Abstract

The photovoltaic–energy storage–direct current–flexibility (PEDF) system provides an integrated pathway for low-carbon and intelligent building energy management by combining on-site PV generation, electrical storage, DC distribution, and flexible load control. This paper reviews recent advances in these four modules and synthesizes quantified benefits reported in real-world deployments. Building-scale systems typically integrate 20–150 kW PV and achieve ~10–18% energy-efficiency gains enabled by DC distribution. Industrial-park deployments scale to 500 kW–5 MW, with renewable self-consumption often exceeding 50% and CO2 emissions reductions of ~40–50%. Community-level setups commonly report 10–15% efficiency gains and annual CO2 reductions on the order of tens to hundreds of tons. Key barriers to large-scale adoption are also discussed, including multi-energy coordination complexity, high upfront costs and uncertain business models, limited user engagement, and gaps in interoperability standards and supportive policies. Finally, we outline research and deployment priorities toward open and interoperable PEDF architectures that support cross-sector integration and accelerate the transition toward carbon-neutral (and potentially carbon-negative) built environments.

1. Introduction

The past decade has seen a dramatic surge in extreme weather events—such as floods, droughts, heatwaves, and super typhoons—posing serious threats to energy security, public health, and economic stability [1]. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) warns that limiting global warming to 1.5 °C requires greenhouse gas emissions to peak by 2025 and fall by 43% by 2030 [2]. Exceeding this threshold may trigger irreversible tipping points in the climate system, highlighting the urgent need for deep energy transitions worldwide.

Among various decarbonization strategies, the global energy landscape is rapidly shifting toward renewables. Solar photovoltaic (PV) systems, in particular, have emerged as a leading source of clean energy due to their scalability, declining costs, and ease of deployment [3]. However, the variability and intermittency of solar generation present serious challenges for grid reliability and demand–supply matching, especially in urban areas with dense loads and limited space.

The building sector accounts for nearly 34% of global final energy consumption [4]. It also serves as a key frontier for implementing decentralized energy systems. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), meeting net-zero targets by 2050 requires buildings to undergo deep electrification and integrate high shares of distributed renewables, smart controls, and energy storage systems [5]. Urban buildings face growing pressures from electrified services like Heating Ventilation and Air Conditioning (HVAC), electric vehicle (EV) charging, and data centers, further straining existing infrastructure [6]. These shifts call for advanced, flexible, and local energy solutions.

One promising direction is the integration of photovoltaics, energy storage, direct current (DC) power distribution, and flexible load technologies into a unified architecture known as the PEDF system [7]. The system leverages rooftop solar, localized storage, DC-based power flow, and smart load coordination to form an intelligent and resilient energy network. Compared to conventional building energy systems, PEDF offers higher energy utilization efficiency, reduced conversion losses, and greater compatibility with modern loads and bidirectional power flows.

While previous studies have explored various components of building-level energy systems—such as photovoltaic generation, energy storage integration, direct current distribution, and flexible demand response—these technologies have often been examined in isolation or under narrow application scopes [8,9]. In contrast, this review adopts a holistic perspective by integrating these elements under the unified PEDF framework. This approach enables a more systematic evaluation of their synergies, technical barriers, and implementation outcomes in practical scenarios.

Review Methodology

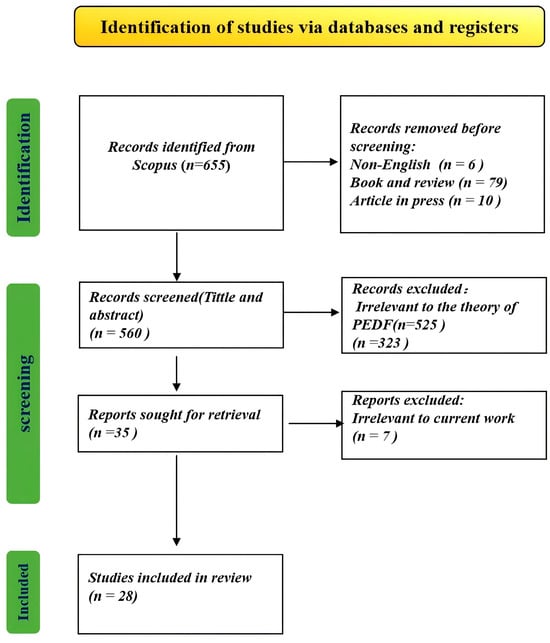

This review adopts a systematic approach to identify, screen, and analyze the existing literature on PEDF system. Relevant publications were retrieved from primary scientific databases, including Elsevier Scopus, Web of Science, SpringerLink, IEEE Xplore Digital Library, and Google Scholar.

The literature search was conducted using combinations of keywords such as “Photovoltaic–Energy Storage integration”, “DC distribution systems in buildings”, “flexible demand response”, “smart building energy systems”, and “source–grid–load–storage coordination”. Articles were selected based on their technical relevance, novelty, and direct connection to the PEDF framework. Subdomains included PV generation technologies, energy storage optimization, DC distribution architectures, demand-side flexibility control, and system integration strategies for low-carbon buildings and microgrids.

To ensure consistency and representativeness, the review considered peer-reviewed English-language journal articles published between 2015 and 2025, with particular emphasis on studies from 2020 to 2025, reflecting the latest advances in AI-driven energy management and multi-energy coordination. Conference papers, editorials, and non-technical reports were excluded to maintain academic rigor. The overall methodology based on articles selection criteria is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Model of the search selection criteria.

This review addresses these gaps by systematically analyzing the architecture, enabling technologies, and deployment scenarios of the system in the building sector. We first outline the evolution and key components of the system, followed by an in-depth discussion of implementation practices in single buildings, industrial parks, and community microgrids. We then examine major technical and institutional challenges and conclude by identifying future research and policy directions to facilitate PEDF deployment at scale.

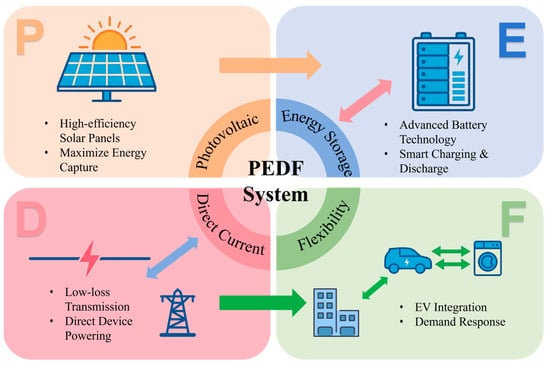

2. State of the Art of PEDF System

The PEDF system represents an innovative approach to integrating renewable energy generation, energy storage, and efficient electricity delivery. It is designed to enhance energy efficiency, reliability, and sustainability, particularly in urban environments. As illustrated in Figure 2, a typical PEDF-based building distribution system combines photovoltaic modules, energy storage units, DC distribution networks, and flexible power flow technologies. By integrating these components into a unified architecture, the system offers a comprehensive solution to the complex challenges of modern energy systems.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the proposed PEDF system architecture.

In recent years, the systems have gained significant attention not only in buildings and energy hubs but also in the broader energy–mobility nexus. In the transportation sector, PEDF-enabled architectures are being explored in EV charging stations, vehicle-to-grid (V2G) systems, and multi-energy transportation depots, where the integration of PV, stationary storage, and DC-based fast-charging infrastructure enables low-carbon and resilient energy flows. In particular, bidirectional EVs are increasingly treated as mobile storage units that participate in the system both as flexible loads and distributed energy resources.

Concurrently, PEDF concepts are also being embedded into rail transit power systems, airport microgrids, and urban transport centers, where unified DC infrastructures and coordinated dispatch of storage and flexible demands can improve energy utilization and reduce operational carbon intensity. These advancements indicate that PEDF is evolving into a cross-sectoral integration framework, blurring the boundaries between power systems, buildings, and transportation.

Driven by policy incentives and decarbonization goals, ongoing research efforts focus on architecture optimization, coordinated scheduling algorithms, AI-driven control strategies, and protection mechanisms tailored to multi-node PEDF environments.

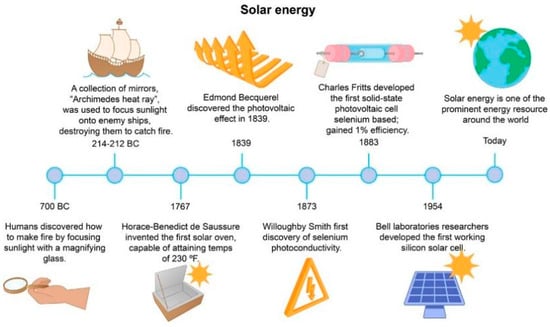

2.1. Current Status of Photovoltaic

The core objective of the system is to achieve energy self-sufficiency in buildings through localized PV generation, storage, and flexible scheduling. Within this system, PV technology plays the role of the “energy producer,” whose efficiency, cost, and compatibility with DC distribution directly impact overall system performance. In urban environments characterized by limited space and diverse energy demands, the adaptability and innovation of the systems are critical to realizing efficient, resilient, and sustainable energy infrastructure. As shown in Figure 3, the utilization of solar energy has evolved from early-stage thermal applications to advanced photovoltaic systems. Over time, technological advances in materials, conversion efficiency, and integration capability have driven PV systems to become the dominant form of renewable energy in PEDF applications.

Figure 3.

Evolution of Solar Energy Utilization Toward Photovoltaic Energy Systems [10].

The design of the system can be flexibly adapted to the unique constraints of urban landscapes. For instance, PV integration within cities is commonly achieved through Building-Integrated Photovoltaics (BIPV) and Building-Applied Photovoltaics (BAPV). BIPV replaces traditional building materials with high-efficiency PV modules integrated into facades, roofs, and windows, serving dual purposes of aesthetics and energy generation [11]. In contrast, BAPV involves the external installation of PV panels on existing building structures, providing a cost-effective solution for urban retrofitting without requiring large-scale redesign [12]. These two approaches enable the systems to maximize renewable energy capture while complying with physical and regulatory constraints in dense urban areas. Although BIPV aligns better with long-term urban planning goals, the actual choice between these approaches depends on the selected PV modules. A reasonable combination of these technologies plays a key role in ensuring both the efficiency and visual appeal of urban energy systems.

In the past three years, advancements in PV technology have significantly enhanced the adaptability of the systems, particularly by expanding the range of available PV modules suited for various urban applications. However, current market standards for evaluating PV cell efficiency are inconsistent. This inconsistency arises because PV module efficiency is defined as the ratio of output power per unit area to incident irradiance, and results measured under varying illumination conditions lack universal comparability. Table 1 lists common PV module efficiencies, where the efficiency values are obtained under the standard test conditions specified in IEC 60904-1 [13], i.e., irradiance of 1 kW/m2 and cell temperature of 25 °C.

Table 1.

Typical Commercial Module Efficiencies for Building Applications under Standard Test Conditions [14].

Crystalline silicon solar cells currently dominate the global PV market, providing crucial support for sustainable energy transition due to their high conversion efficiency and low carbon emissions [15]. Based on crystal structure, they can be classified as monocrystalline silicon (m-Si) or multi crystalline silicon (mc-Si). Monocrystalline silicon PV cells, with conversion efficiencies exceeding 24%, along with modules achieving efficiencies above 20%, hold a leading market position [16]. Notably, to further enhance the power generation performance of PV systems, bifacial solar cells and modules have been increasingly adopted in utility-scale applications in recent years. This technology allows solar radiation to be absorbed from both the front and rear sides of the cell, offering significant improvements in overall energy yield compared to traditional monofacial cells.

Unlike crystalline silicon modules, thin-film PV modules consist of transparent and opaque conductive photovoltaic material layers applied in multiple thin-film layers onto substrates [17]. Thin-film solar cell technologies have emerged as promising alternatives to traditional crystalline silicon systems due to their low material consumption, lightweight properties, and mechanical flexibility—features particularly valuable for building-integrated applications within the systems.

Progress in thin-film technologies is not limited to conventional materials since emerging trends include the integration of perovskite layers and the advent of copper zinc tin sulfide (CZTS). Whether as single-junction cells or in tandem configurations combined with silicon or other thin films, these developments are expected to surpass the efficiency limits of single-junction cells by more effectively utilizing the solar spectrum [18,19]. The inherent flexibility and substrate compatibility of thin-film cells make them particularly well-suited for urban systems, where spatial constraints and aesthetic considerations are paramount. Innovations in thin-film technologies have enabled perovskite-silicon heterojunction cells to achieve record conversion efficiencies of 31.3%, while providing lightweight and flexible form factors [20]. Among emerging PV materials, perovskites have garnered significant research interest due to their high efficiency and versatile structures. Meanwhile, CZTS, composed of non-toxic and earth-abundant elements, is considered a promising candidate for future green PV technologies.

Heterojunction solar cells combine two semiconductor materials to form a junction. Silicon heterojunction (SHJ) technology merges the advantages of monocrystalline silicon and thin-film materials by depositing functional thin-film layers on crystalline silicon substrates to enhance cell performance. These thin films are typically made of amorphous silicon or perovskite materials, further optimizing interface passivation and photoelectric conversion efficiency. Recent studies indicate that SHJ modules have a theoretical efficiency limit approaching 29.4%, with commercial production efficiencies exceeding 27.3%, remaining the industry standard [21].

In urban environments, where space is limited, PV systems require higher power density per unit area [22]. SHJ modules, with their high efficiency and excellent low-light response, offer advantages for building-integrated photovoltaics (BIPV) applications such as photovoltaic curtain walls and transparent roofs [23]. Innovations in bifacial and semi-transparent modules enable double-sided energy harvesting and improved daylighting, respectively. Bifacial modules can capture additional energy from reflected light, while semi-transparent modules generate electricity while maintaining building transparency—attributes increasingly important for the system in modern urban architecture, aligning energy and aesthetic demands [24].

These advancements in PV efficiency and form factor have fundamentally altered the building energy equation, transforming façades from passive envelopes into active, modular generators within the framework. While the scalability of modern modules theoretically allows for customized integration across diverse urban morphologies, treating PV capacity as a standalone solution overlooks a critical systemic vulnerability. In practical urban retrofits, we often observe that maximizing generation capacity without a corresponding energy buffer exacerbates grid stress rather than alleviating it, primarily due to the temporal mismatch between solar peak production and user demand. Consequently, the realization of a truly flexible, low-carbon building hinges not merely on how much energy can be harvested, but on how effectively this energy can be shifted in time. This operational imperative shifts the focus from generation to management, making advanced energy storage systems the indispensable backbone of the next-generation PEDF architecture.

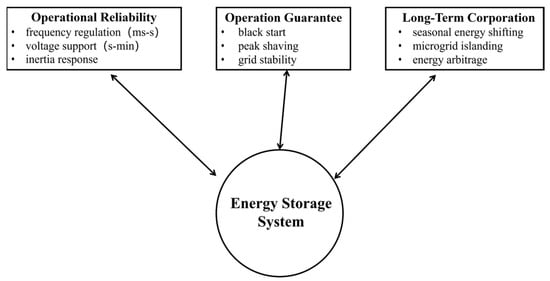

2.2. Current Status of Energy Storage Systems

In PEDF architectures, energy storage acts as the strategic fulcrum, effectively decoupling stochastic PV generation from rigid user demand. Its integration defines not just energy efficiency, but the system’s economic resilience. Recently, the field has moved beyond a “one-size-fits-all” approach, evolving into a diversified landscape of electrochemical, mechanical, and hydrogen technologies [25]. Each category now addresses specific operational niches—from rapid frequency regulation to seasonal shifting—allowing for precise matching between technical characteristics and building requirements.

Table 2 summarizes the diverse storage requirements within the systems. As illustrated in Figure 4, these requirements can be broadly classified into three core application categories: power regulation, operational support, and long-duration coordination. Each category emphasizes different technical aspects, resulting in varying demands on storage technologies in terms of response speed, energy density, and sustained energy delivery capabilities. Therefore, the selection of appropriate storage technologies must carefully consider their suitability for specific application scenarios to achieve an optimal balance between performance and cost-effectiveness.

Table 2.

Specific Energy Storage Requirements for PEDF Technologies.

Figure 4.

Three Typical Application Scenarios of Energy Storage Systems in PEDF System.

After decades of technological evolution, traditional lithium-ion batteries have established dominance in the mainstream energy storage market due to their mature cost control and energy density advantages [32]. However, when we examine the stringent requirements of the system for high response frequency and long service life, it is clear that the existing technology path logic faces new challenges, which drives research to expand to more promising material systems.

Sodium-ion batteries are a key path to emerge in this context. Thanks to the abundance of sodium and its superior safety, this battery system is no longer seen as just a shadow of lithium, but as a complementary solution, showing a high commercial fit in the field of large-scale energy storage and short-distance transportation [33]. In our actual observation, its cycle life of more than 3000 times not only greatly reduces the life cycle cost of residential optical storage system, but also provides reliable physical support for flexible “peak clipping and valley filling” [34].

At the same time, solid-state battery technologies with higher levels of safety represent researchers ‘dual pursuit of energy density limits and system robustness [35]. These emerging solutions are at a critical transition from laboratory to demonstration engineering, and their demonstrated technical toughness is gradually being transformed into the underlying foundation for supporting the long-term stable operation of the system.

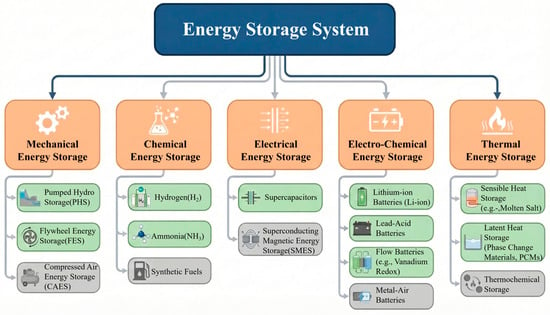

The system relies on PV generation as its core energy supply. However, a fundamental contradiction exists between the intermittent and fluctuating nature of PV output and the continuous, stable characteristics of electricity demand. Relying solely on electrochemical storage is insufficient to meet the full-spectrum, all-cycle energy regulation needs of the system. Therefore, it is essential to integrate physical and hydrogen-based energy storage technologies to form a multi-timescale, multidimensional storage architecture. Figure 5 Classification of energy storage technologies across electrical, electrochemical, mechanical, thermal, and chemical domains. These categories differ in terms of energy density, response time, scalability, and system complexity, forming the foundation for further discussion on system-specific challenges in PEDF applications.

Figure 5.

Classification of energy storage technologies based on energy forms.

Among physical energy storage technologies deployed at grid scale (>1 MWh), pumped hydro storage (PHS) remains the dominant solution, accounting for approximately 99% of the total global energy storage capacity, with an installed power capacity exceeding 181 GW [36]. Long-term operational data have demonstrated its technical advantages, including an ultra-long service life (20–40 years) and round-trip energy efficiency as high as 90% [37]. However, its application is geographically constrained, requiring specific topographies with sufficient elevation differences (typically >200 m) and stable water sources.

Within the electrochemical landscape, lithium-ion batteries have solidified their position as a research cornerstone, underpinned by their superior energy density (150–500 Wh/L) and an exceptional round-trip efficiency of up to 95% [38]. However, this dominance is increasingly scrutinized under the lens of operational safety and economic sustainability; inherent risks of electrolyte volatility, coupled with the geopolitical and supply chain sensitivities of lithium, cobalt, and nickel, introduce significant cost uncertainties that necessitate a broader technological perspective [39]. Where lithium-ion excels in sustained output, a distinct class of short-duration storage—comprising supercapacitors, flywheels, and superconducting magnetic energy storage (SMES)—addresses the need for instantaneous responsiveness. These systems prioritize power over energy, offering rapid-fire regulation that electrochemical cells struggle to match, yet their utility remains geographically and temporally confined by a characteristically low energy capacity (typically <1 MWh) [40]. Bridging the gap between these high-power bursts and long-term grid stability is Compressed Air Energy Storage (CAES). By offering a modular architecture that scales from distributed (<1 MWh) to grid-level (>1 MWh) applications, CAES presents a versatile alternative to traditional batteries. The current research frontier has thus shifted toward adiabatic configurations, aiming to recapture thermal energy and mitigate the geological constraints that have historically hampered its commercial footprint.

At the grid scale, battery and hydrogen storage systems form a symbiotic pair, bridging the gap between instantaneous stability and seasonal resilience. While lithium-ion batteries provide the high-frequency agility and efficiency required for intra-day balancing, their economic scaling is inherently constrained by cycle degradation and energy density limits beyond a 24 h horizon. Conversely, hydrogen storage—despite the efficiency penalties of the water electrolysis-fuel cell loop—leverages its superior energy density and decoupled power/energy scaling to enable the seasonal shifting of renewable surpluses. This synergy between short-term precision and long-duration capacity establishes the multi-timescale coordination architecture essential for taming the volatility of a high-penetration renewable grid.

Hydrogen storage technologies include high-pressure gaseous storage, liquid hydrogen storage, and solid-state storage. High-pressure gaseous hydrogen storage is technologically mature and offers fast response, but suffers from limited energy density and the risk of gas leakage [41]. Liquid hydrogen offers significantly higher volumetric energy density; however, the liquefaction process requires substantial energy input and extremely low temperatures, limiting its practical deployment [42]. Solid-state hydrogen storage features enhanced safety and relatively high energy density but faces challenges such as low hydrogen release/absorption efficiency and high material costs [43].

However, the overall energy efficiency of hydrogen storage systems remains relatively low (approximately 30–40%), with long conversion chains and high initial capital investment, limiting their widespread deployment in current systems [44]. To address the temporal and spatial mismatch inherent in photovoltaic generation, it is essential for the system to adopt a multi-tiered energy storage architecture that spans short-, medium-, and long-duration cycles.

Electrochemical storage offers advantages such as fast response and ease of distributed deployment, making it well-suited for short-duration regulation. Physical energy storage technologies, characterized by large capacity and low cost, are more appropriate for medium- to long-duration applications. Hydrogen storage, meanwhile, enables inter-seasonal energy shifting and plays a critical role in multi-energy coupling. The coordinated integration of diverse storage technologies not only enhances overall system reliability and cost-effectiveness but also enables flexible energy management across different time scales and application scenarios.

Looking ahead, the mere optimization of storage materials is insufficient if the underlying grid architecture remains static. While diversified storage configurations are essential to match fluctuating loads, their efficiency is frequently compromised by the systemic losses inherent in traditional alternating current (AC) distribution. This structural mismatch highlights a critical need to transcend incremental storage improvements and rethink the power distribution topology itself. By pivoting toward DC distribution, the system can eliminate redundant conversion stages, transforming energy storage from an isolated component into a streamlined, high-efficiency backbone for zero-carbon energy systems.

2.3. Current Status of DC Distribution Technologies

As a critical enabling component of the PEDF system, DC distribution technology plays a central role in supporting the coordination between PV generation and energy storage. By minimizing AC/DC conversion stages, it is better suited to accommodates the needs of emerging electric loads and provide the foundational infrastructure for flexible system control. This contributes significantly to improving overall system energy efficiency, reducing conversion losses, and achieving seamless integration of various renewable energy and storage devices.

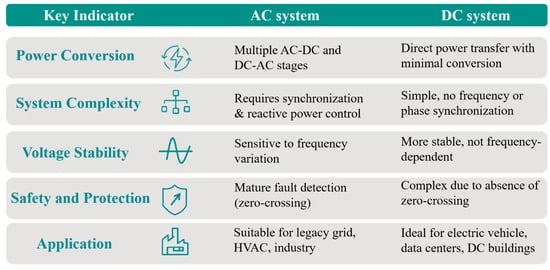

The ongoing decentralization of power systems—shifting from massive centralized plants to distributed, medium-to-low voltage networks—has exposed the inherent inefficiencies of traditional AC backbones. Since the primary components of the PEDF ecosystem, ranging from PV arrays and battery storage to EV chargers and light-emitting diode (LED) loads, are natively DC, the adoption of DC distribution becomes a matter of topological logic rather than mere preference. By circumventing redundant DC/AC conversion stages, these systems can recapture approximately 14% of energy otherwise lost to heat [45]. Beyond efficiency, the elimination of frequency synchronization and reactive power compensation simplifies the control architecture, allowing for a leaner, high-power-density infrastructure. This structural alignment makes DC distribution not just an alternative, but the definitive framework for integrating the multi-unit renewable and storage assets central to PEDF applications. As summarized in Figure 6, DC systems can exhibit potential advantages over traditional AC configurations in terms of reduced conversion stages, simplified power interfaces, and compatibility with renewable and storage components. These characteristics make DC distribution a promising option for the system, particularly in scenarios where photovoltaic generation and battery storage operate natively on direct current.

Figure 6.

Side-by-side visual comparison between AC and DC systems across key technical dimensions.

Traditionally, DC distribution has been synonymous with low-voltage, localized bus architectures—most notably the 48 V standard—which served as a stable environment for low-power residential and office electronics. However, the inherent scalability constraints of these legacy configurations become a liability when confronted with the high-power, long-distance transmission demands of modern infrastructure [46]. The recent surge in PV capacity, coupled with the sophisticated requirements of smart microgrids, has catalyzed a shift from these “localized pockets” of DC power toward integrated, high-voltage distribution hierarchies. This evolution is not merely an expansion of scale, but a fundamental rethink of system architecture. The structural superiority of this emergent DC paradigm, particularly its ability to bypass the conversion bottlenecks that hamper traditional AC systems, is quantified and visualized in Figure 6. By juxtaposing the two frameworks, the figure clarifies why DC distribution is uniquely positioned to handle the voltage resilience and rapid-response demands of the PEDF environment.

The transition to an efficient PEDF network hinges on three synergized technical pillars. At the architectural level, industry-standard voltage platforms—specifically ±750 V and ±1500 V—establish a common “interoperability language,” effectively minimizing the conversion penalties between PV arrays and battery storage [47,48]. This standardized efficiency, however, necessitates a specialized protection logic: since DC circuits lack natural zero-crossing points, traditional arc extinction fails, requiring a pivot toward high-speed Insulated Gate Bipolar Transistor (IGBT) or SiC-based electronic breakers for microsecond-level fault isolation [49]. Ultimately, these hardware foundations are integrated via intelligent multi-port energy management [50,51], where programmable converters and modular “plug-and-play” topologies replace rigid engineering with a scalable, self-adaptive framework. This evolution from isolated components to a coordinated ecosystem is what fundamentally secures the operational resilience of modern DC distribution systems.

As the system scales in complexity, the limitations of conventional single-level low-voltage DC (LVDC) distribution—most notably the prohibitive line losses and wiring costs associated with high currents [52]—have catalyzed a shift toward hybrid multi-voltage bus architectures. By integrating medium-voltage (±750 V) backbones for long-distance transport with low-voltage (±380 V or 48 V) sub-grids for end-user zones [53], these systems effectively bypass the “efficiency–safety” trade-off. This segmented strategy does more than merely recapture energy lost to resistance; it creates a modular infrastructure where DC-DC converters act as both energy gateways and protective buffers [54]. Critically, our analysis suggests that while the deployment of such hierarchical topologies involves higher initial capital expenditure, the lifecycle economic performance is significantly superior due to reduced cable cross-sections and optimized maintenance [55]. Beyond economics, this architecture introduces a vital layer of zonal resilience: by partitioning the network into distinct voltage domains, fault events can be localized and isolated through dedicated converters without compromising the entire grid. For PEDF applications—where DC buses must directly interface with sensitive, flexible loads—this hierarchical approach transforms the distribution network from a passive cable system into a programmable, self-defending energy ecosystem.

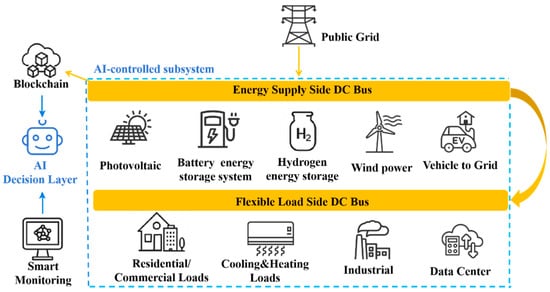

Building upon these hardware foundations, the integration of intelligent DC bus systems—equipped with pervasive sensing and adaptive control—has transformed the distribution network from a static conduit into an autonomous, self-healing grid [56]. As PEDF architectures evolve toward multi-energy collaboration, the deployment of Artificial Intelligence (AI) across Energy Management Systems (EMS) and edge nodes has emerged as the definitive pathway for managing system complexity [57,58]. Rather than relying on rigid, rule-based logic, AI models leverage multi-source inputs to facilitate dynamic energy routing and high-fidelity power forecasting, effectively taming the stochastic volatility inherent in PV-storage-hydrogen coupling.

In particular, the potential of AI extends to the sophisticated optimization of hydrogen-based storage transitions. By employing deep learning (DL) and recurrent neural networks (RNN), researchers have demonstrated that P2H (Power-to-Hydrogen) conversion can be strategically synchronized with renewable surges, significantly enhancing the economic viability of seasonal energy shifting [59]. Furthermore, the convergence of AI with decentralized frameworks—such as federated learning and blockchain—addresses the critical imperative of data security [60]. This synergy ensures that distributed control in the system remains not only resilient and optimized but also cryptographically secure, fostering a trusted environment for multi-agent energy sharing. Figure 7 illustrates the intelligent architecture of a PEDF-based DC distribution system enabled by AI and smart grid integration.

Figure 7.

Intelligent architecture of the PEDF-based DC distribution system enabled by AI and smart grid technologies.

Despite its efficiency advantages, DC distribution is still limited by protection and safety complexity (fast-rising DC faults and no natural current zero-crossing, making selective isolation and arc mitigation harder and often costlier). In addition, the realized efficiency gain is architecture-dependent: mixed AC/DC buildings may become converter-dense, and immature standards/interoperability and retrofit compatibility issues can increase integration risk and lifecycle cost.

At the architectural zenith, the convergence of AI and smart grid technologies endows DC distribution with a closed-loop “perception–prediction–control–feedback” cognitive cycle. This paradigm shift redefines traditional power conduits as intelligent energy neural networks, capable of autonomous learning and dynamic evolution in response to environmental perturbations. Beyond mere automation, this neural-like adaptability is fundamental to enhancing the self-governance and anomaly resilience of PEDF system. Crucially, as these networks move toward a state of autonomous cognition, the focus of research naturally shifts from the static robustness of the architecture to its dynamic “flexibility”—the system’s ultimate capacity to absorb multi-scale fluctuations without compromising operational integrity.

2.4. Current Status of Demand-Side Flexibility

Demand-side flexibility has transcended its traditional role as a reactive buffer, emerging as the intelligent regulatory nucleus of the PEDF framework. While the IEA initially characterized this flexibility as the capacity of a building to modulate demand relative to local climate and grid signals [61], the advent of the Internet of Things (IoT) and smart grid technologies has fundamentally redefined its operational boundaries. Today, it is no longer a passive response model but an active, real-time participant in power system orchestration.

By leveraging a data-driven synergy of big data and AI, modern flexible demand systems operationalize the “generation–grid–load–storage” coordination philosophy. This transformation is manifested through a sophisticated tri-stage closed-loop: pervasive sensing for real-time situational awareness, intelligent decision-making for multi-objective optimization, and dynamic execution for precision load modulation. This evolutionary shift ensures that the demand side is no longer a source of uncertainty, but a strategic asset capable of elastically balancing the stochastic volatility of renewable energy sources.

Transcending traditional demand-side response, building-level flexibility has evolved into a “building-led” self-regulatory paradigm. This autonomy is primarily manifested through the dynamic alignment of consumption profiles with real-time price signals or PV generation curves, effectively converting the building from a passive load into a proactive grid stabilizer [62]. Within this framework, Energy Storage Systems (ESS) act as the critical temporal buffer; by shifting surplus solar generation to nocturnal periods, they not only maximize self-consumption but also alleviate the capital burden of excessive storage sizing [63]. Beyond simple energy shifting, strategic ESS modulation provides essential power smoothing capabilities. By constraining power variation within ±10% over five-minute intervals [64], buildings gain the technical threshold required to participate in high-value frequency regulation and reserve markets. Furthermore, the integration of multi-energy complementarity—spanning electricity, heating, and cooling—introduces a layer of “passive survivability” [65]. This thermal-electric synergy extends the operational uptime of critical loads during grid instability or extreme weather. When scaled from individual units to building clusters, this flexible control logic transcends local optimization to provide city-scale regulatory potential [66]. The specific typologies and control mechanisms governing these flexible loads are systematically categorized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Types of Flexible Loads and Their Control Mechanisms in PEDF System.

In PEDF system, the effective operation of demand-side flexibility relies on a multi-layered and coordinated control strategy framework. The core objectives include real-time supply-demand balancing, load curve optimization, improvement of system energy efficiency, and coordinated multi-energy scheduling. Based on different control goals and load characteristics, current flexible load control strategies can be broadly categorized into four types:

- Price-based control guides users to actively adjust their electricity usage in response to real-time or time-of-use pricing mechanisms. This approach is particularly suitable for household deferrable loads.

- Incentive-based control offers financial compensation to motivate commercial and industrial users to participate in peak shaving or frequency regulation services.

- Direct Load Control (DLC) allows operators or aggregators to directly manage the operational status of loads. It is commonly applied to interruptible devices such as water heaters and air conditioners.

- Prediction- and optimization-based control, such as Model Predictive Control (MPC), relies on user load modeling and state forecasting to enable autonomous scheduling and edge-intelligent control. This strategy is suitable for dynamic load scenarios such as electric vehicle fleets and heat pump systems.

In practical deployment, the implementation of flexible load control typically depends on the integration of intelligent sensing terminals (e.g., smart plugs, sensors, EV chargers), communication protocols (e.g., IEC 61850, Modbus, OpenADR), and user/aggregator-side energy management platforms (HEMS, CEMS, VPP). Together, these components form a closed-loop system encompassing “data sensing–control decision–execution feedback.” In recent years, the introduction of artificial intelligence and edge computing has further enhanced the intelligence and adaptability of control strategies, enabling behavior modeling, real-time optimization, and autonomous response. These advancements provide critical support for building a flexible and storage-integrated load-side regulation capability in the system.

Implementation of demand-side flexibility within the system generally gravitates toward three evolving architectures: centralized platforms for high-precision global optimization [72], decentralized models for autonomous, user-driven response [73], and hybrid coordinated frameworks. The latter, increasingly prevalent in multi-agent environments, leverages game theory and reinforcement learning to strike a balance between systemic oversight and local autonomy [74].

Despite these theoretical advancements, a significant gap remains between idealized control logic and real-world deployment. First, low user engagement—particularly among residential stakeholders—impedes scalability [75]; addressing this requires a pivot toward community-based sharing models and dynamic incentive schemes, as exemplified by the Tesla Powerwall initiatives [76]. Second, the divergent interests of grid operators and virtual power plants (VPPs) create coordination deadlocks [77]. Resolving such conflicts necessitates sophisticated game-theoretic models, such as Nash equilibrium coupled with federated learning, to ensure privacy-preserving yet collaborative decision-making [78]. Finally, the vulnerability to extreme weather poses a critical threat to system robustness. To mitigate this, shifting toward a closed-loop “prediction-optimization-feedback” architecture—supplemented by conservative safety buffers like a 20% SOC threshold [79]—is essential to ensuring system resilience during periods of acute environmental stress.

Within the PEDF ecosystem, the synergy between flexible loads and physical ESS constitutes a sophisticated “Virtual-Physical” coupling. While ESS provides tangible intertemporal shifting, flexible loads function as “virtual storage,” providing peak-shaving and power modulation without the capital intensity of chemical batteries. Their coordination—spanning time-hierarchical, power-coupled, and market-based modes—allows for a stratified response where agile loads handle minute-level volatility while ESS manages hour-level energy balance [80]. This joint dispatching not only mitigates renewable intermittency but also extends battery longevity by reducing deep-cycle stress [81].

Realizing this synergy demands a robust EMS capable of synchronous, multi-device orchestration. By integrating AI-driven forecasting with high-reliability communication, the EMS transforms individual flexible assets into a cost-effective aggregated resource pool. This transition from isolated device control to a unified “virtual power plant” logic marks a decisive shift in next-generation power systems, establishing the foundational architecture required for the holistic current status and future trajectory of PEDF system.

2.5. Current Status of Integration of PEDF System

The integration of photovoltaic, energy storage, DC distribution, and flexibility—collectively referred to as PEDF system—marks a paradigm shift toward multi-energy coordination in modern buildings and microgrids [82]. Rather than being a simple co-location of subsystems, PEDF integration represents a deeply coupled architecture that requires coordination across energy flows, time scales, and control hierarchies [83]. Effective integration is essential to unlock the full potential of the system, particularly in achieving low-carbon, resilient, and cost-optimized energy infrastructures. Table 4 summarizes five representative PEDF pilot projects or regions worldwide, highlighting their energy sources, storage types, and control strategies. It illustrates the variety of integration approaches depending on climate, urban layout, and energy policy.

Table 4.

Representative integration cases of PEDF in diverse scenarios.

Current PEDF integration approaches can be categorized along two primary dimensions: system architecture and coupling depth. From an architectural standpoint, centralized integration schemes typically rely on a supervisory EMS to coordinate large-scale components, such as photovoltaic inverters, battery banks, and aggregated loads [88]. These are commonly found in campus-level microgrids and energy service hubs. In contrast, distributed integration schemes are more prevalent in residential or commercial buildings, where individual subsystems operate with local control while exchanging limited information with the grid or a local aggregator [89].

In terms of coupling depth, the system ranges from loosely coupled architectures—where subsystems operate independently and are only linked via a monitoring platform—to tightly coupled architectures featuring shared control strategies and real-time data exchange. Tightly coupled systems offer enhanced energy optimization and resilience but face higher implementation complexity due to compatibility and standardization challenges.

Several pilot projects exemplify the varying degrees of PEDF integration. For instance, in Germany, the “Energie-Kommune” microgrid demonstration coordinates solar generation, battery storage, and flexible community loads under a centralized control platform [90]. In Japan, the Fujisawa Sustainable Smart Town integrates rooftop solar and home batteries via local DC distribution networks, enhancing self-consumption and grid support [91]. In China, several industrial parks have deployed source–grid–load–storage integrated platforms, using AI-enhanced EMS to balance real-time PV generation, storage dispatch, and process-related flexible loads [92].

Despite these advances, the integration of the system still faces significant barriers. Chief among them are the lack of standardized communication protocols and interoperable device interfaces, which hinder plug-and-play capabilities [93]. Additionally, most building-level EMS platforms remain fragmented, with limited predictive control functions or flexibility orchestration mechanisms [94]. Interfacing challenges between traditional HVAC systems, lighting, electric vehicles (EVs), and emerging ESS components further complicate integration efforts.

Looking ahead, PEDF integration is expected to evolve toward modular, platform-based architectures featuring standardized APIs, interoperable hardware, and AI-driven control frameworks. Integration with Building Information Modeling (BIM) and digital twin technologies will enable more accurate simulation, planning, and performance optimization across the building life cycle. Moreover, the development of international standards—such as IEC 61850 for communication and IEEE 2030 for distributed energy resource interoperability—will provide critical technical foundations for seamless integration [95,96].

Ultimately, capturing the full potential of PEDF system necessitates a departure from fragmented component optimization toward a holistic integration paradigm. This evolution demands a rigorous hardware-software co-design, where hierarchical coordination strategies are seamlessly embedded within scalable, AI-driven control platforms. As such, PEDF integration transcends the scope of mere technical deployment; it represents a systemic endeavor that redefines the relationship between architecture, energy, and intelligence. By consolidating these cross-disciplinary innovations, PEDF serves as the definitive blueprint for the next generation of intelligent, decarbonized energy infrastructures—a transition that is already manifesting across diverse real-world application scenarios.

3. Practical Applications of PEDF System

With the global push toward decarbonization and the evolution of next-generation power systems, PEDF system is gaining momentum in the building sector worldwide. In both developed and emerging economies, representative pilot projects have emerged to demonstrate the feasibility of PEDF integration. This section analyzes typical application cases across three key scenarios—single buildings, industrial parks, and community microgrids—to assess the practical value of PEDF system by examining their technical features and implementation outcomes.

As shown in Table 5, building-scale PEDF system typically install 20–150 kW PV with ~10–18% energy efficiency gains from DC distribution, whereas industrial park deployments reach 500 kW to 5 MW, with system-level renewables self-consumption rising above 50% and CO2 emissions dropping by 40–50%. Community-level setups often achieve efficiency gains in the 10–15% range and annual CO2 reductions of tens to hundreds of tons. While the term “PEDF” is not explicitly used in the referenced literature, the cited systems embody the core architectural elements defined herein—namely, photovoltaic generation, energy storage, DC power distribution, and flexible load control.

Table 5.

Quantitative Comparison of PEDF System Deployments in Different Scenarios.

3.1. Single Buildings

Representative implementations of PEDF architecture have been deployed in various single-building scenarios across different countries, showcasing the growing feasibility and value of integrated photovoltaic (PV), energy storage, direct current (DC) distribution, and flexible load control systems.

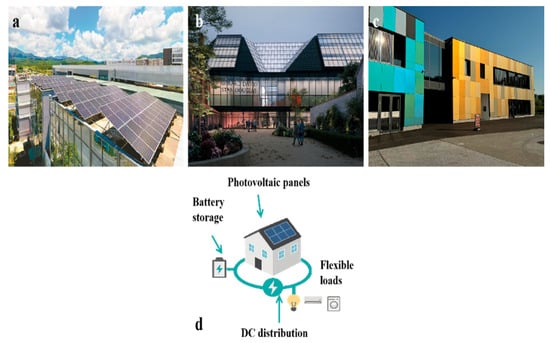

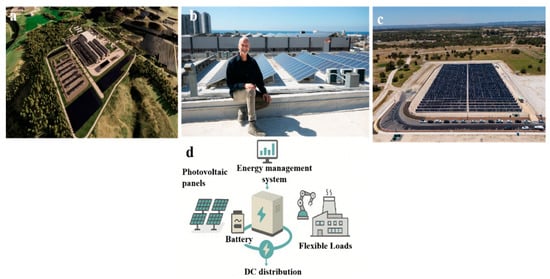

A notable example is the office building of the China State Construction Green Industrial Park, located in the Shenshan Special Cooperation Zone of Shenzhen [104]. This early-stage demonstration project integrates rooftop PV generation, lithium battery energy storage, DC-based distribution, and intelligent load management. As shown in Figure 8a, the building covers 2500 m2 and installs over 400 m2 of PV panels. Since commissioning, it has achieved annual electricity savings exceeding 100,000 kWh and CO2 emission reductions of over 47%, equivalent to afforesting approximately 160,000 m2. The system also enhances real-time demand-side flexibility under varying solar input conditions.

In Europe, the Brusk Museum and art site in Bruges, Belgium, presents a high-performance building-integrated photovoltaics (BIPV) application that aligns with PEDF principles in Figure 8b. While it does not feature battery storage, the project integrates 1200 m2 of aesthetic PV façade and roof elements, providing significant on-site renewable generation while preserving architectural heritage. The DC-linked infrastructure supports low-loss internal distribution, and demand-side management is partially achieved through time-synchronized energy control [105].

Figure 8.

Representative PEDF applications in single buildings: (a) China State Construction Green Industrial Park, Shenzhen, China [104]; (b) BRUSK Museum and Art Site, Bruges, Belgium [106]; (c) Sonnenkraft Campus, Sankt Veit an der Glan, Austria [107]; (d) Generalized PEDF system architecture for single-building deployment.

Another exemplary case is the Sonnenkraft Campus in Sankt Veit an der Glan, Austria, which functions as both an educational and demonstration site for renewable building technologies (Figure 8c). This building incorporates BIPV facades, DC infrastructure, and EV charging stations managed through a smart control platform. Although stationary energy storage is not explicitly included, the integration of controlled EV loads and building automation contributes to effective load shaping and real-time response, embodying core PEDF features [107].

Collectively, these cases demonstrate the flexibility of PEDF implementation across various climatic and functional contexts. Despite differing emphases—such as BIPV aesthetics in Europe or energy autonomy in China—they share a common architectural foundation and provide practical insights into the building-scale realization of PEDF system.

In summary, single-building PEDF system is characterized by compact system integration, straightforward control architecture, and a high degree of local autonomy. Their energy consumption profiles are often well-defined, with flexible loads such as lighting, HVAC, and electric appliances forming the primary demand-side elements. While these systems offer a highly effective model for achieving energy self-sufficiency and emissions reduction at the building level, their scalability is inherently limited by spatial constraints and the lack of inter-unit coordination. These characteristics distinguish them from larger-scale PEDF implementations in industrial parks and community microgrids, where system complexity, energy flow diversity, and control strategies become significantly more intricate.

3.2. Industrial Parks

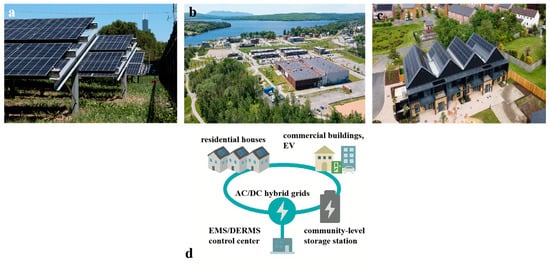

A prominent example of PEDF deployment at industrial-park scale is the titanium melting facility being built by Timet in Ravenswood, West Virginia (Figure 9a) [108]. The integrated microgrid comprises a 106 MW photovoltaic array paired with a 50 MW/260 MWh battery energy storage system, autonomously powering high-demand furnace loads. By combining large-scale PV generation, substantial energy storage, DC-oriented microgrid structuring, and flexible industrial load adjustment, the project embodies a full-scope PEDF implementation in an industrial context. Moreover, it demonstrates industrial-scale feasibility of renewable self-supply and provides a replicable model for decarbonizing energy-intensive manufacturing facilities.

Similar efforts are observed at the Shoresh Sandals factory in Israel, which transitioned to 100% on-site solar energy by integrating rooftop PV arrays with energy efficiency retrofits, enabling full daytime operation off-grid (Figure 9b) [109]. While smaller in scale, this case highlights how direct renewable supply can decouple industrial activities from fossil-based grids, especially in decentralized or rural contexts.

In contrast, the Peel Business Park in Western Australia illustrates a more flexible, multi-tenant PEDF approach, incorporating a 1.2 MWp solar farm, 2.5 MWh/1 MW battery storage, and a smart embedded microgrid network (Figure 9c). With over 50% of park-wide demand met via renewables, the system supports modular integration, load balancing across diverse industrial users, and dynamic energy management.

Together, these cases exemplify the adaptability of PEDF system across varying industrial scales—from single-site factories to distributed industrial estates—while affirming their role in enabling resilient, decarbonized, and cost-effective industrial energy infrastructures.

A typical PEDF system layout for industrial parks is illustrated in Figure 9d, highlighting the integration of large-scale PV installations, centralized battery storage, DC power distribution infrastructure, and industrial flexible loads under unified energy management.

Figure 9.

Representative PEDF applications at industrial-park scale: (a) Timet titanium melting facility (USA), integrating 106 MW PV and 260 MWh Battery Energy Storage System (BESS) for autonomous operation [108]; (b) Shoresh Sandals factory (Israel), fully powered by on-site rooftop PV under flexible load strategy [110]; (c) Peel Business Park (Australia), featuring a solar-powered embedded microgrid with battery storage and load coordination [111]; (d) Generalized architecture of PEDF deployment in industrial settings.

In summary, the system implemented at the industrial park scale are characterized by high system capacity, centralized architecture, and coordinated operation across multiple energy nodes. Compared to single-building deployments, industrial parks feature medium-voltage DC distribution backbones, large-scale PV arrays, and megawatt-scale battery storage systems that enable load balancing and peak shaving. Flexible demand in this context often includes industrial production lines, HVAC clusters, and robotic units, which require real-time coordination through advanced EMS. The integration of PEDF in industrial parks not only enhances energy autonomy and carbon reduction, but also provides robust energy resilience for critical production processes. These characteristics make industrial parks an ideal environment for large-scale PEDF demonstration and replication.

3.3. Community Microgrids

A notable PEDF implementation at the community level is the Bronzeville microgrid in Chicago, IL. The project integrates 750 kW of rooftop solar PV with a 2 MWh battery energy storage system, serving over 1000 residences as well as critical public infrastructure like the local police and fire department headquarters. The system supports islanded operation and is coordinated through an advanced distributed energy resource management system (DERMS) platform, reflecting a full PEDF approach involving generation, storage, flexible load integration, and DC/AC distribution. This community-scale deployment significantly enhances resilience and demonstrates how PEDF system can be scaled to benefit urban neighborhoods (Figure 10a) [112].

Another representative case is the Lac-Mégantic smart microgrid in Québec, Canada, which was jointly developed by Hydro-Québec and local stakeholders (Figure 10b) [113]. This project features 1 MW of PV capacity and a 1.6 MWh battery energy storage system, supplying a mix of residential, commercial, and institutional loads through a controllable microgrid platform. Beyond its technological implementation, Lac-Mégantic stands out for its participatory planning model and serves as a living laboratory for autonomous clean energy systems in small towns.

The Hook Norton low-carbon community in Oxfordshire, UK, further exemplifies localized PEDF deployment (Figure 10c) [114]. It includes solar PV arrays, shared battery storage, ground-source heat pumps, and an innovative microgrid that manages energy flow across multiple smart homes. Enabled by citizen co-investment and community ownership, the project fosters not only technical resilience but also socio-economic empowerment in rural areas.

Figure 10.

Representative PEDF applications in community-scale microgrids. (a) Bronzeville microgrid in Chicago, USA [112]; (b) Lac-Mégantic microgrid in Québec, Canada [115]; (c) Hook Norton community microgrid in Oxfordshire, UK [116]; (d) Schematic diagram of a typical PEDF-enabled community microgrid architecture.

Together, these cases illustrate the adaptability of PEDF system across diverse geographic, institutional, and governance contexts, offering viable blueprints for bottom-up energy transition strategies in communities. A generalized structural model of PEDF implementation in community microgrids is illustrated in Figure 10d. It highlights the distributed nature of PV and storage resources across multiple buildings, the hybrid DC/AC distribution framework, and the central EMS platform coordinating flexible loads and island-mode operations.

In community microgrids like Bronzeville, PEDF system expands beyond single-site integration by aggregating distributed PV and storage assets, enabling coordinated control across multiple nodes. With DC/AC mixed distribution and advanced DERMS orchestration, these systems support both resilience and energy optimization on a neighborhood scale, making them distinct from building-level solutions while still less complex than industrial park deployments.

To distill the operational nuances across these spatial scales, Table 6 provides a comparative synthesis of the key technical parameters. By juxtaposing the distinct voltage standards, load profiles, and flexibility mechanisms of single buildings against those of industrial parks and community microgrids, the table highlights the adaptive nature of PEDF architectures as they expand from individual units to interconnected networks.

Table 6.

Comparative analysis of PEDF system characteristics across different implementation scales.

In summary, the system at the community microgrid level are characterized by their multi-node architecture, integrating both centralized and distributed energy resources such as rooftop PV, household batteries, and community-scale storage units. These systems rely on intelligent aggregation platforms such as DERMS to enable coordinated energy dispatch across diverse user types and load profiles. With hybrid DC/AC distribution networks, community microgrids support a mix of residential, commercial, and public infrastructure and are often designed to operate in both grid-connected and islanded modes. These features make community-scale PEDF system uniquely positioned to provide localized energy resilience, promote energy equity, and serve as replicable models for decentralized, low-carbon urban energy systems.

4. Major Challenges and Technological Breakthroughs in PEDF System

Despite the transformative potential of PEDF systems in the energy transition, their ubiquitous deployment is currently impeded by a convergence of intertwined constraints across technical, economic, and socio-institutional domains.

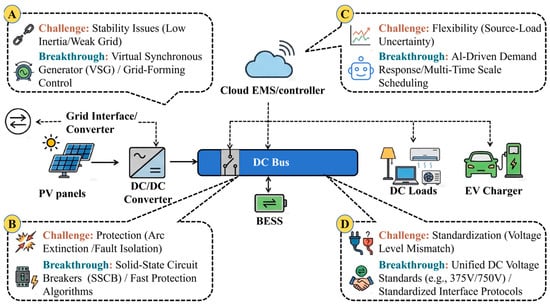

To navigate this landscape, Figure 11 first provides a techno-topological mapping, visualizing where these specific hurdles manifest within the physical infrastructure—from component-level interfaces to system-wide control layers. Complementing this visual framework, Table 7 systematically details the critical bottlenecks regarding control complexity, economic feasibility, user engagement, and regulatory frameworks, alongside their corresponding technological breakthrough pathways. The following subsections offer a deep-dive analysis of these four dimensions.

Figure 11.

Schematic representation of the PEDF system topology mapping key challenges to technological breakthroughs. The annotations correspond to four critical dimensions: (A) Stability issues at the converter interface addressed by grid-forming control; (B) Protection challenges at the DC bus resolved by solid-state protection; (C) Flexibility constraints in system scheduling managed by AI-driven demand response; and (D) Standardization gaps at load interfaces bridged by unified voltage protocols.

Table 7.

Major challenges and associated technological breakthroughs in PEDF system.

4.1. High Complexity in Multi-Energy Coordinated Control

PEDF system integrates multiple functional modules—including PV generation, energy storage, DC distribution, and flexible loads—forming a multi-source, heterogeneous, and multi-timescale dynamic energy network. System operation must simultaneously fulfill multiple objectives, such as efficiency maximization, cost minimization, and carbon emission reduction, while adhering to various constraints, including storage capacity limits, load demands, and grid interaction requirements. This results in extremely high complexity for energy flow regulation, state forecasting, and load scheduling tasks [117].

From a modeling perspective, the coordinated operation of PEDF system can be abstracted as a multi-objective optimization problem. Typical control objectives include minimizing operating costs, reducing carbon emissions, and limiting power exchange with the external grid, which can be expressed as:

subject to the fundamental energy balance constraint:

as well as storage operational limits:

where Cop(t) denotes the system operating cost at time t, ECO2(t) represents the corresponding carbon emissions, and Pgrid(t) is the power exchanged with the external grid. Ppv(t), PESS(t), Pgrid(t) denote the photovoltaic generation, energy storage power, and total load demand, respectively. SOC(t) is the state of charge of the energy storage system, with SOCmin and SOCmax representing its operational limits.

Here, the load demand can be decomposed into a base component and a flexible component, reflecting the increasing role of demand-side participation in the system. This formulation highlights the intrinsic coupling between renewable generation uncertainty, storage dynamics, and flexible demand, which collectively give rise to strong temporal dependencies across multiple time scales.

The core challenge of multi-energy coordinated control in the system arises from the strong spatiotemporal coupling between volatile renewable generation and dynamic control requirements. Photovoltaic output is highly sensitive to weather conditions, exhibiting intraday fluctuations that may reach 60–80% of the installed capacity, while practical ramp-rate constraints for power regulation are typically limited to around 10% per minute [118]. This inherent mismatch forces frequent charge–discharge switching of the ESS, accelerating degradation and reducing battery cycle life by approximately 10–15%.

The challenge is further intensified by the need to coordinate control actions across multiple time scales. Within a single system, second-level frequency regulation, minute-level power balancing between PV and storage, and hour-level load scheduling must be simultaneously addressed under a unified framework. However, existing hierarchical control strategies often suffer from non-negligible response latency, which undermines their ability to meet the real-time operational requirements of the system [119]. Beyond temporal coordination challenges, the high sensitivity of DC distribution networks to voltage deviations further amplifies system vulnerability. The stochastic integration of distributed energy resources (DERs) can induce bus voltage deviations exceeding ±5%, surpassing the safety thresholds specified in IEEE Std 1547.9-2022 and posing tangible operational risks [120].

While centralized EMS struggle to cope with such uncertainty and fast dynamics, decentralized and hierarchical control architectures—although more flexible—introduce new challenges related to communication delays, data consistency, and control coupling [121]. Addressing these limitations requires the integration of advanced control and optimization techniques, including MPC [122], Multi-Agent Systems (MAS) [123], and AI-driven approaches such as reinforcement learning and swarm intelligence [124]. In parallel, the development of integrated edge–cloud–terminal energy scheduling platforms is increasingly recognized as a key enabler for real-time optimization, system-wide learning, and adaptive evolution at the building cluster level.

4.2. Economic Constraints Limiting Large-Scale Deployment

The economic bottleneck of PEDF system is primarily characterized by the dual constraints of high upfront capital investment and narrow revenue channels. According to IRENA (2024) [125], the initial deployment cost of DC-based systems is typically 15–25% higher than that of conventional AC architectures. This cost premium is largely attributed to the expensive components required—such as SiC power devices, solid-state DC circuit breakers, and DC-specific power electronics—which together account for over 60% of total system costs [125]. Although lithium battery costs have declined in recent years, the associated power electronic interfaces remain a significant financial burden.

A particularly pressing issue is the imbalanced revenue structure. More than 80% of project income is currently derived from arbitraging time-of-use electricity prices, while revenues from participation in frequency regulation, reserve capacity, and other ancillary service markets account for less than 5% [126]. For instance, in an industrial park in Shenzhen, a hardware manufacturing enterprise deployed a 500 kW/1075 kWh energy storage system provided by Welion Energy. The system charges during off-peak periods with low electricity prices and discharges during peak periods to support production loads. This temporal shifting of energy usage reduced operational costs and improved economic returns [127]. In recent years, the Chinese government has gradually phased out subsidies for photovoltaic (PV) projects. As of 1 August 2021, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) ceased central financial support for new onshore wind, centralized PV plants, and commercial/industrial distributed PV installations. This policy shift aims to promote grid parity and reduce long-term reliance on government subsidies [128]. Moreover, the early-stage deployment of PEDF system requires substantial capital outlays for PV modules, intelligent control terminals, and system integration. The experimental nature of current operation and energy efficiency management frameworks further extends the investment payback period, thereby limiting the scalability and replicability of existing business models [129].

A more fundamental economic constraint facing system lies in the absence of mature market mechanisms. Although the costs of photovoltaic and energy storage technologies continue to decline, the overall cost-performance ratio of the system still struggles to compete with traditional distribution models. The lack of value capture mechanisms—such as dynamic pricing schemes, carbon credit incentives, and distributed energy trading platforms—prevents the monetization of system flexibility and carbon reduction benefits. To overcome this issue, a dual-track strategy is required. On one hand, business model innovation must be promoted, shifting from equipment-based sales toward EaaS models through energy performance contracts and VPP aggregation. On the other hand, a comprehensive incentive framework—integrating carbon markets, capacity markets, and flexibility markets—should be developed. This would allow project stakeholders to benefit from carbon trading premiums, capacity remuneration mechanisms, and ancillary service bidding, thereby improving overall project profitability. In parallel, the development of standardized system interfaces and the alignment of regulatory frameworks are essential to ensure compatibility and scalability. Ultimately, these efforts will contribute to a positive feedback loop between technological advancement, economic feasibility, and market ecosystem maturity.

4.3. User Engagement and the Comfort Trade-Off

Behavioral inertia and comfort expectations form the core social barriers to the practical implementation of flexible load control, stemming from a fundamental contradiction between user participation mechanisms and individual behavioral characteristics. A notable example is the “Smart Savers Texas” demand response program, in which residential users experienced automated thermostat adjustments of up to 4 °F (approximately 2.2 °C) during peak load events [130]. Although users had consented to the program, many expressed dissatisfactions when they were unable to override device settings manually, raising concerns over loss of control and prompting resistance to automated load interventions. This incident highlighted users’ sensitivity to perceived control loss and the importance of comfort in the adoption of demand-side management technologies.

On a technical level, the tension between load-shifting strategies and comfort assurance is most apparent during high electricity price periods when energy storage systems may limit HVAC power. Such actions can cause indoor temperature fluctuations, which must be restricted within ±1 °C, in accordance with ASHRAE Standard 55 to maintain thermal comfort [131]. A Canadian study demonstrated that thermal energy storage (TES) systems could effectively shift heating and cooling loads from peak to off-peak periods, reducing peak power demand by 25% to 45%, while also having a positive impact on thermal comfort during the shifting process [132]. Further analysis by Winzer et al. revealed significant behavioral segmentation in consumer responses: while approximately 30% of users actively considered electricity prices when choosing energy plans, the remaining 70% were unwilling to compromise on lifestyle quality. Compounding this, only 30% of users believed that financial incentives were sufficient to offset comfort loss, reflecting a cognitive mismatch between technical designs and user perceptions [133]. This leads to trust deficits that undermine broader participation in flexibility programs. Addressing these barriers requires a user-centric approach that balances automation with control flexibility, incorporates personalized comfort modeling, and improves transparency in control mechanisms. In doing so, PEDF system can better align technological potential with human acceptance, ensuring both reliability and long-term user engagement.

Current centralized control paradigms exhibit clear limitations in addressing the complexities of human–machine interaction within PEDF system. Predefined strategies for load curtailment and peak shaving, which often lack fine-grained modeling of user behavioral preferences and lifestyle patterns, frequently lead to declines in user satisfaction and a vicious cycle of reduced participation. Overcoming this barrier necessitates a shift towards socio-technical co-evolution frameworks that integrate human behavior into system design and operation. A key breakthrough lies in the development of user-behavior-driven flexible control models [134], incorporating insights from anchoring effects in psychology [135], incentive structures from behavioral economics [136], and cognitive principles from human–machine interaction research [137]. This can be achieved through a co-design methodology, which engages users in the creation of personalized adjustment frameworks tailored to their comfort expectations and usage patterns [138]. Furthermore, mobile-based interactive platforms should be employed to deliver real-time, visualized energy consumption feedback, while implementing dynamic pricing incentives to create a bidirectional empowerment loop between users and the system. This multidimensional strategy enhances both social acceptability of technological solutions and system-level performance optimization through behavioral alignment. Ultimately, such a socio-technical integration paradigm provides a novel pathway for addressing the human factors bottleneck in PEDF system; promoting sustained user engagement; and facilitating adaptive, demand-side participation in future energy systems.

4.4. Incomplete Standards and Policy Frameworks

As an emerging paradigm in modern energy systems, the large-scale deployment of PEDF system is increasingly constrained by two fundamental barriers: the absence of standardized technical frameworks and insufficient policy coordination mechanisms.

On the technical side, PEDF system architectures lack unified standards across multiple dimensions such as grid interconnection specifications, voltage level classifications, and safety control strategies. This deficiency leads to limited device compatibility and system interoperability. A prominent example can be found in the DC distribution sector, where discrepancies between IEC 62040-3-1 [139] and UL 1741 SA [140]—in aspects such as fault protection logic and communication interface definitions—pose significant integration challenges. For instance, UL 1741 SA requires inverters to remain connected during grid disturbances and support grid stability functions, while IEC 62040-3 focuses more on the performance and testing protocols of uninterruptible power systems (UPS). Such divergences complicate both equipment design and compliance certification, thereby increasing deployment costs and risks.

In China, the roll-out of PEDF system faces multiple policy-level obstacles, especially in terms of incomplete technical standards and fragmented regional market mechanisms. There is currently no comprehensive, lifecycle-oriented regulatory framework covering device manufacturing, system integration, and operation and maintenance, resulting in inconsistent specifications for energy storage systems with respect to grid acceptance, dispatch frequency, charge/discharge cycles, and depth-of-discharge thresholds. This directly undermines the interoperability of storage assets within PEDF architectures.

Moreover, the absence of inter-provincial market coordination imposes additional barriers: dispatchable capacity from solar-storage systems often must be rerouted through provincial grid operators, reducing transactional efficiency and delaying response capabilities [141]. The situation is further complicated for emerging energy management approaches such as Virtual Power Plants (VPPs). In current practice, VPPs face lengthy grid interconnection certification processes—typically ranging from 6 to 12 months—and are subject to capacity limitations below 10 MW, rendering them insufficient for industrial park-scale applications [142]. For instance, the 2025 Mid- to Long-Term Electricity Trading Implementation Plan issued by the Hubei Provincial Energy Bureau stipulates that VPPs must offer a minimum dispatchable capacity of 10 MW with continuous response capability of at least one hour to be eligible for registration [143]. Additionally, current building energy performance standards, such as GB/T 51350 [144], fail to incorporate indicators for flexible load control, meaning PEDF-enabled systems cannot secure additional points in green building certification schemes. This omission reduces the technical premium of PEDF investments and directly diminishes the incentive for real estate developers to adopt such systems.

This fragmentation of standards and disconnection in policy frameworks has evolved into a systemic bottleneck for PEDF development. Equipment manufacturers face difficulties in collaborative R&D due to inconsistent interface protocols, while system integrators are hindered by inter-regional market barriers, preventing them from achieving economies of scale. Moreover, the misalignment between policy incentives and regulatory evaluation mechanisms further delays the maturation of the industrial ecosystem [145].

To overcome these barriers, a dual-track framework integrating technical and policy innovation must be established. On the technical side, it is essential to accelerate the development of comprehensive guidelines that encompass unified grid interconnection standards, communication protocols, and control interface specifications. Additionally, there is a need to construct next-generation standard systems that integrate energy efficiency assessment with flexible demand-side control metrics [146].

From the policy perspective, a tripartite coordination mechanism should be implemented. This includes:

- At the building level, establishing a certification system for PEDF-enabled infrastructures;

- At the grid level, developing inter-regional flexibility trading markets;

- At the user level, introducing dynamic subsidy mechanisms that reflect system performance and flexibility contributions.

- Furthermore, a comprehensive policy toolbox must be developed to cover the full project lifecycle, encompassing project approval, performance verification, and operational supervision. Only through the deep integration of technical standardization and institutional innovation can PEDF system transition from pilot demonstrations to large-scale deployment.

5. Discussion and Perspective

The future of PEDF system will transcend traditional energy management boundaries, evolving toward a holistic, intelligent, democratized, and carbon-negative paradigm, forming a multi-dimensional, collaborative energy ecosystem. Rather than being limited to energy management at the building or campus level, PEDF will enable the formation of cross-regional smart networks with multi-energy flow coupling. Electricity, heating, cooling, and hydrogen energy will be coordinated through unified dispatching platforms to achieve synergistic complementarity and drive the shift from “local optimization” to “global optimum” in energy systems.

For instance, photovoltaic-DC microgrids will be deeply integrated with district heating networks and hydrogen storage and distribution systems, forming energy hubs with diversified energy coordination. At the same time, the energy network will serve as a core component of urban infrastructure, seamlessly integrated with transportation systems (e.g., solar-storage-charging integrated roads), information networks (5G + Energy IoT), and architectural spaces (building-integrated photovoltaics). Together, these elements will form a “Energy–Information–Space” triune urban operating system.