Abstract

Air pollution episodes caused by particulate matter (PM) persist in and around Kraków even after the city’s ban on solid fuels. We examine how household wealth and the ongoing replacement of old heat sources with modern, energy-efficient units affect these emissions. Years of hourly data from a network of low-cost sensors for neighboring municipalities are combined with the Poland building emissions register specifying the number and type of heating devices and municipal personal income tax records. Two distinct emission patterns emerge. Episodes of elevated concentrations near houses with old hand-loaded stoves follow pronounced behavioral cycles tied to residents return home hours and the nightly sleep cycle, whereas elsewhere the pattern is smoother—consistent with modern heating sources or with advection from dispersed upwind sources. Municipalities that recorded per capita income growth also showed declines in average PM concentrations, suggesting that rising incomes accelerate the transition to cleaner, more efficient heating. Our findings suggest that economic development is linked to the shift towards cleaner and more efficient energy, and that providing targeted support for low-income households should not be overlooked in completing the transition.

1. Introduction

Air pollution poses a serious health risk, occurring at high levels in urban areas [1,2]. PM2.5 particulate matter has a decisive impact on air pollution [3,4,5]. City, regional and national authorities have been tackling this problem for years by implementing programmes to restrict the use of solid fuels, supporting the replacement of heat sources with less polluting ones, and providing subsidies to the poorest residents to cover their energy costs [6,7]. These efforts face various difficulties and do not always yield satisfactory results, but politicians, scientists and communities are becoming increasingly aware of the problem [8]. The problem also affects Kraków (southern Poland), where, despite radical legal measures (a ban on the use of solid fuels), the problem still occurs in the winter months, when high concentrations of particulate matter are recorded, “transported” from neighbouring municipalities.

As a result of spatial analysis in selected municipalities of the Małopolska Region, located in the vicinity of Kraków, two types of solid fuel appliances were observed: those with an automatic feeder and older types without a feeder. It was noted that there are different emission patterns for these groups. In the case of furnaces with automatic feeders, PM2.5 exceedances are caused by humidity and, to a lesser extent, temperature. In the case of the group of old stoves, behavioural patterns are responsible for exceeding the permissible standards, with the main predictor being the time of day, related to residents returning home and starting to burn fuel in the stove. It was assumed that old types of stoves are used by residents with lower incomes.

The authors analysed the first three weeks of March in the years 2021–2025. This data was then compared with personal income tax revenues for the same years and the so-called resident wealth index. Based on a comparison of air pollution in 2021–2025 with resident wealth, a trend was observed indicating a correlation between income growth and a decrease in PM2.5 concentrations. This may be the result of the purchase of a new type of furnace with a feeder or a device that does not require the use of solid fuels (e.g., gas furnaces, heat pumps).

This study does not aim to determine whether poorer households use more solid fuels, a relationship already well established in the literature. Instead, it quantifies the spatial and temporal heterogeneity of the heating transition in the municipalities surrounding Kraków, identifies outliers where the transition remains slow and links these patterns to observable changes in PM2.5 consistent with evolving emission structures. These aspects are essential for designing targeted regional energy-transition policies.

2. Literature Review

Located in southern Poland, Kraków has been struggling with air pollution for decades. During the winter months, it is often ranked among the cities with the highest levels of air pollution in Europe [9]. This is despite restrictive policies by local and regional authorities, which have banned the use of solid fuels for heating since 2019 [10]. The issue of air pollution in Kraków is an important problem for residents [11], local activists [12], the medical community [13], politicians [14] and scientists from various fields. Although these issues have been considered in such a multifaceted way, previous studies have paid very little attention to the impact of residents’ wealth on their heating sources. Following the introduction of a ban on the use of solid fuels in Kraków, a significant proportion of particulate emissions are caused by pollution from neighboring municipalities. Currently, the key issue remains the number and type of heating devices used in neighboring municipalities. This is strongly supported by numerous studies demonstrating that wintertime PM concentrations in Kraków are dominated by low stack emissions transported from neighbouring municipalities rather than by local industrial sources or regional background. Recent works using geostatistics, machine learning, and long-term sensor networks consistently shows that cross-boundary inflow from surrounding municipalities is the primary driver of elevated PM2.5 episodes in the city [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. These studies share the same conclusion: the spatial and temporal structure of PM pollution in Kraków area cannot be explained without considering emissions from surrounding municipalities that rely on solid-fuel heating.

Thanks to access to accurate data on the number and type of these devices, information on tax revenues and the wealth index of municipalities, as well as data on air quality, the authors were able to examine the problem in terms of the wealth of individual municipalities in the vicinity of Kraków.

The issue of the relationship between wealth and air pollution is very important in the context of designing policy solutions related to remedial measures. The literature focuses on urban and suburban areas due to their population density and economic activity [24]. In recent years, many countries around the world have made efforts to promote the development of renewable energy sources in order to reduce pollution, including particulate matter. These efforts have largely focused on technological aspects and, to a lesser extent, on behavioural and social patterns, although this aspect has been developed in recent years [25].

There is a view in the literature that when analysing issues related to energy use, we should also take human behaviour into account [26]. In the case of new technologies, the price of equipment remains a major barrier, which should be reflected in appropriate political and economic decisions [27]. Meanwhile, social and behavioural factors have a significant impact on energy consumption. It has been proven, among other things, that the decline in energy consumption in the residential sector in the United States since the 1970s was not solely due to technology, but also to social attitudes, knowledge and practices [28]. Social aspects can have several dimensions. One of them is social acceptance of changes in the socio-political dimension (relating to public opinion, key stakeholders and decision-makers), in the local dimension (relating to the attitudes of residents) and in the market dimension related to the adoption of a given technology [29,30].

These problems also affect Poland, which underwent significant socio-economic changes after 1989. After the country joined the EU in 2004, the energy transition process accelerated, with many households using modern, low-emission heating sources and support being introduced for the thermal modernisation of buildings. This process is still ongoing. Nevertheless, a significant proportion of households still experience energy poverty, estimated at between 4.2% and 15.4% of the population, depending on the methodology used [31]. This phenomenon mainly affects people with the lowest incomes, particularly property owners in rural areas [32].

It should be noted that this paper does not directly describe the phenomenon of energy poverty, defined in the Polish Energy Law as a situation in which a household, is unable to ensure an adequate level of heating, cooling and electricity to power appliances and lighting. The Act refers to three conditions: households have low incomes, incur high energy costs and live in a dwelling or building with low energy efficiency [33]. According to research conducted in Poland, households located in older buildings and single-family houses, especially those heated with coal or wood, often with insufficient insulation and outdated heating infrastructure, are at risk of energy poverty [34]. In the municipalities surrounding Kraków, some households fall into this category. However, we did not measure the scale of energy poverty in this paper.

In the case described in our paper, we focused on the issue of energy transition and the impact of income on the type of heating used, as well as the overlapping phenomenon of air pollution. It should be noted that the issue of energy poverty is linked to air pollution [35]. These aspects overlap in Kraków and its immediate surroundings. For several years, the Polish government and local authorities have launched numerous programmes and projects enabling residents to replace inefficient heating sources and carry out thermal modernisation. At the same time, regulations that differ significantly from one another have been introduced at various levels of local government [36,37,38]. This has resulted in a situation where Kraków, where solid fuels cannot be used, is affected by air pollution from municipalities where no such ban is in place. The authors used unique sources of information. This allowed them to analyze the relationship between pollution levels and residents’ incomes The latter factor also translates into the type of heating equipment used. Both aid programs and rising incomes contribute to improved air quality. This is shown by data from low-cost sensors (LCS). An analysis based on the years 2021–2025 clearly shows these trends.

3. Materials and Methods

In total, 51 Airly LCS monitoring stations (www.airly.com, accessed on 12 December 2025) were included in the analysis, of which six were located within the city of Kraków and served as urban control points. The remaining stations were situated in surrounding municipalities where the use of solid fuels for heating is still permitted. Airly low-cost sensors are laboratory-calibrated, and previous comparisons with governmental monitoring stations have confirmed their reliability for capturing temporal patterns and relative concentration changes in PM2.5. Furthermore, the sensors have been validated in previous research, reporting strong agreement with reference station measurements across PM1, PM2.5, and PM10, with correlation coefficients exceeding 0.93 and median differences of only –3.0 µg/m3 even under varying atmospheric conditions such as abrupt changes in humidity, temperature, and emissions [15,23]. The dataset was largely complete, with only minor gaps, and any gaps were filled using linear interpolation procedures to ensure temporal consistency. To ensure comparability between years, the analysis focused on March PM2.5 smog episodes. For each year, the analysed period consisted of a seven day window centred on the day with the highest PM2.5 concentration in March (25 March 2021, 3 March 2022, 3 March 2023, 8 March 2024, 9 March 2025), including three days before and three days after the peak, to ensure comparability of late winter smog episodes. March was chosen because this month typically exhibits the greatest variability in air quality, driven by unstable temperatures and the transitional character of the heating season. Concentrating on the strongest and most thermally unstable late-winter episodes allows the analysis to isolate heating related emissions rather than meteorological noise, ensures that all municipalities are examined under comparable thermal stress, and exposes the characteristic behavioral emission patterns associated with old solid-fuel stoves. Such episodes provide the clearest and most diagnostic signal of differences in heating technologies and are therefore the period in which year to year transition dynamics can be meaningfully compared.

Data completeness was generally high. Between 2021 and 2025, missing values occurred for 3, 6, 6, 4, and 6 stations respectively, affecting in total 17 sensors. The most frequent data gaps were observed at stations located in Pierzchów (Gdów municipality, ID 2637), Raciborsko (Wieliczka municipality, ID 2651), Nawojowa Góra (Krzeszowice municipality, ID 37248), and Winiary (Gdów municipality, ID 2365), where missing data were present in four, four, three, and three years respectively. In all other cases, gaps occurred in only one year.

Missing values were imputed using a random forest-based algorithm implemented in the missRanger R package [39]. The imputation model used information on PM1, PM2.5, PM10, air pressure, temperature, relative humidity, as well as the hour of day, day of week, and spatial coordinates of each station. In most cases, data gaps were minor, and cross-validation with a hold-out test yielded R2 values above 0.9, indicating high reliability of the imputed data. Importantly, the imputation did not distort temporal patterns: gaps typically lasted only a few hours, and a visual inspection of the raw and imputed time series confirmed that the temporal structure and short-term dynamics were preserved.

Subsequent analyses were based on principal component analysis (PCA), which allowed us to identify dominant spatial and temporal patterns in PM2.5 variability and to track their evolution over time.

The next data source is the Central Building Emissions Database, a system launched on 1 July 2021 to improve air quality by monitoring heating devices [40]. By 30 June 2022, every property owner in Poland was required to report the heat source they used. Local authorities strictly ensured that the database was complete, so this source can be considered reliable. Thanks to regional and national programmes, including Clean Air [41], heat sources in Poland are being gradually replaced, reducing the number of solid fuel appliances. When replacing a heat source or commissioning a new house, property owners should report this fact, but not all of them do so [42]. In order to use the most reliable figures possible, this paper is based on data submitted to the database by 30 June 2022.

Data on the number of heating sources (Table A1) in buildings is available to representatives of universities and research institutions, among others. According to the survey form, the following could be indicated as solid fuel heat sources:

- Solid fuel boiler (coal, wood, pellets or other type of biomass) with manual fuel feed/backfill.

- Solid fuel boiler (coal, wood, pellets or other type of biomass) with automatic fuel feeding.

- Fireplace/air heater for solid fuel (wood, pellet or other type of biomass, coal).

- Tiled stove for solid fuel (coal, wood, pellets or other type of biomass).

- Stove/coal kitchen.

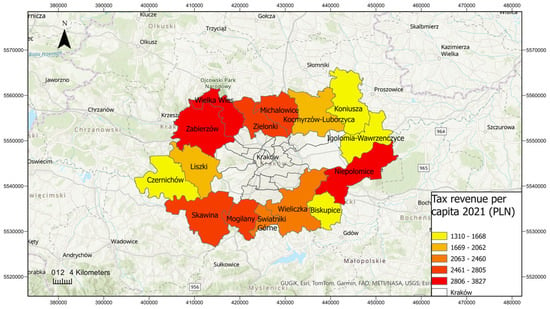

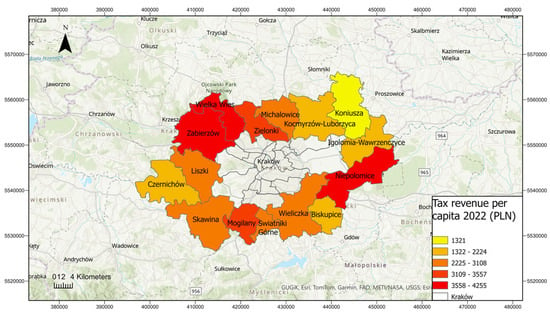

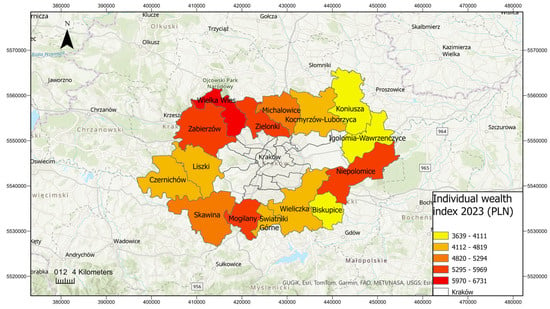

Another source of data is information on the wealth of municipalities. Until 2024, the Ministry of Finance published tax revenue indicators for local government units based on taxes collected two years earlier (in 2023 for 2021; in 2024 for 2022) [43,44,45]. From 2025, the method of determining wealth has changed. The so-called individual wealth indicator is the sum of the basic tax revenues of municipalities divided by the number of their inhabitants, in relation to revenues from two years ago. In this paper, we analyse the years 2021, 2022 and 2023, so the method of calculating the amounts for 2021 and 2022 differs from that for 2023. These amounts are shown in Table A2/Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Figure 1.

Tax revenue per capita of the municipalities around Kraków for 2021.

Figure 2.

Tax revenue per capita of the municipalities around Kraków for 2022.

Figure 3.

Individual wealth index of the municipalities around Kraków for 2023.

4. Data Preparation and Variable Construction

The empirical analysis was conducted using municipal level data describing the heating structure and socioeconomic conditions. Derived variables were constructed to allow for proportional comparison between localities. The share of solid fuel furnaces and share of furnaces with automatic feeders were calculated as ratios of respective heating types to the total number of heating sources in a municipality. The share of clean heating was defined as the complement of solid fuel heating (1—share of solid fuel furnaces), serving as a proxy for the prevalence of low-emission or modern heating technologies. All fiscal and wealth indicators, including tax revenue per capita (2022) and the individual wealth index (2023), were expressed in Polish Złoty (PLN). At this stage, data preparation and computation were performed in Python 3.11 using the pandas library [46].

4.1. Correlation Analysis

To examine the relationships between wealth indicators and heating structures, Pearson’s correlation metrics were computed to assess linear dependence between continuous variables [47]. The correlation matrices were visualized through a heatmap using the seaborn library [48], providing an overview of the direction and strength of associations among fiscal capacity, individual wealth, and heating composition.

4.2. Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) Regression

To estimate the predictive effect of wealth indicators on heating modernization, a series of Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression models were fitted using the statsmodels package [49]. The dependent variable represented the share of clean heating installations (share_clean), while the explanatory variables included tax revenue per capita (2022) and the individual wealth index (2023).

To assess robustness and multicollinearity effects, five model specifications were considered:

Model 1—Wealth only:

Model 2—Tax revenue only:

Model 3—Wealth + Tax revenue:

Model 4—Wealth + Tax revenue growth:

Model 5—Full model (Wealth + Tax revenue + Tax growth):

To visualize the isolated contribution of each predictor in the multivariate OLS model, partial regression plots (added-variable plots) were generated for the most complex model (Model 5). For each predictor, residuals of share_clean—after removing the effect of all other variables—were plotted against residuals of the predictor adjusted for the same control variables. A fitted regression line illustrates the predictor’s unique partial effect net of multicollinearity. Plots were produced using seaborn (scatterplot + regplot), providing a clearer diagnostic than simple bivariate plots by representing each coefficient as it appears in the full model.

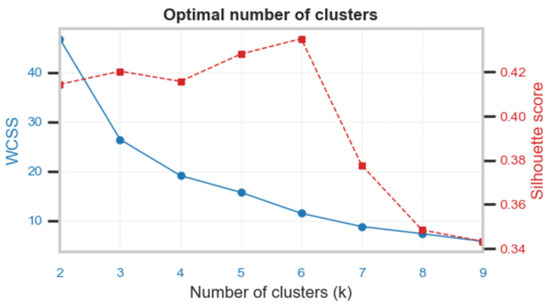

4.3. K-Means Clustering and Model Evaluation

To identify distinct municipal profiles, a K-means clustering algorithm [50] was applied using standardized variables: individual wealth index (2023) and share of solid-fuel furnaces. The number of clusters (k = 3) was determined empirically to ensure interpretability while maintaining internal cohesion.

Cluster compactness and separation were evaluated using two complementary metrics:

- Within-Cluster Sum of Squares (WCSS)—Measuring internal variance within each cluster, with lower values indicating higher compactness.

- Silhouette coefficient—Evaluating cohesion and separation simultaneously [51], where values closer to 1 indicate better defined clusters.

This procedure enabled differentiation of municipalities into three statistically meaningful groups representing distinct socioeconomic and heating profiles.

5. Results

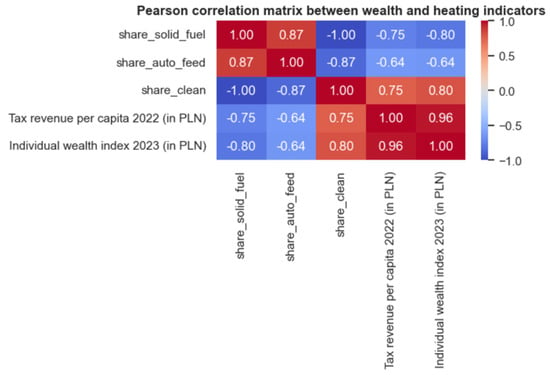

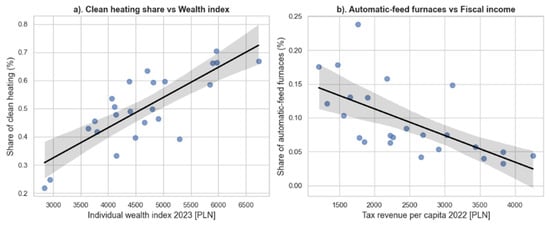

The OLS regression (Table 1) and correlation (Figure 4) analyses indicate a relationship between municipal economic capacity and the adoption of modern heating systems. In the full model, the Individual Wealth Index shows a positive and statistically significant effect on the share of clean heating (β = 0.0001, p = 0.041), suggesting that municipalities with higher household wealth tend to implement low-emission heating technologies. Tax revenue per capita (Tax_mean) and its growth (Tax_growth) were not significant predictors in the full model (β = −0.000045, p = 0.573; β = −0.0020, p = 0.410), indicating that these fiscal measures do not have an independent effect on clean heating adoption when wealth is included. The explanatory power of the full model is substantial (R2 = 0.650, Adjusted R2 = 0.597).

Table 1.

OLS Regression Results—Relationship between wealth and clean heating adoption.

Figure 4.

Pearson correlation matrix between wealth indicators and heating structure.

Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) analysis shows moderate to high multicollinearity between Tax_mean and Wealth index 2023 (VIF = 13.83 and 13.55, respectively), which may contribute to the non-significance of Tax_mean when included alongside wealth. Tax_growth has minimal multicollinearity (VIF = 1.24). The correlation analysis supports these findings: the share of solid-fuel furnaces is strongly negatively associated with both Wealth index 2023 (r = –0.80) and Tax revenue per capita (r = –0.75), while the share of clean heating systems is strongly positively associated with these indicators (r = 0.80 and r = 0.75, respectively). These results suggest that municipalities with lower economic capacity rely more on outdated, high-emission heating, whereas higher wealth and fiscal potential facilitate the adoption of cleaner, more efficient heating technologies. On Figure 5 and Figure 6, it can be observed that higher individual wealth and greater municipal fiscal capacity are associated with a larger share of clean heating systems and a lower reliance on solid fuel, automatic-feed furnaces. Wealthier households consistently adopt modern, low emission heating technologies, while regions with higher fiscal resources show reduced prevalence of outdated, high emission systems. The scatterplots further illustrate that at higher wealth levels, adoption of clean heating becomes more uniform, indicating a convergence toward modern technologies. These visual patterns reinforce the statistical findings from the OLS regression and Pearson correlation analyses, confirming that socioeconomic factors are key determinants of heating system modernization. Taken together, the evidence suggests that targeted support for less affluent households and municipalities could accelerate the transition to cleaner, more efficient heating solutions, promoting regional decarbonization and advancing sustainable energy policy objectives.

Figure 5.

Scatterplots showing relationships between heating indicators and economic variables. Solid lines represent linear regression fits, and shaded areas indicate the 95% confidence intervals around the regression lines. (a) Share of clean heating systems (%) versus Individual Wealth Index (PLN) in 2023. (b) Share of automatic feed furnaces (%) versus Tax revenue per capita (PLN) in 2022.

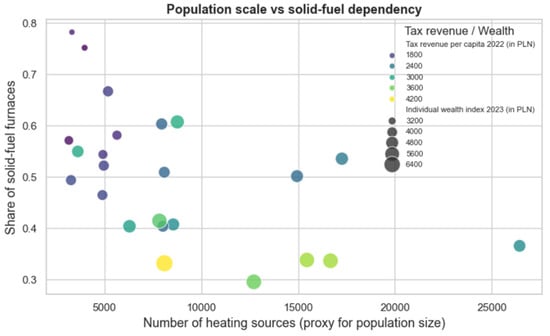

Figure 6.

Relationship between population scale (number of heating sources) and dependency on solid-fuel furnaces. The color gradient represents Tax revenue per capita (PLN) and bubble size denotes the Individual Wealth Index (PLN).

Figure 6 illustrates the relationship between population size, represented by the number of heating sources, and the share of solid-fuel furnaces across various localities. The analysis integrates two additional socioeconomic indicators: tax revenue per capita in 2022 (color gradient) and the individual wealth index in 2023 (bubble size), both expressed in PLN. A clear inverse relationship emerges between locality size and reliance on solid fuels. Smaller municipalities, often exceeding 50–70%. In contrast, larger towns demonstrate a markedly lower dependency, with shares generally below 40%. The color and size dimensions further reveal a consistent socioeconomic pattern. Localities with higher tax revenues and greater individual wealth (represented by lighter colors and larger bubbles) tend to display lower solid fuel usage rates. Conversely, communities characterized by lower fiscal capacity and wealth levels (darker colors, smaller bubbles) show persistent dependence on traditional solid-fuel heating. Those findings are in line with results from OLS regression.

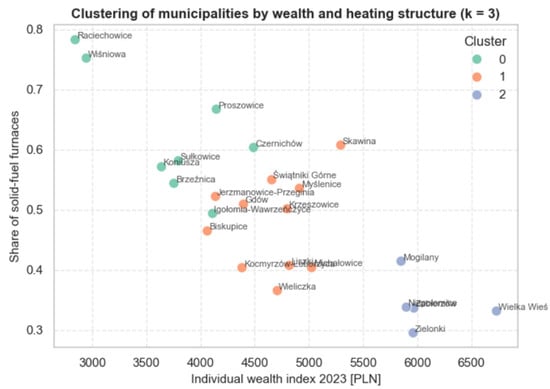

Figure 7 and Figure 8 present the results of a k-means clustering analysis applied to municipalities based on economic indicators and the number of different kinds of heaters. K was chosen to be 3 based on the graphical analysis of the metric (Figure 7). The aim of this analysis was to identify groups of municipalities with similar socioeconomic and energy characteristics.

Figure 7.

Determination of the optimal number of clusters (k) using the elbow (WCSS) and silhouette methods.

Figure 8.

Clustering of municipalities based on heating structure and economic indicators.

The clustering algorithm distinguished three distinct municipal profiles:

- Cluster 0—Low-wealth, high solid-fuel dependency (green). This group comprises small and relatively less affluent municipalities, such as Raciechowice, Wiśniowa, and Proszowice. These localities are characterized by a high share of solid-fuel furnaces (above 0.6) and below average individual wealth levels (below 4000 PLN). The results suggest limited financial capacity for energy transition and a strong persistence of traditional heating methods.

- Cluster 1—Medium-wealth, moderate solid fuel usage (orange). This cluster comprises mid-sized municipalities, including Gdów, Myślenice, and Wieliczka. These areas exhibit intermediate levels of wealth (around 4000–5000 PLN) and moderate reliance on solid fuels (0.4–0.6). Municipalities in this group are likely undergoing a gradual transition toward cleaner heating technologies, with socioeconomic conditions that enable partial modernization of heating infrastructure. It is also important to note that Skawina clearly deviates from the general pattern observed in this cluster, showing a substantially slower transition trajectory despite comparable income levels.

- Cluster 2—High-wealth, low solid-fuel dependency (blue). This cluster encompasses wealthier suburban municipalities, including Zielonki, Zabierzów, and Wielka Wieś. These localities are characterized by high individual wealth indices (above 5500 PLN) and a low share of solid-fuel furnaces (below 0.4). This group represents the most advanced stage of energy transition, likely benefiting from higher household incomes, better infrastructure, and proximity to urban centers.

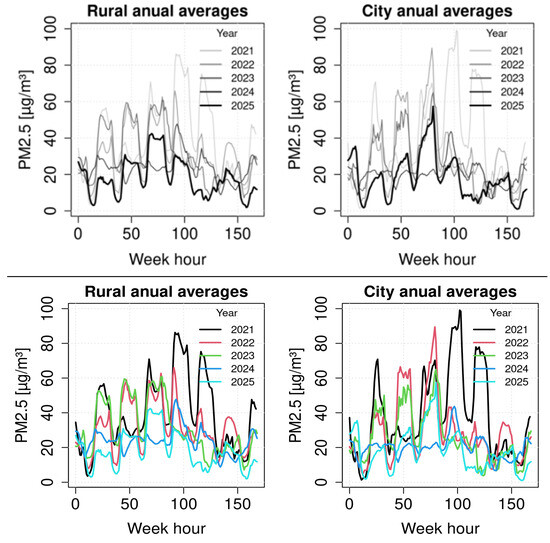

Figure 9 shows the mean PM2.5 concentrations observed during the analyzed episodes, distinguishing between urban and non-urban monitoring sites. The mean values systematically decrease from 2021 to 2025, which is consistent with the general socio-economic improvement and the gradual replacement of solid-fuel heating systems in the municipalities surrounding Kraków. These areas are the main sources of pollution transported into the city, where the use of solid fuels for residential heating is banned and large stationary emission sources are relatively few [52,53,54,55].

Figure 9.

Mean PM2.5 concentrations in 2021–2025 for monitoring stations located outside Kraków and within the city, shown for the week centered on the day of the strongest March smog episode. Note the systematic temporal shift between rural and urban concentration peaks.

An important feature is the differing temporal structure of mean concentrations between urban and rural sites. In the city, the typical two-peak pattern of diurnal PM2.5 variation observed during smog episodes is largely absent, and the peak concentrations appear with a temporal delay relative to the surrounding rural stations. A systematic temporal delay of urban PM2.5 peaks relative to surrounding rural stations cannot result from local circulation alone and indicates advective transport of pollution generated outside the city. Particularly noteworthy is the remarkable similarity in the shape and timing of the major pollution episode centered within each analyzed week, which remains consistent across the five-year period.

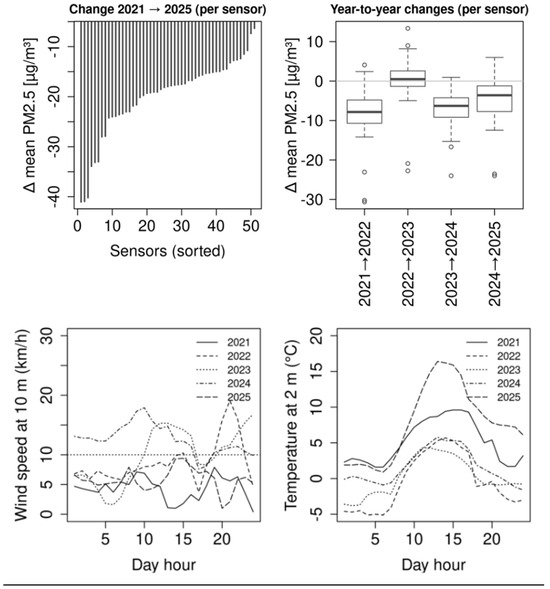

Figure 10 illustrates the decline in mean PM2.5 readings across all analyzed sensors (left panel) and the year-to-year changes in concentrations at individual monitoring sites (right panel). A consistent downward trend in pollution levels is clearly visible during the analysed periods, indirectly confirming a decrease in PM2.5 concentrations consistent with trends reported for the Kraków region in recent years [23]. Notably, only three outlier increases were recorded during the entire period (the latest in 2023), whereas nine pronounced outlier decreases were identified, including two in the most recent year.

Figure 10.

Changes in mean PM2.5 concentrations recorded by individual sensors over consecutive years for the week with the strongest smog episode and general meteorological background. The upper left panel shows the difference between the mean values from 2021 and 2025 for each sensor (sorted in ascending order), while the upper right panel presents the distributions of year-to-year changes. Lower panels show wind speed and temperature observed near Kraków airport Balice.

It is important to emphasize that this improvement cannot be attributed to a steady rise in temperature. The mean temperatures for the analyzed weeks were 5.3, −0.5, 0.0, 4.6, and 9.8 °C in consecutive years, with minimum values of −3.6, −6.6, −6.8, −3.7, and −1.0 °C, respectively. Despite 2025 being both the warmest and least polluted year, the largest single-year decrease in mean PM2.5 concentrations occurred during 2022, which was the coldest in the series. Moreover, each of the analyzed episodes included sub-zero temperatures, implying multiple transitions across the freezing point: a condition known to intensify emissions from domestic heating [23]. Figure 10 also shows that during all selected episodes, near-surface winds measured at the Kraków–Balice airport station were predominantly weak, with a high fraction of hours characterized by wind speeds below 10 km/h, consistent with stagnant dispersion conditions. Notably, the weakest wind conditions were observed in the final year of the analysis. Temperatures recorded at the same place were generally comparable across the analysed years. Interestingly, the highest average temperatures occurred not only in the most recent year, as expected, but also during the first year of the study, further indicating that interannual differences in PM2.5 levels cannot be explained by temperature alone.

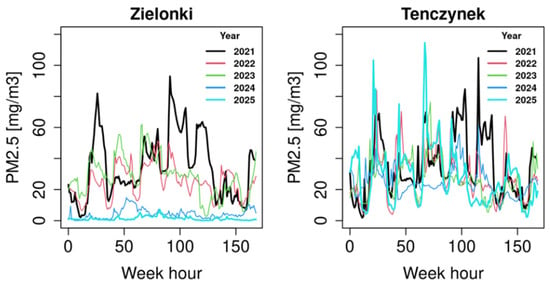

Figure 11 focuses on selected representative sensors. As a positive example, sensor 6147, located in the affluent municipality of Zielonki, ranked fifth in terms of the total decrease in mean PM2.5 levels. It illustrates a clear transition from a typical emission pattern characteristic of old solid-fuel stoves—marked by nighttime reductions in pollution—to an almost complete elimination of emissions during the analyzed episode.

Figure 11.

Changes in hourly PM2.5 concentrations during the weeks with the highest smog episodes in 2021–2025 at two locations: Zielonki (left) and Tenczynek (right), illustrating differences in amplitude, diurnal structure and timing of concentration maxima.

As a contrasting case, sensor 3057, situated in Tenczynek (Krzeszowice municipality), shows virtually no change in mean PM2.5 concentrations between 2021 and 2025. Its temporal profile still exhibits the distinctive diurnal pattern of a traditional stove user, indicating a persistent reliance on solid-fuel heating.

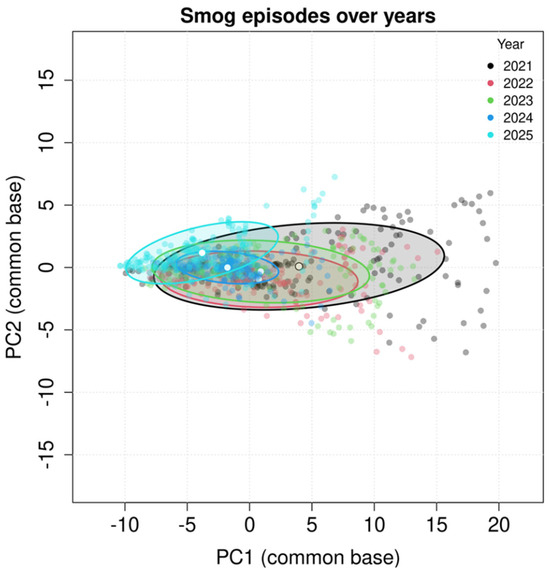

Interesting insights are also revealed by the PCA. Figure 12 presents the projection of data from all sensors and all years onto a common PCA plane. Ellipses representing ±1 standard deviation are drawn around the centroids of projections for successive years. A clear reduction in variance along the PC1 axis can be observed, indicating a gradual homogenization of the pollution signal. In the final year, higher values appear along PC2, which may be related both to climatic factors—particularly the unusually high average temperature—and to the spatial shift of the main emission sources further away from the city. Overall, it seems that PC1 most likely reflects the dominant temporal emission cycle associated with residential heating, whereas PC2 appears to capture a spatial gradient shaped by inflow from neighboring municipalities and elevation-related timing differences, with possible modulation by local circulation conditions. While these interpretations are rather speculative, they provide a possible physical explanation for the convergence and spatial separation observed in the PCA space.

Figure 12.

Projection of the weeks with the strongest smog episodes (2021–2025) onto the common PCA base. Ellipses represent ±1 standard deviation around the centroids for each year.

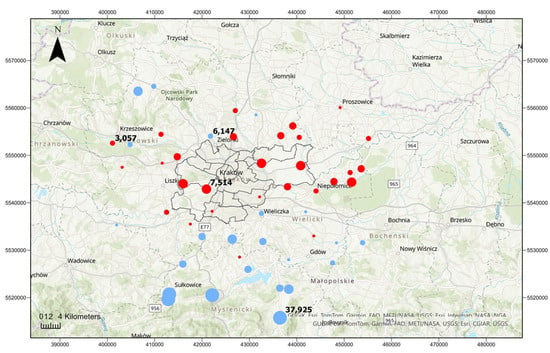

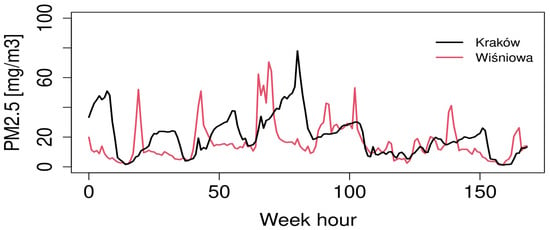

Figure 13 shows the spatial distribution of the loadings of the second principal component (PC2) calculated on the common PCA base, presented in the UTM 34N coordinate system. The color indicates the sign of the loadings (red—positive, blue—negative), while the point size represents their absolute magnitude. Sensors located in Kraków and its immediate surroundings generally display positive loadings, whereas the further and higher above the city the sensor is located, the greater the observed PC2 values. To illustrate this contrast, two sensors were selected for detailed comparison: the one with the most negative loading (37925—Wiśniowa) and the urban sensor with the most positive loading (7514—Kraków). This comparison is presented in Figure 14, which clearly shows the characteristic “old stove” emission pattern in Wiśniowa during the smog episode, as well as the typical time lag in concentration peaks observed for the Kraków sensor.

Figure 13.

Spatial distribution of PC2 loadings on the common PCA base. Red points indicate positive values; blue points indicate negative values.

Figure 14.

Comparison of PM2.5 concentration patterns during the week of the smog episode in Kraków and Wiśniowa.

6. Discussion

The analysis based on data from 2021–2025 suggests a systematic decrease in PM2.5 concentrations across the Kraków region, accompanied by a gradual reduction in differences between urban and non-urban monitoring stations. These results are consistent with the recent socio-economic development of the municipalities surrounding Kraków and their gradual transition away from solid-fuel heating toward more modern energy sources. While emissions are not directly quantified, the observed concentration patterns are consistent with changes in residential heating structures documented for the region.

At the same time, spatial differentiation remains evident, particularly in relation to the second principal component (PC2), which reflects both the directional inflow of pollutants into the city and local topographic conditions. Importantly, numerous studies have demonstrated that wintertime PM2.5 in Kraków is dominated by low-stack residential emissions rather than by industrial or transport related sources, leaving no realistic alternative explanation for the observed year to year decline. This is confirmed by chemical composition analyses [52], regional monitoring reports [53], source-attribution studies identifying low stack heating as the primary driver of exceedances [56], and work showing that even under drastically reduced traffic, residential heating remains the dominant winter contributor to PM2.5 [57]. Together, these findings indicate that the decreasing PM2.5 concentrations recorded during intensive March smog episodes between 2021 and 2025 cannot plausibly be attributed to industrial restructuring or changes in traffic flows, but are fully consistent with the documented shift away from solid-fuel heating in the surrounding municipalities.

The study shows that the Lesser Poland Voivodeship consistently exhibits some of the highest PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations in Poland and is one of only two regions where the annual PM2.5 slightly exceeded the EU Stage 2 limit during 2015–2020 [56]. These elevated particulate levels are attributed to the region’s continued reliance on fossil-fuel-based residential heating, coal-dependent industrial activities, and valley-type topography, which limits pollutant dispersion during winter. Over the study period, Lesser Poland shows a gradual but modest decline in particulate concentrations, while the PM2.5/PM10 ratio remains consistently around 0.7, indicating a predominance of anthropogenic sources, including industrial emissions, secondary particulate formation, and agricultural activities. In contrast, long-term trends in Kraków reveal a steady and measurable reduction in pollution levels, suggesting that targeted local mitigation measures can produce significant improvements even under challenging regional conditions. Although Poland’s national energy mix is gradually transitioning toward renewable sources, these structural changes have not yet resulted in substantial reductions in particulate matter across the Voivodeship, where local emissions and geographic constraints continue to exert a dominant influence [23].

In recent years, a change in the energy structure in Central Europe has been observed. These changes are driven by two main factors. The first is related to European Union policy, which supports the energy transition towards less emission-intensive equipment. The second stems from the geopolitical situation related to the war in Ukraine and the reduction in purchases of energy resources from Russia. These perturbations have an impact on national raw material consumption. However, it is also worth looking at the longer-term trends in raw material consumption. Between 2000 and 2024, the consumption of petroleum products [57], natural gas, with a dip in 2022 [58], and, until 2021, hard coal [59]. These factors reflect the changes that have taken place in Poland over the last quarter of a century and testify to the growing consumption of an increasingly affluent society. These trends may have had some influence on the decisions of residents who decided to replace their heating sources with less polluting ones based on economic calculations (rising coal prices). However, we did not examine the motives of building owners in our publication, as this would require different research tools and methods. Nevertheless, accurate information from the Central Register of Building Emissions provided us with the necessary data to observe the trend linking wealth with the use of more modern and less polluting equipment.

The higher elevation of locations such as Wiśniowa favors an earlier drop in temperature during the day, leading to earlier activation of heating systems and increased emissions. In contrast, sensors located within Kraków show a temporal delay in the occurrence of maximum concentrations, most likely resulting from the advection of pollutants from nearby municipalities. An interesting case is the sensor located in Zielonki, which maintained negative PC2 values throughout the entire study period, indicating that for much of the time this area acted as a pollution source rather than a receptor zone.

However, the data also reveal areas that continue to struggle with the energy transition. A notable example is Tenczynek, a rural settlement within the Krzeszowice municipality, where pollution levels have shown little change over the years and emission patterns characteristic of traditional solid-fuel heating remain clearly visible. This persistence is consistent with the high share of old-type solid-fuel heating devices, which helps explain the limited change observed at this location. A similar challenge is observable in Skawina, which shows an overrepresentation of old-type stoves relative to its overall wealth level, indicating that the pace of heating modernization there lags behind what would be expected for a municipality of its socioeconomic standing.

Overall, the results indirectly indicate that the improvement in air quality patterns in the Kraków region is strongly related to economic development and the modernization of household heating systems in the surrounding municipalities. Despite the observed progress, some local areas with persistently high emissions still require targeted measures to support the ongoing residential energy transition.

Our analysis provides precise guidelines for this intervention. In this context, two observations are key. The first concerns the relationship between the population of a given municipality and the share of solid fuel stoves. The inverse relationship between the size of municipalities and the degree of dependence on solid fuels, as demonstrated here, indicates that this factor should be taken into account when planning public intervention. This observation is supplemented by the economic context (localities with higher incomes and wealth indicators tend to have lower solid fuel consumption). On this basis, it can be assumed that some municipalities located around Kraków, which is the socio-economic center of the region, are more attractive in terms of suburbanization processes and attract a larger number of new, more affluent residents. This area represents a research gap and requires additional research, the results of which may be very valuable in the context of regional policy planning.

The second key observation from our research is related to the first. The starting point is our proposed division into three groups of municipalities: cluster 0, i.e., municipalities with low wealth and high dependence on solid fuels; cluster 1, i.e., municipalities with average wealth and moderate consumption of solid fuels; and cluster 2, i.e., municipalities with high wealth and low dependence on solid fuels. The municipalities included in cluster 2 (Mogilany, Niepołomice, Zielonki, Wielka Wieś) are areas that attract new residents, with policies that favor entrepreneurship and expand the infrastructure necessary for the creation of new residential developments. In these places, residents use higher-standard heating devices. Our observations contribute to further research related to the intensity of suburbanization processes. Another interesting direction for future research is the relationship between the number of existing residents of municipalities and new residents. Public repositories do not contain such data, so a more nuanced and complex approach is needed. However, the two types of behavioral patterns we have identified, concerning “old” and “new” automated solid fuel stoves, can be considered part of this nuanced approach.

Regardless of future research directions and gaps in access to certain public data, our paper shows important directions for future intervention. First of all, it should be noted that even municipalities located at a similar distance from Kraków, which we analyzed, show significant differences in terms of heating equipment characteristics and wealth. This means that when planning public intervention in the field of thermal modernization, aid programs, etc., municipalities should be treated individually. Meanwhile, the current support offer is the same for all municipalities throughout Poland, as exemplified by the Clean Air program. This program provides financial support for the replacement of heating sources and thermal modernization, but in most cases requires a fairly high own contribution. This means that it is used by homeowners with a certain level of wealth. In less affluent municipalities, as can be concluded from our analysis, this process is slower. The challenge is to find a solution that will also help those municipalities where residents’ incomes are lower.

The study has limitations related to several factors. The first one is related to the limited period from which the air quality data originate. Another limitation concerns property data in municipalities, related to the ecological fallacy, which consists of inferring the characteristics of individuals based on data concerning the groups to which they belong. The results indicate that in lower-income households, the financial situation has a significant impact on the choice of heating source, but it is possible that higher-income residents still use solid fuel stoves for heating. Another risk of data distortion may result from the fact that data on the number of stoves from 2022 was included. The authors, in justifying their decisions regarding the research procedure related to the database, were aware of this risk and made every effort to minimize it.

7. Conclusions

Our paper has shown that there are a number of predictors that determine air quality, but one of the most important ones is wealth and, consequently, the type of heating sources used. By shedding light on these connections, our publication provides decision-makers with useful insights into the proposed solutions. The mention of decision-makers is no coincidence. In the case described in the paper, it can be assumed that the heating source used is not only the result of residents’ decisions, but also their financial status. Spatial analysis complements this picture. This proves that sustainable policy design should be based on nuanced premises.

More detailed research should be conducted on how individual local governments support residents in replacing heating sources and thermal modernization, as there are other factors besides the clearly demonstrated correlation between income and better air quality in this publication. In our analysis, we identified municipalities which, despite their above-average wealth, have a relatively high percentage of old appliances and poor air quality. Furthermore, the distance of municipalities from the regional capital is of little significance. Our three-factor analysis, whose vertices are determined by air quality, the number of solid fuel heating sources, and the wealth of residents, therefore needs to be supplemented. This will require complex methods, but the following publication can serve as an important basis for their implementation.

The energy system, which consists of the way households are heated, reflects the state of transformation not only in terms of technology but also in terms of the economy. Poland, like other Central European countries, has experienced significant progress in both areas in recent years. However, technological development, which includes heating devices, and economic development are uneven. This can be seen even in such a small area as the Kraków agglomeration. We have clearly demonstrated this in the publication. The novelty of this publication lies not so much in demonstrating the relationship between the wealth of residents and air quality, but in showing the usefulness of commonly available data sources, their synergy, and the development of precise guidelines for decision-makers. These recommendations, in the form of maps, drawings, and clusters, are a valuable contribution to public policymaking. Since there is widespread agreement that every effort should be made to improve air quality, it is worth designing measures in such a way as to spend the available funds and resources as effectively as possible. The results provided by the authors can effectively help in this regard.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.W., M.S., M.Z. and T.D.; methodology, E.W., M.S., M.Z. and T.D.; software, E.W., M.S., M.Z. and T.D.; validation, E.W., M.S., M.Z. and T.D.; formal analysis, E.W., M.S., M.Z. and T.D.; investigation, E.W., M.S., M.Z. and T.D.; resources, E.W., M.S., M.Z. and T.D.; data curation, E.W., M.S., M.Z. and T.D.; writing—original draft preparation, E.W., M.S., M.Z. and T.D.; writing—review and editing, E.W., M.S., M.Z. and T.D.; visualization, E.W., M.S., M.Z. and T.D.; supervision, T.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was financed by the AGH University of Krakow, Faculty of Geology, Geophysics and Environmental Protection and Faculty of non-ferrous metals as part of the statutory projects, and by the program Excellence initiative-research university for the AGH University of Krakow.

Data Availability Statement

The Airly sensor data analyzed in this study were obtained under a free academic API key issued by Airly S.A. in accordance with the Airly API Service Terms. These terms restrict redistribution of the raw data and prohibit sharing of the API key with third parties. Consequently, the underlying data are not publicly available. Researchers can obtain current data directly from Airly by registering for an academic research API key at https://airly.org (accessed on 12 December 2025) (see Airly API Terms of Service). Other datasets used in this study can be made available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used OpenAI models (o3, GPT-4o) and DeepL for translation and language proofreading, and marginally for code assistance, namely, to generate plotting code for isoprobability ellipsoids on the PC1/PC2 plane. The authors have reviewed and edited all outputs and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

This section contains the data used as primary socioeconomic and technological descriptors in the study.

Table A1.

Information on heating sources in selected municipalities around Kraków.

Table A1.

Information on heating sources in selected municipalities around Kraków.

| Municipality | Number of Solid Fuel Furnaces | Number of Furnaces with Automatic Feeders | Number of All Heating Sources in the Municipality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liszki | 3486 | 642 | 8554 |

| Zabierzów | 5615 | 825 | 16,675 |

| Wielka Wieś | 2687 | 356 | 8098 |

| Zielonki | 3758 | 512 | 12,715 |

| Michałowice | 2543 | 339 | 6295 |

| Kocmyrzów-Luborzyca | 3239 | 509 | 8021 |

| Igołomia-Wawrzeńczyce | 1618 | 426 | 3276 |

| Niepołomice | 5227 | 501 | 15,455 |

| Biskupice | 2277 | 315 | 4899 |

| Wieliczka | 9669 | 1103 | 26,434 |

| Świątniki Górne | 1995 | 272 | 3628 |

| Mogilany | 3251 | 445 | 7841 |

| Skawina | 5325 | 1301 | 8766 |

| Czernichów | 4802 | 1256 | 7957 |

| Koniusza | 1809 | 383 | 3166 |

| Jerzmanowice-Przeginia | 2595 | 350 | 4969 |

| Raciechowice | 2602 | 592 | 3325 |

| Wiśniowa | 2993 | 700 | 3980 |

| Sułkowice | 3285 | 584 | 5649 |

| Myślenice | 9248 | 1461 | 17,262 |

| Gdów | 4122 | 598 | 8093 |

| Krzeszowice | 7498 | 1065 | 14,945 |

| Brzeźnica | 2679 | 643 | 4925 |

| Proszowice | 3461 | 1236 | 5188 |

Table A2.

Tax revenue per capita of the municipality for 2021, for 2022 and individual wealth index for 2023 in selected municipalities around Kraków Source: Ministry of Finance 2023, 2024 and 2025 [43,44,45].

Table A2.

Tax revenue per capita of the municipality for 2021, for 2022 and individual wealth index for 2023 in selected municipalities around Kraków Source: Ministry of Finance 2023, 2024 and 2025 [43,44,45].

| Municipality | Tax Revenue Per Capita 2021 (in PLN) | Tax Revenue Per Capita 2022 (in PLN) | Individual Wealth Index 2023 (in PLN) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liszki | 203,016 | 268,542 | 481,866 |

| Zabierzów | 332,440 | 383,212 | 596,921 |

| Wielka Wieś | 382,667 | 425,488 | 673,101 |

| Zielonki | 280,525 | 355,740 | 596,223 |

| Michałowice | 256,390 | 291,350 | 502,538 |

| Kocmyrzów-Luborzyca | 206,169 | 222,416 | 438,292 |

| Igołomia-Wawrzeńczyce | 151,719 | 190,179 | 411,088 |

| Niepołomice | 338,745 | 382,983 | 589,878 |

| Biskupice | 152,668 | 185,805 | 406,234 |

| Wieliczka | 225,543 | 266,221 | 470,875 |

| Świątniki Górne | 246,041 | 303,154 | 465,698 |

| Mogilany | 259,937 | 343,850 | 585,063 |

| Skawina | 263,482 | 310,776 | 529,399 |

| Czernichów | 166,792 | 217,430 | 448,929 |

| Koniusza | 130,959 | 132,089 | 363,926 |

| Jerzmanowice-Przeginia | 138,917 | 178,093 | 413,832 |

| Raciechowice | 120,863 | 147,313 | 284,303 |

| Wiśniowa | 108,883 | 120,905 | 294,570 |

| Sułkowice | 123,797 | 155,889 | 379,543 |

| Gmina Myślenice | 199,205 | 245,343 | 491,285 |

| Gdów | 174,806 | 221,968 | 439,649 |

| Krzeszowice | 183,519 | 226,435 | 479,944 |

| Brzeźnica | 130,694 | 165,048 | 375,416 |

| Proszowice | 136,288 | 176,188 | 414,581 |

References

- Oberdörster, G.; Utell, M.J. Ultrafine particles in the urban air: To the respiratory tract—And beyond? Environ. Health Perspect. 2002, 110, A440–A441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State of Global Air 2024; EEA Report: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2024.

- Afghan, F.R.; Patidar, S.K. Health impacts assessment due to PM2.5, PM10 and NO2 exposure in National Capital Territory (NCT) Delhi. Pollution 2020, 6, 115–126. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, F.; Li, S.; Liang, Z.; Huang, A.; Wang, Z.; Shen, J.; Sun, F.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, S. Analysis of Spatial Heterogeneity and the Scale of the Impact of Changes in PM2.5 Concentrations in Major Chinese Cities between 2005 and 2015. Energies 2021, 14, 3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency. Health Impacts of Air Pollution in Europe. 2021. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/publications/air-quality-in-europe-2021/health-impacts-of-air-pollution-in-europe-2021 (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Nieuwenhuijsen, M.; de Nazelle, A.; Garcia-Aymerich, J.; Khreis, H.; Hoffmann, B. Shaping urban environments to improve respiratory health: Recommendations for research, planning, and policy. Lancet Respir. Med. 2024, 12, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Rethinking Urban Sprawl: Moving Towards Sustainable Cities; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliu-Barton, M.; Mejino-López, J. How Much Does Europe Pay for Clean Air? Working Paper No. 15/2024; Bruegel, Brussels 2024. Available online: https://www.bruegel.org/working-paper/how-much-does-europe-pay-clean-air (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- World Bank. Air Quality Management—Poland. 2019. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10986/31531 (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Malopolska Region. Resolution No. XVIII/243/16 of the Assembly of Małopolskie Voivodship of 15 January 2016 on the Introduction in the Area of the Municipality of Krakow of Restrictions on the Operation of Installations in Which Fuel Is Burned. 2016. Available online: https://edziennik.malopolska.uw.gov.pl/WDU_K/2016/812/akt.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Kaczmarczyk, M.; Sowiżdżał, A. Environmental friendly energy resources improving air quality in urban area. Energy Rep. 2024, 11, 3383–3394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorczyca, K.; Zozulia, D. “We have the right to breathe clean air”—Mobilising communities in the fight for good air quality. Environ. Plan. C Politics Space 2025, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarnobilska, E.; Bulanda, M.; Bulanda, D.; Mazur, M. The Influence of Air Pollution on the Development of Allergic Inflammation in the Airways in Krakow’s Atopic and Non-Atopic Residents. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grobelski, T. Changing the coal status quo through scalar practices: The anti-smog movement’s contributions to Polish energy transition. Environ. Plan. C Politics Space 2025, 43, 1369–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zareba, M.; Danek, T. A Novel Methodology for Explainable Artificial Intelligence Integrated with Geostatistics for Air Pollution Control and Environmental Management. Ecol. Inform. 2025, 92, 103450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipiec, D.; Lipiec, P.; Danek, T. Urban–Rural PM2.5 Dynamics in Kraków, Poland: Patterns and Source Attribution. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zareba, M.; Danek, T. Big Data Analysis of Long-Term Anthropogenic and Short-Term Natural Factors Influencing Air Pollution in Moderate Climate Zones: Implications for Sustainable Development. In Environmental Science and Engineering; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zareba, M.; Węglińska, E.; Danek, T. Air Pollution Seasons in Urban Moderate Climate Areas Through Big Data Analytics. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 52733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zareba, M.; Cogiel, S.; Danek, T.; Węglińska, E. Machine Learning Techniques for Spatio-Temporal Air Pollution Prediction to Drive Sustainable Urban Development in the Era of Energy and Data Transformation. Energies 2024, 17, 2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zareba, M.; Długosz, H.; Danek, T.; Węglińska, E. Big-Data-Driven Machine Learning for Enhancing Spatiotemporal Air Pollution Pattern Analysis. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danek, T.; Węglińska, E.; Zareba, M. The Influence of Meteorological Factors and Terrain on Air Pollution Concentration and Migration: A Geostatistical Case Study from Krakow, Poland. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zareba, M.; Danek, T. Analysis of Air Pollution Migration During COVID-19 Lockdown in Krakow, Poland. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2022, 22, 210275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danek, T.; Zareba, M. The Use of Public Data from Low-Cost Sensors for the Geospatial Analysis of Air Pollution from Solid Fuel Heating During the COVID-19 Pandemic Spring Period in Krakow, Poland. Sensors 2021, 21, 5208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrer, A.P.; Heft-Neal, S. Higher air pollution in wealthy districts of most low- and middle-income countries. Nat. Sustain. 2024, 7, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, B.; Swarnakar, P. How fair is our air? The injustice of procedure, distribution, and recognition within the discourse of air pollution in Delhi, India. Environ. Sociol. 2022, 9, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederiks, E.R.; Stenner, K.; Hobman, E.V. The Socio-Demographic and Psychological Predictors of Residential Energy Consumption: A Comprehensive Review. Energies 2015, 8, 573–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherfas, J. Skeptics and visionaries examine energy saving. Science 1991, 251, 154–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutzenhiser, L. Social and behavioral aspects of energy use. Annu. Rev. Energy Environ. 1993, 18, 247–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wüstenhagen, R.; Wolsink, M.; Bürer, M.J. Social acceptance of renewable energy innovation: An introduction to the concept. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 2683–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huckebrink, D.; Bertsch, V. Integrating Behavioural Aspects in Energy System Modelling—A Review. Energies 2021, 14, 4579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokołowski, J.; Lewandowski, P.; Kiełczewska, A.; Bouzarovski, S. A multidimensional index to measure energy poverty: The Polish case. Energy Sources Part B Econ. Plan. Policy 2020, 15, 92–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przywojska, J.; Podgórniak-Krzykacz, A.; Kalisiak-Mędelska, M.; Rącka, I. Energy Poverty in Poland: Drivers, Measurement and National Policy. Energies 2025, 18, 2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Energy Law Act. Ustawa z Dnia 10 Kwietnia 1997 r. Prawo Energetyczne. 1997. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU19970540348/U/D19970348Lj.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Szczygieł, O.; Wojciechowska, A.; Krupin, V.; Skorokhod, I. Regional Dimensions of Energy Poverty in Households of the Masovian Voivodeship in Poland: Genesis, Factors, Self-Assessment. Energies 2024, 17, 6114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, X.; Feng, J.; Song, M. The impact of air pollution on household vulnerability to poverty: An empirical study from household data in China. Econ. Anal. Policy 2024, 85, 1369–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation of the Minister of Development of 29 April 2020 Amending the Regulation on the Detailed Scope and Forms of the Energy Audit and Part of the Renovation Audit, Templates of Audit Cards, as well as the Algorithm for Assessing the Profitability of a Thermomodernization Project. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20200000879 (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Poland’s Energy Policy 2040. Announcement of the Minister of Climate and Environment of 2 March 2021, on the State Energy Policy Until 2040. Warsaw 2021, Monitor Polski, poz. 264. 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/klimat/polityka-energetyczna-polski (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Jagiełło, P.; Struzewska, J.; Jeleniewicz, G.; Kamiński, J.W. Evaluation of the Effectiveness of the National Clean Air Programme in Terms of Health Impacts from Exposure to PM2.5 and NO2 Concentrations in Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, M. _missRanger: Fast Imputation of Missing Values_, R Package Version 2.6.1; CRAN: Vienna, Austria, 2024. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=missRanger (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Sejm of the Republic of Poland. Law of 28 October 2020 Amending the Law on Support for Thermal Modernization and Renovation and Some Other Laws. 2020. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20200002127 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Ministry of Climate and Environment. “Clean Air” Priority Programme. 2025. Available online: https://czystepowietrze.gov.pl/wez-dofinansowanie/dokumenty-programowe/dokumenty-obowiazujace/00_ppcp_z_oznak._fm_zal.1_do_uchwaly.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Central Building Emission Register. Available online: https://zone.gunb.gov.pl/pl/masz-nowe-zrodlo-ogrzewania-lub-zmieniasz-piec-zloz-deklaracje-ceeb (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Ministry of Finance. Indicator G—Basic Tax Revenue per Capita of the Municipality Adopted for the Calculation of the Equalization Subsidy for 2024, Realized Revenue for 2021. 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/finanse/wskazniki-dochodow-podatkowych-gmin-powiatow-i-wojewodztw-na-2023-r (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Ministry of Finance. Indicator G—Basic Tax Revenue per Capita of the Municipality Adopted for the Calculation of the Equalization Subsidy for 2024, Realized Revenue for 2022. 2024. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/finanse/wskazniki-dochodow-podatkowych-gmin-powiatow-i-wojewodztw-na-2024-r (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Ministry of Finance. Revenues of Local Government Units in 2025, Individual Wealth Index for 2023. 2025. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/finanse/dochody-jednostek-samorzadu-terytorialnego-w-2025-roku (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- McKinney, W. Data Structures for Statistical Computing in Python. In Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference, Austin, TX, USA, 28 June–3 July 2010; pp. 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, K. Note on regression and inheritance in the case of two parents. Proc. R. Soc. Lond 1895, 58, 240–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waskom, M. Seaborn: Statistical data visualization. J. Open Source Softw. 2021, 6, 3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seabold, S.; Perktold, J. Statsmodels: Econometric and statistical modeling with Python. In Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference, Austin, TX, USA, 28 June–3 July 2010; pp. 92–96. [Google Scholar]

- MacQueen, J. Some methods for classification and analysis of multivariate observations. Proc. Fifth Berkeley Symp. Math. Stat. Probab. 1967, 1, 281–297. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseeuw, P.J. Silhouettes: A graphical aid to the interpretation and validation of cluster analysis. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 1987, 20, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samek, L.; Stegowski, Z.; Furman, L.; Styszko, K.; Zajusz-Zubek, E.; Michalik, J. Seasonal variation in chemical composition of PM2.5 in Kraków, Poland. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2017, 228, 3483. [Google Scholar]

- Regional Environmental Inspectorate in Kraków. Air Quality in Krakow: Summary of Research Results. 2020. Available online: https://krakow.wios.gov.pl/2020/09/jakosc-powietrza-w-krakowie-podsumowanie-wynikow-badan/ (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Bogacki, M.; Widziewicz, K.; Puta, R. Low-stack emission as the dominant factor of air pollution in Kraków. E3S Web Conf. 2018, 44, 00053. [Google Scholar]

- Rogula-Kozłowska, W.; Majewski, G.; Rogula-Kopiec, P.; Pastuszka, J.S.; Mathews, B.; Sówka, I. Contribution of residential heating and traffic to PM2.5 during and after COVID-19 restrictions in Kraków, Poland. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11492. [Google Scholar]

- Zareba, M. Assessing the Role of Energy Mix in Long-Term Air Pollution Trends: Initial Evidence from Poland. Energies 2025, 18, 1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. Poland, Oil Supply. 2025. Available online: https://www.iea.org/countries/poland/oil#where-does-poland-get-its-oil (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- IEA. Poland, Oil Supply. Natural Gas Supply. 2025. Available online: https://www.iea.org/countries/poland/natural-gas (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- IEA. Poland, Coal Supply. 2025. Available online: https://www.iea.org/countries/poland/coal (accessed on 18 December 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.