Abstract

This research investigates a methane-fueled open gas system, enhanced by Prof. Szewalski’s idea of venting exhaust gases at various turbine stages. It assesses the impact of hydrogen co-combustion, which can range from 0% to 100%, on system parameters. The novel approach increased the gas turbine’s electrical efficiency to 41.25%. Two additional heat exchangers raised the inlet fluid temperature, affecting the exhaust gases entering the turbine. The highest exhaust gas temperature reached was 1491.08 °C. A higher hydrogen ratio significantly lowered CO2 emissions. The study’s originality lies in its innovative technology combination, allowing flexible combustion adjustments to meet energy demands and fuel availability. The gas turbine model provides a detailed analysis of cooling air at each expander stage, enhancing understanding of efficiency factors. Integration with Power-to-Fuel technology facilitates the creation of energy systems that efficiently store and use renewable energy. This contributes to sustainable energy technology development, crucial for achieving climate goals and reducing emissions.

1. Introduction

In recent years, there has been a dynamic growth in the importance of renewable energy sources (RESs) in the global electricity generation structure. This has been driven by the deteriorating global climate situation and an increase in society’s awareness related to environmental protection [1]. Under the Paris Agreement in 2015, all countries worldwide committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions and limiting global warming to below 2 °C compared to pre-industrial levels [2,3,4]. The use of renewable energy sources plays a crucial role in achieving these goals; however, there are many challenges associated with these technologies. RESs include wind and solar energy, among others. Electricity generated from these sources is unstable, with production primarily influenced by the time of day and year, as well as weather conditions [1,5]. This necessitates the development of expensive energy storage systems. Various types of storage systems can be used in power systems, including chemical, electrochemical, electromagnetic, thermal, or mechanical storage [6,7,8,9].

An alternative could be gas turbine systems, which can rapidly respond to changes in electricity demand. Gas turbines are characterized by their small size relative to the generated power, quick start-up, and the ability to integrate with other energy sources, such as Rankine cycles [10]. Although gas turbine systems are characterized by relatively high efficiency in electricity generation, due to the high cost of fuel and continuously increasing emission standards, several methods for increasing their efficiency are advocated [11,12,13].

One of the most classic methods of increasing efficiency is to increase the temperature and pressure of the exhaust gases at the inlet to the gas turbine expander [11]. This method is associated with many challenges due to the limited mechanical strength of certain components of the gas turbine structure. Blades of the turbine are particularly vulnerable to thermal and mechanical loads induced by centrifugal force. They are primarily made of nickel and cobalt superalloys and additionally coated with a thermal barrier [14,15,16]. The advancement in materials engineering has led to the development of increasingly better materials for coating turbine blades. Among these are Thermal Barrier Coatings (TBCs), which, when applied to the metal surface, provide additional thermal protection, leading to an extension of their lifespan [17]. Due to numerous turbine blade failures, in order to limit them and thereby improve the efficiency of gas turbine systems, continuous research on Thermomechanical Fatigue (TMF) of turbine blades is crucial.

Another way to increase the efficiency of a gas turbine is through heat regeneration. The essence of this modernization is to preheat the air supplied to the combustion chamber using the expanded exhaust gases from the gas turbine expander. The temperature of the exhaust gases at the turbine outlet is relatively high and installing an additional heat exchanger allows for the utilization of their thermal potential [12,18]. Supplying preheated air to the combustion chamber allows for injecting less fuel, resulting in increased efficiency of the gas turbine cycle, as demonstrated, for example, in the article [19].

Increasing the electrical efficiency of a gas turbine can also be achieved by employing interstage cooling of compressed air. Lowering the temperature of the compressed air reduces the power consumed by the compressor, theoretically resulting in increased efficiency. However, reducing the temperature of the air before it enters the combustion chamber leads to an increase in the amount of fuel supplied to the combustion chamber to achieve a higher temperature of the resulting exhaust gases. In this case, it is justified to use additional heat regeneration to increase the temperature of the air before it enters the combustion chamber [20,21].

Another method to increase the efficiency of a gas turbine is the use of steam injection into the combustion chamber, known as the Steam-Injected Gas Turbine (STIG). This technique aims to increase the flow of exhaust gases passing through the gas turbine rotor, leading to increased power generation without an increased power consumption by the compressor. Turbines with steam injection are used in the Cheng cycle system. This system combines the gas turbine cycle with a heat recovery boiler, where steam is generated and supplied to the combustion chamber in the gas turbine cycle [22,23,24].

A lesser-known method for improving efficiency in gas turbine systems, which has not yet been applied in industry, is the modernization based on Szewalski’s idea.

According to Szewalski, the essence of the modernization is the installation of two additional heat exchangers and exhaust gas outlets behind the gas turbine. The proposed concept is based on internal heat regeneration using exhaust gases, achieved by partially removing them from the turbine and reusing them as a heating medium in heat exchangers. Unlike classic external heat recovery cycles, such as gas–steam systems or conventional Brayton regenerative cycles, the energy from the exhaust gases is not transferred to a separate working cycle, but directly supports the process of preparing the working medium upstream of the combustion chamber. The key thermodynamic mechanism of the modernization according to Szewalski’s idea is to increase the temperature of the compressed air while maintaining its high pressure, which results in a reduction in fuel consumption and an improvement in the efficiency of the combustion process in the combustion chamber. An important feature of Szewalski’s concept is also the ability to control the amount and location of exhaust gas collection from individual turbine stages, which allows for optimization of the compromise between mechanical work loss and heat recovery efficiency. The method of increasing efficiency through modernization according to Szewalski’s idea was presented in the article [23]. The authors compared the results obtained for the operation of the base gas–steam unit in Gorzów Wielkopolski, operating with the GT8C turbine, with the same unit modernized according to Szewalski’s idea. The analysis was performed using two programs: COM-GAS and Aspen Plus. Numerical simulations showed that the modernization can increase the electrical efficiency of the gas turbine from approximately 34.3% to 36% and the overall combined cycle unit from 41.2% to 42.8%, while reducing fuel consumption and CO2 emissions. However, the studies also highlighted several limitations: the total electrical output of the installations decreases, and the modernization requires significant investment in additional heat exchangers, compressors, and turbine modifications. [23]. Szewalski’s idea was also presented in the article [25].

Due to the increasing consumption of traditional fossil fuels such as coal and oil, there has been a growing interest in hydrogen as a fuel in the energy market in recent years [26,27]. For a very long time, the main fuels used in gas turbines were oil and natural gas. In installations with gas turbines, the fuel used in the combustion chamber plays a crucial role in influencing the combustion efficiency and the potential emission of harmful substances during this process [10]. Hydrogen used as fuel is characterized by a high heating value, which ranges from 120 to 142 MJ/kg [28,29]. Additionally, during its combustion, no harmful substances such as carbon dioxide are emitted into the environment. The by-product of the process is water, which can be further utilized for other processes.

Despite its many advantages, hydrogen usage also presents several challenges that need to be faced. Hydrogen is a lightweight, explosive gas, making its storage problematic. Due to its different combustion properties compared to, for example, methane, the use of hydrogen blends in fuel may require the reconstruction of burners and other elements located in the combustion chamber [30,31]. The burning rate of hydrogen in the combustion chamber is over 10 times faster than the burning rate of methane [32]. There is also a possibility of flame flashback. Hydrogen burns explosively, and during this process, a cloud is formed that moves upwards and backwards along the fuel line [33,34].

Due to the increasing interest in hydrogen as a fuel, many companies have started testing and conducting numerous studies on gas turbines for co-firing and full hydrogen combustion. The first gas turbine powered by 100% hydrogen was constructed and operated by Kawasaki Heavy Industries in 2020. The turbine’s operation was based on low-NOx dry combustion technology [35]. Three years later, in March 2023, Siemens also successfully presented a gas turbine powered by 100% hydrogen [36,37].

Another company, Mitsubishi, in collaboration with its clients, is developing an action plan aimed at reducing carbon dioxide emissions by implementing hydrogen fuel on a large scale. The company produces gas turbines that allow for co-firing and, in the near future, complete hydrogen combustion. In November 2023, a successful demonstration of a gas turbine burning a fuel mixture containing 30% hydrogen and methane by volume was completed, under both partial and full load conditions. The demonstration took place at a hydrogen park in western Japan [38,39]. Mitsubishi Power is also conducting numerous research and development projects focused on developing low-NOx dry combustion technology that will enable 100% hydrogen combustion in the future. This work is currently in the research and development testing phase, and the results have not yet been published in scientific literature [38,40]. Due to the explosive and flammable properties of hydrogen, particular attention should be paid to safety when using hydrogen as a co-fired fuel or burned in a gas turbine [41].

Positive environmental results due to co-firing or complete hydrogen combustion in a gas turbine have been presented in numerous articles. The authors of these works [42,43,44] unanimously argue that using hydrogen as an additional fuel effectively reduces the emission of carbon dioxide into the environment during the operation of a gas turbine. The development and implementation of hydrogen-powered gas turbines can significantly contribute to improving the environmental situation worldwide. In this article, besides the environmental aspects of using hydrogen as fuel, thermodynamic changes in selected parameters of the analyzed system have also been presented.

Scientific Originality and Novelty

The scientific originality and innovation of the presented thermodynamic analysis of a 2 MW gas turbine, utilizing Prof. Szewalski’s idea and co-firing of hydrogen, is manifested through an innovative combination of technologies that allows for flexible adjustment of the combustion process to current energy needs and fuel availability. Unlike previous studies on the Szewalski cycle [23,25], this work combines this cycle with the possibility of hydrogen co-combustion, which allows the turbine to be adapted to changing market and environmental conditions and integrated with renewable technologies. The possibility of co-firing hydrogen in the range from 0% to 100% represents a breakthrough in adapting gas turbines to changing market and ecological conditions, which is crucial for energy transformation. Unlike previous studies on hydrogen combustion or co-combustion systems [42,43,44], which focused mainly on emission reduction. The applied gas turbine model takes into account not only basic thermodynamic parameters, but also thoroughly analyzes the amount of cooling air at each stage of the expander, which is rare in the literature and allows for a deeper understanding of the impact of various factors on turbine efficiency. Integration with Power-to-Fuel technology opens up new possibilities for creating integrated energy systems that can effectively store and utilize renewable energy. The presented analysis contributes to the development of sustainable energy technologies, which are necessary to achieve climate goals and reduce CO2 emissions, demonstrating the potential of the gas turbine as an element of the future, low-emission energy system.

The following sections of the publication present the calculation methodology, followed by schematics with a detailed description of the system and its main assumptions. In the fourth chapter, the results of the conducted analysis are presented, including numerous figures. Subsequently, a discussion of practical challenges and limitations related to hydrogen co-firing is provided, covering safety, material, and regulatory aspects. Finally, the main conclusions derived from the conducted study are summarized and discussed.

2. Methodology of Calculation

All calculations for the 4 analyzed variants of the gas system according to Szewalski’s idea were carried out using the methodology outlined below.

The electrical efficiency of the gas turbine is determined by the ratio of the electrical power output of the gas turbine to the product of the fuel mass flow rate and the lower heating value of the fuel supplied to the combustion chamber . This product can be expressed differently as the chemical energy of the fuel supplied to the system :

The thermal efficiency of the gas turbine is defined as the ratio of the internal power of the gas turbine to the heat flow supplied to the gas turbine :

When determining the relevant parameters, the heat flow supplied to the gas turbine is calculated from the equation,

where:

- —enthalpy of the fluid at the inlet to the combustion chamber;

- —mass flow rate of the fluid at the inlet to the combustion chamber;

- —enthalpy of the fluid at the outlet from the combustion chamber;

- —mass flow rate of the fluid at the outlet from the combustion chamber.

The exhaust gas flow leaving the gas turbine α is the ratio of the heat flow of the exhaust gas leaving the gas turbine to the electrical power of the gas turbine :

The heat flow of the exhaust gas leaving the gas turbine is expressed as the product of the mass flow rate and the enthalpy of the exhaust gas at the outlet from the gas turbine:

The isentropic efficiency of compressors depends on the total compression ratio and is defined based on the methodology adopted, among others, in references [45,46]. It is based on the polytropic efficiency as a function of the compression ratio according to reference [47]:

where:

- —average isentropic exponent;

- R—individual value of the gas constant: .

The average specific heat for a gas process is defined by the formula:

where:

- —temperature of the fluid at the inlet to the compressor;

- —temperature of the fluid at the outlet from the compressor;

- —temperature from the parametric tables of an ideal gas contained in [48,49].

The isentropic efficiency of the turbine is also based on the polytropic efficiency according to reference [45] and is expressed by the formula based on reference [48]:

Analogously to Equation (8), the average specific heat for an isentropic process has been determined using the following formula:

where:

- —temperature at the inlet to the gas turbine;

- —outlet temperature after the gas turbine.

In the analyzed gas system according to Szewalski’s idea, the TIT (Turbine Inlet Temperature) is determined in accordance with the International Standard 2314—Gas Turbines—Acceptance Test [50] and is treated as the theoretical temperature at the inlet to the first-stage expander, where the entire mass flow of cooling air mixes with the exhaust gases.

The cooling ratio is expressed as the ratio of the mass flow rate of cooling to the mass flow rate of air at the inlet to the gas turbine :

In the analyzed gas system, a detailed turbine cooling model has been applied, the principle of which arises from the heat flow balance in the turbine blade system. It is presented in works [51,52,53] and expressed by the formula:

where:

- —mass flow rate, average specific heat, inlet temperature, and outlet temperature of the gas feeding a particular stage of the gas turbine expander;

- —average heat transfer coefficient of the turbine blade, the heat exchange surface area in the blade, and the temperature of the turbine blade material;

- —mass flow rate, average specific heat, inlet temperature, and outlet temperature of the cooling air for a particular stage of the gas turbine.

The heat flow balance equation in the turbine blade system introduces dependencies that describe the mass flow rate of the gas , the dimensionless Stanton number St, and the cooling efficiency .

The mass flow rate of the gas is the product of the sectional area of the gas flow , the gas velocity and the gas density :

The cooling efficiency is expressed as the ratio of the temperature difference in the cooling air stream at the inlet and outlet at a given stage of the gas turbine to the product of the temperature difference between the blade material and the cooling air inlet temperature at a given stage of the gas turbine:

The dimensionless Stanton number is described by the formula:

The ratio of the mass flow rate of cooling air to the mass flow rate of air at the compressor inlet can be obtained using Equations (11)–(14) and is expressed as:

where:

To obtain the mass flow rate of cooling air for a given turbine stage Equation (17) needs to be appropriately rearranged, introducing parameter , which is associated with the cooling efficiency of the gas turbine and can be calculated using the formula:

The parameters and appearing in Equation (8) can be expressed as:

where:

- —enthalpy of the gas feeding a specific stage of the expander at the blade temperature ;

- —enthalpy of the cooling air for a specific stage of the expander at the blade temperature ;

- —enthalpy of the gas at the inlet to a specific stage of the gas turbine expander;

- —enthalpy of the inlet air cooling a specific stage of the gas turbine.

In the system, the Wobby number was used to investigate the limit for the use of a mixture of two fuels, where no combustion chamber reconstruction would be necessary. The Wobby number is the ratio of the lower heating value to the square root of the mass of the gas divided by the mass of air :

3. Scheme and Assumptions

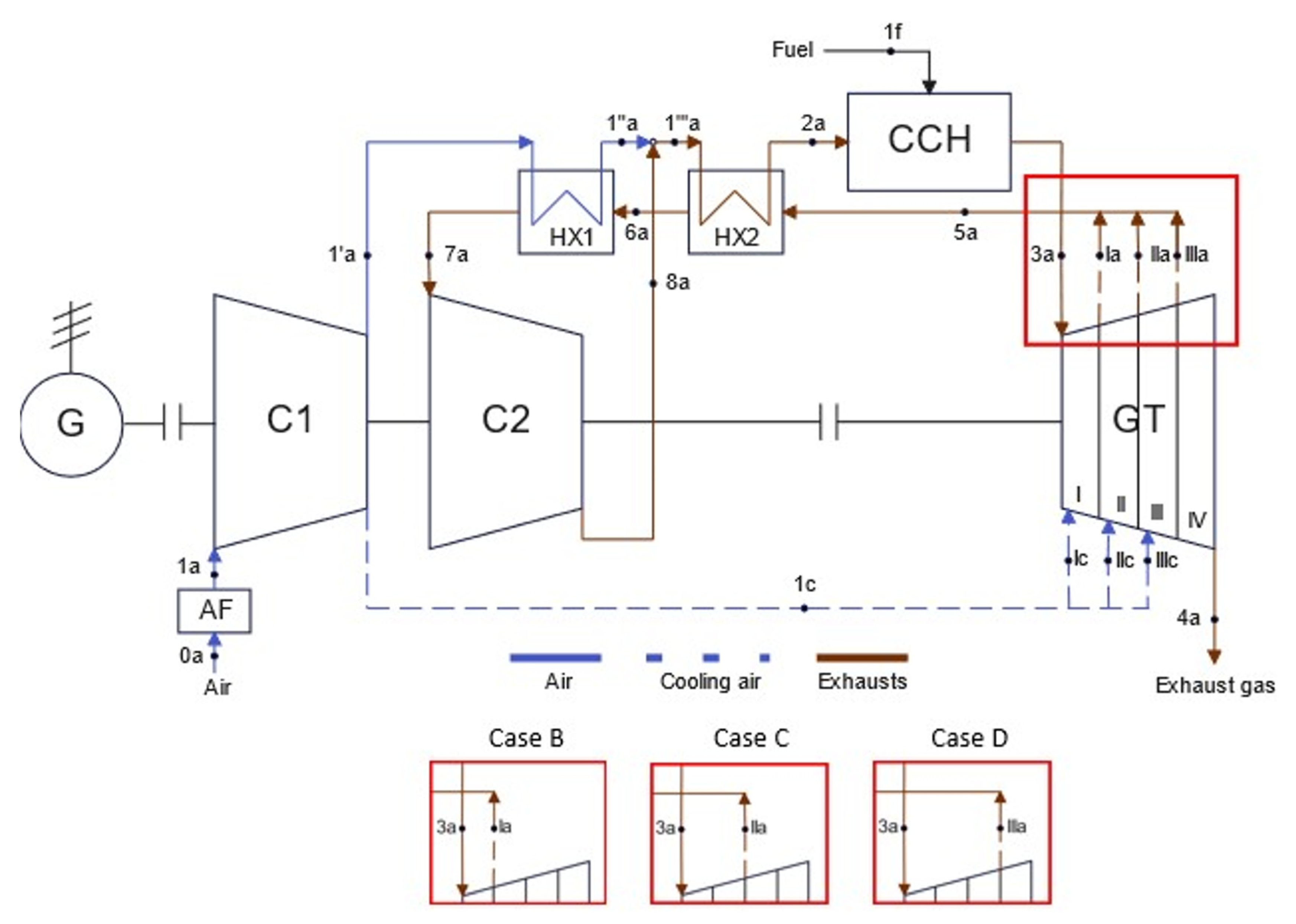

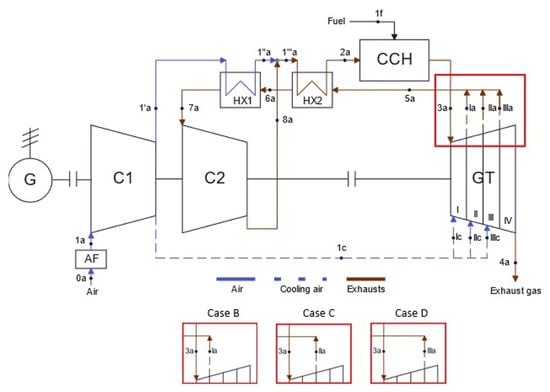

The gas system was subjected to analysis following Szewalski idea-based modernization. The essence of this modernization involves the installation of two additional heat exchangers, which are intended to preheat the fluid at the inlet to the combustion chamber. Preheating is possible thanks to the hot flue gases vented after the I, II and III stages of the gas turbine. Additionally, a second compressor has been implemented, which compresses the exhaust gases to predetermined parameters, and then directs them to a mixer, where they further proceed to the combustion chamber.

In the analyzed gas system, the gross electrical power is 2 MW. In the reference variant, the fuel burned is 100% methane, while in the modified system, hydrogen is added in appropriate percentage proportions. The main assumptions of the parameters used for the calculations are presented in Table 1. All calculations were performed for four model variants:

Table 1.

Assumptions of the analysed gas system according to Szewalski’s idea.

- A—Reference variant (without exhaust vent); fuel burned—100% methane.

- B—Exhaust vent behind the I stage of the gas turbine; fuel burned—methane with hydrogen (0–100%).

- C—Exhaust vent behind the II stage of the gas turbine; fuel burned—methane with hydrogen (0–100%).

- D—Exhaust vent behind the III stage of the gas turbine; fuel burned—methane with hydrogen (0–100%).

Section 4 presents the results of the analysis for variants B, C and D. The results presented for these variants for the value of vented flux = 0 kg/s and share of hydrogen = 0% in each graph are the results for variant A.

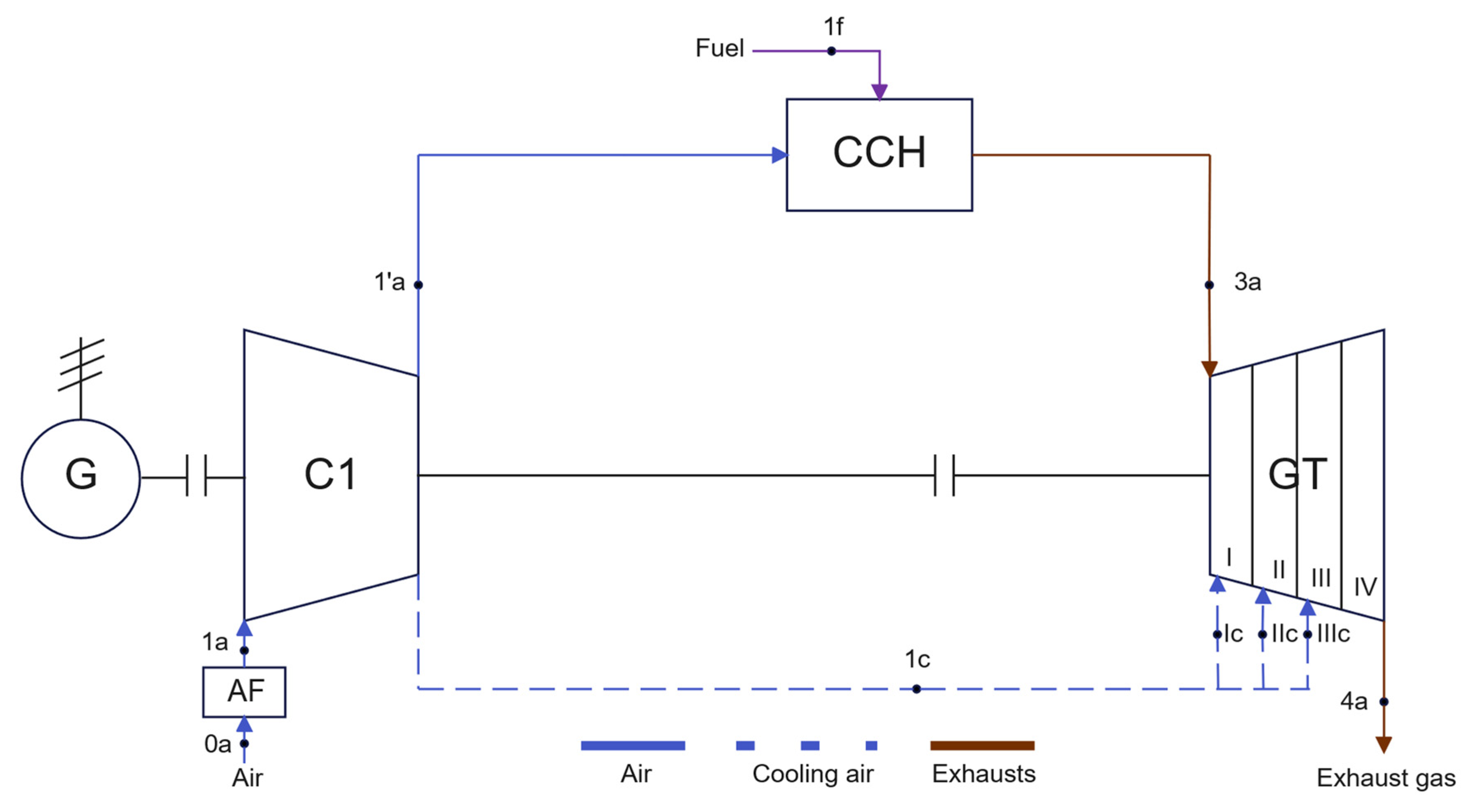

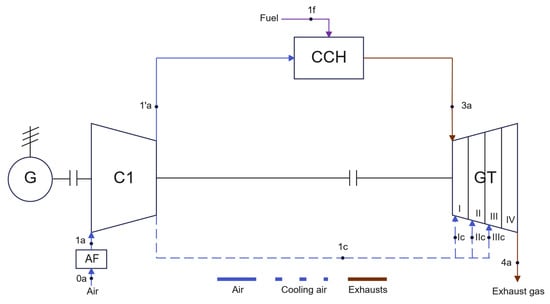

Figure 1 shows a schematic of the reference gas system with the turbine cooling system used. This system consists of an air filter, compressor, combustion chamber, generator and gas turbine. Air with a temperature of 15 °C is taken from the environment, cleaned in the air filter, and then supplied to the compressor. The compressed air is directed to the combustion chamber. The resulting exhaust gas passes through 4 gas turbine expander stages. Each is cooled with air to achieve a blade metal temperature of 1000 °C to prevent damage to the blade. The flow of exhaust gas generates mechanical power, which powers a compressor located on one shaft, and directs the excess of this power to a generator, where it is converted to electricity.

Figure 1.

Gas system of the reference variant (AF—air filter, C—compressor, CCH—combustion chamber, GT—gas turbine, G—generator).

Figure 2 shows the schematic diagram of the gas system according to Szewalski’s idea. As in the reference system, air taken from the environment and cleaned is supplied to the compressor. The compressed air passes through the first heat exchanger, where its temperature is raised. After the first heat exchanger, there is a mixer, into which air, along with previously compressed exhaust gases to the state specified at point 8a, flows. The mixture of air and exhaust gases after the mixer passes through the second heat exchanger to further increase its temperature before entering the combustion chamber. The medium with fuel is burned in the combustion chamber, and the resulting exhaust gases pass through the gas turbine expander. Additionally, behind the I, II, and III stages of the expander, there are outlets with control valves, through which a selected stream of exhaust gases can be released. The released stream of exhaust gases is redirected and enters the two aforementioned heat exchangers. Passing through the heat exchangers, it releases thermal energy and is directed to the compressor. The remaining exhaust gases after the expander are directed to the surroundings. The system also incorporates a model for cooling the rotor blade at the I, II, and III stages of the gas turbine.

Figure 2.

Gas system according to Szewalski’s idea (AF—air filter, C—compressor, HX—heat exchanger, CCH—combustion chamber, GT—gas turbine, G—generator).

The gas turbine model applied in this study, including a detailed description of the turbine blade cooling system, is based on an approach that has been repeatedly verified and widely used in the literature. The fundamentals of the cooling model, including the formalism based on the Stanton number and blade heat balance relations, were originally proposed and extensively analyzed by Sanjay and co-authors, who demonstrated its validity in combined-cycle power plant analyses [52]. The same approach, with identical values of the key model parameters (blade temperature of approximately 1000 °C, parameter , and Stanton number ), was subsequently applied and further developed in the works of Prof. Kotowicz’s research group, where the gas turbine model was validated against literature data and recognized reference cases, confirming its capability to reliably reproduce cooling flow requirements and the impact of cooling on overall system efficiency [45,54]. Although the referenced analyses concerned large-scale gas turbines ~200 MW), in the present study analogous dimensionless parameters were adopted for a 2 MW turbine, assuming the preservation of geometric, thermal, and flow similarity. This assumption is consistent with industrial practice in scaling gas turbine families and is justified by the comparative nature of the conducted analyses.

4. Analysis of Results

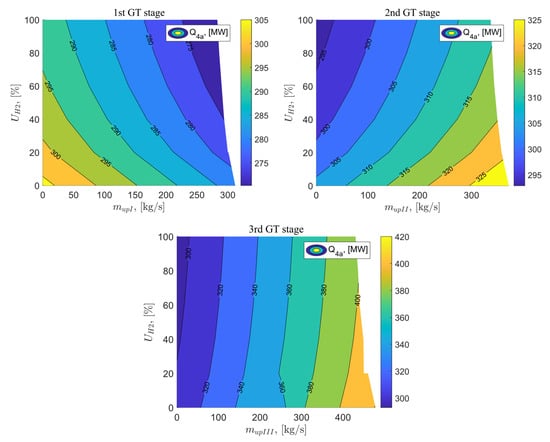

The gas system based on Szewalski’s idea was analyzed. The impact of the exhaust gas vent behind the I, II, and III stages of the gas turbine expander, as well as the respective percentage shares of hydrogen in the fuel, on selected system performance characteristics were investigated. All simulations were conducted using Ebsilon Professional software. The results of the analysis are presented sequentially for each parameter and all considered variants. The exhaust gas vent was varied from 0 kg/s (reference variant) to the maximum value, ensuring safe operation of the system for each variant, as depicted by the irregular nature of the charts on the right-hand side.

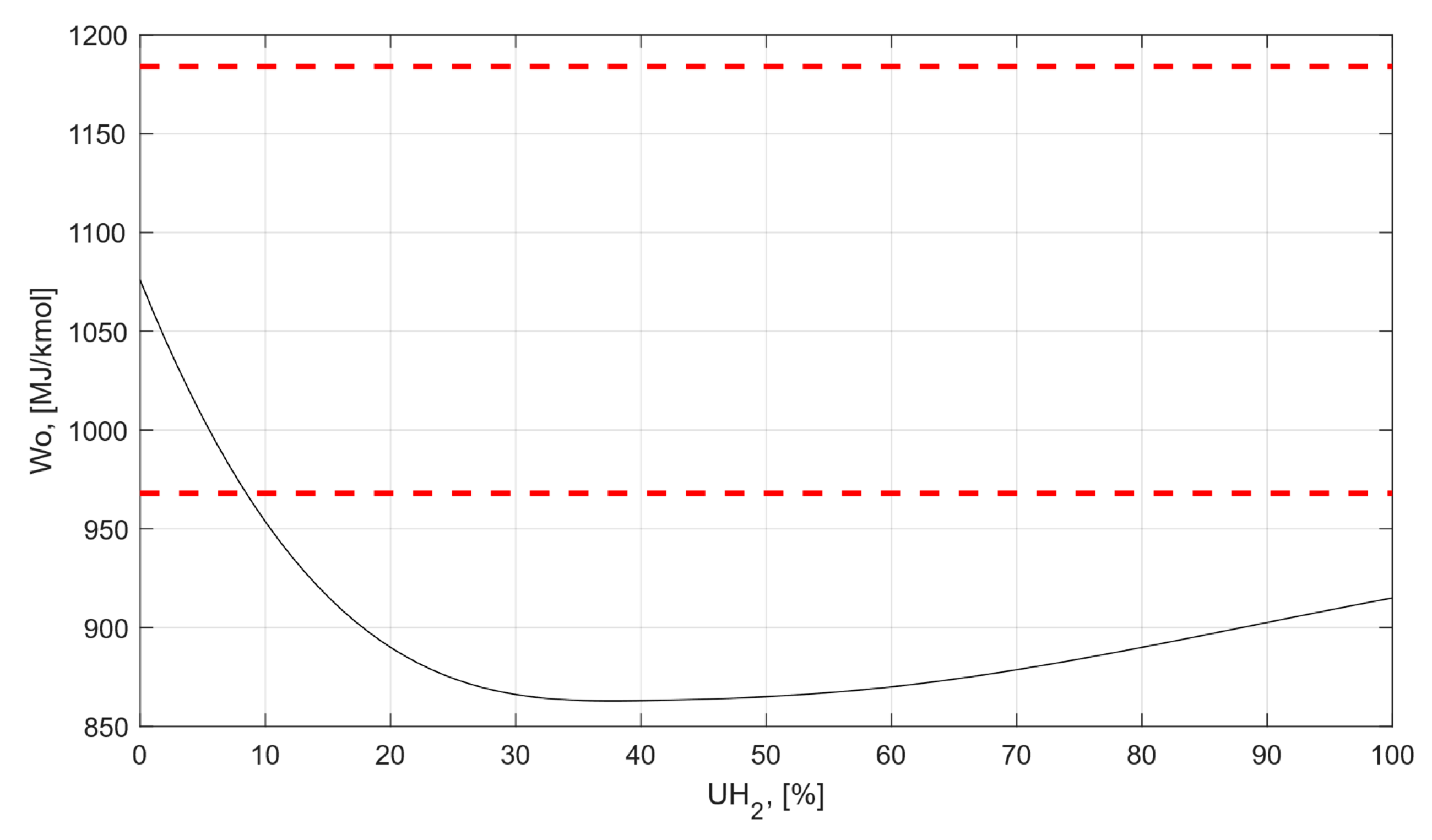

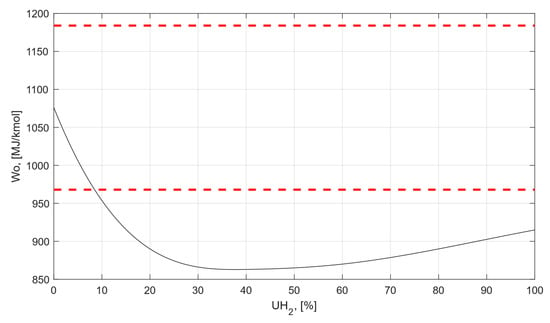

Additionally, the Wobby number was calculated, which is used by gas turbine manufacturers to standardize permissible design limits of the combustion chamber when blending different fuels with different calorific properties [32,55]. Figure 3 shows the relationship between the Wobby number value of the fuel is presented as a function of the hydrogen percentage in the fuel, allowing a direct assessment of the admissible hydrogen share for the considered combustion chamber.

Figure 3.

The dependence of the value of the Wobby number of the fuel as a function of the percentage of hydrogen in the fuel.

As shown in Figure 3, for fuels intended to be used in the same combustion system, the Wobbe number should not deviate by more than 10% from its nominal value. The upper and lower limits of the Wobby number are represented on Figure 3 by dashed lines, which are, respectively, 1184 MJ/kmol and 969 MJ/kmol. Based on the obtained graph, it can be concluded that the percentage of hydrogen in the fuel mixture can maximally reach about 7.6%. Beyond this value, the Wobbe number falls outside the acceptable range, implying that modifications or redesign of combustion chamber components would be required to ensure stable and safe operation.

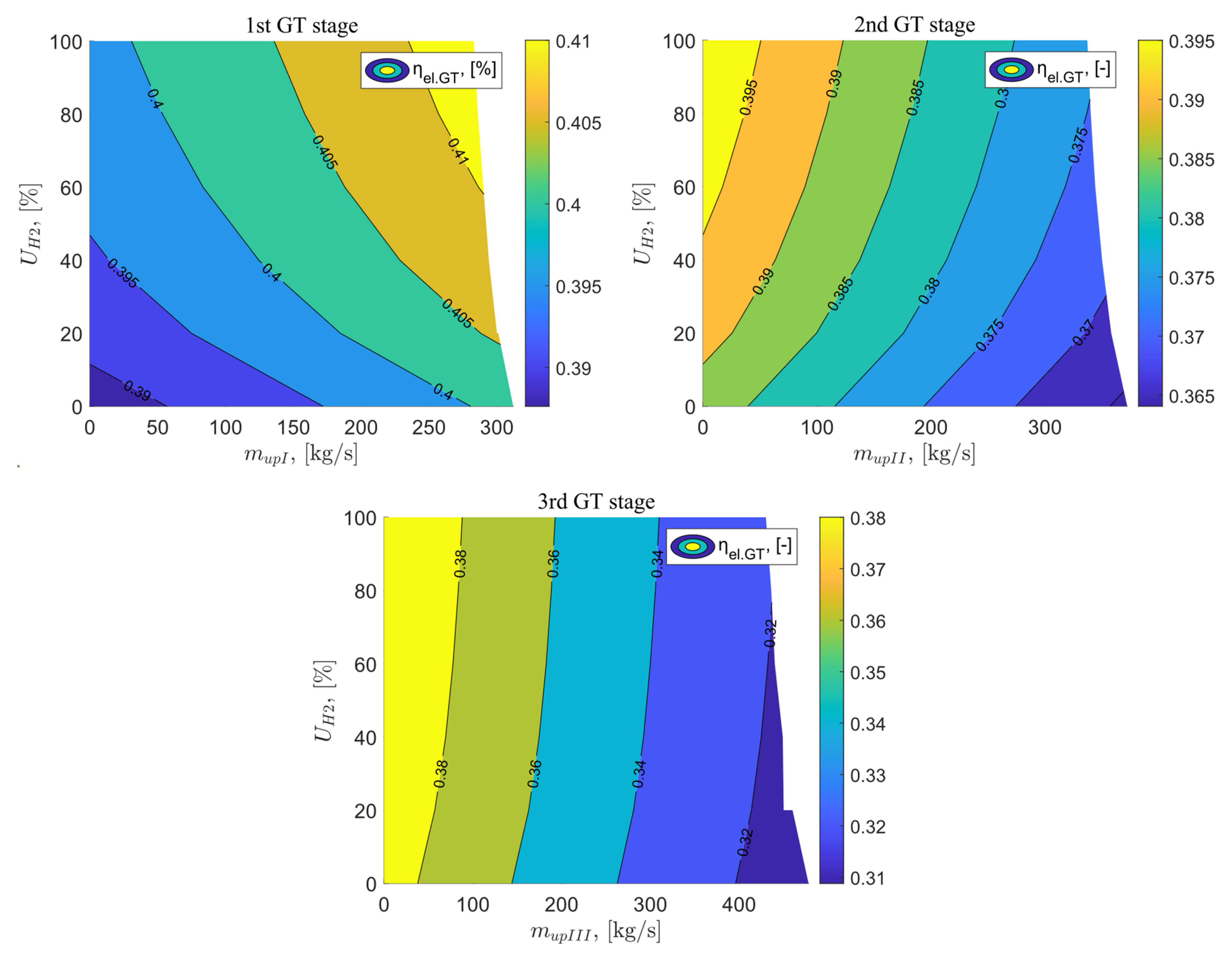

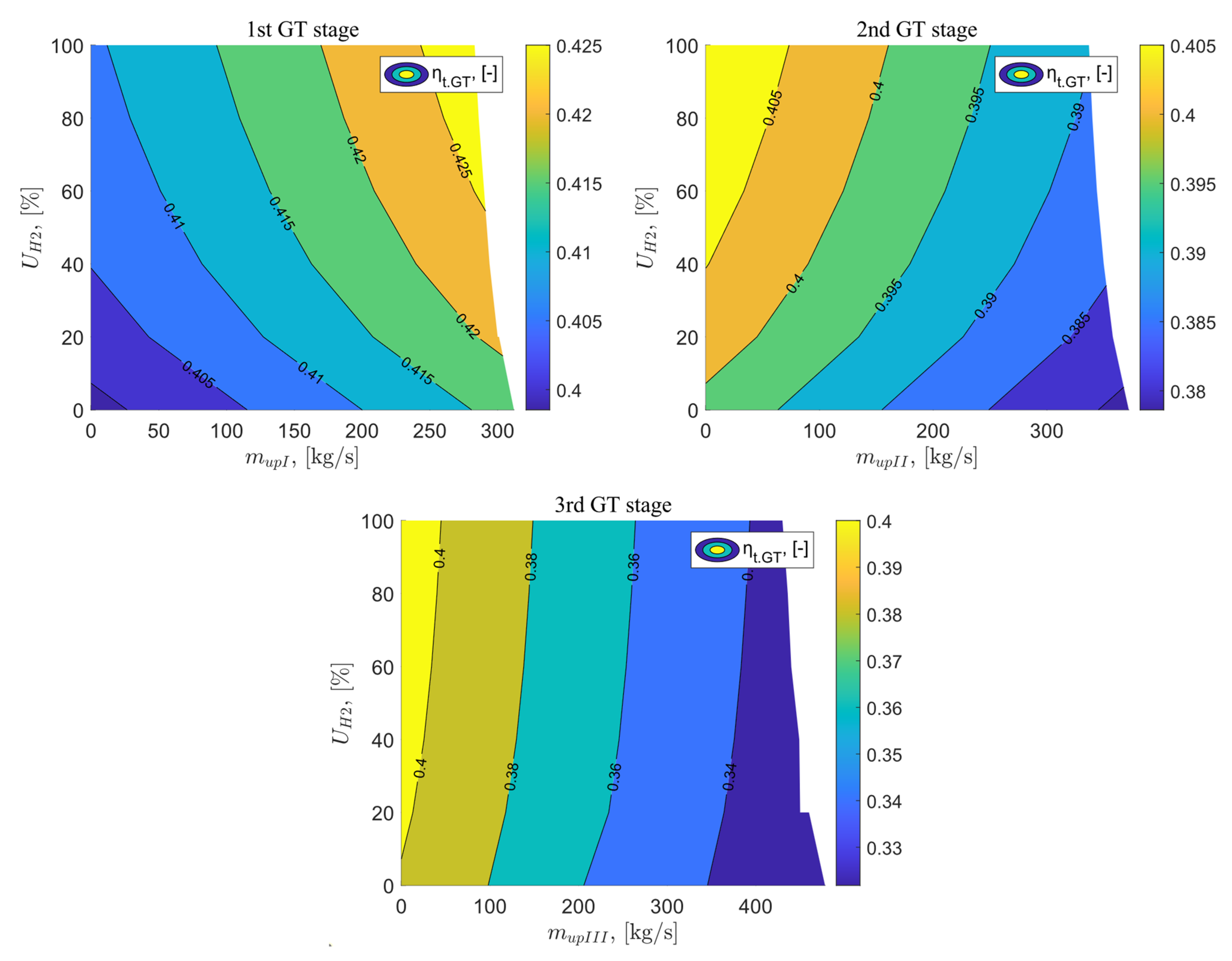

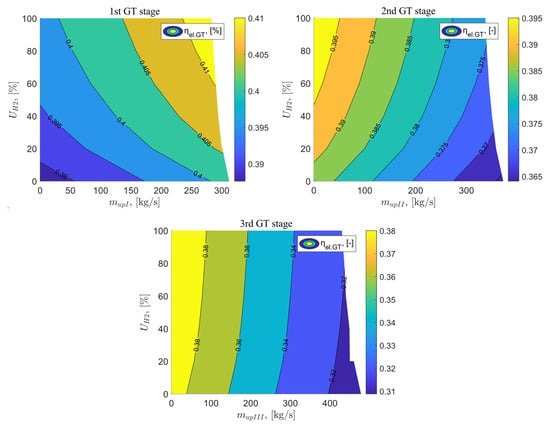

The first analyzed parameter was the electric efficiency of the gas turbine, denoted as . For the reference gas system according to Szewalski’s idea, the efficiency is 38.76%. Then, calculations were conducted successively for the exhaust of flue gases vented after the I, II, and III stages of the gas turbine, as well as for the increasing share of hydrogen in the fuel mixture ranging from 0–100%. For variant B, the electric efficiency of the gas turbine increases with the increasing exhaust of flue gases and the increasing percentage of hydrogen in the fuel, reaching the highest value of 41.25% for = 283 kg/s and = 100%. This represents an increase of 2.49 percentage points compared to the reference system. In the case of fuel combustion without the addition of hydrogen, and for the maximum value of exhaust after the I stage of the gas turbine, the efficiency achieved is 40.15%. For variant C, when the flue gases are exhaust after the II stage of the gas turbine, the opposite effect is observed compared to variant B. With the increasing exhaust of flue gases, the electric efficiency of the gas turbine decreases. Its increase occurs only with the increasing percentage of hydrogen in the fuel, reaching the highest value for = 0 kg/s and = 100% at 39.86%. This represents an increase in efficiency by 1.1 percentage points compared to variant A. For the last analyzed variant, when the exhaust vent of flue gases occurs after the III stage of the gas turbine, the electric efficiency of the gas turbine also decreases with the increasing exhaust vent of flue gases, and increases with the increasing percentage of hydrogen in the fuel mixture. The highest efficiency assumes the same value as for variant C. At maximum exhaust of flue gases and 100% hydrogen fuel, the efficiency is only 32.17%. This represents a significant regression compared to the reference variant. When exhaust gases are discharged after the first stage of the gas turbine, the turbine’s efficiency is relatively high and the exhaust gas temperature is increased compared to the reference variant. By releasing part of the exhaust gases at this point and directing them to heat exchangers, thermal energy can be effectively recovered by heating the inlet air to the compressor and combustion chamber. As a result, the overall efficiency of the gas system increases, as the loss of mechanical work in the first stage is partially compensated by improved heat recovery. On the other hand, when exhaust gases are released after the second and third stages of the gas turbine, they have already undergone significant expansion at this stage, resulting in lower temperature and pressure. Releasing exhaust gases at these points results in lower heat recovery, while at the same time causing a greater loss of mechanical work in the turbine, which leads to a decrease in cycle efficiency.

The results of the analysis for the electric efficiency of the gas turbine as a function of the exhaust vent after the I, II, and I stages of the gas turbine, as well as the percentage share of hydrogen in the fuel mixture are presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Gas turbine electrical efficiency as a function of vented flux downstream of the GT stages and the percentage of hydrogen in the fuel.

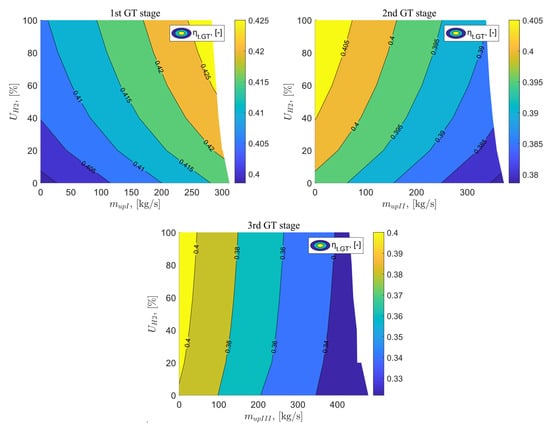

Figure 5, show the results of the analysis for the thermal efficiency of the gas turbine are presented as a function of the exhaust vent after the I, II, and III stages of the gas turbine, as well as the percentage share of hydrogen in the fuel mixture. The thermal efficiency of the gas turbine for the base variant is 0.399. After implementing the exhaust vent of gases after the I stage of the gas turbine, along with an increase in the exhaust gas flow and the percentage share of hydrogen in the fuel mixture, the thermal efficiency of the gas turbine increases. For the parameters = 283 kg/s and = 100%, it reaches the highest value of 0.428. Releasing the exhaust gas flow after the II and III stages of the gas turbine leads to a decrease in the thermal efficiency of the gas turbine. It increases only with the increase in the percentage of hydrogen in the fuel mixture for both cases. The highest thermal efficiency values of the gas turbine in variants C and D are achieved for an exhaust gas flow rate of 0 kg/s and a hydrogen content in the fuel of 100%, amounting to 0.409.

Figure 5.

Thermal efficiency of a gas turbine as a function of the exhaust flux downstream of the GT stages and the percentage of hydrogen in the fuel.

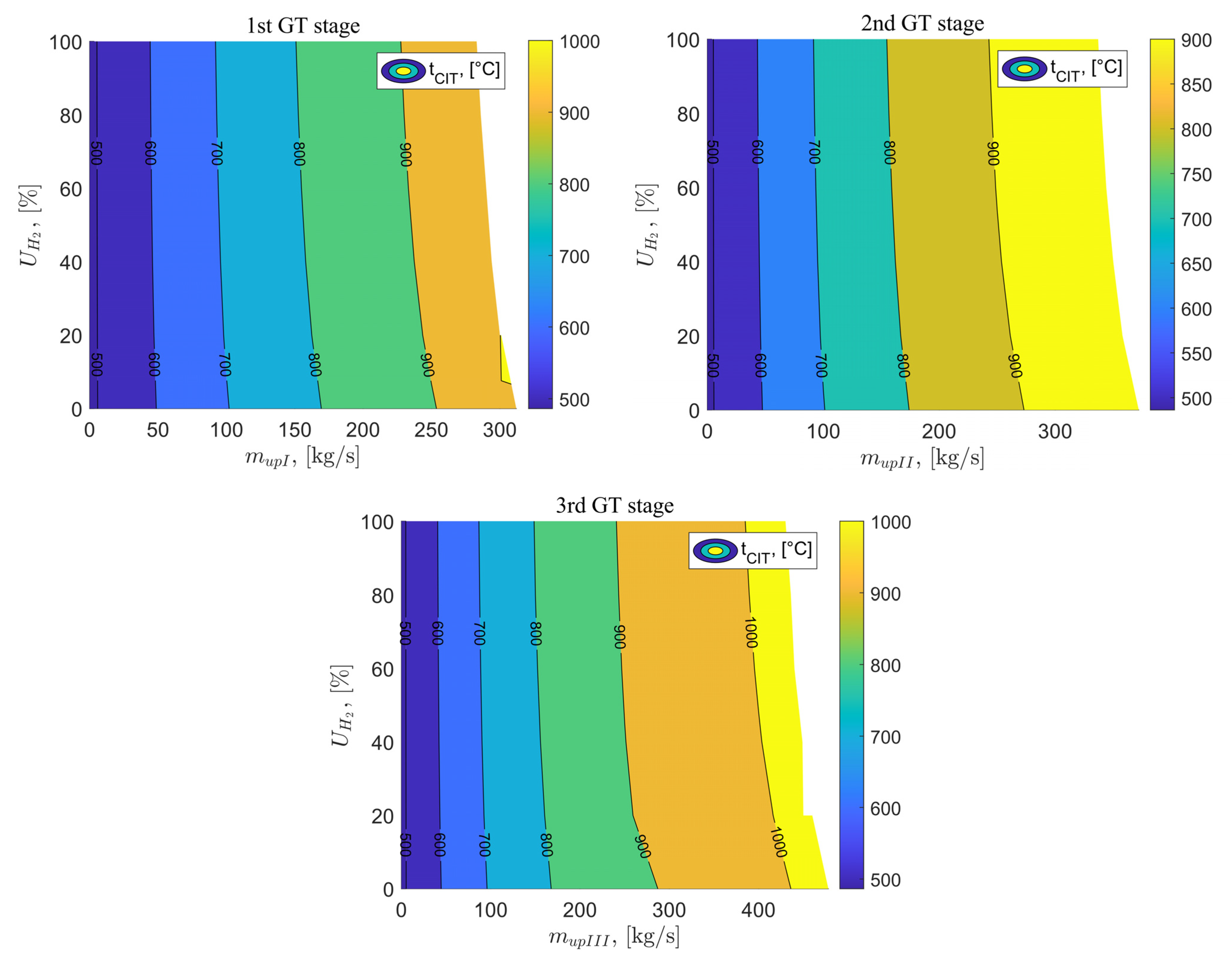

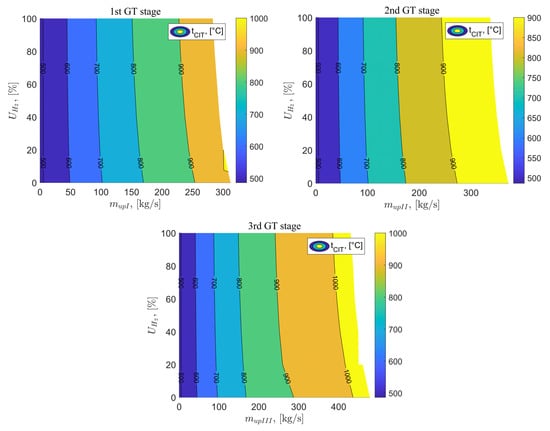

The next analyzed parameter is the temperature of the fluid at the inlet to the combustion chamber . The value of the temperature at the inlet to the combustion chamber (CIT) for the reference variant is 486.35 °C. After implementing the exhaust vent of gases after the I stage of the gas turbine and adding hydrogen in the appropriate percentage proportions to the fuel, this temperature increases. Its value increases significantly with the increase in the exhaust gas flow rate and slightly with the increase in the percentage share of hydrogen in the fuel mixture. The highest achieved temperature value is 1088.13 °C for = 301 kg/s and = 20%. For variant C and D, the CIT temperature values have the same trend as for variant B. The application of exhaust vent after the II stage of the gas turbine allowed for achieving a maximum temperature 977.17 °C for = 337 kg/s and = 100%. As a result of using exhaust vent after the III stage of the gas turbine, the highest possible temperature is 1023.43 °C and was achieved for an exhaust gas flow rate of 436 kg/s and a hydrogen percentage in the fuel mixture of 80%. Figure 6 shows the analysis results for the CIT temperature as a function of the exhaust flow rate after the I, II, and III stages of the gas turbine and the percentage of hydrogen in the fuel mixture.

Figure 6.

CIT temperature as a function of the vent stream downstream of the GT stages and the percentage of hydrogen in the fuel.

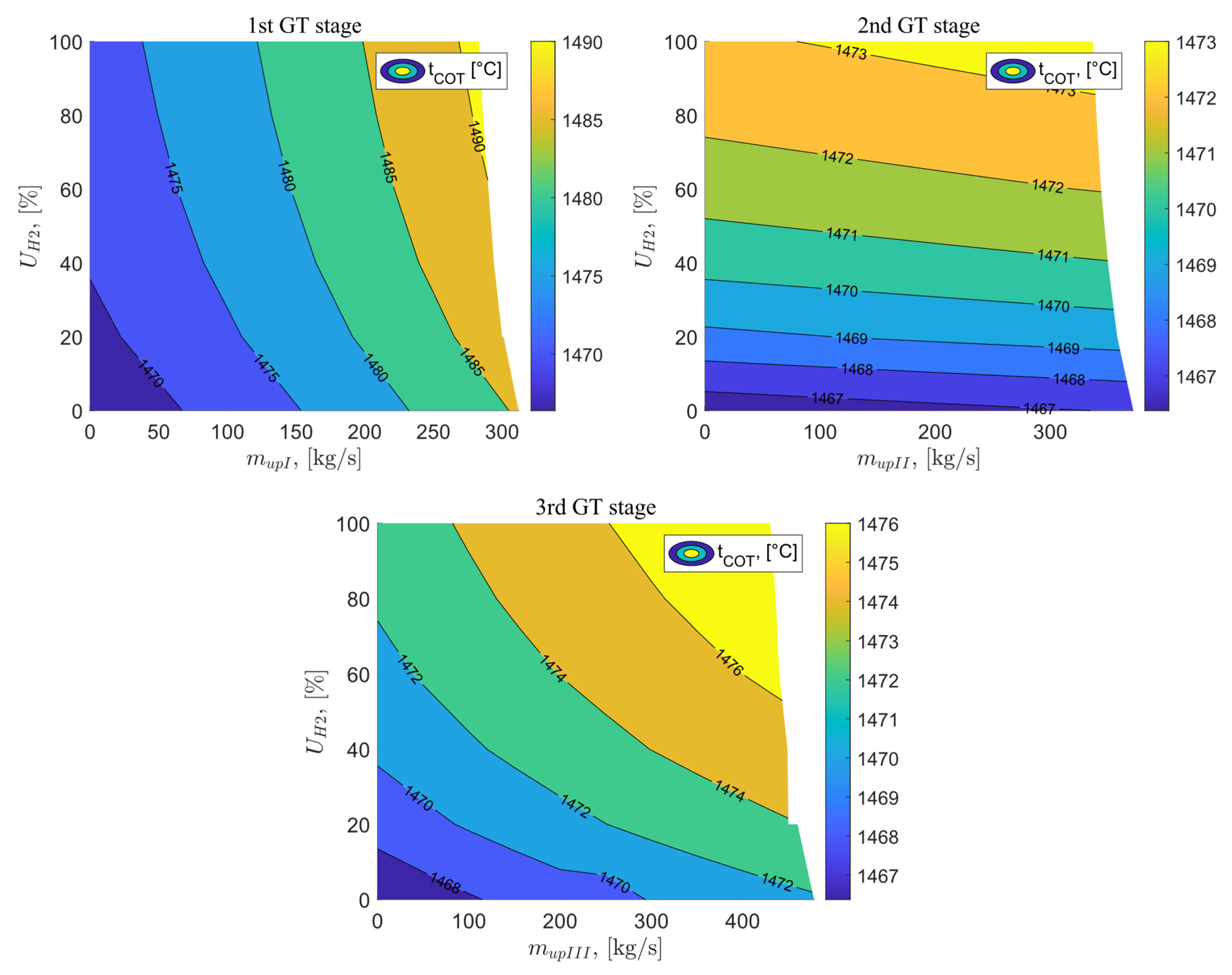

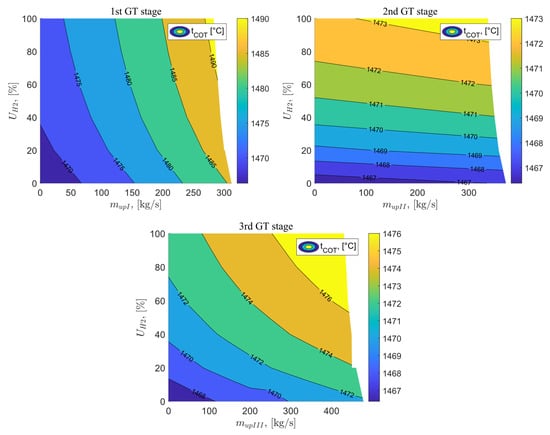

The next temperature examined was the Combustion Outlet Temperature . The COT temperature has a significant impact on the electrical efficiency achieved by the system. Generally, it is assumed that the higher the temperature at the turbine outlet, the higher the efficiency. Current systems achieve a maximum COT temperature of around 1600 °C, ensuring the safety of the materials used. Figure 7 shows the analysis results for the COT temperature as a function of the exhaust vent after the I, II, and III stages of the gas turbine and the percentage of hydrogen in the fuel mixture. The reference value of the COT temperature is 1466.38 °C, and the application of exhaust vent after the I, II, and III stages of the gas turbine allowed for a maximum increase in this temperature to 1491.08 °C, 1473.44 °C, and 1477.62 °C, respectively. All these values were obtained for the maximum possible exhaust vent for each stage of the gas turbine and for 100% hydrogen fuel. The highest increase in temperature compared to the reference variant is observed in variant B, reaching 24.7 °C. It can be noticed that the change in exhaust flow rates has the greatest impact on the COT temperature in variant B and slightly less significant in variant D. When applying exhaust vent after the II stage of the gas turbine, it has a negligible effect on the temperature of the fluid after the combustion chamber. The main influence in the case of variant C is the percentage share of hydrogen in the fuel mixture.

Figure 7.

COT temperature as a function of the vent stream downstream of the GT stages and the percentage of hydrogen in the fuel.

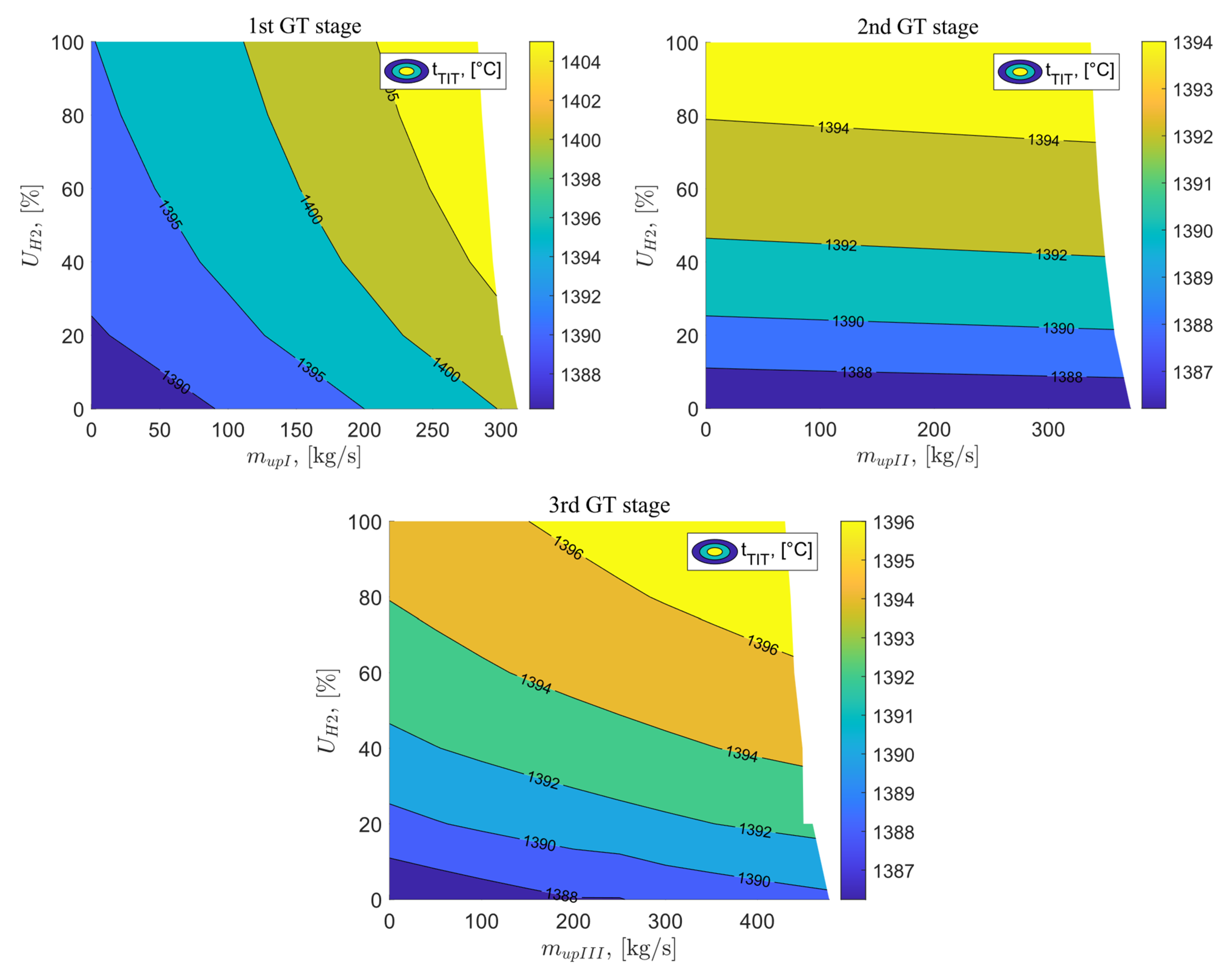

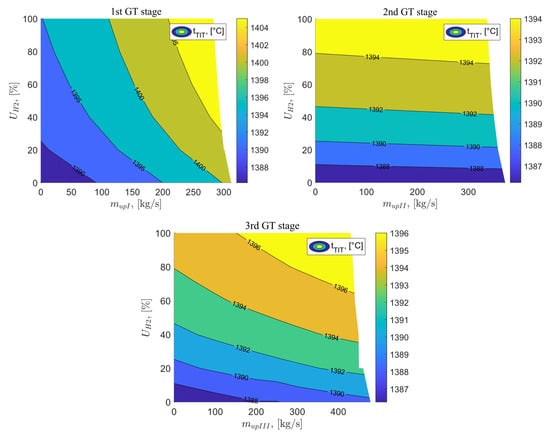

The distribution of TIT temperature for systems where exhaust is applied after the I, II, and III stages of the gas turbine exhibits a very similar pattern to the TIT temperature. These temperatures are correspondingly lower than the temperatures of the fluid behind the combustion chamber, and they are 1409.21 °C, 1395.2 °C, and 1397.52 °C, respectively, for maximum exhaust after the first, second, and third stages of the gas turbine and with the use of 100% hydrogen fuel. For the reference variant, the TIT temperature value is 1386.22 °C, slightly lower compared to variants B, C, and D. Figure 8 shows the analysis results for the TIT temperature as a function of exhaust vent flow after the I, II, and III stages of the gas turbine and the percentage share of hydrogen in the fuel mixture.

Figure 8.

TIT temperature as a function of the vent stream downstream of the GT stages and the percentage of hydrogen in the fuel.

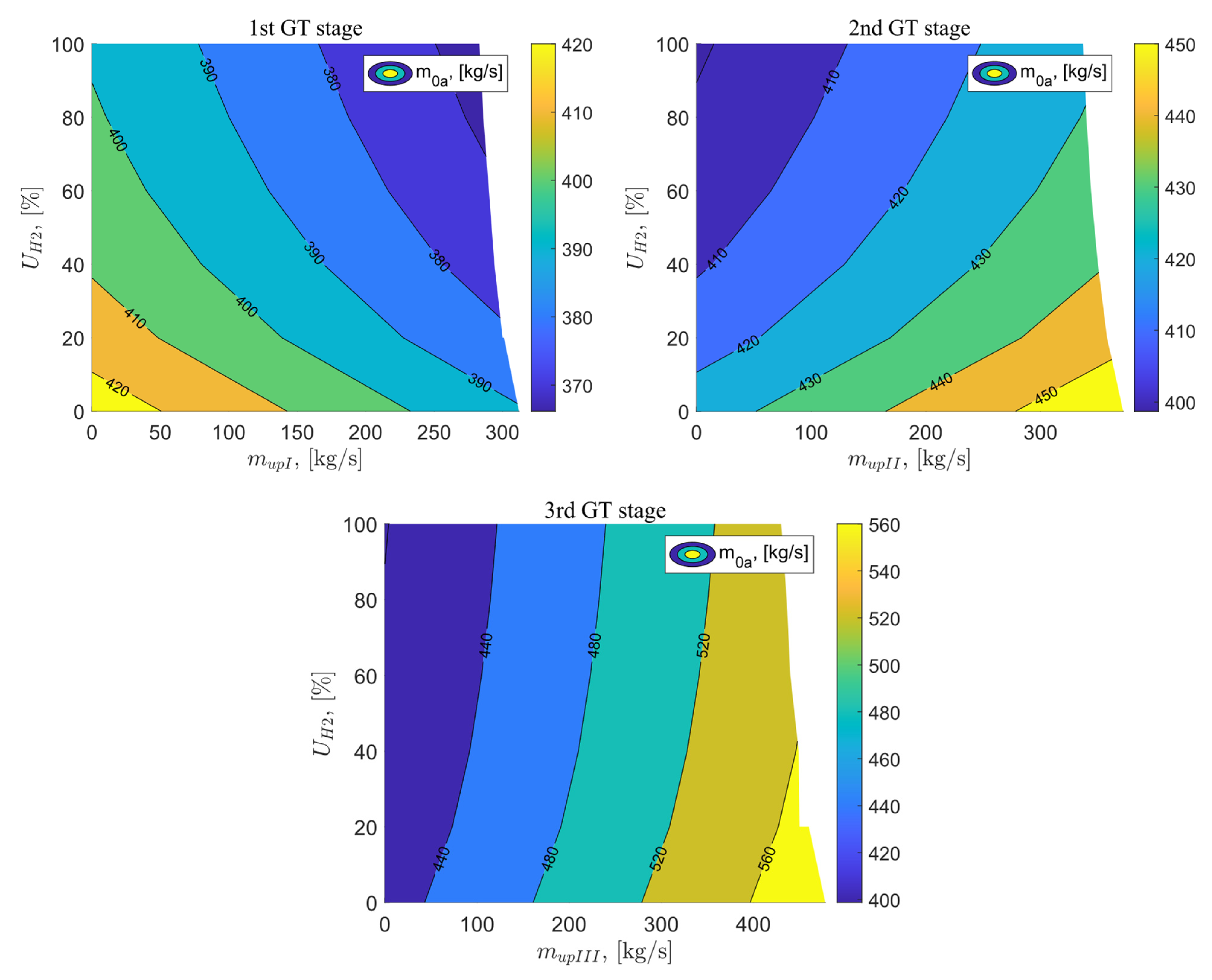

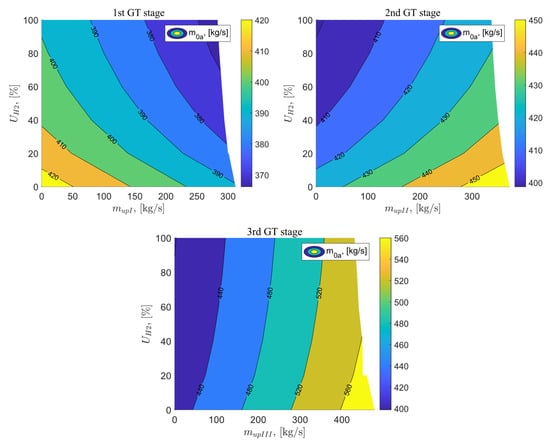

The values of the airflow brought into the gas turbine system in relation to the exhaust vent flow at the I, II, and III stages of the gas turbine, as well as the percentage share of hydrogen in the fuel mixture, are presented in Figure 9. The mass flow rate of air entering the system is 425.41 kg/s. For variant B, where the exhaust gases were vented after the first stage of the gas turbine, the airflow value for the reference system parameters ( = 0 kg/s and = 0%) is the highest. As the exhaust flow and the percentage share of hydrogen in the fuel mixture increase, the airflow supplied into the system decreases. The minimum value of this airflow is reached for = 283 kg/s and = 100% and it amounts to 366.18 kg/s. For the exhaust vent after the II stage of the gas turbine, as the exhaust flow increases, the value of the airflow supplied to the system increases, while it decreases with the increasing percentage share of hydrogen in the fuel. The highest value is achieved for = 372 kg/s and = 0% which is equal to 458.32 kg/s. In the last analyzed variant, the value of the inlet airflow to the gas turbine also increases with the increasing exhaust vent flow and decreases when hydrogen is added to the fuel mixture. In variant D, the influence of the percentage share of hydrogen on the airflow s significantly smaller than for variant C. In the case of exhaust vent of the exhaust gas flow after the III stage of the gas turbine, the maximum value of the mass airflow of the air supplied to the gas turbine is 544.39 kg/s.

Figure 9.

Air flow supplied to the GT circuit as a function of the bleed flow after the GT stages and the percentage of hydrogen in the fuel.

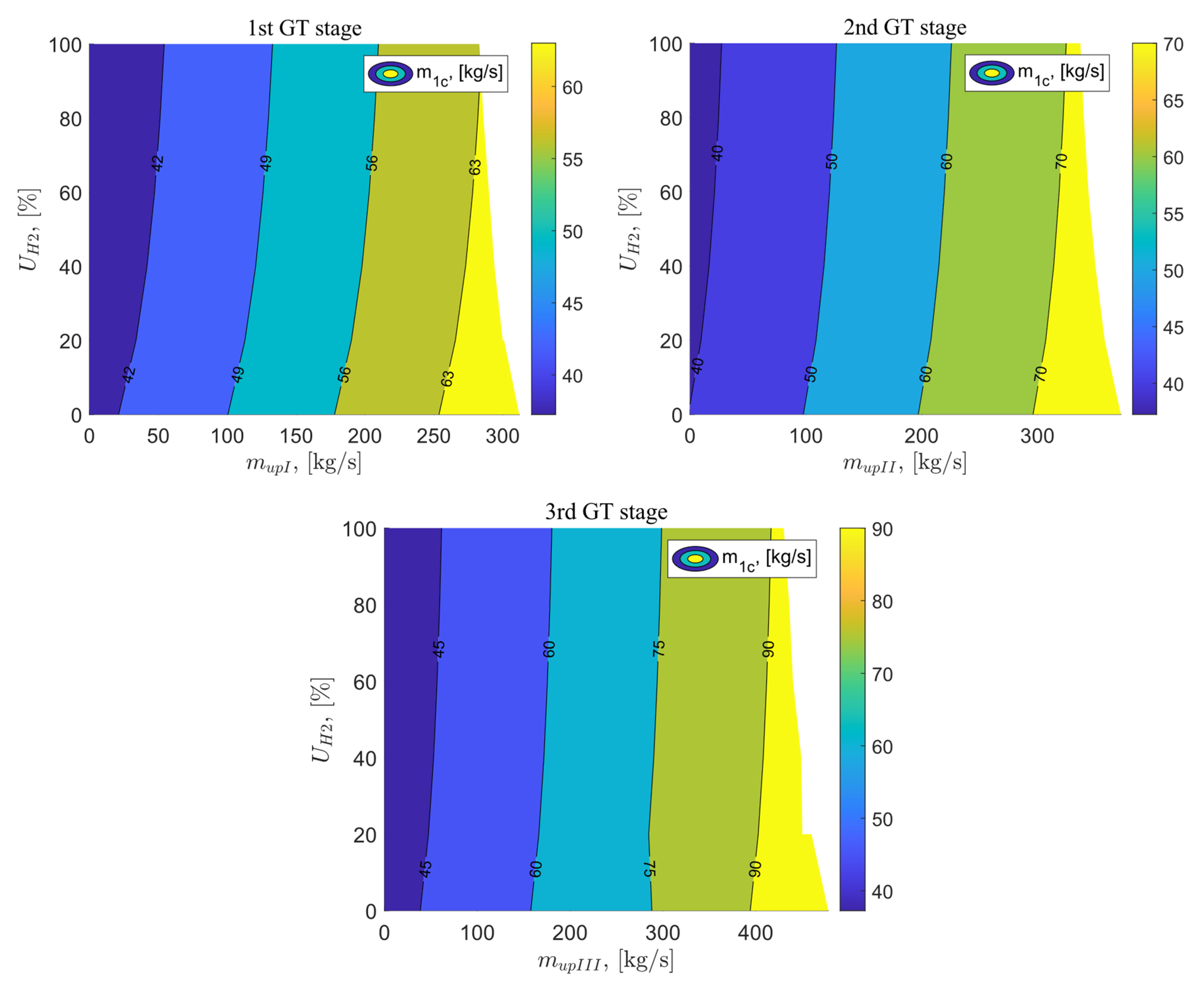

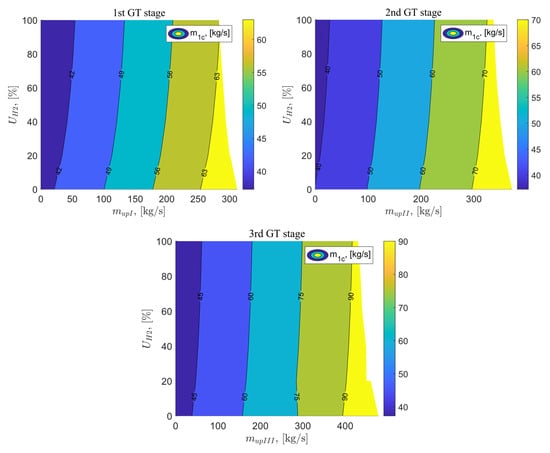

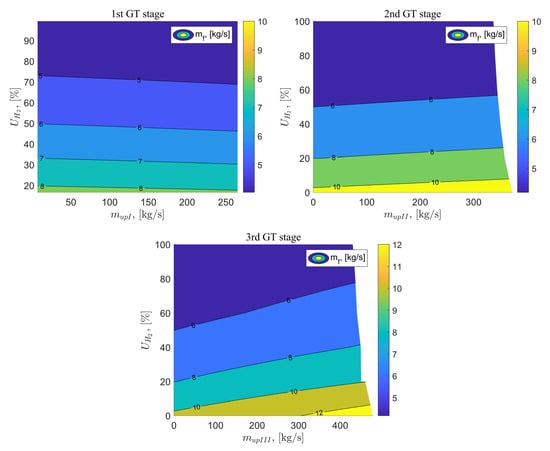

The next analyzed parameter is the airflow cooling the gas turbine blade . For the reference variant, this value is 40.15 kg/s, and in all variants where exhaus gases vent are applied, this value increases with the increasing exhaust gas flow and the percentage share of hydrogen in the fuel mixture. For variant B, the maximum cooling airflow is 68.51 kg/s for an exhaust gas flow of 312 kg/s and for fuel consisting of 100% methane. For variants C and D, the maximum values of cooling airflow are 77.6 kg/s and 100.72 kg/s, respectively, for the maximum achieved exhaust gas flow and fuel with 100% methane content. Figure 10 illustrates the results of the analysis for the cooling airflow as a function of the exhaust gas vent behind the I, II, and III stages of the gas turbine, as well as the percentage share of hydrogen in the fuel mixture.

Figure 10.

Cooling air flux as a function of the flux vented after the 1st GT stage and the percentage of hydrogen in the fuel.

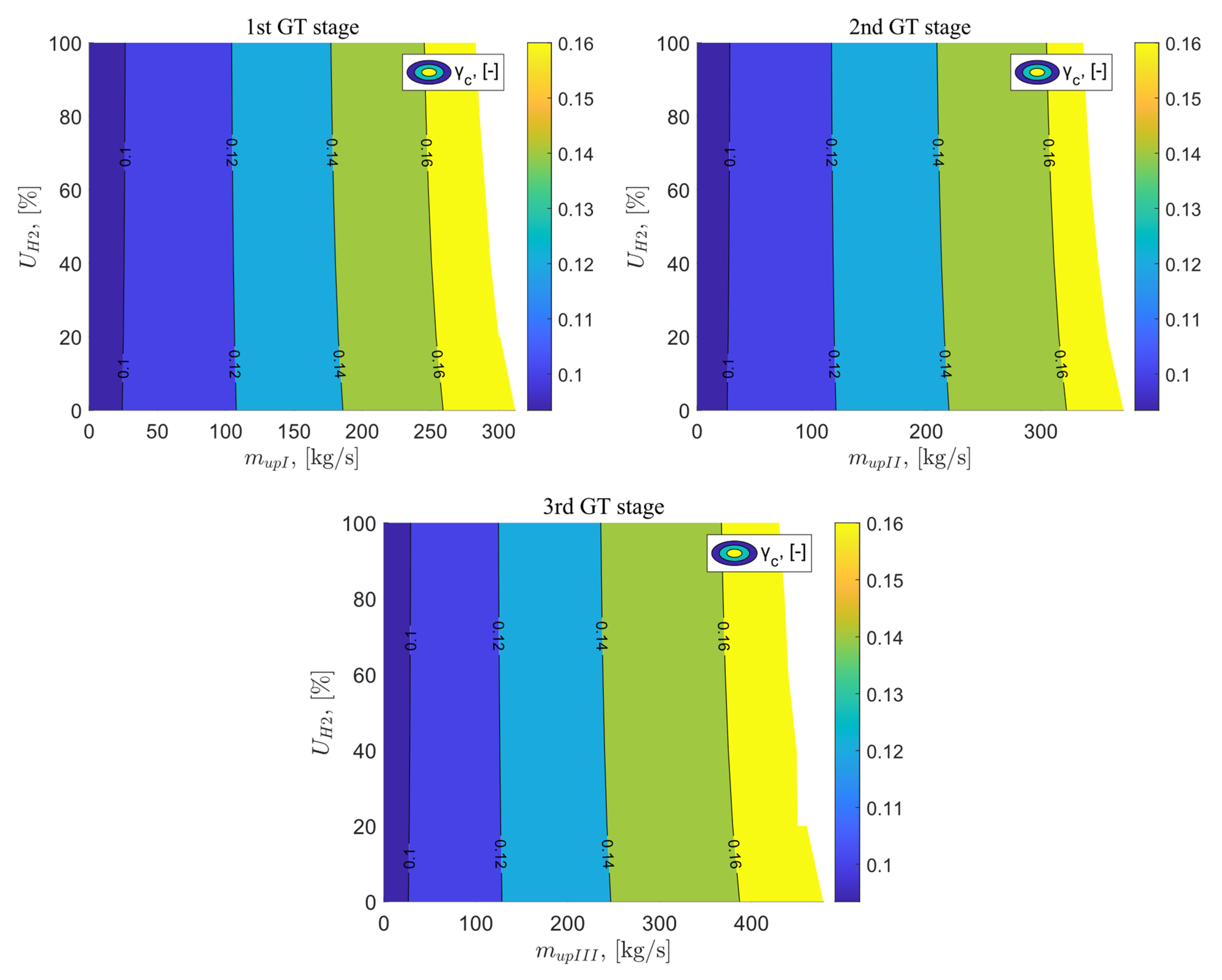

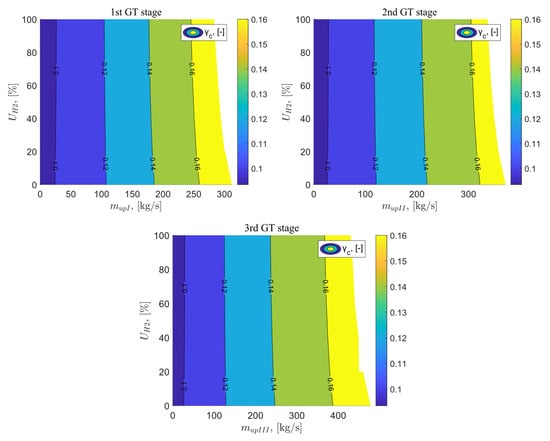

Figure 11 illustrates the results of the analysis for the cooling ratio as a function of the exhaust gas vent behind the I, II, and III stages of the gas turbine, as well as the percentage share of hydrogen in the fuel mixture. The cooling airflow ratio represents the ratio of the mass flow rate of the cooling air to the mass flow rate of the air entering the gas turbine cycle. Its value for the baseline system is 0.09. For all analyzed variants where exhaust gas vented the gas turbine were applied, it can be observed that only changes in the exhaust gas flow have an impact on the cooling ratio value. The lines on the graph are vertical, indicating that changes in the percentage share of hydrogen in the fuel mixture have a negligible effect on the analyzed parameter. The highest cooling ratio value for variant B reaches 0.175 for the following parameters = 312 kg/s and = 0%. Due to the fact that the hydrogen content in the fuel mixture has negligible significance for the cooling ratio value, and the highest flow can be obtained when the fuel burned is 100% methane, the highest cooling ratio value occurs for these values. Similarly, when the exhaust gas vented is located after the II and III stages of the gas turbine, the highest cooling ratio values are obtained for these vented, reaching 0.169 and 0.171, respectively.

Figure 11.

Cooling air ratio as a function of venting flux downstream of the GT stages and the percentage of hydrogen in the fuel.

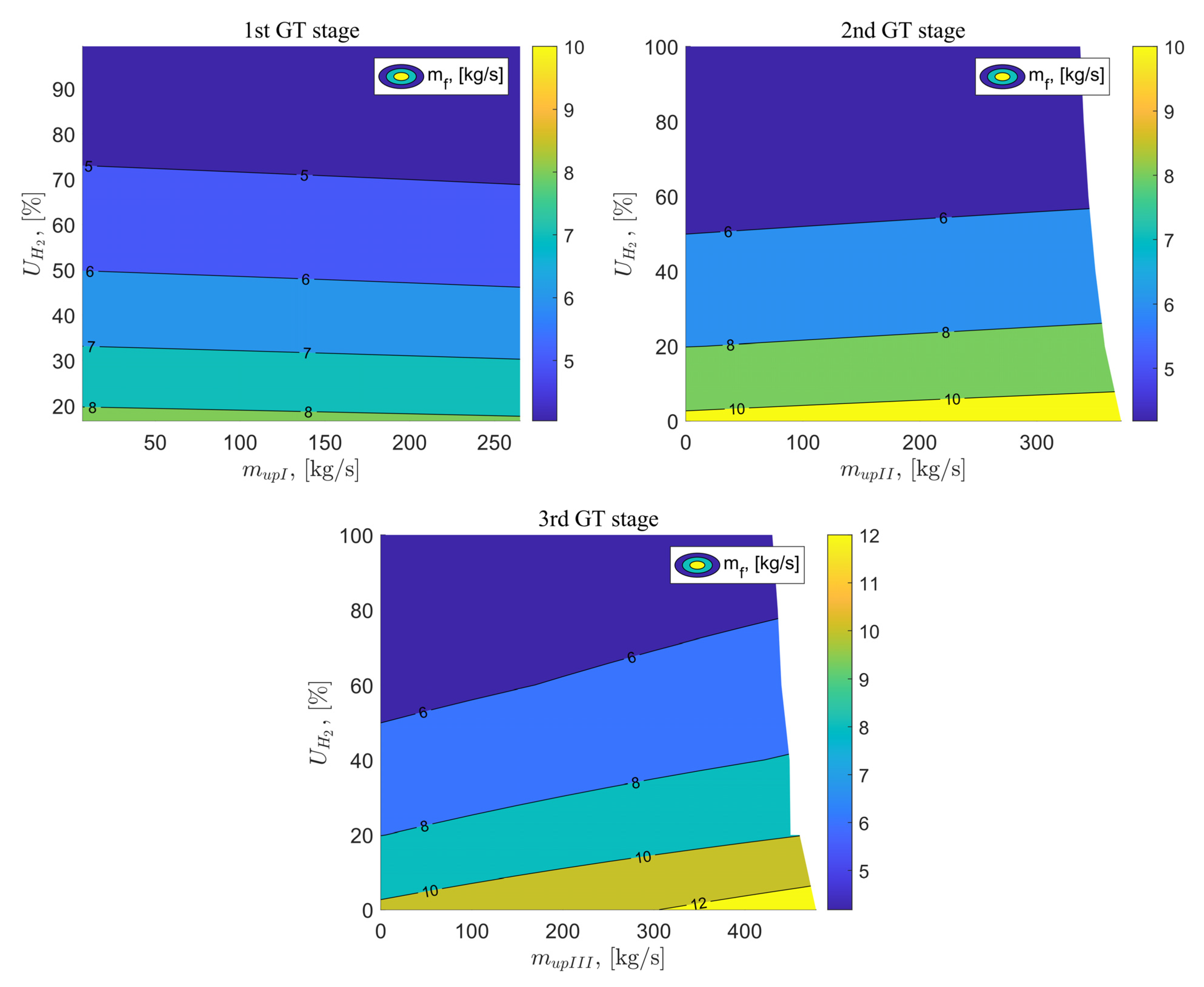

In Figure 12, the analysis results for the fuel flow rate supplied to the combustion chamber are presented as a function of the exhaust gas vented at the I, II, and III stages of the gas turbine, as well as the percentage of hydrogen in the fuel mixture. In the reference scenario, the fuel supplied is 100% methane, with a flow rate of 10.32 kg/s. In scenario B, the application of exhaust gas vented ranging from 0 to the maximum possible flow has a negligible effect on the fuel flow rate supplied to the combustion chamber. These values decrease slightly. For example, for a hydrogen percentage in the fuel mixture of 80% and = 0 kg/s, the fuel flow rate reaches 4.75 kg/s, while for = 286 kg/s, the fuel flow rate decreases to 4.59 kg/s. Large changes can be observed when increasing the percentage of hydrogen in the fuel mixture. For = 283 kg/s and = 100%, the supplied fuel flow rate decreases by 6.28 kg/s, reaching a value of 4.04 kg/s. For variants C and D, the percentage of hydrogen in the fuel mixture also has the greatest impact on the value of the fuel flow rate supplied to the combustion chamber. In the case of exhaust gas vent behind the II stage of the gas turbine, the fuel flow rate increases slightly with the increasing exhaust flow rate. The smallest fuel flow rate can be achieved for = 100% and = 0 kg/s, equal to 4.18 kg/s. For the last of the exhausts gas vent, a greater influence of the exhaust gas flow rate that is vented on the mass flow rate of fuel supplied to the combustion chamber can be observed compared to variants B and C. As the exhaust flow rate increases also increases. For a hydrogen percentage in the fuel mixture equal to 60% and = 0 kg/s, the fuel flow rate reaches a value of 5.49 kg/s, while for = 440 kg/s, the fuel flow rate decreases to 6.82 kg/s. This is due to the much larger range of exhaust vent rate values for the exhaust vent behind the III stage of the gas turbine. The smallest value of the fuel flow rate supplied to the system for variant D is the same as for variant C for the reference system parameters.

Figure 12.

Fuel flux delivered to the combustion chamber as a function of the flux vented after the GT stages and the percentage of hydrogen in the fuel.

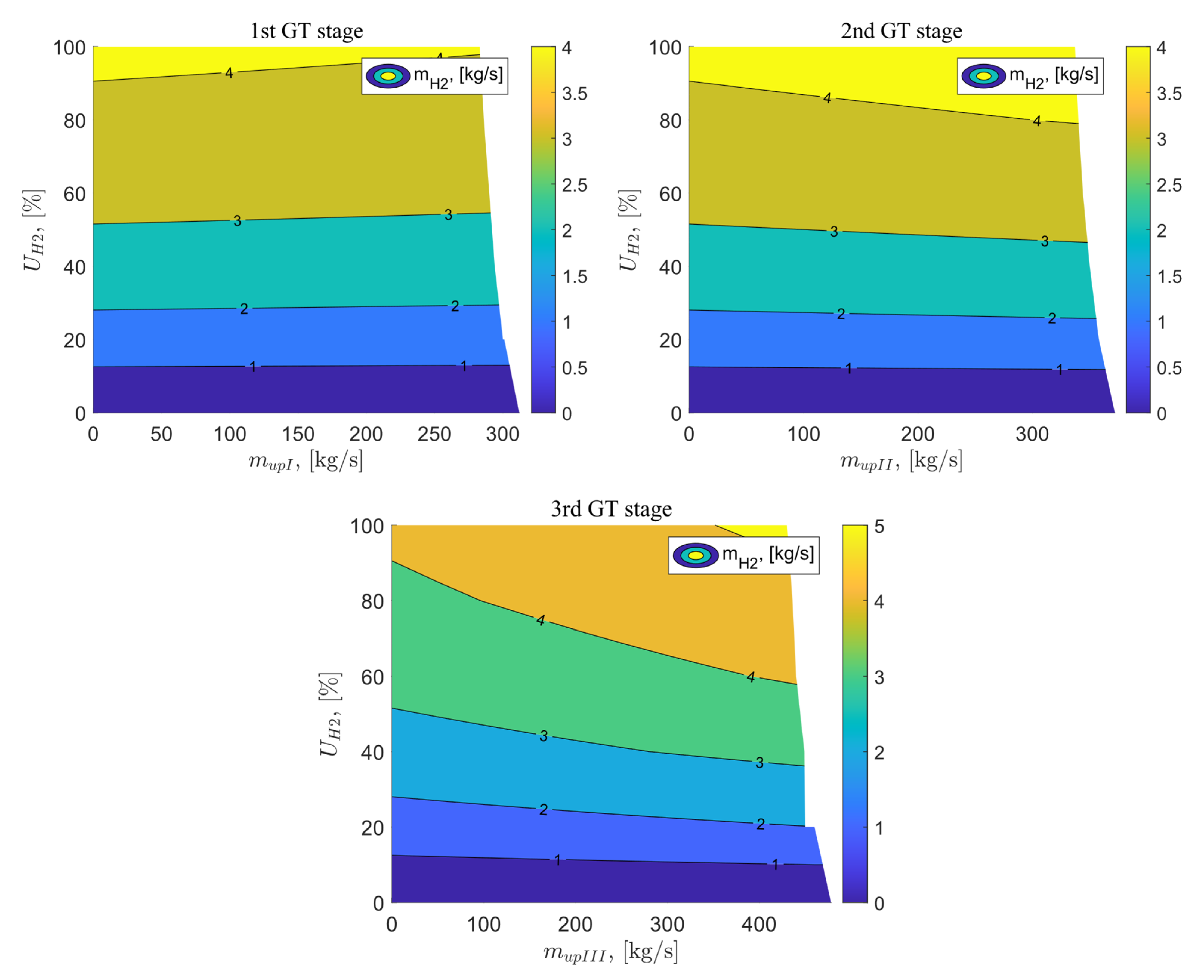

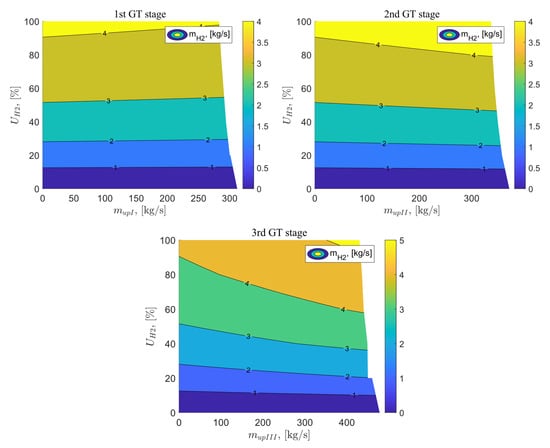

Figure 13 illustrates the results of the analysis of the flux of hydrogen fuel delivered to the combustion chamber as a function of the exhaust gas vented at the I, II, and III stages of the gas turbine, as well as the percentage of hydrogen in the fuel mixture. In the reference system, when the fuel burned is 100% methane, the hydrogen flux is 0 kg/s. When the flue gas vent is applied after the I stage of the gas turbine and hydrogen is added in appropriate percentages, the hydrogen fuel flux increases. Exhaust gas venting flux has a negligible effect on hydrogen fuel flux, with the pattern of vented exhaust gas flux, the value of hydrogen fuel flux slightly decreases. The highest flux was achieved for the parameters = 0 kg/s and = 100%, it reaches a value 4.18 kg/s. The use of exhaust venting after the II stage of the gas turbine also slightly affects the value of the hydrogen flux delivered to the combustion chamber. This value increases mainly with an increase in the percentage of hydrogen in the fuel reaching the highest flux for parameters = 337 kg/s and = 100%, it reaches value 4.43 kg/s. In contrast to Variant B, Variant C shows a slight increase in the hydrogen flux value with an increase in the exhaust gas stream vented downstream of the gas turbine. With an increase in the percentage of hydrogen in the fuel mixture and with an increase in the exhaust gas stream vented after the third stage of the gas turbine, the value of the hydrogen stream increases. The highest flux achieved has a value of 5.18 kg/s and was obtained for the parameters = 430 kg/s and = 100%.

Figure 13.

The flux of hydrogen fuel delivered to the combustion chamber as a function of the flux vented after the GT stages and the percentage of hydrogen in the fuel.

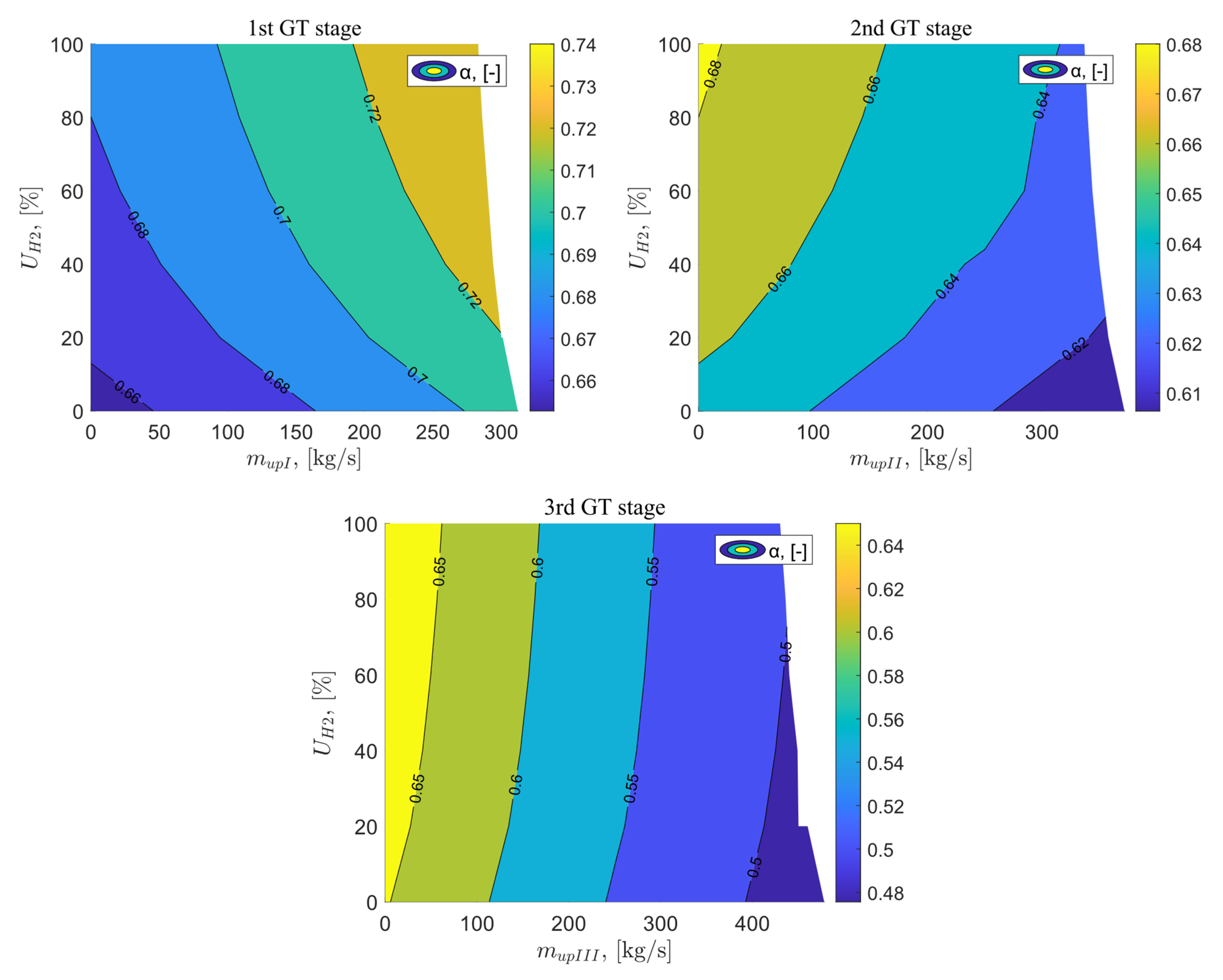

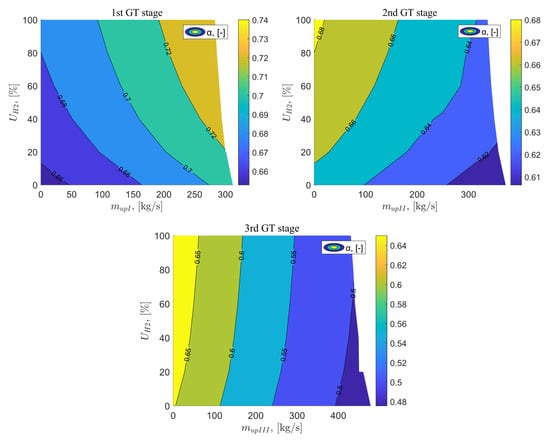

The energy flux ratio of the exhaust gas leaving the gas turbine α is the ratio of the electric power of the gas turbine to the heat flow exiting the gas turbine. The value of this ratio for the reference system is 0.65. For variant B, the energy flux ratio of the exhaust gas leaving the gas turbine increases with the increasing flue gas discharge flow and the increasing percentage share of hydrogen in the fuel mixture. For parameters = 100% and = 283 kg/s, it reaches a value of 0.74. In the case of the next two variants, the ratio of energy flux of the exhaust gas leaving the gas turbine decreases with the increasing flue gas flow vented behind the II and III stages of the gas turbine. For variant C, the percentage share of hydrogen in the fuel mixture has a much greater impact on the value of the Energy flux ratio of the exhaust gas than in variant D, both variants C and D, the highest value of α = 0.68, equal to 0.68, can be achieved for parameters = 100% and = 0 kg/s. The lowest value of α for variants C and D is 0.61 and 0.48, respectively, for = 100% and flue gas discharge flows = 372 kg/s and = 478 kg/s. The graph analyzing the energy flux ratio of the exhaust gas leaving the gas turbine as a function of the exhaust gas vented at the I, II, and III stages of the gas turbine and the percentage share of hydrogen in the fuel mixture is presented in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

Energy flux ratio of the exhaust gas leaving the TG as a function of the flux vented downstream of the GT stages and the percentage of hydrogen in the fuel.

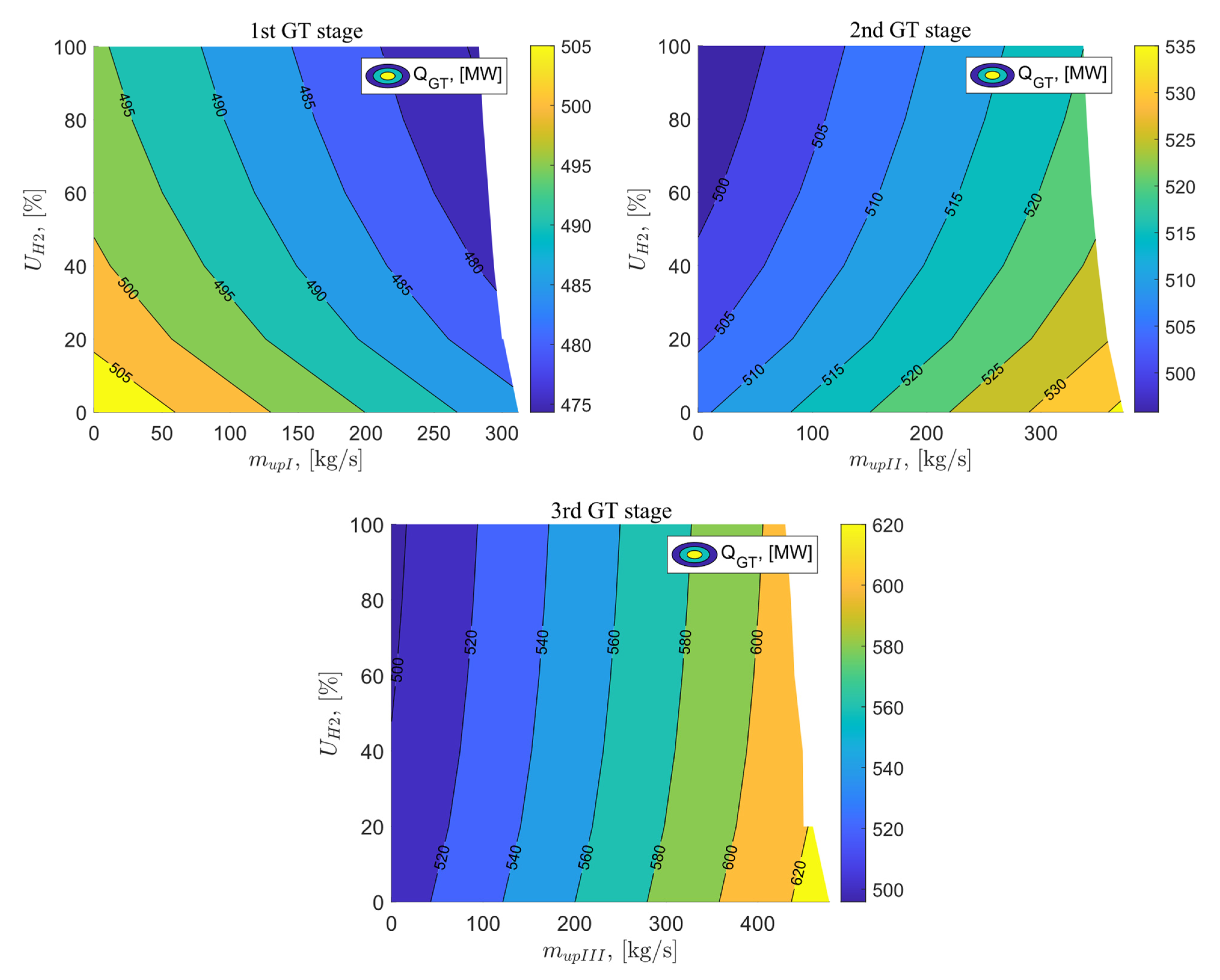

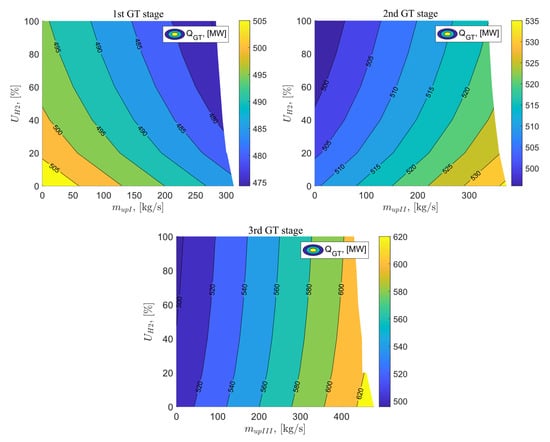

The next analyzed parameter was the heat flow supplied to the gas turbine as a function of the exhaust gas vented at the I, II, and III stages of the gas turbine and the percentage share of hydrogen in the fuel mixture, and its characteristics are presented in Figure 15. The value of the heat flow supplied to the gas turbine in the reference gas system is 509.17 MW. Increasing the exhaust gas flow vented behind the I stage of the gas turbine and increasing the percentage share of hydrogen in the fuel mixture reduces the heat flow supplied to the gas turbine to a value of 474.22 MW for parameters = 100% and = 283 kg/s. Applying flue gas vent behind the II stage of the gas turbine increases the heat flow supplied to the gas turbine, while the addition of hydrogen fuel from 0–100% contributes to its decrease. The minimum value of for variant C is 497.8 MW for = 100% and = 0 kg/s. For variant D, the heat flow supplied to the gas turbine also decreases with increasing flue gas vent flow and increases with the increasing share of hydrogen in the fuel mixture. This increase is much less noticeable than in variant C. The minimum achievable value of is the same as in the variant where flue gas vent behind the II stage of the gas turbine was applied.

Figure 15.

Heat flux supplied to the gas turbine as a function of the flux vented downstream of the GT stages and the percentage of hydrogen in the fuel.

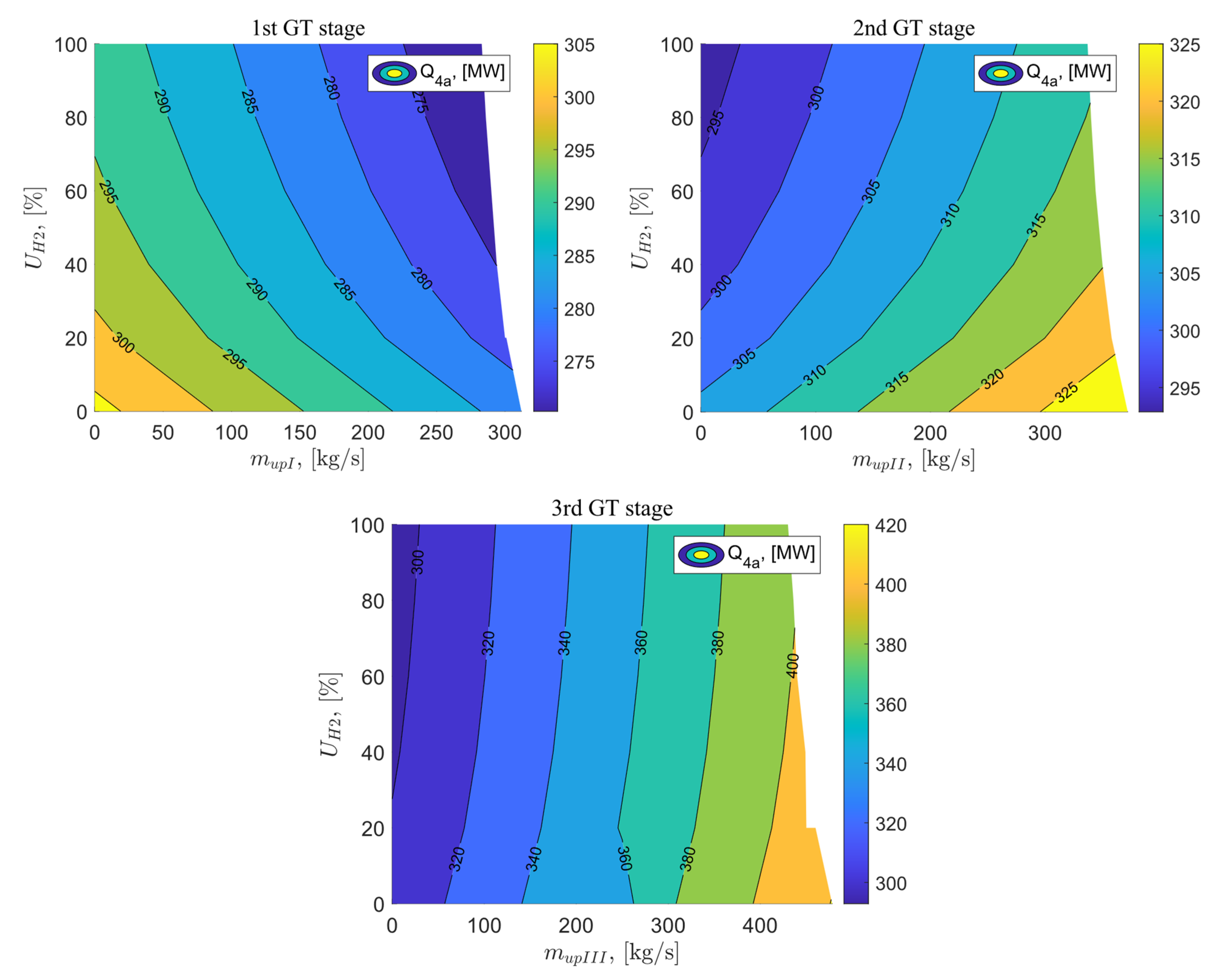

The next parameter analyzed is the heat flow of exhaust gases released to the environment with a value of 306.39 MW for the baseline system. Venting the exhaust gases after the first stage of the gas turbine and increasing the percentage of hydrogen in the fuel leads to a decrease in the heat flow of exhaust gases realised to the environment. For parameters = 100% and = 283 kg/s the system achieves the minimum value of , equal to 270.27 MW. Venting the exhaust gas stream after the II and III stages of the gas turbine results in an increase in the heat flow of exhaust gases in both cases. ncreasing the percentage of hydrogen in the fuel mixture for variant C leads to a decrease in the value of , with the minimum achieved heat flow of exhaust gases being 495.8 MW for parameters = 100% and = 0 kg/s. In variant D, with an increase in the percentage of hydrogen in the fuel , slightly increases, reaching the same minimum value as in variant C. Figure 16 presents the analysis results for the heat flow of exhaust gases released to the environment as a function of the exhaust gas vented at the I, II, and III stages of the gas turbine, as well as the percentage of hydrogen in the fuel mixture.

Figure 16.

Heat flux of flue gases given off to the environment as a function of the flux vented downstream of the 2nd GT stage and the percentage of hydrogen in the fuel.

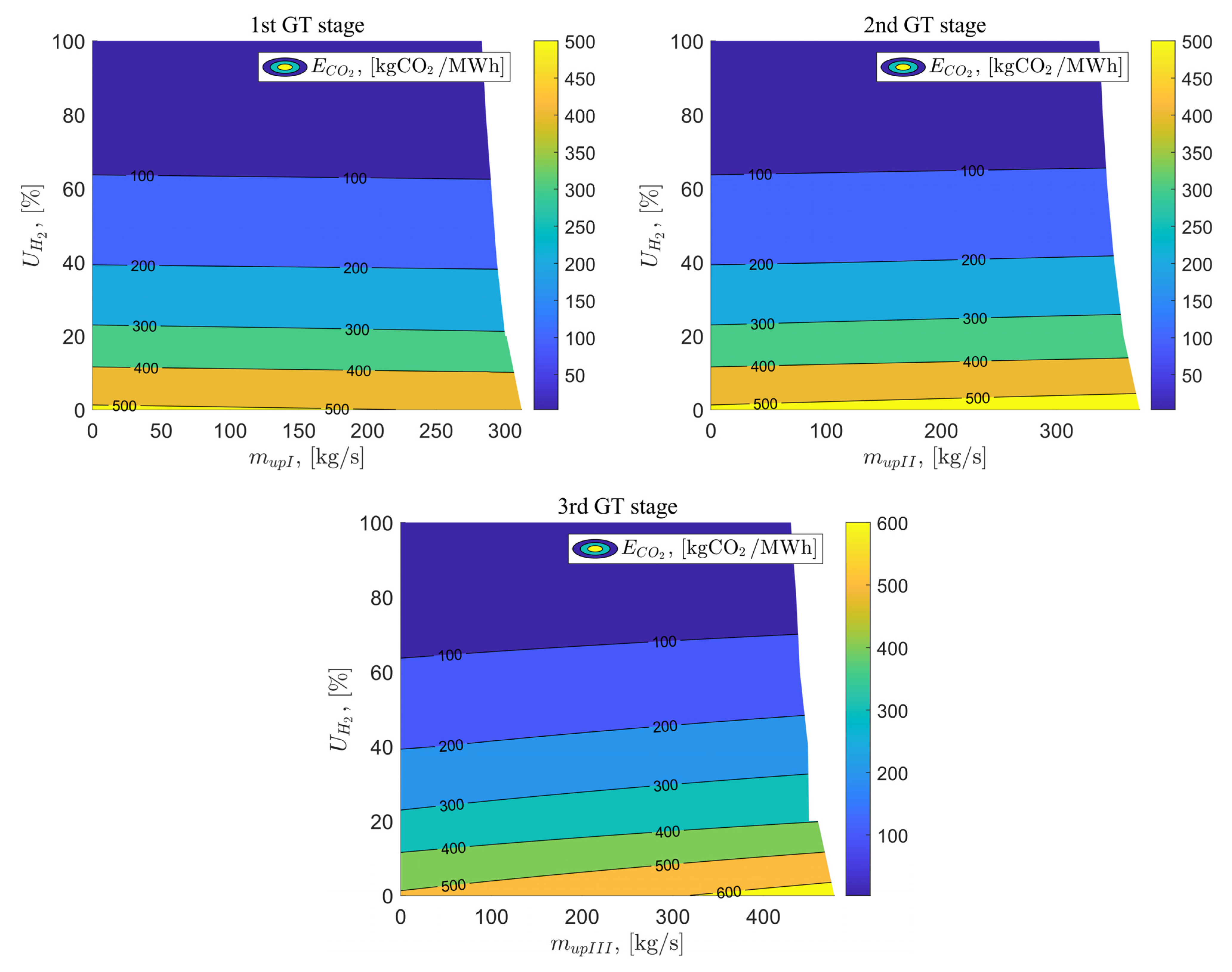

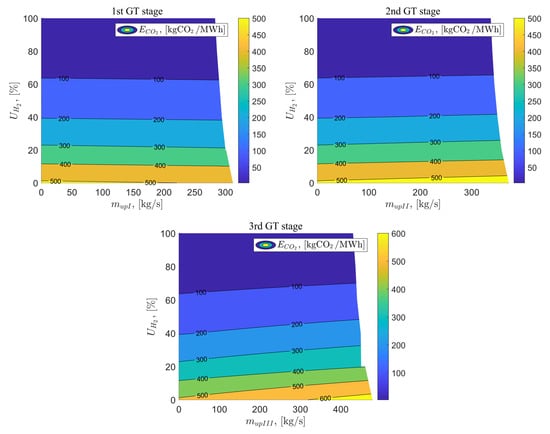

The last analyzed parameter was the carbon dioxide emissions to the environment . For the baseline variant, the carbon dioxide emissions amount to 512.44 kgCO2/MWh. Applying exhaust gas vent after the first stage of the gas turbine slightly reduces this emission, reaching a value of 494.35 kgCO2/MWh or the maximum vent of exhaust gas stream. In the cases of variants C and D, the carbon dioxide emissions to the environment increase with increasing vent of exhaust gas stream. Adding hydrogen fuel in the appropriate percentage allows for a reduction in CO2 emission in all analyzed cases. For = 40% and the maximum vent of exhaust gas stream after the I, II, and III stages of the gas turbine, the carbon dioxide emissions are as follows: 188.74 kgCO2/MWh, 207.71 kgCO2/MWh and 243.97 kgCO2/MWh. Using hydrogen fuel with the share = 100% allows for zero emissions resulting from fuel combustion. Figure 17 shows the analysis results for the carbon dioxide emissions to the environment as a function of the exhaust gas vented at the I, II, and III stages of the gas turbine, as well as the percentage of hydrogen in the fuel mixture.

Figure 17.

Carbon dioxide emissions to the environment as a function of the flux vented downstream of the 2nd GT stage and the percentage of hydrogen in the fuel.

The model analyzed does not take NOx emissions into account. Nevertheless, nitrogen oxide emissions are a significant challenge in the case of hydrogen co-firing or combustion. The main source of NOx in most gas systems is the air supplied from the environment, as its main components (nitrogen and oxygen) react at high temperatures [56]. Due to the higher temperatures of the hydrogen flame compared to traditional fuels, there is a risk of increased NOx emissions, even when burning pure hydrogen or mixtures with natural gas.

Article [57] highlights the impact of hydrogen content in fuel on NOx emissions in gas turbines. It is indicated that when measuring volume concentration (ppmv @ 15% O2), a higher hydrogen content in the fuel mixture can lead to overestimated NOx readings, even if the actual mass of NOx produced remains unchanged. It was emphasized that appropriate measurement corrections are necessary to correctly assess the impact of hydrogen co-combustion on NOx emissions and to avoid erroneous conclusions when comparing different fuels.

The studies presented in [58] also point the possibility of reducing NOx emissions through the use of lean premixed combustion, which involves preparing a fuel-air mixture that is lean in fuel, leading to a reduction in the maximum flame temperature. It has been shown that the addition of hydrogen can extend the limits of combustion stability and at the same time enable a reduction in NOx emissions, especially when it is introduced into the pilot fuel stream. These results suggest that an appropriate hydrogen dosing strategy and combustion system configuration can not only improve process stability, but also achieve a balance between low NOx and CO emissions, which is crucial for the practical application of hydrogen in gas turbines.

5. Discussion

The application of upgrading the gas system according to Szewalski’s idea and co-firing the hydrogen fuel brings many challenges. The implementation of new system components, such as hydrogen-compatible pipelines, valves, and burners, as well as additional heat exchangers and compressors, involves significant investment costs, which usually exceed the costs of standard gas system upgrades due to the use of specialized materials and engineering requirements. Co-firing hydrogen in existing turbines may require modifications to the combustion chamber and control systems to adapt them to different combustion properties and physicochemical characteristics compared to traditional fuels such as natural gas. This may lead to temporary downtime and additional operating and maintenance costs. Although the analyzed system is a gas turbine without a steam cycle, it is worth noting that when integrated with HRSG recovery boilers, standard designs may not be suitable for such high exhaust gas temperatures, which suggests the need to use advanced high-temperature materials and would entail increased investment costs. It should also be noted that while this study considers hydrogen share from 0 to 100%, practical limitations exist for current turbines: most older-generation gas turbines can safely handle only 5–10% hydrogen, newer turbines up to 30%, and a higher share would require special, non-standard turbine designs not yet produced industrially.

The main challenges associated with green hydrogen relate to the costs of its production, transport, and storage. Green hydrogen produced by electrolysis relies on energy from renewable sources [59]. Renewable energy sources are characterized by unstable operation, depending on weather conditions and the time of day. During periods of low electricity production, hydrogen production is unstable, which affects operating costs and supply chain stability. In addition, large-scale production of green hydrogen requires further investment in renewable energy sources and energy storage systems. The transport and storage of hydrogen requires the use of specialized tanks, as the gas must be stored under very high pressure or in liquefied form. Hydrogen is highly flammable and explosive, so it is necessary to use containers and safety systems adapted to its specific characteristics, including leak protection, adequate ventilation, and leak monitoring. Because hydrogen is a very light gas, it can penetrate through micro-gaps in installations and tanks [60,61].

The development of hydrogen technologies is hampered by the lack of consistent regulations governing the production, transport, storage, and combustion of hydrogen. In many countries, standards cover only selected stages, such as high-pressure storage, but do not regulate integration with gas networks or transport safety.

The challenges outlined above show that despite the great potential of green hydrogen, its large-scale implementation requires further technological development, infrastructure expansion, and harmonization of legal regulations and safety standards. Only when these conditions are met will it be possible to use hydrogen effectively and safely in future energy systems.

Despite the identified challenges, the proposed solution can find practical application in existing gas turbine systems through staged retrofitting and co-firing strategies, allowing gradual adaptation to hydrogen fuel. The main limitations of this study include the reliance on theoretical and modeling analyses without extensive experimental validation. Promising areas for further research include the development of advanced hydrogen storage technologies, more efficient electrolyzers, and improved integration with renewable energy sources, which together could enhance the feasibility and safety of large-scale hydrogen deployment.

6. Conclusions

Modifying the gas system according to Szewalski’s idea and co-firing hydrogen fuel has led to a significant improvement in the electrical efficiency of the gas turbine. The highest electrical efficiency of the gas turbine was achieved for variant B, where exhaust gas vent was applied after the I stage of the gas turbine, reaching 41.25% for parameters = 283 kg/s and = 100%. This represents an increase of 2.49 percentage points compared to the baseline system. In the case of the exhaust gas vent after the II and III stages of the gas turbine, efficiency was not increased with increasing exhaust gas stream.

The implementation of exhaust vent in all analyzed variants led to a significant increase in the temperature at the inlet to the combustion chamber and at the inlet to the gas turbine expander, contributing to the increasing electrical efficiency of the system. The CIT temperature for the baseline variant is 486.35 °C, and the COT temperature is 1466.38 °C. The highest values of these temperatures were achieved for variant B, reaching 1088.13 °C and 1491.08 °C, respectively. The increase in the temperature at the inlet to the gas turbine expander with the increasing flow of exhaust gas vented in all modified variants contributed to the increase in the cooling air flow to the rotor blade. The exhaust gas temperature passing through the III stage of the gas turbine was low enough that the cooling air flow for variants B, C, and D was 0 kg/s.

Increasing the percentage of hydrogen fuel allowed for a reduction in the fuel delivered to the combustion chamber. In the baseline variant, the fuel flow rate is 10.32 kg/s. A hundred percent hydrogen content in the fuel mixture reduced it to 4.04 kg/s in the case of the maximum possible vent of exhaust of gases behind the I stage of the gas turbine. This is the lowest value obtained in all analyzed cases of modifying the gas system according to Szewalski’s idea. The value of the hydrogen fuel flux decreases with increasing flue gas venting only if the flue gas vent is applied after the I stage of the gas turbine.

The airflow supplied to the gas turbine system decreases with the increase in exhaust gas flow which is vented and the percentage of hydrogen in the fuel mixture only for variant B when the vent of exhaust is behind the first stage of the gas turbine. In the other variants, the airflow supplied to the gas turbine system increases.

The addition of hydrogen fuel has a significant impact on reducing carbon dioxide emissions to the environment. Adding hydrogen to the fuel mixture at a percentage of 40% can reduce carbon dioxide emissions by over half in variants B, C, and D. When hydrogen is used as 100% of the fuel, emissions become negligible, arising only from impurities introduced into the system with the supplied air.

The modification of the gas system according to Szewalski’s idea is only justified when applying the vent of exhaust gas after the I stage of the gas turbine. Due to its properties, co-firing hydrogen fuel in the system not only allows for achieving additional thermodynamic benefits but also environmental ones.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.B.; methodology, O.B. and M.B.; software, O.B. and K.N.; validation, O.B. and M.B.; visualization: O.B. and K.N.; writing—original draft preparation, O.B. and K.N.; writing—review and editing, O.B., K.N. and M.B.; supervision, M.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The article processing charge (APC) was co-funded by the project: EU funds FSD—10.25 Development of higher education focused on the needs of the green economy. European Funds for Silesia 2021–2027: The modern methods of the monitoring of the level and isotopic composition of atmospheric CO2 (project no. FESL.10.25-IZ.01-06C9/23-00, PM: Barbara Sensuła). Research work co-funded by the statutory research of the Silesian University of Technology.

Data Availability Statement

All data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations and Nomenclature

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Abbreviation | |

| RES | renewable energy sources |

| LHV | lower heating value |

| COT | combustion outlet temperature |

| CIT | combustion inlet temperature |

| TIT | turbine inlet temperature |

| CCH | combustion chamber |

| TMF | thermal mechanical fatigue |

| AF | air filter |

| GT | gas turbine |

| HX | heat exchanger |

| C | compressor |

| G | generator |

| methane | |

| hydrogen | |

| thermal barrier coating | |

| Nomenclature | |

| efficiency | |

| electric power | |

| energy flow | |

| heat flux | |

| temperature | |

| enthalpy | |

| mass flow | |

| energy flux ratio of the exhaust gas leaving the GT/heat transfer coefficient | |

| individual gas constant value | |

| compression ratio | |

| specific heat | |

| lower heating value | |

| average isentropic exponent | |

| cooling rate | |

| sectional area | |

| velocity | |

| density | |

| Stanton number | |

| parameter k | |

| parameter b related to the cooling efficiency of the gas turbine | |

| Wobby number | |

| molar mass | |

| pressure | |

| relative humidity | |

| Subscripts | |

| cooling | |

| air | |

| electric | |

| gas turbine | |

| chemical | |

| fuel | |

| thermal | |

| internal | |

| turbine | |

| inlet | |

| outlet | |

| blade | |

| exhaust gases, gas, generator | |

| mechanical | |

| compressor, cold side | |

| pressure lose | |

| pressure drop | |

| hot side | |

| points in the system | |

| points in the system | |

References

- Ang, T.Z.; Salem, M.; Kamarol, M.; Das, H.S.; Nazari, M.A.; Prabaharan, N. A Comprehensive Study of Renewable Energy Sources: Classifications, Challenges and Suggestions. Energy Strategy Rev. 2022, 43, 100939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris Agreement on Climate Change-Consilium. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/climate-change/paris-agreement/ (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- The Paris Agreement|UNFCCC. Available online: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- Alessi, L.; Battiston, S.; Kvedaras, V. Over with Carbon? Investors’ Reaction to the Paris Agreement and the US Withdrawal. J. Financ. Stab. 2024, 71, 101232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraschiv, S. Analysis of the Variability of Low-Carbon Energy Sources, Nuclear Technology and Renewable Energy Sources, in Meeting Electricity Demand. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ould Amrouche, S.; Rekioua, D.; Rekioua, T.; Bacha, S. Overview of Energy Storage in Renewable Energy Systems. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 20914–20927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olabi, A.G. Renewable Energy and Energy Storage Systems. Energy 2017, 136, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behabtu, H.A.; Messagie, M.; Coosemans, T.; Berecibar, M.; Fante, K.A.; Kebede, A.A.; Mierlo, J. Van A Review of Energy Storage Technologies’ Application Potentials in Renewable Energy Sources Grid Integration. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, A.A.; Kalogiannis, T.; Van Mierlo, J.; Berecibar, M. A Comprehensive Review of Stationary Energy Storage Devices for Large Scale Renewable Energy Sources Grid Integration. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 159, 112213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhuyi Nazari, M.; Fahim Alavi, M.; Salem, M.; Assad, M.E.H. Utilization of Hydrogen in Gas Turbines: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Low-Carbon Technol. 2022, 17, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poullikkas, A. An Overview of Current and Future Sustainable Gas Turbine Technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2005, 9, 409–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasserman, A.A.; Shutenko, M.A. Methods of Increasing Thermal Efficiency of Steam and Gas Turbine Plants. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2017, 891, 012248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotowicz, J.; Brzęczek, M. Integration of the Gas Turbine with the Stirling Engine and Heat Recorvery [Integracja Turbiny Gazowej z Silnikiem Stirlinga i Odzyskiem Ciepła]. Rynek Energii 2018, 2018, 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, K.; Shaler, K.; Johnson, N.; Beardsell, A.; Collier, W.; Han, T.; Puspitasari, P.; Andoko, A.; Kurniawan, P. Failure Analysis of a Gas Turbine Blade: A Review. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater Sci. Eng. 2021, 1034, 012156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhang, B.; Hu, D.; Jiang, K.; Liu, H.; Mao, J.; Jing, F.; Hao, X. Thermomechanical Fatigue Experiment and Failure Analysis on a Nickel-Based Superalloy Turbine Blade. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2019, 102, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewangan, R.; Patel, J.; Dubey, J.; Kumar Sen, P.; Kumar Bohidar, S.; Author, C. Gas Turbines Blades-A Critical Review of Failure on First and Second Stages. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Rob. Res. 2015, 4, 216. [Google Scholar]

- Sankar, V.; Ramkumar, P.B.; Sebastian, D.; Joseph, D.; Jose, J.; Kurian, A. Optimized Thermal Barrier Coating for Gas Turbine Blades. Mater Today Proc. 2019, 11, 912–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundén, B. Heat Exchangers and Heat Recovery Processes in Gas Turbine Systems. In Modern Gas Turbine Systems: High Efficiency, Low Emission, Fuel Flexible Power Generation; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2013; pp. 224–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gas Turbine Upgrade with Heat Regenerator-Numerical Analysis of Advantages and Disadvantages. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/346399709_GAS_TURBINE_UPGRADE_WITH_HEAT_REGENERATOR_-NUMERICAL_ANALYSIS_OF_ADVANTAGES_AND_DISADVANTAGES#fullTextFileContent (accessed on 13 March 2024).

- Razak, A.M.Y. Gas Turbine Performance Modelling, Analysis and Optimisation. In Modern Gas Turbine Systems: High Efficiency, Low Emission, Fuel Flexible Power Generation; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2013; pp. 423–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassily, A.M. Performance Improvements of the Intercooled Reheat Recuperated Gas-Turbine Cycle Using Absorption Inlet-Cooling and Evaporative after-Cooling. Appl. Energy 2004, 77, 249–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power Augmentation of PGE Gorzow’s Gas Turbine by Steam Injection—Thermodynamic Overview. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267203049_Power_augmentation_of_PGE_gorzow’s_gas_turbine_by_steam_injection_-_Thermodynamic_overview#fullTextFileContent (accessed on 13 March 2024).

- Ziółkowski, P.; Lemański, M.; Badur, J.; Zakrzewski, W. Wzrost Sprawności Turbiny Gazowej Przez Zastosowanie Idei Szewalskiego. Rynek Energii 2012, 3, 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.J.; Chiou, J.S. Performance Improvement for a Simple Cycle Gas Turbine GENSET—A Retrofitting Example. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2002, 22, 1105–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziółkowski, P.; Badur, J.; Ziółkowski, P.J. An Energetic Analysis of a Gas Turbine with Regenerative Heating Using Turbine Extraction at Intermediate Pressure-Brayton Cycle Advanced According to Szewalski’s Idea. Energy 2019, 185, 763–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezirolu, T.N.; Barbir, F. Hydrogen: The Wonder Fuel. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 1992, 17, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Jain, S.; Ps, V.; Tiwari, A.K.; Nouni, M.R.; Pandey, J.K.; Goel, S. Hydrogen: A Sustainable Fuel for Future of the Transport Sector. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 51, 623–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atilhan, S.; Park, S.; El-Halwagi, M.M.; Atilhan, M.; Moore, M.; Nielsen, R.B. Green Hydrogen as an Alternative Fuel for the Shipping Industry. Curr. Opin Chem. Eng. 2021, 31, 100668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasul, M.G.; Hazrat, M.A.; Sattar, M.A.; Jahirul, M.I.; Shearer, M.J. The Future of Hydrogen: Challenges on Production, Storage and Applications. Energy Convers Manag. 2022, 272, 116326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelletti, A.; Martelli, F. Investigation of a Pure Hydrogen Fueled Gas Turbine Burner. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 10513–10523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecere, D.; Giacomazzi, E.; Di Nardo, A.; Calchetti, G. Gas Turbine Combustion Technologies for Hydrogen Blends. Energies 2023, 16, 6829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D. Review on the Development Trend of Hydrogen Gas Turbine Combustion Technology. J. Korean Soc. Combust. 2019, 24, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichel, T.G.; Paschereit, C.O. Interaction Mechanisms of Fuel Momentum with Flashback Limits in Lean-Premixed Combustion of Hydrogen. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 4518–4529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichel, T.G.; Terhaar, S.; Paschereit, O. Increasing Flashback Resistance in Lean Premixed Swirl-Stabilized Hydrogen Combustion by Axial Air Injection. J. Eng. Gas. Turbine Power 2015, 137, 071503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World’s First Successful Technology Verification of 100% Hydrogen-Fueled Gas Turbine Operation with Dry Low NOx Combustion Technology|Press Release|NEDO. Available online: https://www.nedo.go.jp/english/news/AA5en_100427.html (accessed on 5 April 2024).

- Hydrogen Europe. Available online: https://hydrogeneurope.eu/siemens-and-others-test-first-100-h2-gas-turbine-in-france/ (accessed on 21 March 2024).

- CORRECTION: Siemens Energy Burns 100% Hydrogen in Industrial Gas Turbine in Energy-Storage Pilot|Hydrogen News and Intelligence. Available online: https://www.hydrogeninsight.com/power/correction-siemens-energy-burns-100-hydrogen-in-industrial-gas-turbine-in-energy-storage-pilot/2-1-1535850 (accessed on 21 March 2024).

- MHI, Mitsubishi Power Report Breakthroughs for Hydrogen Combustion, Ammonia Burners. Available online: https://www.powermag.com/mhi-mitsubishi-power-report-breakthroughs-for-hydrogen-combustion-ammonia-burners/ (accessed on 21 March 2024).

- Mitsubishi Power Completes 30% Hydrogen Co-Firing Demo Using Grid-Connected Gas Turbine—Offshore Energy. Available online: https://www.offshore-energy.biz/mitsubishi-power-completes-30-hydrogen-co-firing-demo-using-grid-connected-gas-turbine/ (accessed on 21 March 2024).

- Matsumoto, T.; Kawakami, T.; Nakamura, S.; Yuri, M. Development of Hydrogen/Ammonia-Firing Gas Turbine for Carbon Neutrality. Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Technical Review 59. Available online: https://www.mhi.com/technology/review/sites/g/files/jwhtju2326/files/tr/pdf/e594/e594040.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Urbanik, M.; Tchorzewska-Cieslak, B.; Pietrucha-Urbanik, K. Analysis of the Safety of Functioning Gas Pipelines in Terms of the Occurrence of Failures. Energies 2019, 12, 3228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashchenko, D. Hydrogen-Rich Gas as a Fuel for the Gas Turbines: A Pathway to Lower CO2 Emission. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 173, 113117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koç, Y.; Yağlı, H.; Görgülü, A.; Koç, A. Analysing the Performance, Fuel Cost and Emission Parameters of the 50 MW Simple and Recuperative Gas Turbine Cycles Using Natural Gas and Hydrogen as Fuel. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 22138–22147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juste, G.L. Hydrogen Injection as Additional Fuel in Gas Turbine Combustor. Evaluation of Effects. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2006, 31, 2112–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotowicz, J.; Job, M.; Brzeczek, M. The Characteristics of Ultramodern Combined Cycle Power Plants. Energy 2015, 92, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjay; Prasad, B.N. Energy and Exergy Analysis of Intercooled Combustion-Turbine Based Combined Cycle Power Plant. Energy 2013, 59, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wettstein, H.E. The Potential of GT Combined Cycles for Ultra High Efficiency. Turbo Expo Power Land Sea Air 2013, 3, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmielniak, T.J.; Czwiertnia, K.; Rusin, A. Turbiny Gazowe; Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich: Wrocław, Poland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Szargut, J. Termodynamika Techniczna; Wydawnictwo Politechniki Śląskiej: Gliwice, Poland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 2314:2009; Gas Turbines—Acceptance Tests. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/42989.html (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- Sanjay; Singh, O.; Prasad, B.N. Comparative Performance Analysis of Cogeneration Gas Turbine Cycle for Different Blade Cooling Means. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2009, 48, 1432–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjay; Singh, O.; Prasad, B.N. Influence of Different Means of Turbine Blade Cooling on the Thermodynamic Performance of Combined Cycle. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2008, 28, 2315–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gas Turbine Cooling Model for Evaluation of Novel Cycles. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237502557_Gas_turbine_cooling_model_for_evaluation_of_novel_cycles (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Kotowicz, J.; Brzęczek, M. Analysis of Increasing Efficiency of Modern Combined Cycle Power Plant: A Case Study. Energy 2018, 153, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, N.; Khan, I.A.; Grover, S. Structural Modeling of a Typical Gas Turbine System. Front. Energy 2012, 6, 57–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitanggang, R.B. Performance and Emission Analysis of Hydrogen and Natural Gas Cofiring in Combined Cycle Gas Turbine Power Generation. J. Appl. Eng. Sci. 2023, 21, 678–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, C.; Emerson, B.; Lieuwen, T.; Martz, T.; Steele, R. NOx Emissions from Hydrogen-Methane Fuel Blends; Georgia Institute of Technology: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshirnura, T.; McDonell, V.; Samuelsen, S. Evaluation of Hydrogen Addition to Natural Gas on the Stability and Emissions Behavior of a Model Gas Turbine Combustor. Turbo Expo Power Land Sea Air 2008, 2, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algburi, S.; Munther, H.; Al-Dulaimi, O.; Fakhruldeen, H.F.; Sapaev, I.B.; Al Seedi, K.F.K.; Khalaf, D.H.; Jabbar, F.I.; Hassan, Q.; Khudhair, A.; et al. Green Hydrogen Role in Sustainable Energy Transformations: A Review. Results Eng. 2025, 26, 105109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulky, L.; Srivastava, S.; Lakshmi, T.; Sandadi, E.R.; Gour, S.; Thomas, N.A.; Shanmuga Priya, S.; Sudhakar, K. An Overview of Hydrogen Storage Technologies—Key Challenges and Opportunities. Mater Chem. Phys. 2024, 325, 129710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Zhang, R.; Shi, Z.; Lin, J. Review of Common Hydrogen Storage Tanks and Current Manufacturing Methods for Aluminium Alloy Tank Liners. Int. J. Lightweight Mater. Manuf. 2024, 7, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.