Abstract

Rapid decarbonization and decentralization of power systems are driving the integration of renewable generation, energy storage and digital technologies into unified energy ecosystems. In this context, photovoltaic (PV) systems combined with battery and hydrogen storage and blockchain-based platforms represent a promising pathway toward sustainable and transparent energy management. This study evaluates the techno-economic performance and operational feasibility of integrated PV systems combining battery and hydrogen storage with a blockchain-based peer-to-peer (P2P) energy trading platform. A simulation framework was developed for two representative consumer profiles: a scientific–educational institution and a residential household. Technical, economic and environmental indicators were assessed for PV systems integrated with battery and hydrogen storage. The results indicate substantial reductions in grid electricity demand and CO2 emissions for both profiles, with hydrogen integration providing additional peak-load stabilization under current cost constraints. Blockchain functionality was validated through smart contracts and a decentralized application, confirming the feasibility of P2P energy exchange without central intermediaries. Grid electricity consumption is reduced by up to approximately 45–50% for residential users and 35–40% for institutional buildings, accompanied by CO2 emission reductions of up to 70% and 38%, respectively, while hydrogen integration enables significant peak-load reduction. Overall, the results demonstrate the synergistic potential of integrating PV generation, battery and hydrogen storage and blockchain-based trading to enhance energy independence, reduce emissions and improve system resilience, providing a comprehensive basis for future pilot implementations and market optimization strategies.

1. Introduction

Climate change, geopolitical uncertainty and the relentless growth of global energy demand are reshaping the structure and dynamics of the energy sector. Projections from the International Energy Agency indicate that electricity consumption will nearly double by 2050, with renewable sources expected to provide the majority of global generation. This profound transition, reinforced by the electrification of end-use sectors and the decarbonization of heating and transport, underscores the need for integrated and adaptive system-planning frameworks that transcend conventional generation paradigms [1,2]. Within this framework, the European Union’s Green Deal emphasizes that the decarbonization of the power sector represents a critical milestone in achieving climate neutrality by the mid-century [3]. Combined heat and power (CHP) and combined cooling, heating and power (CCHP) systems remain vital components of transitional energy strategies, providing high-efficiency links between conventional and renewable energy sectors [4].

Among renewable energy sources, photovoltaic (PV) systems represent one of the most dynamic and rapidly expanding segments. The global installed PV capacity surpassed 1 TW in 2022, maintaining an annual growth rate exceeding 20% [5]. The key advantages of PV technology include implementation flexibility, relatively low operating costs and the potential for integration across multiple scales, from individual households to large industrial complexes [6]. Recent methodological advances have introduced adaptive teaching–learning-based optimization techniques to PV systems, enabling enhanced parameter identification and improved model fidelity under variable real-world conditions. In parallel, the application of multi-objective optimization algorithms to hybrid renewable systems combining PV, wind and hydrogen storage has demonstrated marked improvements in cost efficiency, operational reliability and carbon abatement potential. Comprehensive literature syntheses increasingly position hydrogen as a cornerstone of renewable-based energy architectures due to its capacity to mitigate intermittency and provide long-duration storage through power-to-gas pathways. As underscored by Bhandari and Adhikari [7,8,9], the integration of hydrogen within PV- and wind-dominated systems not only enhances grid flexibility and seasonal storage but also enables deep cross-sectoral decarbonization.

Similar optimization approaches have been successfully applied in hybrid solar systems, where multi-objective models were used to balance thermodynamic performance and economic efficiency, demonstrating the importance of integrated renewable system optimization [10]. The intrinsic intermittency of solar generation, governed by diurnal and meteorological variations, continues to challenge the stability and reliability of photovoltaic (PV) systems. Empirical studies examining the effects of extreme weather phenomena on PV output underscore the necessity of adaptive design methodologies and predictive forecasting models capable of maintaining operational resilience under variable climatic conditions. This stochastic behavior complicates grid coordination and necessitates the deployment of advanced energy storage and control mechanisms to safeguard supply continuity and system reliability [11,12]. Comparable studies on wind power integration have reported similar challenges in maintaining voltage stability and dispatchability, emphasizing the need for complementary storage technologies and predictive control frameworks [13].

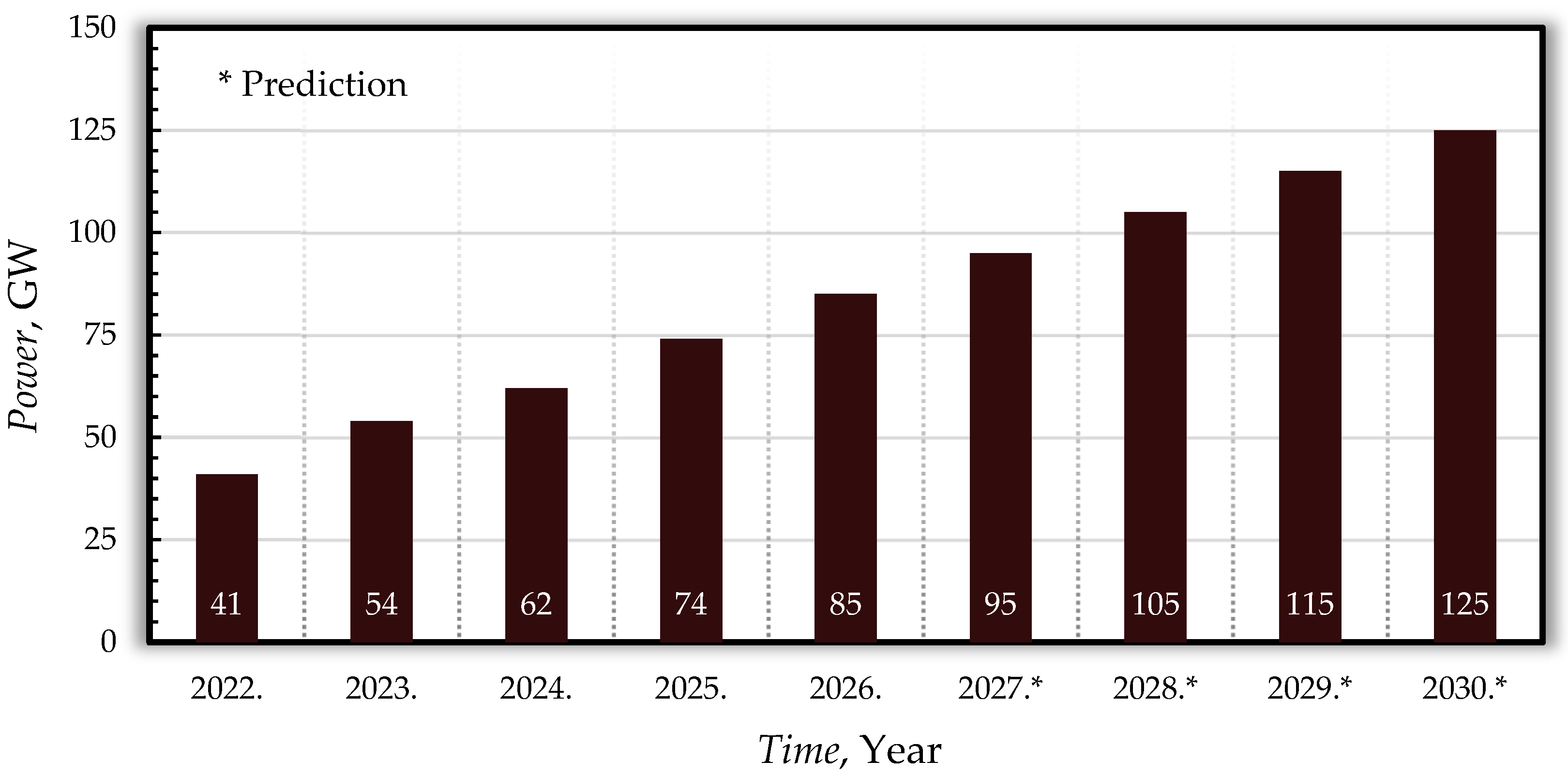

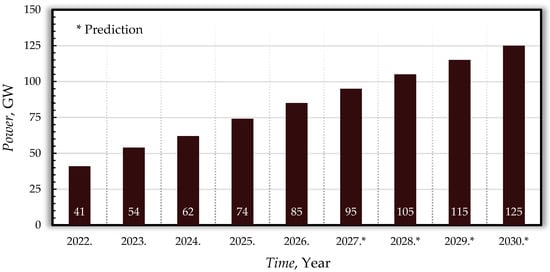

The growth of PV systems has been particularly pronounced within the European Union. In 2022 alone, approximately 41 GW of new capacity was installed, representing an increase of nearly 50% compared to 2021 [14]. Projections toward 2030 indicate sustained expansion, with an average of 85 GW of new installations per year and a total capacity approaching 920 GW [15]. The National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs) of EU member states promote decentralized electricity generation, including the participation of small-scale producers, or prosumers, thereby reinforcing the need for the development of innovative energy models (Figure 1). Recent high-renewable power system studies, such as the Germany 2045 scenario, are already testing hierarchical predictive control frameworks targeting near-zero net exchange with the main grid, demonstrating that coordinated storage dispatch and forecasting can maintain system balance even under high renewable penetration [16].

Figure 1.

Projected growth of solar PV capacity in the European Union (2022–2030) [14,15].

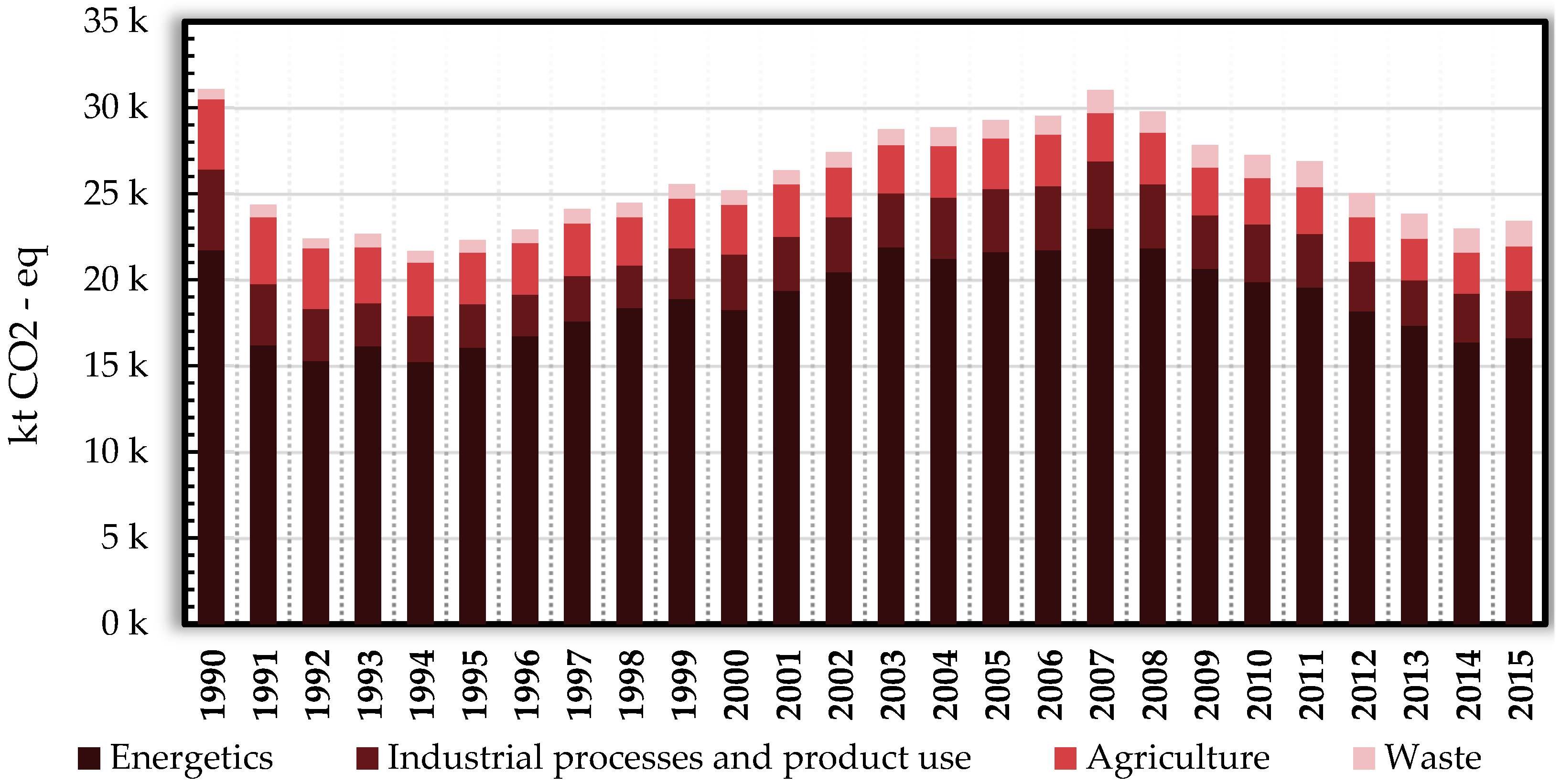

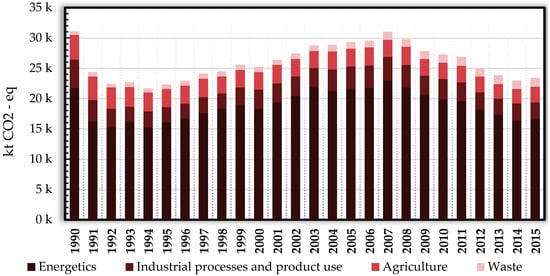

To address these operational challenges, energy storage technologies have become indispensable components of renewable-based systems. Battery energy storage provides short-term balancing of generation and demand but remains constrained by cost, capacity and limited lifespan [17]. Renewable hydrogen technologies can effectively supplement high-efficiency thermal systems such as condensing gas boilers, which continue to play an important transitional role in the decarbonization of residential heating. In addition to their synergy with existing infrastructure, hydrogen solutions enable long-duration energy storage and promote cross-sectoral coupling between power, mobility and industrial applications. Emerging research on thermochemical water-splitting cycles provides further opportunities for sustainable hydrogen production, reducing dependence on electricity-driven electrolysis and enhancing overall system flexibility [18,19,20]. Previous analyses of hybrid thermal–renewable systems confirm that integrating hydrogen production with conventional power plants can substantially enhance overall efficiency and reduce emissions, especially when supported by advanced alternative technologies [21]. Greenhouse gases mainly result from human activity. The calculation includes direct gases (CO2, CH4, N2O, HFCs, PFCs, SF6) and indirect ones (CO, NOx, NMVOCs, SO2). Gases covered by the Montreal Protocol, such as CFCs, are excluded. As shown in Figure 2, the energy sector remains the largest source of emissions [22,23].

Figure 2.

Greenhouse gas emission trends by sector [24].

The rise in renewable energy use suggests a decline in greenhouse gas emissions. However, the 2008–2014 reduction mainly resulted from the economic crisis. Croatia met its Kyoto targets and, after joining the EU, adopted a 20% reduction goal by 2020 and 40% by 2030 under the Paris Agreement.

According to the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), global electrolyzer capacity could reach 350 GW by 2030, with the cost of green hydrogen expected to fall below 2 USD per kilogram [25]. The financial and logistical integration of hydrogen within renewable energy supply chains is gaining momentum, underscoring the emerging role of digital verification and blockchain-enabled traceability in ensuring transparency in green hydrogen markets [26]. Beyond its role as a versatile energy carrier, hydrogen has emerged as a catalyst for industrial transformation and economic restructuring. National and regional policy frameworks increasingly position hydrogen technologies as foundational components of post-fossil competitiveness and long-term energy security.

The integration of hydrogen across sectors presents complex sociotechnical challenges, where digital traceability systems, transparent supply chains and coordinated stakeholder engagement are decisive for large-scale implementation and public acceptance [27,28]. Despite its potential, technological limitations such as the low efficiency of electrolysis and fuel-cell processes, high capital costs and safety concerns continue to impede large-scale deployment [29]. The transition toward large-scale hydrogen utilization presents complex safety and materials challenges, including high-pressure storage integrity, leakage prevention and long-term material degradation. These issues demand the development of harmonized international standards, robust safety protocols and advanced real-time monitoring technologies. In parallel, recent analyses of hybrid renewable system optimization underscore that true system resilience can only be achieved through integrated approaches that simultaneously coordinate generation, storage and control functions within a unified operational framework [30,31]. To overcome these limitations, hybrid battery–hydrogen configurations are increasingly proposed to combine the fast response of batteries with the long-term storage capacity of hydrogen, providing a balanced approach to system flexibility and decarbonization [32].

Hydrogen storage remains a critical bottleneck and ongoing research focuses on improving materials efficiency, safety and cost-effectiveness to enable widespread implementation [33]. Complementary to these physical innovations, blockchain-based service frameworks have been developed for forecasting and managing hydrogen production, linking surplus renewable electricity to electrolyzers through auditable smart contracts and secure data management systems [34]. Recent reviews confirm that hybrid renewable systems combining PV, battery and hydrogen storage technologies can significantly enhance grid resilience and decarbonization potential when coordinated under integrated control architectures [35]. Complementary research on multi-objective optimization frameworks highlights that coordinated operation of hybrid renewable systems with green hydrogen integration and dual storage strategies can substantially improve system flexibility, economic performance and decarbonization outcomes [36].

Building upon these advances in physical infrastructure, the digitalization of energy management has become equally crucial. Traditional centralized systems often exhibit inefficiencies, high transaction costs and limited flexibility in integrating distributed producers [37]. Consequently, microgrid research has shifted toward coordinated control of decentralized renewable sources, storage assets and flexible loads, emphasizing autonomy, resilience and local optimization [38]. Advanced energy management systems increasingly function as the “brain” of distributed grids, leveraging artificial intelligence and predictive analytics to synchronize supply, demand and storage operations in real time [39]. As these networks grow more complex and data-driven, cybersecurity emerges as a fundamental prerequisite; recent studies underscore the importance of authentication, data integrity and tamper-resistant audit trails as essential design elements of modern smart grids [40].

In parallel, blockchain technology has gained prominence as a solution for secure and transparent energy transactions within decentralized systems. Accurate monitoring and machine learning sensor calibration are recognized as key enablers for data reliability in PV, battery and blockchain-linked infrastructures [41]. Similar sensor-based architectures have been successfully validated in other smart infrastructure applications, such as the design and control of mini greenhouses for sustainable agriculture, where sensor–actuator feedback and low-cost microcontroller systems enable real-time environmental monitoring and autonomous operation [42]. When combined with smart contracts, blockchain provides an automated, tamper-proof framework for peer-to-peer (P2P) energy trading, reducing the need for intermediaries and increasing overall system transparency and resilience [43]. P2P trading has thus become a dominant paradigm that facilitates local exchange of renewable electricity among prosumers, supported by blockchain, smart contracts and dynamic pricing algorithms [44]. Beyond market operations, decentralized blockchain–AI architectures are being explored to secure cyber-physical energy infrastructures, demonstrating that blockchain can function simultaneously as a transactional layer and a trust backbone for operational integrity [45]. Recent developments extend this concept to the hydrogen sector, where blockchain-enabled pricing mechanisms for electricity–hydrogen coupling have been implemented at refueling stations, treating hydrogen as an actively traded commodity within local energy ecosystems [46]. Similarly, joint industrial initiatives have shown that blockchain can serve as a coordination and certification platform in hydrogen industry alliances, enabling traceability of production origin, quality and intellectual property across supply chains. Large-scale renewable networks are increasingly adopting blockchain-based trading frameworks to enhance transparency, minimize transaction costs and automate settlement within decentralized market environments [47].

Practical evidence of these advancements can already be observed in European pilot projects. The Enerchain consortium, comprising more than forty energy companies, has developed a blockchain platform for electricity and gas trading, while the Pylon Network in Spain enables transparent data exchange on renewable generation and consumption [48]. Comparable initiatives such as Grid Singularity and WePower integrate blockchain with smart contracts and energy tokenization mechanisms [49]. Industrial applications in China likewise demonstrate blockchain’s potential as a coordination and certification layer for hydrogen production and exchange, fostering innovation and cross-sectoral data transparency [50]. Additional studies, including [51], confirm the relevance of blockchain-enabled frameworks for decentralized hydrogen production using solar resources.

Integrating PV systems, hybrid energy storage (battery and hydrogen) and blockchain technology thus creates a comprehensive energy model uniting generation, storage and trading functions. PV systems provide clean and sustainable power, storage technologies enhance reliability and flexibility and blockchain ensures transparent and secure digital market operations [52]. Recent advances in virtual power plant (VPP) concepts demonstrate how distributed PV, battery and hydrogen systems can be coordinated under unified digital control, with blockchain serving as the settlement and trust layer for multi-actor coordination in net-zero energy networks [53]. Such an integrated approach fosters greater energy independence, reduces greenhouse gas emissions and promotes the creation of new decentralized market mechanisms aligned with global energy transition goals.

However, few existing studies have simultaneously modeled the technical, economic and digital dimensions of PV systems integrating both battery and hydrogen storage within blockchain-based trading frameworks. This gap limits a comprehensive understanding of their synergistic potential and real-world feasibility. Therefore, the present research aims to examine the techno-economic performance of integrated PV–battery–hydrogen systems coupled with blockchain technology for decentralized energy management and P2P trading. Special emphasis is placed on simulating PV performance for distinct consumer categories, modeling hydrogen-based storage of surplus energy and developing a decentralized application for blockchain-enabled electricity exchange. The central hypothesis posits that such an integrated approach can enhance PV utilization, reduce storage-related losses and improve the overall security and resilience of distributed energy networks. The main contribution of this work lies in the unified modeling and evaluation of photovoltaic generation, battery and hydrogen storage and blockchain-based peer-to-peer energy trading within a single techno-economic framework, enabling a system-level assessment of their synergistic effects on emission reduction, peak-load mitigation and decentralized energy management for different consumer categories.

2. Materials and Methods

This section describes the methodological framework applied to model, simulate and integrate the photovoltaic (PV), energy storage and blockchain components of the hybrid energy system. The modeling approach combines established analytical formulations with numerical simulations to evaluate system performance under representative operating conditions. The model was developed for two representative consumer types: a residential household and an institutional building. The two case studies were intentionally selected to represent contrasting but complementary consumer profiles: a scientific–educational institution with high and continuous daytime electricity demand and a residential household with lower, more variable consumption patterns, enabling evaluation of system performance across different scales and operating conditions. Both cases were analyzed under identical methodological assumptions to allow a consistent comparison of the effects of battery storage, hydrogen integration and blockchain-based energy trading.

2.1. Modeling of Photovoltaic Systems

The modeling of PV systems is based on standard mathematical formulations that relate solar irradiance, panel surface area, module efficiency and temperature effects. The output electrical power of a PV array can be approximated by the following equation:

where PPV is the output power of the PV array (W), Gt is the solar irradiance incident on the module surface (W/m2), A is the total surface area of the PV modules (m2), ηPV is the module efficiency under standard test conditions (STC), fT is the temperature correction factor and fsys represents the system loss factor, which accounts for inverter inefficiencies, cable losses, soiling and module mismatch.

The temperature effect on PV module performance is modeled using a correction factor expressed as follows [6]:

where β is the temperature coefficient of the module (%/°C), Tc is the cell temperature (°C) and Tref is the reference temperature, typically 25 °C.

The estimation of the cell temperature is commonly performed using the nominal operating cell temperature (NOCT), according to the following expression [54]:

where Ta is the ambient temperature (°C) and Gt is the solar irradiance on the module surface (W/m2).

Two PV systems of different capacities were considered in this study: a smaller household system rated at 2.2 kW and a larger building-scale system rated at 115 kW.

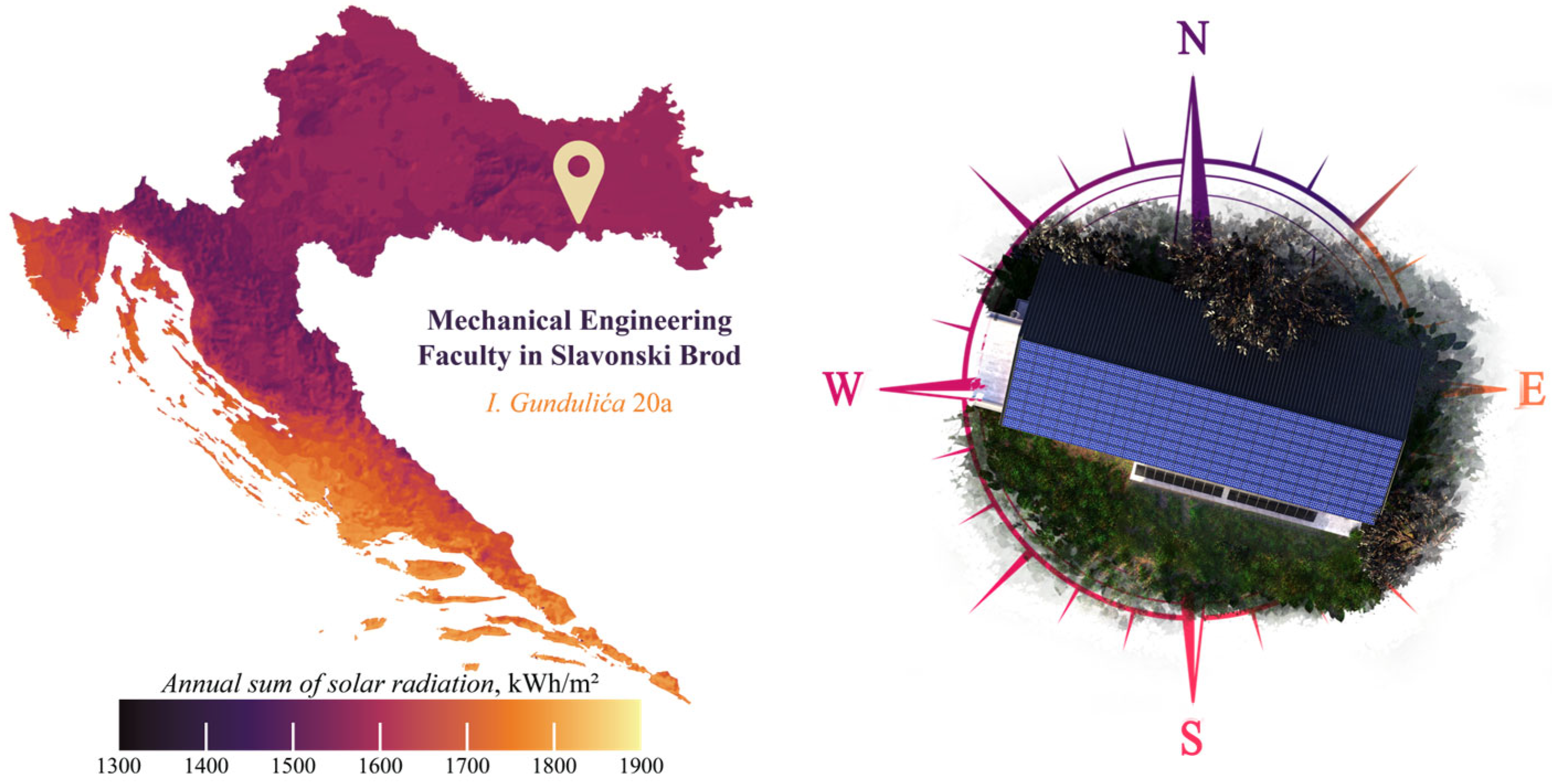

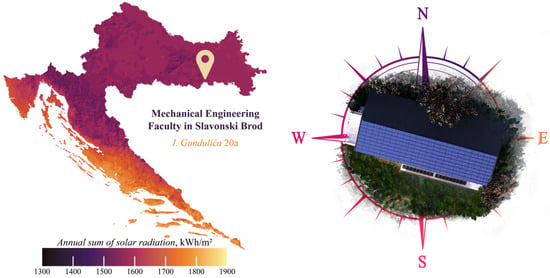

Due to its favorable location and south orientation (Figure 3), the Mechanical Engineering Faculty in Slavonski Brod is well suited for such a system, with annual solar irradiation of 1500–1600 kWh/m2. Coastal Adriatic cities show even higher values, reaching 1700–1900 kWh/m2.

Figure 3.

Annual solar irradiation, geographic location and orientation of the Mechanical Engineering Faculty based on PVGIS data [55].

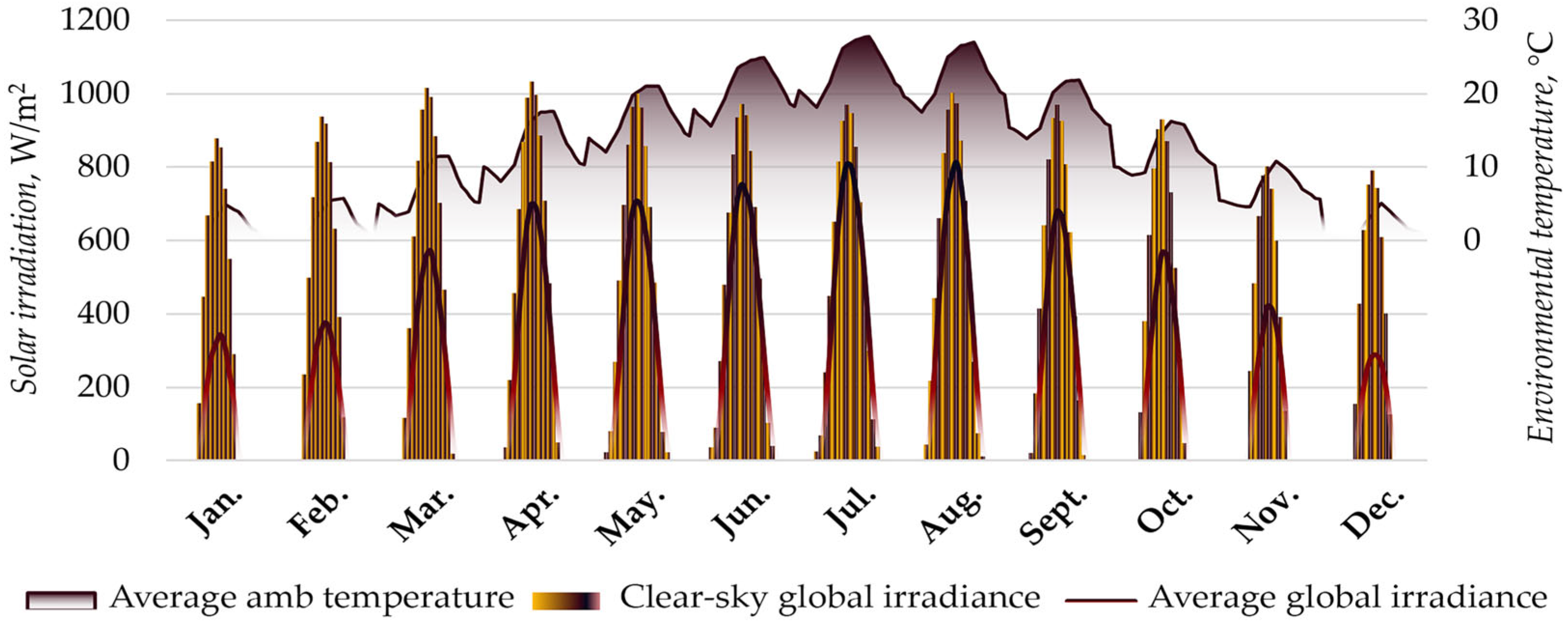

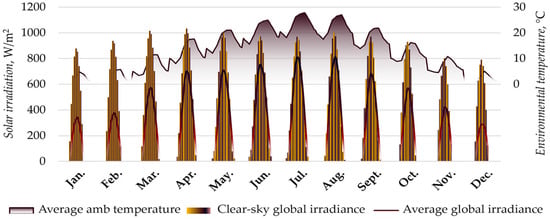

According to meteorological data from the European Commission’s Photovoltaic Geographical Information System (PVGIS) [55], all necessary parameters for the system analysis were obtained. The average monthly values of solar irradiation and ambient temperature for a representative year, based on data collected between 2005 and 2025, are presented in the diagram shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Monthly solar irradiation and ambient temperature data for the representative year.

The input parameters include the technical characteristics of the modules, the number of modules, inverter type, geometric configuration and simulation location. A summary of the main parameters is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Basic input parameters of the PV systems for the household and the building.

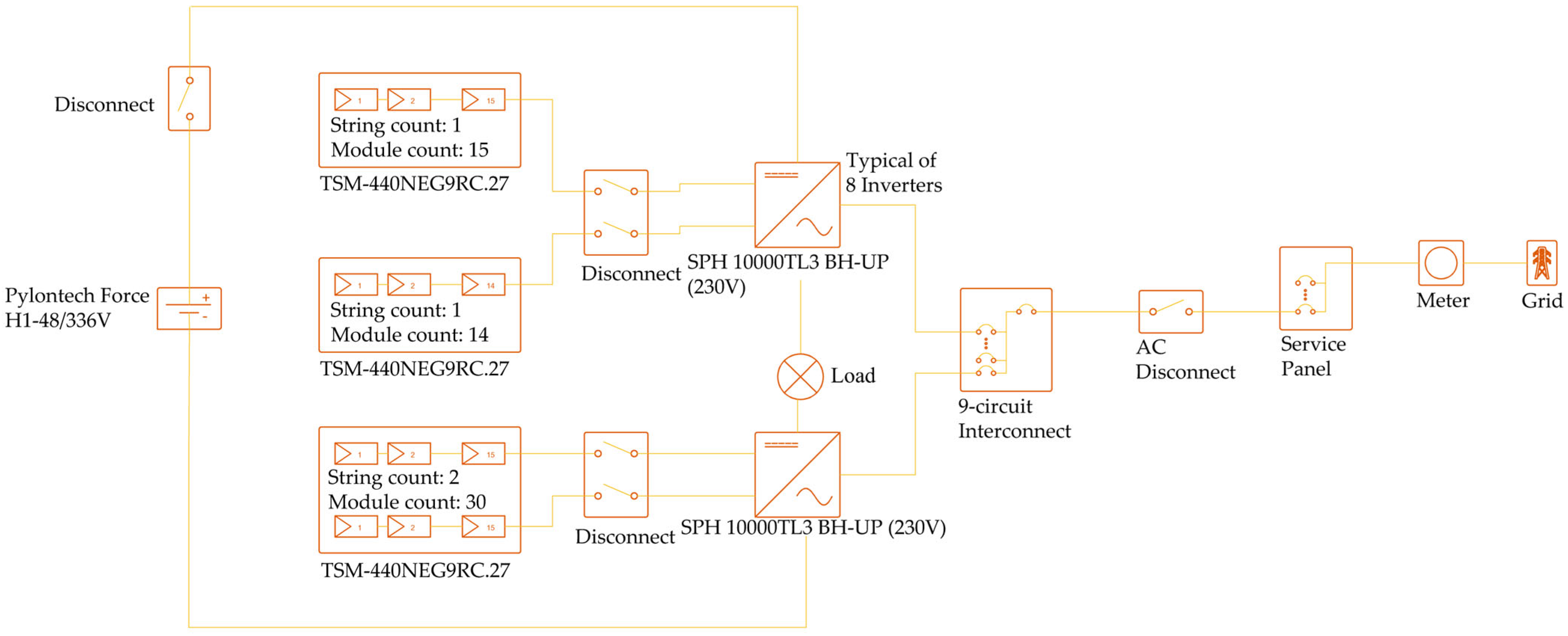

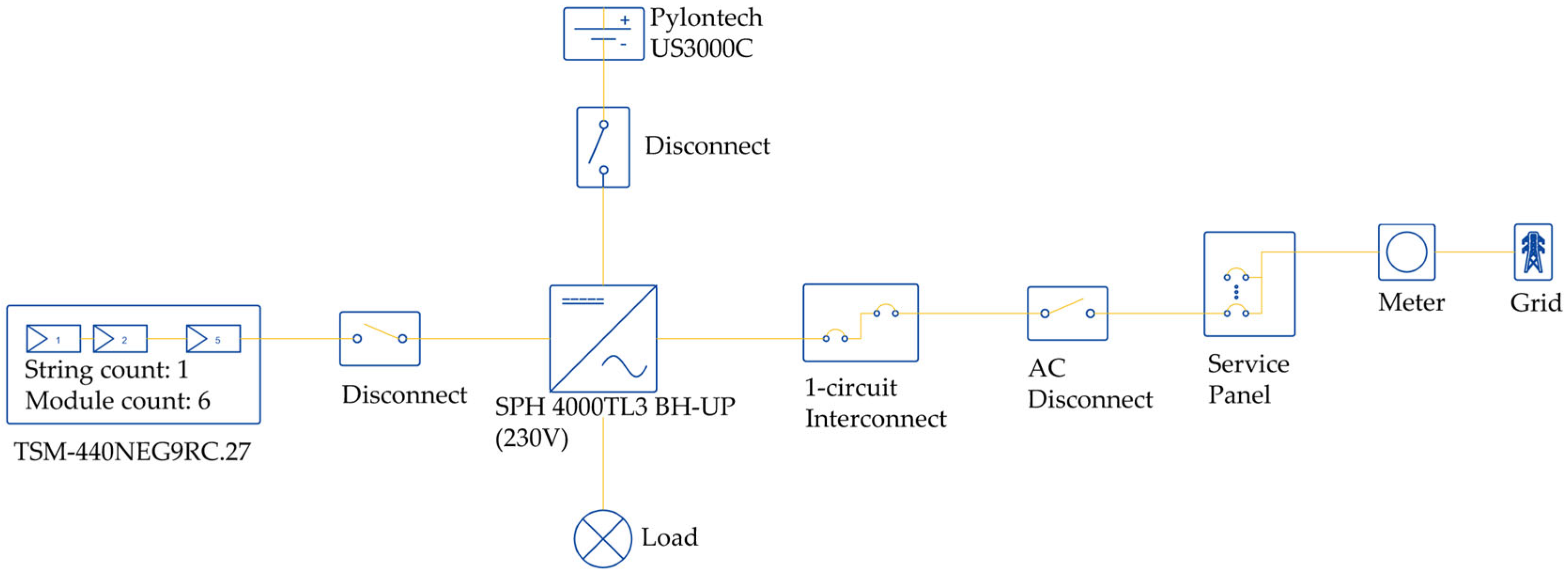

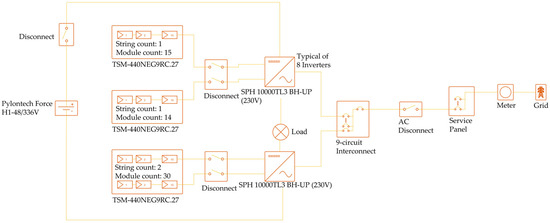

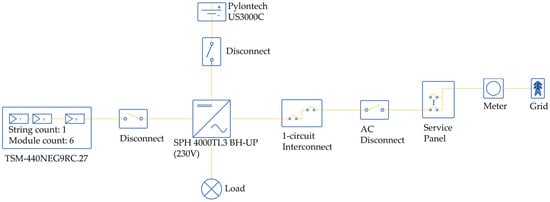

To provide a schematic diagram of the PV system configuration, Figure 5 and Figure 6 presents a schematics of the system with its main components.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of the PV systems for an institutional building.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of the PV systems for a residential household.

The photovoltaic system implemented in the institutional building consists of multiple PV arrays with different string configurations and numbers of modules, connected to hybrid inverters operating at an AC voltage of 230 V. This configuration enables efficient energy conversion, reliable supply of local loads and flexible energy management under varying operating conditions. The system architecture includes separate DC and AC disconnect switches, a multi-circuit distribution board and a grid connection via a service cabinet and metering device, ensuring operational safety, modularity and bidirectional power exchange with the electricity grid.

The residential photovoltaic system is designed primarily to cover on-site electricity consumption and to reduce reliance on the external grid. Compared to the institutional configuration, it features lower installed capacity, a simpler topology and fewer functional layers. Battery storage plays a key role in providing short-term flexibility, increasing self-consumption and enhancing energy self-sufficiency.

Photovoltaic system modeling was performed using HelioScope [56] and validated with HOMER Pro [57], while the blockchain-based energy trading platform was developed and tested using Solidity smart contracts deployed on a local Ethereum environment (Ganache) [58] and accessed via MetaMask [59] and Web3 interfaces. This approach enabled the calculation of energy flows under different operational scenarios and provided reliable input data for subsequent analyses of energy storage and blockchain-based energy trading.

The hybrid system components were selected based on their technological maturity, commercial availability and complementary operational roles, with batteries providing short-term flexibility, hydrogen enabling long-term storage and peak-load mitigation and blockchain facilitating decentralized energy exchange. Component sizing and parameter values were chosen to reflect realistic, deployable configurations suitable for both residential and institutional-scale applications. Lifetime and replacement of components were explicitly considered in the economic analysis, with battery, inverter and hydrogen subsystem replacements scheduled according to manufacturer lifetimes and implemented within the HOMER Pro feasibility calculations.

2.2. Energy Storage Modeling

To evaluate the flexibility and reliability of the hybrid system, dedicated models were developed for battery and hydrogen energy storage. The formulation considers charge–discharge dynamics, conversion efficiencies and capacity limitations, enabling a consistent assessment of energy exchange between the storage units, the photovoltaic source and the consumer load.

2.2.1. Battery Storage Model

The electrochemical energy storage subsystem is modeled through a state-of-charge (SOC) balance equation that separately accounts for the charging and discharging phases, thereby enabling high-fidelity representation of transient energy exchanges within the hybrid renewable configuration [17,32]:

The formulation is subject to the operational constraints 0 ≤ SOCt ≤ 1; 0 ≤ Pch,t ≤ Pch,max; 0 ≤ Pdist,t ≤ Pdist,max, together with the condition that prohibits simultaneous charging and discharging, although controlled relaxation can be applied during optimization to facilitate convergence:

In this model, Ebatt denotes the nominal energy capacity of the battery (kWh), ηc and ηd represent the charging and discharging efficiencies and Δt is the simulation time step (1 h). The overall round-trip efficiency, ηrt = ηc ∙ ηd, typically ranges from 0.85 to 0.95 depending on the electrochemical technology. DC–AC conversion losses are accounted for through the system loss factor fsys and inverter efficiency described in Section 2.1.

The SOC is updated dynamically based on the net charging and discharging power, corrected for efficiency losses and limited by the maximum depth of discharge (DoD). This ensures realistic cycling behavior and prevents accelerated degradation. Operational control follows a rule-based logic in which surplus photovoltaic generation charges the battery, while discharging occurs when local demand exceeds PV output.

The selected 1 h time step offers a practical balance between computational efficiency and model accuracy, with the flexibility for refinement in predictive or real-time control applications. The modular formulation also supports coupling with the hydrogen and blockchain subsystems to maintain consistent energy flow tracking across the hybrid configuration. Further details on hybrid battery architectures and control strategies in renewable systems are available in [32], with the corresponding system parameters given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the battery storage system module Pylontech Force-H1-48/336 V [60].

2.2.2. Hydrogen Storage Model (Electrolyzer-Tank-Fuel Cell)

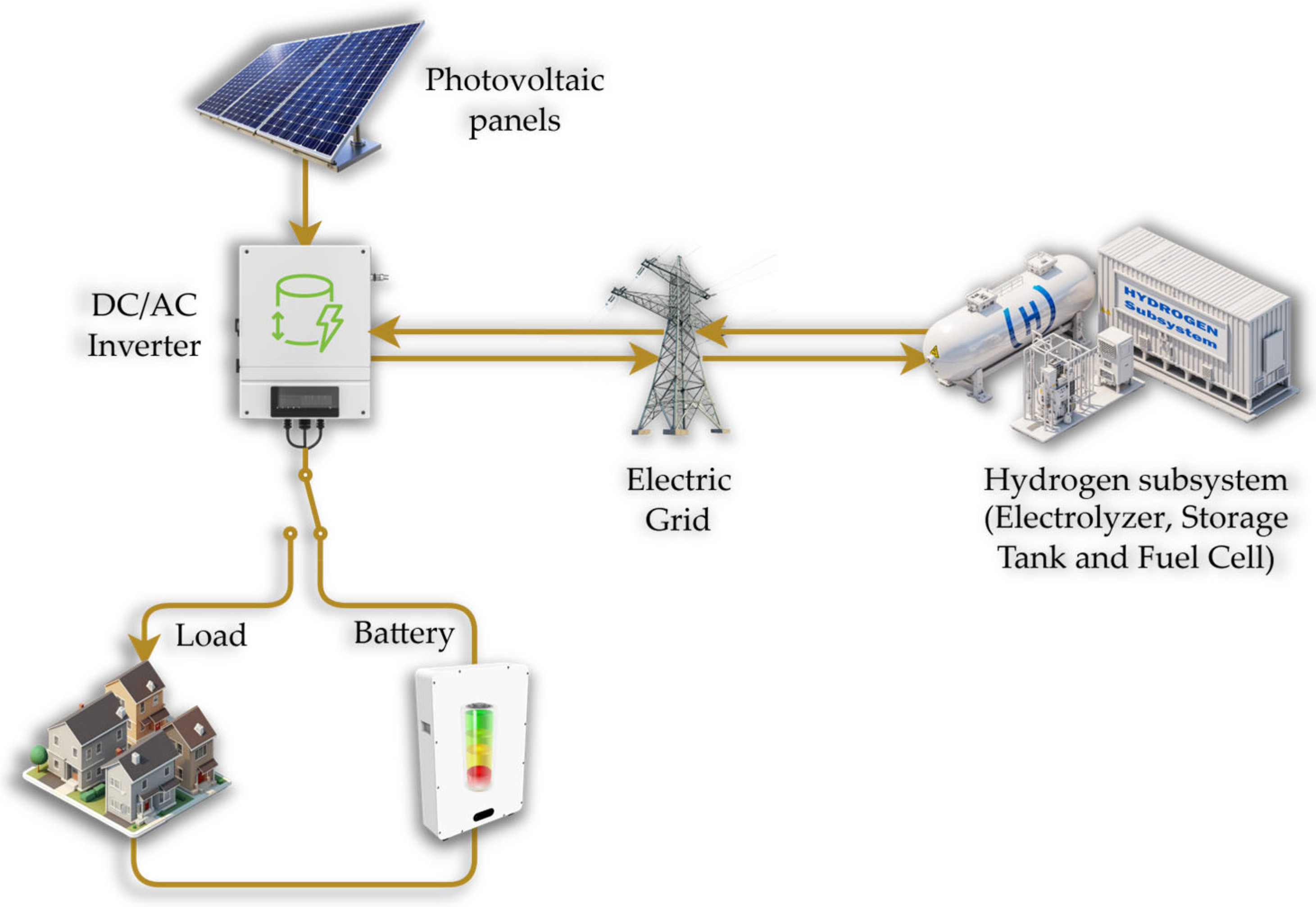

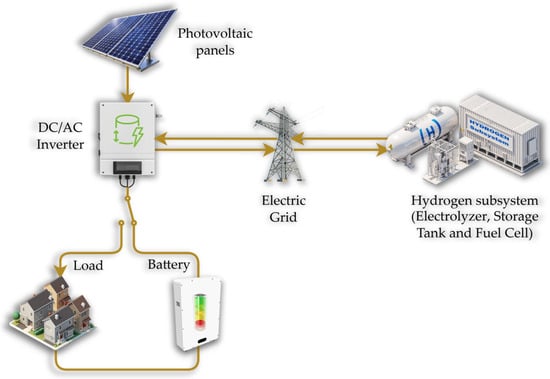

The hydrogen storage subsystem constitutes the central link between short-term electrical storage and long-term energy flexibility within the hybrid renewable architecture. It integrates three primary components: the electrolyzer, responsible for converting surplus photovoltaic energy into hydrogen; the storage tank, which retains the produced hydrogen under controlled conditions; and the fuel cell, which reconverts stored hydrogen into electricity on demand (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Physical energy flow within the hybrid PV–battery–hydrogen system connected to the external utility grid.

The figure illustrates the physical electricity and energy conversion pathways, including photovoltaic generation, battery storage, hydrogen production via electrolysis, hydrogen storage and reconversion through a fuel cell. The utility grid represents the external commercial power grid, which supplies electricity during deficit conditions and receives excess electricity when local generation and storage capacities are exceeded. While the subsequent formulations describe these coupled processes in terms of energy conversion efficiency, mass balance and system integration parameters.

- (i)

- Hydrogen production (electrolysis).

The hourly mass flow rate of the produced hydrogen, assuming the utilization of surplus electrical energy Esur,t, is calculated as follows [29]:

where ηel is the electrolyzer efficiency (ηel = 0.6) and LHVH2 ≈ 33.3 kWh/kg is the lower heating value of hydrogen. In this implementation, Esur,t represents the hourly surplus AC energy available for electrolysis.

- (ii)

- Hydrogen storage.

The mass of hydrogen in the storage tank evolves discretely according to the following relationship:

subject to the constraints 0 ≤ Mt ≤ Mmax. For a compressed hydrogen tank under typical operating conditions, storage losses ṁloss,t are generally negligible at an hourly time step [29]. However, if a cryogenic or metal hydride storage system is used, an additional loss term can be introduced.

- (iii)

- Conversion back to electricity (fuel cell).

The electrical energy output from the fuel cell is calculated as follows:

where ηFC is the fuel cell efficiency (typically 0.45–0.6 for PEM or PAFC systems in the electrical output range, depending on the load [29]). The parameters of the hydrogen subsystem, including the electrolyzer, storage tank and fuel cell, are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Parameters of the hydrogen subsystem: electrolyzer, storage tank and fuel cell [19].

On an annual basis, the round-trip efficiency of the hydrogen subsystem is estimated as ηH2,rt = ηel ∙ ηFC, neglecting minor storage losses. Typical values range between 0.25 and 0.35 [29,32].

Operationally, in the peak-shaving scenarios, a target maximum grid power Pmax is defined and the fuel cell energy output EFC,t is dispatched such that maxt (Pload,t − EFC,t) ≤ Pmax, subject to the available hydrogen storage Mt. This approach was applied in the practical case study, where operational decisions were made based on the difference between the instantaneous peak demand and the predefined target level.

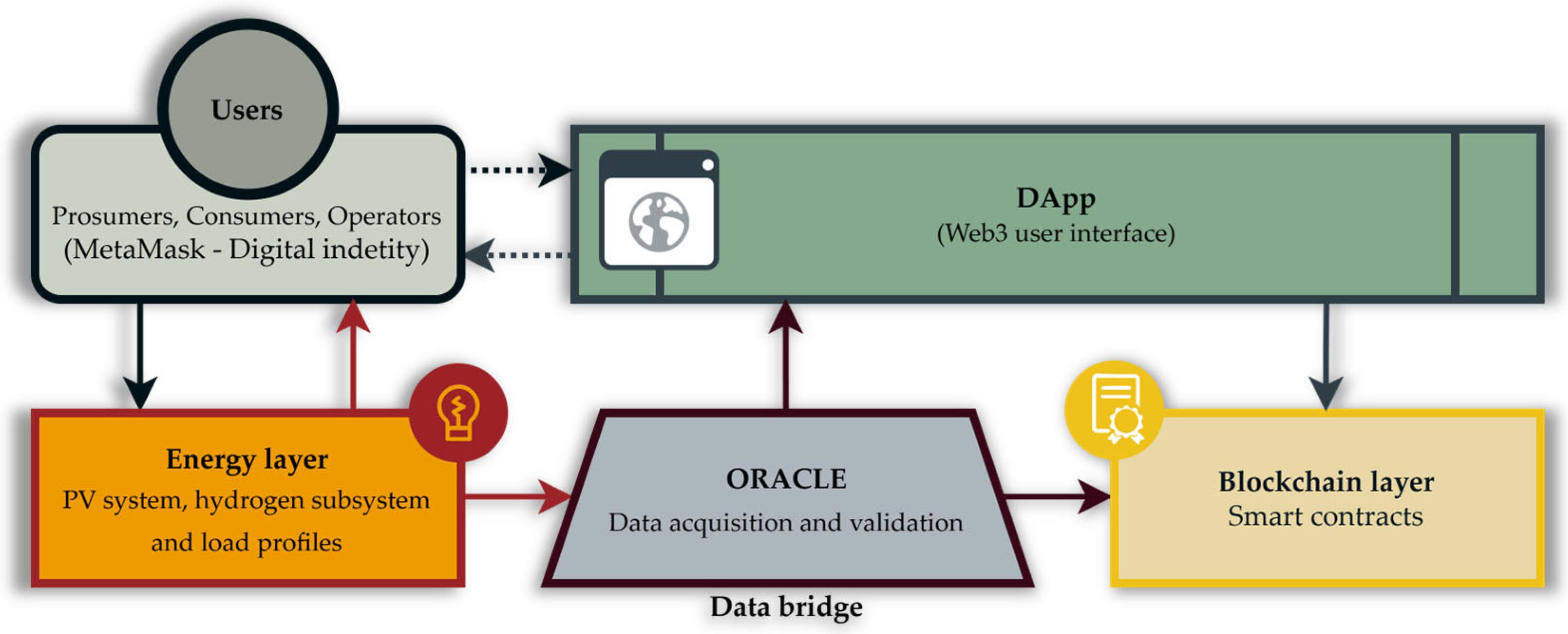

2.3. Blockchain-Based Energy Trading Platform

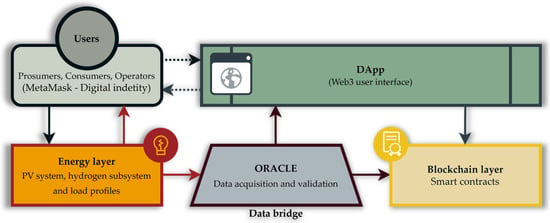

The proposed blockchain-based electricity trading model was developed to enable transparent, secure and decentralized exchange of surplus energy between prosumers and consumers. The system architecture comprises several layers: the energy layer, data measurement and acquisition layer (off-chain), blockchain layer (on-chain), application layer and the identity and participant management layer. This structure establishes an integrated framework that connects the physical generation and consumption of energy with the corresponding digital transaction records within the blockchain network [61].

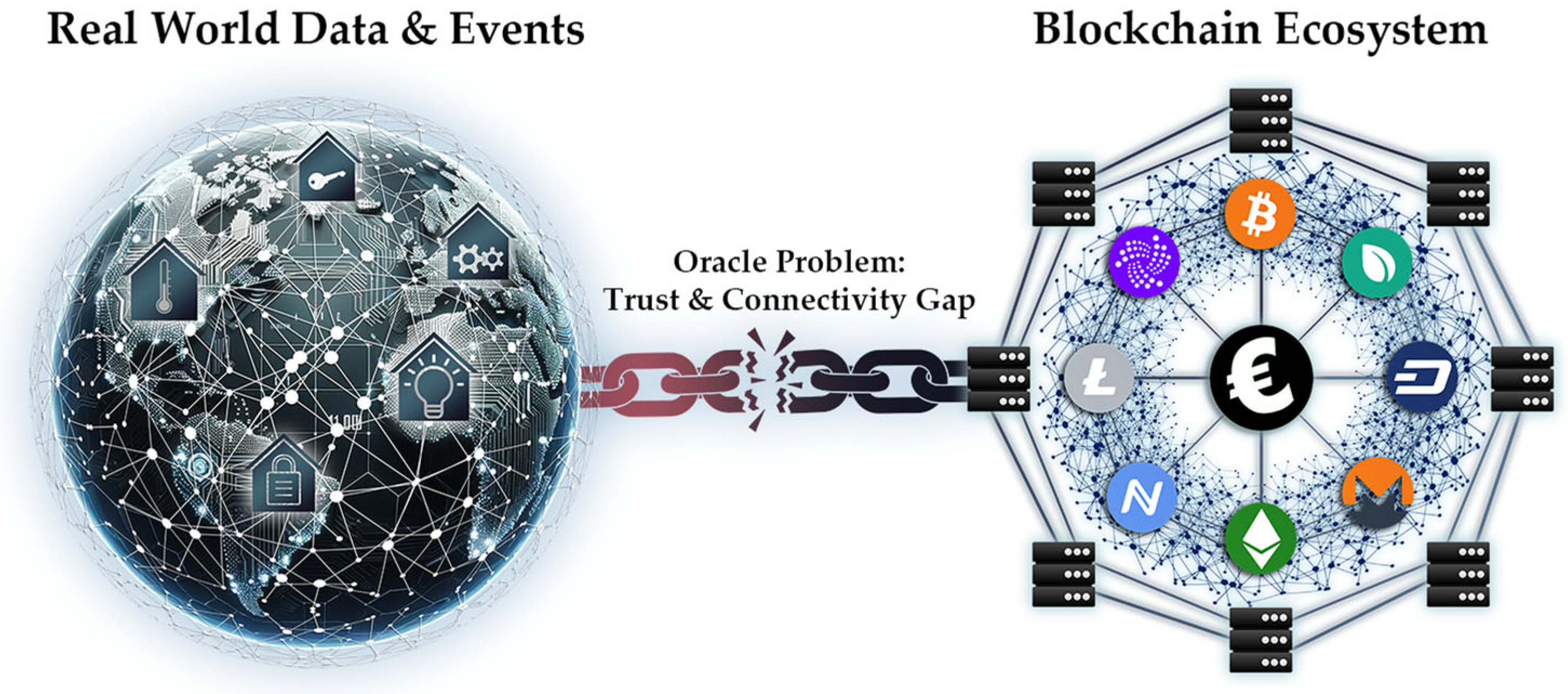

Within the energy layer, the previously generated surplus electricity is made available for trading. The surplus energy Esur,t represents the excess stored in any of the energy storage units (hydrogen tank or battery), taking into account conversion losses associated with energy discharge. In a real-world implementation, measurements would be performed using meters and inverters and the data would be transmitted to the smart contract through an oracle mechanism. The oracle ensures data integrity and reliability, thereby preventing manipulation and guaranteeing the authenticity of trading records, as emphasized in several European pilot projects.

The blockchain layer incorporates a smart contract named EnergyMarket, developed in the Solidity programming language, which performs the core functions of posting offers, matching bids and executing transactions. The transaction model is based on an order-book mechanism expressed in kilowatt-hours (kWh), with all trades recorded as immutable entries on the blockchain. Participants use MetaMask digital wallets for authentication and transaction signing, while a local blockchain network (Ganache) is employed for testing and validation. This approach aligns with recent studies that identify blockchain technology as a key enabler for decentralized demand management and P2P energy exchange in smart grids.

At the application layer, a decentralized web application (DApp) was developed to enable user interaction with the smart contract through an intuitive web interface built with Node.js, HTML and JavaScript. Through the DApp, participants can submit offers to sell or purchase energy, monitor the status of active orders and review the history of completed transactions. Communication between the DApp and the blockchain is established via the Web3 interface, while all events (e.g., OfferCreated and TradeExecuted) are emitted and displayed to users in real time. The overall system architecture and data flow between these layers are illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Schematic architecture of the blockchain-enabled energy trading platform integrating photovoltaic system and hydrogen subsystems.

Users are classified into three groups: prosumers (producer–consumers), consumers and optionally an operator or community entity responsible for system supervision. Each user’s identity is linked to their blockchain address, while access rules can be further defined within permissioned blockchain networks. This approach ensures transparency and equality among participants, with the operator’s role limited to coordination rather than centralized control.

To clearly illustrate the roles of participants and technical components, Table 4 provides a summary of the entities and their respective functions within the system.

Table 4.

Entities and roles within the P2P energy trading platform.

Functional testing was performed under several scenarios, including successful trade execution under valid conditions, trade rejection due to parameter mismatches, verification of offer states when buy and sell quantities were not aligned and prevention of unauthorized participation. The results confirm that the smart contract operates correctly in all tested cases, thereby demonstrating the technical feasibility of the proposed P2P energy exchange model. It should be noted that the testing did not include the data bridge between the off-chain and on-chain environments; the system was simplified to include all previously described layers except the oracle layer. Such testing procedures correspond to validation approaches increasingly reported in the literature and P2P market simulations.

The link with European pilot projects further reinforces the practical relevance of the proposed solution. The NRGcoin concept [43] introduces an energy unit as a tokenized instrument, the Brooklyn Microgrid project [48] emphasizes the role of local communities in energy trading, while the Pylon Network [49] focuses on the transparency of energy data. The literature also indicates that blockchain-based markets are increasingly viewed in the context of the energy transition and the formation of trust-based energy communities. The proposed model builds upon these experiences by integrating PV systems, energy storage technologies (battery and hydrogen) and blockchain mechanisms for surplus energy exchange within a unified, experimentally tested framework.

2.4. Economic Inputs

An inflation rate of 2.5% was assumed in the economic analysis, based on inflation data for the Republic of Croatia over the past 13 years. The project lifetime was set to 30 years, while additional project-related costs (documentation, consumables and miscellaneous expenses) were assumed to be 2000 € for the Mechanical Engineering Faculty and 1500 € for the residential household.

Electricity purchase prices for the renewable energy system simulations were determined from [62] by aggregating electricity energy prices (€/kWh), distribution charges (€/kWh), renewable energy surcharges and transmission fees for both high and low tariff periods. In addition to energy-based charges, fixed supply and metering fees were included on a monthly basis (€/month). All cost components include a value-added tax (VAT) of 13%.

The final electricity prices used in the simulations were 0.1588 €/kWh for the high tariff (VT), 0.0827 €/kWh for the low tariff (NT) and 2.85 €/month (34.2 €/year) for supply and metering. The electricity feed-in price was assumed to be 50% of the high-tariff purchase price (0.074789 €/kWh), resulting in a selling price of 0.0374 €/kWh.

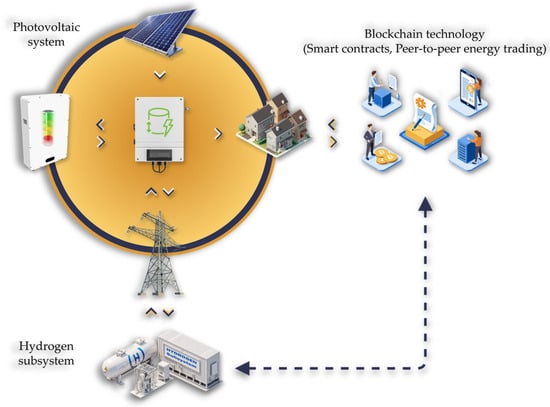

2.5. Integration of PV, Storage and Blockchain Models

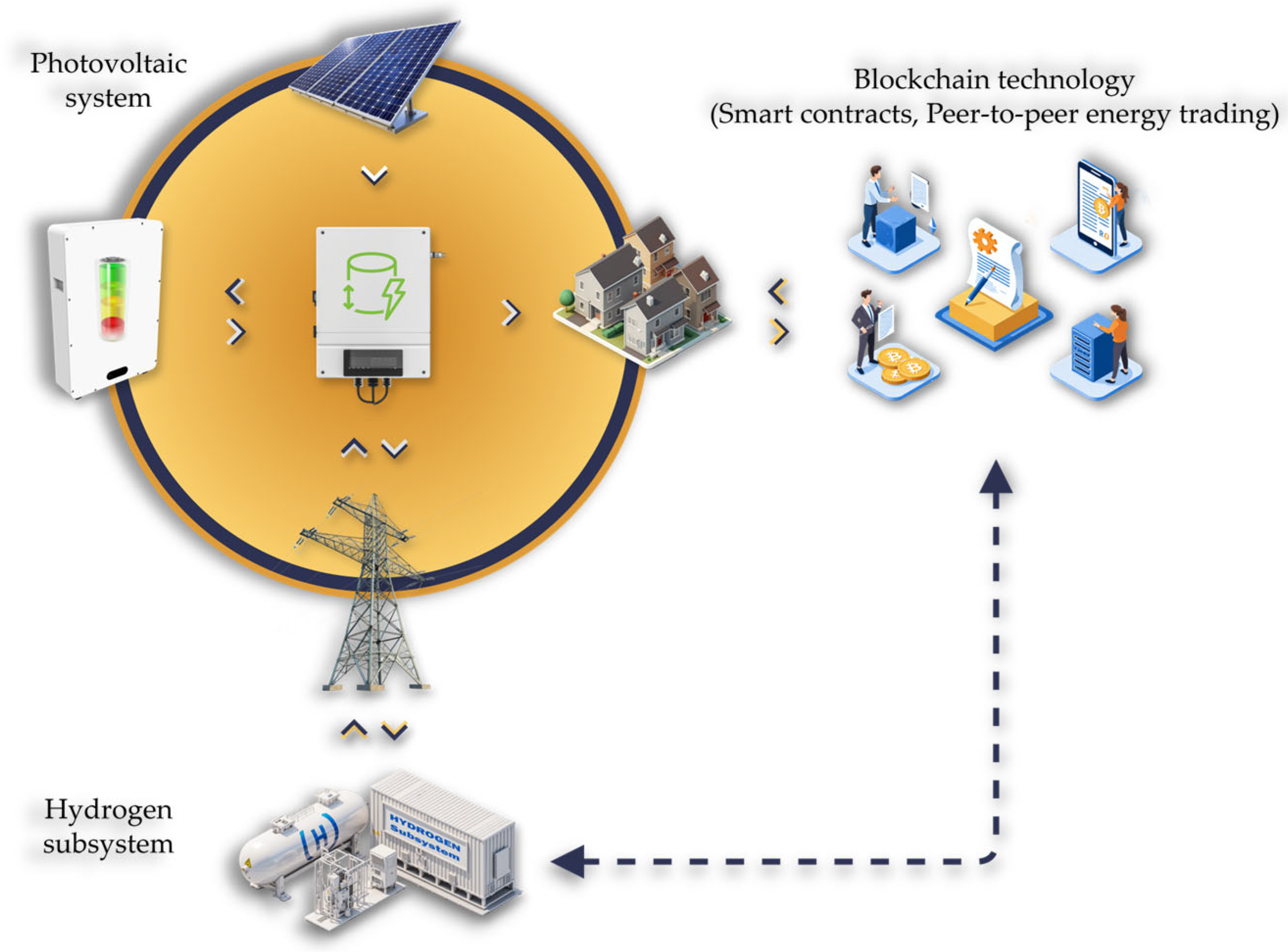

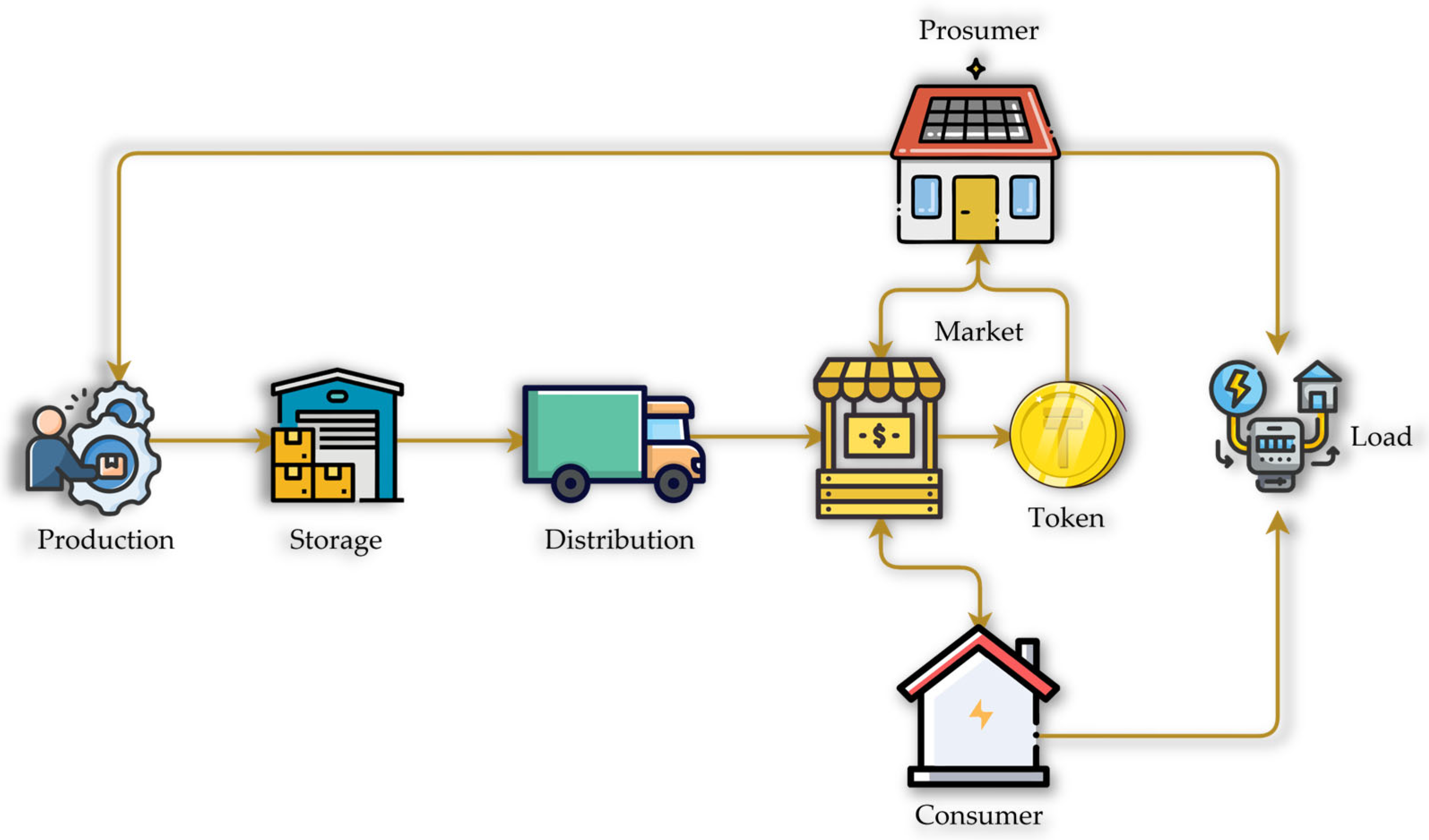

The integration of the PV, energy storage units and blockchain platform forms a comprehensive hybrid energy ecosystem capable of generating, storing and exchanging electricity under decentralized management conditions (Figure 9). Each subsystem has been described in detail in the preceding sections, while this part focuses on their interaction and functional interconnection [29,32].

Figure 9.

Integrated hybrid energy system combining physical power infrastructure and a blockchain-based peer-to-peer (P2P) trading layer.

Energy flows are defined according to supply priorities. The electricity generated by the PV system is first used to satisfy the instantaneous demand of the facility. In the case of surplus generation, the excess energy is directed to the battery storage system. The stored energy, as well as any additional surplus, can either be offered to other participants through the blockchain platform or converted into hydrogen via the electrolyzer and stored in the H2 tank, providing long-term energy accumulation and the capability for peak-load mitigation. In this context, blockchain can play a crucial role by enabling surplus electricity trading without requiring physical energy conversion (electricity–hydrogen), or by facilitating electricity trading even after conversion (hydrogen–electricity), while accounting for the conversion losses.

Conversely, under supply deficit conditions, the demand is met sequentially: first from PV generation, then from the battery storage system, followed by the fuel cell utilizing the stored hydrogen and finally through energy purchases from other participants on the blockchain market. This approach enables the optimal utilization of local resources while enhancing the system’s energy independence and operational flexibility.

The mathematical framework of the integration can be expressed through the energy balance equation for a given time step t:

where EPV,t is the energy generated by the PV system (kWh), Ebat,dis,t is the energy discharged from the battery (kWh), EH2,FC,t is the energy produced by the fuel cell (kWh), Ein,P2P,t is the energy purchased through the blockchain platform (kWh), Eload,t is the energy consumption of the facility (kWh), Ebat,ch,t is the energy used for battery charging (kWh), EH2,el,t is the energy consumed for hydrogen production in the electrolyzer (kWh) and Eout,P2P,t is the energy sold through the blockchain platform (kWh).

3. Results

The performance of the integrated photovoltaic, battery and hydrogen subsystems was evaluated through detailed techno-economic simulations. The results are presented in terms of electricity generation, storage utilization, system autonomy and economic performance for two representative consumer categories: a medium-scale institutional building and a single-family residential household. A comparison of these scenarios reveals how the system scale, storage configuration and operational strategy influence overall efficiency, self-sufficiency and cost-effectiveness in hybrid renewable energy deployment.

3.1. Technological and Economic Performance of the Hybrid System

The simulation results were obtained for two representative consumer types: a building of a scientific and educational institution and a residential household. This approach enables a comparison of different scales of hybrid PV system implementation integrating battery storage and the hydrogen subsystem.

3.1.1. Electricity Generation and Consumption

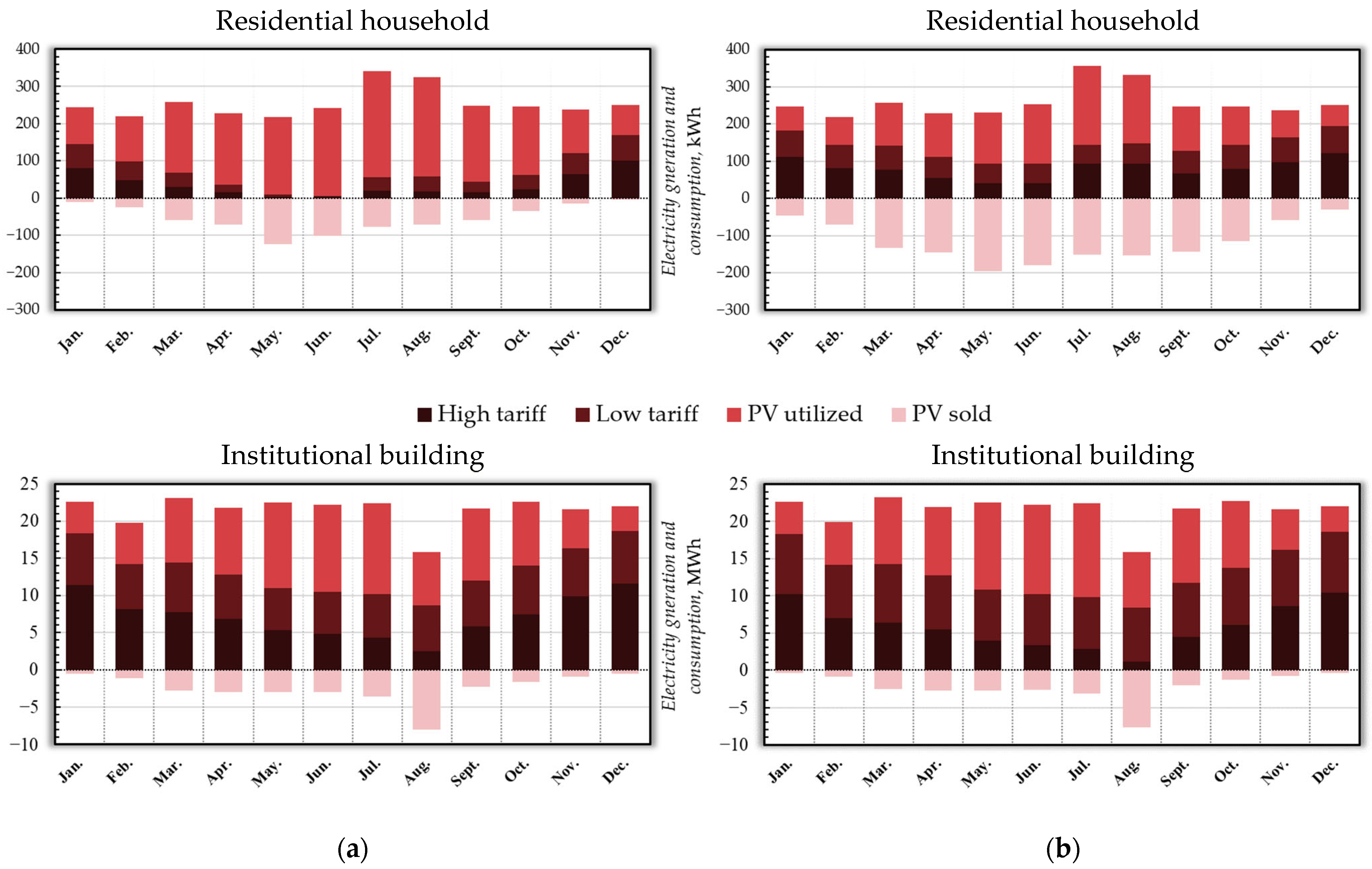

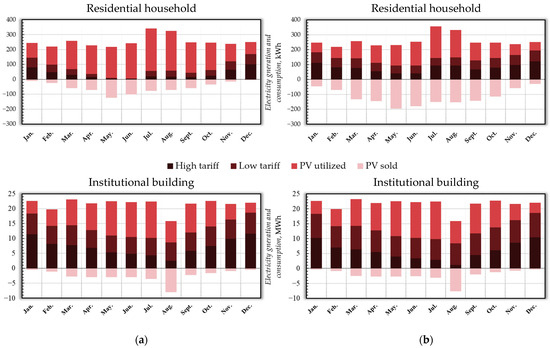

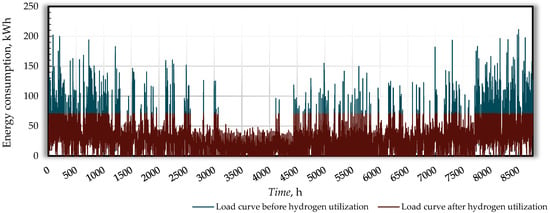

Electricity generation and consumption profiles were evaluated for two representative consumer types, an institutional building and a residential household, under different operating conditions. Monthly electricity balances were determined for configurations with and without battery storage, capturing variations in photovoltaic generation and electricity demand over the year. The resulting monthly electricity generation and consumption profiles for both systems are presented in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Monthly electricity generation and consumption for (top) the residential household and (bottom) the institutional building. (a) with battery storage; (b) without battery storage.

For the institutional building, the annual electricity generation from the photovoltaic system is approximately 127 MWh, while total annual electricity consumption ranges between 159 and 161 MWh, depending on the inclusion of battery storage. In the configuration without battery storage, approximately 30 MWh of surplus electricity is exported to the grid. When battery storage is integrated, exported electricity decreases to approximately 27 MWh.

For the residential household, the annual photovoltaic electricity generation amounts to 2839.35 kWh. Grid electricity purchases decrease from approximately 1682 kWh in the configuration without battery storage to about 877 kWh when battery storage is installed. Correspondingly, electricity exported to the grid decreases from approximately 1424 kWh without battery storage to approximately 653 kWh with battery storage.

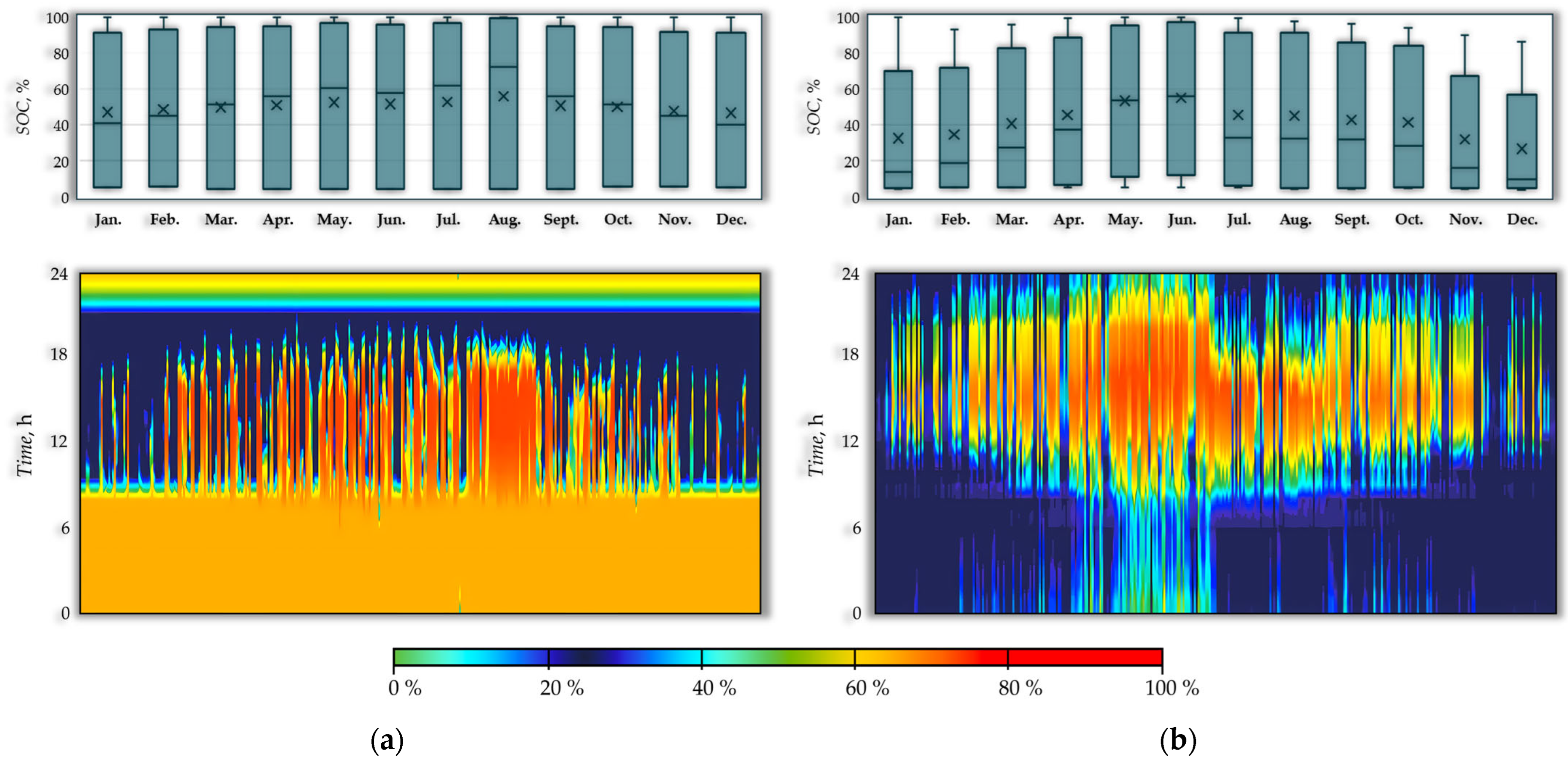

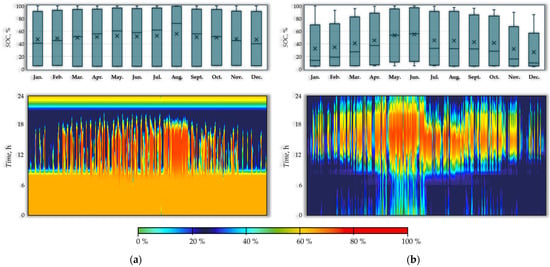

3.1.2. Battery Storage System

For the institutional building, a configuration comprising two Pylontech Force-H1-48/336 V battery units was implemented, providing approximately 97 min of energy autonomy. The state-of-charge (SOC) profiles indicate frequent charging and discharging cycles, particularly during the summer months, when surplus photovoltaic generation is highest.

For the residential household, a single Pylontech US3000C battery with a nominal capacity of 3.5 kWh was installed, providing approximately 10 h of energy autonomy. The SOC profiles show lower cycling intensity compared to the building-scale system. The monthly distribution and daily evolution of the battery state of charge for both systems are presented in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Battery state of charge for (a) the institutional building and (b) the residential household.

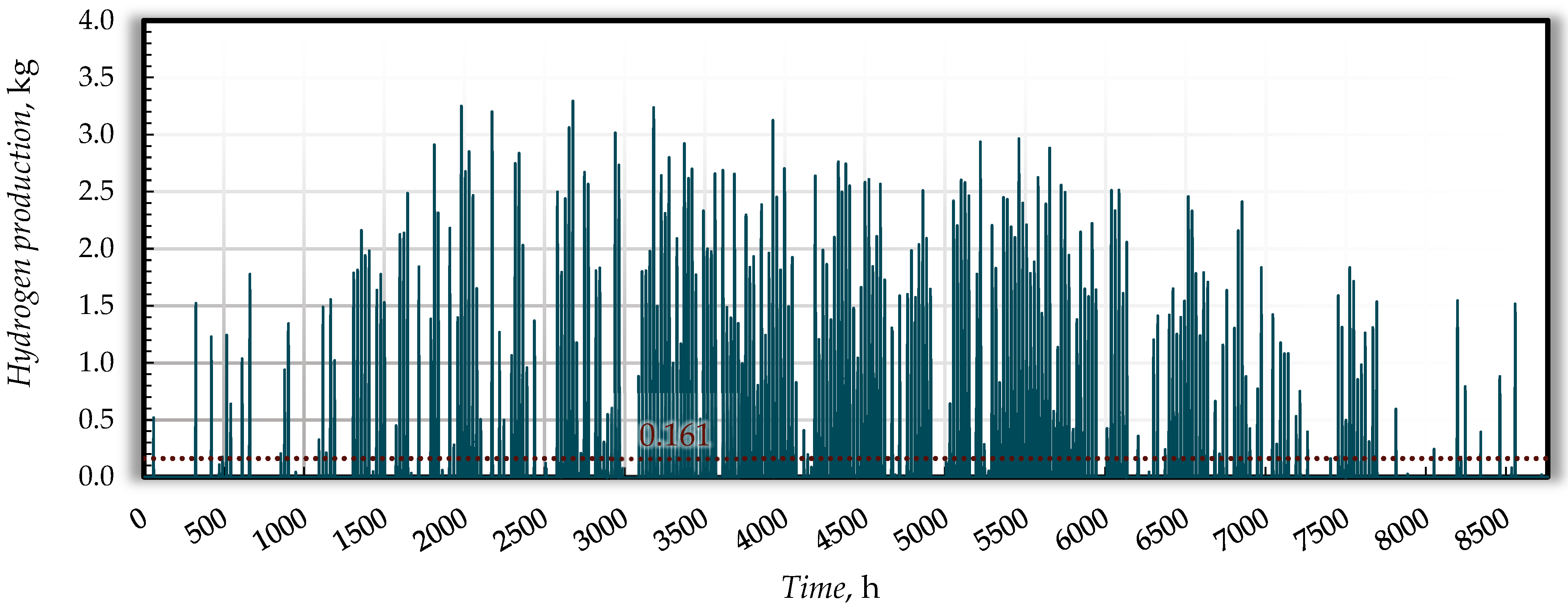

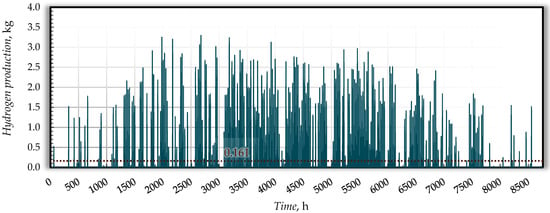

3.1.3. Hydrogen Subsystem

Surplus electricity not absorbed by the battery storage system was converted into hydrogen using a PEM electrolyzer. For the institutional building, a 220 kW electrolyzer with an efficiency of approximately 60% produces up to 1414.1 kg of H2 per year from the available surplus electricity. The hourly hydrogen production over the year is shown in Figure 12. The average hydrogen production rate is approximately 0.161 kg/h, with a maximum hourly production of 3.29 kg/h.

Figure 12.

Hourly hydrogen production during the year and the average day.

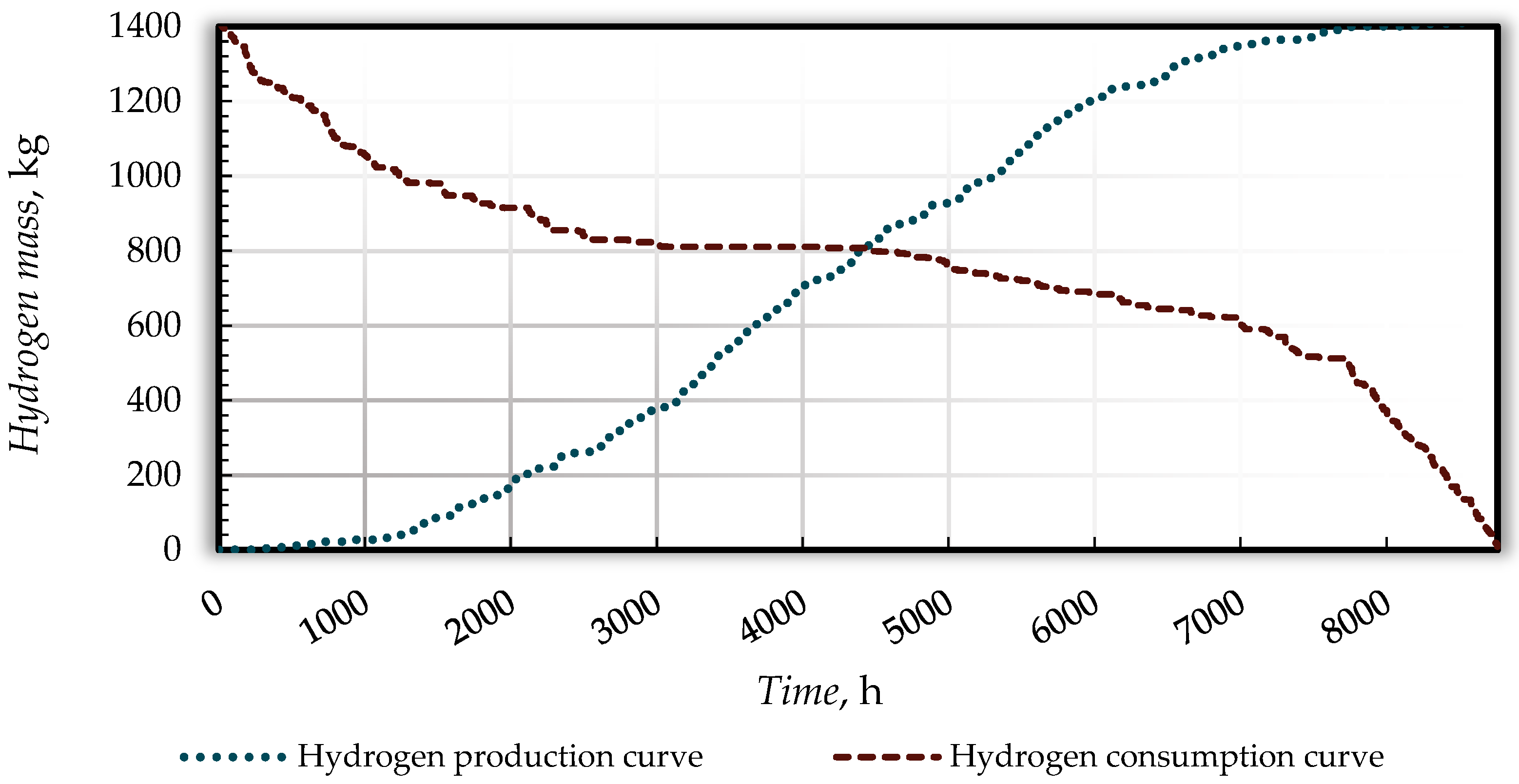

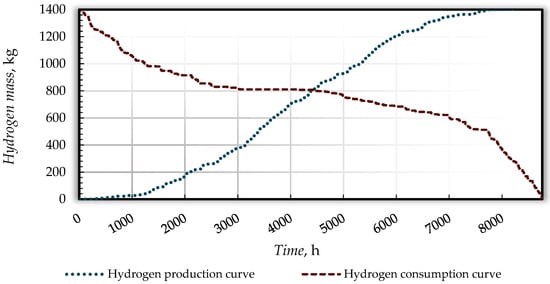

The hydrogen production profile exhibits pronounced temporal variability over the year, with higher production levels occurring during periods of increased photovoltaic electricity surplus. The cumulative hydrogen production and associated storage evolution are presented in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Demand coverage and hydrogen storage sizing (560 kg of H2).

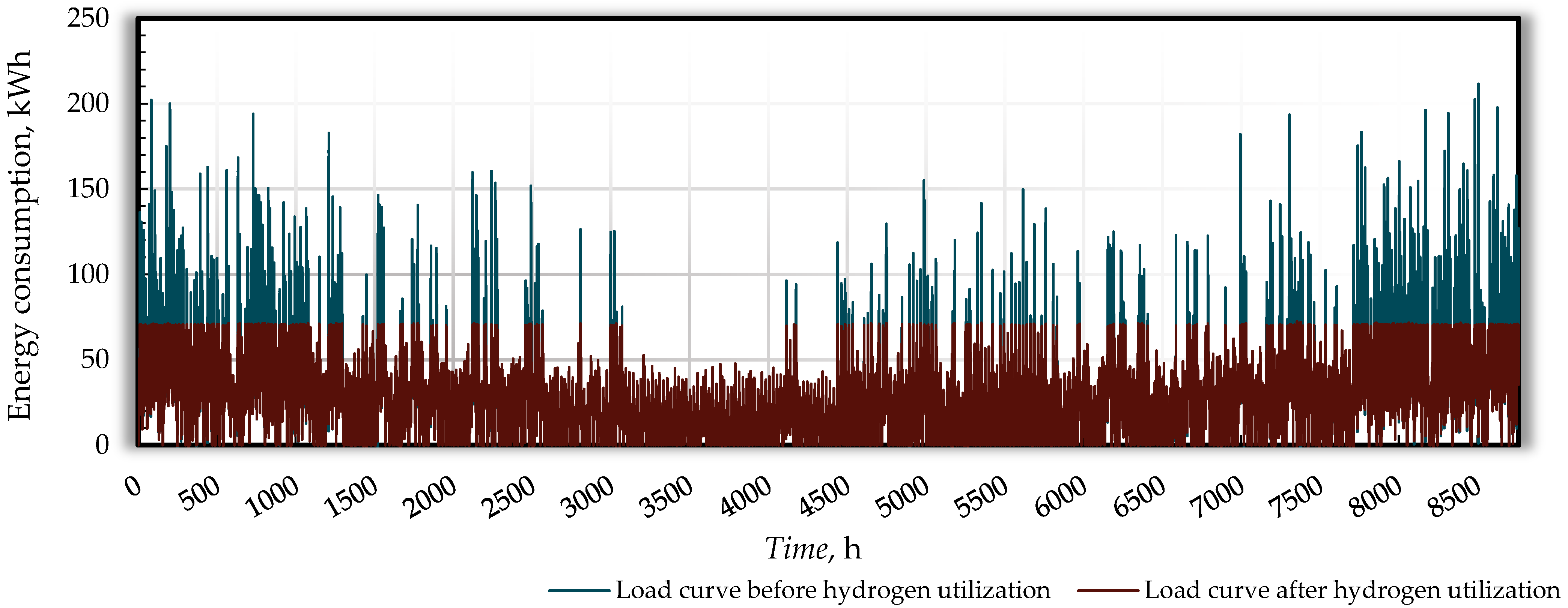

The operation of a 140 kW fuel cell was analyzed to quantify its contribution to peak-load reduction within the hybrid PV–battery–hydrogen system. The resulting peak-load profiles with and without fuel cell operation are presented in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

Peak-load reduction achieved using a 140 kW fuel cell.

The peak-load analysis shows that the maximum electricity demand of the institutional building decreases from approximately 209.7 kWh to 70.65 kWh when the fuel cell is engaged. To support this operating mode, a hydrogen storage capacity of approximately 560 kg H2 is required. For the residential household, the total amount of hydrogen produced is substantially lower due to limited surplus electricity.

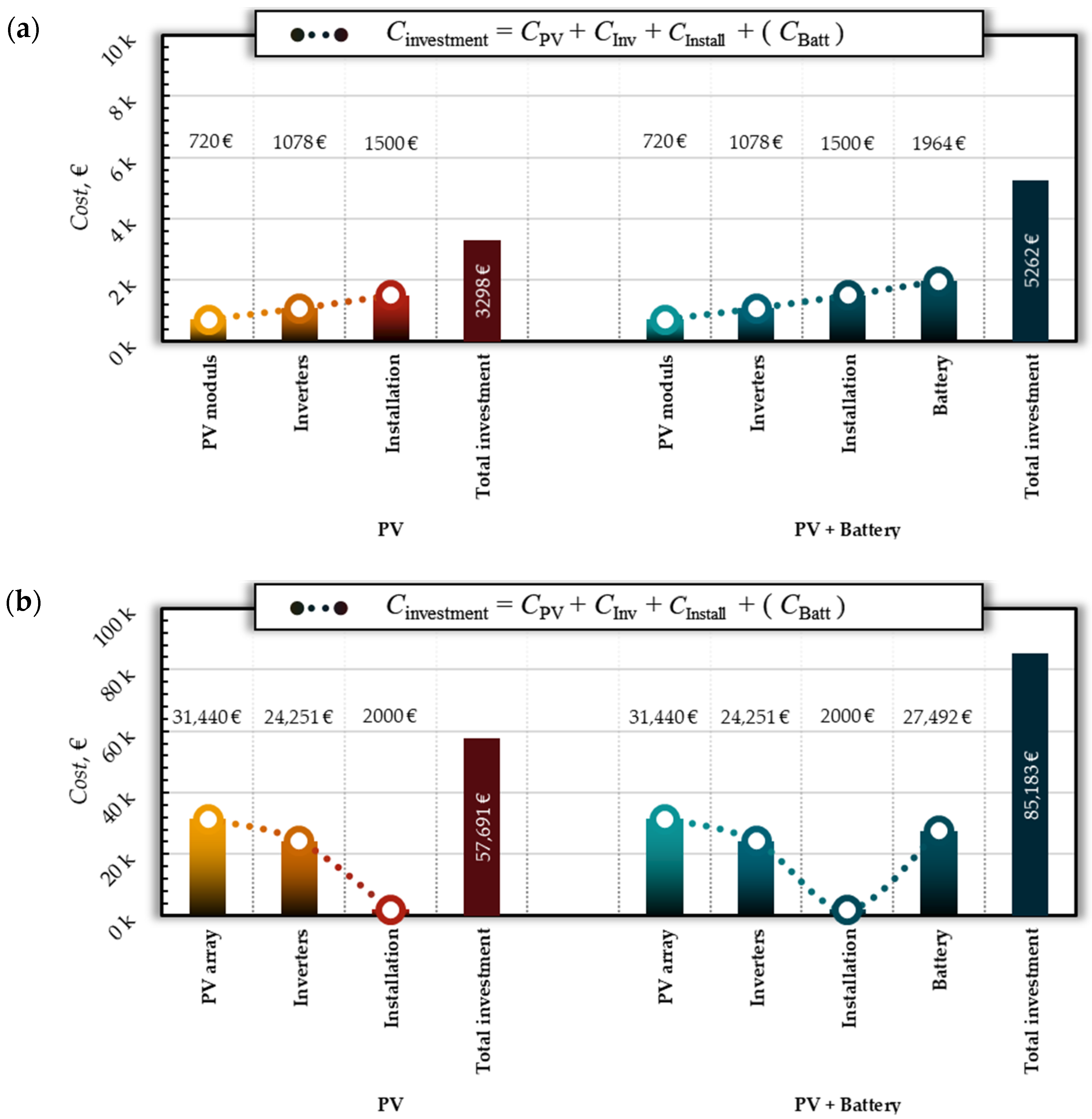

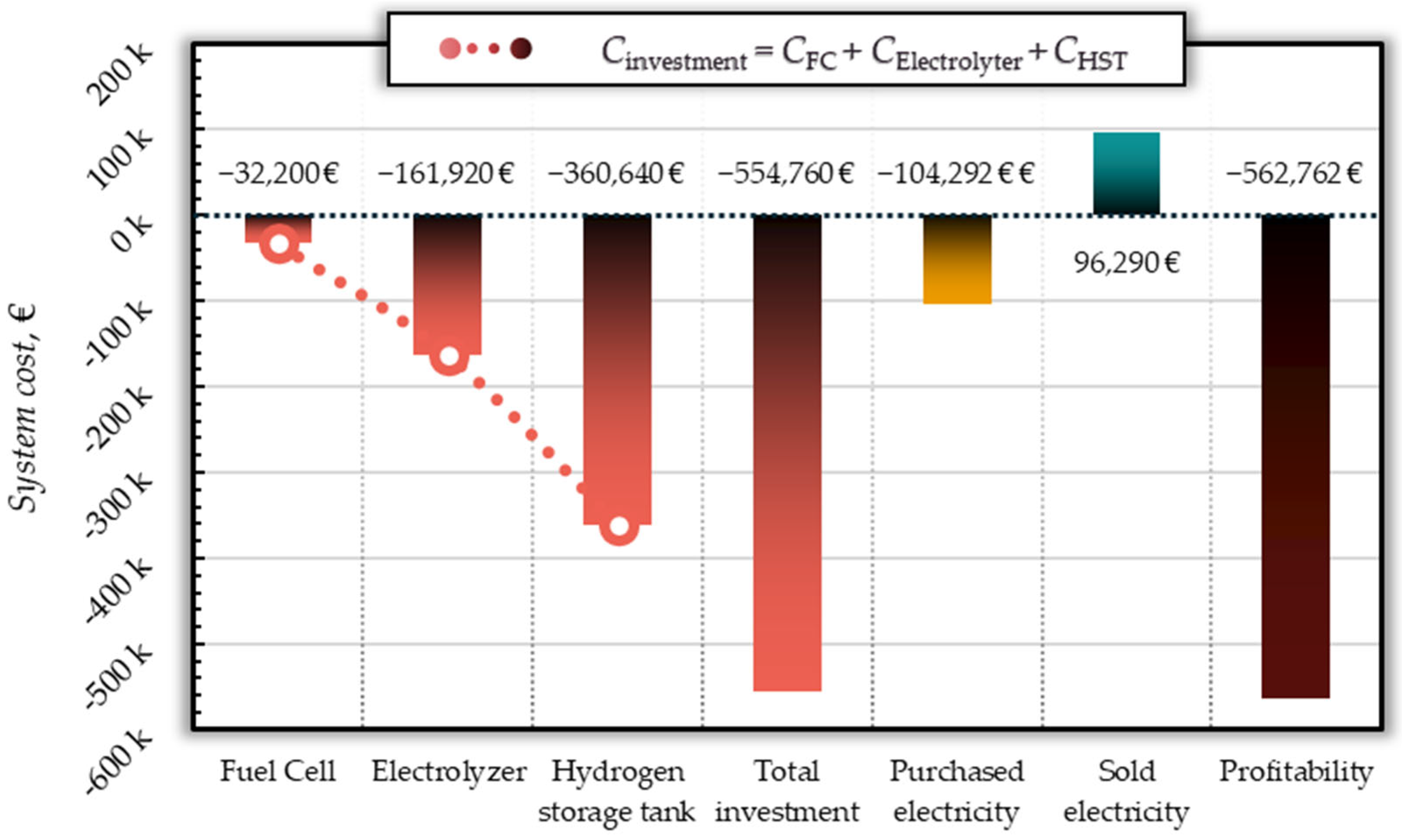

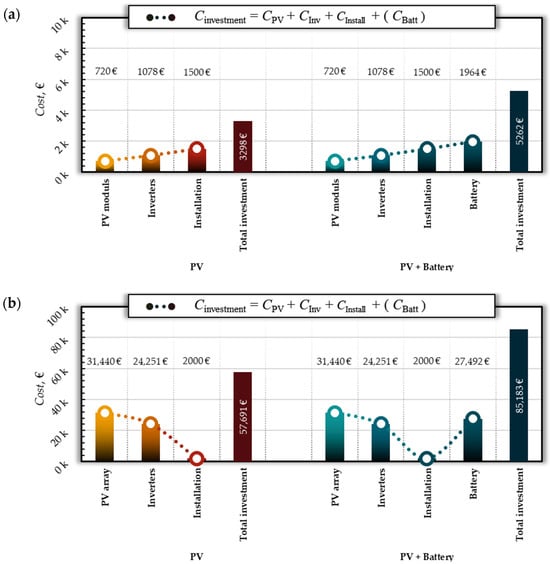

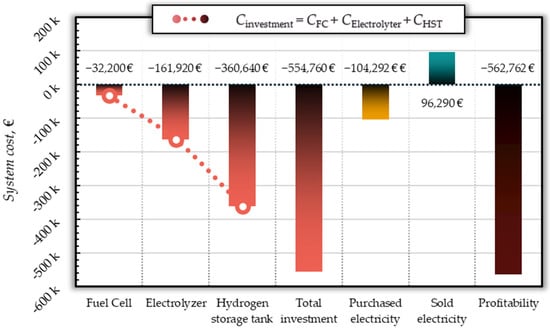

3.1.4. Economic Analysis

The cost analysis compares three system configurations: standalone PV, PV with battery storage and PV with combined battery and hydrogen storage. The estimated investment costs for PV systems with and without battery storage are presented in Figure 15, while the total system costs for the hydrogen-integrated configuration are shown in Figure 16.

Figure 15.

Estimated photovoltaic system costs with and without battery for (a) the building and (b) the household.

Figure 16.

Estimated total system costs for the hydrogen-integrated scenario.

For the institutional building, the absolute amounts of electricity generation and consumption are several times higher than those observed for the residential household.

These differences are reflected in higher total energy flows and larger installed system capacities, which are accompanied by higher absolute emission reductions and longer payback periods compared to the residential case.

For the residential household, the integration of battery storage reduces purchased grid electricity by more than 45%, indicating a substantial increase in on-site electricity utilization.

For the institutional building, the PV + battery configuration achieves a payback period of approximately 3–4 years, while the corresponding PV-only configuration exhibits a slightly longer payback period. For the residential household, the payback period is approximately 17 years for the PV-only system and 21–22 years for the PV + battery configuration. When co-financing or subsidy schemes are applied, the residential payback period decreases to approximately 7–8 years.

Battery storage systems exhibit round-trip efficiencies of approximately 85–95%, whereas hydrogen storage systems achieve round-trip efficiencies of approximately 25–35%, as summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Comparison of battery and hydrogen storage technologies in terms of round-trip efficiency, relative investment cost and primary operational role within the hybrid energy system.

For the analyzed building-scale system, the hydrogen subsystem accounts for more than 60% of the total additional investment beyond the photovoltaic system, whereas battery storage represents less than 25% of this additional investment. In the hydrogen-integrated configuration, peak-load levels are reduced compared to configurations without hydrogen storage.

3.2. Environmental and Blockchain Aspects

The environmental performance and digital integration of the analyzed hybrid renewable energy systems were evaluated alongside their techno-economic characteristics. Environmental indicators associated with photovoltaic generation combined with battery and hydrogen storage were quantified, and the functional implementation of blockchain-based mechanisms within the hybrid system was assessed. The corresponding results are presented in the following sections.

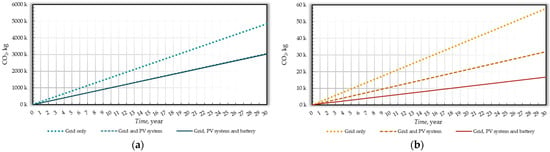

3.2.1. Emissions Reduction Through Hybrid PV Systems

Operational greenhouse gas emissions were quantified for all analyzed system configurations. For both the scientific–educational institution and the residential household, the PV + battery configuration results in lower emissions compared to grid-only operation and PV systems without energy storage. Emission indicators for CO2, SO2 and NOx, calculated over a 30-year operational lifetime, are summarized in Table 6. For the institutional building, the PV system accounts for the majority of the emission reduction, with battery storage providing an additional reduction. In the residential household, the PV + battery configuration yields a larger relative reduction in emissions due to decreased grid electricity imports.

Table 6.

Emissions of harmful gases over the 30-year system lifetime.

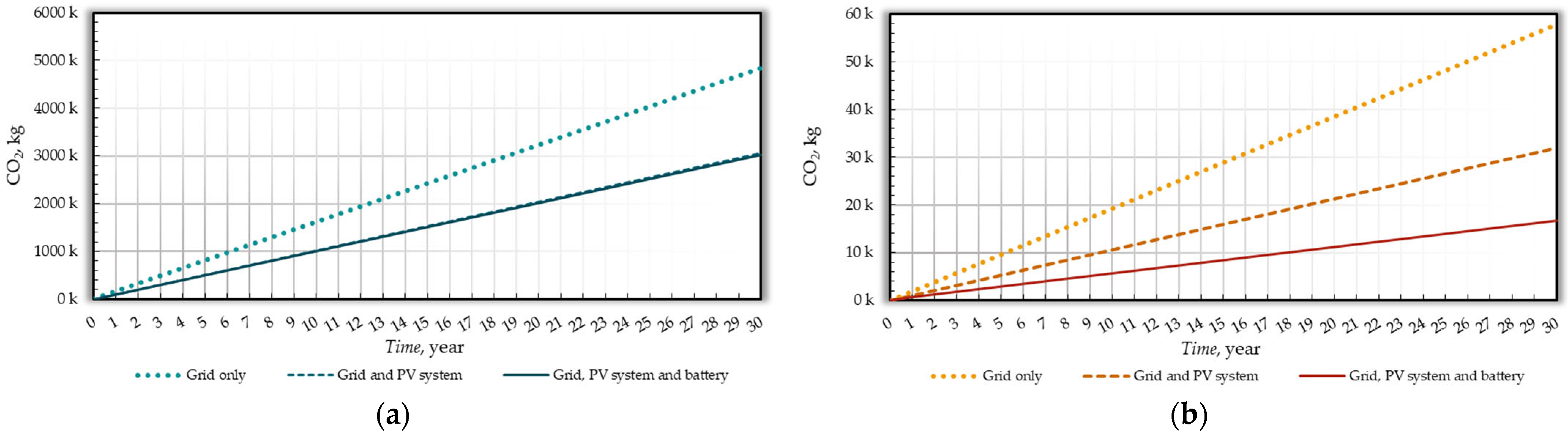

The emission values reported in Table 6 include only operational-phase emissions associated with electricity consumption and generation. Figure 17 presents the CO2 emission trajectories for the different energy system configurations for both the institutional building and the residential household.

Figure 17.

CO2 emission trends: (a) building; (b) household.

In both cases, the PV + battery configuration results in lower CO2 emissions than the grid-only configuration, with a larger relative reduction observed for the residential household.

3.2.2. Blockchain Integration for Energy Exchange

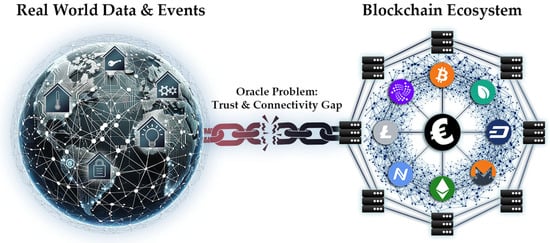

The blockchain-related results focus on the functional validation of decentralized energy trading within the modeled hybrid PV–battery–hydrogen system. A decentralized application (DApp) was developed to enable peer-to-peer electricity exchange through smart contracts. Figure 18 illustrates the integration of off-chain data with on-chain logic using an oracle-based approach.

Figure 18.

Integration of off-chain and on-chain data (oracle) for automated decision-making [63].

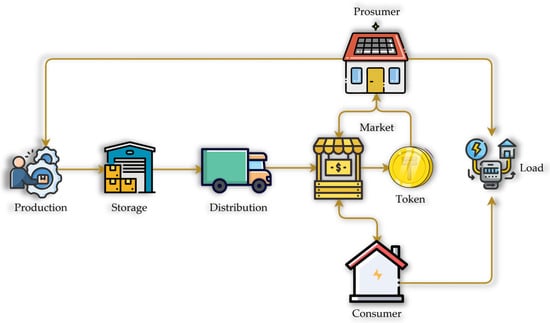

Within the simulation environment, a decentralized application (DApp) was developed and tested to connect the physical energy layer with the blockchain network. The implemented smart contract enables users to submit buy and sell offers, while automated matching and transaction settlement are performed on-chain. Figure 19 illustrates the concept of energy tokenization for the digital representation and exchange of electricity units.

Figure 19.

Energy tokenization within the energy ecosystem.

The blockchain platform was implemented and validated in a local test environment to assess the functional correctness of decentralized peer-to-peer electricity trading within the hybrid PV–battery–hydrogen system. Functional tests confirmed correct execution of core operations, including trade execution, bid validation, participant identification and settlement of exchanged energy quantities. The results demonstrate that smart contracts operate as intended for the exchange of electricity generated from photovoltaic systems and released from battery and hydrogen storage units.

4. Discussion

The results demonstrate strong interdependencies between system scale, storage configuration and operational strategy in hybrid renewable energy systems integrating photovoltaic generation, battery storage, hydrogen technologies and blockchain-based energy trading.

Monthly electricity profiles exhibit pronounced seasonal variability caused by the temporal mismatch between photovoltaic generation and electricity demand. Battery storage mitigates this mismatch by increasing on-site utilization of generated electricity, thereby reducing grid dependency and surplus energy export. This effect is more pronounced in residential systems, where closer alignment between photovoltaic production and household demand leads to a higher relative reduction in grid electricity purchases. In contrast, institutional buildings already benefit from strong daytime load alignment with photovoltaic generation, resulting in a smaller relative impact of battery storage on surplus reduction, while still improving overall energy self-sufficiency.

Differences in battery utilization are primarily governed by system scale and load characteristics. Institutional buildings exhibit higher and more continuous daytime electricity demand, leading to frequent battery cycling during periods of high photovoltaic generation. Conversely, lower cycling intensity in the residential case reflects a mismatch between available photovoltaic surplus and installed battery capacity, indicating potential for improved utilization with increased photovoltaic capacity. Overall, the observed state-of-charge dynamics confirm the role of battery storage in enhancing self-sufficiency and supporting peak-load management under variable generation and demand conditions.

Hydrogen production closely follows the temporal availability of surplus photovoltaic electricity, confirming that hydrogen generation in the analyzed system is driven by excess renewable energy rather than base-load operation. This positions the electrolyzer as a complementary pathway to battery storage rather than a substitute. By converting surplus electricity that would otherwise be exported or curtailed, the hydrogen subsystem increases system flexibility and improves renewable energy utilization. Fuel cell operation further enables the redistribution of stored hydrogen to periods of elevated demand, supporting peak-load management and enhancing operational flexibility at the building scale.

The observed reduction in peak demand demonstrates the capability of the hydrogen subsystem to balance short-term demand variations and enhance supply reliability in building-scale applications. By enabling long-duration energy buffering and seasonal autonomy, hydrogen storage complements battery systems, particularly under high-demand conditions. Although associated investment costs exceed those of battery storage alone, hydrogen integration substantially increases operational flexibility and system resilience. In residential systems, hydrogen utilization remains limited but can still function as a supplementary storage option when surplus renewable electricity is available.

From an economic perspective, the PV–battery configuration exhibits more favorable performance than a standalone PV system, whereas the inclusion of hydrogen substantially increases total investment costs, primarily due to the hydrogen storage subsystem. Although hydrogen integration extends the payback period, it enhances system flexibility and resilience, highlighting a clear trade-off between economic efficiency and operational robustness. Differences between building- and household-scale systems are largely driven by load characteristics, as commercial and public buildings exhibit continuous daytime demand that aligns well with photovoltaic generation. Consequently, storage systems in such environments operate more intensively but require significantly higher initial investment to achieve proportional benefits.

Across both consumer types, energy storage integration reveals a consistent trade-off between capital expenditure and operational performance. While battery and hydrogen subsystems increase investment costs, they simultaneously reduce grid dependency and improve utilization of locally generated renewable energy, making this balance particularly sensitive to electricity prices, tariff structures and market conditions. The relative benefit of battery storage is more pronounced in residential systems due to the larger proportional reduction in grid electricity purchases, whereas institutional buildings already achieve high direct utilization of photovoltaic generation.

Component lifetime assumptions further influence economic performance. Battery storage typically requires replacement after 10–12 years, power electronics and inverters after 12–15 years, while electrolyzers and fuel cells are generally assumed to operate for 15–20 years. Consequently, gains in energy independence must be balanced against higher upfront and replacement costs. The ratio between battery capacity and hydrogen production influences electricity costs, as batteries primarily reduce short-term grid purchases and lower operating costs, whereas hydrogen systems mainly provide long-term flexibility and peak-load mitigation but currently increase the overall cost of electricity due to lower round-trip efficiency and higher capital investment.

Although hydrogen-based storage exhibits lower round-trip efficiency than batteries, it provides long-duration storage and peak-load mitigation that batteries alone cannot deliver, positioning hydrogen as a complementary technology focused on long-term system flexibility rather than short-term economic optimization under current cost structures.

The substantially higher specific investment cost of hydrogen-based storage is driven by the combined capital expenditure for electrolyzers, high-pressure storage tanks and fuel cells. While hydrogen integration enhances operational flexibility and enables effective peak-load reduction, its current cost structure limits economic competitiveness relative to battery-based storage solutions. These findings are consistent with previous studies: Urs et al. [19] report comparable cost-related limitations for building-scale hydrogen storage, while Bocklisch [32] emphasizes the strategic role of hybrid battery–hydrogen systems under increasing shares of renewable energy sources. In this context, the results indicate that PV–battery systems represent the most economically favorable short-term option, whereas PV–battery–hydrogen configurations primarily enhance long-term system resilience and sustainability, particularly in applications requiring seasonal storage and advanced peak-load management.

Beyond techno-economic performance, long-term sustainability is determined by environmental impact and the robustness of digital integration. The coupling of photovoltaic generation with battery and hydrogen storage reduces emissions by decreasing grid dependence and improving renewable electricity utilization, while blockchain technology provides a digital governance layer that enhances transparency, security and traceability in decentralized energy markets. Greenhouse gas emission reduction remains a key sustainability indicator, with photovoltaic generation acting as the primary driver and battery storage further amplifying this effect through increased self-consumption.

Differences in emission reduction between consumer types are primarily driven by load profiles and self-consumption levels. In institutional buildings, continuous daytime demand already aligns well with photovoltaic generation, limiting the incremental emission benefit of battery storage. In contrast, residential systems benefit more strongly from battery integration due to larger proportional reductions in grid electricity imports. The reported emission results represent operational-phase emissions only; as the external electricity generation mix becomes less carbon-intensive, absolute emission levels will decrease across all configurations, while relative emission reductions from local renewable generation are expected to remain positive.

These emission-reduction trends are consistent with recent literature, which identifies PV–battery systems as effective short-term solutions for reducing operational emissions, while PV–battery–hydrogen configurations are recognized as long-term enhancements that improve system flexibility and resilience [19,29]. The results further confirm that hybrid PV systems deliver measurable environmental benefits, with particularly strong effects in the residential sector due to higher relative reductions in purchased grid electricity. Consistent with life cycle–based sustainability assessments, environmental performance is strongly influenced by the electricity generation mix and operational characteristics of end-use systems, as demonstrated in studies of battery-electric vehicles under varying renewable energy scenarios [64].

Finally, the blockchain implementation functions as a digital layer enabling decentralized peer-to-peer electricity trading without introducing additional energetic or economic performance indicators. Smart contracts automate transaction execution, while an oracle-based approach enables reliable integration of external data sources. The developed decentralized application confirms the technical feasibility of integrating a blockchain-based trading layer with hybrid PV–battery–hydrogen systems. Although no real-market deployment was considered, the validated functionality aligns with recent studies on blockchain-enabled peer-to-peer energy markets emphasizing automated settlement, flexible scheduling and integration of renewable energy and green hydrogen supply chains [65]. The proposed mechanism is designed as a local market layer complementary to existing regional electricity markets, with physical power dispatch and network constraints remaining under the authority of the distribution system operator.

5. Conclusions

This study quantitatively evaluated hybrid photovoltaic (PV) energy systems integrating battery storage, hydrogen technologies and blockchain-based peer-to-peer electricity trading for two representative consumers: a scientific–educational institution and a residential household.

PV–battery systems achieve substantial reductions in grid electricity consumption and operational CO2 emissions. Grid demand decreases by approximately 45–50% for the residential household and 35–40% for the institutional building, corresponding to CO2 emission reductions of up to 70% and 38%, respectively. Battery storage provides the most cost-effective short-term flexibility under current market conditions. The institutional PV–battery system reaches a payback period of approximately 3–4 years, while the residential system achieves a payback period of 21–22 years, which was reduced to 7–8 years when co-financing or subsidies are applied.

Hydrogen integration further enhances system flexibility by enabling long-duration storage and peak-load mitigation. In the building-scale system, fuel cell operation reduces peak demand from approximately 210 kWh to 71 kWh (≈66% reduction), supported by a hydrogen storage capacity of about 560 kg H2. However, hydrogen storage exhibits lower round-trip efficiency (25–35%) and higher investment costs than battery storage (85–95% efficiency), limiting its current economic competitiveness and positioning it as a complementary, long-term resilience option.

Operational emission reductions are primarily driven by photovoltaic generation and amplified by battery-supported self-consumption. Although the analysis focuses on operational emissions, relative benefits of local renewable generation remain positive under prospective grid decarbonization scenarios.

This study also confirms the technical feasibility of blockchain-based peer-to-peer electricity trading. Validated smart contracts and a decentralized application enable bid submission, matching, settlement and energy tokenization in a local test environment, demonstrating decentralized trading compatible with existing grid regulation and distribution system operator control.

Overall, PV–battery systems provide the most favorable near-term balance between cost, emission reduction and performance, while PV–battery–hydrogen configurations deliver strategic long-term value through peak-load reduction and seasonal flexibility. Blockchain-based trading strengthens this architecture by enabling transparent and automated energy exchange, supporting future pilot deployments and system optimization.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B. and M.S.; methodology, A.B., M.H. and M.S.; software, A.B. and K.Ć.; validation, A.B. and K.Ć.; formal analysis, A.B.; investigation, K.Ć.; resources, K.Ć.; data curation, K.Ć.; writing—original draft, M.H. and K.Ć.; writing—review & editing, A.B., M.H. and M.S.; visualization, A.B. and K.Ć.; supervision, M.S.; project administration, M.H. and M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research paper was funded by the University of Slavonski Brod through the institutional research project advanced modeling and optimization of compact heat exchangers for integration into renewable energy systems (MOKIT), which was financed by the European Union—NextGenerationEU. The views and opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the European Union or the European Commission. Neither the European Union nor the European Commission can be held responsible for them.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author K.Ć. was employed by the company BIM-ING d.o.o. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CCHP | combined cooling, heating and power |

| CFCs | Chlorofluorocarbons |

| CHP | combined heat and power |

| DApp | decentralized web application |

| DoD | depth of discharge |

| HEMS | Home Energy Management System |

| ID | Identification |

| IEA | International Energy Agency |

| IRENA | International Renewable Energy Agency |

| NECPs | National Energy and Climate Plans |

| NOCT | nominal operating cell temperature |

| NRGcoin | Energy-based cryptocurrency for renewable energy trading |

| P2P | peer to peer |

| PAFC | Phosphoric Acid Fuel Cell |

| PEM | Proton Exchange Membrane electrolyzer |

| PV | photovoltaic |

| PVGIS | Photovoltaic Geographical Information System |

| SCADA | Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition |

| SOC | state of charge |

| STC | standard test conditions |

| VPP | virtual power plant |

References

- International Energy Agency (IEA). World Energy Outlook 2022; IEA: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mathiesen, B.V.; Lund, H.; Connolly, D.; Wanzel, H.; Østergaard, P.A.; Möller, B.; Nielsen, S.; Ridjan, I.; Karnøe, P.; Sperling, K.; et al. Smart Energy Systems for Coherent 100% Renewable Energy and Transport Solutions. Appl. Energy 2015, 145, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. The European Green Deal; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- Stojkov, M.; Hnatko, E.; Kljajin, M.; Zivic, M.; Hornung, K. CHP and CCHP Systems Today. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. Syst. 2011, 2, 75–79. [Google Scholar]

- International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). Renewable Capacity Statistics; IRENA: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Masson, G.; Kaizuka, I. Trends in PV Applications 2022; IEA PVPS: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.; Ning, B.; Hu, X.; Cai, B. Self-Adaptive Teaching-Learning-Based Optimization with Reusing Successful Learning Experience for Parameter Extraction in Photovoltaic Models. Teh. Vjesn.-Tech. Gaz. 2025, 32, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaier, A.A.; Elymany, M.M.; Enany, M.A.; Elsonbaty, N.A. Multi-Objective Optimization and Algorithmic Evaluation for EMS in a HRES Integrating PV, Wind, and Backup Storage. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, R.; Adhikari, N. A Comprehensive Review on the Role of Hydrogen in Renewable Energy Systems. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 82, 923–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barac, A.; Živić, M.; Virag, Z.; Vujanović, M. Thermo-Economic Multi-Objective Optimisation of a Solar Cooling System. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 202, 114656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bošnjaković, M.; Stojkov, M.; Katinić, M.; Lacković, I. Effects of Extreme Weather Conditions on PV Systems. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, H.; Østergaard, P.A.; Connolly, D.; Mathiesen, B.V. Smart Energy and Smart Energy Systems. Energy 2017, 137, 556–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouaziz, L.; Dhaoui, M.; Ben Hamed, M.; Flah, A.; Kraiem, H.; Almalki, M.M.; Mousa, A.A. Study of the Effects of Wind Turbines Integration Into the Electricity Grid. Teh. Vjesn.-Tech. Gaz. 2025, 32, 1705–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SolarPower Europe. EU Market Outlook for Solar Power 2022–2026; SolarPower Europe: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- SolarPower Europe. EU Solar Strategy 2030: Delivering the European Green Deal; SolarPower Europe: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Blinn, A.; Bunner, J.; Kennel, F. A Two-Layer HiMPC Planning Framework for High-Renewable Grids: Zero-Exchange Test on Germany 2045. Energies 2025, 18, 5579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongerden, M.R.; Haverkort, B.R. Battery Modeling; University of Twente: Enschede, The Netherlands, 2008; Volume 14. [Google Scholar]

- Živić, M.; Galović, A.; Avsec, J.; Barac, A. Application of Gas Condensing Boilers in Domestic Heating. Teh. Vjesn. 2019, 26, 681–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urs, R.R.; Chadly, A.; Al Sumaiti, A.; Mayyas, A. Techno-Economic Analysis of Green Hydrogen as an Energy-Storage Medium for Commercial Buildings. Clean Energy 2023, 7, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avsec, J.; Novosel, U.; Strušnik, D. Hydrogen Production Using a Thermochemical Cycle. J. Energy Technol. 2022, 15, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novosel, U.; Živić, M.; Avsec, J. The Production of Electricity, Heat and Hydrogen with the Thermal Power Plant in Combination with Alternative Technologies. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 10072–10081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Republika Hrvatska. Ministarstvo Zaštite Okoliša i Energetike Konačni Prijedlog Zakona o Potvrđivanju Izmjene Montrealskog Protokola o Tvarima, a Koje Oštećuju Ozonski Omotač; Republic of Croatia: Zagreb, Croatia, 2018.

- Republika Hrvatska. Ministarstvo Zaštite Okoliša i Energetike Sedmo Nacionalno Izvješće i Treće Dvogodišnje Izvješće Republike Hrvatske Prema Okvirnoj Konvenciji Ujedinjenih Naroda o Promjeni Klime (UNFCCC); Republic of Croatia: Zagreb, Croatia, 2018; Volume 312.

- Republic of Croatia, Ministry of Economy and Sustainable Development. Croatian Greenhouse Gas Inventory for the Period 1990–2022; Republic of Croatia: Zagreb, Croatia, 2024.

- International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). Global Hydrogen Trade to Meet the 1.5 °C Climate Goal: Green Hydrogen Supply; IRENA: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zubairu, N.; Al Jabri, L.; Rejeb, A. A Review of Hydrogen Energy in Renewable Energy Supply Chain Finance. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Luo, X. Exploration of the Diversified Path of Energy Economic Transformation Based on the Perspective of Hydrogen Energy Industry Innovation. Teh. Vjesn.-Tech. Gaz. 2024, 31, 1179–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hzang, M. Hydrogen Integration in Power Systems: A Sociotechnical Perspective on Digital Supply Chain Optimisation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 170, 151085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staffell, I.; Scamman, D.; Velazquez Abad, A.; Balcombe, P.; Dodds, P.E.; Ekins, P.; Shah, N.; Ward, K.R. The Role of Hydrogen and Fuel Cells in the Global Energy System. Energy Environ. Sci. 2019, 12, 463–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregorovičová, E.; Pospíšil, J. Hydrogen Safety in Energy Infrastructure: A Review. Energies 2025, 18, 5470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giedraityte, A.; Rimkevicius, S.; Marciukaitis, M.; Radziukynas, V.; Bakas, R. Hybrid Renewable Energy Systems—A Review of Optimization Approaches and Future Challenges. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocklisch, T. Hybrid Energy Storage Systems for Renewable Energy Applications. Energy Procedia 2015, 73, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnin, A.S.; Wacławiak, K.; Humayun, M.; Zhang, S.; Ullah, H. Hydrogen Storage Technology, and Its Challenges: A Review. Catalysts 2025, 15, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, H.; Qayyum, F.; Iqbal, N.; Khan, M.A.; Naqvi, S.S.A.; Khan, S.; Kim, D.H. Secure Hydrogen Production Analysis and Prediction Based on Blockchain Service Framework for Intelligent Power Management System. Smart Cities 2023, 6, 3192–3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulraiz, A.; Al Bastaki, A.J.; Magamal, K.; Subhi, M.; Hammad, A.; Allanjawi, A.; Zaidi, S.H.; Khalid, H.M.; Ismail, A.; Hussain, G.A.; et al. Energy Advancements and Integration Strategies in Hydrogen and Battery Storage for Renewable Energy Systems. iScience 2025, 28, 111945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tezer, T. Multi-Objective Optimization of Hybrid Renewable Energy Systems with Green Hydrogen Integration and Hybrid Storage Strategies. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 142, 1249–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andoni, M.; Robu, V.; Flynn, D.; Abram, S.; Geach, D.; Jenkins, D.; McCallum, P.; Peacock, A. Blockchain Technology in the Energy Sector: A Systematic Review of Challenges and Opportunities. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 100, 143–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojo, K.E.; Saha, A.K.; Srivastava, V.M. Review of Advances in Renewable Energy-Based Microgrid Systems: Control Strategies, Emerging Trends, and Future Possibilities. Energies 2025, 18, 3704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, G.; Raute, R.; Caruana, C. The Brain Behind the Grid: A Comprehensive Review on Advanced Control Strategies for Smart Energy Management Systems. Energies 2025, 18, 3963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepaniuk, E.K.; Szczepaniuk, H. Cybersecurity of Smart Grids: Requirements, Threats, and Countermeasures. Energies 2025, 18, 5017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holik, M.; Barac, A.; Zidar, J.; Stojkov, M. Dual-Approach Calibration Unlocks Potential of Low-Power, Low-Cost Temperature and Humidity Sensors. Teh. Vjesn.-Tech. Gaz. 2024, 31, 1335–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šarić, T.; Tedeško, E.; Šimunović, G.; Havrlišan, S. Smart Mini Greenhouse for Eco-Friendly Agriculture. Teh. Glas. 2025, 19, 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihaylov, M.; Jurado, S.; Avellana, N.; Van Moffaert, K.; Magrans, I.; Nowe, A. NRGcoin: Virtual Currency for Trading Renewable Energy. In Proceedings of the 2014 11th International Conference on the European Energy Market (EEM), Krakow, Poland, 28–30 May 2014; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Tanis, Z.; Durusu, A.; Altintas, N. A Comprehensive Review on Peer-to-Peer Energy Trading: Market Structure, Operational Layers, Energy Cooperatives and Multi-Energy Systems. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2025, 19, e70075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiruvenkatasamy, S.; Sivaraj, R.; Vijayakumar, M. Blockchain Assisted Fireworks Optimization with Machine Learning Based Intrusion Detection System (IDS). Teh. Vjesn.-Tech. Gaz. 2024, 31, 596–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Jiao, S.; Xie, Y.; Xia, S.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Li, M. Two-Way Dynamic Pricing Mechanism of Hydrogen Filling Stations in Electric-Hydrogen Coupling System Enhanced by Blockchain. Energy 2022, 239, 122194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zhang, M. Blockchain-Based Energy Trading in Renewable-Based Community Based Self-Sufficient Utility: Analysis of Technical, Economic, and Regulatory Aspects. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2024, 64, 103679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengelkamp, E.; Gärttner, J.; Rock, K.; Kessler, S.; Orsini, L.; Weinhardt, C. Designing Microgrid Energy Markets. Appl. Energy 2018, 210, 870–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pylon Network. White Paper on Energy Data Transparency; Pylon City: Bilbao, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Lu, C.; Ma, X.; Sun, J. Blockchain Application and Cooperative Innovation in China’s Hydrogen Industry Alliance: From the Perspective of Knowledge Spillover. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Energy Internet (ICEI), Zhuhai, China, 1–3 November 2024; pp. 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristijan, Ć. Decentralized Hydrogen Production with Innovative Blockchain Technology Using Solar Energy. In Proceedings of the 12th International Scientific-Professional Conference SBW 2023, Opatija, Croatia, 10–12 May 2023; p. 36. [Google Scholar]

- Paraga, Y.; Sovacool, B.K. Electricity Market Design for the Prosumer Era. Nat. Energy 2016, 1, 16032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedi, A.; Ramprabhakar, J.; Anand, R.; Meena, V.P.; Hameed, I.A. Empowering Net Zero Energy Grids: A Comprehensive Review of Virtual Power Plants, Challenges, Applications, and Blockchain Integration. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huld, T.; Müller, R.W.; Gambardella, A. A New Solar Radiation Database for Estimating PV Performance in Europe and Africa. Sol. Energy 2012, 86, 1803–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PVGIS Team—Europen Commission Photovoltaic Geographical Information System. Available online: https://joint-research-centre.ec.europa.eu/pvgis-photovoltaic-geographical-information-system_en (accessed on 8 February 2022).

- Aurora Inc. HelioScope, Version 2025; Aurora Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2025.

- UL. Solution Hybrid Optimization of Multiple Energy Resources (HOMER), Version 3.16.2; UL Solutions: Northbrook, IL, USA, 2025.

- ConsenSys Software Inc. Ethereum Environment (Ganache), Version 7.7.1; ConsenSys Software Inc.: Fort Worth, TX, USA, 2022.

- ConsenSys Software Inc. MetaMask, Version 13.11.2; ConsenSys Software Inc.: Fort Worth, TX, USA, 2024.

- Pylontech New Residential Solutions Pylontech Force-H1-48/336V. Available online: https://www.solartopstore.com/collections/pylontech/products/pylontech-force-h1-48-336v (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Pop, C.; Cioara, T.; Antal, M.; Anghel, I.; Salomie, I.; Bertoncini, M. Blockchain Based Decentralized Management of Demand Response Programs in Smart Energy Grids. Sensors 2018, 18, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HEP ELEKTRA doo. HEP Tarif Models. Available online: https://www.hep.hr/elektra/kucanstvo/tarifni-modeli/1577 (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Jain, P. Oracle Problem in Blockchain. Available online: https://medium.com/@pranjalll/oracle-problem-in-blockchain-0a8c4654d11b (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Božič, J.T.; Čikić, A.; Muhič, S.; Kraševec, B. Application of Life Cycle Assessment to Determine the Influence of Electricity Mix Profile and Driving Mode on the Environmental Impact of Electric Battery Vehicles. Teh. Glas. 2025, 19, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhavana, G.B.; Anand, R.; Ramprabhakar, J.; Meena, V.P.; Jadoun, V.K.; Benedetto, F. Applications of Blockchain Technology in Peer-to-Peer Energy Markets and Green Hydrogen Supply Chains: A Topical Review. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 21954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.