Abstract

Efficient and harmless disposal of multi-source organic liquid waste is a key requirement in current environmental protection. Herein, we employ high-temperature tube furnaces, small-scale rotary kilns, and industrial rotary kilns as test platforms, focusing on high-temperature conditions (>1200 °C) in existing industrial kilns. Systematic studies on combustion characteristics, pollutant emission laws, and disposal adaptability were conducted. We aim to clarify the intrinsic correlations between co-incineration behaviors, pollutant generation, and disposal feasibility for the co-incineration of multi-source organic liquid waste in cement kilns. The results demonstrate significant interaction effects during the co-incineration of multi-source organic liquids, which reduces combustion energy consumption and improves operational safety. The “micro-explosion” effect generated by high-temperature incineration is the key to regulating pollutant emissions, with CO emissions of only 6.71%. Tests on small and industrial rotary kilns indicate that co-disposal of liquid waste in cement kilns does not affect the stable operation of the kiln or the quality of the cement clinker, and pollutant emissions meet industrial standards. This work can provide a scientific basis and technical support for large-scale, efficient, and clean disposal of organic liquid waste in industrial cement kilns.

1. Introduction

With the rapid development of urbanization and industrialization, the production of domestic sewage and industrial wastewater is increasing. In 2021, polluted wastewater discharge reached 29.68 million tons, with organic liquid waste being the predominant pollutant, accounting for approximately 85.3% [1]. Sources of organic waste liquids include petrochemical waste, medical waste, urban sewage, pesticide waste, and landfill leachate. These liquids contain a wide range of suspended, colloidal, and dissolved organic substances, most notably aromatic and heterocyclic compounds, as well as inorganic salts, heavy metals, and pathogenic microorganisms [2]. If untreated and directly discharged, organic waste liquids pose a significant threat to both the ecological environment and human health [3]. The proliferation of liquid waste will severely pollute water, soil, and the air environments, endanger human health, and trigger work safety risks, including fires and explosions [4,5,6]. Furthermore, higher organic matter content in waste liquids contributes to higher calorific values, and when this value exceeds 10,500 kJ/kg, spontaneous combustion can occur without the need for additional fuel [7,8]. Therefore, incineration of organic liquid waste can help to achieve harmless disposal and utilize its own heat.

Incineration is a simple and efficient method that oxidizes and decomposes macromolecular organic matter in waste liquid into small, harmless molecules such as water and carbon dioxide under high-temperature and oxygenated conditions. Its organic matter removal rate can reach up to 99.9% [9]. Under air and nitrogen atmospheres, the pollutant emission characteristics of high-concentration organic liquid waste within a temperature range of 500–900 °C were investigated. It was found that NOx emissions are predominantly fuel-type and prompt-type. Moreover, the higher the temperature, the more conducive it is to the complete combustion of organic matter [10,11,12]. It has been observed that at 500 °C, biodiesel/high calorific value liquid blended droplets undergo micro-explosions due to the synergistic effect of multi-boiling-point components and the high moisture in biodiesel, and these micro-explosions can enhance combustion efficiency [13,14,15]. Rapeseed oil/water droplets were studied in 1450 K propane/butane flames. It was found that a micro-explosion is more likely to occur at a higher temperature, which provides a methodological reference for research on high-temperature micro-explosions in industrial kilns [16,17]. Experiments and modeling confirmed that the micro-explosion of emulsified fuel droplets effectively promotes CO emission reduction. Their effect on NOx control, however, is limited [18,19]. Particle movement during co-incineration in rotary kilns was studied to predict combustion interactions. Temperature is the core regulatory factor determining the disposal efficiency and harmlessness of organic liquid waste incineration [14,20,21,22]. The current relevant research and engineering practices for organic liquid waste incineration disposal still rely on specialized incinerators. In some scenarios, targeted construction of new liquid waste incineration disposal devices is required. Such specialized equipment not only has high energy consumption but also faces the problems of high initial investment and high operating costs [21]. Existing industrial kilns, such as cement rotary kilns, can naturally form a high-temperature environment of 1200–1600 °C during regular production. This fully meets the core requirement for the harmless incineration of organic liquid waste. However, most existing research on organic liquid waste incineration focuses on moderate- and low-temperature conditions below 1000 °C. There remains a gap in the reaction mechanism under industrial-scale high-temperature environments above 1200 °C. In particular, the intrinsic correlations between micro-explosions, the interaction of multi-source organic liquids in waste co-incineration, and pollutant formation are not yet clear. This results in a lack of systematic understanding of the complete “combustion–micro-explosion–pollutant formation” process of organic liquid waste in the high-temperature environment of industrial kilns. Research conclusions under moderate- and low-temperature conditions cannot be directly migrated to industrial-scale high-temperature disposal scenarios. This is due to differences in core operating conditions, such as temperature fields, causing a lack of theoretical support for the engineering application of the technology.

This study aims to achieve the volume reduction, harmlessness, and resource utilization of multi-source organic liquid waste as its core goals. We adopt a research flow from basic laboratory research, namely small-scale rotary kiln tests, to industrial verification to systematically investigate the interaction mechanism of co-incineration of multi-source liquid waste and the feasibility of co-disposal of liquid waste in cement kilns. It is expected to provide a comprehensive theoretical basis and technical support for the combustion mechanisms of organic liquid waste, ensuring the stable operation of industrial kilns and controlling pollutant emissions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Selection and Physicochemical Properties of Organic Waste Liquid

Waste engine oil (WEO) and waste organic solvent (WOS) were selected as research objects. Due to the complexity and non-uniformity of waste liquid, the following liquids were selected to replace the actual waste liquids in this study based on the characteristics of these kinds of waste liquid:

(1) New engine oil was used to simulate WEO [23]; (2) a mixture of 47.5% methanol + 47.5% ethanol + 5% thiourea was used to simulate WOS [24]. The basic physical and chemical properties of the two typical organic waste liquids are shown in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

Elemental analysis and moisture content of organic liquid waste (%).

Table 2.

Other physicochemical properties of organic waste liquid.

2.1.2. The Configuration of Emulsion

The oil-in-water (W/O) emulsion was prepared by combining “WEO + WOS + W/O emulsifier” according to a certain mixing ratio. Span 80 was selected as the W/O emulsifier, and the amount added was 1/10 of the mass of dispersed phase components (i.e., WOS). The mass-mixing ratio of the W/O emulsion is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Mass-mixing ratio of emulsion (%).

The preparation process of the emulsion is as follows: weigh a certain amount of waste liquid and emulsifier in proportion to the beaker, then stir at a high speed of 5000 r/min in a high shear emulsifier for 5 min, and then stir at 2000 r/min for 3 min. The required emulsion should be prepared and sealed in 0.5 h before each test.

2.2. Test Device and Operation Process

2.2.1. Thermogravimetric Differential Scanning Calorimeter

A thermogravimetric differential scanning calorimeter (TG-DSC) was used to study the TG characteristics and thermal stability of materials. The Mettler Toledo TG/DSC1 (METTLER TOLEDO, Zurich, Switzerland) was used to test the TG and absorption/release characteristics of organic waste liquid.

2.2.2. Tube Furnace Incineration Test Bench

The high-temperature tubular furnace test bench that was used to study pollutant emissions from liquid waste incineration consisted of three parts: gas–liquid inlet, combustion zone, and tail gas treatment. The heating zone length was 1500 mm, and the diameter was 90 mm. The maximum temperature was 1600 °C. The flue gas analyzer (ECOM, Iserlohn, Germany) was used to enable the online monitoring of O2, CO2, CO, NO, NO2, and SO2 concentrations.

2.2.3. Internal Heating Small-Scale Rotary Kiln Test Bench

An internally heated small rotary kiln with dimensions of φ 0.8 × 2 m served for small-scale pilot tests of co-disposal of waste oil in cement kilns. It consisted of a kiln shell, transmission and support mechanism, combustion system, measurement and control system, and other components. Its maximum operating temperature can reach 1600 °C. Four liquid waste feeding conditions were set in the experiment: no liquid waste feeding (CT-1), feeding from 10 to 20 min (CT-2), feeding from 5 to 25 min (CT-3), and feeding from 5 to 35 min (CT-4).

The mineral and chemical compositions of the samples were determined using an X-ray diffraction spectrometer (PANALYTICAL AERIS, Malvern Panalytical, Almelo, The Netherlands) and an X-ray fluorescence spectrometer (SPECTRO XEPOS, SPECTRO Analytical, Kleve, Germany), respectively.

2.2.4. Experiment on Co-Disposal of Waste Oil in Industrial Cement Rotary Kilns

To verify the engineering feasibility and stability of the cement kiln co-disposal technology for waste oil, large-scale experiments were conducted at a cement plant in Shandong Province. The experiment adopted a 4000 t/d new dry-process rotary kiln production line with kiln parameters of φ 4.8 × 74 m. The treated material was a mixed solution of various waste oils, including waste lubricating oil, waste engine oil, waste hydraulic oil, and landfill leachate. A closed-loop monitoring system of “feeding rate—kiln condition—clinker quality” was established by tracking real-time kiln operation parameters via the online monitoring system and conducting regular clinker quality tests. Additionally, the DFS SN03156M HRGC-HRMS system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was used to measure dioxins.

2.3. Experimental Method

The theoretical value calculation method is as follows: assuming no interactive reaction during incineration, the experimental values and mixing ratios of the organic waste liquids are summed using a linear weighted sum, as shown in Equation (1):

Among these, ycal represents the theoretically calculated value, yexp1, yexp2, and yexp3 represent the experimental values of the separate incineration of two organic waste liquids, and x1, x2, and x3 represent the mixing ratio of the two kinds of organic waste liquid.

To clarify the magnitude of the interaction during emulsion liquid incineration, the interaction value is calculated as the difference between the theoretical and experimental values, as shown in Equation (2):

In the formula, zsyn represents the interactive value, ycal represents the theoretical value, and yexp represents the experimental value of emulsion incineration. When zsyn is positive, it indicates a beneficial synergistic effect, and when zsyn is negative, it indicates a harmful synergistic effect.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Experiment on Interaction in the Co-Incineration of Multi-Source Waste Liquids

3.1.1. Combustion Characteristics of Single Waste Liquid and Physicochemical Properties of Its Emulsions

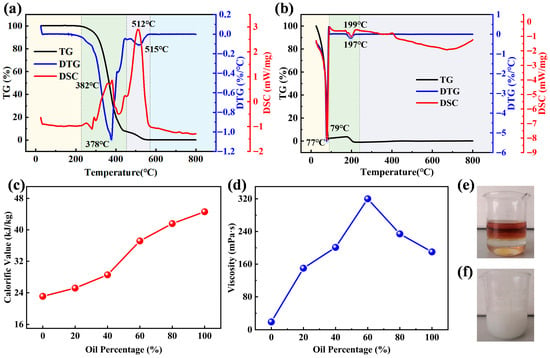

The thermogravimetric differential heat curves of two typical organic waste liquids are shown in Figure 1a,b. Different organic waste liquids have substantial differences in TG characteristics, heat-absorption and heat-release characteristics, and combustion characteristics at different temperature ranges. The TG characteristic curve of the two waste liquids shows that the WEO weight loss process consists of four stages: (1) drying; (2) hydrocarbon pyrolysis and combustion; (3) residual carbon pyrolysis and combustion; (4) burnout. The WOS weight loss process consists of three stages: (1) volatilization; (2) salt precipitation; (3) burnout [25].

Figure 1.

TG-DTG-DSC curves of (a) WEO, and (b) WOS. (c) Calorific value variation of emulsions with different oil contents. (d) Viscosity variation of emulsions with different oil contents. (e) Before emulsification, and (f) after emulsification. (The background colors indicate different weight loss stages, and the circles indicate the corresponding peak values of each weight loss peak).

The maximum weight loss rate of WEO occurs at 378 °C in its second stage, while for WOS, it occurs at 77 °C in the first stage. The steep weight loss peak of WEO indicates a vigorous combustion reaction in this temperature range [26]. WOS has a low boiling point and evaporates quickly. It volatilizes before reaching its ignition temperature. The second largest weight loss peak of DTG of WEO (515 °C) occurs in the third stage, which is mainly the decomposition and combustion of some fixed carbon and organic impurities. The second largest peaks for WOS (197 °C) in the second stage are attributed to salt precipitation and combustion [27].

The DSC heat flow curves of the two waste liquids show that WEO’s first exothermic peak appears at approximately 382 °C with an intensity of 0.832 mW/mg. This peak primarily results from hydrocarbon combustion. WEO’s maximum exothermic peak occurs at 512 °C with an intensity of 2.904 mW/mg. It originates from solid residual carbon that has a high calorific value [10]. WOS absorbs significant heat rapidly due to its fast evaporation rate. Its heat absorption peak thus appears near 79 °C with a maximum intensity of −8.098 mW/mg.

The calorific value increases linearly with the rise in oil content, as shown in Figure 1c. This is because WEO possesses a high calorific value. It provides a foundation for energy supply in subsequent co-incineration. The viscosity first increases and then decreases as shown in Figure 1d. It reaches the maximum value at 60% oil content. This change is associated with the emulsion’s phase transition from O/W to W/O [28]. It also provides guidance for optimizing emulsion fluidity in subsequent incineration.

3.1.2. Combustion Characteristics of Multi-Source Waste Liquid Collaborative Incineration

(1) Thermogravimetric characterization of mixtures

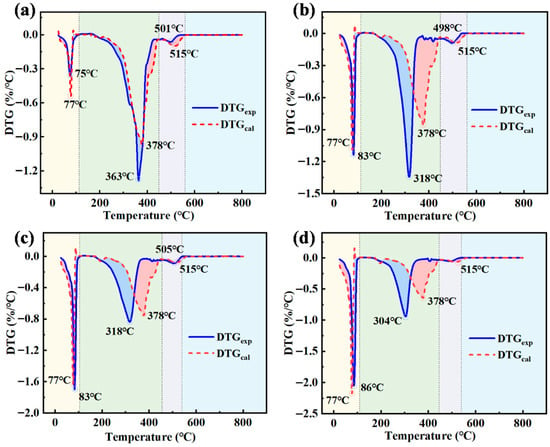

During the co-incineration of WEO and WOS, the weight loss process consists of three stages, as shown in Figure 2. Take BE-1 emulsion as an example. The first stage, from 25 °C to 112 °C, mainly involves the evaporation of WOS components, methanol, and ethanol. The second stage, from 113 °C to 449 °C, focuses on the vaporization and combustion of hydrocarbon substances in WEO. The third stage, from 450 °C to 560 °C, primarily results from the decomposition or combustion of residual carbon and salt in WEO [29].

Figure 2.

Comparison of DTGexp and DTGcal for collaborative incineration. (a) BE-1, (b) BE-2, (c) BE-3, and (d) BE-4. (The background colors indicate different weight loss stages, and the circles indicate the corresponding peak values of each weight loss peak).

With the mixing ratio of WEO to WOS changing from 9:1 to 6:4, the minimum DTGexp value in the first stage increases from −0.36 to −2.05%/°C. In contrast, the minimum DTGexp value in the second stage decreases from −1.28 to −0.94%/°C. This trend comes from two factors: higher WOS proportion accelerates the evaporation of methanol and ethanol per unit time, and reduces the content of hydrocarbons, residual carbon, and salts in the emulsion [30].

In the second weight loss stage, the temperature of the minimum DTGexp drops from 363 to 304 °C. This indicates that interaction becomes stronger gradually, which lowers the evaporation temperature of hydrocarbons. The lower temperature reduces energy consumption for waste liquid incineration and makes ignition easier [31,32]. The minimum DTGexp values of emulsions consistently exceed those of DTGcal, indicating that interaction enhances hydrocarbon combustion.

In the third weight loss stage, interaction either inhibits combustion or shifts from promotion to inhibition. A possible reason is that heat from organic solvent combustion promotes the endothermic reactions of the oil phase. In addition, interaction accelerates the decomposition and combustion of residual carbon and salts, which reduces the thermal burnout rate of incineration residues [33].

The blue areas represent the promotion of weight loss by interaction, while the red areas represent inhibition. As the WOS proportion increases, the temperature corresponding to the minimum DTGexp rises from 75 to 86 °C. However, the temperature of the minimum DTGcal remains at 77 °C. This may be because the solvent components in the W/O emulsion are wrapped by the oil phase. This wrapping reduces the heat transfer rate of the solvent and increases its evaporation temperature. Higher evaporation temperatures of methanol and ethanol reduce the risk of backfire and improve incineration safety [33].

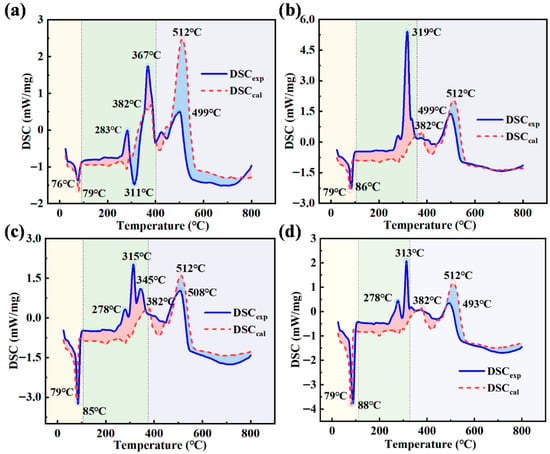

(2) Heat absorption and release characteristics of mixtures

DSCexp curves align with DTGexp curves, showing three heat absorption and release peaks within a similar temperature range, as shown in Figure 3. For the BE-1 emulsion, the heat absorption peak increases with the rise in WOS mixing ratio. This results from the evaporation of methanol and ethanol in the first stage from 25 °C to 92 °C. DSCexp value increases from −1.369 to −3.782 mW/mg. In the second stage, from 93 °C to 402 °C, hydrocarbons in the emulsion vaporize and burn. Multiple exothermic peaks emerge, leading to differences between DSCexp and DSCcal curves. In the third stage, from 403 °C to 800 °C, decomposition and combustion of residual carbon and salts induce irregular changes in DSCexp. Interaction mainly exerts an inhibitory effect at this stage. This is because the evaporation temperature of methanol and ethanol rises while the decomposition and combustion temperature of oil components declines. The phenomenon delays endothermic reactions and advances exothermic reactions [30].

Figure 3.

Comparison of DSCexp and DSCcal for collaborative incineration. (a) BE-1, (b) BE-2, (c) BE-3, and (d) BE-4. (The background colors indicate different weight loss stages, and the circles indicate the corresponding peak values of each weight loss peak).

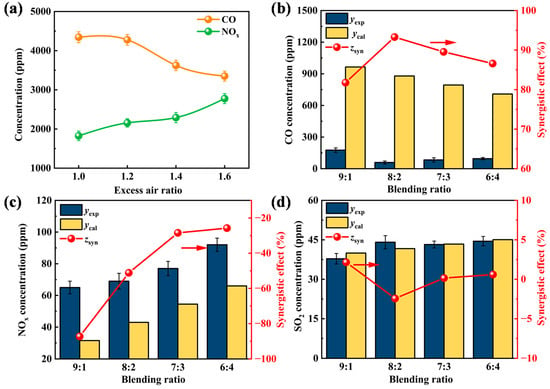

3.1.3. Flue Gas Pollutant Emission Characteristics of Multi-Source Waste Liquid Collaborative Incineration

Excess air is injected during the co-disposal of waste oil in industrial cement kilns to enable a full reaction between the carbon elements in the waste liquid and flue gas with O2. Pollutant emissions of BE-2 at 1200 °C under different excess air ratios are shown in Figure 4a. With an increase in the excess air ratio, the CO emission concentration presents a trend of first a slow decrease, then a sharp decrease, and then a slight decrease. At an excess air ratio of 1, the CO concentration reaches as high as 4343.1 ppm. When the ratio increases to 1.6, it drops to 3349.92 ppm. This is because sufficient O2 promotes the oxidation of unburned hydrocarbons. CO further reacts with O2 to form CO2, thus reducing the CO emission concentration. NOx concentration shows a steady upward trend, rising from 1825.14 ppm to 2775.49 ppm. This is mainly due to the increased O2 content promoting the formation of fuel-type NOx [34]. Considering that the residence time of waste oil in the tube furnace is much shorter than that in industrial cement kilns, an excess air ratio of 1.4 is adopted for subsequent research.

Figure 4.

(a) Pollutant emissions of BE-2 under different excess air ratios. (b–d) CO, NOx, and SO2 emission concentration and the synergistic effect of organic waste liquid collaborative incineration.

The effects of different blending ratios on the concentrations of CO, NOx, and SO2 in flue gas are shown in Figure 4b,d. During the incineration of the emulsion, the CO emission concentration is significantly lower than the theoretically calculated concentration. This is because the W/O emulsion generates a “micro-explosion” phenomenon during incineration. It enhances gas flow disturbance, increases the contact area between liquid waste and gas, and facilitates the reaction between CO and O2 [19]. The synergistic effect reaches its maximum of 93.29% at an 8:2 mixing ratio. NOx emission concentration is slightly higher than the calculated value and increases with the decrease in the blending ratio. This is mainly because WOS has a higher nitrogen content. Under the micro-explosion effect, nitrogen elements react with O2 to form more fuel-type NOx, resulting in a negative synergistic effect [35]. SO2 emission concentration is almost equal to the theoretically calculated value. This is mainly because sulfur elements are stably oxidized to SO2 in an environment with sufficient O2. Meanwhile, there are no substances such as calcium and magnesium in the emulsion that can react with SO2 to form stable sulfates [36].

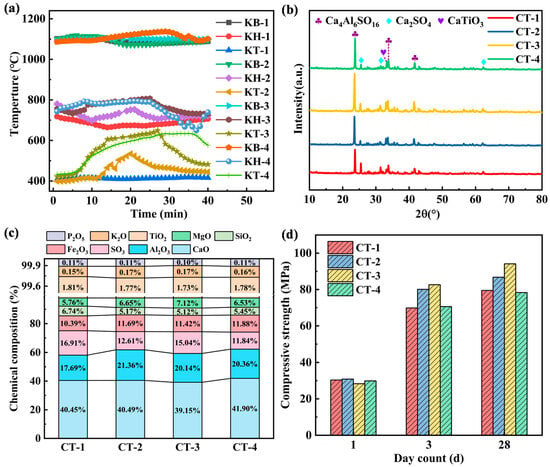

3.2. The Influence of Co-Disposal of Waste Oil Liquid on the Rotary Kiln System and Cement Clinker

Temperatures at the kiln head (KH), kiln body (KB), and kiln tail (KT), as well as changes in cement quality, were monitored. The impact of liquid waste feeding on the cement kiln system was determined based on the monitoring results. The temperature changes in the cement kiln are shown in Figure 5a. When waste oil is fed into the cement kiln, the kiln tail temperature increases significantly, the kiln head temperature rises slightly, and the kiln body temperature remains almost unchanged. This is because waste oil has a high calorific value. After being emulsified, it is sprayed into the kiln tail through a nozzle for incineration. It fully reacts with O2 to release a large amount of heat instantly. The kiln head has a lower temperature and is closest to the flame, so its temperature rise is obvious. On the other hand, due to the high temperature and large thermal inertia of the rotary kiln, the heat generated by waste oil incineration has little impact on the temperature fields of the kiln body and kiln head [37].

Figure 5.

Effect of liquid waste feeding durations on (a) cement kiln temperature, (b) cement clinker mineral composition, (c) chemical composition of cement clinker, and (d) compressive strength of cement clinker.

Different waste oil feeding durations have little impact on the mineral composition of cement clinkers, as shown in Figure 5b, with basically the same characteristic peaks at different durations. Among all samples, CT-3 has the highest content of Ca4Al6SO16. The chemical composition of a cement clinker mainly includes CaO, Al2O3, Fe2O3, and SiO2, with little change in their proportions, as shown in Figure 5c. The main reason is that the overall temperature of the rotary kiln changes slightly, exerting minimal influence on the mineral composition of the cement clinker. However, the compressive strength of the cement clinker on the first day is basically the same. On the 3rd and 28th days, CT-3 exhibits the highest compressive strength, which is 18.32% and 18.39% higher than that of CT-1, as shown in Figure 5d. This is because the local high temperature generated by waste oil incineration and the sulfur element in waste oil promote the formation of Ca4Al6SO16, improving the overall compressive strength of cement [38,39,40].

3.3. Industrial Verification of Co-Disposal of Waste Oil Liquid in Industrial Cement Kilns

Significant differences exist between the small-scale test system and actual industrial cement kilns in terms of treatment scale, temperature field distribution, and flue gas residence time. Further industrial-scale tests are required to verify the engineering adaptability and environmental safety of the technology.

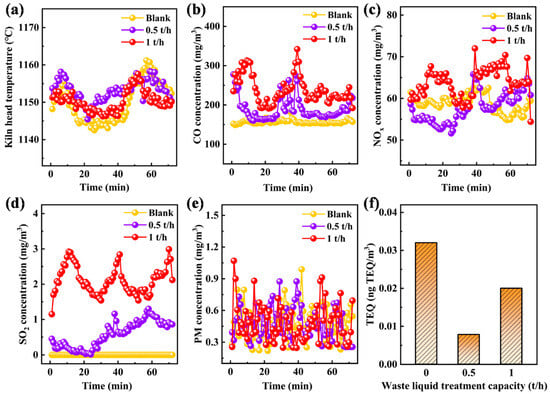

The effect of the liquid waste feeding rate on the kiln head temperature is shown in Figure 6a. Before and after liquid waste feeding, the kiln head temperature consistently fluctuates around 1150 °C. The heat generated from the incineration of waste oil has no significant impact on the kiln head temperature. It ensures sufficient stability and efficiency of the cement kiln production process [41].

Figure 6.

(a) Effect of liquid waste feeding rate on kiln head temperature. Effect of liquid waste feeding rate on emission concentrations of (b) CO, (c) NOx, (d) SO2, (e) PM, and (f) TEQ pollutants.

The emission characteristics of conventional pollutants under different liquid waste feeding rates are shown in Figure 6b–e. The micro-explosion effect from the co-incineration of multi-source liquid waste in cement kilns promotes the adequate mixing of liquid waste and air inside the kiln, enables complete oxidative decomposition of organic components, and reduces local fuel-rich zones [26]. NOx and particulate matter (PM) are not affected by the liquid waste feeding rate. The main reasons are as follows. First, the raw meal itself has a complex composition with high nitrogen content. Second, the liquid waste feeding amount accounts for less than 1% of the total raw meal mass. When incinerated at 1150 °C with sufficient oxygen, nitrogen elements generate a small amount of fuel-type NOx, while carbon elements are oxidized into CO and CO2 without particulate matter formation [42,43]. As the liquid waste feeding rate increases, the SO2 emission concentration ranges from 0 to 3 mg/m3, which is almost negligible. This is because the liquid waste contains sulfur elements. Under high-temperature conditions, calcium and magnesium elements in the raw meal react with SO2 to form stable sulfates, significantly reducing the SO2 emission concentration [44]. The CO emission concentration shows the most significant change, increasing from 155 to 247 mg/m3. The main reason is that the hydrocarbon content in the liquid waste is much higher than that in the raw meal, which may cause local oxygen deficiency at the nozzle. Although subsequent oxygen can be supplemented, CO, as an intermediate combustion product, is already generated during the oxygen-starvation stage and is difficult to oxidize rapidly [42].

Dioxin emission characteristics are shown in Figure 6f. Dioxin emission concentration has no obvious linear correlation with liquid waste feeding rate, and the emission concentration is much lower than the industrial pollutant discharge threshold. The main reasons are as follows: the cement kiln has a length of 74 m, providing sufficient flue gas residence time. On the other hand, the kiln temperature exceeds 1150 °C, which can inhibit the formation of dioxin precursors and fully decompose dioxins [45].

Results of laboratory-scale tests and engineering verification indicate that controlled feeding of liquid waste causes no significant disturbance to the key temperature fields of the kiln system during combustion. The stability of these temperature fields not only indirectly confirms the consistency of cement clinker quality but also fully verifies the operational reliability of this co-disposal process.

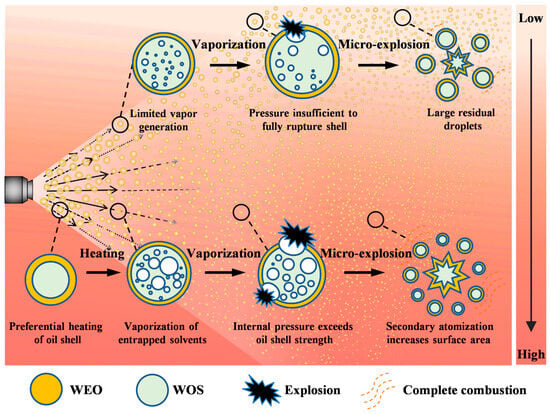

3.4. Mechanism of Collaborative Incineration of Organic Waste Liquid

In W/O emulsion co-incineration, the oil layer evaporates first, and the inner solvent or water evaporates at a lower temperature without ignition. As droplet temperature rises, the oil layer thins. When the solvent or water reaches its superheated limit, bubbles form and expand. This creates a high-pressure vapor mass, causing a “micro-explosion” and promoting droplet crushing and vaporization. The broken droplets form many small particles, surrounded by steam. When the ignition temperature is reached, combustion occurs. The mechanism of collaborative incineration of waste liquid is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Collaborative incineration mechanism of multi-source waste liquid. The length and solid-dashed style of the arrows represent the liquid injection velocity.

“Micro-explosions” promote secondary atomization of liquid waste, increasing its contact area with O2. This improves combustion efficiency and reduces CO emission concentration. When WOS in the dispersed phase has a high nitrogen content, the continuous-phase WEO possesses a high calorific value. A large amount of heat is released during incineration, leading to an increase in local furnace temperature. This promotes the generation of more fuel-type NOx from WOS. In addition, the flame spreads from the local ignition area to the entire volume of the combustible mixture. It further enhances the fuel burnout rate [46].

During co-incineration, water–gas reactions and decomposition reactions further improve furnace combustion conditions. The buoyancy force generated by water vapor reduces the contact area between oil droplets and the furnace wall, thereby decreasing the coking and slagging degree of the furnace wall [29]. The co-disposal of waste liquid in cement kilns is an energy utilization method with broad application prospects. “Micro-explosions” are an effective approach to improving liquid waste atomization, combustion efficiency, and emission reduction effects.

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Significant differences exist in the combustion characteristics between the single-component incineration and co-incineration of WEO and WOS. Their interaction can optimize combustion energy consumption and safety. The maximum weight loss rates of WEO and WOS occur at 378 °C and 77 °C, respectively. The maximum weight loss rates at the corresponding temperatures are −1.079%/°C and −5.433%/°C, respectively. During co-incineration, the temperature corresponding to the minimum DTGexp in the first weight loss stage increases from 75 °C to 86 °C, enhancing incineration safety. The temperature corresponding to the minimum DTGexp in the second and third weight loss stages decreases from 363 °C to 304 °C, reducing the hydrocarbon oxidation temperature. Additionally, the minimum DTGexp is consistently higher than DTGcal, demonstrating that the interaction can enhance the complete combustion of hydrocarbons.

- (2)

- The micro-explosion effect during the co-incineration of W/O emulsion alters the emission patterns of flue gas pollutants. The micro-explosion effect results in the CO emission concentration of the emulsion being much lower than the theoretically calculated value. It significantly improves combustion efficiency. Under the promotion of the micro-explosion effect, nitrogen elements in the emulsion are more prone to oxidation. This causes the experimental value of NOx to be higher than the theoretical value, showing a negative synergistic effect. The SO2 emission concentration is basically not affected by the micro-explosion effect.

- (3)

- Small-scale rotary kiln tests have verified that liquid waste feeding has no negative impact on the stability of the kiln system and the quality of the tcement clinker. After liquid waste feeding, the kiln tail temperature increases slightly due to the heat released from liquid waste combustion. However, the kiln head and kiln body temperatures remain stable. There are no significant differences in the mineral composition and characteristic peaks of cement clinker, with stable compressive strength.

- (4)

- The co-disposal of waste liquid in industrial cement rotary kilns exhibits excellent engineering feasibility and environmental safety. Appropriate waste liquid feeding has no impact on kiln head stability, NOx, and PM emissions. Calcium and magnesium in the raw meal react with SO2 to achieve efficient sulfur fixation. The relatively higher CO concentration is only caused by temporary oxygen deficiency in the local nozzle area, and the flue gas meets the emission standards. The dioxin emission concentration is much lower than the industrial emission threshold and has no obvious linear correlation with the feeding rate. This is mainly due to the high temperature of the kiln body and sufficient flue gas residence time.

Author Contributions

Z.S.: Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Writing—review and editing. Z.Y.: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Investigation, Formal Analysis, Writing—Original Draft, Review, and Editing. X.W. (Xinxin Wei): Conceptualization, Writing—Review and Editing. F.Z.: Formal Analysis, Writing—Review and Editing. Y.P.: Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Writing—Review. X.W. (Xujiang Wang): Conceptualization, Writing—Review. X.Z.: Conceptualization, Writing—Review. Y.M.: Conceptualization, Writing—Review. W.W.: Conceptualization, Writing—Review. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2020YFC1910000) and Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (No. ZR2022QB079).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Xu, W.; Wang, G.; Liu, S.; Wang, J.; McDowell, W.H.; Huang, K.; Raymond, P.A.; Yang, Z.; Xia, X. Globally elevated greenhouse gas emissions from polluted urban rivers. Nat. Sustain. 2024, 7, 938–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, J.; Pisupati, S.V.; Li, D.; Wang, Z.; Cheng, J. Dispersion mechanism of coal water slurry prepared by mixing various high-concentration organic waste liquids. Fuel 2021, 287, 119340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W. Green energy and resources: Advancing green and low-carbon development. Green Energy Resour. 2023, 1, 100009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Li, F.; Zha, X.; Mao, W.; Luo, C.; Zhang, L. New insights on co-combustion of organic waste liquid blending with pulverized coal: Synergistic effect on the combustion performance and pollutant control. Fuel 2025, 399, 135629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Yu, W.; Wang, X.; Tao, K.; Bian, Z.; Wang, H.; Wei, Y. Impact of low-dose free chlorine on the conjugative transfer of antibiotic resistance genes in wastewater effluents: Identifying key environmental factors for predictive modeling. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 485, 136824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, Z.; Hao, T.; Chen, H.; Xue, Y.; Li, D.; Pan, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.-Y.; Huang, Y. Anaerobic membrane bioreactor for carbon-neutral treatment of industrial wastewater containing N,N-dimethylformamide: Evaluation of electricity, bio-energy production and carbon emission. Environ. Res. 2023, 216, 114615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.M.; Wang, Y.C.; Zhao, S.L.; Hu, H.Y.; Cao, C.Y.; Li, A.J.; Yu, Y.; Yao, H. Review on the Current Status of the Co-combustion Technology of Organic Solid Waste (OSW) and Coal in China. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 15448–15487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Tester, J.W. Sustainable management of unavoidable biomass wastes. Green Energy Resour. 2023, 1, 100005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.Q.; Wang, L.; Wang, Z.B.; Wang, Z.T.; Xu, Y.; Sun, F.Q.; Sun, Z.Q.; Liu, Z.Z.; Zhu, L.Y. Experimental study on combustion and pollutants emissions of oil sludge blended with microalgae residue. J. Energy Inst. 2018, 91, 877–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, A.; Mao, W.; Zhu, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, L. Experimental and kinetic study on pyrolysis and combustion characteristics of pesticide waste liquid. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 111994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konist, A.; Järvik, O.; Pikkor, H.; Neshumayev, D.; Pihu, T. Utilization of pyrolytic wastewater in oil shale fired CFBC boiler. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 234, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Song, G.; Xiao, Y.; Ji, Z.; Wang, C. Characteristics of pyrolytic wastewater incineration and effects on NOx emissions of shenmu coal. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, S.-S.; Rizal, F.M.; Lin, T.-H.; Yang, T.-Y.; Wan, H.-P. Microexplosion and ignition of droplets of fuel oil/bio-oil (derived from lauan wood) blends. Fuel 2013, 113, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Wang, C.; Zhang, W.; Meng, K. Effects of Biodiesel–Ethanol–Graphene Droplet Volume and Graphene Content on Microexplosion: Distribution, Velocity and Acceleration of Secondary Droplets. Processes 2025, 13, 2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Guo, Y.; Ding, J.; Yan, S.; Fang, W. Micro-explosion enhanced evaporation and combustion performance of high energy-density JP-10 emulsified fuel droplet stabilized by amphiphilic hyperbranched polyethyleneimine. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 280, 128443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anufriev, I.S.; Kopyev, E.P.; Sadkin, I.S.; Mukhina, M.A. NOx reduction by steam injection method during liquid fuel and waste burning. Process Saf. Environ. Protect. 2021, 152, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Xi, X.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Z.; Cui, Z.; Long, W. Experimental study on nucleation and micro-explosion characteristics of emulsified heavy fuel oil droplets at elevated temperatures during evaporation. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 224, 120114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Chen, H.-W.; Yang, S. Modeling microexplosion mechanism in droplet combustion: Puffing and droplet breakup. Energy 2023, 266, 126369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Lu, Z.; Wang, T.; Che, Z. Mist formation during micro-explosion of emulsion droplets. Fuel 2023, 339, 127350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; He, J.J.; Hu, C.M.; Chen, W. Experimental and Numerical Simulation Study on Co-Incineration of Solid and Liquid Wastes for Green Production of Pesticides. Processes 2019, 7, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Gan, M.; Ji, Z.; Fan, X.; Zhang, D.; Chen, X.; Sun, Z.; Huang, X.; Fan, Y. Recent progress on the thermal treatment and resource utilization technologies of municipal waste incineration fly ash: A review. Process Saf. Environ. Protect. 2022, 159, 547–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telmadarreie, T.; Berton, P.; Bryant, S.L. Treatment of water-in-oil emulsions produced by thermal oil recovery techniques: Review of methods and challenges. Fuel 2022, 330, 125551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levermore, D.M.; Josowicz, M.; Rees, W.S.; Janata, J. Headspace Analysis of Engine Oil by Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2001, 73, 1361–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhao, G.; Du, C.; Feng, D.; Wang, L. Combustion Characteristics of Plant Chemical Polyol Waste Liquor in a Pilot Water-Cooled Incinerator. Energies 2019, 12, 4369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Li, Y.; Benally, C.; Li, Y.; Chen, C.; An, Z.; Gamal El-Din, M. Spent fluid catalytic cracking (FCC) catalyst enhances pyrolysis of refinery waste activated sludge. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 295, 126382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xia, S.; Ma, P. Thermogravimetric investigation of the co-combustion between the pyrolysis oil distillation residue and lignite. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 218, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.G.; Ma, Y.; Wang, B.; He, L.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Yue, C.T. Study of pyrolysis and combustion kinetics of oil sludge. Energy Sources Part A-Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2025, 47, 3862–3876. [Google Scholar]

- Ghiasi, F.; Golmakani, M.-T.; Eskandari, M.H.; Hosseini, S.M.H. Effect of sol-gel transition of oil phase (O) and inner aqueous phase (W1) on the physical and chemical stability of a model PUFA rich-W1/O/W2 double emulsion. Food Chem. 2022, 376, 131929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.Z.; Qi, X.W.; Dong, X.J.; Luo, S.Y.; Feng, Y.; Feng, M.; Guo, X.J. The co-pyrolysis of waste tires and waste engine oil. Energy Sources Part A-Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2022, 44, 9764–9778. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Dong, X.; Zuo, Z.; Luo, S. Catalytic Pyrolysis of Waste Bicycle Tires and Engine Oil to Produce Limonene. Energies 2023, 16, 4351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.W.; Zheng, F.; Li, J.T.; Sun, B.Y.; Che, L.; Yan, B.B.; Chen, G.Y. Catalytic pyrolysis of oily sludge with iron-containing waste for production of high-quality oil and H2 rich gas. Fuel 2022, 326, 124995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Sun, Y.; Chen, C.; Wang, X.; Tao, J.; Yan, B.; Cheng, Z.; Chen, G. Thermogravimetric analysis and synergistic optimization of multi-organic solid wastes co-incineration. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 116557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, F. Effect of interactions during co-combustion of organic hazardous wastes on thermal characteristics, kinetics, and pollutant emissions. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 423, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Yan, Z.; Wang, Q.; Wang, G. Low NOX combustion mechanism of coke oven gas with excess air coefficient and flue gas recirculation. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 729, 012075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Đorđić, D.; Milotić, M.; Ćurguz, Z.; Đurić, S.; Đurić, T. Experimental Testing of Combustion Parameters and Emissions of Waste Motor Oil and Its Diesel Mixtures. Energies 2021, 14, 5950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Peng, H.; Wu, C.; Guo, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, X.; Wei, J.; Yu, Q. Process compatible desulfurization of NSP cement production: A novel strategy for efficient capture of trace SO2 and the industrial trial. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 411, 137344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Fu, L.; Chen, T.; Zheng, G.; Yang, J.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Huang, X. Environmental impacts of cement kiln co-incineration sewage sludge biodried products in a scale-up trial. Waste Manag. 2024, 177, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Bao, Y.B.; Cai, X.L.; Chen, C.H.; Ye, X.C. Feasibility of disposing waste glyphosate neutralization liquor with cement rotary kiln. J. Hazard. Mater. 2014, 278, 500–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, D.; Mao, Y.; Jin, Y.; Song, Z.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Wang, W. Review on the use of sludge in cement kilns: Mechanism, technical, and environmental evaluation. Process Saf. Environ. Protect. 2023, 172, 1072–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunther, W.; Ferreiro, S.; Skibsted, J. Influence of the Ca/Si ratio on the compressive strength of cementitious calcium-silicate-hydrate binders. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 17401–17412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Zhu, S.; Qin, P.; Duan, L.; Chen, W.; Asamoah, E.N.; Han, J. A novel process of CO2 reduction coupled with municipal solid waste gasification by recycling flue gas during co-disposal in cement kilns. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 33827–33838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Li, Y.; Yan, J. Hazardous waste incineration in a rotary kiln: A review. Waste Dispos. Sustain. Energy 2019, 1, 3–37, Correction in Waste Dispos. Sustain. Energy 2021, 3, 255–256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42768-021-00078-9.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xiao, X.; Li, H.; Zhao, Z.; Guan, C.; Li, Y.; Hou, X.; Wang, W. Emission characteristics of condensable particulate matter during the production of solid waste-based sulfoaluminate cement: Compositions, heavy metals, and preparation impacts. Chemosphere 2024, 355, 141871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciobanu, C.; Tudor, P.; Istrate, I.-A.; Voicu, G. Assessment of Environmental Pollution in Cement Plant Areas in Romania by Co-Processing Waste in Clinker Kilns. Energies 2022, 15, 2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Yang, L.; Zhan, J.; Zheng, M.; Li, L.; Jin, R.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, M. Concentrations and patterns of polychlorinated biphenyls at different process stages of cement kilns co-processing waste incinerator fly ash. Waste Manag. 2016, 58, 280–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glushkov, D.O.; Tabakaev, R.B.; Altynbaeva, D.B.; Nigay, A.G. Kinetic properties and ignition characteristics of fuel compositions based on oil-free and oil-filled slurries with fine coal particles. Thermochim. Acta 2021, 704, 179017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.