Abstract

With the large-scale integration of power electronic converters, non-linear loads, and renewable energy generation, voltage and current waveform distortion in modern power systems has become increasingly severe, making harmonic resonance amplification and non-stationary distortion more prominent. Accurate and robust harmonic-level prediction and detection have become essential foundations for power quality monitoring and operational protection. However, traditional harmonic analysis methods remain highly dependent on pre-designed time–frequency transformations and manual feature extraction. They are sensitive to noise interference and operational variations, often exhibiting performance degradation under complex operating conditions. To address these challenges, a Unified Physics-Transformer-based harmonic detection scheme is proposed to accurately forecast harmonic levels in offshore wind farms (OWFs). This framework utilizes real-world wind speed data from Bozcaada, Turkey, to drive a high-fidelity electromagnetic transient simulation, constructing a benchmark dataset without reliance on generative data expansion. The proposed model features a Feature Tokenizer to project continuous physical quantities (e.g., wind speed, active power) into high-dimensional latent spaces and employs a Multi-Head Self-Attention mechanism to explicitly capture the complex, non-linear couplings between meteorological inputs and electrical states. Crucially, a Multi-Task Learning (MTL) strategy is implemented to simultaneously regress the Total Harmonic Distortion (THD) and the characteristic 5th Harmonic (H5), effectively leveraging shared representations to improve generalization. Comparative experiments with Random Forest, LSTM, and GRU systematically evaluate the predictive performance using metrics such as root mean square error (RMSE) and mean absolute percentage error (MAPE). Results demonstrate that the Physics-Transformer significantly outperforms baseline methods in prediction accuracy, robustness to operational variations, and the ability to capture transient resonance events. This study provides a data-efficient, high-precision approach for harmonic forecasting, offering valuable insights for future renewable grid integration and stability analysis.

1. Introduction

Driven by global decarbonization targets and the imperative to mitigate climate change, renewable generation has been rapidly integrated into modern power systems, fundamentally transforming the energy landscape [1,2]. Among these technologies, offshore wind farms (OWFs) have emerged as a pivotal component of the future energy mix, offering a scalable solution to meet the rising demand for green energy [3]. Compared to their onshore counterparts, OWFs benefit from significantly stronger and more consistent wind resources, which translate into higher capacity factors and more reliable power output. Furthermore, the expansive availability of installation areas at sea and the reduced visual and acoustic impacts on human populations position OWFs to account for a substantial and growing share of future generation capacity [4].

To facilitate the transmission of bulk power from remote marine locations to onshore load centers, OWFs are typically connected to the main grid via extensive networks of long high-voltage submarine cables. Technologically, these farms are dominated by converter-interfaced wind turbine generators (WTGs), with the Type-3 doubly fed induction generator (DFIG) being the most prevalent configuration due to its economic efficiency and variable-speed capabilities [5]. By utilizing a partial-scale power converter to control the rotor circuit, DFIGs allow for independent control of active and reactive power, thereby enhancing grid stability and operational flexibility. However, the widespread deployment of these power-electronic interfaces is a double-edged sword: while enabling flexible control and high energy conversion efficiency, it introduces significant power quality (PQ) challenges that cannot be overlooked. The high-frequency switching characteristics of the Pulse Width Modulation (PWM) converters, inherent to DFIG operation, inject substantial non-sinusoidal voltage and current harmonics into the grid [6,7]. In the specific context of offshore environments, these harmonic emissions are particularly problematic due to the unique impedance characteristics of the collection system. The extensive network of submarine cables acts as a large distributed capacitor. When this capacitance interacts with the inductance of grid transformers and reactors, it creates a complex L-C circuit prone to parallel resonance. If the frequency of the harmonics injected by the WTGs aligns with the system’s natural resonance frequency, it can lead to severe amplification of voltage and current distortions, potentially threatening system stability and damaging critical infrastructure [8]. Consequently, ensuring compliance with international standards such as IEEE 519 [9] and IEC 61000 [10] is critical. These standards impose strict limits on indices like Total Harmonic Distortion (THD) and Total Demand Distortion (TDD), particularly at the Point of Common Coupling (PCC), to safeguard the grid against thermal stress, insulation failure, and protection maloperation [9,10].

1.1. Prior Works and Motivations

In the complex landscape of modern grid management, harmonic prediction has evolved from a supplementary analysis into a critical operational necessity. It provides grid operators and network planners with a powerful mechanism to transition from reactive mitigation, intervening only after power quality (PQ) limits are violated, to a proactive management strategy [11]. High-fidelity forecasts of harmonic indices are indispensable for multiple layers of grid operation: they support the coordinated design and precise sizing of active and passive filters, facilitate the optimal scheduling of distorting loads and converter-interfaced resources, and enable sophisticated early warning systems that can preempt potential PQ violations before they threaten system stability [12]. Responding to this need, existing literature has extensively explored harmonic forecasting through various probabilistic and deterministic lenses. In the domain of probabilistic analysis, Bracale et al. introduced a method for short-term forecasting of current harmonics in distribution systems using quantile regression models. This approach represents a significant step forward by explicitly accounting for the stochastic nature of non-linear loads, thereby providing daily or weekly percentile forecasts that align seamlessly with regulatory assessment procedures [13]. Parallel to these probabilistic efforts, numerous studies have focused on deterministic forecasting of indices such as Total Harmonic Distortion (THD) and dominant harmonic orders in renewable-dominated systems. These works typically exploit correlations between historical PQ measurements and meteorological variables, utilizing wind speed and solar irradiance data to map environmental conditions to electrical distortions [14,15].

More recently, data-driven approaches based on Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL) have demonstrated superior performance over traditional statistical methods, particularly in capturing the non-linear dynamics of power electronics [16]. Hybrid models have shown particular promise; for instance, architectures combining Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) and Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference Systems (ANFIS) have been successfully deployed to predict THD in wind-solar hybrid plants, achieving higher accuracy than standalone models by leveraging the complementary strengths of neural learning and fuzzy logic reasoning [17,18,19]. This evolution has continued with the introduction of ANFIS-LSTM hybrid architectures, which are designed to capture complex temporal patterns in harmonic time series, yielding lower errors for high-order harmonics compared to conventional RNNs [20]. Similar neural-network-based predictors have been widely developed for other contexts, including photovoltaic plants [21], industrial arc furnaces [22], and general distribution networks [23].

Despite this significant methodological progress, several critical gaps remain in the current body of knowledge, particularly regarding the specific characteristics of offshore environments. First, the vast majority of forecasting studies are confined to onshore wind farms, PV systems, or generic distribution feeders, leaving harmonic prediction for offshore DFIG-based wind farms connected via long submarine cables comparatively underexplored [24]. This is a crucial omission because the physical environment of OWFs, characterized by the interaction between the substantial distributed capacitance of submarine cables and grid inductance, creates unique resonance phenomena and harmonic profiles that standard onshore models often fail to capture [8]. Second, in the limited instances where offshore scenarios are addressed, such as the work by Karadeniz et al. on the Bozcaada OWF, there is a heavy reliance on synthetic data augmentation strategies like Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) to expand limited datasets [25]. While innovative, this reliance raises the fundamental question of whether a sufficiently expressive forecasting model can learn directly from available meteorological and electrical data without the computational overhead, complexity, and potential artifacts introduced by synthetic expansion [26]. Furthermore, from an algorithmic perspective, most existing approaches rely on architectures such as ANNs, RNNs, or ANFIS, which face inherent limitations in modeling complex, long-duration sequences. Recurrent models like LSTMs and GRUs, while effective for short-term dependencies, often struggle to capture very long-range temporal dependencies and the global correlations among multiple multivariate inputs, features that are essential for characterizing harmonic behavior under the highly variable operating conditions of an OWF [27,28]. Finally, while Transformer architectures have revolutionized sequence modeling in fields such as Natural Language Processing (NLP) by utilizing attention mechanisms to capture global context [29], they have not yet been systematically explored or rigorously benchmarked against strong ML/DL baselines in the specific context of harmonic forecasting for offshore wind farms [30]. This study aims to bridge these gaps by proposing a unified, data-efficient Transformer-based framework.

1.2. Contributions

OWFs based on DFIGs and long submarine cables are prone to resonance-driven harmonic amplification, where the harmonic behavior depends on both meteorological excitation and grid-side electromagnetic dynamics. Existing data-driven approaches [31] often suffer from two practical limitations, i.e., the lack of high-fidelity, reproducible offshore harmonic benchmarks (many works rely on simplified models or synthetic data augmentation), and limited capability to capture global, long-range dependencies and multivariate couplings when using sequential recurrent architectures. To address these issues, we develop a unified harmonic prediction framework that couples electromagnetic-transient simulation with an attention-based learning model, and we make the learning targets and measurement points consistent with practical power-quality monitoring at both the PCC and the turbine terminal.

The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

- High-fidelity offshore harmonic benchmark without synthetic augmentation: We establish a reproducible benchmark for offshore harmonic prediction in a DFIG-based OWF connected through a 36 km submarine cable. The dataset is generated by detailed EMT simulations driven by real meteorological wind-speed records (Typical Meteorological Year data for the Bozcaada region), producing operational snapshots and corresponding harmonic indices (e.g., THDV) that reflect realistic operating variations, rather than relying on Generative-AI-based synthetic expansion.

- Unified Physics-Transformer with attention-based coupling modeling: We propose a Transformer encoder tailored to heterogeneous physical features, where a lightweight feature tokenizer maps measured scalars into embeddings and multi-head self-attention learns the coupling among meteorological inputs, electrical states, and harmonic responses. Compared with LSTM/GRU-style sequential modeling, the proposed attention mechanism captures global dependencies and multivariate interactions in a single forward pass, which is particularly beneficial under resonance-dominated offshore conditions.

- Multi-task learning for global and characteristic harmonics: We formulate harmonic prediction as a multi-task regression problem and design an MTL head that jointly predicts the global power-quality metric (THDV) and characteristic harmonic components (e.g., the 5th harmonic magnitude). This unified formulation improves generalization and accuracy by sharing representations across correlated harmonic targets, and it provides richer diagnostic information than single-target prediction.

- Reproducible DFIG converter implementation and monitoring-aligned measurements: We incorporate a detailed DFIG back-to-back converter implementation (including PWM switching at 2700 Hz and the associated grid-interface elements) and define measurement points consistent with engineering practice (PCC at 60 kV and turbine terminal at 575 V). This bridges the learning pipeline with realistic PQ monitoring and makes the proposed framework directly applicable to offshore-grid measurement infrastructures.

- Comprehensive benchmarking and robustness under distorted conditions: We conduct systematic comparisons against representative ML/DL baselines (e.g., RF, LSTM, GRU). The results show that the proposed framework achieves superior prediction accuracy and maintains robustness under transient and high-distortion scenarios, where conventional models often degrade.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 details the system modeling, including the Bozcaada offshore wind farm topology, DFIG configuration, submarine cable parameters, and the data generation process. Section 3 presents the proposed Unified Transformer-Based Harmonic Detection Network, explaining the Feature Tokenizer, self-attention mechanism, and multi-task learning strategy. Section 4 provides a comprehensive analysis of the experimental results, comparing the proposed model against various baselines in terms of accuracy and robustness. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper and outlines directions for future research.

2. System Modeling and Data Generation

To develop and validate the proposed Transformer-based harmonic prediction network, a high-fidelity electromagnetic transient model of an offshore wind farm (OWF) was constructed. This section details the system topology, component modeling parameters, and the process of generating the benchmark dataset using real-world meteorological data.

2.1. System Configuration and Modeling

2.1.1. Offshore Wind Farm Topology

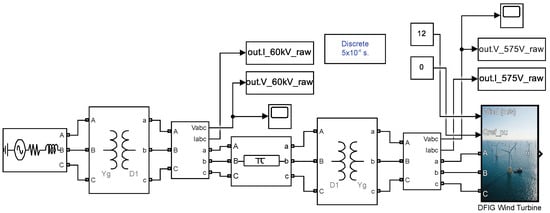

The studied system represents a typical radial offshore wind farm configuration connected to an onshore main grid, as illustrated in Figure 1. The main grid is modeled as a voltage source with a short-circuit capacity of and an ratio of 3. The power transmission system comprises two primary voltage transformation stages:

- Onshore Substation: A , transformer connecting the grid to the subsea cable. The winding configuration is Wye-grounded/Delta (). According to the system specifications, the resistances and leakage inductances of the windings are modeled as p.u., while the magnetization inductance is set to p.u.

- Offshore Substation: A , transformer () stepping down voltage to the wind turbine terminals.

Figure 1.

The Simulink model representing the studied offshore wind farm topology.

The total generation capacity is , consisting of six aggregated wind turbines.

2.1.2. Submarine Cable and DFIG Configuration

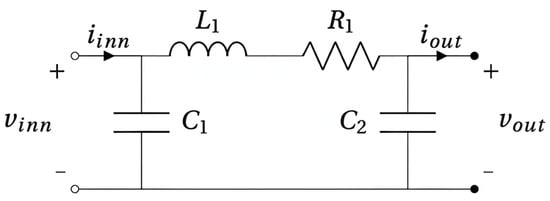

The system utilizes a long submarine cable [25] modeled using a nominal -circuit configuration in Figure 2 to capture frequency-dependent behaviors and potential resonances [32]. The specific electrical parameters for the Copper cable are listed in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Subsea cable -model circuit used for simulation.

Table 1.

Offshore Wind Farm System Configuration and Cable Parameters.

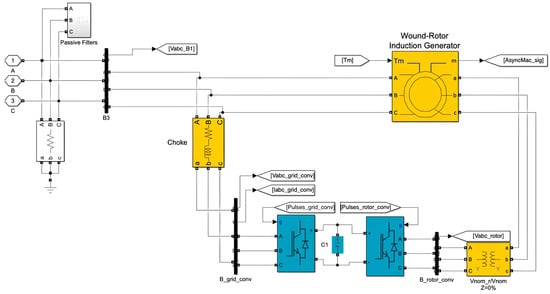

The generation units are Type-3 Doubly Fed Induction Generators (DFIGs). Each unit is rated at with a nominal stator voltage of . The detailed control structure is depicted in Figure 3 [32]. A crucial source of harmonic distortion is the power converter, which utilizes IGBTs with a switching frequency of . Key parameters of the turbine and converter system are summarized in Table 2.

Figure 3.

Under mask illustration of the DFIG wind turbine block.

Table 2.

Parameters for MW Wind Turbine.

Specifically, Figure 3 illustrates the under-mask implementation of the DFIG wind-turbine subsystem in MATLAB R2024a/Simulink 24.1. The electrical stage is constructed as a hierarchical subsystem that integrates a wound-rotor induction generator (DFIG machine block), a back-to-back power converter consisting of rotor-side and grid-side IGBT-based two-level bridges connected through a DC-link capacitor, and the grid-interface components (passive filter and choke) that connect the turbine terminal to the collection network. The key electrical and converter parameters (e.g., rated voltage, DC-link voltage/capacitance, coupling inductor , and switching frequency) follow Table 2.

The converter control and synchronization functions are implemented in dedicated control subsystems and provide the gating commands to the two converter bridges (e.g., Pulses_rotor_conv and Pulses_grid_conv in Figure 3). A PLL-based grid synchronization is adopted to obtain the electrical angle for the transformations. The rotor-side converter (RSC) regulates rotor currents in the synchronous frame to achieve the desired active/reactive power exchange, while the grid-side converter (GSC) maintains the DC-link voltage and shapes the grid-side current injection.

For reproducible harmonic analysis, the key waveforms are logged via the measurement ports in Figure 3 and exported to the workspace, including three-phase voltages and currents , active/reactive power , DC-link voltage , and selected bus voltages at the turbine terminal (B575) and the point of common coupling (PCC) at the 60 kV bus (B60). These logged voltage waveforms are subsequently used for spectrum extraction (FFT-based THD/THDV computation) as described in Section 2.2.2.

2.2. Data Acquisition and Generation

2.2.1. Meteorological Input

To ensure the forecasting model is trained on realistic operational data, the simulation is driven by actual meteorological records provided by the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre (JRC). The selected site corresponds to the Bozcaada region in the Aegean Sea, Turkey (Latitude: 39.837, Longitude: 25.967).

The Simulink model is executed over a simulation window of s, driven by the wind-speed time series from the selected meteorological record in August 2019. To construct the learning dataset, we uniformly sample the simulated signals into time instants over this window, resulting in a sampling interval of

At each sampling instant, we record the target electrical variables, such as three-phase voltages/currents and derived power quantities and form one training sample.

The extracted signals are normalized before training, so that variables with different physical units and magnitudes can be learned under a consistent scale. With s, the dataset preserves the dominant dynamics of wind-speed fluctuations over the 100 s horizon and their impact on the measured electrical quantities.

2.2.2. Harmonic Analysis and Feature Extraction

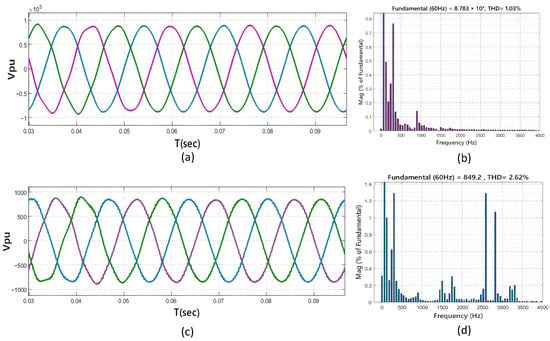

The Simulink model is executed over a simulation horizon of 100 s. The varying wind speeds drive the DFIGs, resulting in dynamic current injections and voltage fluctuations. Data are collected at two critical measurement points: the point of common coupling (PCC) at the 60 kV bus (B60) and the wind turbine terminal at the 575 V bus (B575). A Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) analysis is applied to the simulated voltage waveforms using a window size of 2 cycles to compute the total harmonic distortion of voltage (THDV). Figure 4 summarizes representative steady-state three-phase voltage waveforms and their corresponding harmonic spectra at these two buses. As shown in Figure 4a, the B60 voltage remains close to a sinusoidal waveform with relatively small distortion, whereas the B575 voltage in Figure 4c exhibits a more noticeable ripple and waveform deformation, indicating stronger distortion at the low-voltage turbine terminal that is electrically closer to the back-to-back converters.

Figure 4.

Simulation results showing (a) voltage waveform of 60 kV Bus, (b) harmonic spectrum at 60 kV, (c) voltage waveform of 575 V Bus, and (d) harmonic spectrum at 575 V Bus.

The spectra in Figure 4b,d provide quantitative evidence of this difference. Specifically, the computed THDV at B575 reaches 2.62%, which is higher than that at B60 (1.03%). This discrepancy is consistent with the propagation and attenuation of converter-generated harmonics: high-frequency components injected by the converter are most pronounced at the turbine-side terminal, while they are partially suppressed when transferred through the step-up transformer and the upstream network impedance (including the grid-side interface elements), leading to a lower THDV at the PCC. Moreover, the harmonic spectrum at B575 shows elevated components around 2560 Hz and 2820 Hz. These frequencies lie in the vicinity of the converter switching frequency of 2700 Hz and can be interpreted as switching-frequency-related emissions and PWM-induced sidebands, confirming that the DFIG power converters are the primary source of harmonic injection. The reduced magnitude of these components observed at B60 further demonstrates the attenuation effect of the transformer and network, which improves the voltage quality at the PCC and motivates using the PCC/B60 and turbine-terminal/B575 measurements as complementary inputs for subsequent feature extraction and learning.

3. A Unified Transformer-Based Harmonic Detection Network

In this section, we propose a unified harmonic detection framework specifically tailored for the multivariate and stochastic environment of offshore wind farms. While traditional Deep Learning models, such as Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), have demonstrated utility in time-series forecasting, they exhibit inherent limitations in capturing global, non-sequential dependencies among heterogeneous physical variables. To address this, we introduce a Feature Tokenizer and Transformer (Physics-Transformer) architecture.

By treating the harmonic prediction task as a regression problem on tabular data, our model leverages the self-attention mechanism to explicitly model the complex coupling between meteorological inputs and electrical states. Furthermore, to enhance the model’s generalization capability, we design a Multi-Task Learning (MTL) strategy that simultaneously regresses the global Total Harmonic Distortion (THD) and specific characteristic harmonic orders (e.g., the 5th harmonic).

3.1. Problem Formulation and Data Representation

Harmonic distortion in DFIG-based wind farms is a highly non-linear phenomenon resulting from the interaction between stochastic wind resources, power electronic switching behaviors, and grid impedance characteristics. We formulate the harmonic detection task as a supervised multi-target regression problem.

Let denote the dataset comprising N observational samples. For each time step t, the input vector consists of M continuous physical variables. These variables include meteorological conditions (e.g., wind speed ) and key electrical operating parameters (e.g., active power P, reactive power Q, and bus voltage magnitude ). Unlike image or text data, these inputs are heterogeneous scalars with different physical units and statistical distributions.

The target vector is designed to provide a comprehensive view of the power quality status. Instead of predicting a single index, the model is tasked with simultaneously estimating the Total Harmonic Distortion of Voltage () and the magnitude of the dominant 5th harmonic component (), which is critical for identifying potential resonance risks in the submarine cable network. Thus, the target is defined as:

The objective is to learn a mapping function that minimizes the divergence between the predicted power quality indices and the ground truth derived from high-fidelity electromagnetic transient simulations.

3.2. Feature Tokenizer: Manifold Projection of Physical Quantities

A critical challenge in applying Transformer architectures to power system data is that standard Transformers operate on discrete tokens (embeddings), whereas physical measurements are continuous scalars. Directly feeding scalar values into an attention mechanism is suboptimal because scalars lack the high-dimensional capacity to represent complex semantic relationships. To resolve this, we employ a Feature Tokenizer module that projects continuous physical quantities into a unified high-dimensional latent space.

For each continuous input feature (where ), the tokenizer applies a specific learnable linear transformation to map the scalar into a dense embedding vector :

where and are the trainable weight and bias vectors specific to the j-th feature, and d is the embedding dimension.

This process can be interpreted as a manifold projection, where physically distinct quantities, such as wind speed in m/s and active power in kW, are transformed into a homogeneous semantic space. This allows the subsequent Transformer layers to process heterogeneous variables uniformly. Furthermore, a learnable [CLS] token is appended to the beginning of the feature sequence. This special token serves as an aggregate representation of the entire system state, accumulating global information through the self-attention layers to facilitate the final regression task. The resulting input matrix is constructed as:

3.3. Transformer Encoder: Modeling Multivariate Couplings via Self-Attention

The core feature extraction engine consists of L stacked Transformer encoder layers. Each layer comprises two primary sub-layers: a Multi-Head Self-Attention (MHSA) mechanism and a Feed-Forward Network (FFN), with residual connections and layer normalization applied after each block. This architecture is specifically chosen for its ability to model global interactions between any pair of input features, regardless of their position in the input vector.

The MHSA mechanism is the pivotal component for capturing the non-linear coupling between different physical variables. Given the input embeddings , the mechanism first projects them into Query (), Key (), and Value () matrices. For a specific attention head h, the attention score matrix is computed as:

where is the scaling factor to prevent gradient saturation.

Remark: Physical Interpretation of Attention Weights From a power system perspective, the attention weight quantifies the coupling strength or dependency between physical feature i and feature j. Unlike “black-box” models, the attention mechanism offers a degree of interpretability regarding the electromechanical dynamics of the OWF. For instance, during the training process, the model may learn to assign a high attention weight between the Wind Speed token and the Active Power token. This mathematical correlation reflects the underlying physical reality: fluctuations in wind speed directly dictate the rotor speed and the operating point of the DFIG converters, which in turn determines the harmonic injection spectrum. By stacking multiple layers and employing multiple heads, the Physics-Transformer can simultaneously capture diverse types of interactions, such as the direct correlation between power output and THD, or the subtle inverse relationships between grid voltage magnitude and current distortions, thereby forming a comprehensive representation of the system’s harmonic behavior.

3.4. Multi-Task Learning Head and Joint Optimization

To achieve robust and comprehensive monitoring, we discard the traditional single-output design in favor of a Multi-Task Learning (MTL) head attached to the final representation of the [CLS] token, denoted as . The [CLS] embedding effectively summarizes the global context of the input features after passing through the Transformer encoder.

We connect two separate Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) branches to this shared representation to predict the distinct targets:

The rationale behind using MTL is twofold. First, THD and individual harmonics (e.g., H5) are physically correlated; THD is essentially the aggregate root-mean-square of all harmonic components. Jointly training the model on both tasks introduces a beneficial inductive bias, forcing the shared Transformer encoder to learn robust feature representations that are relevant to both global distortion and specific spectral peaks. Second, this approach improves computational efficiency by sharing the feature extraction backbone.

The entire network is trained in an end-to-end manner by minimizing a joint loss function , which balances the regression accuracy for both tasks:

where MSE denotes the Mean Squared Error, and are hyperparameters weighting the importance of the two tasks. This unified optimization objective ensures that the model not only captures the overall trend of power quality degradation but also maintains high sensitivity to specific resonant harmonic orders, which is crucial for the safety of submarine cables and filter equipment.

In practical offshore wind-farm PQ monitoring, the proposed Physics-Transformer is designed to operate on routinely available measurements rather than relying on any special-purpose ML tool. Specifically, the input vector is composed of heterogeneous yet standard operational variables (e.g., wind speed and turbine operating points from SCADA, together with electrical states at the PCC and turbine terminals measured by synchronized devices such as PMUs and power-quality meters), while the corresponding labels (THDV and characteristic harmonic magnitudes) can be obtained from recorded three-phase voltage/current waveforms through conventional FFT-based harmonic analysis.

To enable a Transformer encoder to process these continuous physical scalars, we introduce a Feature Tokenizer that performs a lightweight, learnable scalar-to-embedding mapping for each feature, thereby projecting variables with different units and distributions into a unified latent space before attention-based modeling. Building upon these embeddings, the multi-head self-attention mechanism captures the instantaneous multivariate couplings among meteorological inputs, electrical operating conditions, and harmonic responses; moreover, the learned attention weights admit a direct physical interpretation as data-driven indicators of coupling strength between measured quantities (e.g., wind-speed power interactions that influence converter operating points and harmonic injection), which improves interpretability compared with purely black-box regressors. Together, these clarifications explicitly connect the proposed architecture to realistic measurement infrastructures and outline how it can be integrated into engineering-grade PQ monitoring and early-warning workflows in renewable-dominated grids.

4. Simulations and Discussions

In this section, the superior performance of the proposed Unified Transformer-Based Harmonic Detection Network in offshore wind farm power quality monitoring is experimentally verified. The proposed model is found to be outstanding in terms of regression accuracy and generalization capability after comparative analysis with a variety of traditional machine learning and deep learning predictors. Secondly, through the detailed ablation study and feature analysis, the specific contributions of the Feature Tokenizer and Multi-Task learning strategy are validated, demonstrating the framework’s ability to account for complex electromechanical couplings.

4.1. Experimental Settings

To better reflect the stochastic and non-linear operating conditions typical in real-world offshore power transmission scenarios, the benchmark dataset used in this study was rigorously generated using a high-fidelity electromagnetic transient simulation platform (MATLAB R2024a/Simulink 24.1). Specifically, the Bozcaada offshore wind farm model (detailed in Section 2) was driven by real-world Typical Meteorological Year (TMY) wind speed data to capture realistic fluctuations. Moreover, the simulation incorporated the full dynamics of Type-3 DFIG converters, including the interaction between the submarine cable capacitance and grid inductance, to realistically mimic the inherent resonance phenomena and harmonic injections encountered in actual grid operations. Although derived from simulation, the integration of actual meteorological inputs and detailed physical modeling significantly enhances the relevance and generalization of our experimental outcomes to practical engineering applications.

Specifically, with respect to the dataset structure, the raw time-series data collected from the Point of Common Coupling (PCC) and turbine terminals were processed into a tabular format suitable for the proposed Physics-Transformer. The Simulink model was executed over a 100 s horizon, and operational snapshots were obtained by uniformly sampling the simulated trajectories over this interval, resulting in a sampling interval of s. Each snapshot corresponds to one steady operating point at a specific time instant, and the associated variables are organized into a tabular input–output pair for learning. For each sample, the input vector and the multi-task target vector are defined as follows:

- Inputs (): Meteorological and electrical state variables, including Wind Speed (), Active Power (P), Reactive Power (Q), and Bus Voltage Magnitude ().

- Target 1 (): Total Harmonic Distortion of Voltage, representing the global power quality index.

- Target 2 (): The magnitude of the 5th harmonic component, representing the dominant characteristic harmonic in DFIG systems.

It is important to clarify that unlike traditional single-task forecasting approaches, the proposed framework is fundamentally designed for multi-objective regression. Specifically, the model is trained to minimize the joint loss of both THD and H5 simultaneously. The dataset was partitioned into a training set (80%) and a testing set (20%) using a time-series split strategy to prevent data leakage. All input features were standardized using Z-score normalization to ensure training stability. This ensures that the evaluation process rigorously assesses the model’s ability to capture the mapping between operating conditions and harmonic distortions under unseen wind scenarios.

4.2. Baseline Methods and Implementation Details

In order to validate the performance of the proposed Transformer-based framework in the harmonic regression task, this experiment is designed with multiple comparison scenarios. Specifically, the following representative machine learning and deep learning baselines are included for systematic benchmarking:

- (1)

- Random Forest [33] (named as RF): An ensemble learning method constructing a multitude of decision trees. It is selected as a strong baseline for tabular data regression due to its robustness against noise and ability to capture non-linear interactions without complex feature engineering.

- (2)

- Long Short-Term Memory Network [34] (named as LSTM): A classic Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) variant designed to overcome the vanishing gradient problem. It is included to evaluate the performance of sequential modeling in capturing the temporal dynamics of wind power fluctuations.

- (3)

- Gated Recurrent Unit [35] (named as GRU): A streamlined RNN architecture with fewer parameters than LSTM. It serves as a baseline to assess whether a simpler recurrent structure offers a better trade-off between computational efficiency and prediction accuracy in harmonic forecasting.

- (4)

- Standard Multi-Layer Perceptron (named as MLP): A feed-forward neural network without attention or recurrence mechanisms. This baseline is used to quantify the specific performance gain achieved by introducing the self-attention mechanism in our proposed Transformer architecture.

- (5)

- Gradient Boosting with Neural Networks [36] (named as GB-Net): Combines traditional gradient boosting with deep learning for enhanced predictive power and model flexibility.

- (6)

- Support Vector Machine with Deep Learning Features [37] (named as SVM-DL): Integrates deep feature learning with the traditional SVM model to improve classification accuracy for high-dimensional datasets.

- (7)

- Deep K-Nearest Neighbors [38] (named as D-KNN): A deep learning variant of KNN, leveraging neural networks for enhanced feature extraction and classification.

- (8)

- Bayesian Deep Learning [39] (named as BayesDL): A modern Bayesian approach that integrates deep learning models for improved uncertainty quantification in predictions.

- (9)

- eXtreme Gradient Boosting with Deep Neural Features [40] (named as XGBoost-DNN): An integration of XGBoost and deep neural networks for large-scale, high-dimensional feature learning and boosting.

- (10)

- LightGBM with Deep Embeddings [41] (named as LightGBM-DL): A hybrid model that enhances LightGBM’s boosting capabilities by incorporating deep learning embeddings for categorical and continuous features.

- (11)

- Categorical Boosting with Neural Optimization [42] (named as CatBoost-NO): A recent iteration of CatBoost that optimizes categorical feature handling through neural network-based fine-tuning.

Note that each predictor is trained and evaluated under the exact same dataset division and pre-processing pipeline to ensure a fair comparison.

The proposed Physics-Transformer model is implemented using the PyTorch 2.5.1/CUDA 12.1 framework. The architecture configuration consists of Transformer encoder layers with attention heads. The embedding dimension for the Feature Tokenizer is set to , and the expansion factor for the Feed-Forward Network is set to 4. To prevent overfitting, a Dropout rate of 0.1 is applied. The model is trained using the AdamW optimizer with a learning rate of and a weight decay of for 200 epochs. Importantly, while our focus is on harmonic detection in offshore wind farms, we adapt and evaluate these diverse architectures to explore how the Self-Attention mechanism—originally designed for Natural Language Processing, performs in the specialized field of power quality analysis. The goal is to demonstrate that the Transformer’s ability to model global feature couplings provides a significant advantage over local (RNN) or ensemble (RF) methods in characterizing the complex, resonant behavior of distorted power systems.

4.3. Performance Analysis of Task-1: THD Prediction

The THD prediction serves as the primary benchmark for evaluating the proposed framework, as it represents the aggregate impact of all harmonic components on the offshore grid. The comparative results across different model architectures reveal distinct performance patterns that correlate with the underlying physical characteristics of DFIG-based wind farms.

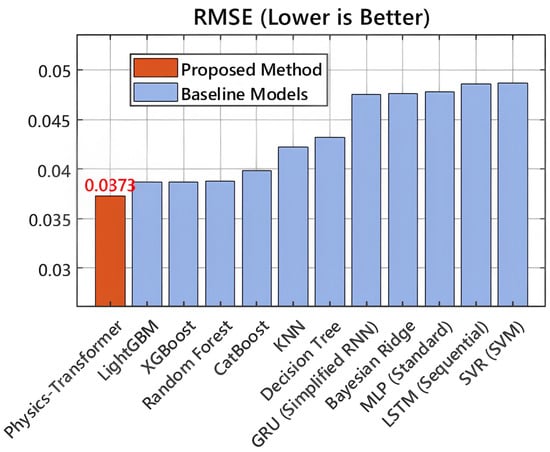

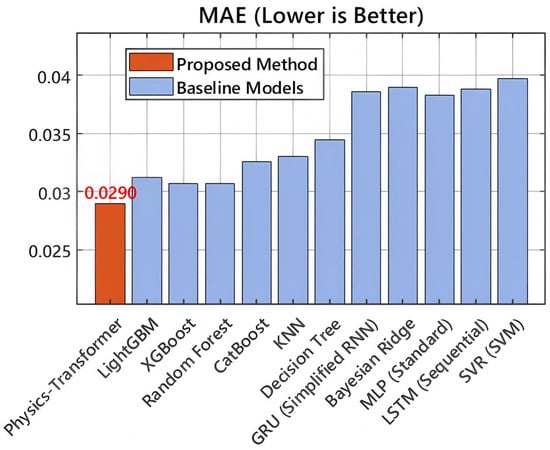

In terms of overall regression accuracy, the proposed Physics-Transformer architecture demonstrates superior capability in tracking the non-linear fluctuations of THD profiles. Quantitatively, as illustrated in Figure 5 and Figure 6, it achieves the lowest Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of and a Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of . This represents a performance improvement of approximately over the strongest ensemble baselines (LightGBM and XGBoost) and a substantial margin over traditional deep learning models. Notably, sequential models such as GRU and LSTM exhibit higher error rates ( and RMSE, respectively). This performance gap highlights a critical insight: harmonic distortion in wind farms is not merely a history-dependent temporal process but is strongly driven by instantaneous multivariate couplings, specifically, the complex interaction between stochastic wind speed variations and the immediate switching state of the converters. The Feature Tokenizer in our model successfully embeds these continuous physical variables into a latent space where these couplings are more linearly separable, thereby reducing the prediction bias.

Figure 5.

Comparison of Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) across different models. The proposed Physics-Transformer achieves the lowest error, indicating superior robustness against large deviations.

Figure 6.

Comparison of Mean Absolute Error (MAE). The proposed method demonstrates the highest overall precision in harmonic regression.

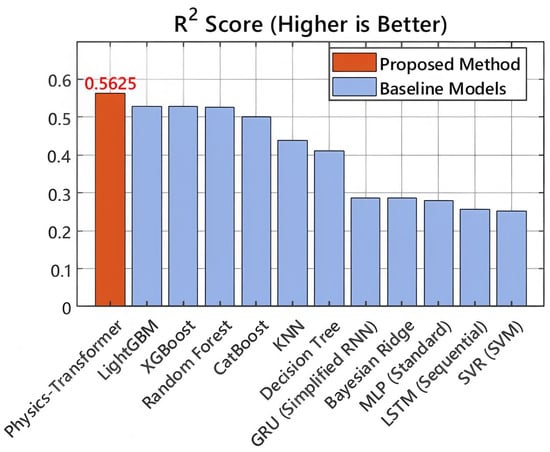

Regarding the capability to capture dynamic volatility, the Coefficient of Determination (), presented in Figure 7, provides further evidence of the Transformer’s efficacy. The proposed method yields an score of , the highest among all evaluated algorithms. In the context of offshore wind power, THD signals often contain high-frequency jitter and sudden transients due to wind gusts or grid impedance shifts. The low scores of RNN-based baselines (LSTM: ) suggest that recurrent mechanisms struggle to retain global context amidst such volatility, often converging to a mean-value prediction. In contrast, the multi-head self-attention mechanism allows the model to dynamically attend to critical feature interactions (e.g., high wind speed concurrent with specific power output levels) regardless of their temporal distance, thus explaining a significantly larger portion of the THD variance.

Figure 7.

Comparison of Coefficient of Determination (). The significant lead of the Transformer-based model highlights its ability to capture global feature couplings better than RNNs.

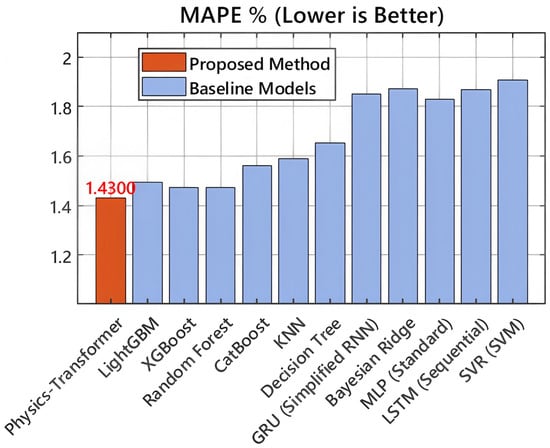

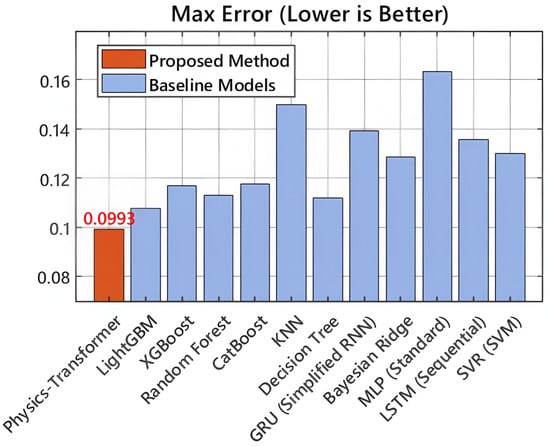

From the perspective of operational safety and reliability, the robustness of the model is validated by the Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) and Maximum Error metrics, shown in Figure 8 and Figure 9. The proposed framework achieves a MAPE of , indicating consistent precision across both low and high distortion ranges. Crucially, it records a Maximum Error of , being the only model to maintain the worst-case deviation below the threshold. In safety-critical applications, limiting the maximum error is often more important than average accuracy, as underestimating a severe harmonic resonance event could lead to equipment damage. The significant reduction in maximum error compared to MLP () and SVR () confirms that the multi-task learning objective effectively regularizes the model, preventing overfitting to noise while retaining sensitivity to extreme harmonic events.

Figure 8.

Comparison of Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE). The lower percentage indicates consistent performance across varying harmonic magnitudes.

Figure 9.

Comparison of Maximum Error. The proposed model effectively limits worst-case prediction errors, ensuring better reliability for safety-critical monitoring.

4.4. Performance Analysis of Multi-Task Learning Strategy

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed architecture in handling complex, coupled power quality indices, we evaluated the model’s performance on two simultaneous tasks: Task 1 (Global Distortion Prediction), represented by THD, and Task 2 (Characteristic Harmonic Prediction), represented by the 5th Harmonic (H5). Table 3 summarizes the quantitative comparison against twelve baseline models.

Table 3.

Quantitative Comparison of Multi-Task Learning Performance: THD vs. 5th Harmonic (H5).

4.4.1. Analysis of Task 1: THD Prediction

For the primary task of THD prediction, the proposed Physics-Transformer demonstrates dominant performance. It achieves the lowest RMSE of and the highest score of . Compared to the strongest ensemble baseline (Random Forest, ), our model improves the explanatory power by approximately . This indicates that the self-attention mechanism successfully aggregates global information from meteorological and electrical features to accurately reconstruct the overall waveform distortion, a capability that sequential models like LSTM () significantly lack due to their limited ability to capture non-temporal multivariate couplings.

4.4.2. Analysis of Task 2: 5th Harmonic (H5) Prediction

Predicting specific harmonic orders (e.g., H5) is inherently more challenging than predicting THD because individual harmonics are more sensitive to specific resonance points and high-frequency noise. As shown in Table 3, all models exhibit higher RMSE and lower scores for Task 2 compared to Task 1. The proposed Transformer model maintains competitive performance with an RMSE of . It is worth noting that CatBoost achieves a slightly better result on this specific sub-task (). This suggests that for specific high-frequency components, gradient boosting on decision trees can effectively isolate feature thresholds. However, the Transformer’s performance remains robust and superior to all other deep learning and statistical baselines (e.g., GRU, SVR), demonstrating its stability in characterizing specific spectral components.

When considering the holistic performance across both tasks, the proposed framework proves to be the most effective solution. The column RMSE (Avg) in Table 3 represents the average error across THD and H5. The Physics-Transformer achieves the best overall score of . This confirms that the Multi-Task Learning (MTL) head successfully balances the trade-off between global distortion monitoring and specific harmonic tracking. By sharing the feature extraction layers, the model learns a generalized representation of the power system state that is beneficial for both tasks, avoiding the overfitting issues observed in single-task optimized models like MLP ().

4.5. Visualization of Harmonic Tracking Performance

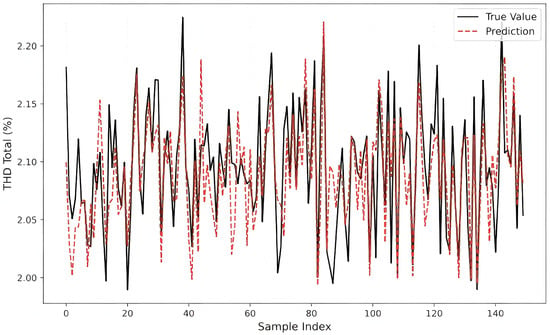

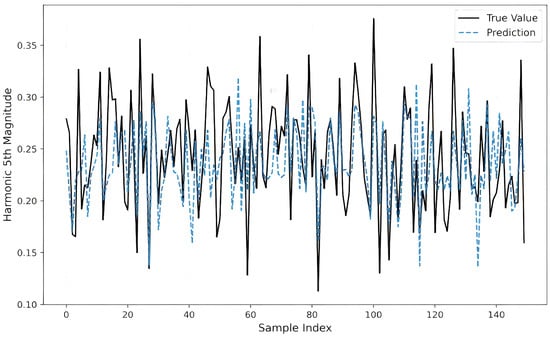

To complement the statistical metrics presented above, we provide a qualitative assessment of the model’s performance by visualizing the regression results on a representative subset of the test data. Figure 10 and Figure 11 illustrate the snapshot comparison between the ground truth (solid black lines) and the values predicted by the proposed Physics-Transformer (dashed lines) for the two simultaneous tasks.

Figure 10.

Visualization of Task 1 results: THD Prediction. The red dashed line (Prediction) closely tracks the black solid line (True), demonstrating the model’s ability to capture global distortion trends under dynamic wind conditions.

Figure 11.

Visualization of Task 2 results: 5th Harmonic Prediction. Despite the high stochasticity of the specific harmonic component (potentially caused by resonance), the model (blue dashed line) successfully captures the timing and magnitude of major fluctuations.

- (1)

- Analysis of Global Distortion Tracking (Task 1)

Figure 10 depicts the prediction curve for the Total Harmonic Distortion (THD). It can be observed that the predicted trajectory (red dashed line) exhibits a high degree of fidelity to the actual measurements.

- Trend Alignment: The model successfully captures the low-frequency trends driven by the variations in wind speed and active power output.

- Transient Response: More importantly, the model demonstrates rapid response capabilities to sudden fluctuations (e.g., the sharp peaks around time steps 40 and 85). This indicates that the self-attention mechanism effectively correlates instantaneous input features with output distortions without suffering from the “lagging” effect often seen in traditional recurrent neural networks. The tight overlapping of the curves confirms the model’s reliability in monitoring the overall power quality status of the offshore wind farm.

- (2)

- Analysis of Characteristic Harmonic Tracking (Task 2)

Figure 11 visualizes the prediction results for the 5th Harmonic component (H5), which represents a more challenging regression task due to its higher stochasticity and sensitivity to resonance phenomena.

- Volatility Capture: As shown in the figure, the H5 signal (black line) exhibits significantly more high-frequency jitter and extreme volatility compared to the smoothed THD signal. Despite this difficulty, the proposed model (blue dashed line) effectively reconstructs the phase and amplitude of the dominant variations.

- Resonance Detection: Crucially, the model successfully identifies critical resonance events where the harmonic magnitude spikes (e.g., at time steps 55 and 95). Although there are minor discrepancies in the absolute peak values, which aligns with the slightly higher RMSE observed in Table 3, the model accurately flags the occurrence of these high-risk events. This capability is vital for protective relaying and active filter control, proving that the Multi-Task Learning strategy successfully extracts robust features that are relevant to specific spectral components even in a noisy environment.

4.6. Quantitative Ablation Study on Physics-Informed Components

To quantify the specific contribution of the physics-informed architecture relative to a purely data-driven approach, an ablation study was conducted. A baseline Transformer model was established utilizing identical hyperparameters () but excluding the physics-informed components. This baseline processes raw sensor measurements without engineered physical interactions and employs standard linear projection embeddings rather than the proposed Feature Tokenizer. Table 4 summarizes the comparative performance on the test set. The proposed physics-informed framework demonstrates consistent superiority over the baseline across all metrics. Specifically, the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) decreased by 4.13%, while the Coefficient of Determination () increased by 9.39%. These results validate the efficacy of the Feature Tokenizer and physics-based interaction features. While the purely data-driven model exhibits limited capacity in capturing the highly non-linear coupling between meteorological fluctuations and electrical harmonics, the proposed model significantly enhances the resolution of system volatility by explicitly embedding physical laws, such as coupling, and utilizing periodic embeddings to represent signal dynamics.

Table 4.

Quantitative Comparison: Pure Data-Driven vs. Physics-Informed Transformer.

4.7. Applicability to Real-World Scenarios and Limitations

The proposed validation framework prioritizes practical applicability through the use of high-fidelity electromagnetic transient simulations. By incorporating actual meteorological records from Bozcaada alongside specific cable parameters, the modeling environment accurately reproduces the stochastic nature of harmonic generation found in operational systems. Although proprietary restrictions and instrumentation limits often hinder access to high-frequency offshore measurements, this simulation-based approach facilitates the synthesis of rare safety-critical scenarios including severe resonance amplification. These extreme events are statistically scarce in historical field records yet remain indispensable for the training of robust monitoring systems. Furthermore, the Feature Tokenizer is engineered to process raw physical quantities rather than normalized values to minimize the domain discrepancy during migration to physical DSP controllers. Future implementation strategies will focus on adapting the pre-trained model via transfer learning using sparse field measurement sets acquired through operator collaboration.

5. Conclusions

To address the challenges in existing harmonic forecasting methods, such as the limited capability of recurrent networks to model long-range dependencies and the heavy reliance on synthetic data augmentation, this paper proposes a Unified Transformer-Based Harmonic Detection Network to achieve accurate and robust power quality monitoring in offshore wind farms. By introducing the Feature Tokenizer and multi-head self-attention mechanism, the framework efficiently projects continuous physical variables into high-dimensional latent spaces and explicitly captures the complex non-linear couplings between meteorological inputs and electrical states without requiring generative data expansion. Meanwhile, the Multi-Task Learning strategy integrated into the network not only enables simultaneous monitoring of global distortion (THD) and specific spectral risks (e.g., 5th harmonic), but also acts as an effective regularization method, which substantially improves the model’s generalization capability under dynamic operating conditions. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed framework significantly outperforms traditional ML baselines in terms of prediction accuracy (RMSE = 0.0369) and reduces the maximum prediction error during transient events. These improvements enhance the reliability of power-quality monitoring in distorted offshore grids. Through further extension to spatial–temporal modeling, the framework is expected to be widely deployed in large-scale offshore wind clusters, providing strong technical support for proactive harmonic mitigation and helping to build a more stable and resilient renewable energy infrastructure.

Author Contributions

Methodology, X.Z. and Q.C.; validation, L.Z.; Formal analysis, Q.W. and N.Z.; Investigation, X.Z., Q.C. and L.Z.; Writing—original draft, X.Z., Q.C. and L.Z.; Writing—review & editing, X.Z., Q.C., J.P. and Y.Z.; Supervision, Q.W. and N.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by Electric Power Institute, Yunnan Power Grid Company Ltd. Scientific Research Project No. 056200KC24100043.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Xin Zhou, Li Zhang, Junzhen Peng and Yongshuai Zhao were employed by Electric Power Institute, Yunnan Power Grid Company Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The authors declare that this study received funding from Electric Power Institute, Yunnan Power Grid Company Ltd. The funder had the following involvement with the study: Methodology, validation, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing.

References

- GWEC. Global Wind Report 2024; Global Wind Energy Council: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- IRENA. World Energy Transitions Outlook 2024; International Renewable Energy Agency: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lakshmanan, P.; Sun, R.; Liang, J. Electrical collection systems for offshore wind farms: A review. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 7, 1078–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, P.; Zhu, J.; Ma, K.; Yang, G.; Hu, W.; Chen, Z. A review of offshore wind farm layout optimization and electrical system design methods. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2019, 7, 975–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Klabunde, C.; Wolter, M. Frequency-Coupled Impedance Modeling and Resonance Analysis of DFIG-Based Offshore Wind Farm With HVDC Connection. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 147880–147894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Blaabjerg, F. Power electronics: The enabling technology for renewable energy integration. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2022, 8, 39–52. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, X.; Xu, H.; Liu, H.; Kong, X. Modeling and Stability Analysis of DFIG-Based Wind Farm Using Harmonic State Space Theory. In Proceedings of the 2025 Zhejiang Power Electronics Conference (ZPEC), Hangzhou, China, 22–24 August 2025; pp. 232–237. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Huang, H.; Pan, X.; Xu, Q.; He, B.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, Z. Harmonic Resonance Mode Analysis for Offshore Wind Power System Based on Impedance Gathering. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE PES 16th Asia-Pacific Power and Energy Engineering Conference (APPEEC), Nanjing, China, 25–27 October 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Std 519-2022; IEEE Standard for Harmonic Control in Electric Power Systems. IEEE Power and Energy Society: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 1–31.

- IEC TR 61000-3-6:2008; Electromagnetic Compatibility (EMC)—Part 3–6: Limits—Assessment of Emission Limits for the Connection of Distorting Installations to MV, HV and EHV Power Systems. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008.

- Siqueira-de Carvalho, R.; Morales-Paredes, H.K.; Bates, C.; Ausmus, J.; Simões, M.G.; Sen, P.K. Overview of Big Data Analytics in Power Quality Analysis and Assessment. In Proceedings of the 9th Brazilian Technology Symposium (BTSym’23), Campinas, Brazil, 24–26 October 2024; pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, M.; Guan, Y.; Yu, Y.; Chaudhary, S.K.; Vasquez, J.C.; Guerrero, J.M. Dynamic Performance and Power Quality of Large-Scale Wind Power Plants: A Review on Challenges, Evolving Grid Code, and Proposed Solutions. IEEE Open J. Power Electron. 2025, 6, 1148–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracale, A.; Caramia, P.; De Falco, P.; Domagk, M.; Meyer, J. Probabilistic Forecasting of Current Harmonic Distortions in Distribution Systems. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Europe (ISGT EUROPE), Grenoble, France, 23–26 October 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Hadi, F.M.A.; Aly, H.H. Harmonics Forecasting of Renewable Energy System Using Hybrid Model Based on LSTM and ANFIS. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 50966–50985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.Y.; Yen, H.J.; Wu, J.W.; Huang, W.Y.; Chang, G.W. A Comparative Study of Harmonic Distortion Assessment for an Offshore Wind Farm System. In Proceedings of the 2024 21st International Conference on Harmonics and Quality of Power (ICHQP), Chengdu, China, 15–18 October 2024; pp. 451–456. [Google Scholar]

- Ravi, T.; Srividya, S.; Praveena, A.; Anil, V.; Kumar K, S.; Jayaprakash, S. Review of Detection and Classification of Power Quality Disturbances Using Machine Learning and Deep Learning Methods. In Proceedings of the 2023 Innovations in Power and Advanced Computing Technologies (i-PACT), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 8–10 December 2023; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Elymany, M.M.; Enany, M.A.; Elsonbaty, N.A. Hybrid optimized-ANFIS based MPPT for hybrid microgrid using zebra optimization algorithm and artificial gorilla troops optimizer. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 299, 117809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Yousaf, A.; Noor, J.; Cao, Y.; Dong, M.; Yang, J.; Rizk-Allah, R.M.; Elkholy, M.H.; Talaat, M. ANN-Based Model Predictive Control for Hybrid Energy Storage Systems in DC Microgrid. Prot. Control Mod. Power Syst. 2025, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Hadi, F.M.A.; Aly, H.H.; Little, T. Harmonics Forecasting of Wind and Solar Hybrid Model Based on Deep Machine Learning. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 100438–100457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, F.M.A.; Aly, H.H.; Little, T. Harmonics Forecasting of Wind and Solar Hybrid Model Driven by DFIG and PMSG Using ANN and ANFIS. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 55413–55424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coya, Z.; Khoodaruth, A.; Ramenah, H.; Oree, V.; Murdan, A.P.; Bessafi, M. Deep Learning Models in Photovoltaic Power Forecasting: A Review. In Proceedings of the 2024 1st International Conference on Smart Energy Systems and Artificial Intelligence (SESAI), Balaclava, Mauritius, 3–6 June 2024; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Sezgin, E.; Salor, Ö. Enhanced Frequency and Harmonic Estimation for Electric Arc Furnace Measurements: A Least Squares Approach to Mitigate Spectral Leakage. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2025, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ma, H.; Xiao, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H. Harmonic State Estimation for Distribution Networks Based on Multi-Measurement Data. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2023, 38, 2311–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Lin, L.; Xu, Q.; He, B.; Zhang, Z.; Ye, Q. Offshore Wind Power System Resonance Stability: Modelling, Analysis, and Methods Comparison. In Proceedings of the 2025 10th Asia Conference on Power and Electrical Engineering (ACPEE), Beijing, China, 15–19 April 2025; pp. 1464–1472. [Google Scholar]

- Karadeniz, A. Advancing harmonic prediction for offshore wind farms using synthetic data and machine learning. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2025, 127, 110613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Xiao, W.; Zhang, M.; Guo, S.; Zhao, J.; Shen, F. Image Data Augmentation for Deep Learning: A Survey. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2204.08610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengio, Y.; Simard, P.; Frasconi, P. Learning long-term dependencies with gradient descent is difficult. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 1994, 5, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, B.; Zohren, S. Time-series forecasting with deep learning: A survey. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2021, 379, 20200209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 6000–6010. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, X.; Zhang, D.; Zhu, X. Deep learning based forecasting of photovoltaic power generation by incorporating domain knowledge. Energy 2021, 225, 120240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Xu, J.; Wang, J.; Long, M. Autoformer: Decomposition Transformers with Auto-Correlation for Long-Term Series Forecasting. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Beygelzimer, A., Dauphin, Y., Liang, P., Vaughan, J.W., Eds.; Curran Associates Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Karadeniz, A. Harmonic forecasting in offshore wind systems utilizing DFIG on Bozcaada Island: A hybrid machine learning and deep learning approach. Eng. Res. Express 2025, 7, 025280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long Short-Term Memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, R.; Salem, F.M. Gate-variants of Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 60th International Midwest Symposium on Circuits and Systems (MWSCAS), Boston, MA, USA, 6–9 August 2017; pp. 1597–1600. [Google Scholar]

- Badirli, S.; Liu, X.; Xing, Z.; Bhowmik, A.; Doan, K.; Keerthi, S.S. Gradient Boosting Neural Networks: GrowNet. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2002.07971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zareapoor, M.; Shamsolmoali, P.; Kumar Jain, D.; Wang, H.; Yang, J. Kernelized support vector machine with deep learning: An efficient approach for extreme multiclass dataset. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2018, 115, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, T.; Lei, Z.; Zhu, T.; Zeng, S.; Li, Y.; Yuan, C. Deep Metric Learning for K Nearest Neighbor Classification. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2023, 35, 264–275. [Google Scholar]

- Gal, Y.; Ghahramani, Z. Dropout as a Bayesian approximation: Representing model uncertainty in deep learning. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on International Conference on Machine Learning—Volume 48, New York, NY, USA, 20–22 June 2016; Volume 10, pp. 1050–1059. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Luo, H.; Zhao, B.; Zhao, X.; Han, Z. Short-Term Power Load Forecasting Based on Clustering and XGBoost Method. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 9th International Conference on Software Engineering and Service Science (ICSESS), Beijing, China, 23–25 November 2018; pp. 536–539. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, R. Research on LightGBM Algorithm for Subway Gate Fault Detection. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Control, Electronic Engineering and Machine Learning (CEEML), Guangzhou, China, 22–24 November 2024; pp. 116–120. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, C.; Chu, J.; Han, T.; Hu, Q. Partial Discharge Recognition of Medium Voltage Switchgear Based on CatBoost Model. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 5th International Conference on Dielectrics (ICD), Toulouse, France, 30 June–4 July 2024; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.