Abstract

To improve the low-carbon economic operation of integrated energy system (IES) with electric–thermal–hydrogen hybrid energy storage (ETH-HES), this paper proposes a low-carbon optimal dispatch strategy that jointly considers the bidirectional interaction between green certificate trading (GCT) and stepwise carbon emission trading (SCET), as well as lifetime degradation of electrolyzers and batteries. A coupled GCT–SCET interaction model is formulated by linking green certificate acquisition with carbon quota transactions, and a triple-incentive mechanism is introduced to monetize the low-carbon value of ETH-HES. In addition, degradation-aware models are established for the electrolyzer and battery to capture long-term operating costs. Case studies show that the proposed strategy reduces system operating cost and carbon emissions, increases wind and PV utilization, and improves the operating profit of ETH-HES.

1. Introduction

Driven by the global energy transition and carbon neutrality goals, the large-scale development of renewable energy has become a key pathway for transforming modern energy systems. By the end of 2024, China’s installed wind and photovoltaic capacities had reached 520 GW and 890 GW, respectively, representing year-on-year increases of 18.0% and 45.2%. New installations have exceeded 100 GW for four consecutive years. However, as the share of fluctuating power sources continues to rise, IES face increasingly severe challenges in terms of renewable energy integration. In 2024, China’s total curtailed wind and solar generation reached 34.7 billion kWh—equivalent to the annual electricity consumption of a medium-sized city—mainly due to the insufficient flexibility of the existing energy system.

ETH-HES technology offers a promising approach to addressing these energy absorption challenges. This technology enables complementary energy storage across multiple time scales through the synergistic integration of various storage forms: second-level electrical storage, minute-level thermal storage, and day-level hydrogen storage. Spatially, it constructs a multi-energy-flow network that supports efficient electrical transmission, regional thermal distribution, and cross-seasonal hydrogen storage. From an economic perspective, ETH-HES can generate diversified revenues through peak–valley arbitrage in energy markets and multi-purpose value in hydrogen markets. Nevertheless, its large-scale deployment still encounters three major bottlenecks: first, high initial investment costs, with key equipment typically costing 3–5 times more than traditional storage systems; second, significant operational optimization complexity, as multi-energy-flow coupling leads to an exponential increase in decision variables; and third, imperfect market mechanisms, where existing policies fail to fully reflect the low-carbon value of energy storage. In response to these issues, many scholars have carried out extensive research.

Regarding technical optimization, Ref. [1] proposes a multi-time-scale optimal scheduling method for IES with ETH-HES under wind and solar uncertainties, while Ref. [2] develops a robust configuration planning framework for net zero-energy buildings considering source-load dual uncertainty and hybrid energy storage. Ref. [3] establishes a high-fidelity electrothermal model for battery systems to support accurate electro-thermal coupling analysis, and Ref. [4] improves wind power integration through the coordinated operation of regenerative electric boilers and battery energy storage. Ref. [5] presents an optimal multi-timescale economic dispatch model for microgrids with hybrid electric-hydrogen-thermal storage, and Ref. [6] studies energy management and capacity optimization for CCHP systems integrated with electric–thermal hybrid storage. Ref. [7] investigates coordinated dispatch strategies for electric, thermal, and hydrogen vectors in renewable-enriched microgrids under uncertainty, whereas Ref. [8] proposes a risk-aware day-ahead planning model for zero-energy hubs integrating power-to-hydrogen technology and demand-side elasticity. Ref. [9] performs stochastic techno-economic optimization for hybrid energy systems with multiple renewable resources and electric/thermal storage, and Ref. [10] considers optimal dispatch of multi-carrier energy systems that include energy storage and electric vehicles. Ref. [11] develops a scheduling strategy for electricity–heat–gas hybrid energy storage microgrids with novel combined heat and power units, while Ref. [12] evaluates the economic and technical feasibility of optimally configuring and operating hybrid CSP/PV/wind cogeneration systems with energy storage. In the building and residential sectors, Ref. [13] models and optimizes rooftop photovoltaic systems coupled with electric–hydrogen–thermal hybrid storage for zero-energy buildings, and Ref. [14] proposes a scenario-based operation and scheduling strategy for residential energy hubs including plug-in hybrid electric vehicles and heat storage under multiple uncertainties. Overall, these studies significantly advance the modeling, configuration, and scheduling of hybrid energy storage systems, but they mainly focus on improving local techno-economic performance. Systematic multi-level incentive mechanisms are still lacking, which restricts the full utilization of hybrid energy storage in wind and solar power integration and peak shaving/valley filling.

Regarding market mechanisms and system-level operation, Ref. [15] optimizes a solar-driven community integrated energy system based on a dynamic hybrid hydrogen–electric energy storage strategy, and Ref. [16] analyzes the optimization and performance of integrated energy systems considering hybrid electro-thermal energy storage. Ref. [17] proposes a dynamic-programming-based economic day-ahead scheduling method for tri-generation integrated energy systems with hybrid energy storage, whereas Ref. [18] develops a two-stage optimal scheduling strategy for hybrid energy systems participating in the day-ahead electricity market. Ref. [19] designs a sustainable energy system by combining molten-salt-based hybrid thermal energy storage with electrochemical energy conversion, and Ref. [20] formulates a multi-objective operation optimization model for integrated energy systems considering ground source and solar energy. Ref. [21] presents an optimal dispatch model for integrated energy microgrids with hybrid structured electric–thermal energy storage, while Ref. [22] proposes an electro-thermal hybrid energy storage model aimed at enhancing the autonomous control capability of multi-energy microgrids. Ref. [23] develops an energy management system for small-scale hybrid wind–solar–battery microgrids. At the distribution network level, Ref. [24] investigates optimal stochastic scheduling of reconfigurable active distribution networks hosting hybrid renewable energy systems, and Ref. [25] proposes a stochastic power management strategy for day-ahead scheduling of wind–hydrogen energy storage systems considering wind power and market price uncertainties. Ref. [26] studies the optimization of wind–solar hybrid systems from the perspective of multi-timescale energy stability and renewable uncertainty, and Ref. [27] explores optimal capacity configuration of wind–photovoltaic–storage hybrid systems based on multi-objective optimization. Ref. [28] further develops a model-based multi-objective capacity optimization method for wind power systems coupled with hybrid energy storage. However, the above studies generally do not explicitly integrate carbon trading and GCT mechanisms or quantify the associated revenues, and thus fail to fully reveal the potential value of hybrid energy storage systems in promoting low-carbon economic development in integrated energy systems. Ref. [29] established an economic optimization operation model for integrated energy systems that balances wind power integration and flexible load regulation, enabling improved system operational economics while enhancing wind power utilization rates. Regarding uncertainty optimization and game-based scheduling in multi-integrated energy systems, Ref. [30] proposes a two-layer hybrid game framework for multi-integrated energy microgrids. This framework combines stochastic-robust optimization with revenue sharing to enhance the economic efficiency and robustness of multi-microgrid coordinated operation.

As GCT and SCET mechanisms continue to mature, existing research has largely been limited to their simple aggregation, without exploring the deeper bidirectional interactions between them. In current practice, GCT provides market-based incentives for renewable energy generation through tradable certificates linked to green electricity output, while SCET regulates carbon emissions through tiered carbon quotas and differentiated marginal carbon prices. Although both mechanisms aim to promote decarbonization, their interaction—where GCT affects the effective carbon intensity of electricity consumption and SCET influences the marginal value of green certificates—has not been fully examined. Moreover, the potential value of energy storage systems in supporting a low-carbon economy under the joint influence of GCT and SCET remains under-explored.

To bridge this research gap, this paper proposes an IES low-carbon optimal scheduling strategy that explicitly incorporates the bidirectional interaction between GCT and SCET, as well as the lifetime degradation of electrolyzers and batteries. First, a coupled GCT–SCET interaction model is developed, in which the issuance, trading, and consumption of green certificates dynamically adjust the effective carbon emission factors of electricity, while the tiered carbon trading mechanism feeds back into the marginal valuation of certificates. This framework enables a more accurate quantification of the low-carbon economic value of the ETH-HES system. Second, a lifetime degradation model for electrolyzers and batteries is formulated to capture efficiency decay and capacity fade under long-term cycling, thereby improving cost assessment accuracy. Finally, a triple compensation strategy based on electricity price incentives, green certificate trading revenue, and carbon trading revenue is proposed to effectively stimulate hybrid energy storage participation in renewable energy accommodation and peak–valley regulation.

2. IES Structure and Trading Mechanism

2.1. IES Structure

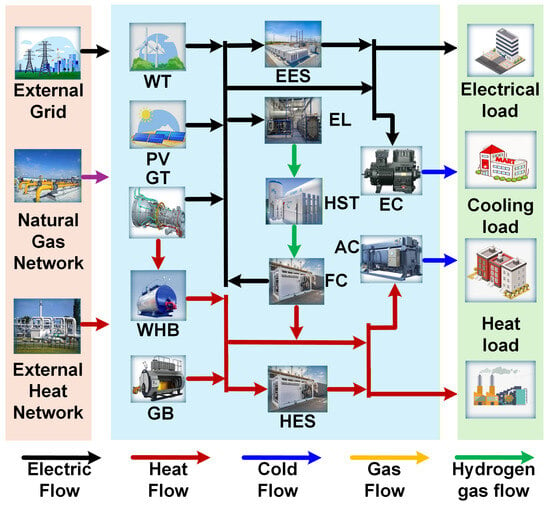

Figure 1 illustrates the overall structure of the IES. The IES integrates multiple forms of energy, including electricity, heat, cooling, and natural gas, and facilitates energy conversion and utilization through various equipment and technologies.

Figure 1.

Structure of the IES.

The external grid supplies electrical power to the system, and surplus electricity can be exported back to the grid. The natural gas network provides fuel for gas turbines (GT) and gas boilers (GB). Electricity generated by wind turbines (WT) and photovoltaic (PV) systems can be used directly to serve electrical loads. Electrical energy storage (EES) absorbs surplus WT and PV power and releases it when required. Electrolyzers (EL) use excess electricity to produce hydrogen, which is stored in hydrogen storage tanks (HST). Fuel cells (FC) then convert the stored hydrogen into electricity and heat for the system. GT units consume natural gas to generate electricity, and their high-temperature exhaust is recovered by a waste heat boiler (WHB), providing additional thermal energy and improving overall efficiency. Heat energy storage (HES) contributes to dynamic thermal balancing. Absorption chillers (AC) use thermal energy for cooling, whereas electric chillers (EC) use electrical energy for cooling to satisfy the cooling load.

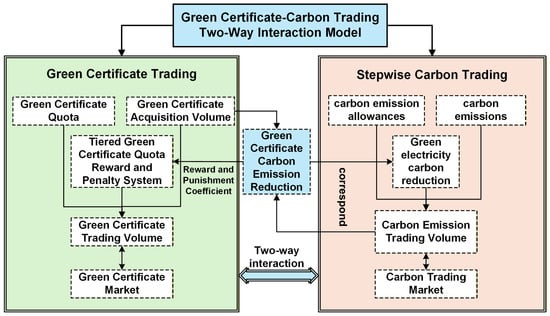

2.2. GCT and SCET Bidirectional Interaction Mechanism

Compared with traditional thermal power generation, renewable energy offers significant advantages in reducing carbon emissions. To maximize the low-carbon benefits of green certificates, establish a bidirectional interaction mechanism between GCT and SCET. Figure 2 illustrates the operational principles of this mechanism. It is designed to further promote the development of a low-carbon economy through optimized energy structures and market incentives. First, wind and solar power generation is converted into green certificate quantities and the corresponding equivalent emission reductions. Second, these equivalent emission reductions, represented by green certificates, are used to adjust the system’s effective carbon emission requirements, thereby offsetting part of the emission allowances. Finally, the remaining net emissions are allocated to different price brackets within the tiered carbon trading mechanism to calculate the final SCET cost.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the bidirectional interaction mechanism between GCT and cascaded SCET.

First, the carbon emissions reduction represented by each green certificate was quantified. The calculation formula is as follows:

where represents the carbon reduction amount per unit of green certificate; and , respectively, denote the carbon emission equivalents of coal-fired power generation and renewable energy generation (as represented by green certificates) throughout their respective energy chain lifecycles. For specific calculation methods, refer to the relevant literature [16].

The carbon emission trading volume following the two-way interaction between GCT and SCET is calculated using the following formula:

where represents carbon emissions; represents carbon emission allowances; , , , , respectively, denote GT, WHB, and GB output and electricity purchased from the grid at time t; represents carbon emission allowances per unit of heat supplied; represents actual carbon emissions per unit of heat supplied; represents carbon emission allowances per unit of electricity supplied by the grid; represents actual carbon emissions per unit of electricity supplied by the grid; is the conversion factor for power generation to heating capacity; is the carbon emission trading volume after exchange; is the green electricity carbon reduction volume corresponding to the acquired green certificates; represents the number of green certificates obtained from wind and solar power generation; denotes the conversion factor for wind and solar power generation to green certificates, where 1 MW·h of wind power generation equals one green certificate; T is the dispatch cycle, defined as 24 h; and and , respectively, denote wind power output and solar power output at time t.

Based on the carbon emission reductions corresponding to green certificates, carbon emission trading volumes can be reverse-calculated. Combined with incentive-penalty coefficients, this ultimately generates a tiered green certificate quota incentive-penalty volume .

where d represents the interval length for carbon emission trading volume; and , , and denote the reward and penalty coefficients for green certificate trading.

The formula for calculating SCET cost considering the bidirectional interaction mechanism between GCT and SCET, is

where represents the base price for SCET transactions; x and y denote the compensation coefficient and penalty coefficient for SCET, respectively; and d represents the length of the carbon trading volume interval.

The GCT cost calculation formula after bidirectional interaction is

where represents the demand for green certificate quotas; denotes the green certificate quota coefficient; indicates the power load at time t; signifies the unit price of green certificates; and represents the GCT cost after bidirectional interaction.

The ETH-HES system fundamentally achieves the spatiotemporal transfer of green electricity by storing and releasing renewable energy. From a full life-cycle carbon emissions perspective, each unit of electricity stored and released by this system possesses the same low-carbon attributes as the original renewable energy source. When the energy storage system charges during periods of renewable energy surplus and discharges during peak electricity consumption periods, each unit of electricity output simultaneously generates green certificate revenue and carbon reduction benefits. This creates a complete value chain encompassing “green certificate certification—carbon reduction accounting—market revenue realization.” Assuming EES discharges replace part of coal-fired power generation, FC generation replaces part of GT generation, and FC heating replaces part of GB heating capacity, the hybrid energy storage carbon trading compensation is calculated as follows:

where represents the number of green certificates obtained from EES discharge and FC generation; denotes the quantification coefficient converting EES discharge and FC generation into green certificates; and represent the EES discharge and FC generation during time period t, respectively; and represents the carbon credits obtained from hybrid energy storage.

3. IES Low-Carbon Economy Dispatch Model

3.1. Lifetime Decay Model for EL

Under constant conditions such as temperature and pressure, a significant correlation exists between EL voltage variations and power fluctuations. The lifetime degradation model, quantified by the decay in EL efficiency, is expressed as

where , , and denote the efficiency decay values of EL during steady-state operation, fluctuating operation, and start-stop conditions, respectively. , , and correspond to the efficiency decay coefficients for these three operating conditions, with values of , , and , respectively. is a 0–1 variable representing the switching state of EL; and denote the EL operating power during time periods t and t − 1, respectively; is the rated power of the EL; and represent the maximum number of start-ups and shutdowns of the EL within a day, respectively; and denote the total efficiency decay and total equivalent lifetime decay of the EL within a scheduling cycle, respectively; is the rated operational lifetime of the EL; and denote the rated efficiency and maximum efficiency of the EL, respectively; is the rated efficiency decay coefficient of the EL, set to ; and represents the unit time interval.

3.2. Lifetime Decay Model for EES

The lifespan of an EES can be assessed by its cumulative effective throughput. When the cumulative effective throughput reaches the EES’s rated lifespan threshold, the EES must be replaced.

where represents the rated throughput of the EES; represents the rated cycle life of the EES; denotes the rated depth of discharge for the EES; represents the rated capacity of the EES at the rated discharge current; indicates the state of charge of the EES during time interval t; signifies the throughput consumed per single use of the EES; , , and are constants derived from EES parameters; and are parameters obtained through simulation testing; and serves as the key metric representing the rated throughput consumed per single discharge cycle.

3.3. Objective Function

With IES low-carbon economic dispatch optimization as the core objective, a multi-objective optimization model was constructed to achieve synergistic optimization of minimizing the system’s comprehensive operating costs, maximizing ETH-HES operational revenues, and minimizing carbon emissions. The IES comprehensive operating costs encompass green certificate transaction fees, tiered carbon trading expenditures, external energy procurement costs, system operation and maintenance expenses, and penalties for curtailed wind and solar power. ETH-HES operational revenue encompasses peak shaving income, reserve capacity income, demand response income, green certificate income, and carbon trading compensation. Primary costs stem from the life-cycle degradation expenses of EL and EES.

The total operating cost of IES is

where represents the IES comprehensive operating cost; , , and represent the external energy procurement cost, system operation and maintenance cost, and wind and solar curtailment penalty cost, respectively.

where and represent the external electricity purchase power and natural gas power during time period t, respectively; and denote the external electricity purchase unit price and natural gas unit price during time period t, respectively; , , , , , , and denote the WT power generation, PV power generation, GT power generation, GB heating, WHB heating, AC cooling, and EC cooling power during time period t, respectively; , , , , , , and denote the unit operation and maintenance cost coefficients for WT power generation, PV power generation, GT power generation, GB heating, WHB heating, AC cooling, and EC cooling during time period t, respectively; and represent the curtailed wind power and curtailed solar power, respectively; and and denote the unit penalty cost coefficients for curtailed wind power and curtailed solar power, respectively.

ETH-HES operating revenue is

where represents ETH-HES operational revenue; , , , and denote ETH-HES’s peak shaving, reserve capacity, green certificate revenue, and carbon trading compensation, respectively; and represent the lifetime degradation costs of EL and EES, respectively; and represents the daily chemical investment cost.

where and represent the grid electricity price during peak hours and the amount of electricity discharged from the EES to the grid, respectively; and represent the grid electricity price during off-peak hours and the amount of electricity discharged from the EES to the grid, respectively; and denotes the reserve capacity of the EES; denotes the price per unit of reserve capacity.

where is defined as the base price for carbon trading, represents the increment of the carbon emission range, and denotes the price increase rate.

where r and m represent the interest rate and system lifespan, respectively; , , , , and denote the configuration capacities of EES, HES, HST, EL, and FC, respectively; and , , , , and denote the corresponding unit capacity prices of EES, HES, HST, EL, and FC, respectively.

3.4. Constraints

GT, GB, WHB, AC, EC, EL, and FC output power must remain within minimum and maximum limits. Additionally, equipment such as GT, GB, EL, and FC must satisfy ramping power constraints. Their general model is as follows:

Energy storage units are critical equipment for IES, enabling the transfer and regulation of energy across time dimensions. Common forms of energy storage include EES, HES, and HST. Their general model can be expressed as

where and represent the maximum charging and discharging power of the energy storage system; and denote the energy storage capacity of the energy storage unit during time periods t and t + 1; , , , and represent the minimum energy storage power, maximum energy storage power, and the initial and final energy storage power of the battery during the daily cycle; , , denote the self-consumption rate of energy storage and the charging/discharging efficiency of the energy storage unit; , represent the charging/discharging power of the energy storage unit during time period t; and is the state indicator for charging or discharging of the energy storage unit, where indicates charging and indicates discharging.

The power purchase constraint is

where represents the upper limit of the purchased power capacity.

The electrical power balance constraint is

where represents the power output of FC during time period t; represents the electrical load during time period t; represents the electrical power consumed by EC during time period t.

The heat power balance constraint is

where represents the heating power of FC during time interval t; and represents the heat load during time interval t; represents the heat power consumed by AC during time interval t.

The cold power balance constraint is

where represents the cooling load during time period t.

The hydrogen mass balance constraint is

where represents the mass of hydrogen produced by EL during time interval t; and and represent the mass of hydrogen charged and discharged by HST during time interval t; represents the mass of hydrogen consumed by FC during time interval t.

3.5. Model Solution

For nonlinear models within the framework, linearization is required to convert them into mixed-integer linear programming models. These models are then solved using the CPLEX solver, with the solution process detailed in Ref. [31].

4. Results

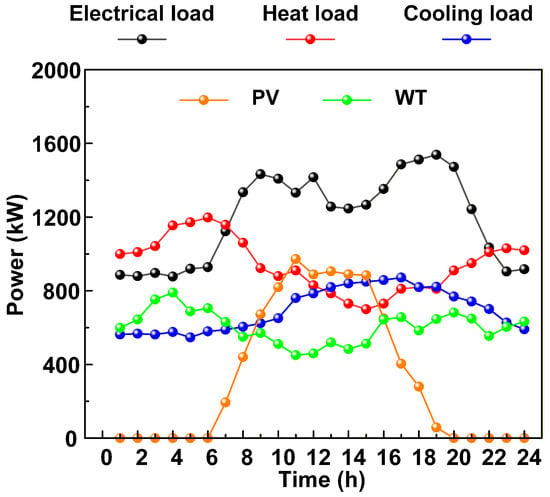

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed optimal scheduling strategy, a case study of an IES in eastern Inner Mongolia, China is conducted. The method in Ref. [32] is employed to handle the uncertainty of WT and PV generation. The processed baseline data curves are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Curve of each basic data.

In the simulation experiment, the scheduling cycle was set to 24 h with a scheduling interval of 1 h, enabling comprehensive validation of the proposed strategy. The unit capacity prices for EES, HES, HST, EL, and FC were 0.2 yuan/kW, 0.15 yuan/kW, 0.25 yuan/kW, 0.15 yuan/kW, and 0.223 yuan/kW, respectively. Detailed parameters for the internal coupled equipment and energy storage devices within the IES are provided in Table 1 and Table 2. Parameters for time-of-use electricity pricing, feed-in tariffs, and SCET are referenced from Ref. [33], while GCT-related parameters are sourced from Ref. [34].

Table 1.

Energy storage operating parameters.

Table 2.

Equipment operating parameters.

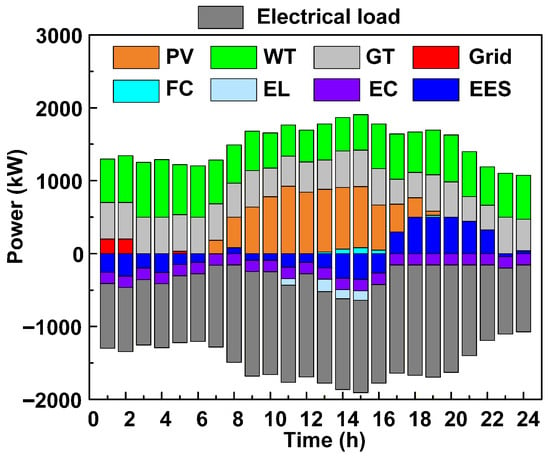

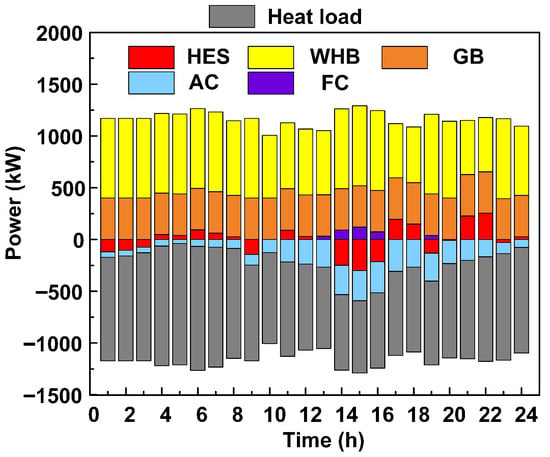

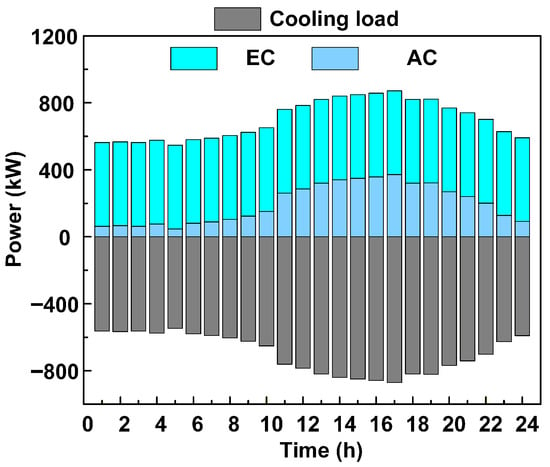

The optimized dispatch results for the balance of electricity, heat, and cooling supply and demand under Scenario 5 are shown in Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6.

Figure 4.

Optimization results of electric energy scheduling.

Figure 5.

Optimization results of heat energy scheduling.

Figure 6.

Optimization results of cooling energy scheduling.

The electricity load is primarily supplied by WT, PV, and GT. During midday hours, EL uses surplus electricity for hydrogen production. EES charges when wind and solar generation is abundant and electricity demand is low. It then discharges between 17:00 and 22:00 to meet peak load requirements. The optimization results indicate that the dynamic charging and discharging of EES smooths fluctuations in electricity supply and demand, reduces dependence on the grid, and provides effective peak shaving and valley filling. At the same time, the system fully integrates wind and solar power resources, reducing fossil fuel consumption and improving environmental performance. From an economic perspective, the scheduling strategy reduces electricity procurement costs during peak hours and increases operational revenue through electricity sales during off-peak periods. As a result, both economic and environmental benefits are improved.

The heat load is primarily supplied by GB and WHB. Waste heat generated by GT is recovered by WHB and delivered to the thermal load, improving energy utilization. During midday hours, EL absorbs surplus electricity for hydrogen production. The generated hydrogen can be supplied to FC for power generation, and the heat released during FC operation can also serve the thermal load. HES plays a key role in thermal energy scheduling. It charges when heat production exceeds demand and discharges when demand exceeds production, enabling dynamic regulation of thermal loads. The optimization results indicate that the dynamic charging and discharging of HES smooths fluctuations in thermal energy supply and demand, reduces reliance on GB, and provides effective peak shaving and valley filling. At the same time, the system integrates waste heat resources from industrial processes, reduces fossil fuel consumption, and improves environmental performance. From an economic perspective, the scheduling strategy lowers gas consumption during peak periods and increases economic returns through thermal energy utilization during off-peak hours. As a result, both economic efficiency and environmental sustainability are improved.

Cooling demand peaks during the daytime, particularly from midday to evening, and remains relatively low at night. EC operates steadily throughout the entire period and satisfies the basic cooling requirements. AC operates during specific daytime intervals to support EC in meeting peak cooling demand. Its output power increases significantly during high-load periods. This coordination fully exploits the complementary characteristics of EC and AC, enhances system flexibility and reliability, and improves energy efficiency. From an economic perspective, the scheduling strategy reduces electricity consumption during peak hours and increases economic benefits through optimized operation in off-peak periods. As a result, an efficient balance is achieved between cooling energy supply and demand and overall cost performance.

5. Discussion

5.1. Comparison Across Different Scenarios and Analysis of Results

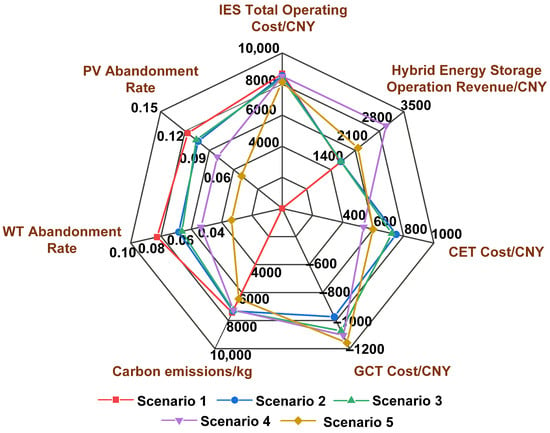

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed strategy, five operational scenarios are defined, as shown in Table 3. The scenarios are compared in terms of the comprehensive operating cost of the IES, hybrid energy storage operating revenue, SCET cost, GCT cost, carbon emissions, wind curtailment rate, and solar curtailment rate. This analysis verifies the feasibility of the proposed model.

Table 3.

Partial optimization results under strategies for Scenarios 1–5.

Scenario 1: GCT, SCET, hybrid energy storage lifetime degradation, and the triple incentive strategy for hybrid energy storage participation in GCT and SCET are not considered.

Scenario 2: SCET and GCT are superimposed. Hybrid energy storage lifetime degradation and the triple incentive strategy for hybrid energy storage participation in GCT and SCET are not considered.

Scenario 3: The bidirectional interaction mechanism between GCT and SCET is considered. Hybrid energy storage lifetime degradation and the triple incentive strategy for hybrid energy storage participation in GCT and SCET are not considered.

Scenario 4: The bidirectional interaction mechanism between GCT and SCET and the triple incentive strategy for hybrid energy storage participation in GCT and SCET are considered, while hybrid energy storage lifetime degradation is not considered.

Scenario 5: GCT, the bidirectional interaction mechanism between GCT and SCET, the triple incentive strategy for hybrid energy storage participation in GCT and SCET, and hybrid energy storage lifetime degradation are all considered.

Table 4 and Table 5 present the optimization results for five operational scenarios. When SCET costs and GCT costs are negative values, they represent corresponding revenue situations. Figure 7 compares the data results across different scenarios.

Table 4.

Partial optimization results under strategies for scenarios 1–5.

Table 5.

Partial optimization results under strategies for scenarios 1–5.

Figure 7.

Comparison of data results under different scenarios.

In Scenario 1, GCT and SCET, hybrid energy storage lifetime degradation, and the triple incentive strategy for hybrid energy storage participation in GCT and SCET are not considered. The system therefore relies on a basic operating mode. The IES comprehensive operating cost is 8668.9609 yuan, indicating relatively high operating expenses in the absence of additional mechanisms. Hybrid energy storage operating revenue is 1677.4184 yuan, which provides some economic benefit; however, without an optimized strategy, the profit potential remains limited. Carbon emissions reach 7434.1663 kg, with wind curtailment and solar curtailment rates of 8.26% and 11.66%, respectively. Environmental performance is moderate, and renewable energy resources are not fully utilized.

In Scenario 2, SCET and GCT are introduced, while hybrid energy storage lifetime degradation and the triple incentive strategy for hybrid energy storage participation in GCT and SCET are still not considered. The IES comprehensive operating cost decreases to 8533.1142 yuan, and hybrid energy storage operating revenue increases to 1694.4344 yuan, representing a slight improvement. SCET incurs a cost of 750.8923 yuan, whereas GCT yields −927.1363 yuan, indicating significant gains from GCT. Carbon emissions decrease to 7314.5944 kg, and wind curtailment and solar curtailment rates fall to 6.82% and 10.39%, respectively, reflecting improved environmental performance. These results show that SCET and GCT contribute to reducing carbon emissions and enhancing renewable energy utilization.

In Scenario 3, the bidirectional interaction mechanism between GCT and SCET is considered, while hybrid energy storage lifetime degradation and the triple incentive strategy for hybrid energy storage participation in GCT and SCET remain excluded. The IES comprehensive operating cost is 8386.3692 yuan, lower than in the previous two scenarios. Hybrid energy storage operating revenue further increases to 1694.6161 yuan. SCET cost is 723.6929 yuan, and GCT cost reaches −1048.8333 yuan, confirming the effectiveness of GCT and the bidirectional interaction between SCET and GCT. Carbon emissions decrease to 7275.6423 kg, with wind curtailment and solar curtailment rates of 6.62% and 10.60%, respectively. Environmental performance continues to improve, demonstrating the positive impact of the bidirectional interaction mechanism.

In Scenario 4, the triple incentive strategy for hybrid energy storage participation in GCT and SCET is considered, while hybrid energy storage lifetime degradation is still ignored. The IES comprehensive operating cost increases slightly to 8502.3643 yuan, but this result remains acceptable given the participation of hybrid energy storage. Hybrid energy storage operating revenue rises markedly to 2985.3922 yuan, indicating substantial economic benefit. SCET cost is 536.4087 yuan, and GCT cost reaches −1086.8119 yuan, further confirming the effectiveness of hybrid energy storage participation. Carbon emissions decrease to 7239.6712 kg, with wind curtailment and solar curtailment rates of 5.36% and 8.00%, respectively, indicating significantly enhanced environmental performance. Hybrid energy storage participation plays an important role in reducing carbon emissions and improving renewable energy utilization.

In Scenario 5, all factors are considered, including the bidirectional interaction between GCT and SCET, the triple incentive strategy for hybrid energy storage participation in GCT and SCET, and hybrid energy storage lifetime degradation. The IES comprehensive operating cost decreases further to 8125.8025 yuan. Hybrid energy storage operating revenue reaches 2182.4317 yuan. Although this value is lower than in Scenario 4, it is more reasonable because hybrid energy storage lifetime degradation is included. SCET cost is 599.3671 yuan, and GCT cost reaches −1150.7395 yuan, further confirming the effectiveness of multi-mechanism coordination. Carbon emissions fall to 6454.7528 kg, with wind curtailment and solar curtailment rates of 3.35% and 5.00%, respectively, achieving the best environmental performance among all scenarios. Overall, the comprehensive optimization strategy performs well in terms of both economic and environmental outcomes.

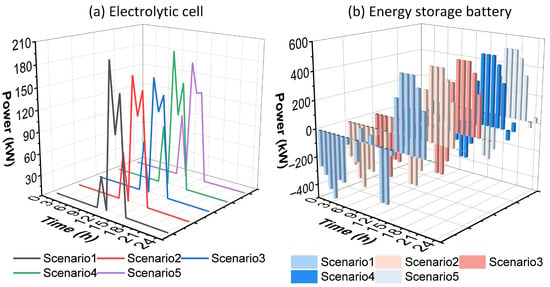

Figure 8a illustrates the power output of the electrolyzer over a 24 h period under different scenarios. Scenario 5 shows the most stable power curve, with small fluctuations and a peak of 165 kW. The power remains close to zero for most hours, with only a short increase between 13:00 and 15:00. In contrast, Scenarios 1–4 exhibit pronounced fluctuations, with clear peaks between 11:00 and 14:00. The maximum power is 192 kW in Scenario 1, 168 kW in Scenario 2, 159 kW in Scenario 3, and 186 kW in Scenario 4. These frequent and high-amplitude fluctuations accelerate electrolyzer lifetime degradation. In Scenario 5, other equipment is scheduled to absorb renewable power fluctuations, which reduces the electrolyzer operating load. This keeps the power output more stable, extends the electrolyzer lifetime, and lowers maintenance costs. In the other scenarios, the electrolyzer is used as the main device to absorb power fluctuations without considering lifetime degradation costs, resulting in much more volatile power curves.

Figure 8.

Comparison of electrolyzer operating power in different scenarios.

Figure 8b illustrates the power of the battery storage system over a 24 h period for different scenarios. Each scenario is shown as a bar chart, where positive values represent charging and negative values represent discharging. Scenario 5 exhibits the smallest power fluctuations, with maximum positive and negative values not exceeding 280 kW. The power remains close to zero for most hours, indicating a stable SOC trajectory. In contrast, Scenarios 1–4 show significant power fluctuations, with maximum positive and negative values approaching or exceeding 320 kW. Between 0:00–6:00 and 14:00–16:00, pronounced charging–discharging alternations occur. These frequent and high-intensity cycles cause large SOC swings and accelerate battery lifetime degradation. Scenario 5 helps extend battery lifetime and reduce maintenance costs by limiting the operating power of the battery and maintaining a relatively stable SOC.

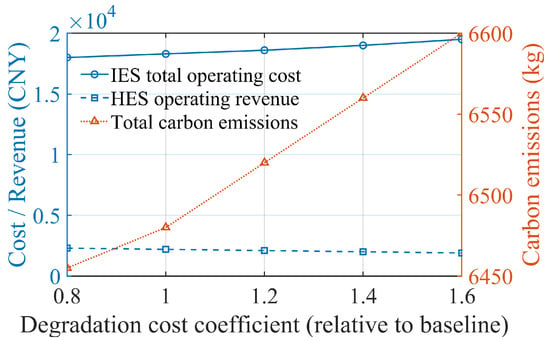

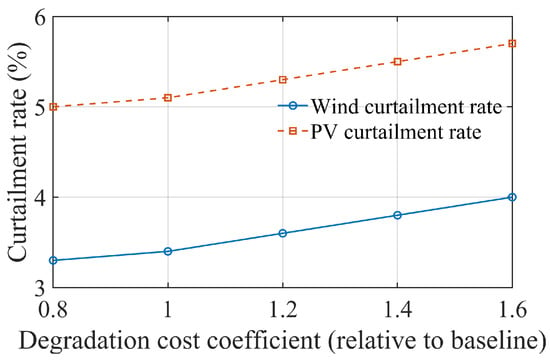

5.2. Key Parameter Sensitivity Analysis

To further validate the robustness of the proposed GCT–SCET bidirectional coordination and triple incentive strategy, key parameters are selected, including carbon price, green certificate price, and the degradation cost coefficient of hybrid energy storage. These parameters are perturbed within specified ranges around their baseline values. Sensitivity analysis is then conducted on IES comprehensive operating cost, ETH-HES operating revenue, system carbon emissions, and WT and PV curtailment rates.

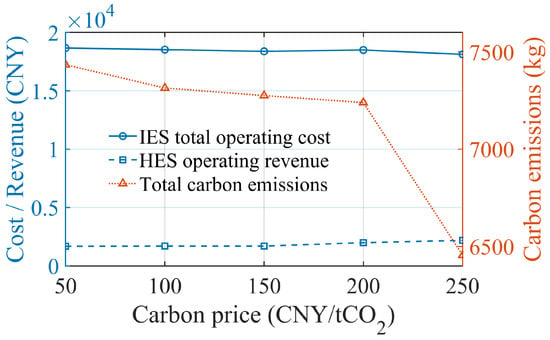

5.2.1. Sensitivity to Carbon Prices

With other parameters held constant, the benchmark carbon price and the marginal carbon prices in each tier of the tiered carbon trading mechanism are adjusted proportionally. As shown in Figure 9, an increase in the carbon price level raises the overall operating revenue of ETH-HES. The comprehensive operating cost of IES shows an initial slight increase and then gradually levels off.

Figure 9.

Sensitivity of IES performance to carbon price.

On one hand, higher carbon prices directly increase the marginal generation costs of high-emission units and lead to higher SCET expenditures. On the other hand, higher carbon prices strengthen the economic incentives for emission reduction. The dispatch strategy increasingly favors wind power, photovoltaics, and ETH-HES for peak shaving, valley filling, and cross-temporal and spatial transfer of green electricity. This enhances renewable energy utilization and energy storage arbitrage gains, partly offsetting the cost pressure caused by higher carbon prices and causing the comprehensive cost curve to flatten in the high carbon price range.

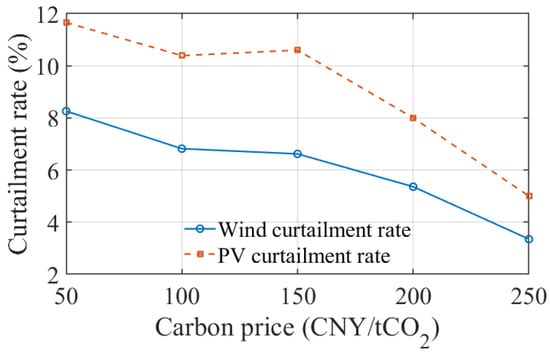

From an environmental perspective, Figure 9 shows that total carbon emissions decrease significantly as the carbon price increases. This indicates that the carbon price signal effectively drives the system to shift from high-emission generation schemes toward low-carbon operating modes. Emission constraints gradually evolve from “soft constraints” to “rigid constraints.” Figure 10 further shows that higher carbon prices lead to a general downward trend in wind and solar curtailment rates. Both wind and solar curtailment decrease significantly as the carbon price increases. This occurs because higher carbon costs restrict the grid access of fossil-fuel units and provide renewable energy with a competitive advantage in electricity supply. At the same time, the ETH-HES system transfers green electricity across time intervals and effectively absorbs wind and solar power that would otherwise be curtailed.

Figure 10.

Impact of carbon price on wind and PV curtailment.

In summary, within the parameter range of this case, a moderate increase in the carbon price helps achieve a reasonable trade-off among operating cost, carbon emissions reduction, and renewable energy integration. Carbon emissions and wind and solar curtailment decrease significantly, while the IES comprehensive cost increases only slightly and tends to stabilize. However, an excessively high carbon price may raise the overall energy cost of the system, so a balance is required between actual policy objectives and user affordability.

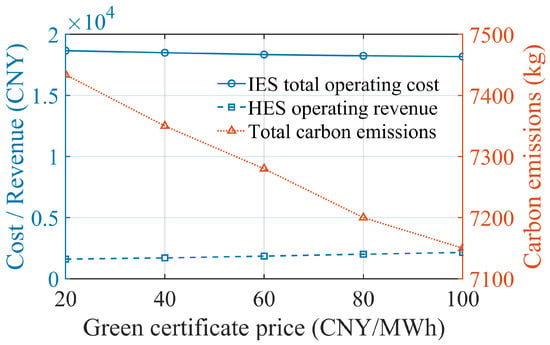

5.2.2. Sensitivity of Green Certificate Prices

With the green certificate quota coefficient held constant, interval perturbations are applied to the unit price of green certificates. As shown in Figure 11, an increase in the green certificate price significantly raises the operating revenue of ETH-HES, while the comprehensive operating cost of IES shows a gradual downward trend. Higher green certificate prices increase the “implicit revenue” associated with each unit of renewable energy injected into the grid. The net cost of GCT moves toward a larger negative value, indicating that income from green certificate trading continues to grow. This income compensates for and partially replaces revenue from conventional power generation, thereby reducing the overall system cost.

Figure 11.

Sensitivity of IES performance to green certificate price.

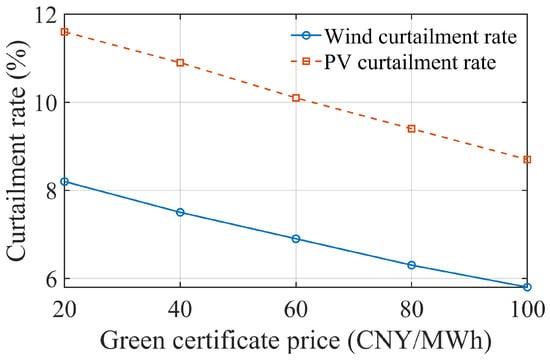

Figure 11 also shows that total carbon emissions decrease continuously as the green certificate price rises. This indicates that higher prices effectively incentivize the system to increase the share of wind and solar power generation and form, together with carbon trading, a combined emission-reduction constraint mechanism. In Figure 12, both wind and solar curtailment rates decrease as the green certificate price increases, with solar curtailment showing greater sensitivity to price changes. At low GCP levels, the incremental revenue from grid-connected PV is limited, which reduces the incentive to utilize surplus PV capacity. At higher GCP levels, ETH-HES tends to absorb excess PV power during low-load periods and release it during high-price or high-demand periods, balancing economic performance and utilization.

Figure 12.

Impact of green certificate price on wind and PV curtailment.

Overall, a moderate increase in the green certificate price can enhance renewable energy utilization and green certificate market activity without significantly increasing end-user energy costs. This creates synergistic incentives between GCT and SCET and further highlights the role of green certificate revenue in the proposed triple incentive strategy for ETH-HES operational decisions.

5.2.3. Sensitivity Analysis of Degradation Cost Coefficients for Hybrid Energy Storage Systems

For the degradation models of electrolytic cells and batteries, the equivalent degradation cost coefficient is varied around its baseline value. As shown in Figure 13, as the degradation cost coefficient increases, the comprehensive operating cost of IES rises in an almost linear manner, while the operating benefit of ETH-HES shows a monotonically decreasing trend. Higher degradation costs make frequent, deep charge–discharge cycles economically infeasible. The scheduling model therefore reduces energy storage actions associated with small peak–valley price differences or limited marginal benefits, which lowers arbitrage gains and increases the total operating cost of the system.

Figure 13.

Sensitivity of IES performance to degradation cost coefficient.

From a low-carbon perspective, Figure 13 shows that carbon emissions rebound slightly as the degradation cost coefficient increases, but they remain much lower than in the baseline scenario without energy storage or incentive mechanisms. In Figure 14, wind and solar curtailment rates show only modest increases at higher degradation cost coefficients. This indicates that even under strict degradation-cost constraints, ETH-HES still participates in peak shaving, valley filling, and renewable energy integration during critical periods, and its system-level low-carbon benefits remain largely preserved.

Figure 14.

Impact of degradation cost coefficient on wind and PV curtailment.

Compared with scenarios that ignore degradation costs, sensitivity analysis with varying degradation cost coefficients shows that neglecting lifetime degradation overestimates the economic benefits of hybrid energy storage and leads to overly aggressive charge–discharge strategies. Under reasonably set degradation costs, the ETH-HES operating strategy achieves a more robust trade-off among economic performance, lifetime utilization, and emission-reduction benefits. As a result, the proposed GCT–SCET bidirectional coordination and triple-incentive scheduling framework maintains favorable economic and environmental performance across a wide parameter range and demonstrates strong engineering applicability.

6. Conclusions

An IES low-carbon optimization scheduling strategy is proposed that accounts for the bidirectional interaction between green certificates and carbon trading, as well as the lifetime degradation of electrolyzers and batteries. The strategy aims to promote the green, low-carbon transformation of IES and enhance the economic viability of ETH-HES. The main conclusions are as follows:

- The proposed strategy effectively reduces both system carbon emissions and the comprehensive operating costs of the IES. Compared to the conventional model that only considers the GCT mechanism and the SCET mechanism, the model employing the bidirectional interaction mechanism between GCT and SCET reduces the comprehensive operating costs of the IES by 1.72% and lowers system carbon emissions by 0.53%, validating the effectiveness of the bidirectional interaction mechanism.

- The proposed strategy significantly enhances ETH-HES operational revenue and wind–solar power utilization rates. Compared to a triple incentive strategy excluding ETH-HES participation in GCT and SCET mechanisms, the strategy incorporating ETH-HES participation increases ETH-HES operational revenue by 76.16% and boosts wind–solar power utilization rates by 1.26% and 2.6%, respectively.

- Scheduling schemes accounting for electrolyzer and battery lifetime degradation costs proved more rational and comprehensive. Compared to strategies ignoring degradation costs, although hybrid storage operational revenue slightly decreased, the IES’s comprehensive operating costs decreased by 4.4%, carbon emissions decreased by 10.84%, and wind and solar power utilization rates increased by 2.01% and 3%, respectively.

Despite the promising performance of the proposed strategy, several limitations remain. The main limitation is that the simulation time horizon is restricted to a single typical day. This setting cannot fully capture inter-day and seasonal variations in load, renewable generation profiles, market prices, and policy signals, nor the cumulative impact of degradation over longer operating periods.

Future work will extend the temporal scope of the case studies by introducing multiple typical days and seasonal representative scenarios and by constructing multi-day or even year-long representative operating conditions. This will enable a more systematic assessment of the long-term economic performance and degradation effects of ETH-HES. Future research will also examine the model’s applicability in regions with different carbon trading and green certificate policies and develop refined optimization strategies for longer time horizons to enhance the practicality and potential for wider deployment of the proposed framework.

Author Contributions

Methodology, H.H.; Software, X.Z.; Validation, P.Z.; Formal analysis, X.Z.; Writing—original draft, H.H.; Writing—review & editing, W.D. and Y.S.; Visualization, G.S.; Supervision, P.Z., Z.L. and Y.S.; Project administration, Z.L. and Y.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Project of State Grid Inner Mongolia Eastern Electric Power Co., Ltd. (52660024000G). We gratefully acknowledge this support.

Data Availability Statement

Due to privacy concerns, the data is not publicly accessible.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Hao Hu, Xuenan Zhao, Guozheng Shang, Pengyu Zhao and Wenjing Dong were employed by the company State Grid Inner Mongolia Eastern Electric Power Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The authors declare that this study recevied funding from State Grid Inner Mongolia Eastern Electric Power Co., Ltd. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Abbreviation | Description | |

| IES | Integrated energy system | |

| ETH-HES | Electric–thermal–hydrogen hybrid energy storage system | |

| HES | Hybrid energy storage system | |

| GCT | Green certificate trading | |

| SCET | Stepwise carbon emission trading | |

| PV | Photovoltaic (solar power generation) | |

| WT | Wind turbine (wind power generation) | |

| GT | Gas turbine | |

| WHB | Waste heat boiler | |

| GB | Gas boiler | |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide | |

| CNY | Chinese yuan | |

| Symbol | Description | Unit |

| t | Index of time period | – |

| T | Number of time periods in the scheduling horizon | – |

| h | Duration of each time period | h |

| Output power of the GT at time t | kW | |

| Heat output of the WHB at time t | kW or kWth | |

| Heat output of the GB at time t | kW or kWth | |

| Electric power purchased from the main grid at time t | kW | |

| Active power output of the WT at time t | kW | |

| Active power output of the PV system at time t | kW | |

| Total carbon emissions of the integrated energy system in the scheduling horizon | kg | |

| Carbon emission allowance (quota) of the integrated energy system | kg | |

| Equivalent renewable generation volume or number of green certificates from WT and PV | –/certificate | |

| Equivalent carbon emission reduction corresponding to the acquired green certificates | kg | |

| Net carbon emission trading volume after the interaction between GCT and SCET | kg | |

| Carbon emission factor per unit heat supplied | kg/kWh | |

| Carbon emission allowance per unit heat supplied | kg/kWh | |

| Carbon emission factor per unit electricity purchased from the grid | kg/kWh | |

| Carbon emission allowance per unit electricity purchased from the grid | kg/kWh | |

| Conversion coefficient between GT electric output and supplied heat | – | |

| Coefficient converting WT and PV generation into green certificates | certificate/kWh | |

| Emission reduction equivalent per unit green certificate in GCT | kg/certificate | |

| Total operating cost of the integrated energy system (energy purchase, fuel, carbon, etc.) | CNY | |

| Operating revenue of the hybrid energy storage system | CNY | |

| Cost (or revenue) of SCET | CNY | |

| Net cost (negative for revenue) of GCT | CNY | |

| CE | Total system carbon emissions in a given scenario | kg |

| Wind power curtailment rate | % | |

| PV power curtailment rate | % |

References

- Chen, Z.; Li, Z.; Lin, D.; Xie, C.; Wang, Z. Multi-Time-Scale Optimal Scheduling of Integrated Energy System with Electric-Thermal-Hydrogen Hybrid Energy Storage Under Wind and Solar Uncertainties. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2025, 13, 904–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Xu, X.; Cheng, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, H.; Liu, D. Robust configuration planning for net zero-energy buildings considering source-load dual uncertainty and hybrid energy storage system. Build. Environ. 2025, 282, 113239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Hu, X.; Zhang, K.; Xie, Y.; He, J.; Song, Z. Enabling high-fidelity electrothermal modeling of electric flying car batteries: A physics-data hybrid approach. Appl. Energy 2025, 388, 125633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Fu, Y.; Li, C.; Li, J.; Xing, Z.; Ma, T. Improving wind power integration by regenerative electric boiler and battery energy storage device. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 131, 107039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chang, X.; Xue, Y.; Su, J.; Dou, Y.; Han, X.; Sun, H. Optimal multi-timescale economic dispatch for Antarctic microgrids considering a hybrid electric–hydrogen–thermal energy storage system. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 345, 120353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Song, W.; Feng, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y. Energy management strategy and capacity optimization for CCHP system integrated with electric-thermal hybrid energy storage system. Int. J. Energy Res. 2020, 44, 1125–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Abdalla, A.N. Coordinated dispatch of electric, thermal, and hydrogen vectors in renewable-enriched microgrids using constrained harris hawks optimization under uncertainty. Renew. Energy 2026, 256, 124064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaillan, H.M.; Tohidi, S.; Hagh, M.T.; Tabar, V.S. Risk-aware day-ahead planning of a zero energy hub integrated with green power-to-hydrogen technology using information gap decision theory and stochastic approach and considering demand side elasticity. Energy Rep. 2023, 10, 4302–4317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, N.; Hu, Z.; Mrzljak, V.; Arabi Nowdeh, S. Stochastic techno-economic optimization of hybrid energy system with photovoltaic, wind, and hydrokinetic resources integrated with electric and thermal storage using improved fire Hawk optimization. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaker, H.; Rasouli, A.; Alobaidi, A.H.; Sedighizadeh, M. Optimal dispatch of multi-carrier energy system considering energy storage and electric vehicles. J. Energy Storage 2024, 90, 111794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Gao, J.; Gao, L.; Yang, S.; Chen, S. Scheduling strategy for an electricity-heat-gas hybrid energy storage microgrid system considering novel combined heat and power units. Energy Rep. 2025, 13, 4719–4733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Zou, C.; Dong, M.; Chi, H.; Yan, Y.; Jiang, S. Feasibility study: Economic and technical analysis of optimal configuration and operation of a hybrid CSP/PV/wind power cogeneration system with energy storage. Renew. Energy 2024, 225, 120273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Xu, C.; Chen, W. Modeling and configuration optimization of the rooftop photovoltaic with electric-hydrogen-thermal hybrid storage system for zero-energy buildings: Consider a cumulative seasonal effect. Build. Simul. 2023, 16, 1799–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emrani-Rahaghi, P.; Hashemi-Dezaki, H. Optimal scenario-based operation and scheduling of residential energy hubs including plug-in hybrid electric vehicle and heat storage system considering the uncertainties of electricity price and renewable distributed generations. J. Energy Storage 2021, 33, 102038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Wang, J.; Yin, Z.; Kang, J.; Ma, Z. Optimization of a solar-driven community integrated energy system based on dynamic hybrid hydrogen-electric energy storage strategy. J. Energy Storage 2024, 101, 113917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.Y.; Wang, Z.H.; Li, M.C.; Li, L.L. Optimization and performance analysis of integrated energy systems considering hybrid electro-thermal energy storage. Energy 2025, 314, 134172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Sun, W.; Sun, L. Dynamic programming based economic day-ahead scheduling of integrated tri-generation energy system with hybrid energy storage. J. Energy Storage 2021, 44, 103395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.K.; Koley, C.; Gope, S. A two-stage optimal scheduling strategy of hybrid energy system integrated day-ahead electricity market. Int. J. Environ. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 23, 231–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, O.; Dincer, I. Development of a sustainable energy system utilizing a new molten-salt based hybrid thermal energy storage and electrochemical energy conversion technique. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2020, 42, 100866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Liao, B.; Su, Y.; Li, S. Multi-objective and multi-algorithm operation optimization of integrated energy system considering ground source energy and solar energy. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2023, 144, 108529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Fu, Y.; Jia, Q.; Wen, S. Optimal dispatch of integrated energy microgrid considering hybrid structured electric-thermal energy storage. Renew. Energy 2022, 199, 628–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.; Sun, P.; Hui, Q.; Li, Y.; Chen, Z. A model of electro-thermal hybrid energy storage system for autonomous control capability enhancement of multi-energy microgrid. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2019, 5, 489–497. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P.S.; Chandrasena, R.P.S.; Ramu, V.; Srinivas, G.N.; Babu, K.V.S.M. Energy management system for small scale hybrid wind solar battery based microgrid. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 8336–8345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oskouei, M.Z.; Mohammadi-Ivatloo, B.; Abapour, M.; Razzaghi, R. Optimal stochastic scheduling of reconfigurable active distribution networks hosting hybrid renewable energy systems. IET Smart Grid 2021, 4, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, M.; Afsharnia, S.; Farhangi, S. Stochastic power management strategy for optimal day-ahead scheduling of wind-HESS considering wind power generation and market price uncertainties. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2022, 134, 107429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, M.; Liu, S.; Qi, M.; Liu, S.; Shu, C.; Feng, W.; Liu, Y. Optimization of wind-solar hybrid system based on energy stability of multiple time scales and uncertainty of renewable resources. Energy 2024, 313, 133790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Deveci, M.; Yan, J.; Liu, Y. Optimal capacity configuration of wind-photovoltaic-storage hybrid system: A study based on multi-objective optimization and sparrow search algorithm. J. Energy Storage 2024, 85, 110983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Yang, H.; Ding, S.; Tian, Z.; Guo, B.; Chen, H.; Yang, F.; Xu, N. Model simulation and multi-objective capacity optimization of wind power coupled hybrid energy storage system. Energy 2025, 319, 134887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Xu, J.; Ge, L.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Xu, L.; Tang, Z. Economic optimization operation approach of integrated energy system considering wind power consumption and flexible load regulation. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2024, 19, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Tahir, M.; Siano, P.; Hussain, S.; Sun, W.; He, Y.; Meng, Q. A bi-level hybrid game framework for stochastic robust optimization in multi-integrated energy microgrids. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2025, 44, 102024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Gao, Q.; Ji, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, H.; Jiang, Y. A supply–demand optimization strategy for integrated energy system considering integrated demand response and electricity–heat–hydrogen hybrid energy storage. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2025, 42, 101658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Gao, Q.; Ji, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, H. Operation strategy for community integrated energy system considering source–load characteristics based on Stackelberg game. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 254, 123739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Ji, Y.; Zhu, L.; Liu, J.; Gao, X.; Chen, H.; Gao, Q. Interactive optimization of electric vehicles and park integrated energy system driven by low carbon: An incentive mechanism based on Stackelberg game. Energy 2025, 318, 134799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Zhao, S.; Chen, H.; Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, L. Optimal dispatch of a multi-energy complementary system containing energy storage considering the trading of carbon emission and green certificate in China. Energy 2025, 314, 134215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.