Abstract

The article presents an extensive review of modern technological solutions for pulverized coal combustion, with emphasis on combustion modifiers and biomass co-firing. It highlights the role of coal in the national energy system and the need for its sustainable use in the context of energy transition. The pulverized coal combustion process is described, along with factors influencing its efficiency, and a classification of modifiers that improve combustion parameters. Both natural and synthetic modifiers are analyzed, including their mechanisms of action, application examples, and catalytic effects. Special attention is given to the synergy between transition metal compounds (Fe, Cu, Mn, Ce) and alkaline earth oxides (Ca, Mg), which enhances energy efficiency, flame stability, and reduces emissions of CO, SO2, and NOx. The article also examines biomass-coal co-firing as a technology supporting energy sector decarbonization. Co-firing reduces greenhouse gas emissions and increases the reactivity of fuel blends. The influence of biomass type, its share in the mixture, and processing methods on combustion parameters is discussed. Finally, the paper identifies directions for further technological development, including nanocomposite combustion modifiers and intelligent catalysts integrating sorption and redox functions. These innovations offer promising potential for improving energy efficiency and reducing the environmental impact of coal-fired power generation.

1. Introduction

The conscious and responsible use of coal, when using modern and appropriate technologies, will allow it to not only be treated as a foundation for development but also as a crucial element of industrial evolution—until more competitive energy sources are found or appropriately developed. The key direction remains the search for integrated solutions that combine economic needs with environmental protection [1]. In this study, Poland was used as an example of a representative coal-reliant country, in which coal still plays a crucial role in ensuring energy security and the stability of the power system. The aim was not to provide a detailed analysis of the energy policy of a single country, but rather to embed the technical issues discussed (pulverized coal combustion, combustion modifiers, and biomass co-firing) within a realistic system context that is characteristic of many coal-based economies worldwide. Beyond Poland, the most important country in which coal remains the primary energy source is China, where it accounts for a significant share of electricity generation and is fundamental to energy security and the operation of heavy industry. Other countries in which coal continues to play a major role include India, South Africa, Indonesia, Australia, and Kazakhstan, although their energy mix structures and the pace of energy transition differ considerably. Coal, which constitutes 64% of Poland’s domestic fossil fuel resources, plays a key role in ensuring energy security, and thus national security. It determines the country’s development, its sovereignty, and the quality of life of its citizens. According to statistics, at current mining levels, coal resources in Poland will suffice for 393 years of exploitation, making it a stable and long-term pillar of the energy sector. Currently, it accounts for 48% of primary energy, and as much as 80% of electricity production, which confirms its strategic importance [2]. However, energy security not only requires a reliance on coal, but also the diversification of raw material sources. It is also important to maintain the appropriate technical condition of infrastructure, and to invest in modern technological solutions. Energy security involves balancing primary energy demands with the processing possibilities of domestic energy capacities. Moreover, it also means that the sector’s reliability, which is understood as the ability to provide consumers with stable access to energy in the required quantity and quality, is ensured. At the same time, it is necessary to limit the negative impact on the natural environment by implementing technologies that support energy transformation and the gradual integration of more sustainable energy sources [3].

Pulverized coal plays a significant role in heavy industry and the energy industry due to its physicochemical properties and high calorific value [4]. Pulverizing the raw material allows for the efficient use of lower-quality coals, while simultaneously increasing boiler efficiency. Fine-grained coal particles have a significantly larger specific surface area than coarse coal, which in turn facilitates oxygen access and accelerates the combustion process. This technology ensures rapid and uniform fuel combustion and provides the foundation for modern power units [5]. The principle of pulverized coal combustion technology involves mixing finely ground coal with air in order to create a homogeneous mixture, which is then fed into the combustion chamber, where it burns quickly and efficiently [6]. The amount of primary air depends on the volatile matter content of the coal—for coals that are low in volatile matter, it is approximately 15% of the stoichiometric amount, while for coals that are rich in volatile matter, it can reach up to 25%. The remaining air, the so-called secondary air, is supplied directly to the burner. An increase in the primary air content hinders the ignition of the mixture in the furnace [5]. Lu et al. [7] studied the effect of pulverized coal fineness (50–200 μm) on, among other things, its flow characteristics in pipes. The results showed that the fineness of the ground coal had a significant impact on the flow pattern and its characteristics. Fine-grained pulverized coal tends to form a dense flow, while coarser-grained coal is more likely to form a dilute flow. The pulverization process, which is the stage of preparing pulverized coal for transport, is a complex issue. Its difficulty stems from both the need to consider the forces generated by the crushing equipment and the properties of the material itself. The heterogeneity of the raw material, the irregular grain shapes, the varying strength that results from varying degrees of cleavage, and the differences in the elasticity and the character of the surface (from smooth to rough) make this process non-uniform and difficult to predict [5,8]. A clear theory of material comminution has not yet been developed. Various approaches describe the process from slightly different perspectives. Rittinger’s theory assumes that the work required for comminution is proportional to the increase in the particle surface area. In turn, Kick’s theory focuses on work associated with deforming the entire material, while at the same time taking into account the volume and geometry of the grains. Bond’s theory is a combination of both approaches: initially—at the moment of crack formation—the work is proportional to the grain’s volume (as in Kick’s theory), and as comminution progresses, it is proportional to the surface area (as in Rittinger’s theory). Walker’s general formula integrates these approaches by taking into account both the effect of the particle’s diameter and volume on the workload in the crushing process [2,9,10]. Due to the fact that one of the basic goals of the energy industry is to ensure proper combustion quality, which in the case of pulverized coal furnaces is directly influenced by the degree of dust fineness, the selection of the grinding method and apparatus is an extremely important issue [2]. Among commercial solutions, three basic groups of mills can be distinguished: crushing mills (including ball-ring mills and roller-ring mills, both with a stationary and rolling roller), impact mills (in which the grinding process is mainly carried out by impacts), and impact-crushing mills—combining impacts and crushing [2,11]. Dust with a grain size of up to 200 µm is used in pulverized coal furnaces. The lower the volatile matter content in the coal, the finer the dust should be. This is because coal with lower reactivity requires greater fineness for efficient combustion. In practice, dust with a diameter of 88–200 µm is most commonly used, with the finest fraction being brown coal [5].

It is an undeniable fact that the combustion of pulverized coal contributes to serious environmental problems—polluting the air and negatively impacting human health and ecosystems [12,13]. It is necessary to seek solutions—technologies—that will reduce pollutant emissions and improve combustion dynamics [14,15]. One of the promising directions of development in the energy sector is the improvement of combustion processes through the use of various modifiers [16]. This includes the development of new compositions and formulation structures, as well as the search for effective methods for their implementation [17,18]. There are numerous literature reports confirming the great potential of hard coal, which can be understood as the ability to improve the efficiency of generated energy, and thus reduce greenhouse gas emissions [19,20,21,22].

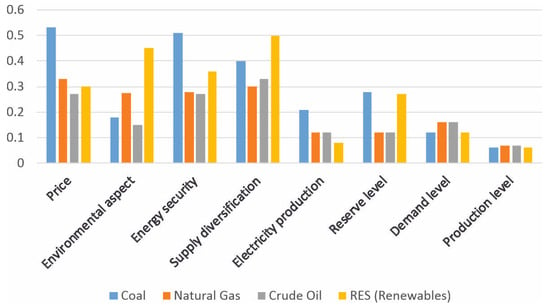

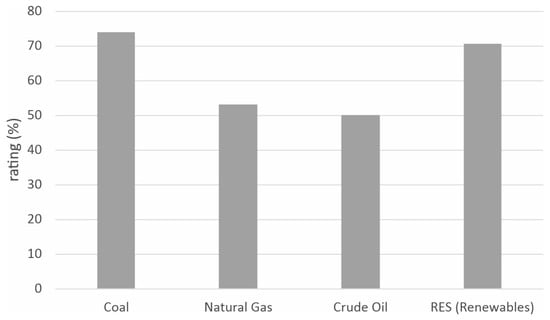

Hard coal, like any other energy solution, has both advantages and limitations. Figure 1 presents a comparative analysis (conducted in paper [1]) of the suitability of the used fuels with regard to the adopted evaluation criteria. Among the greatest advantages of coal are its price and energy security. According to various forecasts and indicators, the price of coal can be expected to gradually increase. Despite this, this raw material will still remain one of the cheapest available energy sources [1]. Figure 2 presents a summary assessment of the compared energy sources.

Figure 1.

The assessment of the future suitability of fuels for energy production in relation to selected criteria.

Figure 2.

Assessment of the suitability of individual fuels in the energy sector.

The search for methods and technologies that will extend the presence of coal in the Polish energy sector is becoming a key challenge. Within the next 30 years, there is no realistic possibility of fully replacing this raw material with renewable energy sources. The alternative is an increased dependence on imports, which carries economic and geopolitical risks [1].

The main objective of the study is a comprehensive and comparative assessment of the effectiveness of various groups of modifiers used in the pulverized coal combustion process. This includes a quantitative evaluation of typical ranges of reduction in gaseous pollutant emissions, such as CO, NOx, and SOx, as well as an assessment of the impact of modifiers on combustion efficiency, fuel burnout degree, and the amount and properties of generated solid products, including ash. An important aspect of the study is also the identification of synergistic modifier systems that enable simultaneous influence on different aspects of the combustion process without deteriorating flame stability, increasing heat losses, or negatively affecting slagging, fouling, and corrosion phenomena in boiler components. In a broader perspective, the study aims to identify solutions that can be implemented in existing power generation facilities, enabling a reduction in the environmental impact of coal-based energy systems while maintaining high efficiency and safe operation.

2. The Theoretical Basis of Pulverized Coal Combustion

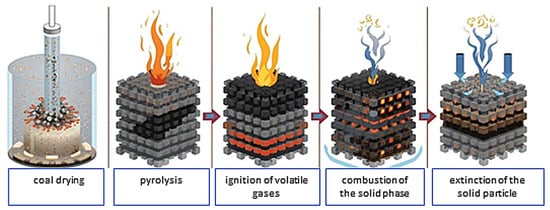

Pulverized coal combustion is a complex, step-by-step physicochemical process. The fact that coal is in a fine-grained form eliminates serious problems such as the inability to cope with load fluctuations due to its limited combustion efficiency, difficulties in removing large amounts of ash, and combustion disruptions caused by the resulting ash [23]. The first stage of the pulverized coal combustion process is the preparation of the coal fraction by grinding it in mills. The pulverized coal is then introduced into the combustion chamber by a hot stream of primary air using pneumatic pulverized coal ducts [24]. To ensure complete combustion, supplementary air (known as secondary air) is supplied separately to the combustion chamber. The combustion process itself can also be divided into specific stages, as schematically shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Stages of coal dust combustion [own elaboration].

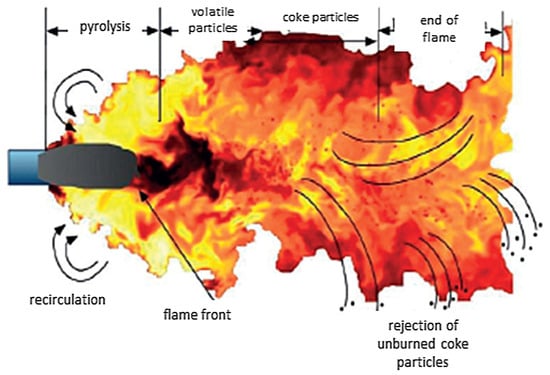

The stream of the pulverized coal-air mixture (flowing from the pulverized coal burner) is introduced into the boiler. After mixing with the hot exhaust gases in the furnace, a flame is formed when the coal particles are ignited. It consists of three characteristic zones, as illustrated in Figure 4 [25].

Figure 4.

Stages of coal dust combustion [25].

The most important factors influencing the process include dust particle size, ambient temperature, the oxygen concentration in the mixture, and the gas flow turbulence in the combustion chamber [26].

Combustion process control, understood as improving combustion dynamics or eliminating problematic issues related to pollutants and waste, can be achieved in many ways. The most important include process optimization, the modernization of existing systems, the development and implementation of combustion catalysts, as well as automation [27,28,29,30].

3. Combustion Modifiers—Division and Classification Criteria

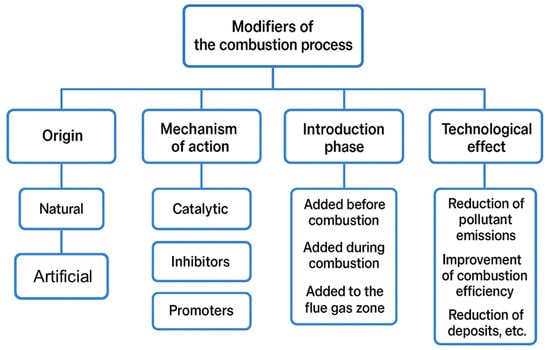

There are many types of modifiers, and their use depends on the nature of the combustion process and the desired end results. Generally speaking, modifiers play a significant role in pulverized coal combustion, as they can improve the efficiency and purity of this process. However, selecting the appropriate modifier is a complex issue that requires special attention [31]. The incorrect selection of substances, or their excessive use, can lead to undesirable consequences, such as reduced combustion efficiency or increased emissions of harmful byproducts [32]. By actively influencing the chemical reactions occurring during combustion, modifiers can lower the process temperature, increase its efficiency, reduce pollutant emissions, and improve combustion stability and control. Therefore, they constitute a key element in the development of technologies that aim for a more efficient and environmentally friendly use of pulverized coal [33]. Pulverized coal combustion modifiers can be classified based on various criteria. A sample summary is presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Example division of combustion process modifiers.

The selection of chemical compounds comprising the pulverized coal combustion modifiers has been the subject of numerous studies, which in turn have resulted in numerous patent applications and implementations. The first of the analyzed division criteria allows for the separation of natural and synthetic modifiers. Among the natural modifiers, the following can be mentioned: clays, kaolins, dolomite, limestones, and silicon and aluminum compounds [34,35]. Their advantages include availability and low price, although they are characterized by variable effectiveness depending on chemical composition and combustion conditions [36]. Synthetic modifiers are intentionally produced in chemical or metallurgical processes. This group includes, among others, transition metal salts (e.g., iron, manganese, cobalt, nickel), metal oxides, and complex compounds [37,38]. Thanks to their controlled composition, they provide repeatable effects and often higher effectiveness when compared to natural modifiers [39].

Chyć [40] presented an extensive classification of modifiers based on their mechanism of action. He distinguished the following modifiers: oxidizing, oxidation catalysts, those capable of binding gaseous acidic oxides, anticorrosive, anticaking, flammable, those with sublimation properties, and fillers.

Xue et al. [41] investigated the feasibility and effectiveness of using kaolin as an in-furnace sorbent to reduce the emission of semi-volatile metallic elements and fine particles during coal and biomass combustion, as well as the co-combustion of both fuels.

Study [42] describes the investigation of the effect of the mineral siderite calcination products that are used as a catalyst on the combustion properties of bituminous coal and anthracite. It was shown that the combustion reactivity of pulverized coal can be improved by the addition of a catalyst, with the optimal amount being 1.5% for bituminous coal and 0.5% for anthracite, respectively. With the optimal addition, the combustion rate of bituminous coal and anthracite increased by 42.5% and 9.13%, respectively. The ignition temperature decreased by 7 °C for bituminous coal and by 3 °C for anthracite, and the complete combustion index increased by 49.2% and 14.88%, respectively, when compared to raw coal. The released heat for bituminous coal and anthracite increased to 4.7 kJ/mg and 4.66 kJ/mg after the addition of the catalyst.

In 1994, Borisovna patented an invention involving the periodic dosing of sodium chloride during hard coal combustion [43]. The optimal dose was considered to be 7–8 g of NaCl per m2 of combustion area. This addition contributed to the increased thermal efficiency of the installation and reduced carbon moNOx ide (CO) and nitrogen oxides (NOx) emissions into the atmosphere. It was also found that it was possible to reduce the excess air coefficient in the flue gases and to reduce the heat losses from the flue gases by approximately 12%. Studies conducted in real heating installation conditions have shown that rock salt affects the kinetics of processes occurring in the combustion zone. Sodium chloride, commonly used as a component of fuel additives, is most often used in mixtures with other chemicals. It should be emphasized that the mechanism by which NaCl affects the obtained effects has not yet been fully and unambiguously explained [44].

Liquid and solid coal dust combustion modifiers differ primarily in their form, mode of action, and application. Liquid modifiers are solution- or oil-based mixtures consisting of a dispersant/wetting agent, a binding/adhesive component, and a catalyst [45]. They are applied to coal dust to improve fuel–air mixing, facilitate ignition, enhance complete combustion, and reduce emissions of NOx and particulate matter; they require a carrier to ensure even distribution and controlled dosing. Solid modifiers, such as metal oxides [37,38], are used in powder or granule form and added directly to the coal dust or furnace. They act mainly as chemical catalysts that accelerate combustion and decrease harmful emissions, without the need for a liquid carrier, although their distribution may be less uniform than that of liquid modifiers.

Patent [46] concerns the development of a clean and effective coal combustion catalyst, which aims to increase the speed and efficiency of the combustion process while at the same time reducing pollutant emissions. The modifier consists of organic and inorganic compounds, including sodium dodecylbenzenesulfonate, polyethylene oxyethylated alkylphenol, dibutyl phthalate, trichloroethane, tributyl phosphate, dinitrotoluene (DNT), ferrocene, calcium stearate, and yellow soda. The entire composition is dissolved in diesel fuel (90–98% by volume). Various options for modifier dosing are assumed: during storage, transport and mixing, or directly by injection into the combustion chamber. The expected effects include carbon savings of 10–30%, SO2 emission reduction by 50–80%, combustion efficiency improvement by 10–20%, no black smoke, reduced slagging and corrosion, low production costs, and ease of use.

Patent [47] proposes a high-energy catalytic additive to support coal combustion in the pulverized-fuel boilers of thermal power plants. The proposed modifier consists of a powder and a liquid. The powder is a mixture of inorganic compounds (rare-earth chlorides, metal oxides, hydroxides, lignosulfonates) that improve the fineness, reactivity, and combustion of pulverized coal. In turn, the liquid is a solution of strong oxidizers (e.g., perchlorates) and metal salts (cobalt, copper), which support combustion by generating additional combustible gases (H2, CO, CH4). The powder is added to the coal before grinding, improving the quality of the pulverized coal, increasing its reactivity, and facilitating complete combustion. The liquid is injected into the intense fire zone, where it rapidly decomposes, in turn creating a mixture of combustible gases that further enhance the combustion process. The liquid agent, manufactured according to a specific formula, is used in a ratio of 0.01% to fuel coal. The total dose of powder raw material and liquid raw material is 0.05% of the coal mass.

There are many scientific studies confirming that a material that is a production waste from one process can be successfully used as an additive that modifies the course of another operation [48]. In the case of coal dust combustion, the use of ash is often described due to its chemical composition—it is rich in iron and calcium oxides [49].

Wang et al. [50] studied the effect of a modifier (consisting of iron oxide and calcium oxide) on the combustion mechanism of coal dust. The authors determined the most favorable modifier composition based on the mutual ratio of oxides, identifying the 9Fe1Ca system as the most effective and the 7Fe3Ca system as the least effective. It was also shown, with an increase in the flux addition from 1% to 5% in the composite, that the values of the ignition index C and the characteristic combustion index S for the composite sample initially increased and then decreased. The most favorable range of composite flux addition was between 1% and 3%, while an excessive amount of it only had a limited effect on the efficiency of coal dust combustion. The oxides used in the study were the main components of a post-production by-product of the metallurgical and steel industry (BOF dust). However, it should be remembered that the ratio between the oxides may vary significantly [51].

Gao et al. [52] also explored the potential use of a composite composed of these two oxides. The study investigated the effect of the additives used separately, as well as their synergistic effect. Tests were conducted within a 1–5% additive concentration range, with the modifiers being the components of IBD dust. It was demonstrated that each of the process modifications reduced the activation energy and improved combustion efficiency.

Wang et al. [38] determined how fly ash from a steel mill and oil sludge from waste oil affect the combustion properties of coal dust. They demonstrated that incorporating these industrial wastes into the fuel mixture can improve combustion efficiency by facilitating ignition, increasing the reaction rate, and increasing heat release. Furthermore, no loss of catalytic efficiency was observed with moderate additive ratios, which means that these additives are possible to use. It is also worth noting that their use potentially reduces costs and energy consumption, while at the same time utilizing waste, which has ecological implications.

The effect of selected metal compounds and their oxides on the combustion process of various types of coal (lignite, hard coal, and anthracite) have been studied in Di et al. [53]. The effect of the additives was assessed based on thermogravimetric analysis. It was shown that the combustion effect was the result of both the used catalyst and the type of burned coal. All the used modifiers showed a positive supporting effect—they lowered the ignition and complete combustion temperature of the three types of coal, as well as increasing the combustion index (S) and the exothermic value (Q). The order of the catalytic effect was as follows: Na2CO3 > CaO > ZnO > CaCl2. It was observed that metal oxide catalysts were most effective during the coke breeze combustion stage, while metal oxide catalysts mainly affected the thermal decomposition stage.

MnO2, CaO, and Fe2O3 catalysts effects on combustion process of bituminous coal and anthracite have been investigated in Zou et al. [54]. They found that for bituminous coal, the relative order of catalyst activity in relation to the burnout rate was as follows: CaO > Fe2O3 > MnO2, while for anthracite, the order was: Fe2O3 > CaO > MnO2. They also observed that the catalysts enhanced chemical reactions that occur on the surface of coke breeze particles, and in its pores.

Guo et al. [55] developed a new catalytic combustion promoter that contained manganese dioxide along with other rare-earth and alkaline-earth metal oxides (or carbonates) in order to increase the combustion efficiency of pulverized coal. They found that with increasing promoter amounts, the ignition temperature decreased, with combustion efficiency significantly rising.

Wei et al. [56] demonstrated that CaO and MgO can improve the combustion characteristics of pulverized coal. The catalytic effect of CaO and MgO on pulverized coal combustion was found to be enhanced by increased volatile matter (VM) emissions from pulverized coal, which in turn led to a lower ignition temperature. MgO exhibited significantly higher catalytic activity than CaO in the combustion of solid coal. The mechanism of the catalytic combustion of pulverized coal in the presence of MgO differs from that of CaO.

The investigation in the research study performed by Salinas et al. [57] describe the effect of modifying the structure of a CeO2-Al2O3 and La2O3-Al2O3 catalyst by incorporating potassium into its lattice. The presence of potassium oxides (K2O) and oxygen associated with vacancies and/or lattice defects (O2−) was shown to correlate with high catalytic activity.

Reference [58] proposed using a safflower oil-based emulsion as a modifier for the pulverized coal combustion process. Experimental studies demonstrated a number of benefits of this solution, including: an increase in coal thermal efficiency by 10–15%, a decrease in harmful substance emissions by 15–25%, and a reduction in heavy metal content and slag capture by 18–23%, which in turn reduces the negative impact of the coal combustion process on the environment. The summary of the effects of selected modifiers is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of modifiers used in pulverized coal combustion and their effects.

A very important issue related to both coal combustion is the accompanying emission of harmful substances exceeding permissible regulatory limits. One method to counteract undesirable emissions through their reduction is the application of catalytic or sorption additives, as well as the optimization of process parameters. The authors of study [59] observed a simultaneous reduction in NOx and SOx emissions depending on the O2 concentration at the boiler inlet, the mass flow rate of coal, and the air-to-fuel ratio. A significant improvement in SO2 reduction was achieved when the O2 concentration was 3.28 vol.% and the coal mass flow rate was 281 t/h. NOx concentrations decreased markedly when the air-to-fuel ratio shifted from a lean condition (i.e., 7.14) to a richer condition (i.e., 7.29). In publication [60], a method for reducing SO2 emissions through the injection of dry sorbents into the furnace of a coal-fired boiler was described. It was shown that the effectiveness of the process depends mainly on sorbent reactivity, flue gas temperature, and the quality of sorbent–flue gas mixing. Demonstration studies indicated that at a Ca/S molar ratio of 2.5, SO2 reduction of approximately 40–55% could be achieved, while a maximum reduction of 72% was obtained at a Ca/S ratio of 3.8, confirming good agreement between experimental results and model predictions.

Among the additives limiting dioxin emissions from solid fuel–fired boilers, two categories can be distinguished: dioxin synthesis inhibitors (calcium oxide, ammonia, ammonium sulfate, sodium sulfate, sodium thiosulfate, sodium ammonium hydrogen phosphate(V), sulfur, and dolomite) and dioxin-reducing compounds (pyridine, quino-line, urea, ethylene glycol, amines, and EDTA) [34,61].

4. Co-Firing of Biomass with Coal Dust

Biomass is a key renewable fuel in the context of global decarbonization efforts and rising fossil fuel prices. Its use in energy production not only reduces greenhouse gas emissions, but also contributes to achieving carbon neutrality [62,63]. This is because the amount of carbon dioxide released during biomass combustion is equivalent to the amount that is absorbed by plants during photosynthesis, which makes this fuel carbon neutral [64,65]. Biomass includes a wide range of organic materials, such as agricultural and forestry waste (e.g., corn straw, wheat straw, pine sawdust, wood chips, and briquettes), as well as specially cultivated energy crops [66,67]. When compared to fossil fuels, biomass contains less sulfur and nitrogen, which in turn results in lower emissions of sulfur and nitrogen oxides during combustion [68,69]. A characteristic feature of biomass is its high content of volatile matter and oxygen, which allows it to ignite faster and be more reactive than coal [62,70,71]. It therefore aids the ignition process in fuel mixtures by accelerating degassing and improving overall combustion efficiency. Due to these properties, biomass is considered the fourth most important energy fuel after coal, crude oil, and natural gas. It stands out from other renewable energy sources not only for its wide availability and low cost, but also for its ability to produce stable energy regardless of the weather conditions [68,69,72].

Biomass co-firing is a technological process involving the simultaneous combustion of biomass with fossil fuels, most often coal, in the same energy device [73]. This method integrates the use of renewable energy with traditional combustion technologies, enables a reduction in coal consumption, limits pollutant emissions, and increases the share of renewable energy in the national energy mix [69,74]. Co-firing coal and biomass produces a synergistic effect, which is manifested by a reduction in the activation energy of the reaction and an increase in the reactivity of the mixtures [70,75]. This may result from the formation of a more reactive gas environment compared to the combustion of coal alone. At the same time, the lower average flame temperature and diluted oxygen limit the formation of NOx and PM2.5.

Co-firing biomass with coal is considered one of the most effective and cost-effective uses of biomass. In many countries, it has been implemented in existing coal-fired power plants, and it requires only minor infrastructure modifications. This technology is distinguished by its short implementation time, low investment risk, and compatibility with existing power systems [76,77].

In addition to environmental benefits (reduction in CO2, SO2, NOx, and CO), co-firing also contributes to increased energy security, the rational use of local resources, and improved power system stability [78]. Due to its adaptability to various boiler types and biomass types, this technology is a key element of the energy transition towards low-emission development [79].

In recent years, intensive research has been conducted on the co-firing of biomass with coal. It aimed to improve the energy efficiency of combustion processes and reduce gaseous pollutant emissions. Incorporating biomass into fuel blends is considered a key direction in the decarbonization of the energy sector, which will in turn enable the partial replacement of fossil fuels with renewable energy sources and reduce CO2 emissions. An important issue in the context of coal and biomass co-combustion is the amount of ash, which can reduce combustion efficiency, promote the formation of deposits and slag in the furnace, and hinder heat transfer and flame stability.

Paper [62] describes research on the co-combustion of semi-coke from briquetted biomass and pulverized coal in order to improve energy efficiency and reduce CO2 emissions. Four types of biomass were analyzed: sawdust, eucalyptus bark, corn straw, and rice husk. The biomass was gasified in a fluidized bed. Various proportions of biomass and pulverized coal were used. The analysis was conducted using thermogravimetry within the range of 25–900 °C. The best results were achieved for the sawdust and eucalyptus bark, where even an addition of 25% improved the combustion stability of pulverized coal and lowered the ignition temperature. Corn straw and rice husk showed negative effects at higher proportions (≥50%), mainly due to their high ash content, which hindered heat transfer. In turn, their addition reduced the combustion activation energy by up to 17 kJ/mol, which indicates that the reaction occurs more easily at lower temperatures.

The research presented in [80] focused on the combustion process of lignite, hard coal, and biomass (birch reed), as well as their mixtures. The biomass content in the composition of coal-based fuel mixtures was 10, 20, and 30 wt%. The studies were conducted under various conductive and convective heating conditions. The shortest ignition times were obtained for biomass due to its high porosity, low moisture content, and high volatile content. The longest ignition delay times were obtained for hard coal, as its reactivity was worse than that of biomass. Lignite ignited faster than hard coal, but slower than biomass. The addition of biomass shortened the ignition time and improved the degree of fuel combustion. It also reduced pollutant emissions. It was shown that the addition of 20 wt% of biomass to hard coal shortens the ignition delay time of particles during conductive heating by 53–70%, and during convective heating in a stream of heated air by 47–52%. Furthermore, the content of nitrogen oxides and sulfur oxides in the exhaust gases is reduced by 29% and 34%, respectively.

A significant effect of biomass type on gas emissions during co-combustion with coal was demonstrated in [68]. Four types of biomass waste were tested: poplar sawdust, rice husks, pine nut shells, and sunflower residues. Coal and biomass mixtures were prepared in the following proportions: 100:0, 90:10, 80:20, 70:30, 60:40, and 50:50 wt%. The best results were obtained for a mixture of 60% coal and 40% sunflower biomass, which demonstrated high efficiency and minimal gas emissions. In the case of the poplar sawdust, the best result was obtained with a 50:50 weight ratio. A 99% decrease in SO2 emissions and a 38% decrease in CO emissions were observed. For the rice husks, a 72% reduction in CO emissions and a 90% reduction in SO2 emissions were achieved when the carbon to biomass ratio was 70:30 wt%. In the case of the pine nut shells, an increase in the share of biomass in the mixture resulted in a reduction in harmful gas emissions.

In turn, the study presented in paper [71] analyzed the effect of the biomass (rice straw) content in pelletized mixtures with subbituminous coal (Zhundong) under rapid heating conditions. Pellets with a biomass content of 0%, 10%, 20%, 30%, and 40% by weight were prepared. The studies were conducted in a concentrating photothermal reactor. With an increasing biomass content, the degassing delay time decreased by approximately 70%, and the degassing duration increased by 22%. However, more intense slagging and the blistering phenomena occurred (related to the higher ash content in the biomass). Increasing the biomass content resulted in the appearance of additional CO emission peaks, which indicates the multistage nature of the reaction. CO2 emissions decreased with an increasing biomass content, while nitrogen oxides initially increased with a higher biomass content and then decreased due to NO reduction by NH and CO radicals. CH4 emissions were constant and independent of the mixture composition. Co-firing biomass with coal leads to significant synergistic effects—biomass accelerates degassing, lowers the activation energy of the reaction, and increases the reactivity of the mixtures. The greatest benefits were achieved for mixtures containing 20–30% biomass, which provided an optimal combination of low activation energy, high reactivity, and reduced emissions. Table 2 summarizes the key information presented in references [68,71].

Table 2.

Comparison of co-combustion studies of coal and biomass.

Paper [70] presents research on the co-combustion of coal and various types of biomass in an oxy-dioxide (O2/CO2) atmosphere. The authors aimed to better understand the mechanisms of the interactions between fuels, as well as analyze their impact on combustion efficiency and CO2 emissions. The research material consisted of bituminous coal from the Shanxi Province and seven types of biomass: sawdust, rice husks, cotton stalks, rice straw, rapeseed straw, corn cobs, and cattle manure. Adding biomass significantly accelerated coal combustion and shortened the burnout time. Biomass with a high volatile matter content improved combustion efficiency. The co-combustion of coal and biomass demonstrated a clear synergistic effect—the mass of the mixture lost more than would be expected from the theoretical summation of the effects of burning the components separately. Interactions between the different types of biomass were weak or negligible. When comparing the TG curves obtained experimentally and theoretically, a longer combustion duration and a higher burnout rate were observed compared to the combustion of coal alone. This may be due to the irregular shape of biomass particles, which promotes better heat transfer and retention, leading to higher flame temperatures. The experimental and theoretical curves nearly coincide during the initial stage of combustion. However, after approximately 1380 s, the mass loss rate in the experiment exceeds the theoretical values, indicating a synergistic effect and accelerated combustion.

The importance of biomass treatment prior to co-combustion was emphasized in paper [77]. The effect of torrefaction of corn straw and rice husks, which were co-combusted with high-sulfur bituminous coal and low-sulfur subbituminous coal, were analyzed. Blends with 50:50 wt% were prepared. The coal particles were 75–90 µm in size, while the biomass particles were 90–150 µm in size. Emissions from fuel combustion in air were measured at the kiln outlet. The results showed that for both coal-raw biomass and torrefied biomass blends, SO2 and NOx emissions were lower than those predicted from the linear interpolation of the results obtained for the pure fuels. For coal-torrefied biomass blends, SO2 emissions were lower than for coal-raw biomass blends. NOx emission efficiency from pure torrefied biomass was slightly higher than from raw biomass because the raw biomass had a higher nitrogen content per unit mass. The emission of HCl from torrefied corn stover was lower than from its raw precursor because the former had a lower chlorine content. The emission of HCl from corn stover-coal mixtures was significantly higher than from pure coal combustion. The emission of HCl from high-sulfur coal-corn stover mixtures was higher than from mixtures of the same biomass with low-sulfur coal.

The beneficial effect of biomass on pollutant emissions is also confirmed by simulation studies presented in paper [81]. The CFD analysis included predictions of volatile matter release and char combustion from particles that were co-powdered with coal and biomass, as well as simulations of combustion chemistry occurring in the gas phase. The coal used was Canadian bituminous coal with a high sulfur content. The coal was blended with 5–20% of wheat straw. One significant result is the reduction in NOx and CO2 emissions due to co-firing. This reduction depends on the proportion of biomass (wheat straw) mixed with the coal. Increasing the mass fraction of wheat straw mixed with the coal results in a decrease in NOx and CO2 concentrations at the furnace outlet.

The aim of the study described in paper [82] was to analyze the effect of biomass in fuel blends on the combustion process and pollutant emission levels. Experiments were conducted with mixtures containing 0%, 25%, 50%, 75%, and 100% of biomass. It was demonstrated that an increase in the biomass content in fuel caused significant changes in the thermal parameters of the process and also affected combustion temperature, energy conversion efficiency, and the volume of gaseous combustion product emissions.

Kazagić et al. [83] conducted experimental studies of the co-combustion of low-calorific lignite with woody biomass (sawdust) and miscanthus, which aimed at assessing pollutant emissions and ash formation under conditions similar to those of actual pulverized coal boiler operation. Twelve fuel mixtures were tested at temperatures of 1250 °C and 1450 °C, and emissions of gases such as NOx, SO2, and CO were analyzed. The results showed that the co-combustion of coal with biomass (at a share of up to 30%) does not generate significant technological problems, and with appropriate process parameters allows for a reduction in NOx and partially SO2 emissions. Particularly favorable results were achieved when miscanthus was used, which demonstrated its better environmental properties when compared to sawdust. The combustion process efficiency remained satisfactory at biomass shares of up to 15%, while above this value, an increase in the content of unburned carbon in the slag was observed.

Wang et al. [84] analyzed the co-combustion of biomass, including straw and wood, with coal in a falling-tube furnace. The study focused on monitoring nitrogen oxides and carbon monoxide (CO) emissions at different furnace heights, as well as the assessment of the unburned carbon content in fly ash. The effects of the fuel type, process temperature, biomass content in the mixture, and air partition coefficient were taken into account. The results showed that the NO concentration increased in the initial combustion phase and then gradually decreased in the upper parts of the furnace, regardless of the fuel type. NO emissions from straw and wood combustion accounted for approximately one-third and one-half of the emissions generated by the coal, respectively. In the analyzed temperature range (900–1100 °C), it was observed that an increase in temperature led to an increase in NO emissions, while a reduction in the amount of unburned carbon in the ash had little effect on CO emissions. During biomass co-combustion, a significant decrease in NO, CO, and unburned carbon emissions was observed with an increase in the biomass content in the fuel. Furthermore, studies on the effect of air partitioning showed, in the case of coal combustion, that this treatment effectively reduced NO emissions. Moreover, it led to an increase in CO emissions and unburned carbon content. This effect was significantly weaker for biomass, which in turn confirmed its more favorable environmental properties during co-combustion.

The authors of study [85] investigated MILD combustion (flameless combustion at low temperature and under diluted oxygen conditions) as an alternative technology for large-scale, low-emission co-firing of biomass–coal blends. The results showed that this method not only reduces NOx emissions but also effectively suppresses the formation of fine particulate matter. Compared with conventional swirl flame (SF) combustion, the application of MILD combustion to biomass fuel blends leads to a 45.5–49% reduction in heterogeneous fuel- NO emissions. For PM2.5 emissions, a reduction of 37–59% was observed relative to conventional low-NO swirl combustion, owing to the lower combustion temperature and oxygen concentration.

The aim of study [86] was to examine whether MILD combustion can be an effective method for the combustion and disposal of solid waste while simultaneously controlling emissions. The investigated material consisted of solid waste in the form of biomass (sawdust) combined with residual char (a by-product of thermal processes), i.e., a waste-derived fuel. In this case as well, a significant reduction in NO emissions (up to 54%) was demonstrated, achieving levels close to ultra-low NO emission standards, along with an approximately 50% reduction in PM2.5 emissions, which confirms the feasibility and relevance of implementing the discussed technology.

An important issue in the co-combustion of biomass and coal is the presence of alkali and alkaline earth metals (AAEM) and the lower ash melting temperature compared to coal [87,88]. It should be recognized that co-combustion can alter the mechanism of ash deposition on the heating surfaces of boilers, thereby directly affecting the efficiency of the process. The authors of the reference [89] demonstrated that deposits collected during the co-combustion of biomass and coal exhibit a three-layer structure, namely an outer sintered layer, an inner loose layer, and an initial adhesive layer. Using the conducted micromorphology analysis, it was shown that higher flue gas temperatures intensify the processes of agglomeration, sintering, and ash deposition, particularly in the outer layer. Additionally, the increase in flue gas temperature promoted the thermophoresis of low-melting fine particles rich in K, Ca, and Fe in the form of silicates and aluminosilicates. The condensation of alkali vapors and SO2 was enhanced due to the elevated partial pressure in the high-temperature flue gas environment, facilitating the enrichment of de-posits with alkali metals and sulfur and increasing their adhesion to heating surfaces. Higher flue gas temperatures also promoted the formation reactions of low-melting silicates containing Ca and Fe.

It can be stated that the most advantageous solution from the perspective of simultaneous reduction in NOx, SO2, and CO2 emissions while maintaining safe boiler operating conditions is co-firing biomass with pulverized coal at a biomass mass fraction of approximately 20–30%. Within this range, a clear combustion synergy effect is observed. Biomass, characterized by a high content of volatiles and oxygen and low sulfur and nitrogen content, lowers the ignition temperature of the fuel mixture and the activation energy of the reaction, improves flame stability, and accelerates carbon particle burnout. This results in a reduction in NOx emissions by approximately 20–35%, SO2 emissions by up to 30–40%, and a decrease in CO2 emissions due both to partial substitution of fossil fuel with renewable fuel and to improved combustion efficiency. At the same time, the 20–30% biomass range is indicated as the upper limit where no significant increase in slagging, ash sintering, or high-temperature corrosion of heat exchange surfaces is observed. Exceeding this level leads to increased content of alkalis and chlorine in the ash, promoting the formation of low-melting mineral phases, deposits, and aggressive corrosive compounds, especially with straw-type biomass. For older boiler types or installations particularly sensitive to ash-related issues, a more conservative biomass share of 10–15% is recommended, which still provides a noticeable reduction in NOx and SO2 while minimizing the risk of process disturbances. The use of appropriate mineral and catalytic additives, such as CaO, MgO, kaolin, or halloysite, can further reduce slagging and corrosion by binding alkalis and increasing the ash melting temperature. The use of woody biomass allows for the most favorable results in terms of combustion behavior and emissions. It is characterized by relatively low ash content, low alkali and chlorine content, and a favorable mineral composition dominated by Ca and Mg. As a result, woody biomass exhibits good reactivity, promotes stable ignition, and reduces NOx and SO2 emissions, while minimizing the risk of slagging, ash sintering, and high-temperature corrosion. Woody fuels allowed for safe co-firing even at shares of 20–30%. Agricultural residues exhibit significantly worse ash properties, despite good reactivity and high volatile content. They are rich in potassium, sodium, and chlorine, leading to the formation of low-melting alkali chlorides and sulfates. These compounds intensify slagging, deposit formation, and corrosion of heat exchange surfaces. Consequently, although agricultural residues effectively reduce SO2 and CO2 emissions, their share in the fuel mixture must be limited (typically ≤20–30%) and in practice often requires the use of mineral additives (e.g., kaolin, halloysite, CaO), which bind alkali components in the ash and raise its melting temperature. Waste fuels are characterized by the greatest variability in composition. The text notes that they can improve combustion reactivity due to the presence of transition metal oxides, but they also carry the risk of increased pollutant emissions and ash-related problems if their mineral composition is not controlled. Safe use requires a low share in the fuel mixture and precise process control. Cleaner combustion is associated with a specific ash composition. The most favorable ash contains a low amount of alkalis and chlorine, is rich in calcium, magnesium, and aluminosilicates, and is characterized by a high melting temperature and low tendency to form low-melting phases [71,76,77,80,83,90].

5. Synergy Effect

There are many known combustion modifiers that have a varying effect on efficiency. For example, copper compounds contribute to soot reduction, improved surface cleanliness, and the increased efficiency and performance of boilers [91,92]. Nickel compounds intensify combustion, improve fuel burnout, and reduce CO emissions [93,94]. The use of modifiers containing sodium and potassium compounds results in better combustion and reductions in SO2 and NO [94]. Titanium compounds also contribute to more efficient and stable combustion, as well as a reduction in the amounts of soot, NOx, SO2, and Hg [95,96,97]. Cerium compounds facilitate the post-combustion of CO and hydrocarbons, reduce NOx, and improve combustion stability [98]. Iron compounds reduce the amount of unburned fuel, NOx and dust, and limit agglomeration [99]. Manganese compounds help to reduce soot and improve fuel burnout [100]. Calcium compounds, among other things, improve the combustion process and reduce NOx [101]. Magnesium compounds primarily reduce slagging in furnaces [102]. The synergy effect in boiler technology refers to the phenomenon of the mutual reinforcement of several chemical or mineral substances, the combined use of which produces better operational results than each of them used separately. This phenomenon includes chemical processes in the furnace, as well as physicochemical phenomena in ash, sediments, and on heat exchange surfaces. This leads to improved boiler efficiency, increased availability, and reduced emissions of harmful substances. The summary is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summarizes selected combustion modifiers, their primary effects, and reported synergistic interactions, as described in the literature.

Synergy between transition metals allows for the simultaneous enhancement of oxidation, reduction, and combustion stabilization effects over a wide temperature range. Cerium combined with manganese increases the efficiency of CO oxidation and NOx reduction [97]. Combining iron compounds with manganese enhances redox activity, which in turn helps to reduce unburned ash [37]. Similar synergistic effects are observed with titanium and zirconium oxides. TiO2 combined with CaO or Zr accelerates the pyrolysis and fuel oxidation processes, while at the same time reducing NOx and SO2 emissions [97]. Studies on nanoparticle TiO2 have confirmed that this additive, in the presence of other metals (such as V, Mn, Ca, or Zr), exhibits greater catalytic activity than oxides that are used individually.

Many modern additives which are used in the energy industry are complex formulations containing mixtures of substances that have complementary effects. An example is PentoMag, which contains copper oxychloride (CuO∙CuCl2) and magnesium oxide (MgO). As described in paper [106], CuO∙CuCl2 acts as a catalytic agent and facilitates soot combustion, while MgO stabilizes ash and reduces slagging. The combined action of both components improves boiler efficiency and availability. Sadpal [106] also demonstrates synergistic effects—combining CuSO4·5H2O, NaCl, NH4Cl, CaCO3, and SiO2 at high temperatures leads to the formation of copper oxychloride (CuO∙CuCl2), which has a similar effect to PentoMag. This improves fuel combustion and reduces deposit formation. Another example is Thermact [103], which contains manganese compounds (Manganous Acetylacetonate) and copper compounds (CuSO4 5H2O). Studies [103] have shown that the presence of both metals leads to a synergistic reduction in the activation energy of carbon, which in turn results in improved flame stability and reduced slagging.

A synergetic effect also occurs in the case of single compounds with multifunctional action. Calcium peroxide (CaO2) (described in paper [104]) provides oxygen in order to support the combustion process. At the same time, upon decomposition, it forms CaO, which acts as a desulfurization sorbent. As a result, the same additive improves combustion efficiency and reduces SO2 emissions. In turn, halloysite, a natural aluminosilicate described in [90] and [107], has a dual effect. It reduces chlorine corrosion by binding potassium in the form of aluminosilicates, and also catalyzes combustion processes due to the presence of iron oxides in its structure. Research conducted at the KIT Institute in Karlsruhe [104] found that adding halloysite to biomass fuel increases the ash melting temperature by 100–350 K and reduces HCl emissions from 54% to approximately 32% of the total fuel chlorine.

Reactions between fuel components and additives can also lead to synergistic effects. For example, studies [90] described the reactions of kaolin and halloysite with KCl, which lead to the formation of potassium aluminosilicates—kalsilite (KAlSiO4) and leucite (KAlSi2O6)—with melting points above 1500 °C. The resulting mineral phases are stable and insoluble, and therefore reduce slagging and the corrosion of boiler surfaces. Studies have also shown that halloysite significantly reduces fly ash grain size, which in turn favors the formation of loose deposits instead of hard deposits [107]. This is due to a reduced tendency for particles to agglomerate, which improves heat transfer and facilitates the cleaning of heating surfaces.

Some additives exhibit their highest activity at different temperature ranges. Combining them allows for efficient combustion over a wider temperature range. As indicated in paper [108], iron oxides (Fe2O3) operate most effectively at temperatures of 700–900 °C, while titanium oxides (TiO2) and cerium oxides (CeO2) maintain high activity above 900 °C [97]. Their combined use allows for the maintaining of uniform reaction conditions throughout the combustion chamber by reducing CO and NOx emissions and improving fuel burnout.

6. Summary and Prospects for the Development of Modifiers for Pulverized Coal Combustion

The synergy effect in the combustion of solid fuels is a key tool for improving the energy efficiency and environmental performance of boilers. Combining transition metals (e.g., Fe, Cu, Mn, Ce) with alkaline earth oxides (Ca, Mg) or aluminosilicates (SiO2, Al2O3) simultaneously lowers the ignition and post-combustion temperature, improves the kinetics of the oxidation reaction, stabilizes the flame, reduces slagging and corrosion, and reduces CO, SO2, and NOx emissions. Modern combustion catalyst formulations, such as CuFeAl (KBM Affilips B.V., Oss, The Netherlands), PentoMag (Pentol, Cracow, Poland), Thermact (Enfit, Cracow, Poland) and Sadpal (SKWAT Sp. z o.o., Żółtki-Kolonia, Poland), utilize this synergy effect by combining catalytic, sorption, and stabilizing functions [109,110,111]. Selecting the appropriate proportions of the components and controlling their activation temperatures provide the basis for the further optimization of the combustion processes of pulverized coal and low-calorie fuels. In the context of biomass co-firing, the presence of volatile matter, alkali and alkaline earth metals, and low-melting-point components in biomass can alter the ignition behavior, flame temperature profile, and ash deposition characteristics in pulverized coal boilers. The review presented above shows that biomass co-firing can reduce peak flame temperatures, increase volatile release, and promote more uniform combustion, while also contributing to the formation of additional AAEM species that synergize with catalytic additives used in pulverized coal combustion. As an example, in biomass and carbon co-firing, magnesium oxide (MgO) acts as a catalyst/sorbent, enhancing CO2 capture by forming carbonates (like MgCO3) and improving the carbon matrix for adsorption, while reducing issues like slagging. The magnesium carboxylates/sulfonates are often intermediates or related to biomass pretreatment/fuel components, influencing the overall process by modifying biomass structure or capturing released acids, with MgO being key for carbon mineralization and creating high-surface-area adsorbents for cleaner energy application [112].

In the coming years, the development of combustion modifiers will focus on increasing the selectivity of redox reactions and integrating catalytic and sorption functions within a single material. A significant research direction is the development of multicomponent nanocomposites that combine the high chemical activity of transition metal oxides (Fe2O3, CuO, MnO2) with the thermal and sorption resistance of mineral carriers such as Al2O3, SiO2, or TiO2. These materials allow for the precise control of the surface microstructure by increasing the number of active sites and enabling effective operation over a wide temperature range. Intelligent combustion additives that adapt their properties to changing operating conditions will become increasingly important in the context of industry. Examples include catalysts with controlled oxygen or hydrogen release, which automatically respond to an increased CO or unburned ash content. When combined with online monitoring technologies (exhaust gas composition and flame temperature sensors), it will enable the dynamic control of the combustion process, the minimization of emissions, and an increase in efficiency. Another development direction is the combining of catalytic additives with denitrification (DeNOx) reagents such as urea or ammonia, which in turn will enable combustion and NOx reduction processes to be integrated. Hybrid catalytic systems that combine SCR/SNCR properties with catalytic combustion are currently one of the most promising research directions in the power industry. Simultaneously, work is underway on sustainable, eco-friendly combustion modifiers, in which traditional metal salts are replaced with organic–mineral complexes or biocatalysts that reduce persistent pollutant emissions. Natural materials such as halloysite, kaolin, and dolomite, which can act as both catalysts and pollutant sorbents, are a source of inspiration here.

To sum up, the further development of pulverized coal combustion modifier technology is moving toward multifunctional systems that are capable of simultaneously activating oxidation and reduction reactions, stabilizing the thermal process, sorbing pollutants, and protecting heat exchange surfaces. The use of modern nanostructures, composites, and hybrid materials will significantly increase the energy efficiency of pulverized coal boilers in the future, while at the same time reduce pollutant emissions and operating costs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.W., A.K., Z.B. and M.O. (Marek Ochowiak); data curation, S.W. writing—original draft preparation, S.W., A.K., Z.B., M.O. (Marek Ochowiak), T.H., M.T., M.P., P.L., J.S., D.C., M.M. and M.O. (Marcin Odziomek); visualization, A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the project SBAD by the Ministry of Science and High Education. This research was supported by the project “Combustion catalysts for pulverized, grate, and fluidized bed boilers,” co-financed under Priority I of the European Funds for a Modern Economy 2021–2027 (FENG), funding agreement no. FENG.01.01-IP.02-0976/24, which is a continuation of the earlier project “Development and implementation of innovative technology intensification of the combustion of solid fuels,” co-financed by the Polish National Centre for Research and Development under the national program R&D Works and Commercialization of R&D—Regional Scientific and Research Agendas/2017 (contract no. POIR.04.01.02-00.068/17).

Data Availability Statement

The data is available by request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Zdzisław Bielecki, Paweł Lewiński and Jakub Sobieraj were employed by the company KMB Catalyst Sp. z o.o. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Rybak, A. Poland’s Energy Security and Coal Position in the Country’s Energy Mix. Ph.D. Thesis, Silesian University of Technology Publishing House, Gliwice, Poland, 2020. Available online: https://delibra.bg.polsl.pl/dlibra/docmetadata?showContent=true&id=73444 (accessed on 10 October 2025). (In Polish)

- Gawlik, L.; Mirowski, T.; Mokrzycki, E.; Olkuski, T.; Szurlej, A. Coal preparation versus losses of chemical energy in combustion processes. Min. Resour. Manag. 2004, 20, 81–88. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Economy. Poland’s Energy Policy Until 2030. Annex to Resolution No. 202/2009 of the Council of Ministers of November 10, 2009; Resolution No. 202/2009 of the Council of Ministers; Ministry of Economy: Warsaw, Poland, 2009. (In Polish)

- Frontsteel Silicon Industry Co., Ltd. Available online: https://pl.fwtsialloy.com/info/what-is-meant-by-pulverized-coal--91157598.html (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Tora, B.; Kogut, K. Energy Coal Mixtures. Properties, Milling, Combustion (In Polish: Węglowe Mieszanki Energetyczne. Właściwości, Mielenie, Spalanie); Uczelniane Wydawnictwo Naukowo-Dydaktyczne AGH: Kraków, Poland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.T.; Chang, C.W.; Lin, P.H.; Li, Y.H.; Lasek, J.; Kan, H.K. Improving particle-burning efficiency of pulverized coal in new inclined jet burners. Int. J. Energy Res. 2024, 2024, 5372410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Guo, X.; Liu, Y.; Gong, X. Effect of particle size on flow mode and flow characteristics of pulverized coal. KONA Powder Part J. 2015, 32, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulusoy, U. A review of particle shape effects on material properties for various engineering applications: From macro to nanoscale. Minerals 2023, 13, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baigereyev, S.; Guryanov, G.; Suleimenov, A.; Abdeyev, B. New approach to effective dry grinding of materials by controlling grinding media actions. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Zhao, L.; Cao, Z. The crushing distribution morphology of a single particle subjected to rotary impact. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 31464–31476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lun, X.; Li, C.; Zhai, Z.; Lan, Y.; Gan, S. Prediction of vibration radiation noise from shell of straw crushing machine. Noise Vib. Worldw. 2021, 52, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akash, F.A.; Shovon, S.M.; Rahman, M.A.; Rahman, W.; Chakraborty, P.; Haque, M.N.; Monir, M.U.; Habib, M.A.; Biswas, A.K.; Chowdhury, S.; et al. Advancements in clean coal technologies in Bangladesh. Cleaner Eng. Technol. 2024, 22, 100805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Gianfrancesco, A.N. Materials for Ultra-Supercritical and Advanced Ultra-Supercritical Power Plants; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, J.; Zhang, J.; Xu, R.; Conejo, A.N.; Dang, H.; Wang, S.; Wang, L. Combustion behavior of co-injecting flux, pulverized coal, and natural gas in blast furnace and its influence on blast furnace smelting. Fuel 2024, 362, 130858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Tian, C.; Xu, X. Fuel oil combustion pollution and hydrogen-water blending technologies for emission mitigation: Current advancements and future challenges. Clean Energy Sustain. 2025, 3, 10010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Alizadeh, A.; Abed, A.M.; Nasajpour-Esfahani, N.; Smaisim, G.F.; Hadrawi, A.K.; Zekri, H.; Sabetvand, R.; Toghraie, D. The combustion process of methyl ester-biodiesel in the presence of different nanoparticles: A molecular dynamics approach. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 373, 121232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Aversano, S.; Villante, C.; Gallucci, K.; Vanga, G.; Di Giuliano, A. E-Fuels: A comprehensive review of the most promising technological alternatives towards an energy transition. Energies 2024, 17, 3995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, X.; Peng, Z.; Wang, G.; Zhang, J.; Song, T. Experimental study on gasification mechanism of unburned pulverized coal catalyzed by alkali metal vapor. J. Energy Inst. 2020, 93, 679–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauvouridis, K.; Koukouzas, N. Coal and sustainable energy supply challenges and barriers. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 696–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokrzycki, E. Prospects for the use of hard coal. Górnictwo Geoinżynieria 2006, 30, 247–265. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Gawlik, L.; Mokrzycki, E.; Ney, R. Possibilities of acceptability improvement of coal as and energy carrier. Min. Resour. Manag. 2007, 23, 105–118. Available online: https://gsm.min-pan.krakow.pl/pdf-96791-29811?filename=Possibilities-of-acceptab.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2025). (In Polish)

- Thomas, D. Finding a future for clean coal and CO2 storage technology. Fuel 2017, 195, 314–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Pandey, A.K.; Rahim, N.A. Chapter 2—Modern Energy Conversion Technologies. In Energy for Sustainable Development; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 19–39. [Google Scholar]

- Boateng, A.A. 6—Combustion and Flame. In Rotary Kilns, 2nd ed.; Butterworth Heinemann: London, UK, 2016; pp. 107–143. [Google Scholar]

- Gromaszek, K. Pulverized coal combustion advanced control techniques. IAPGOS 2019, 9, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, M.; Wang, C.; Guo, H.; Shi, Y.; Shi, S.; Wang, W.; Cao, X. Basic theory of dust explosion of energetic materials: A review. Def. Technol. 2025, 48, 48–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Peng, Q. Controlling of combustion process in energy and power systems. Energies 2025, 18, 3729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeq, A.M.; Homod, R.Z.; Hasan, H.A.; Alhasnawi, B.N.; Hussein, A.K.; Jahangiri, A.; Togun, H.; Dehghani-Soufi, M.; Abbas, S. Advancements in combustion technologies: A review of innovations, methodologies, and practical applications. Energy Conv. Manag. X 2025, 26, 100964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhikuning, A.; Setiawan, B.; Setiawan, S.A. A review of combustion in waste incinerator and its emissions. BIS Energy Eng. 2025, 2, V225030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OMC ENVAG. Available online: https://envag.com.pl/en/knowledge-base/automation-and-optimization-of-combustion-processes-in-industrial-systems-technologies-and-strategies/ (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Tic, W.J.; Guziałowska-Tic, J. The effect of modifiers and method of application on fine-coal combustion. Energies 2019, 12, 4572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennehalli, B.; Poyil, S.S.; Lokesh, B.; Nagaraja, S.; Basavaraju, S.; Rispandi; Ammarullah, M.I. A review on the formation, recovery, and properties of coal fly ash (CFA)-derived microspheres for sustainable technologies and biomedical applications. Next Mater. 2025, 9, 101172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielecki, Z. Control in Multiphase Flow Systems. Ph.D. Thesis, Silesian University of Technology, Gliwice, Poland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Krupińska, A.; Bielecki, Z.; Ochowiak, M.; Włodarczak, S.; Smyła, J.; Dziuba, J.; Bielecki, M. Perspectives on optimizing coal combustion process: New research directions in the context of sustainable energy. Rynek Energii 2024, 2, 35–42. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Raho, B.; Colangelo, G.; Milanese, M.; de Risi, A. A critical analysis of the oxy-combustion process: From mathematical models to combustion product analysis. Energies 2022, 15, 6514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raganati, F.; Miccio, F.; Ammendola, P. Adsorption of carbon dioxide for post-combustion capture: A review. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 12845–12868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Hong, C.; Xing, Y.; Li, Y.; Feng, L.; Jia, M. Combustion behaviors and kinetics of sewage sludge blended with pulverized coal: With and without catalysts. Waste Manag. 2018, 74, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zou, C.; Zhao, J.; Wang, F. Combustion characteristics of coal for pulverized coal injection (PCI) blending with steel plant flying dust and waste oil sludge. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 28548–28560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgert, K.J. Oxyfuel Carbon Capture for Pulverized Coal: Technolo-Economic Model Creation and Evaluation Amongst Alterntives. Ph.D. Thesis, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, University of Michigan, Pensilvania, PA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chyc, M. The role of fuel additives in the fuel combustion process. Research Reports of the Central Mining Institute. Min. Environ. 2012, 1, 5–16. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Xue, Z.; Zhong, Z.; Lu, P.; Guo, F. Capture effect of K and Pb by kaolin during co-firing of coal and wheat straw: Experimental and theoretical methods. Fuel 2024, 360, 130635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, Z.; Chun, T.; Long, H.M.; Meng, Q.; Wang, P.; Yang, J. Study on the effects of catalyst on combustion characteristics of pulverized coal. Metall. Res. Technol. 2017, 114, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borisovna, E.O. Method of Burning Solid Piece Fuel in Layers. Patent No. 201116, 15 April 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Szkarowski, A.; Naskręt, L. Improving the efficiency and quality of layered fuel combustion. Install. Mag. 2011, 2, 24–25. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Bielecki, Z.; Ochowiak, M.; Włodarczak, S.; Krupińska, A.; Matuszak, M.; Lewtak, R.; Dziuba, J.; Szajna, E.; Choiński, D.; Odziomek, M. The analysis of the possibility of feeding a liquid catalyst to a coal dust channel. Energy 2021, 14, 8521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guangdong Yue Ke Environmental Protection Technology Co., Ltd. Method for Improving Combustion Speed of Coal. Publication of CN103194293A, 10 July 2013. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/CN103194293A/en?oq=Method+for+improving+combustion+speed+of+coal.+Patent.+Number:+CN103194293A (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Wang, B. Catalytic Combustion-Supporting Additive for Pulverized Coal Boiler of Fuel Electric Plant. Publication of CN103351906A, 24 July 2013. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/CN103351906A/en (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Zou, C.; Wu, H.; Zhao, J.; Li, X. Effects of dust collection from converter steelmaking process on combustion characteristics of pulverized coal. Powder Technol. 2018, 332, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yan, Z.; He, R.; Ban, Y.; Zhou, H.; Liu, Q. Structural evolution of iron components and their action behavior on lignite combustion. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2025, 78, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, J.; Xu, R.; Wang, L.; Zhu, Q.; Zeng, Y.; Zhang, N.; Huana, X. Effect of Fe2O3/CaO on pulverized coal combustion behavior and strengthening combustion mechanism. Energy 2025, 321, 135103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, C.; Zhao, J. Investigation of iron-containing powder on coal combustion behavior. J. Energy Inst. 2017, 90, 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Zhang, G.; Zheng, H.; Jiang, X.; Shen, F. Combustion performance of pulverized coal and corresponding kinetics study after adding the additives of Fe2O3 and CaO. Int. J. Min. Metal. Mat. 2022, 30, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, H.; Wang, Q.; Sun, B.M.; Sun, M.Y. Reactivity and catalytic effect of coals during combustion: Thermogravimetric analysis. Energy 2024, 291, 130353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, C.; Wen, L.; Zhang, S.; Bai, C.; Yin, G. Evaluation of catalytic combustion of pulverized coal for use in pulverized coal injection (PCI) and its influence on properties of unburnt chars. Fuel Proc. Technol. 2014, 119, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Hu, J.; Heslop, M.J. Catalytic combustion of pulverized coal injected into a blast furnace and its industrial test. Adv. Mat. Res. 2010, 113–116, 1766–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.H.; Zhang, N.; Yang, T.H. Effects of alkaline earth metal on combustion of pulverized coal. Adv. Mat. Res. 2012, 516–517, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas, D.; Pecchi, G.; Rodríguez, V.; Fierro, J.L.G. Effect of potassium on sol-gel cerium and lanthanum oxide catalysis for soot combustion. Mod. Res. Catal. 2015, 4, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tultabayev, M.C.; Shoman, A.; Zhunusova, G.S.; Rabiga, K. Application of the emulsion for use in safflower oil in the coal industry. Rus. Coal. J. 2023, 9, 40–45. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollo, M.; Kolesnikov, A.; Makgato, S. Simultaneous reduction of NOx emission and SOx emission aided by improved efficiency of a Once-Through Benson Type Coal Boiler. Energy 2022, 248, 123551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Maly, P.; Brooks, J.; Nareddy, S.; Swanson, L.; Moyeda, D. Design and Test Furnace Sorbent Injection for SO2 Removal in a Tangentially Fired Boiler. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2009, 27, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, Z.; Wang, C.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, X. Experimental study on the inhibitory effect of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) on coal spontaneous combustion. Fuel Process. Technol. 2018, 178, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wang, X.; He, Y.; Weng, W.; Wang, Z. Study on ignition characteristics of single biomass and coal particles in ammonia co-firing. J. Energy Inst. 2024, 115, 101706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirbas, A. Biomass resource facilities and biomass conversion processing for fuels and chemicals. Energy Conv. Manag. 2001, 42, 1357–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKendry, P. Energy production from biomass (Part 1): Overview of biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 2002, 83, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, P. Biomass Gasification and Pyrolysis: Practical Design and Theory; Academic Press: Burlington, VT, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bhuiyan, A.A.; Blicblau, A.S.; Islam, A.S.; Naser, J. A review on thermo-chemical characteristics of coal/biomass co-firing in industrial furnace. J. Energy Inst. 2018, 91, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltschmitt, M.; Hartmann, H.; Hofbauer, H. Energy from Biomass: Fundamentals, Techniques and Applications (Energie aus Biomasse: Grundlagen, Techniken und Verfahren, in German); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; Available online: https://www.amazon.pl/Energie-aus-Biomasse-Grundlagen-Techniken/dp/3662474379 (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Kanwal, F.; Ahmed, A.; Jamil, F.; Rafiq, S.; Ayub, H.M.U.; Ghauri, M.; Khurram, M.S.; Munir, S.; Inayat, A.; Abu Bakar, M.S.; et al. Co-combustion of blends of coal and underutilised biomass residues for environmentally friendly electrical energy production. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidur, R.; Abdelaziz, E.A.; Demirbas, A.; Hossain, M.S.; Mekhilef, S. A review on biomass as a fuel for boilers. Renew. Sust. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 2262–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, B.; Chen, M.; Gao, Y.; Cao, C.; Wei, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Li, L. Investigation on the co-combustion characteristics of multiple biomass and coal under O2/CO2 condition and the interaction between different biomass. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 322, 115812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galina, N.R.; Romero Luna, C.M.; Arce, G.L.A.F.; Ávila, I. Comparative study on combustion and oxy-fuel combustion environments using mixtures of coal with sugarcane bagasse and biomass sorghum bagasse by thermogravimetric analysis. J. Energy Inst. 2019, 92, 741–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Abu Bakar, M.S.; Hamdani, R.; Park, Y.K.; Lam, S.S.; Sukri, R.S.; Hussain, M.; Majeed, K.; Phusunti, N.; Jamil, F.; et al. Valorization of underutilized waste biomass from invasive species to produce biochar for energy and other value-added applications. Environ. Res. 2020, 186, 109596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillman, D.A. Biomass cofiring: The technology, the experience, the combustion consequences. Biomass Bioenergy 2000, 19, 365–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A.B.; Jones, J.M.; Chaiklangmuang, S.; Pourkashanian, M.; Williams, A.; Kubica, K.; Andersson, J.T.; Kerst, M.; Danihelka, P.; Bartle, K.D. Measurement and prediction of pollutant emission from combustion of coal and biomass in a fixed bed furnace. Fuel 2002, 81, 571–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Lee, Y.J.; Yu, J.L.; Jeon, C.H. Improvement in reactivity and pollutant emission by co-firing of coal and pretreated biomass. Energy Fuels 2019, 33, 4331–4339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, L.L. Biomass-coal co-combustion: Opportunity for affordable renewable energy. Fuel 2005, 84, 1295–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokni, E.; Ren, X.; Panahi, A.; Levendis, Y.A. Emissions of SO2, NOx, CO2, and HCl from co-firing of coals with raw and torrefied biomass fuels. Fuel 2018, 211, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sami, M.; Annamalai, K.; Wooldridge, M. Co-firing of coal and biomass fuel blends. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2001, 27, 171–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katerla, J.; Sornek, K. Biomass for Residential Heating: A Review of Technologies, Applications, and Sustainability Aspects. Energies 2025, 18, 5857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuikov, A.; Glushkov, D.; Pleshko, A.; Grishina, I.; Chicherin, S. Co-combustion of coal and biomass: Heating surface slagging and flue gases. Fire 2025, 8, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaouki, G.; Janajreh, I. CFD analysis of the effects of co-firing biomass with coal. Energy Conv. Manag. 2010, 51, 1694–1701. [Google Scholar]

- Chaiyo, R.; Wongwiwat, J.; Sukjai, Y. Numerical and experimental investigation on combustion characteristics and pollutant emissions of pulverized coal and biomass co-firing in a 500 kW burner. Fuels 2025, 6, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazagic, A.; Hodzic, N.; Metovic, S. Co-combustion of low-rank coal with woody biomass and miscanthus: An experimental study. Energies 2018, 11, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]