreliance on global technology pathways that are not always suited to South Africa’s energy context. These dynamics limit the country’s ability to generate applied knowledge and to pursue innovations that reflect local constraints and competitive advantages. Strengthening collaboration across government, industry, and research institutions, alongside coordinated research agendas aligned with commercial and national priorities, is therefore essential. Such alignment will help concentrate resources on high-impact technological opportunities and enhance technological readiness for scaling critical systems such as electrolyzers.

4. Policy and Regulations

The development of green hydrogen as a key component of South Africa’s energy transition necessitates the establishment of a robust and comprehensive policy framework. Energy policies are essential for guiding production, distribution, and consumption of energy to ensure alignment with the country’s broader socio-economic goals. They also address the energy trilemma, balancing energy security, affordability, and environmental sustainability. Energy policies must avoid the pitfalls of overly ambitious goals that cannot be realized within the set timelines, as seen in some global contexts [82].

In South Africa, the integration of green hydrogen into the national energy mix is largely shaped by policy frameworks designed to facilitate the transition to a low-carbon economy. These policies, while addressing the broader decarbonization agenda, must be tailored to support specific aspects of green hydrogen production, from technological development to scale-up and commercialization. Table 4 outlines key gaps in the current policy frameworks, which highlight the need for more specific policies dedicated to green hydrogen development [55].

Table 4.

Comparative Summary of South Africa’s Hydrogen relevant Policy and Frameworks.

South Africa has released a suite of supporting policy frameworks, master plans, roadmaps, and strategies aligned with national decarbonization commitments. These instruments collectively shape the enabling environment for emerging low-carbon technologies, including green hydrogen.

The South African Renewable Energy Masterplan (SAREM) outlines a focused strategy to expand industrial capacity in renewable energy and storage, create jobs, strengthen local supply chains, and build technological capabilities. SAREM places notable emphasis on the development of green hydrogen technologies and new energy vehicles. Although its immediate priorities lie in solar PV, onshore wind, and energy storage, the Masterplan explicitly states that technologies such as electrolyzers will be increasingly incorporated as domestic supply and demand mature [83].

Similarly, the updated Integrated Resource Plan (IRP 2025) reinforces and operationalizes elements of the Hydrogen Society Roadmap (HSRM). The IRP highlights the strategic importance of the green hydrogen economy for supporting South Africa’s Just Energy Transition (JET). It acknowledges key drivers such as technology costs, localization pathways, infrastructure readiness, and system integration requirements. Importantly, the IRP is designed as an adaptive planning tool, allowing adjustments as technology prices, market conditions, and global hydrogen trade dynamics evolve [57].

Beyond their domestic significance, SAREM and the IRP also carry important global signalling effects. Together, they communicate to international markets many of which are seeking long-term partnerships for future hydrogen imports that South Africa is actively preparing to participate competitively in global green hydrogen and renewable energy value chains. This is particularly relevant for developed countries, including Japan, Germany, and the European Union, which have expressed interest in securing stable green hydrogen supply agreements with resource-rich partners.

Overall, these frameworks demonstrate that South Africa is taking steps to align national policy instruments with its green hydrogen ambitions. However, effective implementation, timely updates, and policy coherence across sectors will be essential to ensure that the country can leverage its competitive advantages and translate policy commitments into bankable, scalable, and inclusive green hydrogen development.

Bridging Technology and Policy

The Hydrogen Society Roadmap (HSRM) sets out South Africa’s long-term vision for developing the green hydrogen value chain from 2021 to 2040. Central to this roadmap is the proposed establishment of a national green hydrogen office, intended to serve as a coordinating entity for policy alignment, project development, and cross-sectoral collaboration. By consolidating institutional responsibilities, this office is expected to streamline regulatory processes, enhance investor confidence, and align technological deployment with national decarbonization objectives.

The HSRM also outlines several key outcomes for the emerging green hydrogen economy. These include the development of export-oriented hydrogen and ammonia markets, the decarbonization of heavy-duty transport and hard-to-abate industrial sectors such as steel and chemicals, and the expansion of local manufacturing capability across the hydrogen value chain. A major component of these targets is the localisation of electrolyzer production. The roadmap anticipates the deployment of approximately 1.7 GW of electrolyzer capacity in the Green Hydrogen Valley by 2030, scaling up to around 10 GW in the Northern Cape by 2030 and reaching nearly 15 GW by 2040 [84].

The magnitude of these deployment targets carries implications beyond national objectives. Large-scale electrolyzer roll-out offers potential to support global supply chain diversification, reduce international procurement risks, and contribute to lowering global electrolyzer costs through volume-driven learning effects. Such developments can also strengthen Africa’s collective positioning within the global hydrogen economy, particularly as international buyers seek reliable long-term supply partnerships.

Complementing these deployment ambitions, the HSRM places strong emphasis on advancing green hydrogen RDI. The HySA Programme plays a central role in this effort, focusing on technology development, local manufacturing, intellectual property commercialization, standards formulation, and workforce development [84]. Through these initiatives, South Africa’s investment in hydrogen RDI contributes to the global research ecosystem by fostering international collaboration, supporting knowledge transfer, and enabling technology spillovers that can accelerate cost reductions and improve performance across hydrogen technologies.

The HSRM also highlights the role of biomass integration in advancing green hydrogen and its derivative fuels, particularly sustainable aviation fuels (SAF). The roadmap identifies green hydrogen-based SAF as a strategic opportunity for South Africa’s aviation sector and emphasizes biomass as a key feedstock for these pathways. Biomass-derived crops, residues, and waste streams offer multiple environmental and socioeconomic advantages, including reduced lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions, enhanced energy security, and new income opportunities for rural communities. However, the sector faces substantial constraints. Scaling biomass feedstock production and establishing a supportive, coherent policy framework remain critical challenges that must be addressed to enable SAF deployment at meaningful scale [84].

A framework with more direct relevance to green hydrogen deployment is the Just Energy Transition Implementation Plan (JET-IP) for 2023–2027. The JET-IP identifies green hydrogen as one of six core national investment portfolios and outlines several enabling elements. These include the following [85]:

- (i)

- Dedicated climate finance, with approximately USD 0.7 billion of the USD 11.6 billion pledge allocated to green hydrogen development.

- (ii)

- Measures to stimulate supply and demand, strengthen access to electrolyzer technologies, and support domestic manufacturing capacity.

- (iii)

- Technology incubation and skills development to advance research, development, and innovation for critical electrolyzer components.

- (iv)

- Leveraging South Africa’s endowment of platinum-group metals (PGMs), which are central to catalytic and membrane-based hydrogen technologies.

Because international climate finance underpins a large portion of the JET-IP, the plan illustrates how coordinated donor support can accelerate hydrogen development in emerging economies, which is a point increasingly reflected in global climate diplomacy discussions.

Complementing this is the Green Hydrogen Commercialization Strategy (GHCS), which sets out a national vision for developing domestic production and export capabilities for green hydrogen and its derivative products. The GHCS emphasizes the importance of enabling technologies such as electrolyzes and identifies significant localization potential for components including membrane electrode assemblies, catalyst-coated membranes, and balance-of-plant systems [64]. Although the strategy does not explicitly link biomass technologies to hydrogen production, it recognizes national capabilities relevant to biomass integration through emerging opportunities in direct air capture, power-to-liquids, and biomass-derived synthesis gas. One notable initiative under the GHCS is the proposed e-methanol feasibility study in Humansdorp, Eastern Cape, which aims to develop a greenfield facility producing zero-carbon e-methanol for domestic and export markets. The proposed process integrates renewable electricity-based hydrogen with synthesis gas derived from a mixed feedstock of locally sourced biomass and unrecyclable municipal solid waste. This hybrid pathway links biomass valorisation with green hydrogen electrolysis and demonstrates how biomass can complement emerging power-to-X industries. By prioritizing export-oriented production and establishing technology partnerships in electrolyzers and synthetic fuels such as e-methanol, the GHCS positions South Africa as a potential anchor within future global hydrogen corridors, particularly for markets in the European Union, Japan, and South Korea [64]. These policy frameworks demonstrate that while green hydrogen remains the primary focus, biomass continues to offer strategic complementary value, particularly in SAF production, hybrid fuel pathways, and waste-to-energy applications. Realizing this potential will require coordinated policy alignment, targeted financial support, and sustained investment in scaling biomass supply chains alongside electrolyzer manufacturing and hydrogen infrastructure.

In recent years, efforts to develop provincial hydrogen strategies have accelerated, reflecting the growing need for decentralized planning aligned with national decarbonization objectives. One example is the Western Cape Green Hydrogen Strategy and Roadmap (2024), which is approved by the provincial cabinet in May 2024. Provincial-level strategies play an important role in building foundational capabilities for energy security, grid support, localization, job creation, and spatial planning. Collectively, they support the broader vision of a decentralized and regionally differentiated energy landscape. The Western Cape roadmap positions the province as a prospective green hydrogen hub within the emerging SADC Hydrogen Corridor. Its objective is to leverage green hydrogen to stimulate economic growth, enhance energy security, support industrial decarbonization, and develop export-oriented value chains. The province’s 2035 targets include enabling 15 GW of renewable energy generation for hydrogen production, thus reducing emissions by an estimated 5 Mt CO2-eq, and exporting 420 kt of hydrogen or its derivatives [86].

The strategy is structured around three pillars [86]:

- (i)

- Pillar 1-Enabling Environment: Development of institutional capacity through advanced skills programmes, research partnerships with universities, and innovation initiatives within HySA centres, including work on electrolyzer technologies.

- (ii)

- Pillar 2-Infrastructure and Industrial Capability: Planning for hydrogen-related infrastructure, including desalination facilities, water provisioning for electrolysis, and energy system integration. This pillar also prioritizes manufacturing development through the Atlantis SEZ and Freeport Saldanha.

- (iii)

- Pillar 3-Scaling and Market Access: Collaboration with the Northern Cape and Eastern Cape to advance the Saldanha Hydrogen Hub and facilitate access to export markets such as the European Union, Japan, and South Korea.

Overall, the Western Cape Green Hydrogen Strategy underscores the foundational role of research, development, and innovation in advancing green hydrogen technologies. Strengthened collaboration with universities, HySA centres, and specialized training programmes is presented as central to building a skilled workforce and fostering local technology development, which is an important priority given South Africa’s high unemployment rate.

The province’s focus on export readiness also positions South Africa to integrate into emerging cross-regional hydrogen corridors. While most policy frameworks do not explicitly mention biomass or biomass derivatives in hydrogen production, existing research highlights significant potential, particularly through biochar-assisted catalysis and other hybrid pathways. Despite these developments, green hydrogen policy, regulation, and implementation in South Africa remain in an early stage of evolution. The ambition to become a major producer and exporter of green hydrogen is constrained by several structural challenges. South Africa currently lacks large-scale electrolyzer manufacturing capacity, has limited import capability for key components, and maintains an underdeveloped supply chain. Persistent electricity instability, slow REIPPPP procurement cycles, and transmission constraints undermine the availability of low-cost renewable electricity required for competitive hydrogen production. Furthermore, while the updated NDC and associated frameworks rely on green hydrogen to decarbonize hard-to-abate sectors, the state faces significant fiscal constraints and competing socio-economic priorities, including poverty alleviation, unemployment, and immediate energy security concerns. These factors limit the government’s ability to mobilize the investment and institutional capacity needed to realize its hydrogen ambitions. The resulting misalignment between long-term targets and current implementation capability remains a central barrier to scaling South Africa’s hydrogen economy within the required timeframe.

5. Outlook and Policy Recommendations

Future progress in green hydrogen development will increasingly rely on advanced catalytic materials capable of improving system efficiency, stability, and cost performance. Biochar shows emerging potential as a low-cost, carbon-based catalyst support for both water electrolysis and hybrid hydrogen production pathways. Although biochar-based catalysts currently do not match the performance of state-of-the-art water-splitting materials, ongoing research illustrates that their catalytic activity can be significantly enhanced through improved surface functionalization, deeper understanding of their amorphous structure, and advanced modelling of electron transfer processes. These improvements could enable biochar to serve as a scalable, locally available catalyst option that also supports waste valorization and carbon management. Such dual benefits position biochar as a relevant component of future hydrogen and power-to-X systems, especially in biomass-rich regions such as South Africa.

More broadly, South Africa’s ability to build a competitive green hydrogen economy will depend on cost reductions in electrolyzer technologies, expanded renewable electricity capacity, and the localization of critical components within the value chain. While the country has made progress in establishing overarching decarbonization policies, significant gaps remain between ambition and implementation capacity. The REIPPPP has demonstrated success in attracting private investment and expanding solar and wind generation, yet similar momentum has not been achieved for hydrogen-specific technologies and infrastructure. South Africa’s fiscal constraints, competing socio-economic priorities, and unstable electricity supply continue to limit the pace at which green hydrogen initiatives can be deployed. Several studies highlight that despite falling global electrolyzer costs, many African countries, including South Africa, may struggle to prioritize hydrogen investment over more immediate developmental needs [87].