Abstract

Biomass gasification serves as a key carbon-neutral technology. To effectively address the challenge of tar treatment during biomass gasification, the National Institute of Clean and low-carbon Energy developed a fluidized bed coupled with an entrained-flow bed. A steady-state Aspen Plus V12 model was designed to assess the compatibility between the two beds and optimize operating parameters. The model divides the process into three main zones: fluidized bed gasification, entrained-flow bed gasification, and bottom slag treatment, employing a reaction-restricted equilibrium assumption. Simulation results indicate that an increase in pressure leads to a reduction in the concentration of syngas components (CO and H2), an insignificant rise in gas low heating value (LHV), and a notable decline in cold gas efficiency (η). A higher equivalence ratio (ER) results in decreased syngas components, along with a significant reduction in both LHV and η. The introduction of carbon dioxide reduces syngas components and lowers LHV. Similarly, the addition of steam reduces the CO content of the syngas and decreases its LHV. When the fluidized bed temperature exceeds 900 °C, changes in LHV and gas yield become negligible, while variations remain minimal when the entrained-flow bed temperature exceeds 1200 °C.

1. Introduction

As a carbon-neutral energy source, the development and use of biomass helps reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Biomass resources are widely available and include agricultural waste, forestry residues, and urban organic waste. The rational use of these resources can not only alleviate energy supply pressures but also promote the establishment of a renewable energy system. Among various utilization methods, biomass gasification technology has attracted significant attention for its clean, efficient characteristics. This technology converts biomass into syngas, primarily composed of hydrogen and carbon monoxide, achieving efficient energy conversion. Compared to direct combustion, the gasification process offers higher energy conversion efficiency and lower pollutant emissions, making it more environmentally friendly.

However, tar treatment during biomass gasification has always been a technical challenge. To address this issue, the National Institute of Clean-and-low-carbon Energy has developed a fluidized bed coupled with an entrained-flow bed gasification process: first, biomass is gasified in a fluidized bed at a relatively low temperature, and then the tar is cracked in the high-temperature stage of the entrained-flow bed, with the residual carbon being recirculated back into the gasifier, thereby improving carbon conversion and overall gasification efficiency. Currently, experimental studies on the impact of process parameters on gasification performance typically require significant investments in manpower, material, and financial resources, along with certain safety risks. Therefore, establishing accurate mathematical models to reveal the intrinsic mechanisms of biomass gasification is significant.

Researchers have conducted extensive simulation studies on the biomass gasification process. Kartal et al. [1] found that the optimal temperature range for gasifying agricultural and livestock waste in a bubbling fluidized bed was 700–800 °C, with a steam-to-biomass ratio of 0.2–0.3. Kaushal et al. [2] improved prediction accuracy by introducing tar formation and cracking reactions into their model. Hoo et al. [3], in their simulation of empty fruit bunch air gasification, adjusted homogeneous reactions to address the overestimation of CO and H2 yields and the underestimation of CH4 yields in equilibrium models. Under conditions of 1000 °C, an equivalence ratio (ER) of 0.15, and a particle size distribution (PSD) of <0.3 mm, they achieved a syngas heating value of 11.11 MJ/Nm3. Jadoon et al. [4] found that the restricted thermodynamic model had higher prediction accuracy compared to thermodynamic equilibrium and kinetic models. Mahapatro et al. [5] further pointed out that when pressure increased from 1 bar to 4 bar, CH4 concentration rose to 4%, H2 concentration remained largely unchanged, while gas heating value, carbon conversion rate, and cold gas efficiency all improved.

Gao et al. [6] found that gas recirculation effectively reduced CO2 emissions during pine sawdust gasification and improved syngas quality. Fan et al. [7] optimized an 8 t/h biomass gasification system and determined the temperature of 800–900 °C and an equivalence ratio of 0.15–0.2. Shi et al. [8] coupled a machine learning model with Aspen to successfully simulate biomass fast pyrolysis, expanding the model’s applicability to different feedstocks and gasification conditions. Castro et al. [9] developed a dual-fluidized-bed Aspen model incorporating detailed pyrolysis mechanisms, significantly improving the prediction accuracy of pyrolysis products and tar. De et al. [10] simulated the air gasification process of peanut shell powder, achieving an H2 content of 17.33% and a gas yield of 2.61 Nm3/kg. Hoo et al. [11] also simplified the tar model compounds as the m-cresol and heptane, achieving high methane yields at 750 °C. Pauls et al. [12] comprehensively considered the effects of temperature on pyrolysis, hydrodynamic behavior, tar decomposition, and reaction kinetics in their model. Puig-Gamero et al. [13] divided the bubbling fluidized bed into three zones: pyrolysis, combustion, and reduction, and successfully simulated the gasification behavior of four types of biomass by modifying kinetic parameters. Nikoo et al. [14] further introduced a hydrodynamic model, combining plug flow and perfectly mixed reactors, and found that high temperature and ER favored carbon conversion, while particle size had a relatively minor impact.

Yang et al. [15] reported that oxygen-steam gasification showed better performance than air, oxygen, and air-steam gasification methods in terms of hydrogen yield and content. Under conditions of 900 °C, ER of 0.28, and a steam-to-biomass ratio of 0.6, the hydrogen content reached 56%, with a yield of 126 g/kg. Liu et al. [16] analyzed the effects of pressure, feedstock type, and moisture content, concluding that biomass with high carbon content, low ash content, and moisture content below 8% is more likely to yield high-quality syngas. Si et al. [17] constructed a dual-fluidized bed system using recirculated syngas as the gasifying agent and investigated the effects of the gasifying agent and moisture content on gasification efficiency. Wang et al. [18] used Aspen to simulate a four-fluidized bed system integrating gasification, CO2 capture, and chemical looping oxygen production, achieving an optimized cold gas efficiency of 60% and a CO2 capture rate of 70%. A large number of experiments have been also conducted [9,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. Recently, Hashemisohi et al. [28] proposed a new CFD model integrated with reduced-order kinetics to simultaneously simulate tar formation and syngas composition, particularly the localized generation profiles of H2, CO, CO2, and CH4. Wang et al. [29] developed a reactor network model capable of predicting real-time gasification performance, which enabled them to achieve a high hydrogen yield of 1.85 kmol/h while enhancing carbon conversion efficiency. Kuttin et al. [30] adopted a two-dimensional Eulerian CFD framework to quantify the impact of pellet size and moisture content on key outputs, including gas composition, lower heating value, and temperature distribution within the reactor.The innovation of this work lies in:

- To model the complex gasification process, the well-established Restricted Chemical Equilibrium approach was employed using the RGIBBS reactors in Aspen Plus V12. This method is particularly useful for approximating kinetically limited systems. In this work, it was calibrated and applied to the novel coupled-bed configuration to enable a systematic analysis of parameter interactions. The novelty of the study, therefore, stems from the new insights into the operation and optimization of this specific process, rather than from the thermodynamic method itself.

- System-Specific Parameter Interaction and Matching: While the concepts of staging and equilibrium modeling are established, this work aims to provide the first model-based, quantitative answers to the following open questions for the FB-EFB configuration: (1) What is the optimal distribution of oxygen between the beds? (2) At what temperatures do further increases yield negligible benefits? This study thereby delivers novel, actionable insights for the design and operation of this specific advanced gasification system. The core novelty is the investigation of the “matching relationship” and interaction between the two reactors. The manuscript systematically analyzes how operating parameters (like the oxygen distribution ratio between the beds) uniquely affect the overall system performance, which is a critical design and operational consideration not explored in conventional single-reactor or similar dual-bed systems. The finding that the entrained-flow bed is significantly more sensitive to the oxygen distribution ratio than the fluidized bed provides crucial new insights for optimizing this specific configuration. This study aims to establish an accurate process model using Aspen Plus to systematically investigate the effects of pressure, equivalence ratio (ER), CO2/biomass ratio, H2O/biomass ratio, oxygen distribution ratio, fluidized bed gasification temperature, and entrained-flow bed gasification temperature, tar conversion efficiency on gas composition, gas yield, gas low heating value (LHV), and cold gas efficiency. This will reveal the intrinsic mechanisms, determine the optimal parameter range, and thereby provide direct guidance for the efficient design and operational control strategies of industrial-scale gasification units.

2. Experiment and Model

2.1. Experiment

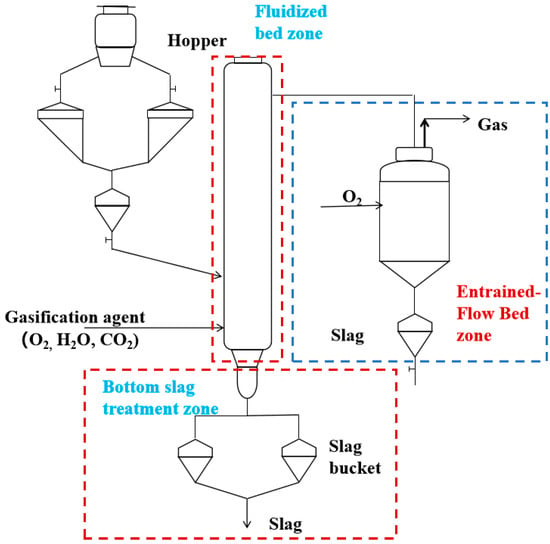

Figure 1 shows the flow diagram of the adopted experimental system for fluidized bed coupled with entrained-flow bed biomass gasification. This flow structure also serves as the basis for constructing the Aspen Plus model.

Figure 1.

Experimental process for biomass gasification in a fluidized bed coupled with an entrained-flow bed.

The specific process is as follows: biomass feedstock is precisely fed from the hopper into the fluidized bed gasifier via a screw feeder; simultaneously, gasifying agents such as oxygen, carbon dioxide, and steam are introduced into the gasifier. The slag generated at the bottom of the fluidized bed is partially discharged as waste and partially recirculated back into the furnace to enhance the gasification performance. The raw syngas and tar produced from the fluidized bed then enter the entrained-flow bed reactor, where secondary reactions such as tar cracking occur, and the final separation of ash and product gas is achieved. The proximate and ultimate analyses of the biomass used in the experiment are listed in Table 1, while the key simulation parameters and equipment operating conditions are summarized in Table 2.

Table 1.

Proximate and ultimate analyses of biomass.

Table 2.

The simulated equipment parameters and operating conditions of biomass gasification.

2.2. Model Establishment

2.2.1. Model Assumptions

To effectively simulate the complex biomass gasification process, the following fundamental assumptions are adopted during modeling:

- (1)

- The process operates under steady-state conditions, with the system maintaining constant temperature and pressure.

- (2)

- The assumption of instantaneous pyrolysis, while a simplification, is adopted as it is computationally efficient and appropriate for a steady-state equilibrium model focused on the final gasification products (H2, CO, CO2, CH4, and H2O) rather than transient pyrolysis kinetics. Given the high operating temperatures (≥800 °C) and the turbulent environment of the fluidized bed, the characteristic devolatilization time for the biomass particles is considered short compared to their residence time, making this a reasonable first-order approximation Tar is generated in the fluidized bed via the RYield block but does not react, with its yield proportional to the carbon content of the fed biomass. Tar is modeled to be partly cracked (ηtar) into H2, O2, N2, and Cin the high-temperature entrained-flow bed simulated by the RYield reactor. These effects were further conducted in the support information. This represents an ideal scenario and is justified by the design purpose of this stage, which is to achieve near-complete tar conversion at temperatures exceeding 1200 °C. This assumption allows the model to focus on the gas-phase equilibrium and provides an optimistic benchmark for syngas quality, though it may lead to a slight over-prediction of light gas yields compared to an actual system with trace residual tar.

- (3)

- Most elements entering into the gas phase, including C, H, O, N, S, and Cl, some unconverted (e.g., C) ones were entered into solid (slag) or tar. Ash is considered inert and does not participate in reactions, neglecting the catalytic effects of alkali and alkaline earth metals in ash.

- (4)

- The heat loss of the gasifier is set to 5% of the lower heating value (LHV) of the biomass, an estimate based on values reported for similar industrial-scale, insulated fluidized-bed gasifiers [5,13]. While this value is fixed for simplicity, it provides a realistic and consistent basis for evaluating the energy balance across all simulated cases. These values were further modified according to the real operation data.

- (5)

- Key reactions involved in the gasification process (including the steam gasification reaction C + H2O→CO + H2, the carbon dioxide reduction reaction C + CO2 → 2CO, and the water-gas shift reaction CO + H2O ⇌ CO2 + H2) all reach thermodynamic equilibrium;

- (6)

- The particle size is assumed constant, which is a simplification that neglects fragmentation and attrition with particle size distribution. This is deemed acceptable because the core of the model relies on thermodynamic equilibrium in the RGibbs blocks, which are not directly dependent on particle size. This assumption allows the model to focus on chemical equilibrium without the added complexity of evolving particle properties. The neglect of internal and external diffusion limitations aligns with the equilibrium modeling framework, which prioritizes thermodynamic limits over kinetic constraints. This is a standard approach for preliminary screening and optimization studies. It is acknowledged that this may lead to optimistic predictions of carbon conversion, particularly for larger biomass particles, but it is considered acceptable for a system-level analysis aimed at identifying overarching trends.

2.2.2. Aspen Model

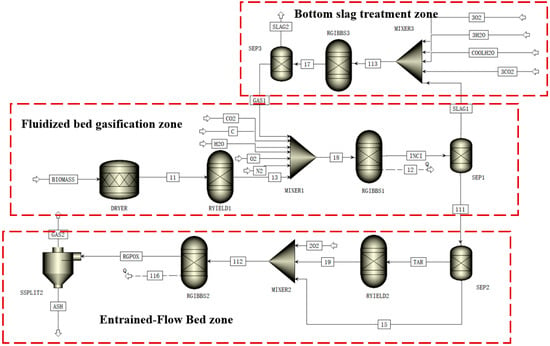

In Aspen Plus, biomass, ash, and tar are defined as non-conventional components, with their properties configured using the density (DCOALIGT) model and enthalpy (HCOALGEN) model. The thermodynamic properties of conventional components involved in the process are calculated using the SRK equation. Figure 2 illustrates the flow diagram of the established Aspen equilibrium model for biomass gasification. The overall process can be divided into three main sections: fluidized bed gasification, entrained-flow bed gasification, and bottom slag treatment. The specific construction scheme is as follows:

Figure 2.

Aspen of biomass gasification in a fluidized bed coupled with an entrained-flow Bed.

Fluidized bed gasification zone:

Drying Module (DRYER): An RSTOIC reactor is used to simulate the biomass dry process, removing moisture from the raw material. Pyrolysis Module (RYIELD1): Based on the elemental and proximate analysis data of the biomass, constrained by hydrogen balance, the biomass is decomposed into conventional components such as C, H2, N2, Cl2, S, O2, H2O, and tar.

Gasification Module (RGIBBS1): The restricted chemical equilibrium method is employed to simulate the gasification process in the fluidized bed. By setting the approach temperature or equilibrium extent of the reactions, it is assumed that all reactions reach thermodynamic equilibrium under the specified conditions.

Entrained-flow bed gasification zone:

Pyrolysis Module (RYIELD2): This module is specifically designed to simulate the secondary cracking of tar, completely decomposing the tar from the previous stage into C, H2, O2, and N2.

Gasification Module (RGIBBS2): Its setup is similar to the RGIBBS1 module, but the operating temperature is set higher to promote further conversion of the products.

Bottom slag treatment zone:

To enhance the carbon conversion rate of the system, a portion of the bottom slag is recycled. This zone simulates the re-gasification of the recycled slag via the gasification module (RGIBBS3).

Overall Process Description:

After pyrolysis in the RYIELD1 module, the biomass products (at this stage, tar has not yet participated in reactions) are mixed with gasifying agents (CO2, H2O, O2, N2) and recycled gas (GAS1) from the slag treatment zone in the mixer MIXER1. The mixture then enters the RGIBBS1 module for gasification reactions. The resulting stream is preliminarily separated in the separator SEPARATION1 into raw product gas and semi-coke (SLAG1). The semi-coke (SLAG1) is mixed with supplementary gasifying agents in MIXER3 and enters the RGIBBS3 module for reaction, producing slag gas (GAS1) and final residue (SLAG2). Meanwhile, the raw product gas from SEPARATION1 is separated in SEPARATION2 to extract tar, which is then completely cracked in the RYIELD2 module. The cracked products are mixed with oxygen (O2) in MIXER2 and enter the RGIBBS2 module for deep gasification. Finally, all gas and solid products are separated via the SSPLIT module to obtain the final gas product and ash.

2.2.3. Chemical Reactions

Based on the elemental composition, reactants, and products, the number of independent reactions calculated for the process is about 10. The Restricted Reaction Equilibrium Model was used to study the Fluidized Bed Coupled with Entrained-Flow Bed. This meant that the chemical reactions were assumed to be at equilibrium but at different temperatures. The reaction list in Table 3 serves a specific purpose within the Restricted Chemical Equilibrium framework in Aspen Plus. Its primary aim is not to present all possible reaction pathways, but to selectively constrain the equilibrium of certain key and trace-element reactions during Gibbs free energy minimization, there by simulating toward a more industrially plausible outcome.

Table 3.

The equilibrium temperature and temperature difference of reactions in the biomass gasification process.

- Core Gasification Reactions (R1–R4): These reactions (Boudouard, steam gasification, combustion, and methanation) are essential for modeling the main conversion of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen.

- Trace-Element Constraints (R5–R10): Reactions involving NH3, H2S, Cl2, HCN, and COS are included not as dominant pathways, but to ensure proper elemental balance of N, S, and Cl from the biomass feedstock into realistic gaseous species (e.g., NH3, H2S, HCl). Their high equilibrium temperatures (set at 1000 °C with a +100 °C approach) intentionally limit their forward progress, which is consistent with their minor yields under high-temperature gasification conditions.

- The tar component was complex, which made it difficult to consider in the model. Its decomposition component was simplified into H2, CO, CO2, CH4, H2O and char. The methane was mainly formed from the pyrolysis. After many continuous attempts, the methane generated by C-H2 was considered.

The RGIBBS reactors were configured using the Restricted Chemical Equilibrium method. For key reactions listed in Table 3, an ‘Approach to Equilibrium Temperature’ (ΔT) was specified. This parameter modifies the equilibrium constant used in the Gibbs minimization for that specific reaction. The effective equilibrium constant Keff is calculated at a temperature offset from the reactor operating temperature (Treactor): Keff = Keq(Treactor−ΔT).

The detailed information on the used models in ASPEN PLUS V12 is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

The detailed information on the used models in ASPEN.

The model includes trace species (e.g., NH3, HCN, and COS) to close the elemental balance for N and S. However, as their predicted concentrations are at trace levels (<0.1 vol%) and have a negligible impact on the overall energy and mass balances under the conditions studied, their behavior is not analyzed in the results section.

2.2.4. Rationale, Impact, and Limitations of Key Assumptions

The model’s assumption of perfect equilibrium inherently omits critical non-idealities of real-world systems. Some assumptions should be deeply discussed.

- (1)

- Instantaneous pyrolysis

These were commonly used in modeling biomass gasification. The time for the pyrolysis reaction was much shorter than that for char gasification, which had little effect on product yields. The pyrolysis process could be completed if a screw feeder without cooling is used at a gasification temperature of 800 °C [27]. This evidence supports the assumption.

- (2)

- Total neglect of hydrodynamics and kinetics

Specifically, the lack of hydrodynamic modeling fails to capture the complex fluid dynamics, mixing efficiency, and residence time distributions within the reactor, which directly influence reaction pathways and product yields. Because of complex hydrodynamics and kinetics, it was difficult to establish the model, which was further conducted in our future work. In this case, the model was used to support the design of the FB-EFB configuration, also with the engineer’s experience. After varying the experimental data, the model was continuously revised to meet the engineering needs.

- (3)

- Fixed heat losses

The heat loss was fixed 5%, which was further modified according to the real operation data. These values were determined based on similar industry operations and the engineer’s experience.

Furthermore, the absence of detailed tar chemistry leads to a significant underestimation of these problematic condensable hydrocarbons, resulting in an overly optimistic prediction of syngas quality and composition. Consequently, these simplifications cause potential deviations from real operation, as the model cannot accurately predict phenomena like incomplete carbon conversion, ash-related issues (slagging/fouling), or the formation of pollutants. Explicitly addressing these limitations would not only present the findings but also significantly strengthen the manuscript by outlining a clear pathway for future work, incorporating more advanced kinetic or computational fluid dynamics (CFD) approaches. A key limitation of the equilibrium model is its inability to account for ash transformation and agglomeration behavior. Consequently, while the model can identify a thermochemically favorable temperature range, the final operating temperature for a given biomass must be validated against its specific ash fusion characteristics to ensure technical feasibility.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Model Validation

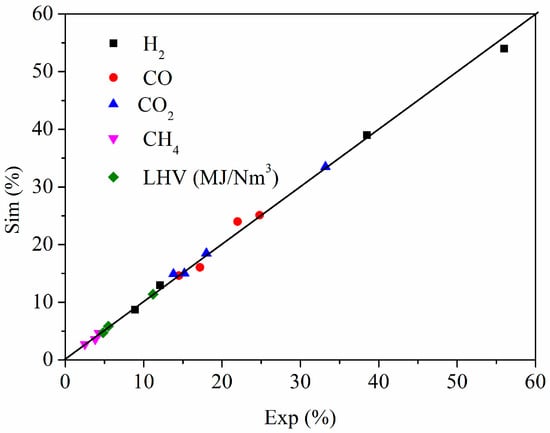

To assess the predictive accuracy and reliability of the established Aspen Plus model, a validation exercise was conducted by simulating the air-steam gasification of woody biomass in a fluidized bed reactor as reported by Pauls et al. [12], Nikoo et al. [14], Yang et al. [15] and Castro et al. [9]. The operating conditions, including temperature, pressure, equivalence ratio (ER), and steam-to-biomass ratio, were precisely replicated in our model as input parameters. The simulated composition of the product syngas (H2, CO, CO2, CH4) and its lower heating value (LHV) were then compared against the corresponding experimental measurements from [9,12,14,15].

As shown in Figure 3, the simulation results show good agreement with the experimental data, with the relative deviations for all major gas components and LHV being below 10%. The model slightly overpredicts H2 and CH4 yields, which is a common characteristic of equilibrium models that assume complete tar cracking and may not fully capture kinetic limitations of methane reforming. Nonetheless, the close correspondence between the simulated and experimental values confirms that the model structure, reaction network, and thermodynamic assumptions are fundamentally sound. This successful validation against an independent experimental dataset provides confidence in the model’s capability to reasonably predict the performance of the more complex coupled fluidized–entrained flow bed system and lends credibility to the optimal operating conditions derived the refrom.

Figure 3.

Comparison of simulation data with experimental results [9,12,14,15].

3.2. Model Predictions

To further analyze the matching relationship between the process parameters of the fluidized bed and the entrained-flow bed in the biomass gasification process, the model predicted the effects of pressure, equivalence ratio (ER), CO2/biomass ratio, H2O/biomass ratio, oxygen distribution ratio, fluidized bed gasification temperature, and entrained-flow bed gasification temperature, tar conversion efficiency on gas composition, gas yield, gas heating value (LHV), and cold gas efficiency. To make it clearer, the important factors of ER, oxygen distribution ratio, fluidized bed gasification temperature, and entrained-flow bed gasification temperature were shown. Other factors could be found in the support information.

3.2.1. Equivalence Ratio (ER)

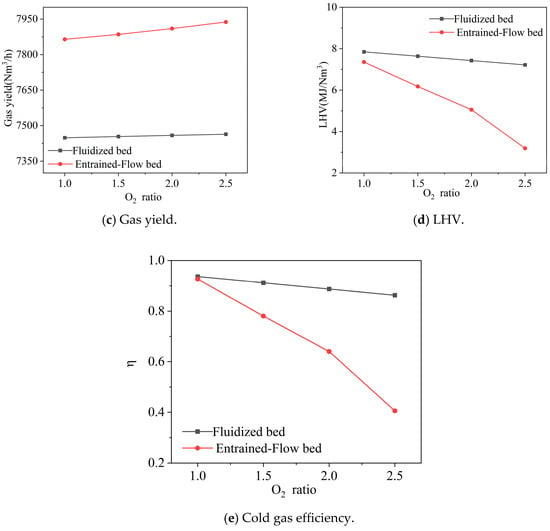

The equivalence ratio (ER), defined as the ratio of the actual oxygen supply to the theoretical oxygen required for complete combustion of the biomass, directly determines the heat supply level within the gasifier. An excessively high ER leads to the consumption of excess biomass through combustion, generating more CO2; conversely, an excessively low ER results in insufficient exothermic heat from oxidation reactions, increases tar production, and poses challenges to stable system operation.

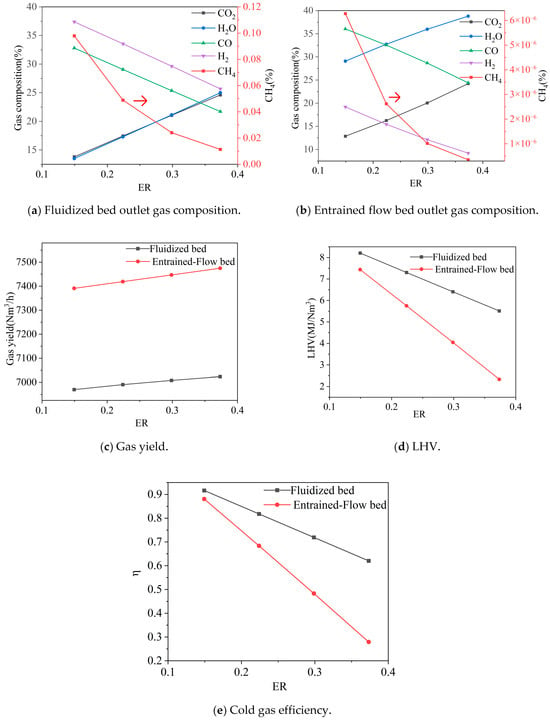

Under the conditions of pressure = 0.1 MPa, CO2/biomass ratio = 0.17, H2O/biomass ratio = 0.10, oxygen distribution ratio between fluidized bed and entrained-flow bed inlets = 1, fluidized bed temperature = 900 °C, and entrained-flow bed temperature = 1400 °C, the effects of different ER values on gas composition, gas yield, heating value, and cold gas efficiency are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Effect of ER on gas composition, gas yield, LHV, and cold gas efficiency. Note: CGE values are predicted by an idealized thermodynamic model and represent theoretical maxima. Practical systems achieve significantly lower efficiencies (typically 60–75%).

As ER increased from 0.15 to 0.37, the fluidized bed outlet gas composition changed significantly: CO2 and H2O increased from 0.14 to 0.25 and 0.24, respectively, while CO and H2 decreased from 0.33 to 0.22 and 0.37 to 0.26, respectively. CH4 varied less. This change is primarily attributed to more combustible components (such as CO, H2, and fixed carbon) participating in combustion reactions. The reaction of CO with O2, forming CO2, along with the complete oxidation of carbon, collectively lead to the decrease in CO content and increase in CO2 content. A large portion of carbon is directly oxidized, reducing the proportion of carbon participating in gasification reactions and thus limiting H2 generation. Simultaneously, part of the generated H2 reacts with O2 to form steam, further reducing the H2 content. During this process, the fluidized bed gas yield slightly increased from 6970 Nm3/h to 7024 Nm3/h, but the gas heating value significantly decreased from 8.21 MJ/Nm3 to 5.51 MJ/Nm3, and the cold gas efficiency also dropped from 0.92 to 0.62. The model predicts that the thermodynamic limit for CGE approaches 0.92 under low-ER conditions, which is unattainable in practice. However, the strong negative trend with increasing ER indicates that minimizing ER is critical for maximizing real-world efficiency, even though the absolute achievable value will be lower.

The entrained-flow bed outlet exhibited a similar trend: CO2 increased from 0.13 to 0.24, H2O increased from 0.29 to 0.39, CO and H2 decreased from 0.36 to 0.24 and 0.19 to 0.09, respectively, while CH4 remained largely unchanged. The gas yield slightly increased from 7391 Nm3/h to 7475 Nm3/h. However, the gas heating value sharply decreased from 7.44 MJ/Nm3 to 2.33 MJ/Nm3, and the cold gas efficiency drastically dropped from 0.88 to 0.28. This is mainly attributed to the significant reduction in the concentration of combustible components, especially H2 and CO.

In summary, an increase in ER leads to a decrease in the content of syngas components (CO and H2), and a substantial decline in both gas heating value and cold gas efficiency. Therefore, the ER should be controlled within a lower range during actual operation. While the model predicts optimal syngas quality at ER ≈ 0.15–0.20, it is crucial to note that this finding assumes ideal, complete tar conversion. In an actual system, operating at such a low ER would typically result in unacceptable tar yields, leading to fouling. Therefore, the practical operable ER is often higher, representing a compromise between efficiency and operability. The model’s result highlights the potential efficiency benefit if advanced tar reduction methods can enable stable operation at lower ERs.

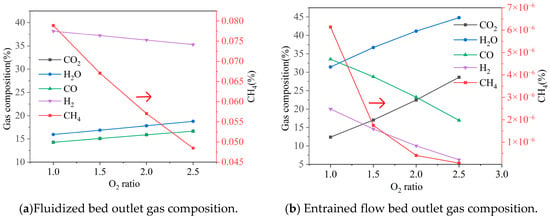

3.2.2. Oxygen Distribution Ratio

The oxygen distribution ratio is defined as the ratio of oxygen fed into the fluidized bed to that fed into the entrained-flow bed. Under the conditions of pressure of 0.1 MPa, CO2-to-biomass ratio of 0.17, H2O-to-biomass ratio of 0.10, fluidized bed temperature of 900 °C, and entrained-flow bed temperature of 1400 °C, the effects of different oxygen distribution ratios on gasification performance are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Effect of the ratio of oxygen distribution on gas composition, gas yield, LHV, and cold gas efficiency. Note: CGE values are predicted by an idealized thermodynamic model and represent theoretical maxima. Practical systems achieve significantly lower efficiencies (typically 60–75%).

As the oxygen distribution ratio increased from 1.0 to 2.5 (indicating a relatively higher proportion of oxygen allocated to the entrained-flow bed), the gas composition at the fluidized bed outlet changed as follows: CO2 and H2O increased from 0.14 and 0.16 to 0.17 and 0.19, respectively; CO increased from 0.14 to 0.17; while H2 decreased from 0.38 to 0.35, and CH4 showed a slight decline. During this process, the gas yield slightly increased from 7449 Nm3/h to 7464 Nm3/h, but the gas heating value decreased from 7.85 MJ/Nm3 to 7.22 MJ/Nm3, and the cold gas efficiency dropped from 0.94 to 0.86. The much higher cold gas efficiency should be taken care of, which was a thermodynamic benchmark, and not a realistic target. In the actual process, factors such as tar not decomposing will reduce these values.

In contrast, the entrained-flow bed outlet was more significantly affected by changes in the oxygen distribution ratio: CO2 increased substantially from 0.12 to 0.29, H2O rose from 0.31 to 0.45, while CO and H2 decreased sharply from 0.34 and 0.20 to 0.17 and 0.06, respectively. The CH4 content remained largely unchanged. Although the gas yield slightly increased from 7864 Nm3/h to 7938 Nm3/h, the gas heating value dropped sharply from 7.36 MJ/Nm3 to 3.19 MJ/Nm3, and the cold gas efficiency also decreased significantly from 0.93 to 0.41. This phenomenon is primarily attributed to the introduction of excessive oxygen in the entrained-flow bed, which intensified the combustion consumption of combustible components (H2 and CO). High CGE represents a thermodynamic upper bound. Some reasons could be used to explain this. The equilibrium model inherently predicts optimistic values for cold gas efficiency (CGE), as it does not account for kinetic limitations to carbon conversion, non-ideal heat exchange, energy penalties associated with tar condensation or removal, or solid separation inefficiencies. Therefore, the absolute CGE values reported should be interpreted as theoretical maxima under idealized conditions. The model’s primary utility lies in its ability to reliably predict comparative trends and parametric sensitivities, which remain valid for guiding process optimization.

In summary, the oxygen distribution ratio has a much greater impact on the entrained-flow bed than on the fluidized bed. To enhance the overall system performance, it is recommended to allocate most of the oxygen to the fluidized bed for gasification reactions, while only a small amount of oxygen should be introduced into the entrained-flow bed to support tar cracking, thereby avoiding excessive consumption of combustible components.

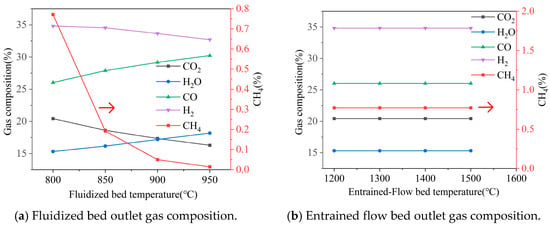

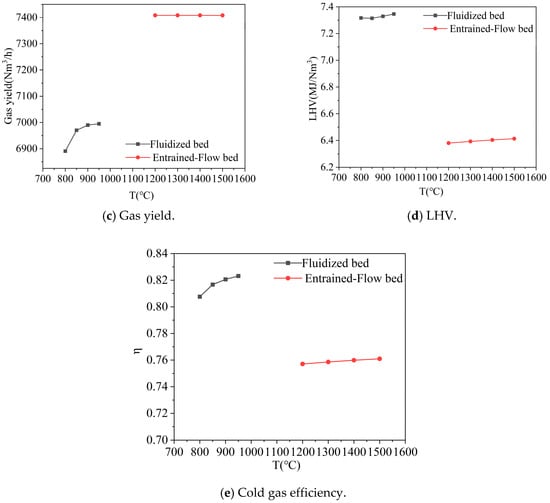

3.2.3. Effect of Temperature

Operating temperature is a key parameter influencing the performance of biomass gasification. Under the conditions of pressure of 0.1 MPa, CO2-to-biomass ratio of 0.17, H2O-to-biomass ratio of 0.10, fluidized bed inlet equivalence ratio of 0.32, entrained-flow bed inlet equivalence ratio of 0.24, and fluidized bed-to-entrained-flow bed oxygen distribution ratio of 1.3, the effects of fluidized bed and entrained-flow bed temperatures on gasification characteristics were investigated. The results are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Effect of temperature on gas composition, gas yield, LHV, and cold gas efficiency. Note: CGE values are predicted by an idealized thermodynamic model and represent theoretical maxima. Practical systems achieve significantly lower efficiencies (typically 60–75%).

As the fluidized bed temperature increased from 800 °C to 950 °C, significant changes were observed in the outlet gas composition: CO2 decreased from 0.20 to 0.16, H2O increased from 0.15 to 0.18, CO increased from 0.26 to 0.30, H2 slightly decreased from 0.35 to 0.33, and CH4 varied less. The temperature rise promoted a shift in the equilibrium of endothermic reactions to the reactant based on Le Chatelier’s principle, including the Boudouard reaction (C + CO2 → 2CO), the water-gas reaction (C + H2O → CO + H2). This led to a decrease in CO2 concentration and an increase in CO concentration. During this process, the gas yield from the fluidized bed increased from 6891 Nm3/h to 6995 Nm3/h, the gas heating value slightly rose from 7.32 MJ/Nm3 to 7.35 MJ/Nm3, and the cold gas efficiency improved from 0.80 to 0.82. This value was a little higher than the real operation because of some ideal assumption.

In contrast, when the entrained-flow bed temperature varied in the range of 1200 °C to 1500 °C, the outlet gas composition remained essentially stable (CO2 ~0.20, H2O ~0.15, CO ~0.26, H2 ~0.35). The gas yield was maintained at approximately 7408 Nm3/h, while the gas heating value slightly increased from 6.38 MJ/Nm3 to 6.41 MJ/Nm3, much higher than that in Nikitin’s work value of 2.47–5.88 MJ/Nm3 [25], and the cold gas efficiency stabilized at 0.76.

Comprehensive analysis indicates that when the fluidized bed temperature exceeds 900 °C, the improvements in gas heating value and gas yield tend to level off. Matsumoto [26] suggested the suitable operation temperature for syngas was 950–1050 °C. Meanwhile, an entrained-flow bed temperature of 1200 °C is already sufficient to meet gasification requirements, and further increasing the temperature provides limited benefits to system performance. Therefore, it is recommended to control the fluidized bed operating temperature above 900 °C and maintain the entrained-flow bed temperature at around 1200 °C to achieve an optimal balance between energy efficiency and operating costs.

It is crucial to emphasize that the selection of an optimal fluidized-bed temperature in practice involves a critical compromise not considered in this thermodynamic model: the avoidance of ash-related agglomeration. The operating temperature must remain safely below the ash softening or melting point specific to the biomass feedstock to ensure stable fluidization. Therefore, while the model indicates diminishing thermochemical benefits above 900 °C, the practically attainable temperature may be lower, dictated by fuel ash properties. The model’s result defines the thermochemical incentive for operating at higher temperatures, provided ash chemistry permits.

4. Conclusions

An Aspen model for the biomass gasification process using a coupled fluidized bed and entrained-flow bed system was developed. The model primarily incorporates DRYER, RYIELD, RGIBBS, MIXER, and SEP modules, with the chemical reactions in RGIBBS considered as a restricted chemical equilibrium model. The model predicts the effects of pressure, equivalence ratio (ER), carbon dioxide-to-biomass ratio, steam-to-biomass ratio, oxygen distribution ratio, fluidized bed gasification temperature, entrained-flow bed gasification temperature, tar conversion efficiency, gas composition, gas yield, gas low heating value, and cold gas efficiency.

The simulations suggest that high system performance is achieved under conditions of lower pressure (e.g., near atmospheric, ~0.1 MPa), low equivalence ratio (ER in the range of 0.15–0.2), minimal addition of external CO2 and steam, oxygen distribution biased toward the fluidized bed, and temperatures of approximately 900 °C in the fluidized bed and 1200–1400 °C in the entrained-flow bed.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/en19010037/s1, S1. Pressure (P). Figure S1. Effect of pressure on gas composition, gas yield, LHV and cold gas efficiency. S2. Carbon Dioxide-to-Biomass Ratio. Figure S2. Effect of ratio of carbon dioxide to biomass on gas composition, gas yield, LHV and cold gas efficiency. S3. Steam-to-Biomass Ratio. Figure S3. Effect of ratio of steam to biomass on gas composition, gas yield, LHV and cold gas efficiency. S4. Sensitivity to Tar Conversion Efficiency. Figure S4. Effect of ratio of tar conversion efficiency on gas composition, gas yield, LHV and cold gas efficiency.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.W.; Writing—original draft, J.W.; Writing—review and editing, W.L., Z.L., H.Z., X.H., B.P., L.C., and R.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the Technological Innovation Project of CHN Energy (Grant No. GJNY24-26) and the Fundamental Research Program of Shanxi Province (Grant No. 202403021221115).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Jingjing Wang, Zhen Liu, Huimin Zhang, Xin Huang, Baozai Peng, Liang Chang and Ruihan Yang were employed by National Institute of Clean-and-Low-Carbon Energy. The remaining author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Kartal, F.; Ozveren, U. A comparative study for biomass gasification in bubbling bed gasifier using Aspen HYSYS. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2021, 13, 100615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, P.; Tyagi, R. Advanced simulation of biomass gasification in a fluidized bed reactor using ASPEN PLUS. Renew. Energy 2017, 101, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoo, K.K.; Said, M.S.M. Air gasification of empty fruit bunch: An Aspen Plus model. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2021, 16, 100848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadoon, U.K.; Díaz, I.; Rodrígue, M. Comparative analysis of aspen plus simulation strategies for woody biomass air gasification processes. Biomass Bioenergy 2025, 194, 107626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatro, A.; Mahanta, P. Gasification studies of low-grade Indian coal and biomass in a lab scale pressurized circulating fluidized bed. Renew. Energy 2020, 150, 1151–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, N.B.; Chen, C.X.; Magdziarz, A.; Zhang, L.H.; Quan, C. Modeling and simulation of pine sawdust gasification considering gas mixture reflux. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2021, 155, 105094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.D.; Zhang, H.; Li, G.; Zhang, X.; Luo, Z.X.; Huang, L.; Zhang, S.H. Modeling of industrial biomass fluidized bed gasification system and optimization of operating conditions. Biomass Bioenergy 2026, 204, 108403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Huang, Y.J.; Qiu, Y.Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z.Y.; Song, H.K.; Tang, T.H.; Xiao, Y.X.; Liu, H. Modelling of biomass gasification for fluidized bed in Aspen Plus: Using machine learning for fast pyrolysis prediction. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 332, 119695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, J.; Leaver, J.; Pang, S. Modelling of enhanced dual fluidized bed steam gasification with integration of biomass-specific devolatilization. Biomass Bioenergy 2026, 204, 108445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, S.; Yadav, S.; Singh, D.; Sistla, Y.S. Simplified approach of modeling air gasification of biomass in a bubbling fluidized bed gasifier using Aspen Plus as a simulation tool. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 115402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoo, K.K.; Said, M.S.M. Simulation of air gasification of Napier grass using Aspen Plus. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 50, 101837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauls, J.H.; Mahinpey, N.; Mostafavi, E. Simulation of air-steam gasification of woody biomass in a bubbling fluidized bed using Aspen Plus: A comprehensive model including pyrolysis, hydrodynamics and tar production. Biomass Bioenergy 2016, 95, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puig-Gamero, M.; Pio, D.T.; Tarelho, L.A.C.; Sanchez, P.; Sanchez-Silva, L. Simulation of biomass gasification in bubbling fluidized bed reactor using aspen plus®. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 235, 113981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikoo, M.B.; Mahinpey, N. Simulation of biomass gasification in fluidized bed reactor using ASPEN PLUS. Biomass Bioenergy 2008, 32, 1245–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.G.; Zhao, J.L.; Zhang, C.H.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Z.X.; Lu, Q. Process simulation of biomass gasification for hydrogen production with different agents. Clean Coal Technol. 2025, 31, 50–60. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.Q. Experimental Research and Simulation Based on Aspen Plus of Biomass Gasification in Fluidized Bed. Master’s Thesis, Southeast University, Nanjing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Si, W.F. Research on Biomass Staged Gasification Characteristics in a Dual Circulated Fluidized Bed. Master’s Thesis, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.Q. Experiment and Numerical Simulation on Gasification Behavior of Biomass in Quadruple Fluidized Bed. Master’s Thesis, Beijing Jiaotong University, Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.P. Research on Gasification/Co-Gasification Characteristics and Mechanism of Coal, Waste and Other Carbonaceous Materials. Ph.D. Thesis, East China University of Science and Technology, Shanghai, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H.Y. Influence of Gasification Parameters Research on Active Air Distribution Fixed-Bed Biomass Gasifier. Ph.D. Thesis, Shandong University, Jinan, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kuttin, K.W.; Salem, A.M.; Kuttin, A.W.; Ding, L.; Yu, G.S. Nonlinear numerical modelling assessment of pressurized biomass downdraft fixed bed gasification process with experimental validation. Fuel 2025, 397, 135364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrueco, C.; Recari, J.; Güell, B.M.; del Alamo, G. Pressurized gasification of torrefied woody biomass in a lab scale fluidized bed. Energy 2014, 70, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Wang, Q.H.; Long, Z.Y.; Rong, N.; Deng, G.Y. H2 rich gas production via pressurized fluidized bed gasification of sawdust with in situ CO2 capture. Appl. Energy 2013, 109, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fermoso, J.; Arias, B.; Gil, M.V.; Plaza, M.G.; Pevida, C.; Pis, J.J.; Rubiera, F. Co-gasification of different rank coals with biomass and petroleum coke in a high-pressure reactor for H2-rich gas production. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 3230–3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikitin, A.D.; Abaimov, N.A.; Ershov, M.I.; Tuponogov, V.G.; Simbiryatin, L.V.; Ryzhkov, A.F.; Alekseenko, S.V. Investigation of air-blown biomass gasification in a pilot setup. Thermophys. Aeromech. 2025, 32, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, K. An entrained flow biomass gasification technology with the fluidized bed concept for low-carbon fuel production. Appl. Energy Combust. Sci. 2024, 20, 100292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.B.; Lim, C.J.; Yue, G.X.; He, B.; Grace, J.R. One-dimensional modeling of a dual fluidized bed for biomass steam. Gasif. Energy Convers. Manag. 2016, 127, 612–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemisohi, A.; Wang, L.; Shahbazi, A. Numerical analysis of biomass gasification in a fluidized bed reactor using a computational fluid dynamics model integrated with reduced-order reaction kinetics. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2024, 206, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Hu, C.; Zheng, Y.Z.; Jin, H.; Wu, Z. Predictive control of reactor network model using machine learning for hydrogen-rich gas and biochar poly-generation by biomass waste gasification in supercritical water. Energy 2023, 282, 128441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuttin, K.W.; An, F.B.; Richter, A.; Yu, G.S.; Wang, Y.F.; Wang, F.C.; Ding, L. CFD modelling of hydrothermal carbonized biomass pellets gasification: Synergistic effects of pellets size and moisture content on gasification efficiency. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 84, 420–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.