Abstract

Thermodynamic entropy generation quantifies irreversibility in energy conversion processes, providing rigorous thermodynamic foundations for optimizing efficiency and sustainability in thermal and energy systems. This critical review synthesizes advances in computational entropy modeling across numerical methods, optimization strategies, and sustainable energy applications. Computational fluid dynamics, finite element methods, and lattice Boltzmann methods enable spatially resolved entropy analysis in convective, conjugate, and microscale systems, but exhibit varying maturity levels and accuracy–cost trade-offs. The minimization of entropy generation and the integration of artificial intelligence demonstrate quantifiable performance improvements in heat exchangers, renewable energy systems, and smart grids, with reported efficiency gains of 15 to 39% in specific applications under controlled conditions. While overall performance depends critically on system scale, operating regime, and baseline configuration, persistent limitations still constrain practical deployment. Systematic conflation between thermodynamic entropy (quantifying physical irreversibility) and information entropy (measuring statistical uncertainty) leads to inappropriate method selection; validation challenges arise from entropy’s status as a non-directly-measurable state function; high-order maximum entropy models achieve superior uncertainty quantification but require prohibitive computational resources; and standardized benchmarking protocols remain absent. Research fragmentation across thermodynamics, information theory, and machine learning communities limits integrated frameworks capable of addressing multi-scale, transient, multiphysics systems. This review provides structured, cross-method, application-aware synthesis identifying where computational entropy modeling achieves industrial readiness versus research-stage development, offering forward-looking insights on physics-informed machine learning, unified theoretical frameworks, and real-time entropy-aware control as critical directions for advancing sustainable energy system design.

1. Introduction

Entropy generation and exergy analysis have emerged as indispensable frameworks for quantifying irreversibility and thermodynamic losses in thermal and energy systems, addressing fundamental limitations inherent in first-law energy analysis. Entropy generation minimization (EGM) provides rigorous thermodynamic foundations for optimizing renewable energy systems across biomass, wind, solar photovoltaic, and geothermal technologies, demonstrating quantifiable efficiency improvements through systematic irreversibility reduction [1]. Although energy conservation satisfies the mass and energy balances, it does not capture degradation in energy quality during conversion or identify locations and magnitudes of inefficiency [2]. Exergy analysis extends second-law principles by quantifying the maximum useful work obtainable from systems. This reveals that energy transformations inevitably generate entropy through heat transfer across finite temperature differences, viscous dissipation, and chemical reactions [3,4]. This distinction is critical for sustainable energy systems, where optimizing performance requires minimizing irreversibility to maximize useful work extraction from finite resources. Throughout this review, the term ‘entropy’ refers exclusively to thermodynamic entropy as defined by the second law of thermodynamics, which quantifies irreversibility and energy quality degradation in physical processes. This must be distinguished from information entropy (Shannon entropy measuring statistical uncertainty in data) and configurational entropy (statistical disorder in molecular arrangements). These three concepts, while mathematically related through logarithmic formulations, represent fundamentally different physical phenomena requiring distinct computational approaches. Unless explicitly stated otherwise, all entropy discussions herein address thermodynamic entropy generation in energy systems.

Computational methods have fundamentally transformed entropy modeling capabilities, enabling spatially, resolved transient analysis of complex energy systems previously inaccessible through analytical approaches. Classical thermodynamic modeling has been progressively integrated with advanced computational techniques, bridging theoretical foundations with data-driven applications [5]. Machine learning applications in sustainable energy systems have expanded entropy modeling through improved predictive accuracy, uncertainty quantification, and optimization under variable conditions [6]. Artificial intelligence integration in energy conversion demonstrates enhanced process optimization, with hybrid models combining entropy concepts with deep learning or Bayesian inference achieving superior performance in handling complex, nonlinear, uncertain energy data [7]. Physics-informed frameworks increasingly embed thermodynamic constraints, with entropy-driven deep reinforcement learning achieving substantial HVAC energy savings and maximum entropy principles providing robust uncertainty quantification in stochastic renewable systems [8,9]. Graph-based modeling for transient exergy analysis enables the quantification of dynamic entropy in integrated systems, while entropy-based stochastic optimization incorporates higher-order sensitivities to address modeling uncertainties [10,11].

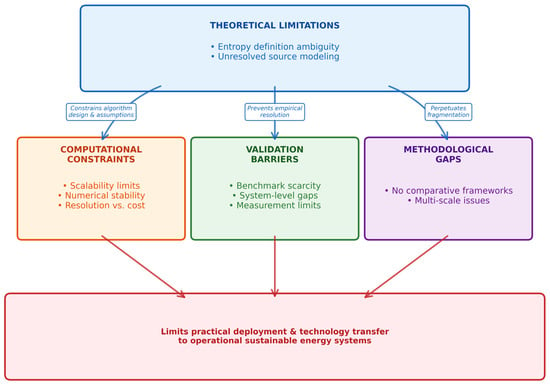

Despite these advances, persistent conceptual gaps and methodological fragmentation motivate a comprehensive synthesis. Theoretical ambiguities regarding entropy definitions and appropriate application contexts persist, with systematic conflation between thermodynamic entropy (quantifying energy dispersal) and information entropy (measuring statistical uncertainty) leading to inappropriate computational method selection [2]. Research approaches remain fragmented across disciplinary boundaries: thermodynamic EGM studies often proceed independently from information-theoretic entropy applications in economic dispatch, while AI-enhanced entropy modeling develops with limited integration of established thermodynamic principles [12,13]. Validation challenges constrain practical deployment, as computational models often lack extensive experimental or real-world validation, reducing confidence in predictive accuracy and practical applicability [5]. Scalability limitations persist, as high-order maximum entropy predictive models incorporating fourth-order sensitivities achieve superior uncertainty quantification but require computational resources prohibitive for real-time optimization of large-scale networks [14]. The rapid proliferation of entropy-based optimization methods occurs without standardized benchmarking protocols, preventing systematic performance comparison and method selection guidance [10].

The growing need for cross-disciplinary and methodologically integrated reviews arises from converging factors. Urban energy systems face increasing complexity in demand aggregation and renewable dispatch, which requires entropy-based methods to quantify information loss and optimize spatial scales [15]. Renewable integration introduces stochastic generation that demands robust uncertainty quantification frameworks, with entropy providing effective variability metrics [16]. Multi-energy systems that link electrical, thermal and chemical networks exhibit complex interactions that require integrated entropy–exergy analysis to identify optimization opportunities [4]. Emerging applications span electric vehicle charging reliability, blockchain-based renewable trading, and the sustainability of urban green systems, demonstrating the expanding role of entropy beyond traditional thermodynamic domains [17,18,19]. The interdisciplinary nature of computational sustainability, which encompasses thermodynamics, information theory, artificial intelligence, and socio-technical perspectives, requires comprehensive frameworks that synthesize various methodologies [20].

This review addresses these gaps through the comprehensive synthesis of advances in computational entropy modeling in theoretical foundations, numerical methods, optimization strategies, and emerging sustainable energy applications. The review systematically evaluates how entropy generation analysis reveals fundamental performance limits, how computational methods enable rigorous quantification of entropy with varying accuracy–cost trade-offs, how entropy-based optimization frameworks balance competing irreversibilities, and how these approaches translate to practical efficiency improvements in heat exchangers, renewable energy systems, smart grids, and urban infrastructure. By integrating thermodynamic rigor with computational innovation and identifying critical limitations alongside demonstrated successes, this review provides foundations for advancing entropy modeling as a cornerstone methodology for sustainable energy system design and operation.

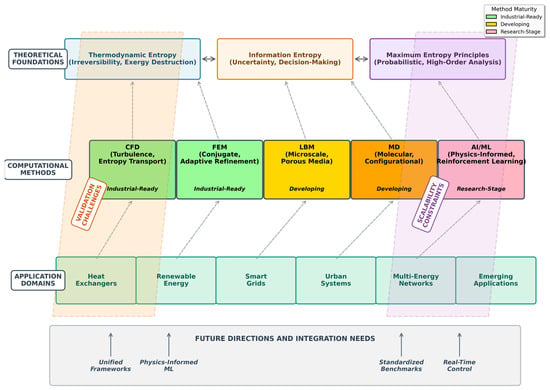

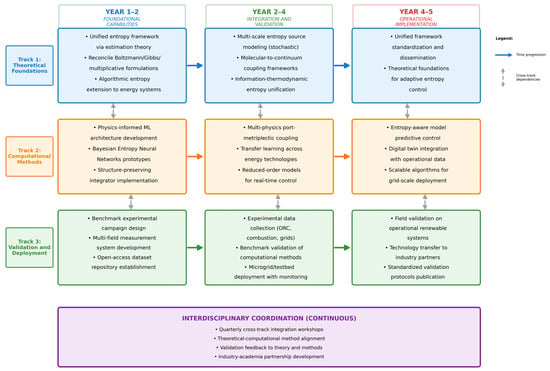

Figure 1 presents a conceptual overview of the structure of the review, synthesizing the key layers of computational entropy modeling in sustainable energy systems. It illustrates how core entropy frameworks—thermodynamic, information-theoretic, and maximum entropy principles—anchor a range of computational methods that vary in maturity and application readiness. These methods are mapped to the main application areas, highlighting how theoretical developments translate into practical tools. The framework also visualizes cross-cutting challenges, such as scalability and validation, alongside emerging directions, including real-time control and standardized benchmarking.

Figure 1.

Conceptual overview of computational entropy modeling in theory, methods, and applications.

2. Fundamentals of Entropy in Applied Thermodynamics

This section investigates the theoretical foundations and practical implications of entropy in thermal systems. It addresses entropy generation in closed and open systems, the role of the second law and exergy analysis, and the methodological distinction between configurational and generated entropy. Emphasis is placed on the mechanisms of entropy production in heat transfer, thermal–frictional trade-offs, and entropy behavior in power generation and energy storage systems under variable operating conditions.

2.1. Theoretical Framework of Entropy

2.1.1. Entropy Generation in Closed and Open Systems

The theoretical framework of entropy generation distinguishes between closed and open thermodynamic systems. In closed systems, entropy generation quantifies irreversibility through the difference between phenomenological entropy (evaluated over irreversible paths) and reversible entropy (calculated along ideal reversible paths) [21]. However, practical application faces significant challenges. The selection of appropriate thermodynamic potentials remains non-trivial and system-dependent [21]. However, most computational implementations adopt standardized functions without justification. More fundamentally, the status of entropy as a mathematical state function versus a measurable physical property creates a validation paradox [22,23]. If entropy lacks direct physical measurability, computational predictions cannot be definitively validated. Most validation efforts rely on indirect inference from temperature and pressure measurements, introducing compounding uncertainties rarely quantified in the literature.

Open systems introduce additional complexity through mass and energy exchange. In open quantum systems, entropy generation is related to the separation of internal energy changes into heat and work contributions [24]. The dynamics of the entropy production rate depend critically on the initial states, environmental conditions, and interaction parameters [25]. Recent molecular dynamics frameworks have incorporated non-equilibrium thermodynamics, where time scaling factors measure entropy production rates dynamically rather than as post-processing [26]. Additionally, explicit configurational entropy calculations from instantaneous particle coordinates now enable real-time mixing dynamics analysis [27]. These advances bridge atomistic simulations with continuum entropy analysis, enabling identification of irreversibility sources during transient phenomena.

A critical methodological concern emerges from systematic conflation between entropy generation (irreversibility in non-equilibrium processes, measured in [J/(K·s))] and configurational entropy (statistical disorder in equilibrium states, measured in [J/K]). Three different concepts of entropy appear in the broader literature, but must not be conflated [28,29,30]:

- Thermodynamic entropy generation (): irreversibility in non-equilibrium processes ([W/K] or [J/(K·s)]), arising from heat transfer, viscous dissipation, and mass diffusion. Quantified via entropy transport equations.

- Configurational entropy S(config) ([J/K]): statistical disorder in equilibrium molecular arrangements [J/K], calculated from partition functions or molecular dynamics ensemble averaging. Relevant for battery materials and mixing phenomena.

- Information entropy H ([bits] or [nats]): uncertainty measure in probability distributions [bits or nats], defined by Shannon formula , where —the probability of the i-th event, for units in bits, or for units in nats.

The selection of computational methods critically depends on the entropy type: CFD with entropy transport equations for thermodynamic entropy generation; molecular dynamics for configurational entropy; statistical algorithms for information entropy. Confusing these concepts leads to order-of-magnitude errors in computational cost and physically inconsistent results.

The rigorous theoretical foundation for entropy generation stems from the local entropy balance derived from the second law of thermodynamics [31,32]. For a control volume Ω with boundary ∂Ω, the entropy balance states [31,33]:

where the left side represents entropy accumulation [W/K], the first right-hand term is convective entropy flux [W/K], the second is conductive entropy flux (reversible) [W/K], and the third is entropy production (irreversible) [W/K]. The variables are: ρ—density [kg/m3], s—specific entropy [J/(kg·K)], u—velocity vector [m/s], n—outward unit normal [–], q—heat flux vector [W/m2], T—absolute temperature [K], and —volumetric entropy generation rate [W/(m3·K)] [31,33].

Applying the divergence theorem and taking the local limit yields the differential form is [31,33]:

The second law requires ≥ 0 at every point and instant, with equality holding only for reversible processes [31,32]. Substituting Fourier’s law q = −k∇T and expanding the divergence [33,34]:

This formulation separates reversible entropy transport (first two terms on left, first term on right) from irreversible entropy production (last term) [31,33]. The entropy generation rate emerges from the Clausius–Duhem inequality, which ensures thermodynamic consistency [35,36]:

where e is the specific internal energy [J/kg] and τ is the stress tensor [Pa]. This inequality requires that internal dissipation always increases entropy [35,36]. Combined with constitutive relations (Fourier’s law for heat conduction, Newton’s law for viscous stress, Fick’s law for mass diffusion), the Clausius–Duhem inequality yields explicit expressions for thermal, viscous, and diffusive entropy generation [32,34,36].

The Gouy–Stodola theorem connects entropy generation to exergy destruction [1,18]:

where is exergy destruction rate [W], T0 is reference (dead state) temperature [K], and is total entropy generation rate [W/K]. This theorem establishes that minimizing entropy generation is equivalent to minimizing exergy destruction, providing the thermodynamic foundation for entropy generation minimization (EGM) as an optimization strategy [37,38].

2.1.2. The Second Law and Exergy Analysis

The second law of thermodynamics governs the directionality of energy transformations. Exergy analysis extends this principle by quantifying the maximum useful work available from systems, integrating first- and second law considerations [39]. Unlike energy-based analyses satisfying conservation principles, exergy analysis identifies quality degradation in energy conversion processes. Modern computational frameworks suggest the second law emerges from computational irreducibility, where process complexity and observer limitations contribute to apparent entropy increase [40]—a philosophically provocative stance lacking widespread acceptance.

Although exergy analysis theoretically provides superior system evaluation, practical implementation confronts significant challenges that are rarely acknowledged. Exergy calculations require the specification of reference dead states (ambient temperature T0 and pressure P0), yet this dependency receives inconsistent treatment. Different research groups employ varying reference conditions without acknowledging comparability limitations. For systems at elevated temperatures, variations in the T0 specification substantially alter the calculated exergy destruction. Furthermore, real environments fluctuate seasonally and diurnally, yet analyses assume fixed reference conditions. Time-varying reference states would provide more realistic assessments, but are computationally prohibitive. Since exergy combines energy (measurable) with entropy (not directly measurable), experimental validation typically achieves substantially higher uncertainty than energy balance validation. This uncertainty often exceeds the claimed optimization improvements, rendering validation inconclusive. Despite this limitation, most computational exergy studies present results without uncertainty quantification or sensitivity analysis with respect to reference state selection.

Recent applications demonstrate utility despite limitations. Solar-assisted distillation systems benefit from exergy-based efficiency evaluations that identify irreversibility sources [41]. Gas turbine analyses quantify irreversible losses through exergy destruction mapping [42]. However, these studies present results without addressing fundamental validation challenges. Theoretical foundations span classical thermodynamics, quantum mechanics, statistical mechanics, and information theory—creating conceptual fragmentation. For computational practitioners, this diversity presents both opportunities (cross-validation across methods) and challenges (ambiguity in method selection). The fundamental tension between entropy as a mathematical state function versus measurable physical property remains unresolved, leaving entropy-based optimization with inherent validation limitations that energy-based optimization does not face.

2.2. Entropy and Irreversibility in Heat Transfer

2.2.1. General Mathematical Framework for Entropy Generation

The local volumetric entropy generation rate for multi-physics systems follows from the Gouy–Stodola theorem and irreversible thermodynamic principles [32,38]. The total entropy generation rate decomposes into contributions from distinct physical mechanisms:

From Fourier’s law and temperature gradients, thermal entropy generation arises from heat conduction across finite temperature differences [34,38]:

where k is thermal conductivity [W/(m·K)], T is absolute temperature [K], and ∇T is the temperature gradient [K/m].

For anisotropic media with conductivity tensor k, the expression generalizes to the following:

This formulation ensures positive entropy production for all non-zero temperature gradients, consistent with the second law of thermodynamics [32,34].

From the Newtonian stress tensor τ and velocity gradients, viscous entropy generation quantifies irreversibility due to fluid friction [38,43]:

where μ is dynamic viscosity [Pa·s], u is the velocity vector [m/s], and is the viscous dissipation function [s−2]. The viscous dissipation function depends on the coordinate system [43,44].

Cartesian coordinates (x, y, z):

Cylindrical coordinates (r, θ, z):

For non-Newtonian fluids following the power-law model , where K is consistency index [Pa·sn] and n is flow behavior index [-].

The generation of viscous entropy becomes [45,46]:

where is the magnitude of the rate-of-deformation tensor [s−1].

For multi-component systems with species diffusion, mass transport irreversibility arises from concentration gradients [47,48]:

where R is the universal gas constant [J/(mol·K)], Ji—molar diffusion flux of the species i [mol/(m2·s)], and μi—chemical potential of the species i [J/mol]. For ideal gas mixtures, μi = μi0 + RT ln(xi), where xi—mole fraction [–] [48].

Using Fick’s law Ji = −Di∇Ci, where Di is the diffusion coefficient [m2/s] and Ci is the molar concentration [mol/m3], the simplified form becomes:

From the reaction affinity and the reaction rate rj, the irreversibility of the chemical reaction follows [47,49]:

For a single irreversible reaction with affinity = −ΔG(rxn), where ΔG(rxn)—Gibbs free energy change [J/mol]:

where ΔH(rxn)—enthalpy change [J/mol], ΔS(rxn)—entropy change [J/(mol·K)], and r—reaction rate [mol/(m3·s)] [49].

For conducting media with current density J [A/m2] and electric field E [V/m], electromagnetic irreversibility arises from Joule heating [50,51]:

where σ is electrical conductivity [S/m].

For magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) flows with magnetic field B [T] and velocity u [m/s], the induced electric field contributes to additional entropy generation [51]:

In coupled transport phenomena, cross-effects between heat, mass, and momentum transfer contribute to the generation of entropy [48,52]. The Soret effect (thermal diffusion) and Dufour effect (diffusion thermo) introduce coupling terms:

where Jq is the total heat flux [W/m2], including both Fourier and Dufour terms, and Ji is the mass diffusion flux, including the Soret contribution [48,52].

This general framework is reduced to simplified forms under specific assumptions: single-phase, single-component, negligible electromagnetic effects, and local thermodynamic equilibrium [34,38].

2.2.2. Thermal–Viscous Entropy Trade-Offs

Before examining specific entropy production mechanisms (Section 2.2.3), it is essential to understand the fundamental trade-off governing heat transfer optimization: interventions that reduce thermal irreversibility typically increase viscous dissipation, and vice versa.

A fundamental challenge in heat transfer optimization emerges from opposing trends in thermal and viscous entropy generation. The total entropy generation rate decomposes:

where denotes the entropy generated by heat conduction across temperature gradients, and represents entropy produced by viscous dissipation (fluid friction).

Every intervention that improves heat transfer simultaneously increases friction. Experimental investigations of entropy generation in pipe heat exchangers with turbulence generators have provided rare experimental validation [53]. Turbulators increased total entropy depending on the configuration, with heat transfer irreversibility dominating. Optimal turbulator pitch exists in specific pitch-to-diameter ratios, minimizing total entropy. External turbulators generated less entropy than internal designs for equivalent enhancement. Experimental validation showed that computational predictions agreed with measurements within reasonable tolerances for total entropy, providing confidence in numerical approaches.

Numerical investigations of entropy generation for refrigerant flow boiling in corrugated U-bend tubes demonstrated that the effects of surface corrugation depend on the flow regime [54]. In boiling nucleates at low vapor quality, the benefits of corrugation outweigh the penalties. In convective boiling with high vapor quality, the reverse occurs as vapor-phase viscous dissipation dominates. This flow-regime-dependent behavior complicates optimization, requiring spatially varying enhancement for systems operating across multiple regimes.

Several approaches address thermal–frictional trade-offs. The minimization of classical entropy generation seeks operating conditions that minimize total entropy [55]. However, recent theoretical work demonstrated that maximizing productive entropy (heat transfer alone) while minimizing viscous entropy generation can optimize performance more effectively [55]. The key insight: thermal entropy generation is productive (accompanies desired heat transfer), while viscous entropy generation is parasitic. Treating thermal and viscous entropy generation as separate objectives generates Pareto fronts revealing trade-off relationships. Comparative studies found that entropy-based objective functions outperformed volume-based approaches [56].

The Bejan number () [-] indicates relative importance of thermal versus frictional irreversibility. Systems with Be >> 0.5 improved heat transfer enhancement despite pressure penalties; systems with Be << 0.5 a reduction in friction. This dimensionless parameter provides decision framework for optimization strategy selection, yet remains underutilized.

2.2.3. Entropy Production Mechanisms

Heat conduction generates an entropy proportional to the magnitude of the temperature gradient and inversely to the absolute temperature, as quantified by Equation (7) [57,58]. Since entropy generation scales with 1/T2, lower temperatures amplify conduction irreversibility for identical gradients, although cryogenic systems require detailed property modeling due to strong temperature-dependent conductivity [55]. Minimizing temperature gradients reduces conduction entropy, but often requires increased heat transfer area or enhanced convection, introducing trade-offs with other entropy sources.

Convective heat transfer generates entropy through thermal and viscous mechanisms [59,60]:

where μ is dynamic viscosity [Pa·s] and Φ is the viscous dissipation function [s−2].

This expression is valid for incompressible Newtonian fluids under the assumptions of steady-state flow and negligible body forces. The first term represents thermal irreversibility, while the second one accounts for viscous (mechanical) dissipation due to velocity gradients. This dual-source nature creates fundamental optimization challenges. Enhancing convection through higher Reynolds numbers (Re) improves heat transfer and reduces thermal entropy generation but substantially increases viscous dissipation, increasing viscous entropy. Turbulence improves mixing and typically reduces the thickness of the thermal boundary layer, decreasing the generation of thermal entropy. However, it also introduces steep velocity gradients, especially near walls, which significantly increase viscous entropy. The net effect depends on the flow regime, Re, and the properties of the fluid. The Prandtl number (Pr), which relates momentum diffusivity to thermal diffusivity, influences the relative thickness of the velocity and thermal boundary layers. Its role in the balance of the entropy generation is indirect but important when designing systems where viscous and thermal effects compete.

A dimensionless entropy generation number (Ns) can be defined to evaluate irreversibility [57,60]:

where [W/K] is the total entropy generated within the system, [K] is the reference temperature, and [W] is the total heat transfer rate. This formulation facilitates optimization by providing a nondimensional measure of irreversibility; however, its exact definition may vary across studies depending on the chosen scaling parameters (e.g., heat capacity rates or inlet temperatures).

Studies on natural convection demonstrate that optimizing geometry and configuration can substantially minimize this parameter [61]. However, optimizations are highly geometry-specific. Recent computational studies analyzed entropy generation in heat exchangers with perforated conical ring turbulators, revealing that turbulator geometry significantly affects thermal–viscous entropy balance, with optimal designs achieving substantial reduction compared to smooth tubes [62]. Strategic flow disruption can reduce net entropy despite increased viscous dissipation—challenging conventional wisdom. Perforated designs allow some flow through holes, maintaining bulk momentum while creating localized mixing.

Radiative heat transfer generates entropy through the propagation of electromagnetic wave [63]. The volumetric entropy generation rate due to radiation is as follows:

where σ is the Stefan–Boltzmann constant (σ = 5.67 × 10−8 W/(m2·K4)) and ε is the emissivity [-].

In high-temperature environments, radiative entropy can dominate total irreversibility. Most CFD studies neglect radiative contributions, assuming conduction–convection dominance. This assumption holds for low-temperature systems or low-emissivity surfaces but fails otherwise. Recent studies employing the Lattice Boltzmann method (LBM) have investigated entropy generation in natural convection under systematically varied surface emissivity and Rayleigh number (Ra) conditions [64]. The results indicate that at low emissivity (ε < 0.3), radiation contributes minimally, validating neglect in entropy analyses. At high emissivity (ε > 0.7), radiation contributes substantially, becoming co-dominant with conduction. Neglecting radiation introduces substantial prediction errors. This work establishes quantitative criteria for when radiation must be included.

Comparative entropy analysis on plate, shell-and-tube and double-pipe heat exchangers using nanofluids with varying volume fractions has provided quantitative guidance [65]. As shown in Table 1, plate heat exchangers exhibited the lowest entropy generation at optimal nanoparticle concentration, attributed to the high surface area density and thin flow channels. A volumetric concentration of approximately 4% represented an optimal threshold; higher concentrations increased viscous entropy faster than thermal entropy generation decreased. This threshold appears robust across nanoparticle types and base fluids, suggesting a fundamental physical limit related to particle–particle interactions. CFD analysis of evacuated tube solar collectors using TiO2 and SiO2 water-based nanofluids demonstrates substantial entropy generation reductions: heat transfer entropy decreases by 77.5% (TiO2) and 79% (SiO2) compared to pure water at 735 W/m2 solar radiation [66]. Thermal entropy generation dominates by approximately three orders of magnitude over viscous entropy (0.014 W/K vs. 5 × 10−6 W/K for TiO2), with heat loss accounting for 95% of total entropy generation, confirming that optimization efforts in solar thermal systems must prioritize thermal irreversibility reduction [66].

Table 1.

Heat Transfer Entropy Generation Mechanisms and Optimization.

2.3. Entropy in Power Generation and Energy Storage

2.3.1. Entropy Production in Power Systems

Entropy generation in power generation systems correlates directly with efficiency losses. Combustion irreversibility arises from viscous dissipation, heat conduction, mass diffusion, and chemical reactions [67]. In premixed flames, the chemical reaction dominates exergy loss. In diffusion flames, heat conduction becomes more significant because of steep temperature gradients. The uncertainty in combustion entropy quantification remains poorly characterized, with studies reporting substantial variations under nominally identical conditions. Sources include chemical kinetics (detailed mechanisms predict substantially different entropy than single-step mechanisms), turbulence–chemistry interaction, and boundary conditions.

An inverse relationship has been demonstrated between thermal efficiency and specific entropy generation in combustion systems [68]. However, this relationship breaks down under very lean conditions, where the combustion instability introduces additional irreversibility not captured by steady-state entropy analysis. This limitation—that steady-state analysis fails for unsteady combustion—receives insufficient attention. Gas turbines experience entropy generation through aerodynamic losses, heat transfer irreversibility, and mixing losses [42]. However, an off-design operation dramatically alters the entropy distribution—a critical consideration rarely addressed.

Recent analysis of entropy production in radial inflow turbines with variable input guide vanes under off-design conditions revealed the inadequacy of design-point optimization [69]. Local entropy generation increases substantially at part load, with the greatest increases in the tip and hub regions. High entropy generation regions shift spatially from rotor mid-span at design conditions to tip/hub at off-design. Variable guide vanes substantially reduce the generation of entropy across the operating range. Entropy-based optimization at the design point does not guarantee off-design performance.

2.3.2. Entropy in Energy Storage

Energy storage systems exhibit unique entropy characteristics related to charge/discharge cycles and phase transitions. The battery literature uses “entropy” in three distinct senses: (1) thermodynamic entropy generation—irreversibility during charge/discharge from ohmic losses and concentration gradients; (2) configurational entropy—equilibrium statistical mechanics of mixing in multi-component electrodes; and (3) entropy coefficient (∂V/∂T)—reversible thermodynamic property characterizing voltage–temperature dependence. These are physically distinct phenomena that require different modeling approaches. Configurational entropy can improve performance by stabilizing crystal structures, entropy generation always degrades performance, and the entropy coefficient determines thermal management requirements. Configurational entropy can improve performance by stabilizing crystal structures; entropy generation always degrades performance; and the entropy coefficient determines thermal management requirements.

High-entropy materials improve electrochemical performance by improving improved ion/electron transport and structural stability [70]. Entropy-regulated electrolytes in zinc batteries improve ion transport and cycling life substantially [71]. The entropy coefficients in silicon-carbon anodes affect the heat requirements for heat generation and battery management [72]. Silicon anodes exhibit strongly state-of-charge-dependent entropy coefficients with sign changes. An extended analysis of the state-of-charge and aging conditions revealed critical practical implications [72]. The entropy coefficient varies nonlinearly with the state-of-charge, exhibiting sign changes corresponding to phase transitions. Aging reduces the magnitude of the entropy coefficient, altering thermal behavior. Accurate thermal modeling requires state-of-charge- and age-dependent entropy coefficients. Models using constant coefficients predict temperature within acceptable tolerances for fresh cells but show substantial errors for aged cells. This work challenges common battery thermal modeling practices that treat entropy coefficients as constants.

Entropy generation in latent thermal energy storage systems indicates irreversibility during melting/solidification [73]. Recent work proposed using the entropy generation rate as an indicator of charge completion, offering practical advantages over traditional methods that require distributed sensing [73]. The entropy generation rate can be inferred from inlet/outlet temperature and flow rate measurements alone. The entropy generation rate peaks during active melting and then decays exponentially as melting completes. Analysis of entropy generation in variable-wavy-walled triplex tube latent heat storage revealed geometry optimization opportunities [74]. The wavy wall geometry substantially reduced entropy generation compared to straight tubes. Optimal wave amplitude exists; excessive amplitude increases viscous entropy more than thermal benefit. As summarized in Table 2, the entropy characteristics in the power generation and energy storage systems vary substantially depending on operating conditions, aging state, and system configuration.

Table 2.

Entropy in Power Generation and Energy Storage Systems.

3. Computational Methods for Entropy Analysis

This section presents recent advances in numerical methods for the analysis of entropy generation across thermal and fluid systems. Specifically, it focuses on computational fluid dynamics (CFD), finite element methods (FEM), and LBM, describing the governing equations, turbulence modeling, and entropy transport formulations. Special attention is given to adaptive meshing, entropy-stable solvers, and multi-physics coupling strategies. The comparative evaluation of accuracy, scalability, and suitability guides the selection of the method for diverse applications, including heat exchangers, porous media, and microscale systems.

3.1. Overview of Discretization Approaches

CFD provides the overarching framework for numerically solving entropy transport and generation in thermal–fluid systems. Within this framework, the governing partial differential equations are discretized into algebraic systems, and the selected discretization method determines accuracy, computational cost, and suitability for different classes of entropy analysis.

The finite volume method (FVM), widely used in commercial solvers such as ANSYS Fluent, OpenFOAM, and STAR-CCM+, discretizes conservation laws in integral form over control volumes, ensuring inherent conservation and robustness for fluid-based entropy generation studies. FEM, based on weak formulations with domain-specific basis functions, is particularly effective for conjugate heat transfer and solid-state entropy generation, widely implemented in multiphysics tools such as COMSOL and ANSYS Mechanical. The finite difference method (FDM) approximates differential operators through Taylor series expansions on structured grids. Although efficient for canonical geometries, its limited geometric flexibility restricts its industrial use. The LBM instead operates at the mesoscopic scale, discretizing the Boltzmann transport equation on Cartesian lattices. This kinetic-based formulation excels in microscale, porous, and transient entropy applications. At the molecular level, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations capture configurational entropy directly from statistical mechanics, bridging quantum and continuum scales. MD is indispensable for nanoscale systems where continuum assumptions fail.

Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics (SPH) provides a Lagrangian meshless approach discretizing fluid motion through moving particles, providing a conservative entropy formulation for compressible flows with discontinuities and complex free surfaces. Direct Simulation Monte Carlo (DSMC) operates at the kinetic level, solving the Boltzmann equation through probabilistic particle collisions, providing a statistical mechanics basis for entropy analysis in rarefied gas flows where continuum assumptions break down.

Each method balances fidelity and computational efficiency differently: FVM offers robustness, FEM geometric flexibility, FDM simplicity, LBM kinetic resolution, MD atomistic detail, SPH meshless adaptability for free surfaces, and DSMC statistical mechanics foundation for rarefied flows.

3.2. Computational Fluid Dynamics

3.2.1. Governing Equations and Entropy Transport

CFD enables spatially resolved analysis of thermodynamic entropy generation by solving the conservation laws of mass, momentum, and energy, in conjunction with thermodynamic entropy balances. Under the assumptions of a Newtonian incompressible single-phase fluid in local thermodynamic equilibrium, the differential form of the entropy transport equation is [75,76]:

where is the fluid density [kg/m3], is specific entropy [J/(kg·K)], and is the volumetric entropy generation rate [W/(m3·K)].

The local entropy generation comprises thermal and viscous contributions [77,78]:

This formulation enables the identification of irreversibility hotspots in complex geometries. However, practical implementation faces significant challenges. Accurate entropy calculation requires high-quality velocity and temperature gradient fields, which require fine mesh resolution in boundary layers and shear regions [78]. Numerical diffusion in convective terms can artificially suppress entropy generation peaks, particularly in high-Re flows where gradients are steep. Most commercial CFD codes compute the entropy as a post-processing value rather than directly solving transport equations, introducing additional approximations [75].

Turbulence modeling significantly affects predicted entropy generation. Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes approaches with two-equation turbulence models provide time-averaged entropy fields, but cannot capture instantaneous fluctuations contributing to irreversibility [77,78]. The turbulent entropy generation must be modeled separately, typically through a turbulent dissipation rate. Large-eddy simulation offers improved accuracy by resolving large-scale turbulent structures, but the computational cost increases substantially. Direct numerical simulation provides exact entropy fields but remains prohibitively expensive for engineering applications at practical Reynolds numbers. The choice of turbulence modeling approach introduces uncertainties in the predicted entropy generation that can exceed differences between design alternatives, but sensitivity analysis regarding turbulence model selection remains rare in the literature [77].

3.2.2. Turbulence Modeling and Numerical Accuracy

CFD methods for entropy generation analysis in turbulent thermal flows rely on solving the Navier–Stokes equations coupled with energy and species transport equations. The governing equations include continuity, momentum, and energy conservation, supplemented by turbulence closure models that account for unresolved scales. In the context of entropy generation, the local entropy production rate is computed from velocity and temperature gradients, requiring accurate resolution of these fields under turbulent, non-isothermal, and compressible conditions [79,80]. Advanced turbulence models—Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS), Large Eddy Simulation (LES), hybrid RANS-LES, and Direct Numerical Simulation (DNS)—differ fundamentally in their treatment of turbulent scales and thus influence the fidelity of entropy prediction.

The key dimensionless parameters governing the production of entropy include the Re, the Pr, the Mach number (Ma), and the turbulent Schmidt and Pr numbers, which characterize the relative importance of the effects of inertial, viscous, thermal and compressibility [81,82]. At high Re typical of heat exchangers and combustion systems, turbulence intensifies, leading to steep gradients in velocity and temperature fields that dominate entropy generation. Accurate prediction of these gradients is critically dependent on the ability of the turbulence model to correctly resolve or parameterize subgrid-scale (SGS) dissipation and heat transfer [83,84].

The choice of turbulence modeling approach significantly affects the accuracy of entropy generation prediction. RANS models provide time-averaged solutions at low computational cost, but often fail to capture unsteady turbulent structures and localized entropy production in separated or swirling flows [85,86]. LES resolves large-scale turbulent motions while modeling smaller scales via SGS closures, offering improved accuracy for complex flows but demanding fine meshes near walls and in high-gradient regions [80,82]. Hybrid RANS-LES methods, such as Detached Eddy Simulation (DES) and Self-Adaptive Turbulence Eddy Simulation (SATES), combine the efficiency of RANS in boundary layers with the resolution of LES in separated regions, balancing cost and accuracy [87,88]. DNS, which resolves all turbulent scales without modeling, provides benchmark-quality entropy data but remains computationally prohibitive for high Re industrial flows [89,90]. Studies show that LES and hybrid methods substantially improve entropy generation predictions compared to RANS, particularly in capturing unsteady thermal and velocity fluctuations [79,91].

Mesh density and quality are critical determinants of the reliability of CFD entropy prediction. Insufficient grid resolution in boundary layers, shear layers, and reacting zones leads to under-resolved gradients, causing significant errors in the generation of computed entropy [80,90]. Adaptive mesh refinement (AMR) and grid-adaptive simulation (GAS) techniques dynamically adjust mesh resolution based on local flow features or error indicators, effectively resolving steep entropy gradients and reducing computational cost [92,93]. Entropy-based error indicators and combined entropy-output adaptive approaches guide mesh refinement to entropy-sensitive regions, enhancing solution precision [94,95]. Grid independence studies confirm that high-order numerical schemes and self-adaptive turbulence models reduce the sensitivity to mesh resolution, enabling accurate predictions on coarser grids [84,96]. However, mesh sensitivity remains a persistent challenge, especially near walls and in compressible or reacting flows, where numerical errors can be comparable to modeling errors and may partially cancel, complicating closure model development [90].

The main methodological limitations constrain the robustness and applicability of CFD-based entropy generation modeling. Numerical dissipation introduced by discretization schemes can artificially dampen turbulent fluctuations and alter entropy production, particularly on coarse meshes or with low-order methods [82,90]. Hybrid RANS-LES methods frequently encounter the “gray area” problem, where inconsistent energy transfer between modeled and resolved scales leads to underprediction of turbulence and entropy generation [97,98]. Near-wall turbulence modeling remains challenging, as wall-resolved LES demands prohibitively fine meshes at high Re, while wall-modeled LES introduces empirical uncertainties [99,100]. In reacting flows, turbulence–chemistry interaction and steep temperature gradients further complicate entropy prediction, requiring coupled adaptive combustion–turbulence models that remain computationally expensive and under-validated [83,101]. The lack of comprehensive validation against high-fidelity experimental or DNS data in complex geometries limits confidence in entropy generation predictions for industrial applications [86]. Additionally, uncertainty quantification and error estimation for entropy calculations are not yet standard practice, restricting the reliability of CFD results for design optimization [102,103]. These limitations underscore the need for integrated approaches that combine advanced turbulence models, adaptive meshing, high-order discretization, and entropy-stable solvers to achieve robust and accurate predictions of entropy generation in demanding turbulent thermal flows.

3.3. Finite Element Method

FEM provides an alternative numerical framework for entropy analysis, particularly suitable for conjugate heat transfer problems involving solid–fluid coupling and complex geometries [104,105]. FEM employs the same fundamental assumptions as CFD (Section 3.2) but discretizes entropy transport via weak formulations rather than control volumes. The weak formulation of entropy transport enables flexible discretization of irregular domains and straightforward implementation of boundary conditions. Similarly to CFD practice (Section 3.2), the generation of entropy is typically reconstructed from post-processed temperature and velocity fields rather than solving entropy transport equations directly. For steady-state problems, the FEM discretization of entropy generation follows from energy equation solutions. Accurate evaluation of entropy generation requires fine spatial resolution, particularly in thermal and velocity boundary layers, to correctly resolve the squared gradient terms in the following integral expressions:

where is the computational domain.

In conjugate heat transfer problems, may include both solid and fluid subdomains. In solid regions, only thermal entropy generation () is present, while in fluid domains, viscous dissipation also contributes via the term . The temperature field T and velocity field u are obtained from coupled thermal and momentum equations, then post-processed to extract entropy generation. This post-processing approach avoids the need to solve a separate entropy transport PDE, while still enabling accurate spatial and integral assessments of irreversibility in engineered systems. FEM offers advantages in handling material discontinuities, anisotropic properties, and moving boundaries compared to finite-volume CFD [104,105]. However, entropy calculation accuracy depends critically on element quality and refinement in high-gradient regions. Distorted elements near complex boundaries can introduce significant errors in gradient calculations, directly affecting entropy predictions [106].

FEM for entropy generation analysis in conduction-dominant and thermomechanical systems discretizes the governing partial differential equations into weak or variational forms. Entropy source terms, arising from thermal gradients and irreversible processes, are integrated into the energy equation and evaluated at quadrature points within each element. Standard Galerkin formulations employ polynomial basis functions to approximate temperature and heat flux fields, while mixed and multi-field FEM formulations treat temperature, heat flux, and stress as independent variables, improving convergence and physical fidelity in nonlinear scenarios [107,108]. High-order hp-finite element methods enable p-refinement alongside h-refinement, achieving fast convergence and oscillation-free solutions in complex heat conduction problems [107,108].

Handling entropy source terms requires robust numerical stabilization to address steep gradients and nonlinearities. Continuous interior penalty (CIP) and ghost penalty stabilization ensure numerical stability and accurate flux approximations at phase change interfaces in unfitted mesh approaches such as CutFEM [109]. Entropy viscosity methods add artificial diffusion proportional to local entropy residuals, ensuring entropy consistency and optimal convergence [110]. Discontinuous Galerkin formulations with entropy-based stabilization preserve stability and positivity of entropy, effectively capturing discontinuities in compressible systems [111]. These strategies mitigate oscillations but introduce computational overhead and require parameter tuning [110].

The mesh design critically influences the accuracy of entropy prediction. Adaptive mesh refinement (AMR) using hierarchical B-splines and multilevel schemes dynamically adjusts resolution based on error indicators, resolving steep entropy gradients while reducing computational cost by 78–99% in phase-field fracture simulations [112,113]. Anisotropic mesh adaptation guided by level-set interface capture improves interface representation in conjugate heat transfer problems [114]. Polygonal finite elements demonstrate superconvergence and mesh flexibility without explicit refinement [115,116]. However, mesh sensitivity persists in transient and nonlinear problems, where grid quality impacts entropy localization and stability [112,113].

Complex boundary conditions, including phase change and moving boundaries, are addressed through implicit interface tracking via level-set methods combined with ghost penalty stabilization, achieving optimal convergence without conforming meshes [109]. Phase-field approaches coupled with Allen–Cahn formulations model convective phase change with moving interfaces, preserving the maximum bound principles [117]. Immersed boundary and isogeometric methods with Nitsche’s weak enforcement facilitate multi-material coupling, reducing meshing complexity [118,119]. Capturing sharp interface dynamics without numerical diffusion requires fine discretization, increasing computational demands [109,120].

The main limitations constrain the applicability of FEM. High-order and mixed formulations increase degrees of freedom and complexity, requiring sophisticated solvers [107,108]. Stabilization techniques introduce parameters and overhead, with effectiveness demonstrated on limited benchmarks [110]. Adaptive refinement relies on problem-specific error estimators that may not be generalized [112,113]. Phase change models struggle with sharp interface capture and lack experimental validation [109,120]. Nonlinear temperature-dependent properties cause convergence difficulties with few standardized benchmarks [121,122].

3.4. Lattice Boltzmann Method

The LBM has emerged as a competitive alternative to conventional CFD for entropy analysis, particularly for complex geometries and multiphysics coupling [123,124,125]. The LBM solves the discrete Boltzmann equation on a cartesian lattice:

where is the particle distribution function in the discrete velocity direction at position and time ; is the discrete lattice velocity vector in direction ; is the time step; is the relaxation time controlling viscous effects; and is the local equilibrium distribution function toward which relaxes.

Macroscopic properties (density, velocity, temperature) are computed from distribution function moments. The entropy generation is then calculated from the reconstructed velocity and temperature gradients using standard formulations [124,125]. The LBM offers several advantages for entropy analysis: straightforward implementation of complex boundary conditions, natural parallelization in modern computing architectures, and inherent coupling of thermal and flow physics [123]. However, compressibility effects are limited to low Ma, and turbulence modeling remains less mature than conventional CFD.

Recent algorithmic developments in LBM formulations for entropy generation modeling have focused on enhancing numerical stability through advanced collision operators. Multiple-relaxation-time (MRT) schemes demonstrate superior stability over single-relaxation-time (SRT) BGK models, particularly for non-Newtonian fluids and complex flow regimes [126,127,128]. Entropic LBM models enforce entropy constraints in the collision step, guaranteeing unconditional stability by satisfying the H-theorem and eliminating spurious oscillations [129]. The term ‘entropic’ in entropic lattice Boltzmann methods refers to a kinetic H-function (analogous to Boltzmann’s H-theorem from statistical mechanics) used for numerical stability. While mathematically related through statistical mechanics foundations, the entropic LBM collision operator ensures non-negative entropy production at the kinetic scale, which indirectly guarantees thermodynamic consistency in macroscopic entropy generation calculations [129].

Thermal coupling approaches have advanced significantly for non-isothermal and conjugate heat transfer scenarios. Multi-distribution function approaches enable an accurate representation of temperature-dependent properties and Pr variations critical for entropy quantification [130]. Thermal LBM schemes that incorporate temperature-dependent viscosity and conductivity capture nonlinear effects in flows of nanofluid and porous media [131,132]. Conjugate heat transfer modeling in partitioned media employs coupled LBM formulations for fluid and solid domains, enabling detailed entropy mapping at interfaces [133,134]. The effects of thermal radiation are integrated using finite difference coupling, with emissivity that strongly affects the components of entropy [64]. Two-phase LBM models for nanofluids under magnetic fields capture nonequilibrium effects, improving entropy predictions [135].

Boundary condition treatment advances include refined slip flow modeling and wall injection techniques. Slip boundary conditions incorporating Knudsen number (Kn) effects capture rarefaction and velocity slip impacts on entropy generation in microchannels [134,136,137]. Curved boundary treatments using immersed boundary methods (IBM) facilitate entropy analysis in complex geometries without conforming meshes [138,139].

Entropic collision operators ensure non-negative entropy production at each lattice node, enhancing convergence in high Ra and Hartmann number (Ha) flows [129]. The MRT-LBM schemes decouple relaxation times for different hydrodynamic modes, improving stability in shear-dominated and magnetohydrodynamic flows [126,127]. Microstructure-sensitive models incorporating the Darcy expanded Brinkman–Forchheimer relations capture flow resistance in porous media, with the generation of entropies dependent on porosity and Darcy number (Da) [131,140].

The LBM effectively captures slip flow regimes and wall injection effects in microchannels, with Knudsen and Re numbers that critically influence the generation of entropy [134,141]. In porous media, Da, porosity, and nanoparticle volume fraction strongly modulate entropy generation [131,132]. Rarefied gas flows in microcavities exhibit slip-dominated entropy generation, accurately modeled with Knudsen-dependent boundary conditions [142].

3.5. Comparative Analysis and Method Selection

Table 3 summarizes the technical capabilities and ranges of validated parameters for each discretization method based on verified literature data, providing a foundation for understanding method strengths and limitations before application-specific selection.

Table 3.

Technical Capabilities and Validated Ranges of Discretization Methods for Entropy Analysis.

The selection of numerical methods for the modeling of entropy generation requires a systematic evaluation of the accuracy, computational cost, scalability, and suitability of the entropy mechanism. Finite volume methods (FVM) dominate industrial CFD applications through conservation properties and geometric flexibility, accurately predicting thermal and viscous entropy in complex geometries, though accuracy depends critically on turbulence model selection [156,157]. FEM provides competitive accuracy with superior capability for irregular domains and multiphysics coupling, demonstrated by fractional-order FEM capturing thermo-magnetic entropy in porous enclosures [158]. High-order finite difference schemes achieve superior spatial accuracy for three-dimensional convection entropy analysis while maintaining computational efficiency [159]. Entropy-stable schemes—discontinuous Galerkin (DG) with Direct Enforcement of Entropy Balance (DEEB) and nonlinearly stable flux reconstruction (NSFR)—guarantee discrete adherence to the second law, providing provable nonlinear stability in compressible flows through entropy variables and entropy-conserving fluxes [160,161,162]. The LBM offers advantages for microscale entropy modeling where kinetic-scale physics and complex boundary conditions significantly affect entropy generation [135,163].

Table 4 summarizes comparative performance metrics. High-order entropy-stable schemes incur increased complexity, but enable larger stable time steps [162]. FVM and FEM exhibit moderate computational demands suitable for engineering workflows; the LBM demonstrates favorable parallel scalability for microscale problems [164]. The Response Surface Methodology (RSM) dramatically reduces computational expense, achieving design space exploration with 10–20 simulations [165,166]. Physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) and artificial neural networks (ANNs) enable rapid prediction of entropy, reducing grid requirements by 50% while maintaining 5% accuracy [167,168,169].

Table 4.

Comparative Performance of Numerical Methods for Entropy Generation Modeling.

Based on technical capabilities (Table 3) and performance metrics (Table 4), Table 5 provides application-specific method selection guidelines. These recommendations are based on systematic evaluation across five criteria derived from a comparative literature analysis: (1) computational cost assessed through relative CPU time for representative benchmarks [156,157,161,162]; (2) accuracy evaluated via entropy generation prediction error against validated experimental and DNS data [135,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163]; (3) physics capability considering alignment with dominant entropy mechanisms—FVM/FEM for thermal–viscous processes, LBM for rarefaction effects in microscale systems [135,163], and entropy-stable schemes for thermodynamic consistency in compressible flows [161,162]; (4) scalability examining parallel efficiency and mesh size limitations across different computational architectures [164]; and (5) implementation maturity reflecting commercial software availability, validation database extent, and community support [156,157]. Each application class represents optimal trade-offs: turbulent heat exchangers benefit from mature FVM turbulence models [156,157], microscale systems leverage the LBM’s kinetic physics advantages [163], and compressible flows require entropy-stable schemes for guaranteed consistency [161,162].

Table 5.

Method Selection Guidelines for Representative Entropy Analysis Applications.

Computational resources fundamentally constrain selection. High-performance computing enables high-order entropy-stable schemes that provide maximum fidelity at significant expense [162]. Resource-limited scenarios require efficient formulations—compact schemes, algebraic fluxes, or machine learning surrogates [159,160]. Adaptive mesh refinement guided by entropy-based error indicators concentrates computational effort in high-entropy-generation regions [94].

4. Computational Approaches to Entropy-Based System Optimization

This section reviews computational strategies for minimizing entropy generation to enhance thermal system efficiency. It covers foundational methods like EGM, constructal theory, and multi-objective optimization, emphasizing thermodynamic trade-offs and practical constraints. Advanced approaches integrate artificial intelligence and machine learning to accelerate optimization and improve predictive accuracy, while case studies demonstrate entropy-based performance gains in heat exchangers, thermal management, and renewable energy systems.

4.1. Entropy Generation Minimization Methods

EGM provides a thermodynamic framework for reducing irreversibilities in thermal and energy systems by quantifying and minimizing entropy production arising from heat transfer, fluid friction, and other dissipative processes. The mathematical foundation is based on the Gouy–Stodola theorem, which relates entropy generation to exergy destruction, establishing that minimizing total entropy generation maximizes system efficiency and available work [176,177]. EGM formulations integrate local entropy generation rates with global optimization constraints, balancing thermal performance objectives against irreversibility penalties through multi-objective frameworks [178,179]. Constructional theory extends EGM by optimizing geometric configurations to minimize entropy production in heat and mass transfer systems, demonstrated through optimal spacing and shape designs in heat-generating disks and flow architectures [180]. Alternative thermodynamic formulations, including generalized entransy dissipation, offer competing optimization criteria that coincide with EGM under specific boundary conditions but diverge in systems with non-uniform temperature distributions [181].

Key assumptions underlying EGM include steady-state operation, local thermodynamic equilibrium, and idealized boundary conditions, which may not hold in transient or highly non-equilibrium systems [176]. Case studies reveal that EGM effectively predicts optimal operating conditions in heat exchangers, solar thermal systems, and thermoelectric generators when thermal and viscous irreversibilities dominate, with entropy-minimized designs achieving 15–30% efficiency improvements over baseline configurations [177,178,182]. However, EGM can misalign with actual system efficiency in scenarios involving significant transient effects, complex multiphysics coupling (e.g., electromagnetic losses in superconducting cables), or when pumping power penalties outweigh heat transfer gains, particularly in nanofluid applications [183,184]. Table 6 summarizes EGM methodologies, their assumptions, and alignment with system performance across representative applications.

Table 6.

EGM Methodologies, Assumptions, and Performance Alignment.

Computational and multi-objective trade-offs in EGM applications involve balancing heat transfer enhancement with pressure drop penalties, material costs, and manufacturing constraints [182]. Multi-objective genetic algorithms identify Pareto-optimal designs simultaneously minimizing entropy generation and maximizing heat transfer effectiveness, revealing that optimal configurations often differ from single-objective optima [178,179]. Computational expense scales with problem dimensionality and fidelity; surrogate modeling and response surface methods reduce evaluation costs but introduce approximation errors [178]. EGM applied to supercritical CO2-cooled microchannels demonstrates that entropy-minimized geometries achieve 20% reduction in total irreversibility while maintaining thermal performance, though fabrication tolerances constrain practical implementation [185]. Phase change material thermal storage systems optimized via EGM exhibit configuration-dependent entropy generation, with triplex tube designs reducing irreversibility by 25% compared to conventional geometries [186]. Solar air heaters with conic-curve profile ribs optimized through EGM achieve 18% efficiency improvement, though entropy minimization does not universally correlate with maximum thermal efficiency due to competing viscous and thermal irreversibilities [187]. CFD-based entropy generation analysis of Linear Fresnel Reflector systems reveals that conduction dominates total irreversibility (97.4%), with viscous dissipation and radiation contributing the remainder [188].

Port-Hamiltonian formulations provide alternative frameworks for EGM by embedding entropy production into energy-conserving structures, allowing systematic controller design for thermal systems [189]. Low-dissipation heat engines exhibit energetic self-optimization induced by stability constraints, suggesting that EGM naturally emerges from dynamic stability requirements rather than explicit optimization [189]. EGM applied to concentrated solar power (CSP) technologies using molten salt heat transfer fluids (NaCl/KCl/MgCl2) identifies optimal flow rates and heat exchanger configurations that reduce irreversibility by 30%, though material compatibility and high-temperature stability remain practical constraints [190]. These findings underscore that while EGM provides robust theoretical guidance for thermal system optimization, practical implementation requires careful consideration of assumptions, validation against experimental data, and integration of multi-objective constraints reflecting real-world operational and economic considerations.

4.2. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Entropy Optimization

This section examines the use of artificial intelligence and machine learning to minimize the generation of thermodynamic entropy in energy systems. AI and ML accelerate thermodynamic optimization by replacing computationally intensive CFD analyses with surrogate models such as physics-informed or artificial neural networks that predict . Throughout this section, “entropy” in optimization contexts refers to thermodynamic entropy generation, while “entropy” in algorithmic contexts denotes information entropy within ML methods.

The AI and machine learning methods applied to EGM leverage physics-informed architectures, reinforcement learning, and Bayesian frameworks to enhance thermodynamic consistency and predictive accuracy. Physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) embed thermodynamic partial differential equations and variational principles directly into loss functions. This enables entropy minimization in channel flows with reduced grid resolution requirements and computational cost compared to classical CFD solvers [169]. Port-metriplectic neural networks and GENERIC formalism-based latent space models enforce energy conservation and non-negative entropy production by construction, guaranteeing adherence to the second law while learning system dynamics from data [191,192]. Variational Onsager Neural Networks (VONNs) employ thermodynamics-based variational learning strategies for non-equilibrium PDEs, ensuring robust entropy production predictions across phase transformations and viscoelastic systems [193]. Deep reinforcement learning identifies optimal thermodynamic paths minimizing entropy production in quantum and classical systems through policy optimization under thermodynamic constraints, demonstrating superior efficiency compared to traditional trajectory optimization methods [194].

Performance comparisons reveal that thermodynamically informed models outperform purely data-driven approaches in predictive accuracy and generalization. Hybrid deep neural network-Bayesian frameworks achieve superior accuracy and interpretability in energy dissipation modeling across quantum, fluid dynamics, and climate systems compared to standalone neural networks, although at moderate computational cost [195]. Graph neural networks informed locally by thermodynamics demonstrate high accuracy and strong generalization across solid and fluid mechanics while maintaining computational efficiency through preservation of local structure [196]. However, assembling global Poisson and dissipation matrices in metriplectic formulations disrupts local network structures, limiting scalability to large systems [196]. Entropy-driven deep reinforcement learning for HVAC optimization achieves up to 39% energy savings with improved algorithmic efficiency compared to conventional control strategies, though training remains computationally intensive [8]. Table 7 compares AI/ML approaches for entropy optimization, highlighting key features, performance characteristics, and limitations.

Table 7.

Comparison of AI/ML Approaches for Entropy Optimization.

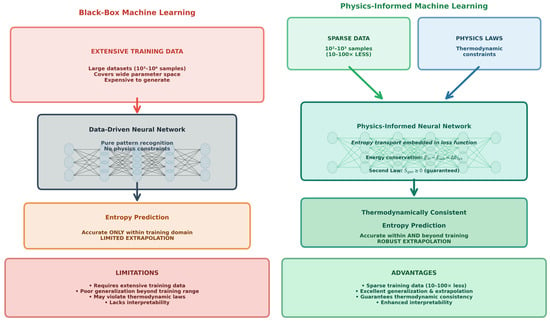

The distinction between data-driven and physics-informed neural networks is critical in entropy modeling. Figure 2 contrasts these two paradigms through a schematic comparison. Black-box machine learning (left panel) requires extensive training datasets (103–106 samples) covering wide parameter spaces. These data-driven neural networks perform pure pattern recognition without physics constraints, achieving accurate entropy predictions only within the training domain but exhibiting limited extrapolation capability beyond training ranges. They may violate thermodynamic laws and lack interpretability. Physics-informed machine learning (right panel) operates with sparse data (102–103 samples, representing 10–100× reduction) by embedding thermodynamic constraints directly into the neural network architecture. Specifically, entropy transport equations, energy conservation, and the second law inequality (Ṡ(gen) ≥ 0) are guaranteed by construction. This approach achieves thermodynamically consistent entropy generation predictions with robust extrapolation capability, maintaining accuracy both within and beyond training domains. The trade-off involves increased implementation complexity, though substantial data reduction and guaranteed physical consistency make physics-informed approaches particularly suitable for entropy optimization applications.

Figure 2.

Schematic comparison between black-box ML versus physics-informed ML for entropy prediction.

The interpretability of the model and the data requirements represents critical challenges. Physics-informed models improve interpretability by embedding known thermodynamic laws, but their complexity increases the implementation difficulty and computational overhead [202]. Purely data-driven models without physics constraints risk overfitting and generating physically inconsistent predictions, particularly when extrapolating beyond training data [201]. Inductive biases based on thermodynamics reduce data requirements by incorporating structural knowledge; single-generator versus double-generator formulations show improved accuracy with fewer training samples when physical principles are embedded [202]. Bayesian physics-informed neural networks provide uncertainty quantification for phonon transport problems, enabling robust reconstruction with sparse and noisy data compared to deterministic PINNs [198]. However, Bayesian methods incur higher training complexity and computational expense, limiting scalability to high-dimensional multi-physics problems [198].

The generalization capability varies significantly between methods. Thermodynamics-informed latent space dynamics identification (tLaSDI) demonstrates robust extrapolation across thermodynamic regimes by embedding first and second laws via the GENERIC formalism, outperforming purely data-driven latent models [191]. Graph neural networks with local metriplectic biases generalize effectively across solid and fluid mechanics applications without retraining [196]. Conversely, surrogate neural networks for multi-generation system optimization achieve high predictive accuracy (R2 > 0.98) within training domains but exhibit degraded performance when applied to systems with significantly different configurations or operating conditions [203]. Adaptive sampling strategies guided by energy dissipation rates improve PINN accuracy six times over traditional methods in Allen–Cahn phase field models, demonstrating that physics-informed sampling enhances generalization [204].

Hybrid physics-informed models balance flexibility and thermodynamic fidelity. Neural ODEs with irreversible port-Hamiltonian system frameworks provide physically consistent predictions for the building of thermodynamics and gas-piston systems while maintaining modular flexibility [205]. Variational Neural Networks for Observable Thermodynamics (V-NOTS) guarantee non-decreasing entropy evolution with low parameter counts, achieving data-efficient phase space predictions in dissipative dynamical systems [206]. Multi-branch PINN deep operator networks combine physics-informed constraints with operator learning, allowing rapid thermal simulations orders of magnitude faster than numerical solvers without retraining for variable parameters [207].

AI/ML methods clearly improve optimization results when thermodynamic constraints dominate and the training data are representative. Entropy-driven DRL for HVAC achieves substantial energy savings by learning control policies that balance thermal comfort and entropy generation [8]. PINNs accelerate the inverse design of heat exchangers by parameterizing the geometry and operating inputs, enabling Pareto-optimal design search in real-time compared to iterative CFD-based optimization [208]. However, AI/ML approaches may fail or overfit when: (1) training data are insufficient or non-representative, leading to poor generalization [204]; (2) physics constraints are inadequately enforced, resulting in thermodynamically inconsistent predictions [201]; (3) systems exhibit highly nonlinear or chaotic dynamics beyond model capacity; (4) computational resources limit hyperparameter tuning or ensemble training [203]. Reinforcement learning methods struggle with interpretability and stability in stochastic environments, potentially converging to suboptimal policies despite high training costs [194]. These limitations underscore the necessity of integrating domain knowledge, validating across diverse operating conditions, and employing uncertainty quantification to ensure reliable entropy optimization in practical thermal and energy systems.

4.3. Case Studies in Entropy-Based Optimization

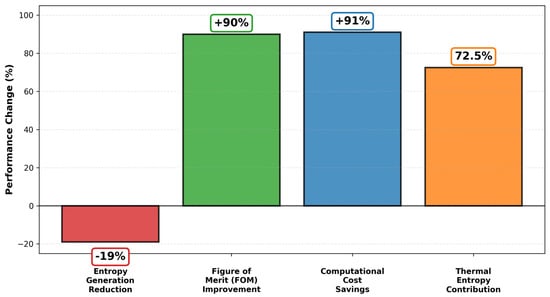

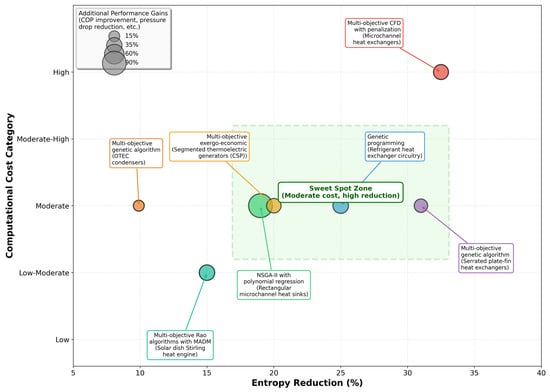

Entropy-based optimization techniques have been systematically applied in heat exchangers, thermal management systems, and renewable energy technologies, demonstrating quantifiable improvements in thermodynamic performance. In heat exchangers, multi-objective optimization frameworks integrating EGM with thermal–hydraulic metrics achieve substantial performance gains. Topology optimization of discontinuous fin-based microchannel heat exchangers using multi-objective CFD with penalization factors yields 30–35% reductions in both entropy generation and pressure drop while maintaining thermal gain [209]. Genetic programming applied to refrigerant heat exchanger circuitry minimizes entropy generation while maximizing coefficient of performance (COP), confirming that reduced friction and heat transfer irreversibility correlate with improved COP [199]. NSGA-II optimization of rectangular microchannel heat sinks achieves up to 19% entropy reduction and 90% improvement in figure of merit through simultaneous thermal and hydraulic optimization [210]. Figure 3 presents quantitative performance improvements from this methodology. The optimization approach couples the Response Surface Methodology (RSM) with the NSGA-II multi-objective genetic algorithm, targeting simultaneous minimization of entropy generation, pressure drop, and thermal resistance [210]. Performance improvements include 19% entropy reduction, 90% figure of merit enhancement (FOM defined as (Rth·ΔP)−1), and 91% computational cost savings via RSM surrogate modeling compared to full factorial design of experiments [165,210]. Entropy generation analysis reveals thermal entropy dominance (70–75% of total), justifying prioritization of heat transfer enhancement strategies (e.g., increased channel depth, optimized fin geometry) over friction reduction in microchannel design optimization [210]. RSM-coupled NSGA-II enables rapid design space exploration with 15–25 CFD evaluations versus 200+ for full factorial approaches, while maintaining typical validation errors of 3–12% for thermal resistance and pressure drop predictions [165,211].

Figure 3.

Verified performance improvements from microchannel heat sink optimization using the RSM-coupled NSGA-II methodology (Figure prepared using data and information reported in the cited publications [165,210]).

Multi-objective genetic algorithms applied to serrated plate-fin heat exchangers demonstrate 31% entropy reduction with improved heat transfer factors, revealing high sensitivity of entropy generation to structural parameters [212].