Abstract

Electrical stimulation is increasingly explored as a strategy to accelerate the development of electroactive biofilms in microbial fuel cells (MFCs), yet its integration with photosynthetic MFCs (pMFCs) remains insufficiently understood. This study evaluated how short-term anodic stimulation (0.5–5 V, 4 days) affects biofilm formation and COD removal, and how subsequent operation with photosynthetic cathodes—Chlorella sp., Arthrospira platensis and Tetraselmis subcordiformis—modulates anodic microbial communities and functional potential. Stimulation at 1 V yielded the best activation effect, resulting in the highest voltage output, power density and fastest COD removal kinetics, whereas 5 V inhibited biofilm development. During pMFC operation, Chlorella produced the highest voltage (0.393 ± 0.064 V), current density (0.14 ± 0.02 mA·cm−2) and Coulombic efficiency (~19%). Arthrospira showed moderate performance, while Tetraselmis generated no current despite efficient COD removal. 16S rRNA sequencing revealed distinct cathode-driven community shifts: Chlorella enriched facultative electroactive taxa, Arthrospira promoted sulfur-cycling bacteria and Actinobacteria, and Tetraselmis induced strong methanogenic dominance. Functional prediction and qPCR confirmed these trends, with Chlorella showing increased pilA abundance and Tetraselmis displaying enriched methanogenic pathways. Overall, the combined use of optimal anodic stimulation and photosynthetic cathodes demonstrates that cathodic microalgae strongly influence anodic redox ecology and energy recovery, with Chlorella-based pMFCs offering the highest electrochemical performance.

1. Introduction

The growing global demand for energy, coupled with the rapid depletion of fossil fuel reserves, has led to an increasingly critical energy crisis. This situation has prompted intensive research into renewable energy sources that are both environmentally sustainable and economically viable. In parallel, increasing urbanization, overpopulation, and industrialization have contributed to severe environmental pollution, posing significant threats to ecosystems and human health.

One promising solution to these challenges involves the integration of microalgae with microbial fuel cells. MFCs are bioelectrochemical systems that utilize microorganisms as biocatalysts to convert chemical energy stored in organic compounds into electrical energy [1]. In the anodic chamber, microorganisms oxidize reduced substrates, releasing electrons and protons, which are transferred to the anode and subsequently flow through an external circuit to the cathode. Microalgae introduced into the cathodic chamber generate oxygen in situ, serving as the terminal electron acceptor and supporting cathodic reactions that sustain electricity generation [2,3]. This coupling of microbial oxidation with photosynthetic oxygen production offers a self-sustaining approach to simultaneous energy recovery and wastewater treatment.

Despite these advantages, the practical application of pMFCs faces several challenges, particularly related to the development of electroactive anodic biofilms and the selection of suitable microalgal strains [4,5]. The efficiency of pMFCs depends heavily on the establishment of stable anodic biofilms capable of continuous electron transfer. Initial microbial adhesion and subsequent biofilm development are strongly influenced by electrode potential, surface properties, substrate type, and environmental conditions [6].

A promising strategy to enhance anodic biofilm formation involves the use of external electrical stimulation. Moderate electric fields have been shown to influence microbial adhesion, growth, and biofilm structure across various disciplines. While high-intensity electric fields (kV·cm−1 range) are commonly applied for microbial inactivation and sterilization, low-intensity fields (mV·cm−1 range) can modulate bacterial adhesion and biofilm development on conductive materials such as stainless steel, gold, platinum, and indium tin oxide [7]. In water and wastewater treatment systems, low-voltage alternating potentials (e.g., 1.5 V) have been applied to mitigate membrane and spacer biofouling by promoting bacterial detachment and partial inactivation [8].

Sun et al. [9] demonstrated that anodic biofilms in microbial electrolysis cells respond markedly to applied potentials: at 0.7 V, biofilms exhibited stratified structures with moderate current densities, whereas an increase to 0.9 V produced more homogeneous and metabolically active biofilms with a 61% increase in current output. Similar findings across electrochemical systems have confirmed that electrical stimulation in the low-voltage region (near ±1 V) can significantly accelerate microbial colonization and enhance electron-transfer activity [10]. Under high-voltage stimulation electrochemical production of reactive oxygen species such as hydroxyl radicals, hydrogen peroxide, and chlorine may contribute to microbial inactivation [11]. Due to the lack of clear and consistent data specifically related to MFC and pMFC systems, the experimental design was based on data reported for other above-mentioned electrochemical systems. Therefore, the study investigated low and moderate stimulation voltages (0.5 and 1 V) to influence biofilm formation and electroactivity without causing severe inhibitory effects, while 5 V was included as a higher-intensity condition to explore potential threshold effects and stress responses.

In pMFCs, the incorporation of microalgae introduces additional complexity and potential for synergistic interactions. Microalgae influence cathodic performance through oxygen evolution, pH regulation, nutrient assimilation, extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) release, and species-specific photosynthetic dynamics [12]. These processes can indirectly modulate anodic biofilms by altering electron acceptor availability, ionic balance, and cross-chamber redox gradients [2]. Different microalgal species vary widely in their photosynthetic efficiency and metabolic profiles, which may translate into differences in electricity generation, organic matter degradation, and microbial community structure at the anode [3,5]. Understanding how algae modulate anodic microbiomes is therefore crucial for optimizing pMFC performance and identifying ideal microalgal strains for sustainable bioelectricity production.

In this study, the combined effects of low-voltage anodic stimulation and photosynthetic biocathodes on the development, activity, and microbial structure of anodic biofilms were investigated. First, different electrical stimulation regimes (0.5, 1, and 5 V) were tested on biofilm formation, electrochemical activity, and wastewater treatment efficiency using scanning electron microscope (SEM) observations and COD removal analysis. In the second stage, the optimal stimulation condition was applied to pMFCs equipped with three microalgal species (Chlorella sp., Arthrospira platensis, and Tetraselmis subcordiformis (syn. Platymonas subcordiformis)) and their influence on anodic microbial community structure was examined using 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing. Together, these experiments provide new insights into how electrical stimulation and microalgae jointly regulate biofilm development and shape the performance of pMFC.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. MFC and pMFC Construction

Dual-chamber, H-type fed-batch MFCs were constructed using 1000 mL glass bottles. The anodic and cathodic chambers were separated by a Nafion™ 117 proton-exchange membrane (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA; 5 × 5 cm). The anode consisted of a 5 × 5.5 cm piece of carbon cloth (effective surface area: 28 cm2), while the cathode was a carbon rod (diameter: 0.4 cm; effective surface area: 17.84 cm2). Both chambers were continuously mixed with magnetic stirrers to maintain suspended biomass and enhance mass transfer. All experiments were carried out at room temperature (20–22 °C). The electrodes were connected through an external circuit containing a 100 Ω resistor, and the voltage and current were monitored using a digital multimeter.

2.2. Synthetic Wastewater and Cathode Media in MFC

The anodic chamber was filled with tenfold diluted synthetic wastewater (composition in Table 1), which served as the influent substrate for MFC and pMFC operation. The initial concentrations of pollution indicators were approximately 1443 ± 95 mg O2·L−1, 395 ± 42 mg N·L−1, 381 ± 21 mg NH4-N·L−1, 132 ± 18 mg P·L−1, with the pH adjusted to 6.8–7.0. The cathodic chamber in MFC was filled with 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) and continuously aerated (100 L·h−1). After one week of operation, 100 mL of treated effluent was withdrawn and replaced with an equal volume of fresh wastewater. This feeding cycle was repeated for four weeks, during which voltage, current, and wastewater quality parameters were monitored.

Table 1.

Composition of the modified Geobacter medium (DSMZ 826) used as the anode feed solution in the MFC and pMFC experiments, including carbon, nitrogen and trace element sources.

2.3. Anodic Electrical Stimulation Experiments

To investigate the effect of electrical stimulation on anodic biofilm development, the anodes were polarized using a Manson Dual Tracking DC Power Supply (DPD-3030) (Manson Engineering Industrial Ltd., Hong Kong, China). The stimulation was performed exclusively within the anodic compartment, without connecting the cathode, to promote microbial adhesion rather than electricity generation. The anodic chamber was filled with anaerobic sludge obtained from the municipal wastewater treatment plant “Łyna” (Olsztyn, Poland), serving as a natural inoculum of electroactive microorganisms. The chamber was flushed with an 80% N2/20% CO2 gas mixture for 10 min to maintain anaerobic conditions. Experiments were conducted in the dark, with the chamber wrapped in aluminum foil. During stimulation, the carbon cloth anode (working electrode) and a silver wire electrode (counter electrode) were placed inside the anodic chamber and connected directly to the power supply. Constant voltages of 0.5 V, 1 V, and 5 V were applied for four days in separate setups. After four days of stimulation, the power supply was disconnected. The remaining free-floating sludge was removed, leaving only biomass attached to the anode surface. The anodic chamber was filled with 1 L of tenfold diluted synthetic wastewater (composition in Table 1), which served as the influent substrate for MFC operation. The experiment was conducted for 28 days, and the culture medium was replaced weekly to ensure the continuous supply of essential components required for bacterial metabolism and energy production.

2.4. Operation of pMFCs with Microalgae/Cyanobacteria

After identifying the optimal stimulation regime, the experiment has been restarted, i.e., anode chamber was filled with anaerobic sludge, then flushed with gas mixture and stimulation with 1 V for 4 days was performed. After stimulation, the remaining suspended sludge was replaced with synthetic wastewater. The photosynthetic microorganisms were introduced into the cathodic chamber to evaluate their influence on pMFC performance and anodic microbial community structure. Three species were used: Chlorella sp. (pMFC1), Arthrospira platensis (pMFC2), Tetraselmis subcordiformis (pMFC3) plus a cathode without microorganisms (control–MFC).

Each cathodic chamber was supplied with the culture medium based on mixture of mineral fertilizers. The basic ingredient was AZOFOSKA at a dosage of 1.0 g·L−1 (Grupa INCO S.A., Góra Kalwaria, Poland) with the composition specified by the manufacturer: 13.3% NTOT, 5.5% N-NO3, 7.8% N-NH4, 6.1% P2O5 soluble in neutral ammonium citrate solution (C6H17N3O7) and H2O, 4.0% P2O5 soluble in H2O, 17.1% K2O soluble in H2O, 4.5% MgO, 21.0% SO3. To increase the phosphate concentration in the medium, POLIFOSKA was provided at a dosage of 0.25 g·L−1 (Grupa AZOTY SA, Puławy, Poland) with the composition specified by the manufacturer: 8% N-NH4, 24% P2O5 soluble in neutral (C6H17N3O7) and H2O, i.e., assimilable in the form of mono- and diammonium phosphate, 24% K2O soluble in H2O and 9% SO3 soluble in H2O. The microelements were ensured by using the MikroPlus solution (Intermag, Olkusz, Poland) at the rate of 0.1 mL ·L−1 with the following composition: 2.3 g·L−1 B as acid, 1.2 g·L−1 Cu chelated with EDTA, 22.3 g·L−1 Fe chelated with EDTA, 9.5 g·L−1 Mn chelated with EDTA, 0.6 g·L−1 Mo as ammonium salt, 3.5 g·L−1 Zn chelated with EDTA. Tetraselmis subcordiformis is a marine microalgae and to ensure its growth the fertilizers were added to a previously prepared solution of the synthetic sea salt reef crystals (Aquarium Systems, Sarrebourg, France) with a specific gravity of 1.024 g·cm−3 (pH of the medium 8.3). Arthrospira platensis require medium with high concentrations of carbonates and bicarbonates, which were added to the medium in the amount of 13.61 g·L−1 NaHCO3 and 4.03 g·L−1 Na2CO3 (pH of the medium 9). Additionally, the cathodic chamber with cyanobacteria biomass was heated to temperature of 30 °C. After approximately two weeks of logarithmic growth, 100 mL of the algal medium was regularly replaced with a fresh portion of medium. During each replacement step, a fraction of the biomass was also removed from the pMFC.

The cathodic chambers were illuminated under a 16:8 h light–dark cycle using white fluorescent lamps (100 μmol photons·m−2·s−1). Aeration (100 L·h−1) provided oxygen for reaction at the cathode and ensured CO2 availability for photosynthesis.

2.5. Measurement of Biomass Growth

The samples for volatile solids and chlorophyll determination were collected every 24 h. Volatile solids were determined gravimetrically by burning the biomass at 550 °C (muffle furnace LAC L, Dabrowica, Poland) and then weighing the ash (DanLab AX423, Białystok, Poland). Taxonomic analysis of microalgae/cyanobacteria biomass was performed using a MF 346 biological microscope with an Optech 3MP camera (Eduko, Warsaw, Poland) and determined using the fluorescence method (Algae Online Analyzer bbe Moldanke, Schwentinental, Germany).

2.6. Electrochemical Measurements

Electrochemical performance of the MFC and pMFC was monitored throughout the experiments by continuous measurement of the cell voltage (U) across an external resistor. The voltage was recorded at 1-min intervals using a digital multimeter (UNI-T UT803) (Uni-Trend Technology, Dongguan, Guangdong Province, China) connected to a data-logging interface. Current (I) was calculated using Ohm’s law:

where Rext was set to 100 Ω for all experimental variants. Current density (j) was expressed relative to the geometric surface area of the anode (A) (28 cm2):

Power density (P) was calculated as:

The reported values represent the mean output during the stable operational phase of each MFC/pMFC. Coulombic efficiency (CE) was determined based on the measured current and the amount of substrate oxidized, expressed as COD:

where Fis Faraday’s constant (96,485 C mol−1 ∙ e−), b = 4 mol e− per mol O2 (8 g O2 per mol e−), V is the working volume, and ΔCOD is the experimentally determined COD removal over time t.

2.7. Chemical Analyses

The COD concentration was determined with Hach Lange cuvette tests using a DR 5000 UV-vis spectrophotometer (Hach Lange, Berlin, Germany). The COD changes followed pseudo-first-order kinetic. COD decline in each 7-day cycle was fitted using a three-parameter exponential decay model with an asymptote, optimized via the Gauss–Newton non-linear regression algorithm.

2.8. SEM Analysis

At the end of the operational period with different stimulation assessment, anode samples were collected for SEM analysis to assess biofilm morphology and electrode colonization. Anodes were gently removed from the reactors and rinsed twice with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to eliminate loosely attached biomass. Samples were dehydrated through a graded ethanol series (30%, 50%, 70%, 90%, 100%; 15 min each). After dehydration, they were immersed in hexamethyldisilazane for 60 min and allowed to air-dry overnight. Dried electrodes were placed on copper tables and sputter-coated with gold in an argon atmosphere in an ionic coater (Fine Coater, JCF-1200, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). The sputter-coated material was placed in an SEM column (JSM-5310LV, JEOL, Japan with EDS Noran System 7, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and analyzed at 5–10 kV.

2.9. Amplicon Sequencing and Bioinformatic Workflow

Amplicon sequencing of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was performed by Novogene Co. (Beijing, China) as part of the Amplicon Metagenomics Sequencing (WBI) 16S V3–V4 package. Sequencing was performed as paired-end 2 × 250 bp reads on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000. Processing used QIIME 2 (v2023.x): demultiplexing and adapter trimming with Cutadapt 3.3, denoising, merging, chimera removal via DADA2, ASV inference at single-nucleotide resolution taxonomy assignment using a Naïve Bayes classifier trained on SILVA 138.1 (trimmed to the 341F–806R region). Chloroplast and mitochondrial ASVs were removed. ASV tables were rarefied to a uniform depth prior to diversity analyses. Alpha-diversity metrics (Observed ASVs, Shannon, Simpson, Chao1, Pielou’s evenness) were computed in Python (v3.10) using the NumPy (v1.24) and Pandas (v1.5) libraries. The rarefaction curve and the high Good’s coverage value (pMFC1 = 0.997074; pMFC2 = 0.997266; pMFC3 = 0.997112; MFC = 0.996381) suggest sufficient sequencing depth. Beta-diversity analysis (Bray–Curtis dissimilarity) and PCoA ordination were performed in QIIME 2 and visualized in R. Because sequencing was performed on one (pooled) sample per condition, statistical testing of between-group differences (PERMANOVA/ANOSIM) was not performed.

2.10. Functional Prediction

Functional metabolic profiles of the anodic communities were inferred from 16S rRNA gene ASV tables using a trait-based approach. Taxonomic assignments generated in QIIME 2 were processed with FAPROTAX v.1.2.7, which maps bacterial and archaeal taxa to experimentally validated functional groups based on curated literature associations and avoids genome-based inference errors typical for PICRUSt-type tools in non-model anaerobic communities. The ASV table was converted to functional categories using the default FAPROTAX database, and functions with zero counts across all samples were removed.

To enable quantitative comparison among pMFC variants, the resulting functional table was normalized to relative abundances by dividing each functional count by the total predicted function count of the corresponding sample. Because functional datasets often span several orders of magnitude and include both dominant and low-frequency pathways, data were additionally transformed using row-wise Z-score standardization, which highlights sample-to-sample differences within each functional category without inflating the contribution of high-abundance traits.

For downstream analyses and visualization, only the TOP-20 most abundant functional categories (based on total relative abundance across all samples) were retained, as commonly recommended to minimize noise introduced by rare functions. These categories were visualized as a heatmap using R (packages pheatmap, vegan, and phyloseq), with hierarchical clustering disabled to allow direct comparison of functional patterns among pMFC1, pMFC2, pMFC3, and the MFC control.

This approach identifies the functional potential associated with the taxonomic profile rather than direct metabolic measurements, and therefore reflects genomic traits of detected taxa. As such, categories such as “aerobic chemoheterotrophy” represent facultative heterotrophs commonly classified as aerobic in databases but capable of anoxic metabolism in bioelectrochemical environments.

2.11. Real-Time Quantitative PCR

The electron transfer-related functional gene abundances of pilA, omcS, and omcB were determined [13,14]. The reactions were performed in a 20 μL mixture consisting of 12 μL Maxima SYBR Green/ROX qPCR Master Mix (2x) (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), 0.5 μM primer (each) and 1 μL of genomic DNA template. qPCR assays were carried out in triplicate using a QuantStudio™ 3 Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Scientific). The annealing temperatures followed previously established protocols. The PCR conditions includes initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at a specific temperature (60 °C for pilA and omcS; 58 °C for omcB) for 30 s and extension at 72 °C for 30 s, with a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. Reactions were normalized by adding the same amount of DNA for each reaction tube. The results were calculated using of the 2−ΔΔCt method [15]. For clarity of graphical presentation, relative quantification values were transformed to log2 (fold change).

2.12. Experimental Replication and Data Processing

All experiments conducted in both MFC and pMFC systems were performed in duplicate. Similarly, all physicochemical analyses were carried out in two independent replicates. The results presented in this study represent the mean values calculated from these replicates. For microbiological analyses, biomass samples were collected from both experimental replicates and subsequently pooled to obtain a representative composite sample for each experimental condition. For high-throughput sequencing analyses, a single composite sample from each experiment was submitted for sequencing. This approach was applied to ensure an integrated representation of the microbial community developed under the given operational conditions.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effects of Anodic Stimulation on Electrochemical Performance

3.1.1. Start-Up, Voltage Output, Current and Power Density

First stage of the study tested the electrochemical performance of MFCs operated under a constant external resistance of 100 Ω after a 4-day anodic stimulation period at different applied voltages (0.5 V, 1 V, and 5 V), compared to an unstimulated control. The short stimulation time was selected to assess the early biofilm-enhancement potential without prolonged electrochemical conditioning (Table 2).

Table 2.

Electrochemical performance parameters of MFCs subjected to four-day anodic stimulation at 0.5, 1 and 5 V, including average voltage output, current density, power density and CE.

Anodic polarization had a clear impact on the electrochemical activation and performance of the MFC (Table 2). Both 0.5 V and 1 V stimulation improved MFC start-up behavior and power output compared to the control. The most favorable response was observed at 1 V, resulting in the shortest start-up time (340 ± 15 min) and the highest average voltage (0.253 ± 0.014 V), corresponding to a current density of 0.09 ± 0.01 mA·cm−2 and power density of 229 ± 25 mW·m−2. Moderate stimulation at 0.5 V also enhanced performance, although to a lesser extent, yielding a current density of 0.08 ± 0.01 mA·cm−2 and a power density of 187 ± 47 mW· m−2. In contrast, anodic stimulation at 5 V resulted in inferior performance relative to the control, reflected by a lower average voltage (0.150 ± 0.01 V), reduced current density (0.05 ± 0.01 mA·cm−2), and slower start-up. This suggests that high polarization levels induced stress to the microbial community and hindered biofilm maturation. CE also improved following stimulation, from 8.5 ± 0.7% in the control to about 10% for the 0.5–1 V treatments, whereas the 5 V variant demonstrated a decrease to 7.6 ± 1.2%. Overall, short-term low-voltage anodic stimulation promoted early biofilm development and enhanced electrochemical activity, while excessive polarization impaired MFC performance. These results indicate that 1 V stimulation for 4 days represents an optimal balance between biofilm activation and microbial integrity in the initial conditioning phase.

3.1.2. COD Removal Kinetics Under Different Stimulation Regimes

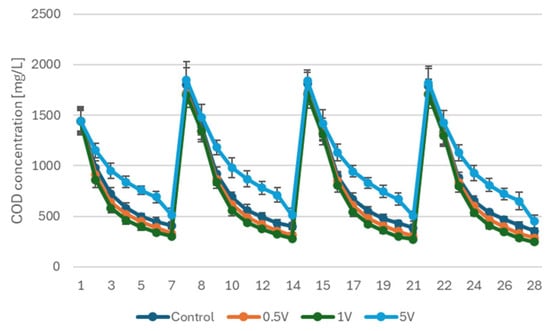

The temporal profiles of COD concentration during the 28-day operation are presented in Figure 1. All reactors exhibited a characteristic cyclic pattern resulting from the weekly fed-batch regime, in which each substrate addition caused an immediate increase in COD, followed by a continuous exponential decline driven by anaerobic and bioelectrochemical oxidation.

Figure 1.

COD removal profiles during 28 days of MFC operation following four-day anodic stimulation at 0.5, 1 and 5 V.

Although the COD level after each feeding event was comparable among treatments (typically 1300–1850 mg·L−1), the reactors differed markedly in the subsequent degradation trajectories. The MFC polarized at 1 V consistently showed the most pronounced COD removal in every weekly cycle, with concentrations decreasing to approximately 300 mg∙L−1 by the end of each 7-day interval. A slightly slower but still enhanced performance was observed in the 0.5 V treatment, whereas the control exhibited intermediate removal and the 5 V MFC showed the lowest degradation efficiency, with residual COD remaining above 500 mg∙L−1 after each cycle.

The resulting kinetic parameters (Table 3) consistently demonstrated the highest rate constants and initial degradation velocities in the 1 V treatment. In the first cycle, the initial COD removal rate reached approximately 0.79 g·L−1·d−1, while in the subsequent cycles it stabilized at 0.67–0.68 g·L−1·d−1. The 0.5 V treatment showed slightly lower rate constants and initial velocities, although still substantially exceeding those of the control. By contrast, the 5 V reactor exhibited markedly reduced degradation kinetics in all cycles, with initial velocities ranging from 0.28 to 0.43 g·L−1·d−1 indicating a persistent inhibitory effect of excessive anodic polarization on the biofilm.

Table 3.

Reaction rate constants for COD removal obtained using the Gauss–Newton non-linear estimation model during operation of MFCs stimulated at 0.5, 1 and 5 V as well as the non-stimulated control.

The concentration time-series and the kinetic model outputs showed excellent agreement. The steepest declines in COD consistently occurred within the first 48–72 h of each cycle. The hierarchy of the kinetic parameters remained unchanged throughout the entire experimental period, demonstrating that moderate anodic polarization (1 V) provides sustained stimulation of anodic biodegradation, whereas excessive polarization (5 V) hampers metabolic activity despite identical organic loading conditions. Overall, the combined concentration profiles and kinetic modelling unequivocally indicate that controlled anodic stimulation substantially enhances COD removal efficiency in the MFC, with the 1 V treatment delivering the most favorable and reproducible degradation performance.

3.1.3. SEM-Based Evaluation of Biofilm Morphology

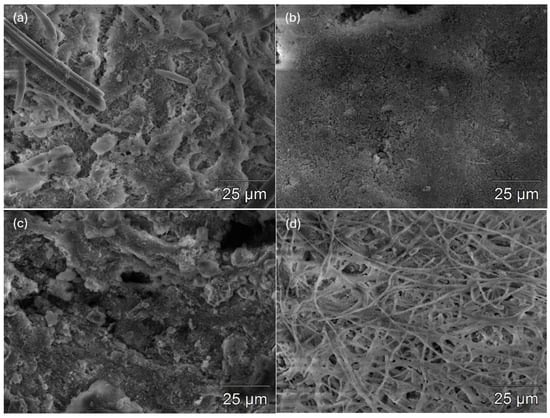

Representative SEM micrographs of the anodic carbon surface revealed distinct biofilm morphologies depending on the applied pre-polarization voltage (Figure 2). The control electrode (no stimulation) exhibited irregular, discontinuous microbial attachment with visible areas of exposed carbon substrate and loosely associated flake-like structures, indicative of spontaneous but limited biofilm development. Individual microbial cells were sparsely distributed, and a heterogeneous surface matrix suggested weak EPS cohesion.

Figure 2.

SEM images of anodic biofilms after four-day stimulation at (a) control, (b) 0.5 V, (c) 1 V and (d) 5 V.

In contrast, mild electrochemical stimulation at 0.5 V promoted more uniform colonization. The anode surface appeared smoother at the microscale, covered with a continuous EPS layer and higher microbial density compared to the control. The surface texture was more homogeneous, suggesting enhanced adhesion and early biofilm consolidation.

The 1 V-treated anode displayed the most compact and structured biofilm. A dense, multilayered matrix rich in EPS was observed, with reduced porosity and no exposed electrode surface, indicating robust biofilm establishment. The microstructure appeared cohesive and granular, characteristic of a mature electroactive biofilm capable of efficient electron transfer. Conversely, excessive polarization at 5 V resulted in disrupted morphology. The surface was dominated by filamentous and fibrous structures, with minimal cell-like features and apparent surface damage or detachment. This morphology suggests electrical overstimulation leading to stress, EPS denaturation and structural collapse, consistent with reduced electrochemical performance at high voltages.

3.2. Effects of Microalgal/Cyanobacterial Cathodes on pMFC Performance

3.2.1. Algal Biomass Development and Stability

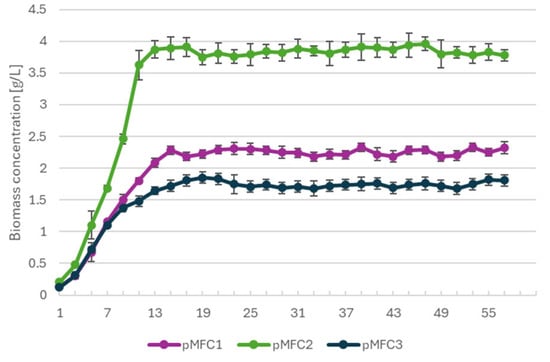

Biomass concentrations in all phototrophic cathodic cultures increased rapidly during the initial 10–12 days of operation and subsequently stabilized at taxon-specific steady-state levels (Figure 3). Arthrospira platensis (pMFC2) exhibited the highest growth performance, reaching 3.8–4.0 g·L−1, which is fully consistent with values commonly reported for batch cultures of this cyanobacterium under nutrient-replete conditions (typically 3–6 g·L−1) [16,17]. Chlorella sp. (pMFC1) stabilized at 2.2–2.4 g·L−1, matching standard biomass yield observed in controlled photobioreactor systems (1.5–3 g·L−1) [18,19]. The marine chlorophyte Tetraselmis subcordiformis (pMFC3) reached a final biomass concentration of 1.7–1.9 g·L−1, which aligns with previously reported ranges for this species cultivated under saline conditions (1.5–2.5 g·L−1) [20,21].

Figure 3.

Biomass concentration profiles of Chlorella sp. (pMFC1), Arthrospira platensis (pMFC2) and Tetraselsmis subcordiformis (pMFC3) during pMFC operation.

The comparable growth kinetics and plateau values across all pMFC variants indicate that the operational conditions within the cathodic chambers did not impose physiological stress capable of suppressing microalgal proliferation. This suggests that the differences observed in electrochemical performance between pMFC are unlikely to result from disparities in phototrophic biomass accumulation, but instead arise from bioelectrochemical interactions and differences in anodic microbial community structure.

3.2.2. Electrochemical Performance of pMFCs

Clear differences in pMFC behavior were observed, demonstrating that the type of photosynthetic microorganism strongly modulates the anodic electroactive community and, consequently, electricity generation (Table 4). Although the anodic and cathodic chambers were separated by a Nafion™ 117 proton-exchange membrane, partial diffusion of gases (O2, CO2) and small ions (H+, Na+, K+) might occur through its hydrated polymeric channels, thereby influencing the redox potential and proton flux of the anodic compartment [22,23,24].

Table 4.

Electrochemical performance parameters of pMFCs operated with Chlorella sp. (pMFC1), Arthrospira platensis (pMFC2), Tetraselmis subcordiformis (pMFC3) and in the MFC control.

pMFC1 exhibited the highest average voltage (0.393 ± 0.064 V) and the highest current density (0.14 ± 0.02 mA·cm−2), resulting in a maximum power density of 552 ± 180 mW·m−2 (Table 4). CE reached 19.2 ± 3.0%, which was nearly double the CE of the non-photosynthetic MFC (11.1 ± 3.0%). Such enhancement is consistent with the improved cathodic oxygen availability provided by microalgal photosynthesis. In the Chlorella sp. pMFC, the neutral pH (6.5–7.5) and high photosynthetic activity could facilitate oxygen evolution at the cathode and CO2 uptake. Under such conditions, the hydrated state of the Nafion™ 117 membrane remains optimal, enabling efficient proton transfer. It could also support partial diffusion of dissolved oxygen across the membrane. This limited oxygen crossover might establish mildly oxidative or microaerobic conditions near the anode surface [25]. Microalgae increase dissolved oxygen and stabilize pH, which enhances the thermodynamics of the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) and improves electron acceptance at the cathode. Similar improvements in pMFC performance due to microalgal oxygen production were previously reported for Chlorella-based cathodes [5], confirming that photosynthetic biocathodes can effectively replace aeration while increasing the energy output of the pMFC. The high power density obtained in this study (≥500 mW·m−2) is comparable to or exceeds the values previously reported for algal-assisted MFCs, which typically range between 50–400 mW·m−2 depending on species, light intensity, and medium composition [26,27].

pMFC2 demonstrated lower voltage (0.276 ± 0.049 V) and current density (0.10 ± 0.02 mA·cm−2) compared with pMFC1 but still outperformed the conventional MFC. The resulting power density (272 ± 97 mW·m−2) and CE (13.4 ± 2.1%) indicate that pMFC2 supported efficient electron transfer but yielded less energy than pMFC1. The Arthrospira platensis pMFC2 operated at highly alkaline conditions (pH > 9) in a carbonate-rich medium containing elevated concentrations of NaHCO3 and Na2CO3. Under these conditions, CO2 availability is extremely low, and the carbonate/bicarbonate equilibrium strongly favors CO32− ions. Furthermore, the presence of high concentrations of Na+ might competes with H+ for sulfonic acid sites in the membrane, significantly reducing proton conductivity [28]. At elevated pH, the Nafion matrix also undergoes partial dehydration, further limiting ion transport [29,30]. As a result, proton transfer was minimized, creating a more isolated anodic environment with lower redox potential and weaker electron transfer efficiency.

In pMFC3, no measurable voltage or current was produced throughout the experiment. The complete absence of current generation in the Tetraselmis subcordiformis pMFC can be explained by physicochemical limitations associated with the high salinity of the catholyte. Marine-type media contain high concentrations of Na+, Cl−, and HCO3−, which dramatically alter ion transport across the proton-exchange membrane [31]. Under such conditions, cation flooding occurs, where Na+ competitively binds to the sulfonic groups of Nafion, displacing H+ and strongly inhibiting proton conductivity. Because pMFC operation requires electron flow through the external circuit and proton transfer through the membrane, disruption of ionic transport could effectively open the circuit and prevent electron flow, regardless of anodic biofilm activity. High salinity simultaneously might reduce oxygen solubility, alters cathodic redox kinetics, and increases ohmic resistance in the electrolyte. These combined effects could fully suppress the ORR and collapse electrochemical activity. Therefore, even without considering biological competition, the physicochemical properties of the T. subcordiformis medium alone are sufficient to explain the absence of electricity generation. Similar inhibitory effects of salinity on proton-exchange membranes and microbial electroactivity have been previously reported [30,32].

The conventional MFC showed lower voltage (0.248 ± 0.053 V), current density (0.09 ± 0.02 mA·cm−2), and power density (220 ± 94 mW·m−2) compared with both pMFC1 and pMFC2. These findings reaffirm that external aeration does not match the efficiency of biologically produced oxygen, which is supplied directly at the electrode–biofilm interface in pMFCs. Additionally, the CE of the MFC (11.1 ± 3.0%) was significantly lower than in pMFC1, indicating that photosynthetic oxygen production increases electron recovery and reduces electron losses to competing anaerobic pathways (e.g., methanogenesis, sulfate reduction) [33].

The physicochemical environment of the cathodic compartment plays a crucial role in shaping anodic biofilm activity in pMFCs. Overall, the chemical composition of the cathodic medium could modulate the physicochemical gradients across the membrane and thus the anodic redox balance. Neutral, hydrated conditions favored moderate oxygen crossover and enhanced electroactive biofilm formation, whereas carbonate-rich or saline media limited proton diffusion, leading to poor electrical performance.

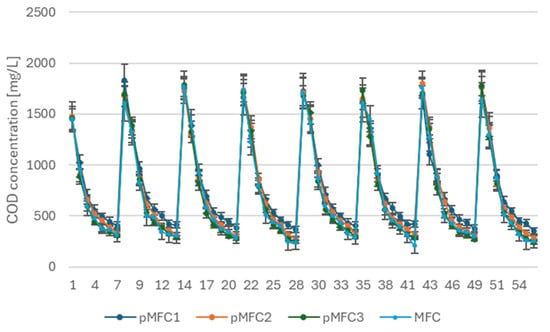

3.2.3. COD Removal in pMFCs Compared to Non-Phototrophic MFC

Figure 4 presents the temporal profiles of COD concentration in the four tested pMFCs across eight consecutive feeding cycles. All configurations exhibited a highly reproducible pattern of COD removal, characterized by a rapid decline in the first 3–4 days of each cycle, followed by gradual stabilization as the substrate became depleted. The initial influent COD concentration (1800 mg∙L−1) was consistently reduced to 300–450 mg∙L−1 at the end of each cycle, regardless of the type of microalgae introduced into the cathodic chamber.

Figure 4.

COD removal in the anodic chambers of pMFCs operated with Chlorella sp. (pMFC1), Arthrospira platensis (pMFC2), Tetraselmis subcordiformis (pMFC3) and in the MFC control.

Importantly, the COD degradation profiles of all pMFC closely mirrored the trend observed in the first stage of the study, in which the anode was stimulated at 1 V prior to operation. This indicates that the introduction of microalgae did not alter the biodegradation kinetics established by the electrically pre-conditioned anodic biofilm. In all variants, the rate of COD removal remained fast and stable, suggesting that the electrogenic community formed during the early stimulation phase retained high metabolic activity and substrate oxidation capacity throughout the entire operational period.

These results align with previous studies showing that once a highly active electroactive biofilm is formed—particularly following anodic polarization—its metabolic performance becomes relatively robust to variations in cathodic configuration [6]. Thus, the primary determinant of COD removal in the present study was the pre-stimulated anodic biofilm, while the presence or absence of microalgae in the cathode had no measurable effect on the degradation kinetics.

3.3. Microbial Community Structure in Anodic Biofilms

3.3.1. Community Composition at the Order Level

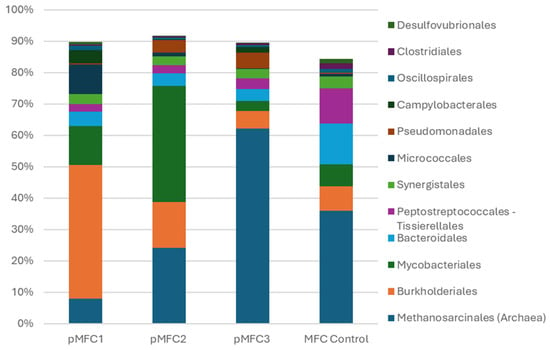

The taxonomic composition of the anodic biofilms differed substantially among the four evaluated pMFCs (Figure 5). Analysis of the 12 most abundant orders revealed distinct community signatures associated with the type of photosynthetic organism present in the cathode.

Figure 5.

Relative abundance of the 12 most dominant bacterial and archaeal orders detected in the anodic biofilms of pMFC operated with different photosynthetic cathodes (Chlorella sp., Arthrospira platensis, Tetraselmis subcordiformis) and a non-photosynthetic control. Bars represent the proportion (%) of each taxonomic order within the total classified reads for a given sample. Orders outside the top-12 were grouped as “Others”.

In the Chlorella sp.–based pMFC, the anodic microbiome was dominated by Burkholderiales (43%), accompanied by moderate proportions of Mycobacteriales, Synergistales, and Campylobacterales. This profile is characteristic of a metabolically versatile, facultatively electroactive community, consistent with the higher electrical activity and suppression of methanogenesis observed in this pMFC. Similar enrichments of Burkholderiales and other facultatively electroactive taxa have been reported in oxygen-tolerant or microaerobic anodes, where limited O2 transfer enhances redox gradients without fully inhibiting anaerobic respiration [34,35]. The presence of only 8% Methanosarcinales further supports the hypothesis that mild oxygen crossover or microaerobic conditions created by Chlorella sp. could inhibited archaeal growth and favored electroactive bacteria—an effect observed in MFCs where trace O2 suppresses aceticlastic methanogenesis [36,37].

In contrast, the Arthrospira platensis pMFC exhibited a markedly different community structure. The anode was dominated by Mycobacteriales (37%), a group often associated with nutrient-rich, alkaline, or stress-adapted environments and previously linked to biofilms in high-pH or carbonate-rich systems [38,39]. The relative abundance of Burkholderiales decreased to 15%, while Methanosarcinales increased to 24%, indicating a shift toward a more mixed, partially methanogenic community. These changes align with the high-carbonate, high-pH chemistry of the Arthrospira medium, which could reduce proton conductivity across the membrane and weakened the selective pressure toward classical electrogens. Alkalinity and carbonate buffering are known to reduce proton mobility in Nafion-type membranes and alter the electrochemical environment of anodic biofilms [28,30].

The most distinct profile was observed in the Tetraselmis subcordiformis pMFC, where Methanosarcinales comprised more than 62% of all classified reads—three to eight times higher than in the other variants. This overwhelming dominance of methanogenic archaea indicates strongly reducing conditions and is consistent with the complete absence of measurable current generation in this configuration. The near-elimination of electroactive or syntrophic orders suggests that the marine catholyte created conditions unfavorable for effective anodic electron transfer processes. In particular, the high salinity and ionic strength of the medium likely impaired transmembrane proton transport, thereby limiting charge balance between the chambers and suppressing sustained electron flow from the anode. As a result, electrons were preferentially diverted to methanogenic pathways rather than extracellular electron transfer. This interpretation is consistent with previous reports demonstrating reduced proton conductivity of Nafion membranes by salt inhibition, which can severely constrain current generation in MFC systems [40,41].

The control MFC, operated without photosynthetic biomass in the cathode, displayed an intermediate profile. Its community was characterized by a mixture of Bacteroidales, Peptostreptococcales–Tissierellales, and Methanosarcinales, resembling a typical anaerobic sludge community with limited selective pressure toward electroactive bacteria. Such communities have been widely reported in unpolarized or weakly polarized anodes [33,42].

In pMFC systems, photosynthetic microorganisms are not expected to directly interact with the anodic biofilm. Instead, their role is proposed to be indirect, mediated through the catholyte physicochemical conditions, including pH, ionic composition, and salinity (Figure S1). These conditions may affect membrane properties such as proton conductivity and oxygen permeability, thereby influencing anodic redox conditions and shaping anodic microbial community structure. Chlorella sp. favored electroactive, oxygen-tolerant taxa; Arthrospira platensis promoted Actinobacteria and moderate methanogenesis; whereas Tetraselmis subcordiformis drove the community toward methanogenic dominance. It should be emphasized that these interactions represent a conceptual framework inferred from literature and system behavior, as membrane transport processes were not directly quantified in this study. Importantly, the similarity across pMFC1, pMFC2, and pMFC3 mentioned in the previous chapter demonstrates that cathodic microalgae exerted minimal influence on the net anodic biodegradation efficiency, even though the pMFCs differed markedly in microbial selection. The strong consistency in COD reduction across all pMFC suggests that oxygen transfer from the cathode was sufficient to maintain comparable redox conditions and that the established anodic biofilm remained the primary driver of organic matter oxidation—consistent with previous observations in pMFCs [43,44].

3.3.2. Alpha-Diversity

The alpha-diversity indices calculated from ASV-level abundance data revealed clear differences in microbial richness and evenness among the four anodic communities (Table 5). Observed ASVs and Chao1 were numerically identical for each sample, indicating sufficiently deep sequencing and low prevalence of rare taxa.

Table 5.

Alpha-diversity indices of anodic microbial communities in pMFCs operated with Chlorella sp. (pMFC1), Arthrospira platensis (pMFC2), Tetraselmis subcordiformis (pMFC3) and in the MFC control. The table includes the number of observed ASVs (Sobs), Shannon diversity (H’), Simpson diversity (1–D), Chao1 richness estimator and community evenness (J), showing clear differences in richness, diversity and distribution uniformity across the pMFC.

The Chlorella-based anode showed a moderate observed richness (Sobs = 112 ASVs), coupled with relatively high Shannon (H′ = 2.30) and Simpson (1–D = 0.782) indices, indicating a balanced community structure with no extreme dominance of individual taxa. This profile reflects a metabolically diverse, functionally resilient biofilm consistent with the presence of multiple facultative electroactive lineages identified in the taxonomic analysis. The Arthrospira pMFC exhibited slightly lower richness (Sobs = 100 ASVs) and diversity (H′ = 2.09), along with reduced evenness (J = 0.454). These values suggest a more specialized or uneven community structure, in which a limited number of taxa—particularly Actinobacteria (Mycobacteriales)—dominated the biofilm. The community remained moderately diverse but exhibited signs of functional narrowing relative to the Chlorella pMFC. In sharp contrast, the Tetraselmis-based anode demonstrated the lowest Shannon (1.87) and Simpson (0.602) indices, despite having comparatively high observed richness (Sobs = 125 ASVs). The markedly low evenness (J = 0.387) indicates strong dominance by a single group—methanogenic Methanosarcinales—consistent with metagenomic and electrochemical data showing a shift toward a highly reducing, methanogenesis-driven community and the absence of measurable current production in this pMFC. The control anode displayed the highest overall diversity (H′ = 2.52; 1–D = 0.828) and richness (Sobs = 129 ASVs), with relatively uniform distribution across taxa (J = 0.519).

Collectively, the alpha-diversity metrics demonstrate that cathodic conditions indirectly modulated the ecological structure of anodic biofilms. The Chlorella pMFC supported a well-balanced, electroactive community; Arthrospira promoted moderately diverse but taxonomically skewed assemblages; Tetraselmis induced severe community imbalance driven by methanogenic dominance; whereas the control maintained the highest richness without selective pressure toward electroactive taxa. These results complement the taxonomic and electrochemical analyses, indicating that cathodic medium chemistry could be a key driver of microbial community organization in pMFCs.

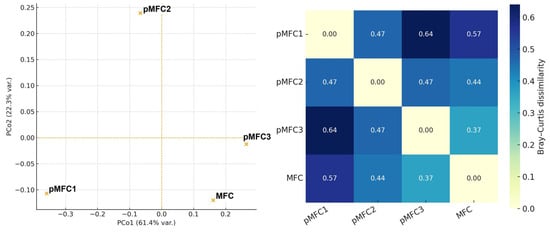

3.3.3. Beta-Diversity (PCoA)

Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarity indicated differences in anodic microbial communities depending on the cathodic configuration (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

PCoA based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarity and the corresponding heatmap of pairwise dissimilarities illustrating the beta-diversity patterns of anodic microbial communities across pMFC variants.

The analysis shows visual separation of pMFC1 (Chlorella sp.) and the MFC control, while pMFC2 (Arthrospira platensis) and pMFC3 (Tetraselmis subcordiformis) form groups, indicating substantial shifts in community structure driven by cathodic photosynthetic activity. The anode associated with Chlorella sp. formed a separated cluster, indicating a unique microbial composition compared to the other variants. Samples from Arthrospira platensis and the control MFC showed partial overlap, suggesting a similar structure dominated by Actinobacteria and fermentative taxa. In contrast, the Tetraselmis subcordiformis pMFC displayed the most divergent profile, characterized by a dominance of methanogenic archaea (Methanosarcinales), resulting in a reduced microbial diversity.

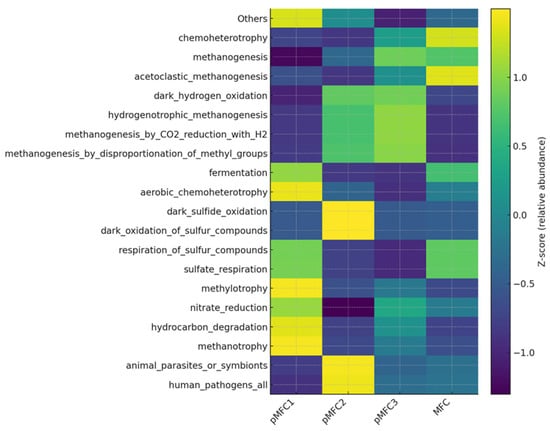

3.4. Functional Metabolic Potential of Anodic Biofilms

3.4.1. Relative Abundance of Functional Categories

Functional prediction based on taxonomic profiles revealed profound differences in metabolic potential between the anodic biofilms formed in the four pMFC configurations (Figure 7). FAPROTAX predictions reflect taxon-associated functional traits rather than measured metabolic activity and should therefore be interpreted as potential rather than actual pathway flux. Functions attributed to ‘aerobic chemoheterotrophy’ often represent facultative anaerobes capable of anoxic metabolism in MFC environments.

Figure 7.

Heatmap showing the Z-score standardized relative abundance of the 20 most abundant predicted metabolic functions in anodic microbial communities across pMFC variants.

The most striking pattern was observed in the Tetraselmis-driven pMFC, where all methanogenic pathways—acetoclastic, hydrogenotrophic, and methylotrophic—showed markedly elevated predicted activity. Total methanogenesis reached the highest value among all variants, with especially strong contributions from CO2-reducing and hydrogenotrophic routes. Such a functional profile indicates that in the presence of Tetraselmis subcordiformis medium as a catholyte, the anodic biofilm becomes strongly oriented toward electron-consuming methanogenic metabolism rather than EET. This aligns with the experimental observation that the Tetraselmis pMFC did not generate measurable current. The preferential diversion of electrons into CH4 formation is consistent with earlier reports that hydrogenotrophic and methylotrophic methanogens effectively outcompete electroactive bacteria under conditions of high electron donor availability but weak anodic coupling [33,42].

In contrast, the pMFC1 inoculated with Chlorella sp. demonstrated the lowest predicted methanogenic potential and a functional repertoire dominated by moderate heterotrophy and fermentation, without pronounced enrichment of syntrophic hydrogen cycling. This metabolic structure is more compatible with stable anodic respiration and correlates with the superior electrochemical performance of this pMFC. Previous studies have shown that suppression of methanogenic pathways—particularly hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis—improves EET efficiency by reducing competition for electron donors and favoring electroactive lineages such as Geobacter spp. [33,45]. The functional profile of pMFC1 is therefore indicative of a more electroactive and less electron-dissipative microbial consortium.

The Arthrospira platensis pMFC2 exhibited a distinct functional signature characterized by elevated dark hydrogen oxidation and pronounced enrichment of bacteria involved in sulfide and sulfur compound oxidation. These functions are typical for oxidative, high-pH microenvironments and may reflect the alkaline carbonate-rich medium used for Arthrospira platensis. The increased potential for sulfur oxidation has previously been associated with microaerophilic or redox-flexible taxa such as Thiobacillus spp. and other chemolithoautotrophs, which can coexist with fermenters and hydrogen consumers but do not necessarily support efficient EET [46]. The intermediate electrochemical performance of pMFC2 suggests that although hydrogen metabolism was active, a substantial fraction of electrons may have circulated through internal oxidation–reduction loops rather than being transferred to the anode.

The non-phototrophic control MFC displayed a functional structure indicative of a typical anaerobic digestion community, with strong acetoclastic methanogenesis, high chemoheterotrophy, and moderate nitrogen fixation. This metabolic profile reflects a biofilm that largely relies on classical anaerobic respiration and fermentation rather than electroactive processes. The combination of high acetoclastic methanogenic potential and limited syntrophic hydrogen turnover suggests that the anodic biofilm behaved similarly to a conventional anaerobic reactor rather than a bioelectrochemical system, which is consistent with its lower current output. Comparable findings have been reported in MFCs operating without phototrophic or redox-active partners, where methanogens dominate carbon and electron flow, thereby reducing CE [33,47].

Overall, the functional prediction results demonstrate that the medium of phototrophic species can exert a strong, system-wide influence on the metabolic trajectory of anodic microbiomes. These trends emphasize that the choice of phototrophic partner in pMFCs may not only modulate oxygen and carbon fluxes but also fundamentally reshape microbial electron-use pathways, thereby controlling the balance among methanogenesis, fermentation, and EET.

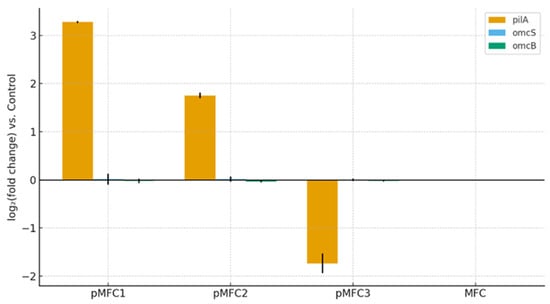

3.4.2. Relative Quantitative PCR

Quantitative PCR analysis performed on genomic DNA revealed marked differences in the abundance of EET-related genes among the pMFC variants (Figure 8). Gene abundances were normalized to total genomic DNA input because housekeeping genes are unsuitable in complex mixed-culture communities lacking universal reference markers.

Figure 8.

Relative abundance of EET genes (pilA, omcS and omcB) in anodic biofilms of pMFC, quantified by qPCR from genomic DNA and expressed as log2 fold change relative to the MFC control.

The pilA gene, encoding the structural subunit of type IV pili involved in long-range electron transport, showed a strong positive enrichment in the Chlorella-based pMFC, with an average log2 (fold change) +3.2 relative to the MFC control. The Arthrospira platensis pMFC2 displayed a moderate but still positive enrichment (log2+1.7), whereas the Tetraselmis subcordiformis pMFC3 exhibited a pronounced depletion of pilA (log2−1.8). In contrast, the cytochrome c-encoding genes omcS and omcB, typically associated with direct electron transfer in Geobacter sulfurreducens, showed no meaningful changes across any variant (log20), indicating that these classical EET pathways were not substantially represented in the anodic communities.

These patterns are fully consistent with the taxonomic and functional profiles obtained in this study. The strong increase in pilA abundance in pMFC1 aligns with the enrichment of facultative heterotrophs capable of forming pili-associated conductive biofilms and mediating indirect or shuttle-based electron transfer pathways, as widely documented for non-Geobacter electrogens such as Pseudomonas, Comamonas and Aeromonas [48]. The lack of omc-type cytochromes is not unexpected, as these genes are highly specific to Geobacteraceae, which were virtually absent from all anodic communities. Similar observations have been reported in mixed-culture MFCs where electrogenesis is driven predominantly by pilin-producing facultative anaerobes rather than canonical metal-reducing bacteria [49].

The strong depletion of pilA in pMFC3 (Tetraselmis subcordiformis) is particularly notable and mechanistically coherent with the absence of measurable current production in this pMFC. High-salinity catholyte associated with Tetraselmis subcordiformis cultivation likely imposed selective pressure favoring fermentative and methanogenic taxa while suppressing electrogenic biofilm formers, consistent with the very high methanogenic functional potential detected in this variant. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that cathodic microalgal physiology exerts a top–down selective effect on anodic EET gene potential, and that Chlorella sp.-based pMFC are the most favorable for enriching pilA-associated electroactive communities under the tested conditions.

3.5. Study Limitations and Future Research Directions

Due to the short experimental duration, the long-term stability of electrically stimulated electroactive biofilms could not be assessed. The effects of prolonged electrical stimulation on biofilm resilience, community structure, and electrochemical performance remain uncertain and require dedicated long-term studies. The findings of this study indicate that electrical stimulation can influence early-stage biofilm development and microbial community structure in pMFC systems, providing a potential tool for controlled start-up and microbial pre-enrichment. From a practical perspective, such an approach may be particularly relevant for laboratory-scale or modular systems where rapid establishment of electroactive communities is desirable. Future studies should focus on long-term operation, system stability, and energy balance to better assess the applicability of electrical stimulation under realistic operational conditions.

4. Conclusions

This study shows that both anodic electrical stimulation and the choice of photosynthetic microorganism at the cathode play decisive roles in shaping the electrochemical efficiency and microbial ecology of pMFCs. The following conclusions can be drawn:

- Short-term anodic stimulation strongly accelerates electroactive biofilm formation. Among the tested voltages, 1 V provided optimal activation, significantly improving start-up behavior, voltage output, power density and COD removal kinetics, while 5 V impaired biofilm integrity and system performance.

- SEM confirmed stimulation-dependent biofilm morphology. Dense, cohesive electroactive structures formed at 1 V, whereas high-voltage stimulation produced damaged, filamentous and sparsely colonized surfaces.

- Photosynthetic cathodes exert strong, species-specific effects on system performance. Chlorella sp. produced the highest voltage, current density and CE; Arthrospira platensis showed intermediate performance; Tetraselmis subcordiformis generated no current due to inhibitory saline conditions.

- Cathodic physiology reshapes anodic microbial communities. Chlorella sp. enriched facultative electroactive taxa and suppressed methanogenesis; Arthrospira platensis favored Actinobacteria and sulfur-oxidizing bacteria; Tetraselmis subcordiformis induced a methanogenesis-dominated biofilm incompatible with EET.

- Functional prediction and qPCR confirm shifts in electron-use pathways. Chlorella sp. increased the abundance of the EET marker gene pilA, while cytochrome-based pathways (omcS/omcB) remained minimal in all variants. Tetraselmis subcordiformis strongly increased all methanogenic pathways, redirecting electrons away from the anode.

- Synergy between 1 V stimulation and Chlorella sp. biocathodes provides the most electroactive configuration. This combination suppresses electron-dissipating processes (methanogenesis), supports redox-balanced conditions and enhances CE.

- Cathodic microalgae therefore function as top–down ecological selectors, modulating anodic redox gradients, metabolic potential and biofilm electroactivity through cross-chamber chemical and electrochemical coupling.

- The synergy between anodic stimulation and phototrophic oxygen production may facilitate fast establishment of conductive biofilms by balancing redox gradients and reducing competitive electron sinks.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/en19010041/s1, Figure S1: Conceptual schematic illustrating the proposed indirect cross-chamber coupling mechanism in pMFCs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.R. and M.Z.; Methodology, P.R.; Software, P.R.; Formal analysis, P.R. and Ł.B.; Investigation, P.R., Ł.B., A.S. and K.G.; Resources, P.R.; Data curation, P.R., Ł.B. and M.Z.; Writing—original draft, P.R. and M.Z.; Writing—review & editing, M.D.; Visualization, P.R.; Supervision, P.R. and M.Z.; Project administration, P.R.; Funding acquisition, M.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financed by the Polish National Science Center (Grant Number 2021/41/B/NZ9/02225).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Logan, B.E. Microbial Fuel Cells; Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kannan, N.; Donnellan, P. Algae-Assisted Microbial Fuel Cells: A Practical Overview. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2021, 15, 100747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Don, C.D.Y.A.; Babel, S. Comparing the Performance of Microbial Fuel Cell with Mechanical Aeration and Photosynthetic Aeration in the Cathode Chamber. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 16751–16761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Hsu, L.H.; Kavanagh, P.; Barrière, F.; Lens, P.N.L.; Lapinsonnière, L.; Lienhard, V.J.H.; Schröder, U.; Jiang, X.; Leech, D. The Ins and Outs of Microorganism–Electrode Electron Transfer Reactions. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2017, 1, 0024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieliński, M.; Rusanowska, P.; Dudek, M.; Starowicz, A.; Barczak, Ł.; Dębowski, M. Efficiency of Photosynthetic Microbial Fuel Cells (pMFC) Depending on the Type of Microorganisms Inhabiting the Cathode Chamber. Energies 2024, 17, 2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, B.E.; Rossi, R.; Ragab, A.; Saikaly, P.E. Electroactive Microorganisms in Bioelectrochemical Systems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thamaraiselvan, C.; Ronen, A.; Lerman, S.; Balaish, M.; Ein-Eli, Y.; Dosoretz, C.G. Low Voltage Electric Potential as a Driving Force to Hinder Biofouling in Self-Supporting Carbon Nanotube Membranes. Water Res. 2018, 129, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, Y.; Yoon, H.; Shim, S.; Choi, J.; Yoon, J. Electroconductive Feed Spacer as a Tool for Biofouling Control in a Membrane System for Water Treatment. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2014, 1, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Cheng, S.; Zhang, F.; Logan, B.E. Current Density Reversibly Alters Metabolic Spatial Structure of Exoelectrogenic Anode Biofilms. J. Power Sources 2017, 356, 566–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Wu, X.; Miller, C.; Zhu, J. Improved Performance of Microbial Fuel Cells Enriched with Natural Microbial Inocula and Treated by Electrical Current. Biomass Bioenergy 2013, 54, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.; Kim, J.Y.; Yoon, J. The Role of Reactive Oxygen Species in the Electrochemical Inactivation of Microorganisms. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 6117–6122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsanti, L.; Gualtieri, P. Algae: Anatomy, Biochemistry, and Biotechnology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, K.J.; Esteve-Núñez, A.; Leang, C.; Lovley, D.R. Direct Correlation between Rates of Anaerobic Respiration and Levels of mRNA for Key Respiratory Genes in Geobacter sulfurreducens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 5183–5189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Tang, J.; Yuan, Y.; Yang, G.; Xing, B. TiO2 Nanoparticle-Induced Nanowire Formation Facilitates Extracellular Electron Transfer. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2018, 5, 564–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCt Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.S.; Ferreira, L.S.; Converti, A.; Sato, S.; Carvalho, J.C.M. Fed-Batch Cultivation of Arthrospira (Spirulina) platensis: Potassium Nitrate and Ammonium Chloride as Simultaneous Nitrogen Sources. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 4491–4498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavianghavanini, A.; Shayesteh, H.; Bahri, P.A.; Vadiveloo, A.; Moheimani, N.R. Microalgae Cultivation for Treating Agricultural Effluent and Producing Value-Added Products. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 169369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.F.; Wang, C.C.; Taidi, B. Effective CO2 Capture by the Fed-Batch Culture of Chlorella vulgaris. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 110889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlov, V.A.; Grigorenko, A.V.; Astafieva, A.P.; Vlaskin, M.S. Growth of Chlorella vulgaris under Atmospheric CO2 in Lab-Scale Photobioreactors: Effects of Aeration Rate and Growth Model Comparison. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek, M.; Dębowski, M.; Nowicka, A.; Kazimierowicz, J.; Zieliński, M. The Effect of Autotrophic Cultivation of Platymonas subcordiformis in Waters from the Natural Aquatic Reservoir on Hydrogen Yield. Resources 2022, 11, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.H.; Ai, J.N.; Cao, X.P.; Xue, S. Characterization of Cell Growth and Starch Production in the Marine Green Microalga Tetraselmis subcordiformis under Extracellular Phosphorus-Deprived and Sequentially Phosphorus-Replete Conditions. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 97, 6099–6110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sethuraman, V.A.; Khan, S.; Jur, J.S.; Haug, A.T.; Weidner, J.W. Measuring Oxygen, Carbon Monoxide and Hydrogen Sulfide Diffusion Coefficients and Solubility in Nafion Membranes. Electrochim. Acta 2011, 54, 6850–6860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Song, B.Y.; Li, M.J.; Li, X.Y. Oxygen Diffusion in Cation-Form Nafion Membrane of Microbial Fuel Cells. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 276, 268–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Nava, J.; Martínez-Castrejón, M.; García-Mesino, R.L.; López-Díaz, J.A.; Talavera-Mendoza, O.; Sarmiento-Villagrana, A.; Rojano, F.; Hernández-Flores, G. The Implications of Membranes Used as Separators in Microbial Fuel Cells. Membranes 2021, 11, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baik, K.D.; Hong, B.K.; Kim, M.S. Novel Technique for Measuring Oxygen Crossover through the Membrane in Polymer Electrolyte Membrane Fuel Cells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 8927–8933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.K.; Nayak, S.K.; Acharya, B.C.; Mishra, B.K. Algal-Assisted Microbial Fuel Cell for Wastewater Treatment and Bioelectricity Generation. Energy Sources A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2014, 37, 127–133. [Google Scholar]

- Bazdar, E.; Roshandel, R.; Yaghmaei, S.; Mardanpour, M.M. The Effect of Different Light Intensities and Light/Dark Regimes on the Performance of Photosynthetic Microalgae Microbial Fuel Cell. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 261, 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhav, D.; Wang, J.; Keloth, R.; Mus, J.; Buysschaert, F.; Vandeginste, V. A Review of Proton Exchange Membrane Degradation Pathways, Mechanisms, and Mitigation Strategies in a Fuel Cell. Energies 2024, 17, 998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foniok, K.; Drozdova, L.; Prokop, L.; Krupa, F.; Kedron, P.; Blazek, V. Mechanisms and Modelling of Effects on the Degradation Processes of a Proton Exchange Membrane (PEM) Fuel Cell: A Comprehensive Review. Energies 2025, 18, 2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, X.; Zhao, X.; Li, Y. Factors Affecting the Efficiency of a Bioelectrochemical System: A Review. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 19748–19761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, R.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, F.; Wang, H.; Bi, C.; Yu, C.; Zhou, Y. Effect of Cations (Na+, Co2+, Fe3+) Contamination in Nafion Membrane: A Molecular Simulations Study. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 50, 635–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, B.E.; Regan, J.M. Microbial Fuel Cells—Challenges and Applications. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 5172–5180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, D.; Chakraborty, I.; Ghangrekar, M.M. Methanogenesis Inhibitors Used in Bio-Electrochemical Systems: A Review Revealing Reality to Decide Future Direction and Applications. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 319, 124141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.C.; Coppi, M.V.; Lovley, D.R. Geobacter sulfurreducens Can Grow with Oxygen as a Terminal Electron Acceptor. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 2525–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speers, A.M.; Reguera, G. Competitive Advantage of Oxygen-Tolerant Bioanodes of Geobacter sulfurreducens in Bioelectrochemical Systems. Biofilm 2021, 3, 100052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Conrad, R.; Lu, Y. Responses of Methanogenic Archaeal Community to Oxygen Exposure in Rice Field Soil. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2009, 1, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, S.; Regan, J.M. Comparison of Anode Bacterial Communities and Performance in Microbial Fuel Cells with Different Electron Donors. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 77, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, X.; Guo, F.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H. Enhancing the Electricity Generation and Nitrate Removal of Microbial Fuel Cells with a Novel Denitrifying Exoelectrogenic Strain EB-1. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widera, B.; Tyszkiewicz, N.; Truu, J.; Rutkowski, P.; Młynarz, P.; Pasternak, G. Relationship between Biodiversity and Power Generated by Anodic Bacteria Enriched from Petroleum-Contaminated Soil at Various Potentials. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2024, 194, 105849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkola, M.S.; Rockward, T.; Uribe, F.A.; Pivovar, B.S. The Effect of NaCl in the Cathode Air Stream on PEMFC Performance. Fuel Cells 2007, 7, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhav, D.; Shao, C.; Mus, J.; Buysschaert, F.; Vandeginste, V. The Effect of Salty Environments on the Degradation Behavior and Mechanical Properties of Nafion Membranes. Energies 2023, 16, 2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.; Boghani, H.C.; Michie, I.; Dinsdale, R.M.; Guwy, A.J.; Premier, G.C. Inhibition of Methane Production in Microbial Fuel Cells: Operating Strategies Which Select Electrogens over Methanogens. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 173, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, J.; Arkatkar, A. Anodic Catalyst and Mediators for Tailoring the Biochemical Behaviour of Microbial Fuel Cell System. Discov. Electrochem. 2025, 2, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, K.J.; Choi, M.; Ajayi, F.F.; Park, W.; Chang, I.S.; Kim, I.S. Mass Transport through a Proton Exchange Membrane (Nafion) in Microbial Fuel Cells. Energy Fuels 2008, 22, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, B. Exoelectrogenic Bacteria That Power Microbial Fuel Cells. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 7, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedrich, C.G.; Rother, D.; Bardischewsky, F.; Quentmeier, A.; Fischer, J. Oxidation of Reduced Inorganic Sulfur Compounds by Bacteria: Emergence of a Common Mechanism? Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001, 67, 2873–2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; ter Heijne, A.; Rijnaarts, H.; Chen, W.S. The Effect of Anode Potential on Electrogenesis, Methanogenesis and Sulfidogenesis in a Simulated Sewer Condition. Water Res. 2022, 226, 119229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, D.; Adhikari, R.; Holmes, D.; Ward, J.E.; Woodard, T.L.; Nevin, K.P.; Lovley, D.R. Electrically Conductive Pili from Pilin Genes of Phylogenetically Diverse Microorganisms. ISME J. 2018, 12, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Leang, C.; Ding, Y.R.; Glaven, R.H.; Coppi, M.V.; Lovley, D.R. OmcF, a Putative c-Type Monoheme Outer Membrane Cytochrome Required for the Expression of Other Outer Membrane Cytochromes in Geobacter sulfurreducens. J. Bacteriol. 2005, 187, 4505–4513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.