Abstract

With the advancement of the “dual carbon” goal, the power system is accelerating its transition towards a clean and low-carbon structure, with a continuous increase in the penetration rate of renewable energy generation (REG). However, the volatility and uncertainty of REG output pose severe challenges to power grid operation. Traditional distribution networks face immense pressure in terms of scheduling flexibility and power supply reliability. Active distribution networks (ADNs), by integrating energy storage systems (ESSs), soft open points (SOPs), and demand response (DR), have become key to enhancing the system’s adaptability to high-penetration renewable energy. This work proposes a DR-aware scheduling strategy for ESS-integrated flexible distribution networks, constructing a bi-level optimization model: the upper-level introduces a price-based DR mechanism, comprehensively considering net load fluctuation, user satisfaction with electricity purchase cost, and power consumption comfort; the lower-level coordinates SOP and ESS scheduling to achieve the dual goals of grid stability and economic efficiency. The non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm III (NSGA-III) is adopted to solve the model, and case verification is conducted on the standard 33-node system. The results show that the proposed method not only improves the economic efficiency of grid operation but also effectively reduces net load fluctuation (peak–valley difference decreases from 2.020 MW to 1.377 MW, a reduction of 31.8%) and enhances voltage stability (voltage deviation drops from 0.254 p.u. to 0.082 p.u., a reduction of 67.7%). This demonstrates the effectiveness of the scheduling strategy in scenarios with renewable energy integration, providing a theoretical basis for the optimal operation of ADNs.

1. Introduction

Driven by the “dual carbon” goal, the power system is rapidly evolving towards a cleaner, low-carbon, and more efficient structure, with the grid-connected proportion of renewable energy such as photovoltaic (PV) and wind turbine (WT) continuously rising [1,2,3]. However, the strong volatility and uncertainty of renewable energy output have placed unprecedented pressure on traditional distribution networks in terms of scheduling flexibility and power supply reliability [4,5]. Consequently, active distribution networks (ADNs) have emerged as a research focus. Their core objective is to enhance the grid’s adaptability to high-penetration renewable energy and achieve source–grid–load–storage coordinated optimization via energy storage systems (ESSs) [6], soft open points (SOPs) [7], and demand response (DR) [8,9].

Compared with traditional distribution networks, ADNs emphasize win–win interactions between users and the grid. DR in the electricity market can be categorized into two types. One type uses interruptible contracts to compensate large industrial users for peak-period load curtailment; the other leverages price elasticity to guide users in adjusting electricity consumption timing via time-of-use (TOU) pricing. This enables peak shaving and valley filling without increasing total electricity consumption, effectively mitigating net load fluctuations induced by distributed generation (DG) integration.

The realization of carbon neutrality requires the efficient utilization of renewable energy. Since renewable energy is volatile, random, and intermittent, adequate energy storage is needed to redistribute energy spatially and temporally [10]. ESSs can not only smooth the fluctuation of renewable energy output but also improve grid flexibility and stability, making it a central component of ADN development [11].

To improve ESS utilization efficiency, reference [12] constructed a robust optimization model for fixed and mobile energy storage in bidirectional ADNs, which coordinates spatial–temporal flexibility to reduce costs and losses. Reference [13] proposed a two-stage decentralized trading framework for microgrid-integrated systems, using peer-to-peer (P2P) trading and shared energy storage for fluctuation suppression in the day-ahead stage. Meanwhile, a consensus Newton algorithm for real-time scheduling was designed, with asymmetric Nash bargaining to achieve fair profit distribution; reference [14] proposed a two-stage battery energy storage optimization (site selection followed by capacity determination) for high-PV-penetration scenarios, which significantly reduces curtailment. Reference [15] adopted a multi-objective particle swarm optimization algorithm to optimize the combination of mobile and fixed energy storage, balancing operator revenue and fault load loss, with the hybrid scheme exhibiting distinct advantages in peak shaving, fluctuation suppression, and system resilience. Reference [16] proposed an optimization model for a hybrid system integrating PV, combining heat and power (CHP), batteries, and gas boilers and incorporating electric vehicle charging, incentive-based DR, and net metering, with the aim to minimize the full-life-cycle cost and significantly improve the economy, low carbonization, and resilience of multi-residential complex buildings. However, most of these studies prioritize grid economy and stability while paying insufficient attention to users’ electricity purchase satisfaction and consumption comfort.

As the power system moves towards intelligence and low carbonization [17], the coordinated optimization of DR and ESS is critical to improving grid economy and stability. Peak–valley TOU pricing, as an important tool for demand-side management, plays a crucial role in guiding users to optimize electricity consumption structure and enhancing system operation efficiency [18].

In this context, existing studies have explored the coordination mechanism between ESS and DR from various perspectives. Reference [8] studied the site selection and capacity determination of an electricity–hydrogen hybrid energy storage system in ADNs, balancing net load fluctuation and investment costs. Reference [18] proposed a three-layer optimization model integrating price-based and incentive-based DR for data center load characteristics, optimizing energy storage configuration and scheduling to balance economy and response benefits. Reference [19] constructed an operation optimization model considering multi-load response (electricity, heat, and gas) under the framework of regional integrated energy systems, improving economy and renewable energy utilization efficiency. Although the joint dispatching mechanism of DR and ESS has achieved certain results in relevant studies, the ESS configuration in existing schemes is mostly limited to temporal energy peak shaving and valley filling. The energy complementarity potential in the spatial dimension has not been fully exploited, making it difficult for the synergistic effect of DR and ESS to overcome spatiotemporal constraints.

In addition, SOPs can effectively mitigate the impact of renewable energy on the grid [20]. Unlike the energy time-shifting of ESSs in the time dimension, SOPs enable active–reactive power flow control between feeders through energy transfer in the spatial dimension, thereby achieving load flow balance and system voltage distribution optimization. Composed of back-to-back voltage source converters (B2B-VSCs), unified power flow controllers (UPFCs), and static synchronous series compensators (SSSCs), SOPs are installed at key nodes of distribution networks to realize the joint regulation of active and reactive power, thus improving voltage quality and system flexibility [21]. During normal operation, SOPs adjust feeder power through fully controlled power electronic devices, reducing the risk of voltage violation and network losses [22]. To improve SOP operation efficiency, reference [23] proposed a decentralized control strategy based on voltage–power sensitivity. Reference [24] proposed a flexible interconnected distribution network topology with an embedded DC system and established a dynamic reconfiguration model involving switch states and continuous adjustment of flexible interconnection devices to achieve the coordinated optimal economic operation of sources, networks and loads. However, these studies insufficiently consider DR mechanisms, making it difficult to fully exploit the synergistic benefits of SOPs and DR.

Existing studies have made progress in DR, ESS, and SOPs. However, DR-ESS collaborative optimization is mostly confined to temporal energy time shifting without integrating spatial power flow regulation, restricting collaborative effects and energy efficiency due to spatiotemporal limitations. To tackle this, this paper adds SOPs to DR-ESS collaboration, forming a three-dimensional DR-ESS-SOP mechanism for mutual complementarity: SOPs compensate for ESS’s poor spatial energy transmission flexibility via inter-feeder active/reactive power regulation and spatial power flow optimization, while ESS offsets SOPs’ inability to store/release cross-period energy and suppress temporal load fluctuations via “valley charging, peak discharging”, creating a spatiotemporally linked complementary mode.

Moreover, most existing studies focus on a single stakeholder (either grid or user side) without a win–win framework. Thus, besides ensuring grid stability and economy, this paper integrates user electricity comfort and purchase satisfaction into the optimization system, achieving a balanced win–win for both sides via price signal guidance and multi-objective modeling.

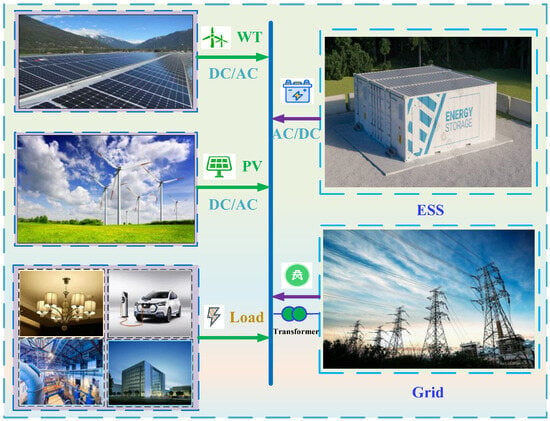

This paper takes realizing win–win outcomes for multiple stakeholders in the “source–grid–load” system and improving the operational stability and economic efficiency of the ADN as the core objectives, and establishes a bi-level scheduling model for the ESS-SOP considering DR. The upper level introduces a price-based DR mechanism, comprehensively considering net load fluctuation, user electricity purchase costs, and power consumption comfort. The lower-level coordinates ESS and SOP scheduling to achieve the dual goals of grid stability and economic efficiency. Figure 1 illustrates the WT-PV-ESS system for power generation, transmission, distribution, and consumption. The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

Figure 1.

Schematic of power generation, transmission, distribution, and consumption in a WT−PV−ESS system.

- (1)

- A flexible distribution network scheduling framework integrating price incentives, ESS, and SOP is proposed, which deeply combines the spatial dynamic power flow regulation of SOP with the price incentive mechanism of TOU pricing. ESS realizes energy transfer in the time dimension by “charging at valley and discharging at peak” to smooth cross-time load fluctuations; SOP optimizes power distribution in the spatial dimension through active/reactive power regulation between feeders, making up for the deficiency of ESS in terms of spatial transmission flexibility. The two form a time–space complementary collaborative mode, and cooperate with DR to guide users to adjust their electricity consumption behaviors, ultimately achieving two-way interaction between user-side response and grid-side scheduling.

- (2)

- A two-layer optimization model balancing the interests of both the power grid and user sides is constructed, which gives full play to the value of the coordinated dispatching of ESS and SOP. The model realizes the linkage between the upper and lower layers through price signals, which not only improves the stability and economy of power grid operation but also balances the economy of users’ electricity purchase and the comfort of electricity consumption, and finally achieves a mutually beneficial win–win situation between users and the power grid.

- (3)

- A systematic comparison is performed on the solution results of multi-objective optimization algorithms, such as the non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm III (NSGA-III), multi-objective particle swarm optimization (MOPSO), and multi-objective chaos game optimization (MOCGO), in the problems of DR and equipment-coordinated scheduling, thereby providing a reference for algorithm selection in similar high-dimensional nonlinear optimization scenarios.

This paper is structured as follows: Section 1 (Introduction) outlines the research background, shortcomings of existing studies, and main contributions; Section 2 (Upper-Level Optimization Model) presents a multi-objective optimization framework integrating DR and TOU; Section 3 (Lower-Level Optimization Model) focuses on the coordinated scheduling of ESS and SOPs; Section 4 (Model Solution) details the model solution process; Section 5 (Case Studies) discusses the tests conducted on the 33-node system and analyzes the results; and Section 6 (Conclusions) summarizes achievements, main conclusions, and future research directions.

2. Upper-Level Optimization Model

For upper-level optimization, this study integrates DR with the TOU mechanism, establishing a multi-objective optimization framework that synthetically accounts for net load fluctuation, user electricity purchase costs, and power consumption comfort. Through the introduction of a price elasticity matrix to characterize user response behavior to electricity price changes in different time periods, the peak–valley electricity price levels are dynamically adjusted to guide users in reasonably shifting electricity loads, thereby effectively smoothing the sharp changes in net load caused by renewable energy output fluctuation. It is worth noting that the DR mechanism adopted in this study formulates TOU tariffs on the basis of day-ahead load forecasts as well as wind and photovoltaic power generation prediction data. Specifically, the demarcation of TOU periods into peak, flat, and valley intervals, together with their corresponding electricity price levels, is predefined and formally promulgated to end-users in advance. With access to these pre-announced tariff signals, consumers adjust their power consumption schedules for the subsequent day accordingly. Thus, this mechanism is explicitly categorized as a day-ahead time-of-use pricing scheme.

2.1. TOU Model

When DGs cannot meet load demand, ADNs require supplementary power supply from the main grid [17]. Accordingly, managers can design a reasonable TOU mechanism to guide users to shift consumption through price signals, smooth the net load curve, and reduce the peak–valley difference.

where , , and are the electricity prices during peak, flat, and valley periods after implementing TOU, respectively; is the electricity price before implementing TOU; , , and are the electricity price fluctuations in each period; denotes time; and , , and represent peak, flat, and valley periods, respectively.

2.2. Electricity Quantity–Price Elasticity Matrix Model

Electricity price elasticity refers to the relative change in electricity demand induced by the relative change in electricity price. Specifically, within a specific time horizon, it is defined as the ratio of the rate of change in electricity consumption to the corresponding rate of change in electricity price. Since the determination of this elasticity curve poses considerable challenges, it is typically subjected to linearization in economic research [25].

Building on this basic definition, the electricity quantity–price elasticity matrix [26] further characterizes the cross-period impact of electricity price changes on users’ electricity consumption behavior. Specifically, users’ electricity consumption depends not only on the current electricity price of the current period but also on the coupling effect of price changes in other periods. To simplify the model, this study adopted the method of Reference [26], which does not consider the specificity of different user categories and assumes a unified demand price elasticity coefficient for all users. The specific mathematical expression is as follows:

where is the electricity consumption in period ; is the change in electricity consumption in period ; is the electricity price in period ; is the change in electricity price in period ; is the demand price elasticity coefficient; and subscripts and represent peak, flat, and valley periods ( {p, f, v}).

In the TOU model, the daily load is divided into three periods: peak, flat, and valley. After implementing TOU, the load changes in peak, flat, and valley periods are expressed as follows:

where , , and are the user’s electricity purchases from the main grid (represented by net load in this paper) during peak, flat, and valley periods before implementing TOU, respectively; , , and are the electricity prices before implementing TOU, all equal to ; , , and are the changes in electricity prices in each period; , , and are the load demand, PV output, and WT output, respectively; and the diagonal elements in the electricity quantity–price elasticity matrix are self-elasticity coefficients and the off-diagonal elements are cross-elasticity coefficients. Among them, the data of the electricity quantity–price elasticity matrix is derived from the literature [26], and the specific derivation process can be referenced from the literature [25].

2.3. Upper-Level Objective Function

2.3.1. Net Load Fluctuation Considering Demand Response

After DG integration into ADNs, the randomness of their output is prone to inducing net load fluctuation, threatening the system stability. With the introduction of the DR mechanism, users can adjust their electricity consumption behavior according to TOU signals, thereby smoothing load fluctuation and improving grid operation stability.

Given the short-term high-frequency fluctuation characteristics of DG output, this paper adopts the index of the sum of the square roots of net load differences between adjacent moments, which can more accurately quantify temporal continuous fluctuations and instantaneous fluctuations. For grid operators, it quantifies DG -induced load stability risks, supporting high-penetration DG integration. For users, it ensures reliable power supply by reducing voltage anomalies.

where is the cumulative sum of net load fluctuations at each time instant within the dispatch cycle after considering the DR mechanism; is the electricity purchase from the main grid after implementing TOU at time ; and is 24 h.

2.3.2. Purchasing Cost Satisfaction of User Electricity

TOU design must balance ADN stability with user economic affordability. Guided by price signals, users tend to increase electricity consumption during low-price valley periods and reduce it during high-price peak periods, thereby changing their electricity consumption timing. To quantify the effect of this economic incentive, this paper defines the user electricity purchase expense ratio as the ratio of total user electricity purchase expenses before and after implementing TOU and takes minimizing this ratio (i.e., maximizing user satisfaction) as the optimization objective. It reflects the economic benefits of users participating in demand response, serving as a key incentive for user behavior adjustment.

where denotes purchasing cost satisfaction of user electricity; is the electricity price after implementing TOU; and is the electricity purchase from the main grid before implementing TOU.

2.3.3. Power Consumption Habit Deviation

Before implementing TOU, users consume electricity freely according to their living habits, achieving the highest comfort; after being guided by price signals, users are forced to adjust their electricity consumption timing to reduce purchase costs, resulting in decreased comfort. To avoid excessive erosion of user experience by economic incentives, this paper defines the power consumption habit deviation as the ratio of the total deviation of the adjusted load from the original load to the total initial load and takes the minimization of this ratio (i.e., maximizing comfort) as the optimization objective. This indicator minimizes the comfort loss of users caused by adjusting electricity consumption patterns, ensuring the acceptability of the scheduling strategy.

where is the change in user electricity consumption. The denominator represents the total main grid power purchase volume over all time periods before TOU implementation.

2.4. Upper-Level Constraints

2.4.1. Total Load Constraint

The total load must remain consistent before and after implementing TOU.

2.4.2. Electricity Price Fluctuation Constraint

The electricity price fluctuation in each period must satisfy the following constraints:

where , , and are the minimum values of electricity price fluctuations during peak, flat, and valley periods, respectively; , , and are the maximum values of electricity price fluctuations during peak, flat, and valley periods, respectively; and represents the electricity price fluctuation in different periods.

3. Lower-Level Optimization Model

The integration of ESS and SOPs can significantly improve the consumption efficiency of renewable energy, but their value realization depends on refined operational and management strategies [27]. Therefore, the lower-layer model comprehensively considers grid economy and stability, synchronously optimizing ESS charging–discharging timing and power, as well as SOP power in each period, to achieve the coordinated operation of source–grid–storage–flexibility.

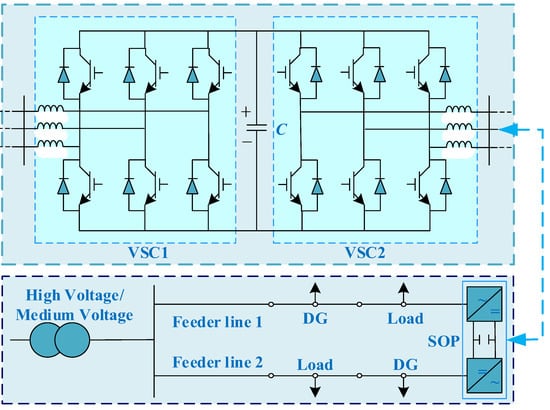

3.1. SOP Principle and Installation Location

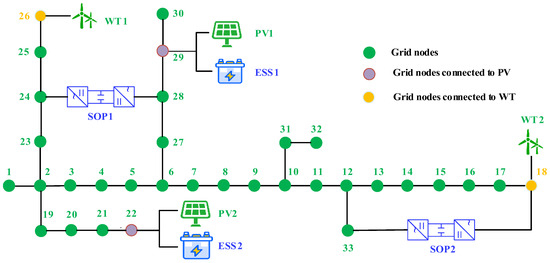

Under normal operating conditions, SOPs implement millisecond-level precise regulation of feeder power through fully controlled power electronic devices, effectively suppressing voltage violations and reducing network losses. This paper adopts SOPs with a B2B-VSC structure, deployed at the connection points of adjacent feeders to replace traditional mechanical section switches. Their topology and specific installation location are shown in Figure 2 [28].

Figure 2.

The installation location and structure of SOP.

3.2. Lower-Level Objective Function

3.2.1. Scheduling Net Revenue

To ensure the economic efficiency of power grid operation, this paper quantifies various costs and benefits of ESS and SOP scheduling, including the daily comprehensive cost of SOPs, the daily operating cost of ESS, and ESS arbitrage revenue and network loss reduction revenue.

The daily comprehensive cost of SOPs includes the daily investment cost and daily operation and maintenance cost of SOPs, according to the following specific formulas [29]:

where denotes the set of adjacent nodes of node ; is the unit capacity investment cost of SOPs; is the capacity of SOPs installed between node and node ; is the service life of SOPs; and is the annual operation and maintenance cost coefficient of SOPs.

A key factor in the operation of ESS is the operating cost, most of which comes from the loss of batteries under repeated charge–discharge cycles [30]. Different batteries exhibit different loss characteristics. This paper focuses on lithium-ion batteries, which are one of the most popular batteries in practical applications today. This paper adopts the method from reference [31] to characterize the attenuation degree of lithium batteries using linear coefficients. The specific expression for the battery degradation cost is as follows:

where is the unit charging–discharging power maintenance cost of ESS; and are the charging and discharging powers of the -th ESS, respectively (charging is negative, discharging is positive); is the maximum number of cycles; is the battery cell price; and and are the upper and lower limits of SOC, respectively.

ESS arbitrage revenue stems from the charging–discharging strategy driven by TOU differences, and its economic benefits are quantified by the following formula:

where denotes TOU pricing, and is the number of ESSs.

Network loss reduction revenue comes from the reduction in network losses achieved through power flow regulation. Its economic value can be calculated as [31]

where and are the power losses of the -th branch at time before and after optimization, respectively, and is the number of grid branches.

The scheduling net revenue in this paper is defined as the sum of ESS arbitrage revenue and network loss reduction revenue minus the daily comprehensive costs of ESS and SOPs. The specific mathematical expression is as follows:

where denotes the scheduling net revenue; is the ESS arbitrage revenue; is the network loss reduction revenue; is the daily operating cost of ESS; and is the daily comprehensive cost of SOPs.

3.2.2. Voltage Deviation

To ensure the stability of power grid operation, voltage stability is a core indicator—RE integration and load fluctuation easily cause node voltage deviations from the rated value, threatening system safe operation and power supply quality. This objective quantifies the overall voltage stability by calculating the time-series average of the sum of squared deviations between the voltage of all nodes and the rated voltage during the scheduling period [32].

The optimization objective is to minimize this value, ensuring that node voltages are constrained within the allowable range and maintaining grid stability:

where represents the time-series average value of the sum of the squared deviations between the voltage of all nodes in the distribution network and the rated voltage during the scheduling period, which is used to quantify the overall fluctuation degree of the voltage across all nodes throughout the entire scheduling period; is the number of grid nodes; is the voltage of the -th node at time ; and is the average voltage.

3.3. Lower-Level Constraints

3.3.1. SOP Operation Constraints [33]

SOP operation constraints aim to ensure that SOP operates within safe and effective limits. It is noted that the operation efficiency of SOPs can reach 98%; thus, we ignore the power losses of SOPs in this planning problem [34]. The specific mathematical expressions are as follows:

where is the rated capacity of SOPs; and are the active power injected by node and node through the SOPs at time , respectively; and are the reactive power injected by node and node , respectively, through the SOP at moment ; and , and , are the upper and lower bounds of the reactive power injected by the SOPs at node and node , respectively.

3.3.2. Distribution Network Operation Constraints

Distribution network operation constraints help prevent overvoltage or undervoltage and line overload, thereby ensuring the stable operation and power supply safety of the distribution network. The specific mathematical expressions are as follows:

where and are the active and reactive power injected at node at moment , respectively; denotes the summation of all nodes that are physically directly connected to node ; and are the voltage magnitude at node at moment and the phase angle difference between nodes and its phase angle difference with ; , and , are, respectively, the node conductance matrices of the self-conductance, self-conductance and mutual-conductance, mutual-conductance; is the predicted value of DG output active power; and are the active and reactive power output from the DG at node in time period , respectively; and are the active and reactive power injected by the load at node before time period ; and are the upper and lower limits of the voltage amplitude at node , respectively; and are the upper and lower limits of the branch’s current amplitude at time , respectively; and and are the power factor angles of the DG at node at time , respectively.

3.3.3. ESS Operating Constraints

The safe and efficient operation of ESS must comply with the constraints of charging–discharging power and state of charge (SOC) [35]. The specific constraints are as follows:

where is the rated power of the -th ESS; is the SOC of the -th ESS at time ; and are the charging and discharging efficiencies, respectively; and is the rated capacity of the -th ESS.

3.3.4. Power Balance

Maintaining power balance [36] is a core condition for ensuring stable system operation, and it has the following mathematical expression:

where is the power supply of the grid; is the power loss; and are the output powers of PV and WT, respectively; is the load demand; and and are the numbers of PV and WT units, respectively.

3.3.5. Timing Constraints

To ensure the efficiency and orderliness of ESS operation, this paper introduces a time constraint mechanism throughout its charging–discharging process. This mechanism covers the start and end times of charging–discharging and the time boundary of the entire scheduling cycle. The specific mathematical formula is as follows:

where and are the start and end times of the -th charging-discharging cycle, respectively, and is defined as the maximum allowable number of charge-discharge cycles within the full service life of a battery.

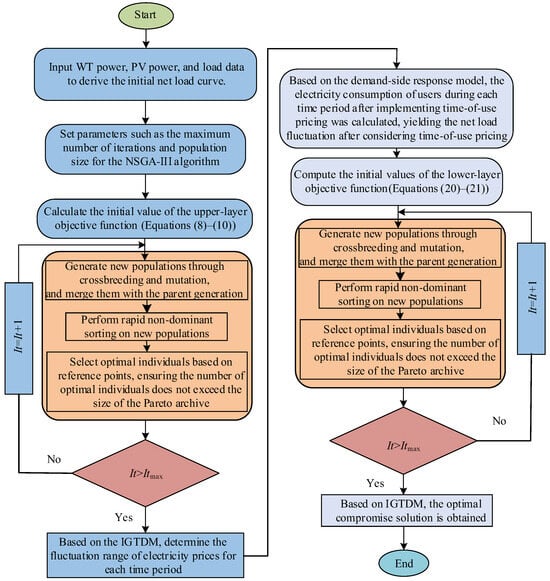

4. Model Solution Based on NSGA-III-IGTDM

4.1. Multi-Objective Optimization Model Solution Based on NSGA-III

The ESS optimization strategy is essentially a high-dimensional, nonlinear, multi-objective decision-making problem, involving the optimization of ESS charging–discharging periods and power, as well as ESS operation constraints, timing constraints, and power balance constraints. NSGA-III guides population evolution through reference points, enabling the generation of more uniform Pareto solutions with a wider coverage range. This facilitates the screening of balanced solutions in engineering that take into account economy, stability, and user needs. Meanwhile, its convergence mechanism is more stable, which can avoid falling into local optima in the nonlinear coupling objectives of distribution networks (such as network loss and voltage deviation). Additionally, it has stronger robustness in constraint handling, making it suitable for solving the model in this paper. Therefore, this study adopted the NSGA-III algorithm [37] to solve the model and generate the Pareto front and used an improved IGTDM decision-making mechanism to perform preference trade-off on the non-dominated solution set. The model solution process based on NSGA-III-IGTDM is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Flowchart of the NSGA-III-IGTDM-based model solution.

4.2. Trade-Off Solution Selection Based on IGTDM

After completing the multi-objective solution with NSGA-III, decision-makers need to select the most engineering-feasible solution from the Pareto front. However, the front solutions are scattered in the objective space and mutually non-dominated, making it easy to introduce cognitive biases and uncertainties when relying solely on subjective preferences. To improve the objectivity and scientificity of decision-making, this paper introduces improved gray target decision-making (IGTDM) to perform preference trade-off on the non-dominated solution set, with the selection process described as follows.

4.2.1. Construction of the Sample Data Matrix

4.2.2. Determining the Target Center

In this paper, the negative value of net revenue is selected as the objective function. Given this, both voltage fluctuation and the negative value of net revenue are classified as cost-type indicators. Based on the above considerations, the cost indicator formula is used to construct the decision matrix. The target center is identified within the gray decision space defined by the decision matrix, calculated as follows:

where is the operator of the -th objective function; is the -th sample value of the o-th non-dominated solution; is the -th decision value of the o-th non-dominated solution; is the decision matrix; and is the target center of the -th objective function.

4.2.3. Selecting the Optimal Trade-Off Solution

To calculate the distance from the solution set to the target center, the entropy value of each solution needs to be determined. The specific mathematical expression is as follows:

The distance between each solution and the target center is calculated, and the solution with the minimum distance is selected as the optimal decision. The specific mathematical expression is given as follows:

where is the entropy value of the -th objective function; is the entropy weight of the -th objective function; denotes the value of the o-th non-dominated solution; denotes the target center; and is the distance from the o-th non-dominated solution to the target center.

5. Case Studies

5.1. Test System

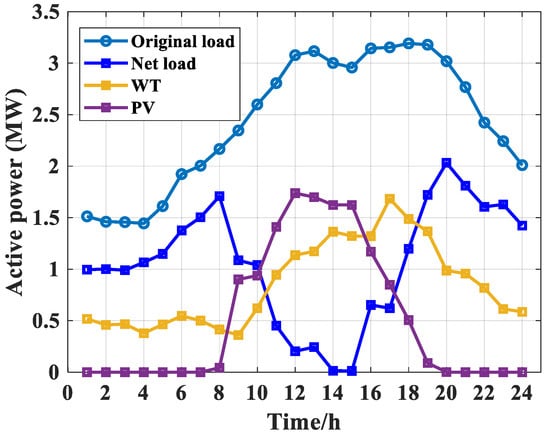

The case study in this paper adopts the standard 33-node power grid system for verification. The power output curves of net load, WT, and PV are shown in Figure 4. The grid topology and the installation locations of SOPs and ESS are shown in Figure 5. Here, WTs were located at nodes 18 and 26, PVs were located at nodes 22 and 29, SOP1 was installed between nodes 24 and 28, and SOP2 was installed between nodes 18 and 33. To compare the performance differences of different algorithms, this study used NSGA-III, MOPSO, and MOCGO to solve the model, and the algorithm parameters are listed in Table 1. The rated power of the ESS wasw 300 kW, the rated capacity was 1200 kWh, the charging and discharging efficiencies were both 0.98, and the SOC allowable range was [0.1, 0.9]. The voltage limits of the test system nodes was [0.97, 1.03] p.u.

Figure 4.

Original load, net load, WT, and PV output curves.

Figure 5.

Schematic of grid topology.

Table 1.

Related parameters of each algorithm.

5.2. Analysis of Upper-Layer Model Results

Table 2 shows the optimization results of three multi-objective optimization algorithms (NSGA-III, MOCGO, and MOPSO) in the upper-layer model. Under the 33-node test system and parameter settings outlined in Table 1, the MOCGO algorithm achieves the optimal performance in the electricity purchase cost objective function, reducing the electricity purchase cost by 12% compared to the pre-scheduling scenario. This is primarily attributed to its more aggressive peak–valley pricing strategy (see Table 3; the peak-time electricity price reaches 1.57 CNY/kWh), which strongly encourages users to shift their electricity consumption periods to maximize economic benefits. In terms of net load fluctuation, both MOCGO and NSGA-III reduce the fluctuation from 5.71 MW to 5.25 MW, a reduction of 8.1%, which is better than MOPSO’s 5.57 MW. However, MOCGO’s power consumption habit deviation is 6.07 × 10−4 p.u., which is significantly higher than NSGA-III’s 3.15 × 10−4 p.u. This indicates that its cost advantage is achieved at the cost of user comfort under the current optimization conditions.

Table 2.

Optimization results of the upper model.

Table 3.

TOU results of different algorithms.

From the perspective of multi-objective trade-off, NSGA-III shows more balanced optimization capabilities under the selected test conditions. Its user electricity purchase expense ratio decreases by 8.0%, which is slightly higher than MOCGO, while achieving the same net load fluctuation reduction and significantly better comfort, hence achieving the best balance between grid stability, economy, and user satisfaction for the upper-layer model’s optimization objectives. MOPSO performs the worst across all indicators, highlighting the superior balance and engineering feasibility of the NSGA-III algorithm in demand response design under the current parameter configuration and problem constraints.

5.3. Analysis of Lower-Layer Model Results

5.3.1. Performance Comparison of Different Algorithms

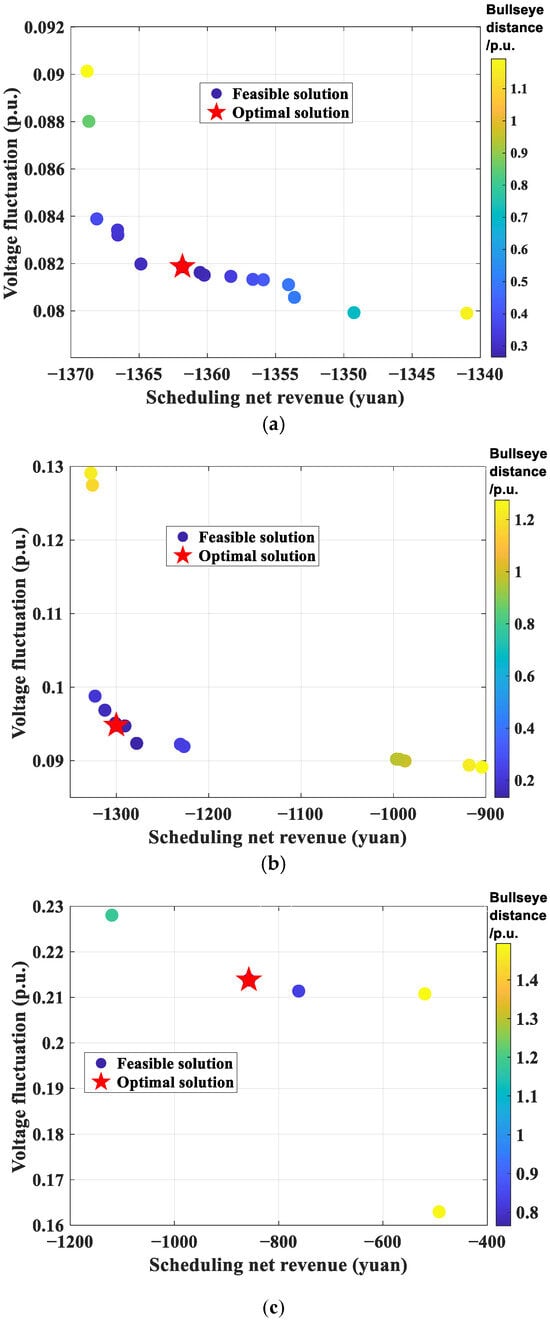

Figure 6 shows the Pareto fronts of different algorithms. There is an obvious Pareto trade-off relationship between voltage fluctuation and optimized net revenue. After generating the Pareto front, an IGTDM decision model with entropy weighting is further introduced to determine the optimal trade-off solution (i.e., the solution with the minimum distance to the target center), so as to achieve the quantitative balance of conflicting objectives.

Figure 6.

Pareto fronts of different algorithms: (a) NSGA-III; (b) MOPSO; (c) MOCGO.

As shown in Table 4, under the standard 33-node test system and parameter settings listed in Table 1, NSGA-III demonstrates superior overall performance: the voltage range is narrowed to [0.979, 1.007] p.u., the voltage deviation is reduced to 0.082 p.u., the net revenue reaches 1361.8 yuan, and the network loss is lowered to 0.480 MW. Although the MOPSO algorithm is close to NSGA-III in economy (net revenue of CNY 1300.0), its voltage deviation is 0.095 p.u. and network loss is 0.491 MW, indicating that its scheduling strategy is slightly biased towards economy at the expense of partial stability in this test scenario. In contrast, MOCGO performs poorly, with higher voltage deviation (0.213 p.u.) and network loss (0.509 MW), and a net revenue of only CNY 857.2. This reflects that in the high-dimensional nonlinear constraint scenario of this study, MOCGO’s search mechanism may make it more prone to falling into local optimality, making it difficult to coordinate multi-objective conflicts. The Pareto fronts in Figure 6 further illustrate the distribution characteristics of the algorithms in the objective space (net revenue vs. voltage deviation). The solution set of NSGA-III is uniformly distributed in the front area, covering a net revenue range of CNY 1340–1370 and a voltage deviation range of 0.08–0.10 p.u., reflecting desirable solution set diversity for the 33-node system optimization problem. The solution set of MOPSO is concentrated on the high voltage deviation side (0.09–0.12 p.u.). Although the net revenue can reach CNY 1200–1300, the lack of solution set diversity limits decision flexibility. The solution set of MOCGO is scattered and far from the ideal point, with several solutions being close to the pre-optimization level, highlighting limitations in global search capability under the current parameter and problem-scale settings. Through comparison, it can be seen that the Pareto front of NSGA-III is closer to the ideal point, providing decision-makers with high-quality solution sets that balance economic benefits and voltage stability.

Table 4.

Solution results of different algorithms in the lower layer.

5.3.2. Economic Analysis

As shown in Table 4, in terms of economic benefits, scheduling revenue comes from two parts: one is ESS arbitrage revenue, which is realized through the difference between valley-time charging costs and peak-time discharging income; the other is revenue from reducing grid network losses. Further analysis of Table 4 shows that scheduling revenue mainly comes from arbitrage income. Taking the optimization results of NSGA-III as an example, arbitrage accounts for 94.1% of the total income, indicating that it is the dominant source of economic gain.

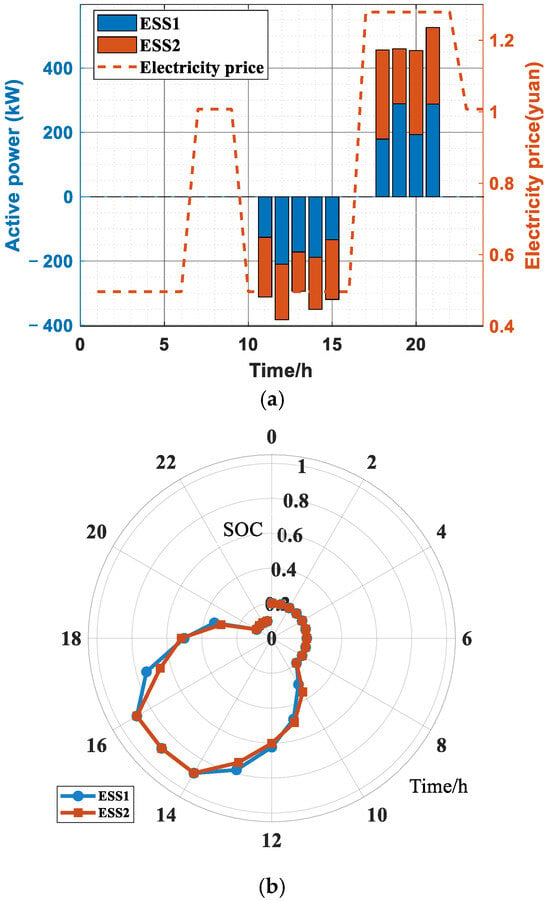

As shown in Figure 7a, the TOU curve presents a typical “peak–valley–flat” characteristic. The peak-time price (17:00–22:00) is as high as 1.28 CNY/kWh, while the valley-time price (01:00–06:00 and 10:00–16:00) drops to 0.50 CNY/kWh. This price structure effectively guides the charging–discharging behavior of ESS: during valley periods, ESS stores electricity (the charging power is continuously negative during 11:00–15:00), and the SOC rises rapidly (as shown in Figure 7b); during peak periods, ESS switches to the discharging mode (the discharging power is positive during 18:00–21:00), and the SOC gradually decreases. This strategy reflects the ESS arbitrage mechanism of “charging at low prices and discharging at high prices”, realizing economic gains through price differences.

Figure 7.

Electricity price and ESS scheduling strategy diagrams: (a) electricity price and ESS power change diagram; (b) ESS SOC change diagram.

5.3.3. Stability Analysis

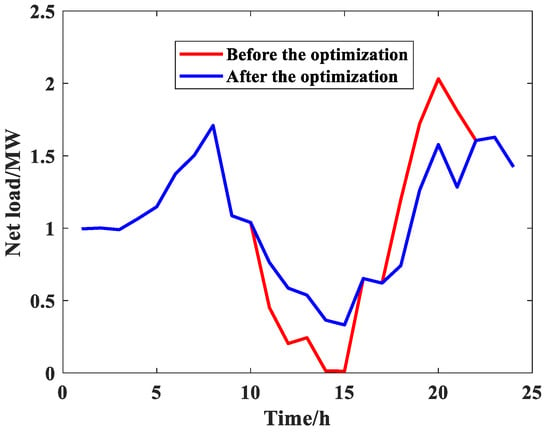

The integration of high-proportion renewable energy exacerbates the operational uncertainty of ADNs. The volatility and randomness of their output directly lead to sharp fluctuations in the net load curve. As shown in Figure 8, the peak–valley difference in the original net load is as high as 2.020 MW, which not only increases grid line losses but also poses a severe challenge to voltage stability.

Figure 8.

Comparison of net load curves before and after scheduling.

As shown in Figure 8, the ESS effectively achieves peak shaving and valley filling through the “charging at low prices and discharging at high prices” strategy. The optimized net load curve exhibits a smooth profile: absorbing excess renewable energy power during low-load periods (e.g., 10:00–16:00) and releasing stored energy to support grid demand during peak periods (e.g., 17:00–21:00). This reduces the net load peak–valley difference from 2.020 MW to 1.377 MW, a reduction of 31.8%, effectively mitigating the power fluctuation issues induced by renewable energy output variability.

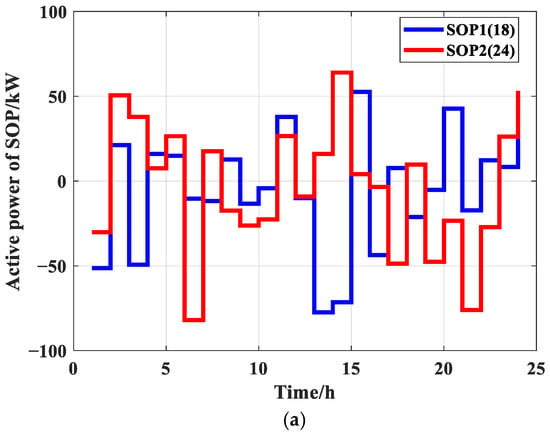

Figure 9 shows the power output changes in SOPs within 24 h. It can be seen from that SOPs can dynamically adjust power to achieve the optimal spatial distribution of power flow. This regulation mechanism balances the power of different nodes, effectively reducing system network losses and voltage fluctuations. To a certain extent, it remedies the shortcomings of ESS that cannot be adjusted due to capacity and mobility, thereby improving the overall operational efficiency of the system.

Figure 9.

Power change diagrams of SOPs: (a) active power; (b) reactive power.

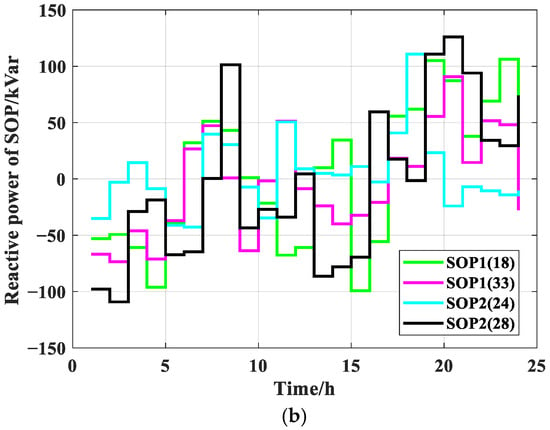

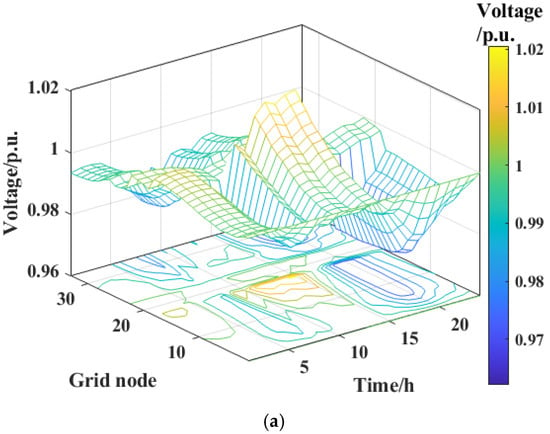

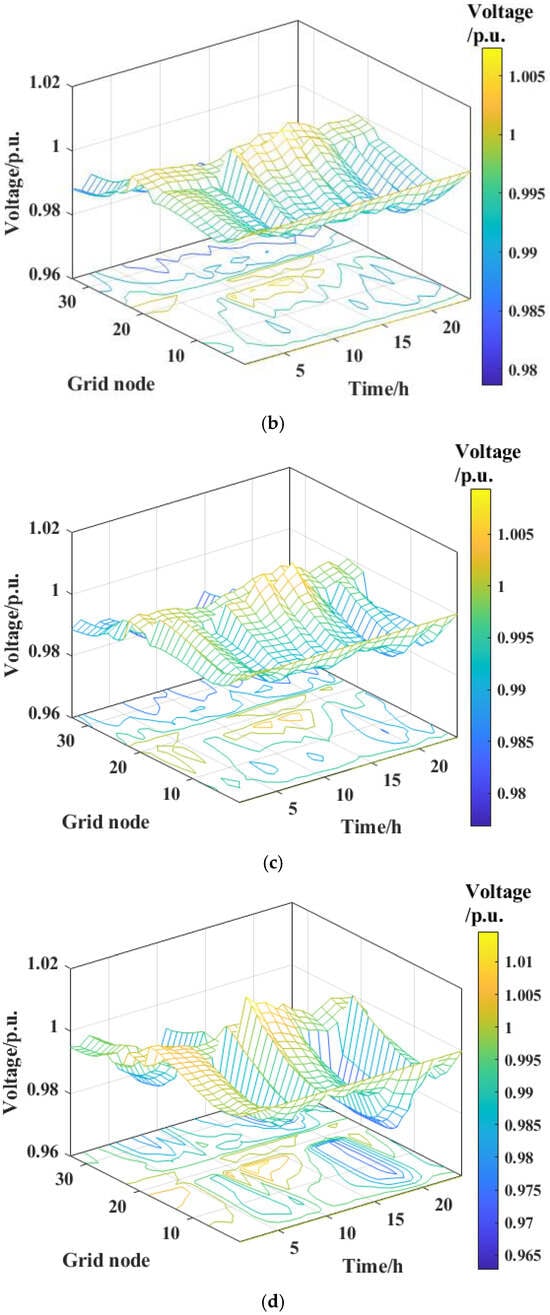

Figure 10 shows the node voltage distributions after optimization with different algorithms. Compared with the pre-optimization condition, the voltage distributions are more concentrated, and the overall voltage quality has been significantly improved, with the effect under the NSGA-III algorithm being the most prominent.

Figure 10.

Comparison of node voltages after optimization with different algorithms: (a) before optimization; (b) NSGA-III; (c) MOPSO; (d) MOCGO.

As shown in Figure 10a, before optimization, the system voltage range is wide (0.962–1.021 p.u.). Some nodes face the risk of voltage violation (>1.03 p.u.) during 10:00–14:00 due to high PV penetration, while undervoltage (<0.97 p.u.) occurs in load-concentrated areas during 16:00–22:00. After scheduling optimization, as shown in Figure 10b, the voltage fluctuation range is narrowed to 0.979–1.007 p.u., the voltage deviation is reduced from 0.254 p.u. to 0.082 p.u. (a reduction of 67.7%), and all node voltages are strictly constrained within the allowable limits. This result highlights the improvement effect of scheduling optimization on voltage quality.

6. Conclusions

To address the stability and economic challenges posed by renewable energy grid integration, this study proposes a bi-level optimal scheduling strategy for ESS-integrated flexible distribution networks considering demand response. By constructing upper-layer demand response and lower-layer ESS-integrated flexible distribution network scheduling models, multiple objectives such as user satisfaction, grid economy, and stability are effectively balanced. The main conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- Under the condition of unchanged daily electricity consumption, the upper-layer model guides users to reduce consumption during high-price periods and increase consumption during low-price periods through the TOU mechanism, achieving the temporal shifting of peak–valley loads. This strategy not only enhances the operational stability of ADNs but also improves the economy of user electricity purchases, reflecting the efficiency of source–grid–load interaction.

- (2)

- Based on the upper-layer optimization results, the lower-layer model employs the ESS “charging at low prices and discharging at high prices” strategy to effectively smooth the net load curve, reducing grid network losses and voltage deviation. After optimization, the net load peak–valley difference decreases from 2.020 MW to 1.377 MW, a reduction of 31.8%; at the same time, the voltage deviation drops from 0.254 p.u. to 0.082 p.u., a reduction of 67.7%, effectively improving grid economy and power supply quality.

- (3)

- Under the framework of the test system and algorithm parameter settings in this paper, in the upper-layer model solution, although the MOCGO algorithm is optimal in electricity purchase satisfaction, user comfort is poor. In contrast, the NSGA-III algorithm achieves equivalent net load fluctuation suppression while providing a more balanced performance in multi-objective trade-off. In the lower-layer model solution, the NSGA-III algorithm outperforms the MOCGO and MOPSO algorithms across all indicators, verifying its superiority in high-dimensional nonlinear problems.

Although the model proposed in this paper exhibited certain progress in improving the operational efficiency and stability of power systems, it still has the following limitations that need further improvement:

- (1)

- The elasticity matrix used in the current research is overly simplified and fails to consider the heterogeneity of demand response among different user types, which may easily lead to deviations between the effect of demand response guidance and the actual situation. Future research needs to construct a differentiated electricity-price elasticity coefficient matrix based on different user types and conduct sensitivity analysis on elasticity parameters to quantify the impact of parameter fluctuations on optimization results, thereby improving the accuracy and practical adaptability of demand response guidance strategies.

- (2)

- The model ignores uncertainties (e.g., renewable energy output fluctuations), with unvalidated anti-interference ability and practical robustness. Stochastic and robust optimization methods should be adopted to incorporate various uncertainties into the model framework, enhancing the stable operation capability of the strategy in complex uncertain environments.

- (3)

- Case validation is solely based on the standard IEEE 33-node system, limiting comprehensive validation of the strategy’s universality. Subsequent studies should expand multi-scenario and multi-scale verification, testing the strategy in complex scenarios (e.g., different network topologies, actual power grids) and optimizing model parameters with real engineering cases to improve practical adaptability. Additionally, while the algorithm may remain relatively stable with slight increases in system scale, significant upscaling will lead to exponential growth in decision variables and constraints, triggering the curse of dimensionality, prolonged computation time, slow convergence, or local optima, which hinders effective solutions within engineering time limits. Thus, algorithm optimization requires establishing a more comprehensive NSGA-III comparison system, conducting parameter sensitivity analysis to clarify the applicable ranges of key parameters such as crossover probability and mutation rate, quantifying convergence speed and computational cost, compared with algorithms like MOPSO, and exploring algorithm adaptability under different node scales to provide a basis for algorithm selection. In the future, efforts should also be made to reduce computational complexity by optimizing core algorithm parameters and improving the solution process and to systematically analyze the convergence speed and resource occupancy under different node scales to enhance the feasibility of practical deployment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.X.; methodology, Z.Y.; validation, Y.S.; formal analysis, G.W.; investigation, Y.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.X.; writing—review and editing, B.Y. and Z.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science and Technology Project of Yunnan Power Grid Co., Ltd.—Research on Application of High Reliability Distribution Automation Planning and Evaluation Technologies, grant number YNKJXM20230269.

Data Availability Statement

Datasets are available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Yuan Xu, Zhenhua You, Yan Shi and Gang Wang were employed by the company Yuxi Power Supply Bureau, Yunnan Power Grid Co., Ltd. Author Yujue Wang was employed by the company Eshan Power Supply Bureau, Yunnan Power Grid Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Nomenclature

| Abbreviations | |

| ADN | active distribution network |

| DG | distributed generation |

| DR | demand response |

| ESS | energy storage system |

| NSGA-III | non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm III |

| PV | photovoltaic |

| SOC | state of charge |

| SOP | soft open point |

| TOU | time-of-use |

| WT | wind turbine |

| Variables | |

| electricity price before implementing TOU | |

| electricity consumption in period | |

| demand price elasticity coefficient; subscripts s and z represent peak, flat, and valley periods | |

| average net load variation | |

| electricity-cost satisfaction index | |

| electricity price after implementing time-of-use pricing | |

| electricity purchase from the main grid before implementing TOU | |

| power consumption habit deviation | |

| electricity price fluctuation in different periods | |

| set of adjacent nodes of node | |

| unit capacity investment cost of SOPs | |

| capacity of SOPs installed between node and node | |

| service life of SOPs | |

| daily comprehensive cost of ESS | |

| arbitrage revenue of ESS | |

| revenue from network loss reduction | |

| scheduling net revenue | |

| voltage fluctuation |

References

- Hu, Y.W.J.; Yang, B.; Wu, P.Y.; Wang, X.T.; Li, J.L.; Huang, Y.P.; Su, R.; He, G.B.; Yang, J.; Shi, S. Optimal planning of electric-heating integrated energy system in low-carbon park with energy storage system. J. Energy Storage 2024, 99, 113327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.X.; Guo, H.Y.; Feng, C.; Yu, S.T.; Tang, Y. Modeling strategic behaviors of renewable-storage system in low-inertia power system. Prot. Control. Mod. Power Syst. 2025, 10, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Nie, M.; Zhang, H.Y. Dynamic state estimation based protection for large-scale renewable energy transmission lines. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2025, 13, 1188–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Zhou, Y.M.; Yan, Y.F.; Su, S.; Li, J.L.; Yao, W.; Li, H.B.; Gao, D.K.; Wang, J.B. A critical and comprehensive handbook for game theory applications on new power systems: Structure, methodology, and challenges. Prot. Control. Mod. Power Syst. 2025, 10, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.X.; Lin, Z.; Liu, C.X.; Chen, F.X.; Shao, Z.G. MADDPG-based active distribution network dynamic reconfiguration with renewable energy. Prot. Control. Mod. Power Syst. 2024, 9, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Wang, J.T.; Chen, Y.X.; Li, D.Y.; Zeng, C.Y.; Chen, Y.J.; Guo, Z.X.; Shu, H.C.; Zhang, X.S.; Yu, T. Optimal sizing and placement of energy storage system in power grids: A state-of-the-art one-stop handbook. J. Energy Storage 2020, 32, 101814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, L.S.; Liu, G.Q.; Zhu, S.T.; Hou, M.; Liu, X.R. Fault recovery strategy for urban distribution networks using soft open points. Energy Convers. Econ. 2024, 5, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.L.; Yang, B.; Huang, J.X.; Guo, Z.X.; Wang, J.B.; Zhang, R.; Hu, Y.W.J.; Shu, H.C.; Chen, Y.X.; Yan, Y.F. Optimal planning of electricity hydrogen hybrid energy storage system considering demand response in active distribution network. Energy 2023, 273, 127142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, A.; Shankar, R. An interactive operating demand response approach for hybrid power systems integrating renewable energy sources. Prot. Control. Mod. Power Syst. 2024, 9, 174–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.N.; Michalek, J.; Kar, S.; Chen, Q.X.; Zhang, D.; Whitacre, J.F. Utility-scale portable energy storage systems. Joule 2020, 5, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elalfy, D.A.; Gouda, E.; Kotb, M.F.; Bureš, V.; Sedhom, B.E. Comprehensive review of energy storage systems technologies, objectives, challenges, and future trends. Energy Strategy Rev. 2024, 54, 101482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Rasheed, R.H.; Albahadly, E.J.K.; Zhang, J.; Alqahtani, F.; Tolba, A.; Jin, K. Application of fixed and mobile battery energy storage flexibilities in robust operation of two-way active distribution network. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2025, 244, 111556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Wang, R.; Meng, H.; Li, M.; Wang, H.; Ji, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, Q.; Song, P.; Xiang, J. A coordinated two-stage decentralized flexibility trading in distribution grids with MGs. Prot. Control. Mod. Power Syst. 2024, 9, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, F.; Teh, J.; Lai, C.M. Optimum allocation of battery energy storage systems for power grid enhanced with solar energy. Energy 2021, 223, 120105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganivada, P.K.; El-Fouly, T.H.M.; Zeineldin, H.H.; Al-Durra, A. Optimal siting and sizing of mobile-static storage mix in distribution systems with high renewable energy resources penetration. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2024, 226, 109860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkadeem, M.R.; Abido, M.A. Optimal planning and operation of grid-connected PV/CHP/battery energy system considering demand response and electric vehicles for a multi-residential complex building. J. Energy Storage 2023, 72, 108198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.L.; Yang, B.; Zhou, Y.M.; Yan, B.Y.; Li, H.B.; Gao, D.K.; Jiang, L. Stackelberg game-based optimal coordination for low carbon park with hydrogen blending system. Renew. Energy 2026, 256, 124118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, H.H. Three-layer optimization of energy storage configuration and scheduling in data centers considering demand response. Energy Conserv. 2025, 44, 36–42. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.Z.; Li, M.L.; Jiang, Z.Y.; Liu, X.Y.; Guo, Y.M. Optimal operation of regional integrated energy system considering demand side electricity heat and natural-gas loads response. Power Syst. Prot. Control. 2020, 48, 31–37. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.Y.; Xu, Z.; Jia, Y.W. Full-model-free adaptive graph deep deterministic policy gradient model for multi-terminal soft open point voltage control in distribution systems. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2024, 12, 1893–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, C.; Li, J.Y.; Zhu, L.P.; Cao, S.R.; Huang, W.; Shuai, Z.K. Multi-resource collaborative service restoration of a distribution network with decentralized hierarchical droop control. Prot. Control. Mod. Power Syst. 2024, 9, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.Y.; Luo, F.Z.; Wang, C.S.; Lyu, Y.; Mu, R.F.; Fo, J.C.; Ge, L.K. Collaborative configuration optimization of soft open points and distributed multi-energy stations with spatiotemporal coordination and complementarity. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2025, 13, 2086–2097. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.L.; Yao, M.K.; Yu, H.; Song, G.Y.; Ji, H.; Li, P. Decentralized voltage control strategy of soft open points in active distribution networks based on sensitivity analysis. Electronics 2020, 9, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Yuan, X.F.; Xiong, W.; Zheng, H.J.; Xu, Y.T.; Cai, Y.X.; Zhong, J.M. flexible interconnected distribution network with embedded dc system and its dynamic reconfiguration. Energies 2022, 15, 5589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.F.; Yue, S.M.; Yu, Y.X.; Chen, W.B.; Wang, S.M.; Pu, X.Z. Price elasticity matrix of demand in current retail power market. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2004, 28, 16–19. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.Y.; Hu, B.; Xie, K.G.; Wan, L.Y.; Xiang, B. A peak-valley TOU price model considering power system reliability and power purchase risk. Power Syst. Technol. 2014, 38, 2141–2148. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.Q.; Bremner, S.; Menictas, C.; Kay, M. Modelling and optimal energy management for battery energy storage systems in renewable energy systems: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 167, 112671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.Y.; Ma, C.Y.; Ji, H.R.; Hasanie, H.M.; Yu, J.C.; Zhao, J.L.; Yu, H.; Li, P. Bi-level supply restoration method for active distribution networks considering multi-resource coordination. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2025, 13, 967–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Zhou, G.; Zhou, S.; Hu, Y.W.J.; He, B.; Guo, Z.X.; Luo, Z.B.; Li, H.B.; Gao, D.K.; Wang, J.B.; et al. Multi-objective optimal Bi-level scheduling of hybrid mobile-stationary energy storage systems for flexible distribution network. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 525, 146534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.Y.; Xu, B.L.; Wang, D.; Zhang, B.S. Using battery storage for peak shaving and frequency regulation: Joint optimization for superlinear gains. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2017, 33, 2882–2894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, L.; Di, L.; Zhao, J.; Liu, H.; Hu, Y.; Wei, X. Optimal Scheduling of Active Distribution Networks with Hybrid Energy Storage Systems Under Real Road Network Topology. Processes 2025, 13, 1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.F.; Zhou, R.; Cui, Q.M.; Wang, Y.; Li, B.Q.; Zhou, Y.B. A Reinforcement learning-based dynamic network reconfiguration strategy considering the coordinated optimization of SOPs and traditional switches. Processes 2025, 13, 1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaaeldin, I.M.; Aleem, S.H.E.A.; El-Rafei, A.; Abdelaziz, A.Y.; Zobaa, A.F. Optimal network reconfiguration in active distribution networks with soft open points and distributed generation. Energies 2019, 12, 4172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.Q.; Jiang, T.; Li, F.X.; Chen, H.H.; Li, X. Distributed energy storage planning in soft open point based active distribution networks incorporating network reconfiguration and DG reactive power capability. Appl. Energy 2018, 210, 1082–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Ruan, G.; Zhong, H. Resilient distribution network with degradation-aware mobile energy storage systems. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2024, 230, 110225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Qian, T.; Li, W.; Zhao, W.; Tang, W.; Chen, X.; Yu, Z. Mobile energy storage systems with spatial–temporal flexibility for post-disaster recovery of power distribution systems: A bilevel optimization approach. Energy 2023, 282, 128300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Y.; Zhou, S.; Liu, J.P.; Tong, J.; Dang, J.; Yang, F.Y.; Ouyang, M.G. Multi-objective optimization of the Atkinson cycle gasoline engine using NSGA-III coupled with support vector machine and back-propagation algorithm. Energy 2023, 262, 125262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.