Distributed Model Predictive Control-Based Power Management Scheme for Grid-Integrated Microgrids

Abstract

1. Introduction

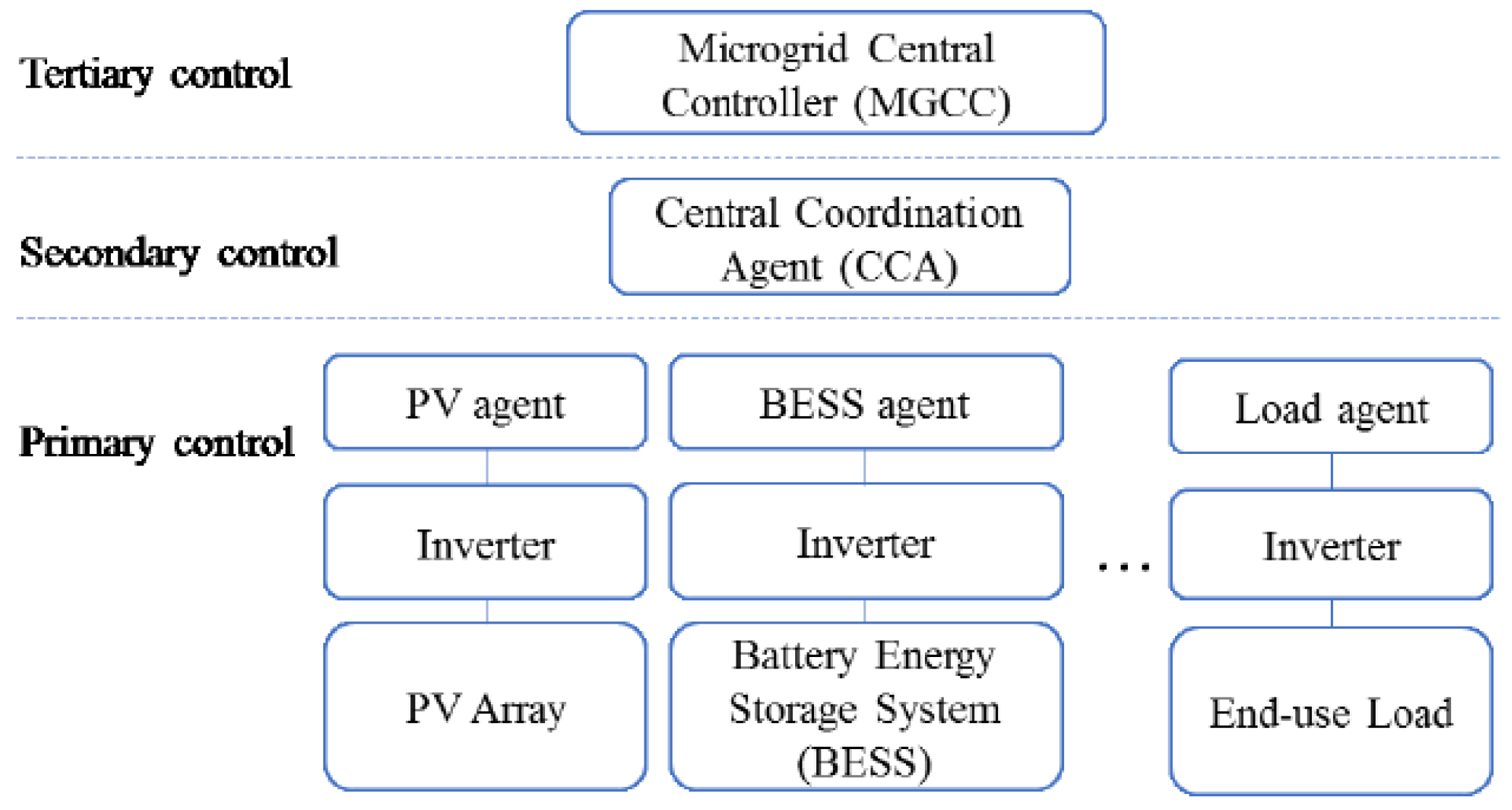

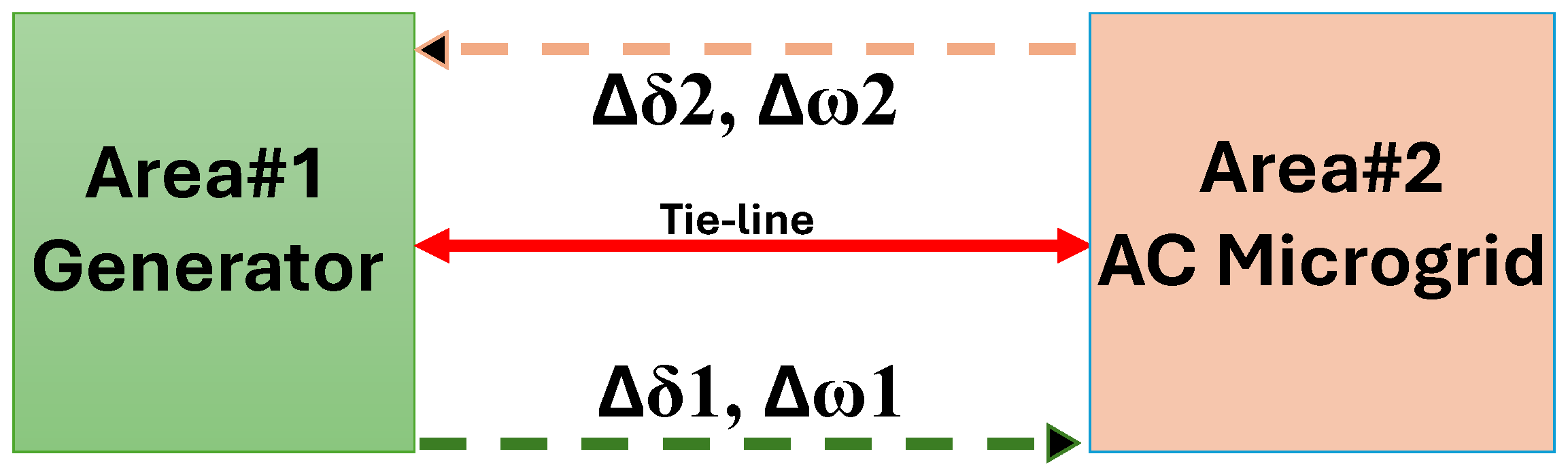

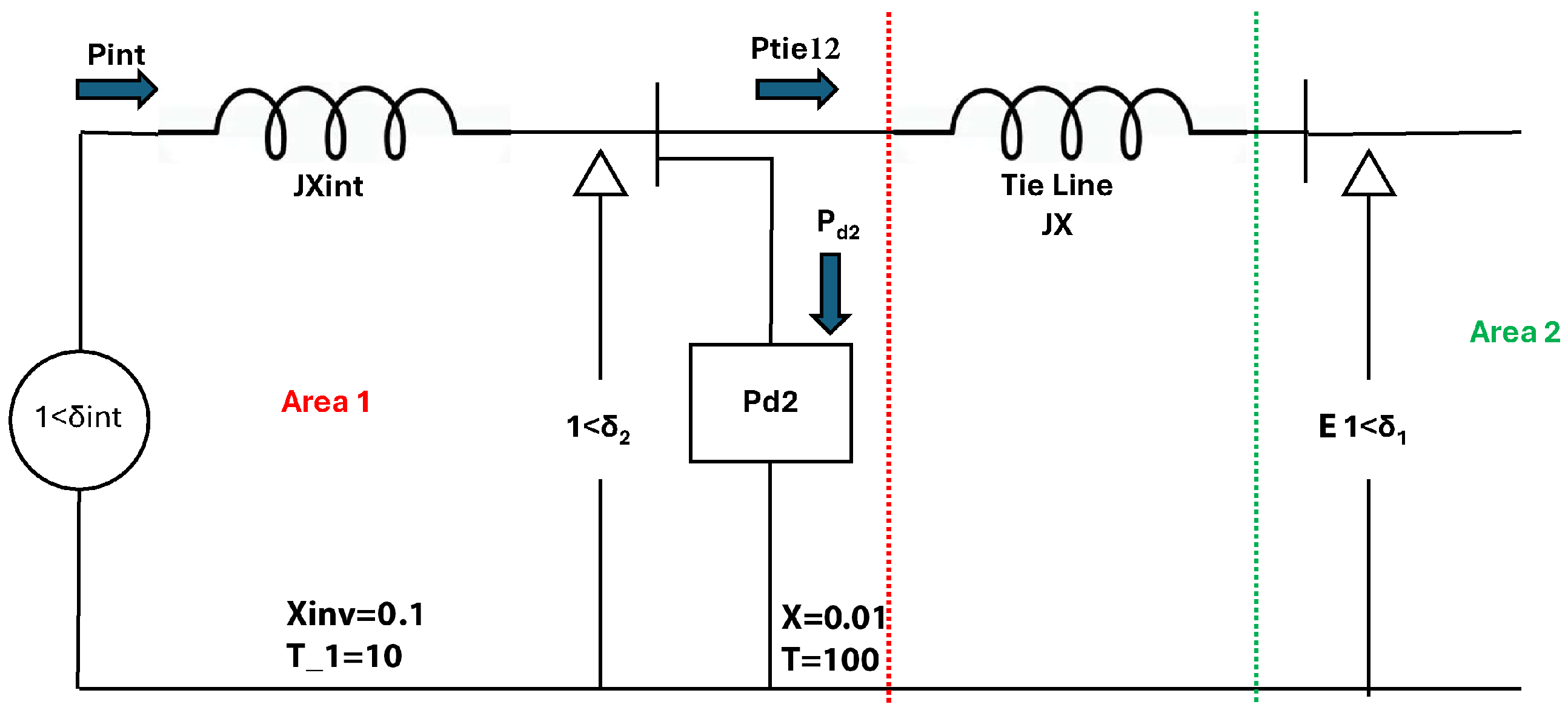

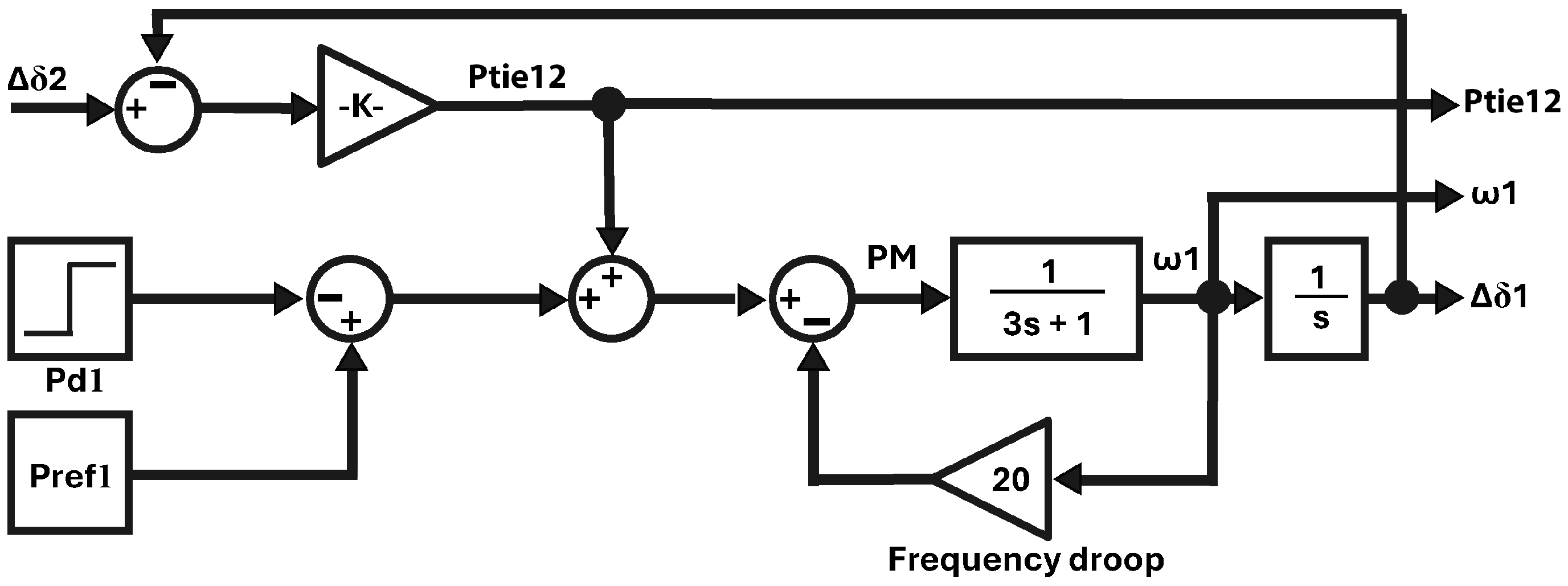

2. System Modeling

2.1. Problem Description

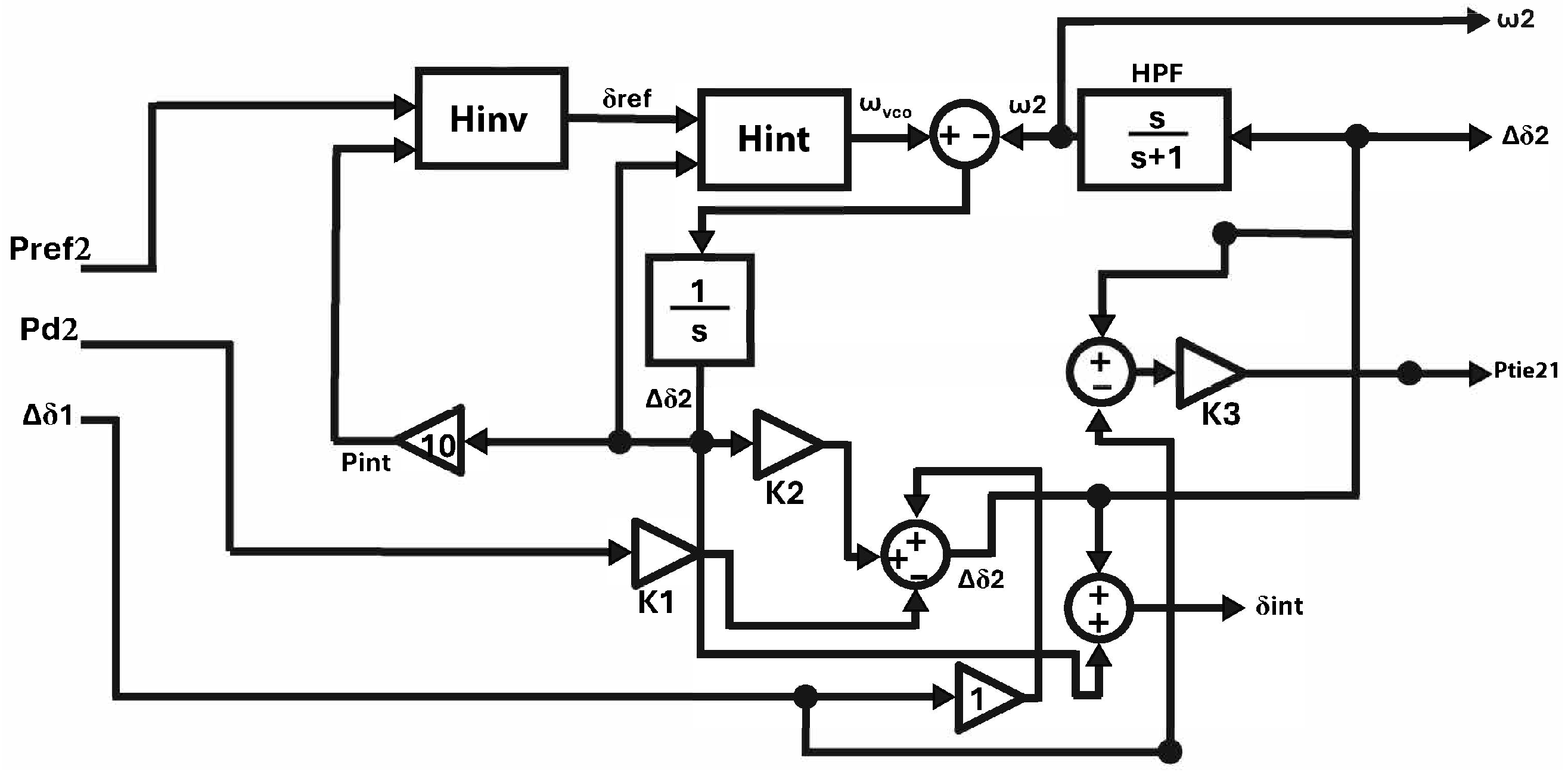

2.2. Model Representation

- : Power setting for the synchronous generator.

- : Power scheduled at the inverter.

- : Loads in Area#1 and Area#2, respectively.

- : Power setting for the synchronous generator from a DMPC controller.

- : Power setting for the inverter from a DMPC controller.

- : Tie-line power from Area#1 to Area#2.

- : Tie-line power from Area#2 to Area#1.

- : Actual power from the inverter.

- : Desired internal angle for the inverter.

- : Actual internal angle for the inverter from the power controller (synchronous frame or absolute).

- : Terminal voltage angle for the synchronous generator (synchronous frame).

- : Terminal voltage angle for the inverter (synchronous frame).

- : Internal voltage angle of the inverter relative to the terminal voltage angle.

- : Area#1, Area#2, and inverter PLL frequencies (p.u.), respectively.

- Tie-line inductive reactance, p.u.

- Inverter output inductive reactance, p.u.

2.3. State-Space Models

2.4. Controllability and Observability of Subsystems

3. Controller Design Using Distributed Model Predictive Control (DMPC)

3.1. DMPC Setup

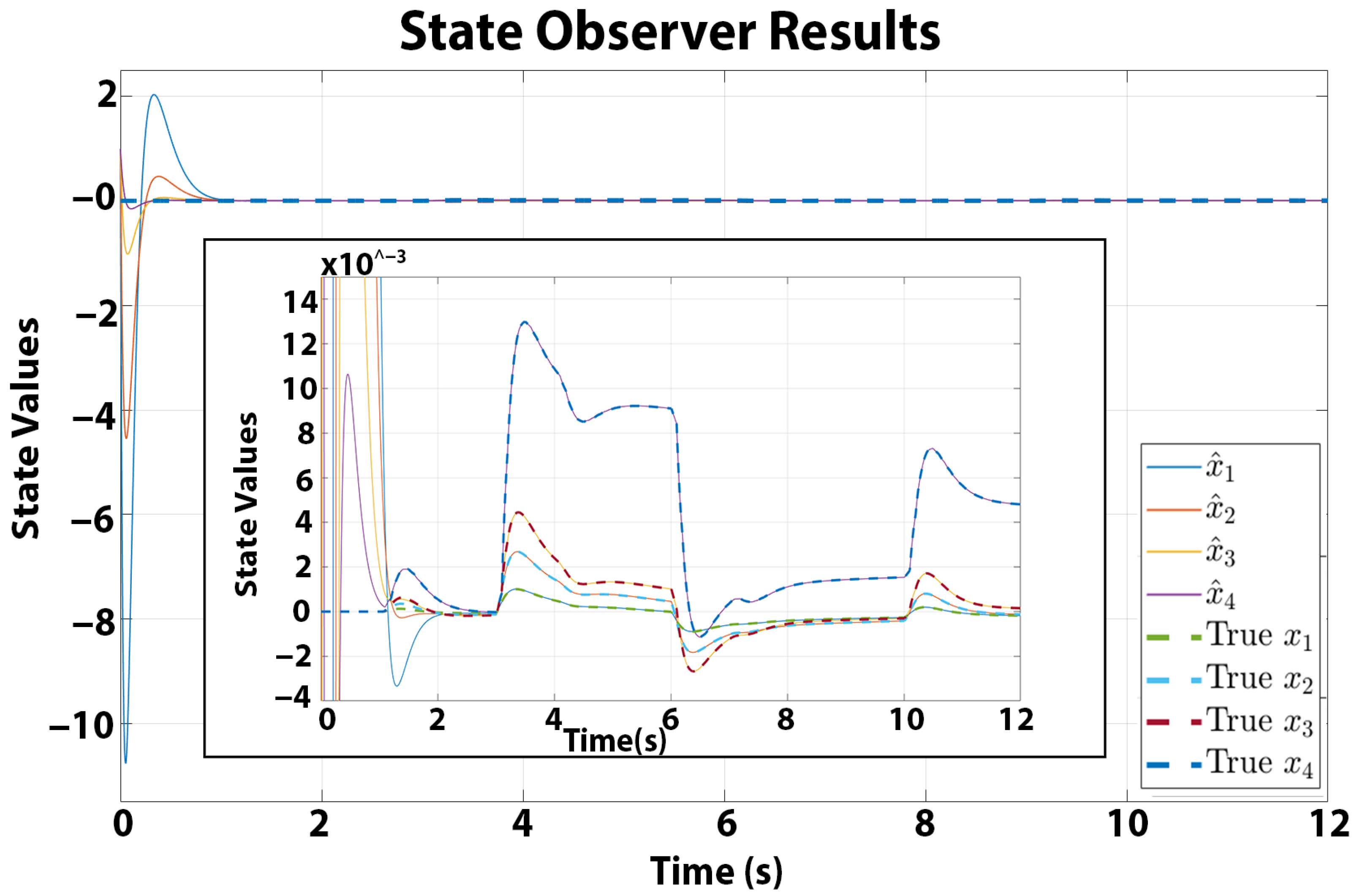

3.2. Observer Design for State Estimation

4. Results and Discussions

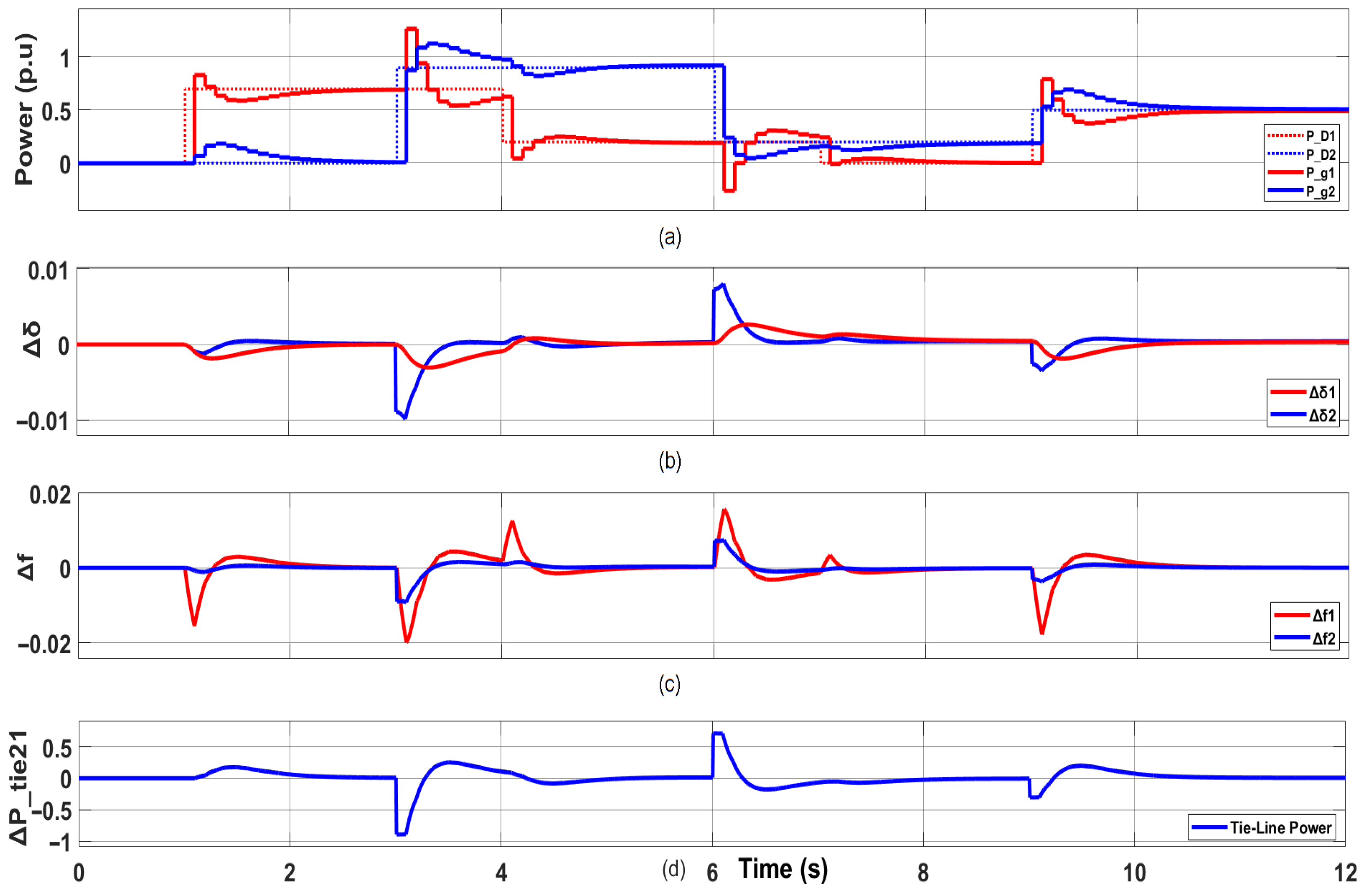

4.1. Power–Load Simulation Results

4.2. State Observer Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DMPC | Distributed Model Predictive Control |

| MPC | Model Predictive Control |

| LFC | Load Frequency Control |

| MG | Microgrid |

| DER | Distributed Energy Resource |

| APOPT | Advanced Process OPTimizer |

| IPOPT | Interior Point OPTimizer |

| GF-I | Grid-Following Inverter |

| PLL | Phase-Locked Loop |

| SV | State Variable |

| CV | Controlled Variable |

References

- Mutule, A.; Antoskova, I.; Papadimitriou, C.; Efthymiou, V.; Morch, A. Development of Smart Grid Standards in View of Energy System Functionalities. In Proceedings of the 2021 6th International Conference on Smart and Sustainable Technologies (SpliTech), Split and Bol, Croatia, 8–11 September 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loka, R.; Parimi, A.M.; Srinivas, S. Model Predictive Control Design for Fast Frequency Regulation in Hybrid Power System. In Proceedings of the 2022 2nd International Conference on Power Electronics & IoT Applications Renewable Energy and Its Control (PARC), Mathura, India, 21–22 January 2022; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, K.P.; Laval, S.; Hansen, J.; Melton, R.B.; Ponder, L.; Fox, L.; Hart, J.; Hambrick, J.; Buckner, M.; Baggu, M.; et al. A Distributed Power System Control Architecture for Improved Distribution System Resiliency. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 9957–9970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planas, E.; Gil-de-Muro, A.; Andreu, J.; Kortabarria, I.; Martínez de Alegría, I. General aspects, hierarchical controls and droop methods in microgrids: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 17, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camponogara, E.; Jia, D.; Krogh, B.; SN, T. Distributed model predictive control. IEEE Control Syst. 2002, 22, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christofides, P.D.; Scattolini, R.; Muñoz de la Peña, D.; Liu, J. Distributed model predictive control: A tutorial review and future research directions. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2013, 51, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, I.; Limon, D.; Muñoz de la Peña, D.; Maestre, J.M.; Ridao, M.A.; Scheu, H.; Marquardt, W.; Negenborn, R.R.; De Schutter, B.; Valencia, F.; et al. A Comparative Analysis of Distributed MPC Techniques Applied to the HD-MPC Four-Tank Benchmark. J. Process Control 2011, 21, 800–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negenborn, R.R.; van Overloop, P.J.; Keviczky, T.; De Schutter, B. Distributed Model Predictive Control for Irrigation Canals. Netw. Heterog. Media 2009, 4, 359–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Glavic, M.; Wehenkel, L. Comparison of centralized, distributed and hierarchical model predictive control schemes for electromechanical oscillations damping in large-scale power systems. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2014, 58, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negenborn, R.R.; Maestre, J.M. Distributed Model Predictive Control: An Overview and Roadmap of Future Research Opportunities. IEEE Control Syst. Mag. 2014, 34, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, T.; Wang, Y.; Tan, K.T.; So, P.L. Model Predictive Control of Distributed Generation Inverter in a Microgrid. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Innovative Smart Grid Technologies-Asia (ISGT ASIA), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 20–23 May 2014; pp. 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arena, P.; Sueri, P.; Taffara, S.; Patanè, L. MPC-based control strategy of a neuro-inspired quadruped robot. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Shenzhen, China, 18–22 July 2021; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Zhang, L.; Wang, P.; Han, Y.; Lin, W. Learning-Based Model Predictive Control for Vehicles with Modeling Bias. In Proceedings of the 2023 42nd Chinese Control Conference (CCC), Tianjin, China, 24–26 July 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Hedengren, J.D.; Beard, R.W. Optimal trajectory generation using model predictive control for aerially towed cable systems. J. Guid. Control Dyn. 2014, 37, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Chang, P. Load Frequency Control of Multi-area Interconnected Power System with Renewable Energy. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Sustainable Power and Energy Conference (iSPEC), Nanjing, China, 23–25 December 2021; pp. 1814–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.; Liu, K.; Qin, L.; Wang, N.; Ma, Y.; Chen, Z.; Ding, K.; Zhou, Q. Cooperative DMPC-Based Load Frequency Control of AC/DC Interconnected Power System with Solar Thermal Power Plant. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE PES Asia-Pacific Power and Energy Engineering Conference (APPEEC), Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia, 7–10 October 2018; pp. 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escamilla, L.; Shi, Y.; Wang, Z.; Augustine, S.; Lavrova, O.; Ranade, S.; Sun, L. Development of Distributed Model Predictive Control Tools for Power Generation Systems. In Proceedings of the 2021 North American Power Symposium (NAPS), College Station, TX, USA, 14–16 November 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aafia, H.M.; Zakhary, K.R.; Gheith, R.H.; Gomaa, A.M.; Saleh, A.A.; Guirgis, V.G.; Awaad, M.I.; Maged, S.A. A Comparison between Linear, Nonlinear, and Adaptive MPC Controllers for ABB IRB120 Robot in Collaborative Assembly. In Proceedings of the 2022 2nd International Mobile, Intelligent, and Ubiquitous Computing Conference (MIUCC), Cairo, Egypt, 8–9 May 2022; pp. 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangeti, L.; Marimuthu, R. Distributed model predictive control strategy for microgrid frequency regulation. Energy Rep. 2025, 13, 1158–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Yang, L.; Liu, T.; Hill, D.J. Distributed Model Predictive Frequency Control of Inverter-Based Networked Microgrids. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2021, 36, 2623–2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.T.; Nguyen, S.Q.; Vo, B.L.; Le, N.D.; Tran, M.K. Two-level distributed fully-predictive frequency control scheme for inverter-based AC Microgrid considering communication delay. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2023, 222, 109471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L. Control of Single-Phase LCL Photovoltaic Grid-Connected Inverter Based on State Observer. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Power, Intelligent Computing and Systems (ICPICS), Shenyang, China, 28–30 July 2020; pp. 762–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatulea-Codrean, A.; Haßkerl, D.; Urselmann, M.; Engell, S. Steady-state optimization and nonlinear model-predictive control of a reactive distillation process using the software platform do-mpc. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Control Applications (CCA), Buenos Aires, Argentina, 19–22 September 2016; pp. 1513–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, R.; Cheng, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Hovakimyan, N. DiffTune-MPC: Closed-Loop Learning for Model Predictive Control. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 7294–7301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedengren, J.D.; Shishavan, R.A.; Powell, K.M.; Edgar, T.F. Nonlinear modeling, estimation and predictive control in APMonitor. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2014, 70, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Castagno, J.D.; Hedengren, J.D.; Beard, R.W. Parameter estimation for towed cable systems using moving horizon estimation. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2015, 51, 1432–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, C.; Sun, L. Trajectory tracking control of a drone-guided hose system for fluid delivery. In Proceedings of the AIAA SciTech 2021 Forum, Online, 11–15 & 19–21 January 2021; p. 1003. [Google Scholar]

- Beal, L.D.R.; Hill, D.C.; Martin, R.A.; Hedengren, J.D. GEKKO Optimization Suite. Processes 2018, 6, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D. Electrical Power Systems; New Age International: New Delhi, India, 2006; Available online: https://books.google.com/books?id=9CYS_krSvMUC (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- The MathWorks, Inc. Linearize Simulink Model at Model Operating Point. Available online: https://www.mathworks.com/help/slcontrol/ug/linearize-simulink-model.html (accessed on 2 September 2025).

| Ref. | System | Control Structure | Hybrid Generator/Inverter | Explicit Constraints | State-Space & C/O Analysis | State Estimation | Implemented in MATLAB/Simulink | Validation/Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [3] | Multi-area power system | Distributed/hierarchical DMPC-inspired control | No | No | No | No | Yes | Time-domain simulations |

| [5] | Multi-area power system | Generic DMPC formulation | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Analytical and numerical examples |

| [6] | MG control | Survey of DMPC architectures | No | No | No | No | No | Literature review |

| [10] | Multi-area power system | DMPC roadmap | No | No | No | No | No | No validation |

| [15] | Multi-area power system | MPC-based load frequency control | No | No | No | No | Yes | Numerical simulations |

| [23] | AC/DC interconnected system | Cooperative DMPC | No | No | No | No | Yes | Simulation studies |

| [16] | Power generation systems (generic) | DMPC tool development | No | No | No | No | Yes | Simulation validation |

| Proposed | Grid-integrated two-area microgrid. | Two local DMPCs coordinating to regulate frequency/load and drive tie-line power exchange to zero | Yes | Yes (generator/inverter constraints modeled in the DMPC setup) | Yes (state-space modeling with controllability/observability verification) | Yes (observer designed/tuned for inverter states) | Yes, with APMonitor (local server; coordinated solve cycle) | Time-varying load disturbance simulations; observer convergence shown |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| M | (pu·s/rad) |

| D | (pu/pu) |

| R | (pu/pu) |

| Category | Area 1-DMPC | Area 2-DMPC |

|---|---|---|

| Manipulated Variable | Generator Active Power Adjustment | Inverter Active Power Adjustment |

| Controlled Variables | Frequency deviation ; phase angle deviation ; coordination error | Frequency deviation ; phase angle deviation ; coordination error |

| Power Constraints | −10 10 | −10 10 |

| Communication Assumptions | Ideal, synchronized; no delay modeled | Ideal, synchronized; no delay modeled |

| Term | Weight Factor | Action | Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deviation in angle between area i and area j | Adjust the tie-line power | Determines how strongly area i aligns its predicted angle with area j | |

| Deviation in frequency | Control area i Frequency | Minimizes the frequency error | |

| Generator power change | Actuator smoothing | Regulates generator power adjustment |

| Area 1 | Area 2 |

|---|---|

| : 9,750,000 | : 1,750,000 |

| : 1,250,000 | : 1,250,000 |

| : 0.001 | : 0.001 |

| Time | Area#1 | Time | Area#2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interval (s) | Load (p.u.) | Interval (s) | Load (p.u.) |

| 0 | 0 | ||

| 0.7 | 0.9 | ||

| 0.2 | 0.2 | ||

| 0 | 0.5 | ||

| 0.5 |  |  |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Escareno, S.; Augustine, S.; Sun, L.; Ranade, S.J.; Lavrova, O.; Pontelli, E.; Hedengren, J. Distributed Model Predictive Control-Based Power Management Scheme for Grid-Integrated Microgrids. Energies 2026, 19, 406. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020406

Escareno S, Augustine S, Sun L, Ranade SJ, Lavrova O, Pontelli E, Hedengren J. Distributed Model Predictive Control-Based Power Management Scheme for Grid-Integrated Microgrids. Energies. 2026; 19(2):406. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020406

Chicago/Turabian StyleEscareno, Sergio, Sijo Augustine, Liang Sun, Sathishkumar J. Ranade, Olga Lavrova, Enrico Pontelli, and John Hedengren. 2026. "Distributed Model Predictive Control-Based Power Management Scheme for Grid-Integrated Microgrids" Energies 19, no. 2: 406. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020406

APA StyleEscareno, S., Augustine, S., Sun, L., Ranade, S. J., Lavrova, O., Pontelli, E., & Hedengren, J. (2026). Distributed Model Predictive Control-Based Power Management Scheme for Grid-Integrated Microgrids. Energies, 19(2), 406. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020406